Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

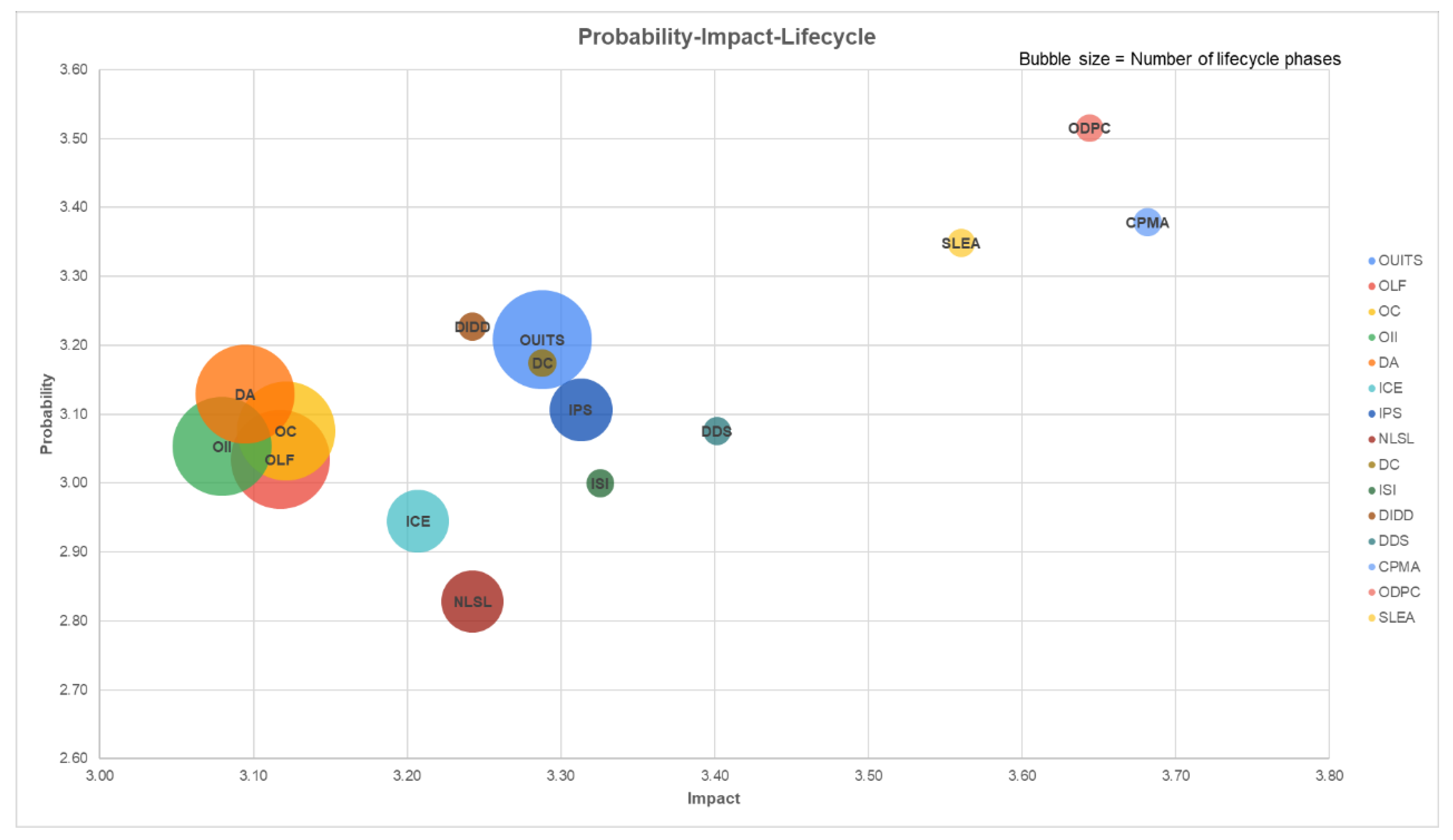

Risk management is a critical process for achieving construction project objectives and supporting more sustainable project delivery. However, most existing research focuses on isolated aspects of risk, lacking an integrated approach that examines how risks evolve across the entire project life cycle. This study addresses this gap by identifying and assessing key risks affecting construction projects in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with attention to how improved risk understanding can contribute to more resilient and sustainable project outcomes. Through a literature review, fifteen critical risks involving various stakeholders were identified. A questionnaire survey was conducted to evaluate the probability and impact of these risks on project cost. The study analyzes how these risks manifest across the project life cycle and affect different stakeholders. Using a coordinate system, it visualizes risk behavior across phases, offering a dynamic view of risk exposure. Findings show that the construction phase was the riskiest, followed by the handover, design, and feasibility phases. Additionally, delayed payments by owners emerged as the most significant risk, followed by poor contractor management. The study proposes a modified probability–impact matrix to account for multi-phase risks. These findings provide valuable insights for construction firms, helping improve stakeholder risk allocation, inform contract negotiations, and enhance project delivery in the UAE context while contributing to more efficient, responsible, and sustainable project management practices.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

