1. Introduction — Ancient Revelation, Modern Confirmation

Genesis 6:3 states:

“My Spirit shall not always strive with man, for that he also is flesh; yet his days shall be an hundred and twenty years.”

For millennia, scholars debated whether this referred to a 120-year countdown to the Flood or an intrinsic limit on human life. Remarkably, modern biology—independent of theology—has converged on a similar estimate:

approximately 120 years represents the natural biological boundary of human lifespan.[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]

In the United States today, average life expectancy is ≈78–80 years—barely two-thirds of this potential.[

1,

2,

3] This 20–30% lifespan loss is primarily due to

preventable chronic diseases, not an immutable “aging program.”[

9,

10,

11,

12,

14,

29] The central challenge of 21st-century medicine is therefore not immortality but

restoration: how to reclaim decades of healthy life that biologically “belong” to us.

2. The Biblical Context and Scientific Parallels

Ancient texts describe a steep post-Flood lifespan decline—from Methuselah (969 years) to Abraham (175) to Moses (120). While theological interpretations vary, the pattern is clear: a gradual compression of lifespan toward an apparent ceiling of around 120 years.

Modern science similarly documents a progressive loss of genomic stability, mitochondrial function, and resilience to environmental stressors over the human lifespan.[

6,

9,

14,

15,

22,

30,

31] The parallels can be framed as:

Environmental degradation → oxidative stress and DNA damage[13,14,15,22,23] Genomic entropy → accumulation of somatic mutations[7,9,13,30,31] Micronutrient depletion → impaired repair enzymes and redox systems[21] Toxin accumulation → mitochondrial decay and bioenergetic failure[13,22,23,32]

Thus, ancient observations of declining lifespan find mechanistic echoes in contemporary molecular gerontology.

3. The 120-Year Limit — A Biological Ceiling

Several independent lines of evidence converge on a human lifespan limit of ~120–125 years:

Empirical data: Jeanne Calment’s life to 122 years 164 days remains the longest verified human lifespan.[

1,

2,

3] No documented case has reliably exceeded this record.

Mathematical modeling: Mortality patterns follow the Gompertz–Makeham law, with hazard rates accelerating and then plateauing such that survival beyond 120–125 years becomes vanishingly small.[

4,

29,

33]

Cellular models: Classic work by Hayflick demonstrated that human fibroblasts undergo only ~50–60 population doublings, consistent with a finite replicative potential.[

5]

Molecular clocks: DNA-methylation-based “epigenetic clocks” and other hallmarks of aging plateau near the 110–120-year range, suggesting intrinsic limits of epigenetic and mitochondrial repair.[

6,

7,

8,

18,

30,

31]

Together, these empirical, mathematical, cellular, and molecular data define a thermodynamic boundary of human life: a design limit centered around 120 years.

4. Why We Die 20 – 40 Years Sooner Than We Should

Even if humans rarely reach 120, it is reasonable—based on demographic and mechanistic data—to expect healthy life into the 90s for many individuals.[

10,

11,

12,

25,

26,

29,

33] Yet in most developed nations, average life expectancy remains ~78–80 years.[

10,

11,

12]

This gap arises primarily from disease-driven premature mortality, dominated by:

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Cancer

Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome

Neurodegenerative diseases

Chronic liver and kidney diseases[10–12]

Modeling shows that eliminating the top 10 causes of death would increase average life

expectancy only to ≈95–100 years.[10–12,29] In other words:

~20 years are lost to preventable chronic disease, and

-

an additional ~20 years reflect intrinsic biological aging even after optimal disease control.[7,10–12,18,29,33]

This implies that anti-aging medicine must operate in two domains:

(1) reversing or preventing chronic disease, and

(2) addressing the underlying biology of aging itself.

