Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

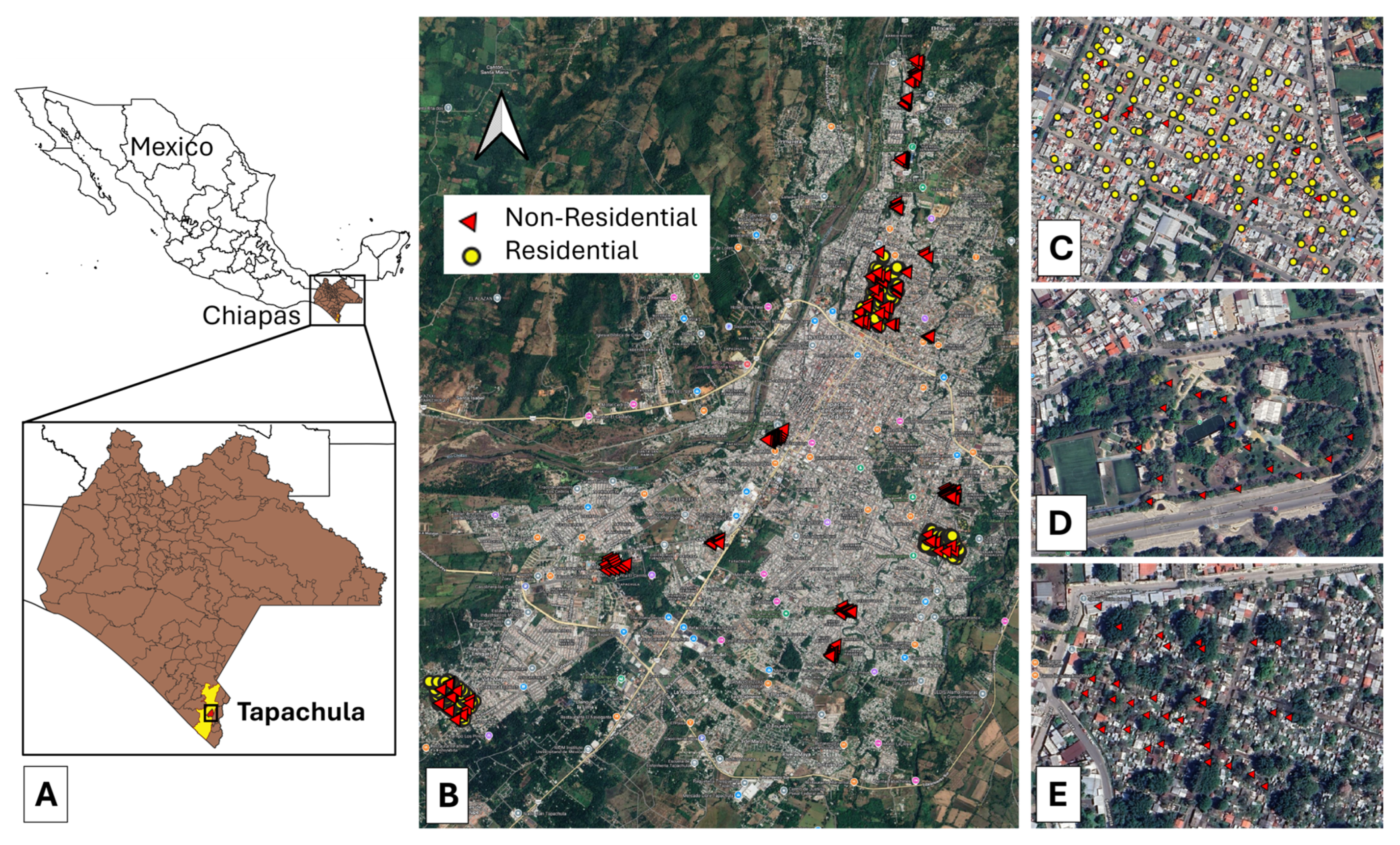

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Egg Collection

2.3. Egg Counts and Aedes Identification

2.4. Data Analysis

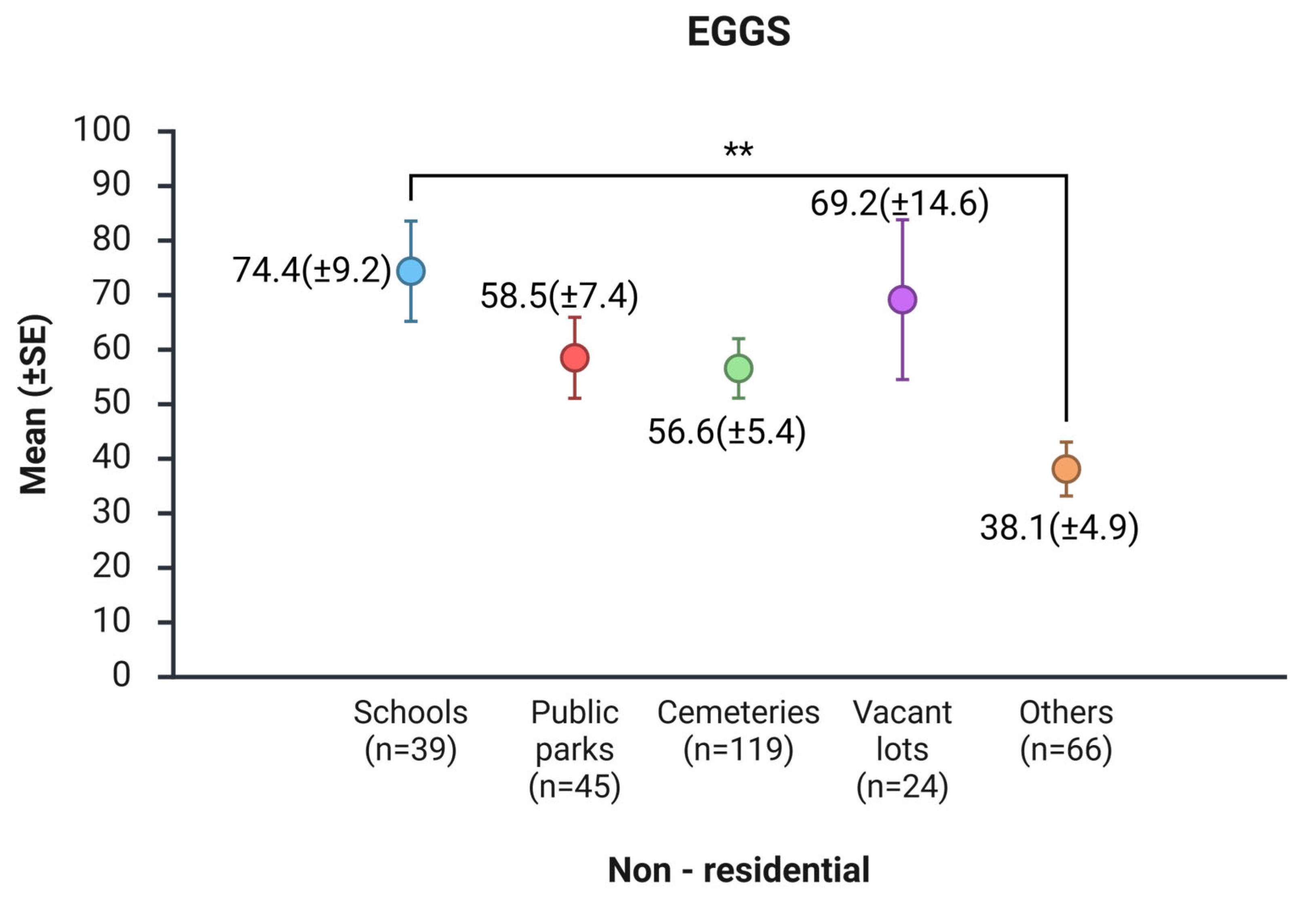

3. Results

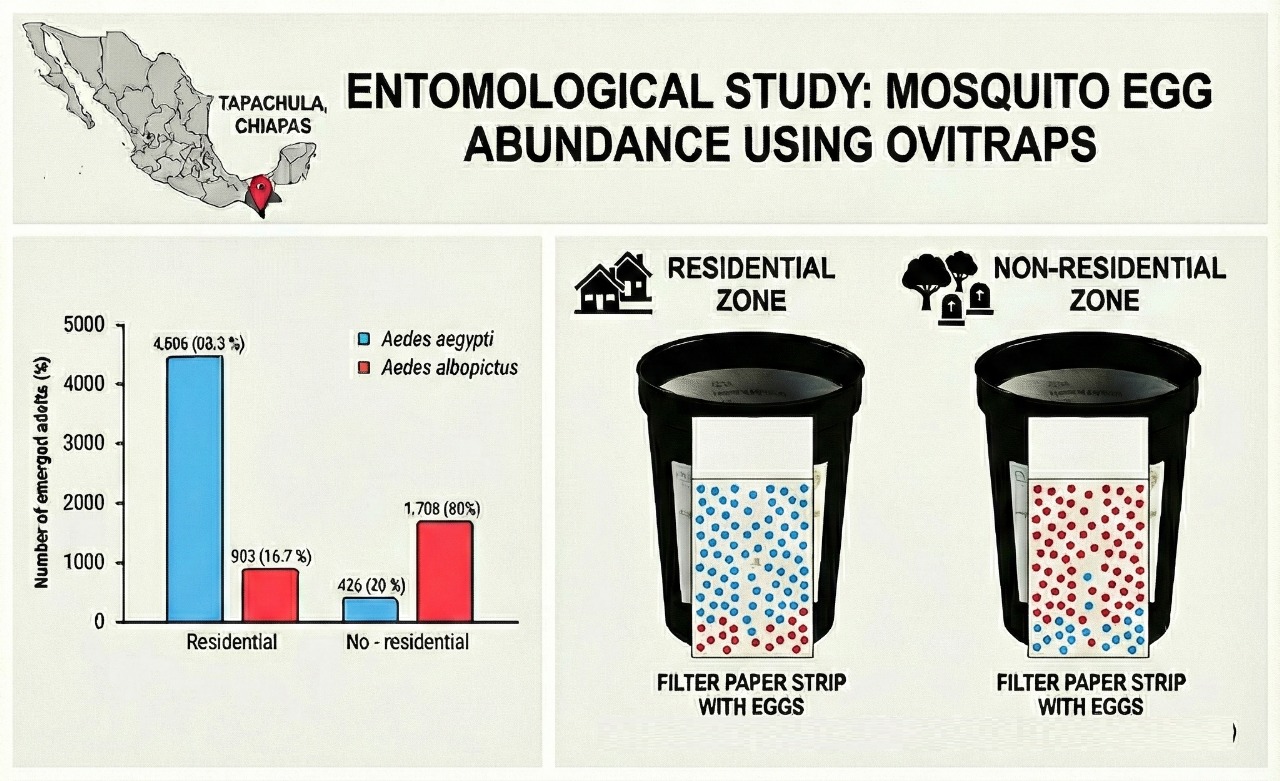

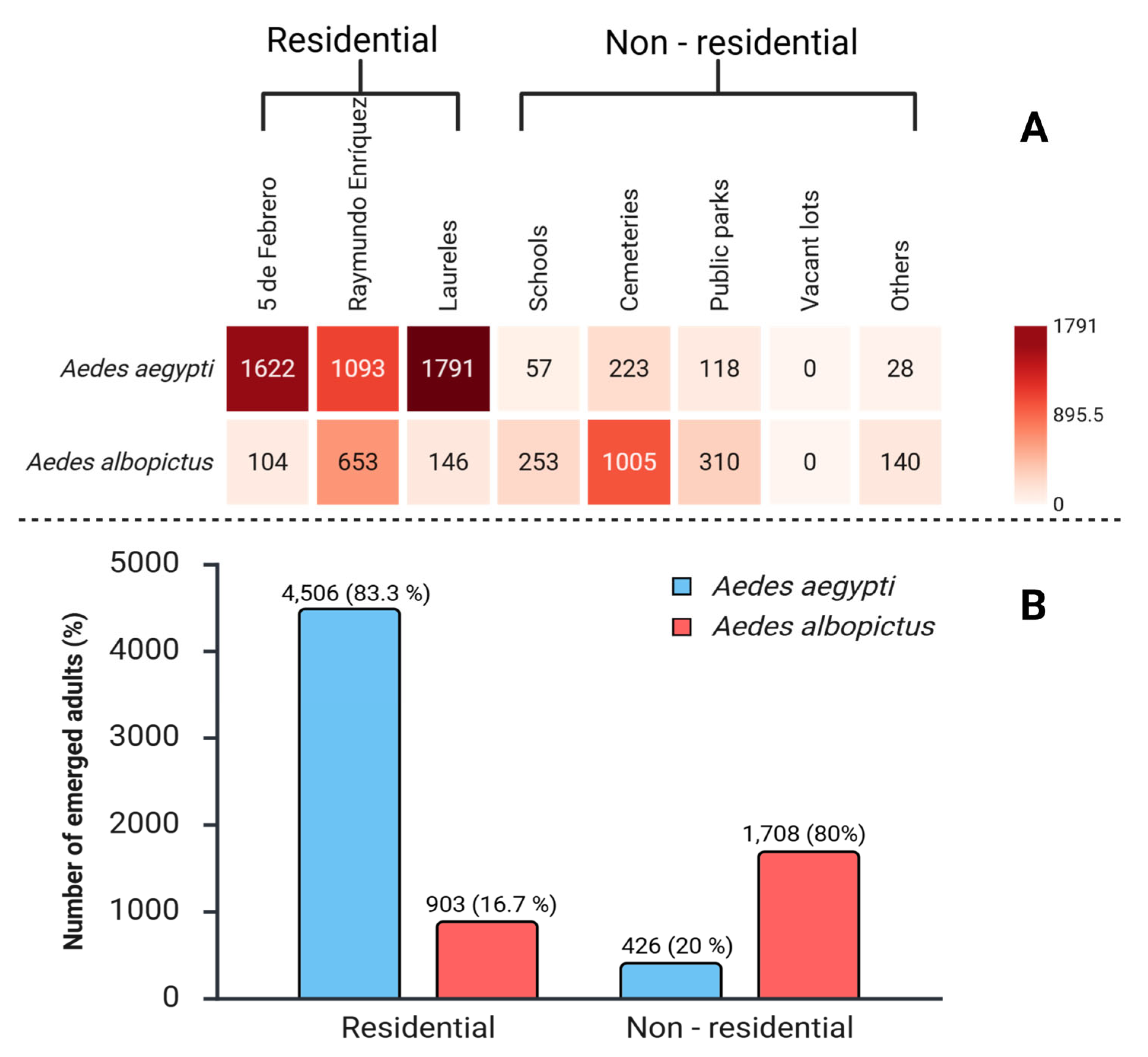

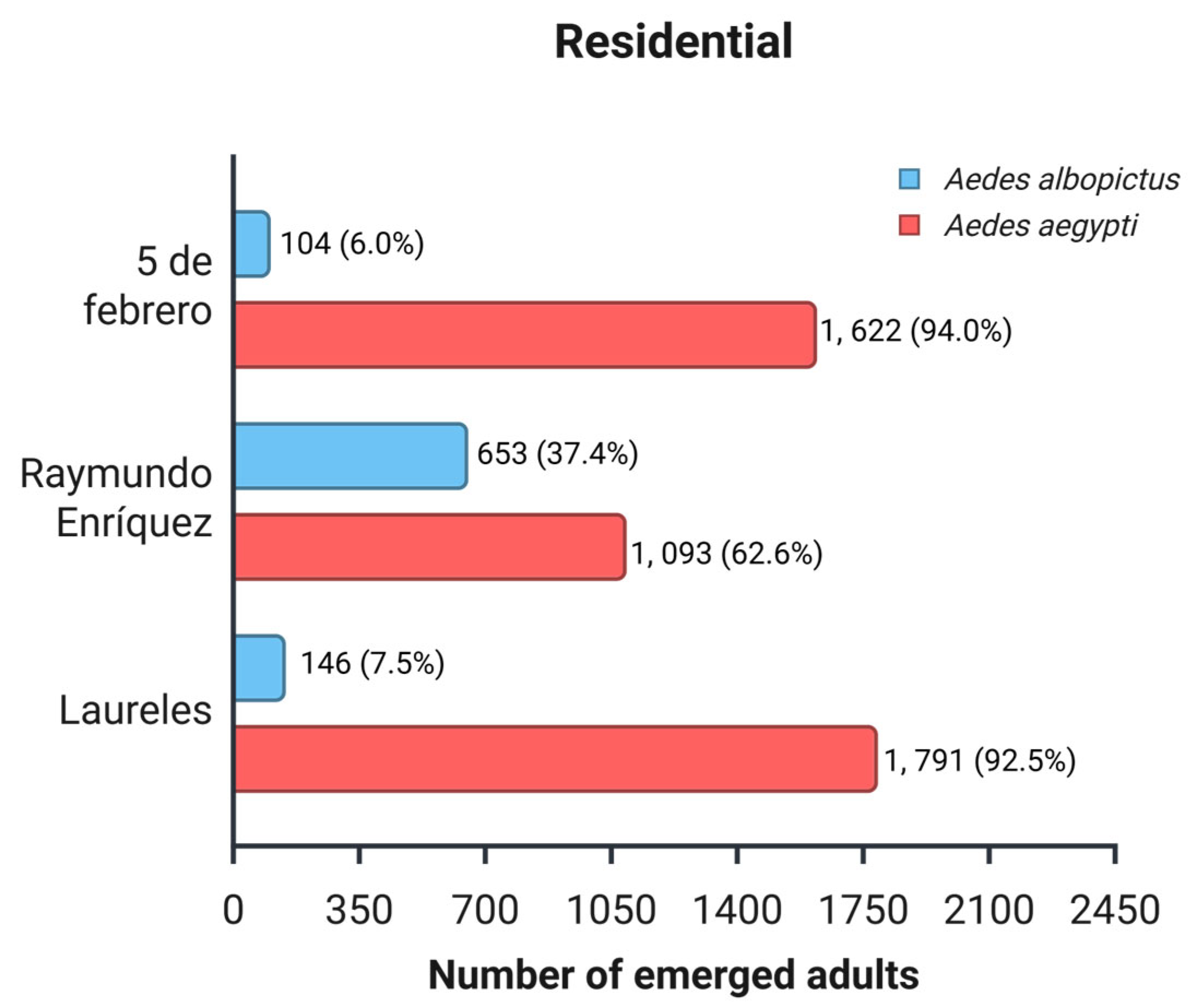

3.1. Frequency of Emerged Species in Residential Sites

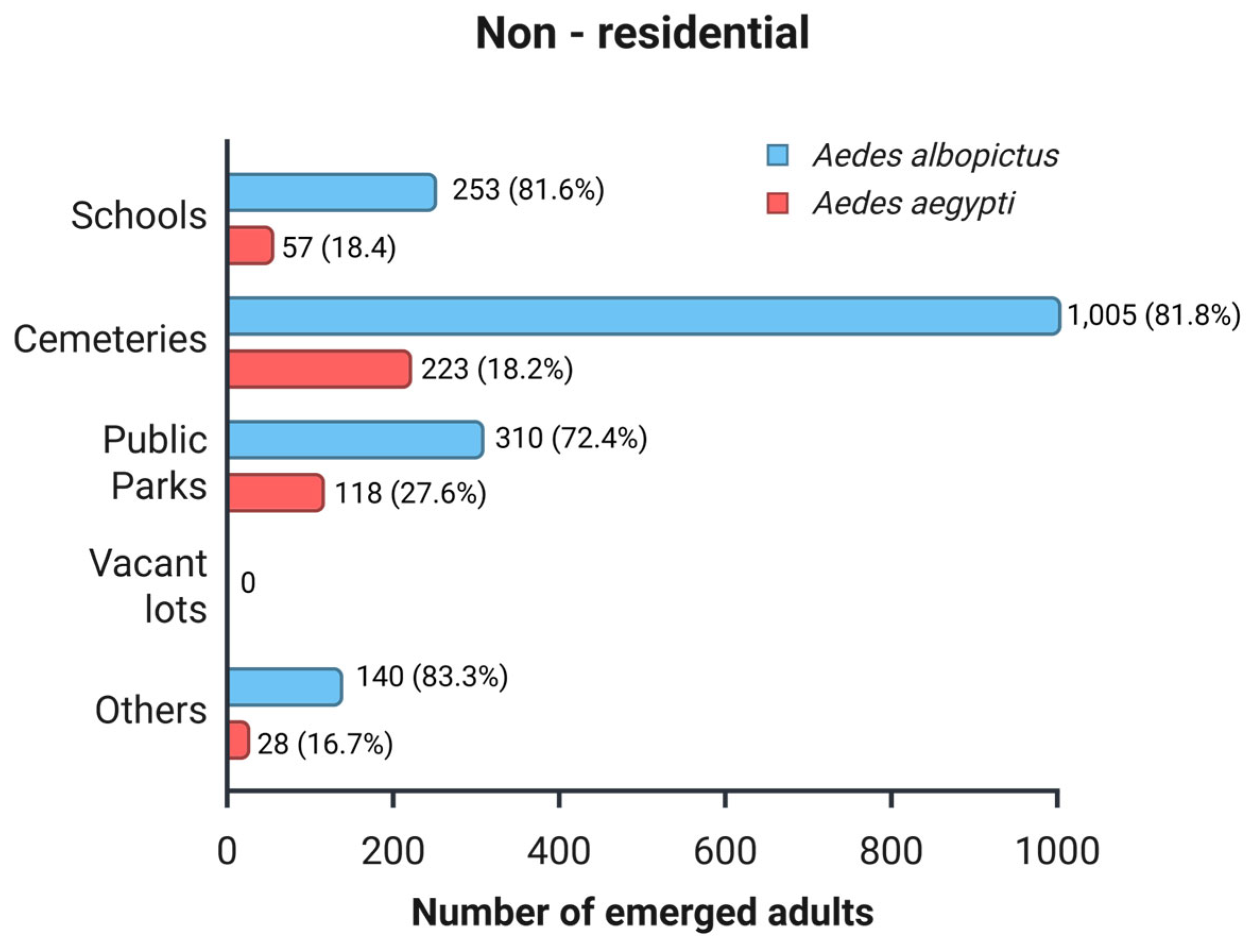

3.2. Frequency of Emerged Species in Non-Residential Areas

