1. Introduction

Software testing is an important component of the software development process, and it is a significant part of software engineering. It has the role to ensure that the software product fulfills the functional requirements, is free from defects and errors and is of good quality [

1,

2]. The quality of a software product relies on several parameters such as response time, performance, reliability, maintainability, correctness, testability, usability, and reusability, just to mention a few. Software testing is time consuming and even 40-50% of the project’s budget (in some cases even 80% [

3]) can be spent on this operation according to [

1,

2,

4]. The authors of [

2,

4] show that software testing is a not a “silver bullet” that can guarantee high quality of the software product, complete testing, i.e., discovering and fixing all errors is practically impossible, because the testing process cannot be exhaustive. The number of tests which can be performed is limited by several factors such as a too large input domain, too many possible paths, specifications difficult to test [

2], etc. Being an important activity in software development, the testing process should be carried out smoothly [

5] and the testing process should start in the early phase of the project to avoid the cost related to failed software afterwards [

3,

6].

A fundamental issue related to testing is the generation of good test cases [

6], which can find with high probability the errors and faults in a minimum amount of time and with minimum effort. The data obtained by testing is an indicator of the software reliability and quality, but the total absence of defects cannot be guaranteed. Both from the point of view of software development and testing the use of appropriate environments is also very important [

7]. These environments could be very different due to different operating systems, databases, network servers, application services, etc. An integrated management tool that allows the development of test scenarios and assignment of test cases, like the tool proposed in [

7], could be helpful for performing testing operations. In [

8] the authors underline the importance of frameworks for test execution that have improved the quality of software testing. Frameworks allow repeatable tests and make automated testing easier. Frameworks could also allow a standard way to perform the main parts of the testing process: setting the initial state, invoking the functionality under test, checking the results of the test, and performing any necessary cleanup.

Many of the testing techniques are focusing on testing the functional correctness, (debug testing), but performance issues are also very important in software testing, especially in some cases like web services, real time hardware systems or industrial systems and processes [

8]. In [

9] the authors discuss various issues related to software testing fundamentals and show that software testing is much more than error detection or debugging. In [

10] the authors show that after release of software products the main problems are related to performance degradation or providing the required throughput and system crashes and incorrect system response are usually secondary issues, the software being extensively tested before release from functional point of view. Performance testing involves issues like resource usage, throughput, stimulus response time, queue length, bandwidth requirements, CPU cycles, database access. Issues like scalability and capability to handle heavy workloads should also be considered.

Testing communication protocols and software components used by communication equipment raises several critical issues such as real-time processing constraints, timing and synchronization between intercommunicating modules and processes, strong interaction between the software and hardware components, the need of hardware platforms for testing complex protocols and signal processing, remote access to the platform where the tested software is running, the need to process a large amount of test generated data, just to mention a few. Testing of communication protocols used in specific applications requires specific test suites due to the complexity and requirements imposed to these protocols. Such an example is represented by testing of communication protocols used in wireless communications, which is one of the most challenging testing operations. In [

11] the authors present some conclusions obtained by testing in real life conditions transmission protocols used by mobile military networks. The main problems encountered during test operations were the timing constraints, test controllability, inconsistency detection and conflicting timers, just to mention a few.

Real life testing of communication protocols in general and transmission techniques in particular in wireless communication scenarios requires the use of dedicated hardware platforms adapted to the specific test scenarios. In [

12] the authors present a hardware platform including DSPs, FPGAs and SDR radio interfaces for prototyping and testing of complex radio transceivers, like OFDM transceivers. In [

13] the authors propose a mobile platform based on Universal Software Radio Peripheral (USRP) SDR devices for testing algorithms for radio transmitters and receivers and in [

14] the authors present the signal processing algorithms, and the design and testing methodologies related to the implementation of radio transceivers using the concept of SDR.

Developing communication protocols for radio transmission systems is not a trivial task. SDR technology and open-source development libraries like GNU Radio [

15] come in hand with several tools that ease the development of the wireless transmission systems PHY and MAC layer protocols. GNU Radio offers an extended library of signal processing modules necessary to develop, test, and evaluate especially PHY and MAC layer communication protocols, but support is provided also for network and transport layer protocols.

Testing, evaluating, and troubleshooting the PHY and MAC layer protocols in real life conditions is a very challenging task. With these in mind and because most of the traffic in real life scenarios is TCP/IP the paper proposes the architecture and implementation of a testing platform (testbed) that allows easy integration of the GNU Radio applications in TCP/IP stack and to perform end-to-end testing and troubleshooting. The developed testbed allows the execution of comprehensive dynamic testing of the communication protocols both in simulated and in real life conditions, when SDR interfaces are used for communication. The integration in the testing environment of the communication protocols under test is through Linux virtual network devices for which GNU Radio provides support. In addition, it makes the testing platform interoperable with other traffic generators and network analysis tools, which is very convenient for generating various types of user data flows.

The testing platform provides a mechanism to collect, store and analyze monitoring data that is optimized for handling of large amounts of real time data, situation characteristic to testing of physical layer protocols. The platform allows the execution of various testing operations, like functional testing, conformance testing and quality evaluation testing. The entire testbed setup and management is implemented in Python, making it suitable for integration in an automation testing framework. It also allows dynamic reconfiguration of the application under test through JSON objects, if the application implementation supports it.

2. Related work

The software testing process can be categorized in many ways. In [

2] the authors have identified the three main testing techniques:

Black Box Testing – it is based on the requirements specifications and there is no need to examine the code of the program. The tester knows only the set of inputs and predictable outputs.

White Box Testing – it mainly focuses on internal logic and structure of the code of the program. The tester has full knowledge of the program structure and with this technique it is possible to test every branch and decision in the program.

Grey Box Testing – it attempts, and generally succeeds, to combine the benefits of both black box and white box testing.

A more extended categorization of the software process can be found in [

3]. The testing process is a complex one with many phases and goals and due to these a relatively wide range of testing categories can be identified, as follows:

Acceptance Testing: it is performed to determine the acceptability of the system or software.

Ad-Hoc Testing: it is performed without planning or documentation and the goal is to find errors that were not detected by other types of testing.

Alpha and Beta Testing: Alpha testing is the testing done at development site after the acceptance testing while Beta testing is carried out in real test environment.

Automated Testing: automated tools are used to write and execute test cases.

Integration Testing: in this case the testing of the individual units is grouped as one and the interface between these units is tested.

Regression Testing: the test cases from the existing test suites are rerun to demonstrate that software changes have no unintended side-effects.

Stress Testing: this testing determines the robustness of software; the functioning of the software modules being forced beyond the limits of normal operation.

User Acceptance Testing: it is performed by the end users of the software. This testing happens in the final phase of the testing process.

Security Testing: it checks the ability of the software to prevent unauthorized access to the resources and data.

The categorization of the testing techniques is considered in many other studies. In [

16] besides the testing techniques categories mentioned above random testing, functional testing, control flow testing, data flow testing and mutation testing techniques are identified. In [

17] the authors introduce the terms of static and dynamic testing and analyze the use of the testing terminology in the case of several testing techniques.

The problem of generating good test suites is considered in many studies. In [

18] the authors show that a good test suite is the one that detects real faults. In [

7] the authors show that only a small number of representative use cases can be selected from a larger category of use cases. It is also shown that many errors occur at the boundaries of the input and output ranges and so test cases should focus on boundary conditions.

Testing specific software, systems or networks raises some specific issues originating from the specific requirements or functioning modes of these software or systems. In [

19] the authors consider testing the software for systems based on SOA (Service Oriented Architectures). The SOA based software could have system distribution, controllability and observability problems which makes testing more challenging. In [

20] the authors consider the case of testing the software of PLC (Programable Logic Controllers) in industrial environments. The paper proposes an approach to generate tests for error handling routines which ensures the reliability of the industrial process. In [

21] the authors consider the testing of large and complex network topologies with limited resources, and it is proposed an emulator which could run on a single virtual machine. The system was defined especially for research related to Software Defined Networks (SDN) and OpenFlow. The issues related to the topic of cloud testing are considered in [

22]. The authors present a systematic literature review related to the testing of cloud-based systems and the use of cloud technologies for testing purposes, topics which generated o lot of interest with the development of cloud technologies. In [

23] the authors consider the testing of software in systems with stringent reliability requirements. More exactly it is considered the testing of the digital control system software integrated in a nuclear plant safety software. To perform the testing operations in discussion the authors propose the building of a real platform, and a specific testing strategy is proposed. In [

24] the authors present a literature survey concerning the issues of testing embedded software. In embedded systems proper software testing is necessary especially in safety critical domains, like automotive or aviation. The testing should pay attention to issues such as limited memory, CPU usage, energy consumption, real-time processing, and the strong interaction between hardware and software. In [

25] the authors show that testing of embedded systems is difficult and challenging due to the need to ensure accuracy and timing in synchronous inter-process communications. The paper proposes a framework which allows the use of test suites that detect synchronization faults.

The importance of testing the communication protocols and the research issues raised by this process are considered in many papers [

11,

26,

27,

28,

29]. In [

26] it is shown that protocol testing can be designed based on the formal specifications which usually uses an extended finite state machine model, but both the control and the data flow of the protocol should be considered to detect the syntactic and semantic errors and to validate the protocol design. In [

27] the authors consider the testing of communication protocols designed according to the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model. The paper shows that successful testing should include efficient test case generation algorithms. In [

28] the authors show the importance of conformance testing in the context of rapid development of communication protocols which generate many implementations which might not be compatible. The authors show that the automation of the testing process is of interest, but complete automation is possible for simple models while in the case of complex models the automation is not straightforward and easy to do. In [

29] the authors present a survey concerning the testing of communication protocols. The paper underlines the importance of conformance testing, as implementations derived from the same protocol standard can be very different. An important problem remains the generation of good test suites and test sequences, especially in real life testing. The paper also shows that the number of states of a complex protocol implementation could be very large which makes exhaustive testing practically impossible. Due to these reasons several testing environments/frameworks have been implemented and reported in many studies. These environments/frameworks allow a more efficient, reliable, and flexible testing and evaluation of the communication protocols. The issues of test case generation in communication protocols testing are also considered in [

30]. Several testing methods are analyzed and experimented to evaluate some of the quality indicators, such as fault detection capability, applicability, complexity, testing time, etc. In [

31] the authors present a survey concerning the testing of control and data flows and of the time aspects of communication systems. The issue of generation of test suites which can detect the maximum number of errors at minimum cost is also considered.

Testing of more specific communication protocols is considered in [

32,

33,

34]. In [

32] the authors discuss the testing of communication protocols used between charging equipment and the battery management system of an electrical car. In this case the main issue is the consistency of communication between the two above-mentioned equipment. In [

33] is presented the testing of LIN protocol used to interconnect electronic systems of vehicles. The paper considers the issues related to the conformance testing of the LIN protocol, some of the conclusions being applicable also to other link layer protocol testing. In [

34] the authors consider the testing of industrial communication protocols, and the paper presents the evaluation of some of the most used industrial communication protocols from the software perspective.

Testing of communication protocols in challenging wireless communication systems was considered in several papers. In [

35] the authors consider the testing of military systems and applications in different communication scenarios which include both changing network conditions and data flow parameters. The paper proposes a test platform which allows automated testing of military systems and applications over real military radio equipment using reproducible test methodologies. In [

36] the authors propose a software testing method to evaluate the applicability, reliability and durability of various communication equipment used in maritime satellite communications.

In the context of testing communication protocols used in wireless communication networks the authors of [

37] present an open-access wireless testing platform which includes a large grid of ceiling mounted antennas connected to programable SDR devices working at frequencies lower than 6GHz. The system has computational power and hardware support for testing complex communication systems and protocols such as MIMO communication systems, cognitive radio, 5G cellular networks, IoT, etc. A multiple antenna evaluation and testing platform is also proposed in [

38]. To provide the required processing power and flexibility the platform includes FPGAs, DSPs, and control processors. The platform interfaces require high throughput since the evaluation of multiple antennas generates a high amount of real time data.

