1. Introduction

Semantic segmentation for indoor scenario is a dense prediction task that aims to assign a category label to each pixel in an image. It is applied in medical image analysis, industrial robots, intelligent driving and other fields[

1]. In order to improve the accuracy of semantic segmentation, many researchers use convolutional neural Network (CNN) [

2] to extract image features. The powerful feature extraction ability of CNN and recombination of multilevel information have led to notable advances in segmentation. For example, He et al. [

3] pro-posed a semantic segmentation model based on pyramid scene parsing, which is characterized by combining kernels of different sizes to create a spatial pyramid pooling network. PointFlow [

4] is proposed by Huang et al, which adaptively uses the high-semantic low-resolution feature map to enhance the low-semantic high-resolution feature map to obtain the high-semantic high-resolution feature map. Although CNN shows strong performance in information representation, RGB images are planarization of 3D space and lose depth information. Only using RGB images as a single data source, deep learning networks cannot learn enough information in com-plex and diverse scenes.

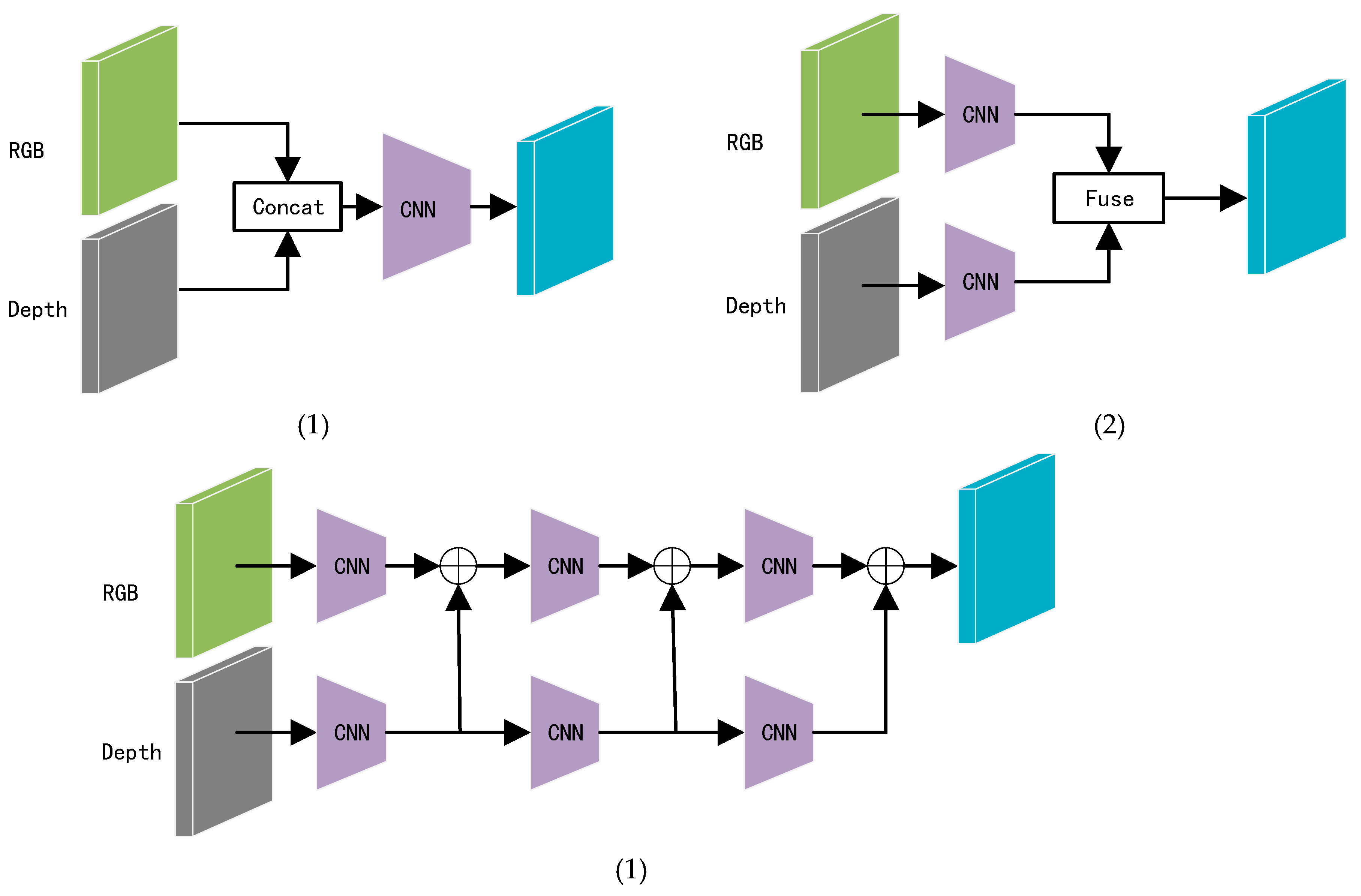

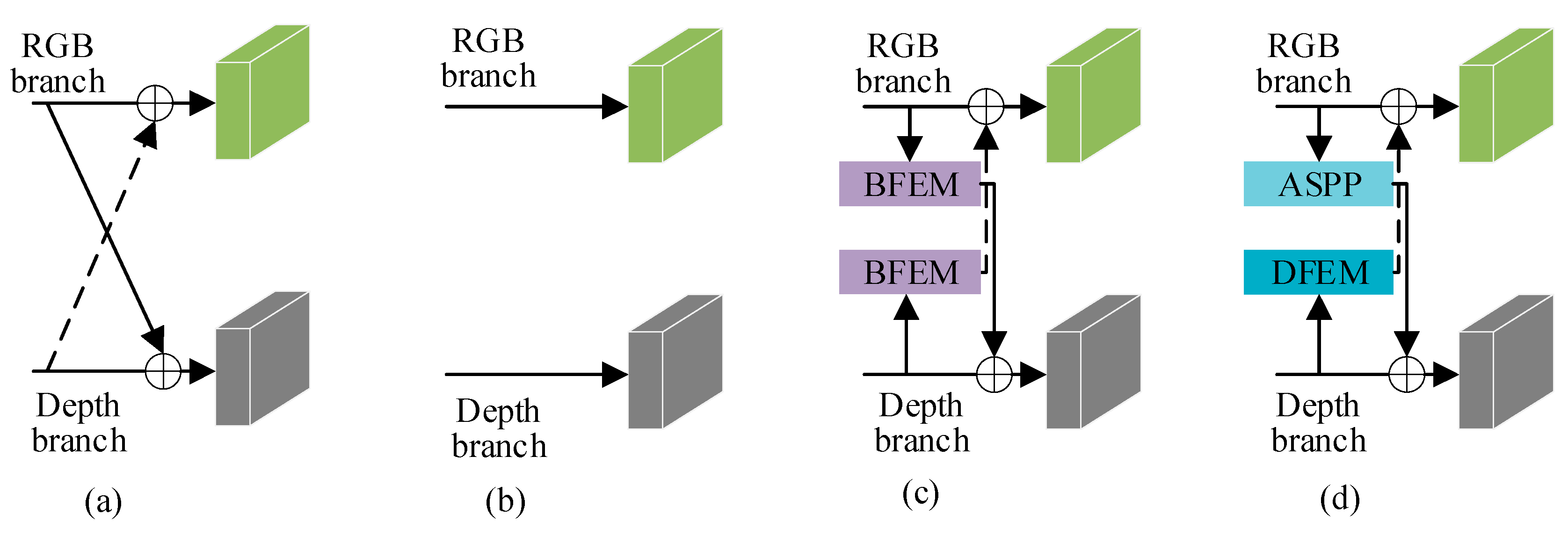

RGB images may generate noise due to similar texture characteristics among different objects. However, depth maps can provide relative distance information of objects, unaffected by the color and texture of similar objects, and can also distinguish the relative positions of occluded objects. The information provided by depth maps can compensate for the shortcomings of indoor RGB images, such as occlusions and similar textures. As shown in

