Introduction

Reading plays a central role in social, educational, and economic development. It shapes language acquisition, academic achievement, employment prospects, civic participation, and social cohesion. A substantial body of evidence highlights the power of reading and being read to: language development is strongly predictive of long-term educational and economic outcomes (Krashen, 2004), reading for pleasure improves achievement independent of socioeconomic status (Evans et al., 2010; Kirsch et al., 2002; Sullivan & Brown, 2013), and reading cultivates empathy, imagination, and critical thinking (Koopman & Hakemulder, 2015). Understanding whether, how, and why South Africans read is therefore central to the country’s wider developmental trajectory.

Yet South Africa faces a persistent reading challenge. International assessments show that most children cannot read for meaning by age ten (Mullis et al., 2023), while adult reading practices are seldom measured or publicly debated. Although there is a widespread perception that South Africans “do not read enough” (Biesman-Simons, 2021), there has been no coordinated view of the broader system that shapes reading ability, access, and motivation. Reading takes place within an ecosystem of formal and informal institutions that influence individuals’ opportunities and choices, but until recently this ecosystem had not been synthesised into a coherent national picture.

A small body of work has attempted to conceptualise literacy and reading as outcomes of interacting social and institutional systems rather than as individual competencies alone. At the global level, UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Reports synthesise institutional data across education policy, financing, language of instruction, and inequality to examine conditions shaping learning outcomes, including literacy, though reading itself is not their primary focus (UNESCO, 2023). Similarly, the OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) extends literacy measurement beyond schooling into adult life, situating reading skills within labour-market participation and lifelong learning systems, while remaining largely skills-oriented (OECD, 2016). Policy-mapping approaches such as the World Bank’s Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) further demonstrate how governance, accountability, and institutional coherence shape learning outcomes, even where literacy is treated indirectly (World Bank, 2011, 2014). More reading-specific ecosystem perspectives are evident in analyses by the Global Book Alliance, which emphasise the interdependence of content creation, publishing, language availability, distribution, and affordability in enabling reading cultures (Global Book Alliance, 2020). Within South Africa, barometer-style approaches such as the Indlulamithi Social Cohesion Barometer illustrate how composite indicators derived from institutional data can make complex social systems legible to both policymakers and the public (Indlulamithi Trust, 2017, 2019). Collectively, these efforts demonstrate growing recognition that literacy outcomes are shaped by system-level conditions; however, few provide a dedicated, reading-specific synthesis that integrates ability, access, motivation, and governance within a single national framework.

The National Reading Barometer (NRB) was developed in 2022–2023 as one of the few national attempts to synthesise institutional data across reading ability, access, motivation, and governance in South Africa. The NRB compiles and interprets existing institutional data to map what enables or constrains reading across the country. Alongside the National Reading Survey (Polzer Ngwato et al., 2023), the NRB offers a system-level view of reading in South Africa. The 2023 iteration establishes a baseline for future cycles in 2026 and 2030.

The NRB is grounded in the idea that reading cultures emerge not only from individual choices but from a broader environment shaped by literacy ability, access to relevant reading materials, and motivation to read. By synthesising uncontested data, presenting it in accessible formats, and building shared understanding among stakeholders, the Barometer aims to strengthen relationships across the ecosystem, create common frames for debate, and support coordinated action.

This paper describes the conceptual foundations and development of the National Reading Barometer, including its system boundaries, measures, theory of change, and stakeholder co-design processes. It considers how the Barometer may be applied to interpret institutional dynamics relevant to reading at a national level.

Method

Conceptual approach

A barometer is an advocacy and awareness-raising tool that tracks trends in a social A barometer is an advocacy and awareness-raising tool that tracks trends in a social phenomenon over time. Its core function is to support collective action across a wide range of agencies and decision-makers who share broadly defined interests but lack formal mechanisms for negotiating common goals, clarifying responsibilities, or holding one another accountable. In complex systems without an overarching authority, coordination depends on voluntary engagement, dialogue, and shared interpretations of system-level problems. A barometer contributes to this process by setting the parameters of debate through shared, uncontested information.

To perform this function, a barometer must establish clear system boundaries and parameters, simplify complex information, draw on uncontested and credible data, use accessible visualisations, represent current system status, enable comparison against agreed or uncontested benchmarks, and allow for tracking over time. These principles guided the development of the South African National Reading Barometer (NRB).

A key boundary decision in the NRB was to broaden the focus of national discussions on reading beyond childhood to include adult reading. This reframes reading as a lifelong practice and brings institutions such as public libraries and the National Library of South Africa into view as central actors within the reading system, alongside schools and early childhood services.

