Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

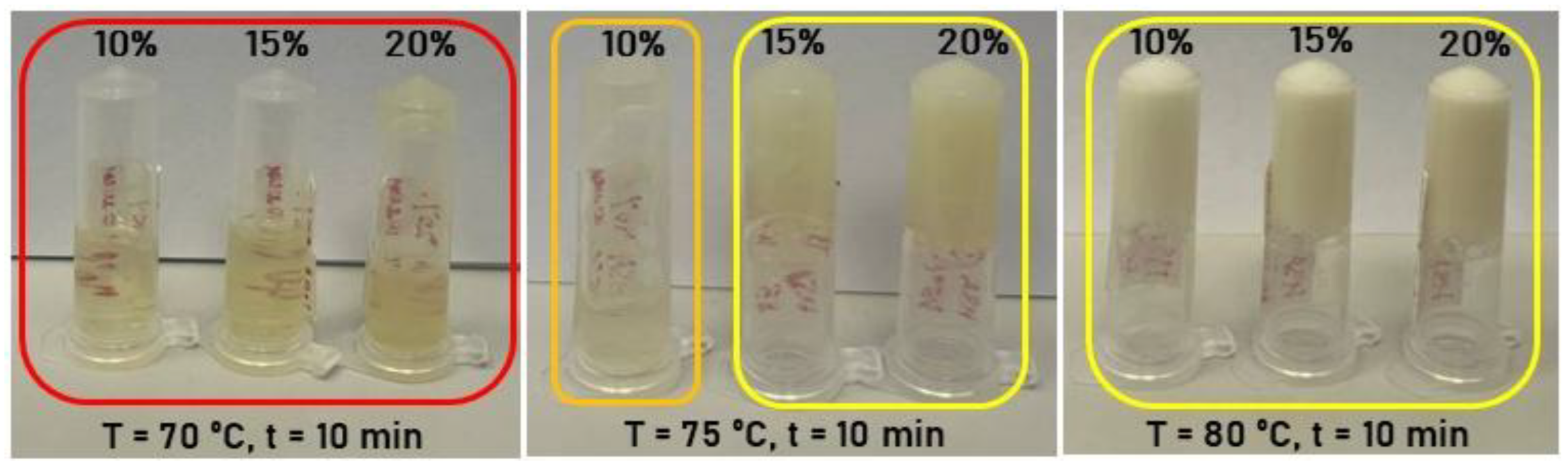

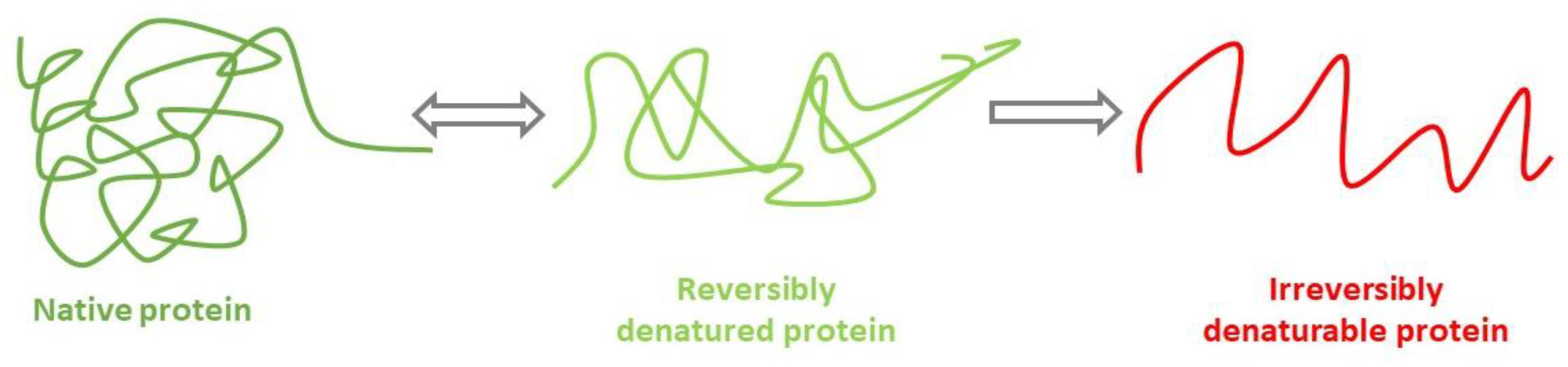

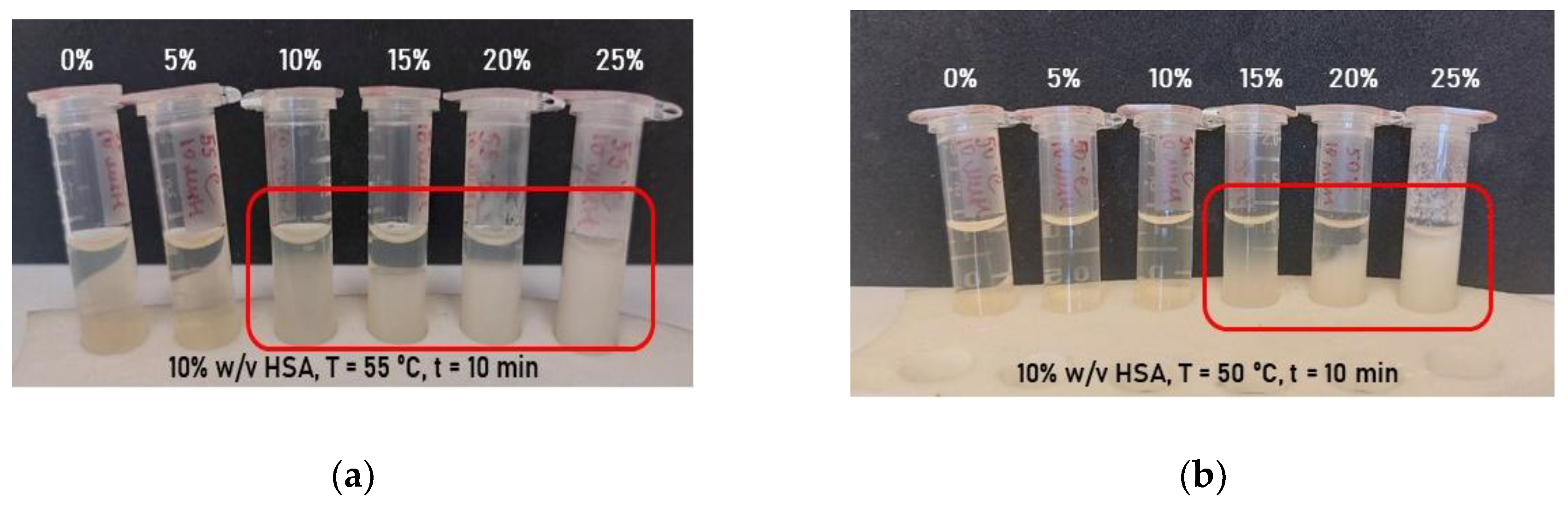

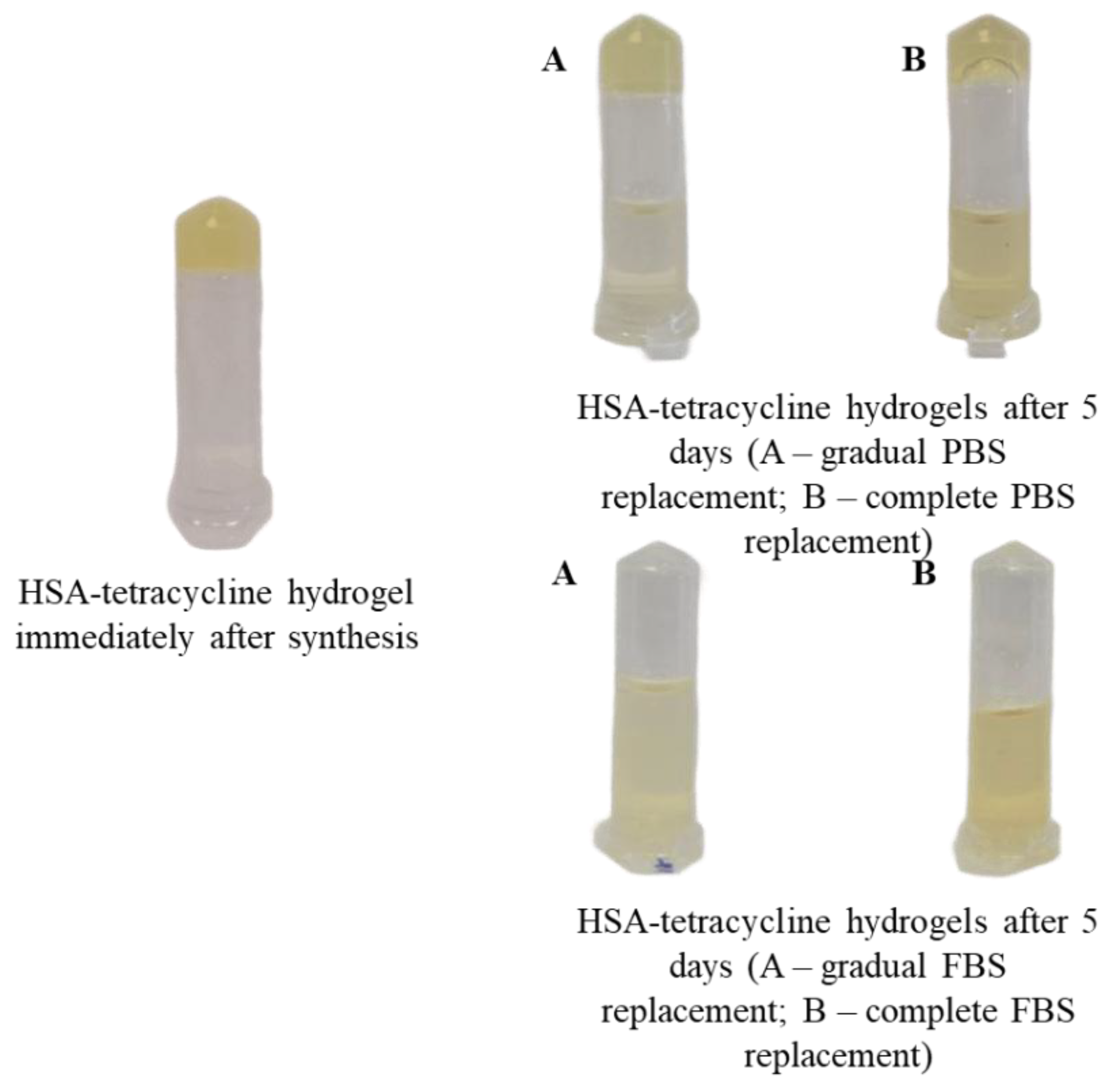

2.1. Effect of Synthesis Conditions on Human Serum Albumin-Based Hydrogel Formation

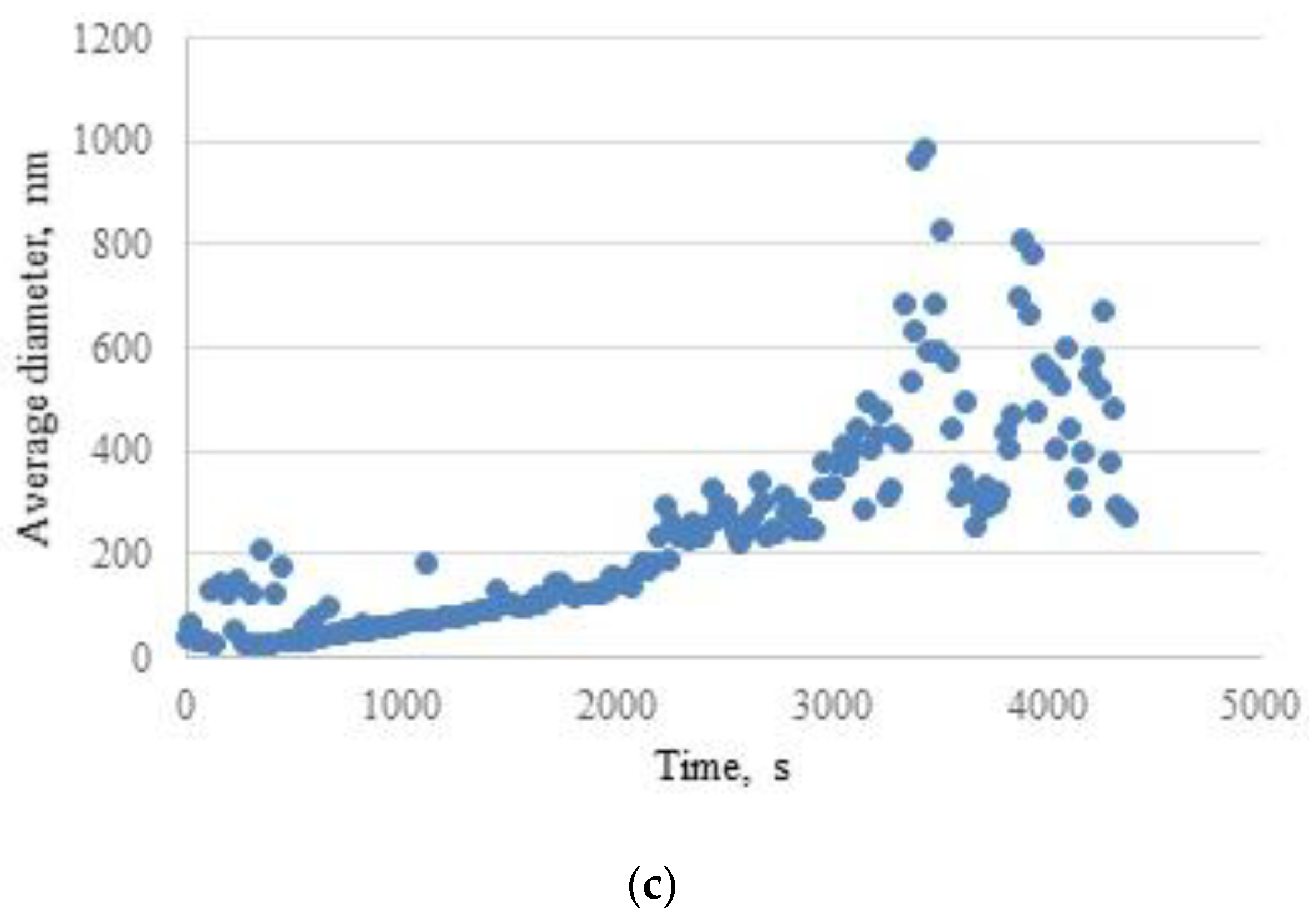

2.2. Investigation of Hydrogel Gelation Kinetics via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

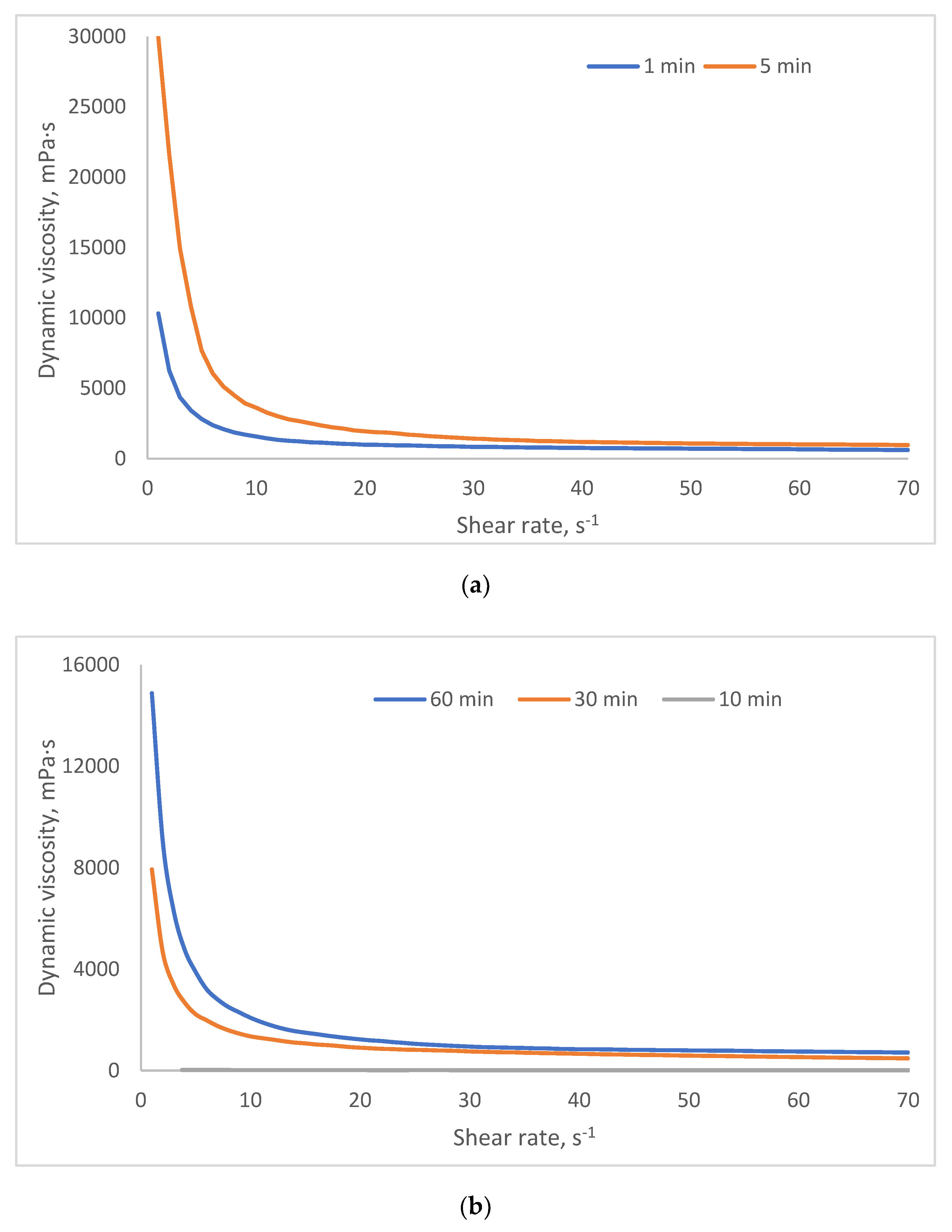

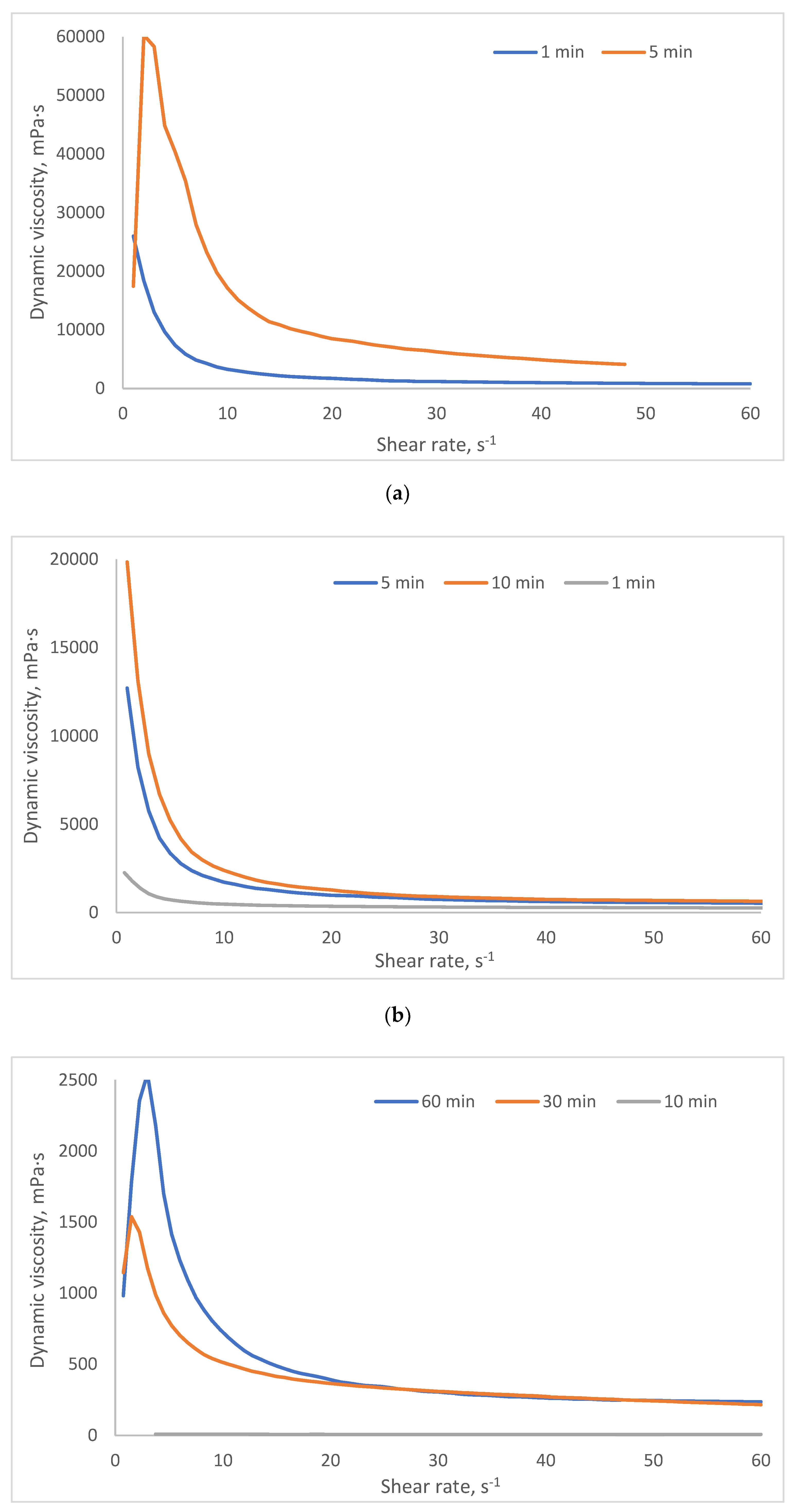

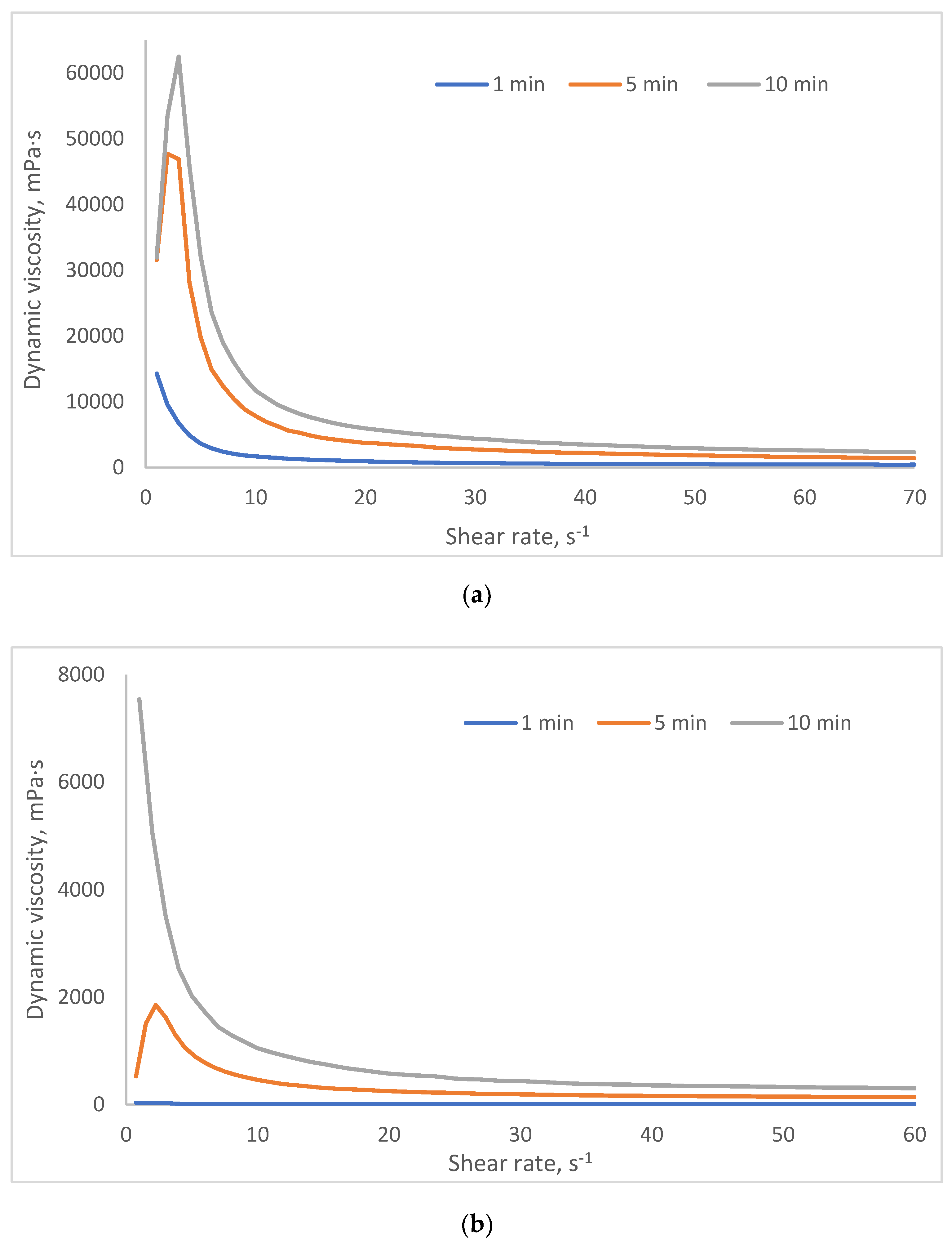

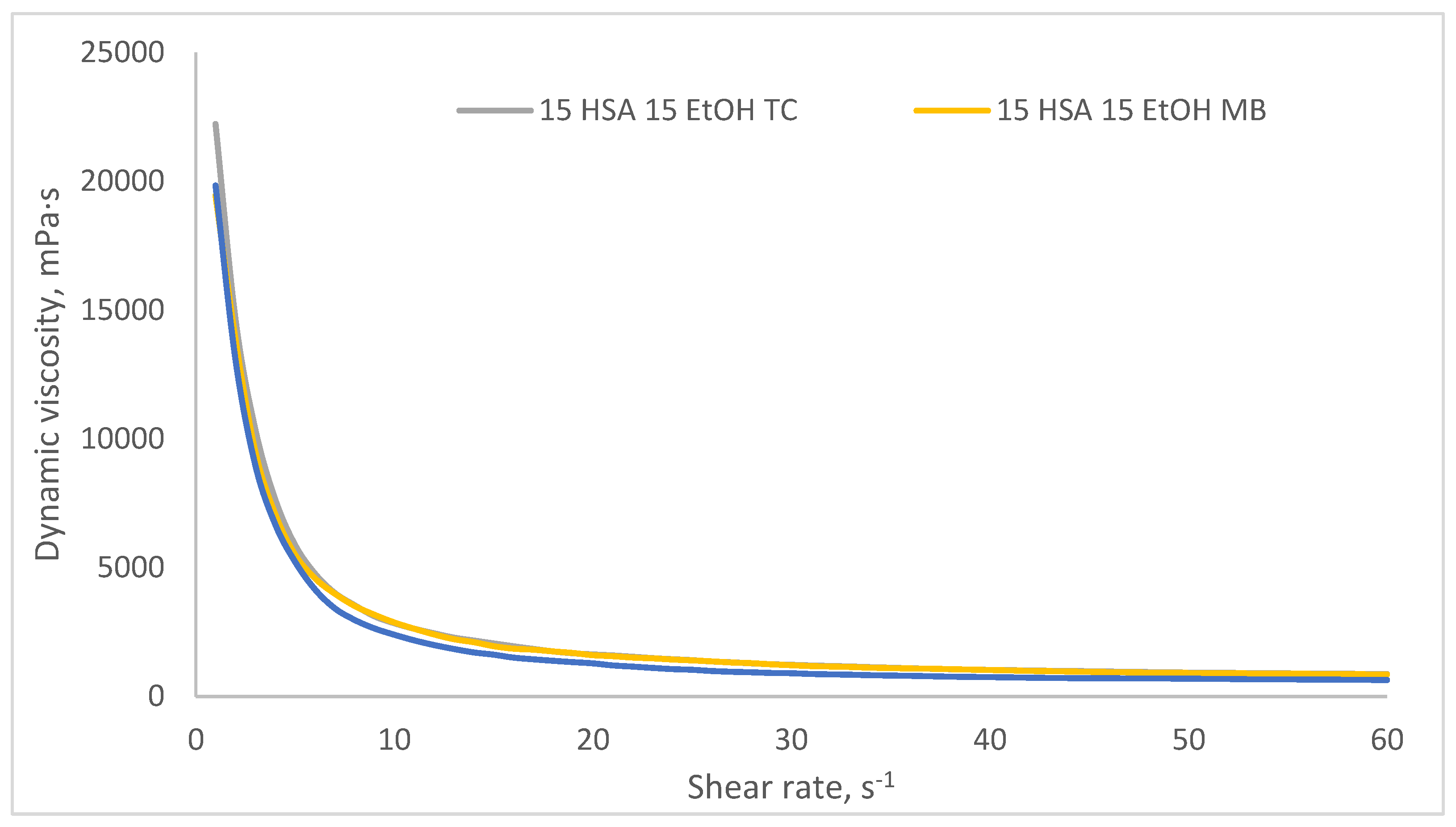

2.3. Investigation of Rheological Properties of HSA-Based Hydrogels

- Group 1 (viscosity: 100–1000 mPa·s at 3 s⁻¹) includes formulations with lower HSA and ethanol concentrations (e.g., 10% HSA with 10–15% EtOH, incubated 