3. Multialgebras with Involution

For a multiring

A, we denote

the

center of

A. Of course, if

A is commutative,

. The classical theory of central algebras with involution suggests a development of this subject in a very similar way.

Definition 3.1.

Let R be a commutative multiring, A be a (non necessarily commutative) multiring, and a homomorphism of multirings such that , then is a R-multialgebra.

A morphism of R-multialgebras is a morphism of multirings such that .

An involution σ over the R-multialgebra is an (anti)isomorphism of R-multialgebras where is the opposite multiring, is a homomorphism and . Thus, for all , .

A multialgebra with involution is just a multialgebra endowed with an involution where is a multiring with involution. A morphism of multialgebras with involution is a morphism of multialgebras satisfying .

For each commutative multiring with involution is the category of multialgebras with involution, whose objects are multialgebras with involution and morphisms are morphisms of multialgebras with involution.

Whenever the involution

is clear we will omit it and write only

. Note that item 1 implies that

is an initial object in

. Item 2 provides us that every morphism

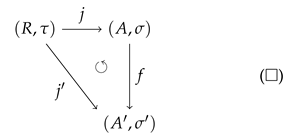

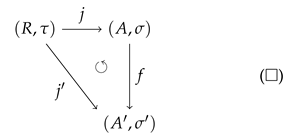

is represented by a commutative triangle.

We call

a

subalgebra of

if the diagram (□) is satisfied by the restricted identity morphism

. An

ideal is a

invariant (

) non-empty subset satisfying

and

for all

. Once

J is

invariant and

is an isomorphism,

, and thence

J is a two-sided ideal. A

proper ideal is an ideal

. We call

J a

prime ideal if

J is an ideal such that

implies

or

for any pair

. The smallest ideal generated by

is

We define the quotient

as usual (see for instance, [

1,

3,

19], or [

20]). We have many standard and effusive constructions that raise various examples in category

.

Let I be a non-empty set. For a given family of multialgebras with involution, the direct product is an multialgebra with involution such that are projection morphisms for each . Indeed, is an involution over , and is a well-defined map satisfying the necessary conditions above.

Matrices over a given commutative multiring are natural constructions. Denote by the set of square matrices of order n with coefficients in and set the sum and product of matrices as follows:

For all matrices

, we define the function

by

and (multi)operations

Since

is an involution and

A is a commutative multiring, it follows that

is also an involution. Finally, let

the diagonal morphism

, which associates each

with a diagonal matrix in

and

is the injective morphism such that

. We will avoid the verification that

is a

multialgebra with involution, but the reader can check

Section 2 of [

4], Theorem 2.3, and Lemma 2.5. However, we give an example to illustrate this construction.

Example 3.2. Consider the kaleidoscope multiring as defined in 2.6 and the matrix transposition. Then, is a multialgebra with involution.

Let

and

matrices over

. Thus,

Therefore, .

Example 3.3.

(Adapted from [21]) Let be a group with 0 and define + the multioperation satisfying

We can define an involution σ over this structure by setting for all and . In fact, σ is additive and it is easy to verify that is a multiring with involution.

4. Marshall’S Quotient of Multialgebras with Involution

Throughout this section, we fix a R-multialgebra with involution . We are interested in Marshall coherent subsets satisfying at least one of the conditions in Theorem 4.11, i.e., normality or convexity. These conditions interact in many ways with the relations below (4.2) compared to the commutative case. First of all, we explore basic properties due to definitions.

Definition 4.1. A subset (without zero divisors) is called a Marshall coherent subset whenever

S is a multiplicative submonoid of

(or, equivalently )

We call S standard if , for all . We said that S is convex if for all in the subset of nonzero divisors of A. If for all , we said that S is convex.

Immediately, convexity implies convexity. One can check Lemma 4.7 and Proposition 4.12 for a reciprocal result. From now on, we fix a Marshall coherent subset .

Definition 4.2. Let and . We define:

iff and ;

iff ;

iff and ;

iff there is such that .

Of course, implies . Further, is an equivalence relation when S is convex. Indeed, this relation concurs with (see Lemma 4.6). We start exploring these relations and related properties of Marshall coherent subsets.

Lemma 4.3. For , as defined above, ∼ is an equivalence relation and satisfies:

For all and all , , , and , .

For all if then .

