1. Introduction

The Tokaj wine region in northeastern Hungary, situated at the foothills of the Zemplén Mountains, is one of the world’s oldest delimited viticultural areas and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, internationally recognised for its distinctive terroir and historically significant sweet wine styles [

1]. Its heterogeneous volcanic bedrock, loess–clay topsoils and sheltered mesoclimates shaped by the Bodrog and Tisza rivers provide favourable conditions for cultivating white grape varieties with high natural acidity and strong aromatic potential. Among the authorised cultivars, Furmint, Hárslevelű and Sárgamuskotály (Muscat Blanc) are the most emblematic. While Furmint is traditionally associated with structure, tension and ageing capacity, Hárslevelű is valued for its floral, spicy and honeyed aromatic character, reflecting its rich pool of volatile precursors [

2]. These varietal traits contribute not only to Tokaj’s classical botrytised wines but also to the increasingly prominent category of high-quality dry wines that now shape the region’s contemporary identity and export profile [

3].

Sustainability has become a central principle within modern food systems, influencing agricultural production, consumer expectations and gastronomic culture worldwide. According to the FAO, sustainable gastronomy encompasses sourcing, production and consumption practices that protect environmental integrity, support local communities and preserve cultural identity while remaining economically viable [

4]. This multidimensional concept has become especially influential in fine dining, where transparency of origin, low-impact production and regional authenticity represent core values guiding restaurant philosophy and consumer choices [

5,

6].

Wine occupies a unique position within this framework, standing at the intersection of agriculture, culture and regional identity. Terroir-driven wine regions—such as Tokaj—serve as important expressions of locality, biodiversity and historical continuity [

7,

8]. UNESCO World Heritage wine landscapes are increasingly understood as “living cultural systems,” where sustainability is inseparable from heritage preservation and long-term socio-economic resilience [

9]. The Tokaj Wine Region Historic Cultural Landscape exemplifies this connection between tradition, ecological stewardship and place-based identity.

In viticulture, sustainability encompasses soil conservation, biodiversity protection, integrated pest management, reduced chemical inputs and water–energy efficiency. A substantial body of research demonstrates that sustainable vineyard practices enhance grape quality, resilience to climatic variability and ecosystem functioning [

10,

11,

12]. In cool-climate regions such as Tokaj, marked diurnal temperature variation and increasing climatic instability heighten the importance of adaptive practices that preserve aroma precursors, reduce oxidative degradation and support microbial stability during harvest and vinification [

13].

Parallel developments in sustainable winemaking emphasise reduced SO

2 usage, improved oxygen management, circular utilisation of winery by-products, energy-efficient processing and environmentally friendly packaging [

14,

15]. The growth of low-intervention and “natural” winemaking has further accelerated the adoption of microbial management strategies, such as non-

Saccharomyces bioprotection, which aim to reduce chemical additives while enhancing aromatic freshness and microbial stability [

16,

17,

18]. These approaches align closely with consumer preferences favouring authenticity, purity and minimal technological manipulation [

19].

Harvest timing has recently been recognised as an important sustainability-relevant decision. Harvesting grapes during the cooler night or early morning hours can reduce energy requirements for must cooling, limit oxidative reactions, suppress spoilage microorganisms and preserve temperature-sensitive aroma compounds—thereby decreasing the need for corrective enological interventions [

20,

21,

22]. Conversely, grapes harvested during warm midday conditions often require more intensive cooling, higher antioxidant additions and stricter microbial control, increasing both environmental footprint and chemical input. Night harvesting therefore represents a practical low-impact strategy that can simultaneously support sustainability goals and enhance the sensory quality of aromatic white wines.

These considerations resonate strongly with developments in global gastronomy. Michelin Green Star restaurants, for example, prioritise environmentally conscious sourcing, waste reduction and regionally grounded gastronomic narratives [

23]. Recent studies indicate that chefs consider wines produced through sustainable methods—particularly those with clarity, freshness and a strong sense of terroir identity—as especially compatible with contemporary fine dining [

24,

25]. In this context, dry Tokaj wines made from Hárslevelű, with their naturally floral–citrus aromatic signature and compatibility with low-intervention winemaking, are increasingly viewed as gastronomically versatile and sustainability-oriented products.

The interplay of sustainability, regional identity and sensory quality highlights the importance of examining how specific viticultural and enological decisions—such as harvest-time temperature and bioprotection—shape the aromatic profile and gastronomic potential of Tokaj wines. Understanding these relationships contributes not only to scientific knowledge on white wine aroma management but also to broader discussions on how heritage wine regions can adapt to evolving environmental and gastronomic expectations while preserving cultural integrity.

Over the past two decades, the stylistic spectrum of Tokaj wines has broadened considerably. Historically, the region’s prestige rested on sweet, botrytised wines such as Aszú and Szamorodni, whose complexity derives from noble rot (

Botrytis cinerea), oxidative maturation and extended barrel ageing. Today, however, dry Tokaj wines—often sourced from single vineyards—play a central role in expressing site-specific differences and varietal character. Within this context, Hárslevelű has gained renewed focus, as its distinctive aromatic profile makes it particularly suited to fresh, gastronomically versatile dry wines. Its characteristic descriptors—lime blossom, citrus, stone fruit, honey and herbal notes—arise from the interaction of primary grape-derived aroma compounds (including monoterpenes and C

13-norisoprenoids) and fermentation-derived volatiles such as esters and higher alcohols [

26]. Because these compounds are highly sensitive to viticultural and enological conditions, their preservation is essential for producing high-quality dry Tokaj wines.

