1. Introduction

The clean energy transition needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s target on limiting global warming to 1.5–2 °C above preindustrial levels requires massive deployment of energy efficiency on a global scale [

1,

2,

3]. The same holds true for meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goal 7 on ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all [

4,

5]. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), energy efficiency can contribute more than 40 % of the greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions needed to meet the Paris Agreement targets [

6]. The IEA refers to energy efficiency as the

first fuel in the clean energy transition [

7]. However, demand for the first fuel needs to increase, and that is where policy action matters the most.

With reference to the ‘first fuel’ narrative, the European Commission (EC) introduced the

energy efficiency first principle (EE1) in the EU energy and climate policy narrative with the ‘Energy Union’ communication of 2015 [

8] and the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ legislative package of 2016 [

9]. EE1 was presented as the overarching theme of EU energy and climate policy and introduced as a nonbinding principle in EU legislation with the regulation of the governance of the Energy Union and climate action (Governance Regulation) adopted in 2018. EE1 was defined as ([

10], p. 15):

“taking utmost account in energy planning, and in policy and investment decisions, of alternative cost-efficient energy efficiency measures to make energy demand and energy supply more efficient, in particular by means of cost-effective end-use energy savings, demand response initiatives and more efficient conversion, transmission and distribution of energy, whilst still achieving the objectives of those decisions”.

In mid-July 2021, the EC presented a proposal to recast the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) [

11,

12]. The proposal was part of the so-called ‘Fit for 55’ package [

13] and included, i.a. stronger provisions on EE1. The European Parliament (EP) and the Council of the EU (Council) reached a political agreement on the recast EED in March 2023, which was formally adopted by the EP and the Council in July 2023 [

14]. This made EE1 a legally binding principle for EU member states (MSs) to apply in policy, planning and decision-making on investments regarding the energy system and in sectors that affect energy supply and energy demand, exceeding 100 million euros each and 175 million euros for transport infrastructure projects. According to the recast EED, MSs shall transpose EE1 into national legislation by 11 October 2025.

As an overarching and binding principle, EED states that EE1 complements two other guiding principles of EU energy and climate policy, i.e. cost-effectiveness and consumer protection. This is highly interesting because making EE1 binding indicates a paradigm shift contrasting the earlier path-dependent agenda for EU energy and climate policy [

15,

16,

17], disconnecting the energy supply side from the energy demand side. According to Recital 18 of the Recast EED, EE1 implies ([

14], p. 4):

“adopting a holistic approach, which takes into account the overall efficiency of the integrated energy system, security of supply and cost effectiveness and promotes the most efficient solutions for climate neutrality across the whole value chain, from energy production, network transport to final energy consumption, so that efficiencies are achieved in both primary energy consumption and final energy consumption. That approach should look at the system performance and dynamic use of energy, where demand-side resources and system flexibility are considered to be energy efficiency solutions”.

From a scientific as well as public policy and business perspective, it is highly interesting to understand how this transformative policy change did happen. How was the binding EE1 framed, formulated and agreed upon under political ambiguity and influence by MSs and different interest groups (IGs)? Analysing public policy includes not only the effects and effectiveness of a policy but also the values and beliefs attached to problem framing, different policy options and the ambiguities of decision-making on policies [

18]. To understand EE1 as a policy instrument, one must understand the policy processes and the politics of policy design. Better knowledge of processes of transformative policy change is important for policy and governance for a clean energy transition towards climate neutrality. This article aims to determine the policy processes and politics that made EE1 a legally binding principle in EU energy and climate policy. Policymaking in the EU is a complex process of agenda-setting, advocacy and decision-making on policy design involving several EU institutions, MSs and IGs in a multilevel governance setting [

19].

Political science offers a variety of theories, frameworks and concepts to explain policy processes and the roles of stakeholders influencing agenda-setting and decision-making on public policy. One such framework is the

multiple streams framework (MSF) [

20,

21,

22], which focuses on three structural factors or streams (problems, policy options and politics) and the role of

policy entrepreneurs framing problems and policy solutions and coupling the streams to change policy. Different frameworks and theories provide complementary ways of analysing a policy process, which together provide us with better knowledge [

23,

24]. Compared to other analytical frameworks, such as

the advocacy coalition framework (ACF) and

discourse analysis, MSF focuses more on the agency of central actors in policy processes. ACF and discourse analysis have been applied by von Malmborg [

25,

26] to analyse the politics of EE1 in the EU, providing knowledge about beliefs, storylines, discourses and conflicts between coalitions and the role of negotiations, policy learning and discursive agency to overcome conflicts. However, there is still a gap in knowledge about the agency of central actors—policy entrepreneurs—in the policy process. This paper fills this gap by addressing the following research questions:

Which problems and policy options were presented, by who and why? How were these problems and policy options framed??

How did the policy window open?

Which strategies were used by the policy entrepreneurs, and why were they successful?

In addition, the paper discusses the role and ethics of policy entrepreneurs in democratic policymaking. Analysing the agency of policy entrepreneurs, this study complements previous studies applying ACF and discourse analysis to explain the policy process and the politics of EE1. Discourse analysis and the ACF could benefit from a combination with MSF to add to the analysis of policy entrepreneurs to better understand agency in policy change, cf. [

27,

28]. The paper will add to the growing literature on the processes and politics of energy efficiency policy in the clean energy transition [

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The article also improves theory on the agency of policy entrepreneurs in EU policymaking, cf. [

21].

2. Theory and Previous Research

2.1. Multiple Streams Framework

The MSF was developed for the analysis of agenda setting in American politics [

20] and has been used extensively to analyse policy processes also in the EU [

38]. It contextualises policy process research into unique arrangements of rules and relationships between values and narratives that cause policy change to occur [

22]. According to the MSF, policymaking is not about rational problem solving but rather about viable problems seeking adequate solutions [

22]. MSF also assumes that policymaking is undertaken under (i) issue ambiguity, i.e. “a state of having many ways of thinking about the same circumstances or phenomena” ([

39], p. 5); (ii) institutional ambiguity, i.e. “a policy-making environment of overlapping institutions lacking a clear hierarchy” ([

40], p. 75); (iii) time constraints; and (iv) organised anarchy, i.e., problematic policy preferences, unclear technology and fluid participation [

41].

MSF is increasingly popular as a framework for analysing policy processes in the EU, both at national and EU levels, e.g. [

21,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This includes analyses of EU-level energy and climate policy [

47,

48,

49]. EU-level analyses pose methodological challenges since the EU context differs from the US context, for which MSF was originally developed. A comprehensive analysis of EU policy aiming to exploit the explanatory potential of MSF must address two issues: (i) define functional equivalents of the MSF elements in the EU and (ii) be explicit about how the causal mechanisms relate to these equivalents. There are two causal mechanisms: (i) events that open a policy window, and (ii) policy entrepreneurs’ coupling activities [

20].

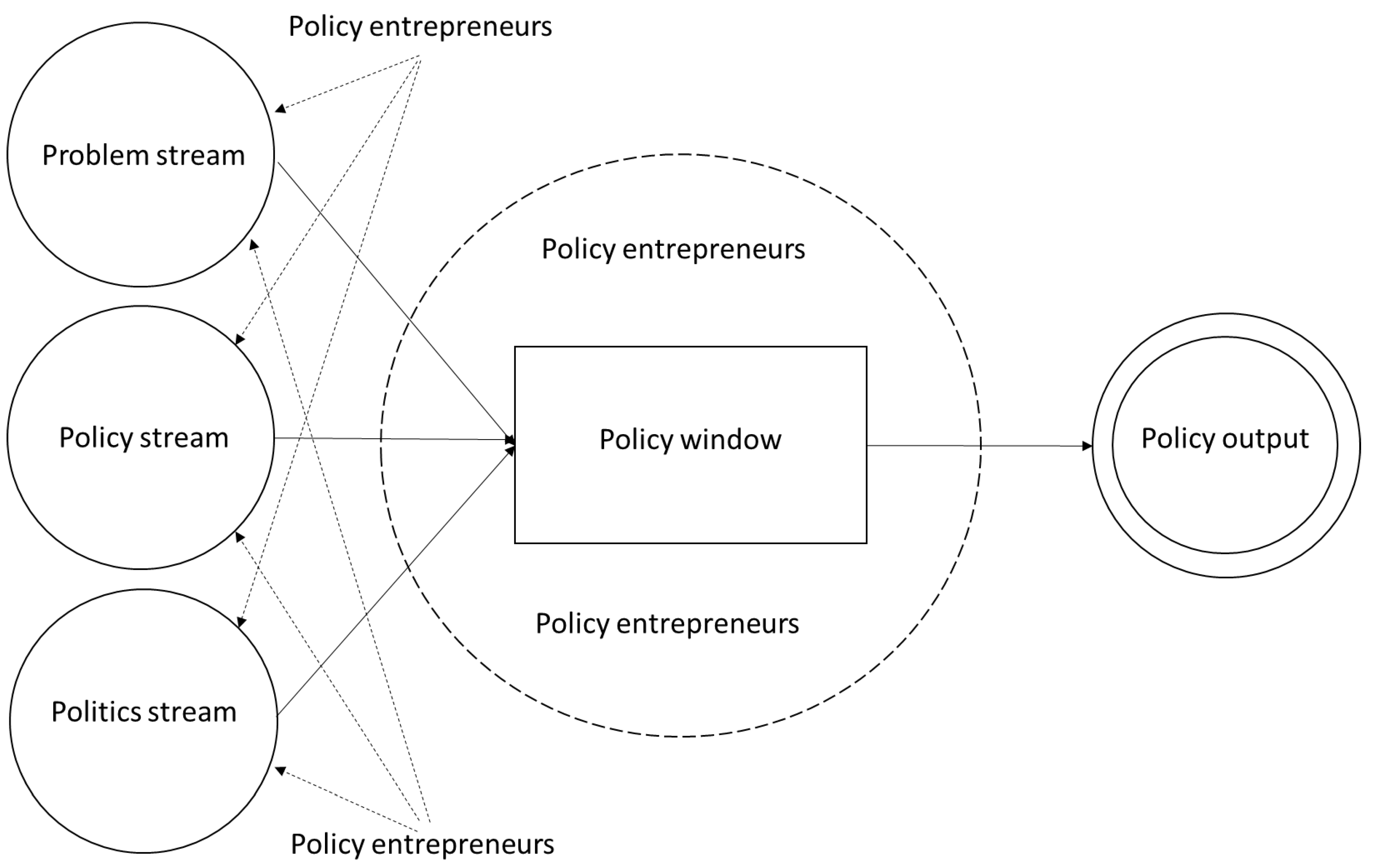

The analytical approach is to explore three types of structural factors, a problem stream, a policy stream and a politics stream, which, when connected, have the power to change policy (

Figure 1). The three streams are assumed to be independent, meaning that the stream dynamics differ and the streams do not affect each other [

45].

