1. Introduction

Seed dispersal and germination are fundamental processes in plant life cycles shaping species distributions, community structures, and ecosystem functions [

1,

2]. Dispersal reduces competition by enabling seeds to escape parental influence and colonize new habitats, enhancing seedling establishment. Germination, the transition from dormancy to active growth, is crucial for optimizing seedling survival [

3]. These interconnected processes govern the plant establishment, linking reproductive success to offspring survival [

4]. Understanding their roles and interactions across ecological contexts is vital for evaluating plant adaptation and population persistence in changing environments.

Seed dormancy is a key adaptive strategy that regulates germination timing in response to environmental cues and seasonal variation. Among its various forms, physiological dormancy is the most common, including conditional dormancy, where seeds cyclically transition between dormant and non-dormant states depending on external conditions [

5]. This flexibility allows seeds to delay germination under unfavorable conditions and synchronize emergence with periods that maximize seedling establishment, particularly in ecosystems characterized by strong seasonality, such as temperate and alpine regions [

6,

7]. Beyond physiological mechanisms, physical structures like the seed coat, wings, and other appendages also play a role in germination regulation. Although dormancy and dispersal have traditionally been examined as distinct processes, growing evidence suggests that dispersal-related structures can directly influence germination timing and success [

8,

9].

A large group of plants possess seeds with additional appendages, such as winged perianth or bracteole, which play critical roles in both seed dispersal [

10,

11]. The presence of those appendages also affects seed germination in many angiosperms. Wing-like structures, including the perianth in

Acer saccharinum and

Ulmus americana [

12] , and the pappus in

Taraxacum officinale [

13], enhance wind dispersal and may promote germination by facilitating water uptake and enabling rapid radicle emergence under favorable conditions. In contrast, appendages such as bracteoles in

Atriplex species, pappi in

Taraxacum, and seed wings in

Ulmus,

Acer, and

Salsola species can inhibit germination by creating mechanical barriers [

14], inducing light requirements [

15], releasing chemical inhibitors like abscisic acid [

16,

17], or restricting water absorption and light availability [

3,

18].

Many gymnosperm, particularly in the

Pinaceae and

Cupressaceae—also commonly possess seed wings, as observed in

Picea purpurea,

Abies forrestii,

Pinus bungeana,

Pinus massoniana,and

Larix lyallii. These gymnosperm-dominated forests, which are vital components of boreal taiga, temperature and subtropical subalpine ecosystems, cover over 40% of the global forested area and are crucial for carbon sequestration and ecological stability [

19,

20,

21]. Despite their ecological importance, the role of seed wings in regulating germination in gymnosperms is poorly understood, potentially hindering our comprehension of their ecological adaptations and responses to global change.

This study focuses on the seeds of the Smith fir, a dominant tree species at the alpine treeline across the eastern Tibetan Plateau, where it faces harsh low temperatures and a short growing season. Previous studies show that Smith fir seeds germinate optimally between 15 and 20 °C, suggesting that germination may occur in spring, summer, or autumn under suitable climatic conditions. The seeds possess membranous wings and are typically dispersed in October, but no substantial germination has been observed during the autumn or winter in natural settings [

22]. This raises the key ecological question: how do Smith fir seeds avoid germinating in autumn and instead delay germination until the following spring?

The cause of delayed germination in Smith fir seeds, whether due to dormancy or inhibition by seed wings, remains unclear. We hypothesize that Smith fir seeds delay germination through dormancy or wing-mediated regulation, aligning germination with seasonal conditions after spring snowmelt in subalpine regions. To address these gaps, we propose the following research questions: (1) Do Smith fir seeds exhibit dormancy, and how do they respond to seasonal environmental conditions in the field? (2) In addition to dispersal, do seed wings influence germination timing or success, and if so, by what mechanisms?

