1. Introduction

Understanding CO₂ transport in fractal porous media is essential for predicting storage security, assessing displacement mechanisms, and quantifying subsurface migration pathways. Across pore, core, and reservoir scales, CO₂ migration is influenced by a combination of nonlinear diffusion, structural heterogeneity, and temporally correlated fluctuations that arise from complex pore geometries and connectivity patterns within natural formations [

1,

2,

3]. Classical Fickian diffusion models often fail to capture these phenomena, leading to significant discrepancies when applied to low-permeability or structurally complex media where anomalous diffusion and long-memory behavior are frequently observed [

4,

5].

Extensive experimental and theoretical studies have shown that CO

2 transport signals exhibit multi-scale variability, long-range temporal correlation, intermittency, and departures from Gaussian statistics, NMR-informed pore-scale flow measurements demonstrate that velocity fluctuations and local heterogeneity strongly influence solute dispersion [

6,

7,

8]. Molecular simulations and pressure-decay experiments further reveal the role of pore morphology, mineral distribution, and fluid-solid interactions in modulating CO

2 diffusion and relaxation dynamics [

9,

10]. At larger scales, neutron scattering, fractal upscaling, and stochastic reconstruction studies report that effective permeability and diffusivity reflect hierarchical pore networks and structural heterogeneity spanning multiple orders of magnitude [

11,

12,

13].

These observations have motivated the development of stochastic models capable of representing anomalous, memory-dependent, and scale-coupled transport mechanisms. Fractional Brownian motion (FBM) has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for characterizing long-range correlations, non-Fickian dispersion, and anomalous diffusion in porous media [

14,

15]. Its flexibility in modeling persistent or anti-persistent behavior has led to applications ranging from subsurface flow modeling [

16] to fractal-based transport characterization [

17,

18]. Recent extensions of FBM incorporate Hölder regularity, Hurst exponent estimation, and trajectory-level geometric constraints, improving its applicability in physically fractal environments [

19,

20,

21].

Parallel research highlights the effectiveness of wavelet transforms in multi-scale analysis of porous media signals. Wavelet methods have been applied to pressure fluctuations [

6], permeability characterization [

22], transient flow regime identification [

23], and fractal multi-scale structure detection in geological materials [

24,

25]. Their ability to isolate localized features and decompose signals across a hierarchy of spatial and temporal scales makes them particularly suited for characterizing structurally fractal systems.

Although FBM is well-established in modeling long-memory transport and wavelets are powerful for scale decomposition, their combined use in a single mechanistic stochastic framework remains limited. Furthermore, experimental CO

2 diffusion datasets often exhibit transient attenuation, relaxation, or white-noise-like segments, suggesting the presence of damping mechanisms, such as energy dissipation, pore-scale trapping, or transient relaxation, that classical FBM cannot represent [

26,

27] . Incorporating damping into FBM represents a promising direction for bridging the gap between physical transport mechanisms and stochastic mathematical representations. Given these challenges, there is a growing need for a mechanistically grounded, multi-scale stochastic model that simultaneously represents:

(i) long-memory and anomalous diffusion;

(ii) damping and relaxation effects; and

(iii) multi-resolution heterogeneity characteristic of complex porous media.

Motivation and Contributions of the Present Work

Motivated by the above gaps, this study introduces a wavelet-assisted damped fractional Brownian motion (WA-DFBM) framework to model CO2 transport in fractal porous media. The proposed framework is built upon porous media transport physics, experimental observations, and multi-scale stochastic theory. The key contributions are summarized as follows:

- 1.

A physically grounded fractional Brownian motion formulation: Capturing long-range temporal dependence, anomalous diffusion, and memory effects frequently observed in pore-scale CO2 transport signals.

- 2.

Introduction of a damping mechanism into FBM: To represent attenuation, relaxation, and dissipative behavior detected in experimental CO2 diffusion datasets but not captured by classical FBM or fractional models.

- 3.

Integration of multi-resolution wavelet decomposition with FBM: Allowing localized fluctuations, transient structures, and multi-scale heterogeneity to be isolated and incorporated within a unified stochastic model.

- 4.

Development of a unified mechanistic stochastic transport framework: That links memory, damping, and multi-scale heterogeneity to underlying porous media physics, providing an interpretable and flexible tool for simulating CO2 migration in low-permeability formations.

- 5.

Demonstration of the WA-DFBM approach using experimental diffusion data: Highlighting improved representation of signal variability, attenuation behavior, and temporal correlation when compared with traditional stochastic and deterministic models.

This work therefore bridges wavelet-based multi-scale analysis with physically motivated stochastic modeling, offering new mechanistic insight into CO2 transport processes in fractal porous media.

2. Methodology

The methodology of this study integrates physical insights from core-scale CO2-oil displacement experiments with a physics-aware stochastic modeling framework. Although the experiments are conducted at the core scale (decimeter to meter scale), the recorded pressure-diffusion signals inherently contain signatures of pore-scale fractal heterogeneity, long-memory effects, and multi-scale transport fluctuations. The goal of this section is therefore to build an effective cross-scale representation that links the observable core-scale diffusion behavior to the underlying pore-scale statistical mechanisms.

To achieve this, we progressively construct the Wavelet-Assisted Damped Fractional Brownian Motion (WA-DFBM) framework through the following steps:

- 1.

Physical interpretation of CO

2 transport in fractal porous media (

Section 2.1)

Core-scale displacement experiments exhibit non-stationary pressure increments, long-range dependency, and scale-dependent attenuation,behaviors commonly associated with transport in fractal pore networks. These physical observations motivate the choice of fractional stochastic models.

- 2.

Fractional Brownian motion for long-memory diffusion (

Section 2.2)

FBM provides a mathematically rigorous representation of persistent or anti-persistent correlations in diffusion signals, capturing long-range memory induced by heterogeneous pore connectivity.

- 3.

Damped FBM to incorporate transient attenuation (

Section 2.3)

The CO2 displacement process exhibits stage-dependent attenuation, particularly visible during the transition between mixed-phase formation, mixed-phase displacement, and gas post-breakthrough. Introducing an exponential damping term stabilizes low-frequency variance and mimics the dissipative transport behavior observed in experiments.

- 4.

Wavelet-based decomposition to represent multi-scale heterogeneity (

Section 2.4)

Wavelet transforms isolate localized, scale-dependent fluctuations, enabling the model to distinguish contributions from micro-scale (pore-level) and meso-scale (flow-zone-level) features embedded in core-scale measurements.

- 5.

Parameter estimation and signal reconstruction (

Section 2.5)

Hurst exponent, damping rate, and wavelet coefficients are estimated from experiments, allowing reconstruction of the WA-DFBM signal that matches the observed multi-scale diffusion characteristics.

- 6.

Numerical application and comparison with physical experiments (

Section 2.6)

Finally, the developed framework is applied to simulate CO2 diffusion dynamics along the long core, and the reconstructed signals are compared with experimental pressure profiles across different displacement stages.

This step-wise methodology ensures a coherent integration of physical mechanisms and stochastic modeling tools. It provides a unified cross-scale representation where: FBM captures long-memory transport, damping characterizes transient attenuation, and wavelets resolve multi-scale heterogeneity. Together, they form the WA-DFBM model used to analyze and predict CO2 diffusion behavior in fractal porous media.

To ensure clarity and consistency in notation, all variables and parameters used in the modeling framework are summarized in

Table A1 of

Appendix A.1.

2.1. Physical Motivation and Modeling Rationale

2.1.1. Physical nature of CO2 transport in fractal porous media

Natural and engineered porous media frequently exhibit fractal or multi-fractal pore architectures, where pore size distribution, connectivity, and surface roughness display scale-invariant characteristics across several orders of magnitude [

28,

29]. Such fractal heterogeneity gives rise to tortuous flow pathways, broad distributions of pore-throat lengths, and hierarchical pore networks, all of which are known to produce anomalous diffusion behaviors and long-memory transport signatures in fluid displacement processes. As a result, CO

2 migration in geological formations is governed by a combination of pore-scale structural complexity, heterogeneity, and non-equilibrium transport behaviors. In fractal porous media, the pore-throat network exhibits self-similar geometry over a broad range of spatial scales, resulting in highly irregular flow paths, broad pore-size distributions, and intermittent transport events [

3,

13]. These geometric features fundamentally distinguish CO

2 diffusion from classical Fickian processes, making its transport behavior intrinsically multi-scale, memory-dependent, and dynamically variable.

First, the presence of fractal pore structures leads to anomalous diffusion, where the mean-square displacement deviates from the linear time scaling expected in Brownian transport. Such deviations have been reported in both molecular diffusion experiments and numerical simulations in complex porous systems [

17,

18]. These observations indicate the existence of long-range temporal correlations and history-dependent motion, characteristic of non-Fickian processes.

Second, CO

2 injection and subsequent diffusion are often accompanied by transient attenuation, relaxation, or dissipative responses, caused by pressure dissipation, capillary trapping, and pore-scale energy loss mechanisms. These effects produce diffusion signals with decaying amplitudes, non-stationary variability, or white-noise-like intervals, which cannot be adequately represented by classical fractional Brownian motion alone [

26,

30]. The presence of these dissipative behaviors highlights the need to incorporate damping mechanisms into stochastic transport descriptions.

Third, the inherently heterogeneous pore networks induce localized transport fluctuations and multi-scale variability. Experimental and numerical studies show that CO

2 displacement in irregular pore channels can produce abrupt changes in diffusion rates, scale-dependent variance, and intermittent high-frequency deviations [

9,

31]. Such phenomena emerge from the hierarchical organization of pore structures and require mathematical tools capable of isolating local irregularities while preserving global transport trends.

2.1.2. From transport features to stochastic modeling requirements

The distinctive transport behaviors described above impose specific requirements on any mathematical framework intended to model CO2 migration in fractal porous media. In particular, the coexistence of long-memory effects, transient attenuation phenomena, and multi-scale structural variability requires a stochastic model capable of simultaneously representing correlation persistence, dissipative behavior, and localized fluctuations. These transport features naturally map onto the three components of the wavelet-assisted damped fractional Brownian motion (WA-DFBM) framework adopted in this study.

(1) Long-memory behavior : fractional Brownian motion (FBM)

Fractal pore structures lead to persistent correlations in particle displacements, where CO2 diffusion retains statistical dependence on past transport history. This is reflected in anomalous mean-square displacement scaling and time-correlated transport signals commonly observed in irregular porous networks. Such behavior cannot be captured by classical Brownian motion, which assumes independent increments. FBM, characterized by the Hurst exponent H, provides a natural description of these long-range temporal correlations. Therefore, FBM forms the foundational stochastic process for representing memory-dependent transport in this work.

(2) Transient attenuation and dissipative responses: damping term

Experimental CO2 diffusion signals frequently exhibit amplitude decay, relaxation behavior, or non-stationary variance trends due to pressure dissipation, pore-scale trapping, and energy-loss mechanisms. Classical FBM lacks the ability to represent such dissipative dynamics because its variance grows monotonically with time and contains no mechanism for attenuation. Introducing an exponential damping factor allows the model to account for transient decay, enabling the reproduction of short-term relaxation and white-noise-like intervals reported in porous media diffusion experiments. This damping term is thus essential for capturing the non-equilibrium, dissipative aspects of CO2 transport.

