Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

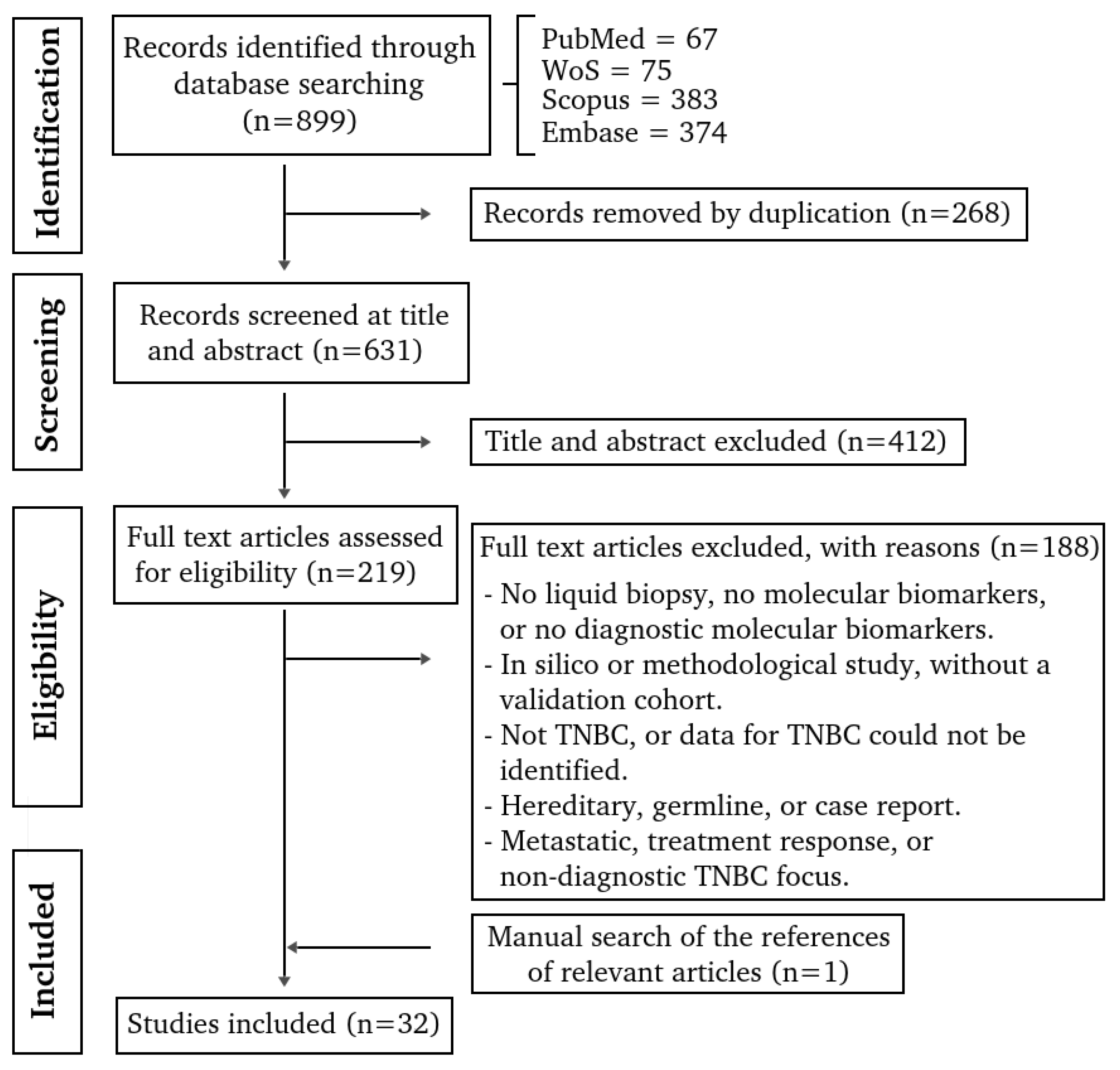

Background/Objectives: Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype, with limited diagnostic options and no targeted early detection tools. Liquid biopsy represents a minimally invasive approach for detecting tumor-derived molecular alterations in body fluids. This scoping review aimed to comprehensively synthesize all liquid biopsy–derived molecular biomarkers evaluated for the diagnosis of TNBC in adults. Methods: This review followed the Arksey and O’Malley framework and PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Systematic searches of PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science identified primary human studies evaluating circulating molecular biomarkers for TNBC diagnosis. Non-TNBC, non-human, hereditary, treatment-response, and non-molecular studies were excluded. Data on study design, patient characteristics, biospecimen type, analytical platforms, biomarker class, and diagnostic performance were extracted and synthesized descriptively by biomolecule class. Results: Thirty-two studies met inclusion criteria, comprising 15 protein-based, 11 RNA-based, and 6 DNA-based studies (one reporting both protein and RNA). In total, 1532 TNBC cases and 3137 participants in the comparator group were analyzed. Protein biomarkers were the most frequently studied, although only APOA4 appeared in more than one study, with conflicting results. RNA-based biomarkers identified promising candidates, particularly miR-21, but validation cohorts were scarce. DNA methylation markers showed promising diagnostic accuracy yet lacked replication. Most studies were small retrospective case–control designs with heterogeneous comparators and inconsistent diagnostic reporting. Conclusions: Evidence for liquid biopsy–derived biomarkers in TNBC remains limited, heterogeneous, and insufficiently validated. No biomarker currently shows reproducibility suitable for clinical implementation. Robust, prospective, and standardized studies are needed to advance liquid biopsy–based diagnostics in TNBC.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Reporting

2.2. Information Sources and Search

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Patients Characteristics

3.3. Novel Protein-Based Molecular Biomarkers Associated with TNBC Diagnosis

3.4. Novel RNA-Based Molecular Biomarkers Associated with TNBC Diagnosis

3.5. Novel DNA-Based Molecular Biomarkers Associated with TNBC Diagnosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| BC | Breast cancer |

