Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Carbon-Based Physisorbing Materials

2.1. Activated Carbons

2.2. Nanostructured Carbon Materials

2.3. More Recent Investigations

3. Implementation of Means to Better Assess Performances

3.1. Numerical-Experiment Improvements

3.2. Experimental Improvements

4. Comparative Evaluation

4.1. U.S. DoE’s Technical-System Targets

4.2. Other Comparisons

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winebrake, J.J. Hype or Holy Grail? The Future of Hydrogen in Transportation. Strateg. Plan Energy Environ. 2002, 22, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampai, M.M.; Mtshali, C.B.; Seroka, N.S.; Khotseng, L. Hydrogen production, storage, and transportation: recent advances. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 6699–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jia, C.; Bai, F.; Wang, W.; An, S.; Zhao, K.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, H. A comprehensive review of the promising clean energy carrier: Hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and utilization (HPTSU) technologies. Fuel 2024, 355, 129455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, H.; Hanlon, J.M.; Hughes, R.W.; Godula-Jopek, A.; Mandal, T.K.; Gregory, D.H. Emerging concepts in solid-state hydrogen storage: the role of nanomaterials design. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5951–5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veziroglu, T.N.; Basar, O. Dynamics of a universal hydrogen fuel system. In Proceedings of the Hydrogen Economy Miami Energy Conference, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 18-20 March 1974; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 1309–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Goltsov, V.A.; Veziroglu, T.N. From hydrogen economy to hydrogen civilization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2001, 26, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretz, J.; Drolet, B.; Kluyskens, D.; Sandmann, F.; Ullman, O. Status of the Hydro-Hydrogen Pilot Project (EQHHPP). Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 1994, 19, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahbout, A.; Kluyskens, D.; Wurster, R. Status Report on the Demonstration Phases of the Euro-Québec Hydro-Hydrogen Pilot Project. In Proceedings of the 12th World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 21-26 June 1998; pp. 495–512. [Google Scholar]

- Lamari Darkrim, F.; Malbrunot, P.; Tartaglia, G.P. Review of hydrogen storage by adsorption in carbon nanotubes. Int. J. hydrogen Energ. 2002, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A.C.; Heben, M.J. Hydrogen storage using carbon adsorbents: past, present and future. Appl. Phys. A 2001, 72, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.; Park, C.; Baker, R.T.K; Rodriguez, N.M. Hydrogen Storage in Graphite Nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4253–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, M.; Cong, H.T.; Cheng, H.M.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Hydrogen Storage in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes at Room Temperature. Science 1999, 286, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A.C.; Jones, K.M.; Bekkedahl, T.A.; Kiang, C.H.; Bethune, D.S.; Heben, M.J. Storage of hydrogen in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nature 1997, 386, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach, L.; Züttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature 2001, 414, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpetis, C.; Peshka, W. A study on hydrogen storage by use of cryoadsorbents. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 1980, 5, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.K.; Noh, J.S.; Schwarz, J.A.; Davini, P. Effect of surface acidity of activated carbon on hydrogen storage. Carbon 1987, 25, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, R.; Bénard, P. Performance study of hydrogen adsorption storage systems. In Proceedings of the 12th World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 21-26 June 1998; pp. 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Darkrim, F.; Vermesse, J.; Malbrunot, P.; Levesque, D. Monte Carlo simulations of nitrogen and hydrogen physisorption at high pressures and room temperature. Comparison with experiments. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 4020–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkrim, F.; Levesque, D. Monte Carlo simulations of hydrogen adsorption in single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 4981–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ahn, C.C.; Witham, C.; Fultz, B.; Liu, J.; Rinzler, A.G.; Colbert, D.; Smith, K.A.; Smalley, R.E. Hydrogen adsorption and cohesive energy of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 74, 2307–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, A.; Harting, A. Thermodynamic Description of Excess Isotherms in High-Pressure Adsorption of Methane, Argon and Nitrogen. Adsorption 2002, 8, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbrunot, P.; Vidal, D.; Vermesse, J.; Chahine, R.; Bose, T.K. Adsorbent Helium Density Measurement and Its Effect on Adsorption Isotherms at High Pressure. Langmuir 1997, 13, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B.; Darkrim Lamari, F. High pressure cryo-storage of hydrogen by adsorption at 77K and up to 50MPa. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2009, 34, 3058–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, J.; Wong-Foy, A.G.; Cafarella, M.J.; Siegel, D.J. Theoretical limits of hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks: Opportunities and trade-offs. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 3373–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón, Y.J.; Fairen-Jimenez, D.; Wilmer, C.E.; Snurr, R.Q. High-throughput screening of porous crystalline materials for hydrogen storage capacity near room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 5383–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Seth, S.; Purewal, J.; Wong-Foy, A.G.; Veenstra, M.; Matzger, A.J.; Siegel, D.J. Exceptional hydrogen storage achieved by screening nearly half a million metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.A.; Al-Qodah, Z.; Ngah, C.W.Z. Agricultural bio-waste materials as potential sustainable precursors used for activated carbon production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 46, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, K.A.G.; Noh, J.S.; Schwarz, J.A. Hydrogen Storage on Superactivated Carbon at Refrigeration temperatures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 1989, 14, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamari, M.; Aoufi, A.; Malbrunot, P.; Pentchev, I. Storage of Hydrogen by Adsorption at Room Temperature: Realistic Way of Storage. In Proceedings of the 8th Canadian Hydrogen Workshop, Toronto, Canada, 28-30 May 1997; pp. 352–366. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.M.; Takara, S. Catalytically Enhanced Systems for Hydrogen Storage. In Proceedings of the 2000 DOE Hydrogen Program Review, San Ramon, CA, USA, 9-11 May 2000; pp. 588–593. [Google Scholar]