3. Results and Discussions

Two main issues are considered in this section, the performance of the monitoring messaging methods implemented in the developed testing platform and the evaluation of a complex transmission system implemented in GNU Radio. As presented in the previous sections the testing and evaluation of PHY layer communication protocols generates a large amount of monitoring messages that must be handled in real time. The size of the monitoring messages and the generation and handling of these messages are very important and will be evaluated in the developed platform. The testing of an example transmission system has as goal to show the capabilities of the proposed platform.

3.1. Evaluation of the Monitoring Messaging Methods

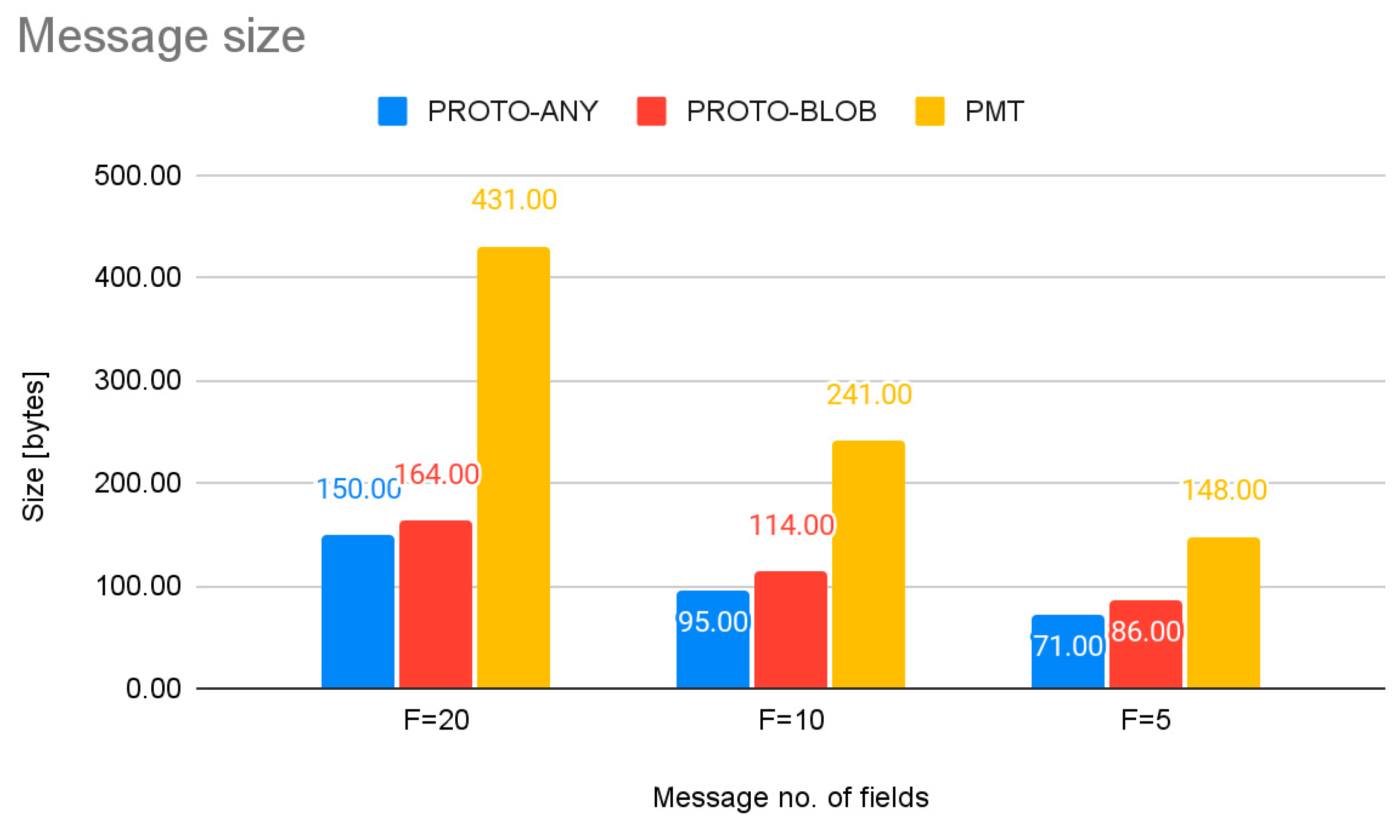

3.1.1. The Message Size

One expected outcome from using PROTO instead of PMT for monitoring messaging is the reduced size of the serialized message because it is not necessary to send the message fields names and the fields value types. It is analyzed the size of the messages for all three implementations of the messaging methods considered in section 2.3 for different numbers of fields in a message. The obtained results are presented in

Figure 15 and show the significant difference between the size of the messages generated with the PMT and PROTO methods, difference which increases with the number of fields of the message. The PROTO-ANY and the PROTO-BLOB generate messages with similar size no matter the number of fields of the message.

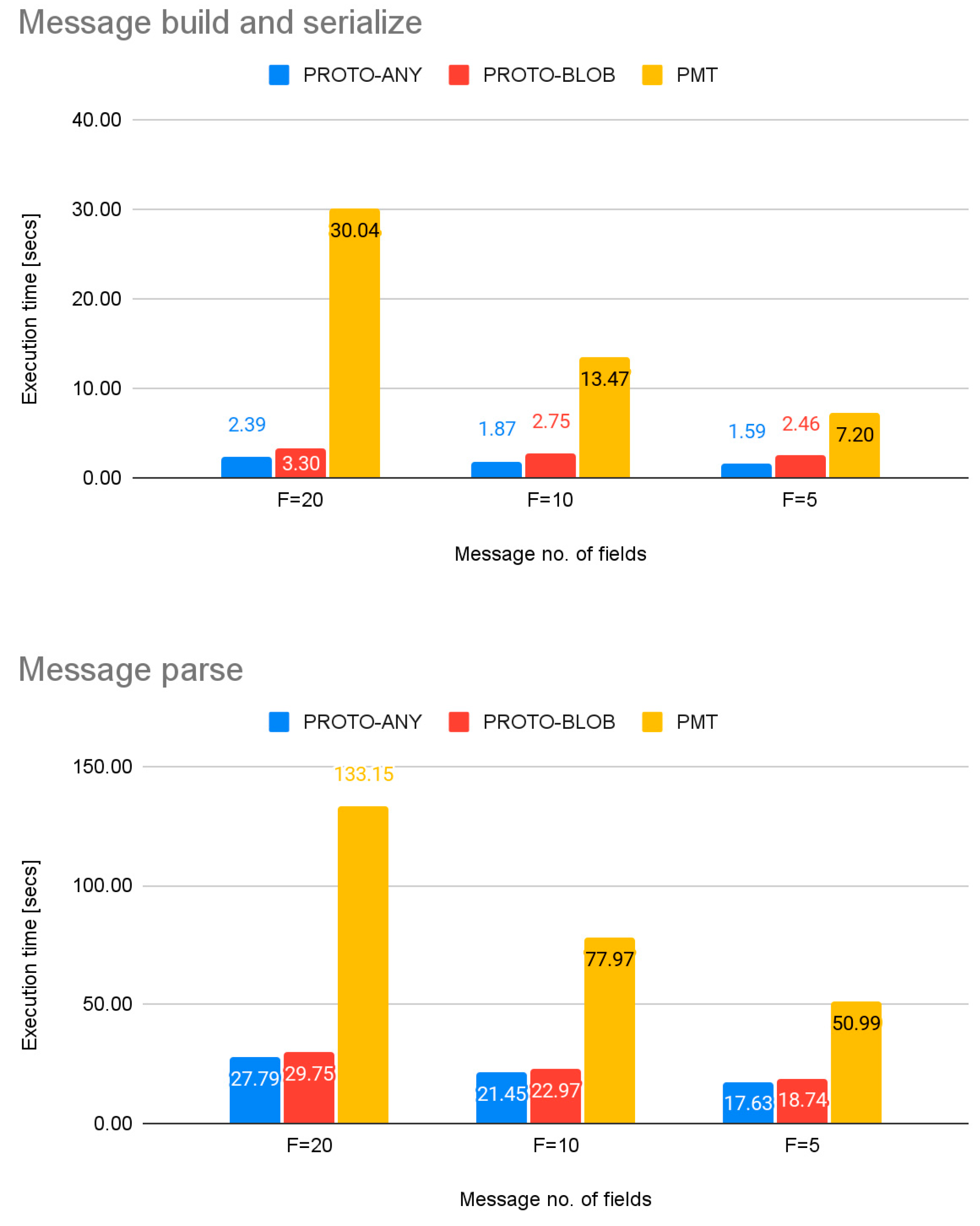

3.1.2. The Message Build and Parsing Times

To compare the messaging methods considered from the point of view of time necessary to build and parse the monitoring messages, it was measured the time necessary to perform the above-mentioned operations for 1000000 messages with different numbers of fields (NF). For both operation Python bindings were used. The machine used in testing was equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 PRO 4750U processor and 16GB of RAM and was running Ubuntu 22.04 in WSL2. The results presented in

Figure 16 show that both the time necessary for building and serializing the messages, at GNU Radio application side and for parsing the messages, at broker side, are significantly smaller in the case of the PROTO methods for all message sizes (number of fields). The magnitude of the time difference between the PROTO and PMT methods decreases with the number of fields of the message. The PROTO-ANY and the PROTO-BLOB methods exhibit similar message building and parsing times, the PROTO-ANY method requiring smaller times in both cases.

