Introduction

Compared to their heterosexual counterparts, gay men and lesbians face higher rates of mental health issues, including substance use disorders, affective disorders, and suicide (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003) (Gilman, et al., 2001) (Herrell, et al., 1999) (Sandfort, de Graaf, Bijl, & Schnabel, 2001) (Collins, Grineski, & Morales, 2017), and that gay men are more prone to adverse life outcomes than their heterosexual peers (Cochran, Stewart, Ginzler, & Cauce, 2002) (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003) (Perales & Todd, 2018). While the etiology of such differences could be more intertwined with nature and nurture, the societal aspects are assumed to be the ones we may have the best access to for intervention. This could be attributed to Minority Stress founded on the idea that stressors are not randomly experienced across society but are deeply influenced by individuals’ social positions and the broader social processes that shape their lives (Meyer I. H., 1995) (Meyer, Russell, Hammack, Frost, & Wilson, 2021). Accordingly, marginalized or minority groups face unique, chronic stressors directly linked to their social identities, such as race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation (HAGERTY & PATUSKY, 1995). These stressors arise from societal factors like discrimination, prejudice, and social exclusion, which can create an environment that places a heavier psychological and emotional burden on minority populations than on the majority. In essence, the theory emphasizes that stress is structured by social inequalities, resulting in a disproportionate impact on those in marginalized positions. On the other hand, a sense of belonging is essential to human identity and existence (Cochran S. D.) (Gilman, et al., 2001) (Herrell, et al., 1999) (Sandfort, de Graaf, Bijl, & Schnabel, 2001) (Baumeister & Leary, 1995) (Deci & Ryan, 2000) (Slavich, 2020). While a strong sense of belonging fosters positive life outcomes, the absence of this connection is closely linked to reduced meaning and purpose, increased vulnerability to mental and physical health challenges, and a potential decline in life expectancy (Allen, Kern, Rozek, McInereney, & Slavich, 2021). Homosexuality has long been a controversial issue in Iran, stemming from the stigma associated with the homophobic attitudes of ‘some’ members of society (Ahmady K. , 2021) (Moghissi, 1994). This stigma is connected to a radicalized view of sexuality, cultural norms related to sexuality and gender, and associations with religious institutions. Stringent restrictions on extramarital sexual relations have led many unmarried individuals to rely primarily on masturbation. Under Iranian Islamic law, homosexuality is considered a serious sin, perceived as detrimental to family, reproduction, and lineage (Human Dignity Trust, 2024). Consequently, homosexual individuals are often labeled as deviants and may face pressure to undergo sex-reassignment procedures and hormone therapy. Transgender individuals similarly face legal prohibitions on cross-dressing and must adhere to their reassigned sex once medical interventions are completed. In all-male educational settings, effeminate men encounter pronounced stigmatization, often surpassing that experienced by women who exhibit more macho traits. Through subjective well-being, increased attachment anxiety and avoidance, along with perceived lower social support, are associated with elevated levels of internalized homophobia (Vasmaqī, 2014). Attachment anxiety uniquely predicts internalized homonegativity, whereas avoidant attachment affects it through indirect pathways (via factors like social support) (Calvo, Cusinato, Meneghet, & Miscioscia). Trombetta et al. also reported that both attachment anxiety and avoidance are positively associated with higher internalized homonegativity levels in sexual minority individuals (Trombetta, Paradiso, Santoniccolo, & Rollè, 2024). This finding reinforces that both dimensions of insecure attachment contribute to internalized homophobia (with attachment anxiety having the more direct effect) (Trombetta, Paradiso, Santoniccolo, & Rollè, 2024). Sexual minorities frequently find themselves "coming out" and bracing against homophobia, transphobia, biphobia, and acephobia in various professional settings, including research meetings, grant proposal writing, engineering course instruction, lab supervision, and professional society gatherings. Any deviation introduced by an LGBTQIA+ individual can trigger such incidents. Society, significantly beyond localized contexts, is often characterized by misunderstanding, negative social conditioning, and biased ethics, creating an environment conducive to microaggressions and unconscious bias. These unconscious biases, as defined by The Kirwan Institute (Staats, 2014), involve attitudes or stereotypes that unconsciously influence our understanding, actions, and decisions, often working against sexual minorities. LGBTQIA+ members consistently face two types of stressors that can lead to attachment anxiety and avoidance, along with other potential effects: distal and proximal. There is indeed a link between these two types of stressors (Douglass & Conlin, 2020). There are three major proximal stressors: expectations of rejection, internalized homophobia, and concealment of one’s LGB identity (Douglass & Conlin, 2020). Expectations of rejection may precede discrimination, it has been suggested (Douglass & Conlin, 2020). The expectation can be backed up by the idea that contextual, personal, and structural factors likely interact to influence discrimination perception. In the context of minority stress theory, structural stigma is considered a distal stressor (Douglass & Conlin, 2020). To better understand how such stressors could influence the sexual minority thriving in a society, we may recall how the election of Donald Trump as president had a markedly negative impact on American adults identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). The percentage of LGBT individuals who considered their lives 'thriving' dropped by 10% after the election, from 51% to 41%. In contrast, life evaluations among non-LGBT Americans showed minimal change (Gates, 2016). Distal stressors are believed to play a role in the emergence of proximal stressors (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). For instance, discrimination precedes the development of proximal stress (Brewster, Moradi, DeBlaere, & Velez, 2013) (Denton, Rostosky, & Danner, 2014) (Douglass, Conlin, & Duffy, 2020) (Feinstein, Goldfried, & Davila, 2012). Empathy-driven interventions can significantly reduce prejudice and enhance social inclusion in marginalized communities (Cohen, 2023). Such observations could lead to the conclusion that organizations that cultivate kindness and empathy tend to have more inclusive cultures, benefiting underrepresented groups. While positive signals interpreted as kindness may have a variety of definitions, depending on the context within which the signals are sent and received, kindness is intentionally assumed to be a powerful enabler to foster a sense of belonging, as it helps to create a sense of unity and connection among individuals (Hosoda & Estrada, 2024). In the context of the academic environment, based on micronarratives from 182 individuals in a cross-sectional study, it was deduced that feeling safe and being acknowledged are the most commonly described experiences of kindness affirming dignity. Such experiences, in turn, contributed to improving diverse people’s well-being and increased identification with institutions of higher education (Hosoda & Estrada, 2024). The two psychometric rating scales for kindness were developed in that study: Kindness Received and Kindness Given. Receiving kindness was deduced to be a significant enabler for increased well-being, reduced stress, and improved institutional identity. Giving kindness was a substantial contributor to decreased stress reduction and decreased institutional identity. They found out about the mediation role of institutional identity in between receiving kindness and well-being.

This article presents a theory-driven narrative review coupled with a structured secondary synthesis of published quantitative studies on Iranian sexual and gender minorities. We introduce and apply a five-anchor framework—Subjectivity, Groundedness, Reciprocity, Dynamism, and Self-determination. To transition the conceptual framework of belonging into an empirically validated model, we propose an explanatory sequential Mixed Methods Research (MMR) design (Jenkins, Bayer, Nooraie, & Fiscella, 2023) where primary (published) quantitative data is collected and analyzed to test the core dimensions of the five anchors. Here, we demonstrate the analytical feasibility and empirical power of the five-anchor conceptual model using verifiable numerical evidence that already exists in academic literature.

Core Objective

A sense of harmony with the environment is the basis of healthy living, and deviation from such a sense may be considered a source of minority stress (Sutterley & Donnelly, 1981). An individual can experience a sense of belonging to multiple relationships, groups, systems, or entities simultaneously, with each situation fostering a distinct sense of belonging specific to that relationship (Mahar, Cobigo, & Stuart). An individual can experience a sense of belonging to multiple relationships, groups, systems, or entities simultaneously, with each situation fostering a distinct sense of belonging specific to that relationship (Allen, Kern, Rozek, McInereney, & Slavich, 2021). It was proposed that ‘subjectivity,’ ‘groundedness,’ ‘reciprocity,’ ’dynamism,’ and ‘self-determination’ are essential to a transdisciplinary and multidimensional understanding of the sense of belonging. In a separate study, researchers proposed a comprehensive framework to enhance knowledge, assessment, and promotion of a sense of belonging (Allen, Kern, Rozek, McInereney, & Slavich, 2021). That model emphasizes four interconnected components essential to fostering belonging: competencies, or the skills individuals possess to engage in social connections; opportunities, which refer to the contexts and chances for social interaction and community integration; motivations, or the personal drive and desire to seek connection; and perceptions, which involve the individual’s interpretation and evaluation of their social experiences and interactions. Based on the latter and former studies, the understanding of the sense of belonging and proposed interventions is discussed in this review. This paper aims to highlight the challenges, both observed and personally experienced, that hinder a sense of belonging and fair treatment within Iranian society. Discrimination against sexual minorities is an integral part of their daily lives. In theocratic societies, additional coping mechanisms are required to navigate the prevailing homophobic environment.