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| CTC | Circulating tumor cell |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| ddPCR | Digital droplet polymerase chain reaction |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MALDI-TOF-MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MSP | Methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SRM | Selected reaction monitoring |

| SWATH | Sequential window acquisition of all theoretical fragment ion spectra |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| TNBC | Triple negative breast cancer |

| WB | Western blot |

References

- Bray F.; Laversanne M.; Sung H.; Arnold M.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Tsang J.Y.S.; Tse G.M. Molecular Classification of Breast Cancer. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2020, 27, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Tan PH; Ellis I; Allison K; Brogi E; Fox SB; Lakhani S; Lazar AJ; Morris EA; Sahin A; Salgado R; Sapino A; Sasano H; Schnitt S; Sotiriou C; van Diest P; White VA; Lokuhetty D; Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Histopathology 2020, 77(2), 181–185. [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan F; Reis-Filho J.S. Pathogenesis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2021, 17, 181–204. [CrossRef]

- Tay T.K.Y.; Tan P.H. Liquid Biopsy in Breast Cancer: A Focused Review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021, 145(6), 678–686. [CrossRef]

- Qiu P.; Yu X.; Zheng F.; Gu X.; Huang Q.; Qin K.; Hu Y.; Liu B.; Xu T.; Zhang T.; Chen G.; Liu Y. Advancements in Liquid Biopsy for Breast Cancer: Molecular Biomarkers and Clinical Applications. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 139, 102979. [CrossRef]

- Malik S.; Zaheer S. The Impact of Liquid Biopsy in Breast Cancer: Redefining the Landscape of Non-Invasive Precision Oncology. J. Liq. Biopsy 2025, 8, 100299. [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo R.; Sears J.; Palmero L.; Bolzonello S.; Davis A.A.; Gerratana L.; Puglisi F. Liquid Biopsy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Unlocking the Potential of Precision Oncology. ESMO Open 2024, 9(10), 103700. [CrossRef]

- Zaikova E.; Cheng B.Y.C.; Cerda V.; et al. Circulating Tumour Mutation Detection in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer as an Adjunct to Tissue Response Assessment. npj Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 3. [CrossRef]

