Submitted:

02 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Textual Algorithm

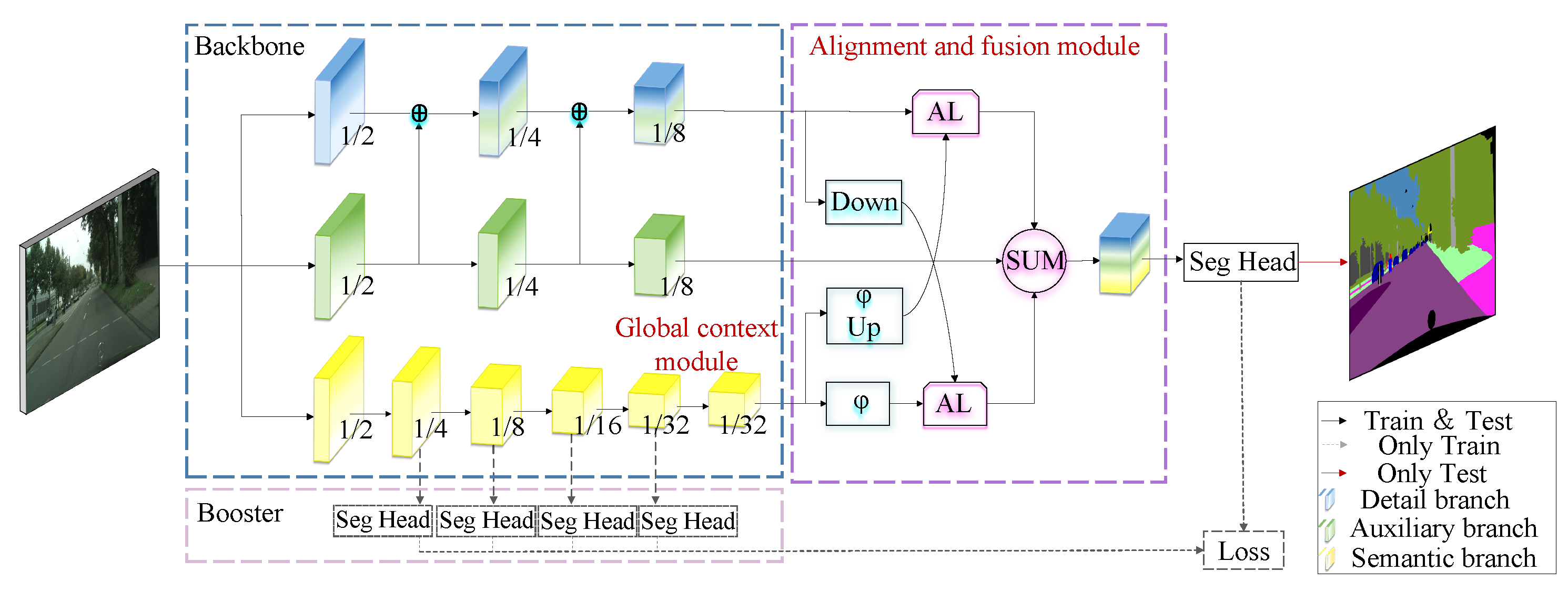

2.1. Overall Structure

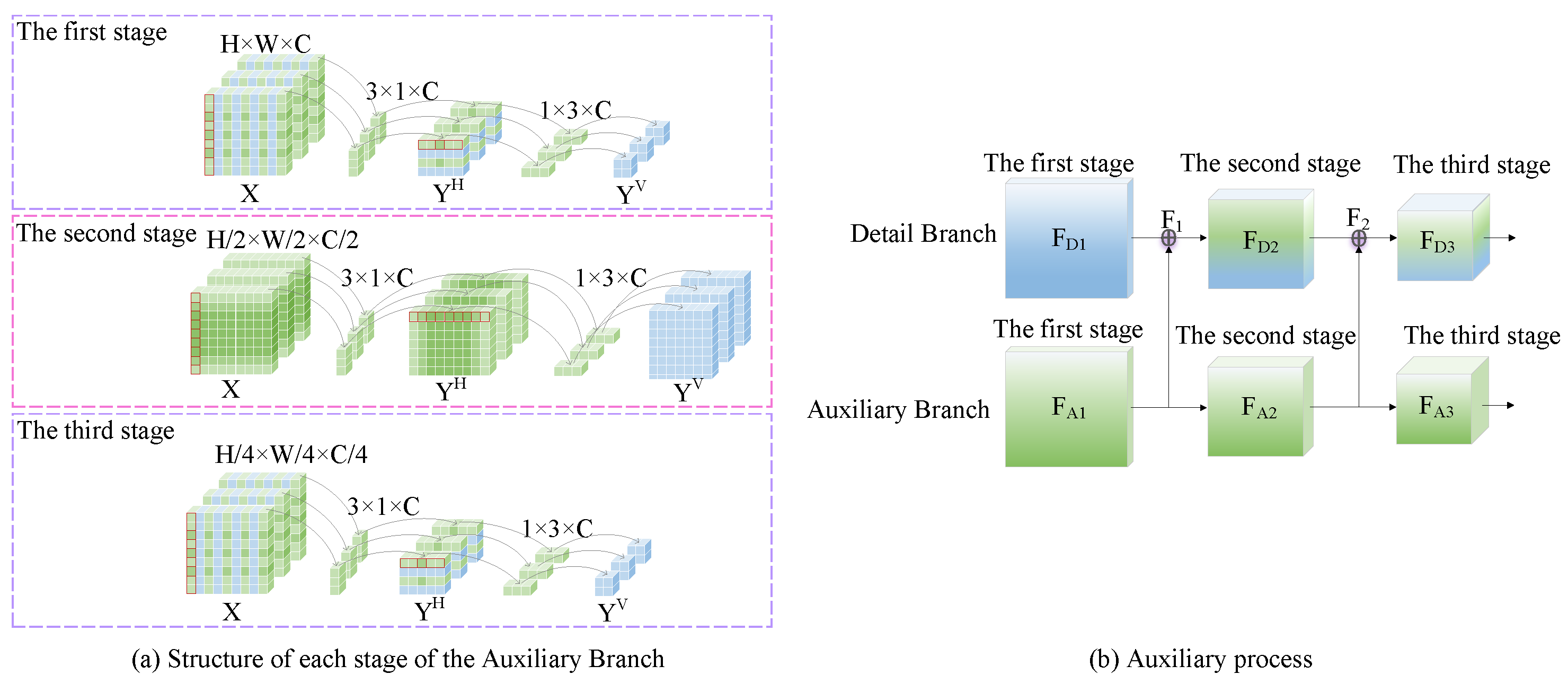

2.2. Auxiliary Branch

2.3. Align and Fuse Modules

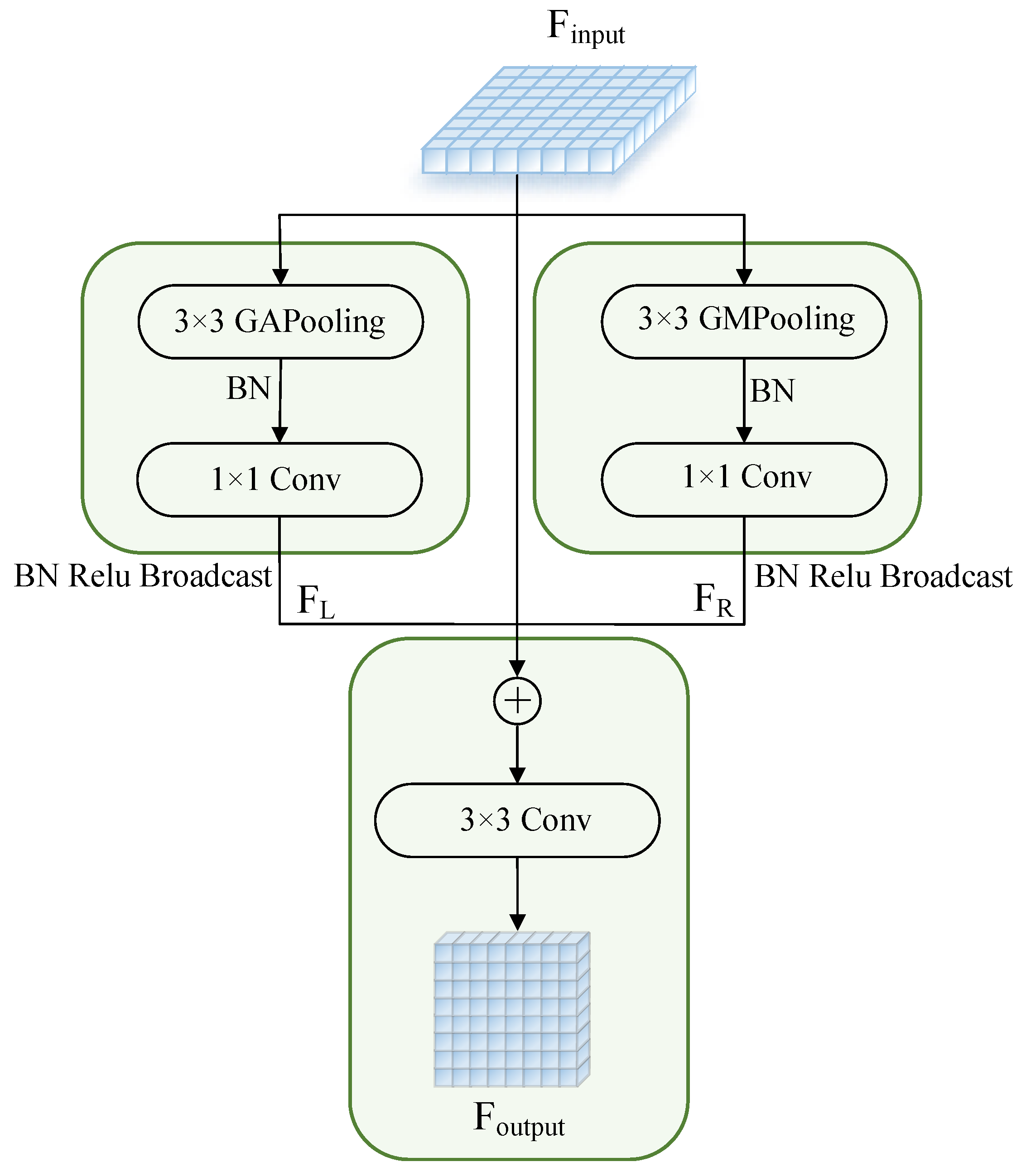

2.4. Global Context Module

3. Experiment and Result Analysis

3.1. Data Set Introduction