Method

Design and approach

We conducted a theory-driven narrative review with a structured secondary synthesis of previously published, de-identified quantitative studies concerning Iranian sexual and gender minorities (no new human participants).

Sources and eligibility

We considered peer-reviewed studies (English or Persian) with no time limit that reported numeric and qualitative indicators relevant to at least one anchor (e.g., internalized stigma, depression/suicidality, arrest/harassment, peer support, emotion regulation). Non-Iran settings were excluded from the synthesis, but informed the background.

Selection and extraction

We combined database/hand searching and citation chaining, screened titles/abstracts/full texts for anchor relevance, and extracted summary statistics as reported (no re calculation).

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Indicators were coded to five anchors (Subjectivity, Groundedness, Reciprocity, Dynamism, Self determination) and narratively synthesized by anchor. We did not conduct meta analysis due to heterogeneity in measures, designs, and sample frames.

Reflexivity and ethics

Given criminalization risks, we report aggregate indicators only and avoid potentially identifying combinations. As a secondary analysis of published data, ethics approval and consent were not required.

Selection and extraction

We combined database/hand searching and citation chaining, screened titles/abstracts/full texts for anchor relevance, and extracted summary statistics as reported (no re-calculation).

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Indicators were coded to five anchors (Subjectivity, Groundedness, Reciprocity, Dynamism, Self-determination) and narratively synthesized by anchor. We did not conduct meta-analysis due to heterogeneity in measures, designs, and sample frames.

Reflexivity and ethics

Given criminalization risks, we report aggregate indicators only and avoid potentially identifying combinations. As a secondary analysis of published data, ethics approval and consent were not required.

Results & Discussion

Five Anchors

The results are organized around five anchors of belonging: Subjectivity, Groundedness, Reciprocity, Dynamism, and Self-determination. For each anchor, we first delineate its conceptual contours, then situate it within the Iranian sociolegal and everyday context. and synthesize convergent patterns in the literature to show how belonging, risk, and resilience take shape. To demonstrate the feasibility and analytical power of the five-anchor model, each subsection concludes with a concise quantitative index that captures the magnitude of the phenomenon under review, giving the reader a clear empirical foothold for the arguments advanced in the narrative. We present a quantitative synthesis that maps key published psychometric data from Iranian sexual and gender minorities studies directly onto the conceptual dimensions of belonging. These metrics function as projected results, indicating the type of empirical validation the proposed survey would yield and providing numerical context for the conceptual model.

Table 1 represents the empirical validation of the above-mentioned five belonging anchors synthesized, real quantitative results (Projected Synthesis) meticulously drawn from multiple, distinct, and already published academic surveys and peer-reviewed studies conducted on Iranian sexual and gender minority populations. The integration of these empirical markers demonstrates the utility of the five-anchor framework for both analyzing and measuring the minority stress experience in the Iranian context, paving the way for targeted, evidence-based intervention strategies. The projected quantitative findings substantiate the theoretical necessity of the five-anchor model in a repressive environment.

1. Foundation & Groundedness; Family

Groundedness refers to an external reference point or group that shapes and stabilizes an individual's perception of belonging. Family is one of the most important socioecological systems shaping health and development (Hall, 2018). Rejection by parents may harm attachment, as youth lose their safe base—their family of origin. This loss can lead to emotional turmoil, social withdrawal, and a cautious, uncertain view of interpersonal bonding and relationships with close friends and significant others (Rosario. Implications of childhood experiences for the health and adaptation of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: Sensitivity to developmental process in future research, 2015). To enhance the sense of belonging within the three layers of the gay community (community, groups, and friends) and the general community, it is hypothesized that approaches like family therapy interventions can effectively educate and assist multiple layers of the community in processing their reactions to sexual minorities. Furthermore, these approaches can help them cope with challenging responses from their immediate society, given the promising results from family therapy interventions (Diamond, et al., 2013). Similarly, looking at the intrinsic interactions among the sexual minority youth and their supportive friends, it is deduced that how accepting the information without commotion, being open-minded, signaling that they had suspected the news, continuing to be loving or caring, and respecting individuals’ LGBTQIA+ friends (Benhorin, 2008), and overall being active allies can be mimicked by other layers of the general community. In the Iranian context, the family—traditionally viewed as the core site of belonging—often serves as the primary locus of symbolic exile and emotional displacement. While legal pressures force queer Iranians into concealment or corrective measures such as sex reassignment surgery, families may further pathologize or disown their children in efforts to preserve social reputation or religious honor. This dual rejection—from the state and from kin—erodes not only the foundation of personal identity but also the broader architecture of trust and relational safety that the family is supposed to offer. Therefore, rather than functioning as a stabilizing reference point for groundedness and belonging, the family becomes a landscape of moral surveillance, silence, and internalized violence. On top of early coming-out and homophobic bullying, lack of family support was found to predict suicidal ideation or attempt (Wang, et al., 2019). It has been found that shame, family rejection, cultural pressure, lack of social support, victimization, discrimination, and poor-quality relationships are predictors of suicide attempts among queer individuals (Marshal, et al., 2011) (Matarazzo, et al., 2014) (McDermott & Roen, 2016) (Ryan C. , Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Family rejection is strongly linked to mental health issues, suicidality, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors (Bouris, et al., 2010) (Simons, Schrager, Clark, Belzer, & Olson, 2013) (Ryan C. , Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009) (Newcomb, et al., 2019) (Cochran, Stewart, Ginzler, & Cauce, 2002) (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003) (Perales & Todd, 2018) (Meyer I. H., 1995) (Douglass & Conlin, 2020) (Gates, 2016) (Vasmaqī, 2014). Among the white and Latino LGBTQIA+, higher rates of family rejection were significantly associated with poorer health outcomes (Ryan C. , Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Queer young adults who faced high levels of family rejection during adolescence were 8.4 times more likely to attempt suicide, 5.9 times more likely to experience depression, and 3.4 times more likely to use illegal drugs or engage in unprotected sex compared to those from families with low or no rejection (Ryan C., Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Given the sociocultural context in Iran, where homosexuality is often stigmatized and associated with severe legal and social consequences, the impact of familial rejection can be particularly profound. The absence of familial support compounds the existing stressors of living in a society with prevalent homophobic attitudes, leading to a greater sense of isolation. While parental monitoring and parent-adolescent communication are generally recognized as protective factors for adolescent health behaviors, the correlation regarding health outcomes among LGBTQIA+ youth appears mixed. Some studies have found that monitoring and communication are negatively associated with sexual risks in young gay and bisexual men, while others found the correlation to be the opposite. The situation of sexual minorities in Iran presents an extreme case of familial rejection, often intertwined with cultural, religious, and legal stigmatization (Mohammadi N. , 2018). In this context, the family becomes a site of conflict and exclusion. Many sexual minority individuals in Iran experience profound isolation and distress due to the inability to align with heteronormative familial expectations, leading to social displacement, mental health struggles, and, in severe cases, suicidal ideation (Mohammadi N. , 2018) (Kabir & Brinsworth, 2021). That is why sexual minorities in Iran suffer elevated depression and suicide risk, consistent with the claim’s description of isolation and mental health struggles under heteronormative pressure (Kabir & Brinsworth, 2021). In a national survey of 235 Iranian transgender individuals, 83% reported current suicidal ideation (Taranom Arianmehr & Younes Mohammadi, 2023). Such a very high prevalence of suicidal thoughts among Iran’s transgender population illustrates the extreme psychological distress that the claim alleges. Another clinical study of Iranians with gender dysphoria found “pervasive prevalence of psychological disorders, particularly depression,” and showed that higher psychological distress strongly correlated with pro-suicidal attitudes (Assareh, Rashedi, Ardebili, Salehian, & Shalbafan, 2024). It underscores that Iranian gender-diverse people face profound emotional strain and heightened suicide risk, as the claim states. Iranian parents often respond to a child’s transgender identity with maladaptive, punitive actions “including abuse to avoid stigma” (Heidari, Naji, & Abdullahzadeh, 2025). Heidari et al. (Heidari, Naji, & Abdullahzadeh, 2025) documented extreme family rejection and pressure on sexual minority youth, exactly the heteronormative familial enforcement that the claim implicates. Yadegarfard’s interviews (Yadegarfard, 2019) with Iranian gay men include cases where families forced conversion therapies, exacerbating mental anguish. For example, one participant said of a forced “treatment” by his family: “I got worse… anxiety…and at the end… I really wished I was dead.” This firsthand account powerfully illustrates how family-imposed heteronormativity leads to profound isolation, depression, and even suicidal ideation. Given this harsh reality, interventions akin to family therapy must be reimagined within socio-religious contexts to provide not only individual support but also structural changes in how families process and react to LGBTQIA+ identities. Such approaches could help mitigate the extreme exclusion faced by these individuals and foster more inclusive community structures.

