1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have emerged as transformative technologies across diverse applications, from conversational AI assistants to code generation and document analysis [

1]. However, deploying these models in production environments presents substantial infrastructure challenges. A single LLaMA-70B model requires approximately 140GB of GPU memory for half-precision inference, necessitating multiple high-end GPUs and incurring significant costs even during idle periods [

2].

Serverless computing offers an attractive paradigm for LLM deployment, providing automatic scaling and pay-per-use economics that align well with the bursty nature of inference workloads [

3]. Major cloud providers have introduced serverless inference offerings, yet these systems struggle with a fundamental tension: LLMs require substantial warm-up time to load model weights into GPU memory, while serverless architectures assume rapid function instantiation.

The cold start problem in serverless LLM inference is particularly severe. Loading a 7B parameter model from cloud object storage (e.g., Amazon S3) can take 25–30 seconds, while larger models like LLaMA-70B may require several minutes [

4]. This latency is unacceptable for interactive applications where users expect sub-second response times. Furthermore, maintaining warm instances to avoid cold starts negates the cost benefits of serverless computing.

Recent work has made progress on this challenge. ServerlessLLM [

4] introduced multi-tier checkpoint loading that exploits local NVMe storage, achieving 6–8× speedup over remote loading. However, these approaches still incur second-scale latencies that may violate service level agreements (SLAs) for real-time applications.

This paper presents FlashServe, a serverless LLM inference system designed for cost-efficient deployment with reduced cold start overhead. FlashServe makes three key contributions:

First, we design a tiered memory snapshotting architecture that maintains model checkpoints in host DRAM across a cluster of inference servers. By leveraging optimized DMA transfers through PCIe with pinned memory and asynchronous streaming, FlashServe transfers model weights from host memory to GPU HBM at rates approaching 25 GB/s, reducing cold start time from tens of seconds to sub-second levels.

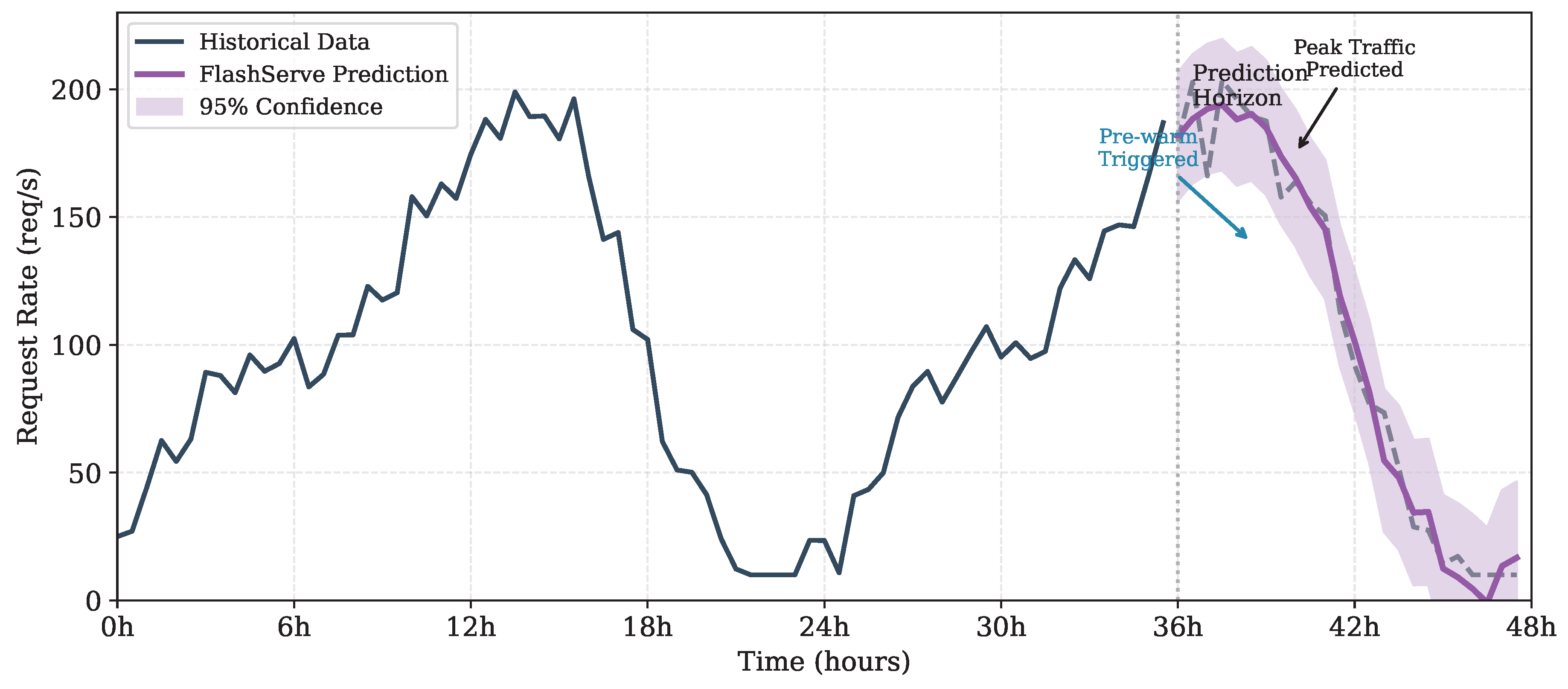

Second, we develop a predictive autoscaling mechanism based on a hybrid Prophet-LSTM model that forecasts request arrival patterns. By pre-warming GPU pods before traffic spikes occur, FlashServe amortizes cold start costs across multiple requests while avoiding unnecessary resource provisioning during low-traffic periods.

