1. Introduction

Peptides are short chains of up to 40 to 50 amino acids. Peptides occupy a distinct biochemical and regulatory niche between small-molecule drugs (generally <500 Daltons) and large biological proteins (>5000 Daltons), functioning as potent signaling molecules for numerous physiological processes [

1,

2]. Peptides have a central role in treating numerous diseases and injuries, including the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) tirzepatide and semaglutide, which have revolutionized weight loss and diabetes care [

2]. Parathyroid hormone analogs abaloparatide and teriparatide are peptides that are critical in treating osteoporosis and accelerating fracture repair [

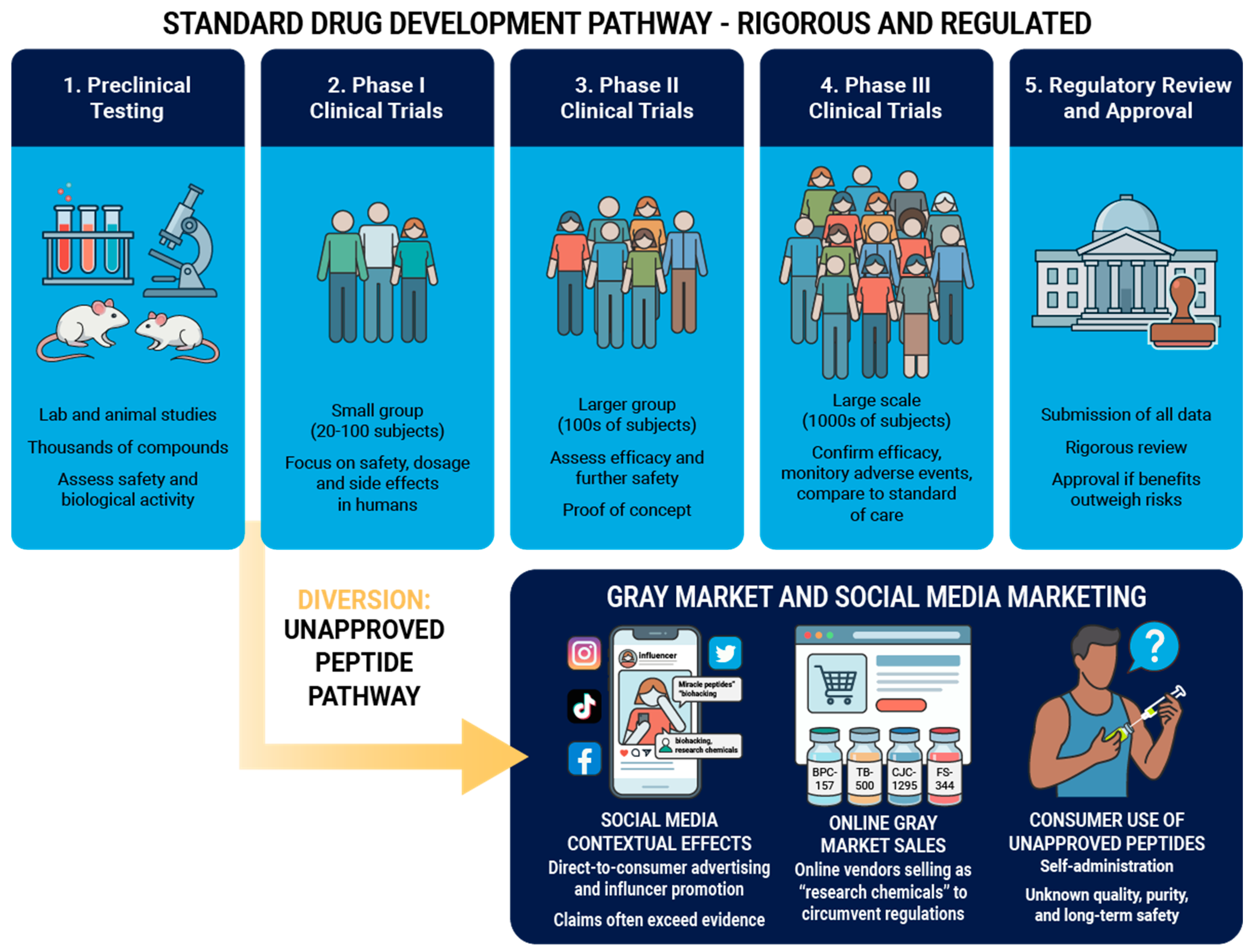

3]. Approved peptide drugs undergo a rigorous path of development and approval, with extensive clinical trials often consisting of thousands of subjects to establish efficacy and safety [

1,

2]. Peptide use is growing, as global sales of approved peptide drugs will likely reach

$75 billion USD by 2028 [

1]. However, a parallel and pervasive "gray market" has emerged, driven by direct-to-consumer sales of unapproved peptides [

4]. These compounds, frequently carrying disclaimers like "research chemical" or "not for human consumption" to circumvent regulatory oversight, are aggressively marketed to athletes and the general public [

5]. The purported benefits of these substances include accelerated musculoskeletal injury recovery, muscle hypertrophy, athletic performance enhancement, and many others [

5]. The gray market operates largely outside of current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) guidelines, creating significant patient risks [

5].

Non-approved peptides present a distinct challenge for the sports medicine community. On one hand, preclinical data for many peptides shows compelling improvements in musculoskeletal tissue repair. On the other hand, translating these findings to human clinical practice remains largely theoretical, with a profound paucity of human safety data. This review will discuss production methods for peptides, provide an extensive analysis of the most commonly used peptides with sports medicine indications, describe the placebo and contextual effects of peptides, and will equip providers with the requisite knowledge to facilitate evidence-based discussions with patients.

2. Peptide Synthesis, Manufacturing, and Compounding

To appreciate the risks of gray market peptides, it is important to understand basics of peptide synthesis. Such understanding is critical to explaining why a "99% pure" label on a gray market vial may still conceal dangerous impurities.

2.1. Peptide Synthesis and Manufacturing

Peptides are synthesized through one of three methodologies: solid-phase peptide synthesis, liquid-phase peptide synthesis, or a hybrid approach [

2,

6]. Each technique has its strengths and limitations. The disparity between approved pharmaceutical peptides and gray market "research chemicals" is most pronounced in purification and validation steps. Approved peptides undergo stringent purification and validation, while gray market peptides may be produced without these steps [

2,

6,

7]. Substitutions or deletions in amino acid residues can result in a peptide with vastly different biological properties, behaving in an unpredictable or dangerous manner [

8]. Additionally, some of the hazardous chemicals used in peptide production like trifluoroacetic acid are removed during cGMP peptide production, but may not be in the production of gray market peptides [

9,

10].

Approved peptides are manufactured in cGMP facilities overseen by regulatory agencies that ensure strict control over materials, environmental conditions, and sterility [

2,

7] Conversely, with gray market peptides there is no oversight regarding endotoxin levels which can cause fever or shock, sterility, or cross-contamination with other substances produced in the same equipment [

7,

11]. With no regulatory oversight, many peptides produced and sold by gray market producers contain impurities not found in approved peptides [

12].