1.1. Key Quantitative Link

In a national Iranian transgender survey (n = 235), 83% reported current suicidal ideation (mean Beck SI 12.8 ± 8.8), a catastrophic failure of Groundedness that aligns with the familial rejection and structural stigma developed in this section (Taranom Arianmehr & Younes Mohammadi, 2023) (

Table 1).

1.2. Family, Manifestation of Sexual Satisfaction Rights

In societies governed by Islamic Sharia, such as Iran, sexual rights and their expression within the family are often viewed through patriarchal lenses that systematically marginalize queer existence within the most intimate social unit: the family. As Sedigheh Vasmaghi rigorously critiques, traditional jurisprudential interpretations—particularly in Shiʿi thought—frame sexual satisfaction predominantly as a male right, with only limited, often symbolic, recognition of a woman’s sexual agency (Vasmaqī, 2014). For instance, some schools of jurisprudence suggest that a woman is entitled to sexual fulfillment only once in a lifetime. In contrast, others reduce her rights to the condition of male willingness (Vasmaqī, 2014). Even when women’s rights are nominally acknowledged, they are echoed in the language of male generosity, not legal or spiritual obligation. This one-sided conceptualization undermines gender equity within heterosexual marriages and cements a heteronormative, patriarchal structure that entirely delegitimizes non-heterosexual desire. In such a system, queerness becomes unspeakable and unfathomable—not just in public but also at the household level. The result is an intimate environment where queer individuals are either forcibly closeted or existentially erased, unable to claim the most basic relational entitlements, including emotional intimacy, affection, or safety. This jurisprudential erasure directly compounds the psychosocial distress experienced by queer individuals in familial settings. Minority stress theory posits that structural stigma—such as religious and legal frameworks that invalidate queer identities—manifests as chronic identity-based stressors that severely impact mental health. Familial rejection, often justified by invoking moral or religious ideals of purity, functions as a proximal stressor that severs adolescents from their primary attachment base (Rezaei-Toroghi, 2020) (Foucault, 1984). The consequences are severe: sexual minority youth from rejecting families are over eight times more likely to attempt suicide and five times more likely to suffer from depression than their supported counterparts [

45].

2. Affinity and Resonance: Heterotopias in Persian Gardens

Environmental congruence—the alignment between an individual and their surrounding milieu—is hypothesized to foster stability and fulfillment through selective reinforcement (Strange & Banning, 2001). Conversely, incongruence precipitates dissatisfaction, compelling individuals to resolve this dissonance through one of three strategies: seeking an environment that aligns with their identity (e.g., moving to a city with a vibrant art scene), reshaping the existing space (e.g., redecorating a room to reflect personal tastes), or adapting to its prevailing norms (e.g., conforming to workplace culture).

The Persian chahar bagh (four gardens) (Foucault, 1984) emerges as a potent metaphor for this reconciliation, offering a spatial paradigm where harmony is both cultivated and negotiated. Traditional Persian gardens transcend mere flora and water aesthetic compositions; they are profound spatial articulations of cosmological dualities and existential paradoxes, meticulously inscribed within their geometric confines. The garden, as the smallest parcel of the world, represents the entirety of the world, making it a joyful, universalizing heterotopia (Foucault, 1984). These gardens, with their role as microcosmic representations of the universe, embody the interplay of the four cardinal elements—water, earth, air, and fire—as fundamental constituents of the natural and metaphysical order (Foucault, 1984). At the garden’s nucleus lies the howz—a reflecting pool with a fountain—serving as an ontological umbilicus, a ‘navel of the world’ through which the multiplicity of existence is anchored into a singular, contemplative locus of equilibrium. Within this heterotopic space, reciprocity, particularly among marginalized identities, finds both refuge and resonance, cultivating an alternative mode of relationality that resists hegemonic spatial and social orders. This sanctuary takes on a profound significance when we consider the surrounding environment; the plateau, characterized by its arid and treeless nature, enhances the gardens’ value as a unique refuge. It is within this dry landscape that queer gathering finds fertile ground, and the howz becomes a symbol of hope and connection for those seeking belonging in Iran. Rather than merely existing in isolation, the gardens become a vital link—a testament to the resilience of marginalized communities navigating their existence in a world marked by societal constraints and a longing for community (Wilber, 1979). Heterotopia is an intriguing and intricate concept that comes alive within the Iranian sexual minority community. Even in the face of intense societal scrutiny and stringent governmental oversight, Persian LGBTQIA+ individuals engage in a myriad of actions and strategies to forge strong social networks. These networks foster various forms of reciprocity and trust, enabling them to nurture their intimate circles. Eyewitnesses suggest that the visibility and characteristics of these sexual minority communities can significantly impact their vulnerability across different situations (Ahmady K., 2021). Social gatherings, be they birthday parties or anniversaries, can attract varying responses from the police, particularly when attendees display distinctive attire and makeup. While there have been some encouraging signs for homosexuals in Iran, like the emergence of social events in major cities, the overall landscape remains deeply troubling. Conversely, Iranian homosexuals have created fictive kinships and developed close-knit friendship groups, empowering them to negotiate their identities and cultivate a new sense of social belonging (Ahmady K., 2020).