30–60 min). These systems demonstrate low resistance to flow and are perfect candidates for minimally invasive delivery, aligning with viscosity thresholds reported for injectable hydrogels in the literature [45,46].

- Group 2 (1000–5000 mPa·s at 3 s⁻¹) encompasses moderately crosslinked systems, such as 15% HSA with 10–15% EtOH or 20% HSA with 10–15% EtOH (short incubation times). These hydrogels retain injectability while offering enhanced mechanical stability post-injection, making them suitable for sustained release applications.

- Group 3 (5000–10,000 mPa·s at 3 s⁻¹) includes formulations with higher protein content and intermediate ethanol concentrations (e.g., 15–20% HSA with 15–20% EtOH, 5–10 min incubation). Their elevated viscosity suggests potential use as structural scaffolds or depot-forming carriers for prolonged therapeutic action, though injection may require larger-bore needles or pre-warming to reduce viscosity.

- Group 4 (10,000–25,000 mPa·s at 3 s⁻¹) comprises systems with high ethanol content (20% EtOH) and moderate HSA concentrations (10–15%). Notably, while some samples in this group exhibited extremely high viscosities (e.g., 10 HSA–20 EtOH at 10 min: ~32,070 mPa·s at 5 s⁻¹), others (e.g., 15 HSA–20 EtOH at 10 min) became unmeasurable, likely due to excessive protein denaturation and rapid gelation, leading to solid-like behavior that exceeds the rheometer’s detection range. This highlights the narrow formulation window for ethanol-induced HSA gelation: while ethanol promotes crosslinking via partial denaturation, excessive concentrations or prolonged exposure disrupt network homogeneity, resulting in brittle or non-processable gels.