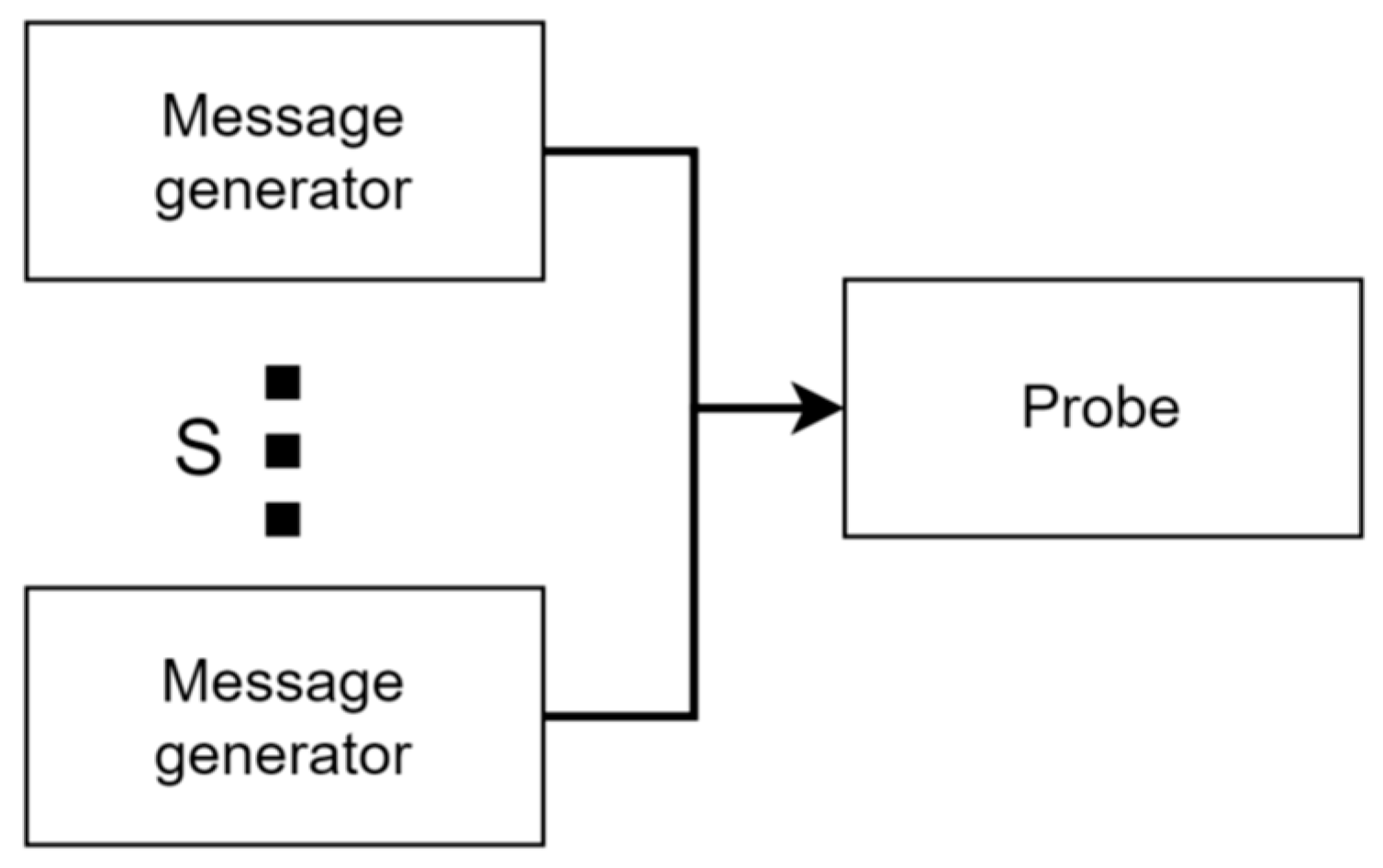

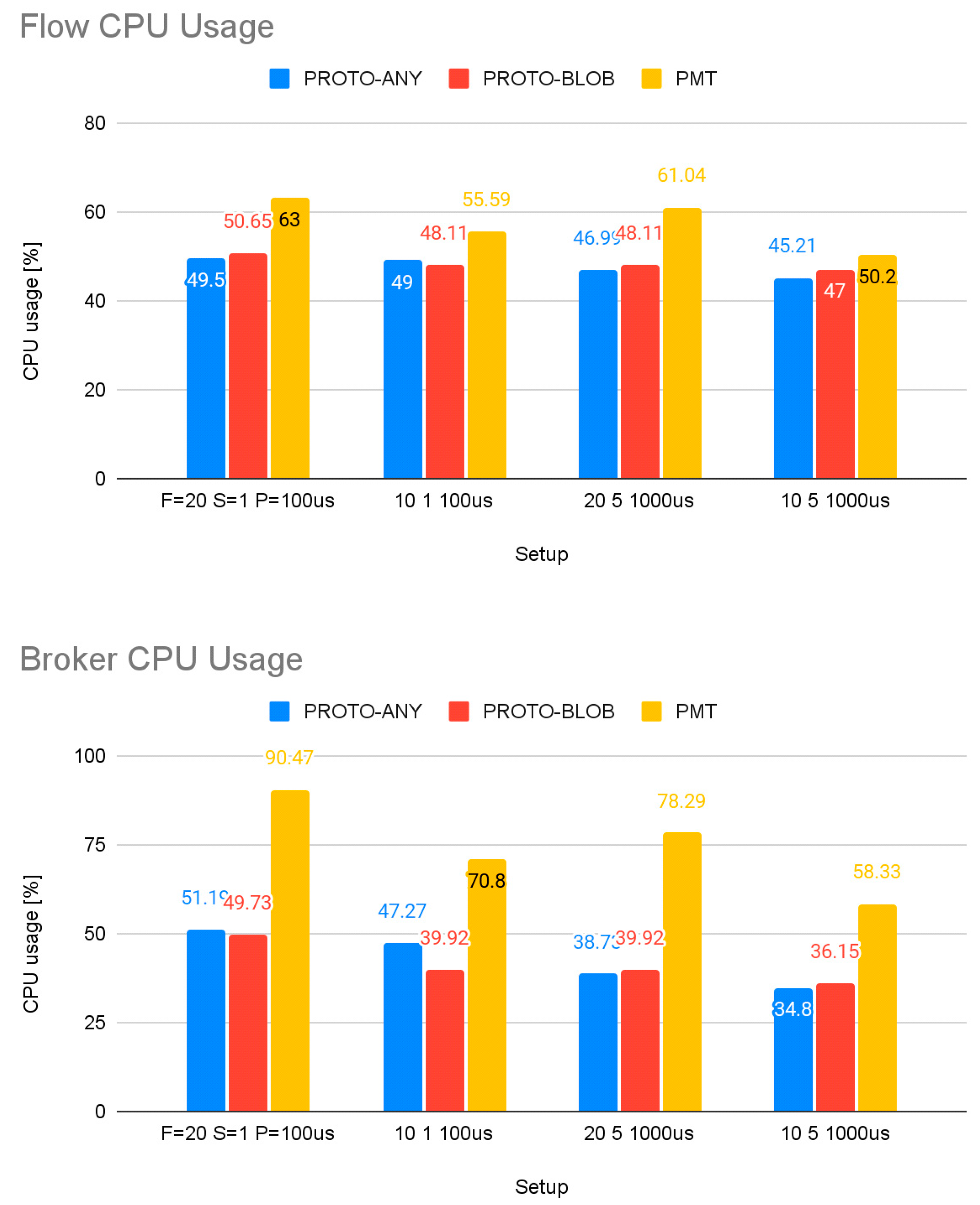

3.1.3. End-to-End Testing of the Messaging Methods

For end-to-end testing of the monitoring messaging methods, it was created a custom GNU Radio block that only generates messages with different sizes and at different rates (P) using the messaging methods described in

Section 2.3. By using this dedicated message generator, it was built a small GNU Radio process flow that contains S message generators and a single probe as shown in

Figure 17. The GNU Radio application was run in the networking environment presented in

Section 2.1 in different scenarios and the CPU usage was measured. The results obtained are presented in

Figure 18 and show that PROTO based messaging outperforms the pure PMT one, especially on the broker’s side, which is very important because the broker collects data from all probes. The gain in CPU usage at the GNU Radio application (process flow) is not as spectacular as the computing time gains showed before because the network operations are only slightly improved by the smaller size of the PROTO message.

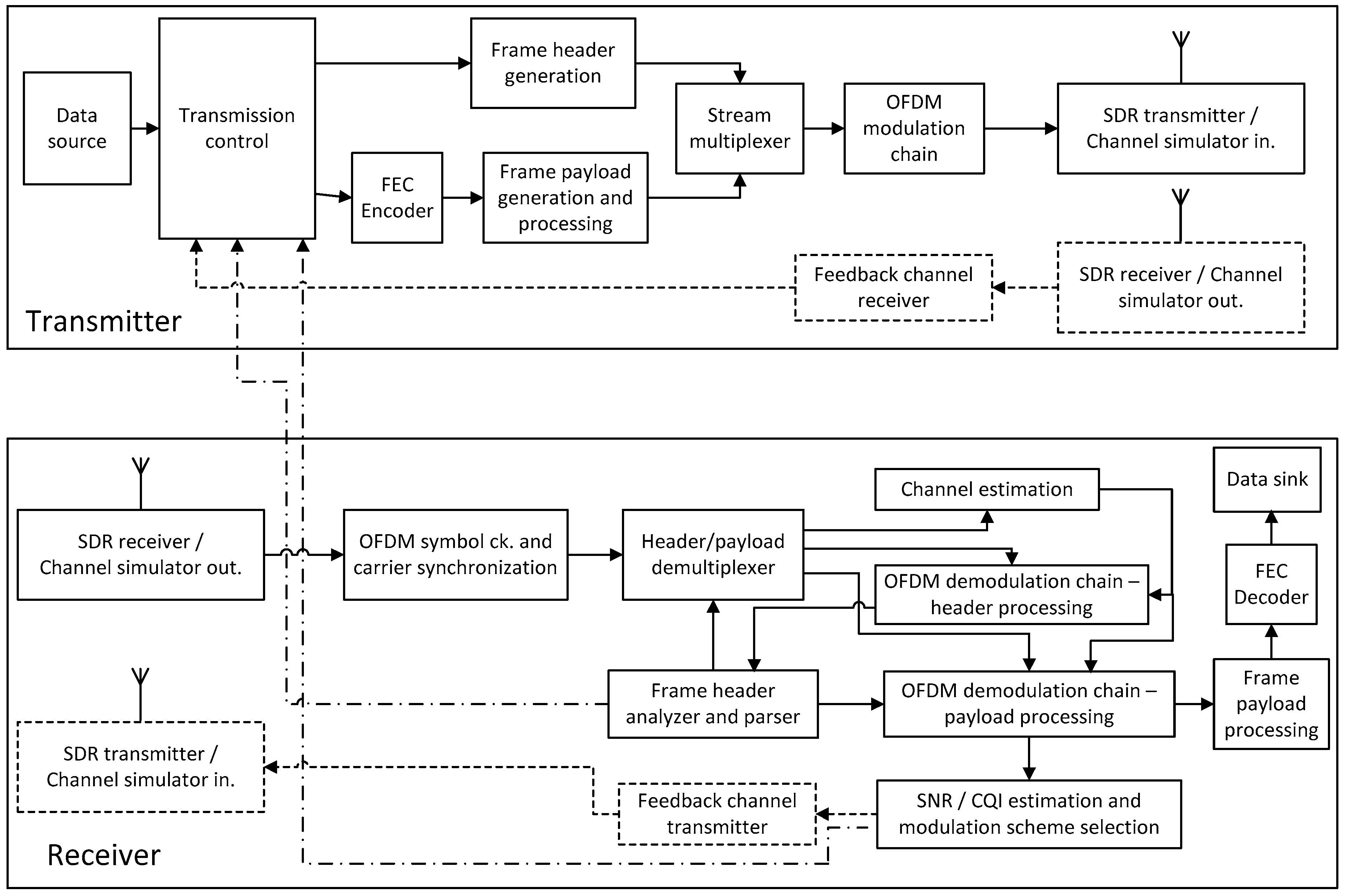

3.2. System Under Test

To check the functioning of the developed testing platform and to demonstrate its utility in testing complex communication protocols, it is used an OFDM transmission system, the transceivers of the system having adaptive modulation and coding capabilities. Such an OFDM system is complex enough [

12] to fully demonstrate the capabilities of the test platform. More exactly two OFDM systems were tested, one of them implements a simplex transmission and a revers channel is used to convey the channel state information from the receiver to the transmitter, while the second one is a full duplex transmission system, the channel state information acquired by each receiver being multiplexed with the data flows to be sent to the corresponding transmitter. A simplified schematic of the simplex OFDM transmission system is given in

Figure 19. More details about the architecture of this system with adaptive modulations, but without adaptive coding, can be found in [

57] and the implementation of the OFDM modem under test is available in [

52].

The tested/evaluated OFDM transmission system includes several complex signal processing blocks, such as the OFDM clock and carrier synchronization block, the channel transfer function estimator, the OFDM equalizer, the FEC encoder and decoder (the FEC codes used are LDPC codes), the SNR estimation block, the transmission control block, the framing block. To perform a comprehensive dynamic white box testing of these signal processing blocks a large amount of data is necessary to be acquired and analyzed. This requires a fast and effective monitoring system capable of coping with a large amount of data and with real-time signal acquisition and handling. The necessity to acquire in real time a large amount of monitoring data is a characteristic of any platform used for testing and evaluation of complex PHY layer algorithms [

38].

