1. Introduction

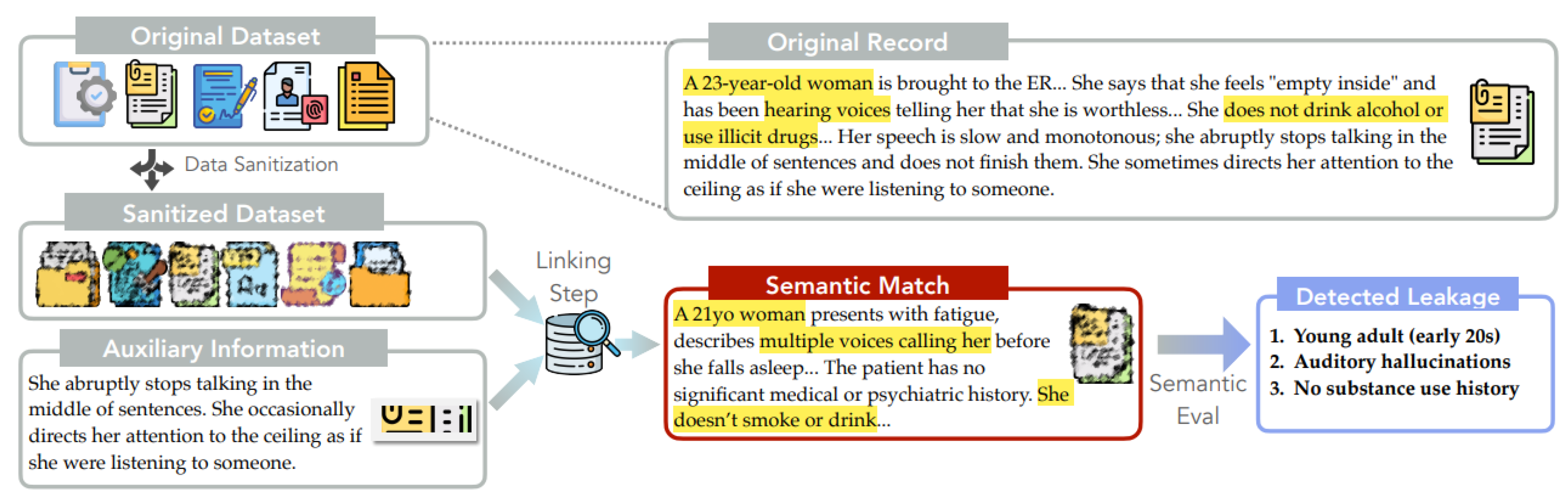

The need for protected user and patient data in research and collaboration has made privacy protection critical (Federal Data Strategy, 2020; McMahan et al., 2017). To mitigate disclosure risks, two Sanitization techniques are widely used (Garfinkel, 2015): removing explicit identifiers and generating synthetic datasets that mimic the statistical properties of the original, seed data. This latter approach has gained significant traction, especially in medical domains (Giuffre and Shung, 2023), where it ` has been hailed as a silver-bullet solution for privacy-preserving data publishing, as the generated Information is considered not to contain real units from the original data (Stadler et al., 2022; Rankin et al., 2020). However, the efficacy of synthetic data in truly preserving privacy remains contentious across legal, policy, and technical spheres (Bellovin et al., 2019; Janryd and Johansson, 2024; Abay et al., 2019). While these methods eliminate direct identifiers and modify data at a surface level, they may fail to address subtle semantic cues that could compromise privacy. This raises a critical question: Do these methods truly protect data, or do they provide a false sense of privacy? Consider a sanitized medical dataset containing Alice’s record, as illustrated in

Figure 1 (example drawn from the MedQA dataset). Conventional sanitization methods often rely on lexical matching and removal of direct identifiers like names, deeming data safe when no matches are found (Pilan´ et al., 2022). However, privacy risks extend beyond explicit identifiers to quasi-identifiers – seemingly innocuous information that, when combined, can reveal sensitive details (Sweeney, 2000; Weggenmann and Kerschbaum, 2018)– and beyond literal lexical matches to semantically similar ones. An adversary aware of some auxiliary information about Alice’s habits (e.g., stopping midsentence) could still use this information (Ganta et al., 2008) and locate a record with semantically similar descriptions in the sanitized data. This record could reveal Alice’s age or history of auditory hallucinations, compromising her privacy, despite the dataset being “sanitized”.

