Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. General Framework of the Method

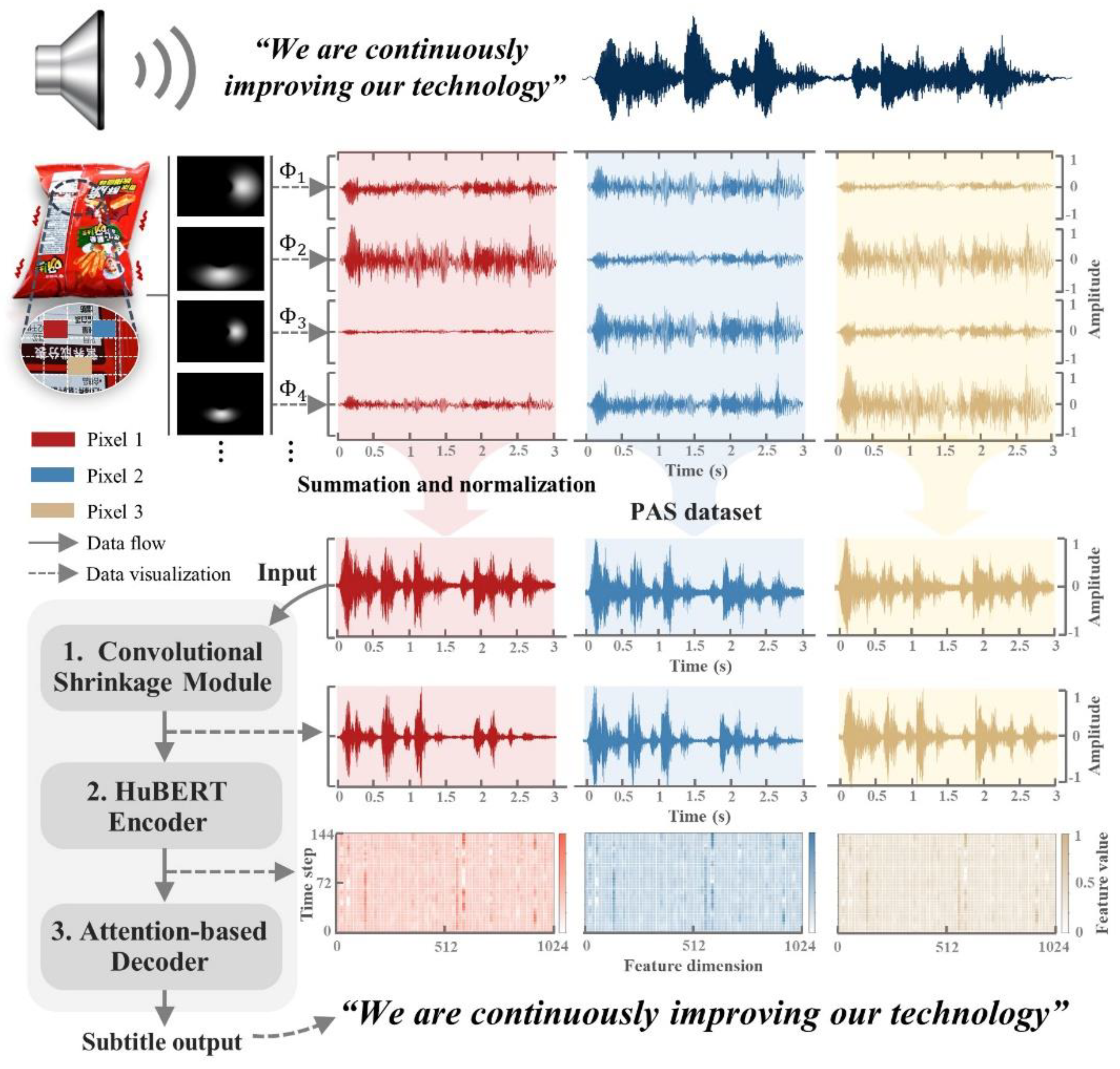

- Video capture: The response of any object to sound is purely physical. As the acoustic excitations vary, the resulting object surface vibrations are captured by a camera, effectively transforming physical displacements into pixel-level signals within the video frames;

- PAS acquisition: PASs are obtained via phase-based processing of the pixel signals;

