This analysis is grounded in field-based research findings of six ethnographic studies that involved Native Americans, federal agencies, and the authors of this analysis. Each case illustrates a contemporary toponym dispute regarding names, uses, and management of geological places that involve Native people and Colonial Settlers in North America. The case summaries are organized by Toponym Themes that include (1) Sunset Crater the Space For Multivocality at a national park centered on a Volcanic Geosite, (2) Mateo Tepe Epistemological Divides on the meaning of a geosite, (3) Old Spanish Trail and Lingering Animosity Along a Geotrail between Native and Settler Colonial peoples, (4) Multivocality and Many Place Names on the Bears Ears Mountain, (5) Trust and Name Complexity on an Alaskan Lake, and (6) Layered Surface and Underground Lava Toponymic Landscape in New Mexico. The ethnographic research studies of the authors over the past three decades documents that these are appropriate illustrations of common themes in the USA.

2.1. Case Study Methods

All of the research studies used in this analysis were guided by professionally trained cultural anthropologists and conducted with a trained ethnographic team with the permission of the involved Native people(s). Funding was governed by federal and state regulations designed to protect Human Subjects. All data collection events between tribal representatives and ethnographers were voluntary. Text from the research was reviewed and approved by the involved Native governments before being made public. The research studies were designed to provide publicly available information so that traditional places and resources could be better managed in a culturally appropriate manner. Details of methods are provided in the technical reports for each study.

Native American heritage interpretations form the foundation of this heritage analysis. The authors of this analysis directed these studies. The studies involved ethnographic interviews and ethnohistorical documents, and they acknowledge the value of local histories from an insider perspective; that is, information provided by the people under study. Dozens of additional scholars made significant contributions to the studies and are recognized in the study reports. Ethnographic understandings of geosites, geotrails, and geoscapes further derive from more than a dozen additional ethnographic studies involving these Native cultural groups, conducted by the authors.

Tribes and pueblos were invited to participate in these ethnographic studies, and each appointed representatives to provide cultural interpretations and recommendations to the sponsoring federal agencies. The recommendations were reviewed, edited, and approved by the participating tribes and pueblos. Ethnographic observations and recommendations were intended to be publicly available, thereby producing actionable cultural data for visitor interpretation and culturally appropriate agency management. In depth details about our ethnographic field methods have been described and published elsewhere24,25 (Stoffle 2000, 2007). Together these ethnographic studies involved dozens of ethnographic field collection events which provide both the structure and content the foundation of this analysis.

2.1.1. Geoscape One Sunset Crater (Theme: Space for Multivocality)

Sunset Crater, our first case study, is a volcano in Arizona that illustrates multivocality and epistemological divides that are key in toponymic disputes in this geologically and culturally complex environment. Ethnographic studies identified Native groups who are culturally affiliated with this volcanic landscape that is managed by the National Park Service as Sunset Crater National Monument

26,27. These and subsequent studies inquired into the cultural significance to Native groups and documented Native names for places in the park. These toponyms are now recognized in park trail signs and visitor center displays. Today, authentic traditional toponyms that reflect these ancient Native connections with this volcano occur in park interpretations and brochures (

Figure 2).

Surrounding the monument are volcanic lands that ethnographic studies identified as being culturally connected with the park and its meanings for Native people (

Figure 2). A geosite like Sunset Crater is best understood as situated in its surrounding topography or Geoscape, which is also termed

Geomorphological Landscapes28. A monument trail sign provides a map of eight Native toponyms (

Figure 3). Only one mountain toponym is allocated to each tribe or pueblo, although all peaks have their own Native names and stories. Note that the Native toponyms map is embedded in a larger colonial toponym interpretation, where the peaks are named after one Spanish and three English colonial explorers, and the area is called by the Spanish Colonial name, the

San Francisco Mountains. This example (

Figure 3) illustrates the complexity of modern toponym renaming and the resulting multivocality.

The monument continues to be referred to by its colonial name Sunset Crater, and the surrounding lands are called the Flagstaff Volcanic Landscape. Disputes over the management of the mountains are argued in terms of their traditional names and their role as a center of spiritual power and ceremony. Glowacka, Washburn, and Richland29 have an analysis of this debate entitled Nuvatukya’ovi, San Francisco Peaks, Balancing Western Economies with Native American Spiritualities. In many ways, this detailed analysis of how Native names and stories were used in public and legal debates over the management of a major Native Mountain provides a perfect introduction to this Toponym analysis.

2.1.2. Geoscape Two - Mateo Tepe or Devils Tower, Wyoming (Theme: Epistemological Divide)

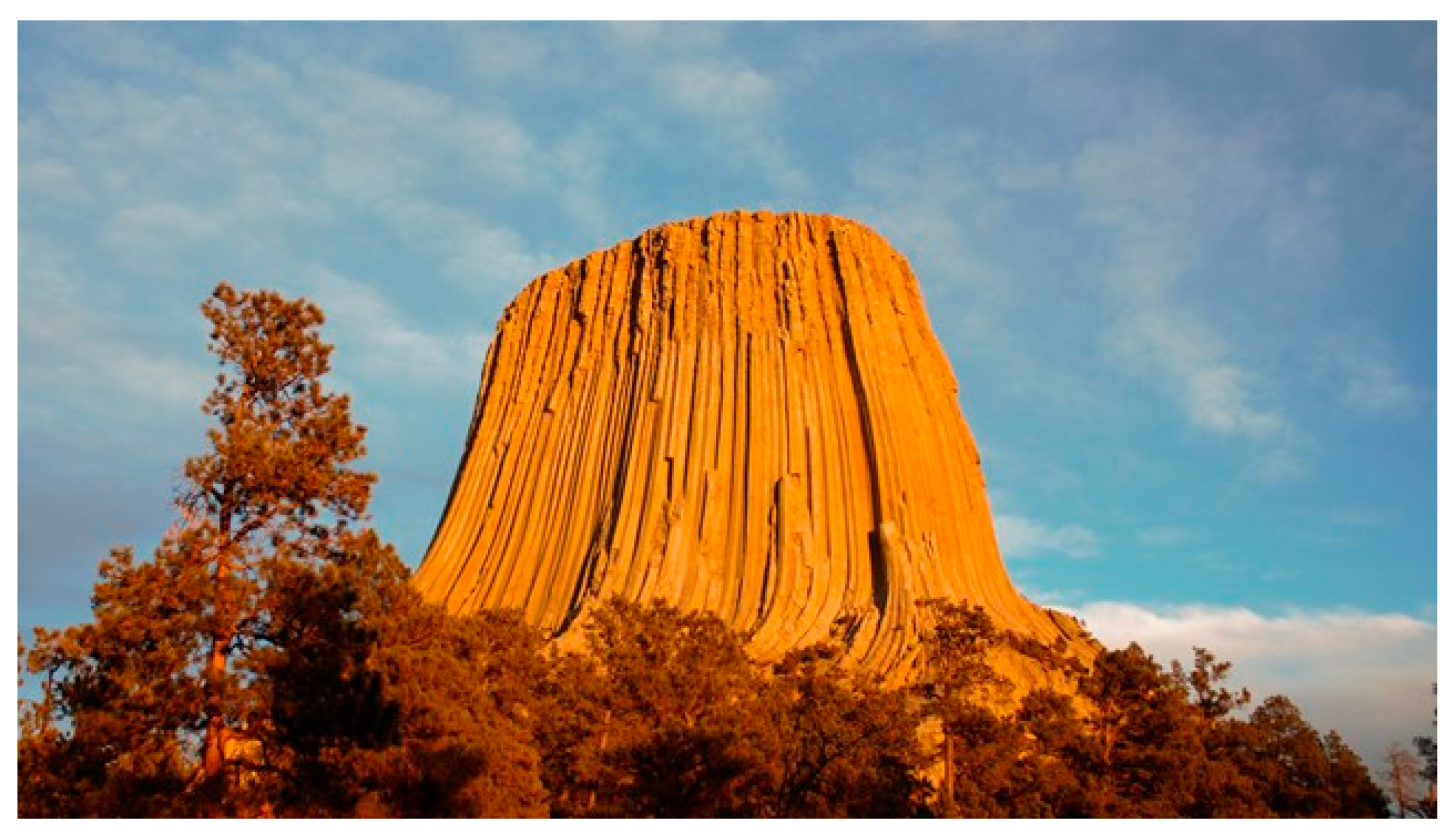

Mateo Tepe (

Figure 4) is a Native American name for a tall and geologically unique geosite. This stone tower rises 1,200 feet above a flat grassland that is bisected by the Belle Furche River. The tower is in an area that has been occupied since time immemorial and has become a sacred site for 23 contemporary Native American tribes. Toponymic debates have occurred since the site was placed on official USA maps regarding whether it should be recognized by a Native name such as Mateo Tepe and which translates into

Stairs to Heaven. Alternatively, Settler Colonial peoples preferred to call it Devils Tower and see it as representing steps into the Earth to Hell itself

30. The struggle over place name began soon after it was mapped in 1875 by a USA military exploring expedition and continues unabated today.

Although the toponymic dispute began in 1875, it has been addressed in various ways by both the public and land managers, including the occasional use of the Native name

Mateo Tepe. This is seen on a tourism postcard printed in 1930 (

Figure 4).

The U. S. Geological Survey party, who made a reconnaissance of the Black Hills in 1875 called attention to the uniqueness of “The Tower.” Col. Richard I. Dodge, commander of the military escort, described it in the following year as “one of the most remarkable peaks in this or any country.” Henry Newt, geological assistant to the expedition, wrote: "The Tower’s remarkable in structure and symmetry, and its prominence makes an unfailing object of wonder. It is a great remarkable obelisk of trachyte, with a columnar structure, giving it a vertically striated appearance, and it rises 625 feed almost perpendicular (sic)”31

Linea Sundstrom wrote an analysis of the multiple dimensions of the Native concept that argues Mateo Tepe (

Figure 5) is a portion of a

Mirror of Heaven reflecting and duplicating the Black Hills -- now South Dakota

32. Sundstrom drew a simple map (

Figure 1.6) to represent the findings of her ethnographically based two-dimensional mirror analysis. Native people stipulate that the heavenly (a Western term) portion of the mirror is exactly like the physical earth toponymic landscape. Spiritual and human activities occur on both dimensions.

One of the many stories about Mateo Tepe’s sacred purpose is when the Spiritual Being known as White Buffalo Calf Woman (Ptecincala Ska Wakan in the Sioux Language) walked down the stairs and then traveled to the pipestone quarries. There, she met with Native spiritual leaders33 and taught them how to properly quarry the red stone and how to make a sacred pipe. From that time on, a pipe made from this red stone was used in ceremonies throughout North America. The smoke from the red pipe rises to heaven and carries prayers to the Creator. After she gave the Sacred Pipe to Native people, White Buffalo Calf Woman returned to the upper dimension and her minor image, the White Buffalo Calf, remained in this dimension. The region surrounding Pipestone has been documented by archaeology as up to 9,000 YBP34. For at least the past 3,000 years, Native people used the Pipestone quarries as a sacred gathering place and the red stone pipes in prayers for the elements of the Earth, including people34. The Pipestone Quarry is currently managed as a National Monument by the USA NPS35.

Figure 6.

Sundstrom’s Map Represents Her Research Findings32.

Figure 6.

Sundstrom’s Map Represents Her Research Findings32.

Devils Tower was declared the first USA National Monument because of its geological value, but it is also now recognized for its Native American value. Mateo Tepe was nominated to and subsequently placed on the Second 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites. International Union of Geological Sciences officially defined it as one of the most important geosites in the World36. Mateo Tepe, aka Devils Tower, was jointly named in the IUGS report (as Heritage Site #148 on page 134) and was nominated as both a geologically significant place and a cultural place of importance to Native American tribes36 (Stoffle et al. 2025). Using both Toponyms, this geosite was almost uniquely awarded a position as Site #444 on the official lists of significant World Sites by the Inte national Commission on Geological Heritage Sites (IUGS 2025).

2.1.3. Geoscape Three - Old Spanish Trail: Theme: Lingering Animosity between Native and Settler Colonial Peoples

The Old Spanish Trail (OST) has been designated as a National Historic Trail by the National Park Service and is managed as such by the National Trails System in Sante Fe, New Mexico. The OST existed as a designated USA historic trail for most of a generation before its inherent toponym controversies threatened its continuation.

The Old Spanish Trail became the fifteenth National Historic Trail after Congress adopted Senate Bill No. 1946 and President George W. Bush signed the legislation in December 2002. The three alternatives of the trail occupy 2,700 miles of traditional Native lands. The Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service administer the trail together to foster trail preservation and public use. These agencies work in close partnership with the Old Spanish Trail Association (Old Spanish Trail Association 2025), American Indian tribes, state, county, and municipal governmental agencies, private landowners, nonprofit heritage conservation groups, and many other organizations.

The Intermountain Regional Office of the National Park Service funded two OST ethnographic studies37,38. The first study involved Native nations that traditionally lived along the trail, and the second involved Hispanic communities that were developed along the trail. Both Native and Hispanic communities were perceived to have been impacted by the caravans of thousands of animals and people who traveled along the OST from New Mexico to California. Once the connection of Native trails was understood after 1849 it became a part of USA national territory, and many kinds of travelers used the trail for various purposes.

Our studies conclude that the U.S.A. National Historic Trail called the Old Spanish Trail (OST) has been incorrectly named and wrongly located by small communities, states, and the U.S. Federal Government. The current toponym OST refers to 3 distinct trails that span about 1,200 miles, involve 40,000 years of use to connect settlements in northern New Mexico and Southern California. Traditional Native trails were used by them to travel for ceremony and resource exchange throughout the southwestern and western North America. Some combination of these traditional foot paths was used since Time Immemorial for both nearby and geographically extensive journeys.

Native people who aboriginally residing in California and New Mexico mutually interacted using geographically diverse and ancient footpaths to share ideas, participate in joint ceremonies, and exchange natural and cultural resources. Some of the foot paths these Native people used are understood as components of the network of trails related to the OST and thus constitute a

heritage geotrail system, which is related to various historic events as well as having ancient Native ties. Hopi, Paiute, and Zuni oral history, officially shared during ethnographic studies describes regular travel from New Mexico and Arizona to California (

Figure 7). One primary destination point for the New Mexico travelers was Chumash aboriginal communities along the coast of the Pacific Ocean. During these visits ceremonies exchanges were made involving red paint and turquoise from the Colorado River and Grand Canyon and special kinds of obsidian from various Great Basin and Colorado Plateau locations. Ceremonies were jointly conducted to share, abalone and other shells. Ocean water was splashed by water, provided by pueblo pilgrims, towards their eastern agricultural communities to cause rain to fall back home, and ocean water was collected in pitch pine covered woven water bottles to be carried home for ceremonies.

Figure 7.

Old Spanish Trail National Historic Trail39.

Figure 7.

Old Spanish Trail National Historic Trail39.

Figure 8.

Shell Artifact Distribution, Major Sites, and Exchange Routes throughout the Great Basin40.

Figure 8.

Shell Artifact Distribution, Major Sites, and Exchange Routes throughout the Great Basin40.

One geosite along these travel areas is called today by a translation of the Native name Ocean Woman who is a Creator Being for Paiutes

41,42. It can be assumed that some of the joint ceremonies focused on her and some of these involved thanks for Creation and hopes for cultural and natural balance

43–46 special cultural connection between Old Woman Mountains (aka

Mamapukaib) (

Figure 9)

This geosite exists as a central cultural feature within the Chemehuevi Paiute geography community47. Ocean Woman the Spiritual Being created Mamapukaib and infused this place with spiritual power during Origin Times42. Many ancient trails to this geosite were used by pilgrims to conduct ceremonies which was a Creation purpose for Mamapukib (Old Woman Mountains) which became a destination for such journeys.

Since about 1680 the Native foot path trail networks that involves the OST has changed in use, location, and condition. It has been influenced by the Native horses especially after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, annual Mexican government sponsored caravans from 1824 to 1848 involving thousands of animals, and hundreds of unregulated wagon trains stimulated by the discovery of gold in the new west coast lands now called California. This analysis is based on more than a hundred OST ethnographic interviews conducted with members of contemporary Native and Hispanic communities located on one or more versions of the evolving trail system.

2.1.4. Cultural Meaning of Native Foot Trails

For more than 40,000 YBP Indigenous people made foot trails that traversed wherever they lived. Their ancestors maintain these trails were designed with a purpose other than simple movement and connected places needing since Creation to be visited and celebrated. Consequently, their ancestors maintain that traditional trails are themselves alive, contain places necessary for ceremony, and remember songs and events that have occurred along their length. Travelers engage the trails, places for ceremony, and each other to create a cultural bond15. The living land can be talked with just as appropriate for interacting with a person48. The land traversed and the trails across it and other dimensions of space and time that are linked to it are sacred living beings9,32,49,50.

Scholars of indigenous trails and the people who made them largely conclude that there is a relationship between journey and identity51. Travelers engage with each other, nature and the supernatural52. Travelers learn landscape knowledge and the inscription of knowledge through symbols and stories14. Behavior and memory contribute to the formation of identities by generating “place-worlds” that people come to identify as their own. Basso11 maintains that place making is a way of constructing the past; that is, the place-worlds we imagine.

Indigenous trails are often for movement from home to spiritual places and people doing this are often called pilgrims53. These link geosites made at Creation to define both the path and the purpose of the journey50. Understanding the relationships between people and their environment is fundamental to understanding the cultural logic involved in ritual performances like pilgrimage30. Turner54 is credited with the concept of communitas, wherein pilgrims during a liminal state bond together with other travelers and with destination places53. Pilgrimages are important to a society’s cultural connections to the local environment, and the incorporation of pilgrimage into ritual sequences affirms the collective valuation of particular places and the social memories inscribed in the landscape55. When pilgrims developed communitas relationships with people and places, both are socially reconceptualized in ways fitting the liminal experience. Simply put, a new social construct will be formed that redefines people and places who have been together in a pilgrimage.

2.1.5. Contemporary Native Trail Networks

Native foot trails today. Some footpaths remain albeit without Native use, cleaning, and prayers such as they received by traditional Native Americans before Euromericans arrived with their animals and new destinations.

Figure 10 is a photo of a traditional foot path today in the Mojave Desert as it was being mapped by two archaeologists.

The archaeology study was focused on possible trails connected with the Salt Song and Bird Song funeral paths. The 1981 photo is towards the east looking at Mopah Spring in the Turtle Mountains where the trail winds down the mountain toward the Colorado River. Native epistemology maintains that this and other ancient foot trails were established by various beings57,58.

2.1.6. Trail Network Over Time Periods

There is no evidence that Spanish settlers in either California or New Mexico regularly traveled or even were aware of these OST trails in the Mojave Desert. The ancient network of trails in the Mojave Desert was generally obliterated by Mexican caravans between 1824 and 1848. After this time the rapid movement of massive wagon-trains of gold seekers called the 49-ers moved from many places in the eastern Unites State to California. Their travel established new trails and further obliterating remnants of both the Native trails and the subsequently establish Mexican caravan trails.

This analysis argues that the Native foot paths or trails used initially by the Spanish to arrive from New Mexico to California were either irreparably demolished by subsequent animal hooves or the route was shifted from its original Native trail footprint to other areas. Displacement through violence and disease of the local Native populations who made and maintained the Native trails for thousands of years precluding their restoring damaged portions of the foot trails which were initially used by the Spanish.

The following are some key times when the Native foot trails were either used, demolished, or no longer a part of Spanish, Mexican or US citizen travels between New Mexico and California. Some Native use of some portions of these foot trails were reestablished when non-Native travelers shifted elsewhere.

Post 40,000 YBP Native Period

Originally for thousands of years an integrated series of foot trails used for ceremony, pilgrimages, and trade by Native peoples. It was maintained as a sacred trail and celebrated as a living spiritual identity.

Post 1600 Spanish Colonial Period

After early AD1600 the trails came under the colonial ownership of Spain. The Native revolt against Spanish settlers in 1680 resulted in most of their domestic animals being released and incorporated into Native communities After this time some Native tribes such as the Utes became predominately horse travelers and traders causing the trails to be widened but they largely remaining in their traditional place.

Post 1780 Depopulation

After diseases reduced the numbers and power of the Ute people largely after 1780 AD others began using the trails. During this period however these were foot and horse trails.

Post 1822 - 1848 Mexican National Period

The Mexican revolution against Spain, from 1811 to 1822 AD, Spanish colonial power ended along with their trail use agreement with Natives. After this time the Mexican government officially permitted national trade to encroach on the trails by massive mule and horse caravans which transported New Mexico woolen goods to California and returned with thousands of mules and horses. Massive damage to the trails traveled occurred, however, many traditional trail segments were no longer used by the fast-moving caravans, so they made their own paths.

Wild horses were observed in large herds near the OST by Fremont in 1844. Such herds could move anywhere but certainly traveled along common paths to and from water and shelter. As foot trail travelers these herds would have damaged the traditional trails.

Post 1849 United States of American Period

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo ended the Mexican - American war and 55% of the Republic of Mexican National territory was ceded to the USA, including the trails. This treaty corresponded with the discovery of gold in newly renamed Mexican State (1824 AD) of Alto California. The massive rush of treasure seekers largely moving where they wished organized into large wagon trains involving hundreds of support animals. Little of the location or structure of the trails survived the movement of thousands of what would be called in American History the Forty-Niners Wagon Trains.

During the NPS funded OST studies all participating tribes and pueblos disputed the USA designated name Old Spanish Trail for a celebrated national trail that they maintained was a series of traditional Native trails that were linked together for Spanish and then Mexican trade caravans. The government of the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico was so incensed by the USA toponym that they refused to participate in the NPS study, even though the activities and events occurring along the OST were key in Taos Pueblo history. They maintained it was always a network of Native trails.

Controversy about the toponym also occurred because the primary use of the OST from New Mexico to California occurred between 1821 and 1849. This was after the Mexican Revolution, which occurred from 1811 to 1821. The OST was not established as a major trade trail during the Mexican National period. After 1849 it became a portion of the USA national territory primarily used for travel by USA colonial settlers seeking gold in California and not Mexican caravans moving woolen products from New Mexico and large mule herds back from California.

Neither the Spanish Colonial government nor the Mexican National government made the OST trail system, which was rapidly modified in size and location after 1849 by the USA gold-seeking settler pack trains and wagons. The toponym OST was simply historically and culturally incorrect. Subsequently, the toponyms for places along the OST were defined in terms of both people and events from these different periods, including Native toponyms.

So even the toponym name Old Spanish Trails carries controversy. As a result, the OST has now been officially surrounded by other larger US National trails which clearly are a part of USA colonial expansion history59. These more recently established national trails diminish both attention to controversy and thus mask OST public debates. The California National Historic Trail is now celebrated as the route of the 1849 gold rush travelers, when in fact initially occurred along or near the OST. So, the history of USA Settler Colonialism has been geographically and temporally shifted.

2.1.7. Geoscape Four: Bears Ears, Utah Theme: Multivocality and Many Place Names

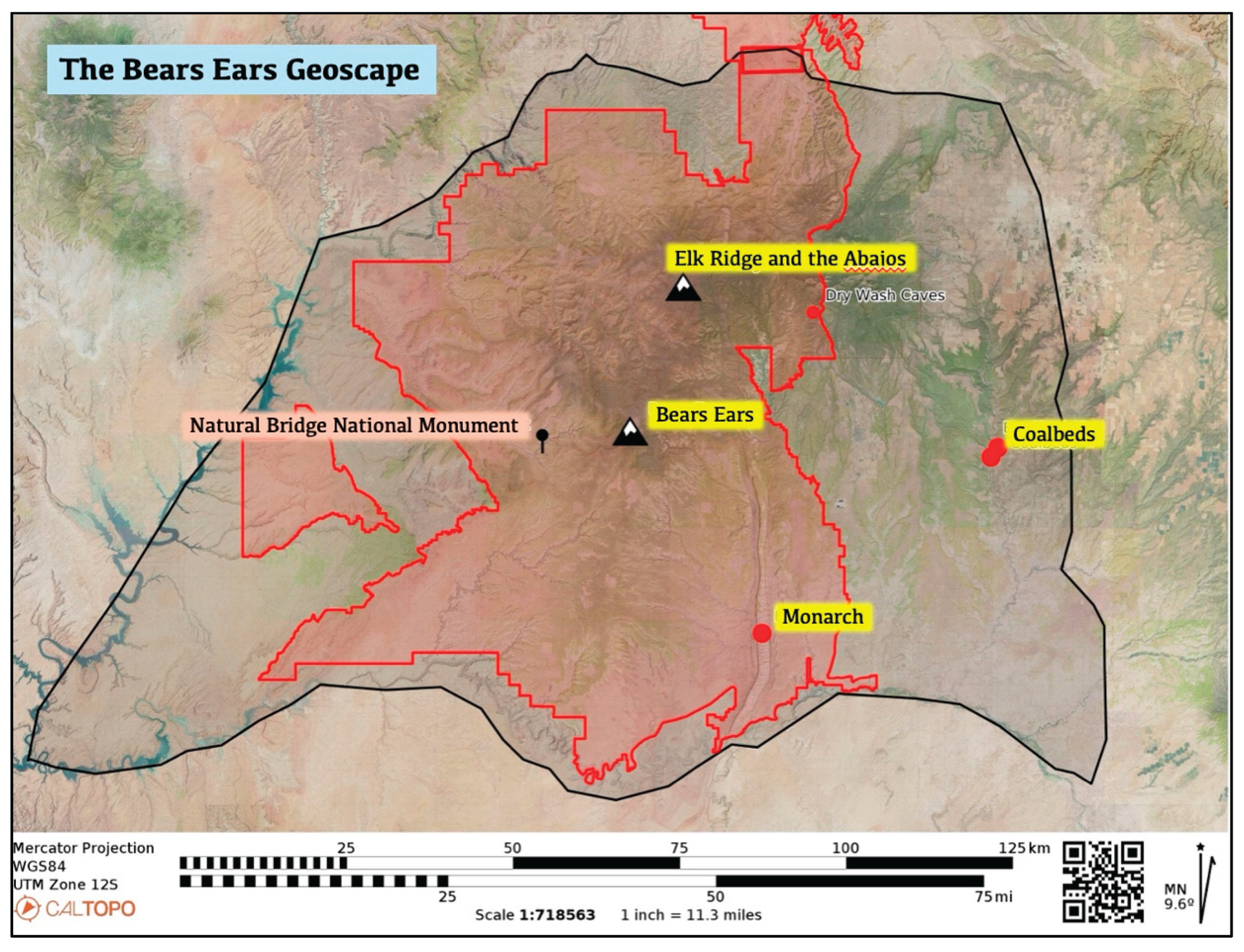

The goal of this case is to document multiple cultural connections to two buttes referred to as Bears Ears (

Figure 7). Bears Ears is two buttes that sit on the northern portion of Cedar Mesa just south of Elk Ridge and to the west of the Abajo Mountains and a southern portion called Cedar Meas. The rain and snow water flow from the buttes into the surrounding Colorado River and the San Juan River.

The Bears Ears Geoscape extends well beyond the boundaries of BLM and USFS jurisdiction. This landscape has physical geological boundaries that correspond with the region’s major hydrological and key geological features. This geoscape is bounded by the Colorado River to the west, the San Juan River in the south, Indian Creek in the north, and Montezuma and Coalbeds Creek in the east60,61. These hydrological systems are fed by water flow from the surrounding sky islands like the Abajo Mountains and Elk Ridge and mesas such as Cedar Mesa. Importantly water flows from the Bears Ears Buttes to feed the streams the flow into the Colorado and San Juan Rivers.

Culturally, the Bears Ears Geoscape is composed of well over 1000 known archaeological sites and it can be argued that it is the western reaches of the Mesa Verde World. This lifeway was developed during in 800-year period (AD 500 to AD 1300) to describe the rise of peak agriculture in what is now the Four-Corners region of the United States. This lifeway was built on a horticultural economy that over time improved dryland and irrigated farming techniques, increased population growth, and evolving social complexity. During this time, there were large ceremonial centers with groups of kivas and community dancing grounds, would be concentrate under the guidance of religious leaders to perform ceremonial activities such as rain making ceremonies. These ceremonial centers include places like Monarch and Coalbeds. Places like Bears Ears and neighboring present day Natural Bridges National Monument have always been places associated with pilgrimage, ceremony, and Creation.

While the 32 contemporary tribes have different and layered connections to this geoscape, they recognize that each tribe has a cultural right to speak on their connections and traditional uses. Aside from the two BLM funded tribal studies, there is the legally mandated Bears Ears Commission which consists of 5 tribes, Hopi, Navajo, the Ute Indian Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and Zuni. This commission was founded when President Obama signed his proclamation on December 26, 2016. According to the proclamation (Obama 2016), “Bears Ears Commission (Commission) is hereby established to provide guidance and recommendations on the development and implementation of management plans and on management of the monument.” Prior to the formation of the Commission, these five tribes formed the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. This group has appointed delegates to represent the tribes’ inherent rights to self-determination, and the coalition works to serve as extensions of each tribe’s sovereign authority as they advocate the protection and preservation of the Bears Ears cultural landscape.

Although a number of colonial toponyms are used today to refer to these three portions of the Bears Ears, from a Native perspective its geology, hydrology, biotic ecosystem, cultural history, and spiritual places are all functionally integrated into an ancient sacred landscape. While this geoscape is known by its colonial name, Bears Ears, the 32 tribes have their own name for this landscape in their own language. For example, the Hopi refer to it as Hoon’Naqvut, the Navajo call it Shash Jaa,’ the Utes named it Kwiyagatu Nukavachi, and for Zuni it is Ansh An Lashokdiwe. Recently, researchers from Northern Arizona University and Heritage Lands Collective conducted an ethnographic study with nine of the culturally affiliated tribes in which tribal representatives shared their deep time attachments to this region.

Native people stipulate that they live in and cultural integrated Bears Ears since Time Immemorial, which archaeologically has been documented to be about 40,000 YBP. Ethnographic studies document how Native groups have utilized the range of natural and ethnographic resources that occur within this complex landscape.

All portions of Bears Ears Geoscape (

Figure 12) contain Native toponyms, however the ones occurring in the southern area have become most famous for their diversity and use. These include the stone bridges in Natural Bridges National Moment and large traditional communities which are characteristic of the Western Mesa Verde World. The following are two examples of the geosites located with the larger Geoscape and that were also visited during the current Native American ethnographic study.

Coalbeds Geosite

The Coal Beds geosite was visited during the ethnographic study due its high density of archaeological resources such as rock peckings and paintings, potsherds, lithics, and evidence of a number of stone structures. Coalbeds is located at the junction of two hydrological systems, Montezuma Creek and Coalbeds Creek. The geosite is largely comprised of two sections. One is a flat area with erected stone pillars and remains of a stone structure. The stone pillars stand in a linear alignment (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) and face an angled structure remains that are on the edge of the elevated area. This alignment was interrupted to be associated with time keeping and ceremony associated with agriculture.

Rock paintings and peckings are found along the wall of the upper portion of the site and a large freestanding rock. The freestanding rock is a striking feature in this study area because of its size and the number of peckings placed on it. This includes linear designs and spirals along with anthropomorphic figures. Near the peckings were pottery pieces including those of black on white pottery and corrugated pottery were found on the southwest side of the hill towards its bottom.

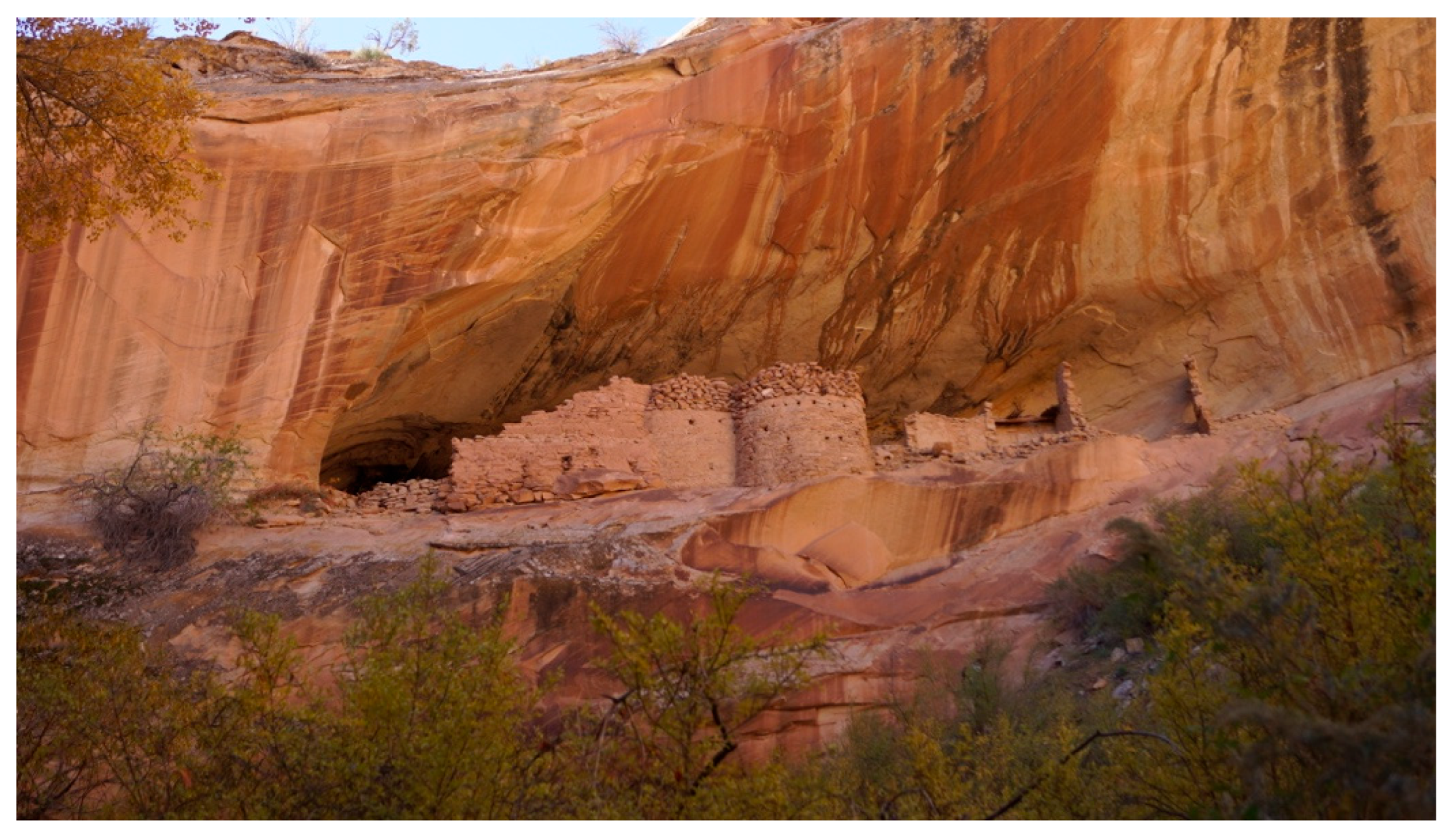

Monarch Geosite

As part of the Butler Wash hydrological system, Monarch feeds into Butler Wash, along with Comb Wash and ultimately into the San Juan River. The Monarch Study Area is not only an important place for archaeological resources, but it is an also an important area for ethnobotanical resources as well such as Four Wing saltbush, shadscale, Indian ricegrass, globemallow, Indian Tea, and snakeweed. During the ethnographic study, tribal representatives saw Monarch as a place of ceremony, medicine, and clan migration.

The Monarch Geosite is centered around a large alcove with a stone structure, a spring, and a wide array of cultural and natural resources such as petroglyphs and grinding area and traditional use plants. The closest archaeological resources visible as one enters the alcove area after climbing the slickrock slope are petroglyphs. On the wall of the alcove are peckings of anthropomorphic figures and geometric lines which includes pecked images of transformed shamans (

Figure 15). These images show how religious specialists have used Monarch as a portal to travel to inversed dimensions of the universe to acquire knowledge, songs, and power (Van Vlack, Arnold, and Bell 2025).

The stone masonry structure remains is one of the most noticeable features available in this geosite and is found in the innermost part of the alcove (

Figure 16). The remains are largely comprised of two units. One unit is a detached, rectangular remain with straight walls. The other surrounds a larger space with straight walls and remains of round towers that have intermittent squared holes on their curved walls.

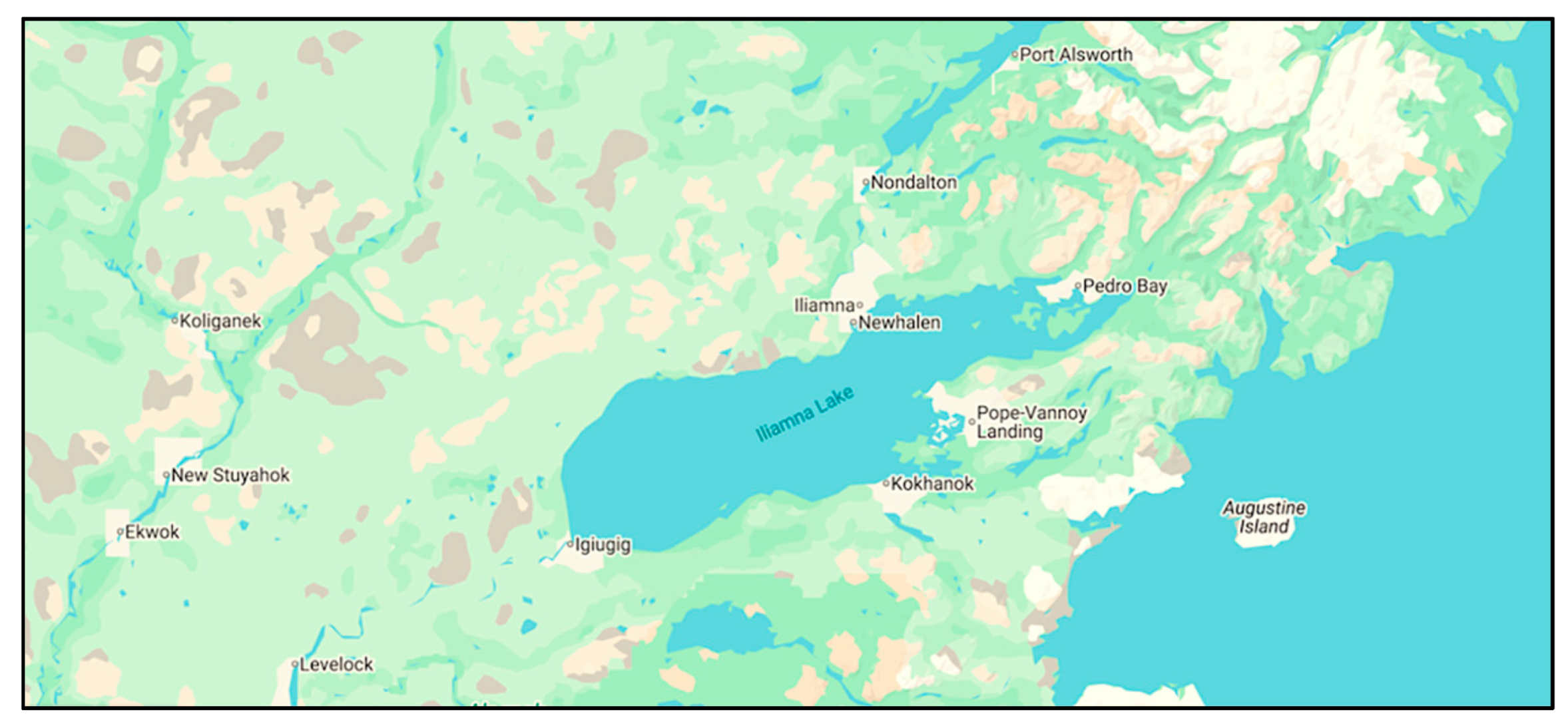

2.1.8. Geoscape Five Iliamna Lake (Nanvarpak, Nila Vena) Native and Local Place Names, Alaska (Theme: Trust and Name Complexity)

This toponym analysis is based on an extended ethnographic and linguistic study by Yoko Kugo, an ethnographer at the University of Alaska. It is focused Native toponyms associated with a very large lake (

Figure 17) (a geosite) and the numerous associated geosites that constitute its massive integrated surrounding geoscape

62–67. Iliamna Lake, which is the largest freshwater lake in Alaska, lies 362 km (225 mi) southwest of Anchorage, in southwest Alaska. Today, five communities lie on the shores of the lake: (1) Pedro Bay, Iliamna, (2) Newhalen, (3) Kokhanok, and (4) Igiugig. The people of Levelock, a community on the Kvichak River, have close ties to the Iliamna Lake communities. Some residents of these communities have moved around seasonally for commercial fishing, hunting, and through marriage. Because of such travel and migration these communities now include descendants of five cultural groups (1) Dena’ina, (2) Central Yupiit, (3) Sugpiaq (Alutiit), (4) Russians, and (5) northern Europeans. The toponyms surrounding the lake reflect these cultural groups but are dominated by the English language settlers who dominate the production and modification of place names.

Two Native names, Nanvarpak (“big lake” in Yup’ik) and Nila Vena (“islands lake” in Dena’ina) refer to the body of water widely known as Iliamna Lake. Locals recalled the present name “Iliamna” Lake having originated from Russians who modified and recorded the Dena’ina name Nila Vena to Ilyamna (as a Russian place name).

According to Kugo63, place names and associated stories about these places illustrate community histories, lifeways, and cultural ethics and practices that are grounded in people’s intimate relationships with their homeland. During her ethnographic research that took place between 2016 and 2019, Dr. Kugo worked with community elders to document traditional place names and stories. This occurred while travelling to these places with community members and participating in harvesting berries and fish. The Elders’ memories about the land and places awaken old connections to the landmarks, streams, lakes, and mountains that have given them life, food, and shelter. Sharing the place names in these stories and injecting their own experiences into the stories expands the narratives, making them more personal and applicable to the Elders’ own contemporary settlements.

Kugo illustrates how difficult it is to both explain the purpose of research conducted by a cultural and social outsider and still meet the culturally appropriate confidential protocols needed for the study to be successful. The researcher, Dr. Kugo, emphasizes that the Iliamna Lake area is unique because (1) it consists of 2+ Native language groups, (2) it previously had a Russian influence, and (3) it is now in USA territory. Place Names will not completely tell the stories and histories of a cultural people, but as ethnographic researchers, we learn by hearing the stories behind the names. Native local people have passed down their histories and experiences through telling stories about places.

Kugo concludes that Indigenous peoples become aware of sense of place in part by passing down place names with the cultural ethics related to these places, and by living according to these ethics. Telling and retelling stories affirms those people’s confidence and competence in their vernacular knowledge, which allows them to thrive on their homeland. Their cultural landscapes exemplify their traditional ways of life, ecology, and culturally based interactions with the land.

Yupiit people maintain reciprocal relationships between humans and animals, as well as between the spiritual and natural worlds. The Yupiit often relate their practices and ways of harvesting plants, fish, and animals at places when talking about their travel routes and landmarks, thereby ensuring that this traditional knowledge spreads. Yupiit people believe that their practices help the spirits return to the living world, so that the people can hunt the animals again in the future. Hunters leave food offerings to show appreciation to the land and animals63, and people discard animal bones in the water after a meal or bury them where people will not step, as a sign of respect.

The joint place name study has documented more than 219 Iliamna Lake Yup’ik place names67. The location of the Yup’ik place name is primarily referenced using English place names on official maps. Yup’ik people wish to have their language place names also on the official maps. The complexity of using Yup’ik place names to indicate geosites derives from how they talk about these places. Often there is no single term of reference but instead the place is known by special events and location relative to other places.

A further place name study (Kuki 2024) extensively involved committees composed of elders whose desire was to expand recorded knowledge of toponyms for future generations. These two yearlong studies resulted in more than 200 places being better recorded and further studied. For each place, elders provided (1) a Yup’ik name, (2) a literal translation, (3) related Yup’ik words that further define the place, (4) location information using other Yup’ik toponyms, (5) an English name, (6) a second Yup’ik name for the area, (7) literal translation of the 2nd name, (8) more Yup’ik words about the place, (9) another Yup’ik name for place, (10) related Yup’ik words about the place, (11) key topographic features of the place, (12) more location information, (13) English name of nearby location and (14) descriptions of toponym from elder oral interviews. The latter often include stories about the place and related locations. In this expanded report of findings, the typical toponym requires two pages of text to be culturally understood. This text constitutes its minimum name in Yup’ik. Thus, the study explains the difficulty of rendering a Yup’ik toponym as a single place name for a flat map. The Yup’ik people and other Native groups are working with ethnographers and cartographers to produce electronic maps that can contain pages of cultural information about hundreds of toponyms. Such living maps are untended to be used in schools and community centers as well as heritage data bases.

2.1.9. Geoscape Six El Malpais National Monument, New Mexico (Theme: Layered Toponymic Landscapes)

El Malpais National Monument (ELMA) is an ancient area consisting of multiple unique geoscapes; that is, lava flows and volcanoes occurring on top of each other forming layers of volcanic fields (

Figure 18 and

Figure 19) and underground lava tubes. Today the lava flows are managed as a USA national monument by the US NPS using the area’s original colonial toponym applied during the Spanish Colonial period and continued during the USA colonial period

68. El Malpais is a Spanish term for a

bad place or bad lands, but the tribes and pueblos who participated in the NPS funded ethnographic study of this lava flow define it using their own linguistic terms and specifying traditional uses of its cultural importance and spiritual places

69. Larsson

69 writes, The name “El Malpais” (“the badlands”) is a colonial one, showing that the Spanish explorers saw these jagged lava fields as cursed and impassable. However, the Pueblo peoples and Navajo saw them as a meaningful part of their homeland.

The five unique lava flows of the park occurred over a period of thousands of years deriving from the foot of a massive sacred mountain, with the colonial name Mount Taylor. This shared sacred massif has dozens of other Native names and has been the subject of extensive Native heritage research70. All the volcanic landforms in the area were not formed because of a single, catastrophic eruption of Mt. Taylor. The current landscape is a product of a succession of volcanic events extending over a long period of time.

The Mt. Taylor massif and its lava fields are active Native ceremonial areas and are generally considered living geological places involved in the rebirth of the Earth. Archaeologists have recorded native people for 40,000 YBP, potentially meaning that native American people have been observing many of the historical volcanic events. Also, these events might have been remembered into the present through oral history. During the Mt. Taylor Traditional Cultural Property (TCP) studies, 16 tribes were consulted. Between October 2007 and February 2008, formal consultation meetings were held with 8 Native governments, including the Pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Zuni, Jemez, Isleta, the Hopi Tribe, the Jicarilla Apache Nation, and the Navajo Nation. These Native tribes and pueblos provided the heritage information needed to nominate most of the Mt. Taylor massif to the National Register of Historic Places.

Mount Taylor and its lava fields are active Native ceremonial areas and are generally considered living geological places involved in the rebirth of the Earth. Archaeologists have recorded native people for 40,000 YBP, potentially meaning that native American people have been observing many of the historical volcanic events. Also, these events might have been remembered into the present through oral history. During the Mount Taylor Traditional Cultural Property (TCP) studies, 16 tribes were consulted. Between October 2007 and February 2008, formal consultation meetings were held with 8 Native governments, including the Pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Zuni, Jemez, Isleta, the Hopi Tribe, the Jicarilla Apache Nation, and the Navajo Nation. These Native tribes and pueblos provided the heritage information needed to nominate most of the Mount Taylor to the National Register of Historic Places.

A shared heritage interpretation is that landscapes are more than the physical environment, or a pictorial representation of natural scenery71–73. In the view of most American Indians, the concept of landscape is not limited to the physical realm of topographic features, stone, trees, and water, but also includes the spiritual world74. Their cultural practices and beliefs reflect a sense of place (emphasis added). Gulliford75 states that “Sacred sites remain integral to tribal histories, religions, and identities” and stresses the importance of “understanding landscapes in the context of traditional Native American religion and the powerful, enduring presence of sacred geography”. Vine Deloria writes that sacred places “are places of overwhelming holiness where the Higher Powers, on their own initiative, have revealed themselves to human beings…This tradition tells us that there are places of unquestionable, inherent sacredness on this earth, sites that are holy in and of themselves.”75

From the surface of the lava flows and emerging volcanos the ELMA lands are sacred and have always been. For example, Kipukas were formed during the flows of lava. During their movement they picked up preexisting earth and carried it along with the flowing lava. When the flowing lava came to a stop islands of preexisting earth now occurred throughout the lava landscape. These dirt islands are now called by the Hawaiian name Kipuka. The islands at ELMA became culturally special and the focus of ceremonial activities. They were connected by laboriously constructed trails from the edges of the lava flow.

Park archaeologists have mapped a system of trails across the most recent of the lava flow and identified that some of these connect the Kipukas with places elsewhere in the lava field and along its edge (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21). In

Figure 21, the trails are marked in yellow and the structures on the Kipukas are indicated by red squares.

Below the surface of the lava flows are tubes (

Figure 22) that define this as a volcanic layered landscape. Lava tube formation and layers: tubes are built up by layers of successive lava flows. There are examples in the monument of stacked lava tubes. A succession of flow events has caused the tubes to be stacked on top of each other. There are several in the Bandera flow and the tube at the base of McCarty’s Crater.

One lava tube, called Sheep Trap, is open at two ends, creating a very short dark zone. One end has a ramp (naturally occurring but humanly enhanced), and the other end is a barricade built by people. Bighorn bones have been found around the barricade76 (Windes 2008). At one end there is a bighorn sheep bone, a wall of breakdown from the tube roof, and tree logs designed to trap the animals.

Many species of invertebrates live in the lava tubes. Moss gardens have the highest diversity. Bats roost and raise young in the tubes during the summer, and several species (perhaps 10 to 12) overwinter in the tubes through hibernation. Other animals enter the lava tubes probably for water in the late spring to early summer, when surface water is lowest and seasonal ice melts. Ringtail cats often frequent lava tubes hunting bats – this is a good reason to roost on the ceiling.

Many species of invertebrates live in the lava tubes. Moss gardens have the highest diversity. Bats roost and raise young in the tubes during the summer, and several species (perhaps 10 to 12) overwinter in the tubes through hibernation. Other animals enter the lava tubes probably for water in the late spring to early summer, when surface water is lowest and seasonal ice melts. Ringtail cats frequently visit the lava tubes to hunt bats, which is a good reason for the bats to roost on the ceiling.

The remains of other animals such as deer, elk, bighorn, bobcat, and wolf have been found in the lava tubes. These remains were likely brought into the lava tubes by people. There are many examples of this kind of activity in several of the lava tubes throughout the monument. Usually, the remains are partial skeletons. There are a few examples of complete skeletons, one example being a bighorn in Braided Cave. Another is an elk and a bobcat in Pantheon Cave (

Figure 23). It is conceivable that the bighorn walked into Braided Cave and died. The remains in Pantheon are harder to explain and are quite old - ca. 2700 BP. They are far at the back of the cave in a dark zone. The only access to the cave is a 40-foot drop at the entry. So far, samples have not identified cut marks or indications of predation on the bone. The presence of faunal remains deep in the caves is a puzzle. A few examples of bone could be explained, but there are many examples- hundreds of bones such that it logically suggests human activity and use.

ELMA offers a telling example of how toponyms can encapsulate competing epistemologies of places. For the Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and Navajo peoples, the volcanic flows, cinder cones, and ice caves that characterize the area are integral components of a sacred geography, animated through origin narratives, ceremonial practices, and kin-based relationships with the land. In these Indigenous epistemologies, El Malpais is not an inert “landform” but a living participant in a network of spiritual, historical, and ecological relations that sustain community identity and cosmological order. The Spanish Colonial name El Malpais—literally “the badlands”—embodies an external, utilitarian gaze that interprets the jagged lava fields as barren, dangerous, and without value for cultivation or settlement. This linguistic imposition not only erases Indigenous place names but also encodes a worldview in which landscapes are assessed in terms of economic productivity rather than spiritual significance. The juxtaposition of these naming systems highlights the role of toponyms as sites of epistemological contestation, where colonial descriptors overwrite Indigenous narratives, yet Indigenous place-based knowledge continues to assert alternative ontologies grounded in long-standing reciprocal relationships with the land.