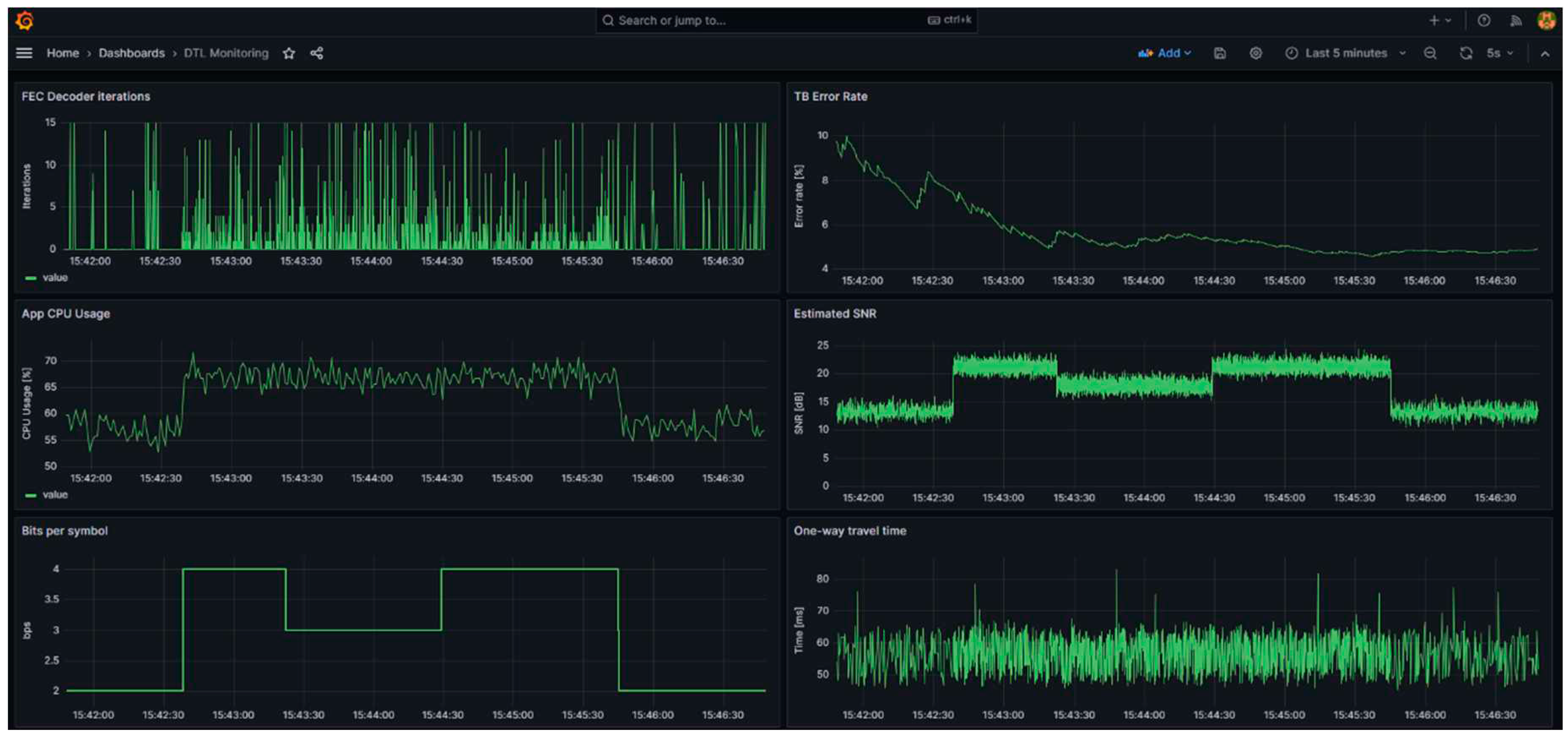

3.2.1. Evaluation of the System Under Test

In the panels of

Figure 20 is presented the evolution in time of some of the important parameters of the OFDM transmission system under test. More exactly in

Figure 20 is presented the evolution time of the following parameters: number of iterations of the LDPC decoder, transport block/frame error rate, application CPU usage, estimated SNR, bits/symbol of the used modulation (i.e., the used modulation scheme), one-way travel time of the IP packets loaded in the transport blocks. Should be mentioned that the goal of this paper is not to perform a detailed testing and evaluation of an OFDM transmission system with adaptive coded modulation and the transmission system depicted in

Figure 20 is used only to show the capabilities of the developed testing platform. The parameters presented in

Figure 20 are evaluated frame by frame or packet by packet, but other parameters like the equalization coefficients and the decision error of the QAM symbols composing the OFDM symbol, just to mention a few parameters, should be evaluated at each OFDM symbol, which will generate a larger amount of monitoring data. The traces representing the variation in time of the considered parameters were generated using the Grafana utility, which was also used to query the database storing the values of the considered parameters together with time stamps.

5. Conclusions

The goal of the current paper was to develop a software testbed for evaluating PHY and MAC layer communication protocols developed with GNU Radio that is easy to use, interoperable with any traffic generator and allows collection and analysis of PHY layer monitoring data. To achieve this the paper describes how to set up a network environment that can be used in End-to-End tests of both, simulation, and real channel applications. The network environments are isolated, making their management simpler and allowing multiple environments on the same machine – which is important when multiple tests are executed at the same time on powerful servers. The setup and management are implemented in Python to ease the integration in testing automation. It uses the Linux kernel’s virtual network devices (i.e., tun/tap) to feed test traffic in the applications (i.e., transmission chain for SDR) to make it compatible with any network traffic generator.

To collect monitoring data from the physical layer the paper proposes and analyzes several methods: one that uses only GNU Radio built in Polymorphic Types (PMT) and two that employs Protocol Buffer library to enhance the performance of the message’s generation, serialization, and parsing processes. The PMT method has the advantage of being very versatile and easy to use, being built-in GNU Radio runtime and not requiring any schema definition.

Since testing of communication protocols generates a large amount of monitoring data which should be acquired in real time, efficient and fast messaging methods are needed. The performance of the proposed Protocol Buffers based methods was analyzed in terms of computation time of the main components, CPU usage in End-To-End tests and message size. It was shown that in all scenarios considered the Protocol Buffers based methods outperform the PMT method.

The paper considers the entire evaluation ecosystem, from the PHY layer monitoring to data storage and visualization and demonstrates how to use it for white box testing of wireless transmission protocols developed with GNU Radio. To show the capabilities of the developed testbed was used a complex OFDM duplex transmission system with adaptive coded modulations.

The issue of automation of the testing process is not explicitly considered by the paper, but the proposed framework has the potential to allow a relatively easy integration of such functionality. Custom traffic generators can be built in accordance with the test suite and the environments and testbed management is implemented in Python making it easy to expose to automation testing frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and Z.P.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S.; validation, Z.P., and M.S.; formal analysis, Z.P.; investigation, M.S.; resources, Z.P.; data curation, Z.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.P.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, Z.P.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, Z.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Okenzie, F.; Odun-Ayo, I.; Bogle, S. A Critical Analysis of Software Testing Tools. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2019, 1378, 1378–042030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A. A Comparative Study of Software Testing Techniques. Int. J. of Computer Science and Mobile Computing 2014, 3, 579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.E.; Khan, F. Importance of Software Testing in Software Development Life Cycle. Int. J. of Computer Science Issues 2014, 11, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, M.; El-Haggar, N.; Sami, M.A. Review of Scripting Techniques Used in Automated Software Testing. Int. J. of Adv. Computer Science and Applic. 2014, 5, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Pushparaj, T. A Study on Variations of Bottlenecks in Software Testing. Int. J. of Computer Sciences and Engineering 2014, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, R.K.; Singh, I. Latest Research and Development on Software Testing Techniques and Tools. Int. J. of Current Eng. and Techn. 2014, 4, 2368–2372. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Research on Software Development and Test Environment Automation based on Android Platform. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Mechatronics Engineering and Information Technology (ICMEIT 2019), Dalian, China, 29-30 March 2019; pp. 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orso, A.; Rothermel, G. Software testing: A research travelogue (2000-2014). In Proceedings of the Future of Software Engineering (FOSE 2014), Hyderabad, India, 31 May-7 June 2014; pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyat, J.; Dhingra, S.; Goyal, V.; Malik, V. Software Testing Fundamentals: A Study. Int. J. of Latest Trends in Eng. And Techn. 2014, 3, 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- Weyuker, E.J.; Vokolos, F.I. Experience with Performance Testing of Software Systems: Issues, an Approach, and Case Study. IEEE Trans. on Software Eng. 2000, 26, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, M.U.; Fecko, M.A.; Duale, A.Y.; Amer, P.D.; Sethi, A.S. Experience in Developing and Testing Network Protocol Software Using FDTs. Inf. and Soft. Tech. 2003, 45, 815–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, C.; Melvin, S.; Ilow, J. Rapid Prototyping Hardware Platforms for the Development and Testing of OFDM Based Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Communication Networks and Services Research Conference (CNSR’05), Halifax, NS, Canada, 16-18 May 2005; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, O.; Abraham, S.; El-Tawab, S. A Mobile Platform Using Software Defined Radios for Wireless Communication Systems Experimentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, Ohio, USA, 24-28 June 2017; 18113. [Google Scholar]

- Serkin, F.B.; Vazhenin, N.A. USRP Platform for Communication Systems Research. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON 2013), Cartagena, Spain, 23-27 June 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GNURadio The Free & Open Software Radio Ecosystem. Available online: https://www.gnuradio.org (accessed on 20 Nov. 2023).

- Kaur, M.; Singh, R. A Review of Software Testing Techniques. Int. J. of Electronic and Electrical Eng. 2014, 7, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Roggio, R.F.; Gordon, J.S.; Comer, J.R.; Khan, F. Taxonomy of Common Software Testing Terminology: Framework for Key Software Engineering Testing Concepts. J. of Inf. Systems Applied Research 2014, 7, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Just, R.; Jalali, D.; Inozemtseva, L.; Ernst, M.D.; Holmes, R.; Fraser, G. Are Mutants a Valid Substitute for Real Faults in Software Testing? In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering (FSE 2014), Hong Kong, China, 16-21 Nov. 2014; pp. 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Design and Implementation of Software Testing Platform for SOA-Based System. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), Chengdu, China, 23-26 April 2021; pp. 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosch, S.; Tikhonov, D.; Schutz, D.; Vogel-Heuser, B. Model-Based Testing of PLC Software: Test of Plants’ Reliability by Using Fault Injection on Component Level. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 3509–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Singh, J.; Ghumman, N.S. Mininet as Software Defined Networking Testing Platform. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communication, Computing & Systems (ICCCS 2014), Ferozepur, Punjab, India, 8-9 Aug. 2014; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, A.; De Angelis, G.; Gallego, M.; Garcia, B.; Gortazar, F.; Lonetti, F.; Marchetti, E. A Systematic Review on Cloud Testing. ACM Computing Surveys 2019, 52, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Liu, W.; Bai T.; Ye W-p.; Shi J. An Automation Test Strategy Based on Real Platform for Digital Control System Software in Nuclear Power Plant. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 580-587. [CrossRef]

- Garousi, V.; Felderer, M.; Karapicak, C.M.; Yilmaz, U. Testing Embedded Software: A Survey of the Literature. Information and Software Technology 2018, 104, 14–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, S.; Khan, S.A.; Hassan, A.; Fatima, U. A Novel Framework for Testing High-Speed Serial Interfaces in Multiprocessor Based Real-Time Embedded System. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikaya, B.; Bochmann, G.V.; Cerny, E. A Test Design Methodology for Protocol Testing. IEEE Trans. On Soft. Eng. 1987, SE-13, 518-531. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hutchison, D. Protocol Testing Techniques. Computer Communications 1987, 10, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ssouli, R.; Saleh, K.; Aboulhamid, E.; Bediaga, A.; En-Nouaary, A; Bourhfir, C. Test Development for Communication Protocols: Towards Automation. Computer Networks 1999, 31, 1835-1872. [CrossRef]

- Lai, R. A Survey of Communication Protocol Testing. J. of Syst. and Soft. 2002, 62, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorofeeva, R.; El-Fakih, K.; Maag, S.; Cavalli, A.R.; Yevtushenko, N. FSM-Based Conformance Testing Methods: A Survey Annotated with Experimental Evaluation. Inf. and Soft. Tech. 2010, 52, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dssouli, R.; Khoumsi, A.; Elqortobi, M.; Bentahar, J. Chapter Three-Testing the Control-Flow, Data-Flow, and Time Aspects of Communication Systems: A Survey. Advances in Computers 2017, 107, 95–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Tang, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Test Method of Communication Protocol of Standard Group Components of Electric Vehicle Charging Equipment. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2021, 2066, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrenz, W. Communication Protocol Conformance Testing - Example LIN. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety, Shanghai, China, 13-15 Dec. 2006; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, E.; Sastoque-Pinilla, L.; Lopez-Novoa, U.; Bediaga, I.; López de Lacalle, N. Assessing Industrial Communication Protocols to Bridge the Gap between Machine Tools and Software Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettore, P.H.L.; Loevenich, J.; Lopes, R.R.F. TNT: A Tactical Network Test Platform to Evaluate Military Systems Over Ever-Changing Scenarios. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 100939–100954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L. Software Testing Method Based Mobile Communication Equipment of Maritime Satellite. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 234, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertizzolo, L.; Bonati, L.; Demirors, E.; Al-shawabka, A.; D’Oro, A.; Restuccia, F; Melodia, T. Arena: A 64-Antenna SDR-Based Ceiling Grid Testing Platform for sub-6 GHz 5G-and-Beyond Radio Spectrum Research. Computer Networks 2020, 181, 107436. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Hu, L. General Multiple Antenna Evaluation Platform. In Proceedings of the 2005 2nd Asia Pacific Conference on Mobile Technology, Applications and Systems, Guangzhou, China, 15-17 Nov. 2005; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun/Tap interface tutorial. Available online: https://backreference.org/2010/03/26/tuntap-interface-tutorial/index.html (accessed on 22 Nov. 2023).