White wine aroma results from the interaction of primary varietal compounds, fermentation-derived secondary volatiles and tertiary ageing-related constituents. Primary aroma molecules include monoterpenes (e.g., linalool, geraniol, nerol), C

13-norisoprenoids (e.g., β-damascenone), C6 aldehydes and alcohols, and glycosidically bound precursors [

27]. Their concentrations depend on grape variety, vineyard site, canopy management, water status and, critically, berry temperature during ripening and harvest [

28]. Secondary aroma compounds—ethyl esters, acetate esters, higher alcohols and volatile fatty acids—are produced through yeast metabolism and influenced by must composition, fermentation temperature, yeast species and strain, nutrient status and oxygen exposure [

29]. Even subtle changes in these parameters can produce perceptible differences in sensory expression, particularly in varieties such as Hárslevelű, where floral, citrus and honeyed notes require delicate balance.

Considering this, harvest timing and temperature have emerged as key determinants of white wine aroma composition. Studies across multiple cultivars show that grapes harvested under cooler conditions retain higher concentrations of volatile precursors and experience less oxidative degradation than grapes picked during the warmest hours of the day [

30,

31]. Elevated berry temperatures at harvest accelerate enzymatic reactions (e.g., PPO-mediated oxidation), promote pigment browning and reduce the pool of aroma-active molecules. The volatilisation of thermally labile compounds, particularly monoterpenes and certain esters, is also enhanced at higher temperatures. Conversely, night or early-morning harvesting at lower temperatures has been associated with improved aromatic freshness, sensory purity and colour stability, as cooler grapes require less intervention to prevent oxidation.

Tokaj’s microclimate—characterised by warm autumn days and significantly cooler nights—creates conditions under which harvest-time temperature contrasts are likely to have a substantial impact. Midday temperatures during harvest often exceed 25–30 °C, whereas pre-dawn temperatures may remain below 15–18 °C [

32]. Such differences influence both must composition—through differential preservation or degradation of aroma precursors—and must microbiology. Grapes harvested under hot, sun-exposed conditions typically exhibit higher microbial loads and more active indigenous populations than grapes picked under cooler conditions, affecting the onset of fermentation and early aroma formation [

33]. In aromatic cultivars like Hárslevelű, where sensory quality depends heavily on preserving floral, citrus and honeyed notes, the interaction between temperature, oxidation and microbial dynamics becomes particularly significant.

Oxidation is a central concern in aromatic white wine production. Must processed at elevated temperatures and exposed to oxygen undergoes rapid enzymatic and chemical oxidation, leading to browning, loss of varietal freshness and the development of oxidative off-notes [

34]. Polyphenols are readily oxidised to quinones, which may react with aroma compounds and other must constituents, thereby diminishing aromatic intensity and clarity. Warmer conditions also favour the proliferation of spoilage microorganisms, such as acetic acid bacteria and certain non-

Saccharomyces yeasts, which can increase volatile acidity and promote undesirable sensory attributes. As a result, modern white winemaking increasingly prioritises techniques that limit oxygen exposure, reduce must temperature and stabilise microbial conditions from the earliest processing stages.

One promising strategy within this context is the use of selected non-

Saccharomyces yeasts for bioprotection. Although traditionally considered spoilage microorganisms, these yeasts have gained recognition over the past decade for their ability to enhance complexity, modulate fermentation and improve microbial stability [

35]. Bioprotection involves inoculating must with beneficial non-

Saccharomyces strains at pressing or shortly thereafter, enabling them to dominate the early fermentation environment, outcompete unwanted microorganisms and contribute metabolically to desirable aroma outcomes.

Among these species,

Metschnikowia pulcherrima has received considerable attention due to its enologically valuable traits: oxygen consumption, which reduces oxidative stress; production of pulcherrimin, an iron-chelating pigment that inhibits spoilage microbes; and β-glucosidase activity capable of hydrolysing glycosidically bound precursors to release free aromatic compounds [

36,

37]. In co-inoculation or sequential strategies with

Saccharomyces cerevisiae,

M. pulcherrima has been shown to modulate ester profiles—often enhancing fruity and floral notes—and to improve overall aromatic purity [

38,

39].

Bioprotection closely aligns with current objectives to reduce SO

2 use and implement more sustainable winemaking practices. Early colonisation by

M. pulcherrima can limit spoilage organisms, lower SO

2 requirements and protect vulnerable aroma compounds from oxidation [

40]. This may be particularly advantageous under warm-harvest conditions, where oxidative and microbial pressures are heightened. However, despite growing interest in non-

Saccharomyces yeasts, few studies have examined how bioprotection interacts with contrasting harvest-time temperatures.