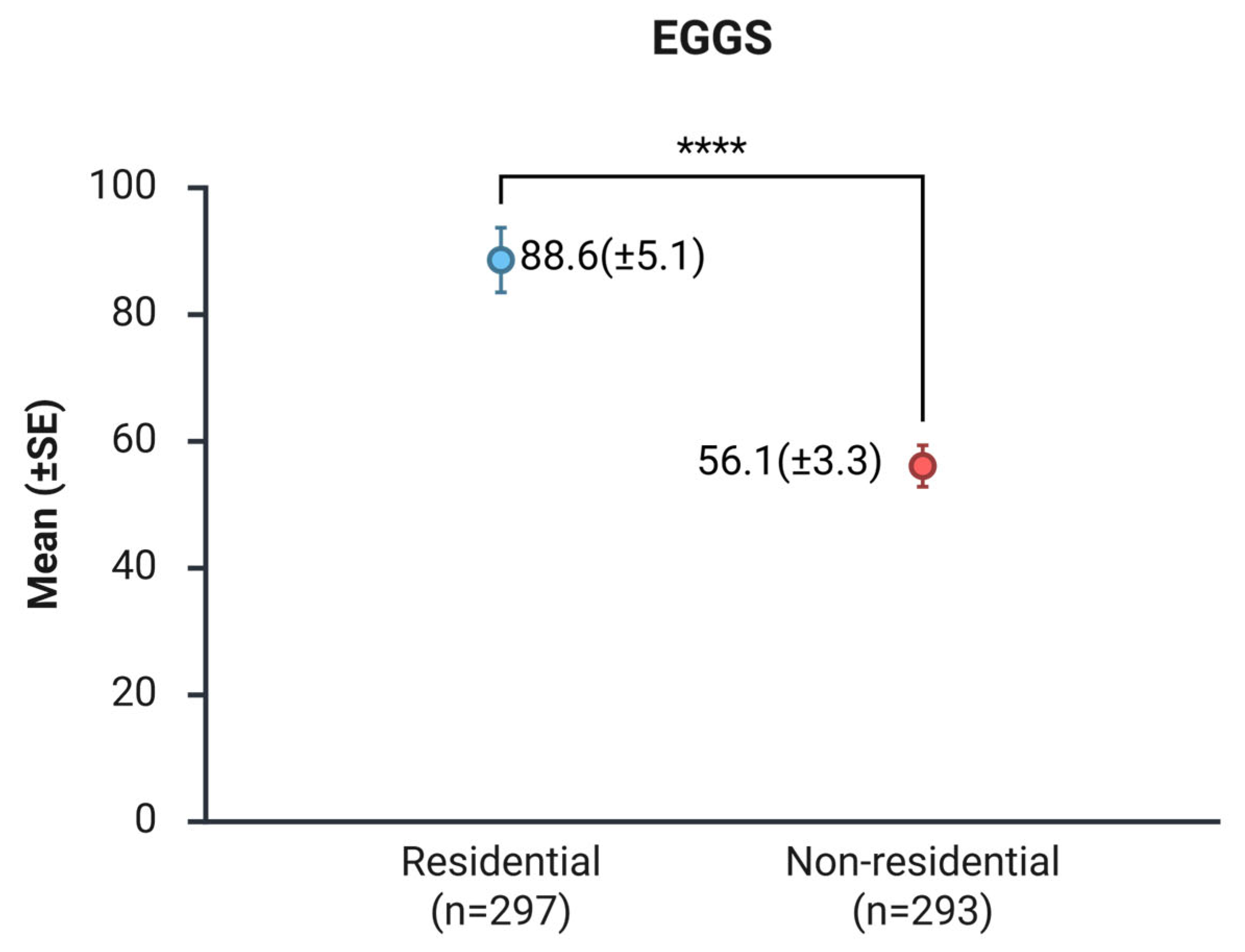

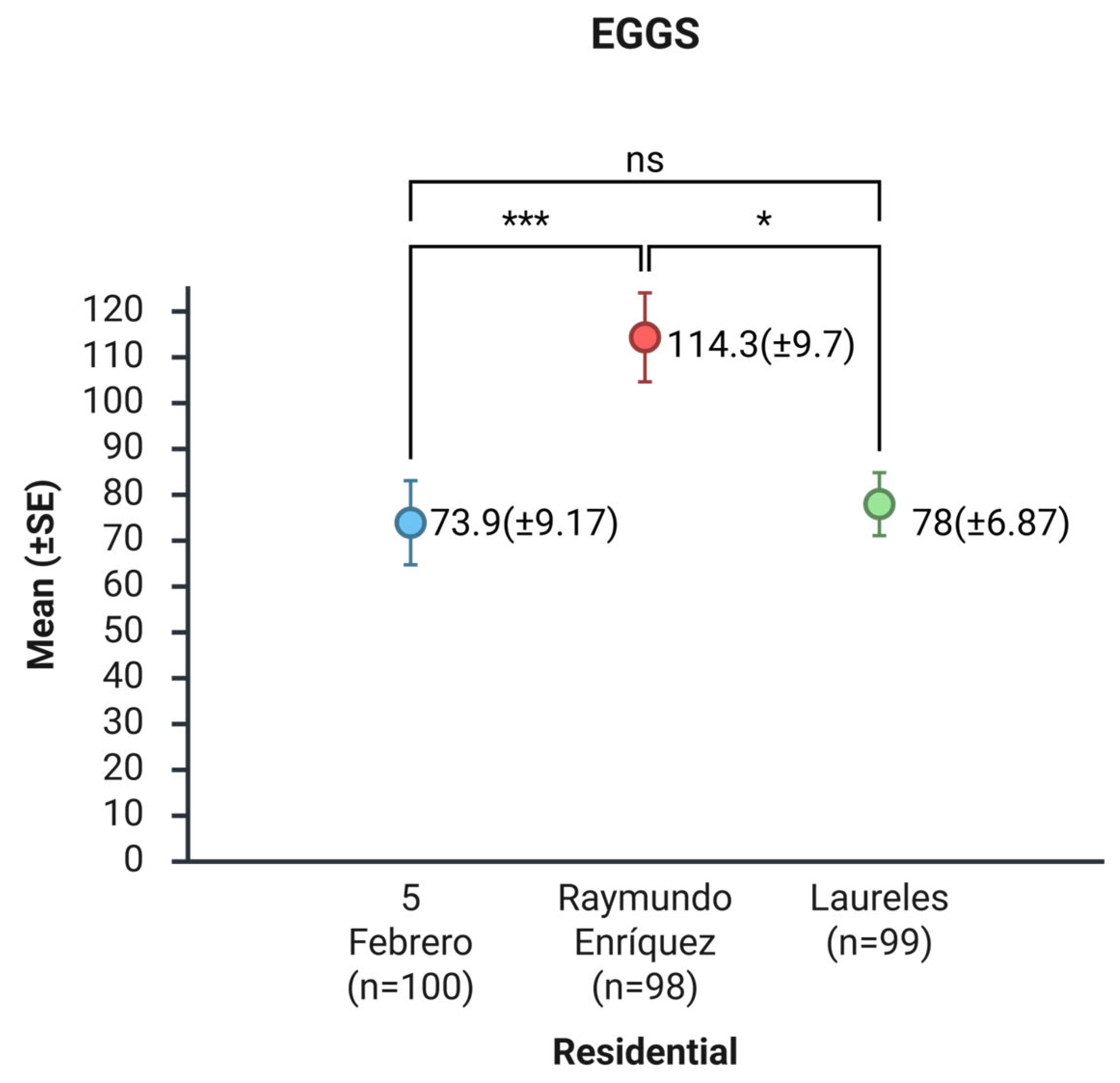

3.3. Vector Burden by Residential and Non-Residential Areas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRISP | Centro Regional de Investigación en Salud Pública |

| INSP | Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública |

References

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud, «Dengue: datos y análisis». Acceded: 7 de diciembre de 2025. [En línea]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/arbo-portal/dengue-datos-analisis.