2.1.1. The Problem Stream

The

problem stream highlights the need for a new policy on the agenda. It is something seen as a public interest matter requiring attention, e.g., climate change. The problem stream includes mechanisms of (i) problem recognition (indicators showing a problem, e.g., high GHG emissions, high energy use, and energy efficiency potential that remains untapped), (ii) focusing events (e.g., gas supply disruptions and energy price spikes), and (iii) feedback concerning previous policy programmes (e.g., EC review reports, often inscribed in legislative acts). In MSF, problems are seen as socially constructed, not as evident facts [

20,

22]. It is mainly policy entrepreneurs or other experts that identify and frame problems. Depending on who they are or who they represent, they may or may not account for the public opinion [

50]. The problem stream is ripe for coupling to the policy stream or politics stream if a policy entrepreneur is successful in framing it as problematic, and the issue is seen as problematic in the policy community.

2.1.2. The Policy Stream

The

policy stream brings potential policy options to the agenda and formulates suitable proposals to address the socially constructed problem. These policy options are formed by the values of acceptability in the formulation, the technical feasibility of the proposed solution, resources such as competences, the existence of technical capacities and structures to manage the policy and a network supporting it [

22]. To gain acceptability in EU policymaking, at least the EC undertakes public consultations targeting academia, business associations, companies, consumer organisations, environmental organisations and other NGOs, EU citizens and trade unions. The policy stream is ripe for coupling if at least one technically feasible policy idea addressing the problem identified available, which is discussed by the policy community.

How a condition is framed as a problem influences how people think about the problem [

51]. This enables coupling to certain policies but not to others [

44]. A policy option must be promoted by policy entrepreneurs with resources, strategies, and access to the policy window where the streams can meet and form the policy community in the policy stream [

52]. Research on the policy process in the EU has shown that there is greater heterogeneity in EU policy communities than in national ones [

44,

53]. Differences in culture, economy, and politics between MSs make it unlikely that their governments agree on value acceptability, tolerable costs, normative acceptance, and receptivity.

2.1.3. The Politics Stream

The

politics stream is defined by the framing of decision-making, including political party ideology, interests, the national/EU mood and the institutional arrangements of decision-making. It has been argued that the politics stream in EU policymaking is ripe if the EC supports an issue through a political entrepreneur, e.g., the Commissioner of the relevant Directorate General who actively supports the idea in question [

21]. Herweg and Zohlnhöfer argue that the focus on the EC results from its formal monopoly on proposing legislation [

21]. But new or amended legislation could be initiated also by MSs in the Council, through Council conclusions, or the Parliament, through resolutions, requesting the EC to put forward legislation. The politics stream is more complex and scattered in the EU policymaking process than in national policymaking processes. In the EU, executive power is shared between MS governments in the Council, the European Council and the EC [

21]. The EP is the European counterpart of a national parliament.

2.1.4. Coupling of the Streams

According to MSF, policy change occurs when the three streams are coupled. Coupling is the central mechanism in MSF, connecting the three streams to achieve policy change, stasis or reversal. The coupling of streams occurs when stakeholders act as

policy entrepreneurs [

22,

54,

55]. Policy entrepreneurs exploit opportunities to influence policy outcomes to promote their own goals without having the resources necessary to achieve this alone. Policy entrepreneurs, as individuals or collectives, attempt “to transform policy ideas into policy innovations and, hence, disrupt status quo policy arrangements” ([

55], p. 945). They are central actors in political agenda setting and for policy change, as they ‘soften’ the political system for certain ideas and ensure that there are packages of problems and policies that are ready when there is a policy window of opportunity to put the problem on the agenda [

54].

Section 2.2 provides a more in-depth description of policy entrepreneurs.

Coupling of streams is more likely when so-called

policy windows are open, defined as “a fleeting opportunity for advocates of proposals to push their pet solutions, or to push attention to their special problems” ([

22], p. 37). At that time, policy entrepreneurs can successfully push forward their respective ideas, “coupling solutions to problems” and “both problems and solutions to politics” ([

20], p. 21). Policy windows can open by a push from the problem stream or the politics stream but not the policy stream [

21,

22]. The problem stream pushes the policy window when indicators change significantly. The politics stream pushes the window with changes in partisan composition in parliaments and governments. In the multilevel governance setting of EU policy, a policy window can also be opened from above (international events) or below (national events) [

49].

2.2. Policy Entrepreneurs

The concept of

policy entrepreneurs was introduced by Dahl [

56] and popularised by Kingdon, who defines them as “advocates who are willing to invest their resources – time, energy, reputation, money – to promote a [policy] position in return for anticipated future gain in the form of material, purposive, or solitary benefits” ([

20], p. 179).

2.2.1. Motives of Policy Entrepreneurs

Drawing on Kingdon’s definition, most scholars have assumed that policy entrepreneurs are instrumentally rational [

57], motivated by a “desire for power, prestige and popularity, the desire to influence policy, and other factors in addition to any money income derived from their political activities” ([

58], p. 11) or “satisfaction from participation, or even personal aggrandisement” ([

59], p. 123). However, policy actors are rather boundedly rational and motivated by cognitive rationality, i.e., their beliefs, values and ideas [

60,

61]. Thus, policy entrepreneurs may engage in policy advocacy to prevent opponents with conflicting beliefs from securing ‘evil’ policies, triggering a ‘devil’s shift’ [

62]. Arnold argues that “[o]ppositional factors, by triggering a value-laden, devil shift-influenced fear of a threat to a desired policy goal, can catalyse policy entrepreneurship” ([

63], p. 26).

2.2.2. Being a Policy Entrepreneur

Initially, only individuals, such as elected politicians, public officials, academics and experts, were considered policy entrepreneurs, but research on policy processes in the EU has included organisations as policy entrepreneurs. Thus, policy entrepreneurs also include companies, business associations, NGOs, think-tanks, other IGs, political parties and public institutions, e.g., the EC, the Council, the European Central Bank, or national, regional or local governments and authorities [

21,

44,

54,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. Zito even refers to “collective entrepreneurship” [

69,

70], in which advocacy coalitions act as policy entrepreneurs to formulate individual policies in a certain policy area. Overall, policy entrepreneurs can come from the public and private sectors as well as civil society.

For theoretical and analytical reasons, policy entrepreneurship must be distinguished from other political advocacy actions. Boasson and Huitema ([

71], p. 1351) argue that “privileged actors in powerful positions deploy[ing] the regular tools at their disposal and merely do[ing] their job, /…/ are not demonstrating entrepreneurship”. They argue that policy entrepreneurship can be deployed by actors in and out of government – elected officials, lobbyists or civil servants – at different levels and in different domains if they are “persistent and skilled actors who launch original ideas, create new alliances, work efficiently or otherwise seek to ‘punch above their weight’” ([

71], p. 1344, [

72]). For instance, the current EC President Ursula von der Leyen and former EC Commissioner Frans Timmermans were described as policy entrepreneurs for launching the

European Green Deal (EGD) in 2019 [

49,

73], but this can be questioned since EGD was presented only one month after their entry into office and the proposal was prepared by Commission services long before. Hence, it may have been public officials in the EC like directors and their staff that were the true policy entrepreneurs. But in all, the EC as an institution can be regarded as a policy entrepreneur.

2.2.3. Strategies of Policy Entrepreneurs

The strategies used by policy entrepreneurs are the lines of action taken to reach their aims, the latter of which fall into two categories [

71]:

Structural entrepreneurship: acts aimed at overcoming structural barriers to enhancing governance influence by altering the distribution of formal authority and factual and scientific information; and

Cultural-institutional entrepreneurship: acts aimed at altering or diffusing people’s perceptions, beliefs, norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews, or institutional logics.