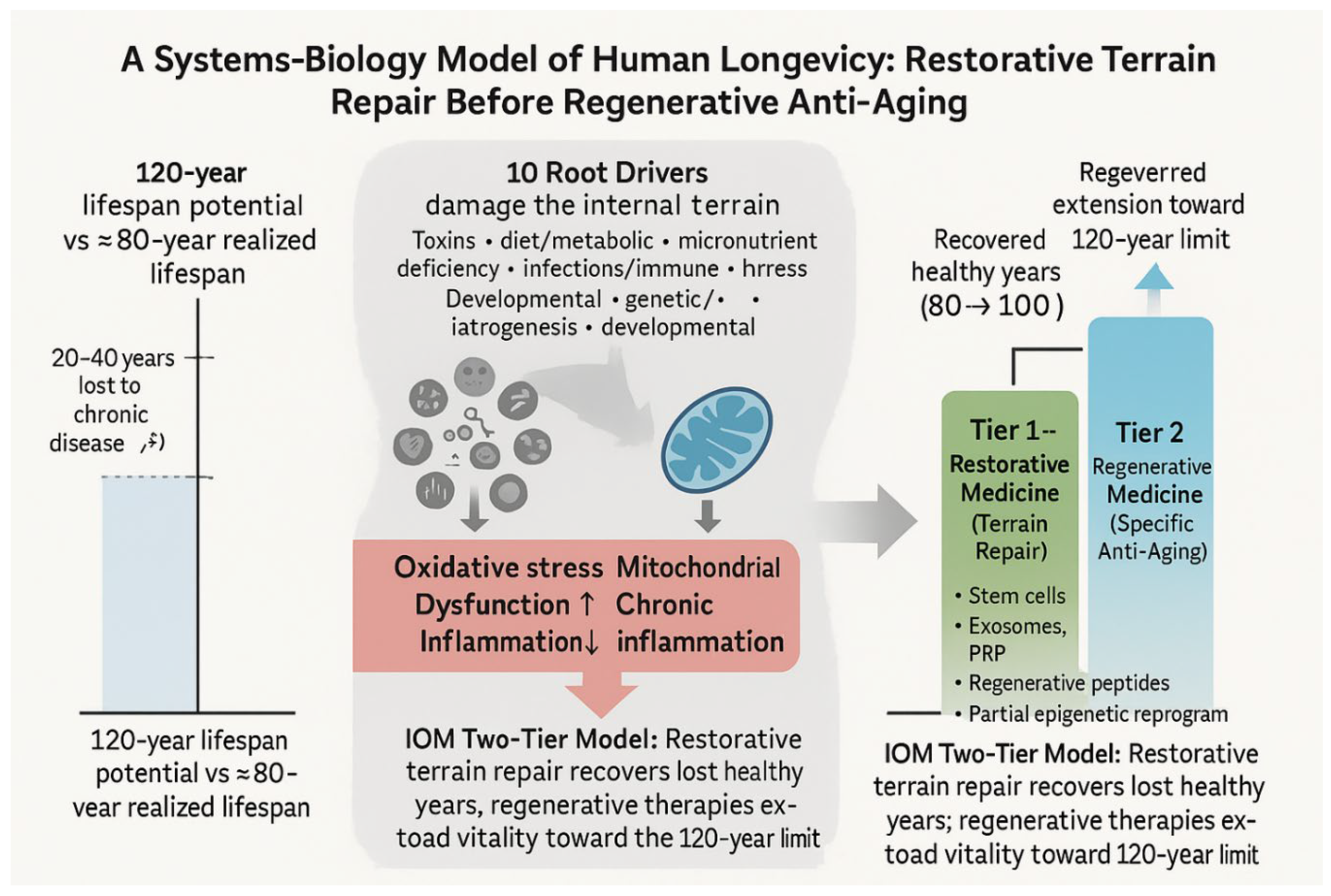

5. The True Purpose of Anti-Aging Medicine: Two Complementary Domains

5.1. Two Tier Anti-Aging Framework — Restorative and Regenerative

Human biology appears engineered for a

maximum potential lifespan of about 120 years.[

4,

11,

12,

17,

18,

24,

33] Yet the current U.S. average hovers near 80 years.[

10,

11,

12] This 40-year shortfall can be conceptualized as:

∙ ~ 20 years lost to preventable chronic disease, and

∙

~ 20 years representing intrinsic biological aging even with disease control.[

7,

10,

11,

12,

18,

29,

33]

Accordingly, anti-aging medicine must operate across two complementary domains:

Table 1.