- Introduction to Linux interfaces for virtual networking. Available online: https://developers.redhat.com/blog/2018/10/22/introduction-to-linux-interfaces-for-virtual-networking# (accessed on 24 Nov. 2023).

- Pyroute2 netlink library. Available online: https://docs.pyroute2.org/ (accessed on 30 Nov. 2023).

- Python-iptables. Available online: https://python-iptables.readthedocs.io/en/latest/intro.html (accessed on 30 Nov. 2023).

- Testbed for GNU Radio applications. Available online: https://github.com/mihaipstef/dtl-testbed (accessed on 12 Dec. 2023).

- Scapy. Available online: https://scapy.net/ (accessed on 24 Nov. 2023).

- MongoDB Documentation. Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/docs/ (accessed on 24 Nov. 2023).

- Eyada, M.M.; Saber, W.; El Genigy, M.M.; Amer, F. Performance Evaluation of IoT Data Management Using MongoDB Versus MySQL Databases in Different Cloud Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110656–110668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafana documentation. Available online: https://grafana.com/docs/grafana/latest/ (accessed on 24 Nov. 2023).

- Polymorphic Types (PMTs). Available online: https://wiki.gnuradio.org/index.php/Polymorphic_Types_ (accessed on 27 Nov. 2023).

- Protocol Buffers Documentation. Available online: https://protobuf.dev/overview/ (accessed on 27 Nov. 2023).

- Introducing JSON. Available online: https://www.json.org/json-en.html (accessed on 27 Nov. 2023).

- OutOfTreeModules. Available online: https://wiki.gnuradio.org/index.php/OutOfTreeModules (accessed on 28 Nov. 2023).

- Adaptive OFDM modem and monitoring library in GNU Radio. Available online: https://github.com/mihaipstef/gr-dtl (accessed on 12 Dec. 2023).

- ZeroMQ. An open-source universal messaging library. Available online: https://zeromq.org/ (accessed on 28 Nov. 2023).

- What is Pub/Sub? Available online:. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/pubsub/docs/overview (accessed on 28 Nov. 2023).

- Buffer Protocol. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/buffer.html (accessed on 29 Nov. 2023).

- STL containers. Available online: https://pybind11.readthedocs.io/en/stable/advanced/cast/stl.html (accessed on 29 Nov. 2023).

- Polgar, Z.A.; Stef, M. OFDM Transceiver with Adaptive Modulation Implemented in GNU Radio. In Proceedings of the 2023 46th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 12-14 July 2023; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

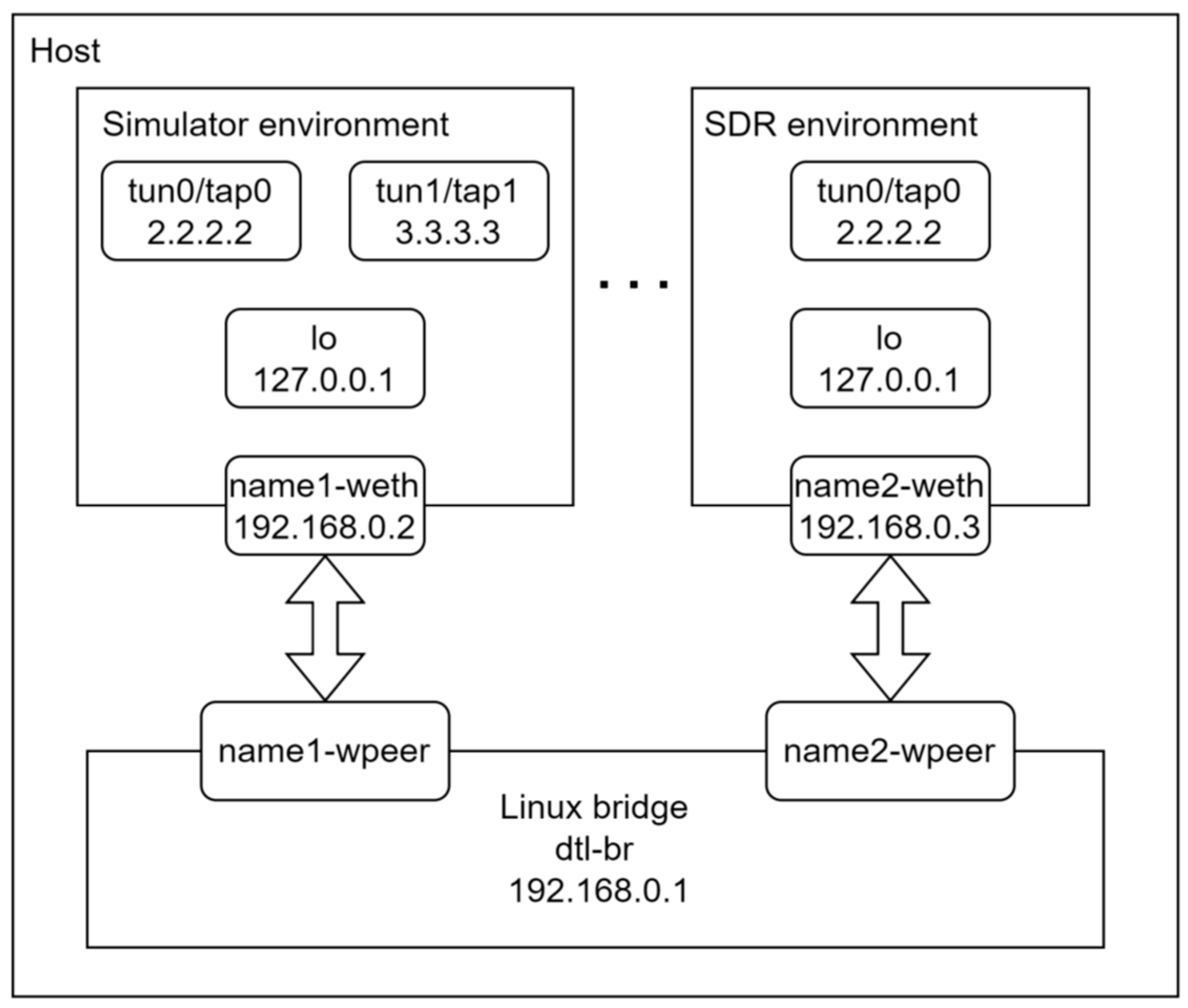

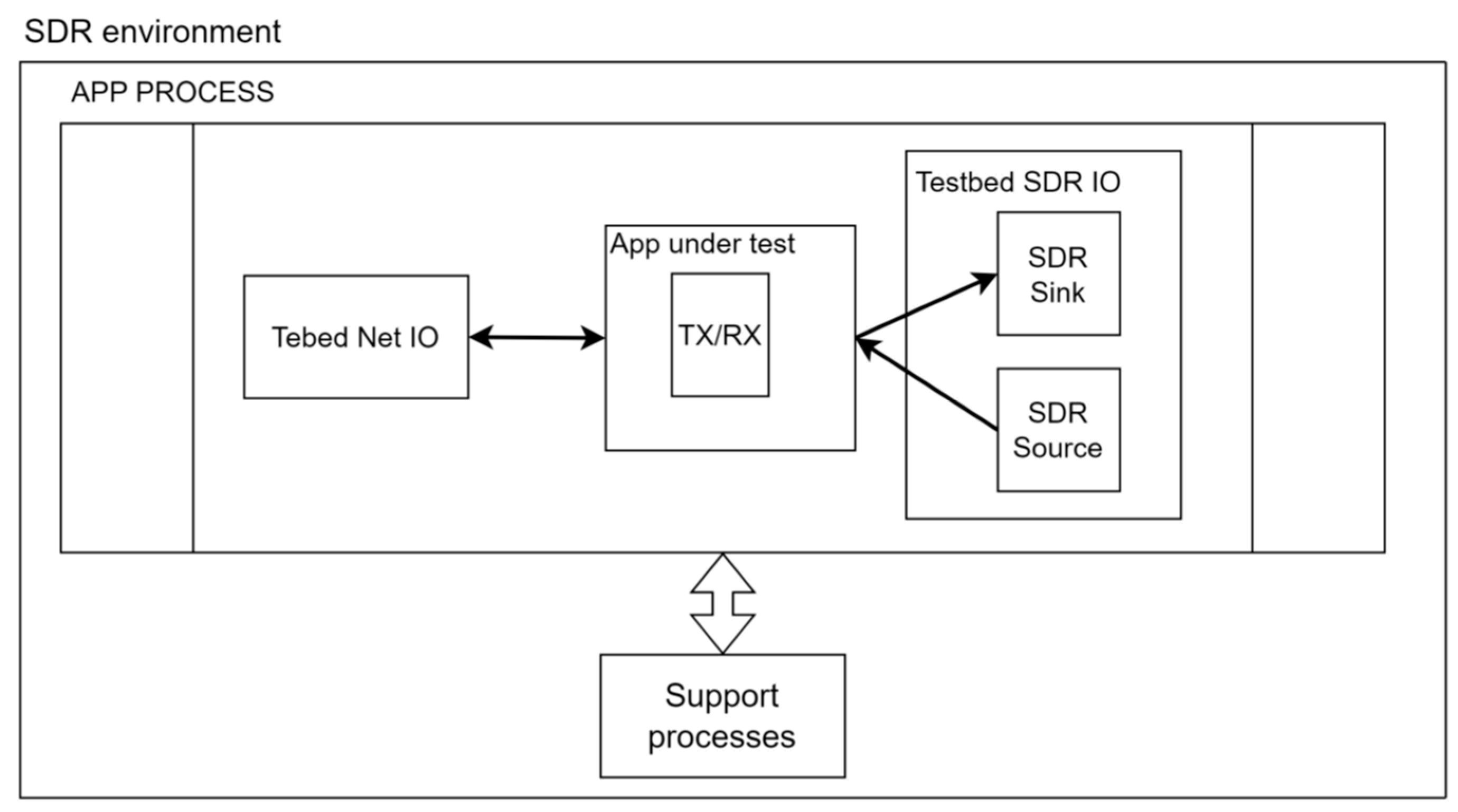

Figure 1.

The schematic of the environment encapsulating the application under test.

Figure 1.

The schematic of the environment encapsulating the application under test.