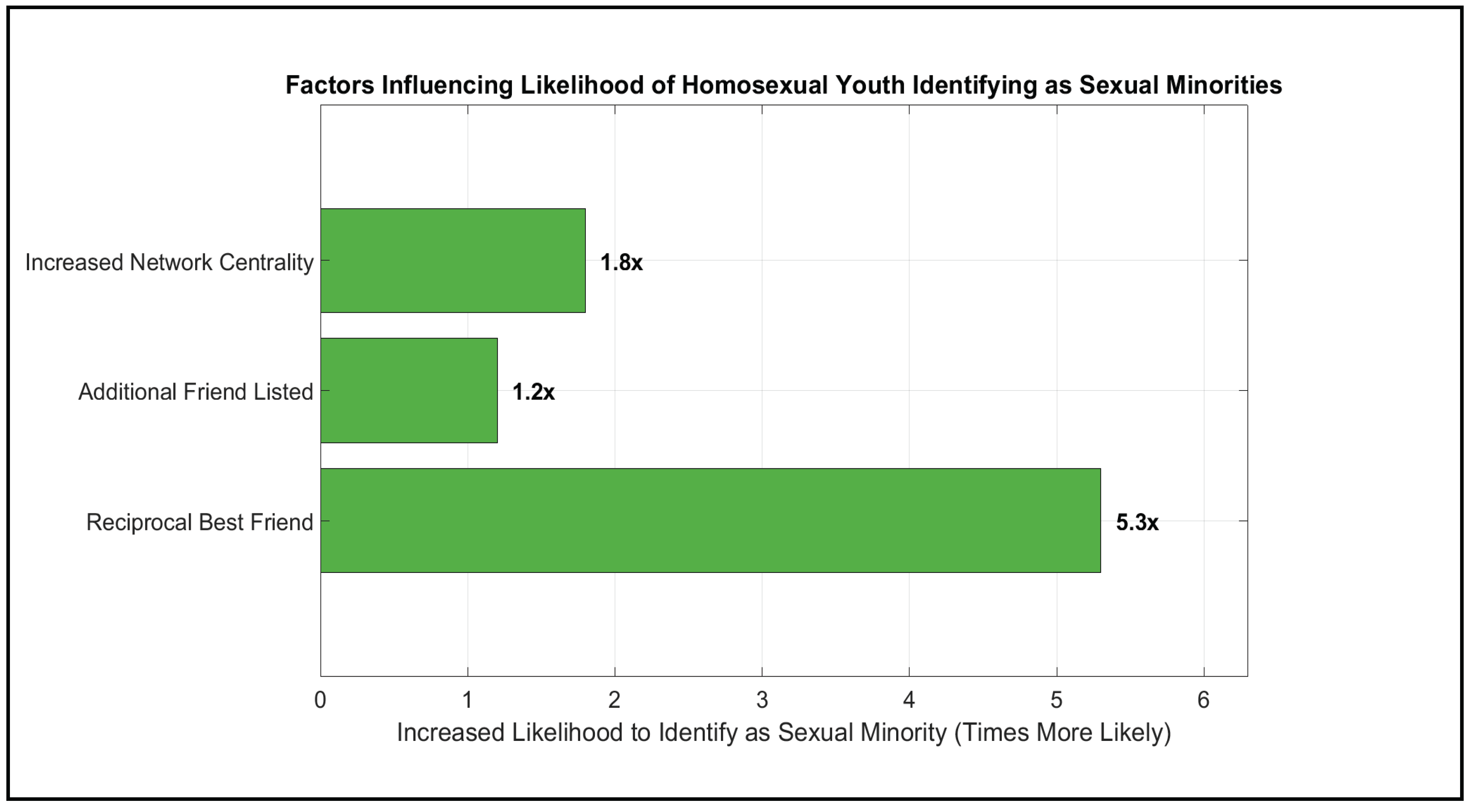

The LGBTQ+ community gains significant benefits from experiences of reciprocity that span from adolescence into adulthood (Kuhlemeier, 2022). Embracing and recognizing a predominant gay or lesbian sexual orientation within a society often marked by heterosexism and homophobia is pivotal in the journey of identity formation for many. This transformative process, commonly referred to as 'coming out'—both to oneself and to others—plays a crucial role in gay and lesbian identity development (Fassinger & Miller, 1997). Furthermore, the characteristics of friendship networks have a notable interactive influence on sexual orientation, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Research indicates that homosexual youth who cultivate reciprocal best friendships are a striking 5.3 times more likely to identify themselves as part of a sexual minority group (Kuhlemeier, 2022). Moreover, for each additional friend within these networks, this probability increases by 1.2 times, while enhanced centrality or prominence within these friendship circles can amplify this likelihood by an additional factor of 1.8 times (Kuhlemeier, 2022).

Figure 1.

The characteristics of friendship networks have a notable interactive influence on sexual orientation.

Figure 1.

The characteristics of friendship networks have a notable interactive influence on sexual orientation.

During the early 1980s, it was hypothesized that homosexual individuals used substances to cope with feelings of isolation, reduce sexual inhibitions stemming from internalized homophobia, and mitigate the stress of competing for attractive sexual partners (Colcher, 1982). Over time, however, research began to emphasize the pivotal role of friends—alongside family, coaches, teachers, therapists, and neighbors—in providing support, fostering a sense of belonging, and ultimately influencing substance use behaviors among LGBT youth (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: critical role of disclosure reactions, 2009). Based on a semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 23 transgender individuals in Iran, individuals with gender dysphoria are in urgent need of affinity from family and social support. The absence of these components endangers their security and exacerbates their psychological crises, as well as personal, family, and social stress (Mohammadi, Masoumi, Tehranineshat, Oshvandi, & Bijani, 2023). Transgender individuals who maintain affinity with their families experience higher levels of self-esteem, develop a positive self-image, gain access to a more muscular support system, and perceive greater social support (Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015). Also, engaging in online communication within transgender communities on social networks emerged as a positive factor, enhancing their emotional health and fostering resilience (Ozturk & Tatli, 2016). Despite such a repressive atmosphere, the Iranian queer has been avid and successful in pulling up the effect of stigma, discrimination, and harassment, to some finite extent, by generating and cloning heterotopic private spaces of reciprocity (Kjaran, 2019). While such spaces are temporal, they are precariously unstable sites of queer exposure and sociality. Such sites vary from luxurious parties in penthouses to medium-sized basement apartments. The metamorphosis of such spaces can be understood as a queer heterotopia, a space for the other to constitute themselves in a reality that is not readily available or legitimized outside of that space (Foucault, 1984). The shape and form of reciprocity and types of ‘friendliness’ the participants exchange may vary depending on where and by whom those spaces are offered. The queers cultivate heterotopias, whether clandestine house gatherings, underground tattoo parlors, or digital networks, which provide sanctuary, self-expression, and communal solidarity (Kjaran, 2019) (Foucault, 1984). They enable a sense of belonging, allowing individuals to resist societal erasure and redefine relationality within restrictive cultural and legal frameworks. Still, the queer heterotopias remain precarious. Their success is shaped by economic privilege, with wealthier individuals accessing safer spaces while others face heightened risk from state surveillance and moral policing (Ahmady K., 2021). Yet, these spaces persist, adapting to shifting constraints and proving that queer life in Iran, though fraught with challenges, continues to evolve through resilience and reimagination (Kjaran, 2019). Creating such heterotopias has progressively permeated into the crisis heterotopias - Iranian primitive society.

Key Quantitative Link

Peer support among SGM networks significantly predicted counter-normative behavior during COVID-19 (OR = 1.147, p < .001), indicating that clandestine friendship/kinship ties do not just soothe isolation; they generate independent norms of care and action—the empirical backbone of Affinity & Resonance in heterotopic spaces (Paykani, Zimet, Esmaeili, Khajedaluee, & Khajedaluee, 2020) (

Table 1).

3. Dynamism

Although belonging is subjective, it exists within a dynamic social milieu (Allen, Kern, Rozek, McInereney, & Slavich, 2021). Broadly defined social, cultural, environmental, and geographical frameworks shape individuals’ understanding of what is acceptable, guide their sense of right and wrong, and influence feelings of belonging or alienation (Allen K. A., 2020). Belonging is shaped by the people, objects, and experiences within one’s social environment, which interacts fluidly with an individual’s personality, past experiences, cultural background, identity, and personal perceptions; belonging exists “because of and in connection with the systems in which we reside” (Kern, et al., 2020). Opportunities must be created and barriers reduced at individual, institutional, and societal levels to foster positive connections and discourage people from seeking belonging in harmful contexts, e.g., radicalization, extremism, and engagement in gangs and organized crime. For LGBTQIA+ individuals, belonging is often not a fixed experience but one that fluctuates with changes in surroundings, relationships, and societal acceptance. The lasting or constantly shifting nature of belonging for sexual minorities can be understood through the lens of physical and social environments that either enhance or diminish one’s sense of connection. These environmental influences can be temporary or leave a lasting impact on an individual’s sense of belonging, creating a dynamic tension (Mahar, Cobigo, & Stuart). For the sake of establishing a positive dynamism between the queers and the environment, we may want to focus on ‘opportunities.’ Having a thriving dynamism sounds unduly ambitious if there aren’t opportunities to connect. As elaborated in (Correa-Velez, Gifford, & Barnett, 2010) and (Keyes & Kane, 2004), marginalized populations, including those from underserved regions and migrant backgrounds, face more significant challenges in managing psychological well-being, physical health, and life transitions. Despite possessing social competencies, their circumstances restrict their opportunities to utilize them. Now, the question is what the available dynamism is within Iranian society, as an Islamic state, for the queer community.

3.1. Key Quantitative Link

State hostility is structurally measurable: 12.6% of SGM respondents reported police arrest explicitly because of identity, expression, or orientation (Iran: Query response on the situation and treatment of the LGBTQI+ community, 2024). This numeric risk shapes the day-to-day calculus of visibility, mobility, and opportunistic connection that defines Dynamism in Iran (

Table 1).