Two-Tier Anti-Aging Framework.

Table 1.

Two-Tier Anti-Aging Framework.

| Domain |

Primary Target |

Main Goal |

Core IOM Strategy |

|

1️⃣ Restorative (anti-disease) Medicine

|

Metabolic dysfunction, oxidative stress, micronutrient deficiency, endocrine imbalance, inflammation |

Reclaim ~20 years of lost lifespan (80 → 100 yrs) |

Detoxification → Orthomolecular repletion → Metabolic/ICV repair → Hormonal optimization → Mitochondrial support → NAD⁺ restoration → Senolytics → Epigenetic stabilization[8,14,18–22,26, 34] |

|

2️⃣ Regenerative (specific anti-aging) Medicine

|

Structural and cellular loss; stem cell depletion; extracellular matrix deterioration |

Extend the remaining ~20 years (100 → 120 yrs) |

Stem cells, exosomes, PRP, regenerative peptides, telomere/epigenetic partial reprogramming, tissue engineering[18,19,20] |

Restorative Medicine addresses the upstream root drivers of chronic disease—environmental toxins/toxicants, micronutrient depletion, metabolic rigidity, chronic inflammation, endocrine imbalance, and oxidative stress[

4,

13,

14,

15,

21,

22,

23,

35].

Only once disease burden and intracellular dysfunction are minimized can regenerative medicine safely and meaningfully modulate the cellular machinery of aging—stem cell depletion, matrix stiffening, telomere erosion, and epigenetic drift.[

5,

6,

7,

8,

18,

19,

20,

29].

In practical terms:

First reclaim the lost 20 years, then pursue the next 20.

6. Why Restorative Medicine Is the Foundation of Longevity

6.1. Terrain First: Correcting the Internal Milieu

The body’s longevity potential depends heavily on its internal terrain—free of excessive toxic load, nutritional deficiency, metabolic rigidity, and chronic inflammation. If these imbalances persist, interventions such as senolytics, stem-cell infusions, or epigenetic reprogramming act on dysfunctional cells within a pathologic environment, yielding minimal or unstable results.[

4,

7,

8,

9,

14,

15,

21,

22,

23]

Vitamin C is a near-essential cofactor for appropriate epigenetic programming and differentiation in several stem cell types, while vitamin D is a key modulator of mesenchymal and osteogenic progenitor proliferation and lineage choice. Deficiencies in either nutrient tend to dysregulate stem cell behavior rather than completely abolish it.[

36,

37,

38] Accordingly, regenerative efforts in a vitamin C– or D-deficient terrain are intrinsically compromised.

6.2. Regeneration builds upon restoration

While both restorative and regenerative domains are integral to anti-aging medicine, Restorative Medicine—the anti-disease phase—is primary and indispensable.

Mitochondrial rejuvenation, NAD⁺ replenishment, and partial reprogramming require adequate antioxidant reserves, micronutrient cofactors, and metabolic flexibility—the very outcomes achieved by restorative orthomolecular therapy.[

4,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

24,

25]

Hierarchical sequence of intervention:

∙ Restorative (Anti-Disease) Phase

o Core objective: Re-establish homeostasis; remove toxic and metabolic burdens

o Biological prerequisite: Functional mitochondria; balanced redox and nutrient status

o Representative strategies: Detoxification, orthomolecular repletion, metabolic realignment (including ICV axis)[