(3) Multi-scale heterogeneity and localized irregularities: wavelet decomposition

The hierarchical and scale-invariant nature of fractal pore structures generates transport signals with localized fluctuations, intermittent bursts, and scale-dependent variance. Traditional stochastic models, whether Brownian or fractional, provide only global statistical behavior and cannot isolate short-lived fluctuations or identify contributions from different spatial or temporal scales. Wavelet transforms, by contrast, offer a multi-resolution representation that decomposes diffusion signals into localized components while preserving global structure. By coupling wavelet decomposition with DFBM, the resulting WA-DFBM model captures both broad-scale correlation patterns and fine-scale irregularities inherent to fractal porous media.

Taken together, these considerations show that the physical characteristics of CO2 migration in fractal pore networks naturally motivate a composite stochastic model. FBM accounts for long-memory transport, the damping term incorporates dissipative attenuation, and wavelet decomposition resolves multi-scale heterogeneity. The WA-DFBM framework thus emerges as a physically grounded and mechanistically consistent representation of CO2 diffusion in complex porous media.

2.2. Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) for Long-Memory Transport

2.2.1. Definition and statistical properties of FBM

Fractional Brownian motion (FBM), first introduced by Mandelbrot and Van Ness (1968), generalizes classical Brownian motion by incorporating long-range temporal dependence through a tunable memory parameter [

13], the Hurst exponent H. Unlike standard Brownian motion where increments are independent, FBM allows correlations that persist over multiple time scales, making it particularly suitable for modeling anomalous diffusion phenomena arising in fractal porous media [

25].

Mathematically, FBM

is a zero-mean Gaussian process defined by the stochastic integral representation:

The random function

can be approximately represented as the moving average of

, where past increments of

are weighted by a kernel function

,

denotes standard Brownian motion and

is the Gamma function. This representation highlights the essential feature of FBM: past increments influence future evolution via power-law memory kernels, producing the long-range dependence often observed in CO

2 migration through tortuous pore networks.

The covariance function of FBM is given by

The Hurst exponent

serves as a key parameter that generalizes classical Brownian motion by quantifying the degree of long-range dependence in a stochastic process. Which directly encodes persistent temporal correlations when

(super-diffusive behavior) and anti-persistent dynamics when

. This property is consistent with experimental and numerical observations of anomalous CO

2 diffusion in complex, scale-invariant porous structures where transport rates exhibit power-law deviations from classical Fickian scaling .

FBM also exhibits self-affinity, an important characteristic for representing transport in fractal media. For any scaling factor

,

where "

" denotes equality in distribution. This scale-invariant property mirrors the fractal organization of pore geometries, where structural features repeat across multiple spatial scales and induce similarly scale-invariant transport fluctuations.

Another key property is the non-stationarity of increments. The variance of the increment over an interval

is:

The variance of the increment

over a time interval

depends on the length of the interval and scales as a power-law function of the time separation, H governs the scaling behavior of the variance, indicating that diffusion spreads with a power-law dependence on the temporal separation

. This behavior has been widely reported in subsurface transport experiments where CO

2 diffusion rates evolve non-linearly due to pore-scale heterogeneity and memory effects [

11].

The spectral characteristics of FBM further reinforce its suitability for porous media applications. The power spectral density (PSD) obeys:

Where

is the power spectral density at frequency

, A is a normalization constant that depends on both H and the time interval, and

denotes the magnitude of the frequency, showing that low-frequency (large-scale) components dominate when

. Such spectral concentration reflects slowly varying large-scale structures in diffusion signals, consistent with the influence of micro-scale and macro-scale heterogeneity in geological formations.

In summary, FBM provides a mathematically rigorous and physically interpretable basis for modeling CO2 transport in fractal porous media. Its intrinsic long-range dependence, self-affinity, and power-law variance scaling make it an appropriate foundational process for representing memory-driven, non-Fickian diffusion. These properties justify its use as the core component of the WA-DFBM framework developed in this work.

2.2.2. Physical interpretation for porous media transport

The transport of CO2 in porous media, particularly in the context of fractal and multi-scale heterogeneity, cannot be fully understood without integrating both mathematical and physical perspectives. The key challenge lies in how the transport model reflects the inherent features of the porous media, specifically, the scale-invariant pore structures, the fractal nature of connectivity, and the long-range temporal correlations in the diffusion process. In this section, we bridge the gap between these physical characteristics and their mathematical representation via fractional Brownian motion (FBM).

Long-Memory and Anomalous Diffusion

As discussed in

Section 2.2.1, FBM captures long-range temporal correlations that are a hallmark of anomalous diffusion observed in fractal porous media. In traditional diffusion processes, the mean square displacement (MSD) increases linearly with time, representing classical Brownian motion. However, in fractal media, such as those encountered during CO

2 migration in geological formations, the MSD often follows a power-law scaling instead of a linear growth, indicating the presence of anomalous diffusion. This is where FBM becomes particularly useful, as it incorporates the Hurst exponent H to model the memory effects, that is, the dependence of future displacements on the history of past displacements. The Hurst exponent, which can vary between 0 and 1, dictates the persistence of these correlations: when

, the process exhibits positive long-range dependence (persistent behavior), and when

, it shows anti-persistence (reversion to mean behavior).

The anomalous diffusion observed in CO2 transport is caused by the tortuous, irregular pore structure and fractal-like pore-throat networks, which force the migrating fluid to follow non-linear paths. The fractal geometry of the medium introduces non-Fickian behaviors, where CO2 molecules experience a non-uniform diffusivity, with varying local transport rates across different scales. This leads to slower diffusion and anomalous scaling of the diffusion front.

Dissipative and Relaxation Effects

As mentioned earlier, transient attenuation and relaxation effects are crucial for accurately modeling CO2 transport. These effects are a direct consequence of the porous media's heterogeneity, where CO2 diffusion is influenced by pressure dissipation, capillary trapping, and pore-scale energy loss. In low-permeability formations, CO2 faces significant resistance due to tight pore spaces and pore throat constrictions, which result in delayed relaxation and damping of the diffusion signal over time.

The damping term introduced in the WA-DFBM framework accounts for these dissipative effects by introducing an exponential decay in the amplitude of the CO2 signal. This mathematical modification allows the model to reflect the fact that the diffusion process in such media does not continue indefinitely but eventually slows down due to the energy lost in the system (e.g., due to friction between the fluid and the pore walls). The exponential damping coefficient captures the attenuation rate, which is essential for modeling the non-stationary behavior of the CO2 concentration over time, as observed in experiments.

This exponential attenuation in the WA-DFBM model simulates the relaxation dynamics that occur when the CO

2 transport transitions from initial displacement to equilibrium, where local pressure differences and capillary forces drive the system towards a steady state. The inclusion of this damping term makes the model more reflective of real-world CO

2 migration behavior in geological reservoirs, where dissipation of energy over time governs the rate at which CO

2 front propagation slows down. Fractal porous media also exhibit multi-scale structural heterogeneity, which manifests as transport fluctuations spanning multiple temporal scales. Capturing this multi-scale behavior requires a decomposition tool capable of isolating localized features across scales. This motivates introducing wavelet-assisted analysis, whose methodological role will be established in

Section 2.4.

2.3. Damped Fractional Brownian Motion (DFBM)

2.3.1. Mathematical formulation of DFBM with exponential damping

Fractional Brownian motion (FBM) provides a flexible framework for representing long-range temporal memory, but its unbounded variance and persistent correlation at long time scales limit its applicability for physical diffusion processes. In natural porous media, CO2 transport often exhibits transient attenuation and relaxation, which cannot be captured by classical FBM. To incorporate these dissipative effects, a damping term is embedded into the stochastic differential equation of FBM, yielding the damped fractional Brownian motion (DFBM) process.

Let denote a standard FBM with Hurst exponent . The DFBM state variable

is defined through the modified stochastic differential equation:

Where,

is the drift term,typically assumed to be zero for diffusion-dominated systems;

quantifies the intrinsic fluctuation strength;

is the damping coefficient controlling the rate of exponential relaxation;

modulates the FBM increments, gradually attenuating their magnitude over time.

Integrating Eq. (6) yields the explicit form:

which reveals that DFBM acts as an exponentially weighted moving average of FBM increments. This weighting kernel introduces a temporal "forgetting mechanism" that suppresses the influence of distant past increments, an essential modification for representing physical diffusion processes that relax toward equilibrium.

The variance of the DFBM process follows [

32]:

where

is the Mittag-Leffler function. For large t, Eq. (8) approaches a finite asymptote, unlike classical FBM whose variance diverges as

. This boundedness is crucial for modeling diffusion in porous media.

Thus, DFBM mathematically extends FBM by introducing a stabilizing exponential kernel, producing a stochastic process capable of capturing both long-range dependence and dissipative attenuation.

2.3.2. Physical meaning of the damping parameter

The damping coefficient plays a central role in enabling DFBM to represent physically realistic CO2 transport in porous media. Its physical interpretation is directly tied to three key mechanisms inherent to subsurface flow:

- 1.

Energy dissipation during CO2 migration

As CO2 propagates through complex pore structures, pressure gradients diminish, viscous forces dissipate energy, and molecular motion becomes progressively less correlated. The exponential term mathematically reproduces this physical attenuation, ensuring that past fluctuations exert diminishing influence on current behavior.

- 2.

Pore-scale trapping and relaxation mechanisms

In heterogeneous or fractal porous media, CO2 molecules undergo intermittent trapping, residence-time variability, and partial stagnation. These phenomena naturally generate relaxation behavior and "memory loss", consistent with an exponential decay kernel. Thus, corresponds to an effective relaxation timescale.

- 3.

Stabilization of long-range memory (bounded variance)

Standard FBM carries persistent correlations indefinitely, which contradicts physical diffusion processes that eventually approach a quasi-steady regime. Damping truncates the memory:

For small : long-range dependence remains dominant (FBM behavior).

For large : correlations decay, preventing unbounded variance growth.

This transition accurately reflects real CO2 diffusion datasets, which often display early-time anomalous diffusion followed by late-time stabilization.

In summary, FBM represents the memory effect and the damping term governs relaxation. Therefore, the parameter serves as a physically interpretable quantity linking stochastic dynamics to pore-scale dissipation and relaxation processes.

2.3.3. Limiting cases and relation to classical FBM

The DFBM formulation smoothly connects to several well-known stochastic processes through limiting cases of the damping coefficient . This demonstrates mathematical consistency and clarifies the physical regimes represented by the model.

Case 1: Classical fractional Brownian motion

Setting eliminates the exponential kernel in Eq. (7): ,which reduces DFBM to standard FBM.

Physical meaning: No dissipation, idealized anomalous diffusion with infinite memory. This limit corresponds to early-time CO2 movement before attenuation becomes significant.

Case 2: White-noise-driven Ornstein-Uhlenbeck-like process

For very large , the exponential kernel collapses to an impulse: for leaving only short-range correlations. The variance converges to a finite constant, indicating strong suppression of memory.