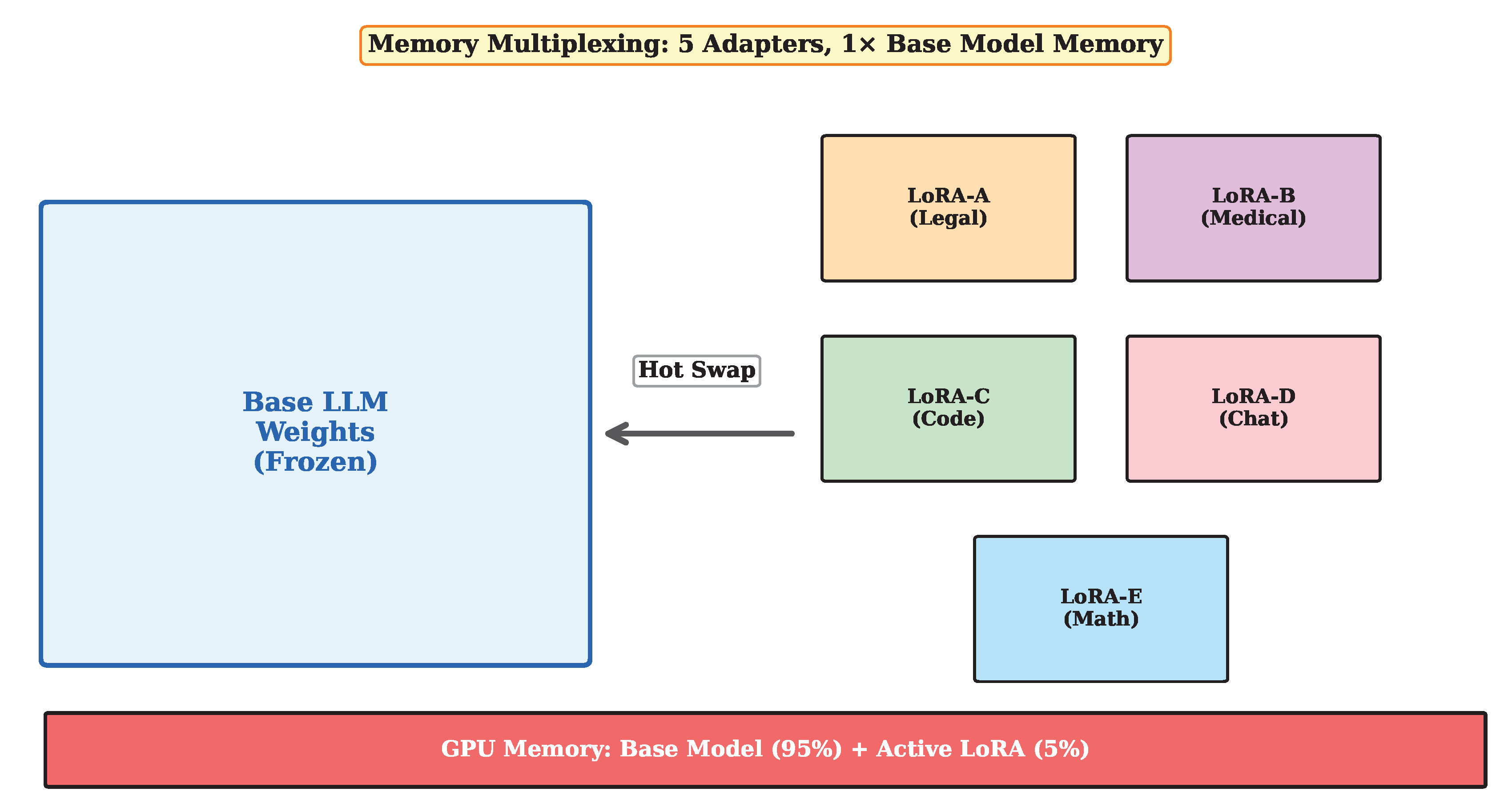

Third, we propose efficient LoRA adapter multiplexing that enables serving multiple fine-tuned model variants on shared GPU infrastructure. This approach significantly improves resource utilization when serving diverse customized models for different use cases.

Experimental evaluation on realistic workload traces demonstrates that FlashServe achieves cold start latencies of 0.58 seconds for a 7B model, representing a 49× improvement over baseline S3 loading and 3.3× improvement over ServerlessLLM. Under bursty workload patterns from the Azure Functions dataset [

3], FlashServe reduces GPU idle costs by 32% while meeting sub-second TTFT requirements for 95% of requests. These results suggest that serverless LLM deployment is becoming increasingly practical.

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Serverless Computing for ML Inference

Serverless computing has gained substantial adoption for general-purpose workloads due to its operational simplicity and cost efficiency [

5]. In the Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) model, developers deploy stateless functions that are automatically scaled based on demand, with billing based on actual execution time rather than provisioned capacity.

Applying serverless principles to ML inference is attractive but challenging. Traditional serverless functions are lightweight (megabytes) and start within milliseconds, while ML models can be gigabytes in size and require specialized GPU hardware. The cold start problem—the latency incurred when initializing a new function instance—becomes particularly severe for LLMs.

Prior work on serverless ML inference has focused on optimizing container startup and model loading. INFless [

6] proposed batching and heterogeneous resource management for ML serving. Tetris [

7] introduced memory-efficient model hosting through intelligent scheduling. However, these systems were designed for smaller models and do not address the unique challenges of multi-billion parameter LLMs.

2.2. LLM Serving Systems

The rapid growth of LLM applications has driven innovation in serving systems. vLLM [

8] introduced PagedAttention for efficient KV cache management, achieving 2–4× throughput improvement through reduced memory fragmentation. Orca [

9] proposed iteration-level scheduling (continuous batching) to improve GPU utilization by dynamically adjusting batch composition during generation.

For distributed serving, DeepSpeed-Inference [

10] provides tensor parallelism and optimized CUDA kernels for multi-GPU deployment. AlpaServe [

11] combines model and data parallelism with statistical multiplexing for efficient multi-model serving.

While these systems excel at serving warm models, they provide limited support for serverless scenarios where models must be rapidly loaded on demand. The fundamental assumption of persistent model residency conflicts with serverless elasticity requirements.

2.3. Cold Start in LLM Serving

The cold start problem for LLMs differs qualitatively from traditional serverless workloads.

Table 1 compares cold start components across different scenarios. For a typical serverless function, container initialization dominates at 100–500 ms. For LLMs, model loading from remote storage can take 10–100× longer than all other initialization steps combined.

ServerlessLLM [

4] addressed this challenge by introducing loading-optimized checkpoint formats and multi-tier storage hierarchies. By caching models on local NVMe SSDs, ServerlessLLM reduces loading time to 1–2 seconds. However, this still exceeds typical SLA requirements for interactive applications, and the approach requires careful placement decisions to ensure models are cached on servers where they will be needed.