3.1.1. Cityscapes Data Set

3.1.2. CamVid Data Set

3.2. Evaluation Index

3.3. Training Strategy

3.3.1. Experimental Parameter

3.3.2. Data Enhancement

3.3.3. Training Optimization Strategy

3.4. Ablation Experiment

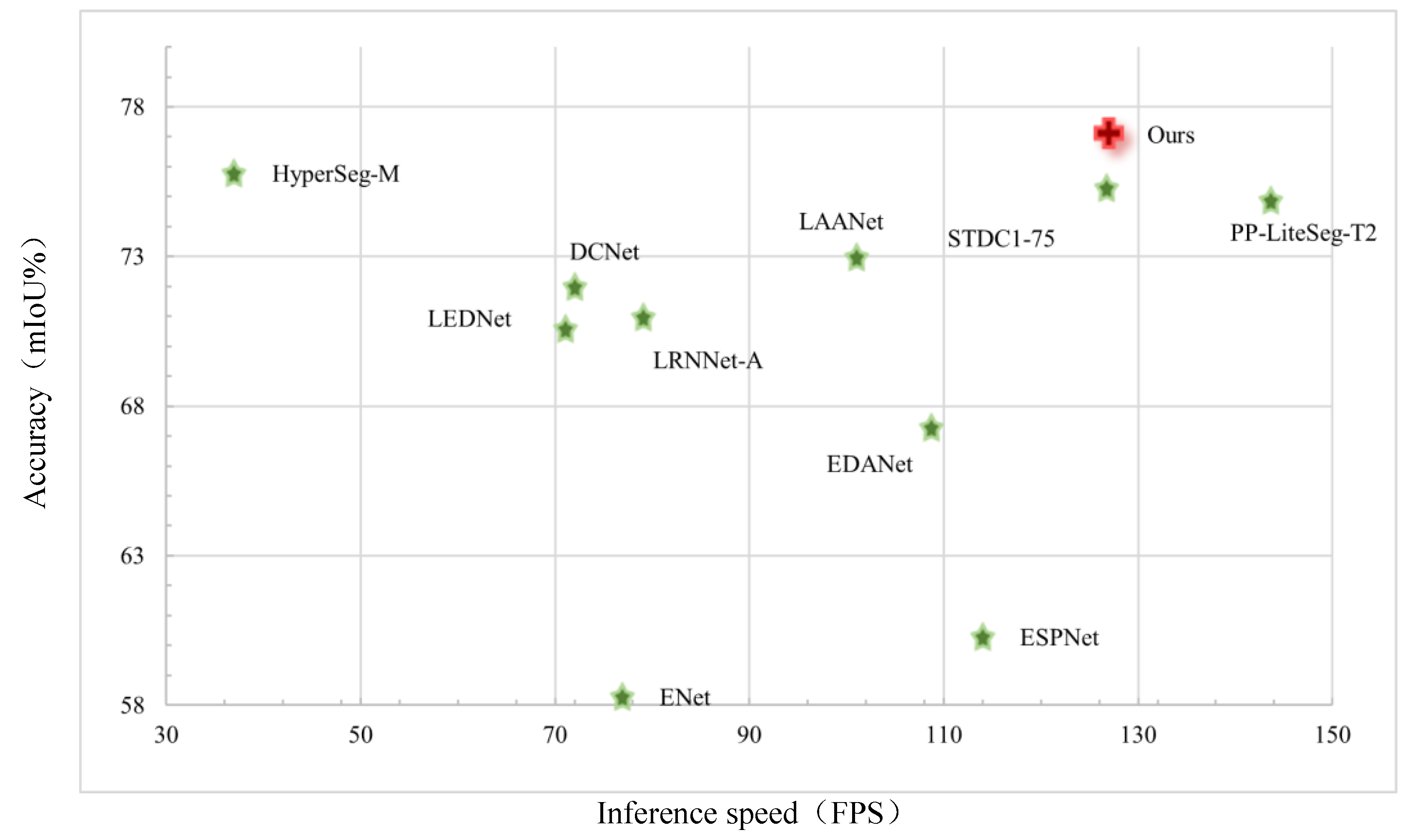

3.5. Contrast Experiment

| SegNet [27] | 91.8 | 62.8 | 42.8 | 89.3 | 38.1 | 43.1 | 44.1 | 35.8 | 51.9 | 55.6 | |