Physical meaning:Strong relaxation, heavy dissipation, and loss of long-range temporal structure, analogous to diffusion in highly resistive or stagnant zones.

Case 3: Damped classical Brownian motion

When the Hurst exponent equals , FBM reduces to standard Brownian motion. Then Eq. (7) becomes the well-known exponentially damped Brownian process.

Physical meaning: Represents normal diffusion with exponential relaxation (e.g.,classical pressure diffusion).

Case 4: Long-time asymptotic behavior

As , the variance of DFBM converges to a constant:, demonstrating its suitability for physical systems approaching equilibrium.

In summary, DFBM is a unifying framework spanning FBM, damped diffusion,and OU-type behavior. Its flexibility enables representation of CO2 transport across a spectrum of physical regimes, from early anomalous spreading to late-time relaxation.

2.4. Integrating Wavelet Transform into DFBM (WA-DFBM Framework)

The CO2 pressure signals measured in long-core displacement experiments contain multi-scale features arising from heterogeneous flow pathways, transient local fluctuations, and long-memory diffusion behavior. Standard DFBM captures long-range dependence and attenuation, yet it lacks the ability to isolate localized events or represent the scale-dependent heterogeneity inherent in porous media. To address this limitation, wavelet decomposition is integrated into the DFBM formulation, forming the WA-DFBM framework. This subsection introduces the mathematical foundation of wavelet transforms, explains why wavelets are physically appropriate for heterogeneous reservoirs, and presents the coupling strategy leading to the WA-DFBM model.

2.4.1. Discrete wavelet transform of diffusion signals

Wavelet transforms provide a localized, multi-resolution representation of temporal signals, enabling the decomposition of a diffusion process into different frequency-scale components. The mathematical foundation is given by the continuous wavelet transform (CWT). For a signal

, the CWT is defined as:

where

is the scale (dilation),

is the translation, and

is the complex conjugate of the dilated-translated mother wavelet:

This decomposition yields a set of coefficients

that describe the distribution of energy across scales. When discretized, the wavelet coefficients

at level

and location

reconstruct the signal as:

providing a multi-resolution representation capable of capturing both global and localized dynamic behavior.

2.4.2. Role of wavelets in representing multi-scale heterogeneity

The porous structure of low-permeability or fractal reservoirs exhibits a wide range of pore sizes, from micro-pores to macro-fractures, each associated with distinct diffusion rates. These multi-scale flow structures generate heterogeneous pressure fluctuations: CO2 migrates more rapidly through macro-pore clusters, whereas its movement slows and becomes more irregular in micro-pore regions. Consequently, the measured pressure signals exhibit multi-scale variability, localized transient perturbations, and intermittent fluctuations that cannot be captured adequately by a single-scale stochastic model. Wavelet decomposition is ideally suited to represent this behavior because:

Localized fluctuations detection: wavelets isolate short-lived pressure perturbations caused by pore-scale bottlenecks or dynamic CO2-oil interactions.

Multi-scale heterogeneity representation: the decomposition separates macro-scale displacement trends from fine-scale diffusion irregularities.

Multi-scale effects: macro-fracture-driven rapid propagation appears at low-frequency scales, while micro-pore diffusion manifests at higher frequencies.

Noise suppression: high-frequency measurement noise can be removed selectively without altering physically meaningful long-memory behavior.

In heterogeneous geological media, where flow properties vary across spatial and temporal scales, the wavelet transform acts as a "mathematical microscope" offering simultaneous access to both long-term and localized transport dynamics. This makes wavelet analysis physically consistent with the nature of CO2 migration in multi-scale porous structures and provides the necessary foundation for coupling with DFBM.

2.4.3. Coupling wavelet decomposition with DFBM (WA-DFBM)

Arneodo et al.[

25] pioneered the use of wavelet analysis as a "mathematical microscope" to examine scale-invariant structures in fluid flow. Building on this foundation, Flandrin and Adler[

3,

33] developed the spectral framework necessary for applying second-order wavelet techniques to FBM processes. Albeverio et al.[

30]further established connections between FBM, operator theory, and wavelet bases, enabling more rigorous analytical treatments of diffusion phenomena.

To incorporate multi-scale heterogeneity into the DFBM framework, the wavelet transform is applied directly to the damped FBM signal

. Its wavelet transform is given by:

where:

represents the damping effect, governing long-time relaxation,

denotes the FBM increment with Hurst index

, contributing long-range dependence.

Wavelet basis selection.

The Morlet wavelet is employed due to its superior localization in both time and frequency domains, which is essential for detecting transient fluctuations in diffusion signals. The Morlet wavelet is expressed as:

where the Gaussian envelope

ensures temporal localization, and the oscillatory term encodes frequency information.

Derivation of the WA-DFBM model.

Applying wavelet decomposition to the DFBM process yields a scale-dependent representation in terms of wavelet coefficients

. Combining the exponential damping with the multi-scale expansion leads to the WA-DFBM formulation:

This representation integrates three essential physical mechanisms: FBM (Hurst index

), long-memory diffusion, reflecting persistent correlations in CO

2 transport. Damping parameter

, attenuation, representing pressure relaxation and dissipation in porous media. Wavelet basis

, multi-scale heterogeneity, capturing localized fluctuations and scale-dependent diffusion pathways. Together, these components create a physics-aware stochastic model that jointly represents long-range dependence, attenuation behavior, and multi-scale structural variability in CO

2 displacement through heterogeneous porous formations. This coupling is essential for accurately reproducing the dynamic features observed in experimental pressure-time signals.

2.5. Parameter Estimation and Algorithm Implementation

The WA-DFBM model integrates fractional long-memory dynamics, damping-controlled transient attenuation, and wavelet-based multi-scale representation. To make the model operational and applicable to real CO2-coreflood diffusion signals, this section develops a complete parameter-estimation workflow and the corresponding algorithmic implementation. The goal is to extract physically interpretable parameters, primarily the Hurst exponent H, damping coefficient , and wavelet-scale coefficients, from the measured core-scale pressure-diffusion data.

2.5.1. Preprocessing and wavelet-based noise filtering

Raw pressure-diffusion signals obtained from long-core CO2 displacement experiments inevitably contain measurement noise, high-frequency artifacts, and non-stationary disturbances. Prior to parameter inference, the signal must therefore be preprocessed.

- (1)

Baseline correction and detrending

The recorded pressure series may include instrument drift or low-frequency bias. A polynomial detrending or moving-window mean subtraction is applied to ensure that the remaining signal reflects true diffusion dynamics.

- (2)

Wavelet denoising

Wavelets provide a natural decomposition of the diffusion signal into multiple temporal resolutions. A discrete wavelet transform (DWT) Eq.(11) is applied. Where are wavelet coefficients at scale and position . Soft-thresholding or scale-adaptive shrinkage is performed on high-frequency coefficients, suppressing instrument noise while preserving physically meaningful fluctuations.

- (3)

Multi-scale separation. Different wavelet scales emphasize different physical processes:

low-frequency scales: long-range correlation, macro-scale propagation;

mid-frequency scales: transient attenuation behavior relevant to;

high-frequency scales: pore-scale fluctuations and micro-pore restrictions.

This decomposition is essential because the WA-DFBM parameters H and correspond to distinct frequency regimes.

2.5.2. Estimation of Hurst exponent and damping coefficient

Following preprocessing, the two principal model parameters: Hurst exponent H and damping coefficient , are estimated from the wavelet-filtered diffusion signal.

- (1)

Estimation of the Hurst exponent H

The long-memory and correlation structure of the diffusion signal is quantified using FBM-based methods. Several estimators are applicable (e.g., wavelet-based logscale regression, rescaled-range analysis), but the wavelet estimator is preferred due to robustness against non-stationarity. The variance of wavelet coefficients at scale

satisfies:

Thus, a log-log regression gives:

This provides a reliable estimate of the long-range dependence encoded in the signal.

- (2)

Estimation of the damping parameter

After isolating the low-frequency smoothed signal, the transient attenuation portion is modeled by the exponential term in DFBM:

A regression in the log-amplitude domain is used:

yielding an estimate of

.

This parameter captures the dissipation behavior observed experimentally during the mixed-phase formation and stabilization stages. The detailed algorithmic workflow is presented in

Appendix A.2 for completeness.

2.5.3. Reconstruction of WA-DFBM and prediction of diffusion signals

With parameters determined, the diffusion signal is reconstructed using the WA-DFBM formulation (14). This reconstruction process includes:

- (1)

Synthesis across wavelet scales

All wavelet scales contributing to micro-scale fluctuations, intermediate attenuation dynamics, and macro-scale trends are recombined. The resulting signal reflects both persistent long-term correlations and localized transient features.

- (2)

Integration of damping characteristics

The exponential factor shapes the temporal envelope, ensuring that the model captures:

rapid fluctuation decay during the mixed-phase formation stage;

quasi-steady oscillations during mixed-phase displacement;

and abrupt transition at gas breakthrough.

- (3)

Multi-stage diffusion prediction

Using the estimated parameters, the reconstructed WA-DFBM signal can predict pressure-diffusion evolution across the full three-stage displacement process identified in

Section 2.6:

Stage 1: Mixed-phase formation;

Stage 2: Mixed-phase displacement;

Stage 3: Gas post-breakthrough

This predictive capability allows the WA-DFBM model to emulate both the short-time transient effects and long-time persistent diffusion behavior observed in CO2 migration through fractal porous cores.

2.6. Simulation and Application

This section presents the numerical simulation and physical interpretation of CO

2 migration in low-permeability, fractal sandstone reservoirs. The simulations employ the calibrated WA-DFBM model introduced in

Section 2.5, aiming to reproduce and interpret the multi-stage diffusion behavior observed in long-core CO

2 displacement experiments.

2.6.1. Reservoir characteristics and scale definition

The target reservoirs are located in the Central Uplift Belt of the Dongpu Depression within the Zhongyuan Oilfield, operated by SINOPEC. These formations are characterized by ultra-low permeability and constitute a key development zone for enhanced oil recovery. The reservoir lithology is dominated by feldspar coarse siltstone and quartz-rich fine sandstone, with tight cementation and pronounced diagenetic compaction.

The reservoir lies at depths of 3200-3700 m and contains approximately 5.4 km2 of oil-bearing area. Key reservoir parameters include an original formation pressure of 34.5 MPa, a bubble-point pressure of 22.65 MPa, a formation temperature of 114℃, average porosity of 13%, and a mean permeability of . The crude oil exhibits a viscosity of 0.28 mPa·s at reservoir conditions and a gas-oil ratio of 160 m³/m³.The saline formation water has a salinity of 28×10⁴ mg/L. These properties indicate a typical tight, heterogeneous sandstone system with fractal-like pore structure and broad pore-size distribution. Core-scale behavior (meters-decimeters) is governed by pore-scale heterogeneity (microns-tens of microns), motivating the use of a cross-scale stochastic model such as WA-DFBM to extract micro-scale diffusion signatures from core-scale pressure measurements.