2.2. Compounding of Approved Peptides

While some approved peptides are produced in large batches by manufacturers under cGMP conditions, smaller batches of approved peptides can be produced via compounding. Peptide compounding in the US is regulated under Section 503A and 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [

13]. Traditional 503A compounding pharmacies compound peptides for individual patients based on a valid prescription and are exempt from cGMP regulations, but must comply with United States Pharmacopeia (USP) standards [

14]. Bulk drug substances that have a USP monograph, are components of FDA-approved drugs, or are on approved FDA lists can be legally compounded. Outsourcing facilities (503B) can compound on larger scales without patient-specific prescriptions but must adhere to cGMP standards [

14]. The FDA has restricted the compounding of certain peptides, placing them on a "Category 2" list, which effectively bans their compounding. This list includes peptides such as BPC-157, CJC-1295, Ipamorelin, and TB-500, among others. In Europe, pharmaceutical compounding is largely regulated nationally, allowing pharmacists to compound medicines for patients with special needs when a commercial alternative is not available [

15]. Australia regulates compounding under the auspices of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) [

16], which generally allows the compounding of peptides entered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) [

16].

3. Peptides with Potential Use in Sports Medicine

Peptides with potential impact on muscle size, strength or athletic performance are rising in popularity. There has been a noticeable increase in direct-to-consumer marketing for unapproved peptides [

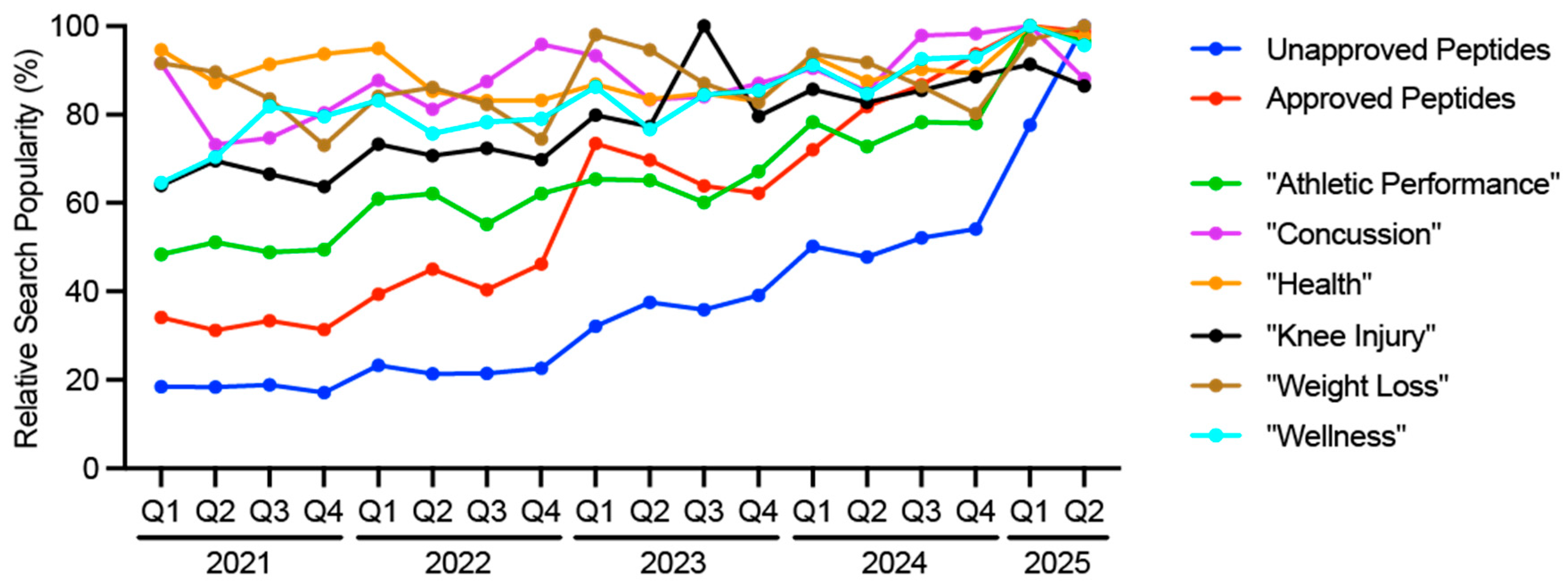

5]. Consumers are seeking more information on peptides, as evidenced by changes in relative search term popularity. Searches on Google for unapproved peptides such as "AOD-9604", "BPC-157", "CJC-1295", "Follistatin", "GHK-Cu", "Ipamorelin", "MOTS-C", or "TB-500" have considerably increased starting in 2024 (

Figure 1). This was preceded by searches for approved peptides such as "Tirzepatide" and "Semaglutide" (

Figure 1). Other search terms relevant to sports medicine, such as "Concussion", "Health", "Knee injury", "Weight Loss" and "Wellness" have remained consistent, while there has been an uptick in "Athletic Performance" (

Figure 1). Many popular peptides relevant to sports medicine are discussed in the following sections, and also summarized in Supplemental

Table S1. We will not discuss the GLP-1RAs or PTH analogs, as these have been covered extensively elsewhere [

2,

3]. Peptides discussed below are on the 2025 World Anti-Doping Agency Prohibited List, with the exception of GHK-Cu and SS-31.

3.1. AOD-9604

AOD-9604 (Anti-Obesity Drug 9604) is a peptide fragment of residues 177-191 of human growth hormone (hGH), with a tyrosine residue added to enhance stability [

17]. AOD-9604 was originally developed to isolate the lipolytic properties of hGH while avoiding anabolic and insulin-desensitizing effects [

17,

18]. AOD-9604 is proposed to stimulate lipolysis through interaction with beta adrenergic receptors [

17,

18,

19]. AOD-9604 does not bind the hGH receptor with high affinity and does not stimulate insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) production, and aims to reduce adiposity without the other effects of chronic hGH administration [

17,

18,

19]. AOD-9604 significantly reduced fat mass in rodent models of obesity [

19], which then led to six randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials involving over 900 patients to evaluate the treatment of obesity [

18]. The safety profile was favorable, with no changes in IGF-1 or insulin sensitivity [

18]. However, AOD-9604 failed to show dose dependent, statistically significant weight loss compared to placebo, leading to the termination of clinical development for obesity [

20].

AOD-9604 is often promoted off-label for fat reduction, although it is ineffective for this purpose. Recently, there has been interest in AOD-9604 for cartilage repair based on promising results in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis [

21], but there is no human data available. While clinical trials demonstrated AOD-9604 was safe in the short term, prolonged activation of beta adrenergic signaling could lead to dysautonomias [

22]. Alternatives to AOD-9604 for weight loss include the GLP-1RAs, or the norepinephrine and dopamine releasing agent phentermine [

23,

24,

25]. The hGH secretagogues sermorelin and tesamorelin, discussed in subsequent sections, may also be appropriate alternatives. Physiotherapy, hyaluronic acid, platelet rich plasma (PRP), bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC), or adipose stromovascular fraction (SVF) therapies [

26] are likely better at treating osteoarthritis symptoms.

3.2. BPC-157

Body Protection Compound-157 (BPC-157) is a 15 amino acid peptide derived from a protein found in human gastric secretions [

27]. BPC-157 is thought to act through multiple biochemical pathways to promote tissue repair, but activating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) signaling appears to be its main mode of action [

4,

27]. Preclinical data demonstrating BPC-157 is effective in healing musculoskeletal injuries [

4], but human data is virtually non-existent. A small, retrospective observational study suggested intra-articular injections of BPC-157 reduced knee pain [

28], but the study was fraught with several flaws, and claims around knee pain reductions were not substantiated. BPC-157 is widely used for the treatment of musculoskeletal injuries, including tendinopathy, muscle strains, and ligament sprains, but clinical validation remains absent.

