Submitted:

30 December 2023

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Isolation Forest Algorithm

2.2. Domain Transform Recursive Filtering

3. Proposed Method

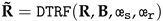

3.1. Spectral Anomaly Detection

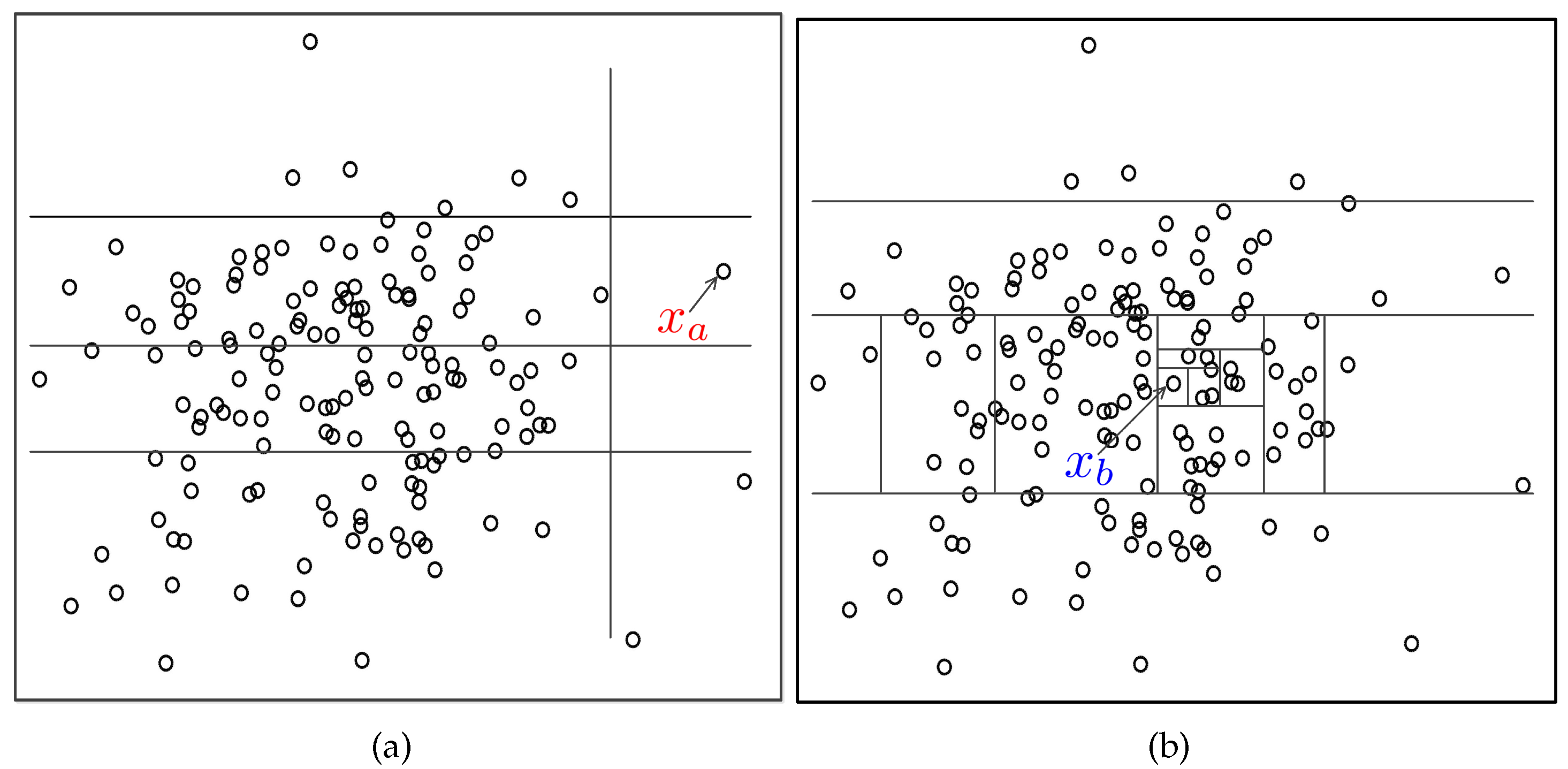

3.2. Spatial Anomaly Detection

| Algorithm 1 Spectral-spatial feature fusion for hyperspectral anomaly detection | |

| Input: | |

| Input hyperspectral data ; | |

| Output: | |

| Detection result | |

| 1: | According to (3), calculate the 2D superpixel segmentation result |

| 2: | Calculate the corresponding 3D superpixels in HSI according to the coordinate of pixels in each 2D superpixel . |

| 3: | Construct isolation forest based on the 3D superpixel in HSI. |

| 4: | Combine the constructed forest and Eq. (6) to compute the spectral anomaly score . |

| 5: | According to Eq. (7), compute the spatial anomaly score . |

| 6: | According to Eq. (8), fuse the spectral and spatial anomaly scores to generate the fused detection result . |

| 7: | According to (9), integrate the spectral and spatial anomaly results to generate the final detection result |