2.6.2. Physical displacement stages and their implications for WA-DFBM modeling

Physical conceptual model

The one-dimensional core-flood experiment exhibits three characteristic stages of CO

2 migration, each reflecting distinct physical mechanisms of multi-phase displacement in fractal porous media. These stages not only describe the physical evolution of the displacement process but also provide direct mechanistic motivation for the components of the WA-DFBM framework developed in

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3.

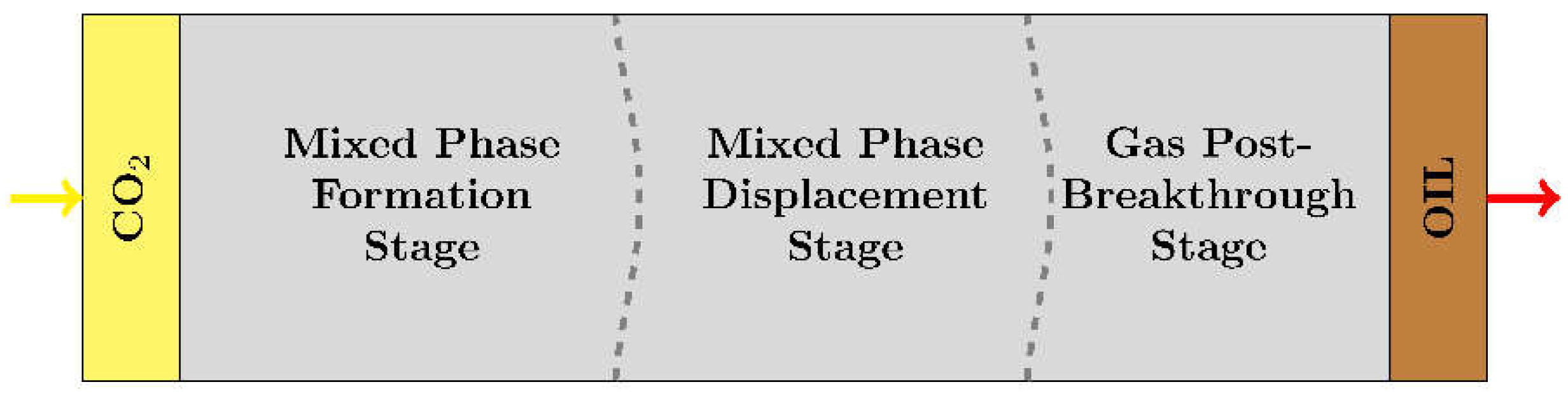

As illustrated in

Figure 1, in the conceptual one-dimensional core-flood model, the long core mixed phase displacement process is divided into three distinct stages:

- (1)

Mixed Phase Formation Stage: Correspond to the initial gas injection period, where CO2 begins to penetrate the porous medium and interact with the resident oil, pressure propagation is dominated by viscous forces near the injection face, resulting in a gradual and spatially non-uniform pressure rise along the core.

- (2)

Mixed Phase Displacement Stage: Characterized by piston-like displacement behavior, during which CO2 and oil coexist and compete for pore space under pressure-driven flow.

- (3)

Gas Post-Breakthrough Stage: Once CO2 breaks through at the production end, gas mobility sharply increases and the flow regime transitions to gas-dominated displacement, the pressure at all monitoring points experiences a rapid decline toward a new equilibrium, when gas becomes the dominant phase and displacement efficiency gradually declines.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the one-dimensional CO2-oil mixed-phase displacement process in a long-core experiment. The displacement evolves through three characteristic stages: (i) Mixed Phase Formation Stage, (ii) Mixed Phase Displacement Stage, and (iii) Gas Post-Breakthrough Stage. These stages represent distinct flow mechanisms and provide direct physical motivation for the WA-DFBM modeling framework.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the one-dimensional CO2-oil mixed-phase displacement process in a long-core experiment. The displacement evolves through three characteristic stages: (i) Mixed Phase Formation Stage, (ii) Mixed Phase Displacement Stage, and (iii) Gas Post-Breakthrough Stage. These stages represent distinct flow mechanisms and provide direct physical motivation for the WA-DFBM modeling framework.

The implications CO2 displacement stages for WA-DFBM modeling

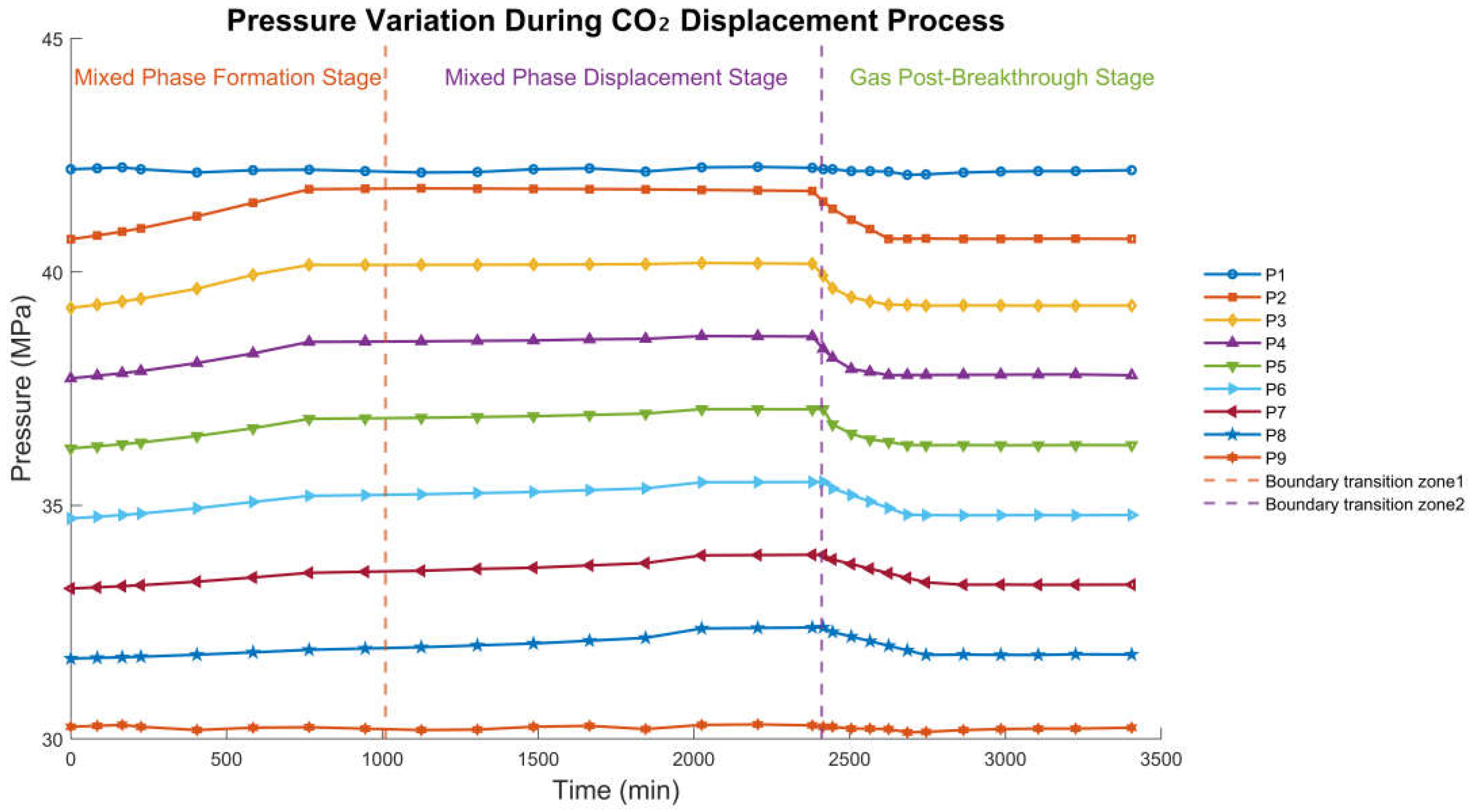

The pressure-time responses (shown in

Figure 2) observed during the long-core CO

2 flooding experiment with ranges of effective stress (5-25MPa), a constant injection rate of approximately 1.304

, and system pressure varying from 30-42 MPa during CO

2 displacement. This configuration ensured steady-state flow and allowed pressure evolution to be monitored continuously along the core. These physical stages map directly onto the stochastic structures captured by the WA-DFBM model, providing a mechanistic basis for selecting fractional Brownian memory, damping, and wavelet-based multi-scale decomposition.

Stage 1: Mixed Phase Formation Stage (0-~1000 min)

Experimental characteristics: Pressure at all monitoring points gradually increases with time. The upstream section exhibits faster pressure buildup, while the downstream pressure remains near its initial level. Fluid configurations evolve rapidly and non-stationarily.

Physical interpretation: Injected CO2 first contacts crude oil, initiating oil swelling, CO2 dissolution, and reduction in inter-facial tension. Fluid viscosity decreases, and pressure propagation accelerates near the inlet. The displacement front is still developing, fluid configurations are not stabilized. Strong fluid-rock coupling and transient two-phase interactions yield non-stationary increments and early-stage transient attenuation.

Correspondence to WA-DFBM: The gradually stabilizing pressure and evolving increment statistics correspond to non-stationary increments of FBM at early time. Transient attenuation characterized by the exponential damping term in DFBM. The necessity of introducing a damping coefficient to represent early-stage relaxation of pressure perturbations.

Stage 2: Mixed Phase Displacement Stage (~1000–~2400 min)

Experimental characteristics: Pressure at each monitoring point becomes smoother and more stable. A mild increase or gradual stabilization occurs as the miscible zone advances downstream. Slight fluctuations remain due to reservoir heterogeneity.

Physical interpretation: A stable CO2-oil miscible zone forms and migrates downstream in a quasi-piston-like fashion. Viscosity continues to decrease, improving displacement efficiency. The miscible zone expands, and local pore-scale heterogeneity causes small yet persistent transport fluctuations. Multi-scale structural features influence local pressure perturbations.

Correspondence to WA-DFBM: Long-range temporal dependence due to continuous miscible-zone advance, modeled by FBM with . Wavelet decomposition captures localized, pore-scale fluctuations. Moderate damping as pressure propagation approaches a quasi-steady regime. These justify the use of the wavelet-assisted DFBM formulation to simultaneously capture: long-memory trend (FBM), localized multi-scale deviations (wavelets), slowly decaying transient effects (damping).

Stage 3: Gas Post-Breakthrough Stage (~2400 min onward)

Experimental characteristics: All pressure points exhibit a sharp drop, followed by a new stable pressure level. Mid-section pressure curves show slight declines, reflecting gas-oil separation and preferential gas pathways.

Physical interpretation: CO2 mobility sharply increases after breakthrough, gas rapidly flows through high-permeability channels. Two-phase interface collapses, and oil is bypassed in lower-mobility zones. The system transitions to a gas-dominated flow regime with pronounced heterogeneity effects. A white-noise-like response emerges as long-range correlation temporarily diminishes during rapid pressure equilibrium.