Proof. Of course ∼ is reflexive (since

S has 1) and symmetric. Now let

and

, with

,

and

,

,

. Then

and

Since S is multiplicative, we have , which implies . Hence, is an equivalence relation. Items 1 and 2 follow straightforward once S is multiplicative and invariant.

□

Lemma 4.4. If S is standard, then is an equivalence relation and satisfies:

For all and all , , , and , .

For all if then .

Proof. Reflexivity and symmetry follow immediately. Note that

, enable us to rewrite the definition of

as follows:

for

.

Consider and which means that there exist such that and . Scaling the previous equation on the right by , and the later, on the left by , we conclude that . Thus, ∼ is transitive, that is, an equivalence relation.

For Item 1, observe that , and for all . Item 2 follows by applying both sides of . □

Lemma 4.5. Suppose that for each . Let , the following statements are equivalent:

such that

such that

such that

That is, if, and only if, . Furthermore, is an equivalence relation.

Proof.

follows immediately from the hypothesis. Thus, for each pair , . For simplicity, denote , for each .

is an equivalence relation: suppose that

and

for

. Observe that

It follows that implies . We already prove that is transitive. Reflexivity and symmetry follow from and the equivalence of the statements 1, 2, and 3. □

We observe that, for a given Marshall’s coherent subset S, convexity is the reflexivity property of by definition. Indeed, there is a suitable relationship between the upward-selected set of relations and Marshall’s coherent convex subsets.

Lemma 4.6. Suppose that S is convex. Let , the following statements are equivalent:

;

;

.

Furthermore, is an equivalence relation. Additionally, for every convex , .

Proof.

There are

such that

Suppose that

. Then, there exist

satisfying

Finally, if

, then

such that

To prove the final assertion, consider , for all . Since and S is convex, for all . Moreover, as long as S is invariant, if, and only if, . It turns out that if, and only if, . Thus, is reflexive and symmetric.

Finally, we prove the transitivity property. Put

and

. Thus, by definition, it follows that

Remember that S is closed under multiplication and convex. As follows, we have already proved the transitivity holds. We conclude that is an equivalence relation. The final assertion follows straightforward. □

The next lemma summarizes and proves many results concerning the properties of Marshall coherent subsets and the above relations.

Lemma 4.7. Let S be a Marshall coherent set in . The succeeding statements hold:

If for all and S is convex, then S is convex;

If S is convex and for all non-zero divisor , then (S is normal);

If and S is convex, then is the set of non-zero divisors, i.e. every non-zero divisor has an inverse in A;

If S is standard, then ;

If S is standard then if, and only if, ;

Proof.

Let a non-zero divisor and . Thus, for some . Commuting s with x, it follows that for a suitable . Hence, convexity and closure of multiplication implies . Therefore, .

Let a non-zero divisor. For any , for some . Therefore , which implies . Since has inverse in S, for a suitable choice of . Hence, . The reverse inclusive follows from symmetry.

-

By definition,

. For the inverse inclusion, note that

is a Marshall coherent set and, let

and

. Thus,

.

The same argument shows that y has the right inverse . Note that . Thus, , implies , for some . Scaling by both right sides of equation, we obtain . Hence .

By hypothesis, . Hence, such that . Direct calculations show it is a both-side unique inverse.

The statement has straightforward proof by scaling and dividing.

□

For each

, denote an element in

(whenever it exists) by

. We have well-defined rules

Observe the involutory structure can be defined in the very same way for superrings.

Definition 4.8. A superring with involution is a superring satisfying (mutatis mutandis) the axioms for multialgebras with involution.

Theorem 4.9. The structure is a superring with involution . If S is standard, then is a superring with involution .

Proof. Just proceed with a very similar argument to the one used in Theorem 5.2. □

We define existing quotients for general Marshall coherent subsets. In the sequence, we deal in particular with normality and convexity.

Definition 4.10. We define the superring as the Marshall’s Quotient of A by S, and denote it by .

Whenever ∼ is chosen, we might indicate the Marshall subset S by adding it to the index, i.e., writing .

Theorem 4.11. Let be a Marshall coherent subset of a multiring A satisfying one of the additional conditions below

(Normal) , for all .

(Convex) For all , a nonzero divisor in A, .

If is a multialgebra with involution, the set is a multiplicative submonoid of . Moreover, defines a -multialgebra structure over , and is an involution over the -multialgebra . In both cases, is a multiring.

