“When the values successively attributed to the same variable approach indefinitely a fixed value, so as to end up by differing from it by as little as one could wish, this last is called the limit of all the others.”

— Augustin–Louis Cauchy (1789–1857)

1. Introduction

1.1. Real-Valued Sequences and Convergence

Real-valued sequences remain one of the most basic but versatile objects in analysis. Classical mathematical literature emphasize the

–

N definition of convergence, the derived notions of limit inferior and limit superior, and the extension of limits to the extended real line

[

1]. These tools give a robust qualitative classification of limit behaviour—convergent, divergent to

, or oscillatory—and they underpin the standard partition of

into convergent and various divergent subclasses [

2]. At the same time, the classical framework deliberately abstracts away

when a sequence enters a prescribed error band around its limit and focuses instead on the asymptotic fact that such an entry eventually occurs.

Beyond this qualitative viewpoint, several quantitative refinements have been developed. Constructive and computable analysis introduce

moduli of convergence or

Cauchy moduli, functions

that witness how far into the sequence one must go in order to guarantee an

-accurate approximation of the limit [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Numerical analysis, in turn, describes the speed of convergence of iterative processes via rates and orders of convergence (e.g., “linear,” “superlinear,” or “quadratic” order), capturing how successive errors compare to each other rather than to a fixed

-tube [

7,

8,

9]. These perspectives illustrate that quantitative information about convergence is both mathematically rich and practically important.

1.2. Motivation

The present paper is motivated by a parallel line of work on

radii of continuity for real-valued functions, where one assigns to each point

and tolerance

a maximal radius within which the function oscillation around

stays below

[

10]. Such radii encode local stability of functions in the metric space

and lead to a fine-grained description of continuity that interacts naturally with algebraic operations and with classical moduli of continuity. From this vantage point, it is natural to ask whether an analogous “radial” description can be developed for sequences in

, with the index

n playing the role of a one-dimensional “space” variable along the tail of the sequence.

In classical analysis, the phrase “radius of convergence” appears almost exclusively in the context of power series, where one studies the largest spatial radius

such that the series

converges whenever

and diverges whenever

[

1]. This notion is attached to analytic functions in the complex plane rather than to bare sequences [

11]; it is a geometric property of where a series converges, not of how quickly its coefficients or partial sums stabilize. By contrast, the moduli of convergence mentioned above provide index-based information for sequences but are rarely organized or studied through an explicit “radius” vocabulary. Thus, there is a conceptual gap between geometric radii in function spaces and quantitative convergence data in sequence spaces. The goal of this paper is to bridge this gap by introducing and systematically studying

radii of convergence for real-valued sequences within the context of constructive mathematical analysis [

3,

4,

5].

1.3. Organization of the Paper

This paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 we provide the necessary mathematical background for the subsequent sections. In

Section 3 we introduce the notion of a radius of convergence for sequences, beginning with one-sided liminf and limsup radii and then extending the discussion to the two-sided radius of convergence, the geometric radius, and the Cauchy radius. We then study the stability of these radii under algebraic operations on sequences. Next, in

Section 4 we present examples of computing the radius of convergence for two clusters of sequences: four convergent sequences and four divergent sequences with infinite limits. We conclude the paper with a brief discussion in

Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

In this subsection we collect the basic notation and standard facts about real-valued sequences that will be used throughout the paper.

Definition 2.1 (Sequence space ). We denote by the space of all real-valued sequences equipped with pointwise addition and scalar multiplication.

Definition 2.2 (Limit inferior, limit superior, limit profile and limit). Let . The limit inferior and limit superior of a are defined by and where in which The pair is referred as limit profile of When , we write and say that a is convergent.

Lemma 2.3 (Tail characterization of lim inf and lim sup)

. Let , and let be the tail infimum and tail supremum defined by and respectively. Then is increasing, is decreasing, and

In particular, if and only if the monotone sequences and converge to finite real limits.