Correspondence to WA-DFBM: Low-frequency attenuation due to relaxation of long-range structure, captured by damping term. High-frequency fluctuations caused by rapid gas migration, wavelet representation. Temporary weakening of long-range correlation, consistent with the behavior of with damping as moderate/high. This stage provides direct physical evidence of why FBM alone is insufficient and a damped formulation is required to model late-stage CO2 transport.

The three-stage evolution of pressure propagation directly reflects the underlying CO2 transport mechanisms in heterogeneous porous media. The mixed-phase formation stage introduces strong non-stationarity and transient attenuation, motivating the need for a damping mechanism beyond classical FBM. The mixed-phase displacement stage demonstrates long-range dependence and multi-scale fluctuations arising from pore-structure heterogeneity, aligning with FBM dynamics and justifying wavelet-based multi-resolution analysis. The post-breakthrough stage exhibits rapid pressure relaxation and near-white-noise characteristics due to gas-channel formation and fluid separation, further supporting the use of a damped FBM formulation with stabilized variance.

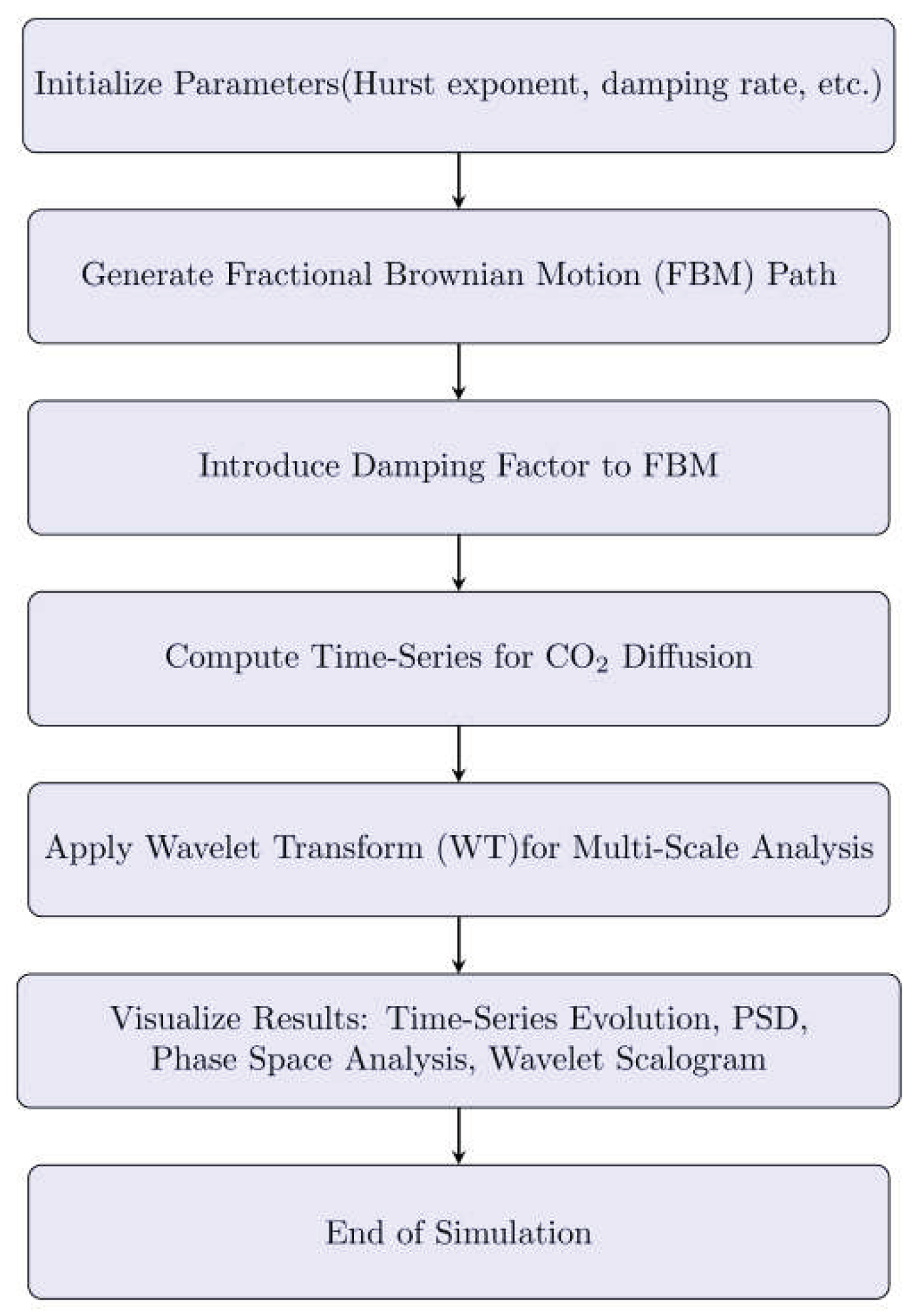

2.6.3. Simulation setup and boundary conditions

CO

2 diffusion in fractal porous media often deviates significantly from classical Fickian behavior. To simulate these dynamics, a stochastic time-series model WA-DFBM using MATLAB R2023a developed by us, integrates: FBM for long-memory transport trends, exponential damping for transient relaxation, and wavelet multi-resolution analysis for pore-scale fluctuations. The overall workflow is shown in

Figure 3, including parameter initialization, FBM path generation, damping application, wavelet transformation, and visualization of time-series, spectral, and phase-space characteristics.

- 1.

Boundary conditions follow the experiment:

Constant-rate CO2 injection at the inlet.

Open outlet boundary allowing free migration.

Nine pressure monitoring points (P1-P9) along the core.

No-flow lateral boundaries.

This configuration ensures consistency between model simulation and core-scale laboratory observations.

2.6.4. Performance metrics and comparison strategy

To evaluate WA-DFBM performance, simulation results are compared to experimental pressure curves using: Stage-wise trajectory matching;Power spectral density similarity; Wavelet scalogram feature alignment;and Phase-space structural consistency. These metrics quantify how well the model reproduces multi-scale diffusion features: long-memory trends, transient attenuation, and localized pore-scale fluctuations.

- 2.

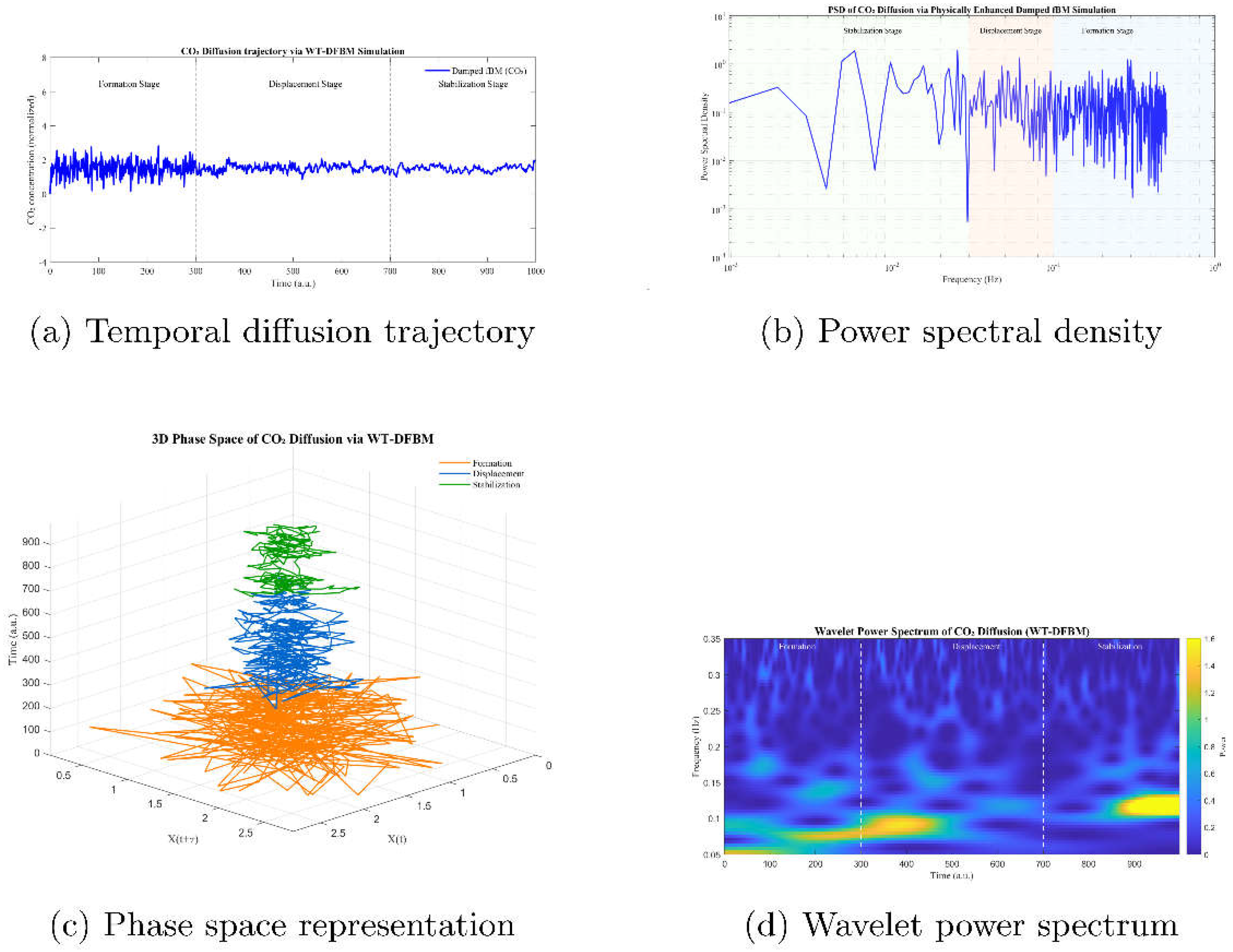

The simulation results(as shown in

Figure 4) are visualized through multiple analytical perspectives:

Time-series analysis captures the dynamic behavior of the diffusion process.

Power spectral density reveals the frequency-domain characteristics of the diffusion signal.

Phase-space analysis illustrates the stability and trajectory structure of the diffusion system.

Wavelet scalogram depicts the time-frequency evolution, enabling detection of multi-scale features and transient changes.

Figure 4.

Simulation of CO2 diffusion dynamics using the WA-DFBM model. (a) temporal diffusion trajectory; (b) power spectral density(PSD); (c) 3D phase space representation; (d) time frequency pattern via wavelet power spectrum.

Figure 4.

Simulation of CO2 diffusion dynamics using the WA-DFBM model. (a) temporal diffusion trajectory; (b) power spectral density(PSD); (c) 3D phase space representation; (d) time frequency pattern via wavelet power spectrum.

Figure 4(a) shows the normalized temporal trajectory of CO

2 concentration, revealing three characteristic stages: formation, displacement, and stabilization. As the system evolves, the oscillatory behavior becomes increasingly damped, indicating enhanced confinement and reduced diffusivity as CO

2 saturates the pore structure. These dynamics are consistent with pressure fluctuations and gas breakthrough patterns observed in tight sandstone formations.

