1. Introduction

The nature of time remains one of the most persistent conceptual challenges in theoretical physics. In quantum mechanics, time is introduced as an external classical parameter that governs unitary evolution, while in general relativity, it is part of a dynamical four-dimensional geometry whose curvature determines how clocks tick. These incompatible roles hinder progress toward a unified description of quantum gravity and continue to fuel the debate over whether time is fundamental, emergent, geometric, or informational in origin. Building on the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework [

1] and the Geometry-Information Duality (GID) formulation [

2], this work develops an informational representation of time based on local gradients of stored information. The resulting construction provides a mechanism by which temporal direction and temporal asymmetry arise from properties of an underlying informational substrate.

1.1. Motivation

In quantum theory, the Schrödinger equation

treats the temporal parameter

t as external to the quantum state. Time is not encoded within the Hilbert space and does not correspond to an observable. In general relativity, by contrast, time is inseparable from space: it is one component of the metric

, and its passage depends on curvature. When these two frameworks are combined in canonical quantum gravity, the temporal parameter disappears entirely. The Wheeler-DeWitt equation

contains no explicit time, producing the well-known frozen-formalism problem [

3,

4,

5].

The Quantum Memory Matrix provides a way to reinterpret this tension by shifting focus from geometric evolution to informational evolution. In the QMM, spacetime is modeled as an array of finite-capacity memory cells, each storing quantum imprints of local interactions [

1]. The sequence of imprint events across this network defines an intrinsic ordering of physical processes. Because these imprints encode irreversible information deposition, their accumulation introduces an emergent temporal structure. Time becomes an ordering of informational updates rather than an externally imposed coordinate. This perspective differs fundamentally from earlier approaches in which time emerges from correlations among subsystems. While some prior formulations introduced informational or entropic potentials for geometric dynamics (for example, [

19]), the present work develops a field-theoretic representation of time as a gradient of stored information within a discrete quantum memory substrate.

1.2. The Key Idea

The central idea of this work is that the informational content

defines a local temporal direction through its gradient. The temporal field

captures the rate and orientation of information change across the QMM. Instead of a universal temporal axis, the universe contains a distribution of informational directions that encode how each region evolves relative to its neighbors. Time is thus modeled as a vector field living on an informational manifold.

The arrow of time arises as a consequence of informational asymmetry. Since the QMM stores imprints irreversibly, tends to increase, and its gradients define a preferred orientation for updates. Informational curvature, measured by the second derivative of , determines how strongly temporal direction changes across space. Regions of high informational curvature experience temporal anisotropy, a phenomenon that parallels gravitational time dilation but originates from information density rather than from geometric curvature.

This framework distinguishes between chronological time, which corresponds to geometric proper time in spacetime, and navigational time, which measures the progression of an observer through the informational manifold that underlies spacetime. Chronological time tracks motion within spacetime, while navigational time tracks motion through the informational substrate that gives rise to it.

1.3. Relation to Prior Work

The informational-time formalism connects to several established approaches while introducing an essential conceptual shift. The block-universe view treats all events as part of a static four-dimensional manifold. The Page-Wootters mechanism and relational interpretations of quantum mechanics explain temporal ordering through correlations among subsystems rather than through an external parameter [

6,

7,

8]. Barbour’s timeless configuration space likewise replaces dynamical evolution with correlations among static configurations [

9]. Entropic and emergent-spacetime models [

10,

11] relate geometry to statistical behavior of microscopic degrees of freedom.

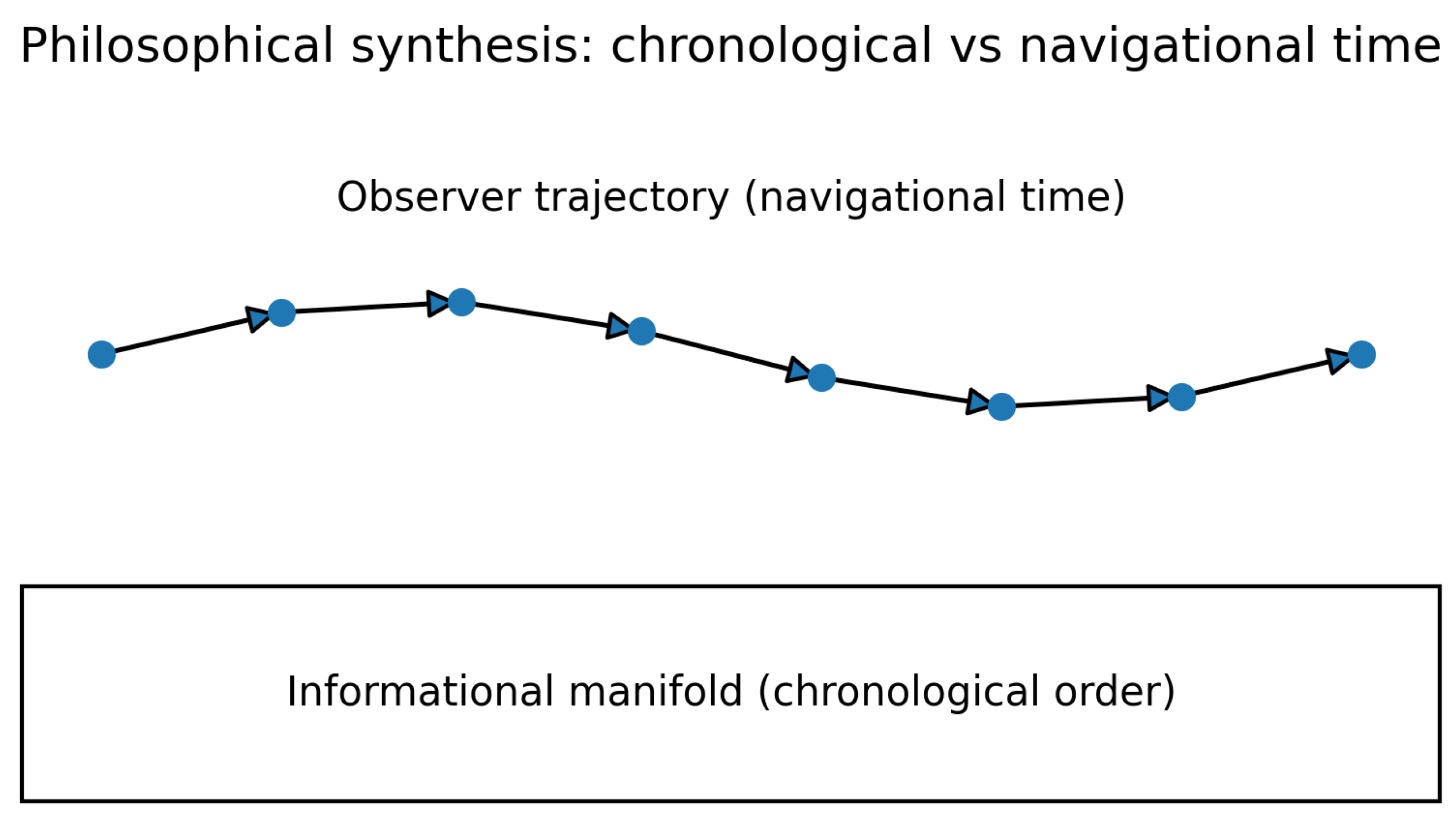

The formulation developed here differs in that it introduces a physically defined informational field whose gradients determine local temporal direction. Time becomes a property of the distribution of stored information rather than a correlation label or coordinate. Every event is stored as an informational imprint, and observers traverse gradients in this informational manifold rather than a universal time coordinate. In this way, chronology, causality, and entropy arise from a common informational origin. A conceptual illustration of this unification is shown in

Figure 1.

