Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The History and Promise of Phage Therapy

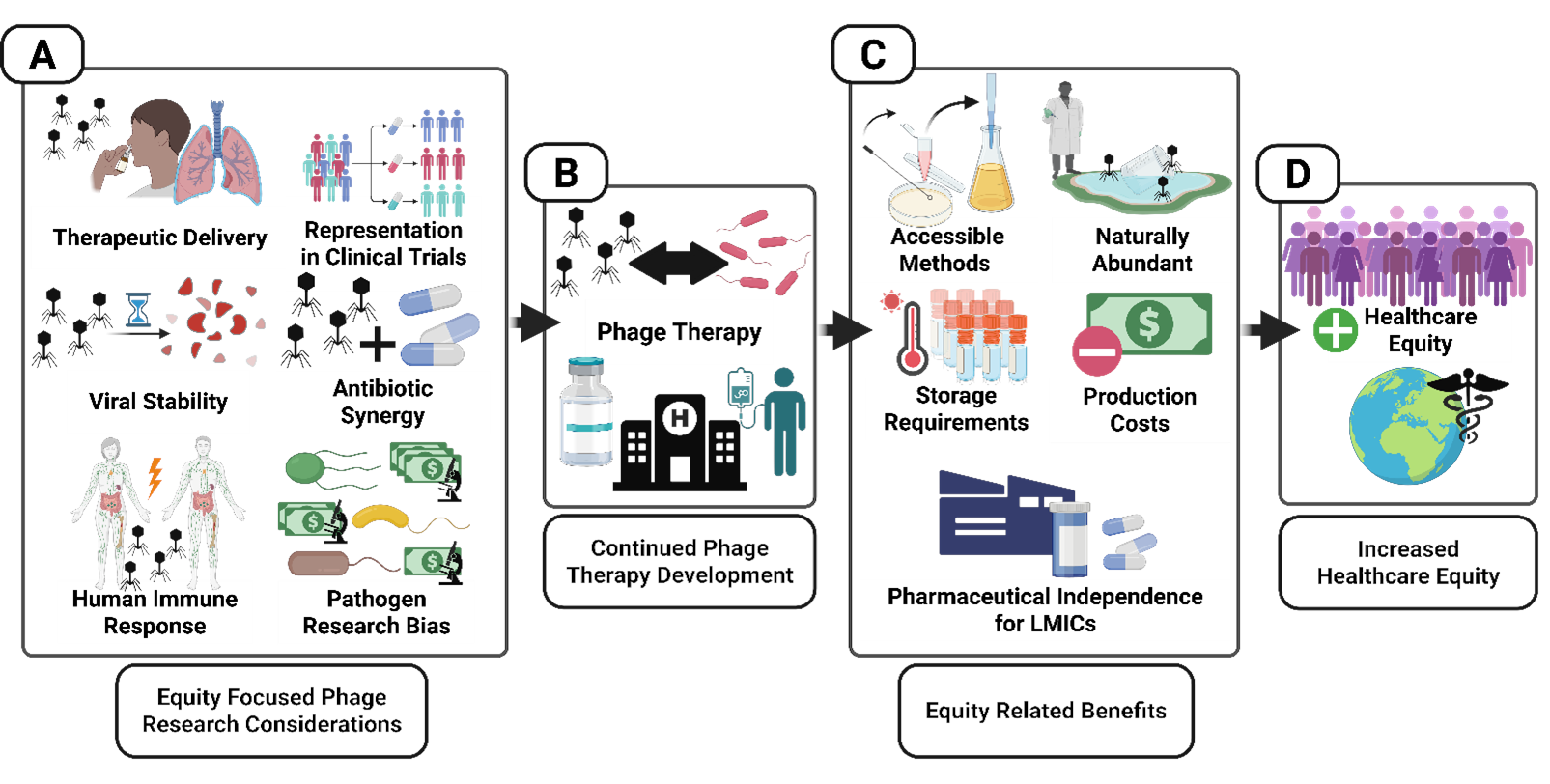

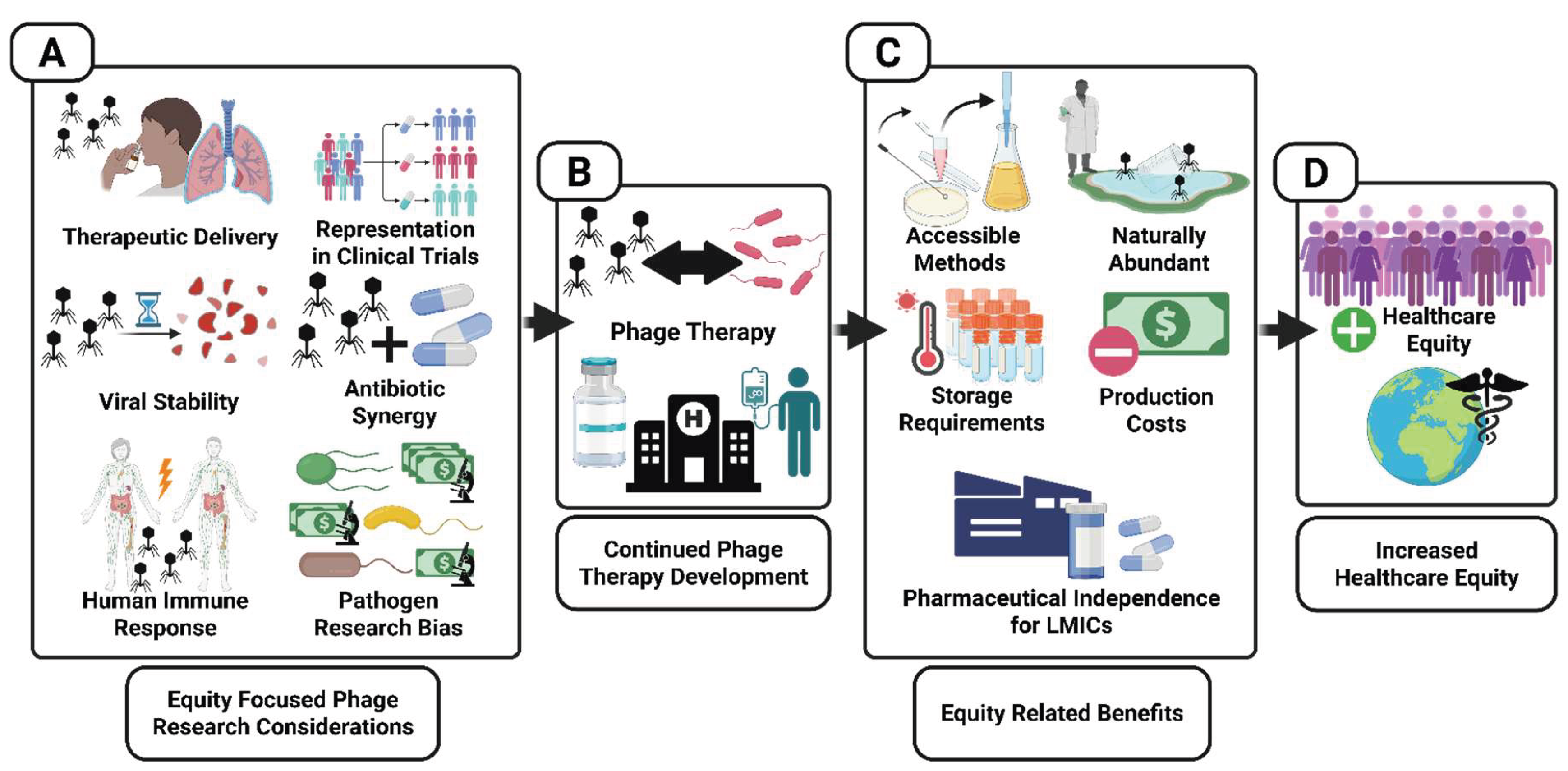

How Phage Therapy Can Advance Healthcare Equity

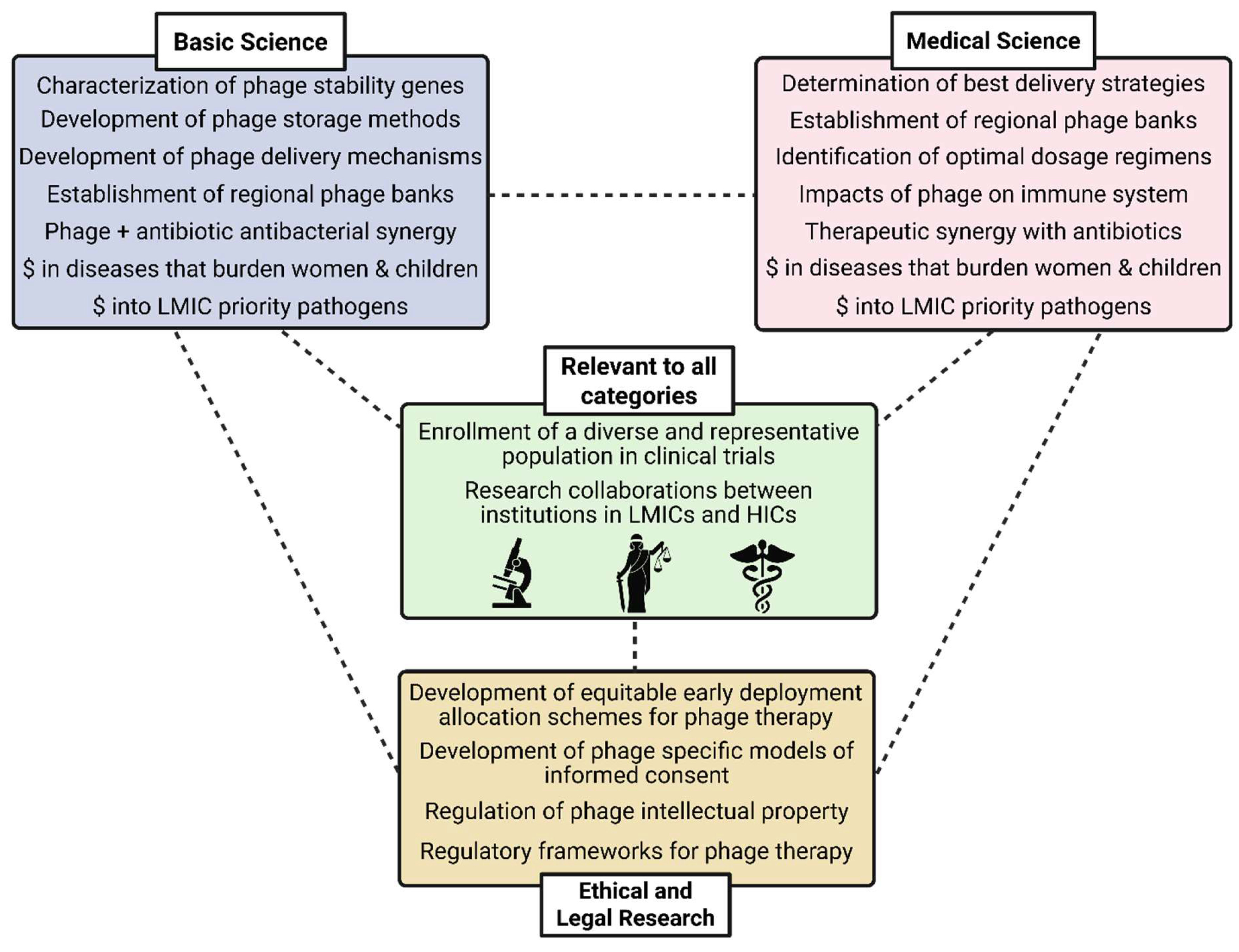

Challenges and Recommendations for Equity-Oriented Phage Therapy Research and Development

Ethical and Regulatory Challenges and Recommendations

Biological Challenges and Recommendations

Conclusions

Summary Points

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 400(10369), 2221–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.F.; Tauxe, R.V.; Hedberg, C.W. The growing burden of foodborne outbreaks due to contaminated fresh produce: risks and opportunities. Epidemiology Infect. 2009, 137, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado-Miranda, JJ; Castillo-Pérez, LJ; Ponce-Hernández, A; Carranza-Álvarez, C. Chapter 19 - Summary of economic losses due to bacterial pathogens in aquaculture industry. In Bacterial Fish Diseases; Dar, GH, Bhat, RA, Qadri, H, Al-Ghamdy, KM, Hakeem, KR, Eds.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, JK; Foster, ed N; Kyriazakis, I; Barrow, P. 1 - The economic cost of bacterial infections. In Advancements and Technologies in Pig and Poultry Bacterial Disease Control; Academic Press, 2021; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D.; Andreev, K.; Dupre, M.E. Major Trends in Population Growth Around the World. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raleigh, V.S. World population and health in transition. BMJ 1999, 319, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Lyon, C.J.; Ying, B.; Hu, T. Climate change, its impact on emerging infectious diseases and new technologies to combat the challenge. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2356143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.E.; Mahmud, A.S.; Miller, I.F.; Rajeev, M.; Rasambainarivo, F.; Rice, B.L.; Takahashi, S.; Tatem, A.J.; Wagner, C.E.; Wang, L.-F.; et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, M.B.; Sack, A.; Aleuy, O.A.; Barbera, C.; Brown, E.; Buelow, H.; Civitello, D.J.; Cohen, J.M.; de Wit, L.A.; Forstchen, M.; et al. A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease. Nature 2024, 629, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luepke, K.H.; Suda, K.J.; Boucher, H.; Russo, R.L.; Bonney, M.W.; Hunt, T.D.; Mohr, J.F. Past, Present, and Future of Antibacterial Economics: Increasing Bacterial Resistance, Limited Antibiotic Pipeline, and Societal Implications. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2017, 37, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieri, M; Kumar, K; Boutin, A. Antibiotic resistance. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2017, 10(4), 369–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M; Vollset, SE; Ikuta, KS; Swetschinski, LR; Gray, AP; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet 2024, 404(10459), 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giubilini, A; Savulescu, J. Moral Responsibility and the Justification of Policies to Preserve Antimicrobial Effectiveness. In Ethics and Drug Resistance: Collective Responsibility for Global Public Health; Jamrozik, Selgelid, M, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; Volume 5, pp. 141–54. [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Matsoso, P.; Pant, S.; Brower, C.; Røttingen, J.-A.; Klugman, K.; Davies, S. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2016, 387, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacteriophages: Biology and Applications; Kutter, E, Sulakvelidze, A, Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2004; p. 528 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Kortright, K.E.; Chan, B.K.; Koff, J.L.; Turner, P.E. Phage Therapy: A Renewed Approach to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, W.C. The strange history of phage therapy. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanishvili, N. Phage Therapy—History from Twort and d’Herelle through soviet experience to current approaches. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 82, 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Le, S.; Zhu, T.; Wu, N. Regulations of phage therapy across the world. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1250848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, A.; Stacey, H.J.; de Soir, S.; Jones, J.D. The Safety and Efficacy of Phage Therapy for Superficial Bacterial Infections: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. Health equity WPRO; World Health Organization International, 2025; Available online: www.who.int.