39], circadian repair, hormonal rebalancing

∙ Regenerative (True Anti-Aging) Phase

o Core objective: Extend biological youth beyond a disease-free state

o Biological prerequisite: Restored terrain and robust cellular energy

o Representative strategies: NAD⁺/sirtuin activation, senolytics, telomere and epigenetic reprogramming, stem cell and exosome therapies[

18,

19,

20]

Philosophically, regenerative medicine aims to “rebuild the house,” but restorative medicine first clears the debris and repairs the foundation. In Linus Pauling’s orthomolecular vision, an optimal molecular environment precedes any higher function. This sequence reflects the IOM doctrine of Root Cause → Mechanism → Manifestation: without correcting the root cause, any mechanistic repair is temporary.

In modern practice, many clinics invert this sequence, jumping directly to stem cells, peptides, or “biohacking” gadgets while ignoring mitochondrial decay, oxidative stress, toxic load, micronutrient deficits, and endocrine chaos. The result is

temporary benefit without durable rejuvenation.[

4,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

24,

25]

IOM reverses this error:

No true regeneration without prior restoration.

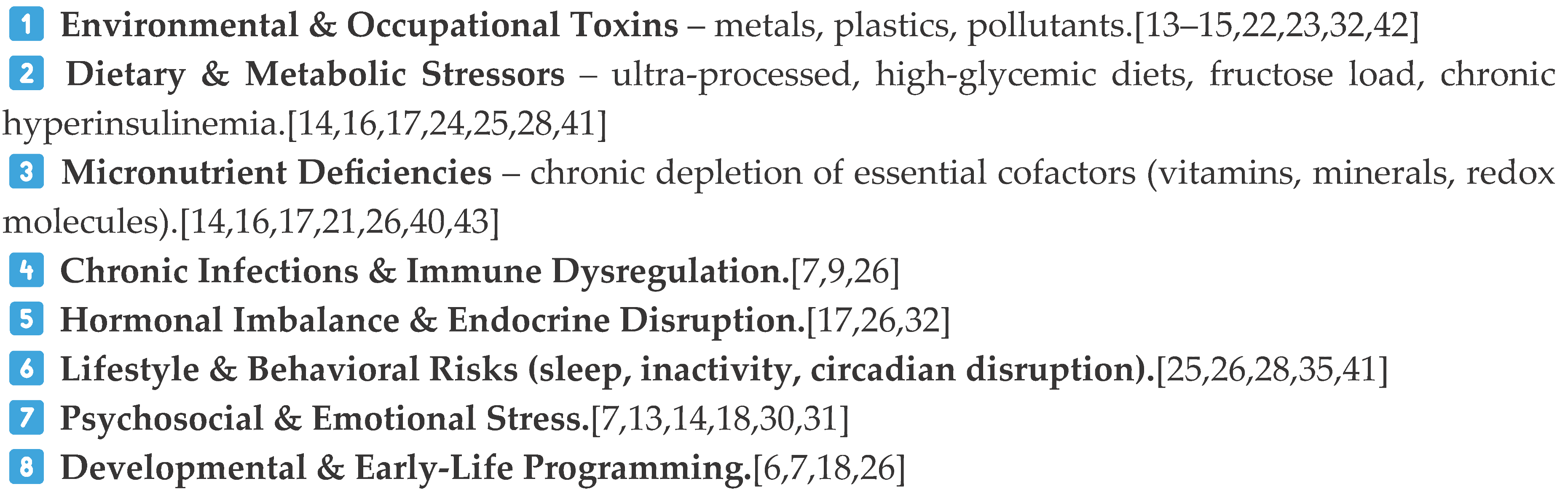

7. Why the Ten Root Drivers Directly Affect Stem Cell Infusion Efficiency

A critical but underappreciated reality is that regenerative medicine often fails not because stem cells are intrinsically weak, but because the host terrain is biologically hostile to regeneration.