2.4. Motivation for FlashServe

Our analysis of production LLM serving traces reveals several insights that motivate FlashServe’s design:

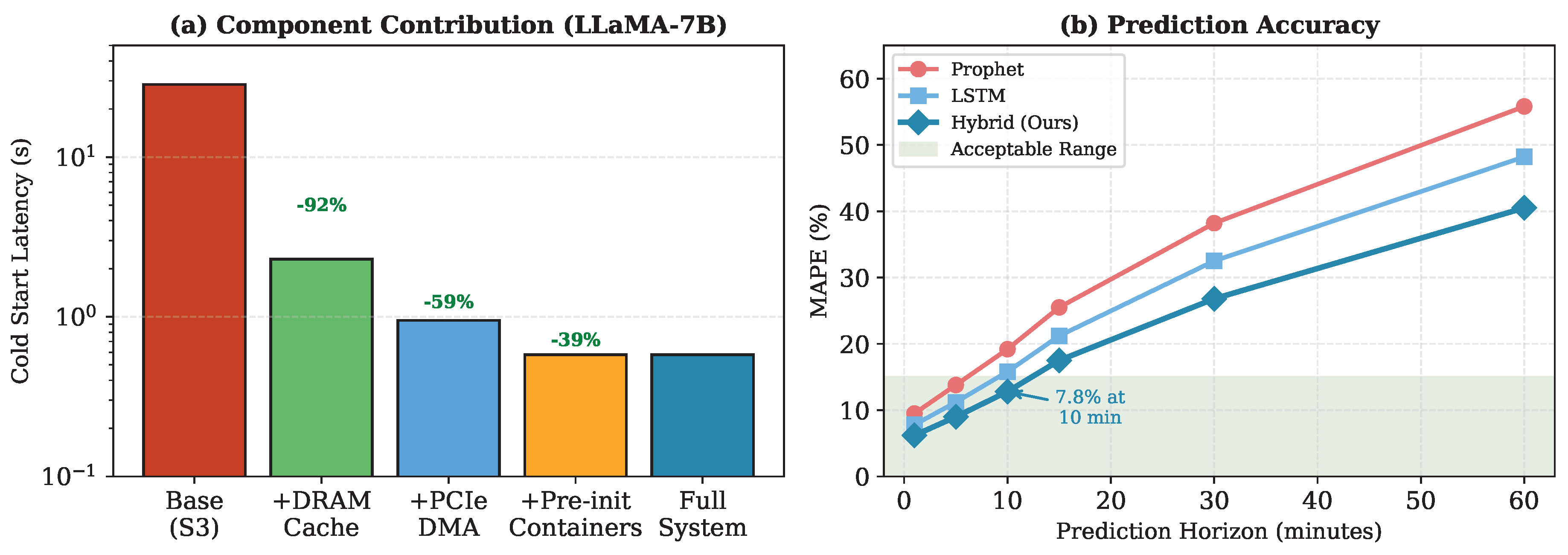

Observation 1: Request patterns are predictable. An analysis of the Azure LLM Inference traces [

12] shows that request arrival rates exhibit strong daily and weekly periodicity with a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 7.8% for 10-minute prediction horizons using our hybrid forecasting model.

Observation 2: Host DRAM is underutilized. Modern GPU servers have 512 GB–2 TB of host memory, yet LLM serving systems typically use only a fraction for KV cache overflow. Pre-staging model checkpoints in DRAM enables high-speed DMA-based transfers at 20–25 GB/s via PCIe Gen4 x16.

Observation 3: LoRA adapters dominate model diversity. In production deployments, 80–90% of model variants are LoRA fine-tunes of common base models [

13]. Efficient adapter multiplexing can dramatically reduce memory requirements for multi-tenant serving.

These observations suggest an opportunity for a co-designed system that combines intelligent memory management with predictive scaling to achieve serverless economics without sacrificing latency.

3. System Design

FlashServe is designed as a distributed serverless inference platform optimized for LLM workloads.

