Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

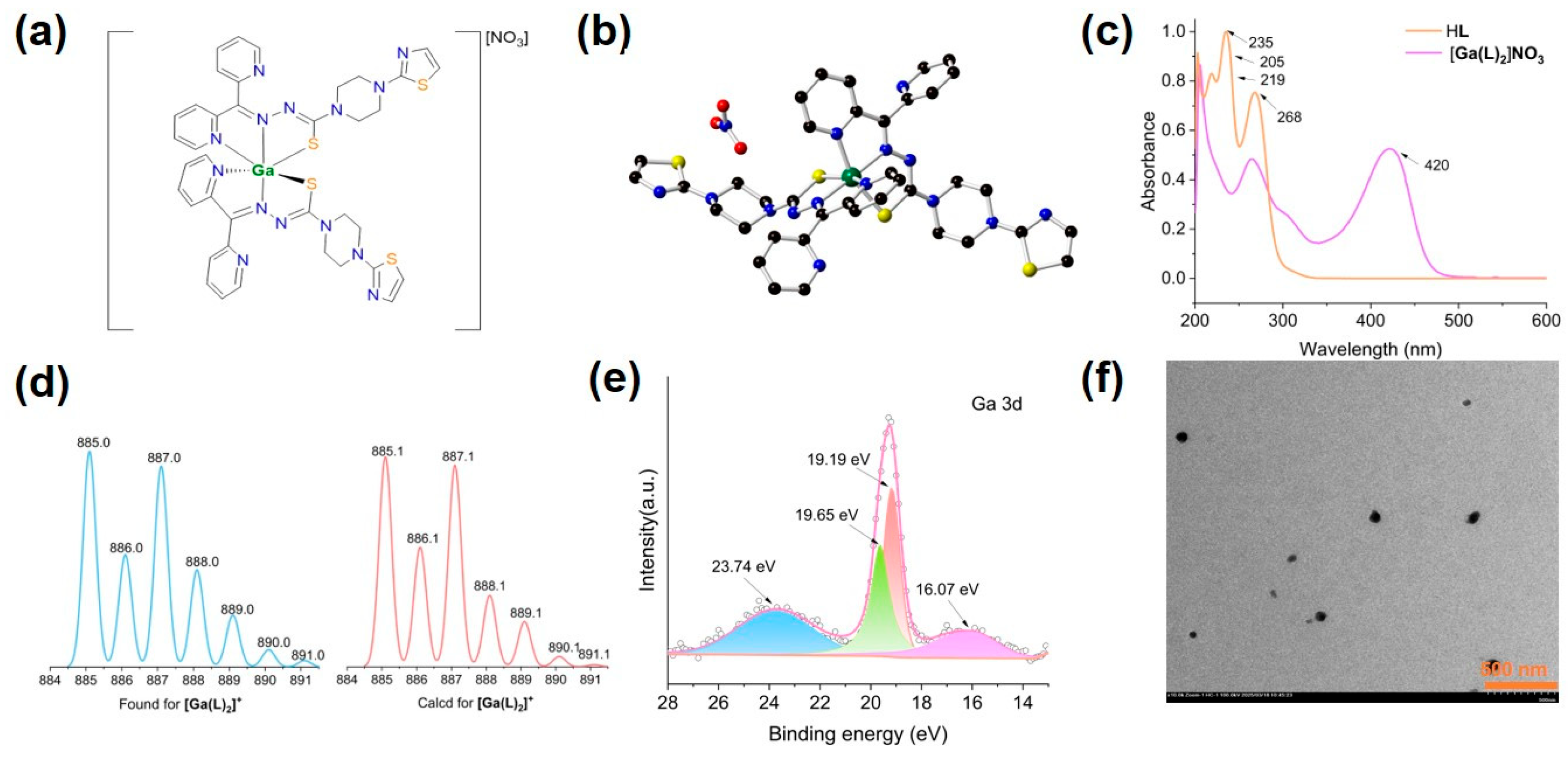

2.1. Synthesis and Structure of [Ga(L)2]NO3

2.2. Spectroscopic and Spectrometric Characterizations of [Ga(L)2]NO3

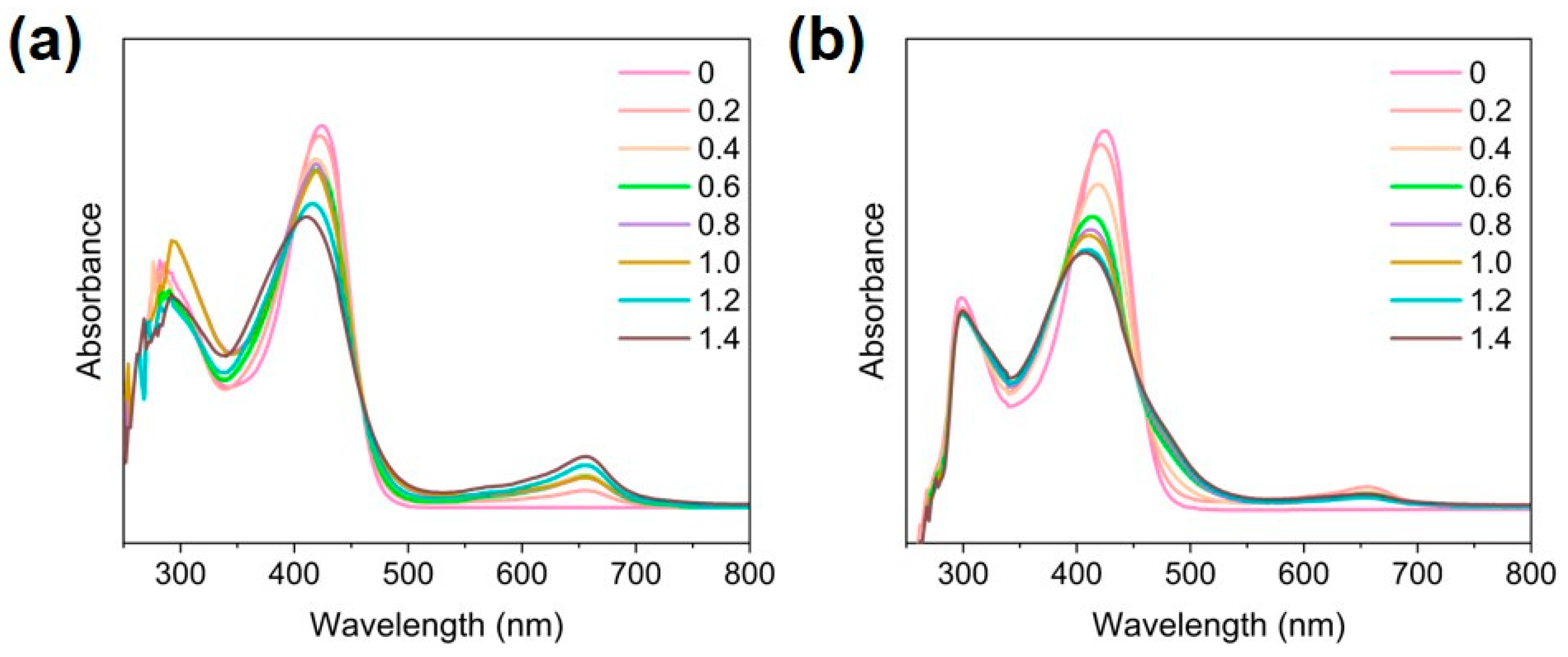

2.3. Fe2+ and Fe3+ Exchange with [Ga(L)2]NO3

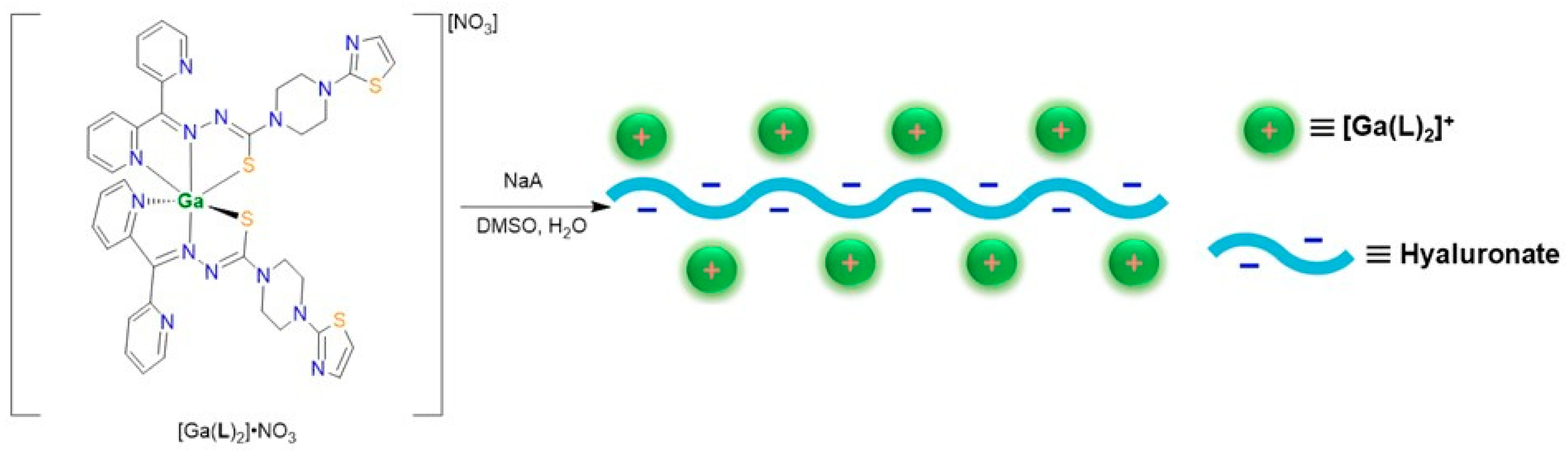

2.4. Synthesis and Characterizations of [Ga(L)2]A Nanoparticles

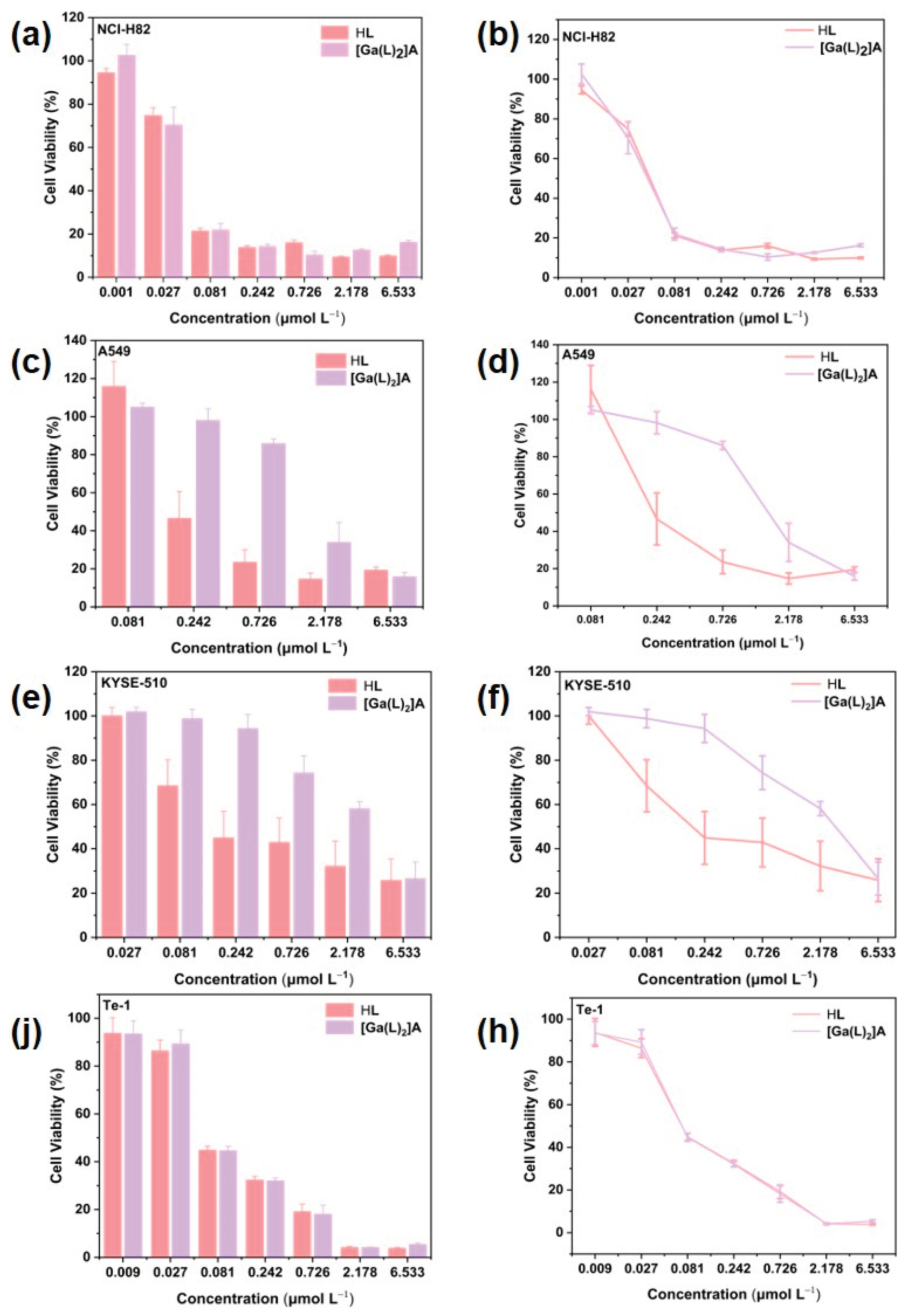

2.5. Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

2.6. Cellular Uptake of [Ga(L)2]A

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. Synthesis of [Ga(L)2]NO3

3.3. Single-Crystal X-Ray Crystallography

3.4. Fe2+-Exchange with [Ga(L)2]NO3

3.5. Fe3+-Exchange with [Ga(L)2]NO3

3.6. Titration Experiment

3.7. Nanoparticle Formations of [Ga(L)2]A

3.8. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation by CCK-8 Assay

3.9. Cellular Uptake

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalinowski, D.S.; Quach, P.; Richardson, D.R. Thiosemicarbazones: The New Wave in Cancer Treatment. Futur. Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 1143–1151. [CrossRef]