- Sheng J.; Zong X. Liquid Biopsy in TNBC: Significance in Diagnostics, Prediction, and Treatment Monitoring. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1607960. [CrossRef]

- Levac D.; Colquhoun H.; O’Brien K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [CrossRef]

- Li C.I.; Mirus J.E.; Zhang Y.; Ramirez A.B.; Ladd J.J.; Prentice R.L.; McIntosh M.W.; Hanash S.M.; Lampe P.D. Discovery and Preliminary Confirmation of Novel Early Detection Biomarkers for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Using Preclinical Plasma Samples from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 135(2), 611–618. [CrossRef]

- Liu A.N.; Sun P.; Liu J.N.; Yu C.Y.; Qu H.J.; Jiao A.H.; Zhang L.M. Analysis of the Differences of Serum Protein Mass Spectrometry in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Non-Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35(10), 9751–9757. [CrossRef]

- Suman S.; Basak T.; Gupta P.; Mishra S.; Kumar V.; Sengupta S.; Shukla Y. Quantitative Proteomics Revealed Novel Proteins Associated with Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer. J. Proteomics 2016, 148, 183–193. [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye A.; Dabhi R.; Taunk K.; Jagadeeshaprasad M.G.; RoyChoudhury S.; Mane A.; Bayatigeri S.; Chaudhury K.; Santra M.K.; Rapole S. Multipronged Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Serum Proteome Alterations in Breast Cancer Intrinsic Subtypes. J. Proteomics 2017, 163, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Del Pilar Chantada-Vázquez M.; López A.C.; Vence M.G.; Vázquez-Estévez S.; Acea-Nebril B.; Calatayud D.G.; Jardiel T.; Bravo S.B.; Núñez C. Proteomic Investigation on the Bio-Corona of Au, Ag and Fe Nanoparticles for the Discovery of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Serum Protein Biomarkers. J. Proteomics 2020, 212, 103581. [CrossRef]

- Fang J.; Tao T.; Zhang Y.; Lu H. A Barcode Mode Based on Glycosylation Sites of Membrane-Type Mannose Receptor as a New Potential Diagnostic Marker for Breast Cancer. Talanta 2019, 191, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Chanana P.; Pandey A.K.; Yadav B.S.; et al. Significance of Serum Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Cancer Antigen 15.3 in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Radiother. Pract. 2014, 13(1), 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Cui R.; Zou J.; Zhao Y.; Zhao T.; Ren L.; Li Y. The Dual-Crosslinked Prospective Values of RAI14 for the Diagnosis and Chemosurveillance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ann. Med. 2023, 55(1), 820–836. [CrossRef]

- Song D.; Yue L.; Zhang J.; Ma S.; Zhao W.; Guo F.; Fan Y.; Yang H.; Liu Q.; Zhang D.; Xia Z.; Qin P.; Jia J.; Yue M.; Yu J.; Zheng S.; Yang F.; Wang J. Diagnostic and Prognostic Significance of Serum Apolipoprotein C-I in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Based on Mass Spectrometry. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016, 17(6), 635–647. [CrossRef]

- Luo R.; Zheng C.; Song W.; Tan Q.; Shi Y.; Han X. High-Throughput and Multi-Phase Identification of Autoantibodies in Diagnosing Early-Stage Breast Cancer and Subtypes. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113(2), 770–783. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary P.; Gibbs L.D.; Maji S.; Lewis C.M.; Suzuki S.; Vishwanatha J.K. Serum Exosomal Annexin A2 Is Associated with African-American Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Promotes Angiogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Schummer M.; Thorpe J.; Giraldez M.D.; Bergan L.; Tewari M.; Urban N. Evaluating Serum Markers for Hormone Receptor-Negative Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(11), e0142911. [CrossRef]

- Santana M.F.M.; Sawada M.I.B.A.C.; Junior D.R.S.; Giacaglia M.B.; Reis M.; Xavier J.; Côrrea-Giannella M.L.; Soriano F.G.; Gebrim L.H.; Ronsein G.E.; Passarelli M. Proteomic Profiling of HDL in Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer Based on Tumor Molecular Classification and Clinical Stage of Disease. Cells 2024, 13(16), 1327. [CrossRef]