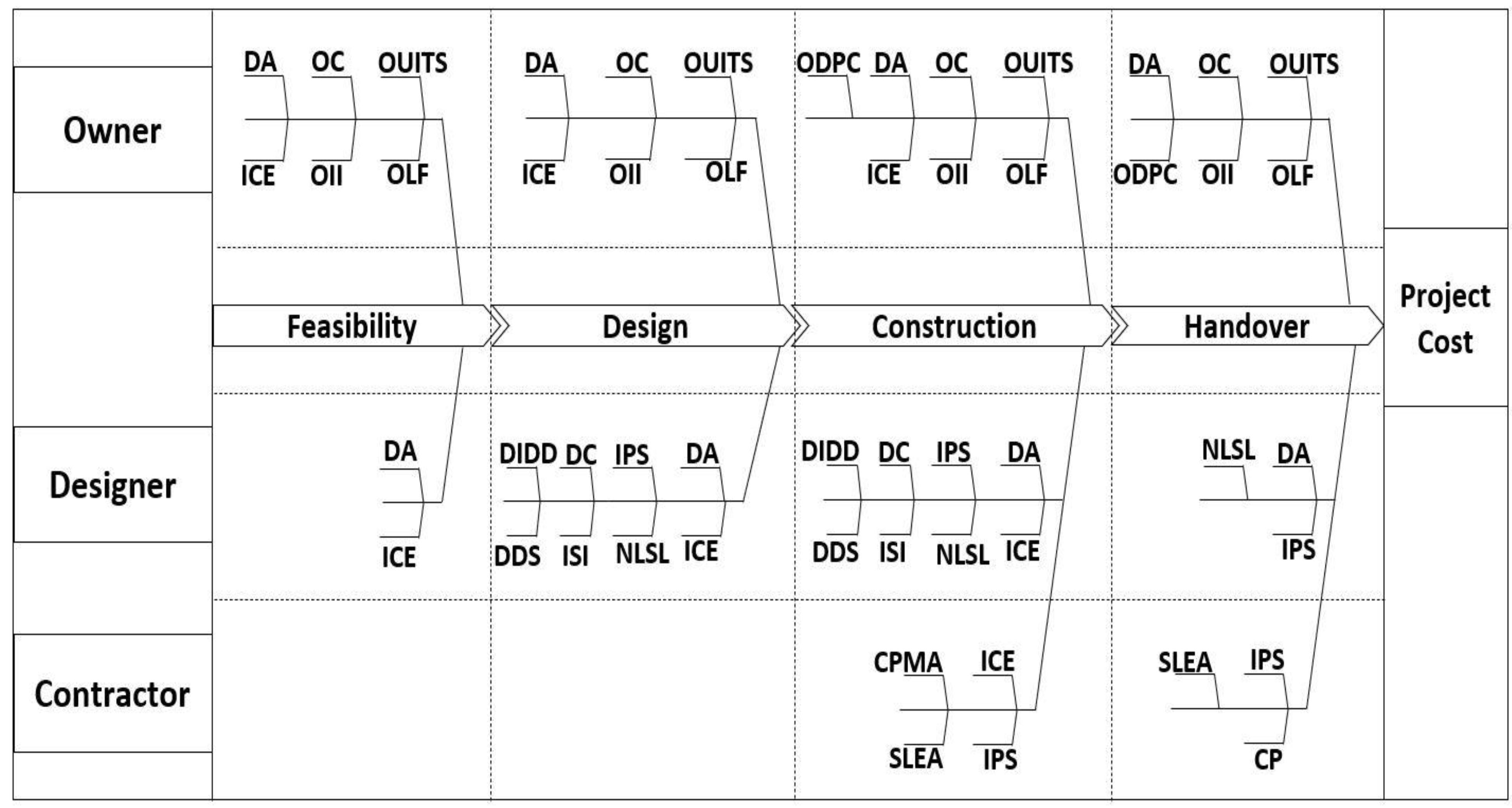

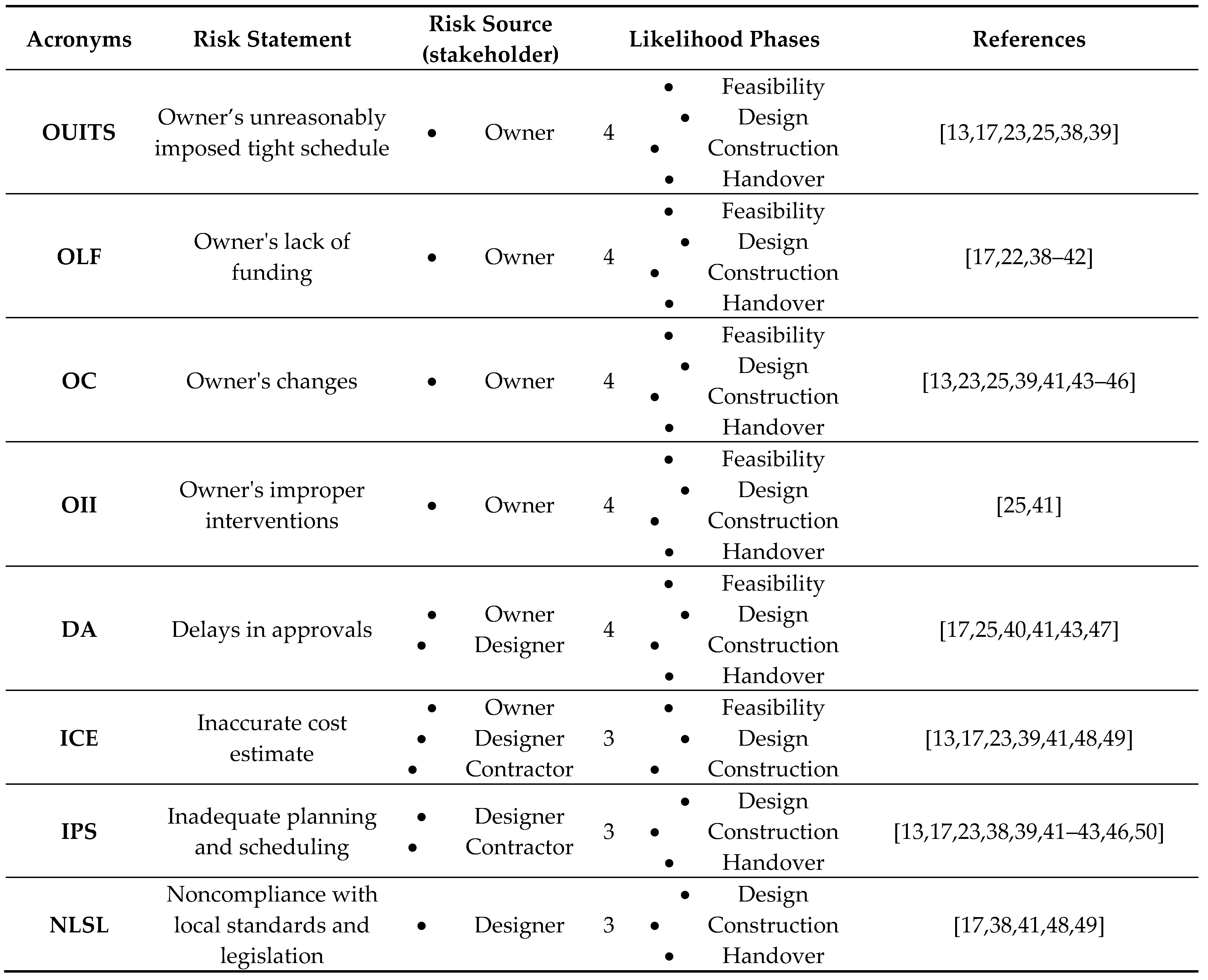

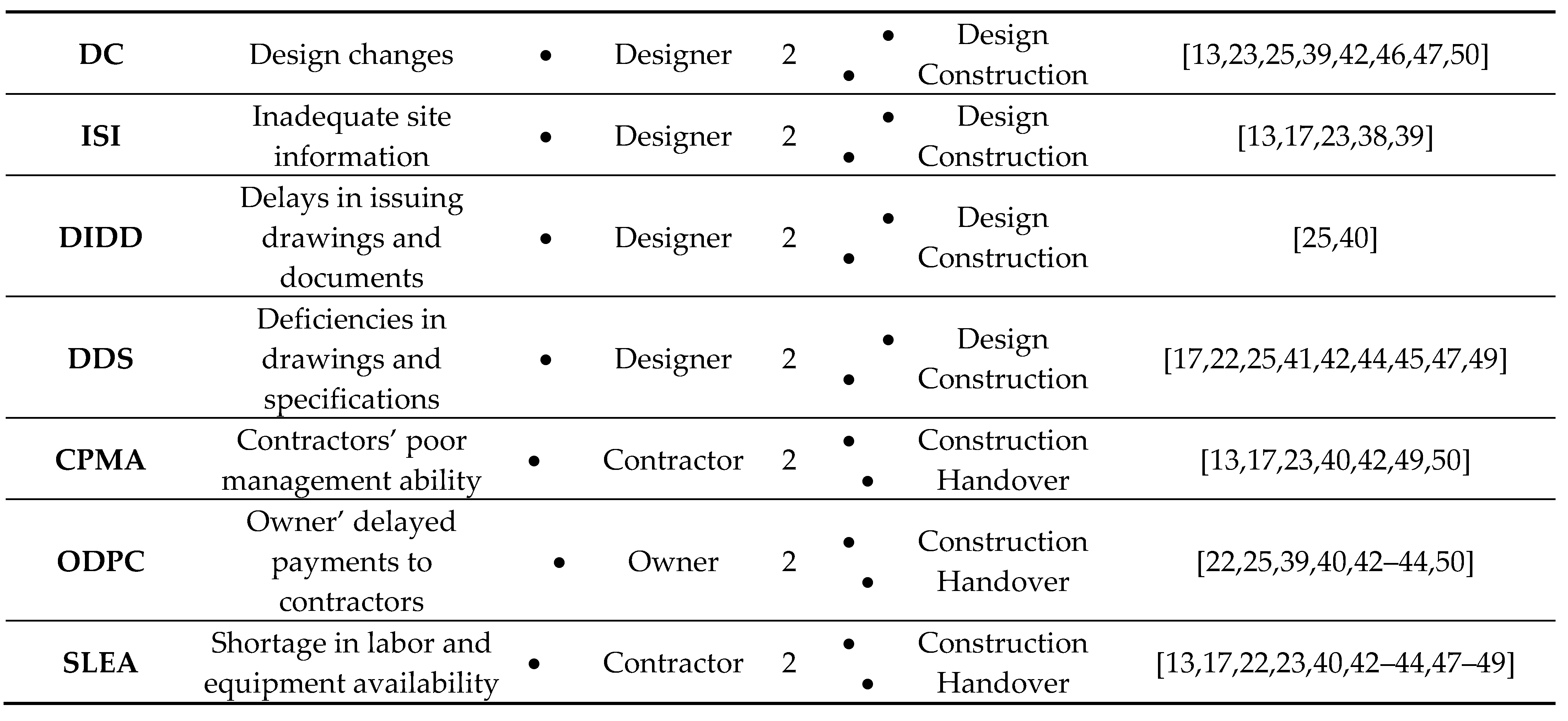

3. Risk Identification and Mapping

3.1. Feasibility-Related Risks

3.2. Design-Related Risks

3.3. Construction-Related Risks

3.4. Handover-Related Risks

4. Results and Analysis

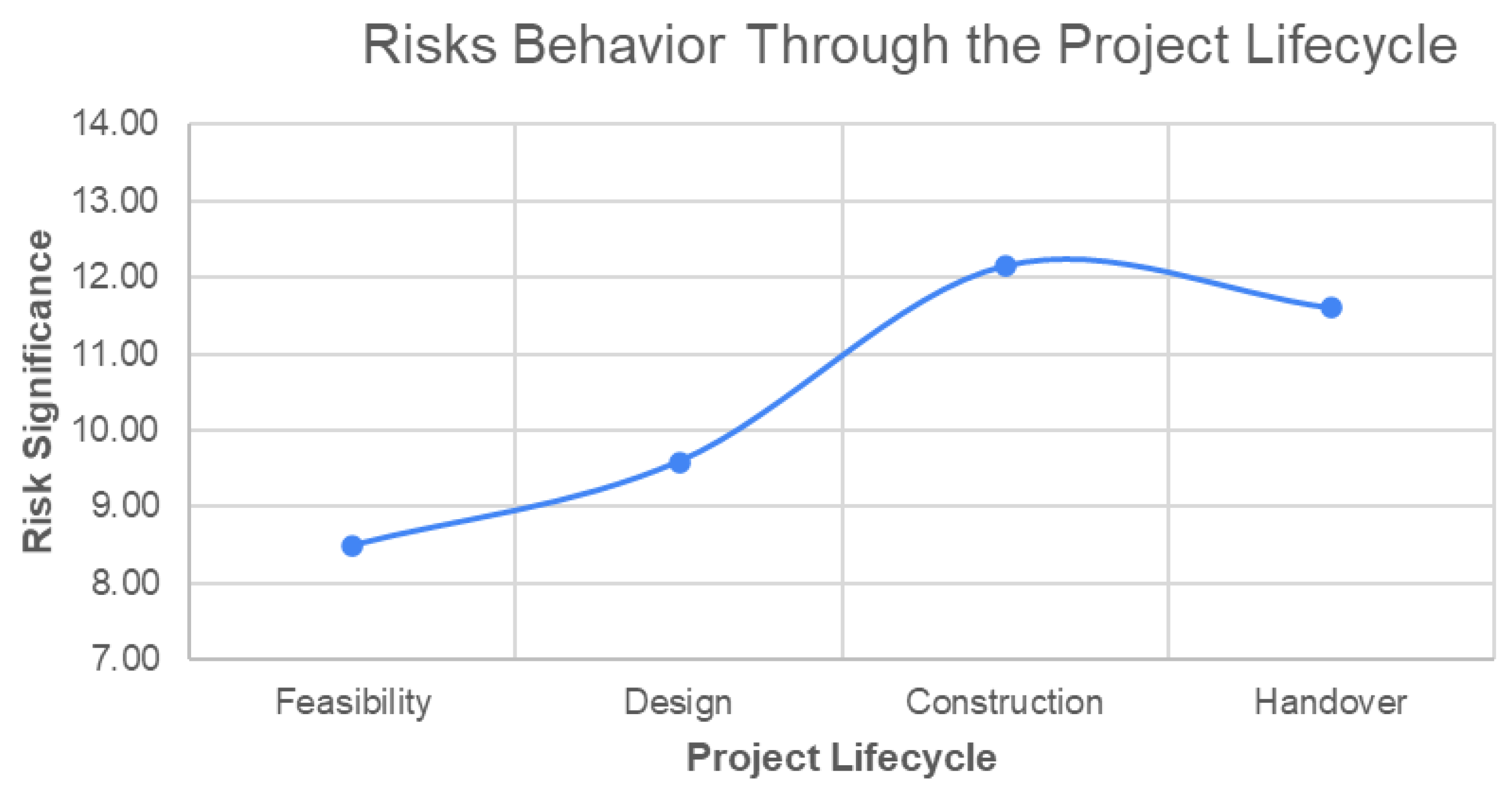

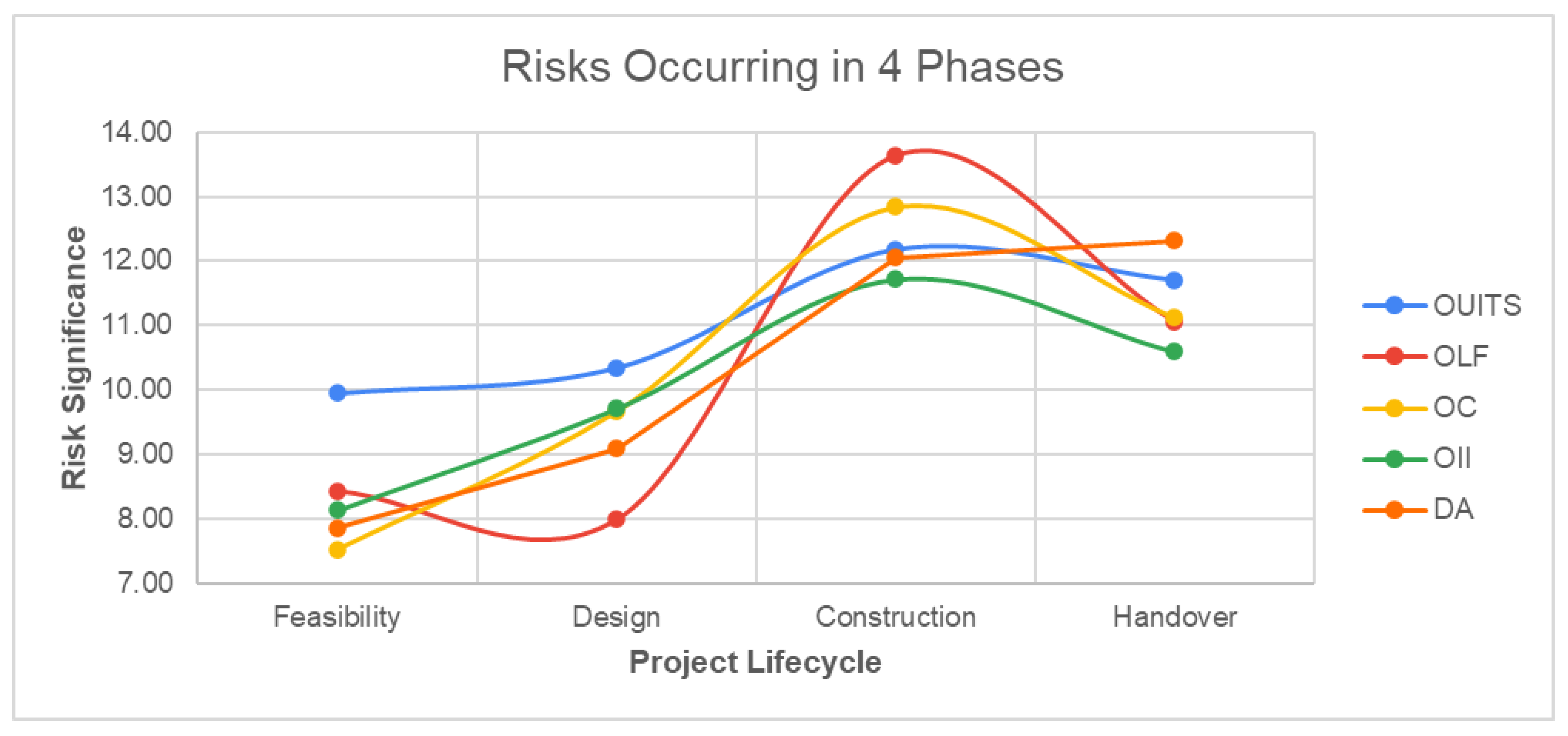