A major concern about the safety of BPC-157 stems from its role in stimulating angiogenesis via VEGF. High VEGF abundance in tumor tissue or blood is consistently associated with worse outcomes in cancer treatment [

29]. Additionally, while vascularization may improve healing in some tissues, neovascularization is correlated with worse functional outcomes in chronic tendinopathy [

30,

31]. There are numerous alternatives to BPC-157. These include PRP, BMAC, SVF or extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) for promoting connective tissue healing, platelet poor plasma (PPP) to enhance muscle recovery, and physiotherapy [

26,

32,

33,

34]. Emerging data also indicates limited courses of low dose testosterone or hGH may safely restore musculoskeletal function and accelerate injury recovery [

35,

36].

3.3. CJC-1295

CJC-1295 is a synthetic analogue of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) and has a significantly extended half-life compared to endogenous GHRH [

37]. CJC-1295 is a GHRH agonist, binding to GHRH receptors in the pituitary gland to stimulate hGH secretion and IGF-1 production. CJC-1259 causes a sustained, rather than pulsatile, elevation of hGH, with a 2-10 fold increase in hGH for 6 days or more post-injection [

37]. There are significant safety concerns with CJC-1295. In a dose escalation trial, adverse events occurred in 94% of patients receiving CJC-1295, while only 29% of subjects receiving placebo group reported similar events [

37]. A phase II trial of CJC-1295 to treat HIV-associated lipodystrophy was halted after the death of a patient, although the causality regarding CJC-1295 was debated [

38].

Athletes use CJC-1295 to attempt to enhance muscle mass, reduce fat, and improve tissue healing. CJC-1295 is sometimes combined with ipamorelin to try to maximize hGH pulse amplitude while attempting to mitigate continuous GHRH stimulation issues. The continuous elevation of hGH can cause pituitary desensitization and blunting of the natural hGH axis [

39]. Persistent activation of the hGH-IGF-1 axis can cause insulin resistance, water retention, and organomegaly [

40]. Safer and likely more effective treatment options to CJC-1295 include GLP-1RAs or phentermine for lipolysis, or PRP, BMAC, SVF of physiotherapy for connective tissue healing [

23,

26,

41]. Sermorelin and tesamorelin could also be appropriate alternatives for some patients.

3.5. FS-344

Follistatin is a naturally occurring autocrine glycoprotein. The 344 isoform (FS-344) is an alternatively spliced peptide which potently inhibits myostatin and activin signaling [

42]. Myostatin and activin induce muscle atrophy, and by sequestering inhibitors of atrophy, FS-344 is posited to increase muscle mass and strength [

42,

43]. FS-344 has gained traction in the gray market due to its potential ability to induce muscle hypertrophy.

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) gene-mediated delivery of FS-344 has shown dramatic increases in muscle mass and strength in mouse and non-human primate models [

44,

45]. A small clinical trial in Becker Muscular Dystrophy patients showed safety and functional improvements with FS-344 AAV gene therapy [

46]. An important distinguishing factor between gene therapy and injectable FS-344 has to do with the relatively short one to two hour half-life of follistatin [

47]. The gene vector that produces FS-344 utilizes the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, which is a constitutively active promoter [

48], resulting in near constant production of FS-344 in transduced cells. Therefore, injectable FS-344 would likely only result in transient myostatin or activin inhibition, and have little to no impact on muscle size or strength. Safety studies of injectable FS-344 are limited, with most focused on the gene therapy. Alternative approaches to using FS-344 include low-dose testosterone, which is able to safely and effectively increase muscle mass in appropriate patients [

36].

3.6. GHK-Cu

GHK-Cu (Glycyl-L-Histidyl-L-Lysine copper complex) is a naturally occurring copper-binding peptide. Originally isolated from human plasma [

49], GHK-Cu promotes collagen synthesis, stimulates angiogenesis, and possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties through cytokine downregulation [

49].

Preclinical data supports the ability of GHK-Cu to heal skin wounds and stomach ulcers [

50,

51]. In humans, GHK-Cu is widely used in cosmetics to improve skin texture and composition [

49]. Injectable forms are purported to improve joint healing, although clinical data is lacking. Topical GHK-Cu has a long history of safe cosmetic use [

49], but injectable formulations pose distinct risks. Since the synovium is highly vascularized, injected copper can be absorbed systemically, causing toxic effects to multiple organ systems. In the US, Europe, and Australia, GHK-Cu is not approved as a drug for topical use but is allowed as a cosmetic product due to minimal systemic absorption. Safe and approved alternatives for treating joint pain include hyaluronic acid, PRP, BMAC, SVF, and physiotherapy [

26,

32,

33,

34].

3.7. Ipamorelin

Ipamorelin is a pentapeptide and a selective agonist of the ghrelin/growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR1) that stimulates the pituitary gland to release hGH in a pulsatile manner [

52]. Unlike other GHSR1 agonists, ipamorelin is selective for hGH release and does not significantly stimulate the release of cortisol, or prolactin [

53]. Animal studies demonstrate ipamorelin functions similar to other hGH secretagogues [

54]. Further preclinical studies demonstrate ipamorelin increases appetite through activation of the ghrelin receptor [

55]. Activation of the ghrelin receptor also appears to reduce colonic hypersensitivity, and visceral and somatic allodynia [

56]. A small phase II study of ipamorelin was conducted in patients with postoperative ileus, and found that a 7-day treatment course of the peptide was generally safe, but had no impact on clinical outcomes [

57].

Ipamorelin is favored in part for its lack of cortisol and prolactin spike, which reduces water retention [

52]. Additionally, ipamorelin has been used for individuals who are consuming high protein diets as part of intensive exercise training regimes. Protein can induce satiety, and these individuals may encounter difficulty consuming enough calories to support their functional training goals [

58]. Chronic stimulation of the ghrelin receptor can alter glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [

59]. Because the ghrelin receptor is highly expressed in somatotroph adenomas and ghrelin can stimulate proliferation of somatotroph tumor cells, there is a concern that chronic non-physiologic GHSR activation could contribute to somatotroph hyperplasia or adenoma formation [

60]. Safer and potentially more effective alternatives to ipamorelin for fat loss include GLP-1RAs or phentermine, and potentially tesamorelin or sermorelin [

23,

61,

62]. For anorexia, alternatives to ipamorelin may be the use of more calorie dense foods, or cannabinoid receptor agonists like dronabinol [

63,

64].

3.8. MOTS-C

MOTS-c (Mitochondrial ORF of the 12S rRNA type-c) is a peptide encoded by the mitochondrial genome that is thought to acts as an exercise mimetic, interacting with the folate cycle and AMPK pathways to regulate glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [

65,

66]. MOTS-c works in preclinical models by promoting fatty acid oxidation and inhibiting folate-dependent purine biosynthesis. MOTS-c prevented diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice [

65,

66]. Human data is limited to observational studies correlating endogenous levels with insulin sensitivity [

65,

66], and clinical trials have been completed.