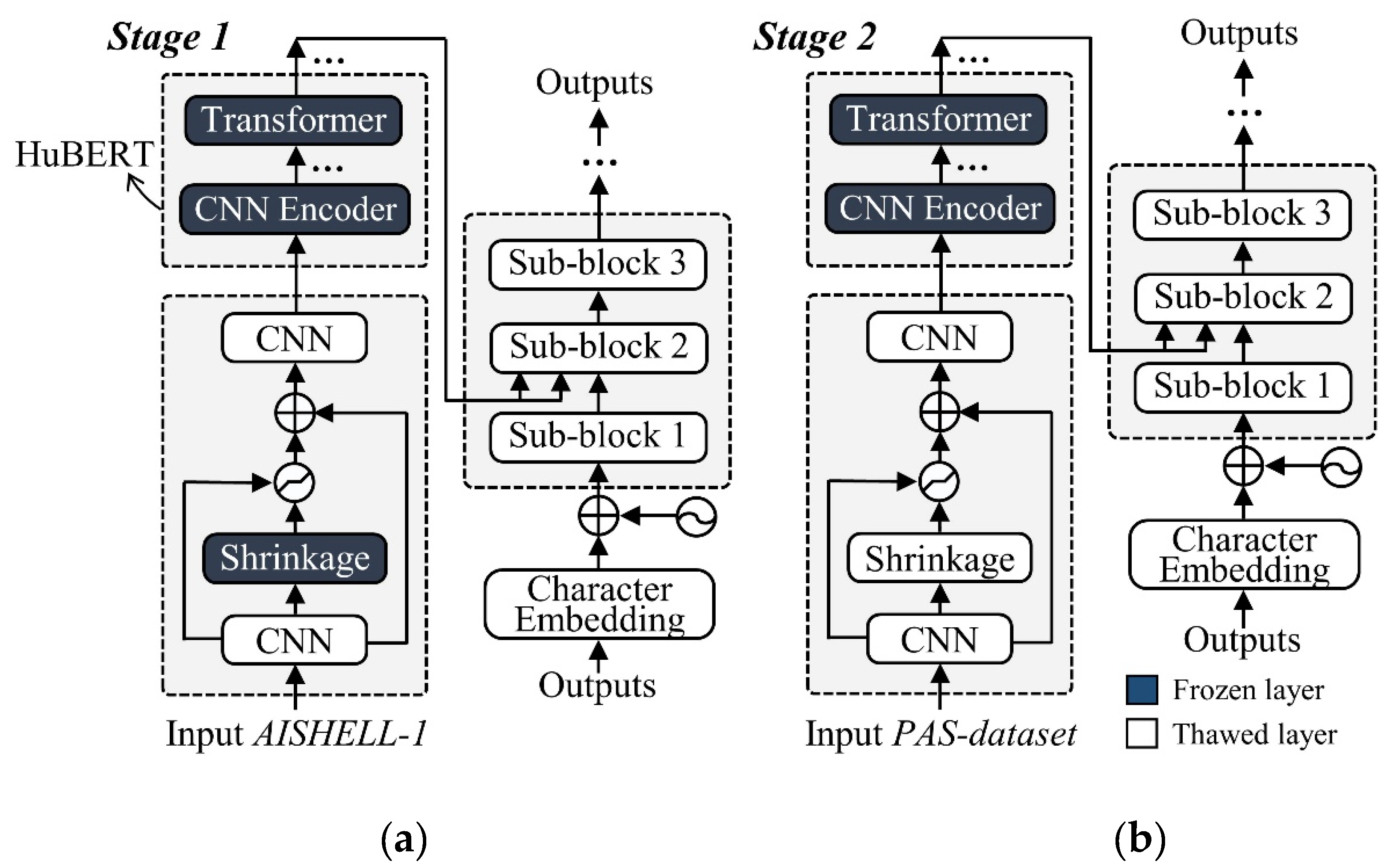

- VSG-Transformer training and testing: Large-scale PASs that encode rich acoustic features are used to construct the PAS dataset employed to train and evaluate VSG-Transformer. A multi-stage transfer learning strategy effectively links the pretrained acoustic representations of HuBERT to the PAS-driven VSG task;

- Text reconstruction: The trained VSG-Transformer reconstructs text based the PASs extracted from new videos.

2.2. Extraction of PAS

2.3. Proposed Model: The VSG-Transformer

3. Experimental Validation

3.1. Dataset Generation

3.2. Training and Testing

3.3. Results and Ablation Studies

4. VSG Operation with Low-Frame-Rate Videos

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, A.; Rubinstein, M.; Wadhwa, N.; Mysore, G.; Durand, F.; Freeman, W. The visual microphone: Passive recovery of sound from video. ACM Trans. Graph. 2014, 33, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nassi, B.; Pirutin, Y.; Swissa, R.; Shamir, A.; Elovici, Y.; Zadov, B. Lamphone: Real-time passive sound recovery from light bulb vibrations. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2020, 2020, 4401–4417. https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/708.