- A Bhutta, Z.; Sommerfeld, J.; Lassi, Z.S.; A Salam, R.; Das, J.K. Global burden, distribution, and interventions for infectious diseases of poverty. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2014, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R. The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annu. Rev. Public Heal. 2011, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayorinde, A.; Ghosh, I.; Ali, I.; Zahair, I.; Olarewaju, O.; Singh, M.; Meehan, E.; Anjorin, S.S.; Rotheram, S.; Barr, B.; et al. Health inequalities in infectious diseases: a systematic overview of reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, T.E.; Chan, B.K.; De Vos, D.; El-Shibiny, A.; Kang'EThe, E.K.; Makumi, A.; Pirnay, J.-P. The Developing World Urgently Needs Phages to Combat Pathogenic Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loc-Carrillo, C.; Abedon, S.T. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutter, E.; De Vos, D.; Gvasalia, G.; Alavidze, Z.; Gogokhia, L.; Kuhl, S.; Abedon, S.T. Phage Therapy in Clinical Practice: Treatment of Human Infections. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Kajla, P.; Lather, D.; Chaudhary, N.; Dangi, P.; Singh, P.; Pandiselvam, R. Bacteriophages: a potential game changer in food processing industry. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 1325–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Han, G.; Li, Z.; Cun, S.; Hao, B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Bacteriophage therapy in aquaculture: current status and future challenges. Folia Microbiol. 2022, 67, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Anaya, M.C.; Sepulveda, D.R.; Sáenz-Mendoza, A.I.; Rios-Velasco, C.; Zamudio-Flores, P.B.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.H. Phages as biocontrol agents in dairy products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, B.; Jones, J.B.; Iriarte, F.B.; Momol, M.T. Phage Therapy for Plant Disease Control. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loponte, R.; Pagnini, U.; Iovane, G.; Pisanelli, G. Phage Therapy in Veterinary Medicine. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalpando-Aguilar, J.L.; Matos-Pech, G.; López-Rosas, I.; Castelán-Sánchez, H.G.; Alatorre-Cobos, F. Phage Therapy for Crops: Concepts, Experimental and Bioinformatics Approaches to Direct Its Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruciano, D.E.; Bourne, S. Phage as an Antimicrobial Agent: D’herelle’s Heretical Theories and Their Role in the Decline of Phage Prophylaxis in the West. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med Microbiol. 2006, 18, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutateladze, M.; Adamia, R. Bacteriophages as potential new therapeutics to replace or supplement antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmond, G.P.C.; Fineran, P.C. A century of the phage: past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twort, F. AN INVESTIGATION ON THE NATURE OF ULTRA-MICROSCOPIC VIRUSES. Lancet 1915, 186, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Herelle, MF. Sur un microbe invisible antagoniste des bacilles dysentériques. In Comptes rendus de l’Academie des Sciences; 1917; pp. 373–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, K. Bacteriophage Therapy for Bacterial Infections: Rekindling a Memory from the Pre-Antibiotics Era. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2001, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Herelle, F; Smith, GH. The bacteriophage and its behavior; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, W.C. Cholera and plague in India: The bacteriophage inquiry of 1927–1936. J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 1993, 48, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Herelle, F; Malone, RH; Lahiri, MN. Studies on Asiatic cholera. 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, P. The Twort-D'Herelle Phenomenon: A Critical Review and Presentation of a New Conception (Homogamic Theory) Of Bacteriophage Action. J. Infect. Dis. 1928, 42, 263–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. THE BACTERIOPHAGE IN THE TREATMENT OF TYPHOID FEVER. BMJ 1924, 2, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, D; Hicks, W. Observations on the bacteriophage III. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1932, 17, 685. [Google Scholar]