Definition 2.4 (Cauchy sequence). A sequence is called Cauchy if for every there exists such that

Theorem 2.5 (Cauchy Equivalency Criteria). In the complete space , every Cauchy sequence is convergent, and conversely every convergent sequence is Cauchy.

Theorem 2.6 (Seven-block partition of

by lim inf and lim sup)

. For each let be its limit inferior and limit superior. Define

Then the seven sets are pairwise disjoint and

In particular, every real-valued sequence belongs to exactly one of the blocks , according to the qualitative behaviour of its limit inferior and limit superior (unbounded on both sides, bounded but non-convergent, one-sided unbounded, diverging to or , or convergent) [2].

Lemma 2.7 (Infimum of an intersection)

. Let be nonempty sets with the following tail property:

Then:

(i)There exist integers such that and

(ii)

Lemma 2.8 (Asymptotic inversion of

)

. Let be a variable and put . Then, as ,

3. Theory of Radius of Convergence for Sequences

Write a paragraph and tell the readers what you are going to talk about.

3.1. One-Sided Liminf and Limsup Radii for a Single Sequence

We start our investigation by focusing on the limit profile of a given sequence and its associated radii, and their potential relationship:

Definition 3.1 (Liminf and limsup radii). Let be a real sequence with associated tail infimum and tail supremum and let .

(i) We define the

liminf radius of

a at level

by:

(ii) We define the

limsup radius of

a at level

by:

(iii) We refer to the pair as the radii profile of the sequence

Remark 3.2 By the standard properties of lim inf and lim sup, the sets are non-empty for every , hence the corresponding radii are finite integers.

Remark 3.3 As a direct result of Definition 3.1 and Theorem 2.6, there are seven different methods for the computation of radii profile given the limit profile.

Theorem 3.4 (Relations between liminf and limsup radii when the two–sided limit exists). Let be a sequence with associated limit profile and radii profile . Assume Then:

If , then for every ,

If , then in general there is no universal inequality between these radii and for given each of the three orderings can occur (see the proof for explicit examples).

If , then for every ,

Proof. By Lemma 2.3 the tail infimum and tail supremum satisfy for all N, with increasing and decreasing. We treat the three cases separately.

(1) Case . Here , and by Definition 3.1 it yields that if , then for all , hence for all , so . Thus and taking infimum from both sides it follows that .

To see that the inequality can be strict, take . Then and , so and . Consequently,

(2) Case . Then We now show that no universal inequality between and holds in this case, by providing convergent sequences that realize all three orderings for a fixed .

First, define

Then

. Every tail contains zeros, so

for all

N, whence

and

. On the other hand,

, so there exists a least

with

for all

, giving

. Thus

Second, define

Again

. Every tail contains zeros and negative spikes, so

for all

N, and hence

and

. The tail infima satisfy

, so there exists a least

with

for all

, and thus

. Hence

Finally, for the constant sequence

we have

for all

N, so

and

. These three examples show that all three orderings between

and

can occur.

(3) Case . Here , and by Definition 3.1 it yields that if , then for all , hence for all , so . Thus and taking infimum on both sides, it follows that .

To see that the inequality can be strict, take . Then and , so and , and hence

This completes the proof. □

Conjecture 3.5 (Limit profile vs. Radii profile)

. Let

be a sequence with associated limit profile

and radii profile

. Then:

Counterexamples. We present two counterexamples each for one direction of implication (

11):

(a) :

Let

be defined by

Then

and

. Next, for any

and

we have

and

Consequently:

(b) :

Let

be defined by

Then

and

. On the other hand, for given

Roughly speaking, there is no simple characterization beyond such tail-level regularity.