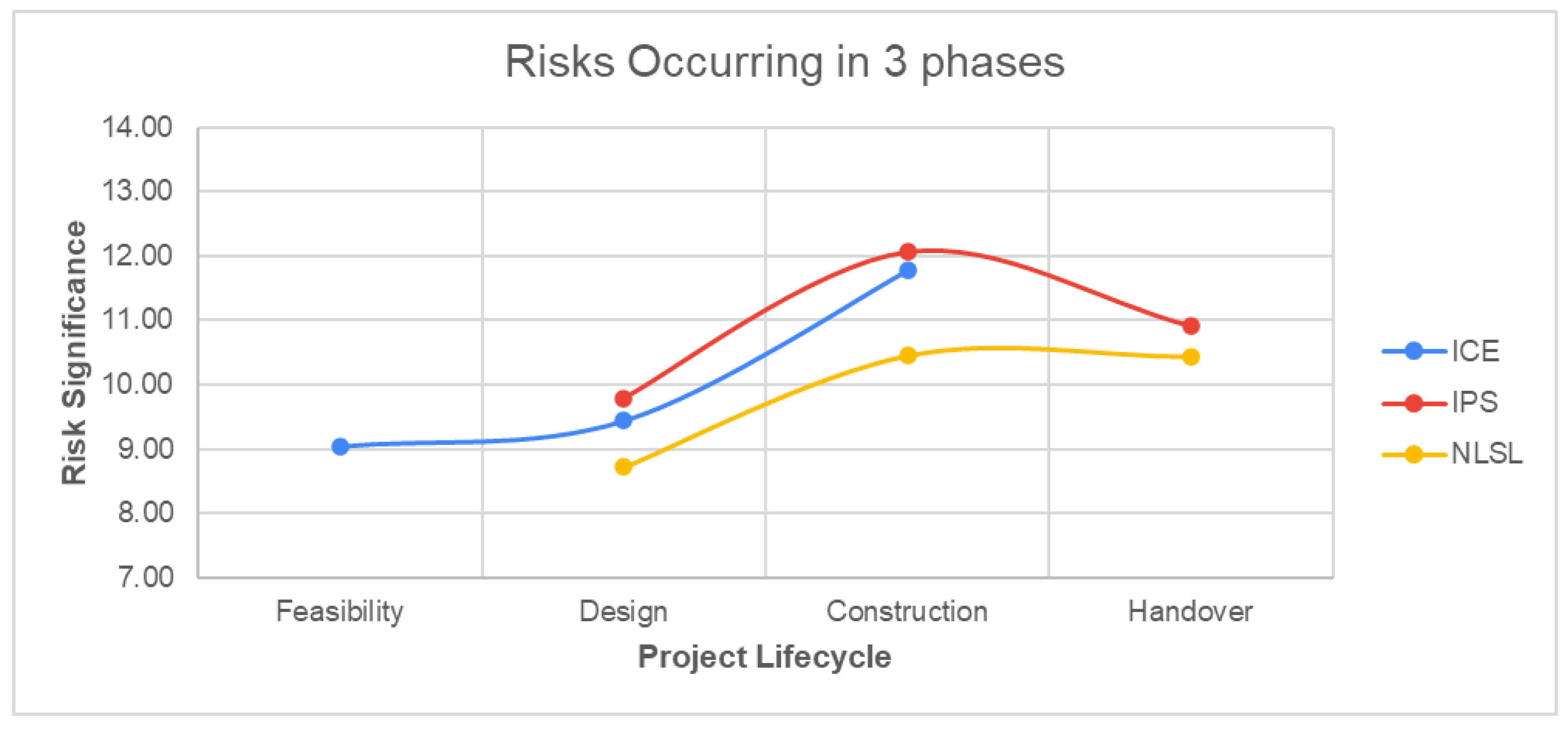

4.1. Risk Behavior Across Lifecycle Phases

| DDS | Risk ID | Risk Significance Average | Rank | Risk Source |

| Owner’s delayed payments to contractors | ODPC | 13.39 | 1 | owner |

| Contractors’ poor management ability | CPMA | 12.90 | 2 | contractor |

| Shortage in labor and equipment availability | SLEA | 12.44 | 3 | contractor |

| Design changes | DC | 11.08 | 4 | designer |

| Owner’s unreasonably imposed tight schedule | OUITS | 11.04 | 5 | owner |

| Inadequate planning and scheduling | IPS | 10.92 | 6 | Designer/contractor |

| Delays in issuing drawings and documents | DIDD | 10.89 | 7 | designer |

| Deficiencies in drawings and specifications | DDS | 10.83 | 8 | designer |

| Inadequate site information | ISI | 10.44 | 9 | designer |

| Delays in approvals | DA | 10.33 | 10 | Owner/designer |

| Owner’s changes | OC | 10.29 | 11 | owner |

| Owner’s lack of funding | OLF | 10.28 | 12 | owner |

| Inaccurate cost estimate | ICE | 10.09 | 13 | Owner/designer/contractor |

| Owner’s improper interventions | OII | 10.04 | 14 | owner |

| Noncompliance with local standards and legislation | NLSL | 9.87 | 15 | designer |