Analysing the scholarly literature, Aviram et al. [

74] identified 20 strategies and three traits of policy entrepreneurs, the latter being trust building, persuasion, and social acuity. Theses may vary with respect to the target audience, level of government at which the policy entrepreneurs operate, sector, and policy entrepreneurs’ professional roles, timing, number and types of actors involved, relationship to development of international politics, etc. [

74] Brouwer and Huitema proposed four categories of strategies, i.e. approaches to policy advocacy [

75,

76], which I will apply in my analysis (

Table 1):

For structural entrepreneurship, three strategies are particularly important: (i) creating and working in networks and advocacy coalitions, (ii) strategic use of decision-making processes, and (iii) strategic use of information [

71]. Through networking, a policy entrepreneur learns the worldviews “of various members of the policymaking community” ([

79], p. 739), which enables policy entrepreneurs to persuade policy actors with high levels of legitimacy or authority to join [

80]. The strategic and smart use of decision-making procedures and venues relates to timing and thus launching the policy idea when there is an open policy window [

20]. Finally, policy entrepreneurs can reach their aims by assembling new evidence and making novel arguments [

81], carrying ideas [

82] that serve as ‘coalition magnets’ [

83] to convince an appropriately powerful coalition of supporters to back the proposed changes [

71,

84]. This is done either by manipulating who obtains what information, if information is distributed asymmetrically and information is scarce [

85,

86], or by strategic manoeuvring, such as providing as little information as possible to one’s likely opponents [

87].

For cultural-institutional entrepreneurship, framing problems and policy options is the most important strategy for making people positive about the ideas coming from the entrepreneur and negative about existing and competing policy or governance arrangements [

71]. To persuade others, a policy entrepreneur must consider the perspectives of various actors and create meanings and frames that appeal to them [

88]. Policy entrepreneurs deploy ‘outsider tactics’ by shaping public discourse on problems and policy solutions or ‘insider tactics’ by working with policymakers to design regulations [

89,

90].

2.2.4. Success of Policy Entrepreneurs

Not all policy entrepreneurs are successful [

71,

91]. Success is defined in different ways. For some, a policy entrepreneur is successful if the advocacy leads to changes in other policy actors’ policy preferences [

92]. This can be compared to policy learning [

93]. For others, a policy entrepreneur is successful if it influences agenda setting in such a way that the policy entrepreneur’s pet issue is considered by policymakers [

27,

79]. However, another view is that a policy entrepreneur is successful if she has an actual influence on policy and governance [

71], e.g., adoption of specific policy measures the policy entrepreneur sought [

79,

94,

95,

96]. What is deemed success depends on the aim of the policy entrepreneur agency.

Mintrom and Norman [

78] assume that success is more likely for a policy entrepreneur who has more characteristics that define her as such or who deploys entrepreneurial strategies with greater frequency or intensity cf, [

97]. Most policy entrepreneurs strive for policy innovation, which consists of initiation, diffusion, and the evaluation of effects that such innovations create, the latter requiring analytical capacities [

98]. These challenges are central to the work of policy entrepreneurs. It is their willingness to use their positions for leverage and for aligning problems and solutions that increase the likelihood of policy change [

78]. The ability of policy entrepreneurs to successfully promote policy innovation also depends on their ability to identify relevant competencies and develop and effectively deploy them [

99,

100]. In addition, a successful policy entrepreneur must understand the concerns of the actors they seek to persuade, use social acuity to build teams, networks, and coalitions, be knowledgeable to strategically disseminate information, and be organising, corresponding to political activation and involving civic engagement [

74,

78,

91]. Anderson et al. add that the influence of policy entrepreneurs lies not only in their ability to define problems and build coalitions but also in their ability to provide new and reliable information to elected officials [

101].

3.1. Previous Research on EE1 and Policy Entrepreneurs in EU Climate and Energy Policy

3.1.1. Findings on EE1

Analysing the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ package, which introduced EE1 in EU policy, Rosenow et al. found that it falls short of comprehensively reflecting EE1 [

102]. It was part only of the proposal for the Governance Regulation. Chlechowitz et al. assessed the implementation of EE1 in 14 MSs – before the principle was made binding in EU policy [

103]. They found that fundamentals of the EE1 are understood and realised by MSs, but that most MSs fail to ensure an equal treatment between supply and demand-side resources and neglect the ‘multiple benefits’ associated with energy efficiency improvements. Mandel and colleagues outlined the potential role of EE1 as a decision-making tool for prioritising demand-side actions over supply-side actions when these actions provide greater value to society [

104,

105,

106]. They argue that an “‘EE1-compliant’ regulation guarantees that consumers can offer their flexibility and get compensated at market value and requires that distribution systems operators use them whenever they provide more net benefit that network investment” ([

106], p. 11). The policy process and the political meaning-making of EE1 have been analysed using discourse analysis and the ACF [

25,

26]. These analyses revealed a conflict among EU legislators and other stakeholders whether EE1 should aim at reaping ‘multiple benefits’ of energy efficiency or contributing only to climate change mitigation. Interdiscursive communication and policy learning in deliberative negotiations across belief systems settled the dispute, and actors agreed in line with the multiple benefits discourse. For policy learning, von Malmborg found that the level of politicisation and polarisation as well as the mandates of the lead negotiators of the Council and the EP in EU trilogue negotiations are important factors enhancing or inhibiting policy learning on energy efficiency policy [

34].

3.1.2. Findings on Policy Entrepreneurs

Regarding policy windows in EU policy, Herweg argued that the start of an EC term of office opens a window [

44]. This is because the EC has formal privileges for initiating EU legislation. For the same reason, the EC is considered a natural policy entrepreneur [

21,

44,

47,

48,

66,

107] . Kreienkamp et al. analysed transformative change in EU climate policy, emphasising “the importance of creating windows of opportunity but also seizing synchronistic moments when such windows open from political situations ‘above’ or ‘below’” ([

49], p. 735). The agency of policy entrepreneurs in framing climate and energy policies in the EU has been analysed with slightly different focus and findings [

47,

48,

49,

108]. Since approximately 2005, the EC has acted to shift political norms, successfully framing import dependency as a problem requiring an EU-level solution [

47]. Palmer [

108] found that persuasive framing enabled the policy entrepreneur to impinge on agenda-setting processes, while boundary work enabled the policy entrepreneur to forfeit an existing policy considering widespread criticism. The 2009 EU energy and climate policy package gathered support among stakeholders from framing it as a way for the EU to gain leadership in the green energy transition [

48]. Von Malmborg analysed the role of policy entrepreneurs in the policy process leading to the adoption of the world’s first legislation to curb GHG emissions from maritime shipping in 2023 [

35]. He found that activistic advocacy by an environmental NGO, framing decarbonisation as an opportunity to gain competitiveness and building a broad coalition with NGOs, business associations and progressive companies in the shipping value chain, gathered enough support in the Council and the EP to stand the ground against heavy lobbying from the fossil fuel industry that opposed decarbonisation to maintain competitiveness. This confirms the importance of persuasive framing and coalition building as key strategies for policy entrepreneurs.

In all, there is limited research on EE1, particularly on the policy processes and politics, and there is a research gap regarding the agency of central actors—policy entrepreneurs—in the policy process.

4. Method and Material

This paper uses MSF and theory on policy entrepreneurs as a theoretical lens to fill the knowledge gap on the policy process and politics of EE1. Arnold et al. [

109] recently criticised policy entrepreneurship scholars for paying too little attention to the methodological question of how to empirically identify policy entrepreneurs. They argue that scholars generally identify policy entrepreneurs by event-based or process-based approaches “asking elites and experts to point them out, querying secondary sources, surveying possible entrepreneurs, and focusing on high-profile advocates” or “using secondary sources” ([

109], p. 659), using a “I know it when I see it” standard to distinguish policy entrepreneurs from other policy actors (p. 660). Using elite or expert input to identify policy entrepreneurs may overrepresent the prevalence of policy entrepreneurs while overlooking less connected or less expert policy actors trying to influence policy. Using elite or expert input is also questionable since it implies that the researcher defines and decides what the ‘elite’ is and who are the ‘high-profile advocates’.

4.1. Identifying Policy Entrepreneurs

In this study, I define policy entrepreneurs as “individual or organisational change agents who are strategically and entrepreneurially involved in framing and developing innovative policies, presenting them well-packaged to policymakers or political executives”. To avoid the pitfalls mentioned above, a stepwise process suggested by Arnold et al. [

109] was applied for identifying and distinguishing policy entrepreneurs once potential policy entrepreneurs were identified:

One marker of significant resource investment (time or money),

AND: at least one entrepreneurial goal,

AND: at least one entrepreneurial strategy or characteristics,

AND: at least one network partner.

To screen potential policy entrepreneurs in the case, written responses to the EC’s public consultation, reports from negotiations in the Council, and reports in the pan-European online newspaper

Euractive, writing about developments in EU policy, were analysed. Additional data on potential policy entrepreneurs was collected from reports and policy papers/briefs posted on official websites of different policy actors. The screening was also facilitated by previous studies of advocacy and discourse coalitions [

25,

26]. The screening identified approximately 400 policy actors including business associations, companies, environmental NGOs, think-tanks, national governments and authorities and citizens. Out of these, 30 policy actors were identified to be more active and vocal, provided more reports and policy briefs, and led the work in different policy networks and advocacy coalitions. Only these 30, not all 400 potential policy entrepreneurs, were screened with questions about resources, goals, strategies and network partners. After this analysis, four policy entrepreneurs from the public, private and civil society sectors who met the stepwise criteria were identified:

The European Commission,

Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP)

1,

European Climate Foundation (ECF)

2, and

Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group (EEFIG)

3

4.2. Collection and Analysis of Data

For data collection on strategic agency of policy entrepreneurs, semi-structured interviews were combined with qualitative text analysis of official and confidential documents related to agenda-setting, advocacy and formal negotiations on EE1 (

Table 2). Three interviews were held with key individuals in EC DG ENER and RAP acting as policy entrepreneurs. These persons held positions such as heads of units, policy officers or deputy directors/associates and were particularly important for driving policy entrepreneurship, but they had supporting teams in their organisations without which they could not have acted as policy entrepreneurs. In addition, one interview was held with the Swedish energy counsellor who acted as chair of the Council energy working group during final trilogue negotiations between the Council, EC and EP in spring 2023, leading to political agreements and adoptions of the recast EED. The interviewees were asked about their motifs and entrepreneurial strategies. The participants were also asked about their views on their opponents’ strategies in advocacy. The interviews were not recorded, but notes were taken. As for qualitative text analysis, policy documents from the EC, reports and policy papers from RAP, ECF and EEFIG, and policy papers from different MSs, were analysed looking for perceptions of problems and positions on policy proposals.