This knowledge gap is especially relevant for Hárslevelű in Tokaj. While the general influence of harvest temperature on white wine aroma has been documented in other cultivars [

30,

33], systematic comparisons of night versus midday harvests of Hárslevelű under controlled vinification conditions are lacking. Likewise, although

M. pulcherrima has been investigated for bioprotection and aromatic enhancement in several white wine varieties, its combined effect with contrasting harvest temperatures remains insufficiently characterised [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Given Tokaj’s pronounced diurnal temperature shifts and its strategic emphasis on high-quality dry wines, clarifying these interactions is of both scientific and practical importance.

In this study, we examine how harvest timing and bioprotection jointly influence the volatile composition and sensory properties of Hárslevelű wines from the Tokaj region. Grapes were harvested either during cool pre-dawn hours (“night harvest”) or at midday under warm, sun-exposed conditions (“sun harvest”), and were processed under strictly controlled microvinification conditions to enable direct comparison of the resulting wines.

By integrating chemical, sensory and qualitative perspectives, this study aims to clarify how contrasting harvest temperatures and bioprotection with M. pulcherrima jointly shape the aromatic identity and gastronomic potential of Hárslevelű wines. More broadly, the findings contribute to ongoing discussions in Tokaj and other cool-climate regions on how harvest strategies and microbial management can serve as complementary tools to preserve varietal typicity, enhance freshness and meet the evolving expectations of both wine professionals and contemporary gastronomy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microvinification and Sampling

Hárslevelű grapes from the Tokaj wine region were used for the study, harvested on 5th September 2025 with totally healthy state. Harvesting was carried out twice on the same day at two distinct time points: “night”—at 4:00 a.m., when the temperature had not yet exceeded 18 °C, and “sun”—at 12:00 p.m., when the temperature was already above 28 °C. Grapes were hand-harvested from conventionally managed vineyards. In both cases, processing was performed immediately after harvest while maintaining the respective harvest temperature.

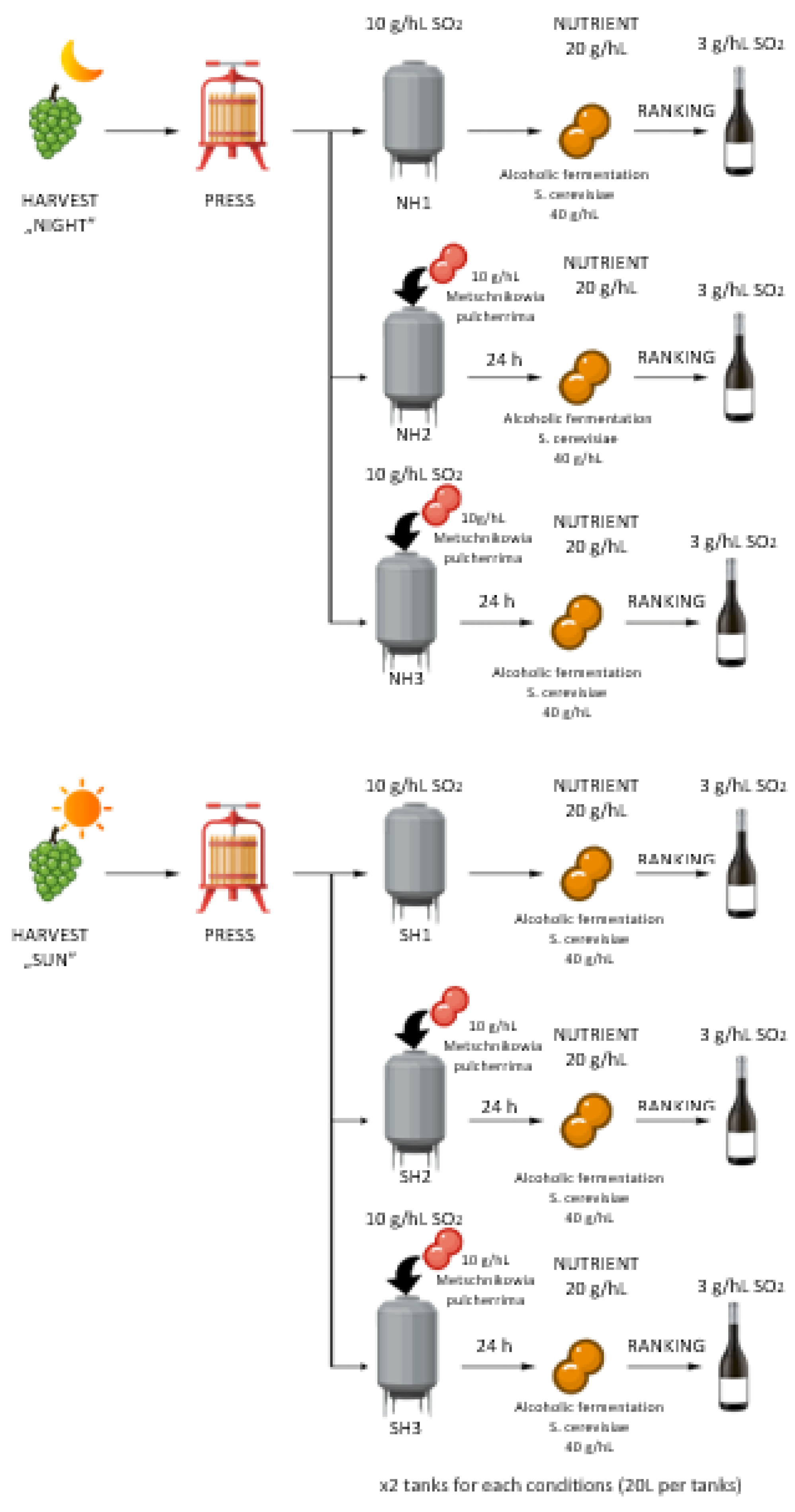

Vinification was conducted at Tokajbor-Bene Winery (Bodrogkeresztúr, Hungary). After destemming, grapes were pressed without prior crushing. Following sedimentation, the juice was divided into 20 L tanks, and the treatments described in