Within the IOM framework,

each of the Ten Root Drivers creates a microenvironment in which infused stem cells struggle to survive, engraft, or differentiate properly.[

4,

14,

15,

21,

22,

23,

26,

27,

28,

35,

40,

41]

7.1. Environmental & Occupational Toxins

Heavy metals, plastics, and solvents increase oxidative stress, damage mitochondrial respiratory chains, and disrupt calcium signaling—all of which can kill infused stem cells within hours.[

13,

14,

15,

22,

23,

32,

42]

∙ Outcome: poor cell survival and minimal clinical effect.

7.2. Dietary & Metabolic Stressors

Hyperglycemia, high fructose intake, and insulin resistance activate mTOR, NF-κB, and glycation pathways that:

∙ inhibit mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation

∙ increase apoptosis

∙ reduce angiogenesis and tissue repair capacity

Metabolic chaos—including insulin resistance and cortisol dysregulation along the

ICV Axis (insulin–cortisol–vitamin C)—is intrinsically toxic to stem cells.[

18,

19,

24,

25,

39]

∙ Outcome: stem cells cannot integrate or repair damaged tissues effectively.

7.3. Micronutrient Deficiencies

Deficiencies in vitamin C, vitamin D, magnesium, zinc, and B3/NAD⁺ precursors compromise:

∙ epigenetic programming

∙ collagen matrix formation

∙ mitochondrial ATP production

This results in “false differentiation signals,” DNA methylation errors, and poor extracellular matrix support.

∙

Outcome: stem cells remain inactive, senesce early, or differentiate incorrectly.Vitamin C and vitamin D are especially prominent in this category.[

36,

37,

38]

7.4. Chronic Infections & Immune Dysregulation

Latent or low-grade infections increase TNF-α, IL-6, interferons, and other inflammatory mediators that:

∙ kill infused MSCs

∙ recruit immune cells that attack infused cells as “abnormal”

∙ suppress regenerative signaling pathways[

7,

18,

26]

∙ Outcome: low engraftment and rapid loss of infused cells.

7.5. Hormonal Imbalance & Endocrine Disruption

Stem cell migration, adhesion, and differentiation are all hormone-sensitive. For example:

∙ high cortisol inhibits MSC proliferation

∙ low estrogen or testosterone impairs bone, muscle, and endothelial regeneration[

17,

26,

32]

∙ Outcome: weak or inconsistent clinical responses to regenerative therapies.

7.6. Lifestyle & Behavioral Risks

Poor sleep, inactivity, and circadian disruption alter the expression of core clock genes (e.g., BMAL1, CLOCK), impairing stem cell cycling and mitochondrial function.[

28,

41]

∙ Outcome: diminished regenerative potential even with high-dose cell infusions.

7.7. Psychosocial & Emotional Stress (HPA Axis Activation)

Chronic stress activates the HPA axis, elevating cortisol and leading to:

∙ suppressed immune repair

∙ vitamin C depletion

∙ NAD⁺ exhaustion

∙ Outcome: regenerative therapies fail to “take.”

7.8. Developmental & Early-Life Programming

Early-life epigenetic imprints shape adult stem cell reserves, telomere length, and mitochondrial function.[6–8, 18]

∙ Outcome: baseline regenerative capacity is reduced before therapy even begins.

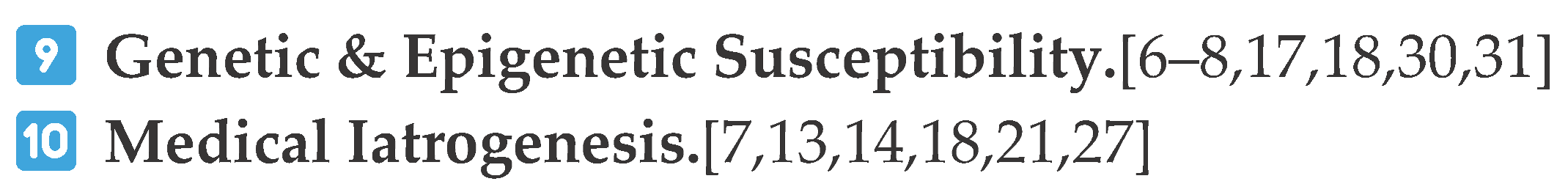

7.9. Genetic & Epigenetic Susceptibility

Polymorphisms in antioxidant enzymes, detoxification pathways, mitochondrial proteins, and cell-cycle regulators modulate stem cell performance and response to regenerative therapies.[

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

30,

31]

∙ Outcome: some patients respond well, others poorly—unless terrain is corrected.

