1. Introduction

Legal judgment prediction has emerged as a critical application domain at the intersection of artificial intelligence and legal informatics, with profound implications for judicial decision support systems, legal consultation services, and case outcome assessment [

1,

2,

3]. The task involves predicting judicial outcomes based on textual descriptions of case facts, requiring sophisticated understanding of legal concepts, factual elements, and their interrelationships within the judicial reasoning framework. In multi-label civil judgment prediction—such as marital property allocation, child custody arrangements, and divorce grounds—these legal elements naturally form a structured system of dependencies. When viewed through a graph-theoretic lens, each case and its annotated labels constitute a case–label bipartite graph, whose induced label co-occurrence graph exhibits cluster-level regularities as well as asymmetric sparsity patterns across different legal factors. Such structures motivate learning approaches that are able to respect both the symmetric and asymmetric patterns inherent in legal judgment graphs, and that remain compatible with downstream graph-based reasoning or GNN architectures.

Beyond strictly predictive tasks, adjacent strands of legal NLP research investigate long-document summarization pipelines for case law [

4], Arabic judicial decision support platforms that integrate retrieval with classification [

5], and large-scale crime prediction surveys that contextualize machine learning deployments within policing workflows [

6,

7]. Hybrid deep neural frameworks tailored for multi-task legal analytics [

8] further illustrate the diversity of architectures required to reason over procedural posture, statutory factors, and evidentiary descriptions. However, these models often overlook the structural regularities arising from the graph organization of legal elements and their co-occurrence patterns, which contain both symmetric correlations within thematic clusters and asymmetric dependencies associated with rare or sparsely connected labels.

Recent advances in deep learning have significantly improved legal judgment prediction through sophisticated text representation and classification techniques. Traditional machine learning approaches including support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting methods [

9,

10] rely on handcrafted features and thus struggle to capture the deeper structural dependencies across labels that naturally emerge from the underlying legal judgment graph. Deep neural architectures including convolutional neural networks [

11], recurrent neural networks with LSTM and GRU cells [

12], and attention-based models [

13] are able to discover hierarchical textual patterns automatically, yet they still lack explicit mechanisms to incorporate the symmetric or asymmetric label interactions encoded in the label graph. Furthermore, these task-specific architectures must be trained from scratch and often require substantial labeled data and computational resources, limiting their applicability to domains such as family law where curated datasets are expensive to obtain.

Pre-trained language models have revolutionized natural language processing by enabling effective transfer learning from large-scale unsupervised corpora to downstream tasks. Models such as BERT [

14] and domain-adapted variants [

15] capture rich linguistic and semantic knowledge during pre-training and have demonstrated strong performance in legal text analysis. However, standard full-parameter fine-tuning faces several critical challenges. First, updating all model parameters is computationally expensive in terms of memory, storage, and training time. Second, full fine-tuning increases the risk of catastrophic forgetting, potentially disrupting previously learned linguistic or structural knowledge [

16]. Third, uniform learning rate schedules may fail to reconcile broad domain adaptation objectives with the fine-grained optimization required to capture asymmetric judgment patterns across labels—patterns which, from a graph-structural perspective, correspond to highly imbalanced or weakly connected regions of the label co-occurrence graph.

Large language models with billions of parameters [

17,

18] encode extensive world knowledge, including legal terminology and reasoning heuristics, but adapting them reliably to specialized legal tasks remains computationally challenging. Recent applications have explored LLMs for legal question answering, contract analysis, and judgment prediction [

19,

20,

21], while broader scholarship emphasizes responsible governance in emerging socio-technical domains [

22]. The rapid diffusion of LLMs into safety-critical environments such as neurosurgical simulation [

23], autonomous control [

24], and digital forensics [

25] further underscores the need for robust, well-structured fine-tuning strategies. Although prompt engineering offers a lightweight alternative, it is often insufficient for complex multi-label classification tasks that require nuanced modeling of the structured, graph-like dependencies among legal elements [

26]. These limitations create an opportunity for parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods that can capture both textual and structural patterns in legal judgment graphs while remaining computationally affordable.

Parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods have emerged as a promising solution to adapt large pre-trained models while maintaining computational efficiency. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) represents a breakthrough in this direction by constraining weight updates to low-rank subspaces, reducing trainable parameters to a small fraction of the original model while achieving performance comparable to full fine-tuning [

27]. The fundamental insight underlying LoRA is that pre-trained language models exhibit intrinsically low-dimensional structures, a property that resonates with the symmetry patterns commonly observed in graph-structured data. When legal judgments are represented through a case–label bipartite graph, or through its induced symmetric label co-occurrence matrix, many legal elements display clustered, approximately symmetric correlations, whereas rare labels form highly asymmetric, sparsely connected regions. LoRA’s low-rank parameterization provides a natural mechanism for adapting the model along these dominant symmetric directions while avoiding overfitting to noisy or weakly connected asymmetric substructures of the legal judgment graph.

By decomposing weight updates into low-rank matrices, LoRA enables efficient domain adaptation while preserving the linguistic knowledge encoded during pre-training. Despite its effectiveness, existing applications of LoRA primarily employ single-stage fine-tuning with uniform learning rates, potentially overlooking the structural asymmetry inherent in legal label graphs and missing opportunities for progressive knowledge acquisition through curriculum-inspired training strategies. In particular, symmetric clusters of frequently co-occurring labels may be learned rapidly, whereas asymmetric, low-frequency legal elements require more conservative refinement to avoid gradient instability and catastrophic forgetting.

To address these limitations and harness the full potential of large language models for legal judgment prediction while maintaining parameter efficiency, this paper proposes a two-stage sequential fine-tuning framework based on LoRA that decomposes the learning process into progressive knowledge acquisition stages with differentiated learning rates. The key insight is that legal judgment prediction requires both broad legal domain knowledge—corresponding to learning the approximately symmetric structure of the label co-occurrence graph—and fine-grained relationship modeling between specific factual elements and judicial outcomes, which often reside in asymmetric or sparsely connected regions of the graph. By separating these learning objectives into distinct sequential stages with appropriately calibrated learning rates, the proposed approach enables the model to first establish comprehensive domain understanding through rapid exploration of symmetric patterns, followed by refined optimization of decision boundaries through conservative updates that stabilize learning on asymmetric label structures.

The main contributions of this work are:

This paper proposes a two-stage sequential fine-tuning framework based on Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) that decomposes legal judgment prediction into progressive knowledge acquisition stages. Stage 1 performs legal knowledge pre-tuning with a higher learning rate (), enabling the model to rapidly capture dominant, approximately symmetric structures in the label co-occurrence graph, while Stage 2 conducts judgment relation fine-tuning with a lower learning rate () that refines asymmetric and low-frequency label relationships, achieving efficient transfer learning with only 0.21% trainable parameters.

This work presents a comprehensive analysis of the theoretical foundations and practical implementation of LoRA-based parameter-efficient fine-tuning for legal text classification. By aligning low-rank parameterization with the structural regularities of the legal judgment graph, the framework provides a symmetry-aware adaptation strategy, along with detailed formulations of optimization objectives and gradient computation procedures for both training stages.

Extensive experiments are conducted on a Chinese legal case dataset comprising divorce-related judgments with 20 multi-label categories. The results demonstrate that the proposed two-stage approach achieves superior performance compared to single-stage fine-tuning baselines across multiple evaluation metrics including macro F1-score, Hamming Loss, and accuracy, validating that separating symmetric and asymmetric learning behaviors through curriculum-inspired sequential optimization is effective for complex legal domain adaptation tasks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on legal judgment prediction, graph-based representations, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques for large language models.