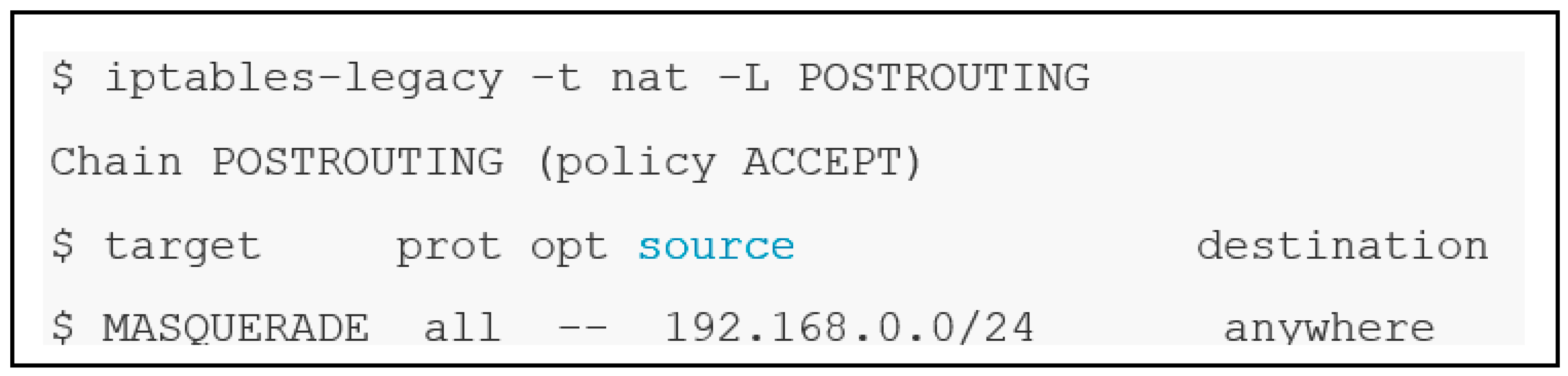

Figure 2.

Applying netfilter rules for NAT at the gateway.

Figure 2.

Applying netfilter rules for NAT at the gateway.

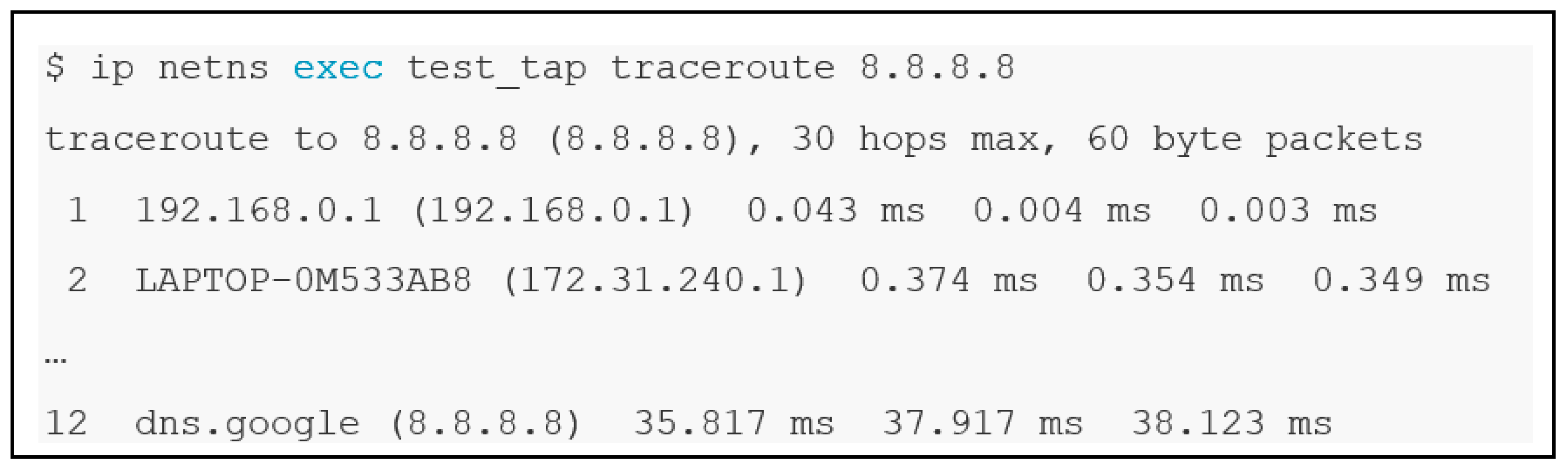

Figure 3.

Executing the traceroute command in the environment to a public IP address.

Figure 3.

Executing the traceroute command in the environment to a public IP address.

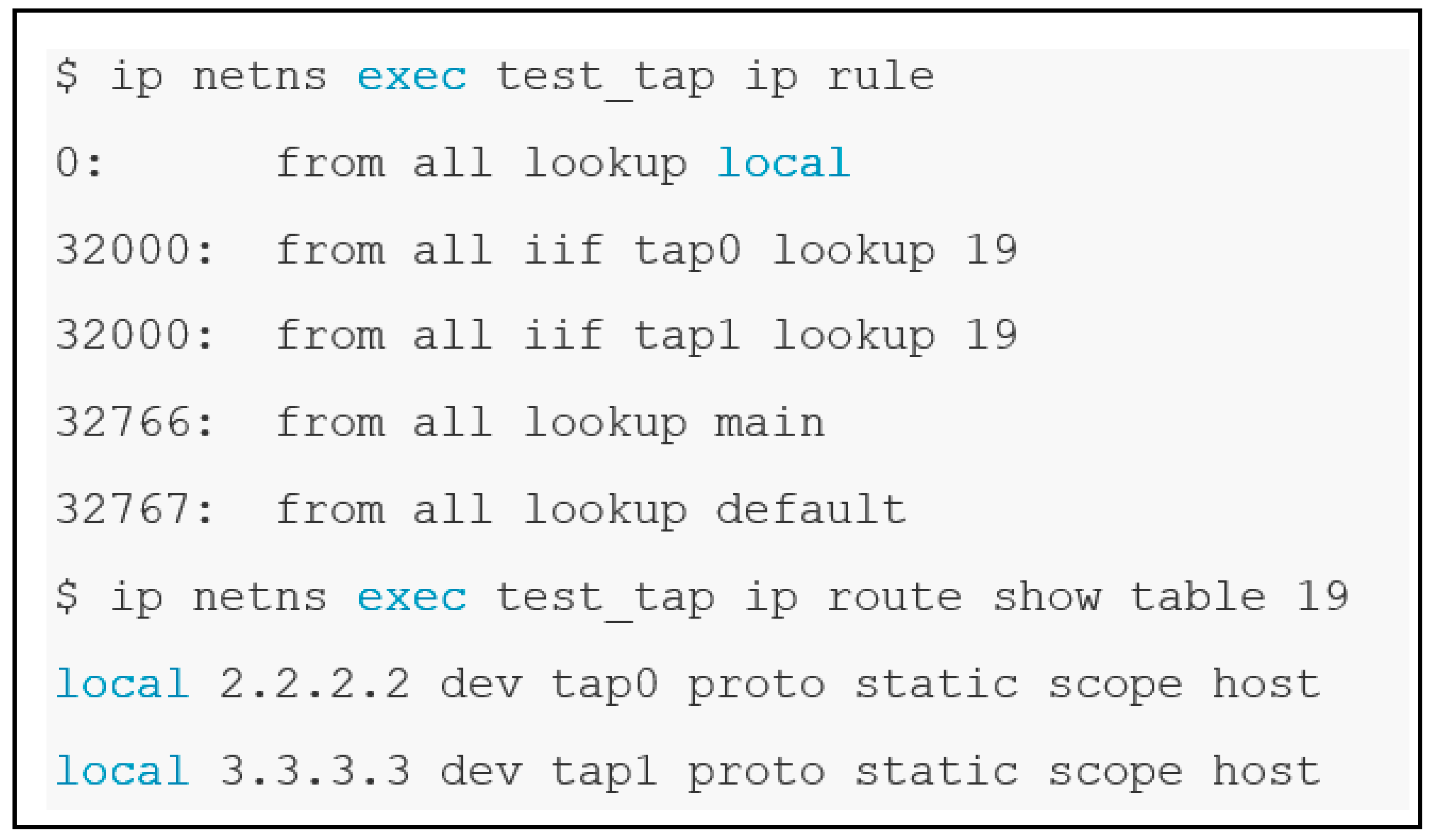

Figure 4.

Custom “local” routing table for ingress traffic.

Figure 4.

Custom “local” routing table for ingress traffic.

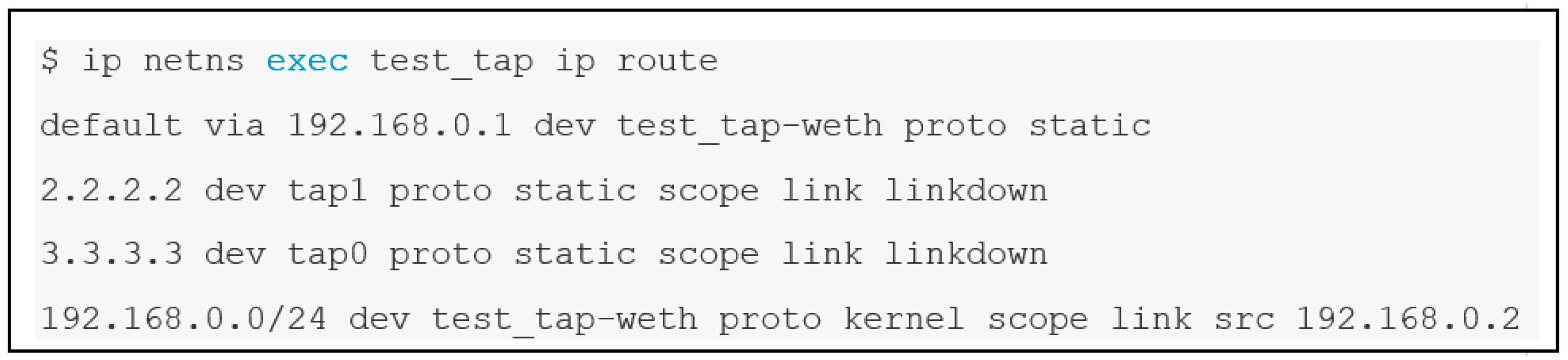

Figure 5.

Main routing table of the environment.

Figure 5.

Main routing table of the environment.

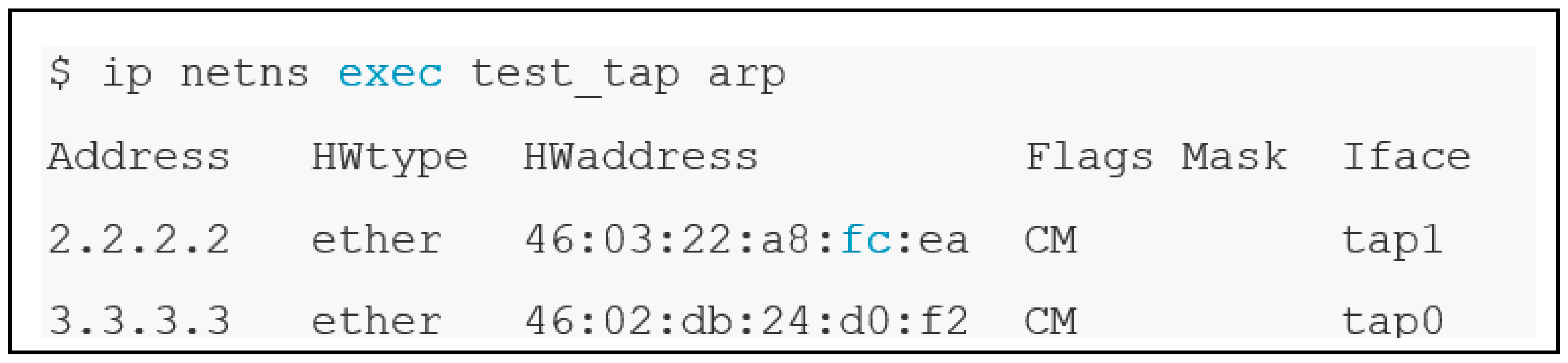

Figure 6.