- Bilir C.; Engin H.; Can M.; Likhan S.; Demirtas D.; Kuzu F.; Bayraktaroglu T. Increased Serum Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Factor-6 Expression in Patients with Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 9(6), 2819–2824. [CrossRef]

- Chung J.M.; Jung Y.; Kim Y.P.; Song J.; Kim S.; Kim J.Y.; Kwon M.; Yoon J.H.; Kim M.D.; Lee J.K.; Chung D.Y.; Lee S.Y.; Kang J.; Kang H.C. Identification of the Thioredoxin-Like 2 Autoantibody as a Specific Biomarker for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Breast Cancer 2018, 21(1), 87–90. [CrossRef]

- Sharma U.; Barwal T.S.; Khandelwal A.; Malhotra A.; Rana M.K.; Singh Rana A.P.; Imyanitov E.N.; Vasquez K.M.; Jain A. LncRNA ZFAS1 Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Targeting STAT3. Biochimie 2021, 182, 99–107. [CrossRef]

- Shin V.Y.; Siu J.M.; Cheuk I.; Ng E.K.; Kwong A. Circulating Cell-Free miRNAs as Biomarkers for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112(11), 1751–1759. [CrossRef]

- Kahraman M.; Röske A.; Laufer T.; Fehlmann T.; Backes C.; Kern F.; Kohlhaas J.; Schrörs H.; Saiz A.; Zabler C.; Ludwig N.; Fasching P.A.; Strick R.; Rübner M.; Beckmann M.W.; Meese E.; Keller A.; Schrauder M.G. MicroRNA in Diagnosis and Therapy Monitoring of Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11584. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V.; Gautam M.; Chaudhary A.; Chaurasia B. Impact of Three miRNA Signature as Potential Diagnostic Marker for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21643. [CrossRef]

- Liu M.; Xing L.Q.; Liu Y.J. A Three-Long Noncoding RNA Signature as a Diagnostic Biomarker for Differentiating Between Triple-Negative and Non-Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Medicine 2017, 96(9), e6222. [CrossRef]

- Souza K.C.B.; Evangelista A.F.; Leal L.F.; Souza C.P.; Vieira R.A.; Causin R.L.; Neuber A.C.; Pessoa D.P.; Passos G.A.S.; Reis R.M.V.; Marques M.M.C. Identification of Cell-Free Circulating MicroRNAs for the Detection of Early Breast Cancer and Molecular Subtyping. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 8393769. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim A.M.; Said M.M.; Hilal A.M.; Medhat A.M.; Abd Elsalam I.M. Candidate Circulating MicroRNAs as Potential Diagnostic and Predictive Biomarkers for the Monitoring of Locally Advanced Breast Cancer Patients. Tumour Biol. 2020, 42(10), 1010428320963811. [CrossRef]

- Qattan A.; Intabli H.; Alkhayal W.; Eltabache C.; Tweigieri T.; Amer S.B. Robust Expression of Tumor Suppressor miRNAs let-7 and miR-195 Detected in Plasma of Saudi Female Breast Cancer Patients. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 799. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen J.; Shahid S.; Shahzadi S.; Akhtar M.W.; Sadaf S. Identification of Circulating miRNAs as Non-Invasive Biomarkers of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in the Pakistani Population. Pak. J. Zool. 2019, 51, 1113–1121. [CrossRef]

- Du Q.; Yang Y.; Kong X.; Lan F.; Sun J.; Zhu H.; Ni Y.; Pan A. Circulating lncRNAs Acting as Diagnostic Fingerprints for Predicting Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11(8), 8139–8145. https://e-century.us/files/ijcem/11/8/ijcem0073914.pdf.