Section 3 presents the detailed methodology including problem formulation, the graph-theoretic interpretation of legal label structure, LoRA fundamentals, the proposed two-stage sequential fine-tuning strategy, and implementation details.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, dataset characteristics, evaluation metrics, and presents comprehensive results including performance comparisons, ablation studies, and hyperparameter sensitivity analysis. Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings and discusses future research directions for structure-aware, parameter-efficient adaptation of large language models in legal and other graph-structured domains.

1.1. Legal Judgment Prediction

Legal judgment prediction has attracted significant research attention in legal artificial intelligence, evolving from traditional machine learning approaches to sophisticated neural architectures. Early work employed feature engineering combined with classifiers including support vector machines [

9,

28], random forests [

10], and logistic regression, achieving reasonable performance but requiring substantial domain expertise for feature design. These methods typically extract statistical features, n-gram representations, and manually crafted legal concept indicators from case documents, but they do not explicitly model the structural dependencies among legal elements that naturally arise in case–label bipartite graphs or label co-occurrence graphs.

Deep learning approaches have demonstrated superior performance by automatically learning hierarchical representations from legal texts. Convolutional neural networks [

11] extract n-gram patterns at multiple scales through hierarchical convolution and pooling operations. Recurrent neural networks including LSTM and GRU variants [

12,

29] capture sequential dependencies in legal narratives through recurrent connections. Attention-based architectures [

13,

27,

30] enable models to focus on salient textual segments relevant to specific legal elements. More recently, graph neural networks (GNNs) [

2,

31] have been introduced to model relationships among legal articles, precedents, and factual elements by treating them as nodes in a heterogeneous graph whose edges encode citation, semantic, or co-occurrence relations. These approaches leverage advances in graph connectivity theory [

32,

33,

34] and network diagnosability [

35,

36,

37,

38], enabling reasoning over both symmetric structural clusters and asymmetric sparse connections—a perspective highly relevant to multi-label divorce judgments where legal elements exhibit clustered co-occurrence patterns alongside rare, weakly connected labels.

Legal-specific hybrid architectures including MPBFN [

39], LADAN [

40], and Mulan [

41] integrate multiple attention heads or feedback pathways to distinguish confusing statutes under multi-label supervision, while reinforcement learning and rationale extraction frameworks [

42,

43] emphasize interpretable identification of decisive criminal elements. Knowledge-graph enhanced encoders [

44] further demonstrate the benefit of jointly modeling semantic and topological cues, underscoring the importance of representing legal elements not only as independent labels but as nodes embedded in a graph structure that exhibits both symmetry and asymmetry.

Pre-trained language models have achieved state-of-the-art performance across legal NLP tasks. BERT [

14] and its variants provide contextualized representations through bidirectional Transformer encoders trained on masked language modeling objectives. Domain-specific variants and specialized architectures have been developed through continued pre-training on legal corpora, achieving enhanced performance on legal text understanding tasks [

15,

45]. Recent work explores multi-task learning [

46,

47,

48], contrastive learning [

49], and graph-enhanced methods [

31] to further improve prediction accuracy by exploiting structural regularities in legal judgment graphs.

However, most existing approaches require full fine-tuning of model parameters, leading to substantial computational costs when adapting large pre-trained models. Moreover, these methods rarely incorporate the symmetry characteristics of legal label co-occurrence graphs or explicitly address the asymmetric nature of low-frequency legal elements. This limitation motivates the exploration of parameter-efficient fine-tuning strategies that can adapt large language models while respecting the underlying graph structure of legal judgments and remaining compatible with hybrid GNN-based or graph-informed reasoning frameworks.

1.2. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning for Large Language Models

Parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods have emerged as a critical research direction for adapting large pre-trained models to downstream tasks while maintaining computational efficiency. These approaches aim to achieve performance comparable to full fine-tuning while updating only a small fraction of parameters, significantly reducing memory requirements, training time, and storage costs. In tasks such as legal judgment prediction, where labels naturally form a structured and partially symmetric co-occurrence graph, parameter-efficient methods are particularly attractive because they preserve the core pre-trained knowledge needed to capture global regularities while enabling targeted updates on structurally sensitive or sparsely connected regions of the label graph.

Various parameter-efficient methods have been proposed for adapting pre-trained models. Adapter modules insert trainable bottleneck layers between frozen Transformer blocks, enabling task-specific adaptation through lightweight neural networks. Prompt-based methods optimize continuous embeddings while keeping model parameters frozen [

19,

20]. Other approaches update only specific parameter subsets, achieving competitive performance with minimal trainable parameters [

27]. These methods can be viewed as implicitly leveraging symmetry in parameter-space modifications—restricting updates to subspaces that preserve the model’s pre-trained structural balance—while avoiding disruptive changes that may distort relational patterns encoded during pre-training.

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) represents a particularly effective parameter-efficient approach based on the hypothesis that weight updates during fine-tuning exhibit low intrinsic dimensionality. By decomposing weight updates into low-rank matrices, LoRA achieves parameter efficiency while maintaining expressiveness. This low-rank decomposition naturally aligns with the structural perspective of many legal prediction tasks: the fine-grained relations between legal elements often exhibit clustered or quasi-symmetric structures, while rare legal labels introduce asymmetric sparsity. A low-rank update provides a smooth, symmetry-preserving modification to the underlying representation space, making it well-suited for domains where prediction targets are embedded in label graphs with heterogeneous connectivity and varying degrees of structural regularity. LoRA has demonstrated effectiveness across natural language understanding, text generation, and specialized applications [

27,

45].

Despite the success of parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods, most existing work employs single-stage optimization with uniform learning rates. Such strategies may overlook structural differences across regions of the task’s label or relational graph, where dense and symmetric clusters may tolerate aggressive updates, while sparse or weakly connected nodes require more conservative adaptation. Recent research suggests that staged learning strategies with varying difficulty levels or learning rates can enhance model performance and training stability [

50,

51]. However, applications of these principles to parameter-efficient fine-tuning for legal domain adaptation—especially those leveraging the symmetric or asymmetric topology of legal element graphs—remain largely unexplored.

This work bridges this gap by proposing a two-stage sequential fine-tuning framework that combines the parameter efficiency of LoRA with curriculum-inspired progressive learning strategies. The design implicitly respects the structural properties of the legal judgment label graph by allowing broad domain knowledge to be acquired through coarse, symmetry-preserving updates in Stage 1, followed by fine-grained refinement in Stage 2 that selectively adjusts representations aligned with asymmetric or sparsely connected judgment elements. This two-stage approach enables more stable and structure-aware legal domain adaptation while maintaining a minimal trainable parameter footprint.