2. The Quantum Memory Matrix Framework (Summary)

The Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) formalism models spacetime as an informational substrate in which physical interactions are recorded as discrete, localized imprints. Each elementary four-volume is represented by a finite-capacity Hilbert cell that stores quantum information describing all processes within its causal domain. Curvature, causal structure, and the apparent passage of time emerge as collective statistical effects of how information is written, propagated, and redistributed across this network. The QMM thus provides a unified perspective in which quantum mechanics, general relativity, and thermodynamics arise from a single informational principle: geometry reflects the structure of information storage and transfer [

1,

2,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

2.1. Spacetime as a Lattice of Quantum Memory Cells

In the QMM framework, spacetime is discretized into a set of Planck-scale four-volumes, each represented by a quantum memory cell

. Every cell carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

, where the dimensional bound is fixed by the covariant entropy bound [

18]:

Here

is the area of the cell’s causal boundary and

is the Planck length. Although each QMM cell is a four-dimensional region, the information bound depends on its

two-dimensional null screen, which is the surface across which lightlike information flows. This is consistent with holographic bounds and clarifies why the imprint operator couples to a codimension-two boundary rather than to the full

-dimensional cell.

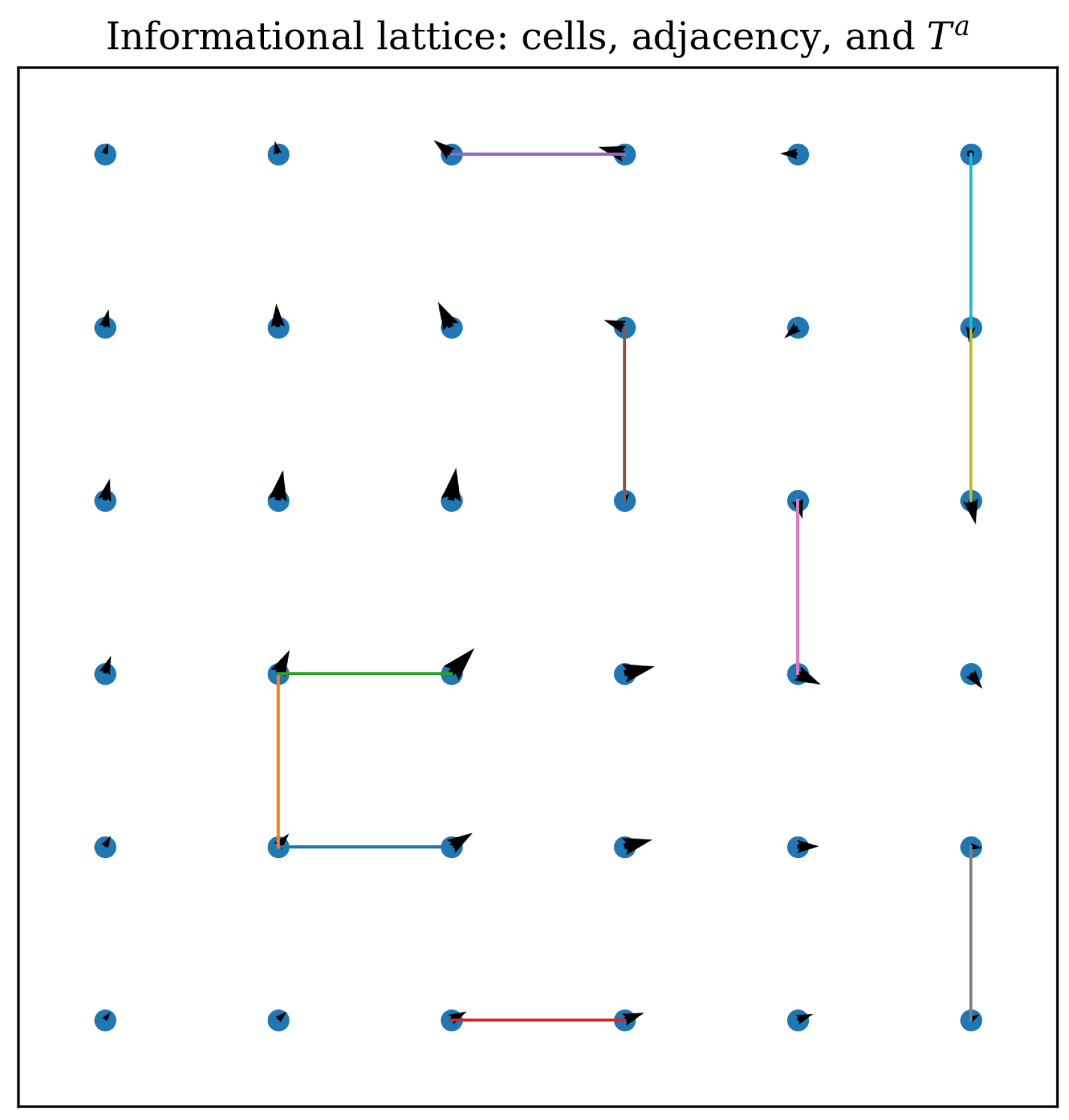

Figure 2.

Informational lattice of Planck-scale cells forming a causal-entanglement network. Each cell stores quantum information and connects to others through nonzero mutual information . Arrows indicate gradients of the informational potential , forming the local temporal field .

Figure 2.

Informational lattice of Planck-scale cells forming a causal-entanglement network. Each cell stores quantum information and connects to others through nonzero mutual information . Arrows indicate gradients of the informational potential , forming the local temporal field .

Local physical interactions deposit information into a cell through the imprint operator

where

is the boundary operator containing degrees of freedom that couple to neighboring cells. The constant

sets the strength of information transfer relative to local curvature. The imprint operation is trace-preserving at the global level but locally irreversible, consistent with the monotonic growth of stored information.

Causal adjacency between cells is defined not by geometric distance but by mutual information. Two cells

and

are adjacent if

This entanglement-based adjacency graph inherits an approximate Lorentz symmetry when the lattice spacing approaches zero and when entanglement propagation becomes effectively lightlike. In this limit, the adjacency graph converges to a structure with invariant null cones, providing a continuum recovery of Lorentz invariance without imposing it microscopically.

The dynamical propagation of mutual information across the QMM generates an emergent causal structure. Over time, the collective set of imprints recorded across the network constitutes a globally consistent informational history of the universe.

2.2. Information Capacity and Curvature

The Geometry-Information Duality (GID) principle states that spacetime curvature arises from spatial variations in informational storage. The informational entropy field

provides a coarse-grained measure of stored information at each location.

Gradients and second derivatives of

encode the temporal and geometric structure. The emergent metric is determined by the Hessian:

This relation does not imply that a vanishing Hessian yields a vanishing metric; rather, it yields a constant metric up to normalization. A zero Hessian corresponds to a region of uniform information density, producing the Minkowski metric in the macroscopic limit. The informational gradients

define the local temporal field, while the Hessian defines curvature.