- Serda, M.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Rasko, N.; Potůčková, E.; Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz, A.; Musiol, R.; Małecki, J.G.; Sajewicz, M.; Ratuszna, A.; Muchowicz, A.; et al. Exploring the Anti-Cancer Activity of Novel Thiosemicarbazones Generated through the Combination of Retro-Fragments: Dissection of Critical Structure-Activity Relationships. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e110291–e110291. [CrossRef]

- Dilworth, J.R.; Hueting, R. Metal complexes of thiosemicarbazones for imaging and therapy. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2012, 389, 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Shakya, B.; Yadav, N.P. Thiosemicarbazones as potent anticancer agents and their modes of action. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 638−661.

- Rudnev, A.V.; Foteeva, L.S.; Kowol, C.; Berger, R.; Jakupec, M.A.; Arion, V.B.; Timerbaev, A.R.; Keppler, B.K. Preclinical characterization of anticancer gallium(III) complexes: Solubility, stability, lipophilicity and binding to serum proteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 1819–1826. [CrossRef]

- Kowol, C.R.; Berger, R.; Eichinger, R.; Roller, A.; Jakupec, M.A.; Schmidt, P.P.; Arion, V.B.; Keppler, B.K. Gallium(III) and Iron(III) Complexes of α-N-Heterocyclic Thiosemicarbazones: Synthesis, Characterization, Cytotoxicity, and Interaction with Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 1254–1265. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Lovejoy, D.B.; Richardson, D.R. Novel di-2-pyridyl–derived iron chelators with marked and selective antitumor activity: in vitro and in vivo assessment. Blood 2004, 104, 1450–1458. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.R.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Richardson, V.; Sharpe, P.C.; Lovejoy, D.B.; Islam, M.; Bernhardt, P.V. 2-Acetylpyridine Thiosemicarbazones are Potent Iron Chelators and Antiproliferative Agents: Redox Activity, Iron Complexation and Characterization of their Antitumor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 1459–1470. [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, D.B.; Sharp, D.M.; Seebacher, N.; Obeidy, P.; Prichard, T.; Stefani, C.; Basha, M.T.; Sharpe, P.C.; Jansson, P.J.; Kalinowski, D.S.; et al. Novel Second-Generation Di-2-Pyridylketone Thiosemicarbazones Show Synergism with Standard Chemotherapeutics and Demonstrate Potent Activity against Lung Cancer Xenografts after Oral and Intravenous Administration in Vivo. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7230–7244. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Goh, B.C.; Tan, E.H.; Lam, K.C.; Soo, R.; Leong, S.S.; Wang, L.Z.; Mo, F.; Chan, A.T.C.; Zee, B.; et al. A multicenter phase II trial of 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (3-AP, Triapine®) and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with pharmacokinetic evaluation using peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Investig. New Drugs 2007, 26, 169–173. [CrossRef]

- DeConti, R.C.; Toftness, B.R.; Agrawal, K.C.; Tomchick, R.; A Mead, J.; Bertino, J.R.; Sartorelli, A.C.; A Creasey, W. Clinical and pharmacological studies with 5-hydroxy-2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazone.. 1972, 32, 1455–62.