2. Methodology

2.1. Overview

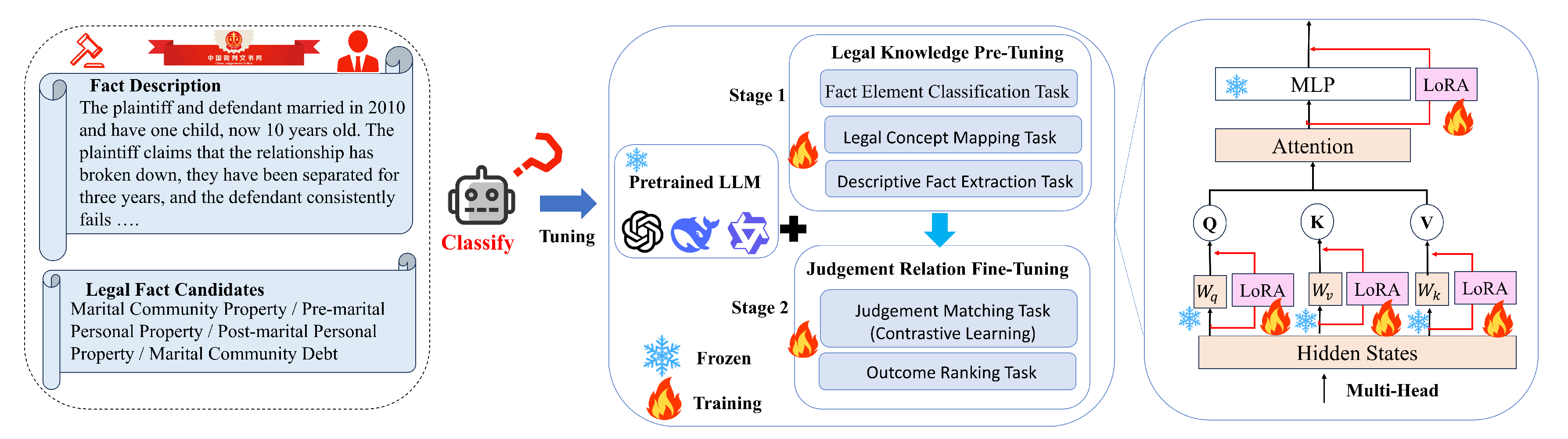

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed LawLLM-DS framework, which consists of three key components: (1) a base large language model with frozen pre-trained weights, (2) Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) modules for parameter-efficient fine-tuning, and (3) a two-stage sequential training strategy with differentiated learning rates. The framework takes legal case fact descriptions as input and predicts multiple judgment labels through progressive knowledge acquisition.

From a structural perspective, the twenty legal judgment labels form a label co-occurrence graph whose connectivity exhibits partially symmetric clustering (e.g., child-related labels often co-occur) alongside asymmetric sparsity for rare judgment elements. These structural properties motivate a staged adaptation strategy: Stage 1 performs legal knowledge pre-tuning with a higher learning rate () to rapidly internalize global, symmetry-driven regularities in the label graph, while Stage 2 refines decision boundaries with a reduced learning rate (), enabling the model to adjust representations associated with sparsely connected or structurally asymmetric label nodes. By introducing separate LoRA parameter sets for each stage, LawLLM-DS achieves structure-aware domain adaptation while maintaining parameter efficiency with only 0.21% trainable parameters, and remains fully compatible with downstream GNN-based or graph-informed reasoning modules.

2.2. Problem Formulation

The primary objective is to harness large language models for multi-label legal judgment prediction through parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Formally, given a legal case dataset

, where

denotes fact description texts and

represents the set of legal element labels, the objective is to learn a mapping:

where

represents the input fact description,

is the predicted label set, and

denotes the frozen pre-trained model parameters.

In most real-world civil law datasets, the label space exhibits a graph-like dependency structure characterized by local symmetric clusters (e.g., child-support labels) and asymmetric edges arising from highly sparse judgment factors. A parameter-efficient approach is therefore desirable to maintain global semantic coherence learned from pre-training while allowing targeted, low-dimensional adjustments aligned with the structural properties of the label graph.

Given computational constraints and catastrophic forgetting risks [

16], we adopt Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) for efficient adaptation. Recognizing that legal judgment prediction requires both broad legal domain knowledge and fine-grained relationship modeling that reflects the symmetric–asymmetric topology of the label co-occurrence graph, we propose a two-stage sequential fine-tuning strategy with differentiated learning rates tailored to these structural considerations.

2.3. Low-Rank Adaptation for Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

Pre-trained language models typically contain numerous dense layers performing matrix multiplications, where weight matrices maintain full rank during standard fine-tuning. However, this approach proves computationally prohibitive and susceptible to overfitting when adapting large models to specialized domains. Recent research demonstrates that pre-trained language models exhibit intrinsically low-dimensional structures, suggesting that task-specific adaptation can be achieved through updates in a constrained low-rank subspace rather than the full parameter space [

45]. This principle motivates LoRA, which achieves efficient fine-tuning by decomposing weight updates into low-rank matrices while keeping original parameters frozen.

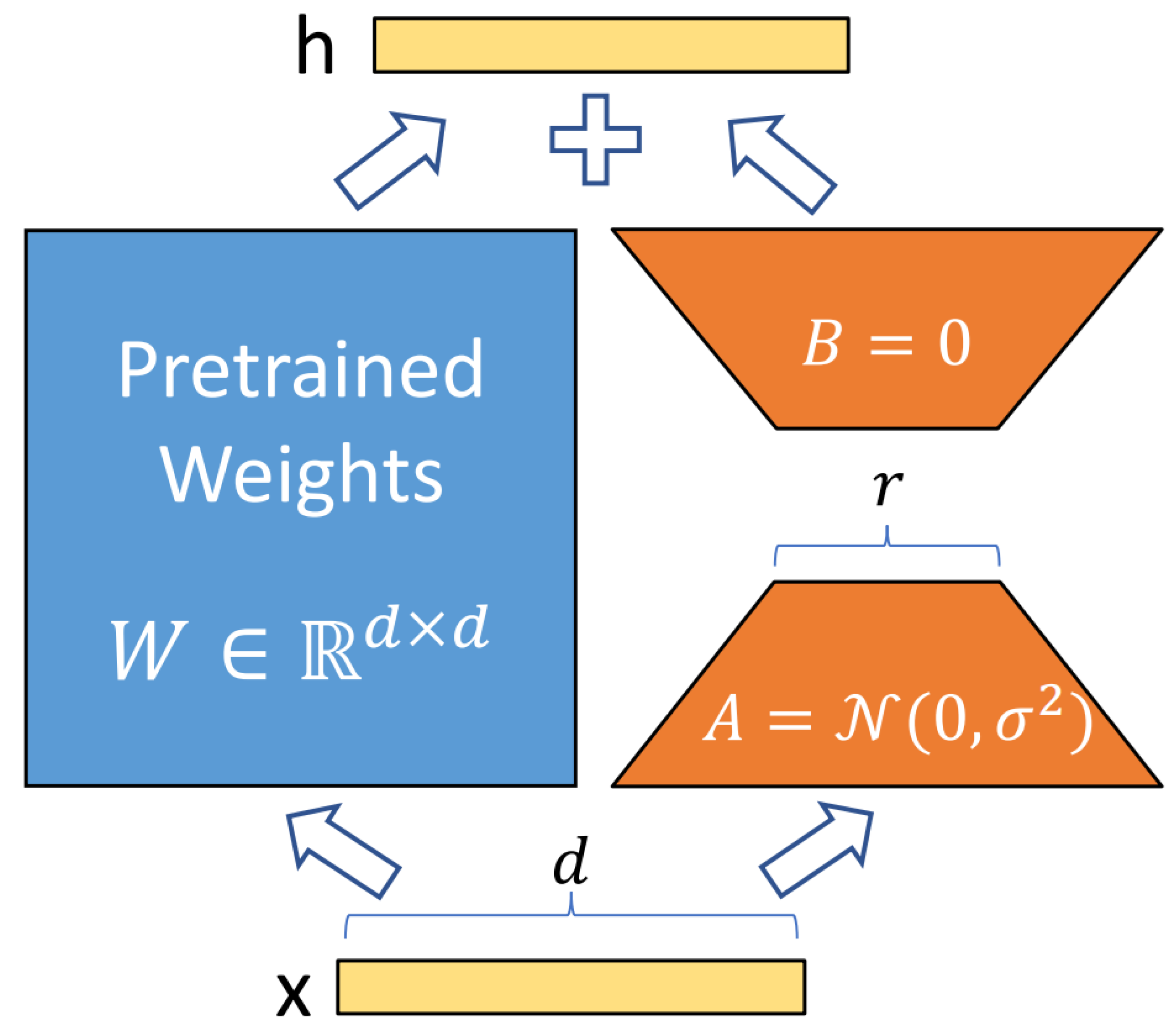

From a structural standpoint, low-rank updates can be interpreted as symmetry-preserving transformations on the parameter space: instead of arbitrarily modifying the full matrix and potentially disrupting pre-trained relational patterns, LoRA introduces controlled, smooth perturbations that maintain the dominant geometric structure of . This is especially desirable for legal judgment prediction, where the underlying label space exhibits partially symmetric co-occurrence patterns (e.g., child-related labels forming dense subgraphs) alongside asymmetric sparse connections for rare labels. A low-rank modification naturally emphasizes shared modes of variation corresponding to these symmetric clusters while avoiding overfitting to noisy or weak connections in the label graph.