3.2. Two-Sided Radius of Convergence and Cauchy Radius

We continue our investigation by focusing on the two-sided radius of convergence, the Cauchy (uniform) radius of a given sequence , their potential relationship with each other and to the one-sided radii:

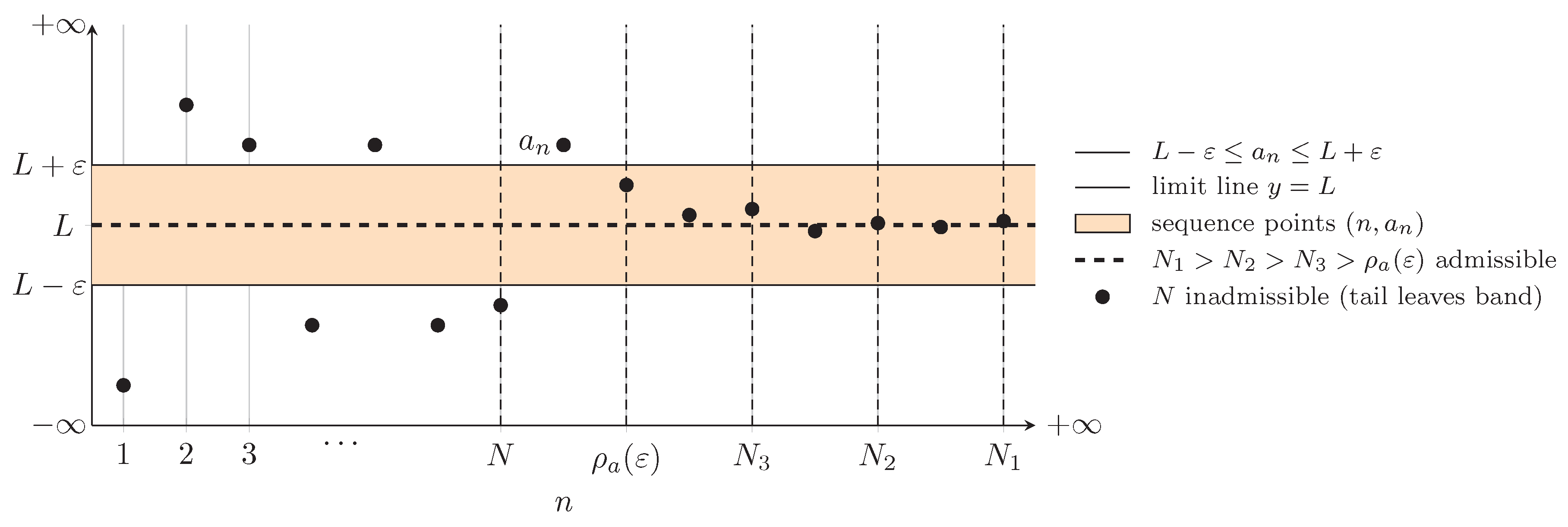

Definition 3.6 (Radius of convergence of a convergent sequence)

. Let

be a convergent real sequence with limit

. For

we define the

radius of convergence of

a at level

by:

Thus

is the smallest index after which the entire tail of

a remains within the

–tube around its limit

L (

Figure 1).

Remark 3.7 Given the convergent sequences a, we may view and from Definition 3.1 as one-sided radii relative to the common limit , while in Definition 3.6 is the two-sided radius.

Definition 3.8 (Geometric radius)

. To emphasize the analogy with classical notions of radius (such as the radius of a ball in a metric space or the radius of convergence of a power series), one may equivalently work with the rescaled radius:

with the convention

(

Figure 2).

Remark 3.9 The transformation

is strictly decreasing on

and invertible via

so

and

encode exactly the same information about the convergence speed of

a. In particular, larger values of

correspond to smaller entry indices

, so that

behaves qualitatively like a geometric radius around the limiting point(

Figure 2).

Theorem 3.10 (Block-wise two-sided radius of convergence). Let belong to one of the seven blocks of Theorem 2.6, and let be the two-sided radius of convergence of a at level (Definition 3.6). Then is well defined and finite for every if and only if ; for the two-sided radius is not defined, and on the convergent blocks we have that is nonincreasing on G and nondecreasing on .

Proof. By Definition 3.6 the quantity

is defined only when

a converges in

to a limit

, and then

By Definition 2.2 and Theorem 2.6, the sequence

a has an extended limit

if and only if

, i.e. if and only if

a lies in one of the convergent blocks

; on the divergent blocks

we have

, so no extended limit exists and

is left undefined there.