2. Results

2.1. Seed Morphological Characteristics

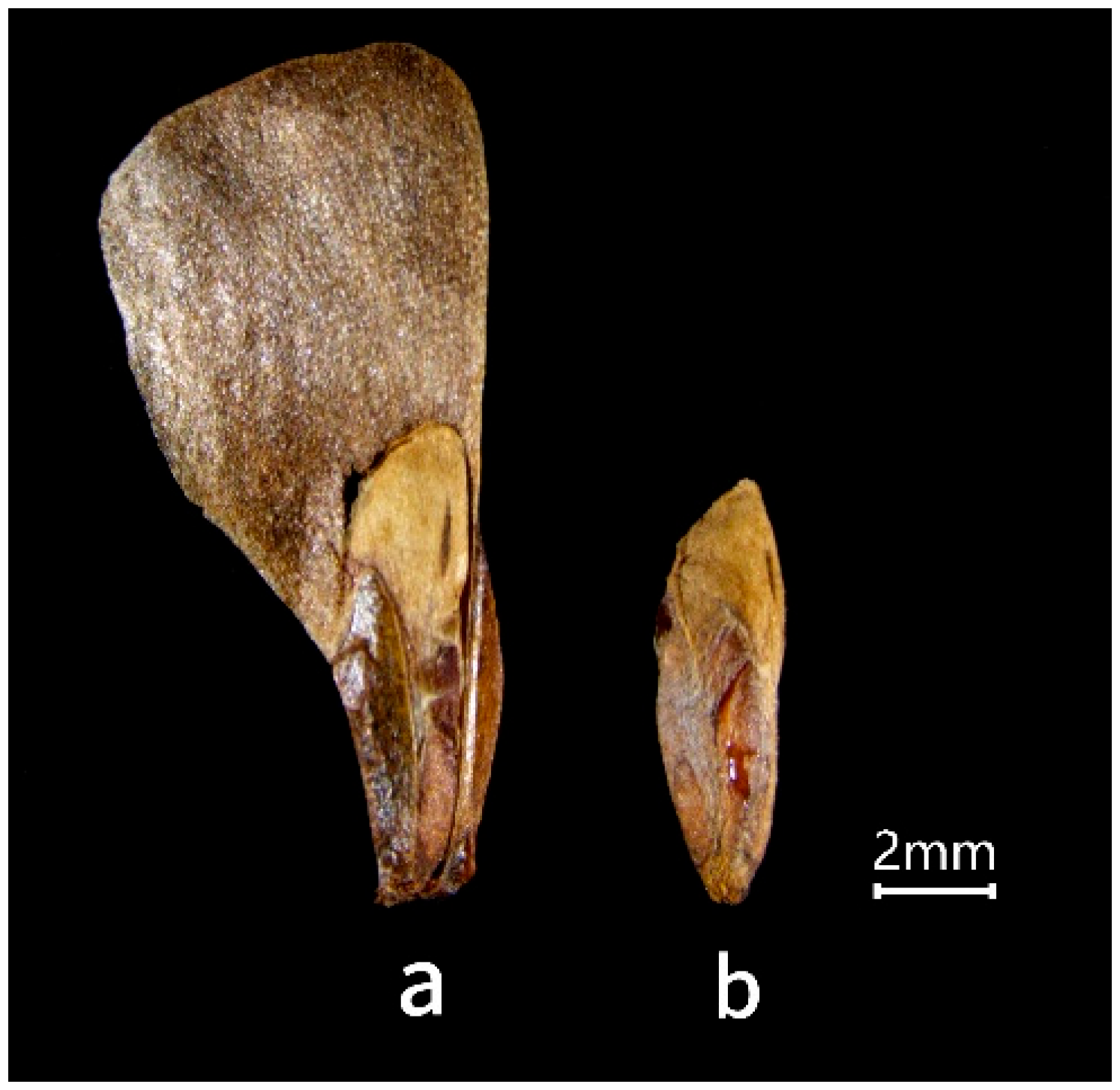

Smith fir seeds are elongated ovoids with translucent membranous wings, the base not fully covered by the wings (

Figure 1). Intact seeds averaged 11.52 ± 0.01 mm in length and 7.23 ± 0.034 mm in width, while de-winged seeds had a mean length of 3.01 ± 0.025 mm. The thousand-seed weight was 8.59 ± 0.03 g , which is relatively small among

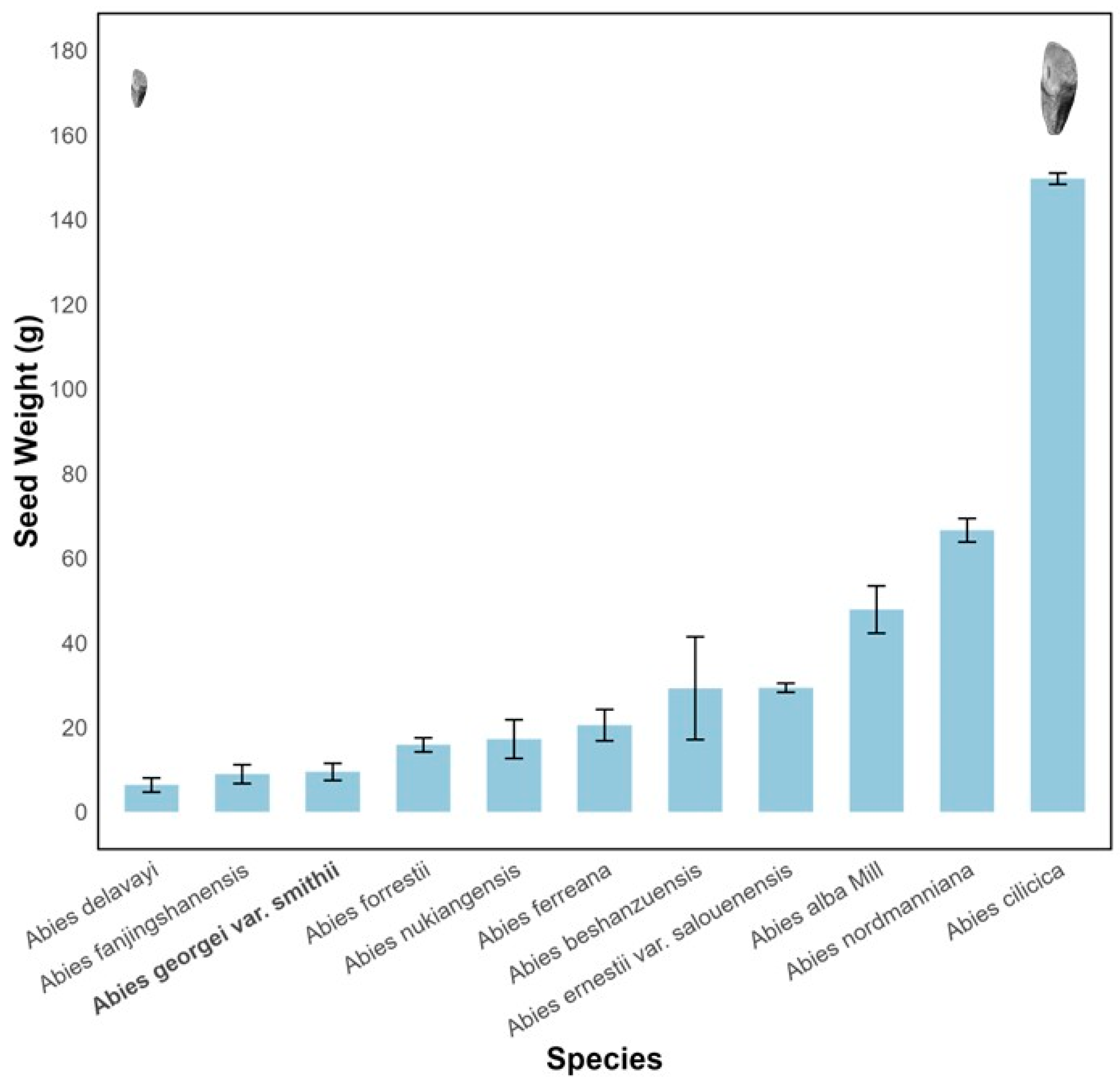

Abies species(

Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Morphology of intact seed (a) and de-winged seed (b) of Smith fir.

Figure 1.

Morphology of intact seed (a) and de-winged seed (b) of Smith fir.

Figure 2.

Variation in seed weight among Abies species. Seed weight refers to the thousand-seed weight.