| Risk Statement | Risk ID | Risk Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility | Design | Construction | Handover | ||

| Owners unreasonably imposed tight schedule | OUITS | 9.95 | 10.35 | 12.17 | 11.70 |

| Owner’s lack of funding | OLF | 8.44 | 8.00 | 13.64 | 11.06 |

| Owner’s changes | OC | 7.53 | 9.67 | 12.83 | 11.12 |

| Owner’s improper interventions | OII | 8.14 | 9.71 | 11.71 | 10.59 |

| Delays in approvals | DA | 7.86 | 9.09 | 12.05 | 12.32 |

| Inaccurate cost estimates | ICE | 9.05 | 9.44 | 11.77 | |

| Inadequate planning and scheduling | IPS | 9.79 | 12.06 | 10.91 | |

| Noncompliance with local standards and legislation | NLSL | 8.71 | 10.45 | 10.44 | |

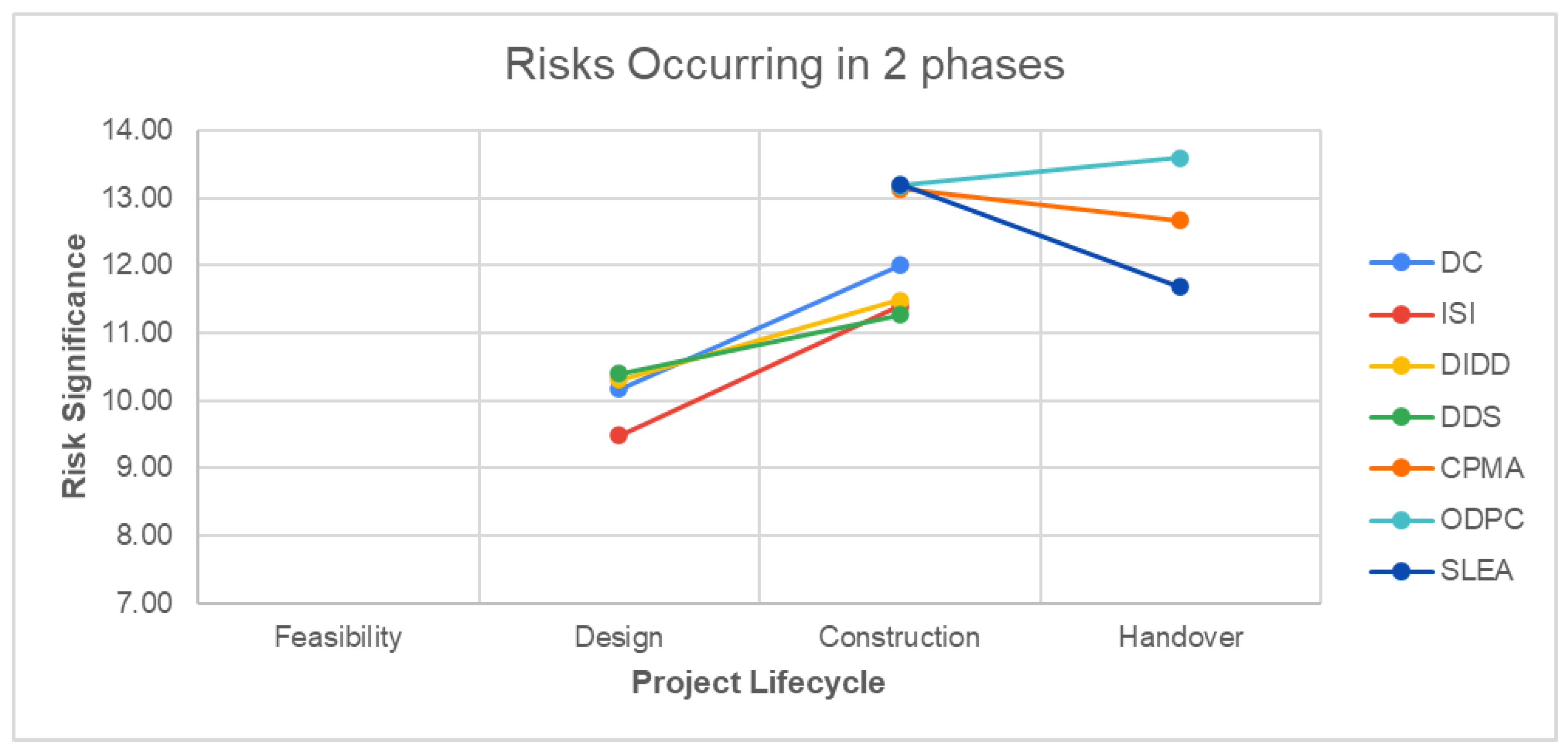

| Design changes | DC | 10.17 | 12.00 | ||

| Inadequate site information | ISI | 9.48 | 11.39 | ||

| Delays in issuing drawings and documents | DIDD | 10.30 | 11.48 | ||

| Deficiencies in drawings and specifications | DDS | 10.39 | 11.27 | ||

| Contractors’ poor management ability | CPMA | 13.14 | 12.67 | ||

| Owners delayed payments to contractors | ODPC | 13.18 | 13.59 | ||

| Shortage in labor and equipment availability | SLEA | 13.20 | 11.68 | ||

| Average | 8.49 | 9.59 | 12.16 | 11.61 | |

4.2. Phase-by-Phase Risk Recommendations

4.2.1. Feasibility Phase

4.2.2. Design Phase

4.2.3. Construction Phase

4.2.4. Handover Phase

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

References

- V. W. Y. Tam and L. Y. Shen, “Risk management for contractors in marine projects,” Organization, technology & management in construction: an international journal, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 403-410, 2012.