Reading ecosystem

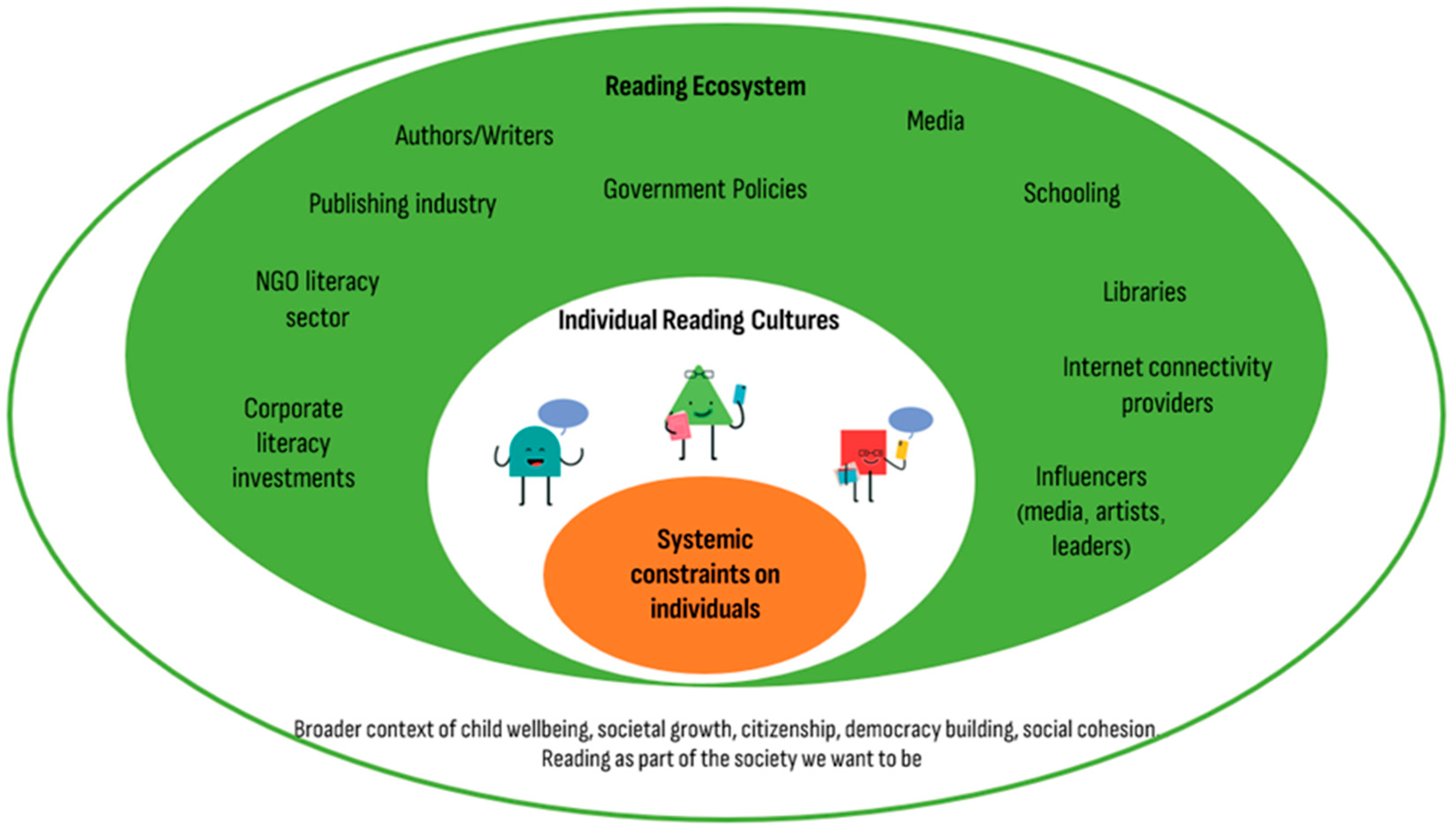

The South African reading ecosystem is defined as the constellation of formal and informal institutions that shape reading ability, access, motivation, and practices. Conventional discussions of South Africa’s “reading culture” often implicitly define readers as individuals who regularly read printed books and own books in their homes. The NRB adopts a broader definition of reading that reflects a multilingual, digital, and resource-constrained context. This includes reading in multiple languages, digital reading, reading for communication, and engagement with a wide range of materials such as newspapers, religious texts, online content, and shared or freely available materials.

Under this definition, reading cultures are understood as emergent outcomes of both individual circumstances and choices and the wider reading environment in which those choices are made.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between individual readers, their socio-economic constraints, and the institutional environment that creates incentives and barriers to reading.

Data Selection and Construction Process

he NRB synthesises existing institutional data rather than generating new primary data. Measures were selected to represent key parameters of the reading ecosystem while remaining manageable for interpretation and use by system actors. Approximately 50 measures were considered an appropriate balance between analytical coverage and usability; the NRB comprises 55 measures.

To simplify a complex system, measures were organised into four analytical dimensions informed by a high-level theory of change: reading ability; reading materials access; institutional framework; and motivation and practice. Structuring into four dimensions enables diverse indicators to be interpreted collectively while retaining visibility of different system components.