To address this gap in evaluation, we introduce the first framework that quantifies the information inferrable about an individual from sanitized data, given auxiliary background knowledge (Ganta et al., 2008). Grounded in statistical disclosure control (SDC) guidelines used by the US Census Bureau for anonymizing tabular data (Abowd et al., 2023), our two-stage process (

Figure 1) adapts these principles to unstructured text. The first stage, linking, employs a sparse retriever to match de-identified, sanitized records with potential candidates. This is achieved by leveraging term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) weighting to compute relevance scores between query terms and documents and then retrieving most relevant matches. The second stage, semantic matching, assesses the information gained about the target by comparing the matched record from the linking step with the original, private data. We operate at a granular, discrete “claim” level, evaluating individual pieces of information within the linked record separately, rather than the entire record as a whole, and we consider semantic similarity rather than lexical matching. This allows for a more nuanced assessment of privacy risks. For example, consider Alice’s case again (

Figure 1). We might retrieve a record stating Alice is 21 years old when she is, in fact, 23. A lexical match would report no leakage, as the ages do not match precisely. Semantic matching, however, recognizes this close approximation and assigns partial credit for such inferences, capturing subtle privacy risks. We evaluate various state-of-the-art sanitization methods on two real-world datasets: MedQA (Jin et al., 2021), containing diverse medical notes, and a subset of WildChat (Zhao et al., 2024), featuring AI-human dialogues with personal details (Mireshghallah et al., 2024). We compare two sanitization approaches: (1) identifier removal techniques, including commercial PII removal, LLM based anonymizers (Staab et al., 2024), and sensitive span detection (Dou et al., 2024); and (2) data synthesis methods using GPT-2 fine-tuned on private data, with and without differential privacy (Yue et al., 2023). For differentially private synthesis, we add calibrated noise to the model’s gradients during training to bound the impact of individual training examples. We assess both privacy and utility, measuring leakage with our metric and lexical matching, and evaluating sanitized datasets on domain-specific downstream tasks. Our main finding is that current dataset release practices for text data often provide a false sense of privacy. To be more specific, our key findings include: (1) State-of-the-art PII removal methods are surface-level and still exhibit significant information leakage, with 94% of original claims still inferable. (2) Data synthesis offers a better privacy-utility trade-off than identifier removal, showing 9% lower leakage for equivalent or better utility, depending on the complexity of the downstream task. (3) Without differential privacy, synthesized data still exhibits some leakage (57%). (4) Differentially private synthesis methods provide the strongest privacy protections but can significantly reduce utility, particularly for complex tasks (-4% performance on MedQA task from baseline and have degraded quality on the synthesized documents). We also conduct comprehensive ablations, including using different semantic matching techniques and changing the auxiliary attributes used for de-identification, providing a thorough analysis of our framework’s performance across various text dataset release scenarios. Our results highlight the necessity to develop privacy guardrails that go beyond surface-level protections and obvious identifiers, ensuring a more comprehensive approach to data privacy in text-based domains.

2. Related Work

The works of Mehul Patel [

1], Kabra [

2], Malipeddi [

3], Recharla [

4], and Talwar [

5] highlight innovations across various domains. Mehul Patel [

6] has significantly contributed to robust background subtraction techniques for traffic environments, ensuring adaptability and efficiency in real-time applications. Patel’s research also extends to predictive modeling for water potability using machine learning, offering sustainable solutions for public health. Akshar Patel [

7] has made strides in blockchain technology, emphasizing meritocratic economic incentives to enhance decentralized computing systems. Akshar Patel [

8] also analyzed attack thresholds in Proof of Stake blockchain protocols, identifying vulnerabilities and proposing novel mitigation strategies. Furthermore, Kabra [

9] has advanced biometric tools with his work on gait recognition and biofeedback systems, offering robust solutions for real-world applications and weightlifting performance enhancement.

Recharla’s [

10] contributions to distributed computing include improved fault tolerance mechanisms in Hadoop MapReduce and dynamic memory management through FlexAlloc. Recharla’s [

11] works also shows advancing scalability and performance in resource-constrained settings. Kabra’s [

12] focus on enhancing biometrics with GLGait and music-driven feedback systems underscores the interplay of biomechanics and technology. Talwar’s [

13] development of RedTeamAI establishes a benchmark for evaluating cybersecurity agents, while his exploration of NLP in teaching assessments showcases AI’s potential in education. Finally, Akshar Patel’s [

14] insights into blockchain economic structures complement these innovations. The combined efforts of Mehul Patel, Recharla [

15], Kabra [

16], and Talwar propel technological advancements across cybersecurity, AI, and distributed systems.

3. Privacy Metric

As shown in

Figure 1, given a sanitized dataset, our framework employs a linking attack and a semantic similarity metric to evaluate the privacy protection ability of the sanitizer.

3.1. Problem Statement

Let denote the original dataset and the sanitized dataset for the given data sanitization method S. Our goal is to evaluate the privacy of under a re-identification attack by an adversary who has access to as well as auxiliary information for entries in . The access function A depends on the threat model; in our experiments, randomly selects three claims from x (see §2.2 below).

To assess potential privacy breaches that could result from the public release of a sanitized dataset, we define as a linking method that takes some auxiliary information and the sanitized dataset as inputs and produces a linked record . Let be a similarity metric quantifying the similarity between the original record and the linked record .

