Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

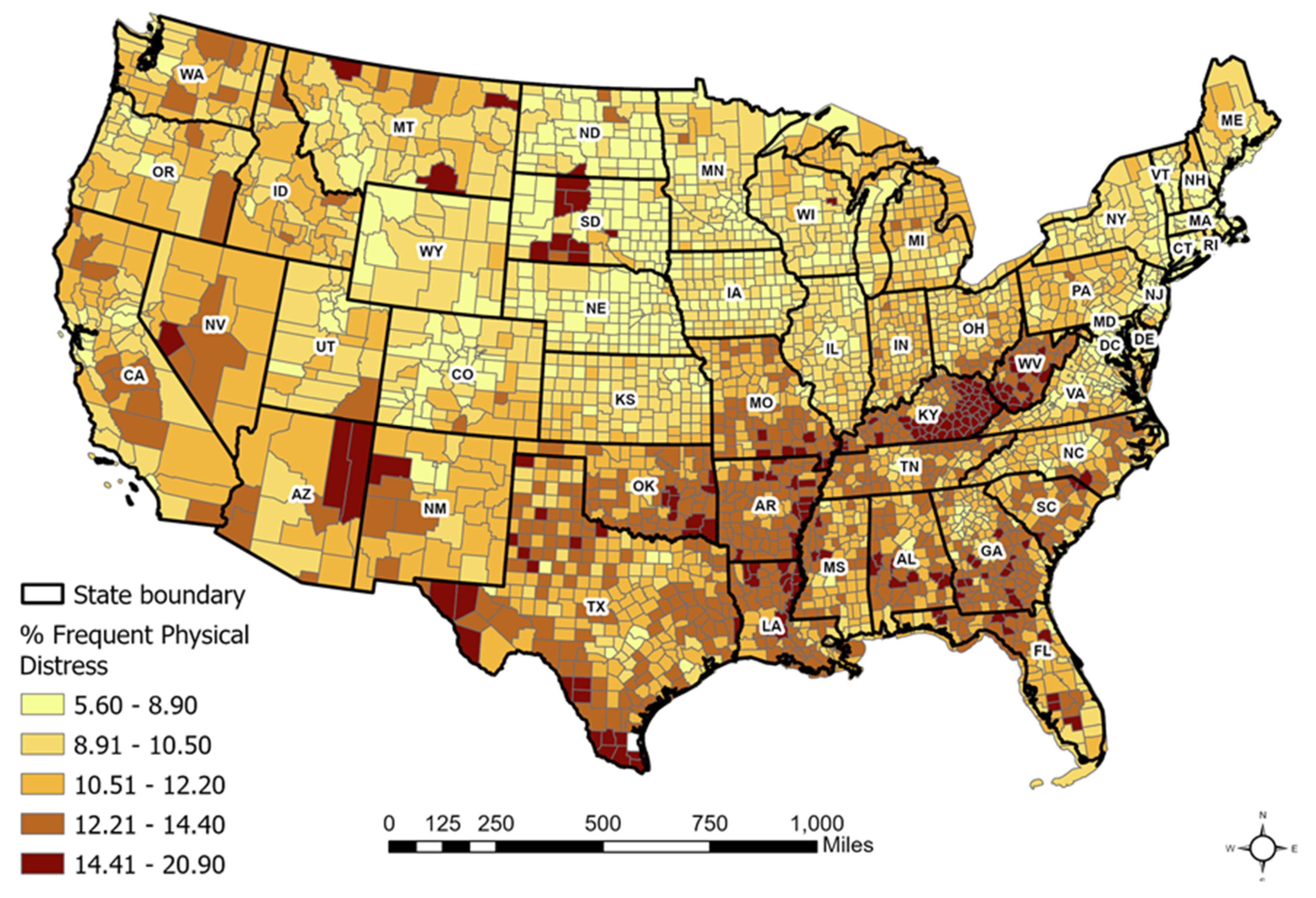

2.1. Frequent Physical Distress (FPD)

2.2. Socioeconomic and Health-Related Factors