MOTS-c has been marketed for endurance enhancement, weight loss, and metabolic improvements. There is a theoretical risk that long-term dosing of MOTS-c could disrupt cellular replication or nucleotide biosynthesis in unforeseen ways. The metabolic consequences of chronic AMPK activation in healthy humans are also not fully understood [

67]. Safe and effective alternatives to MOTS-c are GLP-1RAs or phentermine, and potentially tesamorelin or sermorelin, along with zone 2 training [

23,

61,

62].

3.9. Sermorelin and Tesamorelin

Sermorelin and tesamorelin are hGH secretagogue peptides with similar biological properties. Sermorelin is a synthetic N-terminal fragment (1-29) of GHRH and was previously FDA-approved for pediatric growth failure under the brand name Geref, but was discontinued by the manufacturer in 2008 for commercial reasons [

61]. As sermorelin was not withdrawn for safety reasons, the FDA and TGA generally allow sermorelin to be prescribed by a physician and legally compounded. Tesamorelin (Egrifta) is an FDA-approved peptide consisting of the full 44 amino acid sequence of GHRH modified with trans-3-hexenoic acid group, which increases the half-life and potency of hGH axis stimulation [

62,

68]. While not approved by the EMA or TGA, tesamorelin is FDA approved for visceral fat reduction in HIV+ patients with lipodystrophy.

Sermorelin and tesamorelin stimulate the physiological, pulsatile release of hGH [

68]. Both hormones increase IGF-1, and the potential benefits are similar for the use of recombinant hGH or IGF-1. Safety and efficacy of these peptides were established with their original approvals, and they are generally considered safer than exogenous hGH because the natural feedback loops of the pituitary gland can prevent overdose [

68]. Sermorelin and tesamorelin have potential use in recovery from physical activity or injuries through increased collagen synthesis, protection against muscle atrophy after joint injury, and reduced joint inflammation and osteoarthritis [

35,

69,

70]. hGH promotes slow-wave sleep, which is the sleep cycle phase that is crucial for physical recovery and cognitive function [

71]. hGH has been proposed to have anti-aging effects, although this is controversial [

72]. Short term use of hGH and its secretagogues offers therapeutic benefits for some conditions [

68], but organisms with sustained elevations in hGH over several years typically have shorter lifespans [

72]. Sermorelin and tesamorelin are often preferred over hGH for their safety profile and lower cost [

73]. Common side effects of these peptides include facial flushing, headache, dizziness, and injection site urticaria [

73]. In patients where sermorelin or tesamorelin may not be appropriate, other therapies for weight loss include GLP-1RAs. Additional alternatives for recovery and connective tissue healing include shock wave therapy, physiotherapy, and PRP [

26,

32,

33,

34], and meditation for promoting slow-wave sleep [

74].

3.10. SS-31

SS-31 (Elamipretide) is a tetrapeptide that binds selectively to cardiolipin, a phospholipid in the inner mitochondrial membrane, resulting in improved electron transport chain efficiency [

75]. SS-31 underwent rigorous development and was recently approved by the FDA [

76], with EMA and TGA approval pending. SS-31 reduces the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species, and has shown efficacy in heart failure, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and mitochondrial myopathies [

75]. SS-31 is generally well-tolerated with no major side effects [

75]. Additionally, preclinical studies demonstrate that SS-31 improves cognitive function in traumatic brain injuries [

77], suggesting a potential role in treating patients with concussions.

Athletes have been attracted to gray market SS-31 to improve endurance and recovery. While SS-31 has recently achieved regulatory approval for a rare genetic mitochondrial myopathy [

76], the safety profile in healthy individuals for performance enhancement or injury recovery remains unstudied. There is no long-term data on how this mechanism impacts mitophagy in healthy tissue over years of use, and traditional zone 2 training remains a safer option [

78]. For antioxidant functions, safer alternatives to SS-31 include Coenzyme Q10, and Vitamins A, C and E [

79].

3.11. TB-500

TB-500 (Thymosin Beta-4 fragment) is a 43-amino acid fragment of Thymosin Beta-4, a naturall protein that promotes cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis [

80]. Accelerated healing of connective tissue, cardiac, and dermal wounds, as well as improved muscle recovery after endurance exercise, have been reported in preclinical models of TB-500 [

80]. The purported use of TB-500 in athletes is injury recovery and metabolic substrate restoration after endurance exercise, but human data is lacking. An additional concern is that thymosin beta-4 is known to be upregulated in many metastatic cancers, facilitating the migration of tumor cells to distant sites [

81]. Consequently, TB-500 use carries a significant theoretical risk of metastasis. Until trials can establish the safety and efficacy of TB-500 for wound healing, alternative treatments include PRP or hyperbaric oxygen can be useful, while cyclic compression therapies or the PDE5-inhibitor tadalafil are safe and effective alternatives to TB-500 for post-workout recovery [

26,

82,

83].