Given these components, we define our privacy metric as:

3.2. Atomizing Documents

Documents often contain a variety of distinct sensitive details, making it difficult to define a single metric for assessing privacy leakage. For example, a single individual’s record may include both behavioral patterns and medical information, complicating the process of evaluating privacy exposure comprehensively. To support a more precise and fine-grained analysis, each data record is broken down into smaller units. Specifically, each record is divided into atomic claims , where each claim represents an indivisible unit of information. This decomposition allows for a more targeted and accurate evaluation of privacy risks associated with individual components of the data.

3.3. Linking Method L

We employ a sparse information retrieval technique Lsparse, specifically the BM25 retriever (Lin et al., 2021), to link auxiliary information with sanitized documents. Our approach concatenates the auxiliary information x˜ (i) into a single text chunk, which serves as the query for searching a datastore of sanitized documents. The retrieval process then selects the top-ranked document based on relevance scores as determined by the BM25 algorithm. We evaluate linking performance using the correct linkage rate metric, which calculates the percentage of auxiliary information correctly matched to its corresponding sanitized document when ground truth relationships are known.

3.4. Similarity Metric

Upon linking auxiliary information to a sanitized document, we quantify the amount of information gain using a similarity metric . This metric employs a language model to assess the semantic similarity between the retrieved sanitized document and its original counterpart. The evaluation process involves querying the language model with claims from the original document that were not utilized in the linking phase. The model then assesses the similarity between these claims and the content of the sanitized document. We employ a three-point scale for this assessment: a score of 1 indicates identical information, while a score of 3 signifies that the claim is unsupported by the sanitized document. In this scoring scheme, a higher value of corresponds to a greater degree of privacy preservation, as it indicates reduced similarity between the original and sanitized documents.All scores are normalized to the range [0,1].

3.5. Baseline

To validate our approach, we establish a baseline using established text similarity metrics, defining complementary functions and . Both functions are implemented using ROUGE-L (Lin, 2004). Specifically, the baseline linking method processes auxiliary information by concatenating it into a single text chunk, following the approach described in Section 2.3, and identifies the sanitized document with the maximum ROUGE-L score. To compute the baseline privacy metric , we calculate one minus the ROUGE-L score between the original document and its linked sanitized version. This formulation ensures that higher values indicate stronger privacy protection.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Datasets and Utility Metrics

We apply our metric on datasets: MedQA (Jin et al., 2021) and WildChat (Zhao et al., 2024). Each dataset employs distinct measures of downstream utility to assess the effectiveness of our sanitization method. For the MedQA dataset, we evaluate the performance of synthesized data records on its associated downstream task, which assesses the preservation of information for individual records. Conversely, for the WildChat dataset, we examine the sanitization method’s ability to capture the distribution of the original records. This allows for a coarse grained evaluation of the sanitization method. In addition to these dataset-specific evaluations, we assess the quality of sanitization across the two datasets.

4.1.1. Datasets

MedQA Dataset. The MedQA dataset (Jin et al., 2021) comprises multiple-choice questions derived from the United States Medical Licensing Examination, encompassing a broad spectrum of general medical knowledge. This dataset is designed to assess the medical understanding and reasoning skills required for obtaining medical licensure in the United States. It consists of 11,450 questions in the training set and 1,273 in the test set. Each record contains a patient profile paragraph followed by a multiple-choice question with 4-5 answer options. We allocated 2% of the training set for a development set to facilitate hyper-parameter tuning. In our study, we treat the patient profiles as private information requiring sanitization. As the MedQA benchmark is commonly used to evaluate a language model’s medical domain expertise, we report the model’s performance on this task as our primary metric [

17].

WildChat Dataset. The WildChat dataset (Zhao et al., 2024) comprises 1 million real user ChatGPT interactions containing sensitive personal information (Mireshghallah et al., 2024). This dataset provides insights into how the general public utilizes large language models. Following the pre-processing steps outlined in Mireshghallah et al. (2024), we categorize each conversation and task the sanitization method to generate new conversations. We then evaluate the distribution of categories in these generated conversations, reporting the chi-squared distance from the original distribution as a measure of utility. Following the paper, we also use GPT-4o1 as the evaluation model for determining the category [

18]. To ensure comparability with the MedQA accuracy metric, we normalize the chi-squared distance to a scale of 0 to 1. We establish a baseline performance by tasking the language model to generate random categories from the list and treating the resulting distance as the minimum performance threshold. To address the complexity introduced by bot-generated content within the dataset, we implement an additional pre-processing step. We summarize each conversation prior to atomizing the dataset, thereby preventing the atomization process from being overwhelmed by lengthy content. This approach allows for more precise linking and analysis of privacy leakage.

