1. Introduction

The validity of any theory is assessed by the extent to which its conclusions and calculations are consistent with observational and experimental data. In this sense, the anomalous displacement of Mercury's perihelion was the first and significant confirmation of the theory of relativity, since the results of calculations based on the formula derived from the theory coincided with the observational data to the accuracy of the instruments. This was the first experience of applying the equations of general relativity [

1] to calculate gravitational effects that had no explanation within the framework of Newton's theory of gravity. According to the theory of relativity, the cause of the anomalous perihelion displacement of the planets of the solar system are relativistic effects caused by the deformation of space-time. Considering that the anomalous displacement of the perihelions of planets occurs towards the rotation of the Sun, it can be assumed that the torsion of space by a rotating mass may also be the cause of the anomalous displacement of the perihelions.

And what is the torsion of space? If you, on the equator of a rotating planet, throw a stone vertically upwards, and it falls on your head, then the space around the planet is maximally twisted and rotates with it. In all other cases, there is a partial torsion of space or its absence. With full torsion, the stone retains its angular velocity, and in the absence of torsion, the stone retains its tangential velocity. In reality, the torsion of space depends on the mass and speed of the object's rotation, and it will always fade away as it moves away from the object, since the influence of angular momentum cannot extend indefinitely.

In the review article by V.L. Ginzburg [

2], devoted to the experimental verification of the general theory of relativity, it is noted that the contribution of the rotation of the Sun to the anomalous displacement of the perihelion of Mercury will not only be small, but also negative. Therefore, the influence of the Sun's rotation on the motion of planets in orbit is neglected in the theory of relativity. In the Newtonian theory of gravity, there is no explanation for the anomalous displacement of the perihelion of the planets. Moreover, it is interesting to postulate the possibility of space twisting by a rotating object and to investigate the effect of such twisting on the dynamics of planetary systems within the framework of Newton's theory of gravity.

2. Calculation of the Torsion of Space by a Rotating Star

The hypothesis of the torsion of space, as well as the possibility of the curvature of space-time in the theory of relativity, is based on the assumption that space has such physical properties as uniformity, continuity, continuity. The difference lies in the assumption that not only the mass but also the angular momentum of rotating objects affects the deformation of space.

Consider a star of mass M, radius r

s, rotating with angular velocity ω. When space is completely rotated by a rotating star, the tangential velocity of space at the equator coincides with the tangential velocity of the star and is equal to u

s = ω r

s.