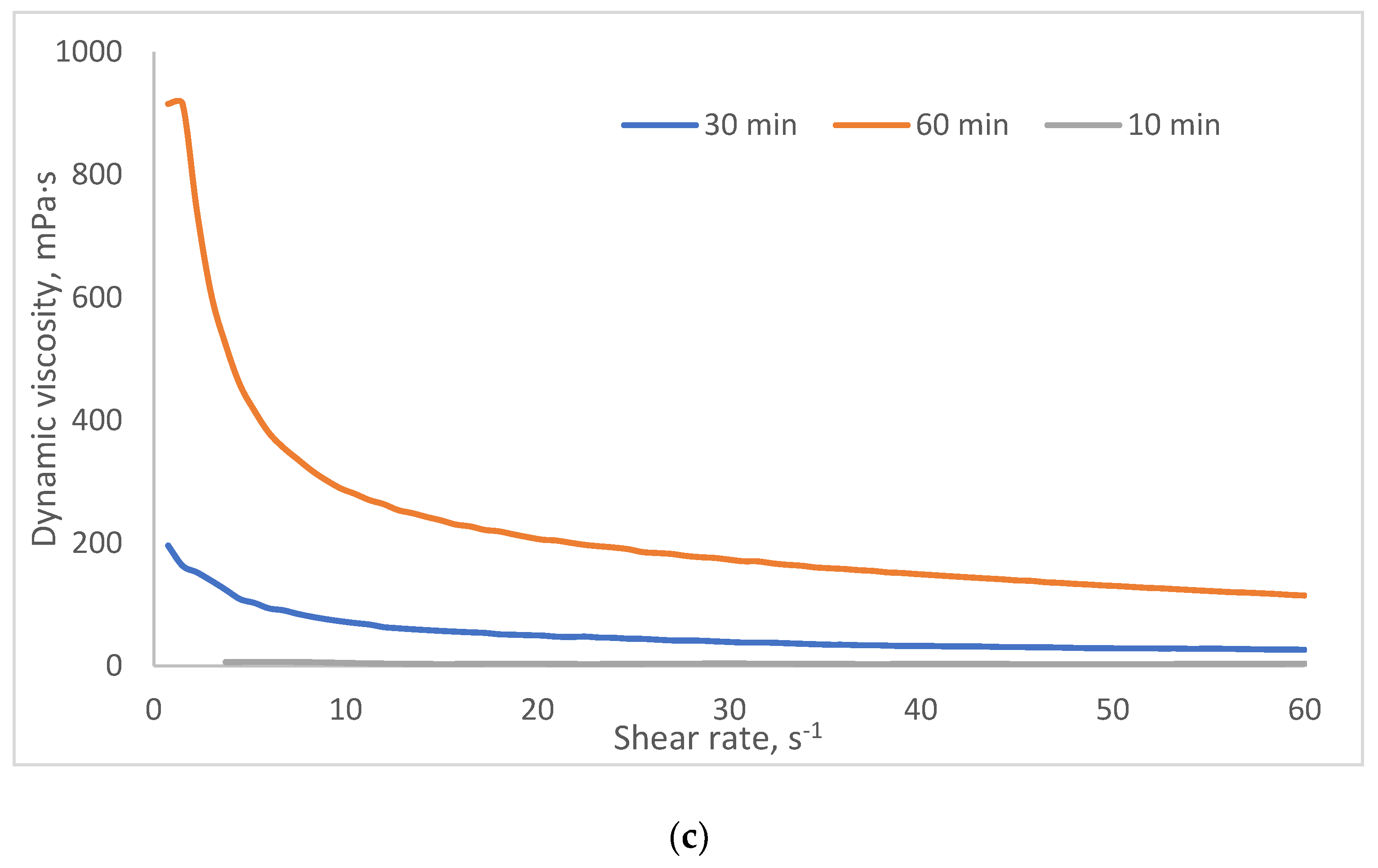

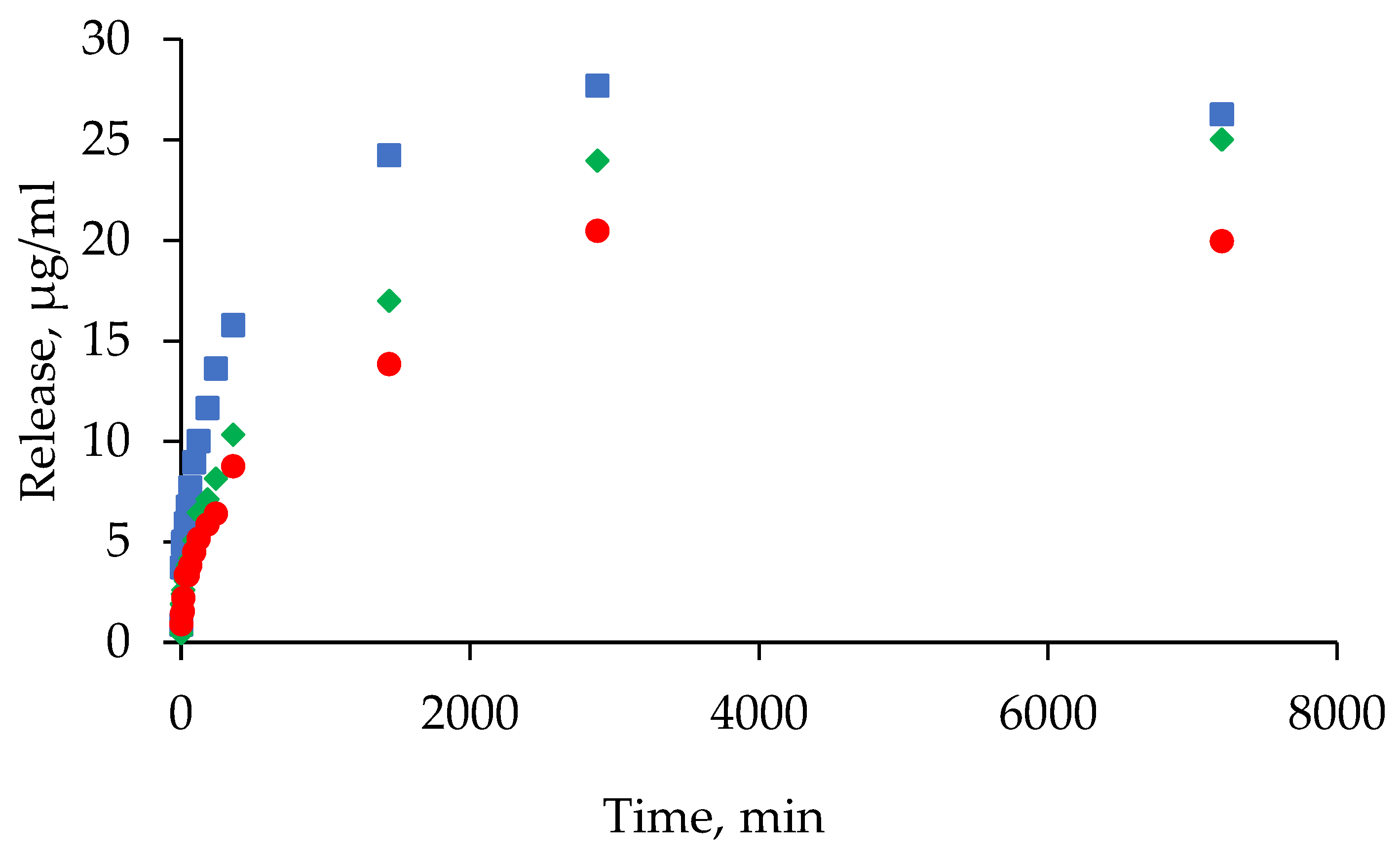

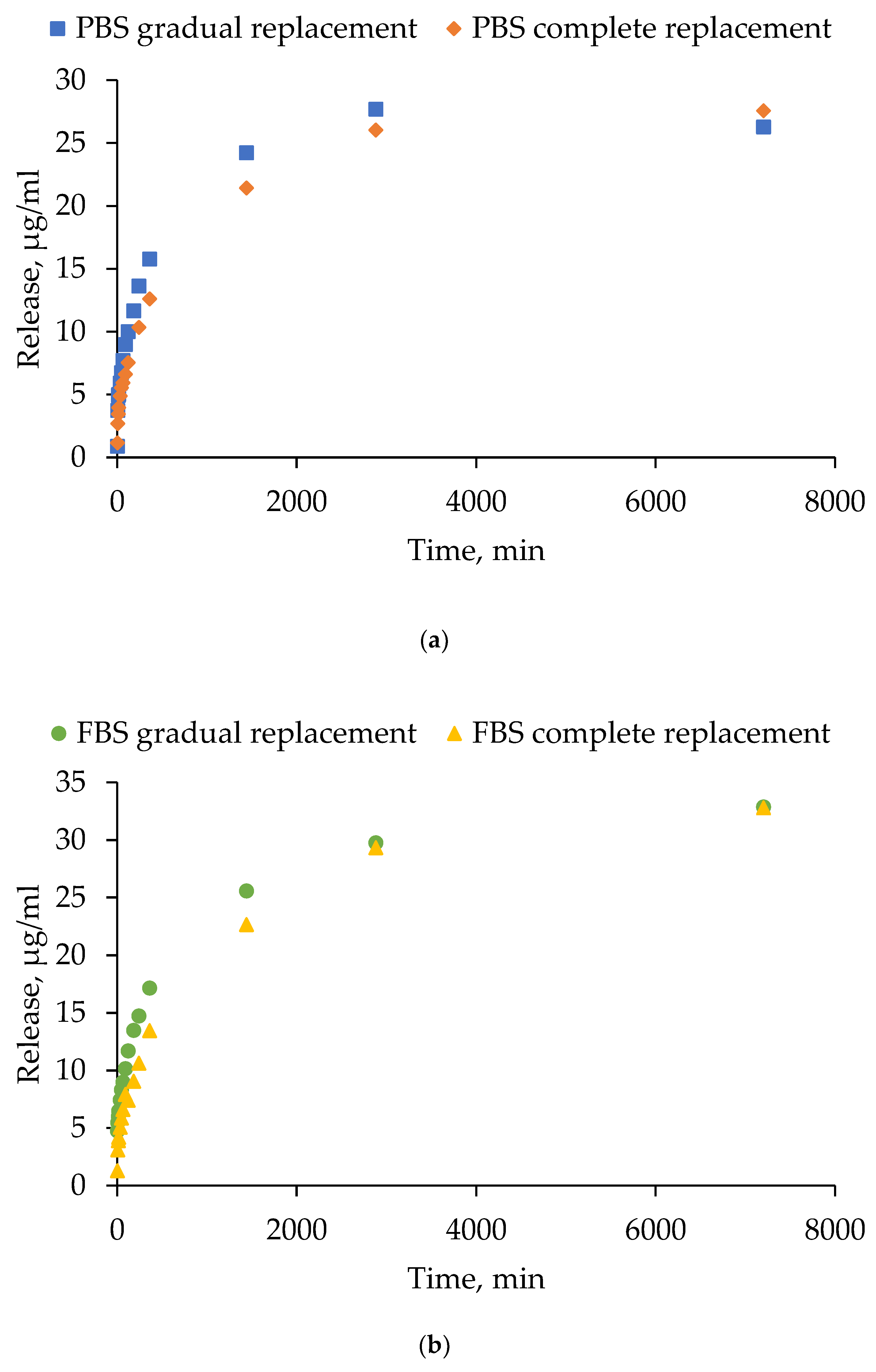

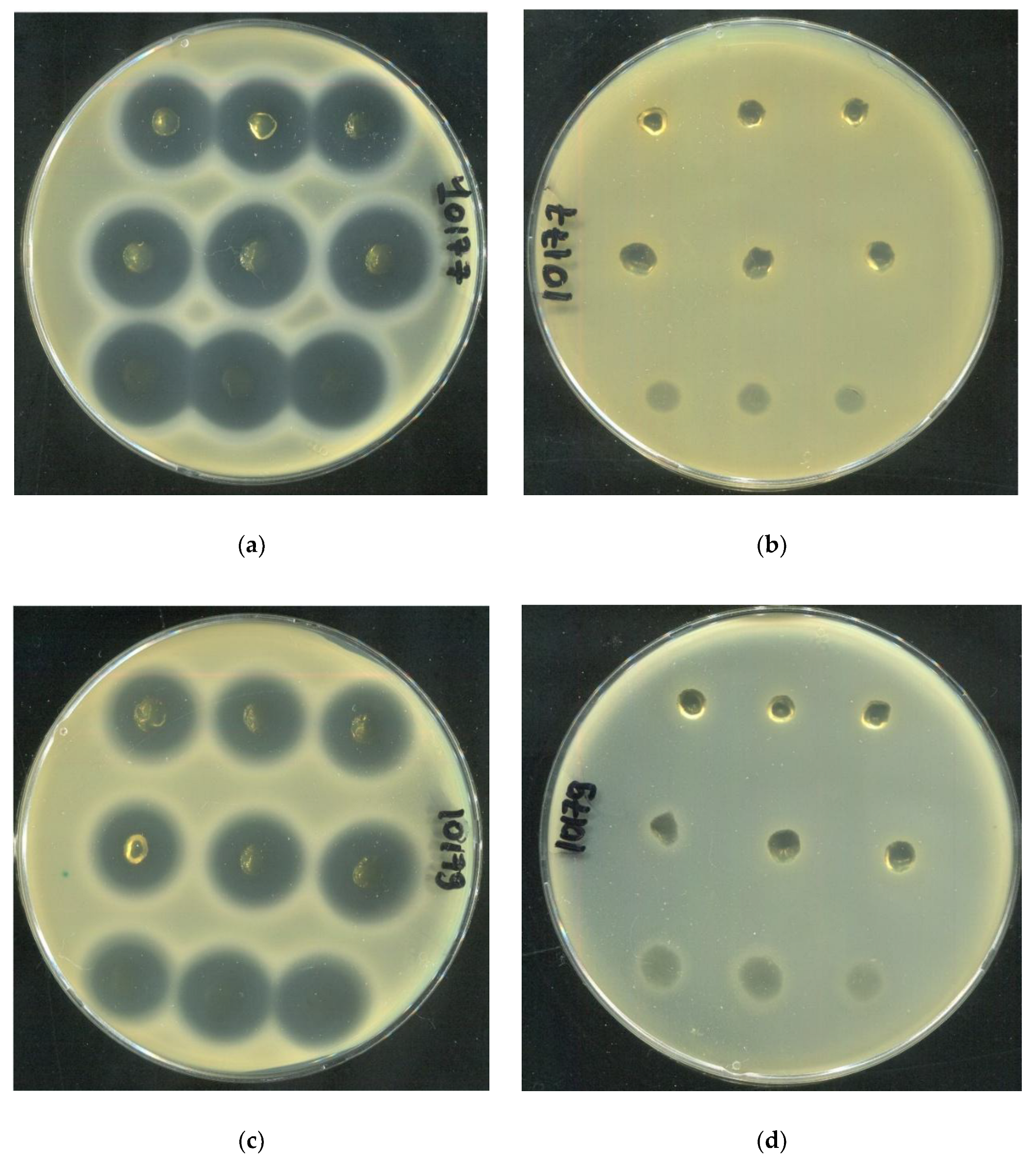

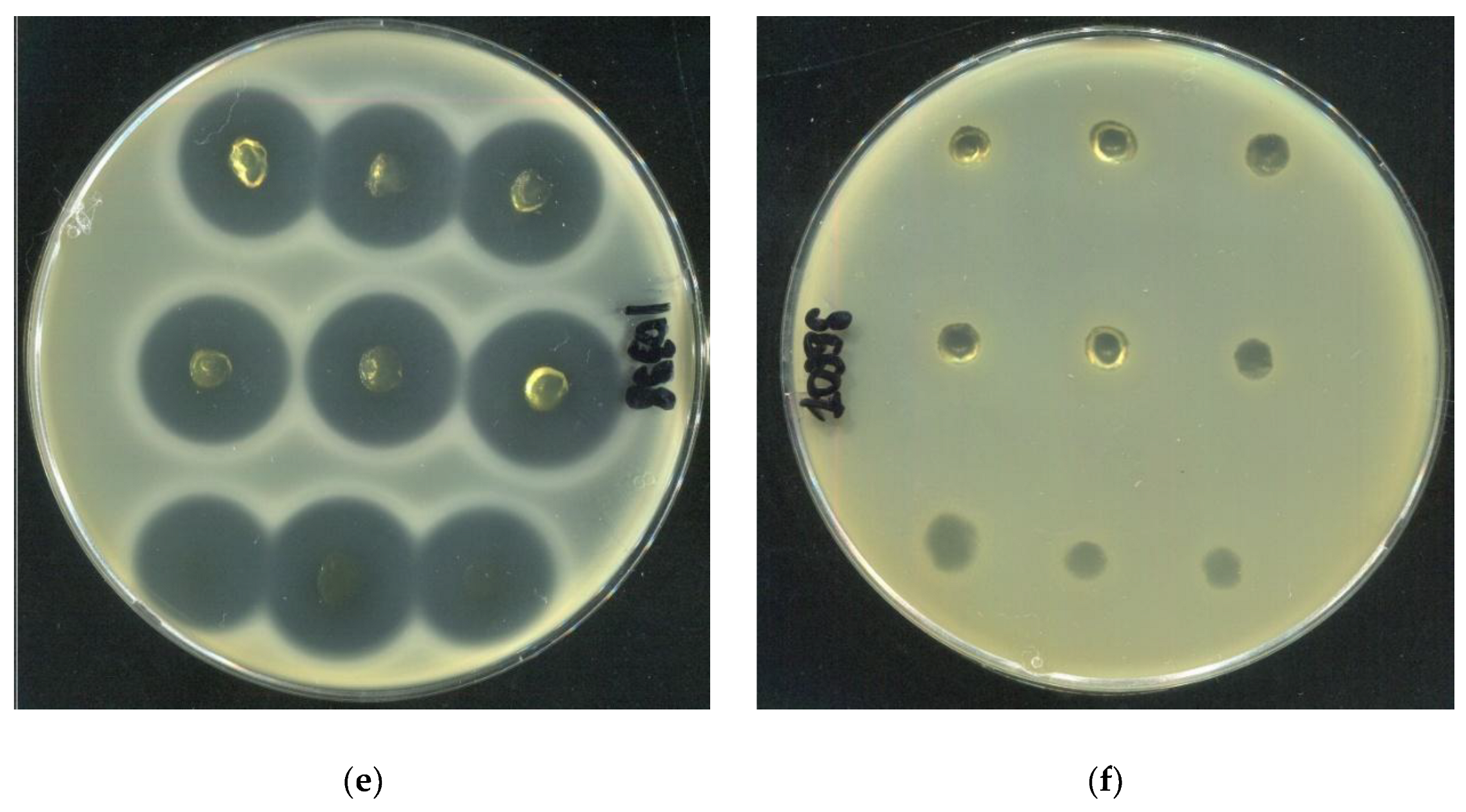

2.4. Investigation of the Rheological and Antibacterial Properties of Tetracycline-Loaded HSA-Based Hydrogels

| SA10177 | SA10179 | SA10398 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition zone area (cm²) | |||

| 20 HSA – 15 EtOH – 10 min | 3,38±0,10 | 2,57±0,05 | 2,87±0,06 |

| 15 HSA – 15 EtOH – 10 min | 4,36±0,16 | 2,93±0,18 | 3,15±0,08 |

| 15 HSA – 10 EtOH – 30 min | 3,90±0,06 | 2,66±0,10 | 2,83±0,39 |