- G. Wang, “Computer Science and Technology and Risk Management in Engineering Construction Projects,” 2021: Springer, pp. 148-153.

- J. F. Al-Bahar, Risk management in construction projects: A systematic analytical approach for contractors. University of California, Berkeley, 1988.

- J. Birnie and A. Yates, “Cost prediction using decision/risk analysis methodologies,” Construction Management and Economics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 171-186, 1991.

- N. Dawood, “Estimating project and activity duration: a risk management approach using network analysis,” Construction Management & Economics, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 41-48, 1998.

- H. Chen, H. Guilin, S. W. Poon, and F. F. Ng, “Cost risk management in West Rail project of Hong Kong,” AACE International Transactions, p. IN91, 2004.

- I. Dikmen, M. T. Birgonul, and S. Han, “Using fuzzy risk assessment to rate cost overrun risk in international construction projects,” International journal of project management, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 494-505, 2007.

- A. Gondia, A. Siam, W. El-Dakhakhni, and A. H. Nassar, “Machine learning algorithms for construction projects delay risk prediction,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 146, no. 1, p. 04019085, 2020.

- K. Chatterjee, E. K. Zavadskas, J. Tamošaitienė, K. Adhikary, and S. Kar, “A hybrid MCDM technique for risk management in construction projects,” Symmetry, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 46, 2018.

- S. M. Hatefi and J. Tamošaitienė, “An integrated fuzzy DEMATEL-fuzzy ANP model for evaluating construction projects by considering interrelationships among risk factors,” Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 114-131, 2019.

- N. B. Siraj and A. R. Fayek, “Risk identification and common risks in construction: Literature review and content analysis,” Journal of construction engineering and management, vol. 145, no. 9, p. 03119004, 2019.

- F. Nasirzadeh, M. Khanzadi, and M. Rezaie, “Dynamic modeling of the quantitative risk allocation in construction projects,” International journal of project management, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 442-451, 2014.

- P. X. W. Zou, G. Zhang, and J.-Y. Wang, “Identifying key risks in construction projects: life cycle and stakeholder perspectives,” 2006.

- J. Geraldi, H. Maylor, and T. Williams, “Now, let’s make it really complex (complicated): A systematic review of the complexities of projects,” International journal of operations & production management, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 966-990, 2011.

- M. S. A. Enshassi, S. Walbridge, J. S. West, and C. T. Haas, “Dynamic and proactive risk-based methodology for managing excessive geometric variability issues in modular construction projects using Bayesian theory,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 146, no. 2, p. 04019096, 2020.

- T. E. Uher and A. R. Toakley, “Risk management in the conceptual phase of a project,” International journal of project management, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 161-169, 1999.

- R. J. Chapman, “The controlling influences on effective risk identification and assessment for construction design management,” International journal of project management, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 147-160, 2001.

- H. Khamooshi, “A Dynamic and practical approach to Project Risk Analysis and Management,” 2004, vol. 21: Citeseer, 1 ed.

- F. Nasirzadeh, A. Afshar, and Z. M. Khan, “System dynamics approach for construction risk analysis,” 2008.

- H. Tang, G. Wang, Y. Miao, and P. Zhang, “Managing Cost-Based Risks in Construction Supply Chains: A Stakeholder-Based Dynamic Social Network Perspective,” Complexity, vol. 2020, no. 1, p. 8545839, 2020.

- S. Dixit, K. Sharma, and S. Singh, “Identifying and analysing key factors associated with risks in construction projects,” in Emerging Trends in Civil Engineering: Select Proceedings of ICETCE 2018: Springer, 2020, pp. 25-32.

- Andi, “The importance and allocation of risks in Indonesian construction projects,” Construction Management and Economics, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 69-80, 2006.

- P. X. W. Zou, G. Zhang, and J. Wang, “Understanding the key risks in construction projects in China,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 601-614, 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. Guide, A guide to the project management body of knowledge. 2008.

- S. M. El-Sayegh, “Risk assessment and allocation in the UAE construction industry,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 431-438, 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Atout, “Delays caused by project consultants and designers in construction projects,” International Journal of Structural and Civil Engineering Research, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 102-107, 2016.

- S. J. Hymes, “Architect’s Essentials of Cost Management,” Cost Engineering, vol. 46, no. 2, p. 21, 2004.

- J.-G. Nibbelink, M. Sutrisna, and A. U. Zaman, “Unlocking the potential of early contractor involvement in reducing design risks in commercial building refurbishment projects–a Western Australian perspective,” Architectural Engineering and Design Management, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 439-456, 2017.

- N. Cross, “Forty years of design research,” vol. 28, ed: Elsevier, 2007, pp. 1-4.

- J. Cramer and S. Breitling, Architecture in existing fabric: Planning, design, building. Walter De Gruyter, 2012.

- A. Laufer, A. Shapira, and D. Telem, “Communicating in dynamic conditions: How do on-site construction project managers do it?,” Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 75-86, 2008.

- M. Taghipour, F. Seraj, M. A. Hassani, and S. Farahani Kheirabadi, “Risk analysis in the management of urban construction projects from the perspective of the employer and the contractor,” International Journal of Organizational Leadership, vol. 4, pp. 356-373, 2015.