Decision-making in the Council and tripartite negotiations (i.e., trilogues) between the Council, the EC and the EP is secluded [

128,

129]. It is difficult for scholars to obtain access to negotiations, which is why most research on EU policymaking draws on voting results. Through cooperation with the Swedish Ministry for Infrastructure, access was given to reports of Sweden’s Permanent Representation to the EU to the Government Offices of Sweden from 18 meetings of the Council’s Energy Working Party (EWP), three technical interinstitutional meetings and two political trilogue meetings. Getting of Sweden’s reports is important since Sweden held the rotating Council Presidency during the final trilogue negotiations when the deal on EED was done by the Council and the EP. Such sharing of confidential information for research purposes is generally very rare [

25,

26,

34]. These provided a unique opportunity to analyse the positions and changes in the positions of MSs, the Council and the EP. This is a methodological merit. Since the reports from the negotiations were used to formulate Sweden’s negotiation strategies, they would not falsely convey the positions of others to the Government Offices of Sweden. Thus, the findings were not systematically affected by bias.

These documents include data on the perceptions of problems and policy options of the different actors involved in the policy process. They also include encounters of the policy process itself and the politics therein.

Data coding and analysis were performed manually in relation to problem framing, policy proposal, beliefs and motifs for policy change, entrepreneurial approaches (structural or cultural-institutional, cf. [

71]), entrepreneurial strategies (see

Table 1 for a categorisation of different strategies), and kinds of impacts/outputs.

5. Results

5.1. The Problem Stream

Energy efficiency is not considered a problem but rather a solution to different problems. The most direct problems are low energy performance or high energy intensity, i.e. using a lot of energy to provide a service [

25]. Thus, improving the energy efficiency of products, processes and the entire economy has been a policy issue in the EU for about 50 years. Energy efficiency policy was introduced in the EU with the 1970s oil crisis [

130,

131]. Since then, several policies on the energy efficiency of different sectors and products have been adopted and implemented. EED, first adopted in 2012 [

132], amended in 2018 [

133], and recast in 2023 [

14], constitutes the overarching legislation, setting overall targets and including binding provisions on energy efficiency in different sectors. It is complemented with sector legislation for energy performance of buildings as well as energy performance and energy labelling requirements for electrical and energy related products and tyres.

The framing of EU energy efficiency policy, made by the EC and other EU institutions, has expanded over the years, from initially being a solution to the security of energy supply, to an important solution in climate change mitigation and, most recently, to alleviate energy poverty [

130,

131]. The focus on climate change mitigation has been a goal of EU energy efficiency policy since the late 1990s [

131], taking off with the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and increasingly important with the 2015 Paris Agreement. There are no polls on EU citizens views on energy efficiency, but a Eurobarometer poll from May 2024 showed that about 80 % of the public agree that climate change is an important issue in public policy and that EU should have legislation to mitigate climate change [

134]. The need to alleviate energy poverty and enhance energy security became a key problem for EU citizens meeting rising energy bills after Russia’s war on Ukraine since 24 February 2022 and the energy crisis exacerbated by EU sanctions on Russia [

135].

Prior to the EC, with then President Jean-Claude Juncker, presenting in 2015 an Energy Union strategy [

8], the Brussel-based think-tank RAP and EEFIG, an EU-wide expert group on energy efficiency finance, stressed that energy efficiency is not only the most cost-effective way to reduce GHG emissions, but also necessary for large-scale development and integration of renewable energy in the energy system to control costs and maximise consumer welfare [

121,

122].

As set by the EC, the Council and the EP in official documents, EU energy efficiency policy is increasingly framed as a solution to economic problems, security of supply problems, environmental problems and social problems [

131], with the EC referring to the

multiple benefits of energy efficiency, i.e. ([

11], p. 29):

“Improving energy efficiency throughout the full energy chain, including energy generation, transmission, distribution and end-use, will benefit the environment, improve air quality and public health, reduce GHG emissions, improve energy security by reducing dependence on energy imports from outside the EU, cut energy costs for households and companies, help alleviate energy poverty, and lead to increased competitiveness, more jobs and increased economic activity throughout the economy, thus improving citizens’ quality of life”.

With the 2021 proposal for a recast EED, the EC added more problems related to energy efficiency that needed to be addressed by EU policy. The first is the slow uptake of energy efficiency measures; the second is the unequal treatment of energy efficiency and demand-response measures on the one hand and supply-side measures on the other [

11,

12,

110,

111]. The latter was inspired by the advocacy of RAP, EEFIG and ECF to introduce EE1 in EU policy.

5.1.1. Energy Efficiency Gap

The EC claimed that there remains a large, untapped potential for cost-efficient energy efficiency in the EU [

12], which calls for “further promotion of energy efficiency actions and the removal of barriers to energy efficient behaviour, including for investments” ([

11], p. 15). Knoop and Lechtenböhmer [

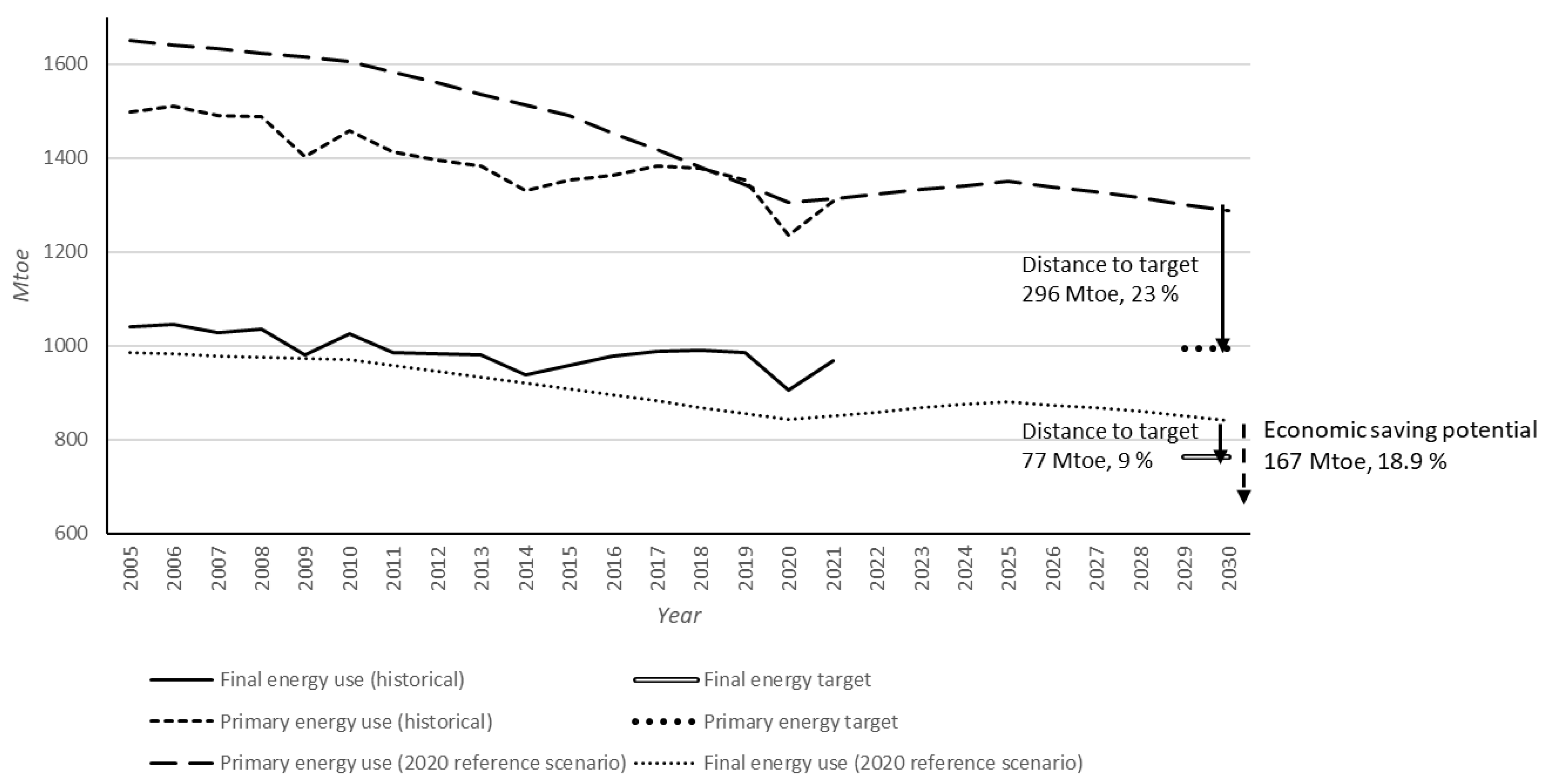

136] estimated the final energy savings potential in the EU up to 2030. Assuming low policy intensity, energy savings between 10–28 % could be realised compared to baseline development. With high policy intensity, the potential is 7–44 %. More recent estimates revealed that the 2030 technical potential for final energy savings across the residential, commercial, industrial and road transport sectors is 200 Mtoe, corresponding to 22.6 %, while the economic savings potential is 167 Mtoe or 18.9 % [

114,

137]. The economic potential is twice as large as the energy savings required to meet the 2030 target (

Figure 2), but policies are needed to realise this potential [

11,

12].