4. The Placebo and Contextual Effects of Peptides

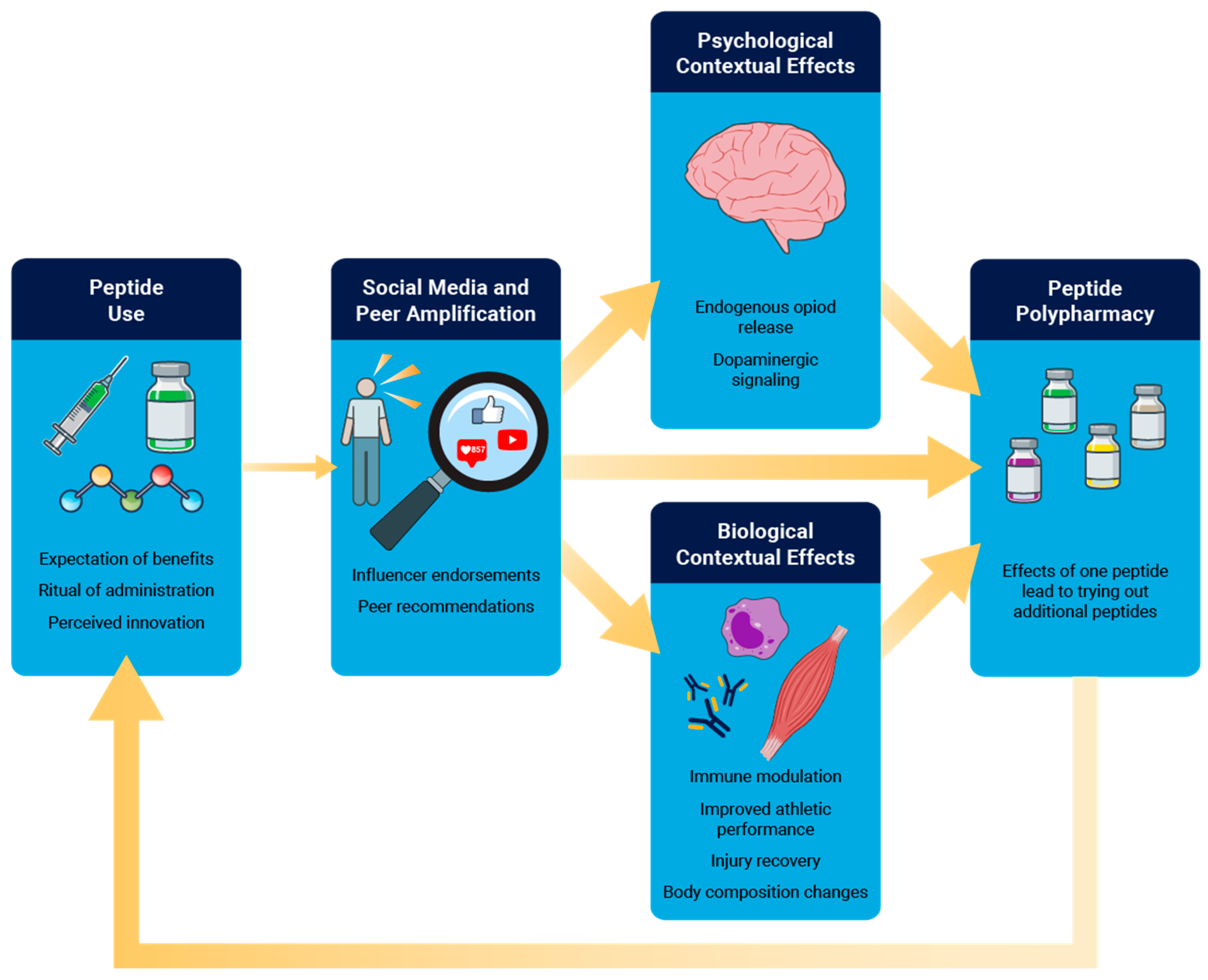

Placebos are interventions that lack specific pharmacologic activity for the condition being treated, but can have a considerable impact on physiological function [

84]. Related to this, the contextual effect of therapy is a complex psychobiological event that encompasses the placebo medication, as well as the ritual encompassing patient expectations, injections and procedures, interactions from other patients and peers, and the opinions and endorsements from trusted figures and medical professionals [

84]. Contextual effects can result in robust physiological changes, even though the compound that is being consumed has no direct pharmacologic mechanism of action [

84]. When the compound does have a pharmacological mechanism of action, contextual effects can modulate the efficacy of the therapeutic intervention [

84].

Peptides constitute near ideal factors for amplified contextual effects because they often combine high expectancy, invasive injections, endorsement from popular social media influencers, with a dense therapeutic ritual. As it relates to pain, contextual effects can engage endogenous opioid signaling within numerous brain structures and can be attenuated or abolished by naloxone, indicating a genuine modulation of descending pain control systems rather than reporting bias alone [

85]. Contextual effects can also induce dopaminergic signaling within mesolimbic reward circuits to further connect the expectation of a positive effect of a placebo to pain reduction [

85]. Dopaminergic activation can contribute to peptide polypharmacy, where the use of one peptide to treat a specific condition motivates a patient to seek additional peptides to treat other conditions. Outside of the brain, contextual effects can also impact local immune cell function and tissue repair, resulting in alterations in cytokine profiles and immune cell activation [

86].

Contextual effects appear to have small to moderate effects on musculoskeletal pain and athletic performance [

87,

88,

89,

90]. Even in open-label studies where subjects knew they were receiving a pharmacologically-inert pill, placebo treatment still improved pain and function, demonstrating the considerable power of contextual effects [

91]. The manner in which contemporary social media platforms reinforce interest [

92] likely contributes to the contextual effects of peptide therapy. An individual who is interested in athletic performance or injury recovery may receive ads for a company selling peptides, or may have videos of influencers promoting peptides appear in their suggested viewing lists. Once the individual clicks on the ad or suggested video, a positive feedback cycle is engaged [

92] which fills their social media feed with content promoting peptides. Health information delivered through social media often has an overemphasis on potential positive effects and preclinical studies without a balanced discussion of the human clinical trials or potential side effects [

93,

94]. For peptides with no effective pharmacological mechanism, contextual marketing effects may be enough for an individual to feel benefit with peptide use. Peptides with an established pharmacological mechanism could have even more of a positive effect. Potential positive effects need to be weighed against potential negative effects, such as cancer metastasis or mortality. The average time a user spends on social media continues to increase [

95], so it is likely that contextual effects around peptides will continue to grow, making informed decisions with providers about evidence-based peptide even more important (

Figure 2).

5. Discussing Peptide Therapy with Patients

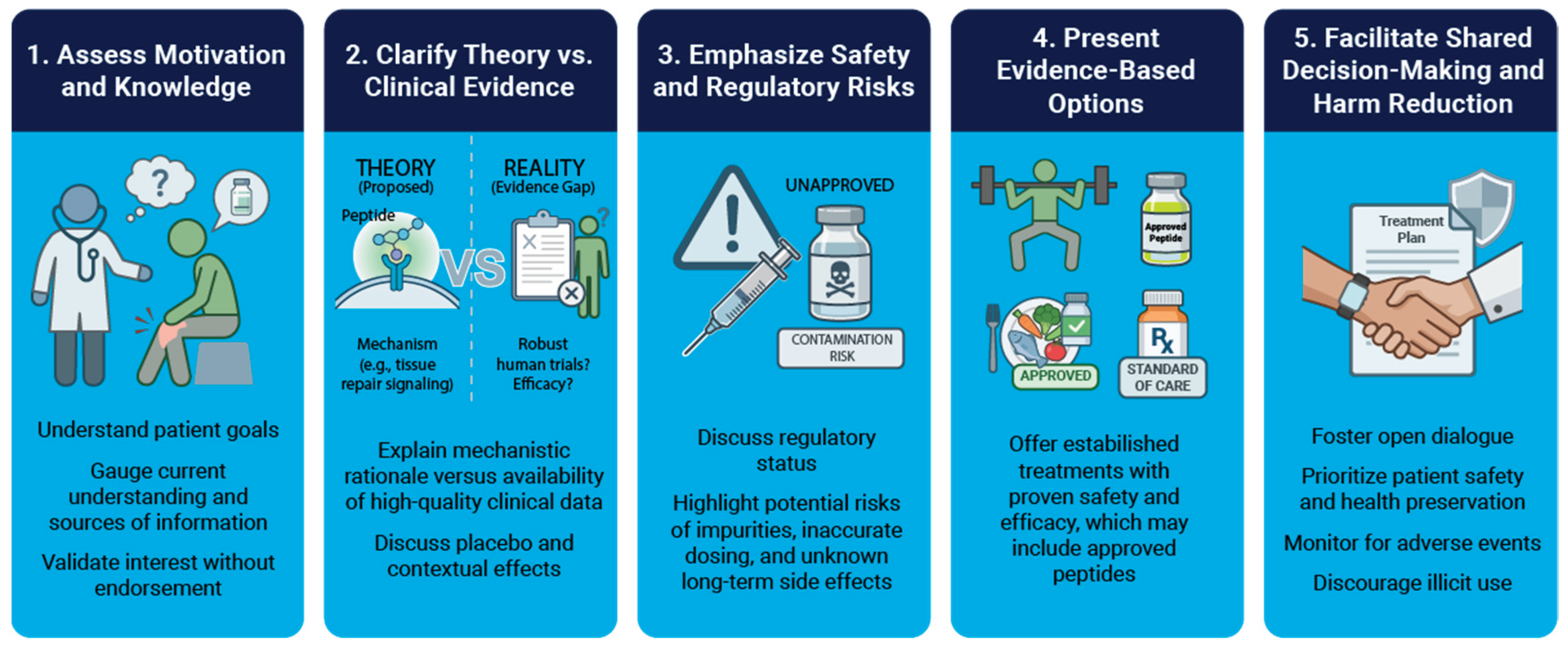

Sports medicine providers increasingly encounter patients who want to incorporate peptides in their treatment program. However, much of the motivation patients have for peptides is based on biased advertising, online forums, or gray market vendor websites [

5]. Navigating these conversations requires an approach that effectively contrasts marketing narratives with results from objective, peer-reviewed studies.