Figure 2.

Variation in seed weight among Abies species. Seed weight refers to the thousand-seed weight.

Figure 3.

Relationship between seed weight and elevation in Abies species. Seed weight refers to the thousand-seed weight.

Figure 3.

Relationship between seed weight and elevation in Abies species. Seed weight refers to the thousand-seed weight.

2.2. Effect of Temperature and Light on Seed Germination

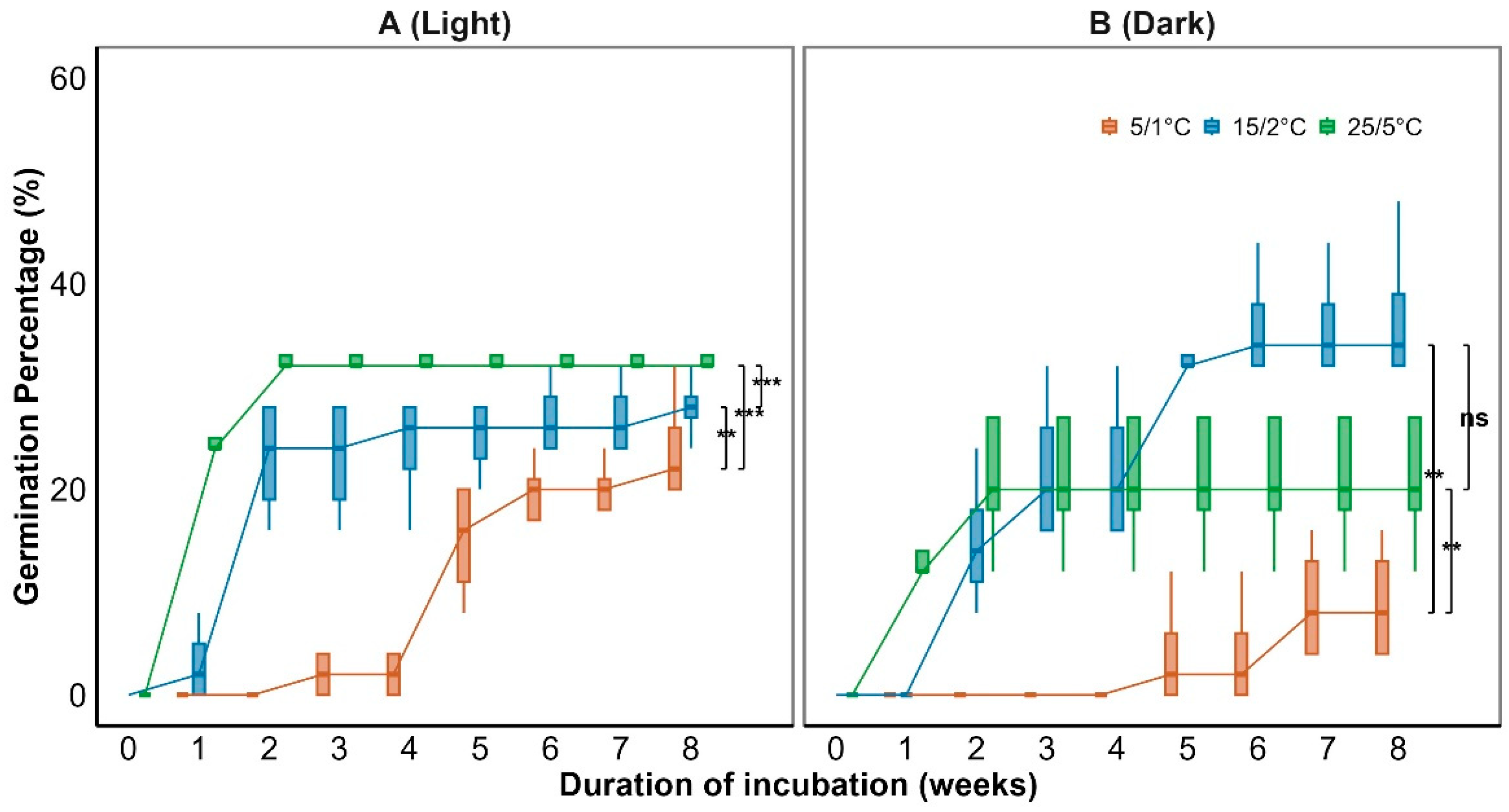

Generalized linear models (GLMs) showed that both temperature and light significantly affected seed germination (

P < 0.001;