If

, then

and, for

,

whence

, so

is nonincreasing on

G.

If

(so

), then for

we have

so

, i.e.

is nondecreasing on

E. The case

with

is analogous, using the sets

, and yields the same monotonicity conclusion. Collecting the block-wise information gives

Table 1. □

Definition 3.11 (Cauchy radius)

. Let

be a real sequence and

. We define the

Cauchy radius of

a at level

by:

Remark 3.12 As the direct result of Definition 3.11 and Theorem 2.5:

Theorem 3.13 (Two–sided radius via liminf / limsup radii)

. Let and suppose its extended limit exists, i.e. . For let be as in Definitions 3.1 and 3.6. Then:

Proof. First, we proof the equality (

21). We distinguish the cases

,

, and

.

(a) Finite limit . If , then for every we have for all , hence , so and . Thus . Conversely, if , then for each , so and . Accordingly, .

(b) Infinite limit . Here, for any n we have iff for all . Hence . Moreover, implies , so .

(c) Infinite limit . This case is analogous to (b) with all inequalities reversed; again one obtains .

Second, we prove equality (

21). In all three cases the sets

,

,

are nonempty tails of

. By Lemma 2.7:

This completes the proof. □

Theorem 3.14 (Comparison of two–sided and Cauchy radii)

. Let be a convergent real sequence with limit , two–sided radius and Cauchy radius . Then, for every and every we have:

Proof. Fix

and

, and let

. Then for every

we have

and

. If

, the triangle inequality gives

so

. This proves the set inclusion:

Since

and

are tail sets in

, by an application of Lemma 2.7 on inequality (

24) we have:

This completes the proof. □

Corollary 3.15

Under the assumptions of the Theorem 3.14, for every we have:

Remark 3.16 The inequality (

23) in Theorem 3.14 (or inequality (

25) in Corollary 3.15) can be strict. As an example, consider the sequence

An straightforward calculation shows that:

for all

Take,

Then,

3.3. Stability Under Algebraic Operations

We now collect the main structural properties of the radius of convergence, in terms of its assigned sequence a and other features as follows:

Theorem 3.17 (Stability of the radius of convergence). Let and be convergent real sequences with finite limits and , respectively. Denote by , their radii of convergence in the sense of Definition 3.6. Then the following assertions hold:

- (i)

Monotonicity and characterization of convergence. For every ,

- (ii)

Tail invariance under finite modification. If is a sequence with for all for some , then c converges to and

- (iii)

Affine transformations. Let and , and define . Then and

- (iv)

Sums. Define and . Then, and

- (v)

-

Products. Define (Hadamard Product) and . For set

- (vi)

Quotients. Let and be convergent real sequences with finite limits and . Define and Then and, for every ,

Proof. (i) If , then by definition. Now, taking infimum from both sides it follows that .

(ii) If

for all

and

, then clearly

. Moreover, by Definition 3.6,

Hence,

, and taking infima gives

Since

, we conclude

(iii) For

and

we have

Thus

if and only if

, and the stated identity for

follows by taking infima over

N.

(iv) Fix

and put

for

. If

, then we have

and

respectively. Hence

This shows that

and therefore

, as claimed.

(v) Fix

and define

as in the statement. Let

. Then for every

we have

In particular

for all

, and we may write

Hence, for

,

using

in the third line and the definition of

in the last line. Thus

and the claimed inequality for

follows.

(vi) Fix

. Since

, there exists

such that

implies

. For such

n, we can write

Hence a sufficient condition for

is that both:

Let

and

. By Definition 2.13, for all

we have

, and for all

we have

. Therefore, for all

, inequalities (

32) hold and consequently

. Hence

, and taking infima gives

which proves (

31).