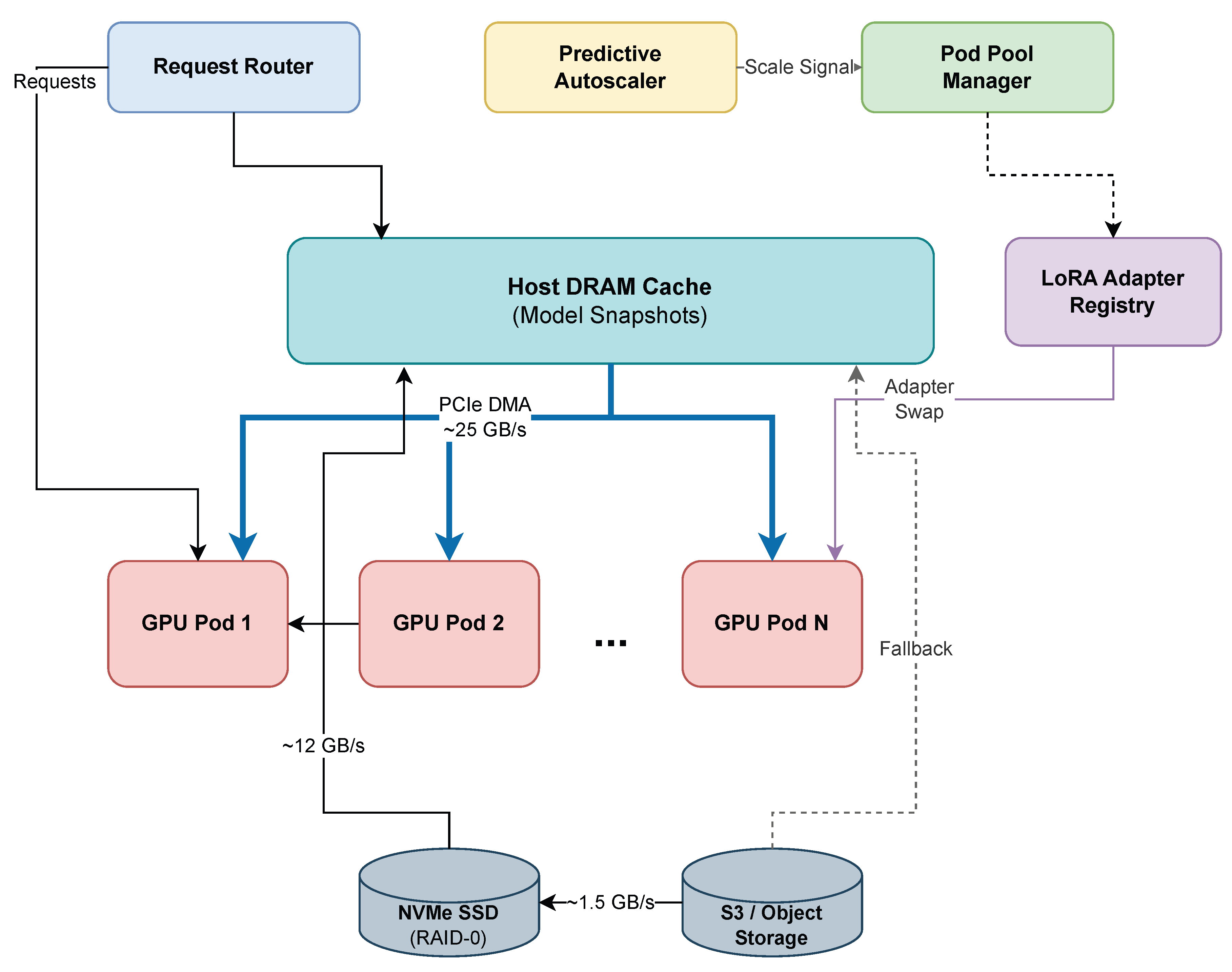

Figure 1 illustrates the overall system architecture.

3.1. Tiered Memory Snapshotting

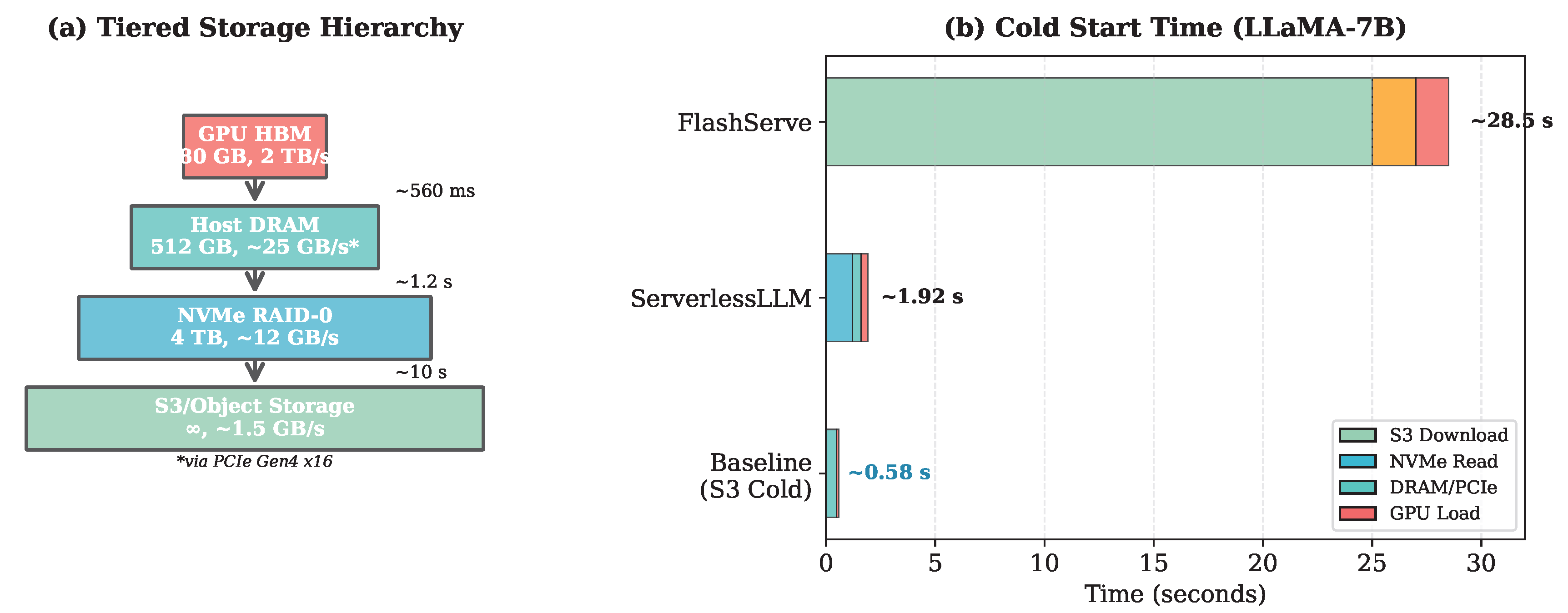

The core innovation in FlashServe is a tiered memory architecture that minimizes the distance between model checkpoints and GPU memory. We organize storage into four tiers with decreasing latency and capacity:

Tier 0 (GPU HBM): Active model weights and KV cache reside in GPU high-bandwidth memory. For an 80 GB A100 GPU, approximately 70 GB is available for model parameters after reserving space for activations and KV cache.

Tier 1 (Host DRAM): Model checkpoints are pre-loaded into host memory in a GPU-optimized format. We maintain a cluster-wide DRAM cache that can hold 8–16 model replicas per server, depending on model size.

Tier 2 (NVMe SSD): Local NVMe storage in RAID-0 configuration provides 6–7 GB/s sequential read bandwidth per drive. With two drives in RAID-0, we achieve approximately 12–13 GB/s aggregate bandwidth. Models not in DRAM cache are loaded from SSD when available.

Tier 3 (Object Storage): Cold models are fetched from S3 or equivalent object storage as a fallback, with typical bandwidth of 1–2 GB/s.

The key insight is that GPU servers have substantial unused host memory capacity. A typical 8-GPU server with 512 GB DRAM and 80 GB GPUs uses only 128 GB for system overhead and KV cache spillover, leaving 384 GB available for model staging.

3.1.1. Loading-Optimized Checkpoint Format

We design a checkpoint format optimized for sequential, chunk-based loading. Unlike standard PyTorch checkpoints that require complex deserialization, our format stores tensors in GPU-native layout with pre-computed memory offsets:

where each tensor

is stored with alignment padding to match GPU memory addressing requirements. The header contains a manifest mapping tensor names to byte offsets, enabling parallel loading of non-dependent layers.

3.1.2. High-Speed DMA Transfer

When a model must be loaded from DRAM to GPU, we leverage optimized DMA transfers through PCIe with CUDA pinned memory. The transfer process proceeds as follows:

- 1.