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Bivariate Statistics

3.2. OLS Regression Analyses

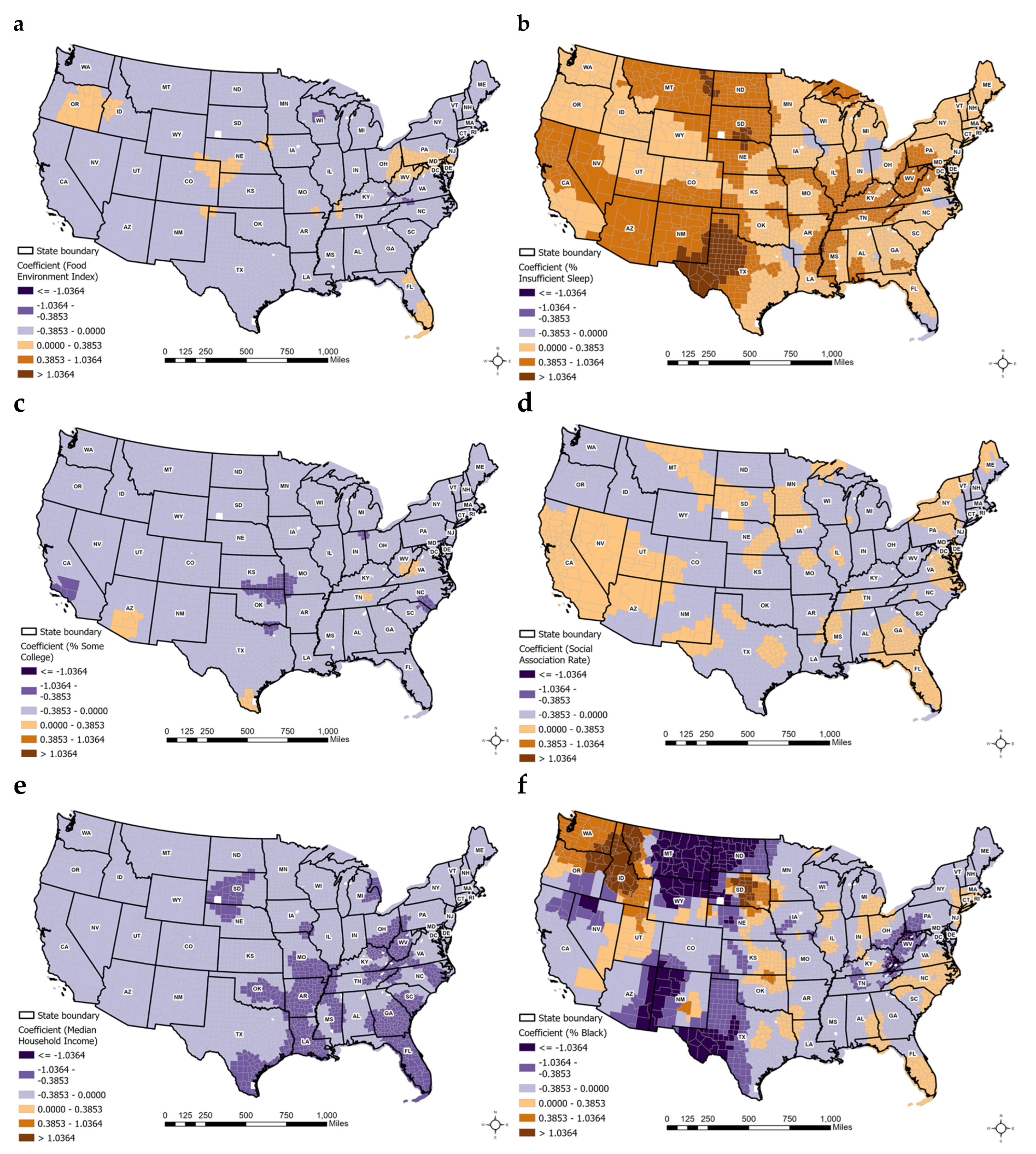

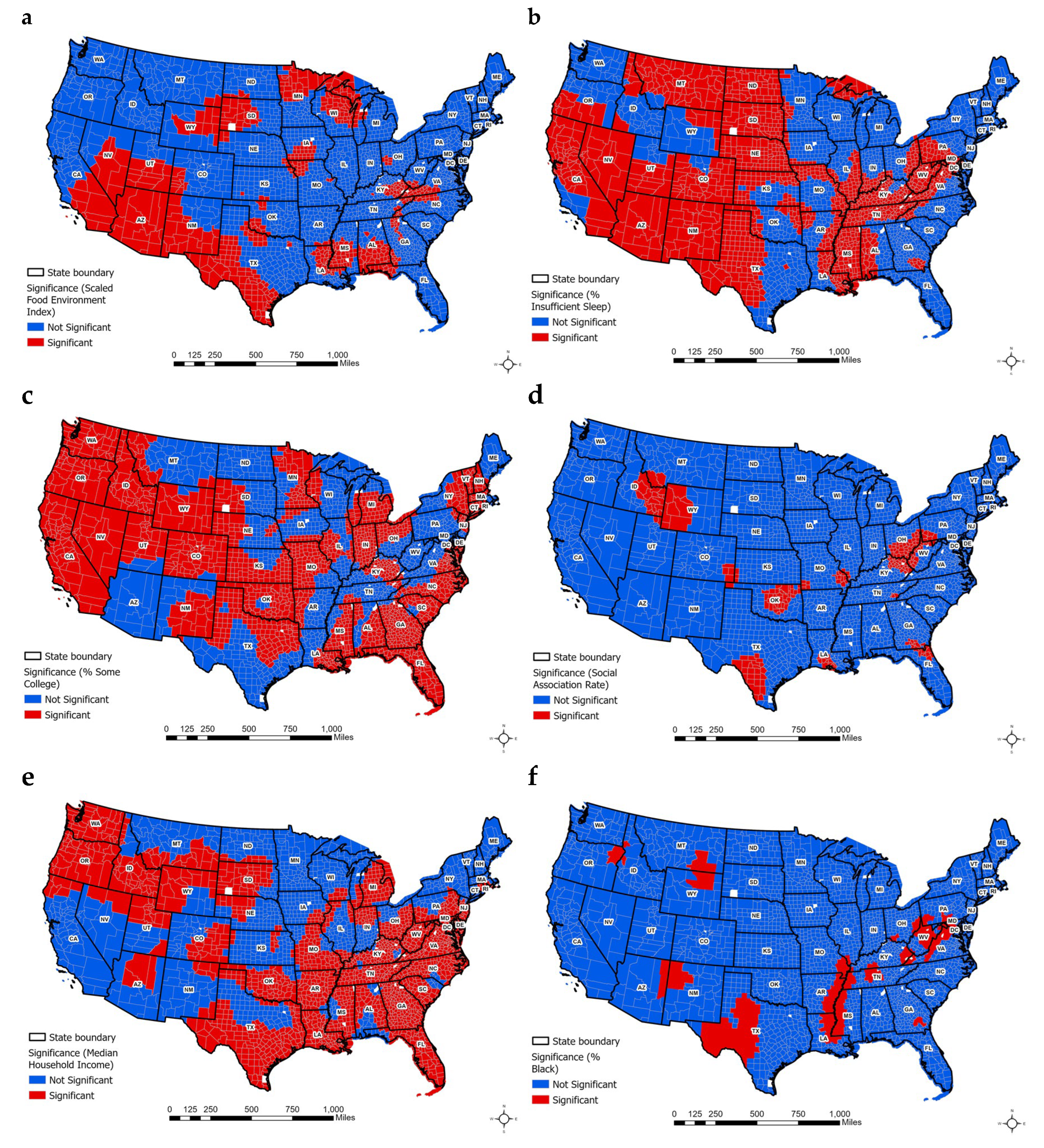

3.3. GWR and MGWR Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention Frequent physical distress: Indicators measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss.