Each measure is supported by a specific institutional data source that operationalises the underlying concept and is sufficiently credible and stable to allow repetition over time. Where important aspects of the ecosystem lacked adequate or repeatable data, placeholder measures were included to signal priorities for improved data collection in future iterations. The focus on existing institutional data supports legitimacy by ensuring that system actors recognise their own data within the Barometer and limits disputes over validity.

Evaluative framework

ach measure in the NRB is assigned an evaluative judgement using a three-level rubric: enabling, emerging, or constraining. This approach is widely used in composite indicators and barometers, including the Social Progress Imperative (Social Progress Imperative, 2022) and the Indlulamithi Social Cohesion Barometer (Indlulamithi Trust, 2017; 2019), to support comparative interpretation across system components rather than to assess the performance of individual institutions.

Cut-off points for these categories were determined through a combination of:

comparisons with upper- and lower-middle-income countries;

targets set by the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture and the Department of Basic Education;

expert assessments from institutional data owners; and

equity considerations, including geographic and socioeconomic distribution.

Where competing benchmarks existed, final classifications were agreed through consultation with institutional stakeholders, ensuring that evaluative judgements were presented as uncontested and legitimate. The example of the number of public libraries per population illustrates how data limitations, outdated targets, international variation, and stakeholder input collectively informed evaluative judgement.

Barometers necessarily simplify complex measures. Although this obscures some contextual variation—for example, differences in ideal library-to-population ratios by population density—measures are interpreted within the wider ecosystem rather than used as stand-alone decision tools. This level of abstraction is therefore appropriate and necessary. Evaluative judgements allow measures to be aggregated descriptively to provide an overall profile of system conditions without applying weights or inferring causal relationships.

Theory of Change

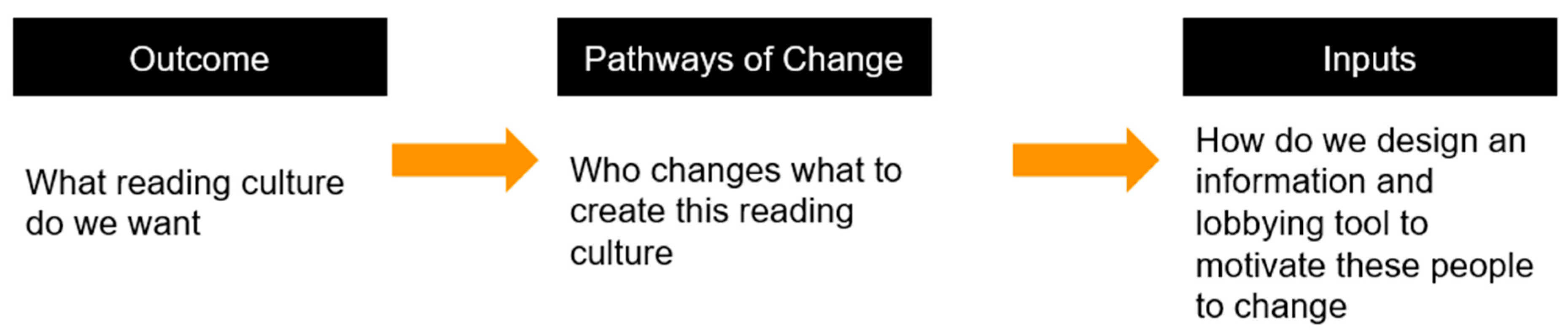

The NRB was guided by a theory of change that articulates hypothesised pathways through which an informational tool may interact with existing system dynamics. Theories of change describe how strategies are expected to connect to intermediate outcomes and longer-term goals (Harris, 2005). For the NRB, this involved working backwards from the desired state of a more enabling reading ecosystem to identify potential levers of change, relevant actors, and inputs required to motivate action (Coffman & Beer, 2015).

Figure 2 illustrates the back-solving process used to identify a barometer as an appropriate methodological response to the problem of coordinating action within a complex reading ecosystem.