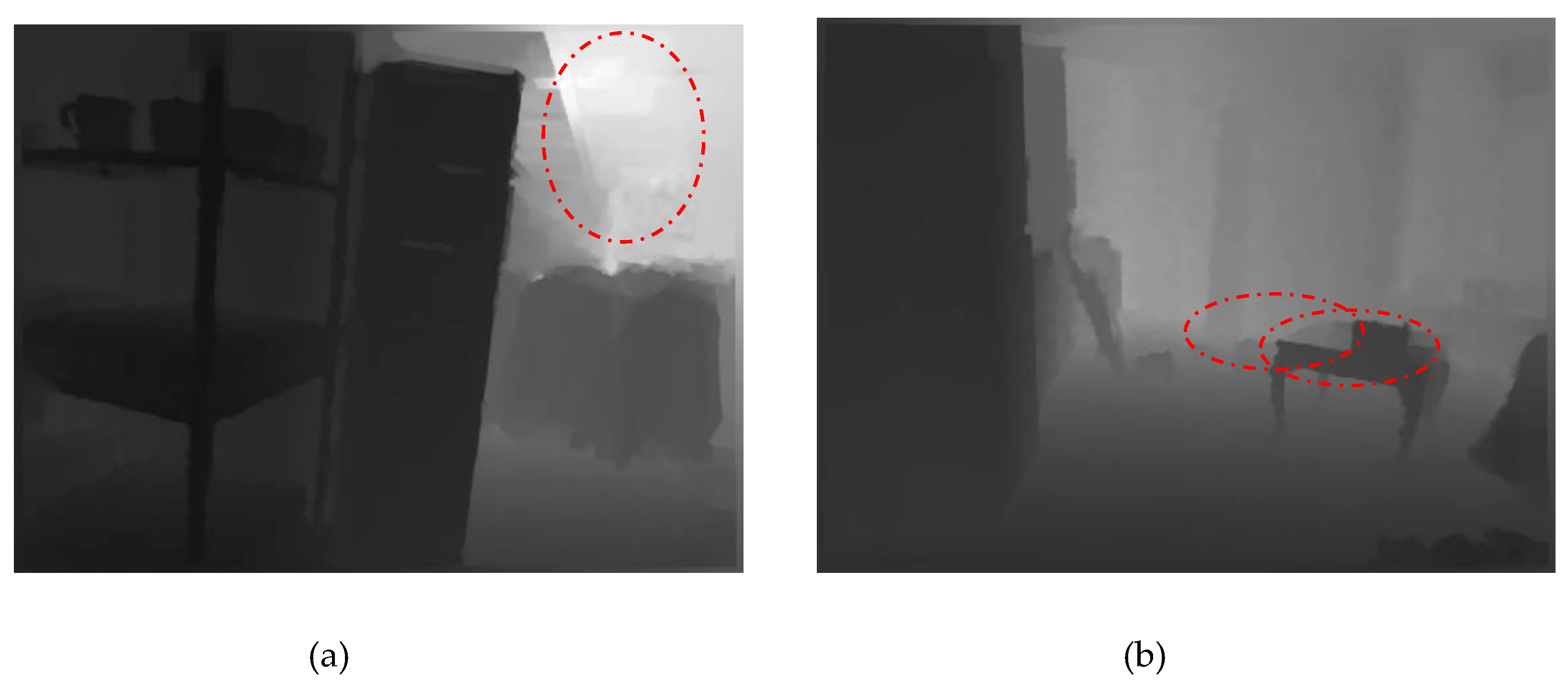

Figure 1, depending on the timing of the fusion of RGB and depth map features within the network, the fusion methods can be categorized into three types: 1) Early fusion: RGB and depth maps are concatenated first and then passed through convolutional layers to generate feature maps; 2) Late fusion: The network adopts a dual-branch structure, where these two branches independently extract corresponding RGB and depth features, and finally, the extracted features are fused; 3) Multi-level fusion: This method gradually fuses the features of RGB and depth maps layer by layer, enhancing the complementarity of the two through dynamic weight configuration. Due to the significant semantic gap between RGB and depth maps, the semantic segmentation results using early fusion are not ideal. Although the methods in (b)-(c) have made some progress, there is still room for exploration of the correlation and interaction between RGB and depth data. In addition, depth maps may also contain noise. As shown in

Figure 2(a), due to the limitations of camera hardware, when objects are far from the camera, their boundaries are not clear, which can easily introduce noise during boundary information extraction. As shown in

Figure 2(b), different objects at the same distance from the camera may be segmented as a single object.

Many studies [

5,

6] employ similar methods to extract features from two modalities of data (RGB and depth maps) or simply use depth maps as a supplement to RGB images, ignoring the differences and complementarity of these two modalities. RGB images in indoor environments contain rich textures and boundary details. However, challenges such as occlusions and similar textures between different objects still exist. While depth maps pro-vide information about the relative positions of objects, they offer limited effective boundary information. Considering the modal differences between RGB and depth maps, we have designed two different feature extraction modules: the RGB Feature Extraction Module (BFEM) and the Depth Feature Extraction Module (DFEM). BFEM adds asymmetric convolutions in ASPP [

7] to capture features in horizontal and vertical spatial directions and introduces Criss-Cross Attention to obtain contextual information in global dependencies; DFEM extracts significant unimodal features of depth maps from both channel and spatial dimensions. However, there is an obvious semantic gap between the data of these two modalities. Therefore, an Adaptive Feature Complementary Fusion Module (AFFCM) is proposed to automatically align the features of these two modalities.

As convolutional neural networks deepen, there is a possibility of losing information pertaining to small-scale objects. Multilevel contextual information plays a significant role in the segmentation of small-scale objects. The rich details of object boundaries are encompassed within low-level contextual information, while the relationships between different objects are encompassed within high-level contextual information. Researchers have conduct-ed extensive studies to fully capture the characteristics of multi-scale objects present in images. Many classical network models have been proposed for this purpose, such as the image pyramid [

8], feature pyramid [

9], and spatial pyramid pooling [

3]. Detailed information is crucial for capturing multi-scale object details. Low-level features provide essential details such as textures, spatial relationships, and other key information for multi-scale objects.

The feature map output by the first layer of the encoder preserves detailed information but lacks semantic content. Conversely, the feature map output by the last layer of the decoder contains rich semantic information, but it loses detailed information as the network deepens. In previous studies, a common approach was to perform an additive operation on these two feature maps. While this method reduces computational complexity, it often leads to a decrease in semantic segmentation accuracy. In this paper, we design a Feature Refinement Head (FRH) that refines feature maps from both spatial and channel perspectives. Additionally, we introduce a novel Skip Connection Module (SCM) that fuses multi-scale feature maps to enhance the network's robustness towards multi-scale objects.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

We introduce a novel dual-branch RGB-D semantic segmentation network named CFANet. Tailored feature extraction modules are designed based on the distinct characteristics of RGB and depth maps, subsequently enhancing segmentation accuracy through adaptive cross-modal feature fusion.

- (2)

BFEM introduces asymmetric convolution on the basis of dilated convolution to alleviate the gridding effect of dilated convolution. Additionally, it achieves rich contextual learning through dense connections and Criss-Cross Attention. DFEM extracts significant unimodal features from both the channel and spatial dimensions of depth maps.

- (3)

Guide the RGB branch and depth map branch to interact rather than simply treating the depth map as a complement to the RGB image.

- (4)

AFFCM employs a multi-head self-attention mechanism to address the semantic discrepancies between RGB and depth map features, resulting in their adaptive alignment. This process effectively enhances the complementary information exchange between the two modalities and mitigates redundancy.

- (5)

We adopt different strategies for feature maps of different scales. Multi-scale feature maps are fused through SCM; considering that the first layer contains the richest detailed information and the last layer contains the richest semantic information, we designed FRH to fuse both.