The scheduler identifies the target GPU and locates the model snapshot in pinned host DRAM.

- 2.

Asynchronous CUDA memory copy operations (cudaMemcpyAsync) are initiated using multiple CUDA streams to maximize PCIe bandwidth utilization.

- 3.

Tensor initialization proceeds in parallel with ongoing transfers through stream pipelining.

For a 14 GB model (LLaMA-7B in FP16), using PCIe Gen4 x16 with an effective bandwidth of approximately 25 GB/s, DMA transfer completes in approximately 560 ms. Combined with our pre-initialized container pool (described in

Section 4.1), which eliminates CUDA context initialization overhead, total cold start time reaches approximately 580 ms.

3.2. Predictive Autoscaling

Reactive autoscaling—spawning new instances in response to load increases—is fundamentally incompatible with LLM serving due to cold start latency. FlashServe instead employs predictive autoscaling that pre-warms GPU pods before anticipated demand spikes.

3.2.1. Hybrid Prediction Model

We develop a hybrid forecasting approach combining Facebook Prophet [

14] for trend and seasonality decomposition with LSTM networks for residual pattern learning. Given a time series of request rates

, the prediction for horizon

h is:

where

captures deterministic seasonality components and

models the residual sequence

.

The Prophet component decomposes the signal as:

where

represents the growth trend,

captures weekly and daily seasonality, and

models holiday effects. The LSTM processes windowed residuals through a two-layer architecture with 128 hidden units.

3.2.2. Pre-warming Strategy

Based on predicted request rates, FlashServe determines the target number of warm pods using a capacity model:

where

is the average request latency,

is the maximum batch size,

is the target GPU utilization (typically 0.7–0.8), and

provides headroom for prediction errors.

Pre-warming is triggered when exceeds current warm capacity by more than a threshold . The pre-warming lead time is set to slightly exceed the expected cold start time, ensuring pods are ready before demand arrives.

3.3. LoRA Adapter Multiplexing

Many production LLM deployments serve multiple fine-tuned model variants for different customers or use cases. Full model replication is prohibitively expensive, as each variant requires dedicated GPU memory.

FlashServe supports efficient serving of LoRA [

15] adapted models through weight sharing. LoRA represents fine-tuning updates as low-rank decompositions:

where

is a frozen pre-trained weight matrix, and

,

are trainable low-rank matrices with

.

3.3.1. Adapter Management

FlashServe maintains a shared base model in GPU memory with a pool of LoRA adapters that can be dynamically swapped. The memory overhead for a rank-16 LoRA adapter on LLaMA-7B is approximately 35 MB—0.25% of the base model size. This enables hosting 50+ adapters alongside a single base model instance.

Adapter selection follows a popularity-based caching policy. Frequently accessed adapters remain in GPU memory, while less popular ones are swapped from host DRAM on demand. The swap latency for a 35 MB adapter is under 2 ms with our optimized DMA transfer mechanism.

3.3.2. Batched Heterogeneous Inference

Following the approach of S-LoRA [

16] and dLoRA [

13], FlashServe supports batching requests destined for different LoRA adapters. The batched forward pass computes:

where

are binary masks selecting requests for each adapter. This approach achieves near-linear throughput scaling with batch size while serving heterogeneous requests.

3.4. Scheduling and Resource Management

FlashServe employs a two-level scheduling hierarchy. At the cluster level, a central scheduler assigns requests to pods based on model availability and current load. Within each pod, an iteration-level scheduler implements continuous batching [

9] for maximum GPU utilization.

3.4.1. Request Routing

Incoming requests are routed based on a cost function that balances latency and resource utilization:

where

is the estimated queue time at pod

p,

is the model loading time if needed,

is current utilization, and

are tunable weights.

The router maintains a model-to-pod affinity map updated through periodic heartbeats. Requests for cached models are preferentially routed to pods with warm instances, while requests triggering cold loads are distributed to minimize cluster-wide cold start frequency.

3.4.2. Memory Management

GPU memory is partitioned into regions for model weights, KV cache, and activations. FlashServe implements PagedAttention [

8] for KV cache management, achieving near-zero memory fragmentation.

When memory pressure exceeds a threshold, FlashServe employs a hierarchical eviction policy: (1) evict KV cache pages for completed or preempted requests, (2) swap inactive LoRA adapters to host memory, and (3) migrate entire models to less-loaded pods.

4. Implementation

We implement FlashServe in approximately 12,000 lines of Python and C++, building on vLLM [

8] for the inference engine and Kubernetes for container orchestration.

4.1. Pre-initialized Container Pool

A critical optimization in FlashServe is the

pre-initialized container pool, which eliminates the GPU warmup overhead shown in

Table 1. Traditional cold starts require initializing CUDA contexts, allocating GPU page tables, and loading the Python runtime—operations that typically take 500–800 ms.

FlashServe maintains a pool of “warm containers” where CUDA contexts are already established and the inference runtime is fully initialized, but GPU memory remains empty (no model weights loaded). When a cold start is triggered, FlashServe assigns one of these pre-initialized containers and only performs the model weight transfer via DMA. This design reduces the cold start critical path to purely the data transfer time (∼560 ms for a 14 GB model), plus minimal scheduling overhead (∼20 ms).

The container pool size is determined by the predictive autoscaler based on anticipated demand. Containers are recycled after request completion: model weights are evicted from GPU memory, but the CUDA context remains active for future use.

4.2. Checkpoint Conversion Pipeline

Model checkpoints are converted from standard formats (PyTorch, SafeTensors) to our loading-optimized format using an offline pipeline. The conversion process: (1) loads the original checkpoint and identifies tensor dependencies, (2) reorders tensors to maximize sequential access patterns, (3) applies alignment padding and generates the manifest header, and (4) optionally applies quantization (INT8, FP8) for reduced storage.

Conversion overhead is a one-time cost of 2–5 minutes per model, amortized across all subsequent deployments.

4.3. DMA Transfer Optimization

We optimize host-to-GPU transfers using CUDA’s pinned memory APIs and asynchronous streaming. Key optimizations include: (1) chunk size tuning (2 MB optimal for A100 with PCIe Gen4), (2) double-buffering to overlap transfers with GPU initialization, and (3) NUMA-aware memory allocation to minimize cross-socket traffic.