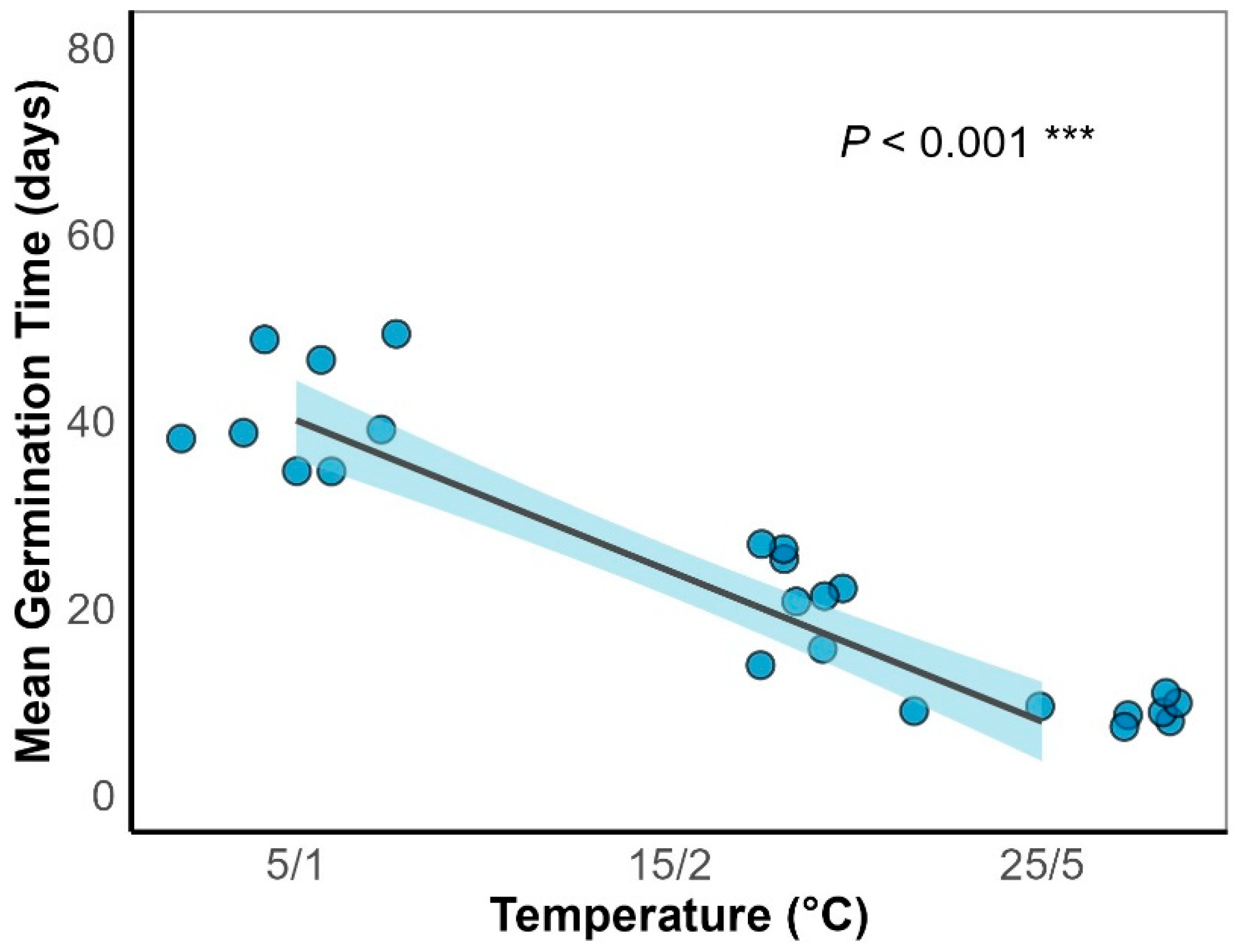

Figure 4). Temperature also significantly influenced mean germination time (MGT) (

P < 0.001;

Figure 5). Germination increased with temperature, reaching a maximum of 48% at 15/2 ℃ (

Figure 4). MGT decreased with temperature consistently under both light and dark conditions, indicating that higher temperatures accelerated germination (

Figure 5). Light further significantly enhanced germination at lower temperatures (

Figure 4), with a 32% germination percentage under the 5/1 °C regime in light, compared to only 16% under darkness, suggesting that light positively regulated germination under cold conditions.