- Ritter A.; Hirschfeld M.; Berner K.; Rücker G.; Jäger M.; Weiss D.; Medl M.; Nöthling C.; Gassner S.; Asberger J.; Erbes T. Circulating Non-Coding RNA Biomarker Potential in Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer? Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 56(1), 47–68. [CrossRef]

- Manoochehri M.; Borhani N.; Gerhäuser C.; Assenov Y.; Schönung M.; Hielscher T.; Christensen B.C.; Lee M.K.; Gröne H.J.; Lipka D.B.; Brüning T.; Brauch H.; Ko Y.D.; Hamann U. DNA Methylation Biomarkers for Noninvasive Detection of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Using Liquid Biopsy. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152(5), 1025–1035. [CrossRef]

- Swellam M.; Abdelmaksoud M.D.; Mahmoud M.S.; Ramadan A.; Abdel-Moneem W.; Hefny M.M. Aberrant Methylation of APC and RARβ2 Genes in Breast Cancer Patients. IUBMB Life 2015, 67(1), 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Lee S.; Kim H.Y.; Jung Y.J.; Jung C.S.; Im D.; Kim J.Y.; Lee S.M.; Oh S.H. Comparison of Mutational Profiles Between Triple-Negative and Hormone Receptor-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Breast Cancers in T2N0-1M0 Stage: Implications of TP53 and PIK3CA Mutations in Korean Early-Stage Breast Cancers. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2022, 46(2), 100843. [CrossRef]

- Manoochehri M.; Jones M.; Tomczyk K.; Fletcher O.; Schoemaker M.J.; Swerdlow A.J.; Borhani N.; Hamann U. DNA Methylation of the Long Intergenic Noncoding RNA 299 Gene in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Results from a Prospective Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11762. [CrossRef]

- Vikramdeo K.S.; Anand S.; Sudan S.K.; Pramanik P.; Singh S.; Godwin A.K.; Singh A.P.; Dasgupta S. Profiling Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in Tumors and Circulating Extracellular Vesicles of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients for Potential Biomarker Development. FASEB Bioadv. 2023, 5(10), 412–426. [CrossRef]

- Mendaza S.; Ulazia-Garmendia A.; Monreal-Santesteban I.; Córdoba A.; Azúa Y.R.; Aguiar B.; Beloqui R.; Armendáriz P.; Arriola M.; Martín-Sánchez E.; Guerrero-Setas D. ADAM12 Is a Potential Therapeutic Target Regulated by Hypomethylation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21(3), 903. [CrossRef]

- Asleh K.; Riaz N.; Nielsen T.O. Heterogeneity of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Advances in Subtyping and Treatment Implications. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 265. [CrossRef]

- Gough A.; Stern A.M.; Maier J.; Lezon T.; Shun T.Y.; Chennubhotla C.; Schurdak M.E.; Haney S.A.; Taylor D.L. Biologically Relevant Heterogeneity: Metrics and Practical Insights. SLAS Discov. 2017, 22(3), 213–237. [CrossRef]

- Hayes D.F. Biomarker Validation and Testing. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9(5), 960–966. [CrossRef]

- Hall J.A.; Brown R.; Paul J. An Exploration into Study Design for Biomarker Identification: Issues and Recommendations. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2007, 4(3), 111–119.

- Ou F.S.; Michiels S.; Shyr Y.; Adjei A.A.; Oberg A.L. Biomarker Discovery and Validation: Statistical Considerations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16(4), 537–545. [CrossRef]

| AUC | Biofluid | Detection method | P-value | Alteration type | Biomarker | Comparator group | Case | Sample size | Study Ref. |

| Various | Plasma | Antibody microarray | p<0.05 | Up-regulated | Panel: KIT, ITGB1, EFNA5, SRP54, FAS, BRCA1, XBP1, and others | 28 not BC participants | 28 TNBC patients | 56 | [12] |

| Not reported | Serum | 2D-DIGE; MALDI-TOF-MS | p<0.05 | Up-regulated Down-regulated |