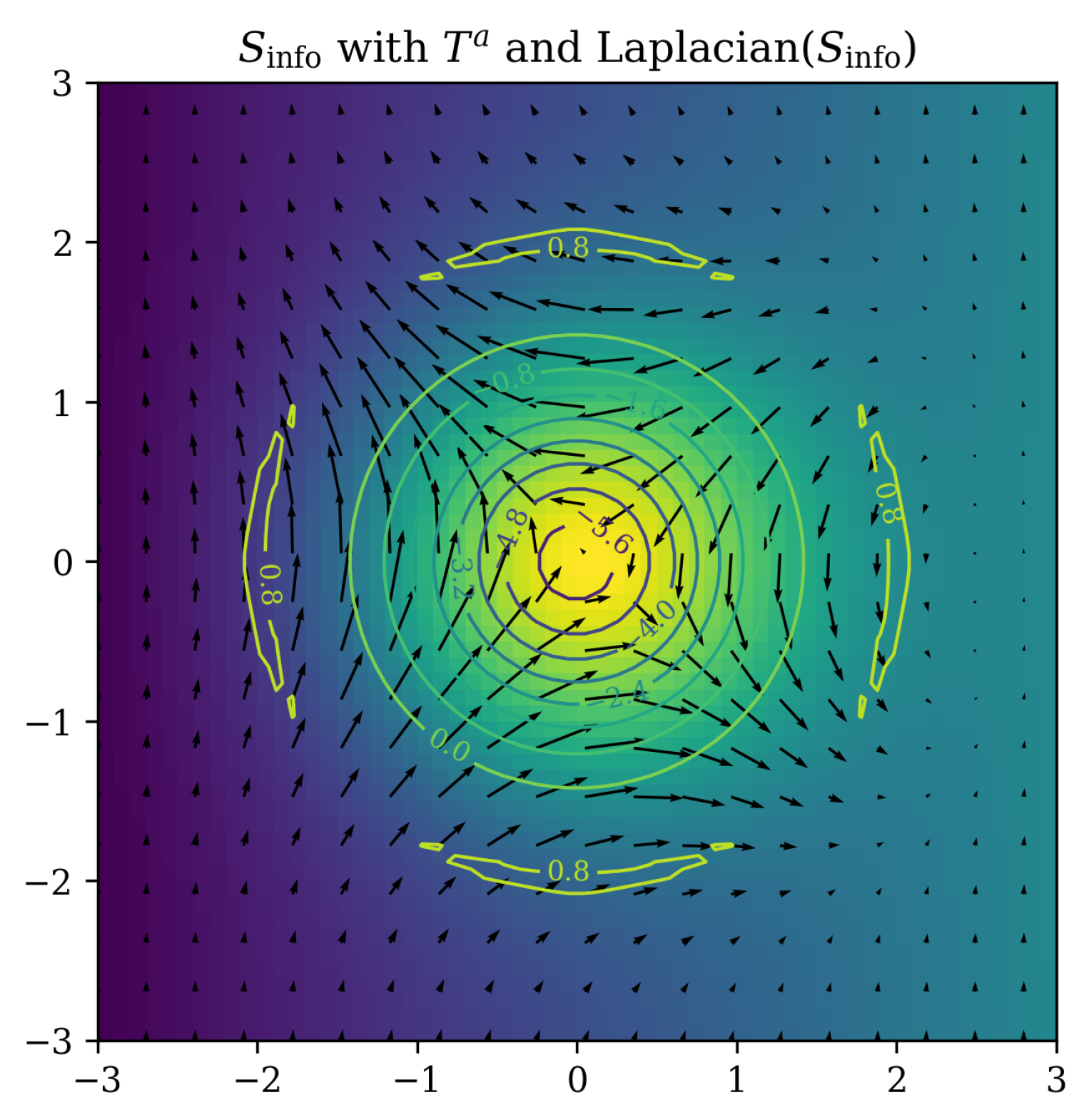

Figure 3.

Mapping between information density, its gradient, and emergent curvature. Shading indicates , arrows show , and contour lines represent the Laplacian of as a curvature indicator.

Figure 3.

Mapping between information density, its gradient, and emergent curvature. Shading indicates , arrows show , and contour lines represent the Laplacian of as a curvature indicator.

At a coarse-grained level, the effective action governing the emergent geometry is

This action is not derived from the microscopic imprint dynamics but represents a macroscopic effective field theory in which information gradients contribute an additional stress-energy component. Varying the action yields an Einstein-like field equation,

with

This coarse-grained equation is consistent with the macroscopic emergence of general relativity. When information gradients vary slowly relative to the coarse-graining scale, the additional informational stress-energy becomes negligible, and the Einstein tensor reduces to the familiar GR form. When gradients are large, as near black holes or during early-universe epochs, the informational contribution becomes dynamically significant.

The GID principle, therefore, ties gravitational curvature, entropy gradients, and informational dynamics into a unified description. Earlier approaches such as [

19] introduced entropic potentials influencing geometric evolution, but the present formalism differs by identifying the metric itself with the Hessian of a physical information field defined on a quantum memory substrate. This establishes a direct mechanism by which curvature and temporal asymmetry arise from distributed information processing within the QMM.

3. Informational Time as a Vector Field

The Quantum Memory Matrix formalism suggests a local description of temporal structure that arises from informational dynamics rather than from an externally imposed parameter. If spacetime geometry emerges from the distribution and variation of stored information, then temporal direction should emerge from the directional propagation of these variations. This leads naturally to a representation of time as a vector field defined on the informational manifold. The field captures how local information changes with respect to the spacetime coordinates and provides an informational counterpart to proper time in general relativity.

3.1. Definition

We define the informational temporal field

as the gradient of the coarse-grained informational entropy field,

This field identifies the direction of steepest informational increase and quantifies the local rate of information deposition. In the Quantum Memory Matrix, imprint events increase

irreversibly, so

acts as a local temporal vector tied directly to the underlying memory dynamics.

Different regions of the QMM may have distinct informational gradients, leading to multiple effective “time directions”. In regimes where information density is nearly uniform, is approximately constant, and a single global time direction is recovered. In contrast, regions with strong informational gradients, such as black holes or early-universe domains, exhibit pronounced anisotropy in , reflecting the high rate of local information deposition.

This construction differs from earlier entropic or emergent-time proposals in that time is not introduced as a correlation parameter. Instead, it is a physically defined vector field determined by the spatial variation of a genuine information-storage capacity.