5.1.2. Equating Energy Supply and Demand

The importance of demand-side measures, including user flexibility follows new challenges facing the transition to a clean energy system to ensure a secure and affordable energy supply. To meet these challenges, RAP, ECF, EEFIG and EC, argue that energy demand- and supply-side measures must compete on equal terms. Demand-side flexibility can provide “significant benefits to consumers and to society at large and can increase the efficiency of the energy system and decrease the energy costs, for example by reducing system operation costs resulting in lower tariffs for all consumers” ([

11], p. 31).

The problem stream related to EE1 began to ripen with the communication on the ‘Energy Union’ [

8] and the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ package [

9], which included the amended EED and the new Governance Regulation. The EGD [

140], including the ‘Energy Systems Integration Strategy’ [

111], the strategy for stepping up the EU’s climate policy ambition [

112], the ‘European Climate Law’ (ECL) [

141] and the ‘Fit for 55’ package [

13] together with the EC’s ‘REPowerEU Plan’ [

142] and the associated ‘EU Save Energy Strategy’ [

143], made it fully ripe to outline why an enhanced energy efficiency policy with a binding EE1 was needed.

5.2. The Policy Stream

5.2.1. The Commission Proposal

The introduction of the EE1 narrative in EU energy and climate policy was strongly influenced by the proactive policy entrepreneurship of the Brussels-based think-tank RAP, environmental NGO ECF and EEFIG. They provided several reports to the EC in the preparation of the ‘Energy Union’ strategy and the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ package, e.g. [

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125]. EEFIG, working towards the financial sector to increase investments in energy efficiency, stressed that energy efficiency investments are strategically important for the EU and that a binding EE1 with ‘multiple benefits’ framing can help the sector. Regarding the role of EE1, Bayer ([

125], p. 2) mentioned that:

“It is a necessary decision tool to ensure cost-effective decarbonisation of the economy, including facilitating the transition to a future powered by renewable energy, and to exploit the multiple benefits of energy efficiency. It asks the following question: Would it be better to help customers invest directly in energy-saving actions and demand-side response, rather than paying for supply-side actions, fuels, and infrastructure? The result is a more cost-effective allocation of resources across the energy system.”

The EC proposed in July 2021 to strengthen the provisions on EE1 and regulate it for the first time in a separate article of the EED, with binding requirements for implementing measures in MSs [

11]. MSs should ensure that actors take energy efficiency solutions into account in policy, planning and

major investment decisions in energy systems and in sectors that affect energy supply and energy demand, including subsidised housing. The EC did not clarify what was meant by

major investments.

According to the EC [

11,

110], the proposal for a recast EED was an important step toward climate neutrality by 2050, where energy efficiency will be treated as an ‘energy source in itself’, corresponding to the IEA narrative of energy efficiency as the ‘first fuel’. EC also claimed that EE1 is also important for reaping the ‘multiple benefits’ of energy efficiency. The central role of energy efficiency is supported by EE1. For the role of EE1 in EU energy and climate policy, the EC proposal states that ([

11], p. 29-30):

“The energy efficiency first principle is an overarching principle that should be taken into account across all sectors, going beyond the energy system, at all levels, including in the financial sector. Energy efficiency solutions should be considered the first option in policy, planning and investment decisions when setting new rules for the supply side and other policy areas. The Commission should ensure that energy efficiency and demand-side response can compete on equal terms with generation capacity. Energy efficiency improvements need to be made whenever they are more cost-effective than equivalent supply-side solutions. This should help the Union exploit the multiple benefits of energy efficiency, particularly for citizens and businesses. Implementing energy efficiency improvement measures should also be a priority in alleviating energy poverty.”

The stream became ripe when the EC presented its proposal to the EP and the Council in 2021. To facilitate the implementation of EE1, the EC issued a recommendation [

115] and guidance [

116] to MSs on how the principle should be applied in different settings in September 2021.

5.2.3. Views of Interest Groups and Citizens

During the winter of 2020–2021, the EC organised a public consultation to inform the proposal for a recast EED. A total of 344 answers were collected, most of which agreed on making EE1 binding [

113]. Two thirds of the answers came from business associations and companies, while different kinds of NGOs accounted for 11 % of the answers. Public authorities provided 7 % of the answers, and EU citizens accounted for 6 %, which is the same amount as consumer organisations, research institutions and trade unions taken together [

113]. No citizens had views on EE1, but more than 150 IGs requested that EE1 be applied to all relevant national energy policies related to the whole energy system. The views of RAP, ECF and EEFIG and the proposal of EC were supported by other IGs, particularly the European Alliance to Save Energy (EU-ASE) and the Coalition for Energy Savings (CfES), the latter an environmental NGO gathering more than 500 business and civil society associations, 200 companies, 1500 cooperatives and 2500 cities in favour of energy efficiency. EU-ASE and CfES stressed that the “EE1 principle should be systematically and consistently applied in EU law” ([

144], p. 27). CfES also stressed that the reference to

major investment decisions should be deleted [

145].

Not all the IGs favoured EE1. Large state-owned energy utilities such as České Energetické Závody and Electricité de France, Eurelectric (the EU Association for Electricity Producers), VIK Verband der Industriellen Energie- und Kraftwirtschaft (a German business association), Swedish Forest Industries, Jernkontoret (the business association for Swedish iron and steel industries), and Agoria (a Belgian technology industry association) were highly critical. They critised that energy efficiency should be given priority over other measures to mitigate climate change, that EE1 would make climate change mitigation less cost-efficient.

5.3. The Politics Stream

Policy- and decision-making on EU legislation follow the Ordinary Legislative Procedure [

146], in which the EC has a monopoly to propose legislative reforms. The council and the EP negotiate and decide on a negotiation mandate for the trilogue negotiations between the Council, the EP and the EC, in which the Council and the EP have to reach an agreement by consensus [

128,

147]. In trilogue meetings, EU institutions are represented by negotiating delegations tasked with facilitating and finding a legislative compromise between institutions.

As for the EU mood, there is a constant debate on subsidiarity and the need for collective action at the EU level. MSs often contest EU energy and climate policy, including energy efficiency, based on either sovereignty (subsidiarity claims) or substance [

31,

148,

149]. MSs usually want flexibilities related to national circumstances. For energy efficiency policy, the EU does not hold exclusive competence. Although MSs maintain significant sovereignty over energy policy, the EC has achieved increasing competencies in the internal dimensions of EU energy policy [

17,

47], which since 2009 is based on Article 194 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) [

150]. EU climate policy is based on Articles 191–193 of the TFEU. In response to the subsidiarity principle, the EC claimed in its proposal for the recast EED the need for action at the EU level but also that there is flexibility for MSs:

“Given the higher climate target, Union action will supplement and reinforce national and local action towards increasing efforts in energy efficiency. The Governance Regulation already foresees the obligation for the [EC] to act in case of a lack of ambition by the [MSs] to reach the Union targets, thus de facto formally recognising the essential role of Union action in this context, and EU action is thus justified on grounds of subsidiarity in line with Article 191 of [TFEU]” ([

11], p. 10).

“The Energy Efficiency Directive essentially sets the overall energy efficiency objective but leaves the majority of actions to be taken to achieve this objective to the Member States. The application of the [EE1] principle leaves flexibility to the Member States” ([

11], p. 12).

The politics stream ripened through parallel negations in the Council and the EP, followed by the inter-institutional trilogue negotiations. Herweg suggested that the politics stream counts as ripe if the EC supports an issue [

44]. However, a more recent study of the policy process related to ‘Fit for 55’ indicates that it is not enough for the EC to support an issue for the politics stream to be ripe [

35]. The Council and the EP need to have adopted their respective negotiation mandates for the trilogues for the politics stream to be ripe. The EC is an agenda-setter and policy entrepreneur proposing legislation, but the Council and the EP are the co-legislators in the EU and the ones that negotiated and decided on the recast EED and EE1.

5.3.1. Council Negotiations

The decision on the Council position, so-called general approach, on EE1 was made by the Council of Energy Ministers, but most negotiations took place at the attaché level in EWP. Negotiations took off slowly in September 2021 under the Slovenian Council Presidency. In spring 2022, under the French Presidency, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Sweden asked for more MS flexibility. Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia and Malta, constituting a blocking minority

4, argued that EE1 should cover only the public sector. Six MSs claimed that

major should be clarified. Austria and Latvia proposed that only projects exceeding 50 million euros each or 75 million euros for transport infrastructure projects should be included. Finland, Germany and Greece proposed that the economic thresholds for the size of investments to be covered should be tenfold to 500/750 million euros. Overall, MSs had quite different views on the scope of a binding EE1.

In the negotiations, the rotating Council Presidency acted as an ‘honest broker’ [

151], facilitating reflexive debates over coalition borders. The Slovenian and French Presidencies managed to get the Council adopt a general approach in June 2022, in which the thresholds were set at 150 million euros for investments in general and 250 million euros for transport infrastructure investments [

117]. The blocking minority did not use its veto, and the decision was made unanimously. The reason for not using the veto was that the minority felt a pressure to remain respectable members of the EU policy process and changed stance symbolically without really changing beliefs, cf. [

34,

152]. Shooting down EE1 as a binding principle would render too much criticism. According to the Swedish energy counsellor, chairing the final negotiations in EWP, the EC guidance and recommendations on how to apply EE1 in different sectors [

115,

116] helped MSs overcome some hurdles and to better understand the implications of EE1. When the EP had adopted its report and trilogues with the EP and the EC were initiated, the Czech and Swedish Presidencies managed to adapt the Council negotiation mandate until the Council and the EP reached an agreement on the recast EED.