2. Related Works

2.1. RGB-D Semantic Segmentation

Due to the intricate occlusion relationships, diverse object sizes, and high similarity in texture and color characteristics within indoor scenes, information provided by a single RGB image is insufficient for indoor semantic segmentation tasks. With the advancement of depth cameras, researchers have incorporated depth maps as an additional data source for image semantic segmentation. For instance, Kazerouni et al. [

10] proposed an RGB-D image semantic segmentation network based on the fusion of multimodal image features. This method employs a direct summation approach to progressively merge RGB image features with depth images at different hierarchical levels. Zheng et al. [

11] introduced a depth-similar convolution, replacing regular convolutional layers and average pooling layers in the encoder. Zhou et al. [

12] presented FRNet, a method for indoor scene understanding, which extracts features hierarchically in a top-down manner. However, the aforementioned methods simply fuse depth maps and RGB images through a straightforward summation process.

To enhance the fusion between RGB images and depth maps, Zhou et al. [

13] applied a self-attention module during the decoding stage to adaptively merge depth map features and RGB features. Cao et al. [

14] introduced a convolution named ShapeConv, which can learn an adaptive balance between shape information and the preservation of base information, allowing the network to focus more on shape information when necessary, thereby benefiting the RGB-D semantic segmentation task. Zhang et al. [

15] proposed a non-local aggregation method for RGB-D semantic segmentation, integrating features from both spatial and channel perspectives to achieve multi-level information fusion between RGB images and depth maps. Zhou et al. [

16] introduced a novel feature enhancement method aimed at improving the features extracted from RGB and depth maps.

The aforementioned approach has made significant contributions to feature extraction and fusion. Building upon prior research, CFANet takes into full consideration the distinct characteristics of depth maps and RGB im-ages. It employs appropriate modules to extract features from these two modalities separately and ensures an interaction between the RGB branch and depth map branch, avoiding a simplistic view of the depth map merely as a complement to the RGB image.

2.2. Attention Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms aim to mimic the human visual selective attention capability by assigning weights based on the importance of different parts in a feature map. The attention mechanisms proposed by scholars can be categorized into four types: spatial attention, channel attention, spatial and channel mixed attention, and self-attention.

Spatial attention enhances the network's ability to capture important objects in the feature map by applying weighted operations across different regions in the spatial dimension. Mnih et al. [

17] perform multi-level attention focusing at different scales through simultaneous processing of sequence and spatial data, showcasing strong adaptability and flexibility at the expense of higher computational complexity. Jaderberg et al. [

18] address the issue of input images being non-amenable to geometric transformations by designing a parameterized spatial transformer sub-network, converting the geometric rectification process into a differentiable operation chain, enabling the model to learn the optimal sample spatial registration strategy in an end-to-end manner. Huang et al. [

19] mitigate the high computational complexity and resource consumption issues associated with traditional non-local methods by introducing Criss-Cross Attention. This mechanism captures correlated features along both horizontal and vertical directions, computing the correlation only between the target pixel and its row and column positions with significant spatial correlation, and integrates long-range dependency information through an adaptive weighted fusion strategy.

Channel attention aims to address the issue of feature channel dependency by adaptively assigning weights to channels, thereby enhancing useful features. Hu et al. [

20] compress the feature map into a multidimensional vector, assign weights to the parameters in the vector through a loss function, and dynamically adjust the original feature map based on their importance. Qin et al. [

21] extend the global average pooling operation in the channel attention mechanism to a two-dimensional discrete cosine transform (DCT) form, demonstrating that global average pooling is a special case of two-dimensional DCT. This introduces more frequency components to fully extract feature information. Wang et al. [

22] believe that the dimensionality reduction operation in [

20] has negative impacts. They propose an Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module. ECA uses one-dimensional convolutions to acquire information from adjacent channels, yielding more precise channel attention information. ECA can adaptively adjust the size of the one-dimensional convolution in the module, allowing high-dimensional channels to have longer-range interactions and low-dimensional channels to have shorter-range interactions. Yang et al. [

23] combine gating mechanisms and normalization methods to selectively model different channel feature information.

Spatial and channel mixed attention adaptively selects important channels and spatial regions, weighting and summing the results of channel attention and spatial attention to obtain a blended feature vector. Woo et al.'s [

24] proposed Convolutional block attention module (CBAM) consists of two parts: the Channel Attention Module (CAM) focuses on the importance of each channel, capturing significant features in the image, while the Spatial Attention Module (SAM) selects for each spatial position, capturing meaningful local regions in the image. Hu et al. [

25], utilizing the concept of feature separation and interaction, explore relationships between image features, but encounter the issue of information loss during information exchange and recombination. Fu et al.[

26], employing a spatial pyramid attention mechanism, effectively handle feature information at different scales, enhancing the model's representational capacity. However, this model has a higher computational complexity, resulting in substantial training and tuning costs, requiring significant computational resources and time investment.

Self-Attention was initially applied in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) due to its powerful ability to model global contextual information. Dosovitskiy et al. [

27] split input vectors into designated heads and independently compute self-attention for each head. Each head learns different features independently, complementing and collaborating with each other, thereby enhancing the model's expressive capacity. Liu et al.[

28], to ad-dress the computational complexity and loss of inter-token correlation information when dealing with high-resolution images in self-attention mechanisms, introduce a sliding window mechanism. The sliding window multi-head self-attention layer segments the input tensor into non-overlapping blocks and performs multi-head self-attention calculations on each block. Dong et al. [

29] propose the innovative Cross Sliding Window Self-Attention (CSWin Transformer), which adopts a cross-shaped window self-attention mechanism (CW-MSA) to replace the W-MSA and SW-MSA modules in Swin Transformer. This enables local modeling of input features, preserving more detailed information and fully utilizing global features, significantly improving model accuracy without increasing computational complexity.

Building upon these outstanding research contributions, we constructed CFANet. In CFANet, we integrated Criss-Cross Attention [

19] into BFEM. DFEM utilizes attention mechanisms to extract significant unimodal features from the spatial and channel dimensions of the depth map. AFCFM employs Multi-Head Attention to align RGB features and depth map features. Drawing inspiration from attention mechanisms, it enhances the complementary information between the two modalities and diminishes redundant information.

3. Method

3.1. Overview of the Architecture

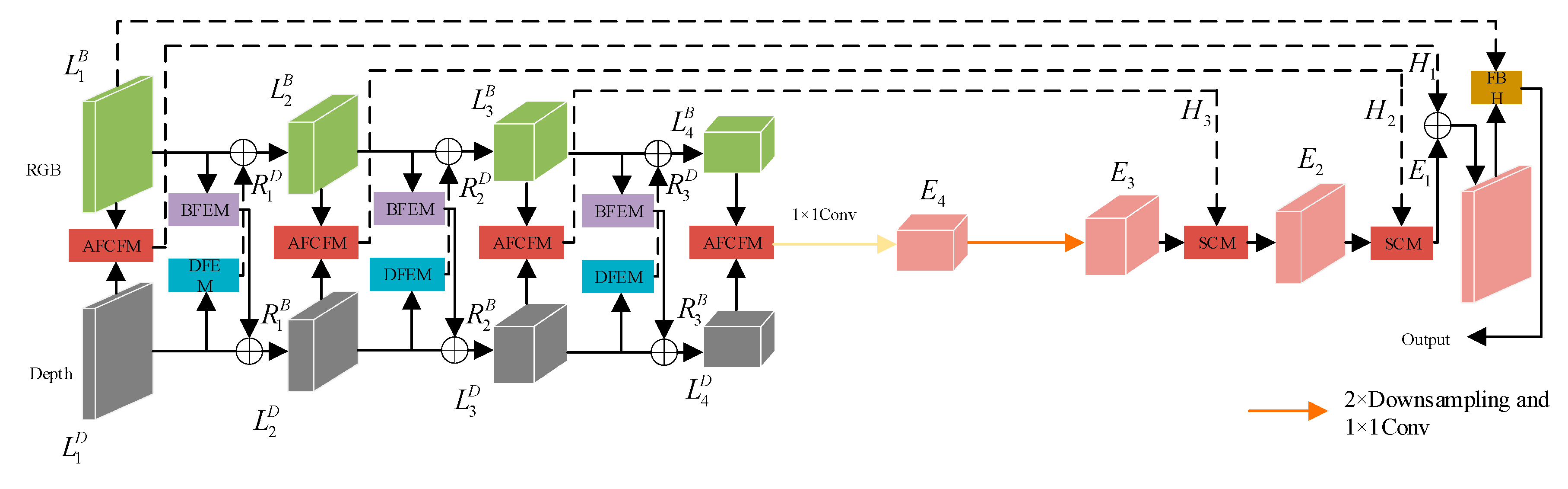

Figure 3 illustrates the framework of CFANet proposed in this paper, which adopts the classical encoder-decoder architecture to achieve end-to-end semantic segmentation. During the encoding phase, RGB images and depth maps are input separately into their respective network branches. In both branches, we employ ResNet50[

20] to extract features from the images, yielding four feature maps at different resolutions for each type of image.