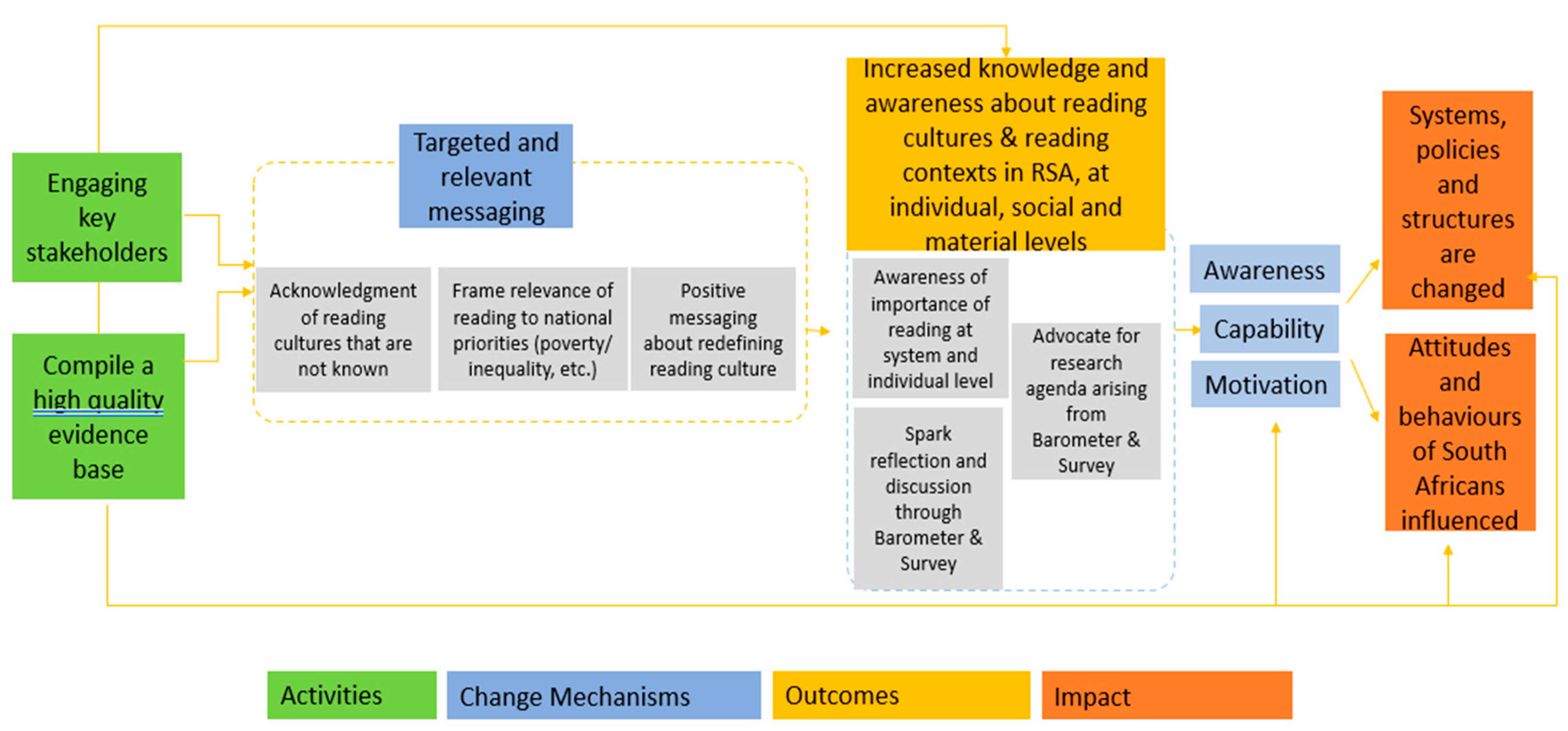

As an informational tool, the NRB defines system parameters and reports current status. Evidence from advocacy research indicates that information alone is rarely sufficient to prompt action (Coffman & Beer, 2015). The NRB theory of change therefore combines information provision with structured stakeholder engagement, positing that evidence and relationships must operate together.

The NRB theory of change (

Figure 3) articulates how these components are expected work together. It emphasises that both the evidence base and the relational component are essential. The Barometer does not act directly on the reading ecosystem; rather, it is intended to equip and motivate influential actors who are positioned to effect change within their respective areas of responsibility.

Stakeholder Co-Design

Stakeholder engagement was integral to the NRB’s methodological design. The project was implemented as a multi-sectoral, collaborative process involving stakeholders from government, charitable organisations, literacy NGOs, publishing, and community groups. A 16-member Steering Committee guided measure selection and interpretation, supported by a broader consultative reference group. Final data points and evaluative judgements were validated through consultation with institutional data owners, including the Department of Basic Education, the National Library of South Africa, the Publishers’ Association of South Africa, DataDrive2030, the Literacy Association of South Africa, and civil society organisations involved in distributing free reading materials.

The NRB was designed to complement rather than replace existing national initiatives by providing shared information and a common analytical framing.

Communication and Application

As part of the methodological design, communication outputs were tailored to different stakeholder groups, recognising that audiences engage with evidence through different formats. Outputs included a technical report, a video, media and social media materials, conference presentations, targeted engagements with policymaker forums, and tailored briefs for libraries, institutions working with children, and producers of reading materials.

These communication products were designed to support stakeholder engagement with the Barometer by facilitating understanding of the reading ecosystem and by providing a shared language for interpreting system-level conditions. The approach emphasised the provision of information, framing, and platforms for dialogue intended to support stakeholders’ capacity to reflect on their roles within the ecosystem, drawing on established advocacy practice (Zhou & Shilakoe, 2022).

The longitudinal design of the Barometer enables repeated dissemination of comparable outputs over time, allowing subsequent iterations to be used to examine changes in system conditions and to contextualise ongoing advocacy and institutional activity.