The general framework we propose to discuss peptide therapies with patients is as follows. First, clinicians should determine patient goals such as recovery or performance enhancement, and gauge patient understanding and interest in peptides. Second, clarify theory versus clinical data by explaining the proposed mechanisms for a peptide, the available scientific evidence, and the impact of placebo and contextual effects. Third, safety risks should be emphasized by highlighting the potential for contamination, inaccurate dosing, and unknown long-term side effects. Fourth, present evidence-based alternatives of established treatments with proven safety and efficacy that align with the patient goals. Finally, shared decision making should occur, prioritizing patient safety and health preservation, and monitoring for adverse events if peptide use is suspected, while at the same time discouraging illicit use. An overview is presented in

Figure 3. We review additional discussion points in Supplemental Material S1.

6. Conclusions

The integration of peptide therapy into sports medicine brings considerable opportunities to improve outcomes, yet the landscape is fraught with significant regulatory and safety hazards. While molecules like BPC-157 and TB-500 demonstrate impressive healing properties in animals, the translation to humans is stalled by a lack of rigorous, controlled trials. Of 5,000 drug candidates that enter preclinical testing, on average only five are tested in human trials, and only one of the five compounds is eventually approved for use [

96]. Future progress depends on moving peptides out of the gray market and into the transparent light of pharmaceutical development (

Figure 4). Until high-quality data emerges for unapproved peptides, sports medicine professionals must educate patients on the scientific rationale, placebo and contextual effects, and the potential risks with using unapproved compounds (

Figure 5). Clinical trials and robust safety data are needed now more than ever to bridge the widening chasm between myths perpetuated online and actual science.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplemental Table S1: Summary of peptides discussed in this manuscript. Supplemental Material S1: Additional talking points around the safe use of peptides.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CLM and TMA.; formal analysis, CLM; resources, CLM and TMA; data curation, CLM and TMA.; writing—original draft preparation, CLM; writing—review and editing, CLM and TMA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAV |

Adeno-associated virus |

| AOD-9604 |

Anti obesity drug 9604 |

| ARTG |

Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods |

| BMAC |

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate |

| BPC-157 |

Body protection compound 157 |

| cGMP |

Current good manufacturing practice |

| CMV |

Cytomegalovirus |

| EMA |

European Medicines Agency |

| ESWT |

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy |

| FDA |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FS-344 |

Follistatin 344 |

| GHK-Cu |

Glycyl L histidyl L lysine copper (copper peptide complex) |

| GHRH |

Growth hormone releasing hormone |

| GHSR1 |

Ghrelin/growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1 |

| GLP-1RA |

Glucagon like peptide 1 receptor agonist |

| hGH |

Human growth hormone |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| IGF-1 |

Insulin like growth factor 1 |

| MOTS-c |

Mitochondrial ORF of the 12S rRNA type c |

| PDE5 |

Phosphodiesterase type 5 |

| PPP |

Platelet poor plasma |

| PRP |

Platelet rich plasma |

| PTH |

Parathyroid hormone |

| SS-31 |

Elamipretide |

| SVF |

Stromovascular fraction (of adipose tissue) |

| TB-500 |

Thymosin beta 4 fragment |

| TGA |

Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia) |

| USP |

United States Pharmacopeia |

| VEGF |

Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Otvos L, Wade JD. Big peptide drugs in a small molecule world. Front Chem. 2023;11:1302169. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Wang N, Zhang W, Cheng X, Yan Z, Shao G, et al. Therapeutic peptides: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:48. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet A-L, Aboishava L, Mannstadt M. Advances in Parathyroid Hormone-based medicines. J Bone Miner Res. 2025;40:1195–206. [CrossRef]

- Vasireddi N, Hahamyan H, Salata MJ, Karns M, Calcei JG, Voos JE, et al. Emerging Use of BPC-157 in Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: A Systematic Review. HSS J. 2025;21:485–95. [CrossRef]

- Turnock DL, Gibbs DN. Click, click, buy: The market for novel synthetic peptide hormones on mainstream e-commerce platforms in the UK. Perform Enhanc Heal. 2023;11:100251.

- Sharma A, Kumar A, Torre BG de la, Albericio F. Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS): A Third Wave for the Preparation of Peptides. Chem Rev. 2022;122:13516–46. [CrossRef]

- Janvier S, Cheyns K, Canfyn M, Goscinny S, Spiegeleer BD, Vanhee C, et al. Impurity profiling of the most frequently encountered falsified polypeptide drugs on the Belgian market. Talanta. 2018;188:795–807. [CrossRef]

- D’Hondt M, Bracke N, Taevernier L, Gevaert B, Verbeke F, Wynendaele E, et al. Related impurities in peptide medicines. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014;101:2–30. [CrossRef]

- Erckes V, Streuli A, Rendueles LC, Krämer SD, Steuer C. Towards a Consensus for the Analysis and Exchange of TFA as a Counterion in Synthetic Peptides and Its Influence on Membrane Permeation. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18:1163. [CrossRef]

- Cornish J, Callon KE, Lin CQ-X, Xiao CL, Mulvey TB, Cooper GJS, et al. Trifluoroacetate, a contaminant in purified proteins, inhibits proliferation of osteoblasts and chondrocytes. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab. 1999;277:E779–83. [CrossRef]

- Janvier S, Sutter ED, Wynendaele E, Spiegeleer BD, Vanhee C, Deconinck E. Analysis of illegal peptide drugs via HILIC-DAD-MS. Talanta. 2017;174:562–71. [CrossRef]

- Høj LJ, Rasmussen BS, Dalsgaard PW, Linnet K. Analysis of seized peptide and protein-based doping agents using four complimentary methods: Liquid chromatography coupled with time of flight mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography–ultraviolet, Bradford, and immunoassays. Drug Test Anal. 2021;13:1457–63. [CrossRef]

- Sood N, Garg R. Global Rise of Compounded Weight-Loss Medicines: A Worrisome Trend. J Endocr Soc. 2025;9:bvaf084. [CrossRef]

- DiStefano MJ, Dardouri M, Moore GD, Saseen JJ, Nair KV. Compounded glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for weight loss: the direct-to-consumer market in Colorado. J Pharm Polic Pr. 2025;18:2441220. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho M, Almeida IF. The Role of Pharmaceutical Compounding in Promoting Medication Adherence. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:1091. [CrossRef]

- Yoffe A, Liu J, Smith G, Chisholm O. Regulatory Reform Outcomes and Accelerated Regulatory Pathways for New Prescription Medicines in Australia. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023;57:271–86. [CrossRef]

- Cox HD, Smeal SJ, Hughes CM, Cox JE, Eichner D. Detection and in vitro metabolism of AOD9604. Drug Test Anal. 2015;7:31–8. [CrossRef]

- Stier. Safety and Tolerability of the Hexadecapeptide AOD9604 in Humans. J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;

- Heffernan M, Summers RJ, Thorburn A, Ogru E, Gianello R, Jiang W-J, et al. The Effects of Human GH and Its Lipolytic Fragment (AOD9604) on Lipid Metabolism Following Chronic Treatment in Obese Mice andβ 3-AR Knock-Out Mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5182–9. [CrossRef]

- Valentino MA, Lin JE, Waldman SA. Central and Peripheral Molecular Targets for Antiobesity Pharmacotherapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:652–62. [CrossRef]

- Kwon DR, Park GY. Effect of Intra-articular Injection of AOD9604 with or without Hyaluronic Acid in Rabbit Osteoarthritis Model. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2015;45:426–32.