5.3.2. European Parliament Negotiations

In the EP, the EED dossier was handled by the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE), which appointed Niels Fuglsang (Denmark, S&D) as rapporteur

5. He presented his draft report [

119] in late February 2022. He proposed increasing the scope of EE1 from

major to

all relevant energy-related planning, policy and investment decisions in all sectors, including the public and private finance sectors. The need to strengthen the role of EE1 was also stressed by the rapporteur of the EP Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI), Eleonora Evi (Italy, Greens/EFA). In mid-July 2022, ITRE voted for adoption of the proposals of the rapporteur, with minor amendments. The proposal was supported by the EPP (conservatives), S&D, Renew Europe (liberals) and the Greens/EFA. In mid-September 2022, the EP plenary adopted the final report with the EP negotiation mandate [

120].

5.3.3. Trilogue Negotiations

Trilogue negotiations were initiated under the Czech Council Presidency in October 2022 and finalised during the Swedish Presidency in March 2023. In commenting on the EP position, a handful of MSs wanted to maintain the threshold of the Council’s general approach. However, ten MSs indicated that they could be flexible to lower the threshold, including more projects, decisions, and investments. The EC argued that higher thresholds would reduce the scope of the application and therefore not align with the purpose of EE1. EC was beneficial to MSs wanting to make compromises. After several political trilogue meetings, characterised as deliberative negotiations [

26], an agreement was reached between the Council and the EP in March 2023. The agreement implied that EE1 shall be applied in the public and private sector on policy, planning and investment decisions exceeding 100 million euros each and 175 million euros each in the transport sector. In the trilogue negotiations, the Swedish Council Presidency acted as an honest broker and chaired the meetings and drafted most compromise texts, forcing debates and facilitating reflexion on the meaning and scope of the EE1 principle. The Swedish Presidency managed to bridge political conflicts to get a deal with the EP, where the EP let go of its position that

all projects and investment decisions should be covered by the EE1 principle and thresholds were included.

6. Analysis and Discussion

6.1. Opening the Policy Window

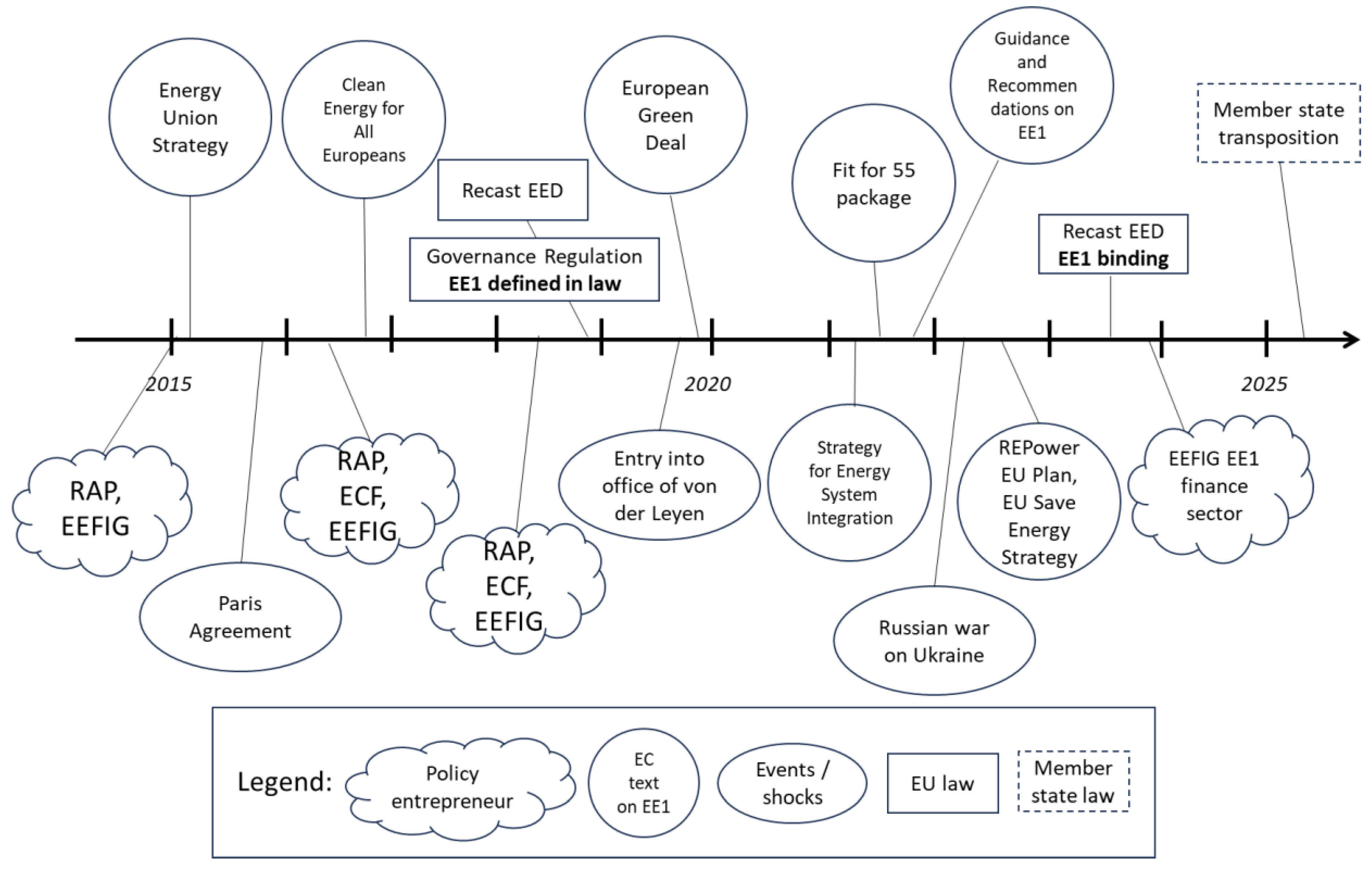

The policy discussion on EE1 was introduced in the EU with the ‘Energy Union’ communication in 2015. In 2016, the EC proposed introducing EE1 as a guiding principle in EU legislation with the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ package [

9]. EE1 could have been included in the EED, which was to be amended by then. However, there was a lack of politically understandable problem framing in 2015 and 2018, and no policy window opened for making EE1 binding. Politicians in Brussels and EU capitals were not receptive to the ‘problem’ framed by RAP, ECF and EEFIG as techno-economic needs for a systems approach to energy policy and the merits of consumer flexibility and demand-side management. Consequently, EE1 was only defined in the Governance Regulation, without requirements for application in practice. The timeline for introducing the EE1 narrative to EU energy and climate policy is presented in

Figure 3.

Following a sequence of strategy documents part of the EGD, e.g., the Energy Systems Integration Strategy [

111] and the strategy for stepping up the EU’s climate ambitions [

112], it took until 2021 before the EC presented a proposal to make EE1 binding. This time as a separate article in the recast EED, with binding requirements for application in MSs.

6.1.1. External Events

Now, the policy window started to open by a push from a revised problem stream, with more understandable problem narratives. First, the Paris Agreement targets limiting the temperature increase to 1.5–2 °C above preindustrial levels and consequential demands for extensive GHG emission reductions. This led the EC to present the EGD and the EU to adopt the ECL. Second, and more acutely, Russia’s second war on Ukraine and the energy crisis that followed EU sanctions on Russia reducing imports of natural gas [

135] led the EC to present the ‘REPowerEU Plan’ [

142] and the associated ‘EU Save Energy Strategy’ [

143], which both stressed the need for stronger energy efficiency policy. These two external ‘events’ or ‘external shocks’ from above are examples of the importance of “seizing synchronistic moments when such windows open from political situations ‘above’ or ‘below’” ([

49], p. 735). Third, indicators showed a large untapped economic potential for further energy savings. Fourth, the increased integration of renewable energy sources in the power system requires a systems approach to the green energy transition, with consumer flexibility and demand-side measures [

105].

These four factors added to the discourse about ‘multiple benefits’ of energy efficiency, where energy efficiency, like a Swiss army knife, helps solve all kinds of problems [

130]. This diffuse framing of energy efficiency policy, solving all kinds of problems, applied to help more politicians appreciate energy efficiency, is a reason why the economically profitable potential for energy efficiency was not being realised. Fawcett and Killip found that the ‘multiple benefits’ narrative is most persuasive when linked to the values and priorities of politicians, most of whom do not see an intrinsic value in energy efficiency [

30]. But if politicians do not understand the multiple benefits narrative, how could the public understand it? And obviously, many companies and business associations as well as MSs contested it. Kerr et al. found that the recognition of ‘multiple benefits’ may not equate with increased policy support [

29]. Instead, it is more likely that different rationales will have relevance at different times for different audiences. The focus on climate change and energy security is more understandable as problem narratives, although both the EC and EP equally emphasised the possibility of reaping ‘multiple benefits’ in the negotiations on EED and EE1. MSs in the Council, being closer to the public than the EP, considered mitigating climate change to be the most important problem for addressing energy efficiency [

25].

6.1.2. Internal Events

The policy window for EE1 also opened from an ‘internal event’ [

26], i.e., the entry into office of the new EC President Ursula von der Leyen and the EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson of Directorate General for Energy (DG ENER) in November 2019. Given the formal monopoly position of the EC to propose legislation, each beginning of its term of office can open a policy window [

44]. It was particularly important for policy entrepreneurs who advocated strengthening EE1, such as RAP, ECF, and EEFIG but also for other advocates of strong energy efficiency policy, such as EU-ASE and CfES, that EC President Ursula von der Leyen and Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson of DG ENER were receptive. The EC President gives political guidance to the EC, and DG ENER held the lead in formulating the proposal.