Results

The constructed National Reading Barometer (NRB) comprises 55 measures drawn from existing institutional data. Some measures are conventional indicators of reading outcomes and access, such as the percentage of Grade 4 learners who can read for meaning or the proportion of households with any fiction or non-fiction books. Others are less conventional, including the percentage of educational publications produced in African languages and the cost of 1 GB of mobile data relative to the global median. Together, these measures reflect both established and emerging conditions shaping reading within the national ecosystem.

The Barometer is organised into four dimensions:

Reading ability (8 measures): early literacy, primary school reading outcomes, youth literacy, and adult literacy levels;

Reading materials access (18 measures): book ownership, access through libraries, publishing industry outputs, free reading material distribution, and digital access;

Institutional framework (19 measures): the policy environment, investment in reading (government budgets and private sector funding), and the education system’s capacity to teach reading;

Motivation and practice (10 measures): the extent to which adults self-identify as readers, regularly read for enjoyment and information, read books, and read with children.

Each dimension includes multiple measures capturing different aspects of that domain. For example, the Reading Materials Access dimension includes measures relating to access through libraries, the publishing industry, school-based reading materials, and online content.

Measures are supported by specific institutional data sources that operationalise the underlying concepts. For instance, the number of non-serial items deposited with the National Library of South Africa, in its role as a statutory legal deposit institution, serves as the datapoint for a measure representing new publications produced by South African authors and publishers.

One example of an evaluative judgement in the NRB is the measure of public libraries per population. In 2022, South Africa had 1 934 public libraries for a population of approximately 60.6 million, equivalent to one library per 31 000 people. Interpretation of this figure drew on available reference points, including background research conducted in 2013 to inform the costing of proposed Norms and Standards for public libraries (Cornerstone, 2013) and international library-to-population ratios reported by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, as well as figures for Latin America and the Caribbean, the United Kingdom, and the United States (NRB, 2023a). In the absence of a definitive benchmark, this measure was classified as emerging through consultation with a representative of the National Library of South Africa, and the categorisation was presented as uncontested within the public Barometer.