- Fedorowski A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J Intern Med. 2019;285:352–66. [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar A, Bhat S, Kapoor N. Effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists on body composition. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2025;32:279–85. [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Cruz M, Kammar-García A, Huerta-Cruz JC, Carrasco-Portugal M del C, Barranco-Garduño LM, Rodríguez-Silverio J, et al. Three- and six-month efficacy and safety of phentermine in a Mexican obese population. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;59:539–48. [CrossRef]

- Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, McDonnell ME, Murad MH, Pagotto U, et al. Pharmacological Management of Obesity: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2015;100:342–62.

- Andia I, Maffulli N. Biological Therapies in Regenerative Sports Medicine. Sports Med. 2017;47:807–28. [CrossRef]

- Józwiak M, Bauer M, Kamysz W, Kleczkowska P. Multifunctionality and Possible Medical Application of the BPC 157 Peptide—Literature and Patent Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18:185. [CrossRef]

- Lee E, Padgett B. Intra-Articular Injection of BPC 157 for Multiple Types of Knee Pain. Altern Ther Heal Med. 2021;27:8–13.

- Yang Y, Cao Y. The impact of VEGF on cancer metastasis and systemic disease. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86:251–61. [CrossRef]

- Mead MP, Gumucio JP, Awan TM, Mendias CL, Sugg KB. Pathogenesis and management of tendinopathies in sports medicine. Transl Sports Med. 2018;1:5–13. [CrossRef]

- Praet SFE, Ong JH, Purdam C, Welvaert M, Lovell G, Dixon L, et al. Microvascular volume in symptomatic Achilles tendons is associated with VISA-A score. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21:1185–91. [CrossRef]

- Chung B, Wiley JP. Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy. Sports Med. 2002;32:851–65.

- Hudgens JL, Sugg KB, Grekin JA, Gumucio JP, Bedi A, Mendias CL. Platelet-Rich Plasma Activates Proinflammatory Signaling Pathways and Induces Oxidative Stress in Tendon Fibroblasts. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1931–40. [CrossRef]

- Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. Achilles and Patellar Tendinopathy Loading Programmes. Sports Med. 2013;43:267–86. [CrossRef]

- Mendias CL, Enselman ERS, Olszewski AM, Gumucio JP, Edon DL, Konnaris MA, et al. The Use of Recombinant Human Growth Hormone to Protect Against Muscle Weakness in Patients Undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Pilot, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48:1916–28. [CrossRef]

- Weber AE, Gallo MC, Bolia IK, Cleary EJ, Schroeder TE, Hatch GFR. Anabolic Androgenic Steroids in Orthopaedic Surgery: Current Concepts and Clinical Applications. Jaaos Global Res Rev. 2022;6:e21.00156. [CrossRef]

- Teichman SL, Neale A, Lawrence B, Gagnon C, Castaigne J-P, Frohman LA. Prolonged Stimulation of Growth Hormone (GH) and Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Secretion by CJC-1295, a Long-Acting Analog of GH-Releasing Hormone, in Healthy Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:799–805. [CrossRef]

- A Study to Evaluate CJC 1295 in HIV Patients With Visceral Obesity. NCT00267527.

- GELATO MC, RITTMASTER RS, PESCOVITZ OH, NICOLETTI MC, NIXON WE, D’AGATA, R, et al. Growth Hormone Responses to Continuous Infusions of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone*. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:223–8. [CrossRef]

- Melmed S. Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Investig. 2009;119:3189–202.

- Arora NK, Donath L, Owen PJ, Miller CT, Saueressig T, Winter F, et al. The Impact of Exercise Prescription Variables on Intervention Outcomes in Musculoskeletal Pain: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Sports Med. 2024;54:711–25. [CrossRef]

- Rodino-Klapac LR, Haidet AM, Kota J, Handy C, Kaspar BK, Mendell JR. Inhibition of myostatin with emphasis on follistatin as a therapy for muscle disease. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:283–96. [CrossRef]

- Dueweke JJ, Awan TM, Mendias CL. Regeneration of Skeletal Muscle After Eccentric Injury. J Sport Rehabil. 2017;26:171–9. [CrossRef]

- Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, et al. Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4318–22. [CrossRef]

- Kota J, Handy CR, Haidet AM, Montgomery CL, Eagle A, Rodino-Klapac LR, et al. Follistatin Gene Delivery Enhances Muscle Growth and Strength in Nonhuman Primates. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:6ra15. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaidy SA, Sahenk Z, Rodino-Klapac LR, Kaspar B, Mendell JR. Follistatin Gene Therapy Improves Ambulation in Becker Muscular Dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2015;2:185–92. [CrossRef]

- Phillips DJ, Jones KL, McGaw DJ, Groome NP, Smolich JJ, Pärsson H, et al. Release of Activin and Follistatin during Cardiovascular Procedures Is Largely due to Heparin Administration1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2411–5. [CrossRef]

- Bäck S, Dossat A, Parkkinen I, Koivula P, Airavaara M, Richie CT, et al. Neuronal Activation Stimulates Cytomegalovirus Promoter-Driven Transgene Expression. Mol Ther - Methods Clin Dev. 2019;14:180–8. [CrossRef]

- Pickart L, Margolina A. Skin Regenerative and Anti-Cancer Actions of Copper Peptides. Cosmetics. 2018;5:29. [CrossRef]

- Dou Y, Lee A, Zhu L, Morton J, Ladiges W. The potential of GHK as an anti-aging peptide. Aging Pathobiol Ther. 2020;2:58–61. [CrossRef]

- Maquart FX, Bellon G, Chaqour B, Wegrowski J, Patt LM, Trachy RE, et al. In vivo stimulation of connective tissue accumulation by the tripeptide-copper complex glycyl-L-histidyl-L-lysine-Cu2+ in rat experimental wounds. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:2368–76. [CrossRef]

- Ahnfelt-Rønne I, Nowak J, Olsen UB. Do growth hormone-releasing peptides act as ghrelin secretagogues? Endocrine. 2001;14:133–5. [CrossRef]

- Raun K, Hansen BS, Johansen NL, Thogersen H, Madsen K, Ankersen M, et al. Ipamorelin, the first selective growth hormone secretagogue. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;139:552–61. [CrossRef]

- Johansen PB, Nowak J, Skjærbæk C, Flyvbjerg A, Andreassen TT, Wilken M, et al. Ipamorelin, a new growth-hormone-releasing peptide, induces longitudinal bone growth in rats. Growth Horm IGF Res. 1999;9:106–13. [CrossRef]

- Prinz P, Stengel A. Control of Food Intake by Gastrointestinal Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Possible Modulation in the Treatment of Obesity. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:180–96. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi EN, Louwies T, Pietra C, Northrup SR, Meerveld BG-V. Attenuation of Visceral and Somatic Nociception by Ghrelin Mimetics. J Exp Pharmacol. 2020;12:267–74. [CrossRef]

- Group O behalf of the I 201 S, Beck DE, Sweeney WB, McCarter MD. Prospective, randomized, controlled, proof-of-concept study of the Ghrelin mimetic ipamorelin for the management of postoperative ileus in bowel resection patients. Int J Color Dis. 2014;29:1527–34.

- Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, Larson-Meyer DE, Peeling P, Phillips SM, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:439–55. [CrossRef]

- Poher A-L, Tschöp MH, Müller TD. Ghrelin regulation of glucose metabolism. Peptides. 2018;100:236–42. [CrossRef]

- Wasko R, Jaskula M, Kotwicka M, Andrusiewicz M, Jankowska A, Liebert W, et al. The expression of ghrelin in somatotroph and other types of pituitary adenomas. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2008;29:929–38.

- Prakash A, Goa KL. Sermorelin. BioDrugs. 1999;12:139–57. [CrossRef]

- González-Sales M, Barrière O, Tremblay PO, Nekka F, Mamputu J-C, Boudreault S, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of tesamorelin in HIV-infected patients and healthy subjects. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2015;42:287–99. [CrossRef]

- Bilbao A, Spanagel R. Medical cannabinoids: a pharmacology-based systematic review and meta-analysis for all relevant medical indications. BMC Med. 2022;20:259. [CrossRef]

- Souza MJD, Strock NCA, Ricker EA, Koltun KJ, Barrack M, Joy E, et al. The Path Towards Progress: A Critical Review to Advance the Science of the Female and Male Athlete Triad and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport. Sports Med. 2022;52:13–23. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Zeng J, Drew BG, Sallam T, Martin-Montalvo A, Wan J, et al. The Mitochondrial-Derived Peptide MOTS-c Promotes Metabolic Homeostasis and Reduces Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab. 2015;21:443–54. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Wei Z, Wang T. MOTS-c: A promising mitochondrial-derived peptide for therapeutic exploitation. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1120533. [CrossRef]

- Lyons CL, Roche HM. Nutritional Modulation of AMPK-Impact upon Metabolic-Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3092. [CrossRef]

- Ishida J, Saitoh M, Ebner N, Springer J, Anker SD, Haehling S von. Growth hormone secretagogues: history, mechanism of action, and clinical development. JCSM Rapid Commun. 2020;3:25–37. [CrossRef]

- Heinemeier KM, Mackey AL, Doessing S, Hansen M, Bayer ML, Nielsen RH, et al. GH/IGF-I axis and matrix adaptation of the musculotendinous tissue to exercise in humans. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22:e1-7. [CrossRef]

- Disser NP, Sugg KB, Talarek JR, Sarver DC, Rourke BJ, Mendias CL. Insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling in tenocytes is required for adult tendon growth. The FASEB Journal. 2019;33:12680–95.

- Marshall L, Mölle M, Böschen G, Steiger A, Fehm HL, Born J. Greater efficacy of episodic than continuous growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) administration in promoting slow-wave sleep (SWS). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1009–13. [CrossRef]

- Bartke A. Growth Hormone and Aging: Updated Review. World J Men’s Heal. 2019;37:19–30. [CrossRef]

- Sinha DK, Balasubramanian A, Tatem AJ, Rivera-Mirabal J, Yu J, Kovac J, et al. Beyond the androgen receptor: the role of growth hormone secretagogues in the modern management of body composition in hypogonadal males. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;9:S149–59. [CrossRef]

- Black DS, O’Reilly GA, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Irwin MR. Mindfulness Meditation and Improvement in Sleep Quality and Daytime Impairment Among Older Adults With Sleep Disturbances: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:494–501.

- Tung C, Varzideh F, Farroni E, Mone P, Kansakar U, Jankauskas SS, et al. Elamipretide: A Review of Its Structure, Mechanism of Action, and Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:944. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Zhuang X, Gao J. Elamipretide: The first cardiolipin-directed mitochondrial therapeutic for Barth syndrome approved under accelerated approval. Drug Discov Ther. 2025;2025.01111. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Wang H, Fang J, Dai W, Zhou J, Wang X, et al. SS-31 Provides Neuroprotection by Reversing Mitochondrial Dysfunction after Traumatic Brain Injury. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:4783602. [CrossRef]

- Storoschuk KL, Moran-MacDonald A, Gibala MJ, Gurd BJ. Much Ado About Zone 2: A Narrative Review Assessing the Efficacy of Zone 2 Training for Improving Mitochondrial Capacity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in the General Population. Sports Med. 2025;55:1611–24. [CrossRef]

- Brisswalter J, Louis J. Vitamin Supplementation Benefits in Master Athletes. Sports Med. 2014;44:311–8. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein AL, Kleinman HK. Advances in the basic and clinical applications of thymosin β4. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:139–45.

- Freeman KW, Banyard J. B-thymosins in cancer: implications for the clinic. Futur Oncol. 2009;5:755–8. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings DC, Anderson SG, Caldwell JL, Trafford AW. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors and the heart: compound cardioprotection? Heart. 2018;104:1244. [CrossRef]

- Sahay S, Kwak SY. The Efficacy of Adjuvant Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in Chronic Wound Management: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2025;17:e92728. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti F. Placebo and the New Physiology of the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:1207–46. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti F, Mayberg HS, Wager TD, Stohler CS, Zubieta J-K. Neurobiological Mechanisms of the Placebo Effect. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10390–402. [CrossRef]

- Smits RM, Veldhuijzen DS, Wulffraat NM, Evers AWM. The role of placebo effects in immune-related conditions: mechanisms and clinical considerations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:761–70. [CrossRef]

- Lennep J (Hans) PA van, Trossèl F, Perez RSGM, Otten RHJ, Middendorp H van, Evers AWM, et al. Placebo effects in low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Eur J Pain. 2021;25:1876–97.

- Saueressig T, Owen PJ, Pedder H, Tagliaferri S, Kaczorowski S, Altrichter A, et al. The importance of context (placebo effects) in conservative interventions for musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain. 2024;28:675–704. [CrossRef]

- Valero F, González-Mohíno F, Salinero JJ. Belief That Caffeine Ingestion Improves Performance in a 6-Minute Time Trial Test without Affecting Pacing Strategy. Nutrients. 2024;16:327. [CrossRef]

- Pollo A, Carlino E, Benedetti F. The top-down influence of ergogenic placebos on muscle work and fatigue. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:379–88. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho C, Caetano JM, Cunha L, Rebouta P, Kaptchuk TJ, Kirsch I. Open-label placebo treatment in chronic low back pain. PAIN. 2016;157:2766–72. [CrossRef]

- González-Bailón S, Lelkes Y. Do social media undermine social cohesion? A critical review. Soc Issues Polic Rev. 2023;17:155–80. [CrossRef]

- Zamil DH, Ameri M, Fu S, Abughosh FM, Katta R. Skin, hair, and nail supplements advertised on Instagram. Bayl Univ Méd Cent Proc. 2023;36:38–40. [CrossRef]

- Ricke J-N, Seifert R. Disinformation on dietary supplements by German influencers on Instagram. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2025;398:5629–47. [CrossRef]

- Chou W-YS, Gaysynsky A, Trivedi N, Vanderpool RC. Using Social Media for Health: National Data from HINTS 2019. J Heal Commun. 2021;26:184–93. [CrossRef]

- Kraljevic S, Stambrook PJ, Pavelic K. Accelerating drug discovery. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:837–42.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).