| ENet [28] | 90.6 | 65.5 | 38.4 | 90.6 | 36.9 | 50.5 | 48. 1 | 38.8 | 55.4 | 58.3 | |

| ESPNet [32] | 92.5 | 68.5 | 45.9 | 89.9 | 40.0 | 47.7 | 40.7 | 36.4 | 54.9 | 60.3 | |

| NDNet [49] | 90.2 | 62.6 | 41.6 | 88.5 | 57.8 | 63.7 | 35.1 | 31.9 | 59.4 | 60.6 | |

| LASNet [50] | 91.8 | 70.8 | 51.3 | 91.1 | 77.3 | 81.7 | 69.2 | 48.0 | 65.8 | 70.9 | |

| FSFNet [51] | 94.2 | 77.8 | 57.8 | 92.8 | 47.3 | 64.4 | 59.4 | 53.1 | 66.2 | 65.3 | |

| ERFNet [29] | 94.2 | 78.5 | 59.8 | 93.4 | 52.3 | 60.8 | 53.7 | 49.9 | 64.2 | 69.7 | |

| LEDNet [52] | 94.9 | 76.2 | 53.7 | 90.9 | 64.4 | 64.0 | 52.7 | 44.4 | 71.6 | 70.6 | |

| BisNetV2 [36] | 94.9 | 83.6 | 65.4 | 94.9 | 60.5 | 68.7 | 56.8 | 61.5 | 51.9 | 72.6 | |