Formally, given a pre-trained weight matrix

, LoRA constrains its update through low-rank decomposition:

where

and

represent the decomposition matrices, with rank

. During training,

remains frozen without gradient updates, while

A and

B are trainable. Both

and

multiply the same input, summing their outputs coordinate-wise. For the hidden layer transformation, the modified forward propagation becomes:

During initialization, LoRA sets

ensuring

at the training onset. To maintain numerical stability, LoRA scales the low-rank update by

during training, where

is a constant scaling factor. This mechanism ensures consistent update magnitudes across different rank choices and prevents divergence in early training stages.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, LoRA modules are integrated into Transformer layers, targeting attention projection matrices (

) and feed-forward projections (

). This design enables domain-specific adaptation while preserving pre-trained linguistic knowledge with minimal parameter overhead. Importantly, LoRA’s low-rank structure implicitly respects the symmetric and asymmetric patterns observed in the legal judgment label graph: shared structural modes are adjusted via low-rank bases, whereas sparsely connected or irregular judgment elements influence only small, well-conditioned perturbations. This structural alignment contributes to both the stability and efficiency of LawLLM-DS during domain adaptation.

2.4. Two-Stage Sequential Fine-Tuning Strategy

2.4.1. Stage 1: Legal Knowledge Pre-Tuning

The initial stage aims to adapt the pre-trained language model to the legal domain by exposing it to comprehensive judicial document structures and domain-specific terminology. During this phase, the model learns to recognize legal concepts, factual elements, and their linguistic patterns through multi-label classification of case fact descriptions. Let denote the LoRA parameters, denote the frozen pre-trained LLM parameters, denote the input fact description, and denote the target label set.

From a structural perspective, this stage primarily captures the dominant symmetric patterns embedded in the legal label co-occurrence graph. Frequently co-occurring judgment elements (e.g., child-care–related labels) form dense subgraphs with relatively balanced, quasi-symmetric connectivity. A higher learning rate in Stage 1 therefore encourages the model to rapidly internalize these global regularities while adjusting shared latent dimensions that govern the symmetrical structure of the label space.

The model predicts label probabilities

for each label

j. We employ binary cross-entropy loss:

where

and

is obtained via sigmoid activation. Only LoRA parameters

are updated while

remains frozen:

A higher learning rate facilitates rapid domain adaptation over globally consistent or symmetric structural regions of the label graph.

2.4.2. Stage 2: Judgment Relation Fine-Tuning

Stage 2 performs refined optimization using a distinct LoRA parameter set added to the frozen Stage 1 parameters. This stage focuses on modeling asymmetric or weakly connected regions of the legal label graph—such as rare divorce elements that appear sparsely and do not participate in symmetric co-occurrence clusters. These labels require fine-grained updates that must not destabilize the broad structural knowledge acquired in Stage 1.

The loss function is:

with

fixed to avoid catastrophic forgetting. Parameter updates are:

where the lower learning rate

enables stable and localized refinement of decision boundaries associated with structurally asymmetric or low-frequency label nodes.

2.4.3. Rationale for Sequential Fine-Tuning

The two-stage strategy addresses the tension between rapid domain adaptation and stable fine-grained optimization. Uniform learning rates often cause conflicting gradients because legal labels occupy a heterogeneous structural landscape: dense symmetric clusters respond well to aggressive updates, whereas sparse or asymmetric regions require conservative adjustments.

By decomposing adaptation into two sequential phases:

- Stage 1 efficiently captures global, symmetry-driven patterns in the label co-occurrence graph using a higher learning rate; - Stage 2 refines model behavior on structurally irregular or weakly connected labels with a lower learning rate.

This curriculum-inspired design yields greater training stability, mitigates catastrophic forgetting, and provides a structure-aware mechanism for adapting large language models to complex legal judgment prediction tasks. The result is a fine-tuning process that respects both the symmetric and asymmetric topology of the legal label graph while achieving substantial parameter efficiency through low-rank updates.

2.5. Implementation Details

We implement our framework using the Hugging Face Transformers library and the PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) library for LoRA integration. The base model employs Qwen 3-4B, a pre-trained large language model with approximately 4 billion parameters specifically designed for Chinese language understanding. To address GPU memory constraints while maintaining model capacity, we adopt 4-bit quantization using the BitsAndBytes library with NF4 (NormalFloat4) quantization type and double quantization enabled.

The LoRA configuration targets seven critical projection matrices within the Transformer architecture: query projection (), key projection (), value projection (), output projection (), gate projection (), up projection (), and down projection (). These matrices govern the internal geometric transformations of the model’s representation space, and modifying them via low-rank updates introduces structured adjustments that align well with the partially symmetric topology of the legal label graph. In particular, the chosen rank implicitly restricts updates to a small number of shared latent directions, enabling the model to capture symmetric co-occurrence patterns among frequent labels while avoiding excessive degrees of freedom that might overfit the sparse or asymmetric regions of the label space. A scaling factor is applied, and dropout with rate 0.05 is added to LoRA layers to improve generalization.

Training employs the AdamW optimizer with 8-bit paged optimization for memory efficiency. Stage 1 uses a learning rate with 50 warmup steps and weight decay of 0.01. Stage 2 reduces the learning rate to with 30 warmup steps while maintaining the same weight decay. These settings reflect the structural motivation of the two-stage framework: Stage 1 performs coarse adjustments aligned with globally symmetric regions of the label co-occurrence graph, whereas Stage 2 applies more conservative refinements suitable for asymmetric or weakly connected label nodes.

Both stages employ gradient accumulation with 2 steps, batch size of 4 per device, mixed-precision training (FP16), and early stopping with patience of 3 epochs based on macro F1-score on the validation set. Maximum training epochs are set to 3 for each stage, with the best checkpoint selected based on validation performance. Overall, this implementation achieves structure-aware parameter-efficient adaptation while keeping only 0.21% of model parameters trainable.

2.6. Datasets

Experiments are conducted on a Chinese legal judgment prediction dataset collected from China Judgements Online, the official online platform for Chinese judicial documents. The dataset focuses specifically on divorce-related civil cases, which were manually selected and annotated by legal experts. The dataset represents a significant subset of family law proceedings that require nuanced understanding of marital property classification, child custody arrangements, and grounds for divorce. In total, we collected 11,685 divorce-related judgments, and after rigorous preprocessing and expert validation, 5,096 cases that met the quality criteria were retained and annotated for downstream modeling.

Each data instance contains a fact description extracted from judicial opinions and a set of corresponding judgment labels manually annotated by domain experts. Unlike existing legal datasets, which primarily emphasize criminal charge prediction or article recommendation, this dataset addresses multi-label classification of civil judgment elements. The annotation process required lawyers to examine each case carefully and assign all legally relevant labels.

