Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

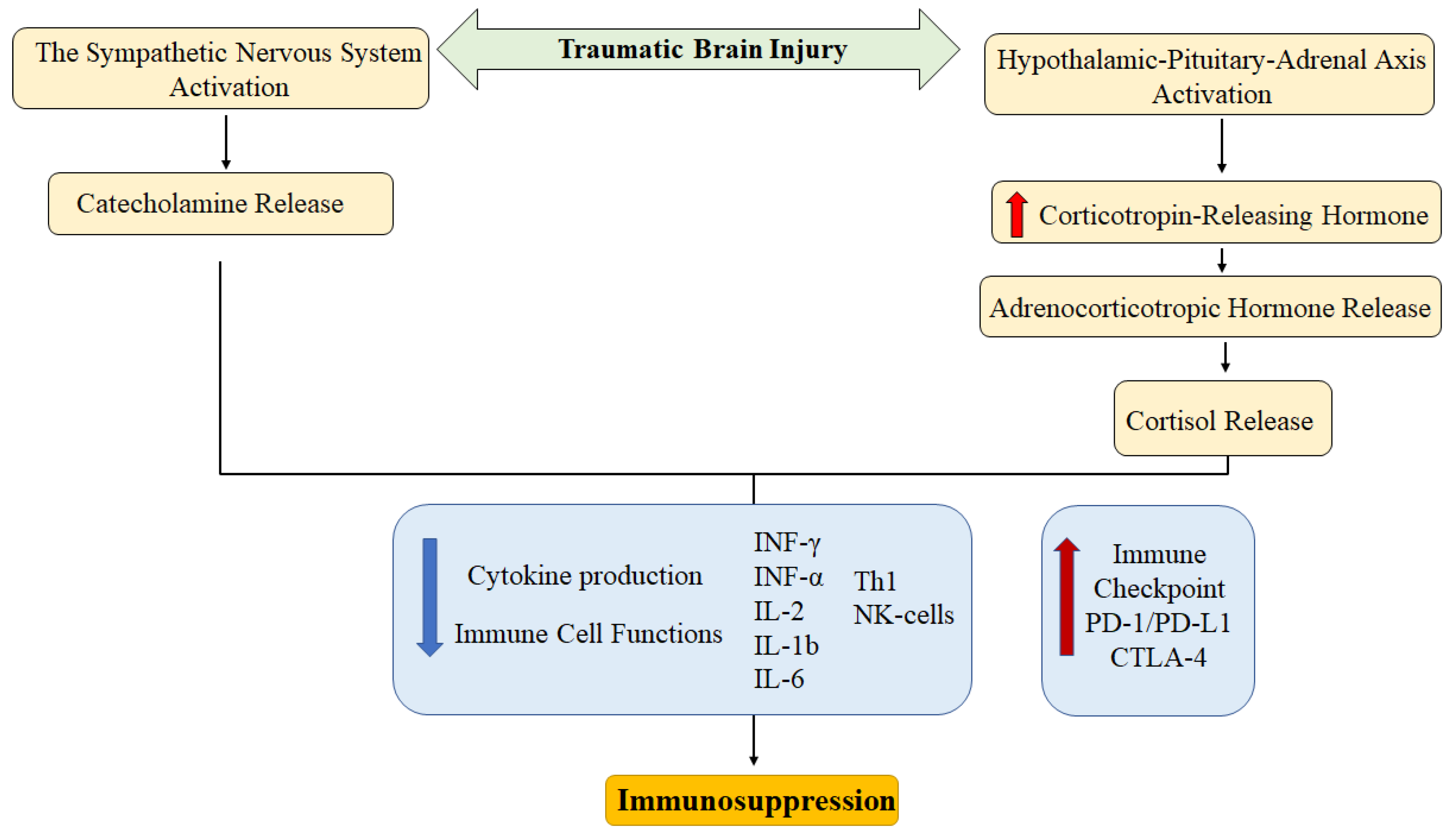

2. The Immune System Alteration

2.1. The Immune System in Traumatic Brain Injury

2.2. The Immune System in Cancer

3. Immune Checkpoints

4. The Sympathetic Nervous System in Immune Regulation

4.1. Cancer

4.2. Traumatic Brain Injury

5. Interaction between Local and Systemic Inflammation

5.1. Cancer

5.2. Traumatic Brain Injury

6. Methods for Reducing Inflammation and Reversal of T-Cell Exhaustion

6.1. Cancer

6.2. Traumatic Brain Injury

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| The BBB | The blood-brain barrier |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