| Ours | 94.8 | 81.0 | 58.5 | 94.3 | 80.6 | 83.8 | 78.0 | 57.2 | 76.5 | 77.1 |

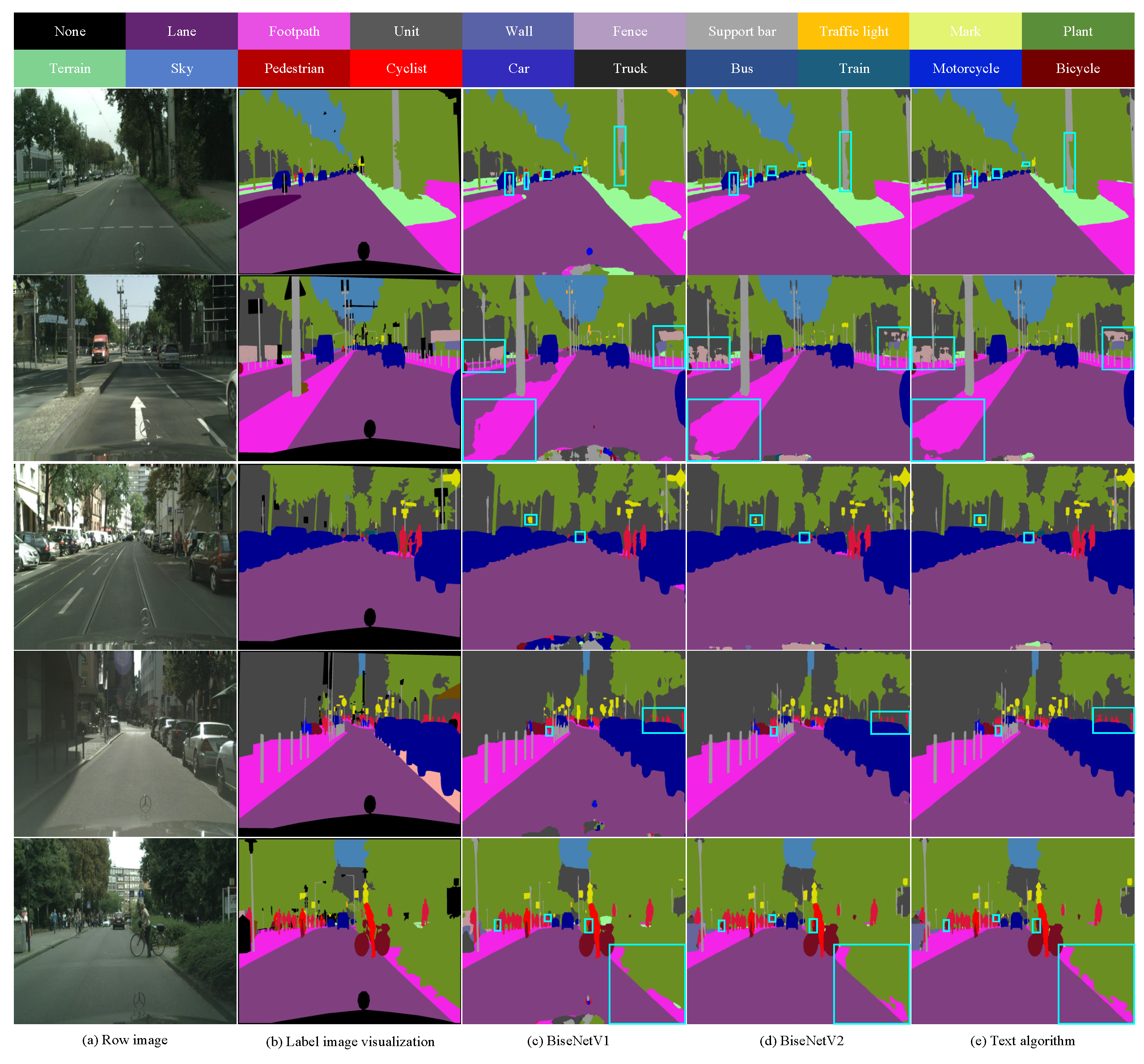

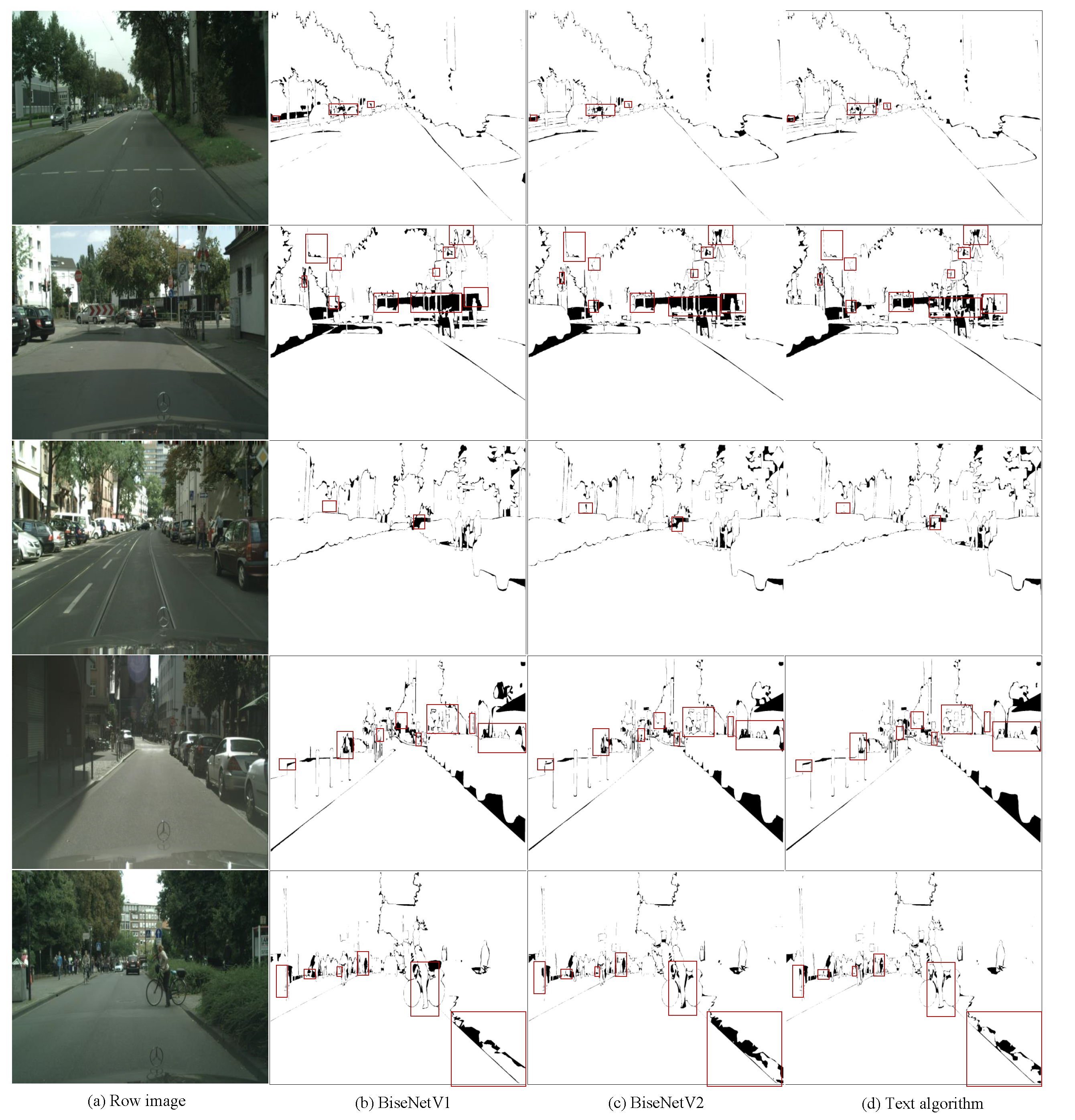

3.6. Visual Result

4. Conclusion

References

- Huang, M.Y. A brief introduction on autonomous driving technology. Science & Technology Information 2017, 15, 1–2, in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- XU PJ, C.Y.; others. Research on event-driven lane recognition algorithms. Acta Electronica Sinica 2021, 49, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.N.; Wang, T.F.; Tian, Y.Z.; others. 3D point cloud segmentation based on improved local surface convexity algorithm. Chinese Optics 2017, 10, 348–354, in Chinese. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Zhou, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, F.; He, X. ADPNet: Attention based dual path network for lane detection. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2022, 87, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zheng, Q.; Liang, C. Overview of Image Segmentation Methods. J Wuhan Univ (Nat Sci Ed) 2020, 66, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haocheng, S.; li, L.; Fanchang, L. Lie group fuzzy C-means clustering algorithm for image segmentation. Journal of Software 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wang, P.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, D.; Geng, Q.; Yang, R. The apolloscape open dataset for autonomous driving and its application. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2019, 42, 2702–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, X.J.; Li, J.F.; Liu, Y.L. A 3D image segmentation algorithm based on maximum inter-class variance. Acta Electronica Sinica 2003, 23, 1281–1285, in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, M.L. A technology of image segmentation based on cloud theory. PhD thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, 2010. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.L.; Lei, B. Reciprocal rough entropy image thresholding algorithm. Journal of Electronics & Information Technology 2020, 42, 214–221, in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18. Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets and fully connected crfs. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1412.7062. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1706.05587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV); 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongyu, W.; Xianyang, N.; Zhendong, S. Semantic segmentation of automatic driving scenarios using convolution-al neural networks. Optics and Precision Engineering 2019, 27, 2429–2438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhaohui, L.; Gezi, K. Aerial wire recognition algorithm in infrared aerial image based on improved Deeplabv3+. Infrared and Laser Engineering 2022, 51, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, B.; Deng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Mu, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, X. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Visual Recognition. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinghong, H.; Zhuoyun, N.; Qingguo, W.; Shuai, L.; Laicheng, Y.; Dongsheng, G. Image real-time semantic segmentation based on block adaptive feature fusion. Acta Automatic Sinica 2021, 47, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.; Chengze, L.; Shijie, L.; Le, Z.; Yuhuan, W.; Mingming, C. Light-weight semantic segmentation based on efficient multi-scale feature extraction. Chinese Journal of Computers 2022, 45, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, F. Real-time semantic segmentation of lightweight convolutional attention feature fusion networks. Journal of Computer-Aided Design & Computer Graphics 2023, 35, 935–943. [Google Scholar]