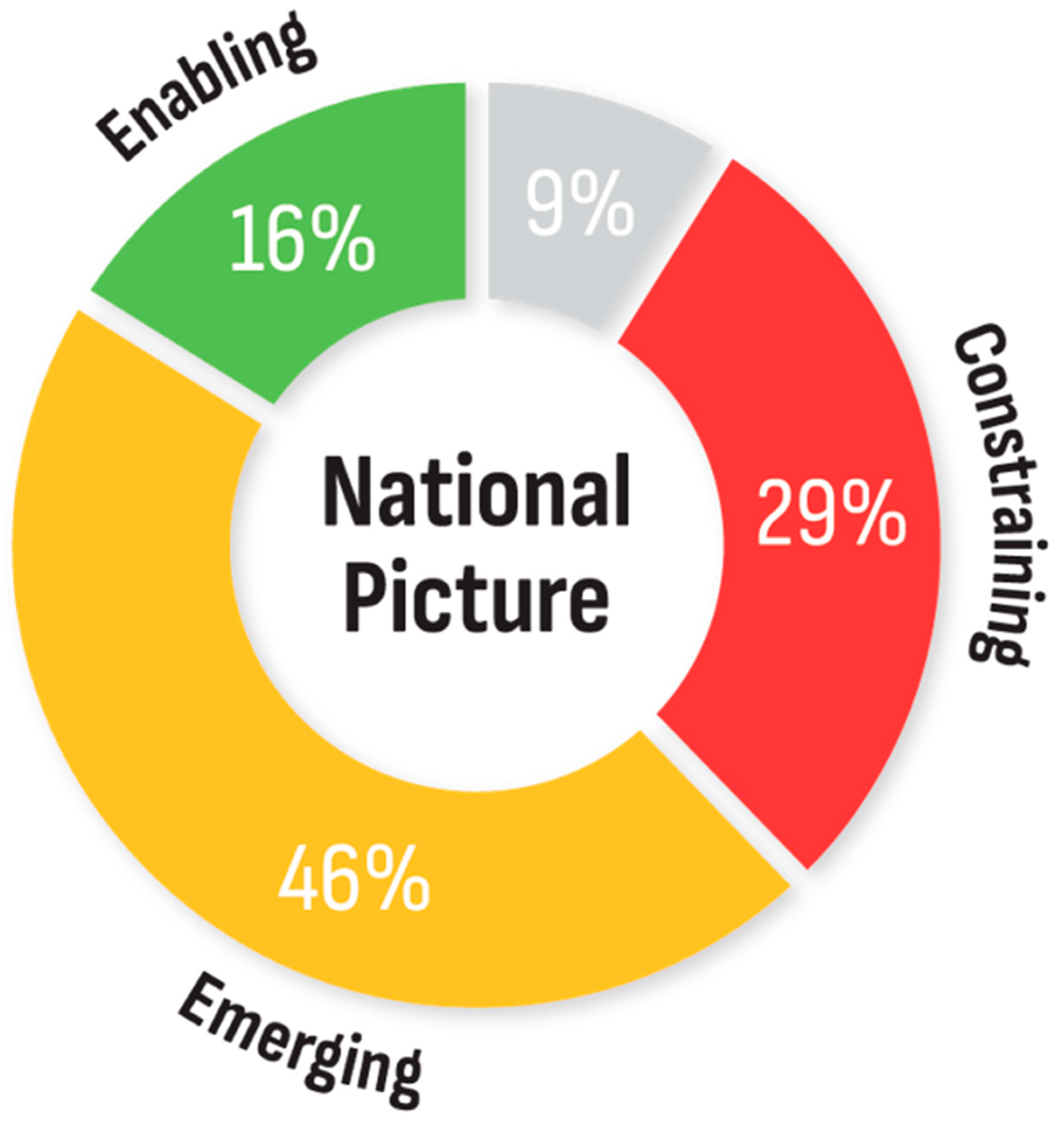

Figure 4 presents the aggregated profile of the South African reading ecosystem for the 2023 baseline. Overall, 46% of measures were classified as emerging, 29% as constraining, and 16% as enabling, indicating that the national reading ecosystem is predominantly characterised by emerging conditions alongside a substantial number of constraining factors.

Some measures for interesting aspects of the reading ecosystem were excluded because data was either not available, was only available as a one-time sample (not longitudinal into the future), or would have required compilation and analysis from multiple sources. Some such measures are included as ‘grey’ in the current Barometer as they were considered sufficiently important to the ecosystem to warrant recommendations for improvements in data collection or collation by the system and therefore ‘placeholder’ status for inclusion in future iterations of the Barometer.

Discussion

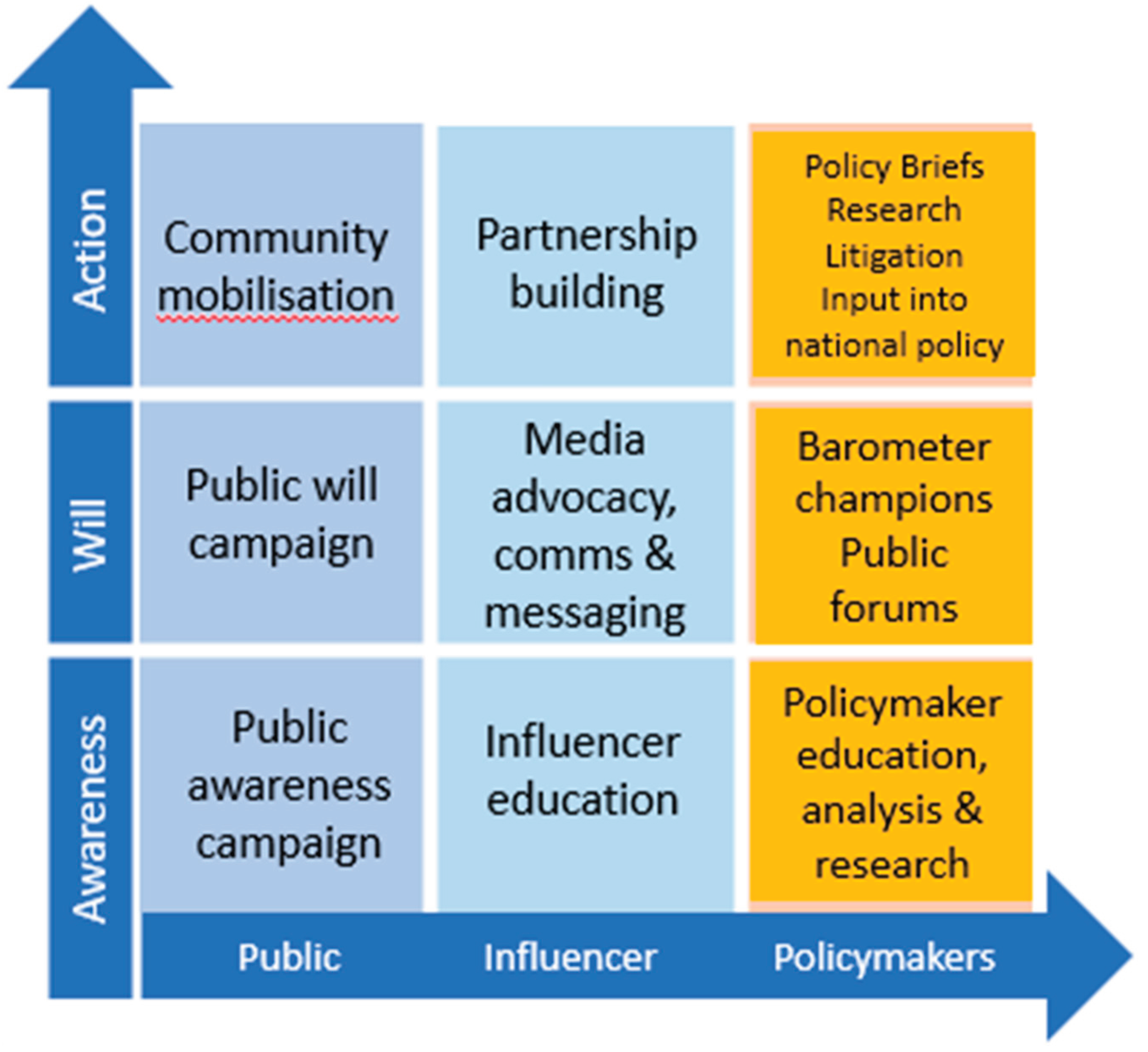

Effective advocacy requires targeted engagement with different audiences and clarity about the types of change sought. Drawing on Coffman and Beer’s (2015) advocacy framework, adapted in