- Westin, S.N.; Nieves-Neira, W.; Lynam, C.; Salim, K.Y.; Silva, A.D.; Ho, R.T.; Mills, G.B.; Coleman, R.L.; Janku, F.; Matei, D. Abstract CT033: Safety and early efficacy signals for COTI-2, an orally available small molecule targeting p53, in a phase I trial of recurrent gynecologic cancer. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, CT033–CT033. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.H.B.; Hager, S.; Mathuber, M.; Pósa, V.; Roller, A.; Enyedy, É.A.; Stefanelli, A.; Berger, W.; Keppler, B.K.; Heffeter, P.; et al. Cancer Cell Resistance Against the Clinically Investigated Thiosemicarbazone COTI-2 Is Based on Formation of Intracellular Copper Complex Glutathione Adducts and ABCC1-Mediated Efflux. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13719–13732. [CrossRef]

- Lessa, J.A.; Parrilha, G.L.; Beraldo, H. Gallium complexes as new promising metallodrug candidates. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2012, 393, 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.R. Mechanisms of therapeutic activity for gallium. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998, 50, 665–682.

- Zhang, X.; Yang, X.-R.; Huang, X.-W.; Wang, W.-M.; Shi, R.-Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, S.-J.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J. Sorafenib in treatment of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2012, 11, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Collery, P.; Keppler, B.; Madoulet, C.; Desoize, B. Gallium in cancer treatment. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2002, 42, 283–296. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yao, K.; Zhou, M. Visualized Gallium/Lyticase-Integrated Antifungal Strategy for Fungal Keratitis Treatment. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34. [CrossRef]

- Hofheinz, R.-D.; Dittrich, C.; Jakupec, M.; Drescher, A.; Jaehde, U.; Gneist, M.; Keyserlingk, N.G.V.; Keppler, B.; Hochhaus, A. Early results from a phase I study on orally administered tris(8-quinolinolato)gallium(III) (FFC11, KP46) in patients with solid tumors ? a CESAR study (Central European Society for Anticancer Drug Research ? EW. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 43, 590–591. [CrossRef]

- Wilke, N.L.; Abodo, L.O.; Frias, C.; Frias, J.; Baas, J.; Jakupec, M.A.; Keppler, B.K.; Prokop, A. The gallium complex KP46 sensitizes resistant leukemia cells and overcomes Bcl-2-induced multidrug resistance in lymphoma cells via upregulation of Harakiri and downregulation of XIAP in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113974. [CrossRef]

- Hreusova, M.; Novohradsky, V.; Markova, L.; Kostrhunova, H.; Potočňák, I.; Brabec, V.; Kasparkova, J. Gallium(III) Complex with Cloxyquin Ligands Induces Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells and Is a Potent Agent against Both Differentiated and Tumorigenic Cancer Stem Rhabdomyosarcoma Cells. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 2022, 3095749. [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.-Y.; Zeng, C.-M.; Xu, P.; Ning, Y.; Dong, M.-L.; Zhang, W.-H.; Yu, G. Thiazole Functionalization of Thiosemicarbazone for Cu(II) Complexation: Moving toward Highly Efficient Anticancer Drugs with Promising Oral Bioavailability. Molecules 2024, 29, 3832. [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.-L.; Zhang, Z.-S.; Dong, M.-L.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, W.-H.; Mao, Y.; Young, D.J. A high-entropy coordination cage featuring an Au-porphyrin metalloligand for the photodynamic therapy of liver cancer. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 6663–6666. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, R.; Ye, Q.; Zou, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y. Mn3O4 nanoshell coated metal–organic frameworks with microenvironment-driven O2 production and GSH exhaustion ability for enhanced chemodynamic and photodynamic cancer therapies. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2202280.