- Dwyer-Lindgren, L.; Mackenbach, J.P.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Mokdad, A.H. Self-reported general health, physical distress, mental distress, and activity limitation by US county, 1995–2012. Population Health Metrics 2017, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Health Foundation. America’s Health Rankings Annual Report 2018. Available online: https://assets.americashealthrankings.org/app/uploads/ahrannual-2018.pdf.

- Hunyadi, J.V.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, Q.; Strong, L.L.; Bauer, C. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Chronic Disease Burden in the U.S., 2018–2021. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2025, 68(1), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yue, L.; Jia, Z.; Su, L. Spatial Inequalities and Influencing Factors of Self-Rated Health and Perceived Environmental Hazards in a Metropolis: A Case Study of Zhengzhou City, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(12), 7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.M.; Burch, A.E. Disparities in perceived physical and mental wellness: Relationships between social vulnerability, cardiovascular risk factor prevalence, and health behaviors among elderly US residents. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231163639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships; Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, H. Using geographically weighted regression for social inequality analysis: association between mentally unhealthy days (MUDs) and socioeconomic status (SES) in U.S. counties. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá, AC L.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Charlton, M.E.; Mota, B.; Barbosa, P.M.; Fotheringham, A.S. The pyrogeography of sub-Saharan Africa: A study of the spatial non-stationarity of fire–environment relationships using GWR. Journal of Geographical Systems 2011, 13(3), 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.C.; Chiang, P.H.; Su, M.D.; Wang, H.W.; Liu, M.S. Geographic disparity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality rates among the Taiwan population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Wen, T.H. Using geographically weighted regression (GWR) to explore spatial varying relationships of immature mosquitoes and human densities with the incidence of dengue. Int J Env Res Pub He 2011, 8, 2798–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Xu, Y. An ecological study on the spatially varying association between adult obesity rates and altitude in the United States: using geographically weighted regression. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H. Identifying spatial association between Frequent Mental Distress (FMD) and air pollution (PM2.5): Evidence from 2,648 counties in the United States. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Yang, W.; Kang, W. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR). Annals of the American Association of Geographers 2017, 107(6), 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshan, T.M.; Li, Z.; Kang, W.; Wolf, L.J.; Fotheringham, A.S. mgwr: A Python Implementation of Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression for Investigating Process Spatial Heterogeneity and Scale. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2019, 8(6), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention Chronic Disease Indicators: Health Status—Indicator, D.e.f.i.n.i.t.i.o.n.s.; US Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/indicator-definitions/health-status.html.

- County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Frequent Physical Distress; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. 2023. Available online: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org.

- Ha, H. Geographic distribution of lung and bronchus cancer mortality and elevation in the United States: exploratory spatial data analysis and spatial statistics. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H. Using geographically weighted regression for social inequality analysis: Association between Mentally Unhealthy Days (MUDs) and socioeconomic status (SES) in U.S. Counties. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerson, P.A. Statistical Methods for Geography, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M. Geographically weighted regression—Modelling spatial non-stationarity. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series D (The Statistician) 1998, 47(3), 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) PLACES: Local data for better health—Measure definitions: Frequent physical, d.i.s.t.r.e.s.s.; US Department of Health and Human Services. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/places/measure-definitions/health-status.html.

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2025: Technical documentation and measures (Frequent Physical Distress). 2025. Available online: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org.

- America’s Health Rankings. America’s Health Rankings Annual Report 2019; America’s Health Rankings, United Health Foundation. 2019. Available online: https://assets.americashealthrankings.org/ahr_2019annualreport.pdf.