- Feiwei, Q.; Xile, S.; Yong, P.; Yanli, S.; Wenqiang, Y.; Zhongping, J.; Jing, B. Real-time semantic segmentation of scene in unmanned driving. Journal of Computer-Aided Design & Computer Graphics 2021, 33, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Zhiwen, Z.; Tiange, L.; Pengju, N. Real-time street view semantic segmentation algorithm based on reality data enhancement and dual path fusion network. Acta Electronical Sinica 2022, 50, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis & Machine Intelligence 2017, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Kim, S.; Culurciello, E. ENet: A Deep Neural Network Architecture for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Romera, E.; Alvarez, J.M.; Bergasa, L.M.; Arroyo, R. ERFNet: Efficient Residual Factorized ConvNet for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2017, PP, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qi, X.; Shen, X.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. ICNet for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation on High-Resolution Images, 2017.

- Hu, P.; Perazzi, F.; Heilbron, F.C.; Wang, O.; Lin, Z.; Saenko, K.; Sclaroff, S. Real-Time Semantic Segmentation With Fast Attention. International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2021.

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M.; Caspi, A.; Shapiro, L.; Hajishirzi, H. ESPNet: Efficient Spatial Pyramid of Dilated Convolutions for Semantic Segmentation; Springer: Cham, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, X.; Ren, H.; Hu, Y.; Bai, S. SwiftNet: Real-time Video Object Segmentation. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, T.; Fan, J.; Lu, Y.; Chi, Q. EADNet: Efficient Asymmetric Dilated Network for Semantic Segmentation. 2021.

- Yu, C.; Wang, J.; Peng, C.; Gao, C.; Yu, G.; Sang, N. BiSeNet: Bilateral Segmentation Network for Real-time Semantic Segmentation; Springer: Cham, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Gao, C.; Wang, J.; Yu, G.; Shen, C.; Sang, N. BiSeNet V2: Bilateral Network with Guided Aggregation for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation; Springer US, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Y. Adaptive pyramid context network for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2019; pp. 7519–7528. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; You, A.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yang, M.; Yang, K.; Tan, S.; Tong, Y. Semantic flow for fast and accurate scene parsing. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 775–793.

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 3213–3223.

- Brostow, G.J.; Shotton, J.; Fauqueur, J.; Cipolla, R. Segmentation and recognition using structure from motion point clouds. Computer Vision–ECCV 2008: 10th European Conference on Computer Vision, Marseille, France, October 12-18, 2008, Proceedings, Part I 10. Springer, 2008, pp. 44–57.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Guo, R.; Xu, X. LASNet: A light-weight asymmetric spatial feature network for real-time semantic segmentation. Electronics 2022, 11, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Yanan, S.; Pengcheng, X. Stripe Pooling Attention for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. Journal of Computer-Aided Design & Computer Graphics 2023, 35, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xiong, P.; Fan, H.; Sun, J. Dfanet: Deep feature aggregation for real-time semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2019; pp. 9522–9531. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Lai, S.; Huang, J.; Wei, X.; Chai, Z.; Luo, J.; Wei, X. Rethinking bisenet for real-time semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2021; pp. 9716–9725. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hong, R.; Cheng, J.; Wang, M. Real-time semantic segmentation via spatial-detail guided context propagation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuegang, H.; Yu, G.; Liyuan, J. High-speed semantic segmentation of dual-path feature fusion codec structures. Journal of Computer-Aided Design & Computer Graphics 2022, 34, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, H.; Fu, Q.; Sun, W.; Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Mao, Z.H. NDNet: Narrow while deep network for real-time semantic segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2020, 22, 5508–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, B.; Chi, S. Accelerator-aware fast spatial feature network for real-time semantic segmentation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 226524–226537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Xiong, J.; Gao, G.; Wu, X.; Latecki, L.J. Lednet: A lightweight encoder-decoder network for real-time semantic segmentation. 2019 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP); IEEE, 2019; pp. 1860–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, R.P.; Liwicki, S.; Cipolla, R. Fast-scnn: Fast semantic segmentation network. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1902.04502. [Google Scholar]