7.10. Medical Iatrogenesis

Pharmaceuticals (statins, PPIs, steroids, chemotherapeutic agents) and radiation can damage mitochondria and suppress MSC differentiation.[

7,

13,

14,

18,

21,

27]

∙ Outcome: regenerative therapies cannot overcome iatrogenic mitochondrial injury without prior restorative intervention.

7.11. Summary Statement

Stem cell therapy typically does not fail because stem cells are inherently weak—it fails because the patient’s biological terrain is compromised.

All Ten Root Drivers converge on three destructive mechanisms:

1. Oxidative stress

2. Mitochondrial dysfunction

3.

Chronic inflammation[

7,

9,

13,

14,

15,

21,

22,

23,

27,

28,

32,

34,

40,

41,

43]

These same mechanisms both drive chronic disease and impair stem cell survival before they can exert therapeutic effects. This explains why Restorative Medicine must precede Regenerative Medicine, and why IOM’s terrain-based, root-cause framework is a necessary foundation for any successful anti-aging or regenerative strategy.

8. The “Magic Pill” Fallacy

The modern “anti-aging industry” is saturated with claims of miracle pills and shortcuts. However:

∙ No single molecule can override decades of oxidative, metabolic, and toxic injury.[

4,

7,

9,

14,

16,

17,

21]

∙ Aging is not caused by a single deficiency but by a

systems-level collapse involving redox, immune, metabolic, and endocrine feedback loops.[

7,

9,

17]

Promoters who suggest otherwise either misunderstand the biology or misrepresent it. Restoration must precede regeneration.

Biological rejuvenation succeeds only on a corrected internal terrain. Without detoxification, micronutrient sufficiency, metabolic flexibility, and hormonal balance, senolytics or stem-cell therapies act on a compromised substrate and yield, at best, transient benefits.[

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

24,

25,

34]

This hierarchy again reflects the IOM doctrine:

Root Cause→Mechanism→Manifestation.

As Pauling emphasized, an optimal molecular environment precedes higher function—no true regeneration without prior restoration.

Restoration Before Regeneration

Biological rejuvenation succeeds only on a corrected internal terrain.

Without detoxification, micronutrient sufficiency, and metabolic flexibility, senolytics or stem-cell therapies act on a compromised substrate and yield transient benefit.

This hierarchy reflects the IOM doctrine: Root Cause → Mechanism → Manifestation.

As Linus Pauling emphasized, optimal molecular environment precedes higher function—no true regeneration without prior restoration.

9. An IOM Framework for Restoring the 120-Year Potential

Within the IOM model, shortened human lifespan reflects cumulative injury from ten upstream

root drivers.[

21,

26,

27,

28,

34,

35,

40,

41,

42]

10. From Theology to Thermodynamics

The 120-year limit bridges two interpretive frameworks:

∙ Theologically, Genesis 6:3 reflects an early recognition of human finitude.