3.2. Properties

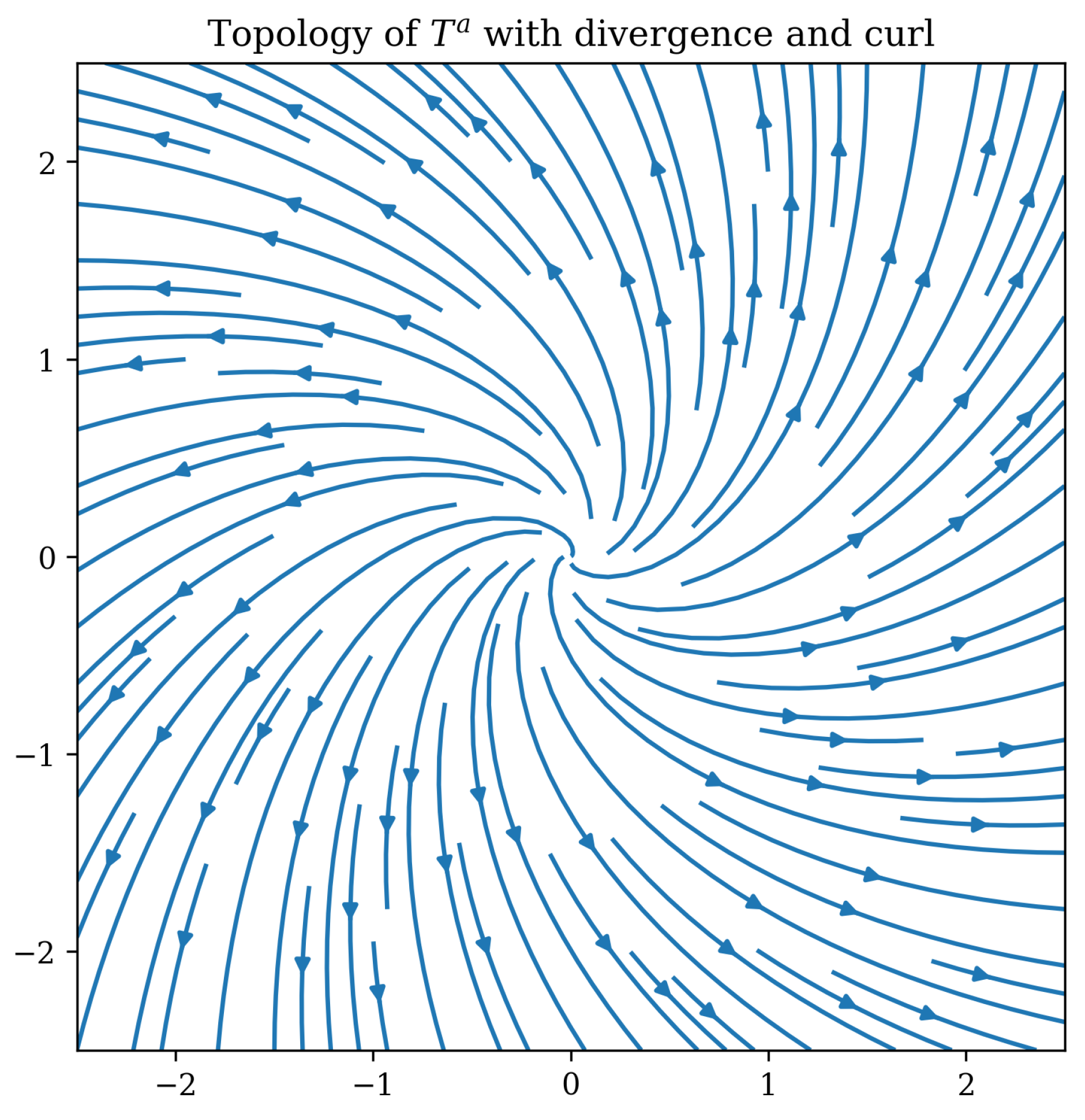

The vector field

is generally not globally integrable. A nonzero antisymmetric derivative,

indicates the presence of temporal curvature analogous to rotational structure in spacetime. Regions with nonzero curl correspond to domains where informational updates circulate in the abstract informational manifold, generating temporal torsion distinct from but coupled to geometric curvature (see

Figure 4). Temporal curvature in the informational sense captures how the direction of maximum information flow varies across space.

The norm of the temporal field,

determines the local informational update rate. Differences in

correspond to differential rates of temporal progression, producing effects analogous to general relativistic time dilation. In regions where

changes rapidly, the informational update rate slows relative to regions with mild gradients. This yields an informational analogue of gravitational redshift.

In the limit where

varies slowly, its Hessian vanishes and the emergent metric becomes constant:

A vanishing Hessian does not imply a vanishing metric; it implies the metric is uniform. This limit ensures compatibility with general relativity: when information is uniformly distributed, the informational spacetime reduces to Minkowski space.

3.3. Relation to Observer Dynamics

An observer can be modeled as a trajectory through the informational manifold, characterized by a sequence of read-write operations on adjacent QMM cells. The evolution of an observer’s informational state is governed by the local structure of

. The tangent to the observer’s worldline is aligned with the temporal field:

where

is the informational proper time. This relation is not intended to replace the geodesic equation of general relativity but to supplement it with an informational interpretation. In the macroscopic limit where the emergent metric is smooth, geodesic motion is recovered because

becomes aligned with the timelike eigenvector of the metric and satisfies the usual compatibility relations.

Proper time is reinterpreted as an accumulated informational distance:

This expression reflects a postulate of the informational-time construction: the temporal interval experienced by an observer corresponds to the amount of information deposited along the path, scaled by the invariant constant

c. When

is aligned and the metric is approximately Minkowskian, this reduces to the standard expression for proper time in relativity.

In this formulation, causal accessibility corresponds to the ability to traverse a path along which the informational gradient is nonzero. Two events are causally related if there exists a continuous path of informational updates connecting their respective QMM cells. The ordering imposed by determines the experiential temporal sequence of each observer, while the magnitude of sets the relative rate at which time progresses. This interpretation unifies temporal flow, gravitational dilation, and entropy increase as manifestations of a single informational structure underlying the emergent geometry.

4. Geometry-Information Duality and Temporal Curvature

The Geometry-Information Duality (GID) principle extends the correspondence between curvature and information developed in previous Quantum Memory Matrix studies [

1,

2] to include temporal structure. If spacetime geometry arises from distributed information storage, then variations in the informational field must also determine temporal curvature. The temporal field

, introduced in

Section 3, encodes the local rate and direction of information flow. Its divergence, rotation, and norm therefore provide geometric measures of how informational processes shape both spatial and temporal structure. In this sense, the GID framework unifies curvature, entropy production, and the arrow of time within a single differential formalism.

4.1. Information-Induced Curvature

In the QMM formulation, gradients of the informational field

determine temporal direction, while its second derivatives determine curvature. At the coarse-grained level of the effective action introduced in

Section 2, the dependence of the metric on the Hessian of

implies that the Einstein tensor admits an informational interpretation,

in the macroscopic regime where the metric is defined as a smooth potential derived from the informational landscape. This relation is not a microscopic identity but a phenomenological correspondence that follows from the form of the effective action. It captures the idea that curvature is sourced by spatial variations in information density. The Einstein field equation,

emerges in the limit where the informational contribution to the total stress-energy tensor varies slowly relative to the coarse-graining scale. In this regime, the flux of information between neighboring QMM cells scales with the local energy-momentum density, and the standard gravitational dynamics of general relativity are recovered.

Temporal curvature arises from the antisymmetric part of the derivative of the temporal field,

This tensor measures the rotation of informational flow lines and characterizes regions where the direction of maximal information increase varies nontrivially. While geometrically analogous to torsion or vorticity,

does not represent spacetime torsion. Instead, it describes rotational structure in the informational manifold generated by closed loops of causal information transfer or circulating entropy fluxes. Regions with

thus possess nontrivial temporal geometry.

The divergence of the temporal field,

relates informational flux to the local entropy-production rate. This equation is a definitional identity that follows from the construction

. It encapsulates the informational form of the second law: the divergence of

is non-negative because the total stored information in the QMM cannot decrease. Temporal curvature is therefore a geometric manifestation of irreversible information flow across the QMM substrate.

4.2. Entropic Arrow and Local Anisotropy

The arrow of time emerges from directional asymmetry in the informational field. In the GID framework, entropy gradients fix the preferred orientation of temporal flow through the inequality

Where informational gradients are strong, the temporal field acquires a clear orientation, defining a dominant local time direction. Where gradients vanish, the informational geometry becomes isotropic and the distinction between past and future weakens. The arrow of time is therefore a local property of informational anisotropy rather than a universal global condition.

Reverse or orthogonal traversals of

correspond to non-classical or quantum-coherent evolution, where local information flow may temporarily reverse or decouple from macroscopic thermodynamic behavior. This occurs, for example, in quantum interference, entanglement revival, or error-corrected information retrieval [

17]. Such processes do not violate the global increase of

but reflect the fact that local information flow can be coherent even when the global field is not.

Local anisotropies in also produce observable physical effects. Variations in correspond to differential informational update rates and reproduce phenomena analogous to gravitational time dilation. In strongly curved regions, such as those near black holes or in early-universe epochs, high entropy flux generates anisotropic time directions that define distinct local temporal frames. When informational gradients vary slowly and the Hessian is nearly constant, these anisotropies vanish and the emergent geometry reduces to the Lorentzian structure of general relativity. This demonstrates that informational irreversibility and gravitational dilation arise from the same underlying mechanism—variations in the accumulation of imprints across the Quantum Memory Matrix.

In summary, the Geometry-Information Duality links curvature, entropy flow, and the arrow of time through the properties of the temporal field . Temporal curvature quantifies how information flux deforms causal relations, while entropy gradients fix the preferred orientation of time. The evolution of the universe can therefore be viewed as the relaxation of an informational field toward increasing entropy, with temporal and spatial curvature representing two complementary aspects of that relaxation process.