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of Hydrogels Based on Human Serum Albumin

4.3. In situ Study of Gelation in HSA-Based Aqueous-Ethanol Systems

4.4. Measurement of Dynamic Viscosity of HSA-Based Hydrogels

4.5. Lyophilization of HSA-Based Hydrogels

4.6. Study of Lyophilizated HSA-Based Hydrogels Microstructure

4.7. Synthesis of Human Serum Albumin-Based Hydrogels with Tetracycline

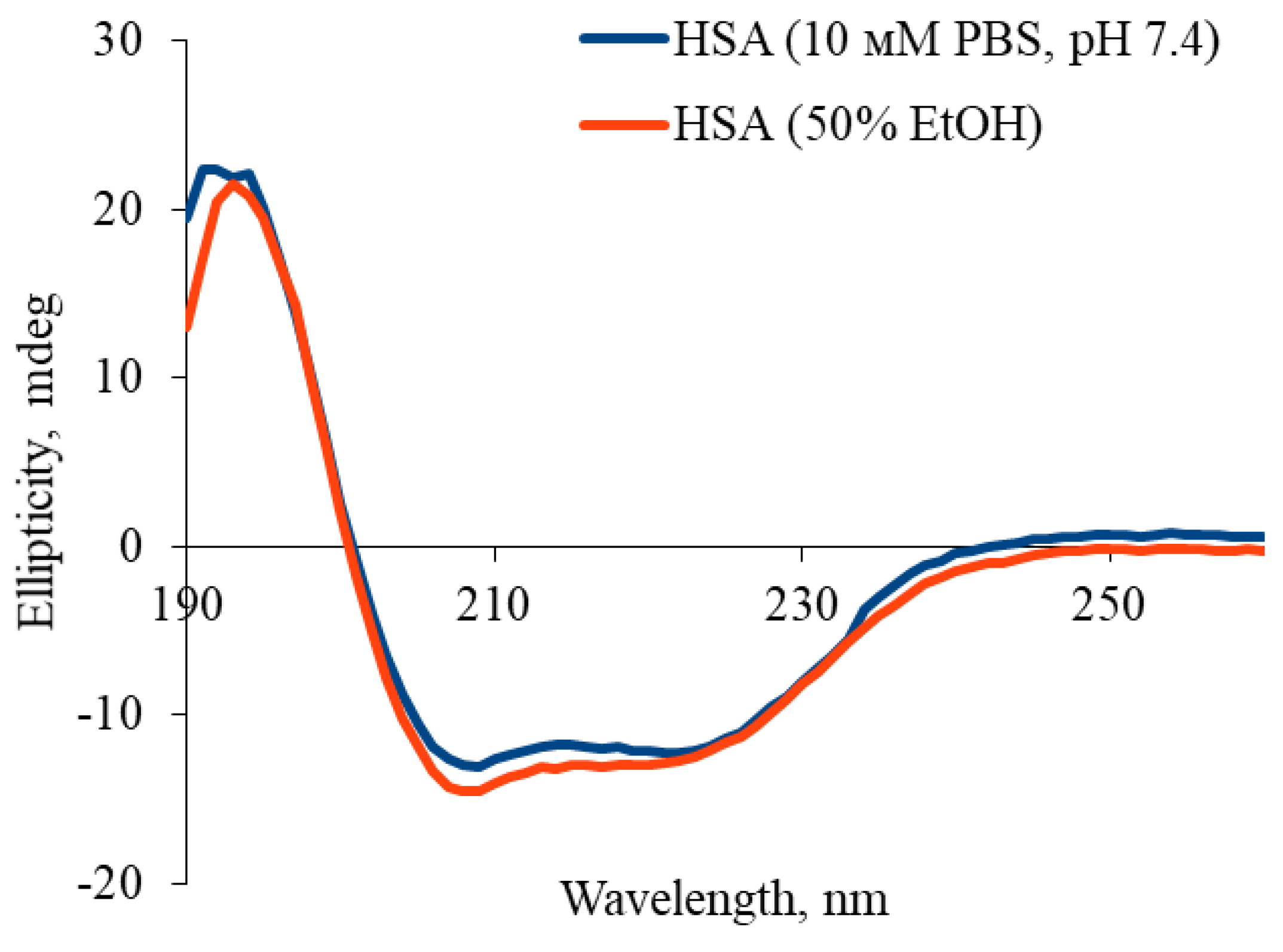

4.8. Determination of the Secondary Structures Content in HSA Molecule by Circular Dichroism

4.9. Study of the Kinetics of Tetracycline Release from Hydrogels Based on Human Serum Albumin

- Gradual medium replacement: after adding 1 ml of PBS/FBS to the hydrogel, 100 µl of supernatant was removed from the solution at specified time points and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS/FBS.

- Complete medium replacement: the procedure was similar, but 900 µl of supernatant was collected and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS/FBS. Samples were collected at the following time points: 0 min, 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, 120 min, 180 min, 240 min, 360 min, 24 h, 48 h and 120 h.