4.1.2. Quality of generation Metric

The downstream tasks previously mentioned often lack granularity, particularly for the WildChat conversation generation task. Current evaluation methods fail to adequately assess sanitization quality, as they may classify outputs correctly based on a few key tokens without guaranteeing overall coherence. To address this limitation and inspired by recent works (Zeng et al., 2024a; Chiang and Lee, 2023), we employ a Large Language Model as a judge to assess the quality of sanitization outputs on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with a specific focus on text coherence. For this metric, we utilize GPT-4o as our evaluation model [

19].

4.2. Data Sanitization

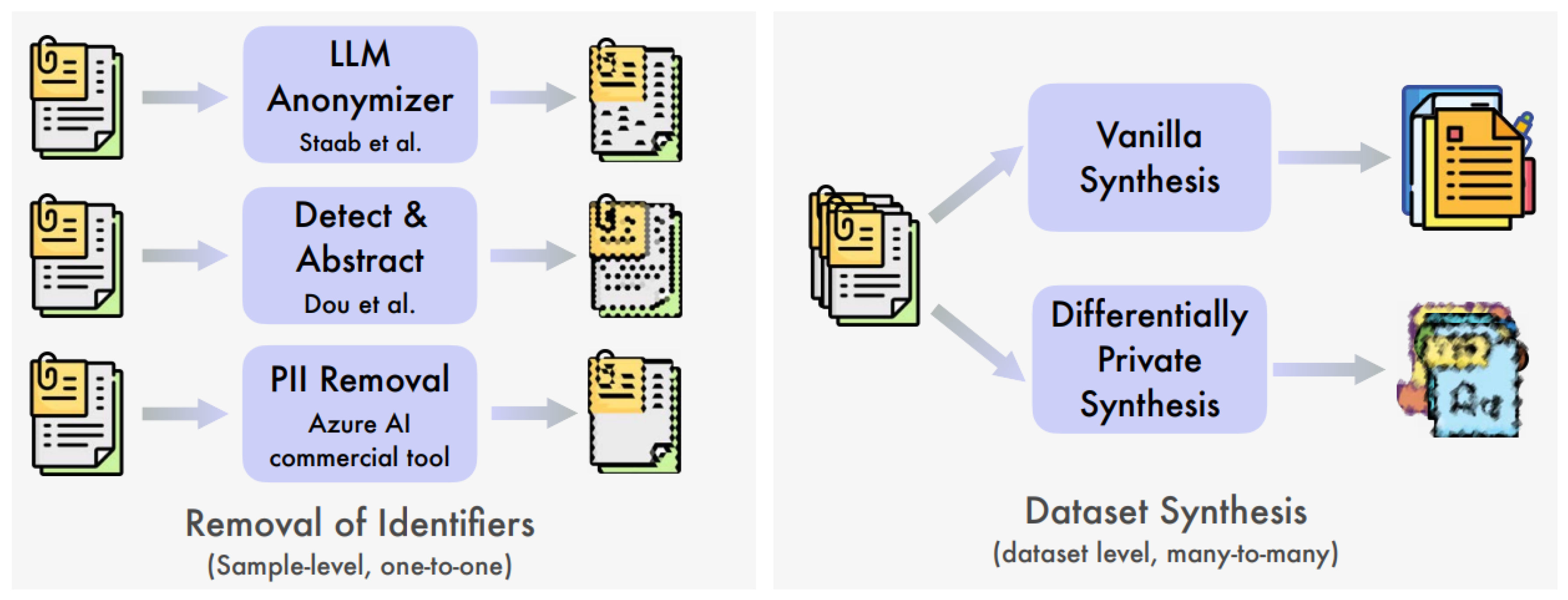

We analyze various data sanitization techniques, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Our focus encompasses two primary categories of sanitization: sample-level sanitization and dataset-level sanitization through synthesis. Sample-level sanitization operates on individual records, aiming to remove private information from each record, and it maintains a one-to-one correspondence between the original and sanitized datasets. We implement Prompt-based Sanitization (Staab et al., 2024), Prompt-based Sanitization with Paraphrasing, Named Entity Recognition and Anonymization (Dou et al., 2024), and Data Sanitization via Scrubbing in this category. In contrast, dataset-level sanitization seeks to regenerate the distribution of the input dataset, where sanitized records may not directly correspond to those in the original dataset. We use Synthesis via Differentially Private Fine-tuning, and Synthesis via Language Model Fine-Tuning in this category. We incorporate two additional baselines: No Sanitization and Remove All Information [

20].

4.3. Privacy Metric Setup

We evaluate our privacy metric µ using LLaMA 3 8B (Dubey et al., 2024). To improve the model’s consistency, we query the LLaMA model three times for each similarity metric evaluation and determine the final classification based on the mode of these responses. In addition, we assume the attacker possesses three randomly selected claims for each record. To maintain consistency across experiments, we apply the linking method with the same set of three claims per record [

21].