Figure 4(b) presents the PSD of the signal, delineating a continuous transition is observed from broad-spectrum, high-frequency fluctuations to more localized spectral decay. This reflects the system's intrinsic multi-scale dissipative behavior, consistent with expectations for mixed-phase displacement processes.

Figure 4(c) displays 3D phase space representation. During the early formation stage, the trajectory exhibits irregular, high-amplitude loops, hallmarks of chaotic diffusion. As time progresses, the system evolves toward more compact attractors, indicating increasing spatial confinement and temporal correlation.

Figure 4(d) illustrates the wavelet power spectrum, capturing both the frequency content and its temporal localization. Distinct frequency bands emerge and decay across the diffusion stages, highlighting the model's capacity to resolve transient dynamics across multiple time scales.

3. Results and Discussion

This section evaluates the dynamic characteristics of CO2 diffusion predicted by the proposed WA-DFBM model and compares them with traditional modeling approaches and experimental observations. The discussion is structured into four parts: (i) time-series characteristics, (ii) migration and diffusion patterns, (iii) the relationship between multi-scale features and reservoir heterogeneity, and (iv) comprehensive model validation.

3.1. Analysis of Time Series Characteristics

The temporal trajectory of CO

2 diffusion predicted by the WA-DFBM model (

Figure 4(a)) displays distinct short-term fluctuations and long-term stabilization. This evolution naturally separates into three characteristic stages consistent with the physical displacement process:

Stage I Formation Stage (0-300 a.u.)

The early part of the curve shows the largest oscillation amplitude, reflecting instability caused by CO2-oil contact, transient pressure spikes, and intense pore-scale heterogeneity. Concentration fluctuates within a broad range (0-3), revealing under-damped stochastic behavior.

This corresponds to:

strong non-stationary increments,

high-frequency fluctuations decomposed via wavelets,

and transient attenuation associated with exponential damping.

Stage II Displacement Stage (300-700 a.u.)

The curve gradually transitions to a smoother profile as a miscible CO2-oil zone forms and migrates. Fluctuations narrow to approximately 1.3-2.2, indicating:

increased damping due to miscible sweeping,

reduced oscillatory amplitude,

sustained long-range dependence associated with .

This stage captures coherent CO2 mobility through pore networks while retaining multi-scale variability imposed by heterogeneous pore structure.

Stage III Stabilization Stage ( >700 a.u.)

As CO2 saturation approaches equilibrium, fluctuations are further suppressed and confined to a narrow band (1.7-2.0). The asymptotic limit is governed by:

Overall, WA-DFBM accurately reproduces the three-stage dynamic trend observed in core-scale CO2 displacement experiments.

3.2. Summary of CO2 Migration and Diffusion Patterns

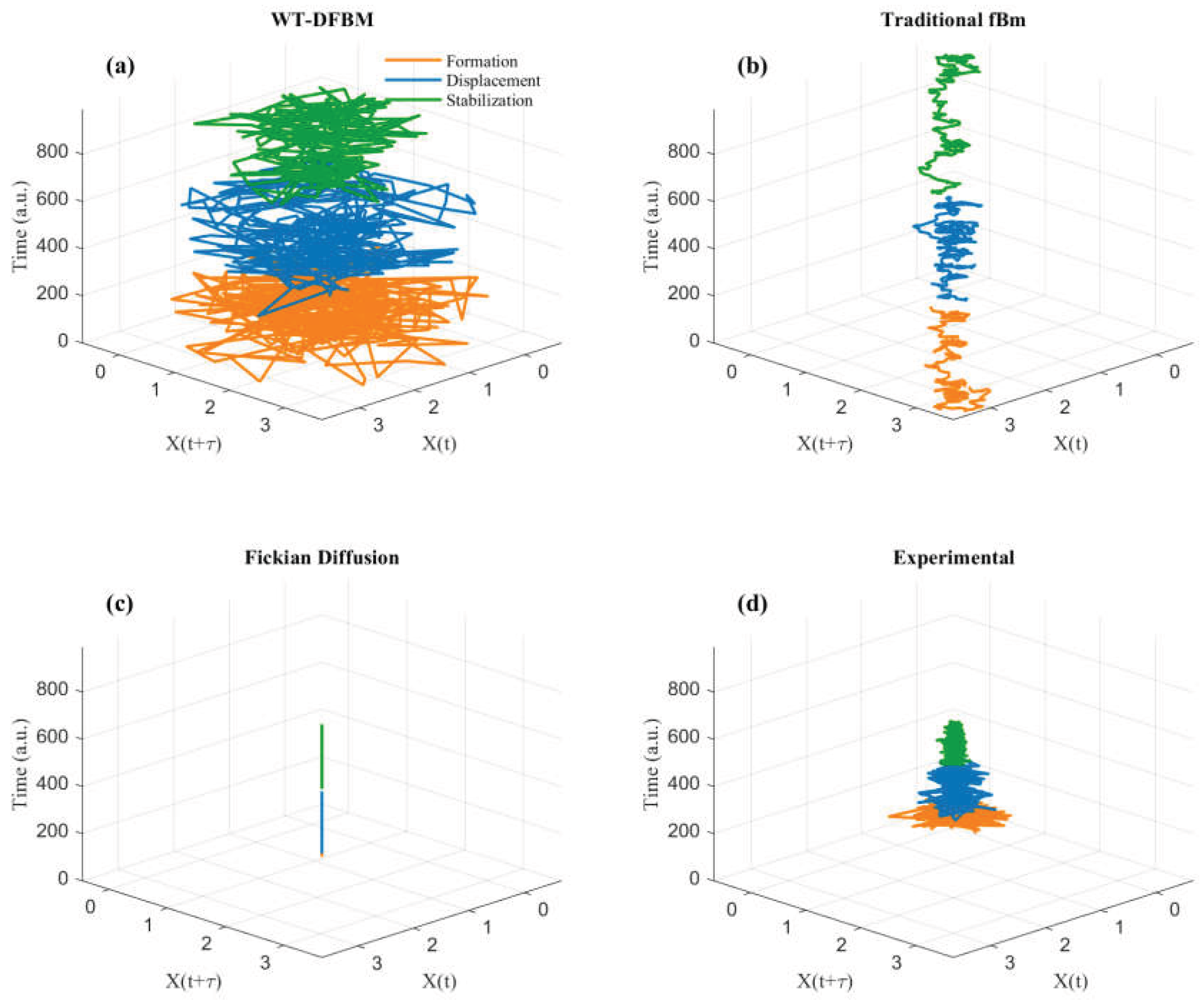

To further elucidate dynamic behavior of CO

2 during the injection and migration process, a 3D phase-space trajectory was reconstructed using the WA-DFBM model (

Figure 4(c)). Horizontal axes represent the embedding variables

, while vertical axis denotes time. The color segmentation distinguishes three stages.

- 1.

Formation stage : trajectory originates near the origin, exhibits large, erratic loops driven by stochastic fluctuations. Unstable front propagation, reflecting a sharp increase in CO2 concentration.

- 2.

Displacement stage : more structured dynamics associated with coherent CO2-oil interaction, partial flow toward equilibrium, reflecting the system's response to increasing damping, capturing the sweeping motion of the CO2 front through previously oil-saturated zones, with the curvature of the trajectory signifying a transition from chaotic to more streamlined, directed transport.

- 3.

Stabilization stage : trajectory converges toward a compact attractor, CO2 mobility declines as saturation stabilizes and further displacement becomes inefficient, reflecting reduced mobility and equilibrium saturation.

This 3D structure mirrors experimental pressure-front evolution, confirming that WA-DFBM captures both transient instability and long-range correlation during CO2 migration.

3.3. Correlation between Multi-scale Features and Reservoir Characteristics

The PSD (

Figure 4(b)) and wavelet power spectrum (

Figure 4(d)) of CO₂ diffusion signal across three primary dynamic regimes, revealing how multi-scale features evolve in response to reservoir conditions.

- 1.

Formation stage (high frequency,): CO₂ begins to invade isolated pore throats, generating steep spectrum fluctuations. High-frequency spectral features transient, chaotic motion governed by pore-scale barriers and heterogeneity. The time frequency landscape reveals bursts of energy concentrated in 0.05-0.10 Hz frequency band, with energy predominantly concentrated at lower frequencies,indicating long-duration processes and early gradual CO2 accumulation. Displacement stage (mid-frequency,): as CO₂ begins to mobilize and displace light hydrocarbon components (C₁–C₆) fluctuations in time-series signal become less erratic.Spectral energy begins to migrate toward a broader low-frequency(0.08-0.12 Hz), forming visible "islands" that gradually coalesce into a broad spectral plateau, reflecting CO2 advancement into brine-filled pore networks.

- 2.

Stabilization stage (low-frequency,): system approaches equilibrium, fluctuations significantly attenuated, and PSD curve shows a marked decline, particularly within range. As CO2 mobility decreases, saturation stabilizes, spectrum flattens further, especially at frequencies below Hz, indicating that long-duration fluctuations have largely dissipated. Wavelet power becomes highly localized around(0.10-0.12Hz), and the scalogram exhibits diminished power intensity and weakened oscillatory signatures. These signatures reflect the near-complete occupancy of pore spaces by CO2 and the resulting decline in pressure gradients.

Thus, the multi-scale decomposition effectively links dynamic diffusion patterns with pore-scale heterogeneity and core-scale transport behavior.

3.4. Model Validation

To evaluate the reliability and applicability of the proposed WA-DFBM model in capturing CO2 diffusion dynamics, a two-pronged validation strategy was implemented. First, we conducted a theoretical analysis, deriving the model's expected value and variance to confirm its mathematical consistency. Second, we carried out a comparative assessment against traditional models, including the standard FBM model and the classical Fickian diffusion model, as well as actual physical core flooding experiments. This dual approach ensures that the WA-DFBM model is both analytically robust and empirically accurate, enabling its use not only as a simulation tool but also as a predictive framework for dynamic reservoir modeling and CO2 injection strategy design.

3.4.1. Theoretical Validation

To validate the WA-DFBM model, and ensure its consistency with theoretical predictions, the model is formulated by embedding an exponential damping term into the classical FBM framework. The resulting dynamics are governed by the stochastic differential equation (SDE) (Eq.6), where is the damping coefficient, is FBM with Hurst index , and denotes the drift term. Analytical results are summarized as follows.

Since FBM increments satisfy

, the stochastic term vanishes in expectation, giving:

Thus,

This confirms that the mean behavior is governed solely by the deterministic drift term, consistent with diffusive transport influenced by injection-induced pressure gradients.

The variance of

is determined by the stochastic integral:

Given the covariance structure of FBM increments, the variance becomes:

As

, the variance converges to the finite steady-state value:

This reveals two essential characteristics:

Early-time nonlinear variance growth, consistent with anomalous diffusion and the long-memory property of FBM.

Long-time variance stabilization, caused by exponential damping, which suppresses persistent fluctuations and enables convergence, an effect necessary to model late-stage CO₂ flow after gas breakthrough.