| model | mIoU% | Running speed (Frames*s-1) | 10-6×Parameter quantity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 72.60 | 156.00 | - | |

| +Auxiliary Branch | 74.30 | 139.00 | 3.74 | |

| +AAFM | 74.40 | 137.00 | 4.25 | |

| +CGM | 73.30 | 150.00 | 3.37 | |

| +Auxiliary Branch+AAFM+CGM | 77.10 | 127.00 | 4.65 | |

| Network type | Network name | Pre-training | mIoU% | Running speed (Frames*s-1) | resolution | 10-6×Parameter quantity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large scale | SegNet [27] | Y | 57.0 | 17 | 640×360 | 29.5 | |

| PSPNet [14] | Y | 81.2 | <1 | 713×713 | 65.7 | ||

| DeepLabV2 [16] | Y | 70.4 | <1 | 512×1024 | 44 | ||

| Light weight | Fast-SCNN [43] | N | 68 | 123.5 | 1024×2048 | 0.4 | |

| ESPNet [32] | Y | 60.3 | 112.9 | 512×1024 | 0.4 | ||

| SPANet [44] | Y | 70.6 | 92.0 | 1024×1024 | - | ||

| DFANet [45] | Y | 71.3 | 100 | 1024×2048 | 7.8 | ||

| STDC-Seg50 [46] | Y | 73.4 | 156.6 | 512×1024 | 12.3 | ||

| SGCPNet [47] | Y | 70.9 | 103.7 | 1024×2048 | 0.61 | ||

| DPFFNet [48] | N | 67.7 | 111.0 | 1024×2048 | 2.59 | ||

| SwiftNet [33] | Y | 75.4 | 39.9 | 1024×2048 | 11.8 | ||

| LCANet [24] | Y | 72.7 | 86.0 | 1024×2048 | 0.68 | ||

| BiseNetV1 [35] | Y | 68.4 | 105.8 | 786×1536 | 5.8 | ||

| BiseNetV2 [36] | N | 72.6 | 156.0 | 512×1024 | - | ||

| Ours | Y | 77.1 | 127.0 | 512×1024 | 4.65 | ||

| Network name | lane | footpath | unit | wall | Fence | Support bar | Traffic light | mark | plant | topography | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SegNet [27] | 96.4 | 73.2 | 84.0 | 28.4 | 29.0 | 35.7 | 39.8 | 45.1 | 87.0 | 63.8 | |

| ENet [28] | 96.3 | 74.3 | 75.0 | 32.2 | 33.2 | 43.4 | 34.1 | 44.0 | 88.6 | 61.4 | |

| ESPNet [32] | 95.7 | 73.3 | 86.6 | 32.8 | 36.4 | 47.0 | 46.9 | 55.4 | 89.8 | 66.0 | |

| NDNet [49] | 96.6 | 75.2 | 87.2 | 44.2 | 46.1 | 29.6 | 40.4 | 53.3 | 87.4 | 57.9 | |

| LASNet [50] | 97.1 | 80.3 | 89.1 | 64.5 | 58.8 | 48.6 | 48.5 | 62.6 | 89.9 | 62.0 | |

| FSFNet [51] | 97.7 | 81.1 | 90.2 | 41.7 | 47.0 | 47.0 | 61.1 | 65.3 | 91.8 | 69.3 | |

| ERFNet [29] | 97.9 | 82.1 | 90.7 | 45.2 | 50.4 | 59.0 | 62.6 | 68.4 | 91.9 | 69.4 | |

| LEDNet [52] | 98.1 | 79.5 | 91.6 | 47.7 | 49.9 | 62.8 | 61.3 | 72.8 | 92.6 | 61.2 | |

| BisNetV2 [36] | 98.2 | 82.9 | 91.7 | 44.5 | 51.1 | 63.5 | 71.3 | 75.0 | 92.9 | 71.1 | |

| Ours | 97.9 | 83.8 | 92.3 | 63.7 | 63.8 | 64.9 | 63.1 | 77.5 | 92.4 | 63.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).