This completes the proof. □

Remark 3.18 The inequalities (

29)- (

31) in Theorem 3.17 can be strict. As examples, it is sufficient to consider the following examples:

For the

sum case, take

and

, so

and hence

. Solving

gives

whenever

, so for any

with

we have

. Because

is constant,

for every

. Thus

for such

, so inequality (

29) is strict.

For the

product case, take

and

, so

and

. From

we get

when

, and from

we obtain

in the same generic case. For (26), with

and

chosen so that

, both radii satisfy

and

, hence

. Since

gives

, we have

for these

, so (

30) is strict.

For the

quotient case, take

, so

and

. As in the previous example, solving

yields

whenever

. In (

31) the inner radius is

, so for

with

we get

. Because

gives

, we obtain

for such

, showing that inequality (

31) is strict.

4. Examples and Explicit Computations

We present the calculation of radius of convergence for several key classical sequences as follows:

4.1. Radii of Convergence for Classical Convergent Sequences

Example 4.1 (

). Let

be given by

Then

. For

we have

, and the elementary estimate

for

yields

The function

is strictly decreasing on

with

. Hence for every sufficiently small

there exists a unique real number

such that

, and for all integers

we have

. In particular,

implying:

Using the expansion

as

, we have

so solving

yields the well-known asymptotic profile

and therefore

Example 4.2 (

). Let

be given by

It is classical that

, hence

. For

we have

With

this yields

Exponentiating and using

we obtain

where we used

for

in the last step. Hence for every

and every integer

we have

for all

. In the notation of Definition 3.6, we have

implying:

Moreover, from the classical expansion

we infer the asymptotic profile

Example 4.3 (Fibonacci ratios

)

. Let

be the Fibonacci numbers and consider

Using Binet’s formula [

12]:

we obtain

Since

, the ratios converge to

and

Taking absolute values and using

gives

Thus, for any

, every integer

satisfies

for all

. Consequently

because

. Since (

42) shows

, we obtain the logarithmic asymptotic

Example 4.4 (Leibniz partial sums for

)

. Define the sequence of partial sums of the Leibniz series by

Then

as

. Since this is an alternating series with monotonically decreasing terms

, the alternating series test yields the sharp remainder bound

and the right-hand side is strictly decreasing in

n. Consequently, for

we have

Solving the inequality

gives

, that is,

Therefore the radius of convergence of

at level

is

and in particular

4.2. Radii of Convergence for Classical Divergent Sequences

Example 4.5 (Geometric progression

)

. Let

be defined by

Then

, so

in Definition 3.6. Since

is strictly increasing, for any

the condition

is equivalent to

. Hence

Solving

for

N gives

, so the smallest admissible index is

In particular,

where “∼” denotes asymptotic equivalence, not an algebraic equality.

Example 4.6 (The Fibonacci sequence

)

. Let

be the Fibonacci numbers with

,

and

, and define

Then

, so

. By Binet’s formula,

and since

we have for all

Because

is strictly increasing, the set

is

For

the lower bound in (

55) implies that every

N with

is admissible. Equivalently,

and therefore

Conversely, from the upper bound in (

55) we obtain, for

,

whence

Thus for sufficiently large

,

Both bounds in (

61) are asymptotic to

, so

again in the asymptotic sense only.

Example 4.7 (The prime numbers

)

. Let

denote the

n-th prime and set

Then

, so

and

Hence

equals the number of primes not exceeding

, plus one. Let

be the prime counting function. Then

By the prime number theorem (PNT) [

13],

and (

65) is

equivalent to the well–known asymptotic

for the

n-th prime. Substituting

into (

65) and using (

64) yields

Note that (

66) is a

consequence of the PNT and its standard asymptotic inversion, not an exact algebraic formula.

Example 4.8 (Factorials

)

. Let

be given by

Then

, so

and, as in the previous examples,

Thus

is the smallest

N with

. To understand its growth, we use Stirling’s formula

which implies

Set

and write heuristically

. Taking logarithms and using (

69), we obtain

Equation (

70) is an

asymptotic relation of the form

, and its inversion must therefore be understood in the asymptotic sense of Lemma 2.8, not as an exact algebraic division. Applying Lemma 2.8 with

and

yields

Thus the radius function for the factorial sequence has the standard inverse–

growth: it is “almost logarithmic’’ in

, with a

correction in the denominator. The exact inverse of

can be written using the Lambert

W–function, but only the leading asymptotics are needed here.