Static ARP entries.

Figure 6.

Static ARP entries.

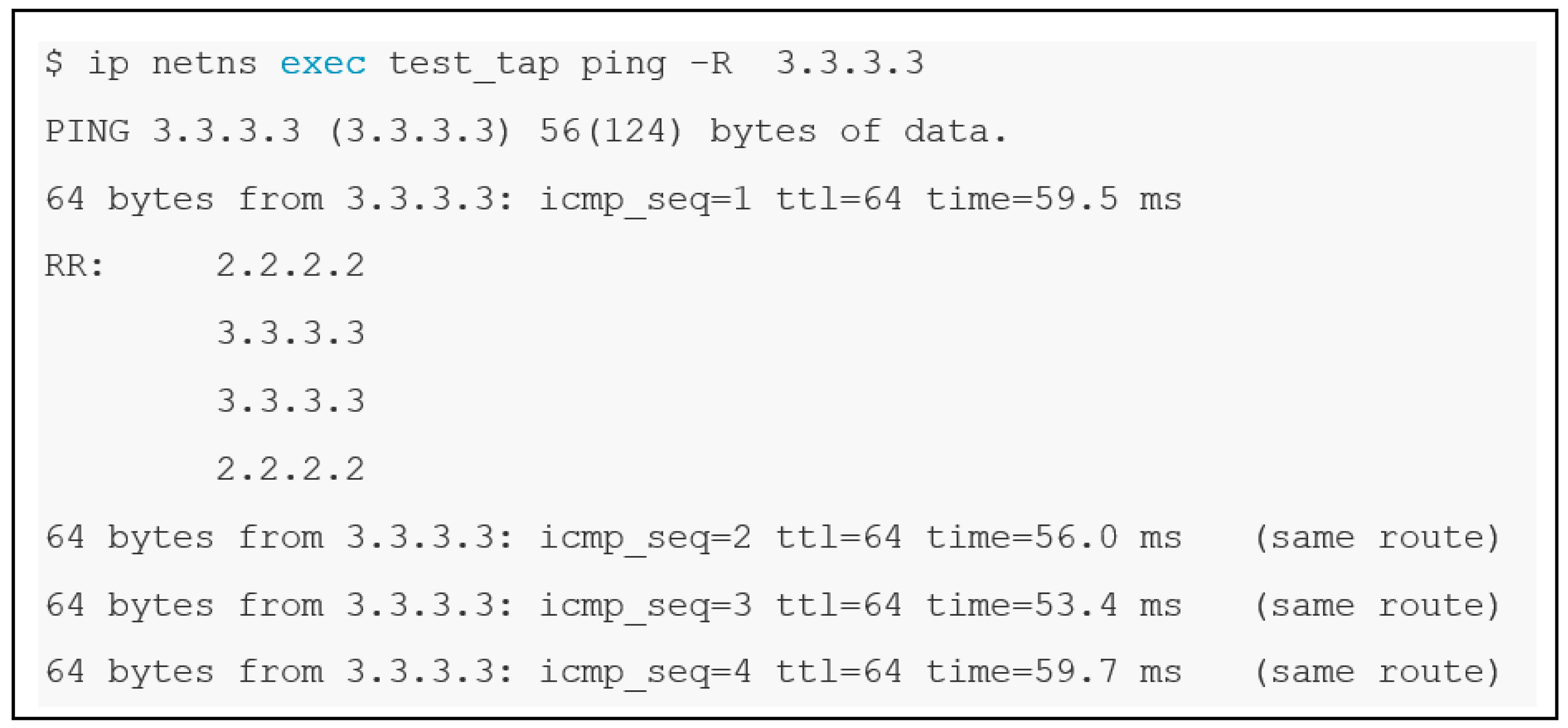

Figure 7.

Probe packets sent with the ping utility to the far end of the tunnel.

Figure 7.

Probe packets sent with the ping utility to the far end of the tunnel.

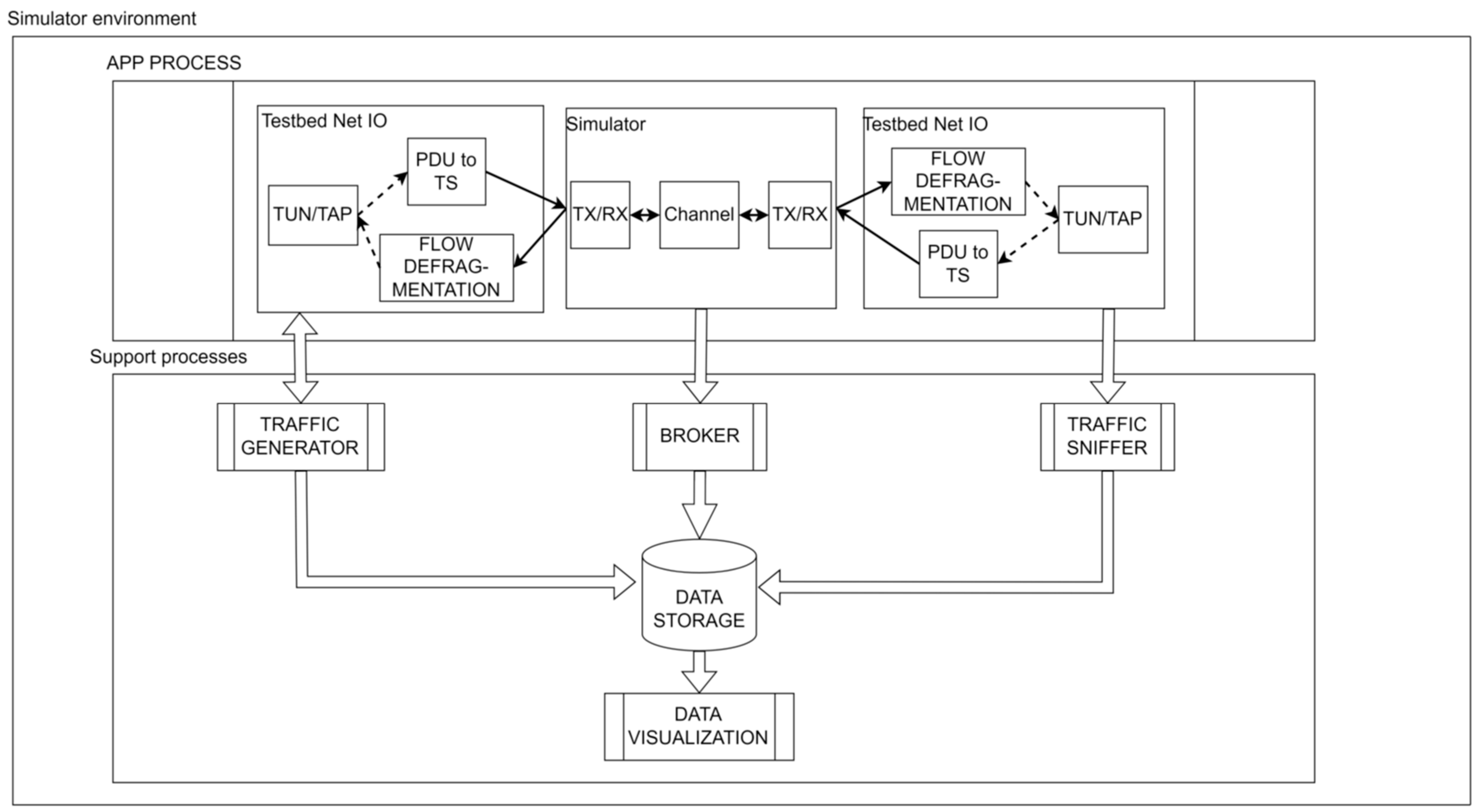

Figure 8.

The architecture of the testbed for GNU Radio applications evaluated by simulations.

Figure 8.

The architecture of the testbed for GNU Radio applications evaluated by simulations.

Figure 9.

The architecture of the developed testing framework for GNU Radio applications evaluated in real channel conditions.

Figure 9.

The architecture of the developed testing framework for GNU Radio applications evaluated in real channel conditions.

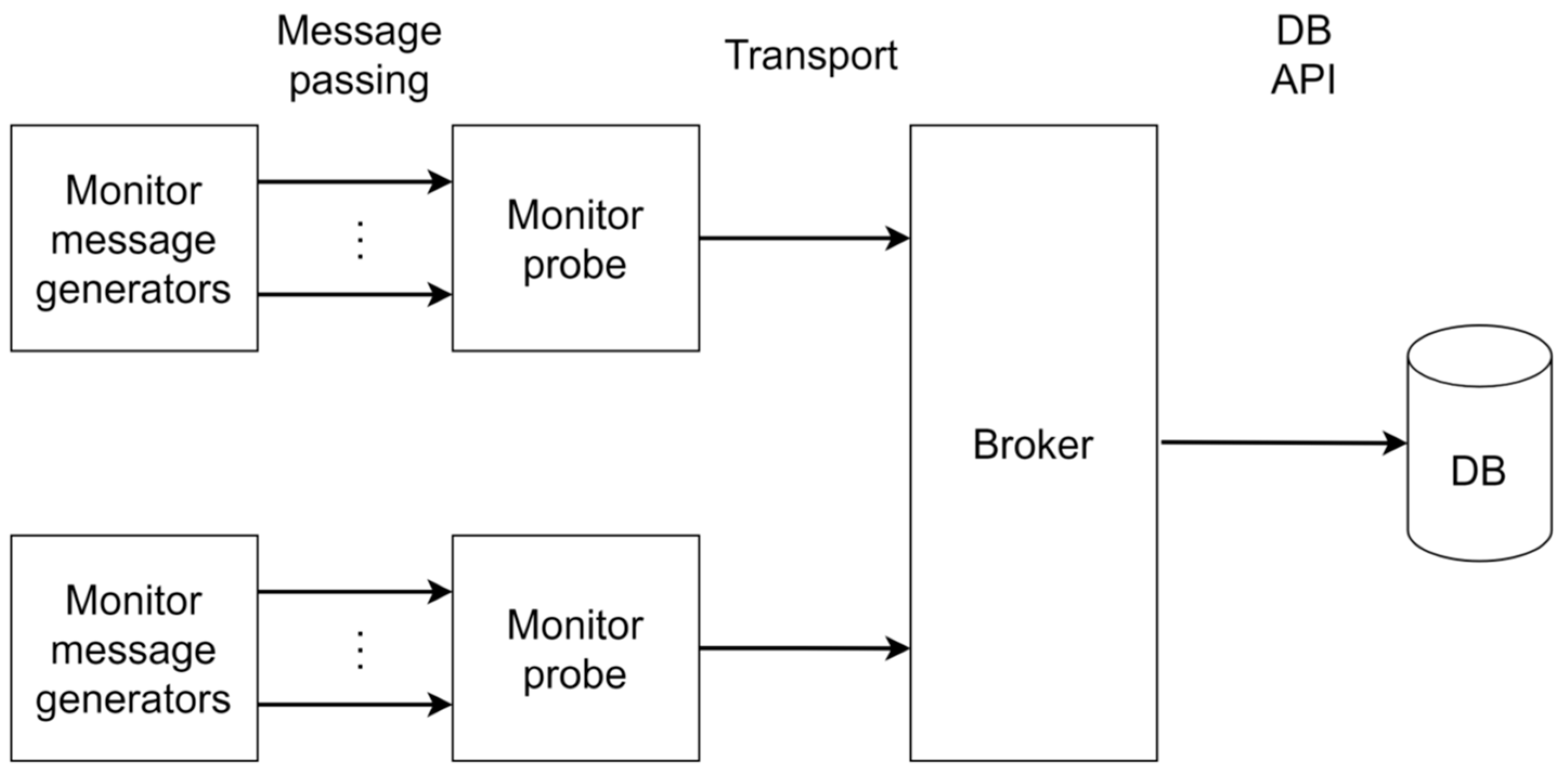

Figure 10.