(i=1,2,3,4) represent the extracted RGB image features, and

represent the extracted depth image features. BFEM is designed to develop RGB image features enriched with contextual information, while DFEM focuses on capturing significant unimodal features from the depth map. Applying BFEM to

results in the re-extracted feature maps

. The addition of

and

produces new feature maps

, and the addition of

and

produces a new feature map

, facilitating feature interaction. This process is illustrated by the following formula (1):

As illustrated in

Figure 3, to mitigate the semantic gap present in different modal images, AFCFM is employed to merge feature maps from different modalities, resulting in the fused features

, as described in the following text. SCM designed in this paper strikes a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Considering the unique characteristics of

and

, we have developed the Feature Refinement Head (FRH). The FRH further refines the feature maps from both spatial and channel perspectives.

3.2. RGB Feature Extraction Module and Depth Map Feature Extraction Module

The modal differences between RGB images and depth maps are primarily manifested in the way information is expressed. RGB images offer rich information about object color, texture, and appearance, while depth maps provide information about the distance or depth of objects, allowing for a better description of spatial relation-ships and shape information between objects in the scene. Because these two modalities provide distinct information, effectively leveraging both becomes a crucial challenge in RGB-D semantic segmentation tasks. To ad-dress this challenge, we have tailor-made two feature extraction modules to suit the characteristics of different modal data.

3.2.1. RGB Feature Extraction Module

Indoor RGB images exhibit the following characteristics: (1) Indoor scenes comprise objects of various scales, such as small-sized decorations and large-sized wardrobes. (2) Indoor image backgrounds are complex, potentially containing numerous background objects similar to the target objects. To address these challenges, there is a need to increase the receptive field and learn rich contextual information. In previous research, dilated convolutions were introduced to enlarge the receptive field without introducing a large number of parameters. However, dilated convolutions may lead to a loss of correlation between adjacent pixels. The BFEM not only alleviates the aforementioned challenges but also enables the learning of abundant contextual information.

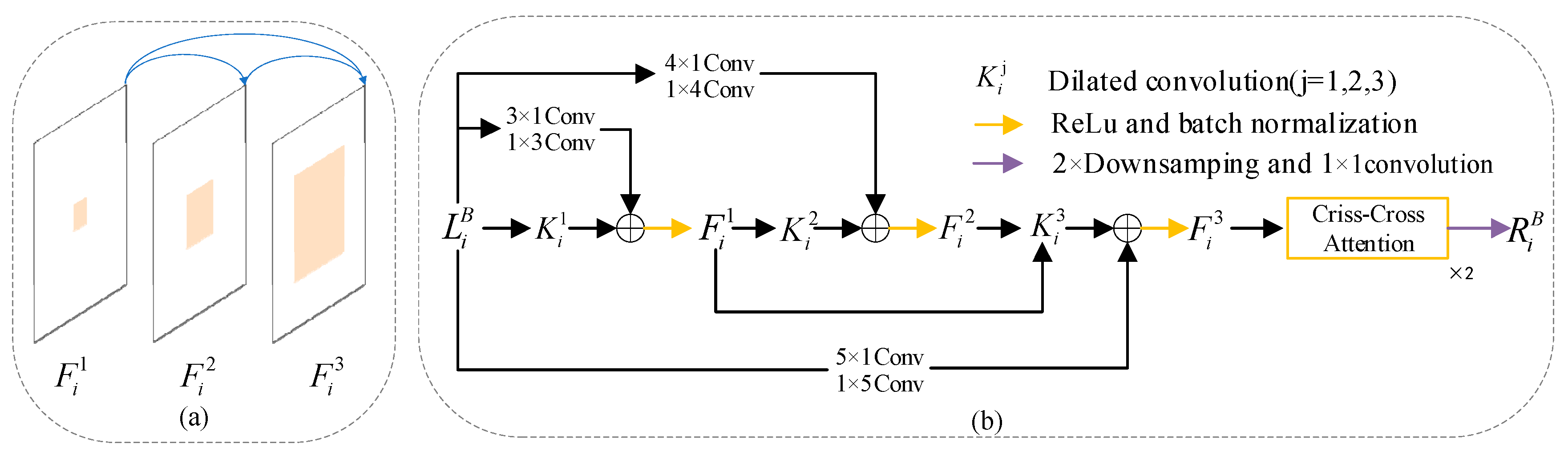

To mitigate the gridding issue associated with dilated convolutions, BFEM incorporates asymmetric convolutions [

30]. The structure of BFEM is illustrated in

Figure 4. After filtering the feature map

with dilated convolutions, we immediately fuse it with the feature map processed by the corresponding asymmetric convolutions. Additionally, we sum up the previously processed feature maps to enhance dense connections, as shown in

Figure 4(a). Dense connections allow for the repeated reuse of signals, providing substantial expansion of the receptive field and enabling the learning of more contextual information [

22]. We implement the above processes using the following formula (2):

In the formula (2),(;)represents the feature map generated after each densely connected operation;represents the dilated convolution with a dilation rate of 1,represents the dilated convolution with a dilation rate of 2, andrepresents the dilated convolution with a dilation rate of 3;represents a 3×1 convolution followed by a 1×3 convolution,represents a 4×1 convolution followed by a 1×4 convolution, andrepresents a 5×1 convolution followed by a 1×5 convolution;represents the feature map generated by the i-th layer in the RGB network branch;is a 2×downsampling followed by a 1×1 convolution.

In order to effectively capture global contextual information while mitigating computational overhead, we employed cross-cross attention [

19]. The feature map undergoes two cross-cross attention operations to yield

,as shown in

Figure 4(b).

3.2.2. Depth Map Feature Extraction Module

Indoor depth maps may contain noise, especially in regions with uneven lighting or texture absence. Consequently, features provided by the depth map may introduce information detrimental to segmentation accuracy. To alleviate this issue, we employ DFEM to extract significant unimodal features in both spatial and channel dimensions.

The structure of DFEM is illustrated in Figure 5. The two upper branches extract weighted features of

from the spatial dimension, while the two lower branches extract weighted features of

from the channel dimension. Specifically, the two upper branches take the feature maps processed by global max-pooling and global average-pooling, input them into a 3×3 convolution for adaptive parameter updates, apply a sigmoid function to obtain spatial feature weights, and finally perform element-wise multiplication of the spatial feature weights with the input feature

to obtain spatial-weighted features. Similarly, the two lower branches take the feature maps processed by channel max-pooling and channel average-pooling, input them into a 3×3 convolution for adaptive parameter updates, apply a sigmoid function to obtain channel feature weights, and finally perform element-wise multiplication of the channel feature weights with the input feature

to obtain channel-weighted features. The spatial-weighted features and channel-weighted features are added, and after 2×downsampling followed by 1×1 convolution to adjust the channel number, the result

is obtained. This process is illustrated by the following formula (3):

In the formula (3), when,represents global max pooling; when,represents global average pooling; when,represents channel max pooling; and when,represents channel average pooling.denotes element-wise multiplication,signifies a 3×3 convolution.is the sigmoid function, andrepresents a 2×downsampling followed by 1×1 convolution.