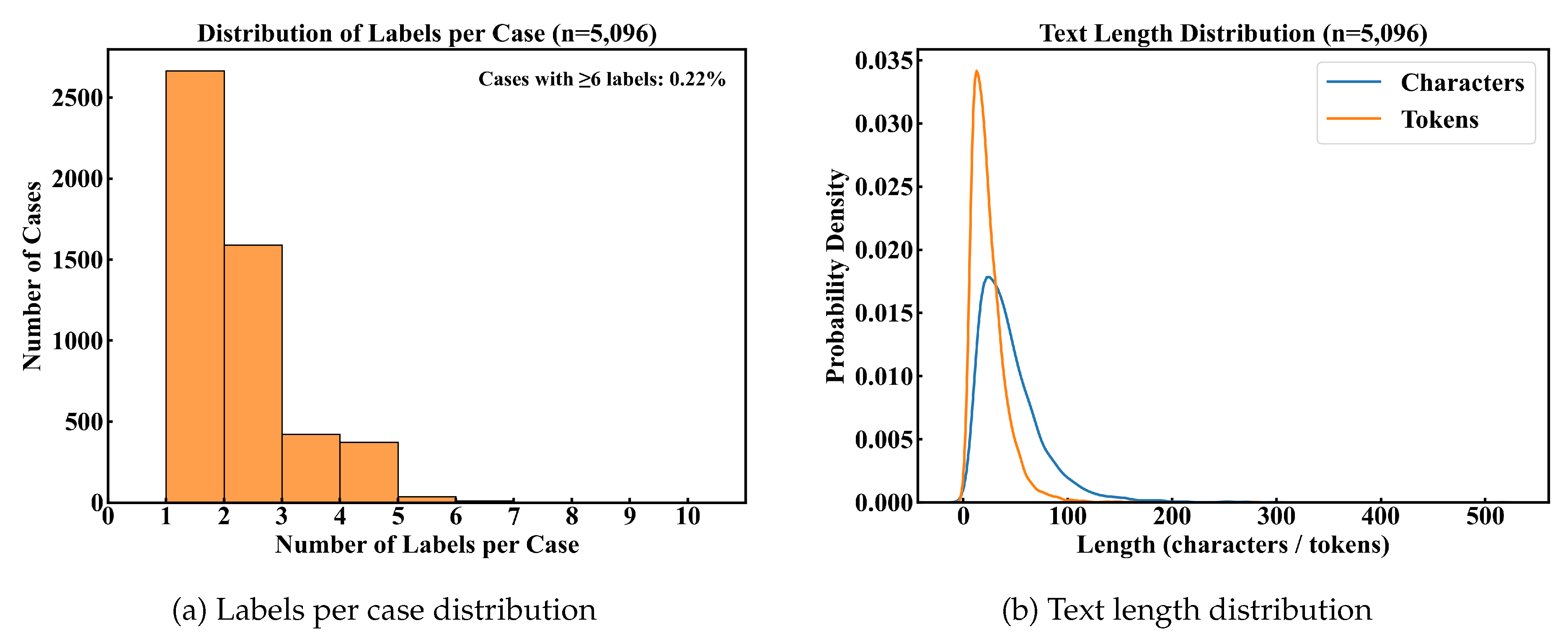

Figure 3 summarizes key statistical characteristics of the dataset, highlighting its notable sparsity: 93.1% of samples contain no more than three labels, and only 0.8% contain six or more. Fact descriptions are also short (median 38 characters), increasing the difficulty of extracting sufficient semantic cues.

Beyond basic descriptive statistics, the dataset exhibits a meaningful graph structure in its output space. The 20 annotated judgment labels (DV1–DV20) form a label co-occurrence graph in which edges encode how frequently two labels appear together in the same case. This graph contains several symmetric clusters with dense internal connectivity—for example, child-related labels (DV1, DV2, DV4, DV8, DV14, DV19) frequently co-occur and form a stable subgraph whose connections are approximately symmetric across pairs. In contrast, certain labels such as “Existence of illegitimate children” (DV14) or “Damages compensation” (DV17) appear infrequently and connect sparsely to the remainder of the graph, producing structurally asymmetric or weakly linked subregions. These mixed structural regimes resemble well-known patterns in graph connectivity and diagnosability analysis, where dense subgraphs behave predictably, and sparse nodes display irregular or unstable connectivity.

The dataset employs 20 judgment labels organized into several thematic groups:

Child-related labels: DV1 (Children after marriage), DV2 (Limited capacity child custody), DV4 (Child support payment), DV8 (Monthly child support), DV19 (Children living with non-custodial parent), DV14 (Existence of illegitimate children).

Property-related labels: DV3 (Marital community property), DV5 (Real estate division), DV11 (Pre-marital personal property), DV20 (Post-marital personal property), DV10 (Marital community debt).

Divorce grounds and procedures: DV9 (Approval of divorce), DV12 (Legal grounds for divorce), DV6 (Post-marital separation), DV7 (Second petition), DV18 (Emotional discord and two-year separation), DV13 (Failure to perform family obligations).

Additional legal elements: DV15 (Appropriate assistance), DV16 (Failure to perform agreement), DV17 (Damages compensation).

These labels collectively reflect the multifaceted nature of divorce proceedings. The high average number of positive labels per sample (3.2 out of 20) produces a nontrivial multi-label prediction scenario with structured label dependencies. Importantly, the co-occurrence graph reveals that some label groups align with strong symmetric relations, while other isolated labels contribute to asymmetric sparsity. This combination of structural regularity and irregularity motivates models that can preserve global coherence while performing fine-grained adjustments—an objective well served by the parameter-efficient, two-stage LoRA framework described in

Section 3.

The dataset is split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain label distribution consistency across splits. Because the output space exhibits heterogeneous connectivity—from dense symmetric clusters to sparse asymmetric nodes—macro-averaged metrics (Macro-F1, Macro-P, Macro-R) are emphasized to ensure fair evaluation across both frequent and rare label categories.

The dataset was constructed through a rigorous three-stage process: first, divorce-related civil case judgments were collected from the China Judgements Online platform. Second, legal experts manually screened and selected cases containing complete fact descriptions and clear judgment outcomes, filtering out incomplete or ambiguous cases. Third, each selected case was carefully annotated with relevant judgment labels from the 20-label taxonomy by trained legal professionals, with inter-annotator agreement verification to ensure annotation quality and consistency.

Beyond the annotation procedure itself, this process implicitly shapes the structural properties of the label co-occurrence graph. Because legal experts consistently identify the same clusters of elements in similar fact patterns, labels belonging to coherent legal subdomains (e.g., property division or child custody) tend to co-occur in stable, near-symmetric groupings, while rare or situational elements form sparse and asymmetric edges in the graph. This mixture of symmetric clusters and asymmetric connectivity is a defining characteristic of the dataset and later motivates a fine-tuning strategy that preserves global regularities while allowing targeted adjustments for structurally irregular labels.

Following standard practices in legal text analysis, the case documents are preprocessed by removing irrelevant metadata, normalizing punctuation, and standardizing legal terminology. Documents with empty fact descriptions or inconsistent labels are discarded to ensure data quality. The final dataset is split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test sets (15%) using a random stratified split, preserving the empirical distribution of each label. This stratification is particularly important because labels located in dense symmetric clusters are relatively stable across splits, whereas sparse or asymmetric labels risk disappearing without proper stratification.

The dataset exhibits several characteristics typical of legal multi-label classification: (1) strong class imbalance, where frequent labels such as “Approval of divorce’’ and “Marital community property’’ dominate; (2) the presence of rare, weakly connected labels such as “Existence of illegitimate children’’ and “Damages compensation’’; and (3) substantial label co-occurrence, with most cases involving 3–5 labels simultaneously. These distributional properties align with the structural interpretation of the label graph: dense regions correspond to consistently co-occurring legal outcomes, while sparse regions capture exceptional or case-specific judicial elements. Together, these properties present unique challenges for model training and evaluation, especially for prediction frameworks that must balance symmetric regularities with asymmetric sparsity in the output space.