- Hou, Y.-K.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Li, R.-T.; Peng, J.; Chen, S.-Y.; Yue, Y.-R.; Zhang, W.-H.; Sun, B.; Chen, J.-X.; Zhou, Q. Remodeling the Tumor Microenvironment with Core–Shell Nanosensitizer Featuring Dual-Modal Imaging and Multimodal Therapy for Breast Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 2602–2616. [CrossRef]

- Stefani, C.; Punnia-Moorthy, G.; Lovejoy, D.B.; Jansson, P.J.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Sharpe, P.C.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Richardson, D.R. Halogenated 2′-Benzoylpyridine Thiosemicarbazone (XBpT) Chelators with Potent and Selective Anti-Neoplastic Activity: Relationship to Intracellular Redox Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6936–6948. [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, D.S.; Yu; Sharpe, P.C.; Islam, M.; Liao, Y.-T.; Lovejoy, D.B.; Kumar, N.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Richardson, D.R. Design, synthesis, and characterization of novel iron chelators: Structure−activity relationships of the 2-benzoylpyridine thiosemicarbazone series and their 3-nitrobenzoyl analogues as potent antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 3716−3729.

- Milunovic, M.N.M.; Ohui, K.; Besleaga, I.; Petrasheuskaya, T.V.; Dömötör, O.; Enyedy, É.A.; Darvasiova, D.; Rapta, P.; Barbieriková, Z.; Vegh, D.; et al. Copper(II) Complexes with Isomeric Morpholine-Substituted 2-Formylpyridine Thiosemicarbazone Hybrids as Potential Anticancer Drugs Inhibiting Both Ribonucleotide Reductase and Tubulin Polymerization: The Morpholine Position Matters. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 9069–9090. [CrossRef]

- Man, X.; Li, S.; Xu, G.; Li, W.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, H.; Yang, F. Developing a Copper(II) Isopropyl 2-Pyridyl Ketone Thiosemicarbazone Compound Based on the IB Subdomain of Human Serum Albumin–Indomethacin Complex: Inhibiting Tumor Growth by Remodeling the Tumor Microenvironment. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 5744–5757. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Huang, K.; Pan, W.; Wu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Ma, L.; Gou, Y. Thiosemicarbazone Mixed-Valence Cu(I/II) Complex against Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells through Multiple Pathways Involving Cuproptosis. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 9091–9103. [CrossRef]

- Stacy, A.E.; Palanimuthu, D.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Jansson, P.J.; Richardson, D.R. Zinc(II)–Thiosemicarbazone Complexes Are Localized to the Lysosomal Compartment Where They Transmetallate with Copper Ions to Induce Cytotoxicity. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4965–4984. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, Q.; Wang, F.-A.; Fan, W.; Gao, H.; Xia, X. Single-crystal structure and intracellular localization of Zn(II)-thiosemicarbazone complex targeting mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127340. [CrossRef]

- Carcelli, M.; Tegoni, M.; Bartoli, J.; Marzano, C.; Pelosi, G.; Salvalaio, M.; Rogolino, D.; Gandin, V. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of tridentate thiosemicarbazone copper complexes: Unravelling an unexplored pharmacological target. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 194, 112266. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Azad, M.G.; Suleymanoglu, M.; Harmer, J.R.; Wijesinghe, T.P.; Richardson, V.; Zhao, X.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Dharmasivam, M.; Richardson, D.R. Isosteric Replacement of Sulfur to Selenium in a Thiosemicarbazone: Promotion of Zn(II) Complex Dissociation and Transmetalation to Augment Anticancer Efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 12155–12183. [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Ibrahim, A.B.; Elkhalik, S.A.; Villinger, A.; Abbas, S. New iron(III) complexes with 2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazones: Synthetic aspects, structural and spectral analyses and cytotoxicity screening against MCF-7 human cancer cells. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13008. [CrossRef]

- Wiles, D.M.; Suprunchuk, T. The C==S stretching vibration in the infrared spectra of some thiosemicarbazones. II. Aldehyde thiosemicarbazones containing aromatic groups. Can. J. Chem. 1967, 45, 2258–2263. [CrossRef]

- West, D.X.; Billeh, I.S.; Jasinski, J.P.; Jasinski, J.M.; Butcher, R.J. Complexes of N(4)-cyclohexylsemicarbazones and N(4)-cyclohexylthiosemicarbazones derived from 2-formyl-, 2-acetyl- and 2-benzoylpyridine. Transit. Met. Chem. 1998, 23, 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, A.G.; M. Pérez, J.; López-Solera, I.; Montero, E.I.; Masaguer, J.R.; Alonso, C.; Navarro-Ranninger, C. Binuclear chloro-bridged palladated and platinated complexes derived from p-isopropylbenzaldehyde thiosemicarbazone with cytotoxicity against cisplatin resistant tumor cell lines. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998, 69, 275−281.