For cross-node scenarios where models must be fetched from remote servers, we leverage RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) via InfiniBand to bypass CPU involvement. With ConnectX-6 100 Gbps NICs, remote transfers achieve approximately 12 GB/s, which is slower than local DMA but still significantly faster than object storage.

4.4. Prediction Service

The prediction service runs as a separate microservice, consuming request metrics from Prometheus and publishing scaling decisions to the Kubernetes HPA controller. The Prophet model is retrained daily on a rolling 14-day window, while LSTM weights are updated hourly through online learning.

5. Evaluation

We evaluate FlashServe on a cluster of 8 servers, each equipped with 8 NVIDIA A100-80GB GPUs connected via PCIe Gen4 x16, 512 GB DDR4 memory, two 2 TB NVMe SSDs in RAID-0 configuration (achieving ∼12 GB/s aggregate read bandwidth), and ConnectX-6 100 Gbps InfiniBand NICs for inter-node communication. The cluster runs Ubuntu 22.04 with CUDA 12.1 and PyTorch 2.1.

5.1. Workloads and Baselines

We use the Azure Functions trace dataset [

3] to generate realistic request arrival patterns for load testing. Following the common practice in prior work [

6], we apply a uniform scaling factor to match typical LLM serving rates (10–500 requests/second) while preserving the daily periodicity patterns. For prediction model evaluation, we use the Azure LLM Inference traces [

12].

We evaluate three model sizes from the LLaMA-2 family [

2]: 7B, 13B, and 70B parameters. For LoRA experiments, we generate synthetic adapters with ranks 8, 16, and 32 to cover typical production configurations.

Baselines include:

5.2. Cost Model

We model GPU costs based on AWS p4d.24xlarge on-demand pricing ($32.77/hour for 8 A100 GPUs, approximately $4.10 per GPU-hour). Costs are calculated as GPU-seconds multiplied by the per-second rate. We focus on GPU compute costs because they dominate total cost of ownership (TCO) for inference workloads. While FlashServe utilizes substantial host DRAM for model caching, DDR4/DDR5 memory costs less than 1% of HBM per gigabyte ($5–10/GB vs. $1000+/GB for HBM), making the additional DRAM overhead negligible in TCO calculations. Normalized cost is computed as the ratio of total GPU-seconds consumed relative to the baseline system.

5.3. Cold Start Latency

Figure 2 illustrates the tiered memory hierarchy and cold start breakdown.

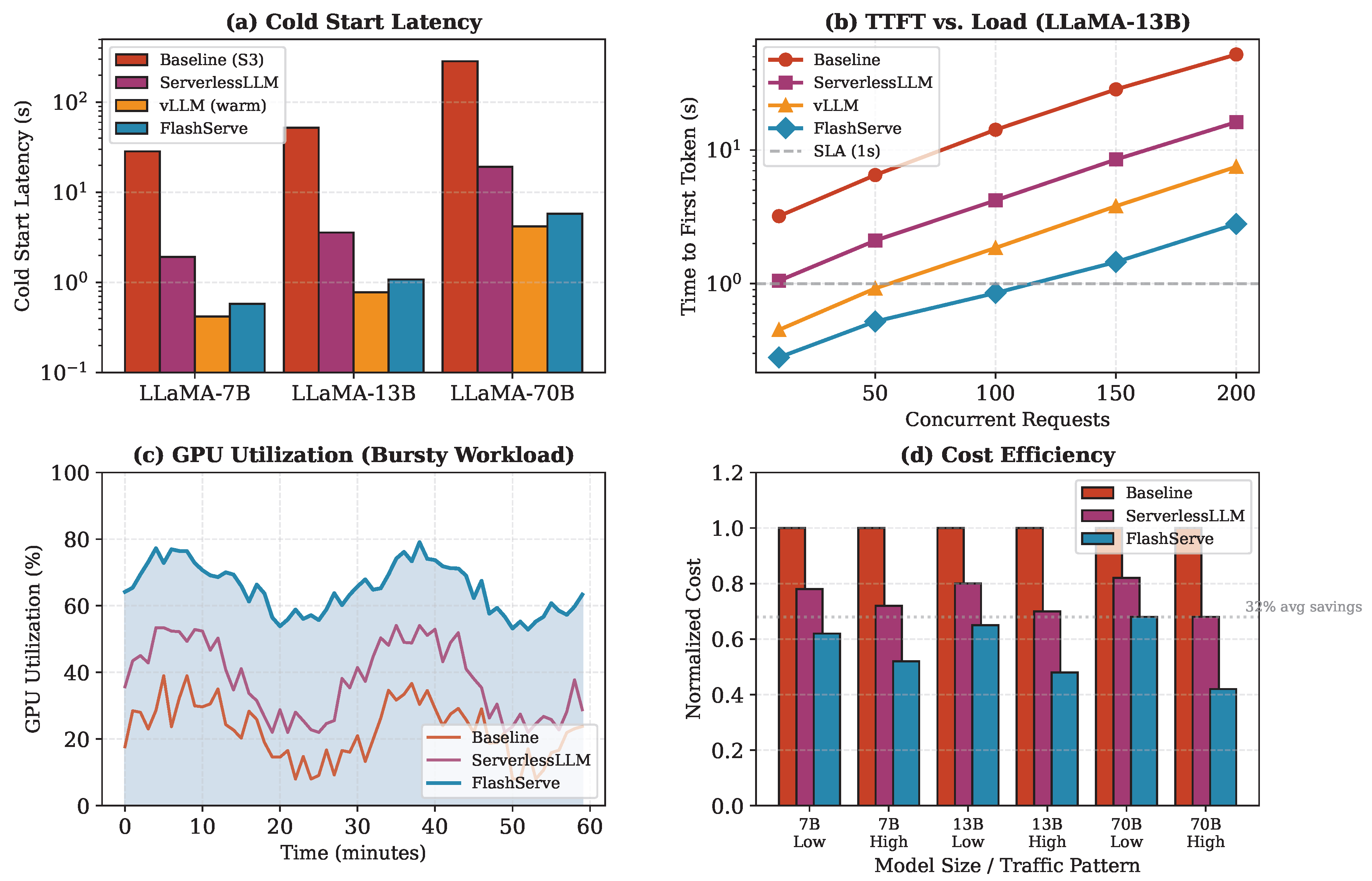

Table 2 presents cold start latencies across model sizes.