3.2. A Tyranni; Heteronormative-Dynamic

In the Iranian context, sex-change surgeries presents a stark contrast to this dynamism as a feature of authentic belonging. Instead of fostering an environment where individuals can express their identities freely, the Iranian state's approach may represent a coercive measure that compels individuals to conform to a rigid binary gender system (Thirani Bagri, 2017), which is forced on people by the Islamic state to assimilate them into the heteronormative gender order. In Iran, the increasing prevalence of sex-change surgeries can be viewed as a reflection of the oppressive societal structures that prioritize heteronormative ideals over personal autonomy (Tait, Sex changes and a draconian legal code: gay life in Iran, 2007). This state-sanctioned intervention can be seen as a distortion of the inherent dynamism of gender identity, forcing individuals into specific roles that align with patriarchal norms rather than allowing for genuine self-identification (Tait, A fatwa for freedom, 2005) (Tait, Sex changes and a draconian legal code: gay life in Iran, 2007). The lack of awareness and understanding surrounding sexuality leads many individuals to feel pressured into undergoing medical procedures that may not align with their true selves (Tait, A fatwa for freedom, 2005) (Carter, 2020). In other words, while the state's legalization and funding of these surgeries might be framed as progressive, they ultimately reinforce binary constraints and suppress the potential for a more inclusive understanding of gender fluidity (Tait, Sex changes and a draconian legal code: gay life in Iran, 2007) (Hamedani, 20). Iranian LGBTQIA+ seems to be emerging from the deafening silence, and international institutions are hearing their still-cautious voices. In Western societies, particularly in the U.S., there exists a classic dynamic between two movements: one that champions progress and another that counters it. Each movement's strategies and actions significantly influence the other as they make competing claims about shared issues (Stone, 2016). However, the situation for LGBTQIA+ individuals in Middle Eastern societies unfolds on a different, more complex battleground. Here, there are two primary perspectives on LGBTQIA+ identities. One perspective focuses on individuals navigating their sexual and gender identities while dealing with daily challenges. The other, often rooted in more regressive ideologies, is heavily influenced by the political authority of Islamic states. Within this ideological framework, there exist groups that, despite their pointed views, may advocate for religious acceptance of LGBTQIA+ identities (Afshari, 2016).

3.3. Transparency The Sin

Discouragement from telling the truth about sex and avoiding confession is a common maxim strongly advocated by Islamic moral codes, the juridical system, sexual language, social relations, and official policies (Rezaei-Toroghi, 2020). Therefore, ‘sinful’ activities that do not harm others could be forgiven simply through private penitence to God. Any acts of adultery, masturbation, jealousy, and sodomy could be forgiven in this manner if the individual does not harm anyone and does not express these actions publicly. In other words, penitence is fundamentally a private and immediate relationship with God, who supposedly purifies believers from sin and saves them from prescribed punishment as well. Thus, a significant gap exists between private and public actions. In a society where victims of sexual assault face punishment, the environment for queer individuals becomes extremely unhealthy and toxic. For instance, hadith (religious sources outside of the Quran) suggests that a woman who confesses to adultery faces double punishment: first for admitting her sin and second for accusing a Muslim man. This discouragement of penitence only further discredits the victims. Another dimension of anti-transparency is the nature of the official language in the country, Persian, which is recognized as a gender-neutral language (Rezaei-Toroghi, 2020). This characteristic creates a conducive environment for employing a strategy of obscurity. Historically, women’s roles often went unacknowledged in both economic and social realms, which could explain the prevalence of this linguistic neutrality. The custom of referring to women by their children’s names (like "mother of Ashkun") or through the names of male relatives (such as "Kourosh’s sister" or "Amir’s daughter") was viewed as a liberating approach to female identification, especially in the presence of non-relatives, a practice that persisted until the late 1990s. In this context, family titles like mother (Madar) or father (Peder), sister (Khawar), and brother (Baradar) were among the few gendered terms that could be used. This restrictive mindset provides insight into the environment’s impact on the health and acceptance of queer identities. While this kind of linguistic expression might spark dialogue, it can also deepen the feelings of closeted identities. Interestingly, this method of linguistic camouflage isn't solely a widespread societal behaviour; it has also been promoted by so-called intellectual figures in Persian culture, such as Mohammad Ghazzaali (al-Ghazali, 2023). Around the mid-1990s, a wave of political and sexual liberalization introduced human rights language into Iran, creating a more positive discourse around the stigmatized and criminalized sexual minorities in the public sphere (Korycki & Nasirzadeh, 2016). This shift was met with a backlash from the regime, which sought to vilify the West and paint same-sex identity as a foreign import, a narrative that homophobic cultural nativists readily embraced, positing homosexuality as an issue confined to "the West" (Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of IranianModernity, 2005). It is noteworthy that there are proverbs and poems that advocate for women to maintain a sense of anonymity, and this notion extends to boys as well (Korycki & Nasirzadeh, 2016). This lack of clarity reveals deeper layers of social expectations. In classic literature, boys too have been viewed as objects of desire for men, illustrating a broader theme in gender discourse (Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of IranianModernity, 2005). In this context, a gay identity often emerges as one that is completely distanced from conventional societal norms. This idea is underscored by the statements of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the elected leader of the regime, who infamously declared, "In Iran, we don’t have homosexuals, like in your country. We don’t have that in our country. In Iran, we do not have this phenomenon. I don’t know who’s told you that we have it" (Rasti, 2018). The intentional maintenance of opacity within the Iranian sociopolitical landscape ironically perpetuates the visibility it strives to diminish. Korycki and Nasirzadeh (Katarzyna Korycki, 2016) assert that the regime’s outright denial of homosexuality, exemplified by Ahmadinejad’s notorious claim, serves as a performative denial that highlights the state's significant involvement in controlling desire. This denial does not eliminate queer identity; instead, it reinforces it, creating a rigid categorization within legal and medical discourse that transforms actions into stigmatized identities. Here, transparency is not merely discouraged; it is criminalized. Thus, the Iranian queer individual appears not as an anomaly in the face of repression but emerges through it—an identity sculpted from denial and deliberately kept in the shadows. Within post-revolutionary Iran, transparency is seen not as a pathway to freedom but rather as a potential trap leading to punitive exposure. Rezaei-Toroghi (Rezaei-Toroghi, 2020) refers to this situation as a politics of “un-truth,” wherein the goal shifts from expressing one’s genuine self to upholding a calculated silence. In the context of Shi’a Islam, confession—a crucial component of Western notions of subjectivity—is supplanted by a theology of concealment, suggesting that sins remain forgivable only when unspoken. Once these sins are voiced, they transcend personal failings, transforming into prosecutable offenses. This complex structure intertwines theology and law, rendering queer self-expression not only sinful but inherently perilous (Rezaei-Toroghi, 2020). Therefore, the very act of acknowledging one’s desires, or identifying oneself as “gay,” morphs into something beyond a mere ethical expression; it becomes a legal risk. Within this paradigm, queerness is only understood through the lens of its prohibition.

This legal-theological politics of concealment maps onto lived risk: the 12.6% arrest rate linked to identity/expression helps explain why calculated silence often substitutes for transparency (Iran: Query response on the situation and treatment of the LGBTQI+ community, 2024) (

Table 1).

4. Subjectivity

4.1. Affective Dimensions of Queer Subjectivity in Iran

It was explained quite clearly (Mahar, Cobigo, & Stuart) (Ahmed, 2014) (Ledgerwood, 2021) (Welle, 2021) how belonging is inherently subjective, emphasizing individual perceptions of being valued and respected, which aligns with the idea that interventions targeting minority stress must focus on fostering these personalized feelings. Research has shown that environments do not respond equally to all individuals, and the ability to achieve environmental mastery—defined as effectively navigating, shaping, and exerting control over one’s surroundings—is often unequally distributed (Ton, 2018). These disparities are influenced by systemic factors such as race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other intersecting identities (Najmabadi, Transing and Transpassing across Sex-Gender Walls in Iran, 2008). Individuals from marginalized or underrepresented groups frequently encounter barriers that limit their access to opportunities for environmental engagement and success. These inequities reflect broader social structures that privilege certain groups while disadvantaging others, perpetuating cycles of exclusion and unequal power dynamics within various social, cultural, and institutional contexts.

For members of the Persian queer community, these barriers are not only institutional but deeply embedded in cultural (Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of IranianModernity, 2005), religious, and legal frameworks that dictate strict norms around gender and sexuality. In Iran and among Persian diasporas, heteronormativity and patriarchy reinforce exclusionary practices that often lead to profound social alienation and forced concealment of identity (Guitoo, 2021). The subjective experience of belonging, in this context, is largely shaped by familial acceptance, legal recognition, and access to safe queer spaces, all of which are extremely limited or non-existent within the dominant Persian sociopolitical framework.