| 8: | Return |

3.3. Decision Fusion

4. Results

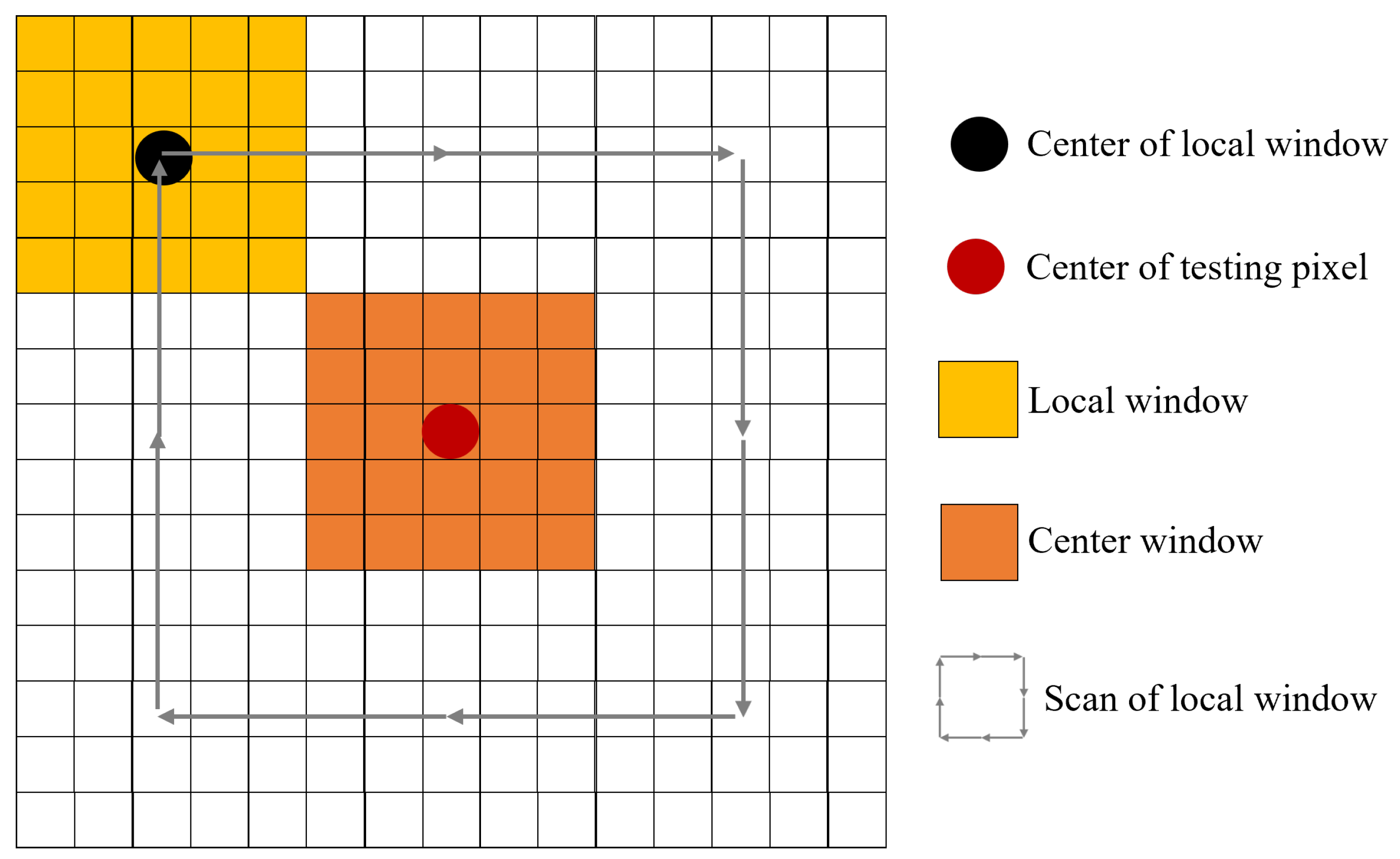

4.1. Experimental Setup

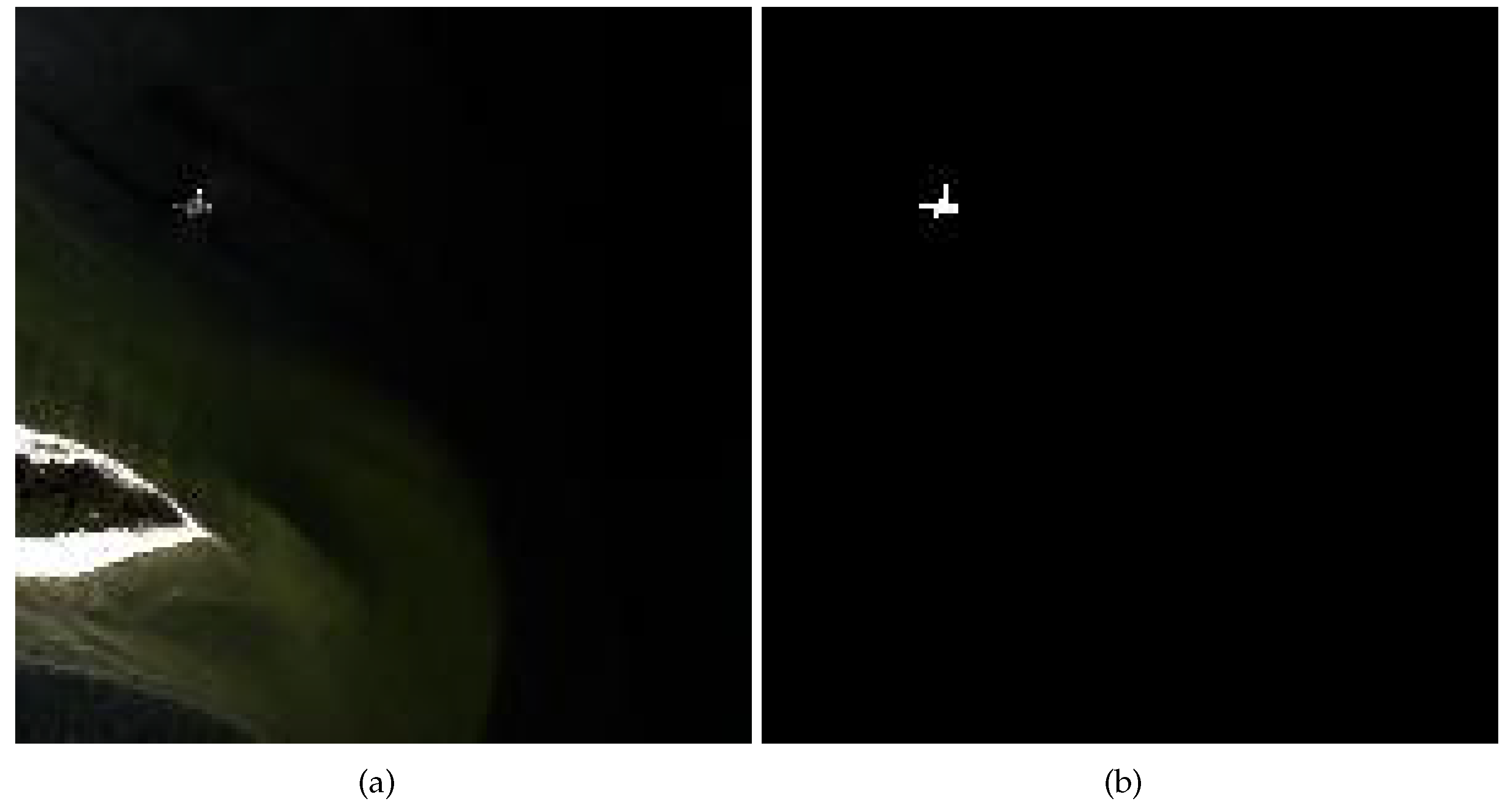

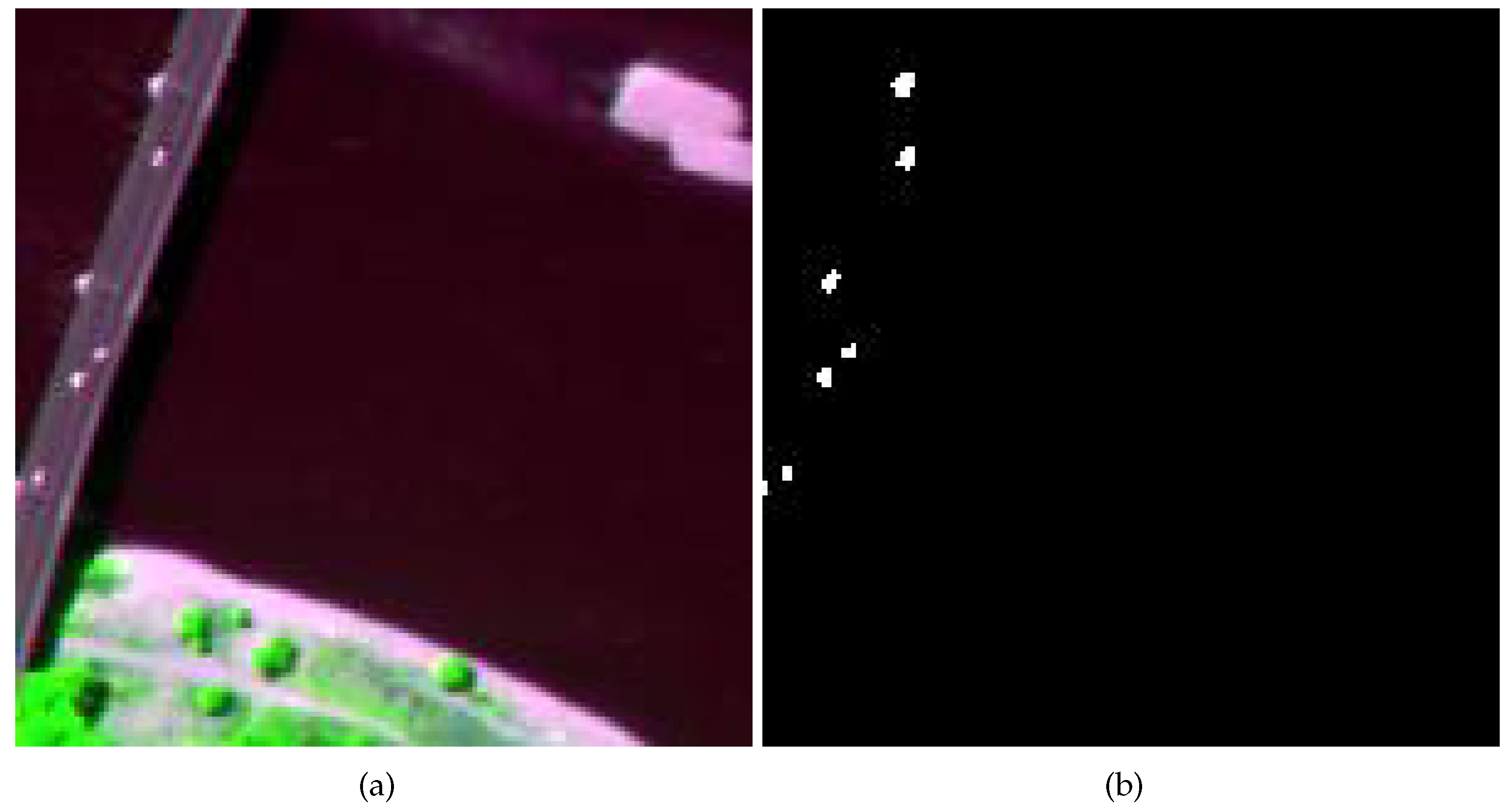

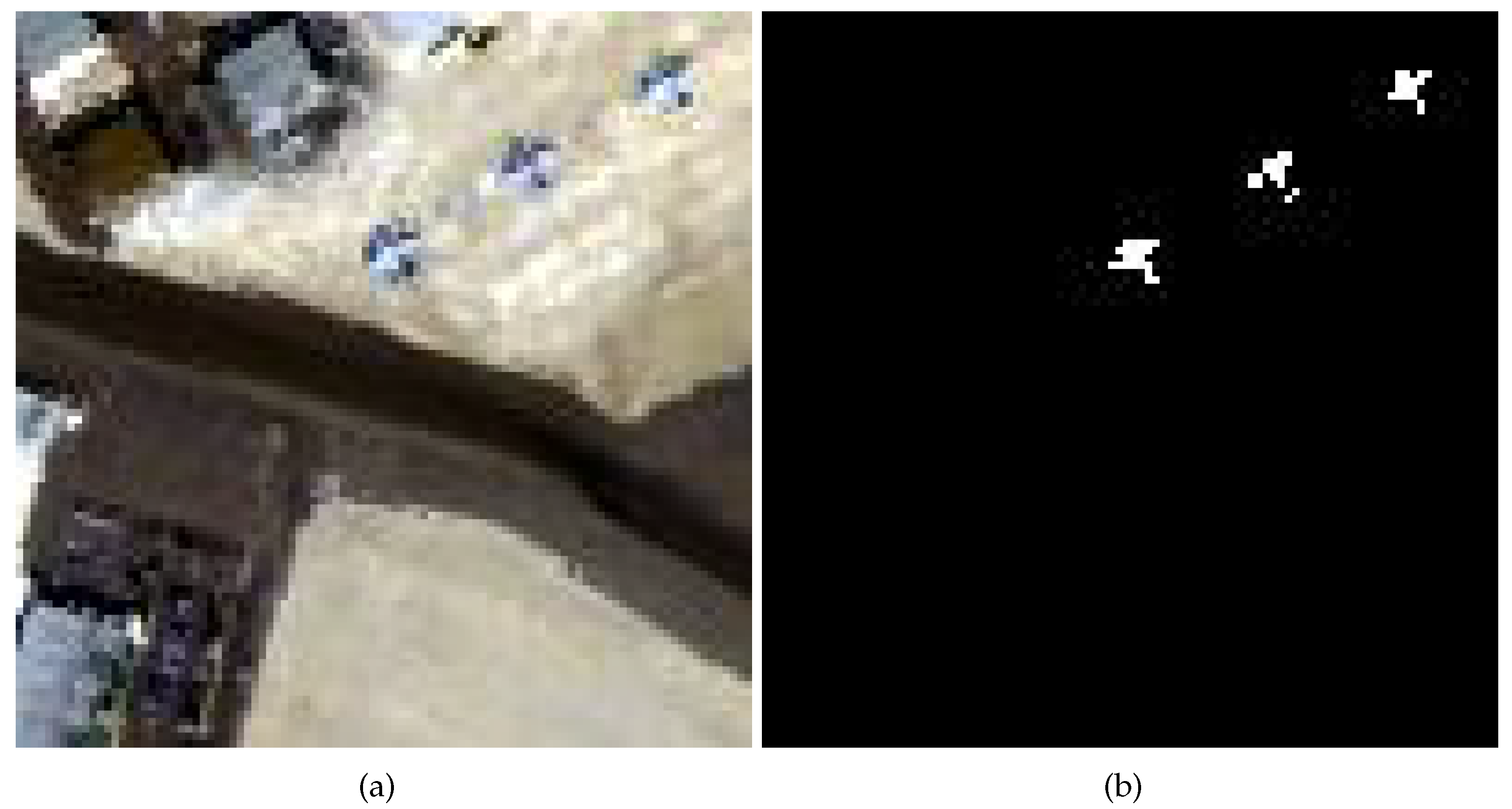

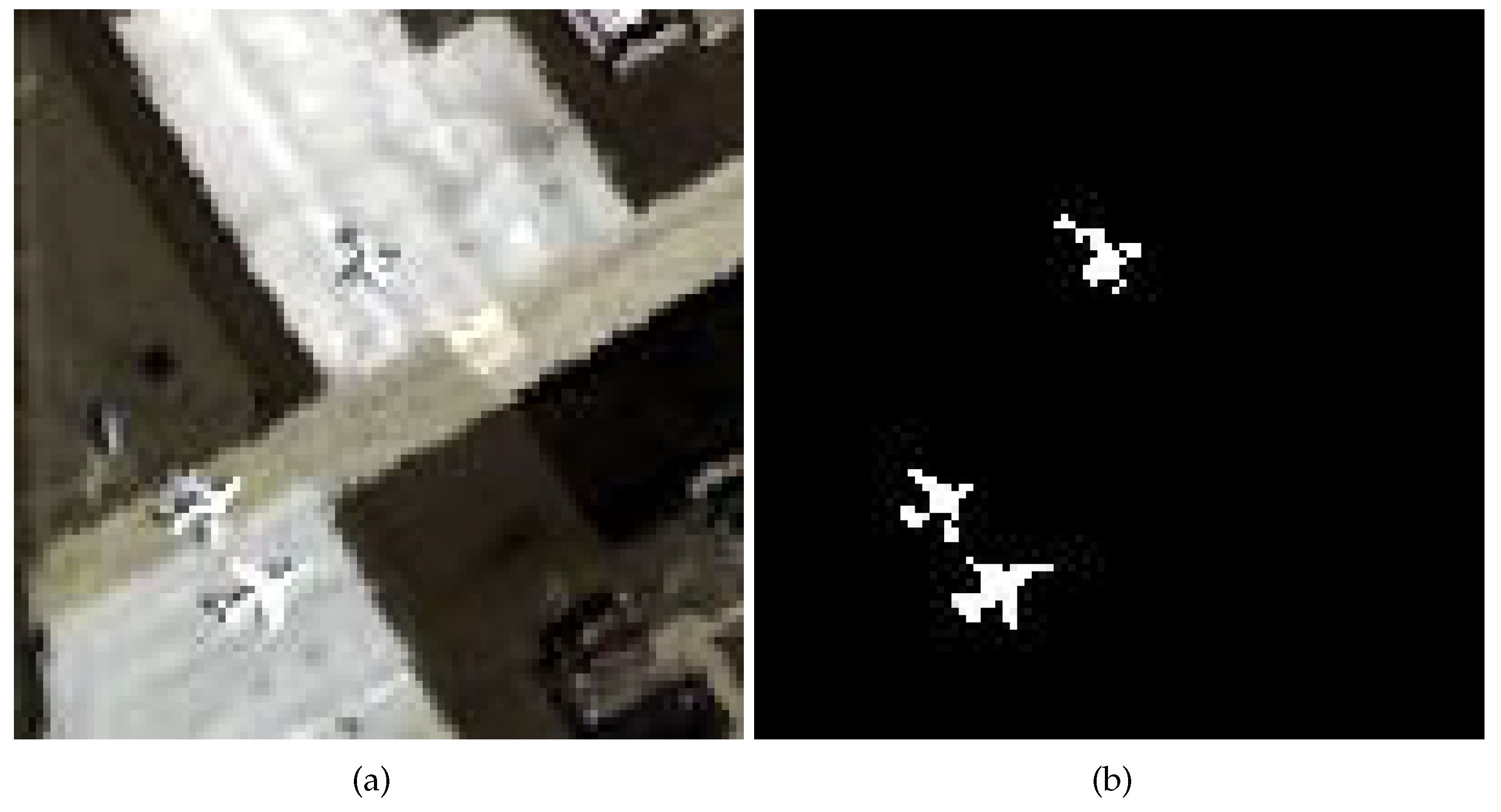

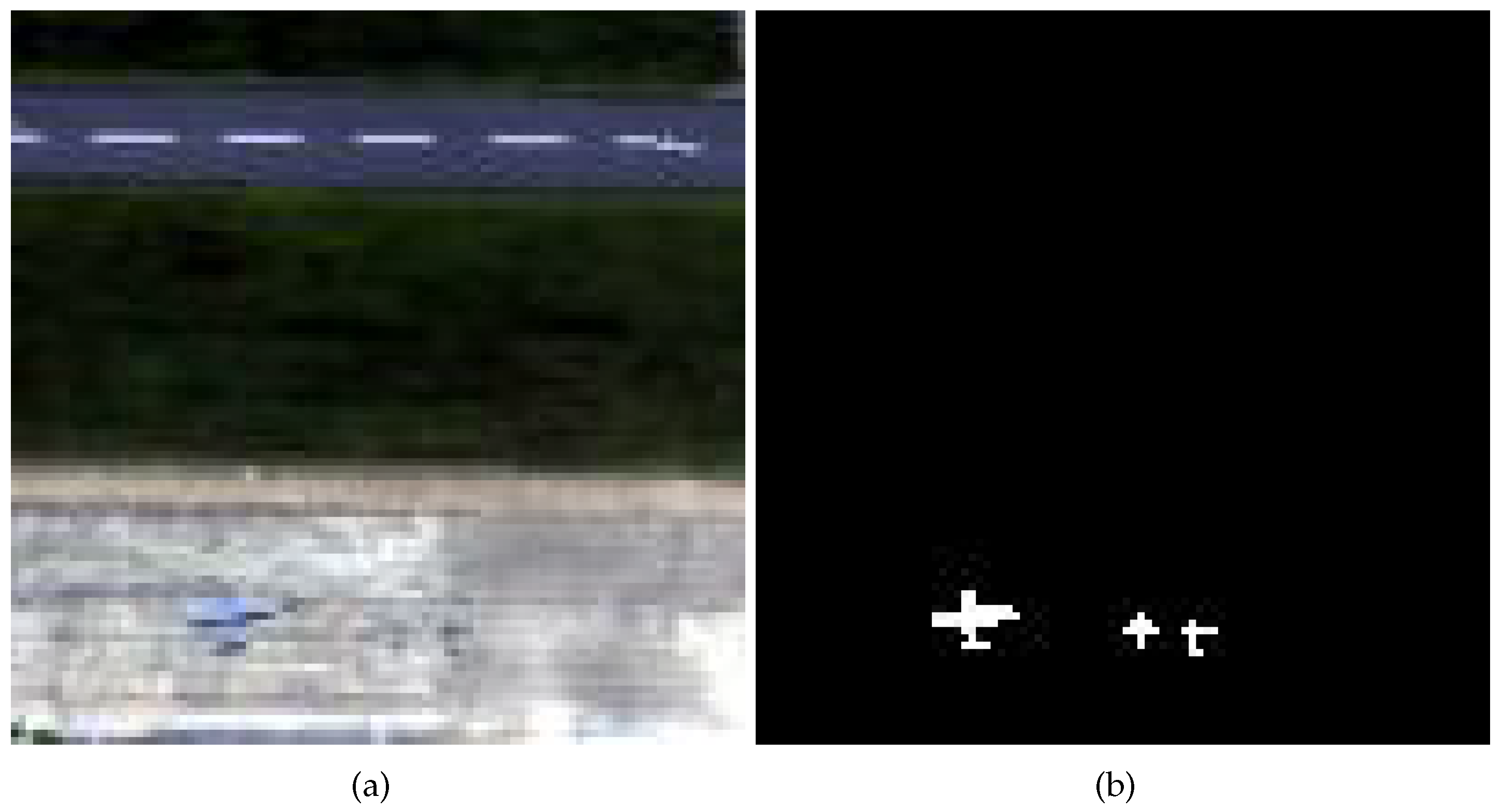

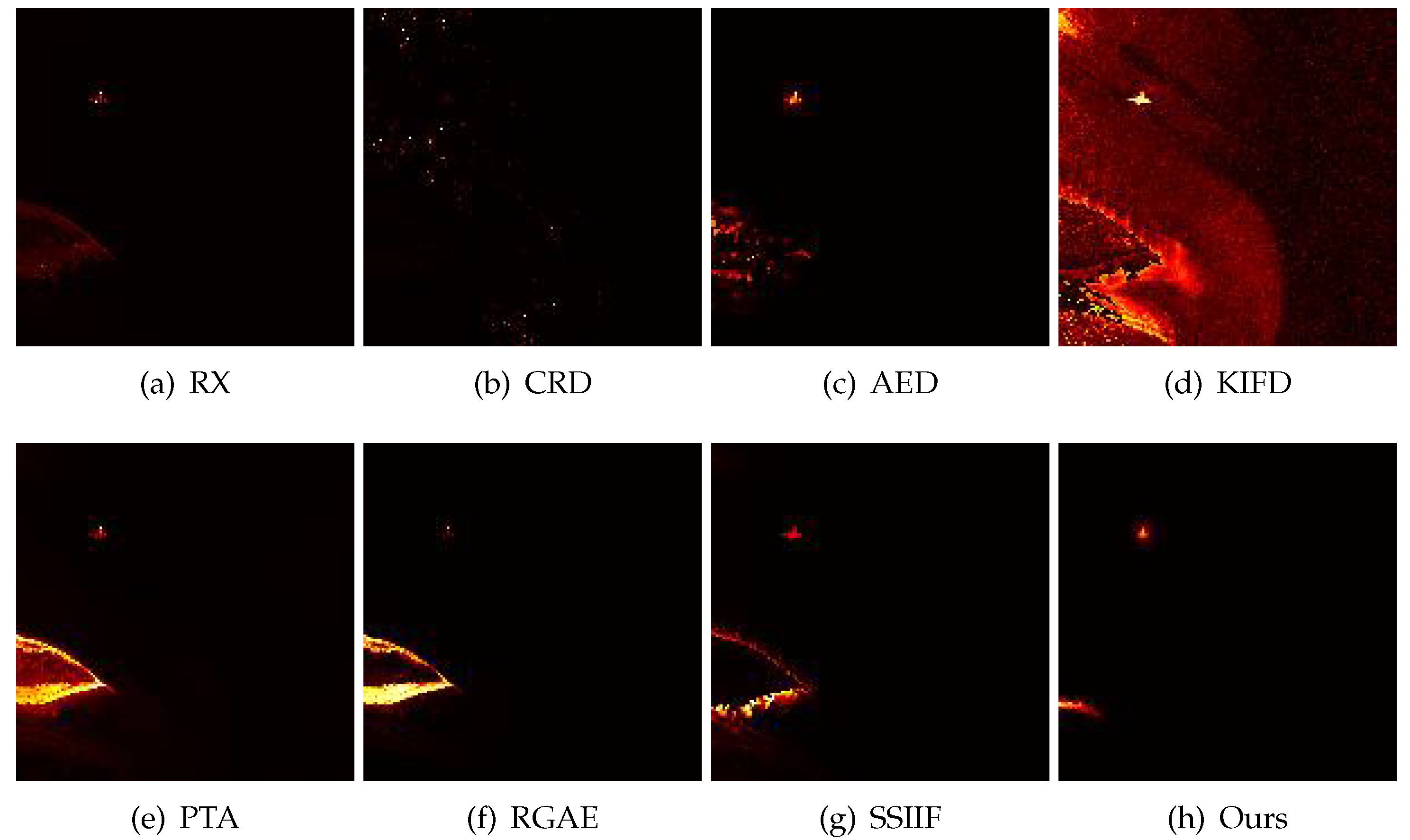

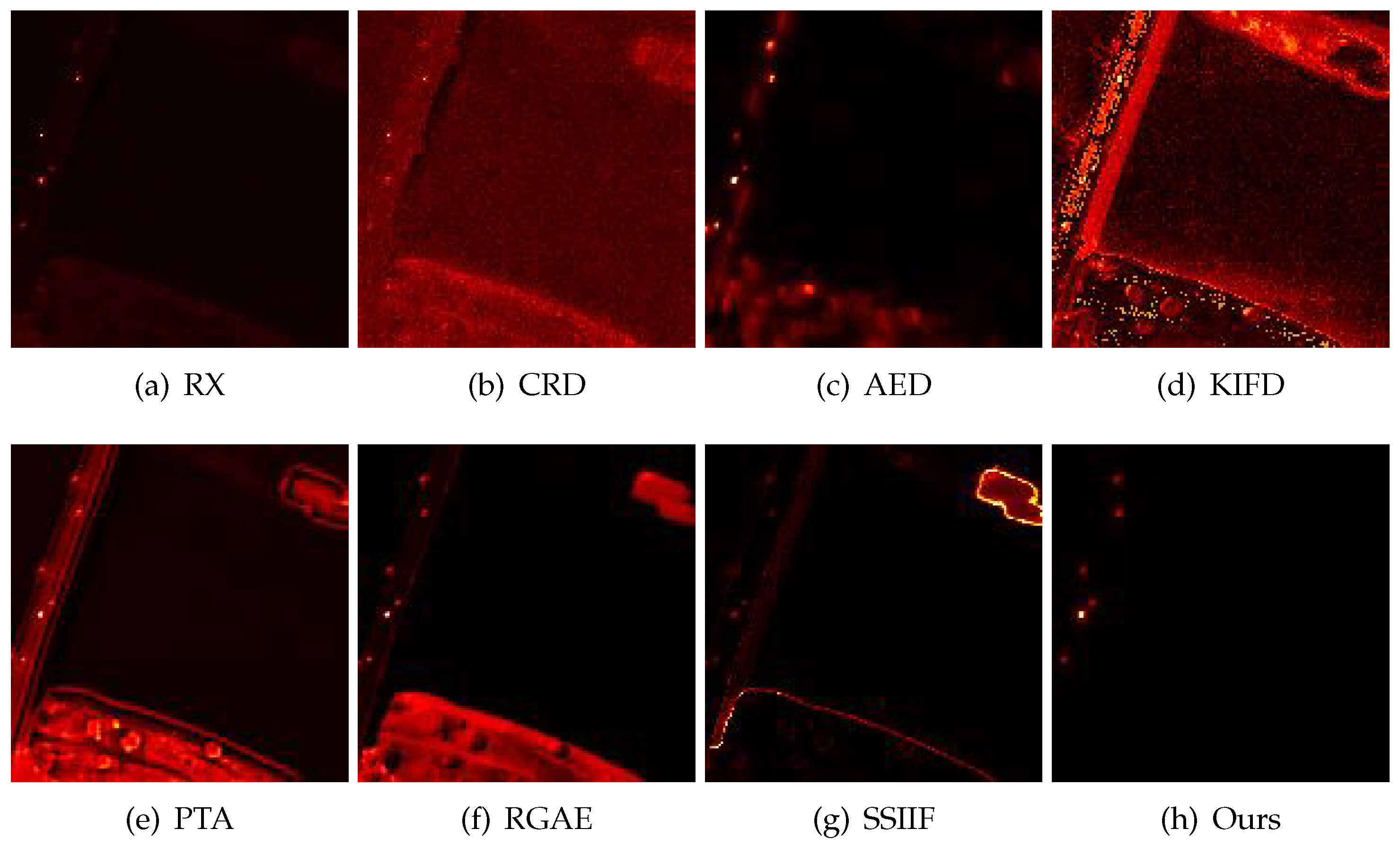

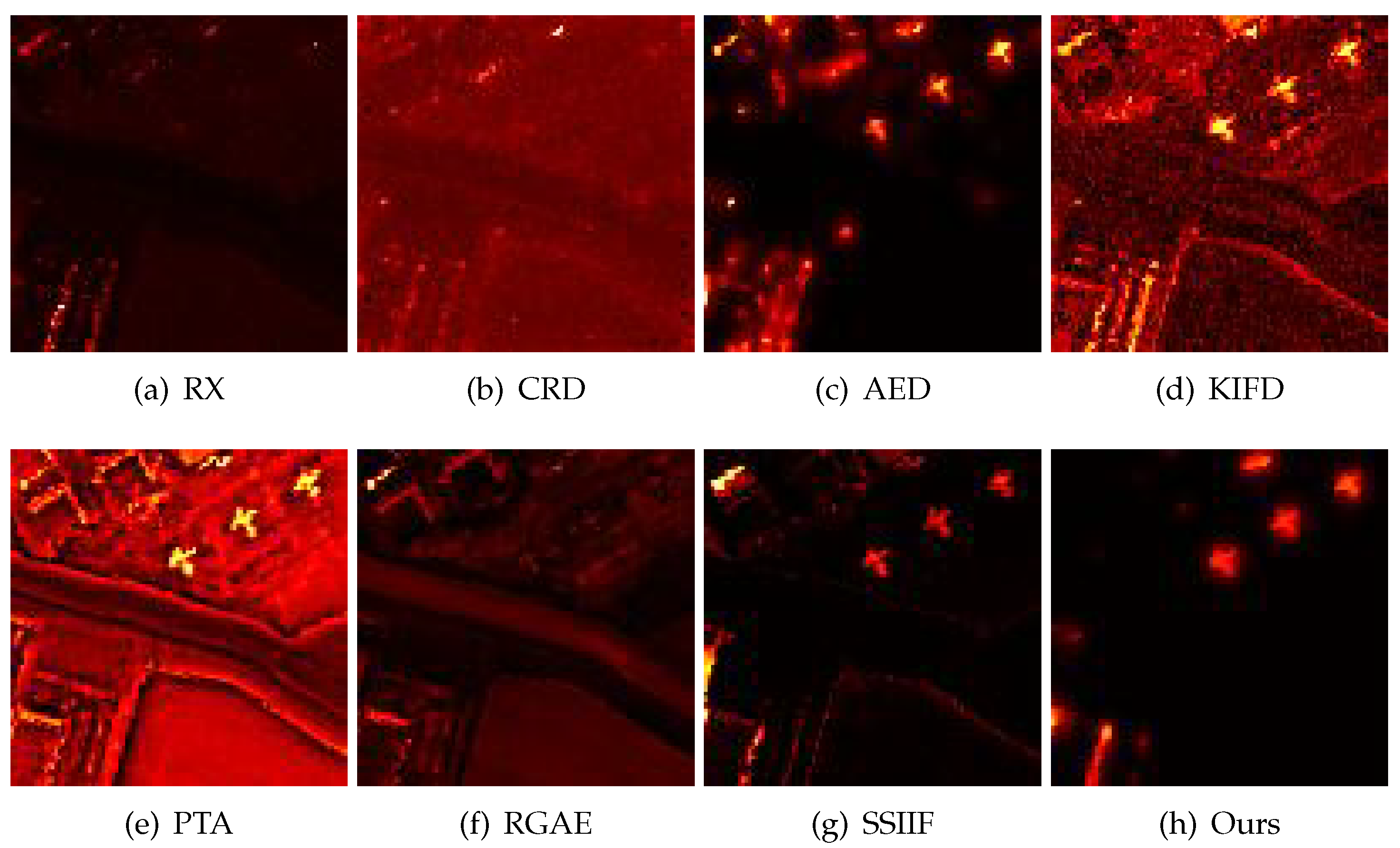

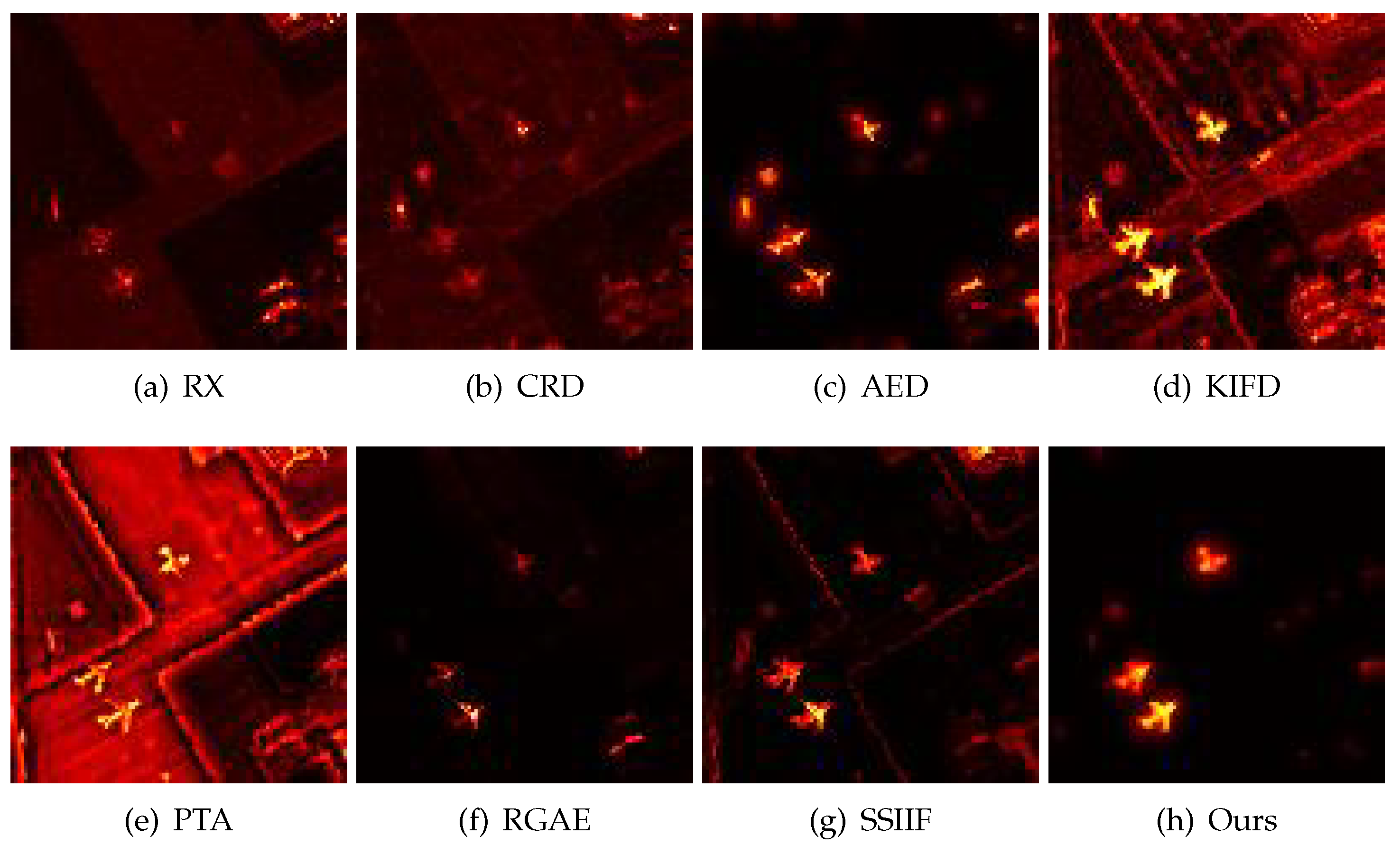

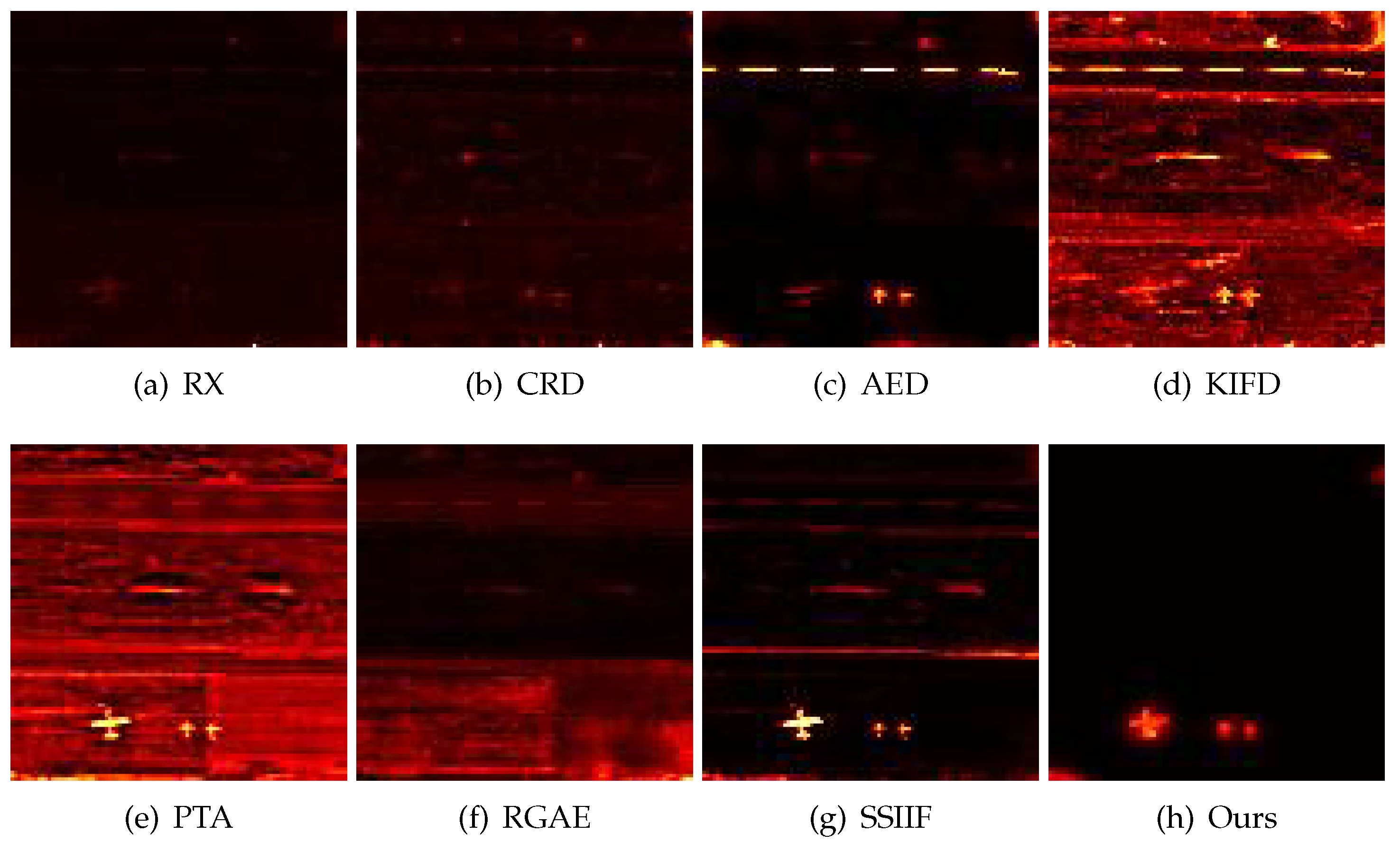

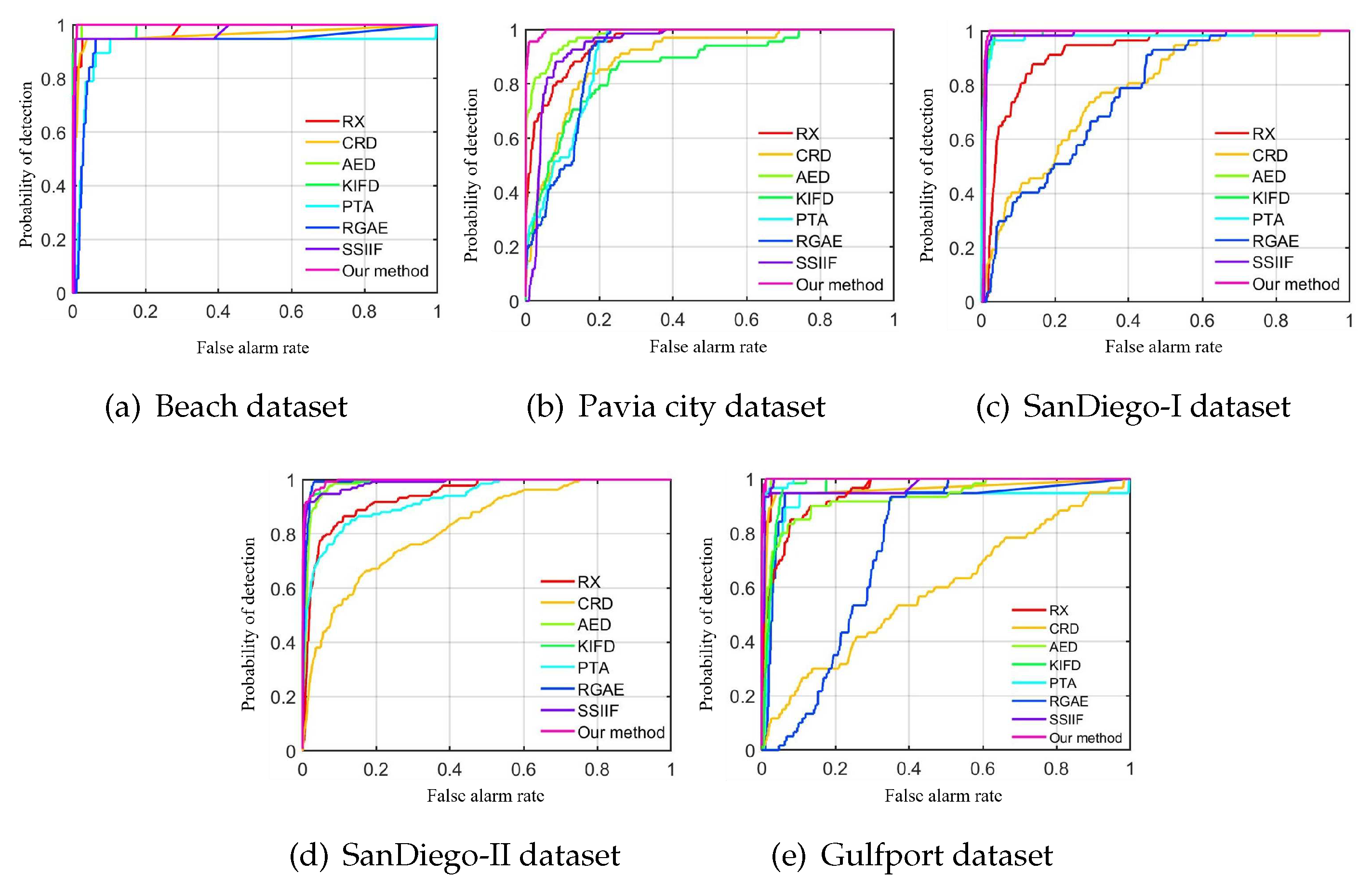

4.2. Detection Results

5. Discussion

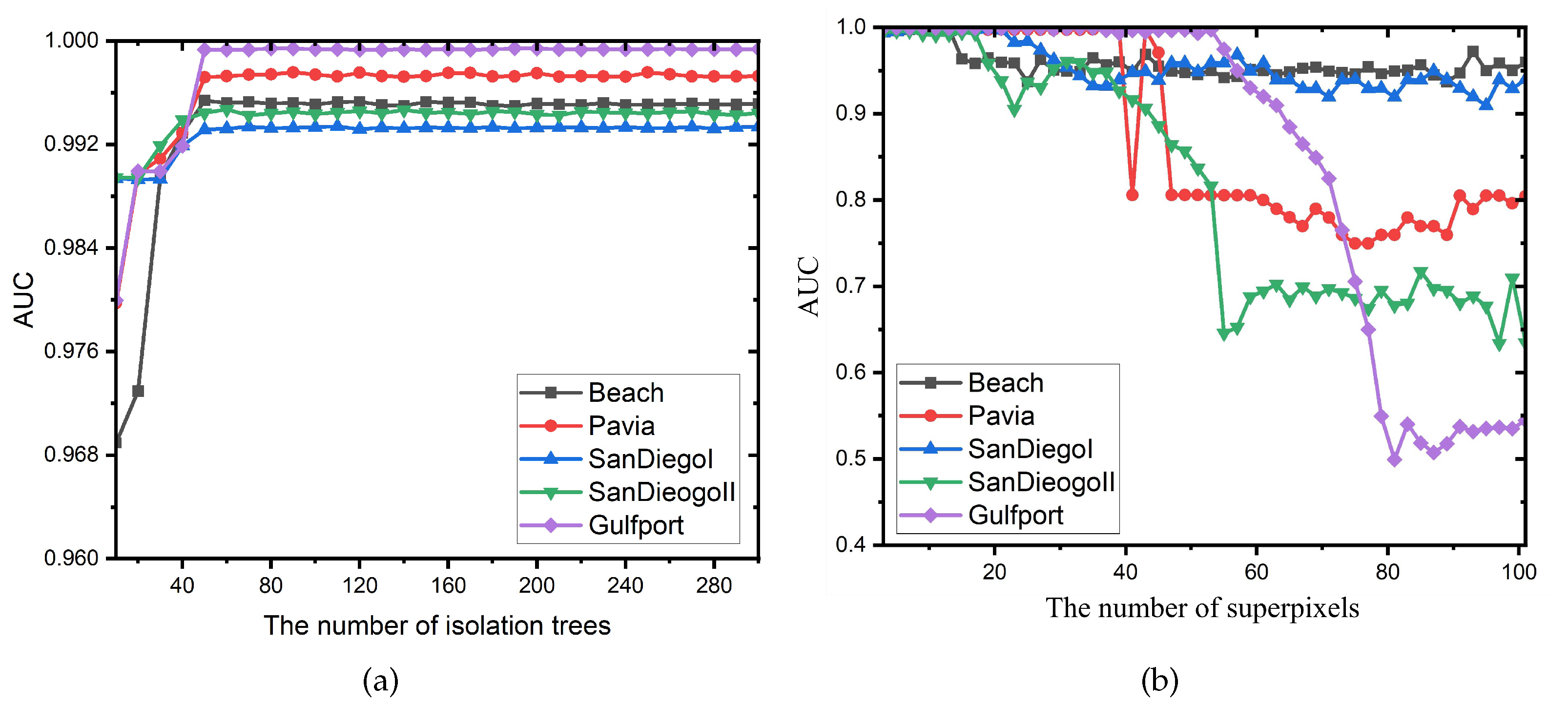

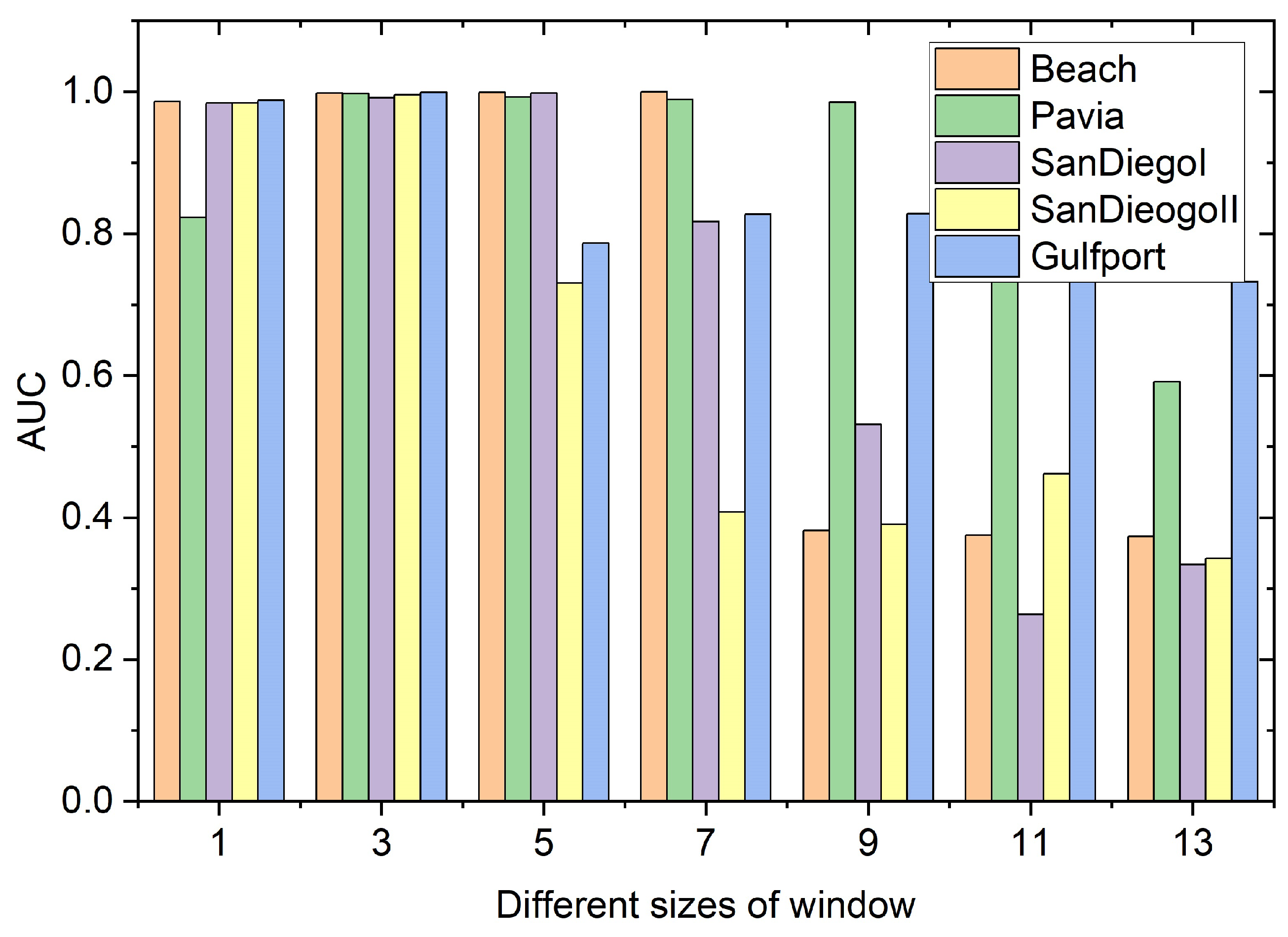

5.1. The Influence of Different Parameters

5.2. The Influence of Different Components

5.3. Computing Time

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Abbreviations

| SSIF | Spectral-spatial information fusion |

| HSI | Hyperspectral image |

| RX | Reed-Xiaoli |

| OSP | Orthogonal subspace projection |

| SR | Sparse representation |

| iForest | Isolation forest |

| DTRF | Domain transform recursive filtering |

| ERS | Entropy rate superpixel |

| AVIRIS | Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer |

| ROSIS | Reflective Optics System Imaging Spectrometer |

| CRD | Collaborative representation-based detector |

| AED | Attribute and edge-preserving filtering-based method |

| KIFD | Kernel isolation forest-based method |

| PTA | Prior-based tensor approximation |

| RGAE | Robust graph autoencoders |

References

- Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; Liu, S.; Wu, S. Attention-Aware Spectral Difference Representation for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Hu, S.; Kang, X.; Li, S. Shadow Removal of Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Images With Multiexposure Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Wang, Z.; Duan, P.; Wei, X. The Potential of Hyperspectral Image Classification for Oil Spill Mapping. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, T.; Tian, D.; Wang, H.; Yao, D.; Meng, L.; Shen, H. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection with Differential Attribute Profiles and Genetic Algorithms. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Lei, J.; Du, Q. Filter Pruning via Learned Representation Median in the Frequency Domain. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2023, 53, 3165–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Du, Q. Dual-Frequency Autoencoder for Anomaly Detection in Transformed Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Kang, X.; Li, S.; Ghamisi, P.; Benediktsson, J.A. Fusion of Multiple Edge-Preserving Operations for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 10336–10349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, P.; Mao, J.; Kang, X.; Fang, L.; Ghamisi, P. Contour Structural Profiles: An Edge-Aware Feature Extractor for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, G.; Yetkin, E.F.; Camps-Valls, G. A Scalable Unsupervised Feature Selection With Orthogonal Graph Representation for Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanlou, M.; Seydi, S.T. Hyperspectral change detection: An experimental comparative study. International journal of remote sensing 2018, 39, 7029–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Tao, R.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral change detection based on multiple morphological profiles. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eismann, M.T.; Meola, J.; Hardie, R.C. Hyperspectral change detection in the presenceof diurnal and seasonal variations. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2007, 46, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral anomaly detection: A survey. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 10, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, I.S.; Yu, X. Adaptive multiple-band CFAR detection of an optical pattern with unknown spectral distribution. IEEE transactions on acoustics, speech, and signal processing 1990, 38, 1760–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Der, S.Z.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Adaptive anomaly detection using subspace separation for hyperspectral imagery. Optical Engineering 2003, 42, 3342–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Nasrabadi, N. Kernel RX-algorithm: a nonlinear anomaly detector for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2005, 43, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, B.; Ran, Q.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Plaza, A. Weighted-RXD and Linear Filter-Based RXD: Improving Background Statistics Estimation for Anomaly Detection in Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 7, 2351–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Hou, Z.; Wu, F.; Du, Q.; Chen, Y. Anomaly detection for hyperspectral imagery based on the regularized subspace method and collaborative representation. Remote sensing 2019, 11, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, C.I.; Lee, L.C.; Wang, Y.; Xue, B.; Song, M.; Yu, C.; Li, S. Band subset selection for anomaly detection in hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 4887–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, E. Maximized subspace model for hyperspectral anomaly detection. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2012, 15, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.I.; Cao, H.; Song, M. Orthogonal Subspace Projection Target Detector for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 