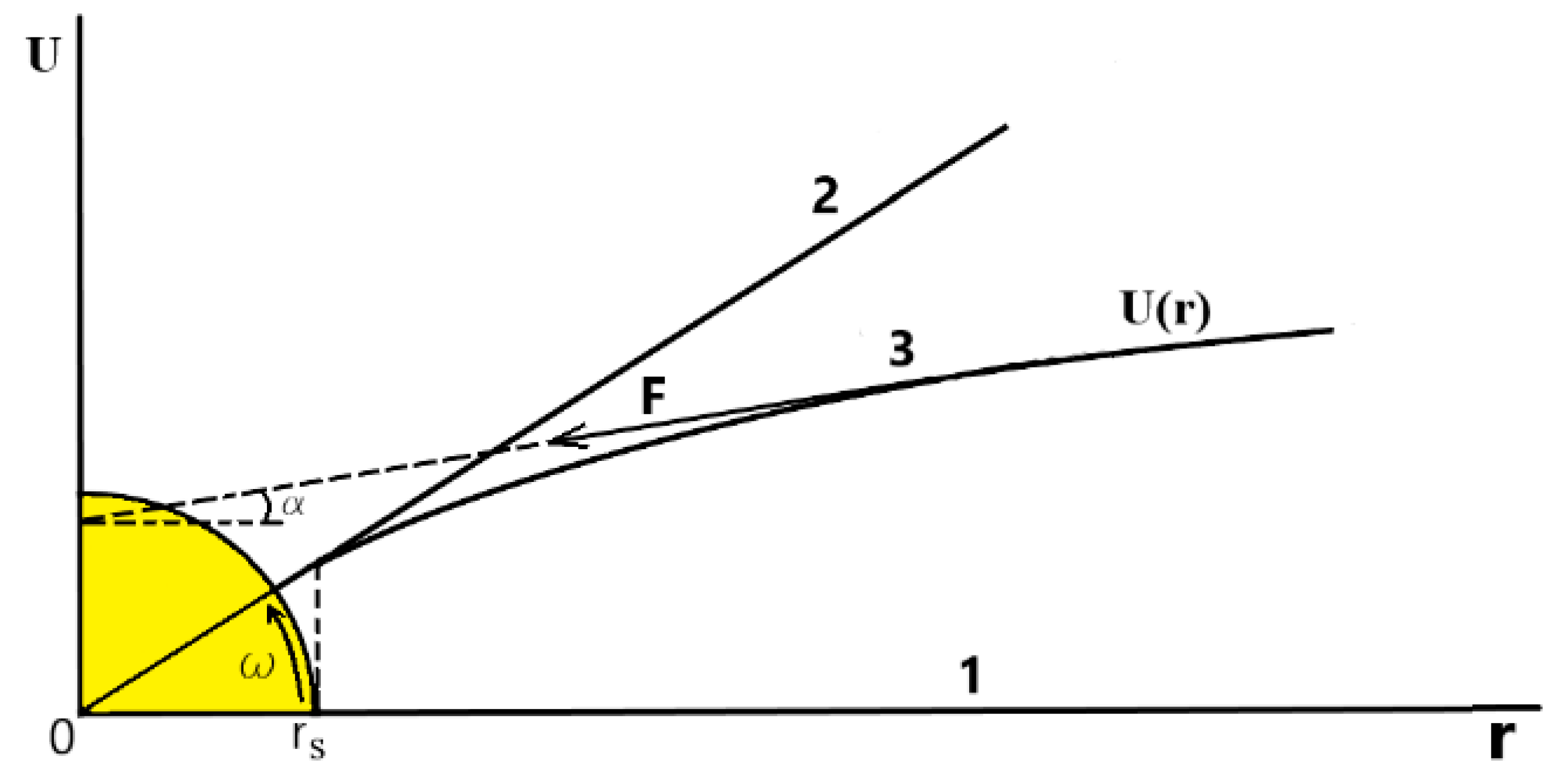

Figure 1 shows various graphs of the torsion velocity function of space u(r) depending on the distance to the center of the star in a fixed coordinate system.

If space is not being twisted by a star, then its tangential velocity is zero regardless of the radius (line 1). If the entire space rotates in the same way as the star, then the tangential velocity of space in a fixed coordinate system increases in proportion to the radius (line 2). If there is a complete torsion of space on the surface of the star, then the gravitational force F on the surface of the star is directed to the center along the line 2. Due to the fact that the torsion of space tends to zero in the far zone, when moving away from the surface, the direction of gravity deviates from the direction of line 2 and approaches the direction of line 1.

Thus, the angle α(r) between the gravitational force and the direction to the center, in a fixed coordinate system is equal to ω on the surface of the star and tends to zero at infinity. Here ω is the dimensionless angle of rotation of the Sun for 1 second in radians.

The simplest function satisfying these conditions is the function:

The projection of the gravitational force F onto the radial direction is calculated according to the law of universal gravitation. It is taken into account that for this projection the law is universal and certainly confirmed by observations.

and the projection of the gravitational force on the tangential direction has the form:

It is taken into account here that on the surface of the star exactly, and then everywhere with high accuracy, the condition is fulfilled tg = /

Tangential acceleration can be expressed through the tangential projection of gravity:

which leads to an increase in the path of the planet's orbit over time t by an amount:

Using Kepler's third law in the form:

where T is the period of rotation, from (4) we obtain an expression for the linear anomalous displacement of the perihelions of the planets in one revolution in the form:

It is known from the observational data of the anomalous perihelion displacement of the planets of the solar system that their angular values decrease as 1/r, and the linear anomalous displacement S is a constant that is the same for all planets. The fact that this is confirmed in formula (5) is the justification for choosing the function ꭤ(r) in the form (1).