FlashServe achieves sub-second cold start for the 7B model and approximately 1 second for the 13B model. The improvements come from two sources: (1) DRAM-tier caching with optimized PCIe DMA transfers providing ∼25 GB/s bandwidth (vs. 12–13 GB/s for NVMe), and (2) the pre-initialized container pool that eliminates 500–800 ms of CUDA context initialization overhead (see

Section 4.1).

The 70B model requires 5.8 seconds due to its larger size (140 GB in FP16), but this still represents a 49× improvement over baseline S3 loading. Note that FlashServe’s cold start is slower than vLLM with pre-loaded models (warm), as DMA transfer overhead is unavoidable; however, FlashServe provides serverless elasticity that warm instances cannot.

5.4. End-to-End Latency

Figure 3 shows the prediction model performance on the Azure trace workload. The hybrid Prophet-LSTM approach achieves MAPE of 7.8% at a 10-minute horizon, enabling accurate pre-warming decisions.

Figure 4(b) shows time-to-first-token (TTFT) under varying load. FlashServe maintains sub-second TTFT up to 150 concurrent requests, while baselines exceed the 1-second SLA at much lower load levels. The improvement stems from predictive pre-warming that reduces the frequency of cold starts during traffic ramps.

5.5. Resource Utilization and Cost

Figure 4(c) demonstrates GPU utilization under a bursty workload pattern. FlashServe achieves average utilization of 68%, compared to 42% for ServerlessLLM and 25% for the baseline. The improvement stems from predictive pre-warming that reduces cold starts during traffic ramps and LoRA multiplexing that improves resource sharing.

Figure 4(d) shows normalized cost (GPU-seconds relative to baseline) across configurations. FlashServe reduces costs by 32–58% compared to baseline, with larger savings under bursty (high variance) traffic patterns where predictive scaling is most beneficial. On average across all evaluated workloads, FlashServe achieves 32% cost reduction.

5.6. LoRA Multiplexing

Figure 5 illustrates the LoRA adapter multiplexing architecture.

Table 3 presents throughput results when serving multiple LoRA variants.

FlashServe supports 128 LoRA adapters with only 4% throughput degradation compared to single-adapter serving. The optimized DMA-based adapter swapping reduces swap latency to under 2.5 ms, enabling seamless switching between adapters without visible latency impact to end users.

5.7. Ablation Study

Figure 6 presents ablation results isolating the contribution of each FlashServe component.

Tiered snapshotting with DRAM caching provides the largest improvement (moving from 28.5 s baseline to 2.3 s), followed by optimized DMA transfers (2.3 s to 0.95 s). The pre-initialized container pool further reduces latency to 0.58 s by eliminating CUDA context initialization. Predictive autoscaling primarily improves TTFT under bursty loads rather than raw cold start time, by pre-warming pods before demand spikes. LoRA multiplexing reduces memory costs without significant latency impact.

The prediction model comparison in

Figure 6(b) shows that the hybrid Prophet-LSTM approach outperforms Prophet-only and LSTM-only baselines across all horizons, with the advantage most pronounced at longer horizons (30–60 minutes) where seasonal decomposition captures weekly patterns that pure LSTM models struggle to learn.

Our improvements over ServerlessLLM come from three sources: (1) faster DRAM-to-GPU transfer path via PCIe DMA, (2) pre-initialized containers that eliminate CUDA warmup, and (3) predictive autoscaling for reduced cold start frequency. The ablation study isolates these effects.

6. Related Work

Serverless ML Inference. INFless [

6] introduced serverless inference with batching and heterogeneous resources. Tetris [

7] optimized memory-efficient model hosting. Mark [

17] proposed model-aware resource allocation. These systems target traditional ML models rather than LLMs.

LLM Serving Systems. vLLM [

8] introduced PagedAttention for efficient memory management. Orca [

9] proposed iteration-level scheduling. DeepSpeed-Inference [

10] provides optimized kernels and parallelism strategies. FlexGen [

18] enables offloading to CPU and disk for memory-constrained scenarios.

Cold Start Optimization. ServerlessLLM [

4] pioneered multi-tier checkpoint loading for LLMs using NVMe caching. Clockwork [

19] introduced predictive scheduling for ML inference with strict latency guarantees. Shepherd [

20] proposed proactive model loading based on workload prediction. FlashServe builds on these approaches with DRAM-tier caching, pre-initialized containers, and optimized PCIe transfers.

LoRA Serving. S-LoRA [

16] and Punica [

21] enable batched serving of multiple LoRA adapters. dLoRA [

13] introduces dynamic adapter merging and migration. FlashServe integrates LoRA multiplexing with fast adapter swapping via optimized DMA.

Predictive Autoscaling. Prior work on predictive scaling for web services [

22] and container orchestration [

23] provides foundations. FlashServe adapts these techniques with Prophet-LSTM hybrid models tuned for LLM workload characteristics.

7. Discussion and Limitations

While FlashServe demonstrates improvements in serverless LLM deployment, several limitations merit discussion.

Hardware Requirements. FlashServe’s performance depends on sufficient host memory capacity to cache model snapshots. Deployments with limited DRAM (less than 256 GB per server) will see reduced benefits, as fewer models can be cached in the fast tier.

PCIe Bandwidth Ceiling. Our approach is fundamentally limited by PCIe Gen4 bandwidth (∼25 GB/s effective). Future systems with PCIe Gen5 (doubling theoretical bandwidth) or CXL memory pooling could further reduce cold start times.

Container Pool Overhead. The pre-initialized container pool consumes GPU context resources even when idle. We mitigate this by sizing the pool based on predicted demand, but sudden traffic spikes beyond predictions may still trigger full cold starts including CUDA initialization.

Prediction Accuracy. The hybrid prediction model achieves reasonable accuracy for workloads with regular patterns but may struggle with highly irregular or adversarial traffic. Incorporating additional signals (e.g., upstream events, time-of-day context) could improve robustness.

Multi-Model Complexity. While LoRA multiplexing is efficient for adapter-based fine-tuning, serving many distinct base models remains challenging. Future work could explore cross-model weight sharing through techniques like model merging.

Evaluation Scope. Our evaluation focuses on text generation workloads. Performance characteristics may differ for other modalities (vision, audio) or task types (retrieval-augmented generation).