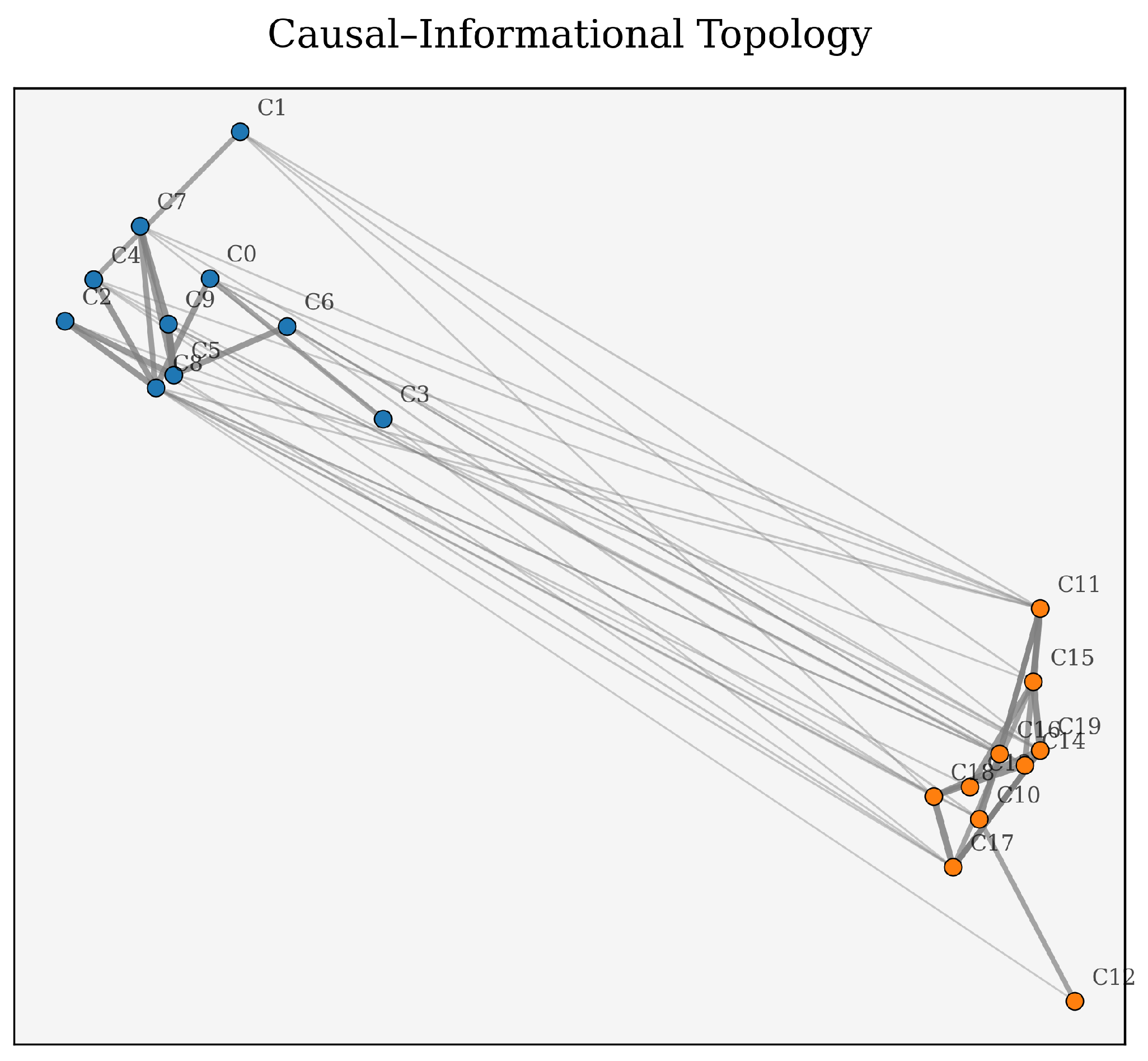

5. Causal Order and Temporal Navigability

The emergence of time in the Quantum Memory Matrix framework implies that causality is not an intrinsic ordering of events but a property derived from the topology of informational updates. The causal relations that define past and future in classical physics correspond, in QMM, to patterns of mutual information exchange among neighboring memory cells. This reformulation replaces the rigid causal order of relativity with a flexible, dynamic, and locally determined structure that reflects how information flows and transforms across the network. The result is a new type of temporal geometry in which navigability - movement through different informational directions - supersedes chronological succession as the defining feature of time.

5.1. From Fixed Partial Order to Informational Topology

In classical spacetime, causal order is defined by the metric signature of the Lorentz manifold: two events

x and

y are causally connected if a timelike or null geodesic exists between them. In QMM, this order arises instead from the adjacency relations among informational cells. Two cells

and

are said to be causally adjacent if they share mutual information above a threshold value,

This condition replaces light-cone connectivity with an

informational adjacency criterion: events are causally related when one can update the state of a cell in response to changes in another via entanglement propagation. The resulting adjacency graph defines an

informational topology rather than a fixed metric structure.

Within this topology, temporal neighborhoods are defined by the set of cells that can exchange information during a single update interval (see

Figure 5). The “distance” between two events is measured by the minimal number of update operations required to establish mutual information between them. This quantity generalizes both spacetime intervals and computational depth, reflecting the intrinsic discreteness of QMM evolution. The flow of information through this network defines a dynamic causal structure that can vary with energy, entropy, and curvature.

Consequently, causality in QMM is

contextual: it depends on the local entanglement configuration and on how information propagates through the surrounding network. During high-energy epochs - such as near a black hole horizon or in the early universe - the adjacency structure can fluctuate rapidly, producing regions of transient nonlocality or informational shortcuts. These correspond to quantum bridges in the informational manifold, where the causal structure becomes temporarily non-classical but remains globally consistent through the unitary evolution of the QMM state [

2,

14].

5.2. Navigable Time

Because causal order emerges from informational connectivity, the concepts of “past” and “future” must be reinterpreted as directions in the informational manifold that are accessible through specific types of traversal. An observer’s experience of time corresponds to following a path of successive informational updates in which the total entropy increases monotonically. However, other directions through the manifold - orthogonal or inverse to the dominant gradient - are not forbidden in principle. These directions correspond to informational traversals that are non-classical or quantum-coherent in nature.

The informational manifold is therefore

navigable: observers and systems can, at least theoretically, move along different temporal trajectories depending on how information is accessed, rewritten, or entangled. This can be modeled using an analogy to Finsler geometry, where the metric depends not only on position

x but also on direction

. In the informational case, the temporal metric depends on both the local entropy state and the direction of traversal:

where

encodes the effective “speed” of information propagation in the chosen direction

. Time, under this view, is not isotropic; it acquires direction-dependent curvature determined by informational anisotropy. This generalization allows for regions in which the informational distance between events depends on the chosen temporal trajectory, paralleling anisotropic geometries in Finsler spacetime [

22].

Mechanisms for moving across or between temporal directions can be understood as informational processes involving “reading” or “writing” across distinct causal layers. Examples include quantum recursion - feedback of a system’s output state into its own prior informational layer - and nonlocal entanglement, which allows correlated updates between causally disjoint regions. Both mechanisms have been observed in simulation of reversible QMM operations, where coherent superpositions of imprint sequences lead to bidirectional information propagation [

17].

In such conditions, informational paths that would correspond to reversed or branched timelines in classical terms become physically meaningful trajectories through the manifold. These trajectories preserve global unitarity and causal consistency, even though they locally violate the monotonic increase of entropy. The result is a model in which temporal traversal, rather than temporal flow, defines the accessible structure of reality. Observers do not move forward in time; they navigate an informational landscape whose topology encodes all possible causal directions.

In summary, QMM replaces the fixed partial order of classical causality with a dynamically evolving informational topology. Time becomes a navigable field, determined locally by entropy gradients and globally constrained by the unitarity of information flow. The past and future are not separate domains but complementary orientations within the same informational geometry, connected by reversible or coherent processes that allow limited traversal across the manifold’s temporal directions.

Figure 6.

Philosophical synthesis of chronological and navigational time. The lower layer represents the static informational manifold containing all events as encoded states (chronological order), while the upper trajectory illustrates an observer’s navigation through informational gradients (navigational time). This dual-layer view unites the timeless totality of the informational universe with the subjective experience of temporal flow.