- H. Karimi, T. R. B. Taylor, G. B. Dadi, P. M. Goodrum, and C. Srinivasan, “Impact of skilled labor availability on construction project cost performance,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 144, no. 7, p. 04018057, 2018.

- K. C. Iyer, R. Kumar, and S. P. Singh, “Understanding the role of contractor capability in risk management: a comparative case study of two similar projects,” Construction management and economics, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 223-238, 2020.

- C. S. Schultz, K. Jørgensen, S. Bonke, and G. M. G. Rasmussen, “Building defects in Danish construction: project characteristics influencing the occurrence of defects at handover,” Architectural Engineering and Design Management, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 423-439, 2015.

- I. Shirkavand, J. Lohne, and O. Lædre, “Defects at handover in Norwegian construction projects,” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 226, pp. 3-11, 2016.

- J. Lohne, A. Engebø, and O. Lædre, “Ethical challenges during construction project handovers,” International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 31-53, 2020.

- K. Koc and A. P. Gurgun, “Stakeholder-associated life cycle risks in construction supply chain,” Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 37, no. 1, p. 04020107, 2021.

- A. Rostami and C. F. Oduoza, “Key risks in construction projects in Italy: contractors’ perspective,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 451-462, 2017.

- N. Y. Zabel, M. E. Georgy, and M. E. Ibrahim, “Developing a dynamic risk map (DRM) for pipeline construction projects in the Middle East,” 2012, pp. 175-187.

- D. Badran, R. AlZubaidi, and S. Venkatachalam, “BIM based risk management for design bid build (DBB) design process in the United Arab Emirates: a conceptual framework,” International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 1339-1361, 2020.

- T.-C. Tsai and M.-L. Yang, “Risk management in the construction phase of building projects in Taiwan,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 143-150, 2009.

- S. M. El-Sayegh and M. H. Mansour, “Risk assessment and allocation in highway construction projects in the UAE,” Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 31, no. 6, p. 04015004, 2015.

- R. Kangari, “Risk management perceptions and trends of US construction,” Journal of construction engineering and management, vol. 121, no. 4, pp. 422-429, 1995.

- M.-T. Wang and H.-Y. Chou, “Risk allocation and risk handling of highway projects in Taiwan,” Journal of management in Engineering, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 60-68, 2003.

- L. F. Alarcón, D. B. Ashley, A. S. de Hanily, K. R. Molenaar, and R. Ungo, “Risk planning and management for the Panama Canal expansion program,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 137, no. 10, pp. 762-771, 2011.

- L. Bing, A. Akintoye, P. J. Edwards, and C. Hardcastle, “The allocation of risk in PPP/PFI construction projects in the UK,” International Journal of project management, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 25-35, 2005.

- A. J. Marinho and J. P. Couto, “Construction risk management in Portugal—identification of the tools/techniques and specific risks in the design and construction phases,” 2021: Springer, pp. 237-251.

- A. Suharyanto and M. R. A. Simanjuntak, “Identification of Design And Build Risks in School Building Construction Projects in Central Jakarta,” 2020, vol. 852: IOP Publishing, 1 ed., p. 012049.

- S. Q. Wang, M. F. Dulaimi, and M. Y. Aguria, “Risk management framework for construction projects in developing countries,” Construction management and economics, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 237-252, 2004.

- V. Del Giudice, A. Passeri, F. Torrieri, and P. De Paola, “Risk analysis within feasibility studies: An application to cost-benefit analysis for the construction of a new road,” Applied mechanics and materials, vol. 651, pp. 1249-1254, 2014.

- A. Bagheri Khoulenjani, M. Talebi, and E. Karim Zadeh, “Feasibility Study for Construction Projects in Uncertainty Environment with Optimization Approach,” International journal of sustainable applied science and engineering, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-15, 2024.

- R. Eadie and M. Graham, “Analysing the advantages of early contractor involvement,” International journal of procurement management, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 661-676, 2014.

- R. M. N. Hemal, K. Waidyasekara, and E. Ekanayake, “Integrating design freeze in to large-scale construction projects in Sri Lanka,” 2017: IEEE, pp. 259-264.

- V. Bhat, J. S. Trivedi, and B. Dave, “Improving design coordination with lean and BIM an Indian case study,” 2018, pp. 1206-1216.

- N. Mouraviev and N. K. Kakabadse, “Risk allocation in a public–private partnership: a case study of construction and operation of kindergartens in Kazakhstan,” Journal of Risk Research, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 621-640, 2014.

- T. Ramachandra and J. O. B. Rotimi, “Mitigating payment problems in the construction industry through analysis of construction payment disputes,” Journal of legal affairs and dispute resolution in engineering and construction, vol. 7, no. 1, p. A4514005, 2015.

- E. Peters, K. Subar, and H. Martin, “Late payment and nonpayment within the construction industry: Causes, effects, and solutions,” Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 04519013, 2019.

- H. Golabchi and A. Hammad, “Estimating labor resource requirements in construction projects using machine learning,” Construction innovation, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 1048-1065, 2024.

- J. Too, O. A. Ejohwomu, T. O. Bukoye, F. K. P. Hui, and O. S. Oshodi, “Standardising the route to project handover to improve the delivery of major building projects,” International Journal of Business Performance Management, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 175-199, 2023.

| Category | Type |

Number of Respondents (Total 66) |

Percentage of Respondents (%) |

| Current Role | Owner | 12 | 18.2% |

| Designer | 15 | 22.7% | |

| Contractor | 39 | 59.1% | |

| Company | Local | 17 | 25.8% |

| International | 49 | 74.2% | |

| Level of Experience | <5 years | 25 | 37.9% |

| 5-10 years | 21 | 31.8% | |

| 11-20 years | 13 | 19.7% | |

| >20 years | 7 | 10.6% |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).