- John, R.P.; Sreekanth, A.; Rajakannan, V.; Ajith, T.; Kurup, M.P. New copper(II) complexes of 2-hydroxyacetophenone N(4)-substituted thiosemicarbazones and polypyridyl co-ligands: structural, electrochemical and antimicrobial studies. Polyhedron 2004, 23, 2549–2559. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-Y.; Qin, L.; Fan, C.; Cai, S.-L.; Zhang, T.-T.; Chen, W.-H.; Tang, X.-Y.; Chen, J.-X. Sequential and recyclable sensing of Fe3+ and ascorbic acid in water with a terbium(iii)-based metal–organic framework. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 8911–8919. [CrossRef]

- Bourque, J.L.; Biesinger, M.C.; Baines, K.M. Chemical state determination of molecular gallium compounds using XPS. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 7678–7696. [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, R.; Liu, T.; Liang, J.; An, Y.; et al. Remote plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of gallium oxide thin films with NH3 plasma pretreatment. J. Semicond. 2019, 40. [CrossRef]

- Zatsepin, D.; Boukhvalov, D.; Zatsepin, A. Quality assessment of GaN epitaxial films: Acidification scenarios based on XPS-and-DFT combined study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 563. [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.H.; Paniago, E.; Beraldo, H. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of iron(II) and iron(III) complexes of some α(N)-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones. Reduction of the iron(III) complexes of 2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazone and 2-acetylpyridine thiosemicarbazone by cellular thiol-like reducing agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1997, 65, 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, R.; Muñiz, P.; Cavia, M.; Palacios, Ó.; Samper, K.G.; Gil-García, R.; Jiménez-Pérez, A.; García-Tojal, J.; García-Girón, C. Thiosemicarbazone-metal complexes exhibiting cytotoxicity in colon cancer cell lines through oxidative stress. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 206, 110993. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Feng, X.-D.; Yang, B.; Tong, R.-L.; Lu, Y.-J.; Chen, D.-Y.; Zhou, L.; Xie, H.-Y.; Zheng, S.-S.; Wu, J. Dimethyl fumarate suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression via activating SOCS3/JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. 2019, 11, 4713–4725.

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Su, R.; Jia, Y.; Lai, X.; Su, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xing, W.; Qin, J. Dimethyl Fumarate Combined With Vemurafenib Enhances Anti-Melanoma Efficacy via Inhibiting the Hippo/YAP, NRF2-ARE, and AKT/mTOR/ERK Pathways in A375 Melanoma Cells. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 794216. [CrossRef]

- Basilotta, R.; Lanza, M.; Filippone, A.; Casili, G.; Mannino, D.; De Gaetano, F.; Chisari, G.; Colarossi, L.; Motta, G.; Campolo, M.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Dimethyl Fumarate in Counteract Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression by Modulating Apoptosis, Oxidative Stress and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2777. [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Tang, X.-Y.; Meng, W.; Lai, Y.-H.; Zhou, X.; Yu, X.-Z.; Zhang, W.-H.; Chen, J.-X. Immunogenic Radiation Therapy for Enhanced Antitumor Immunity via a Core–Shell Nanosensitizer-Mediated Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment Modulation. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 19853–19864. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, K.; Kaplan, M.; Çalış, S. Effects of nanoparticle size, shape, and zeta potential on drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 666, 124799. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Nakamura, H.; Fang, J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: Improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Xu, D.; Liang, S.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H. Prolonging the plasma circulation of proteins by nano-encapsulation with phosphorylcholine-based polymer. Nano Res. 2016, 9, 2424–2432. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, I.C.; Soares, M.A.; dos Santos, R.G.; Pinheiro, C.; Beraldo, H. Gallium(III) complexes of 2-pyridineformamide thiosemicarbazones: Cytotoxic activity against malignant glioblastoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 1870–1877. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Schniper, S.; González-Sarrías, A.; Holder, A.A.; Sanders, N.; Sullivan, D.; Jarrett, W.L.; Davis, K.; Bai, F.; Seeram, N.P.; et al. Highly potent anti-proliferative effects of a gallium(III) complex with 7-chloroquinoline thiosemicarbazone as a ligand: Synthesis, cytotoxic and antimalarial evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 86, 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Liang, H.; Yang, F. Developing a Gallium(III) Agent Based on the Properties of the Tumor Microenvironment and Lactoferrin: Achieving Two-Agent Co-delivery and Multi-targeted Combination Therapy of Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 66, 793–803. [CrossRef]