Figure 6.

Philosophical synthesis of chronological and navigational time. The lower layer represents the static informational manifold containing all events as encoded states (chronological order), while the upper trajectory illustrates an observer’s navigation through informational gradients (navigational time). This dual-layer view unites the timeless totality of the informational universe with the subjective experience of temporal flow.

6. Physical Implications

The informational-time framework introduced in this work extends the Quantum Memory Matrix beyond its role as a theory of quantum-gravitational unification, offering a broader paradigm for understanding the nature of time, causality, and cosmological dynamics. By treating time as a local property of the informational field rather than as an external parameter, the QMM reinterprets temporal structure as an emergent feature of information flow, directly linking entropy, curvature, and causal order.

At cosmological scales, informational time provides a new interpretation of large-scale structure and temporal asymmetry. Temporal curvature, as defined in

Section 4, becomes significant near strong entropy sources such as black holes, the early universe, or regions of rapid phase transitions. In these environments, large gradients in

produce strong distortions in the temporal field

, leading to extreme time dilation and anisotropic temporal flow. The informational field thus reproduces general relativistic effects as emergent phenomena of entropy geometry, while extending them to regimes where the conventional continuum description breaks down.

The informational-time model also carries implications for cyclic and bidirectional cosmologies [

15]. In a cyclic QMM universe, each cosmological epoch corresponds to a phase of entropy accumulation followed by partial informational reset. Temporal curvature reverses sign at the informational turning points between contraction and expansion, producing alternating epochs of forward and backward navigational time while maintaining global informational continuity. This mechanism naturally accommodates cosmological recurrences without violating the monotonic global increase of entropy across cycles.

An additional hypothesis follows directly from the GID framework: entropic isotropy implies local time symmetry, while entropic anisotropy gives rise to directional temporal flow. Regions of the universe with uniform informational distribution experience locally symmetric time, whereas regions with strong informational gradients experience temporal directionality. The arrow of time, therefore, is not universal but a local emergent property of informational anisotropy. This view unites thermodynamic irreversibility, gravitational asymmetry, and cosmological evolution under a single principle: time flows only where information is being differentially written into the structure of the universe.

In summary, the informational-time formalism recasts temporality as a dynamical manifestation of information flow and curvature. It connects the microscopic processes of quantum imprinting to macroscopic cosmological evolution, explaining gravitational time dilation, entropy-driven asymmetry, and cyclic recurrence within one coherent physical framework.

7. Mathematical Examples and Simulations

This section provides constructive models that instantiate the informational-time formalism on discrete lattices and connects these constructions to continuum general relativity in appropriate limits. We first define a two-dimensional Quantum Memory Matrix lattice that carries a coarse-grained entropy field and supports local imprint dynamics. We then present a numerical scheme that exhibits temporal curvature from changing information density. Finally, we recover standard proper time and the Lorentzian metric when the temporal field aligns globally.

7.1. Toy Model: 2D QMM Lattice

Consider a square lattice

with lattice spacing

a. Each node

represents a QMM memory cell

with finite-dimensional Hilbert space

. The coarse-grained informational entropy at the node is

with

the reduced density matrix of

. The discrete temporal field

follows from forward finite differences

The discrete divergence and curl are

An imprint event at

updates the node entropy by

and induces entanglement-mediated adjacency updates that redistribute mutual information to nearest neighbors

according to a local conservation law for informational flux,

where

J denotes the discretized information current between cells, and

is the local production rate due to imprints [

1,

2].

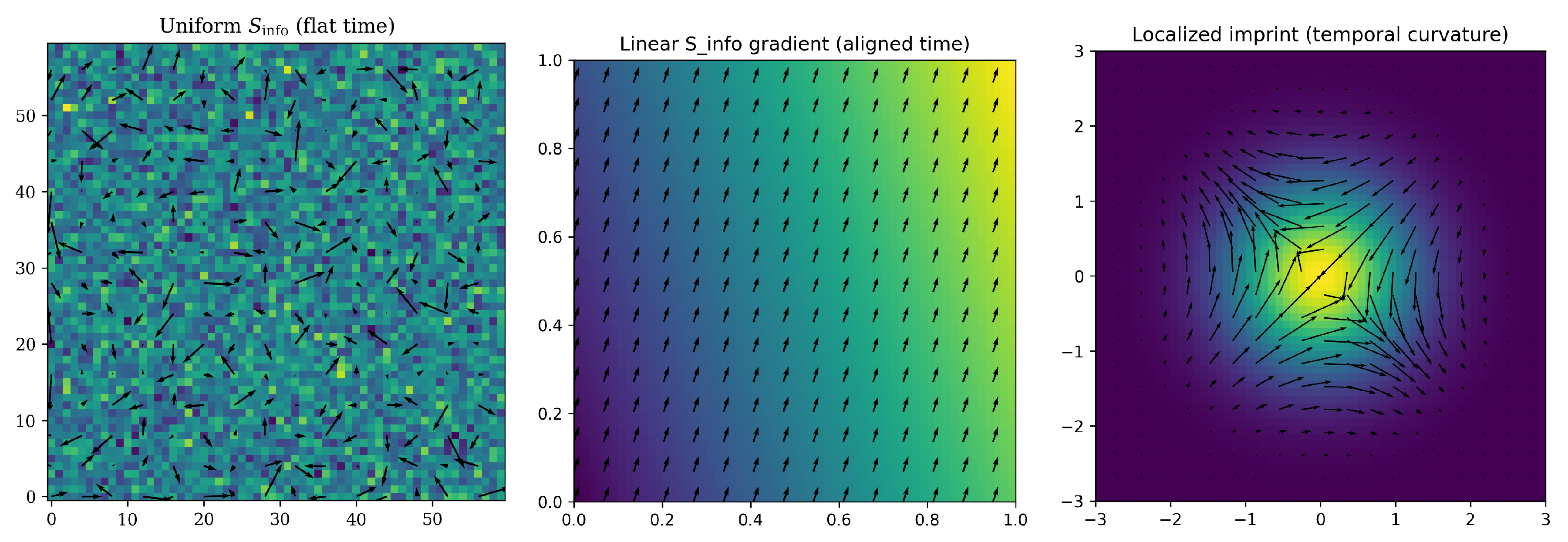

We illustrate three prototypical entropy landscapes and the induced :

Uniform sheet. for all . Then , , and . The informational geometry is flat and there is no preferred time direction locally.

Linear gradient. with . Then , , , . The temporal field is uniform and defines a global time orientation along the direction. Proper time increments are translation invariant.

Localized imprint well. . Then T is radial and its magnitude scales as . One finds near the peak, which encodes a source of informational flux and generates temporal curvature that dilates local update rates, analogous to redshift near mass concentrations.

These cases display, respectively, informational flatness, globally aligned time, and localized temporal curvature sourced by concentrated entropy imprints. They mirror the continuum statements derived in

Section 3 and

Section 4 for

and

.

7.2. Entropy-Curvature Simulation

We implement an explicit time-stepping scheme for the pair

on

. Let

n denote the simulation step with step size

measured in informational time. The update rules are

where

is a prescribed imprint production profile,

controls diffusive spreading of information, and

is the standard five-point Laplacian. The discrete temporal curvature scalars are monitored through

A stable Courant-like condition

ensures numerical stability of the entropy diffusion term [

25,

26].

Two benchmark experiments demonstrate the informational origin of temporal curvature:

Expanding imprint dome. Set for and zero afterward. During active imprinting one observes concentrated near the dome center, with T pointing outward. After the source turns off, diffusion relaxes S and decays toward zero, flattening temporal curvature.

Counter-rotating entropy shear. Initialize

with two off-center Gaussian lobes of unequal amplitude. As diffusion and cross-coupling proceed, a nonzero discrete curl

develops between lobes, signaling rotational structure in

T that encodes temporal torsion in the informational manifold. This matches the continuum expectation

from

Section 4.