- Delahaye, A.; Aoufi, A.; Gicquel, A.; Pentchev, I. Improvement of hydrogen storage by adsorption using 2-D modeling of heat effects. AIChE J. 2002, 48, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J.P.B.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Saatdjian, E.; Tondeur, D. Dynamics of natural gas adsorption storage systems employing activated carbon. Carbon 1997, 35, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamari, M.; Aoufi, A.; Malbrunot, P. Thermal effects in dynamic Storage of Hydrogen by Adsorption. AIChE J. 2000, 46, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpetis, C.; Peschka, W. On the storage of hydrogen by use of cryoadsorbents. In Proceedings of the 1st World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 1-3 March 1976; pp. 9C:45–9C:54. [Google Scholar]

- Chahine, R.; Bose, T.K. Characterization and optimization of adsorbents for hydrogen storage. In Proceedings of the 11th World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Stuttgart, Germany, 23-28 June 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Balderas-Xicohténcatl, R.; Schlichtenmayer, M.; Hirscher, M. Volumetric Hydrogen Storage Capacity in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbitt, N.S.; Snurr, R.Q. Molecular modelling and machine learning for high-throughput screening of metal-organic frameworks for hydrogen storage. Mol. Simul. 2019, 45, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Vidal, P.; Sdanghi, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. High hydrogen release by cryo-adsorption and compression on porous materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2022, 47, 8892–8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.A. Activated Carbon-Based Hydrogen Storage System. In Proceedings of the 1993 DOE/NREL Hydrogen Program Review, Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 4-6 May 1993; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah, K. Hydrogen Storage Technology. Presentation at the Workshop on Hydrogen Storage Technologies, Golden, CO, USA, 11 November 1992; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Heben, M.J. Carbon Nanotubules for Hydrogen Storage. In Proceedings of the 1993 DOE/NREL Hydrogen Program Review, Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 4-6 May 1993; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Gao, Q.; Hu, J. High hydrogen storage capacity of porous carbons prepared by using activated carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7016–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-K.; Park, S.-J. Preparation and characterization of sucrose-based microporous carbons for increasing hydrogen storage. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 28, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.-J.; Park, S.-J. Synthesis of activated carbon derived from rice husks for improving hydrogen storage capacity. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 31, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, N.; Ouederni, A. Optimization of biomass-based carbon materials for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2016, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethia, G.; Sayari, A. Activated carbon with optimum pore size distribution for hydrogen storage. Carbon 2016, 99, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Fan, M. Synthesis of bamboo-based activated carbons with super-high specific surface area for hydrogen storage. BioRes. 2017, 12, 1246–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomkin, A.; Pribylov, A.; Men’shchikov, I.; Shkolin, A.; Aksyutin, O.; Ishkov, A.; Romanov, K.; Khozina, E. Adsorption-Based Hydrogen Storage in Activated Carbons and Model Carbon Structures. Reactions 2021, 2, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Casa-Lillo, M.A.; Lamari Darkrim, F.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Linares-Solano, A. Hydrogen Storage in Activated Carbons and Activated Carbon Fibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 10930–10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Mokaya, R.; Fuertes, A.B. Ultrahigh surface area polypyrrole-based carbons with superior performance for hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2930–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, C. Sc-Decorated Porous Graphene for High-Capacity Hydrogen Storage: First-Principles Calculations. Materials 2017, 10, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Hassan, M.; Lee, H.J.; Jhung, S.H. Preparation, characterization, and applications in adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, V.; Szczurek, A.; Zlotea, C.; Marêché, J.F.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Albiniak, A.; Latroche, M.; Furdin, G.; Celzard, A. Experimental evidence of an upper limit for hydrogen storage at 77 K on activated carbons. Carbon 2010, 48, 1902–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, L.S.; Balahmar, N.; Mokaya, R. Oxygen-rich microporous carbons with exceptional hydrogen storage capacity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, H.; Kyotani, T. Zeolite-templated carbons – three-dimensional microporous graphene frameworks. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 5648–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.E.; Garman, K.; Stadie, N.P. Atomistic Structures of Zeolite-Templated Carbon. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 2742–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masika, E.; Mokaya, R. Exceptional gravimetric and volumetric hydrogen storage for densified zeolite templated carbons with high mechanical stability. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, T.; Bichara, C.; Gubbins, K.E.; Pellenq, R.J.M. Hydrogen storage enhanced in Li-doped carbon replica of zeolites: A possible route to achieve fuel cell demand. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 174717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, R.; Bose, T.K. Low-pressure adsorption storage of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 1994, 19, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsutaka, H.; Kashifuku, A.; Orii, T.; Miyajima, D.; Uchiyama, N.; Wada, S.; Nishihara, H. Densification of cellulose acetate-derived porous carbon for enhanced volumetric hydrogen adsorption performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 22392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordá-Beneyto, M.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Suárez-García, F.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Linares-Solano, A. Advanced activated carbon monoliths and activated carbons for hydrogen storage. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2008, 112, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilev, Ch.; Darkrim Lamari, F.; Ljutzkanov, L.; Simeonov, E.; Pentchev, I. Hydrogen storage systems using modified sorbents for application in automobile manufacturing. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2012, 37, 10172–10181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fierro, V.; Zlotea, C.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Chevalier-César, C.; Latroche, M.; Celzard, A. Activated carbons doped with Pd nanoparticles for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2012, 37, 5072–5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissov, N.; Aidarbekov, N.; Kuspanov, Z.; Askaruly, K.; Tsurtsumia, O.; Kuterbekov, K.; Zeinulla, Z.; Bekmyrza, K.; Kabyshev, A.; Kubenova, M.; et al. Effect of Metal Modification of Activated Carbon on the Hydrogen Adsorption Capacity. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contescu, C.I.; Adhikari, S.P.; Gallego, N.C.; Evans, N.D.; Biss, B.E. Activated Carbons Derived from High-Temperature Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass. C 2018, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlandson, J.L.; Edler, K.J.; Tian, M.; Ting, V.P. Toward process-resilient lignin-derived activated carbons for hydrogen storage applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2186–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Alcañiz-Monge, J.; de la Casa-Lillo, M.A.; Linares-Solano, A. CO₂ as an Adsorptive to Characterize Carbon Molecular Sieves and Activated Carbons. Langmuir 1998, 14, 4589–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, M.; Lamp, P.; de la Casa-Lillo, M.A. Physisorption of Hydrogen on Microporous Carbon and Carbon Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 10894–10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirscher, M.; Becher, M.; Haluska, M.; Dettlaff-Weglikowska, U.; Quintel, A.; Duesberg, G.S.; Choi, Y.-M.; Downes, P.; Hulman, M.; Roth, S.; Stepanek, I.; Bernier, P. Hydrogen storage in sonicated carbon materials. Appl. Phys. A 2001, 72, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Tanaka, H.; Hołyst, R.; Kaneko, K.; Ohmori, T.; Miyamoto, J. Storage of Hydrogen at 303 K in Graphite Slitlike Pores from Grand Canonical Monte Carlo Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 17174–17183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströbel, R.; Garche, J.; Moseley, P.T.; Jörissen, L.; Wolf, G. Hydrogen storage by carbon materials. J. Power Sources 2006, 159, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkinides, E.S.; Konstantakou, M.; Georgiadis, M.C.; Steriotis, Th.A.; Stubos, A.K. Multiscale Modeling and Optimization of H2 Storage Using Nanoporous Adsorbents. AIChE J. 2006, 52, 2964–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Storage of hydrogen by physisorption on carbon and nanostructured materials. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, N.C.; He, L.; Saha, D.; Contescu, C.; Melnichenko, Y.B. Hydrogen confinement in carbon nanopores: Extreme densification at ambient temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13794–13797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Lozar, J.P.; Kunowsky, M.; Suarez-Garcia, F.; Carruthers, J.D.; Linares-Solano, A. Activated carbon monoliths for gas storage at room temperature. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9833–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, J.; Cossement, D.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Finite element model for charge and discharge cycle of activated carbon hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2012, 37, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Lozar, J.P.; Kunowsky, M.; Carruthers, J.D.; Linares-Solano, A. Gas storage scale-up at room temperature on high density carbon materials. Carbon 2014, 76, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunowsky, M.; Marco-Lózar, J.P.; Linares-Solano, A. Material Demands for Storage Technologies in a Hydrogen Economy. J. Renew. Energy 2013, 1, 878329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, M.D.; Hulvey, Z.; Gennett, T.; Ahmed, A.; Autrey, T.; Camp, J.; Cho, E.S.; Furukawa, H.; Haranczy, M.; Head-Gordon, M.; et al. An assessment of strategies for the development of solid-state adsorbents for vehicular hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2784–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdanghi, G.; Schaefer, S.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Application of the modified Dubinin-Astakhov equation for a better understanding of high-pressure hydrogen adsorption on activated carbons. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2019, 45, 25912–25926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarna-Juszkiewicz, D.; Cader, J.; Wdowin, M. From coal ashes to solid sorbents for hydrogen storage. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Z.S.; Doğan, E.E.; Bicil, Z.; Kizilduman, B.K. The effect of Li-doping and doping methods to hydrogen storage capacities of some carbonaceous materials. Fuel 2025, 396, 135280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assyl, Sh.; Botakoz, S.; Saule, Zh. Dimensions, structure, and morphology variations of carbon-based materials for hydrogen storage: a review. Discover Nano 2025, 20, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, E.; Chahine, R.; Bose, T.K. Hydrogen adsorption in carbon nanostructures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2001, 26, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Johnson, J.K. Optimization of Carbon Nanotube Arrays for Hydrogen Adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 4809–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kundalwal, S.I. Comparative analysis of hydrogen sorption in large-sized single-walled carbon nanotubes and multi-walled carbon nanotubes: A molecular dynamics study. Mater. Today 2024, 114, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilov, U.; Uljayev, U.; Mehmonov, K.; Nematollahi, P.; Yusupov, M.; Neyts, E.C. Can endohedral transition metals enhance hydrogen storage in carbon nanotubes? Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2024, 55, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrushenko, I.K. DFT Calculations of Hydrogen Adsorption inside Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 9876015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, F.; Nguyen, D.D.; Pourkhalil, M.; Pirouzfar, V. Effect of Single- and Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes with Activated Carbon on Hydrogen Storage. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2021, 44, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, Ch.-G.; Zhou, H.; Ye, E.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Loh, X.J. Current Research Trends and Perspectives on Solid-State Nanomaterials in Hydrogen Storage. Research 2021, 2021, 3750689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, M.A.S.; Abdelsalam, H.; Teleb, N.H.; Abd-Elkader, O.H.; Zhang, Q. Exploring the structural, electronic, and hydrogen storage properties of hexagonal boron nitride and carbon nanotubes: insights from single-walled to doped double-walled configurations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçinkaya, F.N.; Doğan, M.; Bicil, Z.; Kizilduman, B.K. Effect of functionalization and Li-doping methods to hydrogen storage capacities of MWCNTs. Fuel 2024, 372, 132274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, B.; Kamali, M.; Zandi, S.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Raf Dewil, R.; Costa, M.E.V.; Capela, I. Simplified hydrogen storage in nanocomposites optimized by artificial intelligence. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicil, Z. Adsorptıon kinetics and mechanism of hydrogen on pristine and functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Fuel 2026, 403, 136130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Anderson, P.E.; Chambers, A.; Tan, C.D.; Hidalgo, R.; Rodriguez, N.M. Further studies of the interaction of hydrogen with graphite nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 10572–10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeland, A.J. The storage of hydrogen for vehicular use—A review and reality check. Int. Sc. J. Altern. Energy Ecol. 2002, 1, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Koval’, Y.M. Features of Relaxation Processes During Martensitic Transformation. Usp. Fiz. Met. 