8. Conclusions

This paper presented FlashServe, a serverless inference system that addresses the cold start challenge in LLM deployment through tiered memory snapshotting, pre-initialized container pools, predictive autoscaling, and LoRA adapter multiplexing. By eliminating CUDA context initialization overhead and leveraging high-speed PCIe DMA transfers from host DRAM, FlashServe achieves cold start latencies under 0.6 seconds for 7B-parameter models, representing improvements of 3.3–49× over prior approaches. Under realistic bursty workloads, FlashServe reduces GPU costs by 32% on average while meeting sub-second latency SLAs for 95% of requests.

These results represent meaningful progress toward practical serverless LLM deployment, though substantial work remains to overcome PCIe bandwidth limitations and improve prediction accuracy for irregular workloads. We believe the principles demonstrated in FlashServe—intelligent memory hierarchy exploitation, runtime pre-initialization, predictive resource management, and efficient model multiplexing—will inform future serverless AI systems as models continue to grow in size and importance.

References

- T. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. D. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell et al., “Language models are few-shot learners,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, pp. 1877–1901, 2020.

- H. Touvron, L. Martin, K. Stone, P. Albert, A. Almahairi, Y. Babaei, N. Bashlykov, S. Batra, P. Bhargava, S. Bhosale et al., “Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, 2023.

- M. Shahrad, R. Fonseca, I. Goiri, G. Chaudhry, P. Batum, J. Cooke, E. Laureano, C. Tresness, M. Russinovich, and R. Bianchini, “Serverless in the wild: Characterizing and optimizing the serverless workload at a large cloud provider,” in 2020 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 20), 2020, pp. 205–218.

- Y. Fu, L. Xue, Y. Huang, A.-O. Brabete, D. Ustiugov, Y. Patel, and L. Mai, “ServerlessLLM: Low-latency serverless inference for large language models,” in 18th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 24), 2024, pp. 135–153.

- E. Jonas, J. Schleier-Smith, V. Sreekanti, C.-C. Tsai, A. Khandelwal, Q. Pu, V. Shankar, J. Carreira, K. Krauth, N. Yadwadkar et al., “Cloud programming simplified: A Berkeley view on serverless computing,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.03383, 2019.

- Y. Yang, L. Zhao, Y. Li, H. Zhang, J. Li, M. Zhao, X. Chen, and K. Li, “INFless: A native serverless system for low-latency, high-throughput inference,” in Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, 2022, pp. 768–781.

- J. Li, L. Zhao, Y. Yang, Y. Li, and K. Zhan, “Tetris: Memory-efficient serverless inference through tensor sharing,” in 2022 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 22), 2022, pp. 473–488.

- W. Kwon, Z. Li, S. Zhuang, Y. Sheng, L. Zheng, C. H. Yu, J. Gonzalez, H. Zhang, and I. Stoica, “Efficient memory management for large language model serving with PagedAttention,” in Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2023, pp. 611–626.

- G.-I. Yu, J. S. Jeong, G.-W. Kim, S. Kim, and B.-G. Chun, “Orca: A distributed serving system for transformer-based generative models,” in 16th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 22), 2022, pp. 521–538.

- R. Y. Aminabadi, S. Rajbhandari, A. A. Awan, C. Li, D. Li, E. Zheng, O. Ruwase, S. Smith, M. Zhang, J. Rasley, and Y. He, “DeepSpeed-Inference: Enabling efficient inference of transformer models at unprecedented scale,” in SC22: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis. IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–15.

- Z. Li, L. Zheng, Y. Zhong, Y. Sheng, S. Zhuang, C. H. Yu, Y. Liu, J. E. Gonzalez, H. Zhang, and I. Stoica, “AlpaServe: Statistical multiplexing with model parallelism for deep learning serving,” in 17th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 23), 2023, pp. 663–679.

- Microsoft Azure, “Azure Public Dataset: LLM inference traces,” https://github.com/Azure/AzurePublicDataset, 2023.

- B. Wu, R. Zhu, Z. Zhang, P. Sun, X. Liu, and X. Jin, “dLoRA: Dynamically orchestrating requests and adapters for LoRA LLM serving,” in 18th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 24), 2024, pp. 911–927.

- S. J. Taylor and B. Letham, “Forecasting at scale,” The American Statistician, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 37–45, 2018.

- E. J. Hu, Y. Shen, P. Wallis, Z. Allen-Zhu, Y. Li, S. Wang, L. Wang, and W. Chen, “LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685, 2021.

- Y. Sheng, S. Cao, D. Li, C. Hooper, N. Lee, S. Yang, C. Chou, B. Zhu, L. Zheng, K. Keutzer, J. E. Gonzalez, and I. Stoica, “S-LoRA: Serving thousands of concurrent LoRA adapters,” in Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, vol. 6, 2024, pp. 296–311.

- C. Zhang, M. Yu, W. Wang, and F. Yan, “MARK: Exploiting cloud services for cost-effective, SLO-aware machine learning inference serving,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.01408, 2019.

- Y. Sheng, L. Zheng, B. Yuan, Z. Li, M. Ryabinin, B. Chen, P. Liang, C. Ré, I. Stoica, and C. Zhang, “FlexGen: High-throughput generative inference of large language models with a single GPU,” in International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 31 094–31 116.

- A. Gujarati, R. Karber, S. Dharanipragada, S. Misailovic, D. Zhang, K. Nahrstedt, and P. Druschel, “Serving DNNs like clockwork: Performance predictability from the bottom up,” in 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), 2020, pp. 443–462.

- H. Zhang, Y. Tang, A. Khandelwal, and I. Stoica, “Shepherd: Serving DNNs in the wild,” in 20th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 23), 2023, pp. 787–808.

- L. Chen, Z. Ye, Y. Wu, D. Zhuo, L. Ceze, and A. Krishnamurthy, “Punica: Multi-tenant LoRA serving,” Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, vol. 6, pp. 607–622, 2024.

- N. Roy, A. Dubey, and A. Gokhale, “Efficient autoscaling in the cloud using predictive models for workload forecasting,” in 2011 IEEE 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing. IEEE, 2011, pp. 500–507.

- K. Rzadca, P. Findeisen, J. Swiderski, P. Zych, P. Broniek, J. Kusmierek, P. Nowak, B. Strack, P. Witusowski, S. Hand, and J. Wilkes, “Autopilot: Workload autoscaling at Google,” in Proceedings of the Fifteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, 2020, pp. 1–16.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).