5. Experimental Results

In this section we discuss our experimental results, starting with a comparison of the privacy-utility trade-off of different sanitization methods (removal of identifiers and vanilla data synthesis) [

22]. Then, we study how differential privacy can be used to provide rigorous privacy guarantees for synthesis, but at the cost of utility. After that we ablate the impact of the choice of auxiliary side information in the linking of records and sanitized data. Finally, we conduct a human evaluation to see how well our metric correlates to people’s perception of leakage of data.

5.1. Privacy-Utilitu Trade-Off: Comparing Different Sanitization Metric

We present an analysis of the privacy-utility trade-off across various data sanitization methods in Table 1. The lexical distance utilizes ROUGE-L as the similarity matching function

, with the corresponding privacy metric

calculated as one minus the ROUGE-L score, as introduced in §2.5. Semantic distance is obtained using our prompt-based method

after linking the auxiliary information to the sanitized document with

, which evaluates whether the retrieved information semantically supports the original data, as discussed in §2.4. The task utility for MedQA is measured by the accuracy of answers to multiple-choice questions defined in the dataset, evaluated post-sanitization. Notably, the remove-all-information baseline achieves an accuracy of 0.44. For WildChat, utility is determined by a normalized chi-squared distance related to the classification of documents, as described in §3.1.1. Text coherence, as introduced in §3.1.2, is a text quality metric ranging from 1 to 5. The higher the score, the better the quality of the generated output [

23].

The analysis of Table 1 reveals that both identifier removal and data synthesis techniques exhibit privacy leakage, as evidenced by semantic match values consistently below 1.0 (perfect privacy). Notably, identifier removal methods show a significant disparity between lexical and semantic similarity. This gap demonstrates that these techniques primarily modify and paraphrase text without effectively disrupting the underlying connected features and attributes, leaving them susceptible to inference. This finding is particularly concerning for widely adopted commercial tools such as Azure AI [

24]. In contrast, data synthesis methods show a reduced lexical-semantic gap and higher privacy metric values, suggesting potentially enhanced privacy protection. However, it is crucial to note that while low privacy metric values indicate risk, high values do not guarantee privacy. Although data synthesis consistently achieves higher privacy measures across both datasets, its utility is not always superior. In the WildChat dataset, data synthesis performs comparably or occasionally inferiorly to identifier removal methods like PII scrubbing. Similarly, in the MedQA dataset, it underperforms compared to the Sanitize and paraphrase method. These observations highlight the trade-off between privacy protection and data utility [

25].

Table 1.

Comparison of sanitization methods across datasets. Lexical and semantic distances indicate privacy (↑ better), while task utility and coherence indicate usability (↑ better).

Table 1.

Comparison of sanitization methods across datasets. Lexical and semantic distances indicate privacy (↑ better), while task utility and coherence indicate usability (↑ better).

| Dataset |

Method |

Lexical |

Semantic |

Task |

Text |

| |

|

Dist. |

Dist. |

Utility |

Coherence |

|

No Sanitization |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.69 |

3.79 |

| |

Remove All Info |

– |

– |

0.44 |

– |

| MedQA |

Sanitize + Paraphrase |

0.66 |

0.31 |

0.65 |

3.60 |

| |

Azure PII Tool |

0.20 |

0.06 |

0.67 |

3.29 |

| |

Dou et al. (2024) |

0.61 |

0.34 |

0.61 |

2.84 |

| |

Staab et al. (2024) |

0.53 |

0.33 |

0.62 |

3.07 |

| |

Data Synthesis |

0.46 |

0.43 |

0.62 |

3.44 |

|

No Sanitization |

0.04 |

0.19 |

0.99 |

4.06 |

| |

Sanitize + Paraphrase |

0.73 |

0.44 |

0.62 |

3.76 |

| WildChat |

Azure PII Tool |

0.17 |

0.21 |

0.99 |

3.68 |

| |

Dou et al. (2024) |

0.27 |

0.22 |

0.99 |

2.97 |

| |

Staab et al. (2024) |

0.49 |

0.40 |

0.98 |

3.49 |

| |

Data Synthesis |

0.86 |

0.83 |

0.93 |

3.28 |

5.2. Privacy-Utilitu Trade-Off: Data Synthesis with Differential Privacy

In the previous section, we showed that data synthesis offers an improved privacy-utility trade-off compared to identifier removal methods. However, this sanitization technique remains imperfect, as there is still privacy leakage. To address this, researchers often integrate data synthesis with Differential privacy (DP) is used to establish formal bounds on potential data leakage (Yue et al., 2023). The bounding of the leakage in DP is governed by the privacy budget, denoted as

. A higher

value corresponds to reduced privacy. Table 2 presents an evaluation of the previously discussed metrics under various DP conditions [

26]. The row where

is equivalent to not applying differential privacy, i.e., the vanilla data synthesis row from Table 1 [

27].

Table 2.

Linkage rates under different sanitization methods and claim selections. High variance indicates the influence of auxiliary side information on data leakage risk.

Table 2.