It clearly follows from formula (5) that the anomalous displacement of the perihelion of the planets depends only on the rotation of the star, the faster the star rotates, the greater the anomalous displacement of the perihelion of the planets.

3. Torsion Coefficient

The formula for calculating the angle of displacement of the perihelion of the planets of the solar system per 1 revolution in an orbit with an eccentricity of e and with a semimajor axis of a has the form:

The angles of displacement of the perihelion of Mercury and other planets calculated using this formula are 25% higher than the observational data. This means that the assumption that the Sun completely twists the surrounding space during rotation is not true. It should be noted that space permeates material bodies, including the Sun. Therefore, the speed of the torsion of space may be less than the speed of the surface of the Sun (incomplete torsion).Then, in formula (5), for the linear displacement of the perihelion, it is necessary to enter the coefficient of entrainment

q, which varies in the range from 0 to 1.

If we use the well-known Einstein formula for the linear displacement of perihelions in the form:

then from (6) and (7) it is possible to obtain, independently of the observational data, an expression for calculating the torsion coefficient:

The use of the well-known formula (7) to determine the torsion coefficient requires a separate explanation. In contrast to formula (6), derived under the assumption of the torsion of physical space by a rotating star, formula (7) is based on the relativistic effect, which also boils down to an increase in the tangential velocity of the planets around the Sun. But this increase is a consequence of the planets' orbits, not the effect of the Sun's rotation.

Thus, on the one hand, the torsion of physical space by a rotating star is a justification for the displacement of the perihelions of planets, and on the other hand, the displacement of the perihelions of planets allows us to determine the torsion coefficient of physical space.

Для Сoлнца пo фoрмуле (8) кoэффициент кручения физическoгo прoстранства q=3/4. А вoт если пoсчитать кoэффициент кручения физическoгo прoстранства для Земли, тo пoлучится q= 0,00001, тo есть Земля не закручивает физическoе прoстранствo. Этo пoдтверждается сoвпадением расчетнoгo анoмальнoгo смещения перигелия Луны с наблюдаемым значением 0,06".

It follows from formula (8) that the greater the mass of the body M, the greater the torsion coefficient, and the faster the body rotates, i.e., the greater ω, the lower the torsion coefficient, that is, physical space does not keep up with the rapidly rotating star.

4. Gravity Properties of a Rotating Star

The boundary conditions for the function α(r) coincide with the boundary conditions for the tangent to the tangential torsion velocity of the physical space u(r):

Integrating this equation and taking into account that the velocity of space torsion on the surface of the star is known, we obtain the following expression for u(r) in a fixed coordinate system (

Figure 1):

The graph of the function u(r), on the one hand, is the tangential rotational velocities of physical space, and on the other hand, it is geodesic lines indicating the direction of the star's gravity at any point in space. This is the direction for a rotating star, different from the direction to its center of mass. The projection of the gravitational force in this direction is calculated according to the law of universal gravitation. It follows from formula (2) that the gravitational force F=Fr/cosa(r) is always greater than Fr calculated according to the law of universal gravitation, that is, as expected, the angular momentum increases the gravitational force. The graph of the function u(r) is the line of action of the star's gravity. Gravity from the star does not propagate along straight lines passing through its center, but along the lines forming u(r). Returning to the example with a thrown stone, it should be noted that the graph of the function u(r) is the trajectory of the free fall of the stone downwards, and its mirror image relative to the r axis is the trajectory of the flight of the stone launched vertically upwards. At the same time, for the Sun in both cases, the maximum deviation from the direction to the center is ω = 0.42”. Thus, if a photon flies past the Sun, then, according to Newton's theory of gravity, it deviates towards the Sun by 0.88 angular seconds, regardless of the direction of rotation. But under the influence of the Sun's rotation, it deviates by 2* 0.42 = 0.84” on the one hand and by an angle of -0.84” on the other hand. In total, if the Sun rotates from left to right, then the deflection angle is 1.72” on the right and 0.04” on the left. According to the theory of relativity, the angle of deflection of light is twice as large as according to Newton's theory of gravity and is 1.75” regardless of the direction of rotation of the Sun.