4.2. Performing Identity: Queer Performativity under Constraint

Despite possessing the necessary interpersonal skills, access to social opportunities, and motivation for belonging, individuals may still experience significant dissatisfaction with their sense of belonging (Allen, Kern, Rozek, McInereney, & Slavich, 2021). Moreover, most individuals, whether consciously or subconsciously, continually assess their sense of belonging or fit within their social surroundings. Such assessment is informed by their past encounters (Coie, 2004). Negative encounters, such as a history of rejection or ostracism, may cause individuals to seek connection through alternative means, including affiliation with antisocial groups such as cults, street gangs, or radicalized organizations, or by attempting to reclaim a sense of place within communities or environments that have marginalized their worth (Flowerday & Shaughnessy, 2005). For Persian LGBTQIA+ individuals, rejection from family and cultural communities—which are traditionally central to Persian identity—often leads to emotional isolation and a higher susceptibility to external influences. Given the stigma surrounding queer identity, some individuals turn to underground or risky networks, seeking validation in places that may exploit their vulnerability. Others, particularly those who emigrate, struggle with double displacement, feeling neither fully integrated into their host societies nor welcome in their original communities.

A person's subjective sense of belonging can fluctuate even within a single day, influenced by the range of situations and experiences they encounter and their perceptions of those experiences—much like how happiness and other emotions shift over time (Trampe, Quoidbach, & Taquet) A variety of daily events and stressors shape it. It is noteworthy that a person’s experience of belonging can range from consistently high or low across time and situations to highly variable, depending on their awareness and perception of social cues and environmental context (Schall, LeBaron, & Chhuon, 2016). In alignment with Minority Stress Theory, the impact of belonging-related stressors tends to be more pronounced for individuals identifying with outgroups, including sexual minorities (Elliot, Dweck, & Yeager, 2018). To this end, we may seek a set of processes and factors that converge for a stable, trait-like sense of belonging to emerge and support the well-being of queer individuals.

4.3. Postcolonial Contexts and Queer Subject Formation

For Persian queers, the shifting perception of belonging is even more intense due to legal threats, social surveillance, and lack of visibility. In restrictive environments like Iran, merely existing as an LGBTQIA+ person can be a source of existential anxiety, which makes stability in belonging difficult. Among Persian diasporas, the experience is often fractured—while they may find greater acceptance in Western societies, racialization and cultural dissonance create another layer of exclusion, further destabilizing the sense of belonging. A practical approach towards nurturing and initiating the subjectivity element could involve personalized mentorship programs tailored to individual experiences and needs, aiming to foster a sense of value and respect in LGBTQIA+ individuals (Massad, 2002). For Persian queers, culturally sensitive mentorship and online networks can be particularly effective, given the limitations of physical safe spaces in Persian-majority settings. Internalized homonegativity is a proximal minority stress process and, as such, it is a subjective negative experience related to one’s identity as a gay man and, subsequently, to mental health outcomes (Perales & Todd, 2018). Self-stigma can negatively impact the sense of belonging. When LGBTQIA+ individuals experience high levels of self-stigma, it can prevent them from feeling worthy of belonging to supportive communities, including LGBTQIA+ groups. In contrast, interventions that reduce self-stigma can foster a stronger sense of belonging by helping individuals feel more accepted and valued within their community. Internalized homonegativity, also referred to as self-stigma, has been shown to be indirectly related to depressive symptoms through the sense of belonging to gay groups, connections with gay friends, and the wider community (Davidson, et al., 2017). Therefore, interventions focused on lowering internalized homonegativity in gay men could strengthen their sense of belonging and subsequently reduce depressive symptoms. For Persian queers, internalized homonegativity is often intensified by religious and cultural narratives that equate queerness with immorality or illness. Many individuals face pressure to suppress their identity in order to maintain familial and social standing. Without access to affirming Persian LGBTQIA+ spaces, self-stigma can go unchallenged, deepening feelings of isolation and contributing to mental health struggles such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. It has been proven that there is a link between internalized homonegativity and depression mediated by low levels of belonging across three layers of the gay community (friends, specific gay groups, and the broader community), as well as the general community (Davidson, et al., 2017) (McLaren, Jude, & McLachlan, 2008). Specifically:

A lower sense of belonging to the general community is associated with higher depressive symptoms.

An increased internalized homonegativity is linked to a reduced sense of belonging with gay friends, which in turn is associated with higher depressive symptoms.

A greater internalized homonegativity correlates with a diminished sense of belonging to gay groups; a reduced sense of belonging to gay groups is linked to a lower sense of belonging to the general community, and a lower sense of belonging to the general community is associated with increased depressive symptoms.

For Persian LGBTQIA+ individuals, strengthening ties to Persian queer networks—whether through diasporic LGBTQIA+ organizations or virtual support spaces—can be a powerful way to counteract internalized homonegativity. Given the criminalization and social stigmatization of queer identities in Persian culture, finding alternative models of belonging is crucial for mental health and self-acceptance.

Just as the need to belong influences one’s emotions and thoughts, these emotions and thoughts, in turn, affect an individual’s capacity, opportunities, and motivation to foster belonging. To that end, to enhance a sense of belonging, one might consider:

reframing thoughts about negative social interactions and experiences;

recognizing that feelings of not belonging are universal and occur periodically;

and adjusting the perception of whether the causes of these feelings are internal or external.

For Persian queers, culturally specific interventions that address the intersection of sexuality, culture, and diaspora are essential. Online platforms, advocacy groups, and storytelling initiatives can help shift negative perceptions and foster a sense of belonging that is not contingent on mainstream acceptance.

4.4. Key Quantitative Link

Using the Persian 8-item Internalized Transphobia scale alongside the GHQ-28 depression subscale, internalized stigma shows a strong association with depressive symptoms (ICC = 0.530, p < .001) (Sadeghi, Jamali, & Sheybani, 2024). This empirically indexes how self-devaluation erodes Subjectivity and helps quantify the psychological cost described in this section (

Table 1).

5. Self-Determinism

Self-determination and individual choice are integral to Western perspectives on optimal human development and psychological well-being (Hostetler, 2009). Choice and self-determination have historically played a central role in LGBT lives and communities (D'Emilio, The World Turned: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and Culture, 2002) (D'Emilio & Freedman, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America, Third Edition, 2012). The ‘recent’ history of gay and lesbian communities has been described as an evolution from the fight for self-identification as sexual minorities to a focus on more personalized choices about what kind of sexual minority life to construct (D'Emilio, The World Turned: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and Culture, 2002). In other words, while coming out undeniably carries social and political implications, it is, at its core, an act of individual self-determination that expands and limits the range of potential life opportunities. Identifying as gay does not guarantee inclusion in gay men’s social networks, particularly on dating apps (Bartone, 2018).

Gay men who come from underrepresented racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds, along with those who do not conform to traditional gender norms, frequently encounter barriers to participation in social gatherings and gay-oriented venues, in contrast to their White, middle-class peers (Berube, 2003) (Han, 2007). In light of this, these marginalized groups have created their own welcoming environments, such as the Evolution Project, Fab 5, RT Parties, and the Gay Asian Pacific Islander Men of New York, which serve as vital spaces for connection and community support. Nonetheless, within the queer circles of Persian communities, individuals may face even deeper levels of alienation often compounded by institutional suppression, which can create complex challenges for their visibility and acceptance. Self-determination is a complex concept that can be influenced by various factors—both positive and negative. For example, the pressures of hegemonic masculinity may hinder men from forming meaningful emotional bonds with one another (Nardi, 1999). This social environment can either dampen the motivation to foster connections or compel individuals, particularly sexual and gender minorities, to go above and beyond to fit in with societal norms (Rothbaum, Weisz, & Snyder, 1982). This experience, often overlooked, is referred to as secondary control. It involves efforts to “blend in” and adapt when primary control—defined as human action aimed at aligning the external world with personal goals—proves ineffective. One facet of secondary control is interpretive control, where individuals derive meaning from events beyond their control as a way to accept and adjust to their realities. While this may seem like merely creating the illusion of control, it is, in fact, a resilient strategy that helps one maintain self-esteem and navigate challenges, ultimately pointing the way back toward regaining primary control. However, the degree to which interpretive control offers refuge can vary, particularly in how sexual minorities employ this approach. Those adept at this strategy may find themselves misinterpreting situations at times. Hence, while striving for a positive outlook, their surroundings might continue to present new challenges. In the Persian queer community, self-determination often takes shape through secondary control mechanisms. Unlike their counterparts in Western LGBTQ+ movements who may publicly defy societal norms, Iranian queer individuals often operate within coded social frameworks, utilizing semi-private networks and selective disclosure (Martino & Kjaran, 2018)(Martino & Kjaran, 2018). While these strategies foster survival, they also create a dual identity—one that is publicly compliant yet privately resistant. In severely oppressive environments, employing interpretive control can lead to long-lasting identity splits. Research by Martino & Kjaran (Martino & Kjaran, 2018)(Martino & Kjaran, 2018) highlights how Iranian gay men, who engage in 'masking' behaviors, face psychological distress stemming from their inability to express their identities openly. Although this strategy may facilitate physical survival, it can also usher in feelings of emotional loneliness and diminished self-worth. The interaction between primary and secondary control strategies is evident in the choices facing Persian queer individuals. Some navigate their realities through 'controlled invisibility,' opting for subtle interactions and discreet queer spaces (Martino & Kjaran, 2018)(Martino & Kjaran, 2018), while others push for greater visibility by advocating for LGBTQ+ rights, even at considerable risk. This tension underscores the paradox of self-determination, where the quest for visibility can be both liberating and perilous.