References

- Chavda, V.P.; Feehan, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Inflammation: The Cause of All Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Baby, D.; Rajguru, J.P.; Patil, P.B.; Thakkannavar, S.S.; Pujari, V.B. Inflammation and cancer. Ann. Afr. Med. 2019, 18, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.X.; Zhou, M.; Ma, H.L.; Qiao, Y.B.; Li, Q.S. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in Various Diseases and Anti-inflammatory Therapies Containing Natural Products. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1576–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, S.; Hou, Y. Local and systemic inflammation triggers different outcomes of tumor growth related to infiltration of anti-tumor or pro-tumor macrophages. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 2022, 135, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.; Perica, K.; Klebanoff, C.A.; Wolchok, J.D. Clinical implications of T cell exhaustion for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhou, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Mechanisms of CD8+ T cell exhaustion and its clinical significance in prognosis of anti-tumor therapies: A review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 159, 114843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.; Treviño-Tello, F.; Atisha-Fregoso, Y.; Llorente, L.; Fragoso-Loyo, H.; Jakez-Ocampo, J. Exhausted T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus patients in long-standing remission. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021, 204, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globig, A.M.; Mayer, L.S.; Heeg, M.; Andrieux, G.; Ku, M.; Otto-Mora, P.; Hipp, A.V.; Zoldan, K.; Pattekar, A.; Rana, N.; et al. Exhaustion of CD39-Expressing CD8+ T Cells in Crohn's Disease Is Linked to Clinical Outcome. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 965–981.e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xu, J.; Liang, J. T-cell exhaustion in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: New implications for immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 977394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, P.M.; Banerjee, A.; Ghosal, A.; Layek, B. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Knowledge and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; Manley, G.T.; Abrams, M.; Åkerlund, C.; Andelic, N.; Aries, M.; Bashford, T.; Bell, M.J.; Bodien, Y.G.; et al. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 1004–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, B. Global, regional, and national burdens of traumatic brain injury from 1990 to 2021. Front. Public Health. 2025, 13, 1556147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Anderson, D.B.; Chen, L.; Feng, S.; Zhou, H. Global, regional and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open. 2023, 13, e075049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Faruque, S.; Mutebi, C.; Nagirimadugu, N.V.; Kim, A.; Mahendran, M.; Sullo, E.; Morey, R.; Turner, R.W., 2nd. Investigating the relationship between mild traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: a systematic review. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 4635–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Liu, P.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z. Oxidative burst of circulating neutrophils following traumatic brain injury in human. PLoS One 2013, 8, e68963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sivakumar, G.; Goodden, J.R.; Tyagi, A.K.; Chumas, P.D. Prognostic value of leukocytosis in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2020, 27, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwulst, S.J.; Trahanas, D.M.; Saber, R.; Perlman, H. Traumatic brain injury-induced alterations in peripheral immunity. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 75, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.D.; Bai, S.; Chen, X.; Wei, H.J.; Jin, W.N.; Li, M.S.; Yan, Y.; Shi, F.D. Alterations of natural killer cells in traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Bull. 2014, 30, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinertz, H.; Hepner-Schefczyk, M.; Ehnert, S.; Claus, M.; Halbgebauer, R.; Boller, L.; Huber-Lang, M.; Cinelli, P.; Kirschning, C.; Flohé, S.; et al. Circulating growth/differentiation factor 15 is associated with human CD56bright natural killer cell dysfunction and nosocomial infection in severe systemic inflammation. EBioMedicine 2019, 43, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotosek Tokmadzic, V.; Laskarin, G.; Mahmutefendic, H.; Lucin, P.; Mrakovcic-Sutic, I.; Zupan, Z.; Sustic, A. Expression of cytolytic protein-perforin in peripheral blood lymphocytes in severe traumatic brain injured patients. Injury 2012, 43, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Wan, Q. NKT Cells in Neurological Diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-El-Hassan, H.; Rezende, R.M.; Izzy, S.; Gabriely, G.; Yahya, T.; Tatematsu, B.K.; Habashy, K.J.; Lopes, J.R.; de Oliveira, G.L.V.; Maghzi, A.H.; et al. Vγ1 and Vγ4 gamma-delta T cells play opposing roles in the immunopathology of traumatic brain injury in males. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenouard, A.; Chesneau, M.; Braza, F.; Dejoie, T.; Cinotti, R.; Roquilly, A.; Brouard, S.; Asehnoune, K. Phenotype and functions of B cells in patients with acute brain injuries. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 68, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.J.; Maheshwari, S.; Levy, E.; Poznansky, M.C.; Whalen, M.J.; Sîrbulescu, R.F. B cell treatment promotes a neuroprotective microenvironment after traumatic brain injury through reciprocal immunomodulation with infiltrating peripheral myeloid cells. J. Neuroinflammation. 2023, 20, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sribnick, E.A.; Popovich, P.G.; Hall, M.W. Central nervous system injury-induced immune suppression. Neurosurg. Focus. 2022, 52, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Xu, X. Role of damage-associated molecular patterns in the pathogenesis and therapeutics of traumatic brain injury. Burns Trauma. 2025, 13, tkaf043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. The potential importance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3099–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, M.; Asehnoune, K.; Roquilly, A. Immune modulation after traumatic brain injury. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 995044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesz, A.; Dalpke, A.; Mracsko, E.; Antoine, D.J.; Roth, S.; Zhou, W.; Yang, H.; Na, S.Y.; Akhisaroglu, M.; Fleming, T.; et al. DAMP signaling is a key pathway inducing immune modulation after brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xu, J.; Chai, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, P. Dynamic changes in trauma-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells after polytrauma are associated with an increased susceptibility to infection. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 11063–11068. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj, S.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Regulation of suppressive function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by CD4+ T cells. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2012, 22, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, S.J.; Ritzel, R.M.; Glaser, E.P.; Henry, R.J.; Faden, A.I.; Loane, D.J. Sex Differences in Acute Neuroinflammation after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury Are Mediated by Infiltrating Myeloid Cells. J. Neurotrauma. 2019, 36, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomi, S.; Koyama, Y.; Watabe, T.; Ohnishi, M.; Ogura, H.; Yamashita, T.; Shimazu, T. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Infiltrate the Brain and Suppress Neuroinflammation in a Mouse Model of Focal Traumatic Brain Injury. Neuroscience 2019, 406, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiwai, H.; Kumamaru, H.; Ohkawa, Y.; Kubota, K.; Kobayakawa, K.; Yamada, H.; Yokomizo, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Okada, S. Ly6C+ Ly6G- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells play a critical role in the resolution of acute inflammation and the subsequent tissue repair process after spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 2013, 125, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, C.; Schildberg, F.A.; Schurich, A.; Diehl, L.; Hegenbarth, S.I.; Endl, E.; Lacher, S.; Müller, C.E.; Frey, J.; Simeoni, L.; et al. Adenosine regulates CD8 T-cell priming by inhibition of membrane-proximal T-cell receptor signalling. Immunology 2009, 128, e728–e737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, C.; Hu, X.; Weber, R.; Fleming, V.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) during tumour progression. Br. J. Cancer. 2019, 120, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Pan, P.Y.; Li, Q.; Sato, A.I.; Levy, D.E.; Bromberg, J.; Divino, C.M.; Chen, S.H. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schouppe, E.; Mommer, C.; Movahedi, K.; Laoui, D.; Morias, Y.; Gysemans, C.; Luyckx, A.; De Baetselier, P.; Van Ginderachter, J.A. Tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets exert either inhibitory or stimulatory effects on distinct CD8+ T-cell activation events. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 2930–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Zheng, L.; Qi, C. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the tumor microenvironment and their targeting in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer. 2025, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S.E.; Han, H.D.; Hong, K.J.; Kang, T.H.; Park, Y.M. Interactions between tumor-derived proteins and Toll-like receptors. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1926–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tang, H.; Cai, X.; Lin, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. DAMPs in immunosenescence and cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2024, 106-107, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.; Huebener, P.; Schwabe, R.F. Damage-associated molecular patterns in cancer: a double-edged sword. Oncogene 2016, 35, 5931–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apol, Á.D.; Winckelmann, A.A.; Duus, R.B.; Bukh, J.; Weis, N. The Role of CTLA-4 in T Cell Exhaustion in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Viruses 2023, 15, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, O.S.; Zheng, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Attridge, K.; Manzotti, C.; Schmidt, E.M.; Baker, J.; Jeffery, L.E.; Kaur, S.; Briggs, Z.; et al. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science 2011, 332, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Z.; Kim, H.J.; Villasboas, J.C.; Chen, Y.P.; Price-Troska, T.; Jalali, S.; Wilson, M.; Novak, A.J.; Ansell, S.M. Expression of LAG-3 defines exhaustion of intratumoral PD-1+ T cells and correlates with poor outcome in follicular lymphoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 61425–61439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.; Whitehead, T.; Fellermeyer, M.; Davis, S.J.; Sharma, S. The current state and future of T-cell exhaustion research. Oxf. Open Immunol. 2023, 4, iqad006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Liu, G.; Dai, B.; Si, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wazir, J.; Birnbaumer, L.; Yang, Y. Reinvigorating exhausted CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment and current strategies in cancer immunotherapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 156–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catakovic, K.; Klieser, E.; Neureiter, D.; Geisberger, R. T cell exhaustion: from pathophysiological basics to tumor immunotherapy. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengsch, B.; Johnson, A.L.; Kurachi, M.; Odorizzi, P.M.; Pauken, K.E.; Attanasio, J.; Stelekati, E.; McLane, L.M.; Paley, M.A.; Delgoffe, G.M.; et al. Bioenergetic Insufficiencies Due to Metabolic Alterations Regulated by the Inhibitory Receptor PD-1 Are an Early Driver of CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion. Immunity 2016, 45, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odorizzi, P.M.; Pauken, K.E.; Paley, M.A.; Sharpe, A.; Wherry, E.J. Genetic absence of PD-1 promotes accumulation of terminally differentiated exhausted CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancın, B.; Özercan, M.M.; Yılmaz, Y.M.; Uysal, S.; Kumbasar, U.; Sarıbaş, Z.; Dikmen, E.; Doğan, R.; Demircin, M. The correlation of serum sPD-1 and sPD-L1 levels with clinical, pathological characteristics and lymph node metastasis in nonsmall cell lung cancer patients. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 52, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; He, H. Prognostic value of soluble programmed cell death ligand-1 in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 2022, 14, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Picazo, S.E.; Martínez-Morales, P.; Conde-Rodríguez, I.; Reyes-Leyva, J.; Vallejo-Ruiz, V. High serum levels of soluble PD 1 and PD L1 are associated with advanced clinical stages in patients with cervical cancer. Biomed. Rep. 2025, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lan, P.; Wu, G.; Zhu, X.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Zhao, L.; Xu, J.; Xu, M. Prognostic value of soluble programmed death-1 and soluble programmed death ligand-1 in severe traumatic brain injury patients. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Chen, C.; Kong, C.; Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Bai, W.; He, X. Acute Traumatic Brain Injury Induces CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Functional Impairment by Upregulating the Expression of PD-1 via the Activated Sympathetic Nervous System. Neuroimmunomodulation 2019, 26, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Smith, A.; Andreansky, S.; Bracchi-Ricard, V.; Bethea, J.R. Chronic thoracic spinal cord injury impairs CD8+ T-cell function by up-regulating programmed cell death-1 expression. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, L.; Du, T.; Hou, Y.; Fan, W.; Wu, Q.; Yan, H. Enhanced Expression of PD-L1 on Microglia After Surgical Brain Injury Exerts Self-Protection from Inflammation and Promotes Neurological Repair. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 2470–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnerbauer, M.; Beyer, T.; Nirschl, L.; Farrenkopf, D.; Lößlein, L.; Vandrey, O.; Peter, A.; Tsaktanis, T.; Kebir, H.; Laplaud, D.; et al. PD-L1 positive astrocytes attenuate inflammatory functions of PD-1 positive microglia in models of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.J.; Ganta, C.K. Autonomic nervous system and immune system interactions. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, J.; Haurogné, K.; Bacou, E.; Pogu, S.; Allard, M.; Mignot, G.; Bach, J.M.; Lieubeau, B. β2-adrenergic stimulation of dendritic cells favors IL-10 secretion by CD4+ T cells. Immunol. Res. 2017, 65, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; Gálvez, I.; Martín-Cordero, L. Adrenergic Regulation of Macrophage-Mediated Innate/Inflammatory Responses in Obesity and Exercise in this Condition: Role of β2 Adrenergic Receptors. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 2019, 19, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, A.; Suzuki, K. Adrenergic control of lymphocyte trafficking and adaptive immune responses. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 130, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, E.; Olivella, J.C.; Di Napoli, M.; Raihane, A.S.; Divani, A.A. Immune Response in Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 24, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.W.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; Green, P.A.; Sood, A.K. Sympathetic nervous system regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015, 15, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Bautista, M.; Shrestha, S.; Elhasasna, H.; Chaphekar, T.; Vizeacoumar, F.S.; Krishnan, A. Sympathetic signaling facilitates progression of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, D.M.; Fernandes, V.; Lourenço, C.; Carvalho-Maia, C.; Estevão-Pereira, H.; Lobo, J.; Cantante, M.; Couto, M.; Conceição, F.; Jerónimo, C.; et al. Profiling the Adrenergic System in Breast Cancer and the Development of Metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.E.; Kim, H.S.; Won, K.Y.; Kim, G.Y.; Sung, J.Y.; Lim, S.J. Lower Sympathetic Nervous System Density and β-adrenoreceptor Expression Are Involved in Gastric Cancer Progression. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garramona, F.T.; Cunha, T.F.; Vieira, J.S.; Borges, G.; Santos, G.; de Castro, G.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Brum, P.C. Increased sympathetic nervous system impairs prognosis in lung cancer patients: a scoping review of clinical studies. Lung Cancer Manag. 2024, 12, LMT63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.H.; Liu, H.H.; Hsu, S.J.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, D.M.; Cui, J.F; Ren, Z.G.; Chen, R.X. Norepinephrine-stimulated HSCs secrete sFRP1 to promote HCC progression following chronic stress via augmentation of a Wnt16B/β-catenin positive feedback loop. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globig, A.M.; Zhao, S.; Roginsky, J.; Maltez, V.I.; Guiza, J.; Avina-Ochoa, N.; Heeg, M.; Araujo Hoffmann, F.; Chaudhary, O.; Wang, J.; et al. The β1-adrenergic receptor links sympathetic nerves to T cell exhaustion. Nature 2023, 622, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, J.; Dubreil, L.; Tardif, V.; Terme, M.; Pogu, S.; Anegon, I.; Rozec, B.; Gauthier, C.; Bach, J.M.; Blancou. P. β2-Adrenoreceptor agonist inhibits antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guereschi, M.G.; Araujo, L.P.; Maricato, J.T.; Takenaka, M.C.; Nascimento, V.M.; Vivanco, B.C.; Reis, V.O.; Keller, A.C.; Brum, P.C.; Basso, A.S. Beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling in CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells enhances their suppressive function in a PKA-dependent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Shen, S.; Hou, Y. Inflammation and cancer: paradoxical roles in tumorigenesis and implications in immunotherapies. Genes Dis. 2021, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Andoh, A. The Role of Inflammation in Cancer: Mechanisms of Tumor Initiation, Progression, and Metastasis. Cells 2025, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacova, R. Systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: may adipose tissue play a role? Review of the literature and future perspectives. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 2010, 585989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyne, D.M.; Barbe, M.F.; James, G.; Hodges, P.W. Does the Interaction between Local and Systemic Inflammation Provide a Link from Psychology and Lifestyle to Tissue Health in Musculoskeletal Conditions? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.T.; Sun, Z.J. Turning cold tumors into hot tumors by improving T-cell infiltration. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5365–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotoula, V.; Chatzopoulos, K.; Lakis, S.; Alexopoulou, Z.; Timotheadou, E.; Zagouri, F.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Gogas, H.; Galani, E.; Efstratiou, I.; et al. Tumors with high-density tumor infiltrating lymphocytes constitute a favorable entity in breast cancer: a pooled analysis of four prospective adjuvant trials. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 5074–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Li, S.; He, L.; Chen, N. Prognostic implications of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1476365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.P.; Qiu, Q.H.; Chen, L.S.; Luo, X.N.; Lu, Z.M.; Zhang, S.Y.; Chen, S.H. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic marker in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Song, X.; Zeng, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Ding, H. The prognostic value of systemic and local inflammation in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Onco. Targets Ther. 2016, 9, 7177–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurescu, S.; Tomescu, L.; Șerban, D.; Nicolae, N.; Nan, G.; Buciu, V.; Ilaș, D.G.; Cîtu, C.; Vernic, C.; Sas, I. The Prognostic Value of Systemic Inflammation Index in Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Study in Western Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Cai, S.; Zhang, F.; Shao, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tan, F.; Gao, S.; He, J. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is useful to predict survival outcomes in patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2019, 10, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Deng, C.; Wen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Han, H.; Zheng, S.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H. Systemic immune-inflammation index is a stage-dependent prognostic factor in patients with operable non-small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, D.; Ozaka, M.; Matsuyama, M.; Yamada, I.; Takano, K.; Saiura, A.; Ishii, H. Prognostic value of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and level of C-reactive protein in a large cohort of pancreatic cancer patients: a retrospective study in a single institute in Japan. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 45, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.J.; Li, K.Z.; Bai, J.H.; Liang, Z.Q. C-reactive protein/albumin ratio is a prognostic indicator in Asians with pancreatic cancers: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019, 98, e18219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.C.; Rajab, I.M.; Alebraheem, M.; Potempa, L.A. C-Reactive Protein and Cancer-Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 595835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortborg, M.; Edin, S.; Böckelman, C.; Kaprio, T.; Li, X.; Gkekas, I.; Hagström, J.; Strigård, K.; Haglund, C.; Gunnarsson, U.; et al. Systemic inflammatory response in colorectal cancer is associated with tumour mismatch repair and impaired survival. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustenhoven, J. A privileged brain. Science 2021, 374, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, E.A.; Ndode-Ekane, X.E.; Lehto, L.J.; Gorter, J.A.; Andrade, P.; Aronica, E.; Gröhn, O.; Pitkänen, A. Long-lasting blood-brain barrier dysfunction and neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 145, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, H.; Guo, X.; Pluimer, B.; Zhao, Z. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Evidence From Preclinical Murine Models. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könnecke, H.; Bechmann, I. The role of microglia and matrix metalloproteinases involvement in neuroinflammation and gliomas. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 914104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, S.; Yeman Kiyak, B.; Akbayir, R.; Seyhali, R.; Arpaci, T. Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ontiveros, D.G.; Tajiri, N.; Acosta, S.; Giunta, B.; Tan, J.; Borlongan, C.V. Microglia activation as a biomarker for traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSabato, D.J.; Quan, N.; Godbout, J.P. Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, S.A.; Tajiri, N.; Shinozuka, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Grimmig, B.; Diamond, D.M.; Sanberg, P.R.; Bickford, P.C.; Kaneko, Y.; Borlongan, C.V. Long-term upregulation of inflammation and suppression of cell proliferation in the brain of adult rats exposed to traumatic brain injury using the controlled cortical impact model. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e53376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Alvarez-Croda, D.M.; Stoica, B.A.; Faden, A.I.; Loane, D.J. Microglial/Macrophage Polarization Dynamics following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1732–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, M.D.; Xiu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhou, D.; Sein, T.; Vodovoz, S.J.; Wang, D.; Dumont, A.S.; et al. T Cell Involvement in Neuroinflammation After Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Therapeutic Intervention. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglas, M.; Draxler, D.F.; Ho, H.; McCutcheon, F.; Galle, A.; Au, A.E.; Larsson, P.; Gregory, J.; Alderuccio, F.; Sashindranath, M.; et al. Activated CD8+ T Cells Cause Long-Term Neurological Impairment after Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1178–1191.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ji, N.N.; Wang, H.; Hua, J.Y.; Sun, G.L.; Chen, P.P.; Hua, R.; Zhang, Y.M. Domino Effect of Interleukin-15 and CD8 T-Cell-Mediated Neuronal Apoptosis in Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2021, 38, 1450–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xu, C.; Guo, Y.; Gao, S.; Mei, X.; Tian, H. TNF promotes M1 polarization through mitochondrial metabolism in injured spinal cord. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Dai, W.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, W.; Chen, W.; Peng, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, T.; Liu, H.; Zheng, F.; et al. Mechanism and Regulation of Microglia Polarization in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Molecules 2022, 27, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, P.M.A.; Pfister, B.J.; Haorah, J.; Chandra, N. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in the Pathogenesis of Traumatic Brain Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6106–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Li, S.; Dai, S.S. Neutrophils in traumatic brain injury (TBI): friend or foe? J. Neuroinflammation. 2018, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav, K.; Braun, M.; Alverson, K.; Khodadadi, H.; Kutiyanawalla, A.; Ward, A.; Banerjee, C.; Sparks, T.; Malik, A.; Rashid, M.H.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps exacerbate neurological deficits after traumatic brain injury. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax8847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Shi, M; Liu, L; Zuo, Y; Jia, H; Min, X; Liu, X; Chen, Z; Zhou, Y; Li, S; et al. Inhibition of neutrophil extracellular trap formation attenuates NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis via STING/IRE1α pathway after traumatic brain injury in mice. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1125759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, A.M.; Tovar-Y-Romo, L.B.; Yoo, S.W.; Trout, A.L.; Bae, M.; Kanmogne, M.; Megra, B.; Williams, D.W.; Witwer, K.W.; Gacias, M.; et al. Astrocyte-shed extracellular vesicles regulate the peripheral leukocyte response to inflammatory brain lesions. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10, eaai7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.J.; Perry, V.H.; Pitossi, F.J.; Butchart, A.G.; Chertoff, M.; Waters, S.; Dempster, R.; Anthony, D.C. Central nervous system injury triggers hepatic CC and CXC chemokine expression that is associated with leukocyte mobilization and recruitment to both the central nervous system and the liver. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.; Kurwale, N.; Sharma, B.S. Leukocytosis after routine cranial surgery: A potential marker for brain damage in intracranial surgery. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2016, 11, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Bai, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yin, B.; Bai, G.; Zhang, D.; Gan, S.; Sun, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Elevated Serum Levels of Inflammation-Related Cytokines in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Are Associated With Cognitive Performance. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yue, S.; Wang, P.; Wen, B.; Zhang, X. Systemic inflammation in traumatic brain injury predicts poor cognitive function. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Yang, H.; Huang, F.; Fan, W. Systemic inflammation, neuroinflammation and perioperative neurocognitive disorders. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 72, 1895–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, T.; Hara, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Kozaki, S.; Tsunoda, S.; Ihara, H. Cytokine-induced enhancement of calcium-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes mediated by nitric oxide. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 432, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utagawa, A.; Truettner, J.S.; Dietrich, W.D.; Bramlett, H.M. Systemic inflammation exacerbates behavioral and histopathological consequences of isolated traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 211, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, F.; Luo, C.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qian, Z.; Zhu, G.; Lin, J.; Feng, H. Immediate splenectomy decreases mortality and improves cognitive function of rats after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma. 2011, 71, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Cai, J.; Jie, H.; Xu, Y.; Deng, S. Targeting cancer-related inflammation with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Perspectives in pharmacogenomics. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1078766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tołoczko-Iwaniuk, N.; Dziemiańczyk-Pakieła, D.; Nowaszewska, B.K.; Celińska-Janowicz, K.; Miltyk, W. Celecoxib in Cancer Therapy and Prevention - Review. Curr. Drug Targets. 2019, 20, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciotti, E.; Wangensteen, K.J.; FitzGerald, G.A. Aspirin in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 3751–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Lin, L.; Hu, N.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Pei, Y.; Chen, K.; Sun, B. Aspirin ameliorates lung cancer by targeting the miR-98/WNT1 axis. Thorac Cancer 2019, 10, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, C.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Q. Aspirin-targeted PD-L1 in lung cancer growth inhibition. Thorac Cancer. 2020, 11, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftode, C.; Minda, D.; Draghici, G.; Geamantan, A.; Ursoniu, S.; Enatescu, I. Aspirin-Fisetin Combinatorial Treatment Exerts Cytotoxic and Anti-Migratory Activities in A375 Malignant Melanoma Cells. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Dong, Z. Aspirin suppresses breast cancer metastasis to lung by targeting anoikis resistance. Carcinogenesis 2022, 43, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Tang, M.; Gong, W.; Liu, J.; Qin, L. Aspirin Inhibits Brain Metastasis of Lung Cancer via Upregulation of Tight Junction Protein Expression in Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2023, 28, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vunnam, N.; Young, M.C.; Liao, E.E.; Lo, C.H.; Huber, E.; Been, M.; Thomas, D.D.; Sachs, J.N. Nimesulide, a COX-2 inhibitor, sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by promoting DR5 clustering. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2023, 24, 2176692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, A.; Chen, Y. Nimesulide inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells by enhancing expression of PTEN. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Su, B.; Chen, S. A COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide analog selectively induces apoptosis in Her2 overexpressing breast cancer cells via cytochrome c dependent mechanisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Yang, H.; Ye, Z.; Gao, B.; Qian, Z.; Ding, Y.; Mao, Z.; Du, Y.; Wang, W. Celecoxib Augments Paclitaxel-Induced Immunogenic Cell Death in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 15864–15877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo-Cadena, D.X.; Pacheco-Velázquez, S.C.; Vargas-Navarro, J.L.; Padilla-Flores, J.A.; López-Marure, R.; Pérez-Torres, I.; Kaambre, T.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Rodríguez-Enríquez, S. Synergistic celecoxib and dimethyl-celecoxib combinations block cervix cancer growth through multiple mechanisms. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0308233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, M.; Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Zeng, T.; et al. Celecoxib inhibits the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in bladder cancer via the miRNA-145/TGFBR2/Smad3 axis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 44, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellhorn, M.; Haustein, M.; Frank, M.; Linnebacher, M.; Hinz, B. Celecoxib increases lung cancer cell lysis by lymphokine-activated killer cells via upregulation of ICAM-1. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 39342–39356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, W.; Ren, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, X.; Sheng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, R.; Goodin, S.; et al. Celecoxib combined with salirasib strongly inhibits pancreatic cancer cells in 2D and 3D cultures. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egashira, I.; Takahashi-Yanaga, F.; Nishida, R.; Arioka, M.; Igawa, K.; Tomooka, K.; Nakatsu, Y.; Tsuzuki, T.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Kitazono, T.; Sasaguri, T. Celecoxib and 2,5-dimethylcelecoxib inhibit intestinal cancer growth by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Huda, B.; Bhurka, F.; Patnaik, R.; Banerjee, Y. Molecular and Immunomodulatory Mechanisms of Statins in Inflammation and Cancer Therapeutics with Emphasis on the NF-κB, NLRP3 Inflammasome, and Cytokine Regulatory Axes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Eisenhut, M.; Kronbichler, A.; van der Vliet, H.J.; Hong, S.H.; Shin, J.I.; Gamerith, G. Effect of Statin on Cancer Incidence: An Umbrella Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, S.; Druffner, S.R.; Duncan, B.C.; Busada, J.T. Glucocorticoid regulation of cancer development and progression. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1161768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfeist, L.; Galland, L.; Ledys, F.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Limagne, E.; Ladoire, S. Impact of Glucocorticoid Use in Oncology in the Immunotherapy Era. Cells 2022, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherry, E.J. T cell exhaustion. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, L.; Morello, A.; Villena-Vargas, J.; Feng, Y.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Jones, D.R.; Sadelain, M.; Adusumilli, P.S. Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 3130–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Araki, K.; Cardenas, M.A.; Li, P.; Jadhav, R.R.; Kissick, H.T.; Hudson, W.H.; McGuire, D.J.; Obeng, R.C.; Wieland, A.; et al. PD-1 combination therapy with IL-2 modifies CD8+ T cell exhaustion program. Nature 2022, 610, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammeijer, F.; van Gulijk, M.; Mulder, E.E.; Lukkes, M.; Klaase, L.; van den Bosch, T.; van Nimwegen, M.; Lau, S.P.; Latupeirissa, K.; Schetters, S.; et al. The PD-1/PD-L1-Checkpoint Restrains T cell Immunity in Tumor-Draining Lymph Nodes. Cancer Cell. 2020, 38, 685–700.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.M.; Manspeaker, M.P.; Schudel, A.; Sestito, L.F.; O'Melia, M.J.; Kissick, H.T.; Pollack, B.P.; Waller, E.K.; Thomas, S.N. Blockade of immune checkpoints in lymph nodes through locoregional delivery augments cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.A.; Wu, D.C.; Cheung, J.; Navarro, A.; Xiong, H.; Cubas, R.; Totpal, K.; Chiu, H.; Wu, Y.; Comps-Agrar, L.; et al. PD-L1 expression by dendritic cells is a key regulator of T-cell immunity in cancer. Nat. Cancer. 2020, 1, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Guo, J.; Peng, H.; Chen, M.; Fu, Y.X.; et al. PD-L1 on dendritic cells attenuates T cell activation and regulates response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hu, X.; Feng, K.; Gao, R.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Corse, E.; Hu, Y.; Han, W.; et al. Temporal single-cell tracing reveals clonal revival and expansion of precursor exhausted T cells during anti-PD-1 therapy in lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.K.; Okholm, T.L.H.; Jones, K.B.; McCarthy, E.E.; Liu, C.C.; Yee, J.L.; Tamaki, S.J.; Marquez, D.M.; Tenvooren, I.; Wai, K.; et al. Dynamic CD8+ T cell responses to cancer immunotherapy in human regional lymph nodes are disrupted in metastatic lymph nodes. Cell. 2023, 186, 1127–1143.