2.7. Experimental Setup

This section presents the baseline methods, evaluation metrics, and implementation details for the experiments. In designing the evaluation pipeline, particular attention is given to the structural properties of the label co-occurrence graph identified in

Section 4, where dense symmetric clusters coexist with sparse asymmetric nodes. The selected baselines and metrics allow us to evaluate how effectively each method handles both regions of the label space.

2.7.1. Comparison Methods

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage sequential fine-tuning approach, comparison is made against several baseline configurations:

Traditional ML Baselines: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting classifiers using TF-IDF features, representing classical feature-based approaches for legal text classification [

9,

10]. These models do not explicitly account for label co-occurrence structure and therefore provide a useful lower bound for tasks involving asymmetric and sparse labels.

Neural Baselines: TextCNN and BERT-base Chinese fine-tuned on the legal judgment task, representing standard neural and pre-trained language model baselines without parameter-efficient adaptation [

11]. These models learn continuous representations but still rely on full-parameter updates that may overfit to rare or weakly connected labels.

Legal-Specific Models: MPBFN, LADAN, Mulan, and CBA, domain-specific architectures designed for legal judgment prediction tasks [

12,

39,

40,

41]. These models often incorporate hierarchical or attention-based mechanisms tailored for the structural dependencies observed in legal reasoning, making them natural baselines for evaluating how well the proposed approach captures symmetric and asymmetric relations across the label graph.

Collectively, these baselines cover a spectrum from feature-based shallow models to domain-specific neural architectures, enabling comparison across methods with differing abilities to exploit or ignore label-space structure.

2.7.2. Evaluation Metrics

Multi-label classification requires evaluation metrics that account for multiple labels per instance, label imbalance, and the structured dependencies among labels. Because the label co-occurrence graph contains symmetric clusters (frequent labels forming dense neighborhoods) and asymmetric sparse labels (rare nodes with weak connectivity), macro-averaged metrics are especially important: they treat each label equally and therefore prevent frequent symmetric labels from dominating performance.

Five widely used metrics are adopted:

Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1-Score: computed independently for each label and then averaged across labels. These metrics evaluate performance uniformly across the entire label graph, regardless of the node degree or connectivity of each label.

Hamming Loss: measures the fraction of incorrectly predicted labels. Because rare labels form structurally asymmetric nodes in the label graph, Hamming Loss is sensitive to false positives or false negatives in these regions and thus complements macro-averaged metrics.

Accuracy: evaluates whether the entire set of predicted labels for each sample matches the ground truth. This metric becomes stringent under the severe sparsity of the dataset, where most samples contain few labels.

To ensure consistency across models, we apply a sigmoid activation followed by a fixed threshold of 0.5 for every label. Because label sparsity and asymmetric graph structure strongly affect probability calibration, differences in Hamming Loss and Macro-F1 frequently reflect how well a model captures both symmetric clusters and isolated asymmetric labels.

Formally, given

L labels and

N samples, let

,

, and

denote the true positives, false positives, and false negatives for label

ℓ, while

and

represent the predicted and ground-truth indicators for sample

i:

These definitions enable consistent evaluation across models and provide complementary perspectives on how well each method handles both dense symmetric and sparse asymmetric regions of the label graph.

2.7.3. Implementation Details

The two-stage LoRA fine-tuning framework is implemented using Qwen 3-4B as the base language model, a state-of-the-art Chinese pre-trained model with approximately 4 billion parameters. The architecture adopts a 32-layer Transformer encoder with 32 attention heads and hidden dimension of 2048. To enable efficient training on resource-constrained hardware, 4-bit quantization is applied using the BitsAndBytes library with NF4 quantization and double quantization enabled.

Following the parameter-efficient strategy described in

Section 3, LoRA is inserted into seven projection matrices within each Transformer layer: query (

), key (

), value (

), output (

), and the feed-forward projections (

,

,

). These matrices govern the linear subspace transformations that define the geometry of the model’s latent space. Introducing low-rank adaptations into these locations allows the model to adjust shared representational directions that correspond to the symmetric label co-occurrence clusters identified in the dataset, while preventing excessive deformation that would destabilize predictions for sparse or structurally asymmetric labels.

We set LoRA rank to with scaling factor , yielding approximately 8.4 million trainable parameters—only 0.21% of the full model. This small-rank configuration restricts updates to a compact subspace that naturally aligns with global symmetric patterns in the label graph while avoiding high-dimensional noise in its asymmetric regions. Dropout with rate 0.05 is applied to LoRA layers during both stages to prevent overfitting.

Both Stage 1 and Stage 2 employ the AdamW optimizer with 8-bit paged optimization for memory efficiency. Stage 1 uses learning rate to encourage broader adjustments aligned with symmetric label clusters, whereas Stage 2 applies a reduced learning rate to refine predictions on asymmetric or sparsely connected labels. Both stages employ warmup steps (50 and 30), weight decay of 0.01, gradient accumulation with 2 steps, and batch size of 4 per device. Mixed-precision training (FP16) is enabled for computational efficiency. Early stopping with patience of 3 epochs based on macro F1-score is applied, with a maximum of 3 training epochs per stage. Training converges within 2–3 epochs per stage on an NVIDIA RTX 5090 GPU.

Table 1 summarizes the hyperparameter configuration.

2.7.4. Performance Assessment

Table 2 presents the performance comparison of LawLLM-DS (Law Large Language Model with Dual-Stage training) on the divorce judgment prediction task. The results demonstrate several key findings regarding the effectiveness of sequential fine-tuning strategies for legal domain adaptation. Importantly, the improvements align with the structural properties of the label co-occurrence graph identified earlier: LawLLM-DS excels not only on frequent labels forming dense symmetric clusters but also on rare, weakly connected labels that exhibit asymmetric sparsity—an area where many baselines struggle.

LawLLM-DS achieves the best performance among parameter-efficient approaches. Stage 2 attains a macro F1-score of 0.8893 and accuracy of 0.8786, outperforming all lightweight baselines including BERT and traditional neural architectures. The improvements are substantial: +7.56 percentage points over BERT in macro F1-score and +8.74 percentage points in accuracy. Because the dataset is highly sparse (average 3.2 positive labels per sample), weak models can reduce Hamming Loss simply by predicting mostly negatives. Under the unified 0.5 threshold, LawLLM-DS still reduces Hamming Loss to 0.0155, confirming that gains arise from correctly identifying rare positive labels rather than exploiting sparsity.

From a structural standpoint, the most significant improvements appear on labels occupying sparse or asymmetric regions of the label co-occurrence graph—precisely where single-stage LoRA or full fine-tuning approaches exhibit instability. Stage 2 selectively refines decision boundaries associated with isolated label nodes while preserving global consistency learned from symmetric clusters. This structural alignment explains the large F1 gains and the 7.2% reduction in Hamming Loss between Stage 1 and Stage 2.

Traditional machine learning methods perform poorly due to reliance on TF-IDF features, which cannot encode higher-order co-occurrence or graph-structured relationships among legal labels. Deep neural architectures such as TextCNN, MPBFN, LADAN, Mulan, and CBA perform better, but they require full-parameter training and are still unable to model the heterogeneous topology of the label graph, limiting their ability to capture asymmetric dependencies.

BERT-base-Chinese offers strong transfer-learning performance, but its full fine-tuning strategy updates all parameters, making it resource-intensive. Moreover, full-parameter updates tend to distort pre-trained subspaces in ways that can overfit symmetric clusters while degrading performance on sparse asymmetric labels. This effect is visible in its higher Hamming Loss (0.0178) compared to LawLLM-DS.