- Secretaría de Salud, «Panorama Epidemiológico de Dengue 2024», gob.mx. Acceded: 7 de diciembre de 2025. [En línea]. Disponible en: http://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/panorama-epidemiologico-de-dengue-2024.

- L. P. Campbell, C. Luther, D. Moo-Llanes, J. M. Ramsey, R. Danis-Lozano, y A. T. Peterson, «Climate change influences on global distributions of dengue and chikungunya virus vectors», Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci., vol. 370, n.o 1665, p. 20140135, abr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. R. Bowman, S. Donegan, y P. J. McCall, «Is Dengue Vector Control Deficient in Effectiveness or Evidence?: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis», PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 10, n.o 3, p. e0004551, mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Saavedra-Rodriguez et al., «Parallel evolution of vgsc mutations at domains IS6, IIS6 and IIIS6 in pyrethroid resistant Aedes aegypti from Mexico», Sci. Rep., vol. 8, n.o 1, p. 6747, abr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Solis-Santoyo et al., «Insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti from Tapachula, Mexico: Spatial variation and response to historical insecticide use», PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 15, n.o 9, p. e0009746, sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Janich et al., «Permethrin Resistance Status and Associated Mechanisms in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) From Chiapas, Mexico», J. Med. Entomol., vol. 58, n.o 2, pp. 739-748, mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Baak-Baak et al., «Human blood as the only source of Aedes aegypti in churches from Merida, Yucatan, Mexico», J. Vector Borne Dis., vol. 55, n.o 1, p. 58, 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I. Fernández-Salas, Biología y control de Aedes aegypti: Manual de operaciones., 2a. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León., 2009.

- J. E. García-Rejón et al., «Mosquito Infestation and Dengue Virus Infection in Aedes aegypti Females in Schools in Mérida, México», Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg., vol. 84, n.o 3, pp. 489-496, mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Morrison et al., «Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) production from non-residential sites in the Amazonian city of Iquitos, Peru», Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol., vol. 100, n.o sup1, pp. 73-86, abr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Baak-Baak et al., «Vacant Lots: Productive Sites for Aedes (Stegomyia ) aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Mérida City, México», J. Med. Entomol., vol. 51, n.o 2, pp. 475-483, mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática., «Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010. Tapachula, Chiapas.», 2010.

- Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, «Estadísticas Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados». Acceded: 3 de diciembre de 2025. [En línea]. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/comar/documentos/estadisticas-comar-2013-2017.

- E. A. Zarate-Nahon et al., «Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes at Nonresidential Sites Might be Related to Transmission of Dengue Virus in Monterrey, Northeastern Mexico», Southwest. Entomol., vol. 38, n.o 3, pp. 465-476, sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- KMZ to KML Converter Online | MyGeodata Cloud». Acceded: 7 de agosto de 2025. [En línea]. Disponible en: https://mygeodata.cloud/converter/kmz-to-kml.

- G. Obra, E. Rebua, A. M. Hila, S. Resilva, R. Lees, y W. Mamai, «Ovitrap Monitoring of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Two Selected Sites in Quezon City, Philippines», Philipp. J. Sci., vol. 151, n.o 5, ago. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Villarreal-Treviño, J. C. Rios Delgado, K. M. Valdez Delgado, J. A. Nettel-Cruz, y F. A. Zumaya Estrada, Manual de procedimientos para la cría de aedinos y anophelinos en condiciones de insectario. In Cría de mosquitos Culicidae y evaluación de insecticidasde uso en salud pública, 1a Edición. Danis Lozano R, Correa Morales F. Eds. Cuernavaca, Morelos, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, 2021.

- R. F. Darsie y R. A. Ward, Identification and geographical distribution of the mosquitoes of North America, north of Mexico. 2005.

- J. H. Zar, Biostatistical Analysis, 5th Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, 2010.

- H. I. Sasmita et al., «Ovitrap surveillance of dengue vector mosquitoes in Bandung City, West Java Province, Indonesia», PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 15, n.o 10, p. e0009896, oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. C. Dos Reis, N. A. Honório, C. T. Codeço, M. D. A. F. M. Magalhães, R. Lourenço-de-Oliveira, y C. Barcellos, «Relevance of differentiating between residential and non-residential premises for surveillance and control of Aedes aegypti in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil», Acta Trop., vol. 114, n.o 1, pp. 37-43, abr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- I. Navarro-Kraul et al., «The Field Assessment of Quiescent Egg Populations of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus during the Dry Season in Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, and Its Potential Impact on Vector Control Strategies», Insects, vol. 15, n.o 10, p. 798, oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Danis-Lozano, M. H. Rodriguez, L. Gonzalez-Ceron, y M. Hernandez-Avila, «Risk factors for Plasmodium vivax infection in the Lacandon forest, southern Mexico», Epidemiol. Infect., vol. 122, n.o 3, pp. 461-469, jun. 1999. [CrossRef]

| Study area | Category | Sampled neighborhoods and categories of non-residential | ovitraps/ site (n) |

Total ovitraps (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential (R) | Neigborhood | 5 de Febrero | 100 | 297 (50) |

| Raymundo Enríquez | 98 | |||

| Laureles | 99 | |||

| Non-residential (NR) | Cemetery | Jardín | 30 | 119 (20) |

| Municipal | 30 | |||

| Indeco | 29 | |||

| Prados | 30 | |||

| Public Park | Los Cerritos | 15 | 45 (7.6) | |

| Indeco | 15 | |||

| Del Café | 15 | |||

| School | Preparatoria 4 | 4 | 39 (6.6) | |

| Teodomiro | 8 | |||

| Fray Matías | 4 | |||

| República de Cuba | 4 | |||

| 5 de febrero | 2 | |||

| Teófilo de Acebo | 6 | |||

| Técnica 3 | 4 | |||

| Raymundo Enríquez | 4 | |||

| Colinas del Rey | 3 | |||

| Vacant lots (1 ovitrap per vacant lots) | 26 | 26 (4.4) | ||

| Car junk lots | 5 de Febrero | 15 | 31 (5.2) | |

| Banorte | 16 | |||

| Mechanical workshop | MS1 | 2 | 29 (4.9) | |

| MS2 | 2 | |||

| MS3 | 2 | |||

| MS4 | 2 | |||

| MS5 | 1 | |||

| MS6 | 1 | |||

| MS7 | 1 | |||

| MS8 | 1 | |||

| MS9 | 1 | |||

| MS10 | 1 | |||

| MS11 | 3 | |||

| MS12 | 1 | |||

| MS14 | 1 | |||

| MS15 | 2 | |||

| MS16 | 2 | |||

| MS17 | 2 | |||

| MS18 | 2 | |||

| MS19 | 1 | |||

| MS20 | 1 | |||

| Car wash | CW1 | 3 | 5 (0.8) | |

| CW2 | 2 | |||

| Tire-repair shop | TRS1 | 2 | 2 (0.3) | |

| Total R | 297 (50) | |||

| Total NR | 293 (50) | |||

| Total R + NR | 593 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).