Figure 5, the National Reading Barometer (NRB) focuses on three forms of change—awareness, will, and action—across three primary audience groups: the general public, influencers, and policymakers.

In the public arena, the Barometer can raise awareness of how reading contributes to individual and national development, while also identifying specific system constraints that require attention. For example, although 58% of South Africans report access to a community library, only 8% borrow books, and six of the twelve library-related measures were categorised as constraining in 2023. These patterns highlight the gap between infrastructure and use, and indicate where public-facing interventions are most needed. Public will can be strengthened by reframing libraries not as supplementary services but as central components of an enabling reading ecosystem. Public action may take the form of community mobilisation, including encouraging adults to read with children and supporting caregivers to use libraries as shared reading spaces. In this respect, the increase in adults reporting that they read with children, from 35% in 2016 to 52% in 2023, suggests shifting norms that can be reinforced through targeted advocacy.

Among influencers such as authors, sportspeople, religious leaders, media figures, and others shaping public discourse; the NRB supports awareness-raising by making visible how cultural leadership and everyday messaging can influence reading motivation. Targeted communication based on Barometer findings can help influencers recognise their role in normalising reading and promoting inclusive reading identities. Influencer action may include partnerships between libraries and community institutions, joint outreach activities, and storytelling or media campaigns that celebrate reading across languages, ages, and formats.

In the policy arena, the Barometer provides a consolidated and credible evidence base that can inform planning, accountability, and system strengthening. Policy awareness can be supported by integrating NRB findings into academic programmes, postgraduate training, and policy-forum discussions. Will can be strengthened as provincial and national library leaders use Barometer evidence to champion reading in public forums and convene multi-stakeholder conversations about system-level constraints. The NRB’s identification of persistent challenges—such as limited availability of African-language materials, high data costs, and uneven library resourcing—provides policymakers with concrete targets for intervention.

Policy action includes implementing recommendations arising from the Barometer (NRB 2023a; NRB 2023b), such as finalising the Libraries and Information Systems Bill, approving minimum Norms and Standards, improving procurement processes for reading materials, and expanding investment in public library infrastructure. The Barometer’s indicators can be incorporated into government planning and performance frameworks, enabling sector leaders to monitor progress and respond to emerging trends. Special issue briefs, including those focused on libraries and children (Polzer Ngwato 2023b), offer tailored analytical products that can be embedded within planning cycles and monitoring instruments.

Policy action includes implementing recommendations arising from the Barometer (NRB 2023a; NRB 2023b), such as finalising the Libraries and Information Systems Bill, approving minimum Norms and Standards, improving procurement processes for reading materials, and expanding investment in public library infrastructure. The Barometer’s indicators can be incorporated into government planning and performance frameworks, enabling sector leaders to monitor progress and respond to emerging trends. Special issue briefs, including those focused on libraries and children (Polzer Ngwato 2023b), offer tailored analytical products that can be embedded within planning cycles and monitoring instruments.

Conclusion

Effective advocacy requires clarity about both the audiences being engaged and the forms of change sought. The National Reading Barometer provides a structured way to support system-level change by strengthening awareness, will, and action across the public, influencer, and policy arenas. By offering a shared evidence base and common language, the Barometer enables stakeholders to recognise constraints within the reading ecosystem and to identify opportunities for coordinated response.

Rather than acting as an intervention in itself, the Barometer functions as an enabling resource. It supports public engagement with reading, helps influencers recognise and exercise their role in shaping reading cultures, and provides policymakers with credible information to guide planning, accountability, and reform. Through this combination of evidence, relationships, and longitudinal tracking, the Barometer offers a practical approach to fostering more enabling reading environments and strengthening reading ecosystems over time.

Acknowledgments

Katherine Morse was co-PI of the National Reading Barometer project within Nal’ibali; along with Katie Huston. Tara Polzer Ngwato led the Barometer co-design process. Contributors to the co-design process included Tendayi Zhou and Lebogang Shilakoe of Social Impact Insights and National Reading Barometer Steering Committee members Nqabakazi Gina (Nal’ibali), Bafana Mtini (Khutsong Literacy Club), Catherine Langsford/Nadeema Musthan (LITASA), Dorothy Dyer (FunDza), Heleen Hofmeyr (RESEP), Janita Low (Independent), Kentse Radebe (DGMT), Kulula Manona (DBE), Lauren Fok (Zenex Foundation), Lorraine Marneweck (NECT), Nazeem Hardy (LIASA), Nokuthula Musa (NLSA), Nqabakazi Gina (Nal’ibali), Ntsiki Ntusikazi (Wordworks), Smangele Mathebula (SAIDE), Stanford Ndlovu (Jakes Gerwel Fellowship) and Takalani Muloiwa (WITS University).