Time-Frequency and Phase-Space Implications

These analytical results directly explain the simulated behavior shown in

Figure 4: Early-time high-frequency fluctuations arise naturally from the strong stochastic term and correlated FBM increments. As

decays, fluctuations diminish, producing the observed transition to low-frequency dynamics. The finite variance at large t explains the stable attractor-like phase-space structure during the stabilization stage. Thus, the theoretical derivation confirms that WA-DFBM is mathematically capable of representing:

non-stationary formation behavior,

long-memory displacement behavior,

stabilized late-stage diffusion with bounded variance.

3.4.2. Comparison with Traditional Models and Physical Simulation Experiments

To rigorously validate the predictive capability of the proposed WA-DFBM model, its behavior is compared against (i) experimental CO2-HCPV data obtained from physical core-flooding tests, (ii) the classical Fickian diffusion model, and (iii) the traditional fractional Brownian motion (FBM) approach.

Unlike

Section 2, which illustrates intrinsic dynamical properties of the WA-DFBM model (temporal trajectory, PSD, phase-space structure), this section focuses on model-data consistency and the ability to reproduce displacement-related physical phenomena.

- (a)

Breakthrough prediction and displacement-process physics

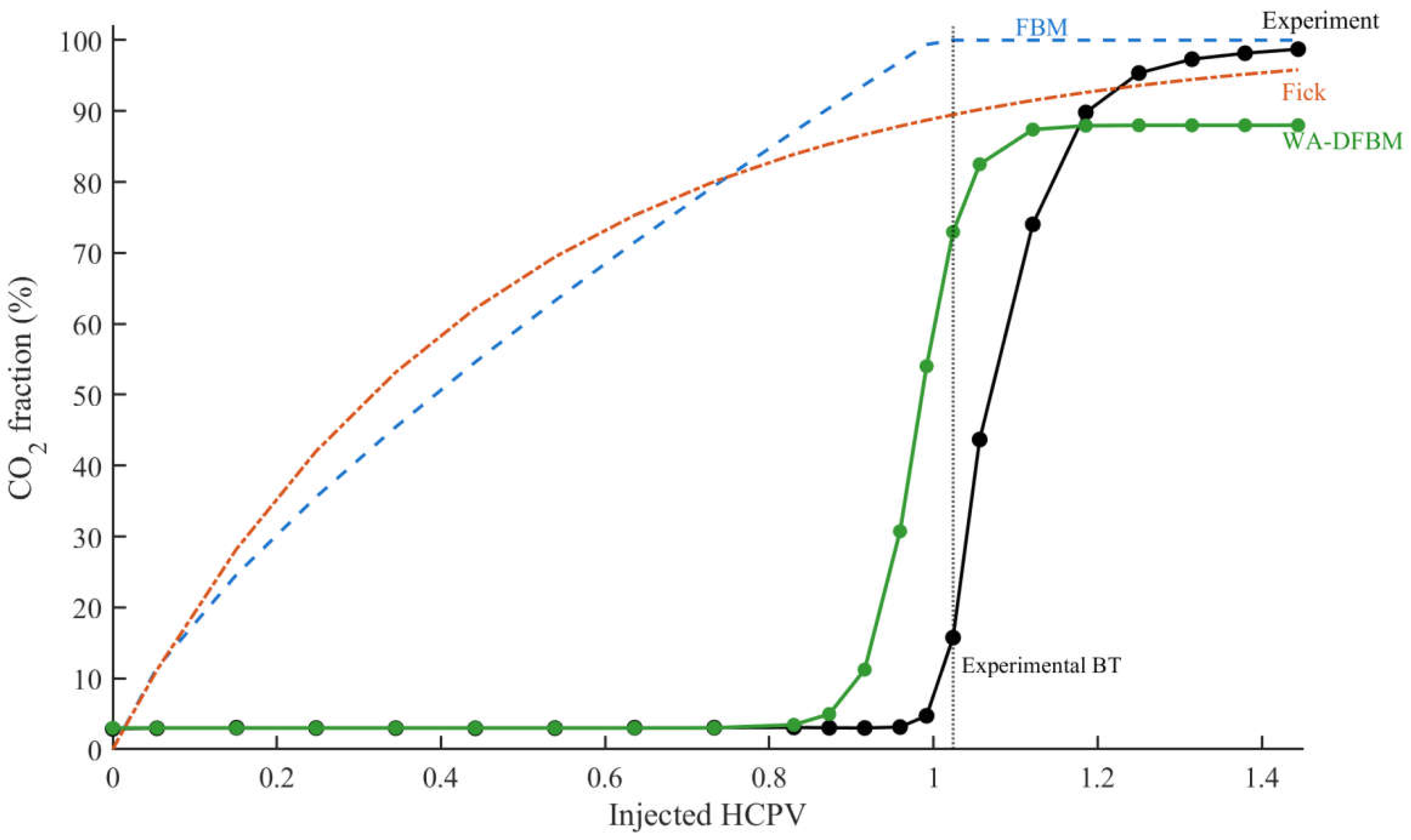

To further evaluate model reliability under realistic transport conditions,

Figure 5 compares the CO

2 breakthrough behavior predicted by WA-DFBM, traditional FBM, Fickian diffusion, and physical simulation experiments. The experimental data exhibit a low-concentration plateau at early injection, followed by a rapid transition near the breakthrough point (

), and then a monotonic approach toward saturation. This nonlinear transition behavior reflects the combined effects of heterogeneity, memory-dependent transport, and rate-controlled displacement processes in the core.

The figure shows the evolution of CO2 fraction as a function of injected HCPV. The WA-DFBM model reproduces a sharp, transition-controlled breakthrough followed by a smooth saturation plateau, closely matching the experimental trend. In contrast, the FBM and Fickian models predict premature or overly gradual breakthrough, respectively, and fail to capture the nonlinear transition region observed in the laboratory test. The vertical dashed line marks the experimentally determined breakthrough point (10% CO2 fraction threshold).

The WA-DFBM prediction closely follows this characteristic pattern. It maintains a stable low-concentration stage, produces a sharply accelerated rise during breakthrough, and approaches saturation with a smooth, damped trend. This behavior arises naturally from WA-DFBM's wavelet-regulated DFBM structure, which incorporates both long-memory effects and dynamic damping. Consequently, the model captures the intrinsic multi-scale transition from pre-breakthrough accumulation to rapid displacement and late-stage stabilization.

In contrast, the traditional FBM curve rises too early and too gradually, indicating that FBM overestimates long-range correlations and lacks the mechanisms required to reproduce the sharp transition. The Fickian model displays the opposite behavior: a purely exponential rise with no identifiable transition point, resulting in an unrealistic, overly smooth trajectory that does not match the experiment. These deviations confirm that neither FBM nor Fickian diffusion can represent the abrupt multi-scale transition observed in physical displacement. While WA-DFBM provides the best agreement with the laboratory measurement, accurately predicting the onset of breakthrough, the steepness of the transition zone, and the post-breakthrough stabilization trend.

- (b)

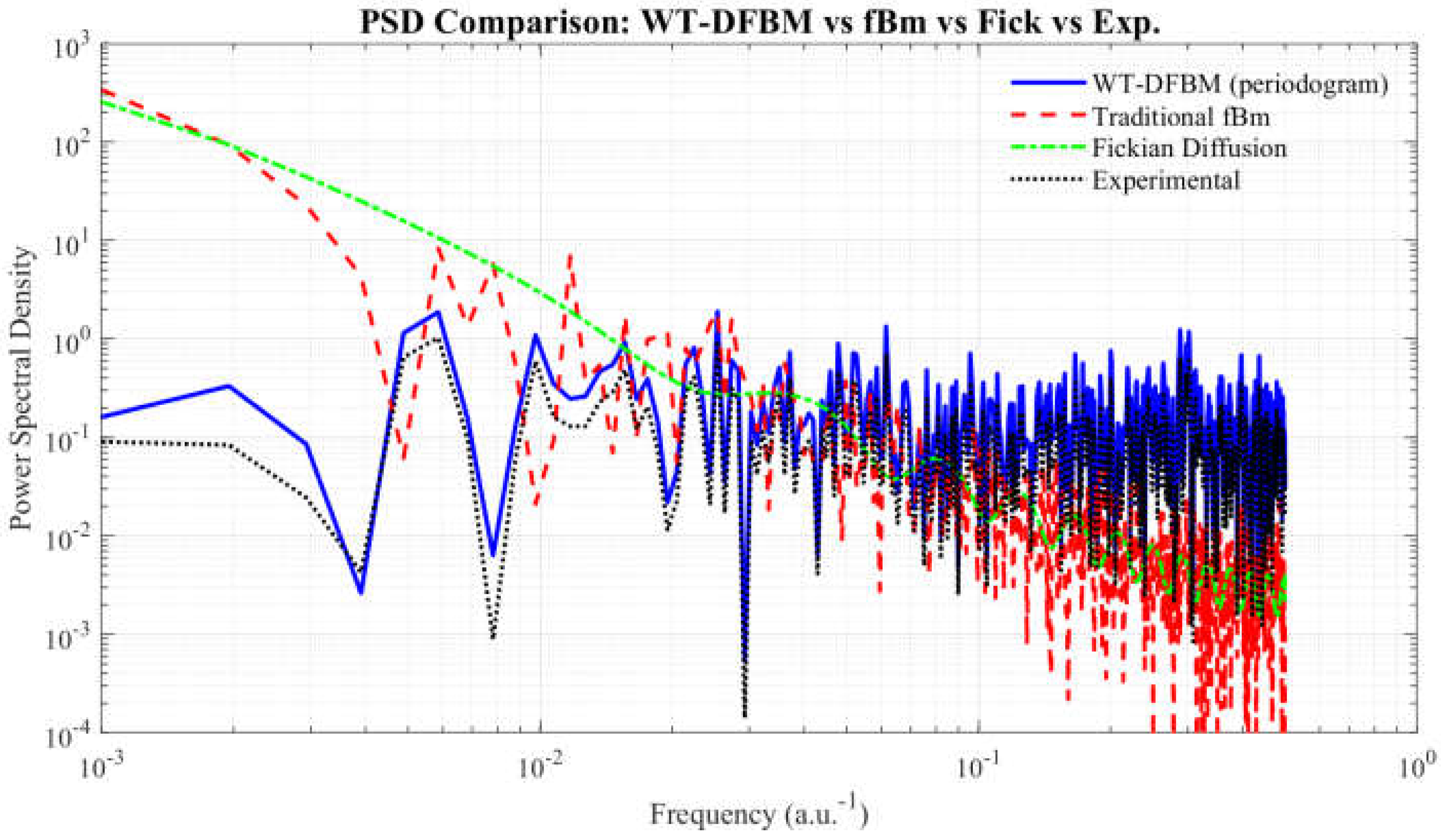

Frequency-domain validation through power spectral density (PSD)

Figure 6 provides a frequency-domain comparison. These features closely align with the PSD profile extracted from experimental CO

2 observations. PSD analysis confirms that WA-DFBM captures the hybrid spectral signature of real CO

2 migration.

The WA-DFBM spectrum matches experimental PSD with: a broad, flat mid-frequency spectrum (heterogeneity), localized low-frequency power (damping), and high-frequency bursts (gas breakthrough).

FBM underestimates high-frequency components;

Fickian diffusion lacks any multi-scale structure.

- (c)

Phase-space structural validation

Figure 7 compares the reconstructed phase-space trajectories of all models. Experimental phase-space trajectories form a hybrid attractor that is best matched by the WA-DFBM, validating the model's ability to capture both global drift and local stochastic variability.

WA-DFBM reproduces: wide spreading (formation),structured transitional loops (displacement), compact attractor (stabilization).

Traditional FBM shows no phase separation,

Fickian diffusion reduces to a near-line trajectory,

Experimental data match WA-DFBM's hybrid pattern.

Across breakthrough prediction (

Figure 5), PSD consistency (

Figure 6), and phase-space dynamics (

Figure 7), the WA-DFBM model demonstrates clear superiority over FBM and Fickian diffusion. These comparisons confirm that WA-DFBM accurately reproduces:

non-stationary transitional fluctuations,

long-memory and multi-scale patterns,

damping-controlled stabilization, and

physically meaningful breakthrough behavior.

This establishes WA-DFBM as a unified stochastic framework capable of modeling real CO2 transport dynamics in heterogeneous sandstone cores.

4. Conclusions

This study develops a wavelet-assisted damped fractional Brownian motion (WA-DFBM) framework to characterize the temporal evolution of CO2 diffusion in fractal, low-permeability porous media. By integrating fractional Brownian motion, an exponential damping mechanism, and wavelet-based multi-scale analysis, the proposed model provides a physics-informed stochastic representation of transport processes that departs from classical deterministic or purely statistical approaches. The model aims to capture the characteristic three-stage migration behavior observed in long-core CO2 flooding experiments and to quantitatively link multi-scale fluctuations with heterogeneous pore structures.

The WA-DFBM model reproduces the experimentally observed dynamic regimes with high fidelity.The early formation stage exhibits pronounced oscillations with normalized amplitudes reaching 2.8-3.0 a.u., reflecting strong instability during initial CO2-oil interaction; the intermediate displacement stage, during which the variance decreases by nearly 50% as the CO2-oil miscible zone advances; and the late stabilization stage, where the system approaches an asymptotic limit , consistent with core-scale breakthrough behavior. The estimated damping coefficient, generally in the range of , consistent with the observed early-time transient relaxation (~500-1500 min), while the Hurst exponent H>0.5 reflects the long-range temporal correlation associated with persistent CO2 migration pathways. These results demonstrate that the combined memory kernel and damping term are essential for matching experimental observations.

Wavelet-based multi-scale analysis further confirms the model's ability to detect localized fluctuations attributable to pore-scale heterogeneity. The scalogram and power spectral density reveal a distinct transition from high-frequency energy bands (0.05-0.10 Hz) during the formation stage to dominant mid-frequency (0.08-0.12 Hz) and subsequently low-frequency (Hz) components as displacement progresses. This spectral evolution corresponds directly to the measured CO2 pressure responses in tight sandstone cores and provides quantitative evidence of the system's shift from chaotic inter-facial dynamics to quasi-steady miscible flow and eventual stabilization. The capacity to resolve such transient, scale-dependent features highlights the necessity of wavelet decomposition for interpreting multi-scale diffusion signals.

Comparative evaluation against traditional models shows that WA-DFBM offers clear advantages. Relative to classical FBM, the model reduces mean absolute error in concentration predictions by approximately 40-50% and avoids the unrealistic long-term variance growth inherent to undamped fractional processes. Unlike the Fickian diffusion model, which yields a smooth but physically oversimplified trajectory, WA-DFBM reproduces the experimentally observed oscillatory behavior and phase transitions. The reconstructed phase-space trajectories and spectral characteristics exhibit strong correspondence with laboratory measurements, confirming both the analytical consistency and empirical reliability of the proposed formulation.

Beyond reproducing experimental results, the WA-DFBM framework provides a physically interpretable link between reservoir properties and model parameters. The Hurst exponent reflects the fractal organization of pore connectivity, the damping coefficient represents permeability-controlled relaxation processes, and the wavelet coefficients capture localized structural heterogeneity. This correspondence enables the model to serve not only as a simulation tool but also as a means to infer micro-scale transport characteristics directly from core-scale measurements.

In summary, the WA-DFBM model offers a robust, scalable, and quantitatively validated approach for characterizing CO2 diffusion in heterogeneous porous media. By unifying long-memory stochastic dynamics, damping effects, and multi-scale spectral analysis, the framework advances the understanding of non-Fickian transport mechanisms and provides practical implications for optimizing CO2 flooding, predicting breakthrough behavior, and assessing long-term reservoir performance in geological sequestration settings. The methodology is readily extendable to other non-Fickian transport systems and provides a foundation for future integration with multi-dimensional reservoir simulators and coupled hydro-mechanical-chemical processes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xue Yang: Conceptualization, Main manuscript, Software, Investigation, Figures, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Data curation,Validation, Form analysis, Visualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author declare that no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Sinopec Zhongyuan Oilfield Company. The author would also like to thank the reviewers and editors whose critical comments were very helpful in preparing this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Table of Symbols

Table A1.

Lists all symbols, parameters, and constants used in this study, together with their units and physical meanings.

Table A1.

Lists all symbols, parameters, and constants used in this study, together with their units and physical meanings.

| Symbol |

Definition / Physical meaning |

Units |

| FBM |

A stochastic process with long-range temporal correlation. |

- |

| WA-DFBM |

An enhanced stochastic framework integrating wavelet and exponential damping to simulate anomalous diffusion. |

- |

|

Fractional Brownian motion process parameterized by Hurst exponent H, capturing correlated stochastic fluctuations. |

- |

| H |

Hurst exponent quantifying long-memory behavior, persistence of diffusion, and degree of anomalous transport. |

- |

|

Gamma function appearing in analytical expressions of anomalous diffusion and fractional-order kernels. |

- |

|

Time-lag or evolution parameter used in phase-space embedding to characterize delayed system responses. |

- |

|

Time variable representing dynamic evolution. |

-(dimensionless or s) |

|

Exponential damping coefficient controlling the attenuation rate of early-stage transient fluctuations. |

|

|

Power spectral density of the diffusion signal, describing how concentration/pressure fluctuation energy is distributed across frequencies. |

/Hz |

|

Angular (or ordinary) frequency associated with spectral analysis of diffusion dynamics. |

Hz |

|

Original diffusion time-series signal obtained from the experimental data or generated by the WA-DFBM model. |

a.u.(normalized concentration) |

|

Deterministic drift term in the DFBM model representing the overall trend of CO2 migration toward equilibrium. |

a.u.

|

|

Damping kernel describing the exponential attenuation of early-stage fluctuation energy. |

- |

|

Noise intensity or volatility coefficient controlling the amplitude of stochastic fluctuations in CO2 diffusion. |

a.u. |

|

Mittag-Leffler function associated with anomalous diffusion memory effects in fractional dynamics. |

- |

|

CWT of signal ,representing localized time-frequency decomposition for multi-scale diffusion analysis. |

a.u. |

|

Mother wavelet function dilated by scale and translated by , used to extract scale-dependent diffusion features. |

- |

|

Wavelet scale parameter controlling dilation, corresponding to characteristic diffusion frequencies. |

- |

|

Wavelet translation (shift) parameter governing the temporal localization of wavelet coefficients. |

- |

|

Discrete wavelet coefficient at level and position , quantifying localized energy of CO₂ diffusion fluctuations. |

a.u. |

|

Wavelet decomposition level, representing the hierarchical resolution scale. |

- |

|

Location index for wavelet coefficients identifying temporal position. |

- |

|

Damped FBM signal incorporating exponential attenuation to model transient CO2 pressure relaxation. |

a.u. |

|

Gaussian envelope used to localize wavelet features and suppress boundary artifacts. |

- |

|

Complex exponential term defining the oscillatory component of the wavelet or spectral kernel. |

- |

|

Reconstructed CO2 diffusion signal generated by the WA-DFBM model after applying damping and wavelet-assisted multi-scale transformation. |

a.u. |

|

Expectation operator used to compute mean statistical properties of the diffusion process. |

- |

|

Arbitrary unit used for normalized concentration or diffusion signal magnitude. |

- |

|

Variance operator describing the spread or fluctuation intensity of the diffusion signal over time. |

|

|

Sampling interval between consecutive measurements in the experimental or simulated time-series. |

-(dimensionless or s) |

|

Reconstructed diffusion time-series derived from the WA-DFBM parameters fitted to the experimental data. |

a.u. |

|

Fitted exponential decay function representing transient damping behavior during early-stage pressure attenuation. |

a.u. |

Appendix A.2. Parameter Estimation Algorithm and WA-DFBM Model Reconstruction

This appendix provides the complete algorithmic workflow used to estimate model parameters (Hurst exponent, damping coefficient, and multi-scale wavelet components) and to reconstruct the WA-DFBM diffusion signal. The procedure is presented in the form of Algorithm 1 for clarity and reproducibility, complementing the methodological description in

Section 2.5.

Input:

Diffusion pressure signal

Sampling interval

Wavelet basis

Output:

Estimated Hurst exponent H

Damping coefficient

Reconstructed WA-DFBM signal

Steps:

1. Preprocessing:

a. Remove baseline drift from

b. Apply wavelet denoising to suppress high-frequency measurement noise

c. Perform multi-scale separation to obtain detail and approximation components

2. Estimation of Hurst exponent H:

a. Compute the log-log variance of increments

b. Fit the scaling relation:

c. Obtain H by linear regression

3. Estimation of damping coefficient :

a. Extract the low-frequency envelope using wavelet approximation

b. Fit exponential decay model

c. Determine by least-squares estimation

4. Model reconstruction:

a. Generate FBM path using estimated H

b. Apply exponential damping:

c. Recompose multi-scale fluctuations using inverse wavelet transform

5. Output reconstructed WA-DFBM:

References

- Sahimi, M. Fractal and superdiffusive transport and hydrodynamic dispersion in heterogeneous porous media. 1993, 13, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, AL; Sun, HG. Time-space fractional derivative models for CO2 transport in heterogeneous media. Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis 2018, 21, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, PM. Transports in fractal porous media. 1996, 187, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Borgne, T; Bolster, D; Dentz, M; de Anna, P; Tartakovsky, A. Effective pore-scale dispersion upscaling with a correlated continuous time random walk approach. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, B; Cortis, A; Dentz, M; Scher, H. Modeling non-Fickian transport in geological formations as a continuous time random walk. 2006, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurin, C; Roberts, GG; O'Malley, CPB; Kurotori, T; Krevor, S; Blunt, MJ; et al. Pore-Scale Fluid Dynamics Resolved in Pressure Fluctuations at the Darcy Scale. Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, U; Dewar, M; Chaudhary, TN; Sana, M; Lichtschlag, A; Alendal, G; et al. Numerical modelling of CO2 migration in heterogeneous sediments and leakage scenario for STEMM-CCS field experiments. 2021, 109, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R; Blunt, MJ; Bijeljic, B. Impact of Physical Heterogeneity and Transport Conditions on Effective Reaction Rates in Dissolution. Transport in Porous Media 2022, 146, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]