- Krestownikowa, W; Gubin, W. Die Verteilung and die Ausscheidung von Bak-teriophagen im Meerschweinchen-organismus bei subkutaner Applicationsart. J. Microbiol., Patolog. i. Infekzionnich bolesney 1925, 1(3). [Google Scholar]

- Luria, S.E.; Delbrück, M. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 1943, 28, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riding, D. Acute Bacillary Dysentery in Khartoum Province, Sudan, with Special Reference to Bacteriophage Treatment: Bacteriological Investigation. Epidemiology Infect. 1930, 30, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, MD; Bayne-Jones, S. Bacteriophage Therapy: Review of the Principles and Results of the use of Bacteriophage in the Treatment of Infections. JAMA 1934, 103(23), 1769–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, AP; Scribner, EJ. The Bacteriophage: Its Nature and its Theraputic Use. JAMA 1941, 116(20), 2269–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, W.C. The Cold War and Phage Therapy: How Geopolitics Stalled Development of Viruses as Antibacterials. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2024, 11, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed; Geneva, Switzerland, Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pirnay, J.-P.; Djebara, S.; Steurs, G.; Griselain, J.; Cochez, C.; De Soir, S.; Glonti, T.; Spiessens, A.; Berghe, E.V.; Green, S.; et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1434–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.K.; Stanley, G.L.; Kortright, K.E.; Vill, A.C.; Modak, M.; Ott, I.M.; Sun, Y.; Würstle, S.; Grun, C.N.; Kazmierczak, B.I.; et al. Personalized inhaled bacteriophage therapy for treatment of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysowski, J.; Górski. 2019. Ethics of Phage Therapy. In Phage Therapy: A Practical Approach, ed A Górski, R Międzybrodzki, J Borysowski, pp. 379–85. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Pires, D.P.; Meneses, L.; Brandão, A.C.; Azeredo, J. An overview of the current state of phage therapy for the treatment of biofilm-related infections. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 53, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyttebroek, S.; Chen, B.; Onsea, J.; Ruythooren, F.; Debaveye, Y.; Devolder, D.; Spriet, I.; Depypere, M.; Wagemans, J.; Lavigne, R.; et al. Safety and efficacy of phage therapy in difficult-to-treat infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e208–e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.-P.; Verbeken, G.; Ceyssens, P.-J.; Huys, I.; De Vos, D.; Ameloot, C.; Fauconnier, A. The Magistral Phage. Viruses 2018, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitchcock, N.M.; Nunes, D.D.G.; Shiach, J.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Barbosa, J.D.V.; Rodrigues, L.A.P.; Coler, B.S.; Soares, M.B.P.; Badaró, R. Current Clinical Landscape and Global Potential of Bacteriophage Therapy. Viruses 2023, 15, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, P.E.; Azeredo, J.; Buurman, E.T.; Green, S.; Haaber, J.K.; Haggstrom, D.; Carvalho, K.K.d.F.; Kirchhelle, C.; Moreno, M.G.; Pirnay, J.-P.; et al. Addressing the Research and Development Gaps in Modern Phage Therapy. PHAGE 2024, 5, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, TL; Childress, JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 8th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2019; p. 512 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1999; p. 538 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, K.L.; Grace, M. Social Foundations of Health Care Inequality and Treatment Bias. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2016, 42, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Stirbu, I.; Roskam, A.-J.R.; Schaap, M.M.; Menvielle, G.; Leinsalu, M.; Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health in 22 European Countries. New Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickman, S.L.; Himmelstein, D.U.; Woolhandler, S. Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. Lancet 2017, 389, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, M. Health Disparities and Access to Healthcare in Rural vs. Urban Areas. Theory Action 2021, 14, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X; Orom, H; Hay, JL; Waters, EA; Schofield, E; et al. Differences in Rural and Urban Health Information Access and Use. The Journal of Rural Health 2019, 35(3), 405–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, GW; Kantrowitz, E. Socioeconomic Status and Health: The Potential Role of Environmental Risk Exposure. Annual Review of Public Health 2002, 23((Volume 23), 303–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iceland, J.; Wilkes, R. Does Socioeconomic Status Matter? Race, Class, and Residential Segregation. Soc. Probl. 2006, 53, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnato, A.E. Challenges In Understanding And Respecting Patients’ Preferences. Heal. Aff. 2017, 36, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parascandola, M.; Hawkins, J.S.; Danis, M. Patient Autonomy and the Challenge of Clinical Uncertainty. Kennedy Inst. Ethic- J. 2002, 12, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, I.K. Informed consent in clinical practice: Old problems, new challenges. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2024, 54, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulumba, M.; Oga, J.; Koomson, N.; Kara, T.-A.; Cynthia, A.N.; Forman, L. Decolonizing global health: Africa’s pursuit of pharmaceutical sovereignty. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. In U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Huecker, MR; Shreffler, J. Ethical Issues in Academic Medicine. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, C.; Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med. Ethic 2017, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norheim, O.F.; Asada, Y. The ideal of equal health revisited: definitions and measures of inequity in health should be better integrated with theories of distributive justice. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2009, 8, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askitopoulou, H.; Vgontzas, A.N. The relevance of the Hippocratic Oath to the ethical and moral values of contemporary medicine. Part II: interpretation of the Hippocratic Oath—today’s perspective. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.G. Why Human Subjects Research Protection Is Important. Ochsner J. 2020, 20, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, B. Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021, 30(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L. Antimicrobial Resistance and Social Inequalities in Health: Considerations of Justice. In Ethics and Drug Resistance: Collective Responsibility for Global Public Health; Jamrozik, Selgelid, M, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 257–78. [Google Scholar]