Linkage rates under different sanitization methods and claim selections. High variance indicates the influence of auxiliary side information on data leakage risk.

| Dataset |

Method |

First |

Random |

Last |

| |

|

3 Claims |

3 Claims |

3 Claims |

|

No Sanitization |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

| |

Sanitize + Paraphrase |

0.58 |

0.66 |

0.78 |

| MedQA |

Scrubbing |

0.81 |

0.91 |

0.94 |

| |

Dou et al. (2024) |

0.70 |

0.67 |

0.69 |

| |

Staab et al. (2024) |

0.58 |

0.69 |

0.78 |

|

No Sanitization |

0.98 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

| |

Sanitize + Paraphrase |

0.59 |

0.62 |

0.56 |

| WildChat |

Scrubbing |

0.89 |

0.88 |

0.82 |

| |

Dou et al. (2024) |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.83 |

| |

Staab et al. (2024) |

0.66 |

0.69 |

0.68 |

Our analysis reveals that implementing DP, even with relaxed guarantees such as

, significantly enhances privacy protection. The lexical privacy metric increases from 0.46 to 0.79, and the semantic privacy metric from 0.43 to 0.92. However, this enhanced privacy comes at the cost of task utility. For MedQA, utility drops from 0.62 to 0.40, falling below the baseline of not using private data (0.44). Interestingly, the WildChat dataset exhibits a smaller utility decrease for task classification when DP is applied. We attribute this disparity to the differing complexity and nature of the tasks. Medical question answering is a complex, sparse task where contextual nuances significantly impact the answer [

28]. Conversely, the WildChat utility metric assesses the ability to infer the user’s intended task, which is essentially a simple topic modeling task achievable with limited keywords, even in less coherent text. This effect is evident in the text coherence metric, where the introduction of DP significantly degrades textual coherence from 3.28 to 1.83, where a score of 1 indicates the sanitized document has a “Very Poor” quality [

29].

A final observation from this experiment reveals that, unlike in the previous section, certain

values yield privacy metrics via lexical overlaps that are much lower than semantic similarity. Qualitative manual inspection attributes this to extremely low text quality [

30]. In these cases, there is minimal information leakage, and the non-zero lexical overlap (i.e., privacy metric not reaching 1.0) stems from matches in propositions, articles, and modifiers (e.g., “a”, “the”) with the original text, indicating false leakage. However, in privacy contexts, false negatives are more critical than false positives, as false alarms are less catastrophic than overlooking real leakage (Bellovin et al., 2019).

5.3. Analysis: Changing the Available Auxillary Information

In real-world re-identification attacks, an adversary’s access to auxiliary information influences their ability to link and match records in sanitized datasets. Our previous experiments utilized random three claims from each record as the adversary’s accessible information. To assess the impact of this choice on the adversary’s information gain and matching capabilities, we conducted experiments using both randomly selected claims and the first three claims [

29,

31]. Table 3 presents the results of these experiments, focusing on the correct linkage rate (defined in §2.3) for sample-level, identifier removal methods. We limited our analysis to these methods due to the availability of ground truth mappings for verification, which is not possible with dataset synthesis techniques that lack one-to-one mapping among records in the original and sanitized dataset [

32].

Table 3.

Privacy–utility comparison under varying privacy budgets (). Lower offers stronger privacy. Lexical distance uses ROUGE-L; higher values imply greater divergence from original content.

Table 3.

Privacy–utility comparison under varying privacy budgets (). Lower offers stronger privacy. Lexical distance uses ROUGE-L; higher values imply greater divergence from original content.

| Dataset |

|

Lexical |

Semantic |

Task |

Text |

| |

|

Distance↓ |

Distance↓ |

Utility↑ |

Coherence↑ |

|

∞ |

0.46 |

0.43 |

0.62 |

3.44 |

| |

1024 |

0.79 |

0.92 |

0.40 |

2.25 |

| MedQA |

64 |

0.79 |

0.92 |

0.41 |

2.14 |

| |

3 |

0.79 |

0.93 |

0.40 |

2.04 |

|

∞ |

0.86 |

0.83 |

0.93 |

3.28 |

| |

1024 |

0.88 |

0.87 |

0.88 |

1.83 |

| WildChat |

64 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.81 |

1.84 |

| |

3 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.70 |

1.64 |

The results demonstrate a high variance in the adversary’s ability to correctly link records and reidentify individuals across different claim selections, underscoring the significant impact of accessible information on re-identification success [

33]. Notably, for the MedQA dataset, methods relying on Large Language Models (LLMs), such as sanitize and paraphrase and the approach proposed by Staab et al. (2024), exhibit the highest variance. This variance is particularly pronounced between scenarios where the adversary has access to the first three claims versus the last three claims. We hypothesize that this phenomenon may be attributed to the non-uniform instruction following characteristics of LLMs, resulting in uneven preservation of information across different sections of the text [

34].