In Western psychological terms, self-determination is often seen as inherently valuable. Yet, within Persian queer communities, personal autonomy can clash with collectivist values centered on family honor and social ties. As noted, gay men in Iran frequently endure coercive measures—ranging from forced marriages to psychiatric interventions—that portray self-determination as a disorder rather than a fundamental aspect of human freedom (Martino & Kjaran, 2018)(Martino & Kjaran, 2018). The intricate relationship between primary and secondary control complicates clear definitions of control and autonomy. Additionally, the way control is nurtured can differ across collectivist cultures, where secondary strategies are often prized. For instance, in Japanese and other Asian societies, aligning personal aspirations with family and societal expectations represents maturity. Conversely, in the American context, bending or sacrificing personal goals to adhere to social pressure is viewed as unthinking compliance or post-hoc justification (Gould, 1999)(Gould, 1999) (Markus, Culture and personality: Brief for an arranged marriage, 2003) (Markus, Culture and personality: Brief for an arranged marriage, 2003) (Markus & Kitayama, Culture and the self: Implications for cogni- tion, emotion, and motivation, 1991) (Markus & Kitayama, Culture and the self: Implications for cogni- tion, emotion, and motivation, 1991) (Markus & Litayama, The Cultural Psychology of Personality, 1998)(Markus & Litayama, The Cultural Psychology of Personality, 1998). This creates a scenario where interpretive control strategies, meant to foster connection with the larger community, might be interpreted in individualistic cultures as deficiencies in personal agency. These views can perpetuate feelings of inadequacy as individuals grapple with the pressure to assert their independence, ultimately impacting their psychological well-being and pursuit of personal objectives (Ryan & Deci, 2000)(Ryan & Deci, 2000). In a survey of Iranian college students, the authors used Self-Determination Theory to link autonomy with mental health. They found that greater autonomy was negatively correlated with depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms and social dysfunction (Sheikholeslami & Arab-Moghaddam, 2010)(Sheikholeslami & Arab-Moghaddam, 2010). In other words, students with more personal autonomy reported better psychological adjustment. This study (by Iranian researchers) demonstrates empirically that feeling “free to decide for oneself” is associated with well-being in Iran, underscoring self-determination’s relevance in the Iranian cultural context. Applying Deci & Ryan’s Self-Determination framework to Iranian Muslims, Gorbani et al. (Ghorbani, Bing, Watson, Davison, & LeBreton, 2003)(Ghorbani, Bing, Watson, Davison, & LeBreton, 2003) explicitly defined autonomy as “the experience that personal activities emerge out of non-coerced internal choices,” for example “I feel like I am free to decide for myself how to live my life.” Their study of mystical religious experiences in Iran uses this definition to link autonomy (and relatedness, competence) to healthy psychological functioning in an Iranian context. By using a Western psychological model in Iran, they show that autonomy as a need operates similarly across cultures. This supports the idea that autonomy (خودمختاری) is a meaningful construct in Iran, not just Western theory, reinforcing self-determination’s universality. In a research on married women (which is another form of minority or ‘second-ranked citizens in Iran) in Mashhad, Zanjani Zadeh Azazi and Amiri Tarshizi critically defined women’s autonomy and measure its social determinants. Using surveys and regression, they found that a woman’s self-concept, private personal space, social-cultural network, economic capital (income), and her husband’s occupational status together explained about 61% of the variance in her autonomy (Zadeh & Tarshizi, 2005)(Zadeh & Tarshizi, 2005). In practical terms, this means Iranian women’s sense of autonomy is strongly shaped by psychological factors (self-concept, privacy) and by sociopolitical factors (networks, income, spouse’s status). That work highlights how cultural and structural conditions in Iran impact personal autonomy, which helps expand the draft’s discussion of the social roots of self-determination in Iranian society. Focusing explicitly on Iranian gay men, Martino and Kjaran (Martino & Kjaran, 2018)(Martino & Kjaran, 2018) analyzes life narratives under repressive law. The authors stress the “politics of recognition” by which gay Iranians tell their own stories. They use interviews and texts to show how gay men actively construct identity in a society that criminalizes their sexuality. They demonstrate that under authoritarian conditions, queer Iranians still claim personal autonomy through self-narration and community bonds. They illustrate a form of self-determination – gay men asserting “who they are” – even when official autonomy is denied. (e.g., the study shows gay Iranians resisting being labeled only as victims, and weighing human-rights claims from the bottom up). Yadegarfard’s thematic analysis on interviews with 23 gay men in Iran about coping with criminalization (Yadegarfard, 2019)(Yadegarfard, 2019) identifies strategies like risk-taking, building chosen families, and notably “developing a new identity.” This “new identity” suggests that gay Iranians actively reshape or re-frame their sense of self under pressure. From a self-determination perspective, this reflects an agentic process: when unable to live openly, individuals assert autonomy by choosing how to define themselves. Thus this study contributes by showing how marginalized Iranians exercise personal autonomy (self-definition and coping) even in hostile contexts.

Key quantitative link

Homosexual participants score significantly higher on the Emotional Inhibition schema than heterosexual peers, quantifying the psychological cost of “controlled invisibility” as a survival strategy—and the autonomy trade-offs you theorize here (Abboud, et al., 2022)(Abboud, et al., 2022) (

Table 1).

Limitations

As a narrative review with secondary synthesis, our inferences are constrained by heterogeneous designs, measures, and sampling frames across primary studies; we therefore avoided meta-analysis. Publication and language biases may remain despite inclusion of English and Persian sources. Indicators often derive from convenience or clinical samples, limiting generalizability. Some constructs (e.g., arrest/harassment) are under-measured and reported with varying operationalization. Because all analyses use published, aggregate data, we could not adjust for unreported confounders. These limitations are typical for work in criminalizing contexts and underscore the need for standardized, safety-first measurement.

Table 1.

Empirical validation of the five belonging anchors based on synthesized, field quantitative results (Projected Synthesis).

Table 1.

Empirical validation of the five belonging anchors based on synthesized, field quantitative results (Projected Synthesis).

| Anchor |

Core Psychological Construct |

Projected Quantitative Metric |

Finding (Contextualized Data) |

Primary Empirical Data Source |

| Subjectivity |

Internalized Stigma & Self-Devaluation |

Intraclass Correlation (ICC) between Internalized Transphobia (IT Scale) and General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) Depression Subscale. |

ICC=0.530 (p<0.001). Highest correlation after the total score, indicating that internalized stigma is a major, measurable driver of depressive symptoms. |

(Sadeghi, Jamali, & Sheybani, 2024)(Sadeghi, Jamali, & Sheybani, 2024) |

| Groundedness |

Familial Rejection & Existential Crisis |

Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation among Transgender Individuals. |

83% reported current suicidal ideation, with a mean score of 12.8±8.8 on the Beck Scale. |

(Taranom Arianmehr & Younes Mohammadi, 2023)(Taranom Arianmehr & Younes Mohammadi, 2023) |

| Reciprocity |

Clandestine Support Network Function |

Odds Ratio (OR) of Peer Support (Friends) on Non-Compliance with social mandates (e.g., COVID-19 lockdown orders). |

OR=1.147 (p<0.001). Peer support hindered compliance, indicating that the network operates as a counter-normative system separate from state/family norms. |

(Paykani, Zimet, Esmaeili, Khajedaluee, & Khajedaluee, 2020)(Paykani, Zimet, Esmaeili, Khajedaluee, & Khajedaluee, 2020) |

| Dynamism |

Structural Stigma & Risk Exposure |

Percentage of SGM arrested by police for identity/expression. |

12.6% of participants reported arrest by police specifically because of their gender identity, expression, or sexual orientation. |