- Adebisi, Y.A. Balancing the risks and benefits of antibiotic use in a globalized world: the ethics of antimicrobial resistance. Glob. Heal. 2023, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Mestrovic, T.; Gray, A.; Hayoon, A.G.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Aguilar, G.R.; Weaver, N.D.; Ikuta, K.S.; Chung, E.; E Wool, E.; et al. Global burden associated with 85 pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 868–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emadi, M.; Delavari, S.; Bayati, M. Global socioeconomic inequality in the burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases and injuries: an analysis on global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Heal. 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmon, S.; E Avendano, E.; Nirmala, N.; Chan, C.W.; A Morin, R.; Balaji, S.; McNulty, L.; Argaw, S.A.; Doron, S.; Nadimpalli, M.L. Socioeconomic status and the risk for colonisation or infection with priority bacterial pathogens: a global evidence map. Lancet Microbe 2024, 6, 100993–100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, K.; Corrêa, J.S.; Sringernyuang, L.; Nayiga, S.; Chandler, C.I.R. The social burden of antimicrobial resistance: what is it, how can we measure it, and why does it matter? JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2025, 7, dlae208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D.B. Environmental justice and climate change policies. Bioethics 2022, 36, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, C. Climate justice and the international regime. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurnik, M.; Pajunen, M.; Kiljunen, S. Biotechnological challenges of phage therapy. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.L.; McKerrow, J.H. Why Funding for Neglected Tropical Diseases Should Be a Global Priority. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ke, W.-R.; Chang, R.Y.K.; Chan, H.-K. Long-term Storage Stability of Inhalable Phage Powder Formulations: A Four-Year Study. AAPS J. 2025, 27, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Łodej, N.; Kula, D.; Owczarek, B.; Orwat, F.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Neuberg, J.; Bagińska, N.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Górski, A. Factors determining phage stability/activity: challenges in practical phage application. Expert Rev. Anti-infective Ther. 2019, 17, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wdowiak, M.; Paczesny, J.; Raza, S. Enhancing the Stability of Bacteriophages Using Physical, Chemical, and Nano-Based Approaches: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P. Phages for Phage Therapy: Isolation, Characterization, and Host Range Breadth. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, R.P.; Barker, B.T.; Drammeh, H.; Scott, J.; Lin, J. Isolation and genetic analysis of an environmental bacteriophage: A 10-session laboratory series in molecular virology. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2014, 42, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, D.M.; Sivanathan, V.; Asai, D.J.; Hatfull, G.F. SEA-PHAGES and SEA-GENES: Advancing Virology and Science Education. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2024, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittle, C; Brittain, K; Doore, SM; Dover, J; Bergland Drarvik, SM; et al. Phage Hunting in the High School Classroom: Phage Isolation and Characterization. The American Biology Teacher 2023, 85(8), 440–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.C.; Burnett, S.H.; Carson, S.; Caruso, S.M.; Clase, K.; DeJong, R.J.; Dennehy, J.J.; Denver, D.R.; Dunbar, D.; Elgin, S.C.R.; et al. A Broadly Implementable Research Course in Phage Discovery and Genomics for First-Year Undergraduate Students. mBio 2014, 5, e01051-13–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.A.; Morran, L.T. Advantages of laboratory natural selection in the applied sciences. J. Evol. Biol. 2022, 35, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; A Chen, I. Phage engineering and the evolutionary arms race. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 68, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oromí-Bosch, A.; Antani, J.D.; Turner, P.E. Developing Phage Therapy That Overcomes the Evolution of Bacterial Resistance. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2023, 10, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE pathogens: antimicrobial resistance, epidemiology, clinical impact and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semin, S.; Güldal, D. Globalization of the Pharmaceutical Industry and the Growing Dependency of Developing Countries: The Case of Turkey. Int. J. Heal. Serv. 2008, 38, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, T.; Musila, L.; Muthoni, M.; Nikolich, M.; Nakavuma, J.L.; Clokie, M.R. Phage banks as potential tools to rapidly and cost-effectively manage antimicrobial resistance in the developing world. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 53, 101208–101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resch, G.; Brives, C.; Debarbieux, L.; Hodges, F.E.; Kirchhelle, C.; Laurent, F.; Moineau, S.; Martins, A.F.M.; Rohde, C. Between Centralization and Fragmentation: The Past, Present, and Future of Phage Collections. PHAGE 2024, 5, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCammon, S.; Makarovs, K.; Banducci, S.; Gold, V. Phage therapy and the public: Increasing awareness essential to widespread use. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0285824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Carey, J.; Erwin, P.J.; Tilburt, J.C.; Murad, M.H.; McCormick, J.B. Improving understanding in the research informed consent process: a systematic review of 54 interventions tested in randomized control trials. BMC Med Ethic- 2013, 14, 28–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, J.; Nouri, S.; Fernandez, A.; Sudore, R.L.; Schillinger, D.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Schenker, Y. Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension in Informed Consent for Medical and Surgical Procedures: An Updated Systematic Review. Med Decis. Mak. 2020, 40, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauconnier, A. Phage Therapy Regulation: From Night to Dawn. Viruses 2019, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeken, G.; De Vos, D.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Merabishvili, M.; Zizi, M.; Pirnay, J.-P. European Regulatory Conundrum of Phage Therapy. Futur. Microbiol. 2007, 2, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, D; Verbeken, G; Quintens, J; Pirnay, J-P. Phage Therapy in Europe: Regulatory and Intellectual Property Protection Issues. In Phage Therapy: A Practical Approach; Górski, Międzybrodzki, R, Borysowski, J, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 363–77. [Google Scholar]