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermannova, O.; Caiado, I.; Ferreira, A.G.; Pereira, C.F. Cell Fate Reprogramming in the Era of Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 714822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Jafarzadeh, N.; Boi, S.; Kundu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Lopez, J.; Nandre, R.; Zeng, P.; Alolaqi, F.; et al. MEK inhibition reprograms CD8+ T lymphocytes into memory stem cells with potent antitumor effects. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurikhin, E.G.; Pershina, O.; Ermakova, N.; Pakhomova, A.; Widera, D.; Zhukova, M.; Pan, E.; Sandrikina, L.; Kogai, L.; Kushlinskii, N.; et al. Reprogrammed CD8+ T-Lymphocytes Isolated from Bone Marrow Have Anticancer Potential in Lung Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurikhin, E.G.; Pershina, O.; Ermakova, N.; Pakhomova, A.; Zhukova, M.; Pan, E.; Sandrikina, L.; Widera, D.; Kogai, L.; Kushlinskii, N.; et al. Cell Therapy with Human Reprogrammed CD8+ T-Cells Has Antimetastatic Effects on Lewis Lung Carcinoma in C57BL/6 Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skokos, D.; Waite, J.C.; Haber, L.; Crawford, A.; Hermann, A.; Ullman, E.; Slim, R.; Godin, S.; Ajithdoss, D.; Ye, X.; et al. A class of costimulatory CD28-bispecific antibodies that enhance the antitumor activity of CD3-bispecific antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaaw7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otano, I.; Azpilikueta, A.; Glez-Vaz, J.; Alvarez, M.; Medina-Echeverz, J.; Cortés-Domínguez, I.; Ortiz-de-Solorzano, C.; Ellmark, P.; Fritzell, S.; Hernandez-Hoyos, G.; et al. CD137 (4-1BB) costimulation of CD8+ T cells is more potent when provided in cis than in trans with respect to CD3-TCR stimulation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Q.; Han, M.; Guo, Q.; Yan, F.; Wang, M.; Ning, Q.; Xi, D. Strategies to reinvigorate exhausted CD8+ T cells in tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1204363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Lee, R.P.; Yazigi, E.; Atta, L.; Feghali, J.; Pant, A.; Jain, A.; Levitan, I.; Kim, E.; Patel, K.; et al. Soluble PD-L1 reprograms blood monocytes to prevent cerebral edema and facilitate recovery after ischemic stroke. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 116, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.M.; Choi, J.; Routkevitch, D.; Pant, A.; Saleh, L.; Ye, X.; Caplan, J.M.; Huang, J.; McDougall, C.G.; Pardoll, D.M.; et al. PD-1+ Monocytes Mediate Cerebral Vasospasm Following Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2021, 88, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergold, P.J. Treatment of traumatic brain injury with anti-inflammatory drugs. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Malik, R.; Singh, G.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Mohan, S.; Albratty, M.; Albarrati, A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Pathogenesis and management of traumatic brain injury (TBI): role of neuroinflammation and anti-inflammatory drugs. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhuang, J.; He, X.; Wang, S.; Lin, W. Dexmedetomidine Mitigates Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation through Upregulation of Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 in a Rat Spinal Cord Injury Model. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 2591–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Chen, Y.; Luan, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y. Dexmedetomidine reduces inflammation in traumatic brain injury by regulating the inflammatory responses of macrophages and splenocytes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 2323–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, D.; Cakir-Aktas, C.; Uzun, S.; Soylemezoglu, F.; Mut, M. Tailored Therapeutic Doses of Dexmedetomidine in Evolving Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurocrit. Care. 2022, 36, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Xu, X.; Wu, Y.G.; Lyu, L.; Zhou, Z.W.; Zhang, J.N. Dexmedetomidine attenuates traumatic brain injury: action pathway and mechanisms. Neural. Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Sui, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L. The neuroprotective effect of dexmedetomidine and its mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 965661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celorrio, M.; Shumilov, K.; Payne, C.; Vadivelu, S.; Friess, S.H. Acute minocycline administration reduces brain injury and improves long-term functional outcomes after delayed hypoxemia following traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergold, P.J.; Furhang, R.; Lawless, S. Treating Traumatic Brain Injury with Minocycline. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1546–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meythaler, J.; Fath, J.; Fuerst, D.; Zokary, H.; Freese, K.; Martin, H.B.; Reineke, J.; Peduzzi-Nelson, J.; Roskos, P.T. Safety and feasibility of minocycline in treatment of acute traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2019, 33, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Qian, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, D.; Su, W.; Wang, P.; Guo, L.; Quan, W.; An, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. A Three-Day Consecutive Fingolimod Administration Improves Neurological Functions and Modulates Multiple Immune Responses of CCI Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 8348–8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.G.; Miguel, Z.D.; Watkins, L.R.; Maier, S.F. Prior exposure to glucocorticoids sensitizes the neuroinflammatory and peripheral inflammatory responses to E. coli lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010, 24, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Arango, M.; Balica, L.; Cottingham, R.; El-Sayed, H.; Farrell, B.; Fernandes, J.; Gogichaisvili, T.; Golden, N.; Hartzenberg, B.; et al. Final results of MRC CRASH, a randomised placebo-controlled trial of intravenous corticosteroid in adults with head injury-outcomes at 6 months. Lancet 2005, 365, 1957–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, A.T.; Brophy, G.M.; Gilman, C.B.; Alves, O.L.; Robles, J.R.; Hayes, R.L.; Povlishock, J.T.; Bullock, M.R. Safety and tolerability of cyclosporin a in severe traumatic brain injury patients: results from a prospective randomized trial. J. Neurotrauma. 2009, 26, 2195–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flygt, J.; Ruscher, K.; Norberg, A.; Mir, A.; Gram, H.; Clausen, F.; Marklund, N. Neutralization of Interleukin-1β following Diffuse Traumatic Brain Injury in the Mouse Attenuates the Loss of Mature Oligodendrocytes. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 2837–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, A.; Guilfoyle, M.R.; Carpenter, K.L.H.; Pickard, J.D.; Menon, D.K.; Hutchinson, P.J. Recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist promotes M1 microglia biased cytokines and chemokines following human traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016, 36, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, A.; Emami, M.; Asadipour, E.; Kasirzadeh, S.; Rouini, M.R.; Najafi, A.; Heshmat, R.; Abdollahi, M.; Mojtahedzadeh, M. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of metformin in severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 1988–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 06 November 2025).