4.10. Antibacterial Activity of Tetracycline-Loaded Hydrogels Based on Human Serum Albumin

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSA | human serum albumin |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Peña, O. A.; Martin, P. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Skin Wound Healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25 (8), 599–616. [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, L.; Song, C.; Yao, L.; Xiao, J. Recent Progresses of Collagen Dressings for Chronic Skin Wound Healing. Collagen and leather 2023, 5 (1). [CrossRef]

- Gounden, V.; Singh, M. Hydrogels and Wound Healing: Current and Future Prospects. Gels 2024, 10 (1). [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, D.; Dai, K.; Wang, Y.; Song, P.; Li, H.; Tang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, C. Recent Progress of Collagen, Chitosan, Alginate and Other Hydrogels in Skin Repair and Wound Dressing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 208 (December 2021), 400–408. [CrossRef]

- Mani, M. P.; Mohd Faudzi, A. A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Ismail, A. F.; Jaganathan, S. K.; Tucker, N.; Rathanasamy, R. Sustainable Electrospun Materials with Enhanced Blood Compatibility for Wound Healing Applications—A Mini Review. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 27 (November 2022), 100457. [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Wei, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, H.; Zhao, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, R.; Cheng, Y. Hydrogel Wound Dressings Accelerating Healing Process of Wounds in Movable Parts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25 (12). [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Hussain, S.; ur-Rehman, M.; Hussain, A.; Akram, M. E.; Shahzad, S.; Rauf, Z.; Mujahid, M.; Ullah, A. Trends in Protein Derived Materials for Wound Care Applications. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 13 (1), 130–160. [CrossRef]

- Kuten Pella, O.; Hornyák, I.; Horváthy, D.; Fodor, E.; Nehrer, S.; Lacza, Z. Albumin as a Biomaterial and Therapeutic Agent in Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 (18). [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Zhu, H.; Deng, P.; Li, M.; Ji, Q.; He, H.; Jin, L.; Wang, B. Research Progress on Albumin-Based Hydrogels: Properties, Preparation Methods, Types and Its Application for Antitumor-Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11 (April), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, F.; Shao, Y.; Jin, A.; Lei, L. Engineered Protein-Based Materials for Tissue Repair: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 303 (January), 140674. [CrossRef]

- Naik, K.; Singh, P.; Yadav, M.; Srivastava, S. K.; Tripathi, S.; Ranjan, R.; Dhar, P.; Verma, A. K.; Chaudhary, S.; Parmar, A. S. 3D Printable, Injectable Amyloid-Based Composite Hydrogel of Bovine Serum Albumin and Aloe Vera for Rapid Diabetic Wound Healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11 (34), 8142–8158. [CrossRef]

- Rohiwal, S. S.; Ellederova, Z.; Tiwari, A. P.; Alqarni, M.; Elazab, S. T.; El-Saber Batiha, G.; Pawar, S. H.; Thorat, N. D. Self-Assembly of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)-Dextran Bio-Nanoconjugate: Structural, Antioxidant and: In Vitro Wound Healing Studies. RSC Adv. 2021, 11 (8), 4308–4317. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zeng, Z.; Yu, S.; Huang, J.; Geng, Z.; Pei, D.; Lu, D. Synthesis of Bovine Serum Albumin-Gelatin Composite Adhesive Hydrogels by Physical Crosslinking. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29 (7), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bercea, M.; Plugariu, I. A.; Dinu, M. V.; Pelin, I. M.; Lupu, A.; Bele, A.; Gradinaru, V. R. Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Bovine Serum Albumin Hybrid Hydrogels with Tunable Mechanical Properties †. Polymers (Basel). 2023, 15 (23). [CrossRef]

- Tincu, C. E.; Daraba, O. M.; Jérôme, C.; Popa, M.; Ochiuz, L. Albumin-Based Hydrogel Films Covalently Cross-Linked with Oxidized Gellan with Encapsulated Curcumin for Biomedical Applications. Polymers (Basel). 2024, 16 (12). [CrossRef]

- Navarra, G.; Peres, C.; Contardi, M.; Picone, P.; San Biagio, P. L.; Di Carlo, M.; Giacomazza, D.; Militello, V. Heat- and PH-Induced BSA Conformational Changes, Hydrogel Formation and Application as 3D Cell Scaffold. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 606, 134–142. [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Jiang, X.; Deng, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, X. Albumin-Based Dynamic Double Cross-Linked Hydrogel with Self-Healing Property for Antimicrobial Application. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2021, 208 (July), 112042. [CrossRef]

- Kaspchak, E.; Misugi Kayukawa, C. T.; Meira Silveira, J. L.; Igarashi-Mafra, L.; Mafra, M. R. Interaction of Quillaja Bark Saponin and Bovine Serum Albumin: Effect on Secondary and Tertiary Structure, Gelation and in Vitro Digestibility of the Protein. Lwt 2020, 121 (March 2019), 108970. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Mehwish, N.; Lee, B. H. Emerging Albumin Hydrogels as Personalized Biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 2023, 157, 67–90. [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Zhao, J.; Levy, G. K.; Macdonald, J.; Justin, A. W.; Markaki, A. E. Functionalisation of a Heat-Derived and Bio-Inert Albumin Hydrogel with Extracellular Matrix by Air Plasma Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10 (1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Das, M.; Mishra, N. K.; Chhabra, A.; Mishra, A.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, S. K.; Parmar, A. S. Tunning Self-Assembled Phases of Bovine Serum Albumin via Hydrothermal Process to Synthesize Novel Functional Hydrogel for Skin Protection against UVB. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11 (1), 1643–1657. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Singh, A. K.; Behera, S. P.; Gupta, S. Thermoresponsive BSA Hydrogels with Phase Tunability. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 119 (September 2020), 111590. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Dong, Q.; Song, D.; Hargrove, D.; Vora, S. R.; Ma, A. W. K.; Lu, X.; Lei, Y. Self-Healing of Thermally-Induced, Biocompatible and Biodegradable Protein Hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (61), 56183–56192. [CrossRef]

- Nnyigide, O. S.; Oh, Y.; Song, H. Y.; Park, E. K.; Choi, S. H.; Hyun, K. Effect of Urea on Heat-Induced Gelation of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) Studied by Rheology and Small Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS). Korea Aust. Rheol. J. 2017, 29 (2), 101–113. [CrossRef]

- Nnyigide, O. S.; Hyun, K. Effects of Anionic and Cationic Surfactants on the Rheological Properties and Kinetics of Bovine Serum Albumin Hydrogel. Rheol. Acta 2018, 57 (8–9), 563–573. [CrossRef]

- Sanaeifar, N.; Mäder, K.; Hinderberger, D. Macro- and Nanoscale Effect of Ethanol on Bovine Serum Albumin Gelation and Naproxen Release. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 (13). [CrossRef]

- Michnik, A.; Drzazga, Z. Effect of Ethanol on the Thermal Stability of Human Serum Albumin. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2007, 88 (2), 449–454. [CrossRef]

- Sanaeifar, N.; Mäder, K.; Hinderberger, D. Nanoscopic Characterization of Stearic Acid Release from Bovine Serum Albumin Hydrogels. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20 (8). [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.; Brayden, D. J.; Cheung, D. L.; Liew, A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Pandit, A. Albumin-Based Delivery Systems: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. J. Control. Release 2025, 380 (January), 375–395. [CrossRef]

- Asrorov, A. M.; Mukhamedov, N.; Kayumov, M.; Sh. Yashinov, A.; Wali, A.; Yili, A.; Mirzaakhmedov, S. Y.; Huang, Y. Albumin Is a Reliable Drug-Delivering Molecule: Highlighting Points in Cancer Therapy. Med. Drug Discov. 2024, 22 (February), 100186. [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Song, K.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Lee, R. J.; Teng, L. Albumin Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems. 2024, No. July.

- Ong, J.; Zhao, J.; Justin, A. W.; Markaki, A. E. Albumin-Based Hydrogels for Regenerative Engineering and Cell Transplantation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116 (12), 3457–3468. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Mu, W.; Han, X. Bovine Serum Albumin-Based Hydrogels: Preparation, Properties and Biological Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498 (July). [CrossRef]

- Navarra, G.; Giacomazza, D.; Leone, M.; Librizzi, F.; Militello, V.; San Biagio, P. L. Thermal Aggregation and Ion-Induced Cold-Gelation of Bovine Serum Albumin. Eur. Biophys. J. 2009, 38 (4), 437–446. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. L.; Lin, S. Y.; Li, M. J.; Wei, Y. S.; Hsieh, T. F. Temperature Effect on the Structural Stability, Similarity, and Reversibility of Human Serum Albumin in Different States. Biophys. Chem. 2005, 114 (2–3), 205–212. [CrossRef]

- Galisteo, M. L.; Mateo, P. L.; Sanchez-ruiz, J. M. Kinetic Study on the Irreversible Thermal Denaturation Kinase? Biochemistry 1991, 2061–2066.

- Lumry, R.; Eyring, H. Conformation Changes of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. 1954, 58 (2), 110–120. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Moghaddamnia, S. H.; Ranjbar, B.; Amani, M.; Marashi, S. A. Conformational Study of Human Serum Albumin in Pre-Denaturation Temperatures by Differential Scanning Calorimetry, Circular Dichroism and UV Spectroscopy. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 39 (5), 530–536. [CrossRef]

- Kragh-Hansen, U. Effects of Aliphatic Fatty Acids on the Binding of Phenol Red to Human Serum Albumin. Biochem. J. 1981, 195 (3), 603–613. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M. T.; Kuhlmann, M.; Hvam, M. L.; Howard, K. A. Albumin-Based Drug Delivery: Harnessing Nature to Cure Disease. Mol. Cell. Ther. 2016, 4 (1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, R. M.; Rogers, D. W.; Haebig, J. E.; Steck, T. L. The Interaction of Serum Albumin with Ethanol. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1962, 97 (3), 433–441. [CrossRef]

- Su Y. Y. T., J. B. Optical Activity Studies of Drug-Protein Complexes, the Interaction of Acetylsalicylic Acid with Human Serum Albumin and Myeloma Immunoglobulin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1978, 27 (7), 1043–1047. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, M.; Li, S.; Tian, M.; Wei, X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, H.; Dong, Q.; Zang, H. Study on the Secondary Structure and Hydration Effect of Human Serum Albumin under Acidic PH and Ethanol Perturbation with IR/NIR Spectroscopy. J. Innov. Opt. Health Sci. 2023, 16 (4), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Stojkov, G.; Niyazov, Z.; Picchioni, F.; Bose, R. K. Relationship between Structure and Rheology of Hydrogels for Various Applications. Gels 2021, 7 (4). [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Cao, Q.; Fang, H.; Tian, H. Recent Advances and Challenges of Injectable Hydrogels in Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2025, 385, 114021.