One month in office, von der Leyen presented the EGD as the EU’s response to the Paris Agreement [

140]. The EGD was also a response to bottom-up pressure from more ambitious climate policies, with unprecedented levels of public engagement in climate change, the success of the

Fridays for Future strikes, and NGOs such as the ECF [

49]. Von der Leyen coined EGD as “Europe’s man on the moon moment” [

153], and it is one of six priorities for the 2019–2024 period of the von der Leyen EC. It is the EU’s climate action plan and strategy for the green transition. Part of the EGD was the ECL, adopted in July 2021 [

141], stating that EU GHG emissions will be reduced by 55 % by 2030 compared to 1990 levels and that the EU, by 2050, will be the world’s first climate-neutral continent. The proposal on a recast EED was presented in July 2021 as part of a legislative policy package to make legislation on climate, energy, transport, land use and taxation ‘Fit for 55’ [

13]. Thus, the policy window was further opened by a push from the politics stream.

Taken together, these external and internal events pushed open a window of opportunity for the EC to propose making EE1 legally binding with the recast of the EED (

Figure 4).

6.2. Strategic Agency and Success of Policy Entrepreneurs

In MSF theory, policy changes occur when the three streams are ripe and being connected by policy entrepreneurs in an open policy window. For stream independence in the EE1 case, the problem and policy streams were characterised by arguing, while negotiations dominated the politics stream, despite the EC being present in all streams. Thus, stream independence was not violated.

Previous research on policy entrepreneurs in EU policymaking has focused on the EC, MSs and/or IGs from the private sector as policy entrepreneurs, e.g. [

21,

33,

44,

47,

48,

66,

107,

155]. Given the formal monopoly of the EC to put forward EU legislation, it was a ‘natural’ policy entrepreneur coupling the problem, policy and politics streams in the case of EE1. This confirms studies of EU energy policy integration [

47], the 2009 EU energy and climate package [

48], the relaunch of the EU economic reform agenda [

155], and the EU science and technology framework programme [

107]. In this case, the EC, through DG ENER, had been served with a policy solution (binding EE1) by RAP, ECF and EEFIG as primary policy entrepreneurs.

6.2.1. Motives

RAP, leading the work in the coalition, was motivated by a dedication to accelerating the clean energy transition through thought leadership, taking a systems perspective on energy policies traditionally addressed as silos, while ECF was motivated by a will to save the world from climate catastrophes and provide funding. EEFIG was dedicated to make financial institutions apply EE1 in sustainable finance [

127].

6.2.2. Strategies for Persuasion and Coupling

The different strategies used by RAP, ECF and EEFIG to persuade the EC (DG ENER), and then by EC to persuade MSs, the Council and the EP, as policy entrepreneurs in the policy process on making EE1 a binding principle with the recast EED, are summarised in

Table 3 and explored below.

RAP, ECF and EEFIG, acting as ‘advocate’ policy entrepreneurs, cf. [

91], used rather few strategies to reach a limited set of goals, and persuaded the EC to present transformative policy change. A key strategy was to frame problems and generate ideas by strategic use of information, including demonstration projects. This information was provided in reports, policy papers and meetings on how EE1 has been and can be implemented as well as its potential benefits. But they also published research papers in scientific journals to increase the legitimacy of their policy proposal. Analysing the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ policy package, which introduced EE1 in EU policy, RAP researchers found that it did not comprehensively reflect EE1 [

102].

ECF, EEFIG and RAP, the latter two with strong analytical resources, used so-called ‘salami tactics’

6 [

86] to inspire the EC to introduce the narrative of EE1 in EU policy, first in the Energy Union communication [

8], second in the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ package [

9], manifested in the ‘Governance Regulation’ [

10], and finally as a self-standing, binding article in the Recast EED [

14].

The coupling of streams mainly followed the mechanisms of ‘doctrinal advocacy’ [

86] or ‘problem-focused advocacy’ [

156], where the RAP, ECF, EEFIG and EC, as policy entrepreneurs, looked for adequate ways to frame the problem(s) that suited a given, what they considered a viable solution. EE1 was established as a nonbinding principle with the Governance Regulation, but for EE1 binding, the policy entrepreneurs had to look for better problem narratives than in 2016–2018 when the EED was amended, and the Governance Regulation was negotiated. Enabling coupling of the three streams, the EC was present in the Council negotiations and took part in the trilogue negotiations.

6.2.3. Success

RAP, ECF and EEFIG were successful in linking the problem and policy solution to part of the politics stream, influencing the EP rapporteur, calling for a very strong application of EE1, and creating room for negotiation with the Council to end up with a compromise. Overall, this finding echoes the findings of Ringel et al. ([

157], p. 9) that “especially hybrid stakeholders [such as EEFIG and CfES], combining industry, think-tanks and NGO actors, can take a strong role for consensus building” on EU energy efficiency policy. The finding that think-tanks and particularly civil society organisations can take the role of policy entrepreneurs is important, cf. [

35]. Kastner [

158] described the role of a polymorphous network of civil society organisations that was able to gain momentum after the financial crisis and to influence the financial reform process towards financial consumer protection. Kreienkamp et al. also identified targeted advocacy by environmental organisations towards the EC as a key ingredient in driving policy change related to EDG [

49].

As highlighted by Kreienkamp et al., the ‘hyperconsensual’ environment of EU politics poses a great challenge to policy entrepreneurs seeking to advance transformative policy change [

49]. The central role of consensus-building in EU policy change is to maintain a path-dependent dynamic, where no single actor can prescribe policy and minority interests can be easily mobilised to block reform [

159]. The durable advocacy of RAP, ECF and EEFIG led the EC to propose gradually stronger provisions on EE1. As discussed in section 5.1.1, the EC itself was receptive and acted strategically on ‘external events’ to reframe energy efficiency policy and the role of EE1 to make it appetising for EU politicians. Thus, it was successful in coupling all three streams according to its view. This was not only a “coincidence of propitious conditions” ([

107], p. 281) in the EU politics stream but also a strategically outlined act of advocacy.

6.4. Ethics of Policy Entrepreneurs

6.4.1. A critical View on Policy Entrepreneurism

As described, framing of problems and a policy solution in the case of EE1 was done by experts and high-profile policy advocates in RAP, ECF, EEFIG and the EC. The framing was mainly done with reference to the ‘multiple benefits’ of energy efficiency policy, of which only some correspond to the public opinion on climate change mitigation and low energy bills. Like politicians in the Council and the EP, citizens would hardly understand issues like energy system efficiency, demand-side flexibility and ‘multiple benefits’, which were the main problems addressed by RAP, ECF, EEFIG and the EC.

How a condition is framed as a problem influences how we think about the problem [

51], which enables coupling to certain policies but not to others [

160]. As Copeland and James put it, framing is about “strategic construction of narratives that mobilize political action around a perceived policy problem in order to legitimize a particular solution” ([

155], p. 3). Framing also “involves the manipulation of dimensions to represent solutions to specific problems as gains or losses” ([

86], p. 156).

Weiss [

160] argues that many political decisions like problem and policy framing are taken in non-transparent and complex ways. Many small decisions taken by different persons and organisations taken together form a larger decision. Thus, policy actors without formal decision-making power, like policy entrepreneurs, often take the role of political decision-makers. The policy entrepreneurs in the case of EE1 were not elected politicians but part of the elite in their specific field. Their role in the policy process raises questions about their agency giving the impression of an elitist or technocratic approach, leading to opacity in policymaking, cf. [

161]. If there is lack of transparency, the agency and power of policy entrepreneurs in the policy formulation process conceals the authority that shapes how public problems and policies are framed and defined, which decreases democratic accountability and legitimacy.

There is plenty of research on lobbyism and democracy and a vital debate on regulating lobbyism in the EU, see e.g. [

162,

163]. Despite the similarities of lobbyism and policy entrepreneurship, there is hardly any research or debates on policy entrepreneurship and democracy. Addressing this gap, von Malmborg has proposed a conceptual framework for critical analytical as well as normative research on impacts of policy entrepreneurs’ strategies and agency on democratic governance [