- Naureen, Z.; Malacarne, D.; Anpilogov, K.; Dautaj, A.; Camilleri, G.; Cecchin, S.; Bressan, S.; Casadei, A.; Albion, E.; Sorrentino, E.; et al. Comparison between American and European legislation in the therapeutical and alimentary bacteriophage usage. Acta Biomedica Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, e2020023. [Google Scholar]

- Bretaudeau, L.; Tremblais, K.; Aubrit, F.; Meichenin, M.; Arnaud, I. Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Compliance for Phage Therapy Medicinal Products. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anomaly, J. The Future of Phage: Ethical Challenges of Using Phage Therapy to Treat Bacterial Infections. Public Heal. Ethic- 2020, 13, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, E.M.; Cady, K.C.; Hubby, B. Phage Therapy in the Era of Synthetic Biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a023879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, G.O.; Emanuel, E.J.; Wertheimer, A. The Obligation to Participate in Biomedical Research. JAMA 2009, 302, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalbe, N.; Nunes, M.C.; Cutland, C.; Wahl, B.; Reidpath, D. Assessing New York City’s COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout Strategy: A Case for Risk-Informed Distribution. J. Urban Heal. 2024, 101, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Cristiano, A.; Boccia, S. Global Estimates of Lives and Life-Years Saved by COVID-19 Vaccination During 2020-2024. JAMA Heal. Forum 2025, 6, e252223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact Global Health. Smart Decisions: The G-FINDER 2024 Neglected Disease R&D Report; Sydney, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Armenteras, D. Guidelines for healthy global scientific collaborations. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1193–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, D.; Mwansambo, C.; Costello, A.; Khan, A. Academic partnerships between rich and poor countries. Lancet 2008, 371, 1055–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, O.H. Inequality of Research Funding between Different Countries and Regions is a Serious Problem for Global Science. Function 2021, 2, zqab060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, H.J.; De Soir, S.; Jones, J.D. The Safety and Efficacy of Phage Therapy: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Safety Trials. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Van Belleghem, J.D.; de Vries, C.R.; Burgener, E.; Chen, Q.; Manasherob, R.; Aronson, J.R.; Amanatullah, D.F.; Tamma, P.D.; Suh, G.A. The Safety and Toxicity of Phage Therapy: A Review of Animal and Clinical Studies. Viruses 2021, 13, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, T.; Salabarria, A.-C.; Edwards, R.A.; Roach, D.R. Standardized bacteriophage purification for personalized phage therapy. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 2867–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Würstle, S.; Lee, A.; Kortright, K.E.; Winzig, F.; An, W.; Stanley, G.L.; Rajagopalan, G.; Harris, Z.; Sun, Y.; Hu, B.; et al. Optimized preparation pipeline for emergency phage therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa at Yale University. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, H.W.; Smith, L.; Berwald, L.G. The preservation of mycobacteriophages by means of freeze drying. 1974, 109, 561–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessau, M.; Goldhill, D.; McBride, R.L.; Turner, P.E.; Modis, Y. Selective Pressure Causes an RNA Virus to Trade Reproductive Fitness for Increased Structural and Thermal Stability of a Viral Enzyme. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1003102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kering, K.K.; Zhang, X.; Nyaruaba, R.; Yu, J.; Wei, H. Application of Adaptive Evolution to Improve the Stability of Bacteriophages during Storage. Viruses 2020, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitragotri, S. Immunization without needles. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung Chang, RY; Morales, S; Okamoto, Y; Chan, H-K. Topical application of bacteriophages for treatment of wound infections. Transl Res. 2020, 220, 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doub, J.B.; Johnson, A.J.; Nandi, S.; Ng, V.; Manson, T.; Lee, M.; Chan, B. Experience Using Adjuvant Bacteriophage Therapy for the Treatment of 10 Recalcitrant Periprosthetic Joint Infections: A Case Series. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, e1463–e1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, AO; Abedi, AA; Ferry, T; Citak, M. Current Applications and the Future of Phage Therapy for Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025, 14(6), 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, I.; Kahan-Hanum, M.; Buchstab, N.; Zelcbuch, L.; Navok, S.; Sherman, I.; Nicenboim, J.; Axelrod, T.; Berko-Ashur, D.; Olshina, M.; et al. Phage therapy with nebulized cocktail BX004-A for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis: a randomized first-in-human trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, T.; Luscher, A.; Falconnet, L.; Resch, G.; McBride, R.; Mai, Q.-A.; Simonin, J.L.; Chanson, M.; Maco, B.; Galiotto, R.; et al. Personalized aerosolised bacteriophage treatment of a chronic lung infection due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Garlena, R.A.; Russell, D.A.; Ford, K.; Harris, K.; Gilmour, K.C.; Soothill, J.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Schooley, R.T.; et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S.; Courtwright, A.M.; Koval, C.; Lehman, S.M.; Morales, S.; Furr, C.L.; Rosas, F.; Brownstein, M.J.; Fackler, J.R.; Sisson, B.M.; et al. Early clinical experience of bacteriophage therapy in 3 lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant 2019, 19, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, K. Phage therapy: What factors shape phage pharmacokinetics and bioavailability? Systematic and critical review. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 2000–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.L.; Semersky, Z.; Feinn, R.; Huang, P.; E Turner, P.; Chan, B.K.; Koff, J.L.; Murray, T.S. Particle size distribution of viable nebulized bacteriophage for the treatment of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Respir. Med. Res. 2024, 86, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, P.; Smithyman, A. Safety and efficacy of phage therapy via the intravenous route. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L. The Burden and Etiology of Diarrheal Illness in Developing Countries. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2017, 64, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, B.; Domingo-Calap, P. Phage Therapy in Gastrointestinal Diseases. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerwen, O.T.; Muzny, C.A.; Marrazzo, J.M. Sexually transmitted infections and female reproductive health. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.S.; Unemo, M. Antimicrobial treatment and resistance in sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, K.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Morozova, V.; Letkiewicz, S.; Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Rękas, J.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Górski, A. Potential for Phages in the Treatment of Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kadri, H.M.; El-Metwally, A.A.; Al Sudairy, A.A.; Al-Dahash, R.A.; Al Khateeb, B.F.; Al Johani, S.M. Antimicrobial resistance among pregnant women with urinary tract infections is on rise: Findings from meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Infect. Public Heal. 2024, 17, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.A.; Mager, N.A.D. Women’s involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications. Pharm. Pr. (Internet) 2016, 14, 708–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).