TTR, SERPINA1, HP | 30 not BC participants | 30 TNBC patients | 60 | [13] |

| 0.853 | Plasma | iTRAQ; WB; ELISA | A2M, C4BPA p<0.0001 FN1 p<0.018 |

Overexpression | FN1, A2M, C4BPA | 20 not BC participants | 8 TNBC patients | 28 | [14] |

| Not reported | Serum | 2D-DIGE/MALDI, iTRAQ-LC-MS/MS, SWATH, WB, SRM | p<0.05 | Up-regulated Down-regulated |

Panel: CPN2, CO2, MYL6, HV101, APOA4, PI16, CXCL7, VTDB, IGJ, KNG1 | 20 not BC participants | 19 TNBC patients | 39 | [15] |

| Not reported | Serum | NP exposure, SDS-PAGE, LC–MS/MS, SWATH/SRM | p<0.05 | Up-regulated Down-regulated |

Panel: APOL1, CFH, VTNC, C3, C4A, C9, LGALS3BP, FCN3, RBP4, FN1, APOA4, ORM1, ZPI, TTR, APOC1, APOC3, IGHM, IG chains | 8 not BC participants | 8 TNBC patients | 16 | [16] |

| Not reported | Serum | IP, SDS-PAGE, HILIC, MALDI-TOF MS | p < 0.01 | Glycosylation pattern change | MR | 110 participants* | 35 TNBC patients | 55 | [17] |

| Not reported | Serum | ELISA | p = 0.01 (size) p = 0.03 (stage) |

Increased serum concentration | VEGF | 35 not BC participants | 30 TNBC patients | 65 | [18] |

| 0.934 | Serum | ELISA | p<1e-4 | Increased serum concentration | RAI14 | 60 not BC participant** | 46 TNBC patients | 106 | [19] |

| 0.908 | Serum | SELDI-TOF-MS, qRT-PCR, ELISA, WB | p<1e-4 | Increased serum concentration | ApoC-I | 215 participants*** | 165TNBC patients | 380 | [20] |

| 0.875 | Serum | Serology | p<0.05 | Lower concentration panel | KJ901215, FAM49B, HYI, GARS, CRLF3 | 776 participants*** | 123 TNBC patients | 389 | [21] |

| 1 | Serum | Western blot, ELISA | p<1e-4 | Higher circulating concentrations | ANXA2 | 179 participants* | 58 TNBC patients | 126 | [22] |

| TP53 = <0.63 | Blood | ELISA |

Non significant |

Minimal diagnostic performance | GDF15, PKM, SPARC, CA125, WFDC2, COL1A1, FN1, CTGF, S100A7, SPP1, CCL5, hsa-miR-135b, Anti-TP53, HOXA5, SFRP1 | 87 not BC participant | 28 TNBC patients | 115 | [23] |

| Various | Plasma | Ultracentrifugation; LC-MS/MS | Various | Panel changes | ApoA1, ApoA2, ApoC2, ApoC4 C3, CFB, IGLC2/3, GC, PLG, SERPINA3, IGHC1, C9, LRG1, C4B |

204 participants* | 20 TNBC patients | 123 | [24] |

| Not reported | Serum | ELISA | p = 0.010 | Higher serum concentration | TRAF6 | 61 participants* | 13 TNBC patients | 39 | [25] |

| Not reported | Serum | HuProt microarray | Not reported | Higher concentration | Anti-TXNL2 | 10 not BC participants | 10 TNBC patients | 20 | [26] |

| AUC | Biofluid | Detection method | P-value | Alteration type | Biomarker | RNA type | Comparator group | Case | Sample size | Study Ref. |

| Not reported | Peripheral blood | RT2 lncRNA PCR Array, qRT-PCR | p<1e-4 | Up and down regulated | ZFAS1 | lncRNA | 40 not BC participants | 40 TNBC patients | 80 | [27] |

| 0.88 | Plasma | miRNA arrays, RT-qPCR | p<0.0001 | Down-regulated | miR-199a-5p, miR-16, miR-21 | miRNA | 255 participants* | 72 TNBC patients | 327 | [28] |

| 0.814 | Plasma | Microarray, RT-qPCR | p = 1.4e-5 | Concentration change | miR-126-5p | miRNA | 21 not BC participants | 21 TNBC patients | 42 | [29] |