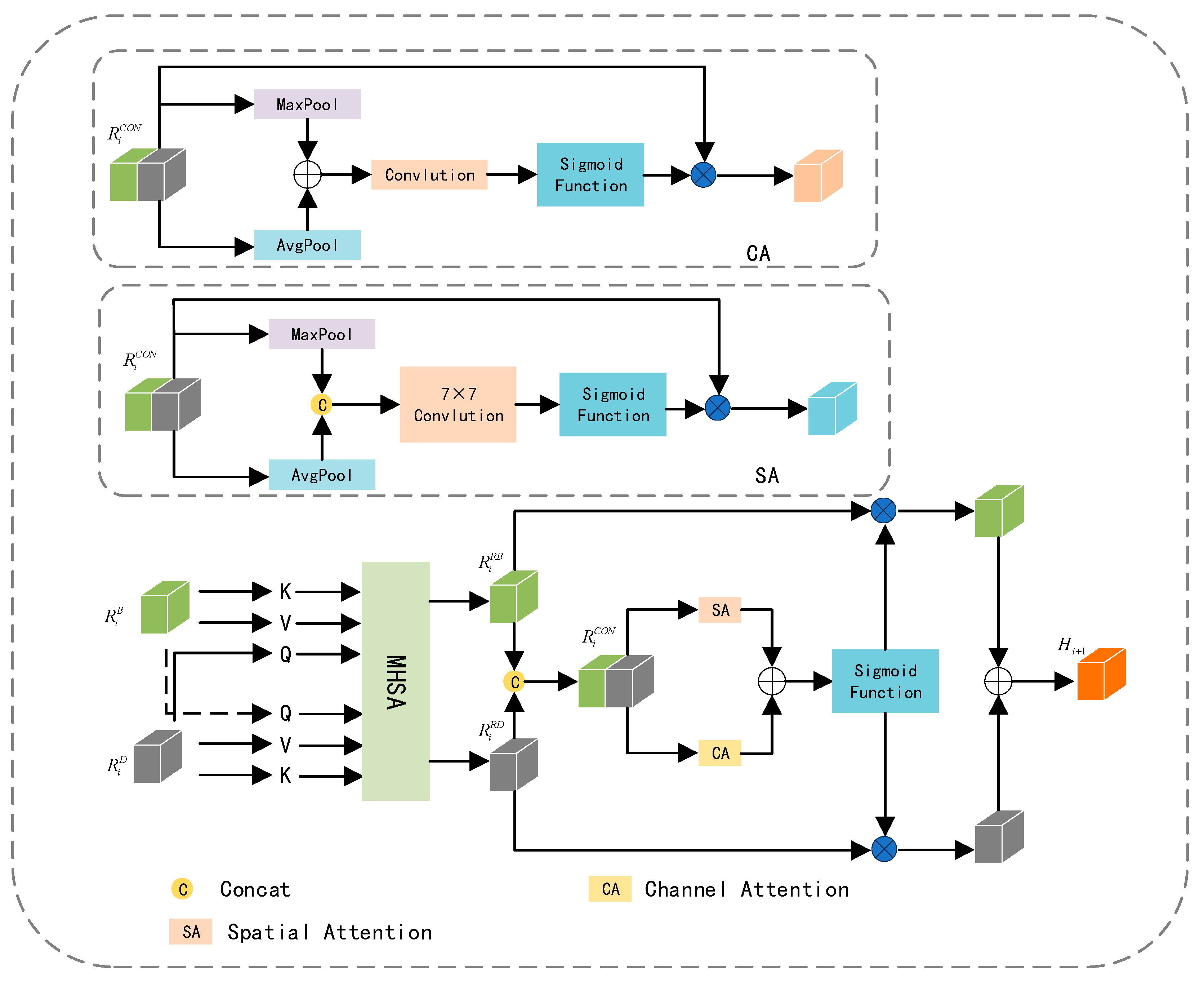

3.3. Adaptive Feature Complementary Fusion

The feature maps extracted from RGB and depth images not only contain complementary information but al-so entail redundant details. Striking a balance between enhancing complementary information and reducing redundancy is our objective. Leveraging the potent feature representation capabilities of the Multi-Head Attention [

31], which empowers the model to learn relationships between different parts and representations effectively. AFCFM utilizes a Multi-Head Attention mechanism to adaptively align the feature maps generated from RGB and depth images. Subsequently, it enhances the representation of complementary information from both channel and spatial perspectives, mitigating redundancy.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the feature map

obtained from the RGB image branch and the feature map

obtained from the depth image branch are linearly mapped to derive

,

and

. It is noteworthy that, to align

and

, this paper employs

as one of the inputs for the Multi-Head Attention mechanism between them. This process can be described by the following formula (4):

In the formula (4),represents the Multi-Head Attention.is the vector obtained from the RGB image, andis the vector obtained from the depth image. represents the aligned RGB feature map, andrepresents the aligned depth feature map after the alignment process.

Influenced by the idea of the attention mechanism, we assign different weights to

and

to enhance complementary information while reducing redundancy. In specific experiments, we adopt the framework of CBAM [

24] and apply the Attention mechanism separately in the channel and spatial dimensions. However, the original Channel Attention mechanism in CBAM employs two consecutive fully connected layers, and the dimension reduction operation in it has a negative impact on the prediction of Channel Attention, resulting in lower computational efficiency. We replace this with a simple one-dimensional convolution to adaptively explore the weights for each channel. The Channel Attention Module's structure is represented as CA in

Figure 6, and the structure of Spatial Attention is denoted as SA. The weight information obtained from CA and SA is then mapped to

and

, and the fused feature

is derived through addition. This process can be described by the following formula (5) and formula (6):

In the formulas,represents Spatial Attention,represents Channel Attention.is the sigmoid function,is element-wise multiplication.is the fused feature map obtained after the attention mechanisms..