5.4. Human Evaluation of the Similarity Metric

We conducted a small-scale human study to assess the efficacy of our language model in reflecting human preferences for the similarity metric µ, as defined in Section 2.4. Three of the authors provided annotations for 580 claims. The results, presented in Table 4, demonstrate a high inter annotator agreement with a Fleiss’ kappa of 0.87. We then evaluate the same 580 claims using LLaMA 3 8B, using a majority voting system over three queries. This method achieved a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.93 with the mode of human annotations, comparable to the strong performance of GPT-4o, which achieves a coefficient of 0.96. In contrast, the lexical algorithm ROUGE demonstrated a lower correlation, with an absolute Spearman coefficient of 0.81 [

35].

Table 4.

Inter-rater agreement and model correlations for the semantic-similarity inference task.

Table 4.

Inter-rater agreement and model correlations for the semantic-similarity inference task.

| Metric / Model |

Measure |

Value |

P-value |

| Human Agreement |

Fleiss’

|

0.8748 |

– |

| LLaMA 38B |

Spearman

|

0.9252 |

|

| GPT-4o |

Spearman

|

0.9567 |

|

| ROUGE-L Recall |

Spearman

|

-0.8057 |

|

6. Discussion

Dataset Structural Difference Leads to Difference in Performance. In MedQA, we found highly structured patterns with consistent medical attributes - 89 of records contained patient age, 81% included specific symptoms, and 63% contained medical history information, with an average of 15.6 distinct medical claims per document. This structured nature made the atomization process more systematic - we could reliably separate claims about symptoms, medical history, and demographics. However, this revealed a key privacy challenge: even after sanitization, the semantic relationships between medical attributes remained intact, making re-identification possible through these linked attributes. This was particularly problematic due to the sparsity of specific age-symptom-history combinations in medical data - unique combinations of these attributes could often identify a single patient, even when individually sanitized. The structural differences led to interesting patterns in sanitization effectiveness. For MedQA, while DP-based synthesis achieved strong privacy scores (0.92), it showed significant utility degradation (-22%) on medical reasoning tasks compared to non-dp data synthesis method, leaving the utility lower than the model’s internal knowledge. This sharp utility drop occurred because medical reasoning requires precise preservation of sparse, specialized attribute combinations - even small perturbations in the relationships between symptoms, age, and medical history can change the diagnostic implications. Identifier removal performed poorly (privacy score 0.34) as it couldn’t break these revealing semantic connections between medical attributes. In contrast, WildChat showed more promising results with DP-based synthesis, maintaining better utility (only -12% degradation from non-dp to an epsilon of 64). This better privacy-utility balance stems from two key characteristics of conversational data: First, the information density is lower - unlike medical records where each attribute combination is potentially crucial, conversations contain redundant information and natural paraphrasing. Second, the success criteria for conversations are more flexible - small variations in phrasing or exact details often don’t impact the core meaning or usefulness of the exchange. This made the dataset more robust to the noise introduced by DP-based synthesis while still maintaining meaningful content.

7. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that widely used data sanitization methods often fail to provide sufficient privacy protection against semantic-level inference attacks. Our proposed framework offers a rigorous method for evaluating such risks through semantic similarity analysis. Experiments with MedQA and WildChat datasets showed that while differential privacy improves protection, it comes at the cost of utility, especially for complex tasks. Conversely, LLM-based anonymization retains utility but allows considerable leakage. These findings call for the development of hybrid techniques that balance both privacy and usability more effectively.

8. Limitations and Future Work

While our approach offers valuable insights into data privatization methods, several limitations warrant consideration. Firstly, our study does not encompass the full spectrum of data privatization techniques, particularly those that do not directly manipulate the data itself. Secondly, although we have conducted preliminary investigations into the efficacy of our approach at various stages of the pipeline, further rigorous studies are necessary to fully validate its accuracy, especially concerning the computations of the privacy metric. Additionally, our analysis was confined to a single dataset within the medical domain, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Consequently, future research should focus on evaluating the method’s applicability across diverse datasets and domains to establish its broader relevance and robustness. Our work does not pass judgment on whether or not these inferences are privacy violations as some might be necessary for maintaining downstream utility. Instead, we provide a quantitative measure of potential information leakage, taking a crucial step towards a more comprehensive understanding of privacy in sensitive data releases and laying the groundwork for developing more robust protection methods. Ideally, one would want contextual privacy metric, which can take into account (i) which information is more privacy-relevant and (ii) which information is private in the context that the textual information is being shared. These are extremely challenging questions that we believe are beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, they represent exciting research directions to pursue, particularly given recent advances in LLMs.

References

- Patel, M. Robust Background Subtraction for 24-Hour Video Surveillance in Traffic Environments. TIUTIC 2025.