- Parvin N., Joo S. W., M. T. K. Injectable Biopolymer-Based Hydrogels : A Next-Generation Platform for Minimally Invasive Therapeutics. Gels 2025, 11 (6), 1–41.

- Miquelard-garnier, G.; Demoures, S.; Creton, C.; Hourdet, D.; Polyme, P.; June, R. V; Re, V.; Recei, M.; August, V. Synthesis and Rheological Behavior of New Hydrophobically Modified Hydrogels with Tunable Properties. Macromolecules 2006, 39 (23), 8128.

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Zekker, I.; Zhang, B.; Hendi, A. H.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zada, N.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, L. A.; Shah, T.; Khan, I. Review on Methylene Blue: Its Properties, Uses, Toxicity and Photodegradation. Water 2022, 14 (2), 242.

- Rusu, A.; Buta, E. L. The Development of Third-Generation Tetracycline Antibiotics and New Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13 (12), 2085.

| HSA (v/w) / T (ºС) | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | |||||

| 15 | |||||

| 20 |

| Sample | α-helices | β-sheets |

|---|---|---|

| HSA (10 mM PBS, pH 7.4) | 61.1 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| HSA (50% EtOH) | 54.3 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 0.2 |

| 55 °C | 60 °C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSA (v/w) / EtOH (v/v) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 0 | ||||||

| 5 | ||||||

| 10 | ||||||

| 15 | ||||||

| 20 | ||||||

| 10 v/w has | 15 v/w has | 20 v/w HSA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH (v/v) / t (min) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 10 | |||||||||

| 30 | |||||||||

| 60 | |||||||||

| 10 v/w has | 15 v/w has | 20 v/w HSA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH (v/v) / t (min) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 1 | |||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||

| 10 | |||||||||

| PBS | Water | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (v/v, %) | Hydrogel formation (Yes/No)) | Gelation onset time (s) | Average hydrodynamic diameter after gelation (nm) | Hydrogel formation (Yes/No)) | Gelation onset time (s) | Average hydrodynamic diameter after gelation (nm) |

| 0 | No | - | - | No | - | - |

| 5 | No | - | - | Yes | 420 | 1435±826 |

| 10 | No | - | - | Yes | 336 | 5845±3945 |

| 15 | Yes | 2700 | 443±170 | Yes | 210 | 8524±5284 |

| 20 | Yes | 600 | 405±159 | Yes | 156 | 8424±7585 |

| Hydrogel system | Dynamic viscosity at a shear rate of 5 s⁻¹, mPa·s | Dynamic viscosity at a shear rate of 15 s⁻¹, mPa·s | Dynamic viscosity at a shear rate of 45 s⁻¹, mPa·s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 HSA – 20 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – unmeasurable | 1 min – unmeasurable | 1 min – unmeasurable |

| 5 min – unmeasurable | 5 min – unmeasurable | 5 min – unmeasurable | |

| 10 min – unmeasurable | 10 min – unmeasurable | 10 мин – unmeasurable | |

| 20 HSA – 15 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – 2818 | 1 min – 1164 | 1 min – 732 |

| 5 min – 7660 | 5 min – 2500 | 5 min – 1129 | |

| 10 min – 6787 | 10 min – 2474 | 10 min – 1191 | |

| 20 HSA – 10 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 10 min – 25,57 | 10 min – 15,7 | 10 min – 12,53 |

| 30 min – 2223 | 30 min – 1072 | 30 min – 621,8 | |

| 60 min – 3889 | 60 min – 1495 | 60 min – 815,8 | |

| 15 HSA – 20 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – 7342 | 1 min – 2183 | 1 min – 930,5 |

| 5 min – 23290 | 5 min – 10850 | 5 min – 4379 | |

| 10 min – unmeasurable | 10 min – unmeasurable | 10 min – unmeasurable | |

| 15 HSA – 15 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – 1071 | 1 min – 398,9 | 1 min – 288,3 |

| 5 min – 3373 | 5 min – 1244 | 5 min – 590,9 | |

| 10 min – 5239 | 10 min – 1627 | 10 min – 714,4 | |

| 15 HSA – 10 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 10 min – 10.25 | 10 min – 7.85 | 10 min – 6.54 |

| 30 min – 1177 | 30 min – 413,7 | 30 min – 257,8 | |

| 60 min – 2542 | 60 min – 487,2 | 60 min – 252,3 | |

| 10 HSA – 20 EtOH – 60 ⁰C | 1 min – 3651 | 1 min – 1177 | 1 min – 515,9 |

| 5 min – 19760 | 5 min – 4868 | 5 min – 2011 | |

| 10 min – 32070 | 10 min – 7647 | 10 min – 3197 | |

| 10 HSA – 15 EtOH – 60 ⁰C | 1 min – 344 | 1 min – 153,1 | 1 min – 8,18 |

| 5 min – 754,1 | 5 min – 310,6 | 5 min – 8,17 | |

| 10 min – 2024 | 10 min – 1619 | 10 min – 24,52 | |

| 10 HSA – 10 EtOH – 60 ⁰C | 10 min – 6,54 | 10 min – 3,27 | 10 min – 3,27 |

| 30 min – 139 | 30 min – 57,22 | 30 min – 31,07 | |

| 60 min – 605 | 60 min – 237,1 | 60 min – 139,5 |

| Group | Samples included in the group | Dynamic viscosity range at 3 s⁻¹ (mPa·s) | Dynamic viscosity range at 15 s⁻¹ (mPa·s) | Dynamic viscosity range at 45 s⁻¹ (mPa·s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 HSA – 10 EtOH (30 min, 60 min) 10 HSA – 15 EtOH (10 min, 30 min) |

100-1000 | 50-300 | 20-150 |

| 2 | 10 HSA – 15 EtOH (10 min) 10 HSA – 20 EtOH (1 min) 15 HSA – 10 EtOH (30 min, 60 min) 15 HSA – 15 EtOH (1 min, 5 min) 20 HSA – 10 EtOH (30 min, 60 min) 20 HSA – 15 EtOH (1 min) |

1000-5000 | 300-1500 | 150-300 |

| 3 | 15 HSA – 15 EtOH (10 min) 15 HSA – 20 EtOH (1 min) 20 HSA – 15 EtOH (5 min, 10 min) |

5000-10000 | 1500-2500 | 300-1200 |

| 4 | 10 HSA – 20 EtOH (5 min) 15 HSA – 20 EtOH (5 min, 10 min) |

10000-25000 | 2500-10000 | 1200-4500 |

| Hydrogel system | The ratio of the dynamic viscosities at shear rates of 5 s⁻¹ and 15 s⁻¹ | The ratio of the dynamic viscosities at shear rates of 5 s⁻¹ and 45 s⁻¹ |

|---|---|---|

| 20 HSA – 20 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – unmeasurable | 1 min – unmeasurable |

| 5 min – unmeasurable | 5 min – unmeasurable | |

| 10 min – unmeasurable | 10 min – unmeasurable | |

| 20 HSA – 15 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – 2,42 | 1 min – 3,85 |

| 5 min – 3,06 | 5 min – 6,78 | |

| 10 min – 2,74 | 10 min – 5,70 | |

| 20 HSA – 10 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 10 min – 1,63 | 10 min – 2,04 |

| 30 min – 2,07 | 30 min – 3,58 | |

| 60 min – 2,60 | 60 min – 4,76 | |

| 15 HSA – 20 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – 3,36 | 1 min – 7,89 |

| 5 min – 2,15 | 5 min – 5,32 | |

| 10 min – unmeasurable | 10 min – unmeasurable | |

| 15 HSA – 15 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 1 min – 2,68 | 1 min – 3,71 |

| 5 min – 2,71 | 5 min – 5,71 | |

| 10 min – 3,22 | 10 min – 7,33 | |

| 15 HSA – 10 EtOH – 60 ⁰С | 10 min – 1,31 | 10 min – 1,56 |

| 30 min – 2,85 | 30 min – 4,56 | |

| 60 min – 5,22 | 60 min – 10,1 | |

| 10 HSA – 20 EtOH – 60 ⁰C | 1 min – 3,10 | 1 min – 7,08 |

| 5 min – 4,06 | 5 min – 9,82 | |

| 10 min – 4,19 | 10 min – 10,03 | |

| 10 HSA – 15 EtOH – 60 ⁰C | 1 min – 2,25 | 1 min – 42,5 |

| 5 min – 2,43 | 5 min – 92,3 | |

| 10 min – 1,25 | 10 min – 82,5 | |

| 10 HSA – 10 EtOH – 60 ⁰C | 10 min – 2,00 | 10 min – 2,00 |

| 30 min – 2,43 | 30 min – 4,47 | |

| 60 min – 2,55 | 60 min – 4,33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).