Figure 1 were applied in parallel (series a and b) for both the night and sun harvests.

The initial must composition was 195 g/L sugar, 9.2 g/L total titratable acidity, and pH 3.0. These parameters were determined using a WineScan™ 3 FT-IR analyser (FOSS Analytical, Hillerød, Denmark). The initial must parameters were determined using a WineScan™ 3 FT-IR analyser (FOSS Analytical, Hillerød, Denmark), yielding values of 195 g/L of total sugar, 9.2 g/L of total titratable acidity, and pH 3.0.

To enhance aromatic complexity and ensure microbiological stabilization, bioprotection was applied in the NH2, NH3, SH2, and SH3 treatments. Metschnikowia pulcherrima (EnartisFerm QMCK) was added directly after pressing at 10 g/hL. For alcoholic fermentation, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (EnartisFerm Aroma White) was used at 40 g/hL for samples NH1 and SH1, and—following a 24-h delay after the M. pulcherrima inoculation—for samples NH2, NH3, SH2, and SH3. This S. cerevisiae strain is selected for the production of fruity white wines from neutral or aromatic grape varieties. A nutrient and biological fermentation regulator composed of autolyzed yeast enriched in free amino acids and thiamine (Nutriferm® Arom Plus) was added at 20 g/hL in all treatments.

2.2. Analytical Characteristics, GC-MS Measurements, Sensory Panel

The following parameters were determined by classical analytical methods [

41] at the end of the fermentation. Alcohol content: OIV-MA-AS312-01A method; total acidity: OIV-MA-AS313-01 method; pH: OIV-MA-AS313-15 method; volatile acid: OIV-MA-AS313-02 method.

Analyses of reducing sugar, glycerol, gluconic acid, lactic acid, malic acid, and tartaric acid were performed every two days using a WineScan™ 3 FT-IR analyser (FOSS Analytical, Hillerød, Denmark).

Flavouring compounds were analysed by headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS). For each samples, 1 mL of wine was added to 4 mL of water together with 1 g of NaCl. 4-methyl-2-pentanol was used as internal standard. For the extraction of volatile compounds, DVB/CAR/PDMS 50/30 µm fibre was used. The extraction time from headspace was 30 min, and desorption in the injector was carried out at 250 °C for 0.9 min.

Measurements were performed using a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 Plus gas chromatograph equipped with an AOC-6000 autosampler (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) . Helium 5.0 (99.9990% purity) was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.11 mL/min. Separation was carried out on a 60.0 m × 0.25 mm × 0.50 µm ZB-WAXplus capillary column (Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA, USA). The oven temperature was initially set at 50 °C and held for 5 min, then increased to 230 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min. This temperature was maintained for 1 min, after which the oven was heated to 250 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min. The MS was operated in electron ionization mode at 70 eV in full-scan mode (m/z 35–300 at 3.0 scans/s). Both the ion source and interface temperatures were 250 °C. Shimadzu GCMSsolution software (version 2.53) was used to control the parameters of the GC-MS system, to search for components, to analyze the mass spectra, and to further evaluate the data and to perform a full comparison of the chromatograms. The identification of the chromatographic peaks, i.e., the resulting components, was performed using the NIST Mass Spectral Search Program (NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library, version 2.3, NIST 17) and Wiley FFNSC 2 Mass Spectral Library (Wiley, 2011 edition).

The detected aroma compounds have been grouped according to chemical structure and organoleptic profile. The NIST Chemistry WebBook (

https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/, accessed on 24 November 2025) was used for the chemical structure grouping, the Good Scents Company Database C (

https://www.thegoodscentscompany.com, accessed on 25 November 2025) was used for the sensory characteristics.

Wine sensory analysis was carried out by a panel composed of five panellists (non-professional ones, “trained assessors”) in the tasting room of University of Eger according to OIV standard, OIV-MA-AS312-01B (Sensory analysis of wine). The sensory booths were compliant with ISO standards, ISO 8589:2022 Sensory analysis—General guidance for the design of test rooms. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Samples of 30 mL were served to the judges in ISO 3591 tasting glasses (ISO 3591:1977—Sensory analysis—Apparatus—Wine-tasting glass. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1977) at 10 °C, with de-carbonated water and neutral bread as flavour-neutralisers. Before the judging started, the judges attended a training session in which they were trained to measure each sensory attribute using standard samples and shown how to use the scale for each attribute. The samples were tasted blindly and randomly according to codes. The sensory evaluation was carried out on a five-point scale, where 1 indicated the absence of the sensation and 5 represented extreme intensity. The visual evaluation focused on colour (from 1 — defensible to 5 — highly likeable). The olfactory evaluation included smell purity (from 1 — strong off-odours to 5 — clean), aroma purity (from 1 — strong off-notes to 5 — clean), flowery/citrus notes (from 1 - little to 5 - high) and honey/apricot notes (from 1 - very little to 5 - high). The taste evaluation considered acidity (from 1 — mild to 5 — vibrant, crips), and harmony (from 1 — disharmonious to 5 — elegant).The scores for each property were evaluated with the aid of a statistical programme.