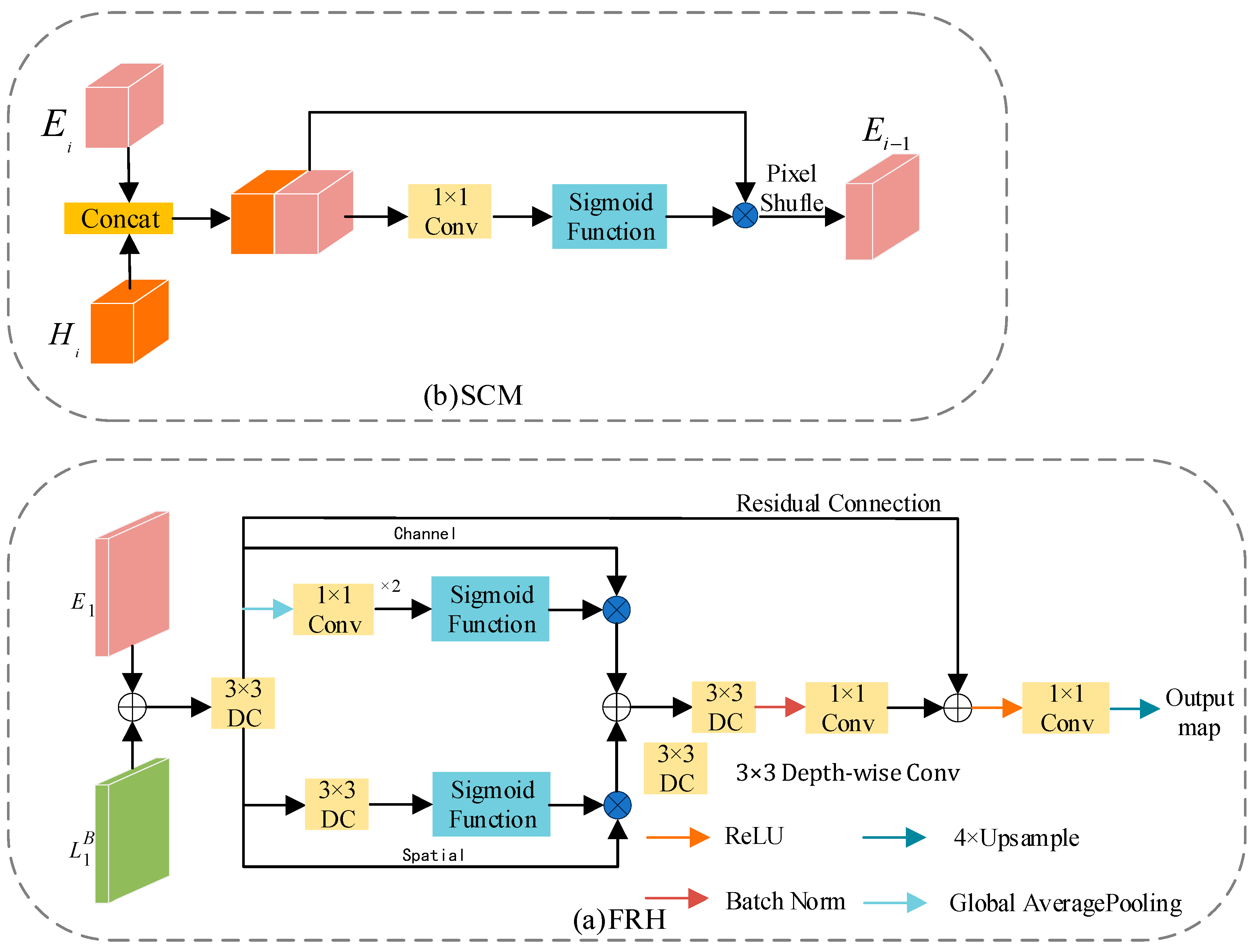

3.4. Skip Connection Module and Feature Refinement Head

The feature maps generated by the encoder retain rich detailed information but lack semantic content Conversely, those generated by the decoder contain abundant semantic information but suffer from significant in-formation loss as the network deepens. In previous studies, a common approach has been to perform a simple addition operation on these two feature maps. While computationally less intensive, this approach compromises semantic segmentation accuracy. To address this, we propose two efficient modules, namely SCM and RFH.

3.4.1. Feature Refinement Head

The structure of FRH is illustrated in

Figure 7(a). FRH module aims to deeply fuse

and

, maximizing the utilization of both detailed and semantic information. Building upon feature fusion, the feature maps undergo refinement through spatial and channel branches. Specifically, the spatial branch employs 3×3 depthwise separable convolutions to generate attention maps, aiming to reduce parameter count and enhance computational efficiency. The channel branch, on the other hand, first compresses the feature maps into a one-dimensional vector using global average pooling. It then utilizes 1×1 convolutions to reduce the number of channels to one-fourth of the original, followed by another 1×1 convolution to restore it to the original channel count. This operation is in-tended to increase network depth while mitigating the risk of overfitting. Ultimately, the feature maps generated by the spatial and channel paths are further fused through summation. Additionally, to prevent network degradation during training, this paper introduces a residual connection mechanism, enhancing the stability and effectiveness of network training.

3.4.2. Skip Connection Module

In previous studies, the common practice was to use a simple addition operation on feature maps or employ complex modules to fuse feature maps from the decoding and encoding stages. Unlike prior research, we utilize Concatenation to combine the feature maps input to SCM, obtaining features with higher representational capacity. In contrast to more complex models, we use only a 1×1 convolution to update parameters. Additionally, SCM employs Pixel Shuffle [

32] to reorganize channels, enabling an increase in feature map resolution and retention of more detailed information without introducing new parameters. The structure of SCM is illustrated in

Figure 7(b). This process can be described by the following formula (7):

Wheredenotes Pixel Shuffle,represents Concat operation,is the sigmoid function,is element-wise multiplication.signifies a 1×1 convolution.

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset and Metrics

The SUN-RGBD dataset is a highly comprehensive dataset for indoor scene understanding, comprising 10,335 pairs of images depicting various indoor scenes such as living rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, bathrooms, and more. A total of 37 different object categories are annotated in this dataset. Among the images, 5,285 are designated for training, while 5,050 images are reserved for testing purposes.

The NYUDv2 dataset is composed of video sequences capturing various indoor scenes recorded by Microsoft Kinect's RGB and Depth cameras. This dataset comprises 1,449 pairs of densely annotated RGB and depth im-ages, covering a total of 40 different object categories. These categories encompass various objects commonly found in indoor scenes, including chairs, tables, TVs, people, and more. The dataset is split into a training set with 795 images and a test set containing the remaining 654 images.

We measured the proposed CFANet with state-of-the-art methods according to three measures: mean accuracy (mAcc.), pixel accuracy (PixAcc.), and mean intersection over union (mIoU).

4.2. Implementation Details

CFANet is implemented using the PyTorch framework on 2 NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPUs. A ResNet50 pretrained on ImageNet is employed as the backbone network for CFANet. During the training phase, all input images are uniformly cropped to a resolution of 480×640 pixels. To enhance the model's generalization ability, data augmentation techniques such as random scaling, random cropping, random horizontal flipping, random brightness adjustment, and random saturation adjustment are implemented. For optimization, we utilize a stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm with a momentum value of 0.9 and a weight decay factor of 0.0004 as the optimizer. The learning rate is adjusted using a polynomial decay strategy, with the polynomial exponent set to 0.9 and the initial learning rate set to 0.009. Considering the characteristics of different datasets, we set specific training epochs and batch sizes: for the NYUDv2 dataset, the training process spans 250 epochs with each batch containing 6 images; for the SUN-RGBD dataset, the training process spans 200 epochs with each batch containing 4 images. The cross-entropy loss function is employed as the network's loss function.

4.3. Comparison with SOTA Methods

Table 1 summarizes the experimental results of recent semantic segmentation studies on the NYUDv2 dataset, including several models with advanced performance in recent years. We also evaluated our proposed CFANet on the same dataset and compared its performance with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) models. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that CFANet achieves outstanding results in the crucial performance metric mIoU, surpassing the latest SOTA model FCINet [

42] by approximately 2.16%. This unequivocally indicates the significant effectiveness of the novel modules introduced in CFANet. It is noteworthy that, compared to SCN [

35] with ResNet-152 as the backbone network, CFANet exhibits superior performance in mIoU, suggesting that even in a relatively simple network structure, CFANet can enhance the accuracy of semantic segmentation. Compared to TSTNet [

33] with ResNet-34 as the backbone network, CFANet achieves improvements of 7.76%, 5.71%, and 4.97% in mIoU, mACC, and PixACC, respectively, highlighting the effectiveness of applying residual connection strategies in multiple modules of CFANet.

On the larger-scale SUN-RGBD dataset, we validated the effectiveness of CFANet, and the relevant experimental data can be found in

Table 2. Compared to other models in the table, CFANet exhibits excellent performance in mIoU, mACC, and PixACC, showcasing our model's ability to maintain high segmentation accuracy when handling large-scale datasets. Specifically, compared to FCINet with ResNet-50 as the backbone net-work, CFANet achieves a 2.35% improvement in mIoU. Notably, in comparison to models with ResNet-101 as the backbone network in

Table 2, our network, despite employing a relatively shallower feature extraction net-work, still achieves superior segmentation performance. This underscores the remarkable capabilities of CFANet in handling large-scale and rich datasets, providing robust support for its widespread applicability in real-world scenarios.