7.3. Relation to GR Limits

We now connect the lattice constructions to continuum general relativity. Consider a smooth field

on a four-dimensional manifold with coordinates

. The informational-time postulate defines

Three limiting statements recover GR structure:

Minkowski limit. If with constant , then and the emergent metric is flat, . The temporal field is globally aligned, which matches the uniform-time case of the lattice model.

Constant curvature patch. If

with constant symmetric

, then

and the emergent metric has constant second derivatives. This reproduces a locally homogeneous curvature analogous to de Sitter or anti de Sitter patches depending on the signature induced by

[

27,

28].

-

Proper time identification. Along any timelike worldline

with tangent

we posit the informational proper time

If

is globally aligned and normalized so that

, this reduces to the standard line element

in the emergent Lorentzian geometry. Hence the informational-time formalism reproduces conventional proper time when the temporal field has global orientation and the Hessian defines the metric potential [

2].

The lattice and continuum pictures are consistent: homogeneous

yields

constant and vanishing Hessian, while localized or anisotropic entropy produces nontrivial Hessians that curve spacetime and rotate the temporal field. This realizes the GID statement that geometry is an information-induced potential, and it grounds gravitational redshift and time dilation in spatial variations of the informational landscape [

1,

29,

30].

These simulations numerically realize the identities

and

, and they exhibit how localized entropy production sources temporal curvature that subsequently relaxes through informational transport [

1,

2,

17].

Figure 7.

Simulation snapshots of the informational-time lattice. (a) Uniform information field () producing flat time with no curvature. (b) Linear gradient generating a globally aligned temporal field . (c) Localized imprint well producing strong informational gradients that induce temporal curvature and local dilation of update rates. These examples demonstrate how entropy gradients generate anisotropy and curvature in , supporting the Geometry–Information Duality principle.

Figure 7.

Simulation snapshots of the informational-time lattice. (a) Uniform information field () producing flat time with no curvature. (b) Linear gradient generating a globally aligned temporal field . (c) Localized imprint well producing strong informational gradients that induce temporal curvature and local dilation of update rates. These examples demonstrate how entropy gradients generate anisotropy and curvature in , supporting the Geometry–Information Duality principle.

8. Discussion and Outlook

The informational-time formalism developed in this work reframes one of the most persistent conceptual problems in theoretical physics: the nature of time in quantum gravity. Conventional approaches attempt to quantize the dynamical geometry of spacetime while retaining the idea of a global temporal parameter, yet the resulting equations often eliminate time entirely. The Quantum Memory Matrix framework resolves this tension by embedding temporal order in the informational dynamics that generate geometry itself. Time becomes the structure of informational change rather than a coordinate imposed on it.

Comparison to Canonical Time Problems in Quantum Gravity

In canonical quantum gravity, exemplified by the Wheeler-DeWitt equation, the wave function of the universe satisfies

, yielding a “frozen” formalism without explicit evolution. The QMM approach replaces this static picture with a dynamic informational substrate in which local updates supply the ordering absent from the canonical framework. Whereas relational and Page-Wootters models describe time as correlations among subsystems, the QMM defines those correlations physically through the imprint and retrieval of quantum information on discrete memory cells [

1,

2]. The result is a model that maintains general covariance while reinstating a locally defined, observer-dependent notion of time.

This informational treatment restores a consistent link between microscopic quantum evolution and macroscopic thermodynamic irreversibility. The directional bias of time arises from entropic curvature within the information field rather than from external boundary conditions or symmetry breaking. It thus integrates the thermodynamic arrow, the causal arrow, and the quantum-mechanical ordering of measurements into a single principle: all are manifestations of irreversible information storage within the QMM.

Possible Observable Effects

Although the QMM operates at the Planck scale, its predictions may manifest through measurable secondary effects. Gravitational time asymmetry could appear as small deviations from standard clock synchronization in regions of strong informational curvature, such as near black holes or in early-universe environments. In entanglement-based precision timekeeping - where correlated quantum systems are used as clocks - subtle anomalies might arise when the entanglement links traverse regions of differing informational curvature [

14]. These deviations would indicate that synchronization depends not only on gravitational potential but also on the underlying distribution of information density.

Another potential signature is anisotropy in the propagation of quantum coherence. If varies across a system, phase correlations in entangled states could exhibit small direction-dependent offsets. Such an effect would represent an experimental probe of informational anisotropy and the curvature of time. Advances in satellite-based quantum communication and long-baseline entanglement distribution may eventually make such measurements feasible.

Path Toward Quantum Simulation

The discrete structure of the QMM makes it suitable for implementation as a quantum computational model. Each memory cell can be represented by a finite set of qubits, and imprint operators

correspond to controlled unitaries that entangle local and boundary qubits. The informational field

then emerges from entropy measures on subsystems, while

corresponds to local gradients computed from those measures. This suggests a concrete route toward simulating informational time dynamics using quantum hardware [

17].

A QMM-based simulation would allow direct visualization of how local entropy generation curves temporal flow and how coherent information exchange can transiently reverse or branch that flow. Such simulations could connect cosmological-scale hypotheses with experimentally accessible systems, linking fundamental theory with laboratory-based verification.

Open Questions

The informational-time formulation raises several unresolved theoretical questions:

How can global integrability of be defined? The temporal field may not be globally curl-free, leading to topological obstructions to defining a universal time coordinate. Characterizing these obstructions may clarify whether closed informational time loops can exist and how they relate to chronology protection.

Can informational curvature be measured through observable proxies such as entropy flux, entanglement entropy, or holographic correlation functions? Establishing quantitative relationships between informational geometry and observable entropy production could make the theory empirically testable.

What are the implications of informational curvature for quantum error correction? If spacetime itself functions as a distributed memory, the mechanisms that stabilize information across the QMM may correspond to natural error-correcting codes. This analogy could inform both cosmological models of memory retention and practical quantum technologies.

How does informational curvature affect the long-term memory of the universe? In cyclic cosmological models, partial erasure or compression of imprints may occur during contraction phases. The balance between retention and rewriting of information could set fundamental limits on cosmic recurrence and information preservation [

15].

Addressing these questions requires a combination of analytical work, numerical simulation, and possibly experimental analogs in quantum networks. The informational approach to time thus opens a new research direction that bridges gravitational physics, quantum information, and computation.

9. Conclusion

Within the frameworks of the Quantum Memory Matrix and Geometry–Information Duality, time emerges as an informational field rather than as a preexisting geometric coordinate. The temporal vector field expresses the local direction and intensity of information updating, establishing a quantitative link between entropy gradients, causal order, and temporal flow. This formulation restores locality by defining time through the exchange of information between neighboring regions, thereby replacing external chronology with intrinsic informational dynamics. It accounts for the arrow of time as a natural consequence of entropic anisotropy and unites thermodynamic irreversibility, spacetime curvature, and quantum evolution within a single consistent framework. The analysis presented here demonstrates that curvature and temporal asymmetry arise jointly from variations in informational density. The field governs not only local causal structure but also large-scale cosmological behavior, reproducing gravitational time dilation and suggesting mechanisms for cyclic or bidirectional epochs. Together, these results show that time is not a background parameter but an emergent property of the universe’s informational architecture - a self-organizing field through which geometry, matter, and entropy become dynamically linked. In this picture, the universe does not evolve within time; rather, time is the pattern by which the universe’s information evolves.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank colleagues for discussions on informational geometry and temporal fields.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Mathematical Definitions

Appendix A.1. QMM Lattice and Hilbert Structure

The Quantum Memory Matrix is represented as a discrete set of memory cells

, each corresponding to a minimal four-volume of Planck dimension. Each cell carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

where

is bounded by the covariant entropy limit

and

is the causal-surface area of cell

. The global state of the universe is a tensor product

Each cell evolves by local imprint operations that deposit or retrieve quantum information while preserving global unitarity.