(Iran: Query response on the situation and treatment of the LGBTQI+ community, 2024)(Iran: Query response on the situation and treatment of the LGBTQI+ community, 2024)

|

| Self-Determination |

Secondary Control & Emotional Inhibition |

Mean score differential on the Emotional Inhibition Schema (Relative to Heterosexual Peers). |

Homosexual participants scored significantly higher on the Emotional Inhibition schema, quantifying the psychological cost of "controlled invisibility." |

(Abboud, et al., 2022)(Abboud, et al., 2022) |

Data Availability

Not applicable. The data synthesized and presented in this paper are derived entirely from existing, published, and cited sources in the academic literature. The data is available through the corresponding cited works.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The author declares that there are no financial, personal, or professional conflicts of interest that could influence the impartiality of the research or the reported findings in this paper.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

References

- Abboud, S., Veldhuis, C., Ballout, S., Nadeem, F., Nyhan, K., & Hughes, T. (2022, June 27). Sexual and gender minority health in the Middle East and North Africa Region: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 27(4). [CrossRef]

- Abdi, S. (2017). Navigating the (Im)Perfect Performances of Queer Iranian-American Identity. Denver, CO: University of Denver. From https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1255.

- Afshari, R. (2016). LGBTs in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Human Rights Quarterly, 38(3), 814-834. [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, K. (2020). The Forbidden Tale of LGB in Iran. London, UK: Mehri Publishing House.

- Ahmady, K. (2021). LGBT in Iran: The Homophobic Laws and Social System In Islamic Republic Of Iran. PJAEE, 18(8), 1446-1464.

- Ahmed, S. (2014). The Cultural Politics of Emotion (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press.

- al-Ghazali, I. A. (2023). Revival of Religion's Sciences (Vol. 4). Beirut, Lebanon: Qadeem Press.

- Allen, K. A. (2020). A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health. Frontiers in Psychiatry.

- Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInereney, D., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: A Review of Conceptual Issues, an Integrative Framework, and Directions for Future Research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87-105.

- Assareh, M., Rashedi, V., Ardebili, M. E., Salehian, R., & Shalbafan, M. (2024). Mental health and attitudes toward suicide amongst individuals with gender dysphoria in Iran. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bartone, M. D. (2018). Jack’d, a Mobile Social Networking Application: A Site of Exclusion Within a Site of Inclusion. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(4), 501-523. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497-529.

- Benhorin, S. (2008). A qualitative examination of the ecological systems that promote sexual identity comfort among European American and African American lesbian youths. Chicago, Illinois: DePaul University.

- Berube, A. (2003). How gay stays White and what kind of White it stays. In M. S. Kimmel, & A. L. Ferber, A reader: Privilege (pp. 253–283). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Bouris, A., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Pickard, A., Shiu, C., Loosier, P. S., Dittus, P., . . . Waldmiller, J. M. (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and wellbeing of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31, 273-309. [CrossRef]

- Brewster, M. E., Moradi, B., DeBlaere, C., & Velez, B. L. (2013). Navigating the borderlands: The roles of minority stressors, bicultural self-efficacy, and cognitive flexibility in the mental health of bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 543-556.

- Calvo, V., Cusinato, M., Meneghet, N., & Miscioscia, M. (n.d.). Perceived Social Support Mediates the Negative Impact of Insecure Attachment Orientations on Internalized Homophobia in Gay Men. Journal of Homosexuality, 10(68), 2266-2284. [CrossRef]

- Carter, L. (2020). How Iran's anti-LGBT policies put transgender people at risk. DW, Society. DW. Retrieved January 19, 2025 from https://amp.dw.com/en/how-irans-anti-lgbt-policies-put-transgender-people-at-risk/a-53270136.

- Cochran, B. N., Stewart, A. J., Ginzler, J. A., & Cauce, A. M. (2002). Challenges Faced by Homeless Sexual Minorities: Comparison of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Homeless Adolescents With Their Heterosexual Counterparts. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 773-777.

- Cochran, S. D. (n.d.). Emerging issues in research on lesbians’ and gay men’s mental health: Does sexual orientation really matter? American Psychologist, 56(11), 931–947. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, S. D., Sullivan, J. G., & Mays, V. M. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. L. (2023). Belonging: The Science of Creating Connection and Bridging Divides. W. W. Norton, Incorporated.

- Coie, J. D. (2004). The impact of negative social experiences on the development of antisocial behavior. In Children's Peer Relations: From Development to Intervention (pp. 243–267). American Psychological Association.

- Colcher, R. W. (1982). Counseling the homosexual alcoholic. Journal of Homosexuality, 7(4), 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Collins, T. W., Grineski, S. E., & Morales, D. X. (2017). Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Environmental Injustice: Unequal Carcinogenic Air Pollution Risks in Greater Houston. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(1), 72-92.

- Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and well-being among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1399–1408.

- Davidson, K., McLaren, S., Jenkins, M., Corboy, D., Gibbs, P. M., & Molloy, M. (2017). Internalized Homonegativity, Sense of Belonging, and Depressive Symptoms Among Australian Gay Men. JOURNAL OF HOMOSEXUALITY, 64(4), 450-465.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self- determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

- D'Emilio, J. (2002). The World Turned: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and Culture. Duke University Press.

- D'Emilio, J., & Freedman, E. B. (2012). Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America, Third Edition. University of Chicago Press.

- Denton, F. N., Rostosky, S. S., & Danner, F. (2014). Stigma-related stressors, coping self-efficacy, and physical health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61, 383-391.

- Diamond, G. M., Diamond, G. S., Levy, S., Closs, C., Ladipo, T., & Siqueland, L. (2013). Attachment-based family therapy for suicidal lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: A treatment development study and open trial with preliminary findings. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(S), 91-100.

- Douglass, R. P., & Conlin, S. E. (2020). Minority stress among LGB people: Investigating relations among distal and proximal stressors. Current Psychology, 41, 3730-3740.

- Douglass, R. P., Conlin, S. E., & Duffy, R. D. (2020). Beyond Happiness: Minority Stress and Life Meaning Among LGB Individuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(11), 1-16.

- Elliot, A. J., Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application. Guilford Publications.

- Fassinger, R. E., & Miller, B. A. (1997). Validation of an Inclusive Model of Sexual Minority Identity Formation on a Sample of Gay Men. Journal of Homosexuality, 32(2), 53-78.

- Feinstein, B. A., Goldfried, M. R., & Davila, J. (2012). The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 917-927.

- Flores, D., Jr, R. M., Arscott, J., & Barroso, J. (2017). Obtaining Waivers of Parental Consent: A Strategy Endorsed by Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Adolescent Males for Health Prevention Research. Nursing Outlook, 66(2), 138-148. [CrossRef]

- Flowerday, T., & Shaughnessy, M. (2005). An interview with Dennis McInerney. Educational Psychology Review, 17, 83-97.

- Foucault, M. (1984). Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias. Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, 5, 46-49.

- Gates, G. J. (2016, December 14). Life Evaluations of LGBT Americans Decline After Election. Gallup News. From https://news.gallup.com/poll/199439/lgbt-status-party-wed-mid.aspx?g_source=position1&g_medium=related&g_campaign=tiles.

- Ghorbani, N., Bing, M. N., Watson, P. J., Davison, H. K., & LeBreton, D. L. (2003). Individualist and collectivist values: evidence of compatibility in Iran and the United States. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 431-447. [CrossRef]

- Gilman, S. E., Cochran, S. D., Mays, V. M., Hughes, M., Ostrow, D., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 933–939.

- Gould, S. J. (1999). A critique of Heckhausen and Schulz's (1995) life-span theory of control from a cross-cultural perspective. Psychological Review, 106(3), 597–604.

- Guitoo, A. (2021). Artikel: "Are you gay or do you do gay?" : subjectivities in "gay" stories on the Persian sexblog shahvani.com. Asiatische Studien, 75(3), 881-899. [CrossRef]

- HAGERTY, B. M., & PATUSKY, K. (1995). Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research, 44(1), 9-13.

- Hall, W. J. (2018). Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors for Depression Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Youth: A Systematic Review. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(3), 263-316.

- Hamedani, A. (20). The gay people pushed to change their gender. BBC Persian. BBC. Retrieved January 19, 2025 from https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29832690.amp.