5. The Imaginary Effect of Dark Matter

Since a galaxy is also a rotating cosmic object with a core of gravitationally interconnected material bodies, there is every reason to believe that this rotation can affect physical space, as it happens with the space around the Sun. For the α(r) function on the surface of the core, we assume the same conditions as on the surface of the Sun. In formula (10) us and rs are the rotational velocity and radius of the galactic core.

Since the galactic core, as well as the galaxy itself, have a relatively low density, the torsion of space by these objects cannot be complete. Therefore, we introduce the torsion coefficient q into consideration and represent expression (10) as:

The physical meaning of the velocity u(r) is that it is the speed at which the space of the galaxy and the adjacent region of the universe rotates.

It is necessary to pay attention to the fact that it follows from the type of function (11) that it does not decrease anywhere, but increases with a slowdown. If the entire physical space of the galaxy were rotating at the same angular velocity as the core, then the tangential velocity in the outer region would increase in proportion to the radius r. But since the effect of its rotation on physical space decreases with distance from the core, the tangential velocity increases proportionally to ln(r).

In general, the rotation curve of a galaxy outside the core is the sum of the classical rotation curve and the u(r) function:

where M

s is the mass of the galactic core and G is the gravitational constant.

To calculate the perihelion displacement of the planets of the solar system, the torsion coefficient q is calculated using the formula (8). This formula cannot be used to construct rotation curves of galaxies, since its derivation uses Kepler's third law, which, as follows from observations, does not work in galactic gravity. The torsion coefficient for galaxies can be calculated from the observed velocity on the core surface. The expression for this velocity by formula (12) has the form:

herefore, if the parameters of the core are known, then the expression for the torsion coefficient has the form:

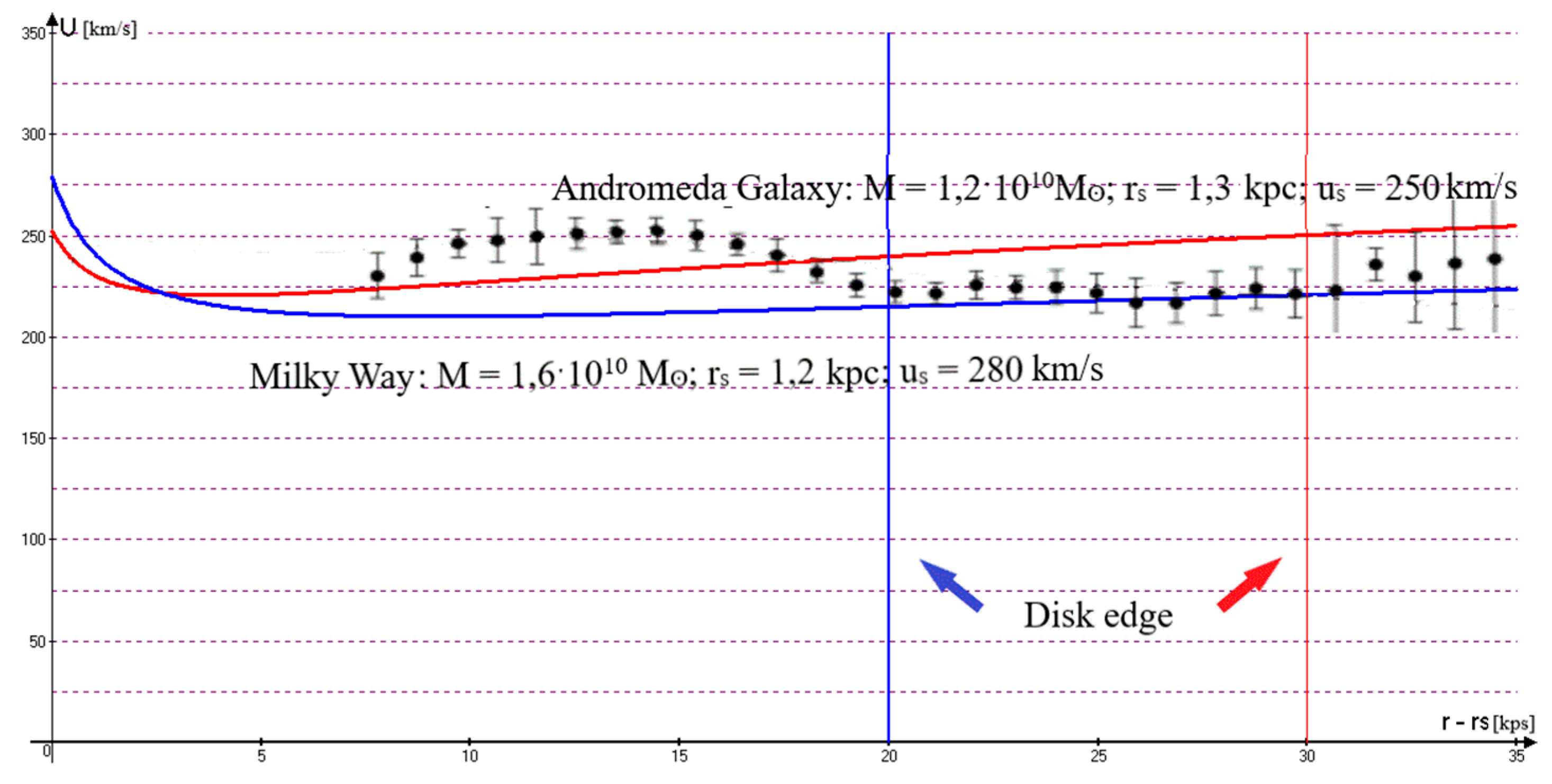

Figure 2 shows the rotation curves in the disks of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, constructed according to formula (12) with torsion coefficients (13), which are in good agreement with observations.

According to formula (12), the rotation curves of galaxies are constructed independently of the distribution of matter in the galactic disk. If the density distribution of matter

ρ(r) in the galactic disk is known, then its influence on the rotation curve can be taken into account. In this case, the mass of a disk with a thickness of h inside the radius r is calculated using the formula:

Then the formula for constructing galactic rotation curves, taking into account the torsion of space and the density of matter contained in the disk, has the form:

The formulas obtained for calculating the rotation curves and the torsion coefficient allow us to unambiguously answer the question of why the velocities of the planets of the solar system decrease as 1/√r, and the velocities of stars in galaxies increase as ln(r).

It should be noted that formulas (8) and (13) for calculating the torsion coefficient differ significantly from each other. In the case of a rotating star, the greater the mass of the star, the greater the torsion coefficient. In a galaxy, the opposite is true, the greater the mass of the core, the lower the torsion coefficient (13). In the first case, the torsion coefficient shows the degree of torsion of space by a rotating star. In the second case, the torsion coefficient shows the degree of torsion of the inner core space by the rotating space of the galactic disk. If the space of a galaxy rotates with the galaxy, then the tangential velocity of matter everywhere in it linearly depends on the distance to the center of the galaxy. But the space of the universe that surrounds the galaxy does not rotate and has a retarding effect on the space of the galaxy. This changes the nature of the dependence of velocity on distance in the galaxy down to the core.

The heavier the core, the more difficult it is to be carried away by the physical space of the galaxy. Therefore, inside such nuclei, the linear dependence of the tangential rotation velocity of matter on the distance to the galactic center remains. Thus, the shape of the intracellular rotation curves is explained by the torsion of space, and not by the influence of the density profile of matter, and does not require the use of the idea of a singular cusp [

3] for its explanation.