- Rothberg, S.; Baker, J.; Halliwell, N. Laser vibrometry: Pseudo-vibrations. J. Sound Vib. 1989, 135, 516–522. [CrossRef]

- Nassi, B.; Swissa, R.; Shams, J.; Zadov, B.; Elovici, Y. The little seal bug: Optical sound recovery from lightweight reflective objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops. 2023, 298–310. [CrossRef]

- Nassi, B.; Pirutin, Y.; Galor, T.; Elovici, Y.; Zadov, B. Glowworm attack: Optical tempest sound recovery via a device’s power indicator led. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2021, 1900–1914. [CrossRef]

- Kwong, A.; Xu, W.; Fu, K. Hard drive of hearing: Disks that eavesdrop with a synthesized microphone. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. 2019, 905–919. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Guo, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, C. Efficient subtle motion detection from high-speed video for sound recovery and vibration analysis using singular value decomposition-based approach. Opt. Eng. 2017, 56, 094105. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Guo, J.; Lei, X.; Zhu, C. Note: Sound recovery from video using svd-based information extraction. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 086111. [CrossRef]

- Guri, M.; Solewicz, Y.; Daidakulov, A.; and Elovici, Y. SPEAKE(a) R: Turn speakers to microphones for fun and profit. In Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Workshop on Offensive Technologies. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Michalevsky, Y.; Boneh, D.; Nakibly, G. Gyrophone: Recognizing speech from gyroscope signals. In Proceedings of the 23rd USENIX Security Symposium. 2014, 1053–1067.

- Long, Y.; Naghavi, P.; Kojusner, B.; Butler, K.; Rampazzi, S.; Fu, K. Side eye: Characterizing the limits of pov acoustic eavesdropping from smartphone cameras with rolling shutters and movable lenses. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. 2023, 1857–1874. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pathak, P.; Wu, M.; Zhao, Y.; and Mohapatra, P. AccelWord: Energy efficient hotword detection through accelero-meter. In Proceedings of the 13th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services. 2015, 301–315. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Chung, A.J.; Tague, P. Pitchln: Eavesdropping via intelligible speech reconstruction using non-acoustic sensor fusion. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks. 2017, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, K.; Ni, L. We can hear you with Wi-Fi! IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput. 2016, 15, 2907–2920. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. 2019, 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Bolte, B.; Tsai, Y.; Lakhotia, K.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Mohamed, A. Hubert: Self-supervised speech representation learning by masked prediction of hidden units. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 3451–3460. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell J.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Le, Q. XLNet: Generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems. 2019, 5754–5764.

- Liu, Y., Ott, M.; Goyal. N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. 2019. arXiv:1907.11692.

- Bu, H.; Du, J.; Na, X.; Wu, B.; Zheng, H. AISHELL-1: An open-source Mandarin speech corpus and a speech recognition baseline. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the Oriental Chapter of the International Coordinating Committee on Speech Databases and Speech I/O Systems and Assessment. 2017, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Fleet. D.; Jepson A. Computation of component image velocity from local phase information. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 1990, 5, 77–104. [CrossRef]

- Gautama T.; VanHulle, M. A phase-based approach to the estimation of the optical flow field using spatial filtering. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw., 2002, 13, 1127–1136. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, W.; Adelson, E. The design and use of steerable filters. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1991, 13, 891–906. [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Chang, C.; Spencer J. Out-of-plane modal property extraction based on multi-level image pyramid reconstruction using stereophotogrammetry. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108786. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, N.; Rubinstein, M.; Durand, F.; Freeman, W. Phase based video motion processing. ACM Trans. Graph. 2013, 32, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Isogawa, K.; Ida, T.; Shiodera, T.; Takeguchi, T. Deep shrinkage convolutional neural network for adaptive noise reduction. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2018, 25, 224–228. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhong, S.; Fu, X.; Tang, B.; Pecht, M. Deep residual shrinkage networks for fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2020, 16, 4681–4690. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lv, H.; Guo P.; Shao Q.; Yang C.; Xie L. Wenetspeech: A 10000 hours multi-domain mandarin corpus for speech recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing. 2022, 6182–6186. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Weld, D.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Levy, O. SpanBERT: Improving pre-training by representing and predicting spans. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 64–77. [CrossRef]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, H.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M.; wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. 2020. arXiv:2006.11477.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019.

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. 2015, arXiv:1412.6980.

- Chorowski J.; Jaitly, N. Towards better decoding and language model integration in sequence to sequence models. In Proceedings of the Interspeech. 2017, 523–527. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Schuster, M.; Chen, Z.; Le, Q.; Norouzi, M.; Macherey, W.; Krikun, M.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Macherey K.; et al. Google’s neural machine translation system: Bridging the gap between human and machine translation. 2016, arXiv:1609.08144.