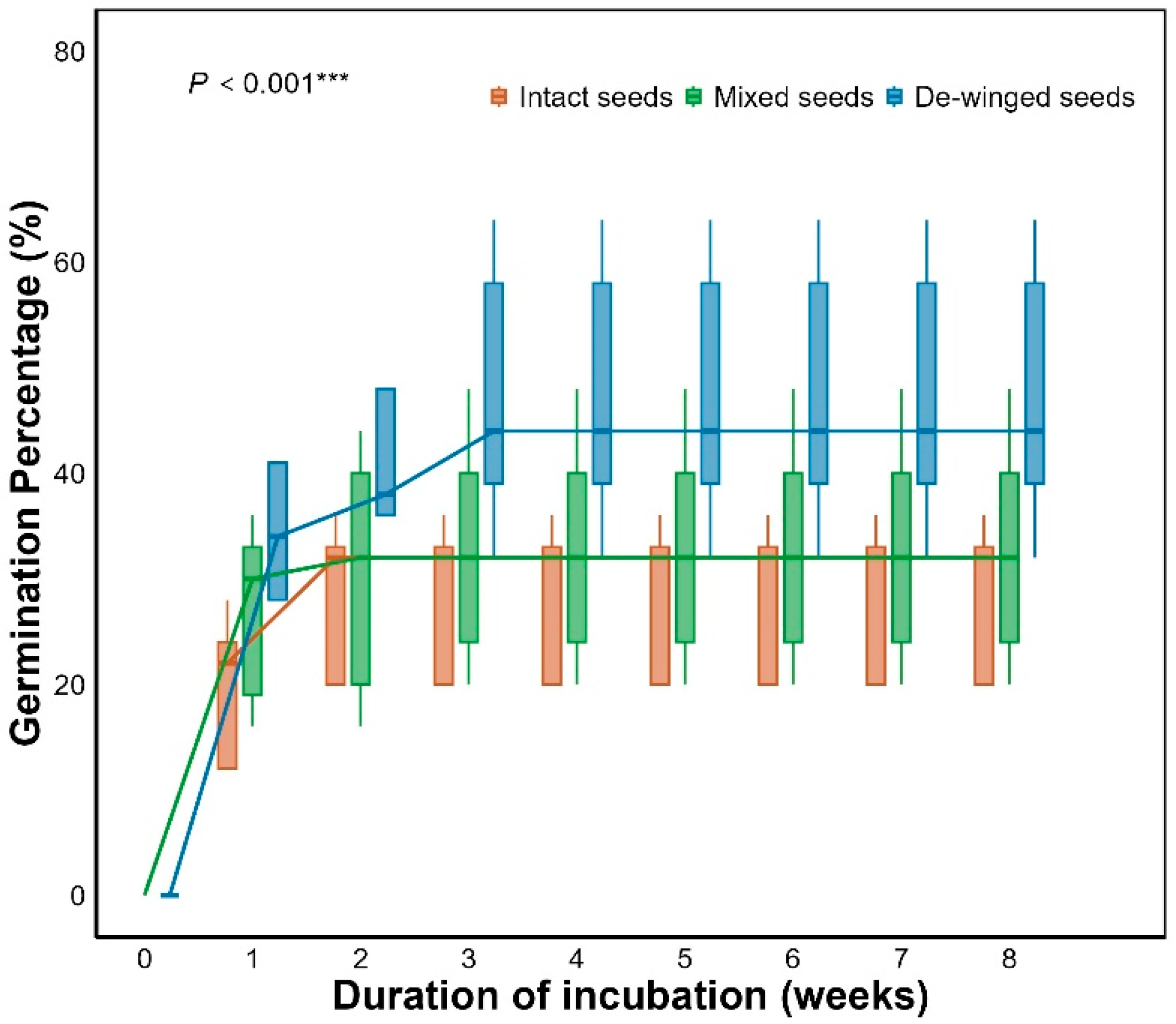

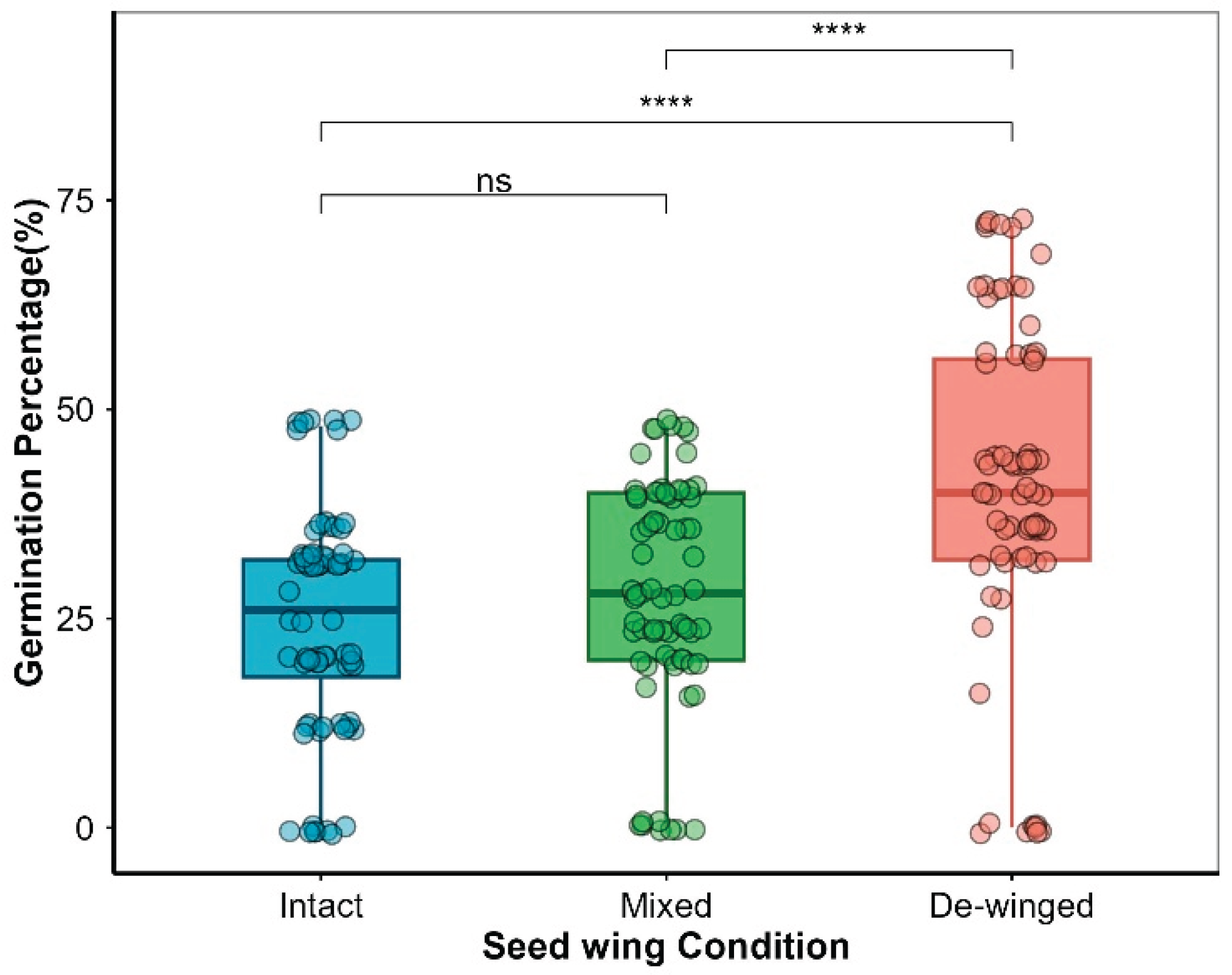

2.3. Effect of Seed Wings on Seed Germination

GLM results showed that seed wings significantly affected seed germination in Smith fir (

P < 0.001, Table 1). De-winged seeds had the highest germination percentage (50%), significantly higher than that of intact seeds (

P < 0.001;

Figure 6,

Figure 7), suggesting that seed wings inhibit germination. No significant difference was found between mixed and intact seeds, but de-winged seeds germinated significantly higher than mixed seeds (

P < 0.001;

Figure 7).

3. Discussion

This study addresses the key questions regarding the dormancy and seed wing-mediated regulation of Smith fir (

Abies georgei var.

smithii) germination. We found that Smith fir seeds exhibit conditional dormancy, with germination delayed under cold temperatures and synchronized with spring snowmelt, as hypothesized. Temperature and light were identified as critical environmental cues: higher temperatures accelerated germination, while light promoted germination under cooler conditions, aligning seedling emergence with favorable spring conditions[

3]. In addition to these environmental factors, seed wings play a significant role in inhibiting germination, likely through release of chemical inhibitors. This dual mechanism of environmental regulation and wing-mediated inhibition works together to synchronize seedling emergence with the optimal spring growing season, ensuring successful establishment in harsh subalpine habitats.

3.1. Seed Morphological Characteristics and Their Ecological Implications

Smith fir seeds are elongated ovoids with translucent membranous wings, a typical feature among conifers that aids in wind dispersal. The seeds measure 11.52 ± 0.01 mm in length and 7.23 ± 0.034 mm in width, with a thousand-seed weight of 8.59 ± 0.03 g, which is within the typical range for

Abies species (6–149g) [

23,

24]. Typically, higher elevations tend to produce smaller seeds[

25], a pattern also observed in

Abies species(

Figure 3). Although Smith fir seeds are not exceptionally large, reduced seed mass at higher elevations likely enhances wind dispersal. This pattern reflects a trade-off between dispersal efficiency and offspring provisioning, with lighter seeds favoring dispersal at the alpine treeline[

26].