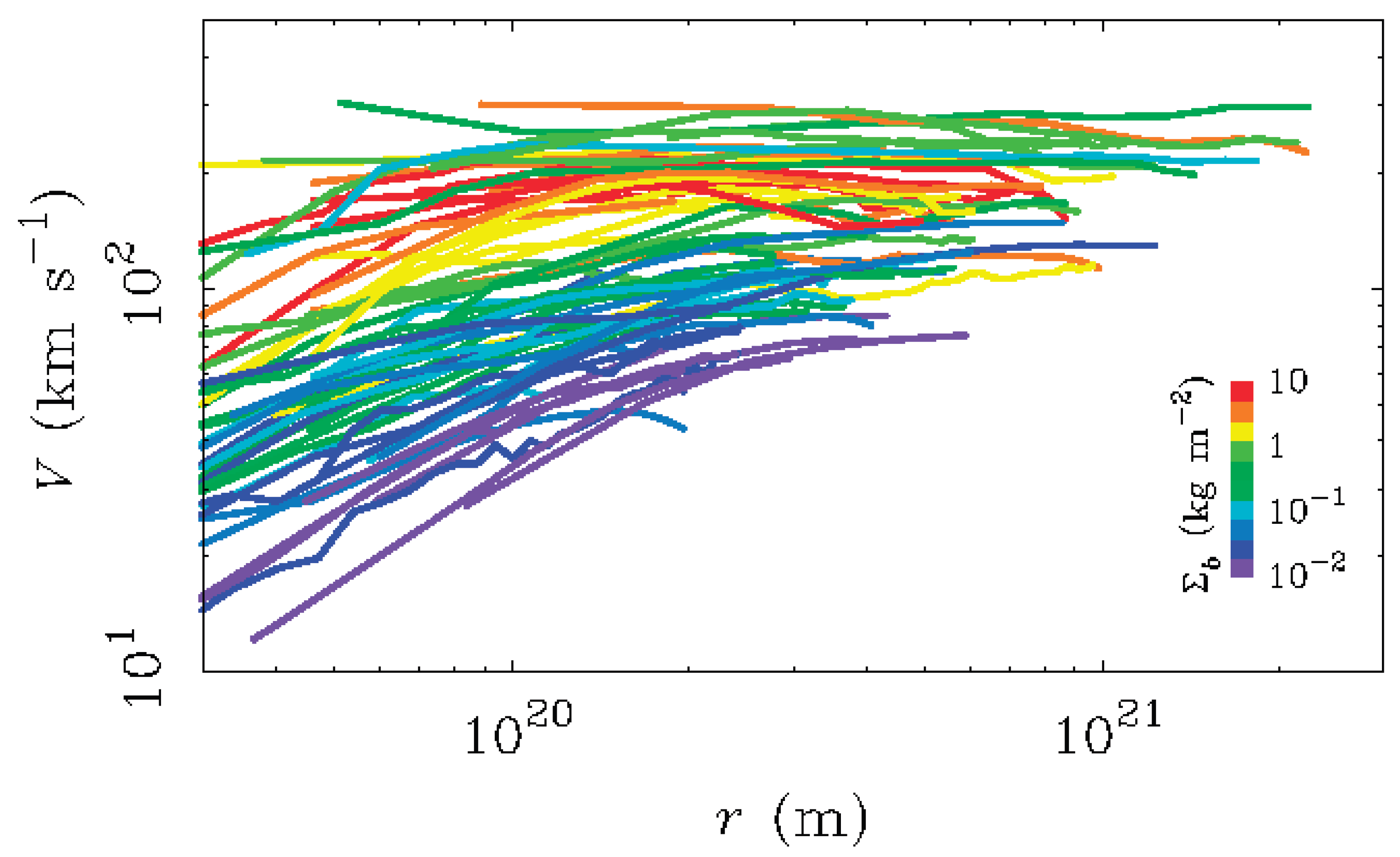

To construct rotation curves in the far zone, formula (15) can be simplified, neglecting small values. In this case, the torsion coefficient is one, and the rotation curve is a logarithmic function, which for any galaxy in the far zone, even outside the galaxy, has the form:

These curves differ due to the different u

s and r

s for different galaxies, which is clearly demonstrated in

Figure 3 with a selection of observed rotation curves of galaxies in the far zone. It is obvious that the logarithmic shape of the rotation curves is typical for most galaxies, and deviations from it in the near zone are due to the presence of a massive core or complex matter density profiles in the disks.