4915–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.I.; Cao, H.; Chen, S.; Shang, X.; Yu, C.; Song, M. Orthogonal Subspace Projection-Based Go-Decomposition Approach to Finding Low-Rank and Sparsity Matrices for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 2403–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Zhou, H.; Li, H.; Song, S.; Tan, W.; Song, J.; Gu, L. Hyperspectral anomaly detection by local joint subspace process and support vector machine. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2020, 41, 3798–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. A subspace selection-based discriminative forest method for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 4033–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, G. A hyperspectral imagery anomaly detection algorithm based on local three-dimensional orthogonal subspace projection. Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXI. SPIE, 2015, Vol. 9643, pp. 600–607.

- Matteoli, S.; Acito, N.; Diani, M.; Corsini, G. Subspace based non-parametric approach for hyperspectral anomaly detection in complex scenarios. Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XX. SPIE, 2014, Vol. 9244, pp. 245–253.

- Song, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.; Qian, K.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Z. Hyperspectral anomaly detection based on anomalous component extraction framework. Infrared Physics & Technology 2019, 96, 340–350. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Lai, Y.M.; Li, W. Low-rank and sparse matrix decomposition-based anomaly detection for hyperspectral imagery. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2014, 8, 083641–083641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.; Liu, D. Hyperspectral anomaly detection via dictionary construction-based low-rank representation and adaptive weighting. Remote sensing 2019, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wen, G. Hyperspectral anomaly detection via background estimation and adaptive weighted sparse representation. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Hyperspectral anomaly detection via a sparsity score estimation framework. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 3208–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, Q. Collaborative representation for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 53, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadar, M.; Ghassemian, H. Anomaly detection of hyperspectral imagery using modified collaborative representation. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2018, 15, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Du, Q. Discriminative reconstruction constrained generative adversarial network for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 4666–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Lei, J.; He, G.; Du, Q. Semisupervised Spectral Learning With Generative Adversarial Network for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 5224–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Lei, J.; Chang, C.I.; He, G. Spectral Adversarial Feature Learning for Anomaly Detection in Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 2352–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Huang, J. Exploiting embedding manifold of autoencoders for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 58, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, B. A stacked autoencoders-based adaptive subspace model for hyperspectral anomaly detection. Infrared Physics & Technology 2019, 96, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wu, G.; Du, Q. Transferred Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection in Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2017, 14, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, D. Hyperspectral image anomaly targets detection with online deep learning. 2018 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), 2018, pp. 1–6.

- Song, S.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Song, J. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection via Convolutional Neural Network and Low Rank With Density-Based Clustering. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2019, 12, 3637–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation-based anomaly detection. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data (TKDD) 2012, 6, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastal, E.S.; Oliveira, M.M. Domain transform for edge-aware image and video processing. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2011 papers; 2011; pp. 1–12.

- Liu, M.Y.; Tuzel, O.; Ramalingam, S.; Chellappa, R. Entropy-Rate Clustering: Cluster Analysis via Maximizing a Submodular Function Subject to a Matroid Constraint. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2014, 36, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Ju, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Hyperspetral anomaly detection incorporating spatial information. 2018 Eighth International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–5.

- Kang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Li, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection With Attribute and Edge-Preserving Filters. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 5600–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Duan, P.; Kang, X. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection With Kernel Isolation Forest. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, W.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Tao, R.; Du, Q. Prior-Based Tensor Approximation for Anomaly Detection in Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 33, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Ma, Y.; Mei, X.; Fan, F.; Huang, J.; Ma, J. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection With Robust Graph Autoencoders. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Aryal, S.; Ting, K.M.; Liu, Z.; He, B. Spectral–Spatial Anomaly Detection of Hyperspectral Data Based on Improved Isolation Forest. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIAO Mengyu, TAN Jinlin, L. Y.X.Q.W.S. Infrared Dim Small Flying Target Recognition Algorithm for Space-Based Surveillance. Chinese Space Science and Technology 2022, 42, 125. [Google Scholar]

| Datasets | RX | CRD | AED | KIFD | PTA | RGAE | SSIIF | Ours |

| Beach | 0.9807 | 0.9727 | 0.9974 | 0.9905 | 0.9184 | 0.9393 | 0.9672 | 0.9978 |

| Pavia | 0.9538 | 0.8941 | 0.9793 | 0.8742 | 0.9061 | 0.9042 | 0.9345 | 0.9972 |

| SanDiegoI | 0.9219 | 0.7826 | 0.9915 | 0.9934 | 0.9791 | 0.7914 | 0.9775 | 0.9949 |

| SanDiegoII | 0.9403 | 0.9687 | 0.9846 | 0.9931 | 0.9292 | 0.9929 | 0.9811 | 0.9956 |

| Gulfport | 0.9526 | 0.9618 | 0.9314 | 0.9683 | 0.9955 | 0.7583 | 0.9971 | 0.9990 |

| Datasets | Beach | Pavia | SanDiegoI | SanDiegoII | Gulfport |

| Spatial branch | 0.9866 | 0.9889 | 0.9844 | 0.9872 | 0.9967 |

| Spectral branch | 0.9790 | 0.9332 | 0.9833 | 0.9824 | 0.9918 |

| Ours | 0.9978 | 0.9972 | 0.9949 | 0.9956 | 0.9990 |

| Datasets | RX | CRD | AED | KIFD | PTA | RGAE | SSIIF | Ours |

| Beach | 0.24 | 280.39 | 28.04 | 52.08 | 51.74 | 311.74 | 47.41 | 36.18 |

| Pavia | 0.13 | 274.38 | 31.64 | 61.41 | 31.09 | 181.79 | 33.64 | 31.73 |

| SanDiegoI | 0.13 | 136.45 | 21.93 | 37.41 | 24.08 | 125.17 | 30.41 | 25.15 |

| SanDiegoII | 0.11 | 142.62 | 19.92 | 32.73 | 24.33 | 147.51 | 28.33 | 24.51 |

| Gulfport | 0.12 | 119.01 | 21.65 | 37.31 | 24.57 | 140.86 | 29.73 | 28.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).