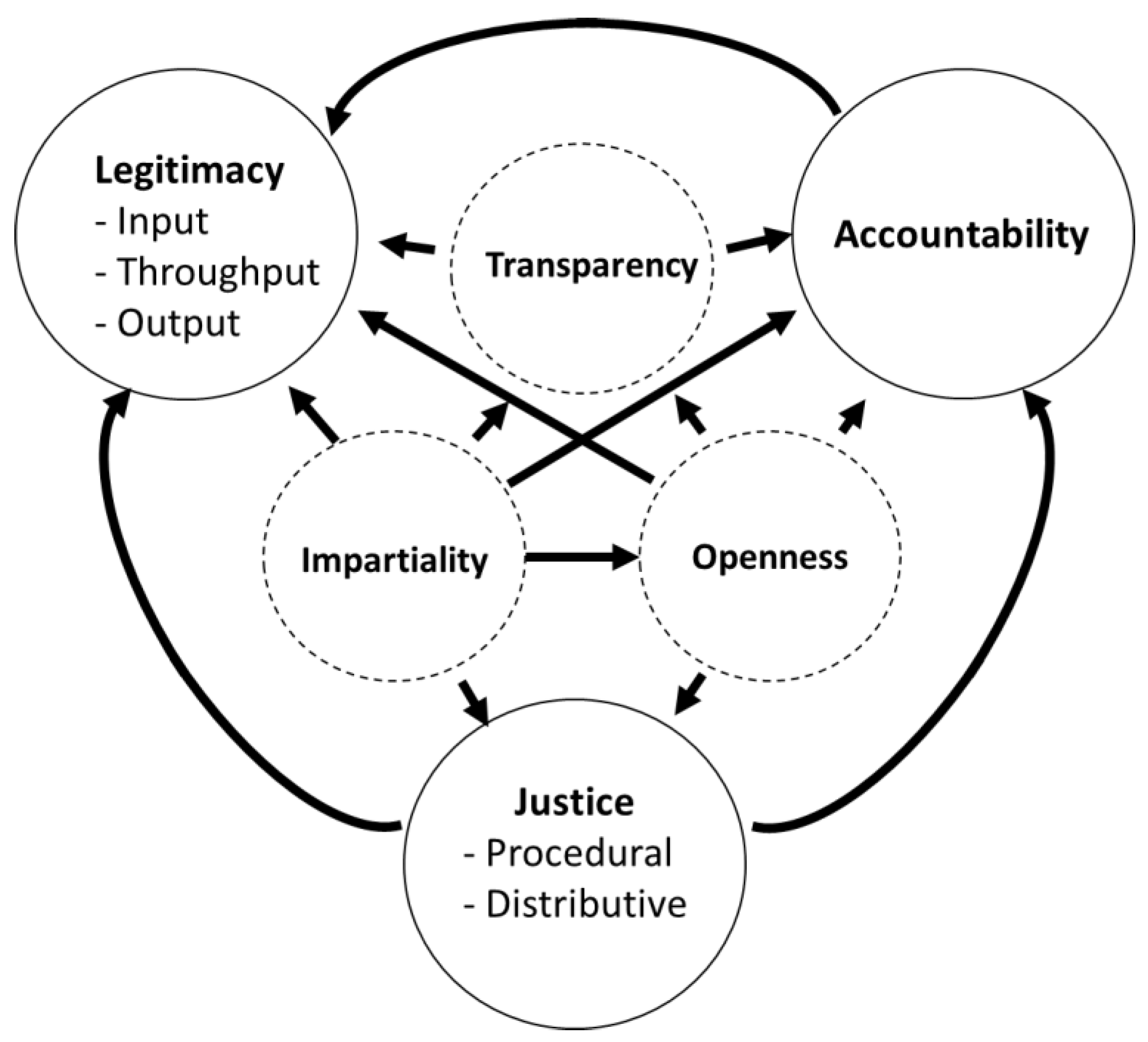

50]. Like lobbyists, policy entrepreneurs should be confronted with the challenge of generating legitimacy, political accountability, and justice in their actions and the implementation of their targeted policy change [

50].

Whether policy entrepreneurism is good or bad in our vision of an ideal democratic regime depends on the conception of the

public interest adopted, cf. [

164]. The conception of public interest shapes the way democracy is conceived and the role of policy entrepreneurism and lobbying within it, cf. [

165]. In his work on regulation of lobbyism, Bitonti [

164] identifies five ideal–typical conceptions of the public interest: formal (technocratic), substantive (populist, autocratic), realist (with no ethics for democracy), aggregative (liberal), and procedural (deliberative). Each conception can be associated with a particular vision of democracy, with different beliefs on human epistemic conditions, anthropology, and economic and institutional ideal designs. These are relevant also for critical and normative research and regulation of policy entrepreneurism [

50].

Out of the five conceptions, two appear strongly against lobbying and policy entrepreneurism (the substantive and the procedural), one moderately against (the formal), one neutral (the realist), and one strongly supportive (the aggregative). Developing a normative framework and eventually regulation of policy entrepreneurs, von Malmborg argues that not only the aggregative (liberal) perception of the public interest should be considered, but also the procedural (deliberative) perception [

50]. Both conceptions are important in discussions on how to regulate policy entrepreneurs in climate governance and democracy since they relate to liberal environmental democracy and deliberative ecological democracy, respectively. Liberal democracy is hegemonic in current democracies, but green parties and the environmental and climate justice movement advocate more deliberative democracy [

166,

167,

168,

169,

170]. In all, von Malmborg [

50] suggests that a normative framework for policy entrepreneurism should focus on six interrelated norms and principles of political–philosophical theories and ethics of liberal and deliberative democracy: legitimacy, accountability, justice, transparency, openness and impartiality (

Figure 5).

6.4.2. EE1 from a Democracy Perspective

Applying this framework to the EE1 case, policy officers, heads of units, director generals and commissioners like Ursula von der Leyen, Frans Timmermans and Kadri Simson in the EC were the ‘official’ architects framing the policy proposals. But can they be held accountable to the public if it turns out that the policies are problematic or flawed? Commissioners can, indirectly, since they must be approved by the Council and the directly elected EP, but public officials in the EC cannot. The same holds true for experts in think-tanks, business associations and NGOs like RAP, ECF and EEFIG who were the real architects of the EE1 proposal.

As for the EC as policy entrepreneur, Dreger [

171] argues that the EC’s problem framing powers are used strategically to technocratise subsequent policy debates, pulling political actors toward those grounds where the EC has a home field advantage. This creativity of the EC to be a successful structural policy entrepreneur, to act as a ‘purposeful opportunist’ [

172] in interpreting rules and procedures in an increasingly complex and contested EU, has also been highlighted by Copeland [

173] and Becker [

72]. While some applauded the EC for pushing MSs to engage with the EGD, especially if they saw it as promoting the public interest, others felt that the EC overstepped its mandate [

72].

The problem framing and policy proposals put forward in the EE1 case were rather untransparent. Both gathered wide support in progressive business communities and environmental organisations, but their anchorage among citizens civil society organisations was unclear. The policy proposal aimed to address ‘multiple benefits’ of energy efficiency, of which climate change mitigation is one. Climate change mitigation is of high priority to EU citizens, but the policy solutions were rather technical and economical. Other benefits like consumer flexibility are even more technical. A key issue of the just transition to climate neutrality is

climate justice, including both procedural justice in the policy process and distributive justice of the output from policy [

50]. It was included to some extent in the recast EED with its provisions on EE1. Alleviation of energy poverty and related social injustice, in essence a social policy issue, has been increasingly used by the EC to frame EU energy efficiency policy [

130]. But this is done in a largely technocratic way, disregarding national government’s views on social policy and the fact that social policy is exclusive MS competence according to TFEU. As policy entrepreneur, the EC disguises poverty alleviation as energy efficiency policy, further contributing to a ‘competence creep’, where the EC acts outside of its powers and slowly expands its competences beyond what is conferred upon it by EU MSs, informally increasing the powers of the EC while reducing the powers and flexibility of MSs [

175,

176,

177].

As for social justice, Crespy and Munta [

178] as well as Dupont et al. ([

179], p. 7) argue that “policies and tools associated with the just transition inside the EU do not lead to a just transition that adequately addresses environmental and social problems”. The setup and design of EU institutions and the increasingly technocratic nature of the EC hamper their implementation of a just transition [

180]. EU institutions have limited ability to overcome the institutional factors that hamper implementation of a just transition, particularly in policy domains where the EU holds limited legal competence according to TFEU, such as social policy [

180]. In the EGD and thus in the EED and EE1, the just transition is primarily seen as a financial transfer policy through the

Just Transition Mechanism and the

Social Climate Fund with targeted financial support to affected regions [

181].

Agency of the EC as well as RAP, ECF and EEFIG can be questioned also from other ethical and democratic perspectives. During negotiations on EE1, the EC issued a recommendation and guidance on how the principle should be applied in different sectors [

115,

116]. This helped MSs understand what EE1 is. As important for MS implementation but also for financing the clean energy transition, EEFIG issued guidance on how EE1 could be implemented by banks and other finance institutions to strengthen energy efficiency [

127]. Such guidance is not binding but has large impact on how MSs implement and how the EC evaluates MS’s implementation of EU legislation, cf. [

182,

183]. Thus, policy entrepreneurship of the EC and EEFIG continued after proposing that EE1 should be made binding. The same holds true for RAP, whose staff published academic papers on how to implement EE1 in different sectors [

104,

105]. But contrary to EU legislation on EE1, these guidance documents were not decided by elected politicians, but by the policy entrepreneurs themselves. The technocratisation of EU energy and climate policy identified and criticised by von Malmborg [

50] is obvious also in the case of EE1.

In addition, RAP staff analysed the EC’s implementation of EE1 in the ‘Clean Energy for All Europeans’ package as academic researchers [

102], though without declaring their role as policy entrepreneurs in an ongoing policy process and that they were the ones who originally proposed EE1 as a policy instrument. The analysis provided them and the EC with arguments to take further steps in the ‘salami tactics’ of implementing EE1 in EU policy.

About organisational linkages and potential conflicts of interest, RAP is a think tank, who in the case of EE1 got finance from ECF. There are no suspicions of unduly finance and dependence on anonymous actors wanting RAP and ECF to pursue their ideas as lobbyists. However, suspicions can be raised about EEFIG being set up by the EC and United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative. Thus, EEFIG works on a mandate from the EC and took part in the development of EE1 from the very beginning. This raises questions why EEFIG acted as an ‘independent’ policy entrepreneur instead of a consultant to the EC. It is a sign of non-transparency and further technocratisation of EU policymaking led by the EC, avoiding accountability and reducing legitimacy to the EU citizens. To increase accountability of policy entrepreneurs, von Malmborg argues that transparency rules in the EU should be expanded from a transparency register of policy actors working with advocacy, to include also information on which policies different actors are aiming to influence and what positions they have [

50,