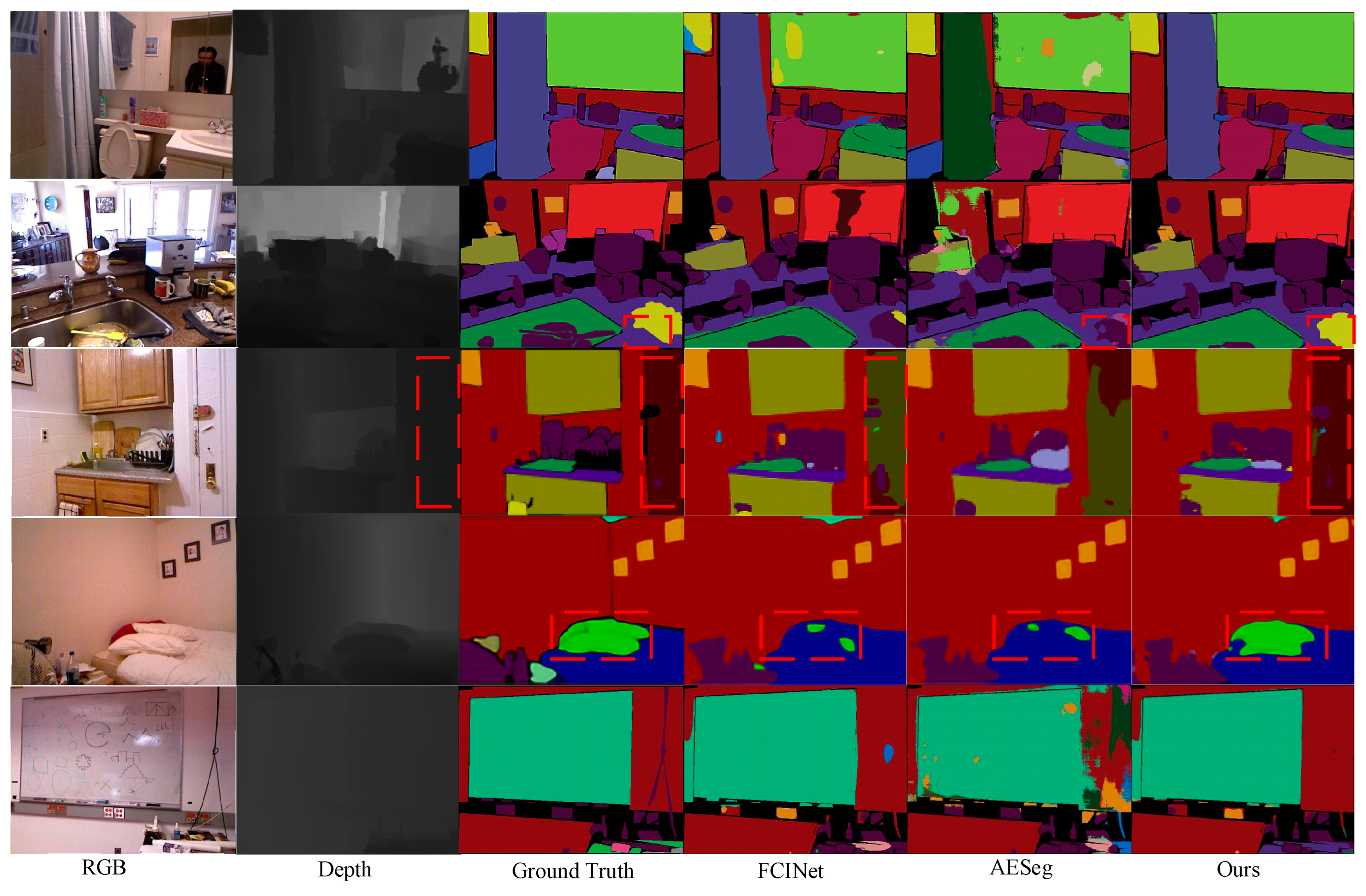

4.4. Visualization Results

To visually showcase the significant advancements of CFANet in semantic segmentation tasks, we provide visualization results on the NYUDv2 dataset, as depicted in

Figure 8. A comparison is made with two state-of-the-art network models.

In the first row, noise is present in the feature extraction of "mirror" predictions from both RGB and depth im-ages. CFANet, by integrating contextual information, accurately achieves the segmentation of the "mirror." In the second row, compared to AESeg utilizing asymmetric convolution, CFANet more accurately segments the object within the red dashed box, highlighting the effectiveness of CFANet's combination of asymmetric convolution and dilated convolution. In the third row, FCINet attempts to enhance the network's segmentation accuracy for objects of different scales using spatial pyramid pooling. However, it performs poorly in segmenting large-scale objects (the object within the red dashed box). In contrast, CFANet achieves relatively advanced results by extracting significant single-modal features from the channel and spatial dimensions of the depth map and interacting with the feature map of the RGB image. In the fourth row, the object within the red dashed box has a similar color to the bed. Both FCINet and AESeg fail to segment this object effectively, while CFANet's segmentation result is superior. This is attributed to the appropriate feature extraction modules applied to RGB images and depth maps. These examples highlight CFANet's superiority in semantic segmentation tasks, emphasizing its effectiveness in fusing multimodal information and segmenting objects of different scales.

4.5. Ablation Studies

The CFANet proposed by us comprises several modules, including BFEM, DFEM, AFCFM, SCM and FBH. To validate the effectiveness of each module, we conducted extensive ablation experiments on NYUDv2, and the experimental results are presented in

Table 3.

4.5.1. Validate BFEM and DFEM

In this section, we designed four different variants of feature interaction, as illustrated in

Figure 9, and obtained experimental results for each variant on the NYUDv2 dataset. The results are recorded in

Table 3. By comparing the experimental outcomes of each variant, we substantiate the effectiveness of our research approach.

As illustrated in

Figure 9(a), we removed the BFEM and DFEM from CFANet (ResNet-50), and the experimental results are presented in the second row of

Table 3, showing a decrease in mIoU by 5.55% compared to CFANet(ResNet-50). In

Figure 9(b), we eliminated the feature interaction between the RGB branch and the Depth branch, resulting in the third row of

Table 3, with a decrease in mIoU by 3.88% compared to CFANet (ResNet-50). This reduction is less significant than the strategy shown in

Figure 9(a), indicating the existence of a semantic gap between the RGB feature map and the Depth feature map, which leads to poor performance when added directly. Therefore, it is necessary to design appropriate modules to extract features from each modality, as proposed in this paper.

As illustrated in

Figure 9(c), we replaced the DFEM of the depth branch with BFEM, and the experimental results are presented in the fourth row of

Table 3, showing a decrease in mIoU by 2.05% compared to CFANet (ResNet-50). This indicates that the DFEM designed in this paper exhibits certain specificity in extracting features from depth maps. Concurrently, the experimental results also validate the effectiveness of employing appropriate feature extraction modules for the RGB and depth map branches, respectively.

In

Figure 9(d), we replaced BFEM of the RGB branch with ASPP, resulting in the fifth row of

Table 3, with a de-crease in mIoU by 2.35% compared to CFANet (ResNet-50). BFEM is an improvement upon ASPP, indicating the effectiveness of our enhancement strategy.

Similar to

Figure 9(d), we replaced DFEM of the Depth branch with ASPP, resulting in the sixth row of

Table 3, with a decrease in mIoU by 2.37% compared to CFANet (ResNet-50). This confirms the effectiveness of DFEM.

4.5.2. Validate AFEM, SCM, and FRH

As shown in the seventh, eighth, and ninth rows of

Table 3, we successively replaced AFEM with element-wise summation, SCM with element-wise summation, and removed FRH. The mIoU decreased by 3.63%, 3.11%, and 2.92% compared to CFANet (ResNet-50), respectively. This indicates that AFEM, SCM, and FRH in CFANet (ResNet-50) are effective.

4.5.3. Validate Backbone Network

To evaluate the impact of different backbone networks on the performance of CFANet, this paper retains all modules of CFANet and only replaces the backbone network. As shown in

Table 4, this paper selects VGG16, ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 as alternatives for the backbone network. Experimental results indicate that CFANet with ResNet-50 as the backbone network significantly outperforms the other three variants in terms of mIoU, validating the rationality of using ResNet-50 as the backbone network for CFANet. In contrast, CFANet with ResNet-18 as the backbone network shows a decline in mIoU, which may be due to the limited representation ability of shallower networks for key features, indicating that it is not advisable to excessively reduce net-work depth to minimize model parameters. Similarly, CFANet with ResNet-101 as the backbone network also shows a slight decline in mIoU, which may be due to the loss of crucial feature information caused by blindly increasing the number of network layers. Overall, the experiments demonstrate that ResNet-50 is the most suitable backbone network for CFANet.

5. Conclusion

In contrast to the conventional homogeneous design of feature extraction modules for both RGB and depth maps, this paper constructs separate feature extraction modules tailored to the characteristics of each. BFEM incorporates asymmetric convolution and cross-cross attention on top of dilated convolutions to alleviate grid-ding effects and capture rich contextual information. DFEM extracts significant unimodal features from both channel and spatial dimensions. For different scales of feature maps, we employ sophisticated strategies: SCM blends multi-scale feature maps, and considering that the first layer contains the richest details while the last layer contains the richest semantic information, we introduce FRH to further fuse and refine these feature maps. CFANet showcases outstanding performance on the NYUDv2 and SUN-RGBD datasets. Visualizations on the NYUDv2 dataset underscore CFANet's exceptional robustness in enhancing multi-scale objects, large-sized objects, and overlapping objects with similar colors. Future research directions will focus on reducing network parameters while maintaining segmentation accuracy and exploring the successful application of CFANet in semantic segmentation for road scenes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-F.W. and D.W.; methodology, L.-F.W; software, L.-F.W.; validation, L.-F.W., D.W. and C.-A.X.; formal analysis, D.W.; investigation, C.-A.X.; resources, D.W. and C.-A.X.; data curation, D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W.; writing—review and editing, L.-F.W.; visualization, L.-F.W.; supervision, D.W.; project administration, C.-A.X.; funding acquisition, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.62101314).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Shanghai University of Engineering Science for your support of this project

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- El Badaoui, R.; Bonmati Coll, E.; Psarrou, A.; Asaturyan, H.A.; Villarini, B. Enhanced CATBraTS for Brain Tumour Semantic Segmentation. Journal of Imaging 2025, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-Z.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.-L.; Cheng, M.-M. Spatial Information Guided Convolution for Real-Time RGBD Semantic Segmentation. Ieee Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 2313–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017. pp. 2881–2890.

- Li, X.; He, H.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Cheng, G.; Shi, J.; Weng, L.; Tong, Y.; Lin, Z. Pointflow: Flowing semantics through points for aerial image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021; pp. 4217-4226.

- Cao, J.; Leng, H.; Cohen-Or, D.; Lischinski, D.; Chen, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, Y. RGBxD: Learning depth-weighted RGB patches for RGB-D indoor semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 2021, 462, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Hou, S.; Karim, A.; Jia, W. RAFNet: RGB-D attention feature fusion network for indoor semantic segmentation. Displays 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. Ieee Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Wu, B.; Hu, Y. Surface defect detection using image pyramid. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 7181–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollár, P.; Appel, R.; Belongie, S.; Perona, P. Fast feature pyramids for object detection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2014, 36, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazerouni, A.; Karimijafarbigloo, S.; Azad, R.; Velichko, Y.; Bagci, U.; Merhof, D. Fusenet: self-supervised dual-path network for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI); 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, D.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Z. Multi-resolution Cascaded Network with Depth-similar Residual Module for Real-time Semantic Segmentation on RGB-D Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Networking, 30 Oct.-2 Nov. 2020, 2020, Sensing and Control (ICNSC); pp. 1–6.

- Zhou, W.; Yang, E.; Lei, J.; Yu, L. FRNet: Feature Reconstruction Network for RGB-D Indoor Scene Parsing. Ieee Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2022, 16, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yuan, J.; Lei, J.; Luo, T. TSNet: Three-Stream Self-Attention Network for RGB-D Indoor Semantic Segmentation. Ieee Intelligent Systems 2021, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Leng, H.; Lischinski, D.; Cohen-Or, D.; Tu, C.; Li, Y. ; Ieee. In ShapeConv: Shape-aware Convolutional Layer for Indoor RGB-D Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Electr Network, 2021, 2021 Oct 11-17; pp. 7068–7077. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Xue, J.H.; Xie, P.; Yang, S.; Wang, G. Non-Local Aggregation for RGB-D Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2021, 28, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yue, Y.; Fang, M.; Qian, X.; Yang, R.; Yu, L. BCINet: Bilateral cross-modal interaction network for indoor scene understanding in RGB-D images. Information Fusion 2023, 94, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Heess, N.; Graves, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Recurrent models of visual attention. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Jaderberg, M.; Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Spatial transformer networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, W. Ccnet: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019; pp. 603-612.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 7132-7141.

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wu, F.; Li, X. Fcanet: Frequency channel attention networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 783-792.

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 11534-11542.

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y. Gated channel transformation for visual recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 11794-11803.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018; pp. 3-19.

- Hu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; He, F.; Zhang, J. SA-Net: A scale-attention network for medical image segmentation. PloS one 2021, 16, e0247388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual attention network for scene segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 3146-3154.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 10012-10022.

- Dong, X.; Bao, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Yu, N.; Yuan, L.; Chen, D.; Guo, B. Cswin transformer: A general vision transformer backbone with cross-shaped windows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 12124-12134.

- Ding, X.; Guo, Y.; Ding, G.; Han, J. Acnet: Strengthening the kernel skeletons for powerful cnn via asymmetric convolution blocks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019; pp. 1911-1920.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, H.; Tan, Z.; Chen, L.; Wan, W.; Cao, J. Efficient sub-pixel convolutional neural network for terahertz image super-resolution. Optics letters 2022, 47, 3115–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yuan, J.; Lei, J.; Luo, T. TSNet: Three-stream self-attention network for RGB-D indoor semantic segmentation. IEEE intelligent systems 2020, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, I.; Tuan-Hung, V.; de Charette, R. ; Ieee. In Cross-task Attention Mechanism for Dense Multi-task Learning. In Proceedings of the 23rd IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, 2023, 2023 Jan 03-07; pp. 2328–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, R.; Ji, Y.; Li, P.; Huang, H. SCN: Switchable context network for semantic segmentation of RGB-D images. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2018, 50, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Yan, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Dong, X. TCANet: three-stream coordinate attention network for RGB-D indoor semantic segmentation. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2024, 10, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Seichter, D.; Köhler, M.; Lewandowski, B.; Wengefeld, T.; Gross, H.-M. Efficient rgb-d semantic segmentation for indoor scene analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA); 2021; pp. 13525–13531. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Qi, L.; Huang, H.; Yang, X.; Wan, Z.; Wen, X. CANet: Co-attention network for RGB-D semantic segmentation. Pattern Recognition 2022, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Guo, R.; Tong, X.; Su, S.; Zuo, Z.; Sun, B.; Wei, J. Link-RGBD: Cross-Guided Feature Fusion Network for RGBD Semantic Segmentation. Ieee Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 24161–24175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xiao, Y.; Qiang, F.; Dong, X.; Xu, C.; Yu, L. AESeg: Affinity-Enhanced Segmenter Using Feature Class Mapping Knowledge Distillation for Efficient RGB-D Semantic Segmentation of Indoor Scenes. Neural Networks 2025, 107438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Allibert, G.; Stolz, C.; Ma, C.; Demonceaux, C. Depth-Adapted CNNs for RGB-D Semantic Segmentation. Arxiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Xie, W.; Wang, S. Feature fusion and context interaction for RGB-D indoor semantic segmentation. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 167, 112379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bai, L.; Sun, Y.; Tian, C.; Mao, M.; Wang, G.J.a.e.-p. Pixel Difference Convolutional Network for RGB-D Semantic Segmentation. 2023, arXiv:2302. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Jiang, X.; Shuai, B.; Liu, A.Q.; Wang, G. Semantic Segmentation With Context Encoding and Multi-Path Decoding. Ieee Transactions on Image Processing 2020, 29, 3520–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, K.; Hu, X.; Liu, R.; Stiefelhagen, R.J.a.e.-p. CMX: Cross-Modal Fusion for RGB-X Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. 2022, arXiv:2203. 0483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seichter, D.; Koehler, M.; Lewandowski, B.; Wengefeld, T.; Gross, H.-M. ; Ieee. In Efficient RGB-D Semantic Segmentation for Indoor Scene Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xian, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2021, 2021 May 30-Jun 05; pp. 13525–13531. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Yang, K.; Fei, L.; Wang, K. ; Ieee. In ACNET: ATTENTION BASED NETWORK TO EXPLOIT COMPLEMENTARY FEATURES FOR RGBD SEMANTIC SEGMENTATION. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, TAIWAN, 2019, 2019 Sep 22-25; pp. 1440–1444. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).