Declaration of AI Use

Artificial intelligence tools were used to support language editing, structural refinement, and clarity of expression during the manuscript preparation process. All substantive intellectual contributions—including study design, conceptualisation, analysis, interpretation, and final editorial decisions—were made by the author(s). The authors take full responsibility for the content of the manuscript.

| 1 |

Graphic source (NRB 2023). |

| 2 |

Figure source: NRB 2022 Presentation. |

| 3 |

Figure adapted from NRB 2022 Presentation. |

| 4 |

Graphic source (NRB 2023a). |

| 5 |

Figure adapted from The Advocacy Strategy Framework- Centre for Evaluation Innovation (Coffman & Boer, 2015). |

References

- Biesman-Simons, C. (2021). Tracing the usage of the term ‘culture of reading’ in South Africa: A review of national government discourse (2000–2019). Reading & Writing, 12(1), 9 pages. [CrossRef]

- Coffman, Julia and Tanya Beer (2015) The Advocacy Strategy Framework: A tool for articulating an advocacy theory of change. Center for Evaluation Innovation.

- Cornerstone Economic Research, 2013, Costing the South African Public Library and Information Services Bill, report for Department of Arts and Culture, South Africa.

- Evans, M. D., Kelley, J., Sikora, J., & Treiman, D. J. (2010). Family scholarly culture and educational success: Books and schooling in 27 nations. Research in social stratification and mobility, 28(2), 171-197.

- Harris, E. (2005). An introduction to theory of change. The Evaluation Exchange, 11(2), p.12, 19.1. Available at http://www.gse.harvard.edu/hfrp/eval/issue30/expert3.html.

- Kirsch, Irwin S.; de Jong, John; LaFontaine, Dominique; McQueen, Joy; Mendelovits, Juliette; Monseur, Christian (2002) Reading for Change: Performance and Engagement Across Countries: Results from PISA 2000 PISA OECD IALS, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Report.

- Koopman, Emy & Hakemulder, Frank. (2015). Effects of Literature on Empathy and Self-Reflection: A Theoretical-Empirical Framework. Journal of Literary Theory. 9. 79-111. [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S. D. (2004). The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research (2nd ed.). Heinemann, and Libraries Unlimited.

- Mullis, I.V.S., von Davier, M., Foy, P., Fishbein, B., Reynolds, K.A., & Wry, E. (2023). PIRLS 2021 International Results in Reading. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. [CrossRef]

- National Reading Barometer (2022) National Reading Barometer theory of change workshop, NRB Steering Committee, workshop presentation.

- National Reading Barometer (2023a). National Reading Barometer 2023 Summary Report. Nal’ibali Trust.Publications | National Reading Barometer South Africa (readingbarometersa.org).

- National Reading Barometer (2023b). National Reading Barometer 2023 Technical Measures Report. Nal’ibali Trust.Publications | National Reading Barometer South Africa (readingbarometersa.org).

- Polzer Ngwato, T., Shilakoe, L., Morse, K., Huston, K. (2023). National Reading Survey 2023 Findings Report. Nal’ibali Trust.

- Polzer Ngwato, T. (2023b). Special Issue Brief Libraries. Nal’ibali Trust. Publications | National Reading Barometer South Africa (readingbarometersa.org).

- Sullivan, A., Brown, M. (2013) Social inequalities in cognitive scores at age 16: The role of reading. (CLS Working Papers 2013/10). Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University College London: London, UK.

- Zhou, T. & Shilakoe, L. (2022) National Reading Barometer Theory of Change Steering Committee Workshop Presentation.

- UNESCO. (2023). Global education monitoring report 2023: Technology in education—A tool on whose terms? UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/.

- OECD. (2016). Skills matter: Further results from the Survey of Adult Skills. OECD Publishing. (You may substitute later PIAAC thematic reports if preferred; this is the standard anchor citation.). [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2011). Learning for all: Investing in people’s knowledge and skills to promote development—World Bank Group education strategy 2020. World Bank.Optional SABER-specific citation if you want to be explicit:World Bank. (2014). Systems approach for better education results (SABER): What matters most for student learning. World Bank.

- Global Book Alliance. (2020). The book chain: Connecting people to books. Global Book Alliance. https://www.globalbookalliance.org/.

- Indlulamithi Trust. (2017). National social cohesion barometer: South Africa. Indlulamithi Trust. (If you prefer the technical framing:) Indlulamithi Trust. (2019). Indlulamithi social cohesion barometer: Technical report. Indlulamithi Trust.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |