1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly embedded in educational practice through adaptive learning platforms, intelligent tutoring systems (ITS), learning analytics dashboards, and, more recently, generative large language models (LLMs). Once considered experimental, these technologies are now integrated into classroom instruction, assessment, and planning across educational contexts (Holmes, Bialik, & Fadel, 2019; Zawacki-Richter, Marín, Bond, & Gouverneur, 2019). Proponents argue that AI enhances efficiency, personalization, and scalability, while critics warn of pedagogical deskilling (Hughes, 2021), reduced professional autonomy, and growing ethical risks (Luckin et al., 2016; Selwyn, 2022).

While a growing body of research has examined AI’s impact on student learning outcomes, efficiency gains, and institutional governance, far less attention has been paid to how AI reshapes the cognitive work of teaching itself. Teachers are frequently positioned in the literature as either beneficiaries of automation or passive recipients of algorithmic decision-making, rather than as professionals whose expertise is constituted through complex cognitive judgments enacted in real time. This conceptual gap is especially problematic given that many AI systems now assume responsibilities, such as sequencing content, diagnosing misconceptions, and generating feedback, that were historically central to teacher expertise.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) offers a powerful yet underutilized framework for examining these transformations. CLT posits that learning effectiveness depends on how instructional design manages three types of cognitive load: intrinsic load (task complexity), extraneous load (unnecessary cognitive demands), and germane load (effort devoted to schema construction) (Sweller, 1988; Sweller, Ayres, & Kalyuga, 2011). Traditionally, expert teachers have developed sophisticated pedagogical strategies to balance these loads, drawing on pedagogical content knowledge, contextual awareness, and reflective judgment (Shulman, 1986; Berliner, 2004; Rind, 2022).

The integration of AI fundamentally alters this cognitive ecology of teaching. Adaptive platforms and ITS can dynamically scaffold intrinsic load and reduce extraneous distractions, while generative AI tools can automate feedback, explanation, and text production (VanLehn, 2016; Mollick & Mollick, 2022). However, when these systems operate autonomously or opaquely, they may also displace the very cognitive processes, like diagnosis, interpretation of uncertainty, and reflective decision-making, through which teachers develop and sustain professional expertise. This creates a paradox in which instructional efficiency may increase even as teacher cognition is partially externalized to algorithms.

Recent studies further complicate this picture. While some meta-analyses report performance gains associated with AI-supported instruction (Wang & Fan, 2025), evidence regarding higher-order thinking, transfer, and deep learning remains mixed (Wecks et al., 2024). Moreover, these studies rarely consider how teachers’ cognitive roles are transformed when AI systems manage instructional decisions on their behalf. As a result, debates about AI in education often remain fragmented, separating learning outcomes, ethics, and professional practice, rather than examining their interdependence.

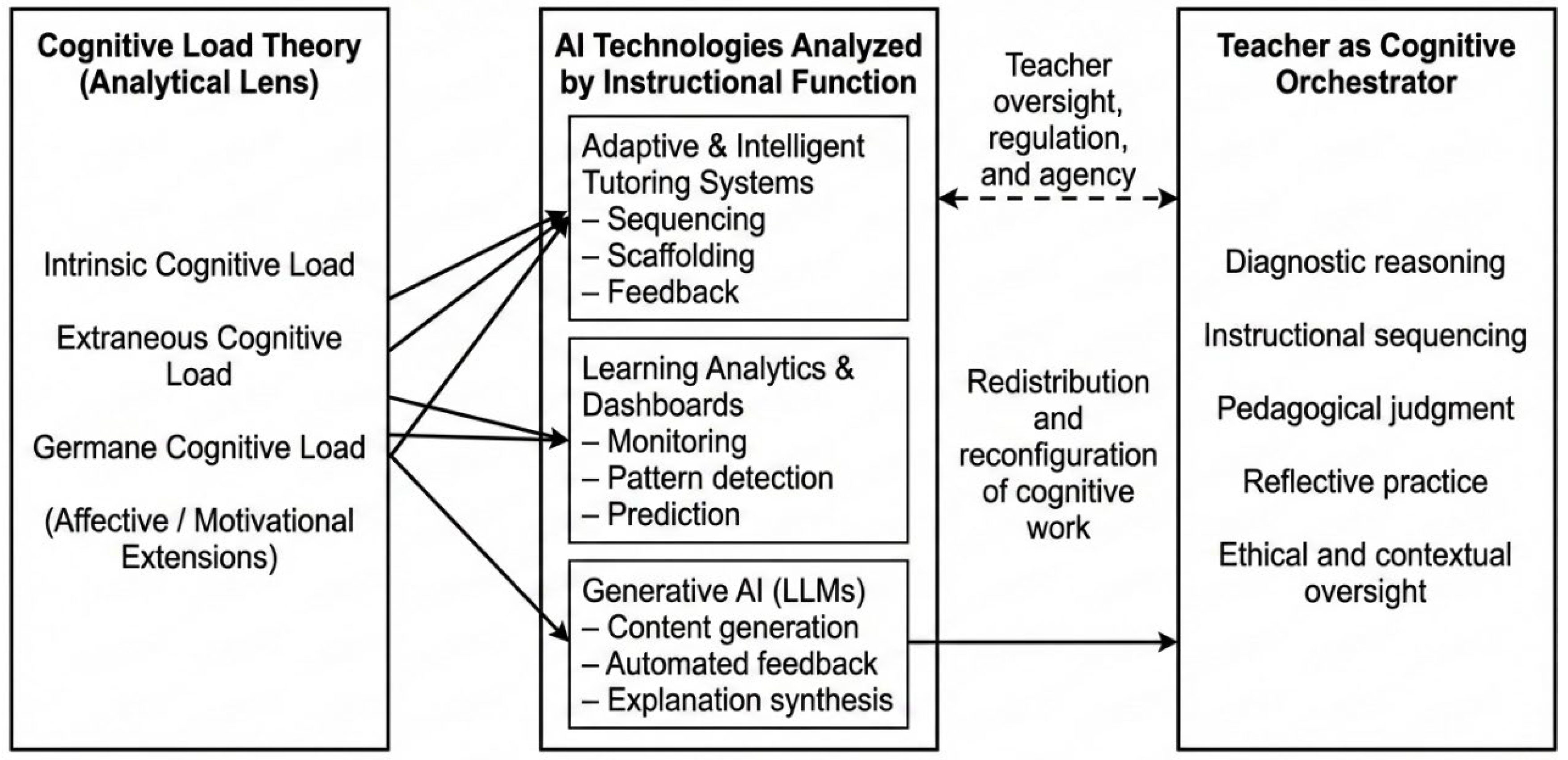

This paper addresses this gap by advancing a conceptual framework that places teacher cognition at the center of AI integration. Drawing on CLT, the paper conceptualizes teachers as “cognitive orchestrators”, professionals who actively diagnose, balance, and regulate cognitive load while mediating between human judgment and algorithmic inputs. Unlike traditional accounts of expert teaching, this orchestration occurs within AI-mediated environments where some cognitive functions are delegated to machines, while others remain irreducibly human. By foregrounding this distinction, the paper moves beyond binary narratives of AI as either augmentation or replacement.

In doing so, the paper makes three interrelated contributions. First, it extends CLT beyond learner-centered analyses by applying it systematically to teacher cognition and professional practice. Second, it introduces the concept of the teacher as a cognitive orchestrator to explain how expertise is reconfigured, not eliminated, under conditions of AI mediation. Third, it integrates ethical and equity concerns into a cognitive framework, showing how opacity, surveillance, and unequal access generate new forms of extraneous and ethical-cognitive burden for teachers and learners alike.

By positioning AI integration as a cognitive, professional, and ethical problem rather than a purely technical one, this paper offers a theoretically grounded lens for evaluating when AI supports deep learning and when it undermines teacher expertise and educational equity.

1.1. Conceptual Positioning and Contribution

A growing body of scholarship has examined the role of AI in education, producing systematic reviews on adoption trends (Garzón, 2025), technological affordances (Matos, 2025), governance implications (Yan et al., 2025), and student learning outcomes (Hon, 2025; Weng, 2024). These reviews have been instrumental in mapping the landscape of AI applications and identifying ethical risks such as bias, surveillance, and datafication. However, they predominantly conceptualize AI as an instructional or institutional tool, rather than as a force that reshapes the cognitive architecture of teaching itself.

Existing reviews tend to focus on what AI does, like automating assessment, personalizing content, or predicting performance, rather than on how these functions redistribute cognitive responsibilities between teachers and algorithms. As a result, teacher expertise is often treated as a background variable or an assumed constant, rather than as a dynamic form of cognition that may be transformed, displaced, or reconfigured through AI mediation. Even studies that address teacher perspectives primarily emphasize attitudes, workload reduction, or acceptance of AI systems, without theorizing how professional judgment and instructional reasoning are cognitively reorganized (Gallup & Walton Family Foundation, 2025; Kalniņa et al., 2024).

This paper is positioned as a conceptual synthesis that bridges three bodies of literature that are rarely integrated in a systematic manner: (1) CLT, (2) research on AI-enabled instructional systems, and (3) scholarship on teacher expertise and professional judgment. Rather than reviewing AI applications descriptively or evaluating their effectiveness empirically, the paper develops a theoretically grounded framework for analyzing how AI alters the distribution of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads across human and algorithmic actors. In this sense, CLT is used not only as an explanatory framework for learning, but as an analytical lens for understanding professional cognition.

A central contribution of this paper is the introduction of the “teacher as cognitive orchestrator” model. While prior literature recognizes that expert teachers manage cognitive load through scaffolding, pacing, and feedback (Shulman, 1986; Berliner, 2004; Rind, 2022), this paper argues that AI fundamentally changes the conditions under which such expertise is exercised. In AI-mediated environments, some cognitive functions, such as sequencing tasks or generating immediate feedback, are increasingly delegated to algorithms, while others, such as diagnosing uncertainty, interpreting emotional cues, and making ethical judgments, remain irreducibly human. The concept of cognitive orchestration captures this new division of cognitive labor and foregrounds the teacher’s role in mediating, overriding, and contextualizing algorithmic outputs.

Importantly, this framework moves beyond binary narratives that frame AI as either augmenting or replacing teachers. Instead, it conceptualizes AI integration as a redistribution of cognitive load that can either support or undermine professional expertise, depending on how instructional decisions are structured and governed. This perspective allows for a more comprehensive analysis of pedagogical deskilling, not as a total loss of expertise, but as a gradual erosion of specific cognitive practices when teachers are removed from diagnostic and reflective decision-making loops.

The paper further advances the literature by integrating ethical and equity considerations directly into the cognitive analysis, rather than treating them as external policy concerns. Opacity, algorithmic bias, surveillance, and unequal access are conceptualized as sources of additional extraneous and ethical cognitive load that teachers must manage when working with AI systems. By linking ethics to cognitive load management, the framework highlights how moral and professional responsibility competes with, and can detract from, teachers’ capacity to foster germane learning.

Taken together, the contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it extends CLT to teacher cognition in AI-mediated instructional contexts. Second, it introduces the teacher as a cognitive orchestrator as a theoretically grounded model of professional expertise under conditions of automation. Third, it embeds ethical and equity concerns within a cognitive framework, demonstrating that responsible AI integration is inseparable from the preservation of teacher agency and deep learning. These contributions position the paper as a conceptual advance rather than a descriptive review, offering a foundation for future empirical research on AI, teacher cognition, and instructional design.

1.2. Conceptual Approach and Methodological Positioning

This study adopts a conceptual and theory-building approach rather than an empirical or systematic review methodology. The purpose is not to aggregate findings or evaluate effect sizes, but to develop an integrative conceptual framework that explains how AI reshapes teacher cognition and professional expertise through the lens of CLT. Conceptual analysis is particularly appropriate where existing empirical research is fragmented, theoretically underdeveloped, or focused on outcomes without sufficiently theorizing underlying mechanisms (Jaakkola, 2020).

The conceptual development proceeded through three iterative stages. First, foundational literature on CLT was examined, with particular attention to classical formulations of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load (Sweller, 1988; Sweller et al., 2011), as well as later extensions addressing affective and motivational dimensions (Plass & Kalyuga, 2019; Moreno & Mayer, 2019). This stage established CLT as the analytical scaffold for examining instructional cognition beyond student learning alone.

Second, research on AI in education was purposively selected to represent distinct classes of AI technologies, including adaptive learning platforms and intelligent tutoring systems (e.g., Aleven et al., 2016; VanLehn, 2016), learning analytics and dashboard systems (Perrotta & Selwyn, 2020), and generative AI tools such as LLMs (Mollick & Mollick, 2022). Rather than treating AI as a monolithic category, these technologies were analyzed in terms of the instructional functions they perform, such as sequencing, scaffolding, feedback generation, and diagnostic inference. This functional focus allowed for systematic mapping of AI capabilities onto different components of cognitive load.

Third, scholarship on teacher expertise, pedagogical content knowledge, and reflective practice (Shulman, 1986; Berliner, 2004; Schön, 1983) was synthesized to identify the cognitive practices through which teachers traditionally manage instructional complexity. The intersection of these three literatures, including CLT, AI-enabled instruction, and teacher cognition, served as the basis for constructing the “teacher as cognitive orchestrator” model. This model was refined through analytical comparison between pre-AI instructional practices and AI-mediated teaching environments, highlighting points of continuity, displacement, and reconfiguration.

The scope of the analysis is intentionally delimited. The paper focuses on formal educational settings at the secondary and higher education levels, where AI systems are increasingly embedded in instructional design and assessment. The analysis emphasizes teacher cognition rather than institutional governance or purely technical system design. While student learning is addressed, it is considered primarily in relation to how teacher expertise shapes, mediates, or is reshaped by AI-driven instructional decisions (see

Figure 1).

This conceptual framework is intended to be generative rather than definitive. It does not claim empirical validation but instead offers analytically grounded propositions that can inform future research. For example, the framework suggests that when AI systems assume responsibility for instructional sequencing or real-time feedback, teachers’ opportunities to engage in diagnostic reasoning and reflective judgment may diminish, with implications for professional expertise. Such propositions are deliberately framed to be empirically testable through qualitative studies, design-based research, or experimental comparisons of AI-mediated and teacher-led instructional environments.

By making its conceptual approach explicit, this paper positions itself as a theory-building contribution that clarifies mechanisms, sharpens constructs, and lays the groundwork for future empirical investigation into AI, cognitive load, and teacher expertise.

2. Cognitive Load Theory as Theoretical Framework

CLT provides a robust theoretical foundation for analyzing how instructional processes shape learning and professional practice. Originally developed by Sweller (1988), CLT is grounded in the assumption that human working memory is limited in capacity and duration, and that effective instruction depends on how cognitive resources are allocated during learning. The theory distinguishes among three types of cognitive load: intrinsic load, which reflects the inherent complexity of learning tasks; extraneous load, which arises from suboptimal instructional design; and germane load, which refers to the mental effort invested in schema construction and automation (Sweller, Ayres, & Kalyuga, 2011).

Traditionally, CLT has been applied primarily to student learning, with a focus on instructional design principles that reduce unnecessary cognitive demands and promote meaningful learning (Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, 2006). However, teachers play a central role in enacting these principles in practice. Through pedagogical content knowledge and professional judgment, expert teachers dynamically regulate task complexity, sequence learning activities, and interpret learner responses in order to balance cognitive load in context (Shulman, 1986; Berliner, 2004). In this sense, teaching itself can be understood as a cognitively demanding practice of continuous load management.

2.1. Contested Nature of Germane Load

While intrinsic and extraneous load are widely accepted constructs within CLT, the concept of germane load has been subject to sustained theoretical debate. Some scholars argue that germane load is not a distinct category but rather reflects productive engagement with intrinsic load under well-designed instructional conditions (Sweller, 2010). Others contend that maintaining germane load as a separate construct is analytically useful for capturing learners’ deliberate investment in schema construction, reflection, and transfer (Paas & Sweller, 2014).

This paper adopts a pragmatic and theoretically explicit position within this debate. Germane load is treated not as an independently measurable quantity, but as a conceptual marker of instructional conditions that promote deep, effortful, and reflective learning. In the context of teaching, germane load is associated with practices that encourage inquiry, metacognition, productive struggle, and adaptive explanation. Importantly, this paper does not claim to resolve debates about the measurement of germane load; rather, it uses the construct analytically to examine how AI systems may support or undermine the conditions under which such cognitive engagement occurs. This positioning aligns with recent conceptual uses of germane load as a heuristic for instructional quality rather than a strictly separable cognitive resource.

2.2. Emotional and Psychological Dimensions of Cognitive Load

More recent extensions of CLT emphasize that cognitive processing does not occur in isolation from affective and motivational factors. Plass and Kalyuga (2019) argue that emotions such as anxiety, frustration, or confidence directly influence how learners allocate cognitive resources, while Moreno and Mayer (2019) highlight the role of motivation in sustaining engagement with complex tasks. These insights are particularly relevant in AI-mediated learning environments, where automation, surveillance, and algorithmic evaluation may generate new emotional pressures for both students and teachers.

AI systems that monitor performance, predict outcomes, or provide constant feedback can inadvertently increase learners’ anxiety and reduce willingness to engage in productive struggle (Williamson & Eynon, 2020). For teachers, this emotional dimension feeds back into cognitive load management. The need to interpret emotional cues that AI systems fail to recognize, to reassure students, or to mitigate stress induced by automated monitoring introduces additional cognitive demands that are not captured by traditional instructional design models. These demands can be understood as a form of extraneous load imposed on teachers by the affective limitations of AI systems.

2.3. Ethical-Cognitive Burden and AI Opacity

Beyond emotional factors, AI integration introduces ethical and epistemic challenges that have direct cognitive implications. Many AI systems operate as opaque “black boxes,” offering recommendations or predictions without transparent reasoning (OECD, 2024). For teachers, engaging with such systems requires additional mental effort to interpret, justify, or sometimes contest algorithmic outputs. This effort diverts cognitive resources away from core instructional activities and reflective practice.

This paper conceptualizes this phenomenon as an ethical–cognitive burden: the mental effort teachers expend in managing the moral, professional, and accountability-related implications of algorithmic decision-making. This burden is closely aligned with extraneous load, as it represents cognitive effort that does not directly contribute to schema-building or instructional insight but is nevertheless unavoidable in AI-mediated contexts. When teachers must explain or defend algorithmic decisions to students, parents, or administrators, ethical reasoning competes with germane instructional cognition.

2.4. CLT as an Analytical Lens for AI-Mediated Teaching

Adopting CLT as the theoretical framework for this study allows a structured analysis of how AI redistributes cognitive responsibilities in teaching. Rather than asking whether AI improves or harms learning in general, CLT enables a more precise examination of which cognitive functions are automated, which are displaced, and which remain essential to professional expertise. It provides categories, like intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load, through which the cognitive consequences of AI integration can be systematically compared across instructional contexts.

Crucially, CLT also serves a normative function in this analysis. It offers criteria for evaluating whether AI integration supports deep learning and professional judgment or undermines them through over-automation, opacity, or ethical strain. By extending CLT to include emotional and ethical dimensions of cognitive load, this paper positions the theory as a flexible yet rigorous framework for understanding the evolving cognitive ecology of AI-mediated teaching.

Building on the theoretical grounding provided by CLT and its extensions to emotional and ethical dimensions, the remaining sections of this paper apply CLT as an analytical and interpretive lens to theorize how AI-mediated instruction reshapes teacher cognition, professional practice, and educational equity. Rather than advancing empirical hypotheses, the following conceptual questions structure the analytical discussion in

Section 3 to 6, guiding the examination of AI integration as a cognitive and professional transformation of teaching:

How can AI-enabled instructional systems be conceptually understood to reconfigure teachers’ roles in managing intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads compared to pre-AI instructional arrangements?

How does AI integration conceptually reshape teacher expertise, professional autonomy, and reflective instructional practice within AI-mediated teaching environments?

What ethical and equity challenges arise, at a conceptual level, when cognitive responsibilities shift from teachers to algorithmic systems, and how can these challenges be theorized in relation to cognitive load management?

How can CLT be used as a conceptual framework to inform principled strategies for integrating AI in ways that preserve teacher agency and support deep, reflective learning?

Together, these questions frame the paper’s contribution as a theory-building inquiry, offering a structured lens through which AI integration is analyzed as a redistribution of cognitive, ethical, and professional responsibilities rather than as a narrowly technical innovation.

3. Shifts in Teacher Workload and Cognitive Load Management in the AI-Enabled Classroom

This section addresses the first research question: How can AI-enabled instructional systems be conceptually understood to reconfigure teachers’ roles in managing intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads compared to pre-AI instructional arrangements? To avoid treating AI as a monolithic category, the analysis differentiates among adaptive learning platforms and ITS, learning analytics and dashboard systems, and generative AI tools such as LLMs. Each class of AI interacts with cognitive load in distinct ways and reconfigures teacher cognition differently.

3.1. Intrinsic Load: From Teacher-Led Sequencing to Algorithmic Adaptation

Before the integration of AI, teachers primarily managed intrinsic load through pedagogical strategies such as scaffolding, task decomposition, pacing, and formative diagnosis (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). Pre-AI digital tools, such as interactive whiteboards or learning management systems, supported these practices without replacing teachers’ interpretive role (Clark & Mayer, 2016). Teachers remained directly responsible for judging task complexity and students’ readiness to progress.

Adaptive learning platforms and ITS, such as AutoTutor or DreamBox, now automate aspects of this process by dynamically adjusting task difficulty and sequencing content based on learner performance (Aleven et al., 2016; VanLehn, 2016). These systems can effectively scaffold intrinsic load by matching task complexity to learners’ current performance levels, often with greater speed and granularity than is possible through whole-class instruction. From a learner perspective, this can reduce overload and support progression.

However, from the perspective of teacher cognition, this automation alters the locus of diagnostic reasoning. When algorithms determine task sequencing in real time, teachers may become less involved in identifying moments of conceptual difficulty or readiness. Over time, reduced engagement in such diagnostic judgments may limit teachers’ opportunities to refine pedagogical content knowledge related to task complexity and conceptual progression. Thus, while adaptive AI can manage intrinsic load efficiently, it may also displace an important site of professional expertise if teachers are positioned as monitors rather than decision-makers.

3.2. Extraneous Load: Clarity, Automation, and the Problem of Opacity

Teachers have traditionally reduced extraneous load by clarifying instructions, minimizing distractions, and designing coherent learning materials (Paas & Sweller, 2014). In AI-mediated classrooms, different AI systems affect extraneous load in divergent ways. Generative AI tools such as Grammarly or automated feedback systems can reduce extraneous load by improving linguistic clarity, providing immediate corrections, and streamlining routine instructional tasks (Fitria, 2021; Lookadoo et al., 2025). When used selectively and transparently, such tools can free cognitive resources for both teachers and students to focus on higher-order learning.

By contrast, learning analytics dashboards and predictive systems introduce new sources of extraneous load. These systems often present teachers with complex visualizations, performance predictions, or risk indicators without transparent explanations of how outputs are generated (Perrotta & Selwyn, 2020; Gillani et al., 2023). Interpreting, contextualizing, and sometimes contesting these outputs imposes additional cognitive demands on teachers, particularly when algorithmic recommendations conflict with professional judgment. This opacity transforms extraneous load from a design problem into a professional and ethical challenge.

Thus, while some AI tools reduce extraneous load through automation and clarity, others increase it by shifting interpretive and accountability burdens onto teachers. The net effect depends not only on technical design but on how teachers are expected to engage with AI outputs in practice.

3.3. Germane Load: Supporting or Undermining Deep Instructional Engagement

Germane load is associated with instructional practices that promote schema construction, reflection, and higher-order thinking (Kirschner et al., 2006). For teachers, germane load is enacted through activities such as diagnosing misconceptions, designing productive struggle, facilitating dialogue, and reflecting on instructional effectiveness. Generative AI tools, including LLM-based writing assistants and automated explanation systems, present a particularly complex relationship with germane load. On one hand, these tools can support germane engagement by modeling explanations, generating prompts, or offering alternative representations that teachers may adapt for instructional purposes (Chen & Gong, 2025). When used as cognitive supports rather than substitutes, they may enhance teachers’ reflective repertoire.

On the other hand, when generative AI provides ready-made answers, solutions, or feedback without teacher mediation, it risks short-circuiting the cognitive processes through which both teachers and students construct meaning. Teachers may become less involved in analyzing student reasoning or designing follow-up questions, while students may bypass productive struggle (Zhai & Ma, 2022). In such cases, germane load is not eliminated but displaced; it shifted away from reflective instructional cognition toward algorithmic completion.

Overall, AI-enabled systems extend teachers’ capacity to manage cognitive load but simultaneously reconfigure where and how professional judgment is exercised. Adaptive systems primarily affect intrinsic load through automated sequencing; analytics systems reshape extraneous load through interpretive and ethical demands; and generative tools pose the greatest risk to germane load when they replace, rather than support, reflective instructional practices. These differentiated effects underscore the need to evaluate AI integration not in general terms, but in relation to specific cognitive functions and professional roles.

4. AI Integration and Its Impact on Teacher Expertise, Autonomy, and Reflective Practice

This section addresses the second research question: How does AI integration conceptually reshape teacher expertise, professional autonomy, and reflective instructional practice within AI-mediated teaching environments? Drawing on CLT, the analysis focuses on how AI alters teachers’ engagement with diagnostic reasoning, pedagogical decision-making, and reflective judgment, which are core components of professional expertise.

4.1. Teacher Expertise as Cognitive Practice

Teacher expertise is not reducible to subject knowledge or procedural competence; it is enacted through ongoing cognitive practices such as diagnosing student understanding, calibrating task difficulty, interpreting uncertainty, and responding to emerging misconceptions (Shulman, 1986; Berliner, 2004). Within a CLT framework, these practices are closely associated with teachers’ management of germane cognitive load, as they involve deliberate reflection, schema refinement, and adaptive instructional judgment.

AI-enabled systems increasingly assume responsibility for several of these instructional functions. Adaptive platforms and ITS automate task sequencing and scaffolding, while generative AI tools produce explanations, examples, and feedback instantaneously. Although these systems can improve efficiency and reduce routine workload, they also risk displacing teachers from moments of instructional uncertainty that are central to the development and maintenance of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK).

For example, when an adaptive system dynamically corrects errors or simplifies tasks in real time, teachers may no longer observe moments of what we call “scaffolding collapse”, which refers to the points at which learners struggle productively and reveal underlying misconceptions. These moments traditionally serve as diagnostic cues that enable teachers to refine explanations, adjust representations, and deepen their understanding of how students learn particular concepts. When AI resolves these moments autonomously, teachers lose opportunities to engage in diagnostic reasoning, gradually weakening the cognitive practices through which expertise is sustained.

4.2. Professional Autonomy and Algorithmic Decision-Making

Professional autonomy refers to teachers’ capacity to exercise discretionary judgment over instructional goals, pacing, assessment, and pedagogical responses. In AI-mediated classrooms, this autonomy becomes increasingly conditional rather than absolute. Learning analytics dashboards, predictive systems, and platform-based curricula often nudge teachers toward algorithmically generated recommendations regarding student risk, pacing, or intervention strategies (Perrotta & Selwyn, 2020; Gillani et al., 2023).

From a cognitive load perspective, acting on algorithmic recommendations can reduce short-term extraneous load by simplifying decision-making, but it may also reduce teachers’ engagement in germane cognitive processes associated with reflective planning and professional judgment. When instructional decisions are increasingly pre-structured by platforms, teachers may shift from active designers of learning to reactive implementers of system outputs. This phenomenon aligns with broader critiques of the platformization of education, in which pedagogical authority is subtly transferred from professionals to data-driven systems (Kerssens & van Dijck, 2021; Williamson & Piattoeva, 2019).

Importantly, the erosion of autonomy does not occur uniformly. Teachers with strong professional confidence and AI literacy may critically interrogate, override, or reinterpret algorithmic suggestions, thereby preserving their cognitive authority. Others, particularly in high-accountability or surveillance-oriented environments, may feel compelled to comply with system outputs, even when these conflict with professional judgment. Thus, AI integration produces differentiated patterns of autonomy shaped by institutional context, policy pressures, and teachers’ perceived legitimacy to resist algorithms.

4.3. Reflective Practice in AI-Mediated Instruction

Reflective practice, as articulated by Schön (1983), involves professionals’ capacity to think in and on action, examining the assumptions, uncertainties, and consequences of their decisions. Within CLT, reflective practice is closely tied to germane cognitive load, as it requires sustained mental effort directed toward understanding and improving instructional processes.

AI systems can both support and undermine reflective practice. On one hand, data visualizations, automated summaries, and generative prompts can provide resources that stimulate reflection, particularly when teachers use AI outputs as starting points for inquiry rather than as authoritative answers (Selwyn et al., 2023). On the other hand, when AI systems present recommendations as objective, optimized, or final, they may discourage questioning and reduce teachers’ engagement in reflective judgment.

Repeated reliance on automated solutions risks retraining teachers’ expectations of teaching as a process of optimization rather than interpretation. Over time, this may shift professional norms away from uncertainty, experimentation, and deliberation, key conditions for reflective growth, toward compliance with algorithmic rationality. Such shifts do not eliminate teacher agency outright, but they render it more effortful, contingent, and unevenly distributed.

Taken together, AI integration reshapes teacher expertise not through abrupt replacement, but through gradual displacement of specific cognitive practices. Adaptive systems affect teachers’ engagement with intrinsic load management; analytics systems reshape extraneous load through interpretive and accountability demands; and generative AI tools pose the greatest risk to germane cognitive engagement when they bypass reflective instructional reasoning.

Teacher agency persists under AI mediation, but it becomes conditional, dependent on teachers’ capacity to critically engage with, override, and contextualize algorithmic outputs (Frøsig & Romero, 2024). From a CLT perspective, preserving teacher expertise requires maintaining teachers’ access to germane cognitive work, particularly diagnostic reasoning and reflective judgment. Without deliberate design and policy safeguards, AI integration risks transforming teachers from cognitive orchestrators into operators of instructional systems.

5. Ethical and Equity Implications of Algorithmic Cognitive Load Management in Education

This section addresses the third research question: what ethical and equity challenges arise, at a conceptual level, when cognitive responsibilities shift from teachers to algorithmic systems, and how can these challenges be theorized in relation to cognitive load management? Rather than treating ethics and equity as external policy issues, this analysis positions them as integral to the cognitive ecology of AI-mediated teaching. Ethical risks such as opacity, surveillance, and inequitable access are conceptualized as sources of additional cognitive burden that directly affect teachers’ capacity to engage in germane instructional work.

5.1. Opacity and Ethical-Cognitive Burden

Many commercial AI systems used in education operate as opaque “black boxes,” providing recommendations, predictions, or automated decisions without transparent reasoning (OECD, 2024). For teachers, opacity does not merely raise epistemic concerns; it imposes a distinct form of cognitive demand. Teachers must interpret algorithmic outputs, assess their credibility, and decide whether to accept, adapt, or override them, often without access to the underlying logic of the system.

This paper conceptualizes this demand as an ethical-cognitive burden: the mental effort required to reconcile algorithmic recommendations with professional responsibility, accountability, and moral judgment. Unlike productive germane load, this burden does not directly contribute to instructional insight or schema-building. Instead, it diverts cognitive resources toward justification, risk management, and ethical deliberation, thereby increasing extraneous load at the expense of reflective teaching.

The ethical-cognitive burden is intensified when teachers are required to explain or defend algorithmic decisions to students, parents, or administrators. In such cases, teachers become intermediaries who absorb the ethical costs of algorithmic opacity, even though they do not control the system’s design. This dynamic undermines professional autonomy and repositions teachers as accountable for decisions they did not fully author.

5.2. Surveillance, Anxiety, and Psychological Load

AI-enabled surveillance technologies, such as attention tracking, behavior monitoring, or predictive risk scoring, are often justified as tools for improving efficiency or early intervention. However, these systems introduce psychological pressures that reshape cognitive load for both students and teachers. Studies indicate that constant monitoring can increase anxiety, reduce willingness to engage in productive struggle, and narrow students’ focus to performance compliance rather than deep learning (Williamson & Eynon, 2020).

For teachers, the emotional consequences of surveillance feed back into extraneous cognitive load. Teachers must manage not only instructional content but also students’ stress, resistance, or disengagement induced by automated monitoring. Interpreting emotional cues that AI systems overlook, and mitigating their effects, requires additional cognitive effort that competes with germane instructional reasoning. As a result, surveillance-oriented AI may paradoxically increase overall cognitive load rather than reduce it.

5.3. Equity, Access, and the Digital Matthew Effect

AI technologies do not operate in neutral or evenly distributed contexts. Access to high-quality AI systems, infrastructure, and professional development is uneven across schools and regions. This disparity produces what can be described as a digital Matthew effect: those with greater resources benefit disproportionately from AI integration, while those with fewer resources fall further behind (Azeem & Abbas, 2025).

From a cognitive load perspective, well-resourced contexts are more likely to experience reductions in extraneous load, as AI systems are better designed, more transparent, and supported by training. In contrast, under-resourced contexts often face increased extraneous load due to poorly implemented systems, limited AI literacy, and lack of technical support (Laupichler, et al. 2022). Teachers in these settings must expend cognitive effort simply to make AI function, leaving fewer resources for reflective and adaptive instruction.

Moreover, algorithmic bias can compound inequities. Systems trained on non-representative data may misinterpret or misclassify learners from marginalized backgrounds (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). Such misclassifications not only harm students but also impose additional ethical and cognitive burdens on teachers, who must correct, compensate for, or resist biased outputs. These dynamics undermine germane engagement by eroding trust, fairness, and inclusivity, conditions essential for deep learning.

Taken together, these ethical and equity concerns demonstrate that AI integration reshapes cognitive load not only through instructional design but through moral and social responsibility. Opacity generates ethical–cognitive burden; surveillance increases psychological load; and inequitable access amplifies extraneous demands while constraining germane engagement.

From a CLT-informed perspective, responsible AI integration must therefore be evaluated not only in terms of efficiency or performance gains, but in relation to how it redistributes cognitive and ethical responsibility within teaching. When ethical burdens accumulate unchecked, they crowd out the cognitive space necessary for reflective practice, professional growth, and deep learning. Thus, equity and ethics are not peripheral considerations but central determinants of whether AI supports or undermines the cognitive foundations of teaching.

6. CLT-Informed Strategies for AI Integration that Preserve Teacher Agency and Deep Learning

So how can CLT be used as a conceptual framework to inform principled strategies for integrating AI in ways that preserve teacher agency and support deep, reflective learning? This section revolves around this final question posed in this study. Drawing on the preceding analysis, the recommendations are organized around three interrelated pillars that correspond to the paper’s core conceptual contributions: (1) preserving teachers’ role as cognitive orchestrators, (2) treating cognitive load management as a design problem, and (3) ensuring ethical–pedagogical alignment in AI integration.

6.1. Preserving the Teacher as Cognitive Orchestrator

The central argument of this paper is that teachers’ expertise resides in their capacity to orchestrate cognitive load through diagnosis, interpretation, and reflective judgment. AI systems should therefore be designed and implemented in ways that preserve teachers’ access to germane cognitive work, rather than displacing it. This requires reframing AI as a decision-support system rather than a decision-making authority.

One key recommendation is the institutionalization of “teacher override” mechanisms, whereby teachers are explicitly authorized and encouraged to bypass or modify algorithmic recommendations when professional judgment deems it necessary. Such mechanisms protect teacher autonomy and ensure that reflective practice remains central to instructional decision-making.

Teacher education and professional development programs should explicitly address AI-mediated cognitive load management. Workshops and training modules should focus on helping teachers identify which instructional decisions can be safely delegated to AI and which require human judgment, such as interpreting uncertainty, managing productive struggle, and making ethical decisions in context. Embedding CLT into AI literacy initiatives can equip teachers to critically evaluate AI tools in terms of their impact on intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load.

6.2. Cognitive Load Management as a Design Challenge

The analysis demonstrates that AI integration is not cognitively neutral; its effects depend on design choices that shape how cognitive load is distributed. AI systems should therefore be evaluated not only on efficiency or predictive accuracy, but on how transparently and coherently they support cognitive load management.

Reducing extraneous load requires designing AI systems whose recommendations are interpretable and explainable to teachers. Dashboards, analytics, and adaptive systems should provide clear rationales for outputs, enabling teachers to integrate algorithmic insights into professional reasoning rather than treating them as opaque directives. Co-design approaches, in which teachers collaborate with developers, can help align AI functionalities with pedagogical principles (Holstein et al., 2019).

With respect to intrinsic load, AI should scaffold complexity without oversimplifying content or removing opportunities for productive struggle. Design features that allow teachers to adjust levels of automation, pacing, and feedback can prevent over-reliance on algorithmic sequencing and preserve teachers’ diagnostic engagement. From a CLT perspective, flexibility and transparency are essential to ensuring that AI supports, rather than substitutes for, professional cognition.

6.3. Ethical-Pedagogical Alignment and Equity

Ethical and equity concerns must be treated as central design and policy considerations rather than afterthoughts. As discussed earlier, opacity, surveillance, and biased data systems generate ethical-cognitive burdens that compete with germane instructional work. Responsible AI integration therefore requires alignment between ethical principles and pedagogical goals.

At the institutional level, policies should mandate transparency, fairness, and accountability in educational AI systems, ensuring that teachers are not held responsible for opaque or biased algorithmic decisions. Surveillance-oriented applications should be critically evaluated for their psychological and cognitive consequences, particularly for marginalized learners.

Equity-oriented strategies are also essential. Targeted investment in infrastructure, training, and support is necessary to prevent a digital Matthew effect, in which well-resourced schools benefit from AI while under-resourced contexts face increased extraneous load. From a CLT perspective, equity is not only a moral imperative but a cognitive one: unequal access to high-quality, transparent AI systems directly affects teachers’ capacity to foster deep learning.

7. Conclusion and Implications

This paper advances research on AI in education by repositioning teacher cognition at the center of AI integration debates. While existing scholarship has focused largely on adoption trends, learning outcomes, or ethical risks, this study offers a conceptual framework for understanding how AI reshapes the cognitive architecture of teaching itself. Drawing on CLT, the paper demonstrates that AI integration redistributes, not merely reduces, cognitive responsibilities across human and algorithmic actors.

The first contribution of this paper is the systematic extension of CLT to teacher cognition in AI-mediated instructional contexts. Rather than treating CLT solely as a theory of student learning, the analysis shows how intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads are actively managed by teachers as part of professional practice. By examining how different AI systems scaffold, automate, or displace instructional decisions, the paper provides a cognitively grounded account of how teaching expertise is enacted and potentially transformed under conditions of automation.

The second contribution is the development of the “teacher as cognitive orchestrator” model. This conceptualization reframes teachers not as passive users of AI nor as professionals rendered obsolete by automation, but as agents who mediate between algorithmic efficiency and human judgment. The analysis demonstrates that while AI can assume responsibility for sequencing, feedback, and routine scaffolding, teachers remain indispensable in diagnosing uncertainty, interpreting emotional cues, exercising ethical judgment, and sustaining reflective practice. Importantly, the paper shows that teacher agency persists in AI-mediated environments but becomes conditional and effortful, shaped by institutional expectations, algorithmic opacity, and professional confidence.

The third contribution lies in integrating ethical and equity concerns directly into a cognitive framework. Rather than treating issues such as opacity, surveillance, and unequal access as external policy matters, the paper conceptualizes them as sources of ethical–cognitive burden that compete with germane instructional work. This integration highlights how ethical responsibility, cognitive load, and educational equity are mutually constitutive, and how neglecting one undermines the others. In doing so, the paper provides a novel lens for evaluating AI integration not only in terms of performance gains but in relation to its impact on professional judgment and deep learning.

These contributions have important implications for teacher education, instructional design, and educational policy. Teacher preparation and professional development programs should equip educators with CLT-informed AI literacy, enabling them to critically evaluate when AI supports learning and when it undermines reflective practice. Designers of educational AI systems should prioritize transparency, interpretability, and flexibility, ensuring that teachers retain meaningful control over instructional decisions. At the policy level, ethical safeguards and equity-oriented investments are necessary to prevent AI from amplifying existing disparities or eroding professional autonomy.

This paper does not claim empirical validation of its framework. Instead, it offers a theoretically grounded model intended to generate testable propositions and guide future research. Empirical studies using qualitative, experimental, or design-based approaches can build on this framework to examine how AI-mediated instructional environments shape teacher cognition over time and across contexts.

The challenge facing education is not whether AI will enter classrooms, but how it will be integrated without hollowing out the cognitive and ethical foundations of teaching. By conceptualizing teachers as cognitive orchestrators and positioning CLT as both an analytical and normative guide, this paper contributes a principled framework for navigating this challenge, one that affirms the enduring centrality of human judgment in an increasingly algorithmic educational landscape.