∙

Scientifically, modern biogerontology and thermodynamics quantify a boundary of entropy, repair capacity, and systemic resilience.[

10,

11,

12,

29,

30,

31,

33]

Whether viewed as divine insight or ancient observation, Genesis 6:3 anticipated what modern science now confirms: human design allows for roughly 120 years, but chronic disease and environmental injury shorten this by decades.[

7,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

22,

23,

29,

30,

31]

The mission of Integrative Orthomolecular Medicine is therefore not to seek immortality, but

restoration—to regain the years that biology has already granted us, by correcting the root drivers of disease and rebuilding the terrain on which regeneration depends.[

21,

26,

27,

28,

32,

34,

35,

40,

41,

43]

11. Conclusions

Evidence from demographics, cellular biology, epigenetic clocks, and thermodynamics collectively supports a human lifespan potential of approximately 120 years.[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

29,

30,

31] The persistent gap between this potential and current life expectancy reflects

systemic, preventable dysfunction rather than a fixed, inevitable aging program.[

7,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

22,

23,

33]

This article proposes a Two-Tier Anti-Aging Model in which:

1.

Restorative Medicine focuses on detoxification, orthomolecular repletion, metabolic realignment (including the ICV axis), mitochondrial and NAD⁺ support, hormonal optimization, and epigenetic stabilization to reclaim ~20 years of life lost to chronic disease.[

7,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

24,

25,

26,

35,

34,

43,

40]

2.

Regenerative Medicine applies stem cells, exosomes, regenerative peptides, and partial reprogramming to extend vitality toward the 120-year boundary—

but only after the terrain is corrected.[

18,

19,

20,

36,

37,

38]

Within this architecture, Integrative Orthomolecular Medicine provides a coherent, evidence-informed roadmap for restoring human lifespan potential—not by chasing isolated “magic bullets,” but by systematically repairing the underlying biological terrain that determines whether any advanced therapy can succeed.