- Zhong, H.; Feng, Y.; Shen, J.; Rao, T.; Dai, H.; Zhong, W.; Zhao, G. Global Burden of Traumatic Brain Injury in 204 Countries and Territories From 1990 to 2021. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 68, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylsalicylic acid | Chemoprevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in high-risk patients | [119] |

| Inhibition of lung cancer cell growth (A549, H1299) in vitro | [120,121] | |

| Modulation of PD-L1 expression in vitro | ||

| Decreased survival of melanoma cells line A-375 in vitro | [122] | |

| Inhibition of breast cancer metastasis in vivo | [123] | |

| Enhancement of apoptosis of breast cancer cells in vitro | ||

| Inhibition of lung cancer metastasis | [124] | |

| Nimesulide | Enhancement of TRAIL-induced apoptosis of Panc1 cells in vitro | [125] |

| Inhibition of Panc1 cell proliferation in vitro | [126] | |

| Enhancement of apoptosis by Panc1 in vitro | ||

| Reduction of VEGF expression by tumor cells | ||

| Inhibition of proliferation of breast cancer cells (SK-BR-3, BT-474 and MDA-MB-453) in vitro | [127] | |

| Celecoxib | Enhancement of the immune response in triple-negative breast cancer (in combination with paclitaxel) | [128] |

| Inhibition of cervical cancer cell proliferation (HeLa, SiHa cell lines) | [129] | |

| Inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition | [130] | |

| Stimulation of LAK-mediated lysis of lung cancer cells | [131] | |

| Decreased viability of Panc1 cells in vitro | [132] | |

| Inhibition of proliferation and stimulation of apoptosis in colon cancer cells (HCT-116) | [133] |

| Group | Examples | Mechanisms of influence on neuroinflammation |

|---|---|---|

| Statins | Atorvastatin Lovastatin Simvastatin |

Suppression of microglial activation |

| Reduction in the proinflammatory cytokines production | ||

| Suppression of TLR4, NF-κB, IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and ICAM-1 expression | ||

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug | Indomethacin Ibuprofen Celecoxib Meloxicam Nimesulide |

↓ IL-1β production Prostaglandin synthesis inhibition |

| TNF blockers | Etanercept | Reduce the level of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | Rolipram (only for experimental studies) Roflumilast |

↓ IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and NLRP3 level |

| Anti-IL-1 antibodies | Anakinra | ↓ the level of IL-1β |

| ↑ the activity of antioxidant systems (superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase) | ||

| Antibiotics | Minocycline | ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, CCL8, CXCL4 |

| Inhibition MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways | ||

| Immunosuppressants | Fingolimod | ↓ severity of blood-brain barrier impairment |

| ↓ cerebral edema | ||

| Modulation of immune cell functions | ||

| Others | N-Acetylcysteine | Reduction levels of IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6 |

| ↓ NF-κB expression | ||

| ↓ cerebral edema | ||

| ↓ severity of blood-brain barrier impairment | ||

| Metformin | ↓ IL-8 production | |

| ↓ NF-κB pathway activity | ||

| ↓ microglial activation |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | Neuroinflammation | Traumatic Brain Injury + Neuroinflammation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | |||

| Recruiting | 385 | 64 | 6 |

| Active | 79 | 7 | 3 |

| Completed | 1,117 | 65 | 7 |

| Terminated | 171 | 14 | 1 |

| Phase | |||

| I | 108 | 26 | 4 |

| II | 232 | 33 | 9 |

| III | 129 | 5 | 1 |

| IV | 82 | 14 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).