| 0.961 | Serum | RT-qPCR | p<1e-4 | Up and down regulated | miR-21, miR-155, miR-205 | miRNA | 51 not BC participants | 139 TNBC patients | 190 | [30] |

| 0.934 | Serum | Microarray, RT-qPCR | p<0.01 | Overexpressed | NRIL, HIF1A-AS2, UCA1 | lncRNA | 75 participants** | 25 TNBC patients | 100 | [31] |

| 0.74 | Serum | NanoString nCounter | p≤0.05 | Up-regulated | miR-25-3p | miRNA | 69 participants** | 12 TNBC patients | 81 | [32] |

| Not reported | Plasma | qRT-PCR | Not reported | Up-regulated | miR-21 | miRNA | 46 participants** | 4 TNBC patients | 50 | [33] |

| Diagnostic panel = 0.929 | Plasma | RT-qPCR | p =0.0008–0.02 | Serum differential concentration | Initial and diagnostic panel. | miRNA | 91 participants*** | 36 TNBC patients | 127 | [34] |

| Not reported | Blood | ELISA; RT-qPCR |

Non significant |

Minimal diagnostic performance | miR-135b | miRNA | 87 not BC participants | 28 TNBC patients | 115 | [23] |

| 0.785 | Blood | RT-qPCR | p<0.0001 | Up- regulated | miR-376c, miR-155, miR-17a, miR-10b | miRNA | 34 not BC participants | 37 TNBC patients | 71 | [35] |

| 0.959 | Plasma | qRT-PCR | ANRIL = p<0.01 Others = p<0.05 |

Overexpressed | ANRIL, SOX2OT, ANRASSF1 | lncRNA | 220 participants** | 120 TNBC patients | 340 | [36] |

| Not reported | Serum Urine |

RT-qPCR | p<0.05 | Increase and decrease in concentration | Serum: let-7a, let-7e, miR-21, miR-15a, miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19b miR-30b, GlyCCC2 Urine: miR-18a, miR-19b, miR-30b, miR-222, miR-320, GlyCCC2 |

miRNA | 20 not BC participants | 16 TNBC patients | 36 | [37] |

| AUC | Biofluid | Detection method | P-value | Alteration type | Biomarker | Variation | Comparator group | Case | Sample size | Study Ref |

| Test set = 0.78 Validation set = 0.74 |

Plasma | Illumina 450K/EPIC, XGBoost, ddPCR |

P<0.0001 | Hypermethylation and hypomethylation | SPAG6, IFFO1, SPHK2; TBCD/ZNF750, LINC10606, CPXM1 | cfDNA methylation | 84 not BC participants | 139 TNBC patients | 223 | [38] |

| Not reported | Serum | MSP |

p = 0.007 (RARB2) |

Promoter methylation (RARB2 methylated in TNBC) | Promoter methylation: APC, RARB2 | DNA methylation | 145 participants* | 71 TNBC patients | 216 | [39] |

| Not reported | Plasma | RT-PCR | --- | No plasma mutations | PIK3CA hotspot mutations | Mutations | 22 not BC participants | 10 TNBC patients | 32 | [40] |

| Not reported | Buffy coat | ddPCR | P = 0.0025 p = 0.001 (tertile 1) |

Hypermethylation (leukocyte DNA) | LINC00299 (cg06588802) | Methylation | 159 not BC participants | 154 TNBC patients | 313 | [41] |

| Not reported | Serum | NGS (Illumina NovaSeq PE150) |

p<0.0001 (EV concentration) | EV concentration Tumor-specific/shared EV mutations |

mtDNA variants (ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND4L, ND5, ND6, CYTB, CO1, CO2, CO3, RNR2, ATP6, ATP8) | mtDNA | 9 not BC participants | 9 TNBC patients | 18 | [42] |

| Not reported | Plasma | Illumina 450K, Pyrosequencing |

Not reported | Hypomethylation | Promoter methylation ADAM12 |

Methylation cfDNA |

13 not BC participants | 6 TNBC patients | 19 | [43] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).