References

- Milholland, B. Jeanne Calment, Actuarial Paradoxography and the Limit to Human Lifespan. Rejuvenation Res 2020, 23, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne Calment | Gerontology Research Group. Available online: https://www.grg-supercentenarians.org/jeanne-calment/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Robin-Champigneul, F. Jeanne Calment’s Unique 122-Year Life Span: Facts and Factors; Longevity History in Her Genealogical Tree. Rejuvenation Res 2020, 23, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbi, E.; Lagona, F.; Marsili, M.; et al. The Plateau of Human Mortality: Demography of Longevity Pioneers. Science 2018, 360, 1459–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L. THE LIMITED IN VITRO LIFETIME OF HUMAN DIPLOID CELL STRAINS. Exp Cell Res 1965, 37, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA Methylation Age of Human Tissues and Cell Types. Genome Biol 2013, 14, R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; et al. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Wilson, J.G.; et al. DNA Methylation GrimAge Strongly Predicts Lifespan and Healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 303–327. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30669119/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; et al. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Global Health Estimates 2023: Life Expectancy and Leading Causes of Death and Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators Global Age-Sex-Specific Fertility, Mortality, Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE), and Population Estimates in 204 Countries and Territories, 1950-2019: A Comprehensive Demographic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1160–1203. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.L.; Kochanek, K.D.; Xu, J.; et al. Deaths: Final Data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2024, 73, 1–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Human Radiation and Disease. Cell 2015, 163, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, B.N.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Hagen, T.M. Oxidants, Antioxidants, and the Degenerative Diseases of Aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993, 90, 7915–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Bellinger, D.; Bergman, Å.; et al. The Faroes Statement: Human Health Effects of Developmental Exposure to Chemicals in Our Environment. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00114.x. 2008, 102, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alehagen, U.; Aaseth, J.; Johansson, P. Reduced Cardiovascular Mortality 10 Years after Supplementation with Selenium and Coenzyme Q10 for Four Years: Follow-Up Results of a Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial in Elderly Citizens. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0141641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L.; Brunet, A.; et al. Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease. Cell 2014, 159, 709–713. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009286741401366X. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Liu, C.; Suliburk, J.; et al. Supplementing Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) in Older Adults Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Physical Function, and Aging Hallmarks: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2023, 78, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ryu, D.; Wu, Y.; et al. NAD+ Repletion Improves Mitochondrial and Stem Cell Function and Enhances Life Span in Mice. Science. Available online: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.1126/science.aaf2693. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.; Reddy, P.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; et al. In Vivo Amelioration of Age-Associated Hallmarks by Partial Reprogramming. Cell 2016, 167, 1719–1733.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.C.; Ames, B.N. Vitamin K, an Example of Triage Theory: Is Micronutrient Inadequacy Linked to Diseases of Aging? Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 90, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Balakrishnan, K.; et al. Pollution and Health: A Progress Update. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e535–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Nawrot, T.S.; Baccarelli, A.A. Hallmarks of Environmental Insults. Cell. 2021, 184, pp. 1455–1468. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867421000866. [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, M.; Yoshino, J.; Kayser, B.D.; et al. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Increases Muscle Insulin Sensitivity in Prediabetic Women. Science 2021, 372, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, B.J.; Willcox, D.C.; Todoriki, H.; et al. Caloric Restriction, the Traditional Okinawan Diet, and Healthy Aging: The Diet of the World’s Longest-Lived People and Its Potential Impact on Morbidity and Life Span. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007, 1114, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Willcox, D.C.; Scapagnini, G. Extending Healthy Ageing: Nutrient Sensitive Pathway and Centenarian Population. Immun Ageing 2012, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R.Z. From Mutation to Metabolism: Root Cause Analysis of Cancer’s Initiating Drivers. 2025. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202509.0903/v1. [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of Intermittent Fasting on Health and Disease Processes. Ageing Res Rev 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olshansky, S.J.; Carnes, B.A.; Cassel, C. In Search of Methuselah: Estimating the Upper Limits to Human Longevity. Science 1990, 250, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetrius, L. Thermodynamics and Evolution. J Theor Biol 2000, 206, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L. Understanding the Odd Science of Aging. Cell. 2005, 120, pp. 437–447. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867405001017. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, L.G.; Philippat, C.; Nakayama, S.F.; et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Implications for Human Health. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2020, 8, 703–718. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213858720301297. [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, J.W.; Carey, J.R.; Christensen, K. Aging. It’s Never Too Late. Science 2003, 301, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.N. Prolonging Healthy Aging: Longevity Vitamins and Proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Available online. 2018, 115, 10836–10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, M.; Herm, A. Exceptional Longevity in Okinawa: Demographic Trends since 1975. J Intern Med 2024, 295, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, I.; Pouzolles, M.; Machado, A.; et al. Vitamin C Deficiency Reveals Developmental Differences between Neonatal and Adult Hematopoiesis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.898827/full. [CrossRef]

- Posa, F.; Di Benedetto, A.; Colaianni, G.; et al. Vitamin D Effects on Osteoblastic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Dental Tissues. Stem Cells Int 2016, 2016, 9150819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hore, T.A.; von Meyenn, F.; Ravichandran, M.; et al. Retinol and Ascorbate Drive Erasure of Epigenetic Memory and Enhance Reprogramming to Naïve Pluripotency by Complementary Mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 12202–12207, Available online: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1809045115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.Z.; Levy, T.E.; Hunninghake, R. The Insulin–Cortisol–Vitamin C Axis: A Missing Regulatory Framework in Metabolic and Hormonal Homeostasis A Narrative Review. 2025. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202512.0217. [CrossRef]

- Page, J. IVC and the Riordan Approach to Adjunctive Cancer Care: 7 Key Questions. Available online: https://riordanclinic.org/2017/10/ivc-riordan-approach-adjunctive-cancer-care-7-key-questions/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Longo, V.D.; Panda, S. Fasting, Circadian Rhythms, and Time-Restricted Feeding in Healthy Lifespan. Cell Metab 2016, 23, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.Z. From Mutation to Metabolism: Environmental and Dietary Toxins as Upstream Drivers of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Chronic Disease. 2025. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202509.1767/v1. [CrossRef]

- IV Vitamin C Therapy. Available online: https://riordanclinic.org/what-we-do/high-dose-iv-vitamin-c/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).