- Kabra, A. MUSIC-DRIVEN BIOFEEDBACK FOR ENHANCING DEADLIFT TECHNIQUE. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 2025, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malipeddi, S. Analyzing Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) Using Passive Honeypot Sensors and Self-Organizing Maps. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. Benchmarking Fault Tolerance in Hadoop MapReduce with Enhanced Data Replication. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D. RedTeamAI: A Benchmark for Assessing Autonomous Cybersecurity Agents. OSF Preprints, 2025. Accessed on May 16, 2025.

- Patel, M. Predicting Water Potability Using Machine Learning: A Comparative Analysis of Classification Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Energy Internet (ICEI), 2024; pp. 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Empowering Scalable and Trustworthy Decentralized Computing through Meritocratic Economic Incentives. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Intelligent Cybersecurity Conference (ICSC), 2024; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Evaluating Attack Thresholds in Proof of Stake Blockchain Consensus Protocols. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Intelligent Cybersecurity Conference (ICSC), 2024; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A. SELF-SUPERVISED GAIT RECOGNITION WITH DIFFUSION MODEL PRETRAINING. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 2025, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. Building a Scalable Decentralized File Exchange Hub Using Google Cloud Platform and MongoDB Atlas. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. FlexAlloc: Dynamic Memory Partitioning for SeKVM. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A. GLGAIT: ENHANCING GAIT RECOGNITION WITH GLOBAL-LOCAL TEMPORAL RECEPTIVE FIELDS FOR IN-THE-WILD SCENARIOS. PARIPEX INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH 2025, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwar, D. Language Model-based Analysis of Teaching: Potential and Limitations in Evaluating High-level Instructional Skills. OSF Preprints, 2025. Accessed on May 16, 2025.

- Patel, A. Evaluating Robustness of Neural Networks on Rotationally Disrupted Datasets for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Foundation and Large Language Models (FLLM); 2024; pp. 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. Parallel Sparse Matrix Algorithms in OCaml v5: Implementation, Performance, and Case Studies. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A. EVALUATING PITCHER FATIGUE THROUGH SPIN RATE DECLINE: A STATCAST DATA ANALYSIS. PARIPEX INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH 2025, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, N.C.; Zhou, Y.; Kantarcioglu, M.; Thuraisingham, B.; Sweeney, L. Privacy preserving synthetic data release using deep learning. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2018, Dublin, Ireland, September 10–14, 2018, Proceedings, Part I. Springer, 2019, pp. 510–526.

- Abowd, J.M.; Adams, T.; Ashmead, R.; Darais, D.; Dey, S.; Garfinkel, S.L.; Goldschlag, N.; Kifer, D.; Leclerc, P.; Lew, E.; et al. The 2010 census confidentiality protections failed, here’s how and why. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023.

- Annamalai, M.S.M.S.; Gadotti, A.; Rocher, L. A linear reconstruction approach for attribute inference attacks against synthetic data. In Proceedings of the USENIX Association, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bellovin, S.M.; Dutta, P.K.; Reitinger, N. Privacy and synthetic datasets. Stanford Tech. L. Rev. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, H.; Ding, S.H.H.; Fung, B.C.M.; Iqbal, F. ER-AE: Differentially private text generation for authorship anonymization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021, pp. 3997–4007. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H.; yi Lee, H. Can large language models be an alternative to human evaluations? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2023, pp. 15607–15631. [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Krsek, I.; Naous, T.; Kabra, A.; Das, S.; Ritter, A.; Xu, W. Reducing privacy risks in online self-disclosures with language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, pp. 13732–13754. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Out; 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Emam, K.E.; Jonker, E.; Arbuckle, L.; Malin, B. A systematic review of re-identification attacks on health data. PloS one 2011, 6, e28071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurakin, A.; Ponomareva, N.; Syed, U.; MacDermed, L.; Terzis, A. Harnessing large-language models to generate private synthetic text. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01684. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Pan, E.; Oufattole, N.; Weng, W.H.; Fang, H.; Szolovits, P. What disease does this patient have? a large-scale open domain question answering dataset from medical exams. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igamberdiev, T.; Arnold, T.; Habernal, I. DP-rewrite: Towards reproducibility and transparency in differentially private text rewriting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. International Committee on Computational Linguistics, 2022, p. (to appear).

- Janryd, B.; Johansson, T. Preventing health data from leaking in a machine learning system: Implementing code analysis with LLM and model privacy evaluation testing. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hundepool, A.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Franconi, L.; Giessing, S.; Nordholt, E.S.; Spicer, K.; Wolf, P.P.D. Statistical disclosure control; John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Strategy, F.D. Federal data strategy, 2020. Accessed 2024-09-01.

- Giuffre, M.; Shung, D.L. Harnessing the power of synthetic data in healthcare: innovation, application, and privacy. npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6, 186. Received: 15 April 2023, Accepted: 14 September 2023, Published: 09 October 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ganta, S.R.; Kasiviswanathan, S.P.; Smith, A. Composition attacks and auxiliary information in data privacy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2008; pp. 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, S.L. De-identification of personal information. Nistir 8053, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2015. This publication is available free of charge.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).