Appendix A.2. Imprint Operator

The imprint operator

acts locally on

and its boundary degrees of freedom:

where

is the boundary operator encoding interaction terms with neighboring cells and

sets the coupling strength between local information flow and curvature. The operator updates the local density matrix as

The trace-preserving character of ensures that global information is conserved even when individual updates are irreversible.

Appendix A.3. Entropy Potential and Information Metric

The informational entropy of a cell is defined as

The informational metric arises as the second derivative of the entropy potential:

This relation encodes the Geometry-Information Duality: curvature originates from gradients of stored information. The local temporal field is the first derivative,

and the Hessian of

connects these quantities through

In flat informational regions, and ; in curved regions, the second derivative structure defines local geometry and temporal anisotropy.

Appendix B. Relation to Relativistic Limits

In a homogeneous information field where

varies linearly,

the derivative

is constant. The metric Hessian vanishes,

and the emergent geometry is flat with

. The field

defines a uniform time orientation, reproducing the classical Minkowski structure with constant proper time flow.

Time dilation arises from spatial variations in the magnitude of

. For two neighboring regions with different local gradients of

, the relative rate of proper time follows

Regions with stronger informational gradients (larger

) experience slower local time flow relative to regions with weaker gradients. This reproduces gravitational redshift as an informational effect:

Hence, general relativistic time dilation appears as a manifestation of differential informational flow rates in the QMM formalism.

Appendix C. Simulation Framework

The lattice dynamics of informational time can be simulated through a discrete-time scheme on a two-dimensional grid. The following pseudocode summarizes the procedure introduced in

Section 7:

Initialize lattice S[i,j] = S0 + small random perturbations

for n = 1 to N_steps:

for all (i,j):

# Local entropy production (imprint events)

deltaS = sigma_imp[i,j] + kappa * Laplacian(S[i,j])

S[i,j] += dt * deltaS

# Compute temporal field components

for all (i,j):

Tx[i,j] = (S[i+1,j] - S[i-1,j]) / (2*a)

Ty[i,j] = (S[i,j+1] - S[i,j-1]) / (2*a)

# Compute divergence and curl

divT[i,j] = (Tx[i+1,j] - Tx[i-1,j] + Ty[i,j+1] - Ty[i,j-1]) / (2*a)

curlT[i,j] = (Ty[i+1,j] - Ty[i-1,j] - Tx[i,j+1] + Tx[i,j-1]) / (2*a)

Record S, Tx, Ty, divT, curlT at selected intervals

end for

Visualization of and yields direct insight into entropy sources and temporal curvature. The stability condition ensures bounded evolution, while variable profiles can model localized entropy production such as black-hole analogues or cosmological expansions. Simulations confirm that the divergence of T tracks the global entropy increase , while the curl reflects local temporal torsion.

Appendix D. Philosophical Notes

The informational-time framework integrates several prior philosophical approaches to time while reinterpreting their foundational assumptions.

Julian Barbour’s concept of “Platonia” [

9] treats the universe as a timeless configuration space in which each static arrangement of matter corresponds to a single point. Temporal flow, in this view, is an illusion arising from correlations among configurations. The QMM refines this idea by supplying a concrete substrate - informational imprints - that realize such correlations physically. Instead of timeless static configurations, the QMM holds discrete informational states that can be traversed through read–write operations, producing the phenomenology of motion and change.

Carlo Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics [

8] proposes that physical reality consists only of relations between systems, not absolute states. Time is thus a correlation parameter internal to each relational context. The QMM aligns with this view but grounds it in the informational geometry of spacetime: relationality arises from mutual information exchange between adjacent cells, and the temporal field

defines the local relational order.

In Barbour’s and Rovelli’s frameworks, time is epistemic - a construct of observation. In the QMM, time is both epistemic and ontological. It is epistemic because observers perceive only local sequences of updates within their accessible information domains, and ontological because those updates are physical events encoded irreversibly in the structure of spacetime itself. The informational manifold therefore bridges the two interpretations: time exists as a property of how information is stored and accessed, and its subjective flow reflects the navigation of conscious systems through this informational landscape. This connection extends naturally to the phenomenology of perception. The subjective “now” corresponds to a localized reference frame within the informational manifold - the current set of active read–write operations defining an observer’s cognitive state. As an observer’s information field evolves, this reference frame shifts continuously, producing the sense of temporal passage. Conscious continuity arises from the coherence of informational updates rather than from a fundamental flow of time. Because the QMM defines adjacency through information exchange, it also accommodates nonlocal correlations among informational states. Conscious experience, being temporally coherent, may exploit such correlations to maintain persistence and unity across discrete updates. This offers a physical account of how identity and memory persist within an informational substrate. Furthermore, reversible imprint operations and entangled pathways within the QMM provide a potential mechanism for retrocausal or acausal phenomena discussed in theoretical contexts [

17,

23,

24]. Such effects do not imply violation of causality but instead correspond to coherent navigation through the informational manifold’s nonlocal structure.

In this sense, the QMM provides a reconciliation of timeless and dynamic ontologies. The universe, conceived as an informational totality, is static in its completeness, yet observers embedded within it experience time as the progressive traversal of informational gradients that continually redefine the “present.” The subjective perception of becoming thus arises not from physical motion of the cosmos but from the self-referential dynamics of informational observers within it.

References

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neukart, F. Geometry–Information Duality Quantum Entanglement Contributions to Gravitational Dynamics. Annals of Physics 2025, 485, 170325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B. S. Quantum theory of gravity. I. The canonical theory. Phys. Rev. 1967, 160, 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, C. J. Canonical quantum gravity and the problem of time. In Integrable Systems, Quantum Groups, and Quantum Field Theories; NATO ASI Series C: Mathematical and Physical Sciences; Springer: Dordrecht, 1993; pp. 157–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchař, K. Time and interpretations of quantum gravity. In Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on General Relativity and Relativistic Astrophysics; World Scientific: Singapore, 1992; pp. 211–314. [Google Scholar]

- Page, D. N.; Wootters, W. K. Evolution without evolution: Dynamics described by stationary observables. Phys. Rev. D 1983, 27, 2885–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Time in quantum gravity: An hypothesis. Phys. Rev. D 1991, 43, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovelli, C. Relational quantum mechanics. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1996, 35, 1637–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J. The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Verlinde, E. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to Dark Energy: Residual Vacuum Imprint and Slow-Roll Entropy Fields. Astronomy 2025, 1, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Quantum Memory Matrix Framework Applied to Cosmological Structure Formation and Dark Matter Phenomenology. Universe 2025, 1, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Information Wells and the Emergence of Primordial Black Holes in a Cyclic Quantum Universe. Universe 2025, 1, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Counting Cosmic Cycles: Past Big Crunches, Future Recurrence Limits, and the Age of the Quantum Memory Matrix Universe. Universe 2025, 1, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to the Strong and Weak Interactions. Entropy 2025, 1, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. QMM-Enhanced Error Correction: Demonstrating Reversible Imprinting and Retrieval for Robust Quantum Computation. Quantum Inf. Process. 2025, 24, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. A covariant entropy conjecture. J. High Energy Phys. 1999, 1999, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekov, R. Quantum diffusion. Found. Phys. Lett. 2006, 19, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, C.; Wohlfarth, M. N. R. Finsler geometric extension of Einstein gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 064040. [Google Scholar]

- Price, H. Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’ Point: New Directions for the Physics of Time; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stapp, H. P. Mindful Universe: Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer; Springer: Berlin, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H.; Teukolsky, S. A.; Vetterling, W. T.; Flannery, B. P. Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- LeVeque, R. J. Finite Volume Methods for Hyperbolic Problems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R. M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Misner, C. W.; Thorne, K. S.; Wheeler, J. A. Gravitation; W. H. Freeman: San Francisco, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, S.-I. Information Geometry and Its Applications; Springer: Tokyo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T. M.; Thomas, J. A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, 2006. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).