2005, 6, 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lobodyuk, V.A.; Estrin, E.I. Martensitic Transformations; Cambridge International Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nechaev, Y.S.; Denisov, E.A.; Cheretaeva, A.O.; Shurygina, N.A.; Kostikova, E.K.; Öchsner, A.; Davydov, S. Y. On the Problem of “Super” Storage of Hydrogen in Graphite Nanofibers. C 2022, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Brien, S.C.; Curl, R.F.; Smalley, R.E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, S. Fullerene for Green Hydrogen Energy Application. In Carbon-based Nanomaterials for Green Applications; Kumar, U., Sonkar, P.K., Tripathi, S.L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loufty, R.O.; Wexler, E.M. Feasibility of fullerene hydride as a high capacity hydrogen storage material. In Proceedings of the 2001 DOE Hydrogen Program Review, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17-19 April 2001; pp. 467–477. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, M.H.F.; Kawazoe, Y. Cluster expansion method for adsorption: Application to hydrogen chemisorption on graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 085410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecho, T; Güttler, A.; Sha, X.; Jackson, B.; Küppers, J. Adsorption of hydrogen and deuterium atoms on the (0001) graphite surface. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 8486–8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchkovskii, S.; Tse, J.S.; Yurchenko, S.N.; Zhechkov, L.; Heine, Th; Seifert, G. Graphene nanostructures as tunable storage media for molecular hydrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 10439–10444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wei, X.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J. Measurement of the Elastic Properties and Intrinsic Strength of Monolayer Graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z.M.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, R.Q.; Tan, T.T.; Li, S. Al doped graphene: A promising material for hydrogen storage at room temperature. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 074307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, G.; Zhu, Y.; Piner, R.; Skipper, N.; Ellerby, M.; Ruoff, R. Synthesis of graphene-like nanosheets and their hydrogen adsorption capacity. Carbon 2010, 48, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovskaya, V.V.; Zobelli, A.; Teillet-Billy, D.; Rougeau, N.; Sidis, V.; Briddon, P.R. Hydrogen adsorption on graphene: a first principles study. Eur. Phys. J. B 2010, 76, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Stuckert, N.R.; Yang, R.T. Unique hydrogen adsorption properties of graphene. AIChE J. 2010, 57, 2902–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicko, M.; Seydou, M.; Darkrim Lamari, F.; Langlois, P.; Maurel, F.; Levesque, D. Hydrogen adsorption on graphane: An estimate using ab-initio interaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2017, 42, 10057–10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkrim Lamari, F.; Levesque, D. Hydrogen adsorption on functionalized graphene. Carbon 2011, 49, 5196–5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Jana, D. First-principles calculation of the electronic and optical properties of a new two-dimensional carbon allotrope: tetra-penta-octagonal graphene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 24758–24767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, K.; Li, J.; Gao, R.; Feng, R. Hydrogen storage performances of TPO-graphene system: first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 23951–23965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, P.; Ghosh, S. Hydrogen storage using novel graphene-carbon nanotube hybrid. Mater. Today 2023, 76, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.A.; Hossain, M.M. Hydrogen storage via adsorption: A review of recent advances and challenges. Fuel 2025, 387, 134273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Zh.; Li, Ch. Magic of hydrogen spillover: Understanding and application. Green Energy Environ. 2022, 7, 1161–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueking, A.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen Spillover from a Metal Oxide Catalyst onto Carbon Nanotubes—Implications for Hydrogen Storage. J. Catal. 2002, 206, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueking, A.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen storage in carbon nanotubes: Residual metal content and pretreatment temperature. AIChE J. 2003, 49, 1556–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P.; Hibbs, A.R. Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.J.; Kim, T.; Im, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, K.; Jung, H.; Park, C.R. MOF-derived hierarchically porous carbon with exceptional porosity and hydrogen storage capacity. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoudi, A.; Mokaya, R. Preparation and hydrogen storage capacity of templated and activated carbons nanocast from commercially available zeolitic Imidazolate framework. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 22, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-L.; Liu, B.; Lan, Y.-Q.; Kuratani, K.; Akita, T.; Shioyama, H.; Zong, F.; Xu, Q. From metal–organic framework to nanoporous carbon: Toward a very high surface area and hydrogen uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11854–11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdanghi, G.; Canevesi, R.L.S.; Celzard, A.; Thommes, M.; Fierro, V. Characterization of Carbon Materials for Hydrogen Storage and Compression. C 2020, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabe, A.; Ouzzine, M.; Taylor, E.E.; Stadie, N.P.; Uchiyama, N.; Kanai, T.; Nishina, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Pan, Zh.-Z.; Kyotani, T.; Nishihara, H. High-density monolithic pellets of double-sided graphene fragments based on zeolite-templated carbon. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 7503–7507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S.S.; Putnam, S.T.; Stadie, N.P. Volumetrics of Hydrogen Storage by Physical Adsorption. Inorganics 2021, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fierro, V.; Aylon, E.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Celzard, A. High-performances carbonaceous adsorbents for hydrogen storage. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2013, 416, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, L.S.; Mokaya, R. Cigarette butt-derived carbons have ultra-high surface area and unprecedented hydrogen storage capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 12, 2552–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpourmpakis, G.; Froudakis, G.E.; Lithoxoos, G.P.; Samios, J. Effect of curvature and chirality for hydrogen storage in single-walled carbon nanotubes: A Combined ab initio and Monte Carlo investigation. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 144704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpourmpakis, G.; Tylianakis, E.; Froudakis, G.E. Carbon Nanoscrolls: A Promising Material for Hydrogen Storage. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1893–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintaş, Ç.; Keskin, S. On the shoulders of high-throughput computational screening and machine learning: Design and discovery of MOFs for H2 storage and purification. Mater. Today Energy 2023, 38, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfelder, J.O.; Curtiss, C.F.; Bird, R.B. Molecular Theory of Gases and Liquids; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, M.; Nenoff, T.M.; Mitchell, M.C. Selectivities for binary mixtures of hydrogen/methane and hydrogen/carbon dioxide in silicalite and ETS-10 by Grand Canonical Monte Carlo techniques. Fluid Phas. Equilibr 2006, 247, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustinov, E.; Tanaka, H.; Miyahara, M. Low-temperature hydrogen-graphite system revisited: Experimental study and Monte Carlo simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 024704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, M.N.; Dengg, T.; Gehringer, D.; Holec, D. Adsorption of H2 on Penta-Octa-Penta Graphene: Grand Canonical Monte Carlo Study. C 2020, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, J.; Jin, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zou, R.; Meng, Q.; Liu, K.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q. High-pressure hydrogen adsorption in clay minerals: Insights on natural hydrogen exploration. Fuel 2023, 344, 127919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, N.; Ungerer, P. Hydrogen/hydrocarbon phase equilibrium modelling with a cubic equation of state and a Monte carlo method. Fluid Phase Equilibr. 2007, 254, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaura, R.S.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, P.K.; Lal, C.; Singh, M.; Palsania, H.S; Vijay, Y.K. Role of interlayer spacing and functional group on the hydrogen storage properties of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2016, 41, 9454–9461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lazaro, C.; Bachaud, P.; Moretti, I.; Ferrando, N. Predicting the phase behavior of hydrogen in NaCl brines by molecular simulation for geological applications. BSGF-Earth Sci. Bull. 2019, 190, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Clennell, M.B.; Dewhurst, D.N. Transport Properties of NaCl in Aqueous Solution and Hydrogen Solubility in Brine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 8900−8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office. DOE Technical Targets for Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Light-Duty Vehicles. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/doe-technical-targets-onboard-hydrogen-storage-light-duty-vehicles (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Kurtz, J.; Ainscough, C.; Simpson, L.; Caton, M. Hydrogen Storage Needs for Early Motive Fuel Cell Markets. In Technical Report NREL/TP-5600-52783, November 2012.