The architecture of the messaging system.

Figure 10.

The architecture of the messaging system.

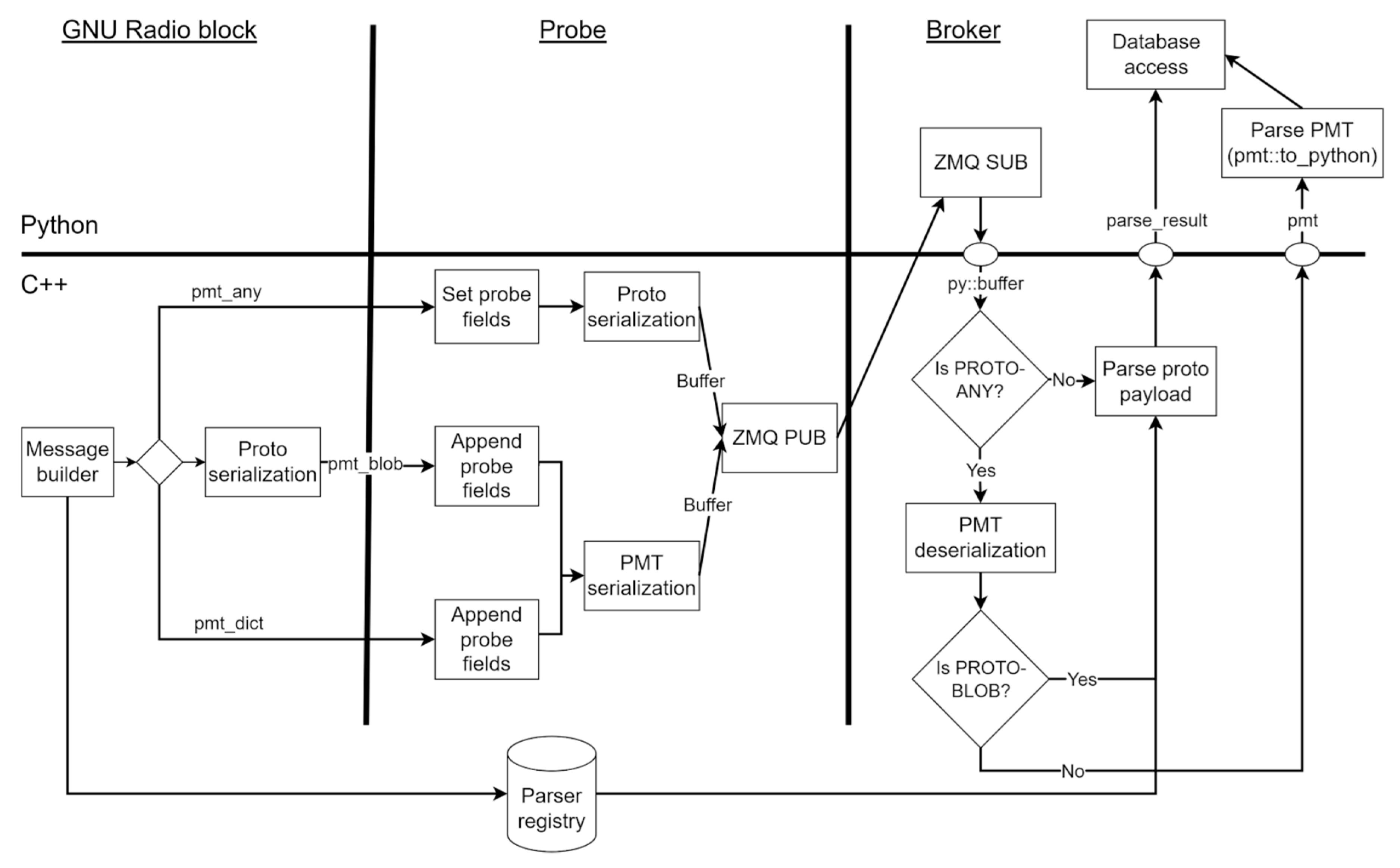

Figure 11.

The generation and transfer of monitoring messages in the messaging system for the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 11.

The generation and transfer of monitoring messages in the messaging system for the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 12.

Building a PMT monitoring message.

Figure 12.

Building a PMT monitoring message.

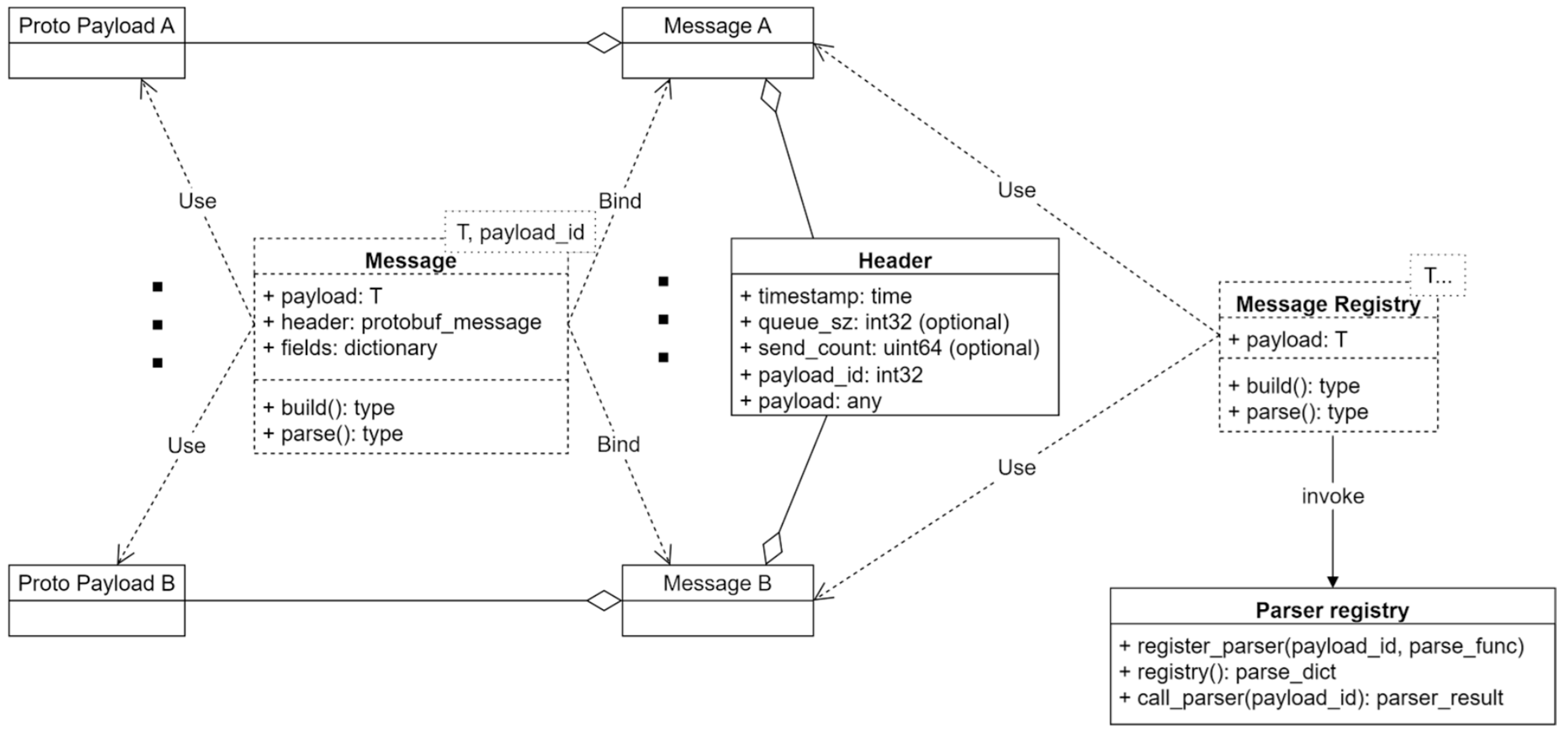

Figure 13.

The UML diagram of the PROTO messaging.

Figure 13.

The UML diagram of the PROTO messaging.

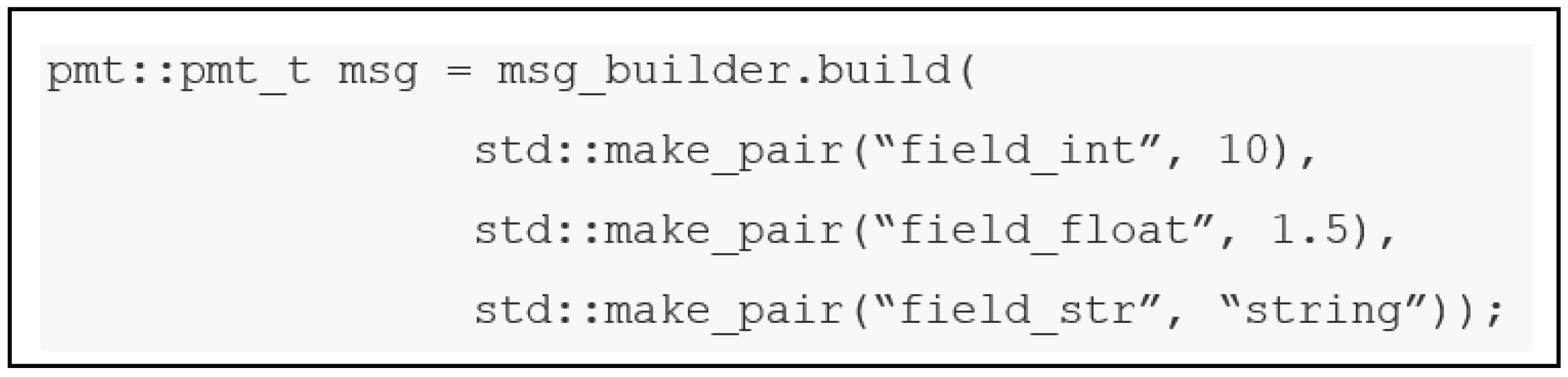

Figure 14.

Building a PROTO monitoring message using an API like that of the PMT method.

Figure 14.

Building a PROTO monitoring message using an API like that of the PMT method.

Figure 15.

Monitoring message size obtained in specific conditions using the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 15.

Monitoring message size obtained in specific conditions using the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 16.

The time necessary to generate and process the monitoring messages in specific conditions using the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 16.

The time necessary to generate and process the monitoring messages in specific conditions using the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 17.

GNU Radio process flow for evaluation of the messaging methods.

Figure 17.

GNU Radio process flow for evaluation of the messaging methods.

Figure 18.

The CPU usage of the GNU Radio process flow and of the broker in specific conditions using the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 18.

The CPU usage of the GNU Radio process flow and of the broker in specific conditions using the implemented messaging methods.

Figure 19.

The simplified architecture of the OFDM transmission system tested using the developed testing platform.

Figure 19.

The simplified architecture of the OFDM transmission system tested using the developed testing platform.

Figure 20.

Evolution in time of some parameters of the tested adaptive OFDM transmission system developed in GNU Radio.

Figure 20.

Evolution in time of some parameters of the tested adaptive OFDM transmission system developed in GNU Radio.

Table 1.

Structure of the monitoring messages.

Table 1.

Structure of the monitoring messages.

| Fields |

Mandatory |

Filled by |

Description |

| Timestamp |

Yes |

GNU Radio block |

Timestamp when the message was built. |

| Probe queue size |

No |

Monitor probe |

GNU Radio message passing API queue size. |

| Probe message counter |

No |

Monitor probe |

Number of messages sent. |

| Payload |

Yes |

GNU Radio block |

Monitoring data. |

| Payload ID |

Yes |

GNU Radio block |

Indicates the payload type for the parser. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).