Among compact LLMs with LoRA, DeepSeek-1.5B and GPT-2 lag behind, either due to insufficient capacity or architectural limitations in modeling bidirectional dependencies critical for legal reasoning.

A critical advantage of LawLLM-DS lies in its low-rank, symmetry-preserving update mechanism: with only 0.21% trainable parameters, the model modifies shared latent directions that correspond to the main symmetric clusters in the label graph while leaving asymmetric subspaces stable until Stage 2 refinement. This leads to a highly favorable trade-off between performance and parameter efficiency.

The trajectory from Stage 1 to Stage 2 illustrates the curriculum-inspired learning dynamic: Stage 1 identifies broad structural regularities across symmetric co-occurrence clusters, while Stage 2 improves prediction on structurally irregular or infrequent labels. The improvements in macro precision (from 0.8821 to 0.9066) and accuracy (from 0.8134 to 0.8786), combined with reduced Hamming Loss (0.0167 to 0.0155), provide empirical evidence that sequential fine-tuning with differentiated learning rates enables a structure-aware optimization path that respects both global symmetry and local asymmetry in the output space.

Finally, the performance gap between Single-Stage LoRA (0.8547 F1) and the proposed two-stage approach (0.8893 F1) highlights that the gains come not from increased parameter count but from a training strategy aligned with the structural geometry of the label graph. The 18% reduction in Hamming Loss (0.0189 → 0.0155) further demonstrates that LawLLM-DS achieves significantly more accurate label-wise predictions—especially on sparse asymmetric nodes.

2.7.5. Ablation Study

To thoroughly understand the contribution of each component in the framework, comprehensive ablation studies are conducted examining the impact of learning rate schedules, LoRA rank configurations, and training strategies. These studies are particularly important given the heterogeneous structural topology of the label co-occurrence graph introduced in

Section 4, where dense symmetric clusters coexist with sparse, asymmetric labels. An effective model must adapt simultaneously to both regimes, and the ablations reveal how each design choice contributes to this structural alignment.

Table 3 presents the performance of different learning rate configurations across the two stages. The results demonstrate that the chosen configuration (

,

) achieves optimal performance. Using a uniform learning rate (

) degrades macro F1-score to 0.8634, similar to single-stage training. This occurs because a uniform learning rate fails to differentiate between (1) large-scale updates needed to capture symmetric label clusters during Stage 1 and (2) small, precise adjustments required for asymmetric or low-degree labels in Stage 2. Higher learning rates in Stage 2 (

) lead to instability and degraded performance (F1: 0.8578), as overshooting disrupts the previously learned symmetry-preserving structure. Conversely, excessively low learning rates in Stage 1 (

) result in insufficient domain adaptation (F1: 0.8512). These findings validate that differentiated learning rates are crucial for balancing rapid exploration in symmetric subspaces and stable refinement in asymmetric subspaces.

The effect of LoRA rank

r on model performance and parameter efficiency is investigated in

Table 4. Rank

r determines the dimensionality of the update subspace and thus corresponds to the number of structural modes through which the model can adjust its behavior. Lower ranks (

) offer insufficient representational capacity to model the symmetric co-occurrence clusters, resulting in degraded performance (F1: 0.8612). Higher ranks (

or

) increase expressiveness and yield marginal gains (F1: 0.8901 and 0.8915, respectively), but the improvement is small relative to the increase in trainable parameters. The optimal rank of

achieves 99.8% of the performance of

with only 25% of the parameters, indicating that the intrinsic dimensionality of the label graph—the number of dominant symmetric subspaces—is relatively low. This provides a structural justification for why low-rank updates are well suited for this task.

We additionally analyze the contribution of different projection matrices by selectively applying LoRA to subsets of modules.

Table 5 shows that the full configuration targeting all seven projections achieves the best performance (F1: 0.8893). Notably, applying LoRA only to attention modules (

) yields 0.8734 F1-score (98.2% of full performance). This confirms that attention projections are most critical for modeling the structural dependencies across the label graph, as they directly influence how the model attends to textual cues associated with symmetric clusters and asymmetric rare labels. Feed-forward projections alone achieve 0.8598 F1, showing that nonlinear transformation layers also contribute meaningfully, particularly to fine-grained adjustments of asymmetric labels.

Minimalist configurations such as Query & Value only achieve 0.8467, demonstrating a 4.8% performance drop. These results suggest that attention modules capture global structural relations (including symmetric co-occurrence among labels), while FFN modules contribute to localized refinements analogous to adjusting asymmetric, low-frequency labels. The full combination of attention and feed-forward modules is therefore necessary to achieve robust structural alignment with the heterogeneous topology of the label co-occurrence graph.

Table 5 evaluates the contribution of different projection modules by selectively applying LoRA to subsets of the Transformer architecture. The results reveal a clear structural interpretation when viewed through the lens of the label co-occurrence graph introduced earlier. This graph contains (1) dense and approximately symmetric clusters—such as child-related and property-related labels—and (2) sparse, highly asymmetric nodes corresponding to low-frequency legal factors. An effective fine-tuning mechanism must therefore capture both global structural regularities and local irregularities.

The attention-only configuration achieves 0.8734 Macro-F1 (98.2% of full performance), confirming that the attention projections are principally responsible for capturing global dependencies across the label graph. In graph-structural terms, attention governs the model’s ability to exploit symmetric neighborhoods—labels that frequently co-occur across similar factual patterns. In contrast, the FFN-only configuration yields 0.8598 Macro-F1, which demonstrates that feed-forward layers primarily encode localized, non-symmetric refinements related to rare or weakly connected labels.

Minimalist configurations such as Query & Value only result in a significant performance drop (F1: 0.8467), indicating that both global relation modeling (via full attention blocks) and nonlinear local transformations (via FFN) are necessary. The superiority of the full seven-module configuration thus reflects the heterogeneous topology of the underlying label graph, where the co-existence of symmetric clusters and asymmetric outliers requires coordinated updates across multiple projection pathways.

Table 6 compares the proposed sequential fine-tuning strategy with alternative training paradigms. The two-stage approach achieves the highest performance (F1: 0.8893), demonstrating that separating broad domain adaptation from fine-grained refinement is structurally advantageous. This observation aligns with the decomposition of the label graph into high-degree symmetric components (learned in Stage 1) and low-degree asymmetric components (refined in Stage 2).

The degradation of the single-stage baseline (F1: 0.8547) indicates that blending coarse-grained and fine-grained objectives forces the model to follow conflicting gradient signals, particularly in asymmetrically distributed labels. Joint optimization of both LoRA sets alleviates this issue slightly (F1: 0.8723) but still underperforms due to interference between high-magnitude exploratory updates and low-magnitude corrective updates. Alternating stage training (F1: 0.8801) improves stability but remains inferior to the sequential freeze–refine paradigm.

Critically, Stage-2-only training performs the worst (F1: 0.8412), confirming that refinement without an initial symmetry-aware domain adaptation cannot faithfully model the structural geometry of the label graph. The two-stage method therefore provides not only empirical gains but also a principled alignment between optimization dynamics and the latent symmetry structure of the task.

2.7.6. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

To further evaluate the robustness and structural generalization properties of the proposed framework, a systematic hyperparameter sensitivity analysis is conducted across three critical dimensions: batch size, learning rate, and sequence length.