Proof. Once is a homomorphism, if in R, then . It is easy to check that is a multiplicative submonoid of R and, due to S being Marshall coherent, for all . Thus, whenever . We conclude that is Marshall coherent,i.e. is a multiring with involution .

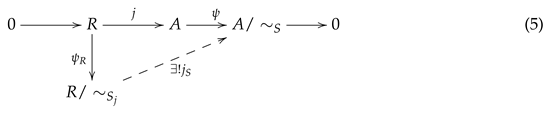

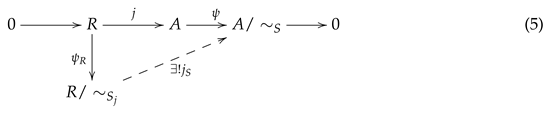

Now, consider the following diagram:

(1) If , then can be read as if, and only if, for some . Previous constructions (see 4.9) and demonstrations show that is a superring. Let and be elements in , thus and for some . Scaling equations and comparing gives us . Which means that . Therefore, and, is a multiring.

By the universal property of the quotient , is unique. Since all arrows are homomorphisms, is multialgebra. Furthermore, S is invariant, which means . Consequently, the induced antihomomorphism such that is well-defined and an involution over .

(2) Let . In this case, 4.6 and the preceding case show that is a multiring. The proof is the same as before since 4.9 still holds.

□

The above theorem provides us with two kinds of quotients lying in the class of multrings. One can wonder if the quotient can give some information about the Marshall coherent subset.

Proposition 4.12. Let be a multiring, S be a Marshall coherent subset, such that and . Then, is convex if, and only if, is convex.

Proof. Sketch of the proof: Note that is Marshall coherent. The converse is immediate. To prove the reciprocal statement, use (since the quotient is a multiring, · is actually a usual operation) for all . □

According to the above results, some immediate examples follow below.

Example 4.13. For a given , a -multialgebra with involution, the next sets are Marshall coherent:

- a)

The set of all non-zero divisors ;

- b)

The set of all invertible elements ;

- c)

The set of all symmetric elements (in ) ;

- d)

If for all , then is Marshall coherent and convex.

In the next section, we provide more examples minutely. For now, we treat about another kind of operations in the quotient. For , let if, and only if, there exist such that . This can be replaced in terms of the equivalent statements in 4.5 or 4.6, whether or S is convex, respectively. Hence is an equivalence relation. Moreover, each is invariant under S action, for all .

In define , and .

Theorem 4.14. Suppose that . Then,

is a (non-commutative) multiring.

If A is a hyperring, then is a hyperring. In particular, if A is a ring, then is a hyperring.

It holds the universal property of Marshall’s quotient for homomorphisms and anti-homomorphisms (= homomorphism ) such that .

Proof. To demonstrate 1, we note that , and − are well-defined as multigroup operations, and is the null element because A is a multiring.

Suppose that . Thus, there exists satisfying in A. Therefore, (in A). Similarly, . Consequently, and .

Let . By definition, exists such that for some . However, it implies . The reciprocal is obvious.

If

and

, then

and

for

. Afterward,

The last implication means . Once A is a multiring, if, and only if, follows.

We have already proved that

is a multigroup. Note that exists

such that

for all

. Thus,

is a monoid. Moreover,

. Finally, let

and

. By definition, exists

such that

. Since

A is a multiring,

. Using the ’normality property’ of

S, we rewrite it as follows:

Similarly, holds. It follows that is a multiring.

For the second assertion, suppose that

A is a hyperring. Let

. Thus,

Therefore, . By symmetry, also follows.

To demonstrate the third statement, consider a homomorphism such that . Let and . Thus, . Define the homomorphism with . Hence, is well-defined, and , with the canonical projection. It is immediate that another homomorphism satisfying must coincide with . □

Remark 4.15. The Theorem 4.14 is valid if S is convex. Since both conditions normality and convexity imply , we are capable of proving the distributive laws hold and the entire rest of the proof follows as above.

The next theorem distinguishes Marshall coherent subsets that lie in the center from an ordinary one.

Theorem 4.16. Let A be a multialgebra with involution and be a Marshall coherent subset such that (thus, in particular , for all ). Then is a (non commutative) hyperring with induced involution.

Proof. From previous considerations and 4.9, we prove that is a multiring instead of a superring, and the hyperring property still holds.

In fact, if then for some , which means and . Then , proving that is a multiring.

Now, let

. Then

for some

,

, providing equations

for some

. Then

which imply

. The same reasoning provides

. □