Smith fir’s small seed size and large wings strike a balance between stress resistance and dispersal efficiency. Larger seeds generally provide better seedling establishment in harsh conditions, but Smith fir’s smaller seeds with large wings are more effectively dispersed by wind, facilitating colonization in high-altitude habitats. This trade-off in seed characteristics supports its survival and establishment at altitudes above 4400 m[

27], making Smith fir one of the highest-elevation forest species globally[

28,

29].

3.2. Response of Seed Germination to Temperature and Light

Temperature is a critical environmental factor regulating seed germination [

30]. In this study, Smith fir seeds exhibited optimal germination (48%)at 15/2-25/5 °C, with increasing temperatures significantly enhancing germination percentages and reducing mean germination time (MGT) (

Figure 4,

Figure 5), indicating strong thermal adaptability. The initial germination temperature requirement being relatively high in some alpine plants is explained in terms of adaptation to environmental cues that ensure seeds germinate only when conditions are favorable for seedling survival[

3].

A significant interaction between temperature and light (

P < 0.001) was detected. Light promoted germination under low temperatures (5/1 °C), whereas its effect diminished at higher temperatures, where germination remained high regardless of light (

Figure 4). This pattern suggests a seasonal shift in germination cues, from light-mediated initiation in early spring to temperature-driven germination later in the season. This indicates that light acts as an important cue under suboptimal temperature conditions, signaling the onset of favorable conditions after snowmelt. Similar light–temperature interactions have been observed in other temperate and alpine species, such as

Corylus avellana, where light promotes germination during early spring when soils are cold but snow-free[

31,

32]. Such a light-mediated response likely enables Smith fir seeds to germinate soon after snowmelt, maximizing the limited window for seedling establishment within the short subalpine growing season.

3.3. Seed Dormancy Type

According to the dormancy classification by Baskin & Baskin[

3], Smith fir appears to exhibit conditional dormancy (CD), with delayed germination under suboptimal conditions. Seeds germinated readily at 15/2 and 25/5 °C, but were substantially delayed under 5/1 °C. However, after four weeks at 5/1°C, germination percentages significantly increased, particularly under light, suggesting that Smith fir seeds may exhibit conditional dormancy, and cold exposure acts as a stratification cue for dormancy release. Cold-induced dormancy release has been reported in many of other alpine species, including

Primula [

33] and

Jeffersonia dubia [

34]. These findings highlight an adaptive germination strategy of Smith fir that enables seedling establishment under the harsh conditions of high-altitude subalpine environments.

3.4. Ecological Role of Seed Wings in Germination

Although the role of seed appendages in regulating germination has been extensively studied in angiosperms [

13,

16,

35,

36], investigations into the functional role of seed wings in gymnosperms remain limited. Seed wings, a characteristic of many gymnosperms, have been shown to influence germination dynamics, yet their exact role remains poorly understood. Our findings demonstrates that seed wings significantly inhibit germination, as both intact and mixed seed treatments exhibited lower germination rates compared to de-winged seeds (

P < 0.001;

Figure 6). No significant difference was observed between intact and mixed seeds, both of which showed significantly lower germination percentages than de-winged seeds (

P < 0.001;

Figure 7). This suggests that the inhibitory effect of seed wings may be due to the presence of germination inhibitors within the wings, which may reduce seed germinability.

This mechanism aligns with in other species where seed apendages play a similar inhibitory role through mechanical barriers or inhibitory compounds[

37,

38]. For example, in

Welwitschia mirabilis, persistent desiccated bracts surrounding the seeds have been found to suppress germination, and their removal accelerates seed germination[

39]. Similarly, in our study, intact seeds displayed relatively low germination percentages in controlled conditions (

Figure 4), suggesting that in addition to dormancy-related constraints, seed wings may play a direct role in regulating germination timing.

The role of seed appendages varies according to plant biology and the ecological environment. In arid environments, structures such as pappi or pubescence promote rapid water uptake, facilitating germination under moisture-limited conditions [

40,

41]. In contrast, thick seed wings or impermeable seed coats act as physical or chemical barriers that delay germination by restricting water imbibition or releasing inhibitory compounds, particularly under ecologically unfavorable conditions[

42,

43]. These contrasting mechanisms reflect diverse adaptive strategies plants use to optimize germination timing across variable environments.

In the case of Smith fir, seed wings effectively prevent germination during the warm autumn, while conditional dormancy ensures that germination dos not occur prematurely during the cold winter. As temperatures rise and snow melts, seed wings soften and decompose, reducing their inhibitory effects., This, in turn, allows germination to occur as soil moisture and nutrient availability increase, creating favorable conditions for seedling establishment[

44].This integrated germination strategy ensures that germination is synchronized with optimal spring conditions, enhancing seedling survival.

3.5. Integration of Temperature, Light, and Seed Wings in Regulating Germination Timing

The interaction between temperature and light is pivotal in regulating seed germination, with light acting as a key environmental cue under low-temperature conditions. The inhibitory effects of seed wings prevent germination in autumn, while Smith fir seeds likely require winter chilling to break dormancy. Together, these factors—temperature, light, and seed wings—precisely regulate germination timing, ensuring that seedling emergence occurs under optimal spring conditions.

Despite the insights gained from this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. Laboratory-based germination experiments may not fully capture the complexity and variability of natural alpine environments. Furthermore, the physiological and biochemical mechanisms underlying seed wing-mediated inhibition remain largely unexplored. Future research should combine field-based investigations with detailed physiological and biochemical analyses to more thoroughly elucidate the role of seed appendages in regulating germination and facilitating ecological adaptation in high-altitude ecosystems.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

Seed collection was conducted in the Sygera Mountains, Nyingchi Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region (29°10′ N – 30°15′ N, 93°12′ E – 95°35′ E), at elevations ranging from 3200 to 4728 m. The region is features by a subalpine, cold-temperate, semi-humid climate, represents the typical habitat of Smith fir.