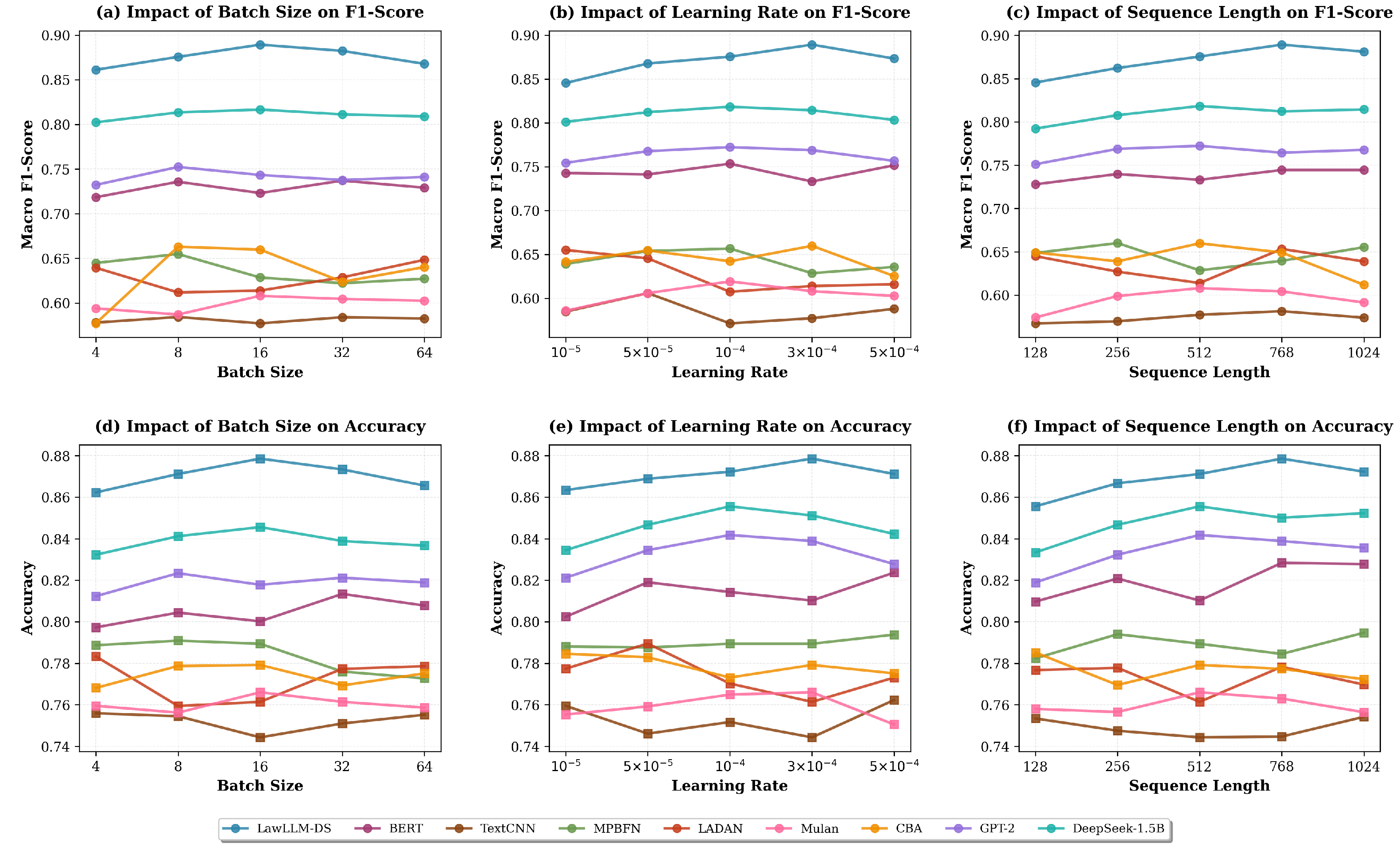

Figure 4 visualizes the performance variations of all deep learning models under different configurations. These hyperparameters are chosen because they interact differently with the latent topology of the label co-occurrence graph: (1) batch size influences gradient noise and therefore affects the learning of symmetric vs. asymmetric label clusters; (2) learning rate modulates the stability of updates on densely vs. sparsely connected regions of the graph; and (3) sequence length determines the model’s capacity to encode global vs. local legal cues embedded in short factual descriptions.

Across all settings, LawLLM-DS consistently outperforms baseline methods and maintains notably stable performance. This stability reflects its two-stage learning mechanism, which mirrors the structural decomposition of the task. In Stage 1, higher learning rates facilitate rapid alignment with the symmetric core of the label graph—clusters such as child-related or property-related labels that co-occur frequently and form dense subgraphs. In Stage 2, lower learning rates refine predictions for asymmetric, low-degree labels whose distributions present greater variability. As a result, LawLLM-DS remains robust under both aggressive and conservative optimization regimes.

Batch size analysis reveals that LawLLM-DS achieves near-optimal performance at moderate batch sizes, where gradient variance remains sufficient to explore asymmetric label relationships without destabilizing symmetric global patterns. Other models exhibit sharper performance drops, suggesting weaker separation between global and local structural learning. Similarly, learning rate sensitivity demonstrates that while most models degrade rapidly under higher learning rates, LawLLM-DS preserves competitive performance due to Stage 1’s structurally aligned adaptation schedule.

Sequence length experiments further show that LawLLM-DS benefits from extended input lengths because the additional context strengthens its ability to encode global dependencies in factual narratives—dependencies that strongly correlate with symmetric patterns in the label graph. Even when sequence lengths are shortened, performance remains relatively stable, indicating that the model has internalized structurally meaningful representations rather than superficial textual heuristics.

Overall, the consistently superior performance of LawLLM-DS across the entire hyperparameter range highlights the generalizability and structural robustness of the proposed framework. By aligning the optimization dynamics with the graph-theoretic structure of the label space, the two-stage LoRA design exhibits resilience to hyperparameter perturbations, making it well-suited for real-world legal judgment prediction scenarios where optimal hyperparameter selection may not always be feasible.

3. Conclusion

This paper presented LawLLM-DS, a two-stage sequential fine-tuning framework based on Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) designed to address the computational and optimization challenges of adapting large language models to specialized legal judgment prediction tasks. Beyond improving efficiency, the framework implicitly exploits structural regularities in the underlying multi-label space—where certain judgment categories form dense, quasi-symmetric co-occurrence clusters while others exhibit sparse, asymmetric patterns. Stage 1, operating with a higher learning rate, rapidly aligns the model with these globally symmetric structures by acquiring broad legal domain knowledge; Stage 2, with a more conservative learning rate, refines decision boundaries on structurally asymmetric or low-frequency labels without disturbing the representations stabilized in Stage 1.

Extensive experiments on a 20-label Chinese divorce judgment dataset demonstrate that LawLLM-DS achieves substantial performance gains over single-stage fine-tuning and traditional neural architectures, despite updating only 0.21% of parameters. The results highlight three key conclusions: (1) curriculum-inspired sequential fine-tuning yields more stable and discriminative representations than uniform optimization schedules, (2) decomposing domain adaptation into symmetric global learning (Stage 1) and asymmetric local refinement (Stage 2) mitigates conflicting gradient dynamics and enhances convergence robustness, and (3) LoRA-based parameter-efficient methods, when coupled with stage-wise learning strategies, can match or surpass full fine-tuning while dramatically reducing computational costs, making them suitable for real-world legal AI applications with constrained hardware.

LawLLM-DS provides a principled and reproducible pathway for deploying large language models in the legal domain, especially in tasks characterized by structured label interactions and limited annotated data. Future research may explore adaptive or self-paced stage transitions, integrate graph-based priors that explicitly encode label symmetries and asymmetries, extend the framework to more complex legal tasks such as contract analysis or court-view generation, and investigate multilingual or cross-jurisdictional judgment prediction settings where structural patterns may vary across legal systems.