- Weeks, B.; Chang, J.E.; Pagán, J.A.; Lumpkin, J.; Michael, D.; Salcido, S.; Kim, A.; Speyer, P.; Aerts, A.; Weinstein, J.N. Rural–urban disparities in health outcomes, clinical care, health behaviors, and social determinants of health and an action-oriented, dynamic tool for visualizing them. PLOS Global Public Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHADAC Measuring state-level disparities in unhealthy days (2018–2020); State Health Compare, University of Minnesota. December 2021. Available online: https://www.shadac.org/news/measuring-state-level-disparities-unhealthy-days-infographics.

- Department of Population Health; NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Frequent physical distress: Congressional District Health Dashboard. 2024. Available online: https://www.congressionaldistricthealthdashboard.org.

- Liu, J.; Jiang, N.; Fan, A.Z.; Thompson, W.W.; Ding, R.; Ni, S. Investigating the associations between socioeconomic factors and unhealthy days among adults using zero-inflated negative binomial regression. SAGE Open 2023, 13(3), 21582440231194163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Leung, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Spatial non-stationarity test of regression relationships in the multiscale geographically weighted regression model. Spatial Statistics 2024, 62, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M.; Dong, G.; Harris, R.; Lu, B.; Lü, Y.; Murakami, D.; Nakaya, T.; Wang, Y.; Harris, P. The GWR route map: A guide to the informed application of geographically weighted regression. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.06070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Oshan, T.M. Scale and correlation in multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR). Journal of Geographical Systems 2025, 27(3), 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Tiefelsdorf, M. Multicollinearity and correlation among local regression coefficients in geographically weighted regression. Journal of Geographical Systems 2005, 7(2), 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Mean | SD | Bivariate | |

|

Dependent variable: Frequent Physical Distress (FPD) |

2673 |

10.942 |

2.083 |

1.000** |

| Independent variables: | ||||

| Health behaviors: | ||||

| % adult smoking | 2673 | 19.983 | 4.004 | 0.823** |

| % adult obesity | 2673 | 36.187 | 4.674 | 0.671** |

| Food environment index | 2673 | 7.502 | 1.058 | -0.675** |

| % physically inactive | 2673 | 25.627 | 5.088 | 0.877** |

| % with access to exercise | 2673 | 63.732 | 21.258 | -0.455** |

| % alcohol impaired | 2673 | 19.034 | 3.174 | -0.548** |

| % insufficient sleep | 2673 | 34.591 | 3.591 | 0.727** |

| Clinical care: | ||||

| % uninsured | 2673 | 11.511 | 5.029 | 0.449** |

| Primary care physician ratio | 2673 | 55.215 | 34.400 | -0.388** |

| Mental health provider rate | 2673 | 191.972 | 192.908 | -0.181** |

| Preventable hospitalization rate | 2673 | 3015.104 | 1112.770 | 0.489** |

| Social economic environment: | ||||

| % of college education | 2673 | 58.984 | 11.296 | -0.764** |

| % unemployment | 2673 | 4.710 | 1.655 | 0.352** |

| Association rate | 2673 | 11.453 | 4.684 | -0.195** |

| Median household income | 2673 | 59606.975 | 15553.751 | -0.762** |

| Demographics: | ||||

| % 65 and over | 2673 | 19.716 | 4.554 | 0.002 |

| % African American | 2673 | 9.574 | 14.282 | 0.269** |

| % Female | 2673 | 49.782 | 1.975 | -0.027 |

| % Rural | 2673 | 53.376 | 29.675 | 0.306** |

| Abbreviation: SD, Standard Deviation; **Significant at p>0.05 | ||||

| Coefficient | S.E | t-value | p-value | 95% C.I | VIF | |||

| Model 1- Adjusted R2: 0.855 | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Constant | 10.183 | 0.607 | 16.786 | 0.000 | 8.993 | 32.580 | ||