- Yang, Y.; Hira, M.; Ni, Z.; Astafurov, A.; Chen, C.; Puhrsch, C. Torchaudio: Building blocks for audio and speech processing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing. 2022, 6982–6986. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lee C. DNN-based speech bandwidth expansion and its application to adding high-frequency missing features for automatic speech recognition of narrowband speech. In Proceedings of the Interspeech. 2015, 2578–2582.

- Rakotonirina, N. Self-attention for audio super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing, 2021, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Djelouah, A.; McWilliams, B.; Sorkine-Hornung, A.; Gross, M.; Schroers, C. Phasenet for video frame interpolation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2018, 498–507.

| Method | Exploited Device | Sampling Rate | Technique Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lamphone [2,4] | Photodiode | 2-4 kHz | Recovery |

| LDVs [3] | Laser transceiver | 40 kHz | |

| Glowworm [5] | Photodiode | 4-8 kHz | |

| Hard Drive of Hearing [6] | Magnetic hard drive | 17 kHz | |

| Visual Microphone [1] | High-speed camera | 2-20 kHz | |

| SVD [7,8] | High-speed camera | 2.2 kHz | |

| SPEAKE(a)R [9] | Speakers | 48 kHz | |

| Gyrophone [10] | Gyroscope | 200 Hz | Classification |

| Side Eye [11] | Smartphone cameras | 60 Hz | |

| Accelword [12] | Accelerometer | 200 Hz | |

| Pitchln [13] | Fusion of several motion sensors | 2 kHz | |

| WiHear [14] | Software-defined radio | 300 Hz | |

| VSG of the present paper | High-speed camera | 2-16 kHz | Generation |

| Base | Large | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN encoder | Strides | 5, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 | |

| Kernel Width | 10, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 2 | ||

| Channels | 512 | ||

| Transformer | Blocks | 12 | 24 |

| Embedding Dimension | 768 | 1,024 | |

| Inner FFN Dimension | 3,072 | 4,096 | |

| Attention Heads | 12 | 16 | |

| Number of Parameters | 95 M | 317 M | |

| AISHELL-1 | PAS Dataset | ||||||

| Train. | Dev. | Test | Train. | Dev. | Test | ||

| Utterances | 120098 | 14326 | 7176 | 89600 | 19200 | 19200 | |

| Hours | 150 | 18 | 10 | 107 | 28 | 29 | |

| Durations (s) | Min. | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.5 |

| Max. | 14.5 | 12.5 | 14.7 | 12.4 | 10.2 | 10.4 | |

| Avg. | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| Tokens | Min. | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 |

| Max. | 44.0 | 35.0 | 37.0 | 35.0 | 22.0 | 26.0 | |

| Avg. | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 12.3 | 11.2 | |

| Training Stage | Model Scale | Dataset | Training Epochs | Frozen Layer(s) | Development (%) | Test (%) | |

| AISHELL-1 | PAS | ||||||

| Stage 1 | Base | √ | - | 130 | Shrinkage + HuBERT | 6.2 | 6.4 |

| Large | √ | - | 130 | Shrinkage + HuBERT | 5.9 | 6.1 | |

| Stage 2 | Base | - | √ | 40 | HuBERT | 13.3 | 13.7 |

| Large | - | √ | 40 | HuBERT | 12.1 | 12.5 | |

| Configuration | AISHELL-1 | PAS Dataset | |||

| Development (%) | Test (%) | Development (%) | Test (%) | ||

| Test1 | Without stage 2 | 5.9 | 6.1 | - | 56.7 |

| Test2 | Shrinkage layer frozen during stage 2 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 18.5 | 19.1 |

| Test3 | Number of decoder blocks | Development (%) | Test (%) | Development (%) | Test (%) |

| 10 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 | |

| 8 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 12.0 | 12.2 | |

| 6 (baseline model) | 5.9 | 6.1 | 12.1 | 12.5 | |

| 4 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 13.4 | 13.6 | |

| Upsampling Methods | 2 × (original 8 kHz) | 4 × (original 4 kHz) | 8 × (original 2 kHz) | |||

| Development (%) | Test (%) | Development (%) | Test (%) | Development (%) | Test (%) | |

| BSI [35] | 22.3 | 27.1 | 34.8 | 41.5 | - | - |

| DNN [36] | 14.4 | 14.8 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 24.7 | 25.6 |

| AFiLM [37] | 14.3 | 14.8 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 22.5 | 24.2 |

| Phase-net [38] | 13.2 | 13.6 | 14.1 | 15.3 | 18.4 | 19.6 |

| - | 12.1/12.5 (original 16 kHz) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).