2.3. In Depth Interviews

To complement the analytical and experimental results, qualitative insights were collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews, a well-established method for exploring expert perspectives, contextual knowledge and decision-making processes in gastronomy and wine research [

42]. This approach allowed the researcher to follow predefined thematic lines while maintaining sufficient flexibility for interviewees to elaborate on personal professional experiences.

All three participants were contacted in person, and each interview followed the same predefined set of five questions to ensure comparability across responses. Interviews were conducted individually, and answers were documented through detailed note-taking with the participants’ consent.

The interview guide consisted of the following core questions:

If you could freely select a wine style from the Tokaj portfolio—either a botrytised wine or a fresh, crisp, lighter style—and create a dish to pair with it, which would you choose and why? What type of dish would you recommend for that wine?

When considering food pairing, which characteristic plays a more decisive role for you in Tokaj wines: the aromatic profile or the residual sugar content?

What do traditional Tokaj winemaking practices represent for today’s generation of chefs?

In your view, do Tokaj wines have a future in international fine dining, and under what conditions could they succeed?

Do you think the current Tokaj wine portfolio meets the requirements of sustainable gastronomy? If yes or no, in what ways?

Three professionals representing different segments of the Hungarian fine-dining and gastronomic landscape participated in the study:

Máté Boldizsár, owner of the Michelin Green Star-awarded SALT restaurant in Budapest and featured in The World’s 50 Best Restaurants – Discovery, places sustainability at the centre of his culinary philosophy, emphasising reduced ecological footprint through local and organic sourcing. SALT’s three beverage-pairing concepts—natural wine selections, prestige pairings from classic European estates and non-alcoholic ferments including house-made juices, water kefirs and kombuchas—illustrate a modern, innovative approach to pairing in contemporary fine dining.

Gábor Horváth, founder of the culinary concept „aSÉFésaKERTÉSZ”, previously served for nearly a decade as chef of the Gusteau Culinary Experience Workshop in Mád, contributing to its transformation from a countryside restaurant into an award-winning fine-dining establishment. After gaining national recognition through publications and media work, he adopted an autonomous gastronomic path centred on seasonal organic vegetables and herbs grown in his own garden, integrating ecological production with creative cuisine.

Gergő Bajusz, owner of Első Mádi by BG in Mád, represents a hospitality tradition deeply rooted in the Tokaj region. His restaurant concept integrates regional identity, local ingredients and a wine-focused dining culture, reflecting a strong connection to the culinary and viticultural heritage of the area.

The insights obtained from these interviews provided meaningful interpretative depth, highlighting how chefs conceptualise Tokaj wine styles, sustainability considerations, culinary pairing strategies and the perceived international potential of Tokaj wines in modern fine dining.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Volatile compound data were evaluated by partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). The analysis was performed in the R statistical environment (R Core Team, version 4.4.1) using the

mixOmics and

ggplot2 packages [

43]. The X matrix consisted of the peak areas of the individual aroma compounds, while the categorical response variable (Y) encoded the experimental groups (night harvest - NH, sun harvest - SH). Non-numeric entries in the data set (e.g., “nd”) were treated as missing and replaced by zero prior to modelling. A two-component PLS-DA model was retained, and group separation was visualised using a PLS-DA biplot. In this biplot, points represent individual samples and arrows indicate the direction and relative contribution of the most influential aroma compounds (top 30 loadings) to the discrimination among groups.

Sensory data were imported from our table contained scores from the judgers and grouped according to the sample codes (NH1ab, NH2ab, NH3ab and SH1ab, SH2ab, SH3ab). Mean values for each sensory attribute were computed separately for each treatment and group. Radar charts were then created in the R statistical environment (R Core Team, version 4.4.1) with the fmsb package, visualising the comparative aroma profiles of NH and SH wines across the three treatments [

44].