4.2. Seed Collection

Seeds were collected in late October 2023 from 30 reproductively mature, healthy Smith fir trees, randomly selected within a natural forest stand. To minimize the genetic similarity, trees were spaced at least 50 m apart. Mature cones were harvested using a pole pruner from sun-exposed branches to ensure the collection of physiologically mature seeds.

4.3. Seed Extraction

Cones were air-dried at room temperature (ca. 15°C) for 10 days to promote natural seed dehiscence. Once opening, seeds were manually extracted by gently shaking and tapping the cones. Debris, cone scales, and damaged seeds were removed by hand. Approximately 2000 seeds were collected and stored under cool, dry conditions until germination experiments in November 2023.

4.4. Seed Morphological Characteristics

The length and width of intact and de-winged seeds were measured using a vernier caliper (0.01 mm precision). Fifty seeds per treatment were measured for three replicates, and the results were averaged. Seed weight was determined as the mass of 1000 seeds using an analytical balance (0.0001 g precision). One thousand seeds per replicate were randomly selected, and the measurement was repeated three times to obtain the average weight.

4.5. Effect of Temperature and Light on Seed Germination

To assess the impact of temperature and light on seed germination, seeds were incubated under three alternating temperature regimes: 5/1 °C (representing October and May), 15/2 °C (June and September), and 25/5 °C (July to August), reflecting the daily mean maximum and minimum temperatures during the growing season at the study site [

45]. For each temperature regime, two light conditions were tested: a 12h light/12h darkphotoperiod (simulating spring to autumn conditions), and continuous darkness (simulating low-light environments such as snow or forest litter). Petri dishes forthe dark treatment were wrapped in aluminum foil to block light. Seeds were placed in 60 mm Petri dishes lined with two layers of moistened filter paper. Each treatment had four replicates of 25 seeds. Germination, defined as radicle emergence, was monitored weekly for a period of eight weeks.

4.6. Effect of Seed Wings on Germination

To evaluate the effect of the seed wing, three different treatments were applied: intact seeds, mixed seeds (wings removed and mixed with the seeds ), and de-winged seeds. Seeds were placed in 60 mm Petri dishes with two layers of moistened filter paper, and incubated under an alternating temperature regime of 25/5 °C (12 h light/12 h dark). Each treatment included four replicates of 25 seeds, and germination was monitored weekly as described above.

Mean germination time (MGT) was calculated using the formula from Ellis & Roberts [

46]:

where n is the number of seeds that germinate on the D-th day, and D is the number of days counted from the beginning of germination.