Table 2 presents the summary of radius of convergence of above sequences for the asymptotic cases:

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Radius-of-Convergence Viewpoint in

In this paper we proposed a radius–of–convergence viewpoint for real sequences that complements the classical limit–based description. Starting from the liminf/limsup profile , we introduced the one–sided liminf and limsup radii and , the two–sided radius of convergence , the rescaled geometric radius , and the Cauchy radius . These constructions provide quantitative thresholds for entering an –tube either around the limit interval or around the circular area in , and they remain meaningful for finite and infinite limits alike. We established basic structural properties (monotonicity in , block–wise behavior across the seven–block partition, and stability under algebraic operations such as sums, scalar multiples, and products) and illustrated them on eight representative examples from convergent and –divergent clusters. Altogether, the radii offer a unified language to compare how fast different sequences converge, diverge, or oscillate inside the global space .

5.2. Relation to Classical Cauchy Convergence and Theory

The new radii are tightly linked to standard tools such as Cauchy convergence and the framework. For sequences with , the one–sided radii coincide and the two–sided radius is comparable to the Cauchy radius , so that the finiteness of these radii for every recovers the usual Cauchy criterion. For general sequences, the liminf and limsup radii encode how quickly the tails approach the lower and upper envelope of the limit set, and our comparison results show how is controlled by and , with explicit examples where the corresponding inequalities are sharp or strict. In this way, the radius–of–convergence viewpoint refines the qualitative information carried by lim inf and lim sup into a quantitative scale that still respects the classical Cauchy/limit dichotomy.

5.3. Future Work

The present study suggests several directions for further investigation. First, it would be natural to develop radii for transformed sequences and associated series, for example under linear filters, Cesàro means, discrete differentiation, or when passing from to the partial sums , and to compare these radii with classical notions of convergence acceleration. Second, the interaction between the radii and the seven–block classification, together with the underlying graph structures on blocks, deserves a more systematic analysis; this includes tracking how radii behave along edges of the block graph and identifying “radius–preserving’’ or “radius–contracting’’ transitions between blocks. Third, it would be interesting to extend the framework beyond real sequences, for instance to vector–valued sequences in normed spaces and to random sequences, where one could study Cauchy and convergence radii in almost sure, in–probability, or senses. We hope that these extensions will further clarify how radius–based descriptors fit into the broader landscape of convergence theory.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rudin, W. (1976). Principles of mathematical analysis (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw–Hill.

- Soltanifar, M. A classification of elements of sequence space Seq(R). Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, E. Foundations of constructive analysis; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, E.; Bridges, D. S. Constructive analysis; Springer–Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troelstra, A. S., & van Dalen, D. (1988). Constructivism in mathematics: An introduction (Vols. 1–2). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland / Elsevier.

- Weihrauch, K. Computable analysis: An introduction; Springer–Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, R. L.; Faires, J. D. Numerical analysis, 9th ed.; Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chasnov, J. R. Numerical methods for engineers [Lecture notes]. Hong Kong, China: Department of Mathematics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. 2020. Available online: https://www.math.hkust.edu.hk/~machas/numerical-methods-for-engineers.pdf.

- Rate of convergence. (2014). In Encyclopedia of Mathematics. European Mathematical Society. Retrieved from http://encyclopediaofmath.org/wiki/Rate_of_convergence.

- Soltanifar, M. An atlas of epsilon-delta continuity proofs in function space F(R, R). Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfors, L. V. Complex analysis: An introduction to the theory of analytic functions of one complex variable, 3rd ed.; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth, D. E. (1997). The art of computer programming: Vol. 1. Fundamental algorithms (3rd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley.

- Ingham, A. E. The distribution of prime numbers; (Original work published 1932); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).