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Harvest Time on Wine Aroma Profiles

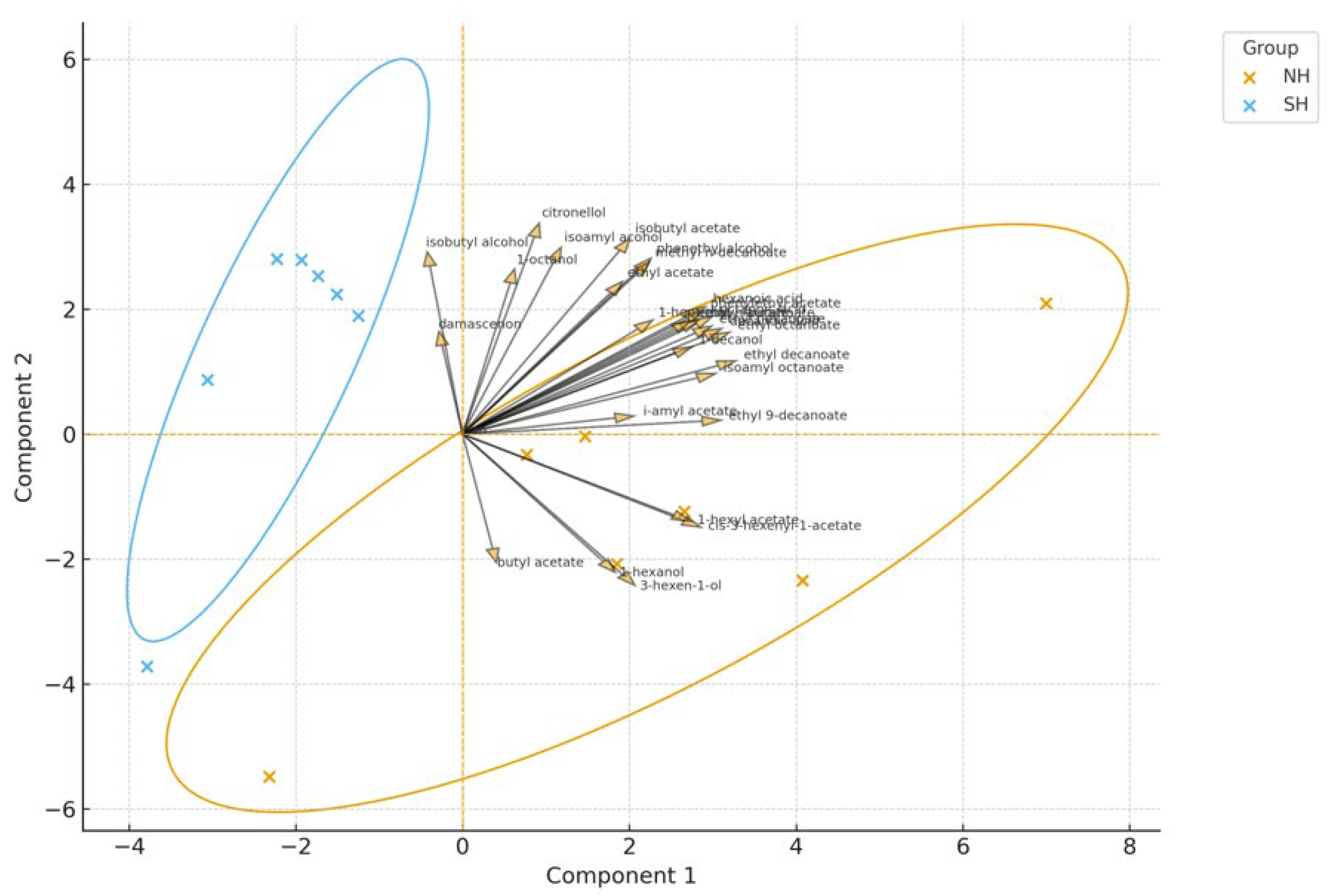

GC-MS analysis resulted in the detection of 29 aroma compounds. PLS-DA Biplot statistical modelling was performed to select the total detectable aroma components, the results of which are shown in

Figure 2.

The PLS-DA biplot revealed a clear separation between the night-harvested (NH) and sun-harvested (SH) wine groups, indicating that the contrasting harvest-time temperatures resulted in distinct volatile profiles. The first two latent variables captured the major discriminative structure of the dataset, and the score plot displayed minimal overlap between NH and SH samples, confirming consistent differences in aroma composition.

Within the NH group, the bioprotected samples (NH2, NH3) showed greater dispersion compared with the non-bioprotected control (NH1). This broader distribution reflects the enhanced metabolic diversity typically associated with M. pulcherrima. These samples exhibited higher loadings for compounds such as ethyl phenylacetate, ethyl butyrate, nerol, isobutyl alcohol and ethyl dodecanoate—volatiles known to contribute richer, waxier and more fruit-driven aromatic notes.

A similar pattern was observed in the SH group: bioprotected samples (SH2, SH3) were associated with a wider range of aroma-active metabolites, whereas SH1 remained more tightly clustered. Volatiles more strongly associated with the SH samples included ethyl isobutyrate, hexanoic acid, 3-methylpentanoic acid, linalool and β-damascenone, contributing to floral, citrus-like and riper aromatic characteristics.

Taken together, the PLS-DA model demonstrates that:

(i) NH and SH wines exhibit systematic differences in volatile composition;

(ii) bioprotection increases the diversity of characteristic aroma metabolites within each harvest group; and

(iii) the separation between groups is primarily driven by specific esters, higher alcohols and terpenes that distinguish the NH and SH wines.