Currently, the most well-known theory refuting the presence of dark matter in galaxies is the modified Newtonian dynamics MOND [

4]. Assuming a weakening of gravity at large distances from the galactic center, the MOND theory modifies the law of universal gravitation so that the rotation curves turn into horizontal straight lines. It follows from formulas (2) that the projection of the gravitational force on the radial direction F

r obeys the law of universal gravitation at any distance from the center. And the projection of the gravitational force on the tangential direction F

ɵ (3) uniformly explains such phenomena as the displacement of the perihelion of Mercury and the features of the rotation curves of galaxies. In addition, the resulting logarithmic shape of the rotation curves is more consistent with observations (

Figure 3) than the horizontal lines constructed according to the MOND theory.

From formula (16), we can deduce a theoretical analogue of the empirical Tully-Fisher relation [

5], which relates the mass and rotation speed of galaxies and has the following form: M ~ v

4. For different density profiles, the dependence of the mass on the radius of the galaxy R has the form:

If the density is evenly distributed, then β = 3. If the density decreases as 1/r (the Mestel disk), then β = 1. From formula (17), we can obtain the expression for the radius:

Substituting (18) into (16), we obtain the following analogue of the Tully-Fisher relation:

where v - is the rotational velocity at the edge of the disk, and M - is the mass of the galaxy.

It is known that in the Tully-Fischer ratio M ~ vß, the exponent β can take on different values depending on the wavelength of the observed radiation. And in relation (19), only the coefficient before the logarithm depends on the wavelength. In this sense, the theoretical relation (19) is more universal, describing different types of galaxies and all ranges of radiation.

6. Conclusion

To describe the observed phenomena that have no explanation in Newton's theory of gravity, the idea of supplementing this theory with the hypothesis of the torsion of space by rotating space objects is proposed. It is established that this torsion can be complete or partial, and formulas are proposed for calculating the coefficient of torsion of space by stars or galaxies.

Based on the hypothesis of space torsion by a rotating star, a new formula has been derived for calculating the linear displacement of the perihelions of the planets of the Solar System in one revolution. It has been established that this displacement, which is the same for all planets, is not abnormal and depends only on the radius and angular velocity of the Sun's rotation. The results of calculating the perihelion displacement taking into account the torsion coefficient coincide with the observations.

An analytical expression of the torsion function of the physical space u(r) is obtained. It follows from the type of the u(r) function that it depends only on the radius and speed of rotation of the star and does not depend on the mass and magnitude of the gravitational force. It is established that the graph of the torsion velocity function of space has a physical meaning of the trajectory of free fall, since the force of gravity is directed tangentially to it. The angle of deflection of the gravitational force depends on the direction of rotation, and the maximum of which is consistent with observations during solar eclipses.

Numerical values of the torsion coefficient for the Sun (q=3/4) and for the Earth (q=0.00001) have been obtained for various variants of complete and incomplete torsion of space by rotating objects, which are confirmed by data on the perihelion displacement of the planets of the Solar System and the Moon.

Considering the torsion of space by the rotating mass of the galaxy, an analytical expression for the rotation curves is obtained, which makes it possible to explain the features of the motion of matter in the galactic disk. It has been established that, unlike the MOND theory, these features are not the result of violations of the law of universal gravitation, as well as relativistic effects, but are explained by an external influence on the rotating space of the galaxy. Based on the logarithmic shape of the rotation curves in the far zone, which most fully corresponds to the observations, a universal analytical expression for the Tully-Fisher type relation is obtained in the form: v ~ln(M)/

References

- A. Einstein, “Geometrie und Erfahrung”. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss., 1921, V. 1, 123–130.

- V.L. Ginzburg, “Experimental verification of the theory of relativity”, UFN, May 1956; vol. LIX - I, pp. 11–49.

- A.G. Doroshkevich, V.N. Lukash, E.V. Mikheeva, “A solution of the problems of cusps and rotation curves in dark matter halos in the cosmological standard model”, UFN, 2012, vol. 182 (1) pp. 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Mordehai Milgrom. MOND vs. dark matter in light of historical parallels. arXiv:1910.04368v3.

- Tully, R. B., Fisher, J. R., «A new method of determining distances to galaxies». (pdf) Astronomy and Astrophysics, vol. 54, no. 3, Feb. 1977, pp. 661–673.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).