- U.S. Departement of Energy. Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office. Target Explanation Document: Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Light-Duty Fuel Cell Vehicles. https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/articles/target-explanation-document-onboard-hydrogen-storagelight-duty-fuel-cell.

- Ahluwalia, R.K.; Hua, T.Q.; Peng, J.K.; Papadias, D.; Kumar, R. System Level Analysis of Hydrogen Storage Options. In Proceedings of the 2011 DOE Hydrogen Program Review, Washington, DC, USA, 9-13 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, A.C.; Gennett, T.; Alleman, J.L.; Jones, K.M.; Parilla, P.A.; Heben, M.J. Carbon Nanotube Materials for Hydrogen Storage. In Proceedings of the 2000 DOE Hydrogen Program Review, San Ramon, CA, USA, 9-11 May 2000; pp. 421–440. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Eddaoudi, M.; O’Keeffe, M; Yaghi, O.M. Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable highly porous metal-organic framework. Nature 1999, 402, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Férey, G. Hybrid porous solids: past, present, future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebanoff, L.E.; Ott, K.C.; Simpson, L.J.; O’Malley, K.; Stetson, N.T. Accelerating the Understanding and Development of Hydrogen Storage Materials: A Review of the Five-Year Efforts of the Three DOE Hydrogen Storage Materials Centers of Excellence. Metall. Mater. Trans. E 2014, 1, 81–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villajos, J.A. Experimental Volumetric Hydrogen Uptake Determination at 77 K of Commercially Available Metal-Organic Framework Materials. C 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, S.; Akhbari, K.; Farnia, S.M.F.; Tylianakis, E.; Froudakis, G.E.; White, J.M. Solvent-Directed Construction of a Nanoporous Metal-Organic Framework with Potential in Selective Adsorption and Separation of Gas Mixtures Studied by Grand Canonical Monte Carlo Simulations. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202300455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.T.X.; Ngan, V.T.; Ngoc, N.T.Y.; Chihaia, V.; Son, D.N. Hydrogen storage in M(BDC) (TED)0.5 metal–organic framework: physical insights and capacities. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19891–19902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.J.; Ahmed, A.; Kuthuru, S.; Matzger, A.; Purewal, J.; Veenstra, M. HyMARC Seedling: Optimized Hydrogen Adsorbents via Machine Learning and Crystal Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2019 DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program, Arlington, VA, USA, 29 April – 1 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlberg, M.; Karlsson, D.; Zlotea, C.; Jansson, U. Superior hydrogen storage in high entropy alloys. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hájková, P.; Horník, J.; Čižmárová, E.; Kalianko, F. Metallic Materials for Hydrogen Storage—A Brief Overview. Coatings 2022, 12, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, T.; Khan, M.M.; Pali, H.S. The future of hydrogen economy: Role of high entropy alloys in hydrogen storage. J. Alloy. Compd. 2024, 1004, 175668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agafonov, A.; Pineda-Romero, N.; Witman, M.D.; Enblom, V.; Sahlberg, M.; Nassif, V.; Lei, L.; Grant, D.M.; Dornheim, M; Ling, S.; Stavila, V.; Zlotea, C. Promising Alloys for Hydrogen Storage in the Compositional Space of (TiVNb)100-x(Cr,Mo)x High-Entropy Alloys. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 41991–42003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rango, P.; Chaise, A.; Charbonnier, J.; Fruchart, D.; Jehan, J.; Marty, Ph.; Miraglia, S.; Rivoirard, S.; Skryabina, N. Nanostructured magnesium hydride for pilot tank development. J. Alloy. Compd. 2007, 446–447, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züttel, A.; Rentsch, S.; Fischer, P.; Wenger, P.; Sudan, P.; Mauron, Ph.; Emmenegger, Ch. Hydrogen storage properties of LiBH₄. J. Alloy. Compd. 2003, 356-357, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauron, Ph.; Buchter, F.; Friedrichs, O.; Remhof, A.; Bielmann, M.; Zwicky, Ch.N.; Züttel, A. Stability and Reversibility of LiBH4. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didisheim, J.-J.; Zolliker, P.; Yvon, K.; Fischer, P.; Schefer, J.; Gubelmann, M.; Williams, A.F. Dimagnesium iron(II) hydride, Mg2FeH6, containing octahedral FeH64- anions. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 1953–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakintuna, B.; Lamari-Darkrim, F.; Hirscher, M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2007, 32, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galey, B.; Auroux, A.; Sabo-Etienne, S.; Dhaher, S.; Grellier, M.; Postole, G. Improved hydrogen storage properties of Mg/MgH₂ thanks to the addition of nickel hydride complex precursors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2019, 44, 28848–28862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruchart, D.; Jehan, M.; Skryabina, N.; de Rango, P. Hydrogen Solid State Storage on MgH2 Compacts for Mass Applications. Metals 2023, 13, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamari, F.; Weinberger, B.; Langlois, P.; Fruchart, D. Instances of Safety-Related Advances in Hydrogen as Regards Its Gaseous Transport and Buffer Storage and Its Solid-State Storage. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Z.; Wang, P.; Yao, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, D.M.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M. Effect of carbon/noncarbon addition on hydrogen storage behaviors of magnesium hydride. J. Alloy. Compd. 2006, 414, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.; Titus, E.; Salimian, M.; Okhay, O.; Rajendran, S.; Rajkumar, A.; Sousa, J.M.G.; Ferreira, A.L.C.; Gil, J.C.; Gracio, J. Hydrogen Storage for Energy Application. In Hydrogen Storage; Liu, J., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokano, G.; Dehouche, Z.; Galey, B.; Postole, G. Development of a Novel Method for the Fabrication of Nanostructured Zr(x)Ni(y) Catalyst to Enhance the Desorption Properties of MgH₂. Catalysts 2020, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