3.2. Influence of Harvest Timing on the Sensory Profile of Wine

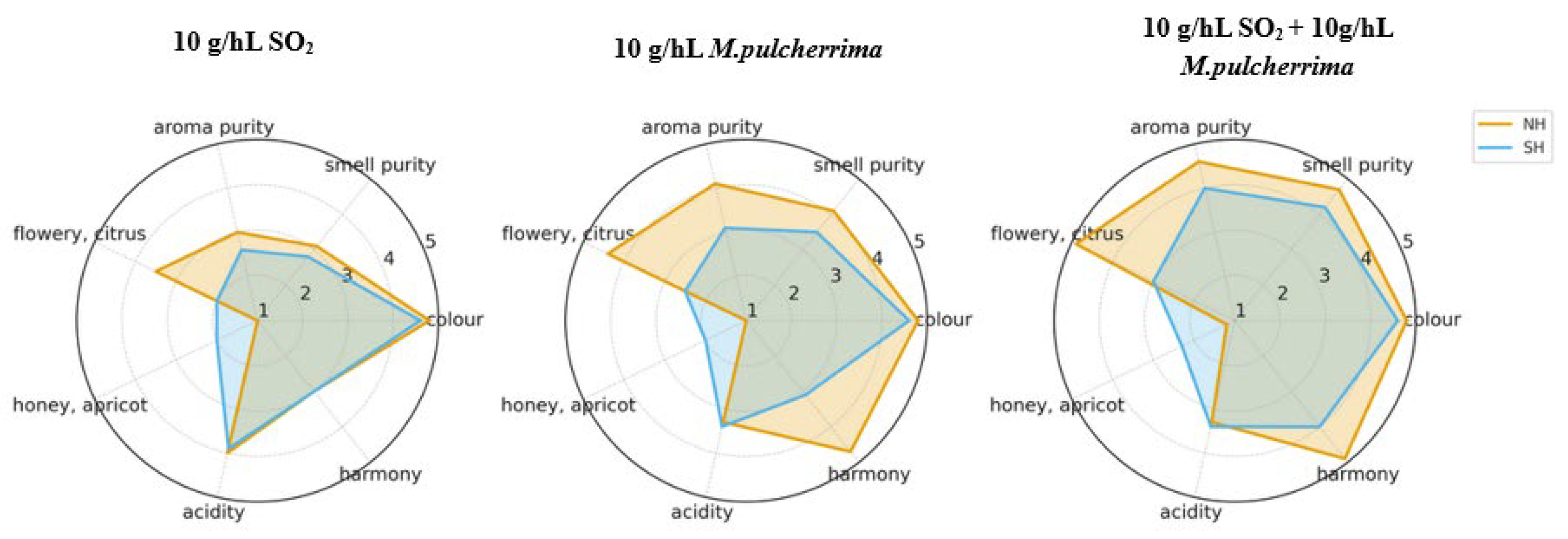

The results of the organoleptic evaluation are illustrated in

Figure 3 for night harvest and sun harvest according to the treatments.

Figure 3 provides a detailed comparison of the sensory profiles of night-harvested (NH) and sun-harvested (SH) wines produced under the three treatment conditions (10 g/hL SO

2, 10 g/hL

M. pulcherrima, and the combined SO

2 +

M. pulcherrima application). In the SO

2-only wines, NH samples displayed a notably cleaner and more vivid aromatic character, with higher scores for colour intensity, aroma purity, and flowery–citrus notes. By contrast, SH wines tended toward a slightly riper sensory expression, showing elevated acidity alongside more evident honey–apricot nuances.

The sensory distinction between NH and SH wines became more pronounced when M. pulcherrima was applied as a single treatment. NH wines in this group exhibited a consistently brighter and more refined aromatic profile, characterized by enhanced floral–citrus expression, improved aroma and smell purity, and a more integrated overall impression. SH wines, while maintaining acceptable aromatic quality, showed comparatively muted freshness and a greater presence of warm, ripe fruit attributes.

Under the combined SO2 + M. pulcherrima treatment, NH wines achieved the most favourable and well-rounded sensory evaluations across all attributes assessed. These wines were marked by exceptional clarity of aroma and smell, a strong and attractive colour appearance, and a notably harmonious overall balance. SH wines treated in the same manner demonstrated a solid sensory performance but continued to present higher perceived acidity and a stronger emphasis on honey–apricot notes, consistent with the trends observed in the other treatments.

Taken together, the results indicate that night harvesting systematically enhances the freshness, aromatic clarity, and overall sensory harmony of the wines, whereas sun harvesting accentuates acidity and promotes the development of riper, warmer aromatic notes. This pattern was evident across all treatment conditions, suggesting that harvest timing exerts a strong and consistent influence on the sensory expression of the resulting wines.

3.3. Qualitative Results: Thematic Synthesis of Chef Interviews

This section presents a thematic synthesis of the three in-depth interviews conducted with chefs representing different segments of Hungarian fine dining: Máté Boldizsár (SALT, Budapest), Gábor Horváth (aSÉFésaKERTÉSZ), and Gergő Bajusz (Első Mádi by BG). The analysis follows a question-by-question structure and summarises the responses without direct quotations.

i. Preferred Tokaj wine style (botrytised vs. fresh) and prospective dish pairing

All three chefs expressed openness to both fresh and botrytised Tokaj wine styles, although their preferred contexts differed.