| Health behaviors: | ||||||||

| % adult obesity | 0.040 | 0.006 | 7.294 | 0.000** | 0.029 | 0.051 | 2.834 | |

| Food environment index | -0.305 | 0.022 | -14.116 | 0.000** | -0.348 | -0.263 | 2.229 | |

| % with access to exercise | -0.001 | 0.001 | -1.333 | 0.183 | -0.004 | 0.001 | 2.313 | |

| % alcohol impaired | -0.054 | 0.007 | -8.117 | 0.000** | -0.067 | -0.041 | 1.895 | |

| % insufficient sleep | 0.154 | 0.007 | 20.590 | 0.000** | 0.139 | 0.169 | 3.070 | |

| Clinical care: | ||||||||

| % uninsured | 0.033 | 0.004 | 8.733 | 0.000** | 0.025 | 0.040 | 1.521 | |

| Primary care physician ratio | 0.002 | 0.001 | 3.270 | 0.001** | 0.001 | 0.003 | 1.670 | |

| Mental health provider rate | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.027 | 0.002** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.513 | |

| Preventable hospitalization rate | 9.523E-5 | 0.000 | 5.669 | 0.000** | 0.061 | 0.094 | 1.487 | |

| Social economic environment: | ||||||||

| % of college education | -0.042 | 0.002 | -17.278 | 0.000** | -0.047 | -0.037 | 3.218 | |

| % unemployment | 0.068 | 0.011 | 6.044 | 0.000** | 0.046 | 0.090 | 1.474 | |

| Association rate | -0.042 | 0.004 | -11.086 | 0.000** | -0.050 | -0.035 | 1.348 | |

| Median household income | -3.755E-5 | 0.000 | -21.451 | 0.000** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.155 | |

| Demographics: | ||||||||

| % 65 and over | -0.040 | 0.005 | -8.898 | 0.000** | -0.049 | -0.032 | 1.829 | |

| % African American | -0.025 | 0.001 | -17.924 | 0.000** | -0.028 | -0.022 | 1.664 | |

| % Female | -0.044 | 0.009 | 4.875 | 0.000** | 0.026 | 0.061 | 1.334 | |

| % Rural | 0.006 | 0.001 | 6.475 | 0.000** | 0.004 | 0.007 | 2.882 | |

| Abbreviation: SE, Standard Error; **Significant at p>0.05 | ||||||||

| Coefficient Range | |||||||||

| Model 2- Adjusted R2: 0.912 (GWR); AICc: 1,671.088 | |||||||||

| Model 3- Adjusted R2: 0.918 (MGWR); AICc: 1,633.507 | Mean | S.D | Minimum | Maximum | Optimal Neighbors (% of features) |

Significance (% of features) |

|||

| Intercept | -0.102 | 0.432 | -4.282 | 2.382 | 103 (3.35) | 798 (25.94) | |||

| Health behaviors: | |||||||||

| Food environment index | -0.134 | 0.094 | -0.441 | 0.177 | 120 (3.90) | 622 (20.22) | |||

| % insufficient sleep | 0.382 | 0.295 | -0.210 | 1.773 | 108 (3.85) | 1495 (48.60) | |||

| Social economic environment: | |||||||||

| % of college education | -0.211 | 0.088 | -0.547 | 0.059 | 132 (4.29) | 1858 (60.40) | |||

| Association rate | -0.039 | 0.087 | -0.367 | 0.206 | 135 (4.39) | 252 (8.19) | |||

| Median household income | -0.309 | 0.147 | -0.829 | -0.024 | 121 (3.93) | 1902 (61.83) | |||

| Demographics: | |||||||||

| % African American | -0.186 | 0.635 | -7.324 | 3.874 | 101 (3.28) | 330 (10.73) | |||

| Abbreviation: SD, Standard Deviation; **Significant at p>0.05 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).