5. Conclusions

This study elucidates the mechanisms by which Smith fir seeds regulate germination timing through interactions between environmental cues and intrinsic traits. Germination is governed by conditional physiological dormancy that is released by exposure to low temperatures and influenced by light availability, while wing-associated chemical inhibitors impose additional constraints. The integration of these physiological and morphological mechanisms ensures that germination occurs under favorable spring conditions, thereby enhancing seedling establishment in high-altitude subalpine forests. Collectively, these findings highlight how dormancy regulation and seed morphology interact to shape regeneration strategies of conifers in cold mountain environments.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 31860123 and 31560153, and the Ecological Monitoring Project of Huaneng Tibet Yarlung Zangbo River Hydropower Development Investment Co., Ltd., grant number JC2022/D01.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all those who helped with this study and to the research projects that sponsored it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bertram, C.; Riahi, K.; Hilaire, J.; Bosetti, V.; Drouet, L.; Fricko, O.; Malik, A.; Nogueira, L.P.; van Der Zwaan, B.; van Ruijven, B.; et al. Energy System Developments and Investments in the Decisive Decade for the Paris Agreement Goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 074020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emer, C.; Jordano, P.; Pizo, M.A.; Ribeiro, M.C.; da Silva, F.R.; Galetti, M. Seed Dispersal Networks in Tropical Forest Fragments: Area Effects, Remnant Species, and Interaction Diversity. Biotropica 2019, 52, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd edition.; Elsevier/AP: San Diego, CA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-416677-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, M.; Thompson, K. The Ecology of Seeds. Austral Ecol. 2006, 31, 545–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. The Great Diversity in Kinds of Seed Dormancy: A Revision of the Nikolaeva-Baskin Classification System for Primary Seed Dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2021, 31, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed Dormancy and the Control of Germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, C.G.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M.; Auld, J.R.; Venable, D.L.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Donohue, K.; Rubio De Casas, R.; The NESCent Germination Working Group. The Evolution of Seed Dormancy: Environmental Cues, Evolutionary Hubs, and Diversification of the Seed Plants. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, M.; Nakayama, N. From Passive to Informed: Mechanical Mechanisms of Seed Dispersal. New Phytol. 2019, 225, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Zammouri, J.; Gorai, M.; Neffati, M. Ecological Role of Bracteoles in Seed Dispersal and Germination of the North African Halophyte Atriplex Mollis under Contrasting Environments. Bot. Lett. 2019, 166, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Lu, J.J.; Baskin, C.C.; Tan, D.Y.; Wang, L. Diaspore Dispersal Ability and Degree of Dormancy in Heteromorphic Species of Cold Deserts of Northwest China: A Review. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 16, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, E.; Westoby, M.; Nelson, D. Diaspore Weight, Dispersal, Growth Form and Perenniality of Central Australian Plants. J. Ecol. 1991, 79, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lukic, N.; Pagel, J.; Schurr, F.M. Density Dependence of Seed Dispersal and Fecundity Profoundly Alters the Spread Dynamics of Plant Populations. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 1735–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torices, R.; DeSoto, L.; Cerca, J.; Mota, L.; Afonso, A.; Poyatos, C. Fruit Wings Accelerate Germination in Anacyclus Clavatus. Am. J. Bot. 2024, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, A.; Santo, A.; Gallacher, D. Seed Mucilage Effect on Water Uptake and Germination in Five Species from the Hyper-Arid Arabian Desert. J. Arid. Environ. 2016, 128, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Jiang, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Wen, Z. Seed Germination Response and Tolerance to Different Abiotic Stresses of Four Salsola Species Growing in an Arid Environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 892667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhaichi, M.; Hassan, S.; Missaoui, A.M.; Ates, S.; Petersen, S.L.; Niane, A.A.; Slim, S.; Belgacem, A.O. Impacts of Bracteole Removal and Seeding Rate on Seedling Emergence of Halophyte Shrubs: Implications for Rangeland Rehabilitation in Arid Environments. Rangeland J. 2019, 41, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, L.; Li, J.; Bai, S.; Teng, Y.; Hui, W. Seed Coat-Derived ABA Regulates Seed Dormancy of Pyrus Betulaefolia by Modulating ABA and GA Balance. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1667946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yan, L.; Li, C.; Xia, Q.; Zhuo, X.; Zhao, B. Morphological Characteristics and Wind Dispersal Characteristics of Samara of Common Acer Species. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University:Natural Sciences Edition 2021, 45, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Armenise, L.; Simeone, M.C.; Piredda, R.; Schirone, B. Validation of DNA Barcoding as an Efficient Tool for Taxon Identification and Detection of Species Diversity in Italian Conifers. Eur. J. Forest Res. 2012, 131, 1337–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskorbin, P.A.; Bugaeva, K.S. Dynamics of Plant Communities in Insular Pine Forests of Krasnoyarsk Forest-Steppe. Russ. J. Ecol. 2013, 44, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X. Taxonomy and Distribution of Global Gymnosperms; Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House, 2017; ISBN 978-7-5478-3328-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Lin, L.; Pan, G. Soil Seed Bank Characteristic of Smith Fir in Sejila Mountain,Tibet. Journal of Northeast Forestry University 2008, 36, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzyszewska, K.; Chłanda, J. A Study on the Variation of Morphological Characteristics of Silver Fir (Abies Alba Mill.) Seeds and Their Internal Structure Determined by X-Ray Radiography in the Beskid Sądecki and Beskid Niski Mountain Ranges of the Carpathians (Southern Poland). J. For. Sci. 2009, 55, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veli̇Oğlu, E.; Tayanç, Y.; Çengel, B.; Kandemir, G. Genetic Variability of Seed Characteristics of Abies Populations from Turkey. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Alvarez, M.; Donohue, K.; Ge, W.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.; Du, G.; Bu, H. Elevation Filters Seed Traits and Germination Strategies in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Ecography 2020, 44, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, S.V.; Hulme, P.E. Limited Evidence for a Consistent Seed Mass-Dispersal Trade-off in Wind-Dispersed Pines. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarpaas, O.; Silverman, E.J.; Jongejans, E.; Shea, K. Are the Best Dispersers the Best Colonizers? Seed Mass, Dispersal and Establishment in Carduus Thistles. Evol. Ecol. 2010, 25, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D.M. Alpine Treelines: Functional Ecology of the Global High Elevation Tree Limits. Arct., Antarc., Alp. Res. 2013, 45, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Yang, X.; Cui, G.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, Q. Smith Fir Population Structure and Dynamics in the Timberline Ecotone of the Sejila Mountain, Tibet, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2007, 27, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, L.O.; McDonald, M.B. Principles of Seed Science and Technology; Chapman and Hall: New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Peng, D.; Li, Z.; Huang, L.; Yang, J.; Sun, H. Cold Stratification, Temperature, Light, GA3, and KNO3 Effects on Seed Germination of Primula Beesiana from Yunnan, China. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walck, J.L.; Hidayati, S.N. Differences in Light and Temperature Responses Determine Autumn versus Spring Germination for Seeds of Schoenolirion Croceum. Can. J. Bot. 2004, 82, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, Z. Seed Dormancy and Soil Seed Bank of the Two Alpine Primula Species in the Hengduan Mountains of Southwest China. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 582536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhie, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.S. Seed Dormancy and Germination in Jeffersonia Dubia (Berberidaceae) as Affected by Temperature and Gibberellic Acid. Plant Biol. 2014, 17, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Wen, Z. Interactions between Fruiting Perianth and Various Abiotic Factors Differentially Affect Seed Germination of Salsola Brachiata. Flora 2022, 290, 152057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, I.A.; Khan, M.A. Effect of Bracteoles on Seed Germination and Dispersal of Two Species of Atriplex. Ann. Bot. 2001, 87, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.; Bhat, N.R.; Lozano-Isla, F.; Gallacher, D.; Santo, A.; Batista-Silva, W.; Fernandes, D.; Pompelli, M.F. Germination Asynchrony Is Increased by Dual Seed Bank Presence in Two Desert Perennial Halophytes. Botany 2019, 97, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeno, K.; Yamaguchi, H. Diversity in Seed Germination Behavior in Relation to Heterocarpy inSalsola Komarovii Iljin. J. Plant Res. 1991, 104, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, C.; Berjak, P.; Kolberg, H.; Pammenter, N.W.; Bornman, C.H. Responses to Various Manipulations, and Storage Potential, of Seeds of the Unique Desert Gymnosperm, Welwitschia Mirabilis Hook. Fil. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2004, 70, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, W.; Erickson, T.E.; Dixon, K.W.; Stevens, J.C. Increasing the Germination Envelope under Water Stress Improves Seedling Emergence in Two Dominant Grass Species across Different Pulse Rainfall Events. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 54, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.; Iannetta, P.; Binnie, K.; Valentine, T.A.; Toorop, P. Myxospermous Seed-Mucilage Quantity Correlates with Environmental Gradients Indicative of Water-Deficit Stress: Plantago Species as a Model. Plant Soil 2019, 446, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Herrera, C.; Beardmore, T.; Loo, J. Overcoming Dormancy of Pinus Pinceana Seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 2008, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. Evolutionary Considerations of Claims for Physical Dormancy-Break by Microbial Action and Abrasion by Soil Particles. Seed Sci. Res. 2000, 10, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Hameed, A.; Gul, B.; Khan, M.A. Perianth and Abiotic Factors Regulate Seed Germination of Haloxylon Stocksii— a Cash Crop Candidate for Degraded Saline Lands. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J; Luo, T; Xu, Y. Characteristics of Eco-Climate at Smith Fir Timberline in the Sergyemla Mountains,Southeast Tibetan Plateau. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2009, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.A.; Roberts, E.H. The Quantification of Ageing and Survival in Orthodox Seeds. Seed Science and Technology 1981, 9, 373–409. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).