Boldizsár emphasised a dual approach: fresh, often natural-style dry wines symbolise regional identity at SALT, whereas botrytised wines pair effectively with desserts or dishes incorporating fermented or mould-derived flavours.

Horváth favoured botrytised wines in colder seasons—particularly those with balanced sweetness and acidity—which he associated with warm, spice-forward dishes from Levantine or Southeast Asian cuisines.

Bajusz took a flexible position, noting that fresh wines suit everyday dining, while mature or sweet wines fit celebratory or contemplative occasions.

Overall, chefs attribute distinct culinary roles to the two styles: botrytised wines align with richer, spiced or dessert dishes, while fresh dry wines support lighter, mineral-driven pairings. Tokaj’s stylistic diversity is therefore regarded as an advantage in menu development.

ii. Dominant factor in food pairing: aromatic profile or residual sugar

All chefs acknowledged the relevance of both factors, though with different emphases.

Boldizsár viewed residual sugar as a structurally useful pairing tool but regarded aromatic structure as offering greater creative potential.

Horváth highlighted the situational importance of both acidity and residual sugar depending on a dish’s sequence within a menu.

Bajusz prioritised distinctive aromatic character, especially in relation to locally sourced, terroir-driven ingredients.

Across interviews, aromatic complexity emerged as the more intellectually defining component of pairing decisions, while residual sugar was perceived as a supportive structural element in specific contexts.

iii. Significance of Tokaj winemaking traditions for contemporary chefs

Perceptions of tradition varied across respondents.

Boldizsár noted that chefs rarely design dishes specifically to match traditional winemaking practices, suggesting limited direct influence on culinary decisions.

Horváth acknowledged the coexistence of Tokaj’s winemaking heritage with the region’s contemporary shift toward fresher, more vibrant dry styles.

Bajusz, working directly within the region, regarded Tokaj’s heritage as a cultural responsibility that should be reflected in local gastronomy.

Collectively, the chefs recognised Tokaj’s traditions as culturally and symbolically significant, though their impact on menu creation differs: for some they serve as inspiration, for others as a heritage component to be honoured.

iv. Future of Tokaj wines in international fine dining

All three chefs agreed that Tokaj wines hold strong international potential, though success depends on various conditions.

Boldizsár pointed to Tokaj’s existing representation on global wine lists and stressed that both sweet and dry styles can compete internationally when supported by consistent quality.

Horváth emphasised the necessity of more coordinated and strategic international marketing efforts.

Bajusz argued that global perceptions must move beyond classic pairings such as foie gras or blue cheese, advocating broader communication of Tokaj’s stylistic diversity.

Consensus emerged that Tokaj wines are well-suited for high-end gastronomy, with the primary barriers involving market visibility and entrenched stereotypes rather than wine quality.

v. Alignment of the Tokaj wine portfolio with sustainable gastronomy principles

Interviewees perceived meaningful progress toward sustainability in the region but also identified areas requiring improvement.

Boldizsár acknowledged increasing sustainability efforts, though noted that organic or low-impact viticulture is not yet widespread.

Horváth highlighted positive developments among younger producers, especially those transitioning toward organic or environmentally conscious practices.

Bajusz applied a structured evaluation—considering biowines, sustainable farming, fair trade, local sourcing and environmentally conscious packaging—and concluded that only a limited portion of Tokaj’s current portfolio meets all criteria.

Overall, chefs recognised that while sustainability initiatives are gaining momentum, the Tokaj region remains in transition. Broader adoption of sustainable vineyard and cellar practices is viewed as essential for aligning with contemporary gastronomic expectations.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that harvest-time temperature exerts a decisive influence on the volatile composition and sensory properties of Hárslevelű wines from the Tokaj region. Night harvesting consistently preserved a wider range of fresh, floral and citrus-associated aroma compounds, resulting in wines with greater aromatic purity, balance and overall harmony. In contrast, grapes harvested at midday under higher temperatures produced wines with riper aromatic characteristics, more pronounced acidity perception and a less clearly defined expression of freshness.

Bioprotection with M. pulcherrima enhanced the diversity of fermentation-derived esters and higher alcohols and improved overall aromatic clarity; however, it did not override the fundamental differences imposed by harvest-time microclimate. Instead, it acted as a complementary tool, amplifying the favourable effects of cooler harvest conditions while maintaining the harvest-temperature-driven typicity of each wine group.

From a consumer-oriented perspective, these findings are particularly relevant. Contemporary wine drinkers tend to favour styles characterised by freshness, purity and clearly articulated fruit expression. Among the wine styles examined, those derived from night harvesting aligned most closely with this consumer-friendly sensory profile, offering greater coherence and ease of interpretation.

Overall, night harvesting—particularly when combined with bioprotection—emerges as an effective strategy for maintaining varietal typicity, enhancing aromatic precision and producing dry Tokaj wines that meet both professional and consumer expectations. More broadly, this approach supports the principles of sustainable gastronomy by reducing the need for chemical additives, lowering technological intervention and preserving sensory freshness under increasingly warm harvest conditions. As climate change continues to alter ripening-period temperature patterns, the coordinated use of harvest strategy and microbial management will become increasingly essential for safeguarding the aromatic identity, consumer appeal and gastronomic relevance of Tokaj wines.