- Dharmasivam, M.; Kaya, B.; Wijesinghe, T.; Azad, M.G.; Gonzálvez, M.A.; Hussaini, M.; Chekmarev, J.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Richardson, D.R. Designing Tailored Thiosemicarbazones with Bespoke Properties: The Styrene Moiety Imparts Potent Activity, Inhibits Heme Center Oxidation, and Results in a Novel “Stealth Zinc(II) Complex”. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 1426–1453. [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, P.V.; Sharpe, P.C.; Islam, M.; Lovejoy, D.B.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Richardson, D.R. Iron Chelators of the Dipyridylketone Thiosemicarbazone Class: Precomplexation and Transmetalation Effects on Anticancer Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 52, 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Qian, Y.; Hu, S.; Tian, Y. Synthesis, anticancer activity and mechanism of action of Fe(III) complexes. Drug Dev. Res. 2024, 85, e22264. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS (Version 2.03): Program for empirical absorption correction of area detector data; University of Göttingen, Germany. 1996.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C 2015, 71, 3−8.

| [Ga(L)2]NO3 | |

| Formula | C39H40GaN15O4S4 |

| Formula Weight | 980.82 |

| Crystal System | monoclinic |

| Space Group | P21/n |

| a/Å | 13.7231(4) |

| b/Å | 16.5511(5) |

| c/Å | 19.3202(7) |

| β/° | 93.1060(10) |

| V/Å3 | 4381.8(2) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcalc /(g cm–3) | 1.487 |

| F(000) | 2024 |

| μ (Mo–Kα)/mm–1 | 0.879 |

| Total Reflections | 102760 |

| Unique Reflections | 10031 |

| No. Observations | 8243 |

| Rint | 0.0528 |

| No. Parameters | 570 |

| Ra | 0.0374 |

| wRb | 0.0912 |

| GOFc | 1.111 |

| Ga1−S1 | 2.3600(6) | Ga1−S3 | 2.3715(6) |

| Ga1−N12 | 2.0493(17) | Ga1−N5 | 2.0529(16) |

| Ga1−N7 | 2.0938(18) | Ga1−N13 | 2.1249(18) |

| N12−Ga1−N5 | 175.06(7) | N12−Ga1−N7 | 97.70(7) |

| N5−Ga1−N7 | 78.03(7) | N12−Ga1−N13 | 77.30(7) |

| N5−Ga1−N13 | 99.88(7) | N7−Ga1−N13 | 87.69(7) |

| N12−Ga1−S1 | 101.96(5) | N5−Ga1−S1 | 82.07(5) |

| N7−Ga1−S1 | 159.62(5) | N13−Ga1−S1 | 91.44(5) |

| N12−Ga1−S3 | 82.12(5) | N5−Ga1−S3 | 100.30(5) |

| N7−Ga1−S3 | 90.52(5) | N13−Ga1−S3 | 158.91(5) |

| S1−Ga1−S3 | 97.36(2) |

| Entry | Compound | Cell Line | IC50 (µM) | Reference |

| 1 | [Ga(La)2]NO3 | RT2 | 810 | [53] |

| 2 | [Ga(Lb)₂(NO₃)]·xH₂O | HCT-116 | 0.55 | [54] |

| 3 | [Ga(Lc)₂]PF₆ | SK-BR-3 | 1.7×10-4 | [6] |

| 4 | Ga(Ld)Cl₂ | MCF-7 | 1.05 | [55] |

| 5 | [Fe(Le)₂](ClO₄) | SK-N-MC | 0.19 | [56] |

| 6 | Fe(Lf)2(NO3)(H2O)3 | SW-480 | 19.11 | [45] |

| 7 | [Fe(Lg)₂](ClO₄) | HL60 | 0.4 | [57] |

| 8 | [Fe(Lh)₂]Cl | MDA-MB-231 | 12.38 | [58] |

| 9 | [Cu(NO3)(L)]2 | Hep-G2 | 16.86 | [22] |

| 11 | [Ga(L)2]A | NCI-H82 | 0.102 | This work |

| 12 | [Ga(L)2]A | A549 | 1.342 | This work |

| 13 | [Ga(L)2]A | KYSE-510 | 2.616 | This work |

| 14 | [Ga(L)2]A | Te-1 | 0.267 | This work |

| [Ga(L)2]A | [Ga(L)2]A' | |

| 2 h | 310.325 | 224.521 |

| 4 h | 503.897 | 309.679 |

| 6 h | 554.22 | 323.187 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).