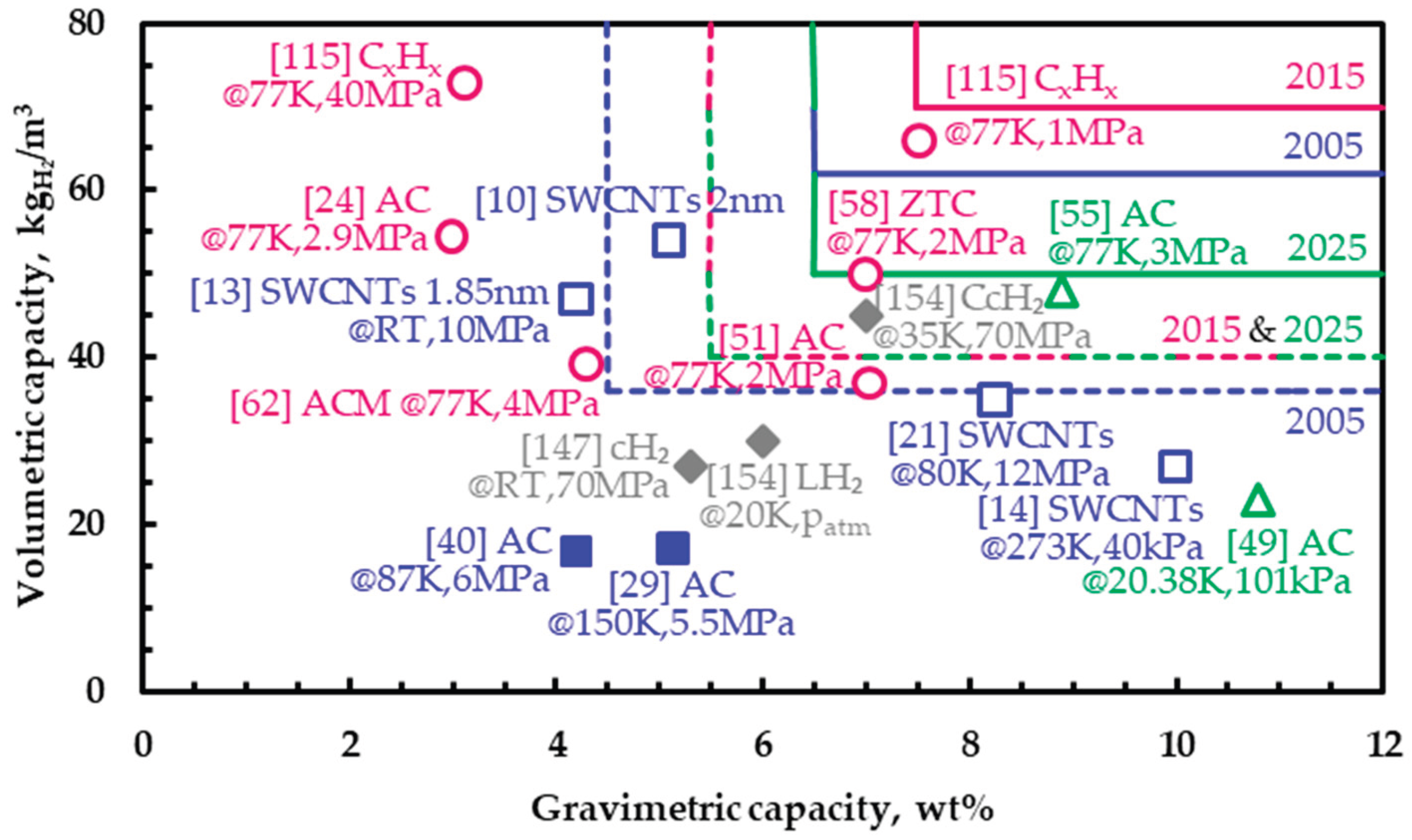

| Targeta | 2005 | 2015b | 2025b |

| Volumetric capacity (kgH₂/msystem3) | 36 | 40 | 40 |

| ‘Ultimate’ volumetric capacity (kgH₂/msystem3) | 62 | 70 | 50 |

| Gravimetric capacity (kgH₂/kgsystem) | 0.045 | 0.055 | 0.055 |

| ‘Ultimate’ gravimetric capacity (kgH₂/kgsystem) | 0.065 | 0.075 | 0.065 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).