1. Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) belongs to the mosquito-borne aphavirus genus. It was first isolated and identified in Tanzania in 1952 and has once again become a key pathogen threatening global public health in nearly two decades [

1,

2]. The virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Infection can cause acute febrile illness with typical clinical features that include high fever, severe polyarthritis and rash [

3]. Notably, up to 60 percent of patients develop persistent, disabling joint pain that lasts for months to years. Although CHIKV infection has a low fatality rate, its periodic epidemics impose a substantial socioeconomic burden globally-driven by such factors as workforce loss, increased pressure on healthcare systems, and chronic sequelae, all against the backdrop of a growing aging population and rising prevalence of comorbidities [

4].

CHIKV underwent an unprecedented resurgence during 2024-2025 [

4]. This was amply documented by the World Health Organization (WHO) which received reports of over 1.6 million suspected cases, including China’s largest local outbreak with more than 160,000 laboratory-confirmed cases. By September 2025, a total of 2,197 suspected cases and 108 laboratory-confirmed cases of CHIKV infection had been reported across Africa. By October 3, 2025, a total of 56,456 CHIKV infected cases, including 40 deaths, had also been reported in four European countries and regions, including France, Italy, Reunion and Mayotte. CHIKV prevalence in Asia is primarily concentrated in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, and the Western Pacific subregion of East Asia [

5]. Over the past two years, CHIKV case numbers have increased in Pakistan, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. By September 27, 2025, Guangdong Province in China had reported more than 16,000 cases of local CHIKV transmission, all laboratory-confirmed, marking the largest local Chikungunya fever outbreak in China’s history. By November 15, 48 new local cases had been reported within the province. CHIKV cases in Guangdong province have now been reported in 21 cities, mainly concentrated in Foshan (10,040), Jiangmen (5,223), Guangzhou (590), Shenzhen (140), Zhanjiang (112), Zhuhai (60) and Zhongshan (54). Among all reported cases, the group of young adults aged 18-45 years accounted for the highest proportion [

6].

2. Virology and Pathogenic Mechanisms of CHIKV

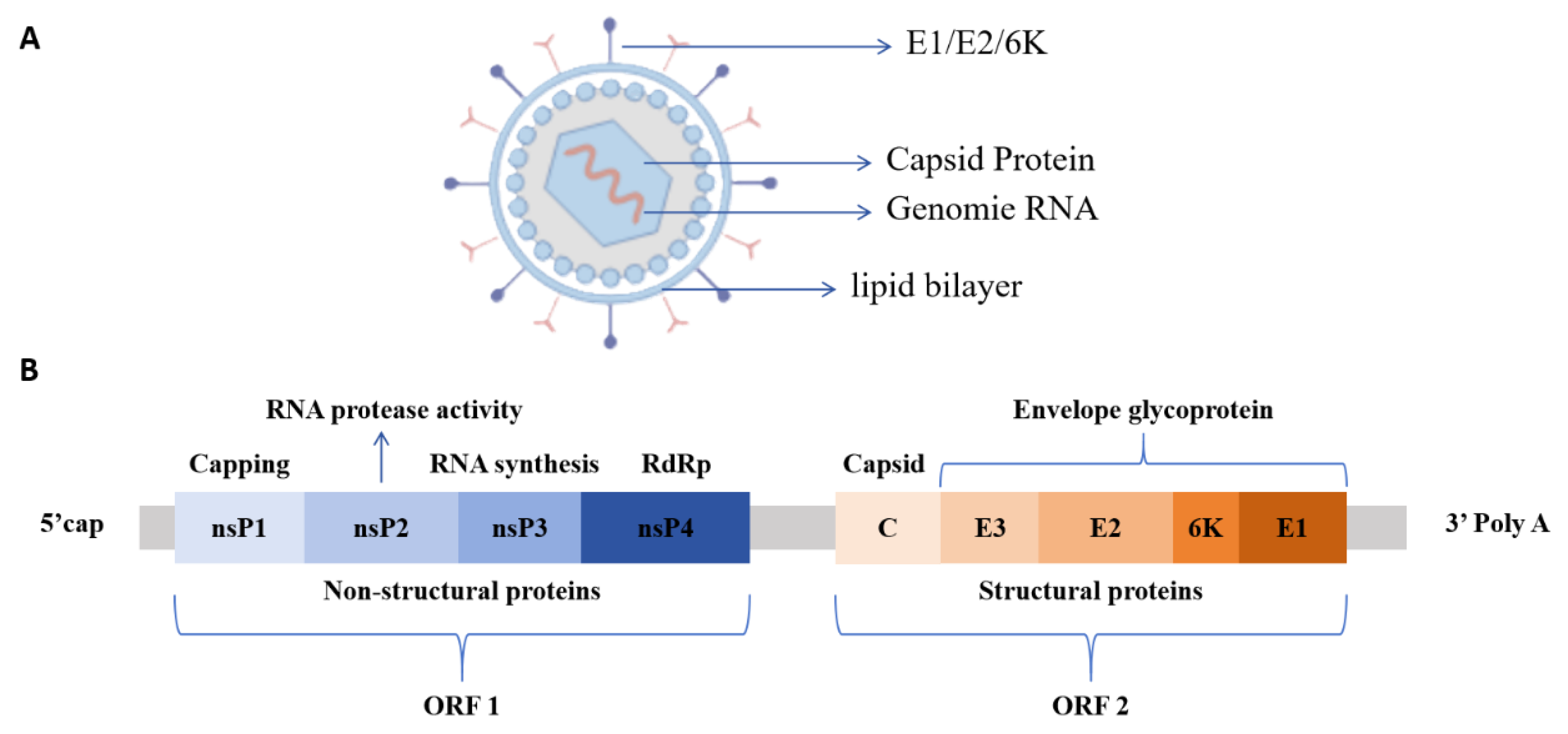

2.1. Genome, Protein Structure and Function of CHIKV

CHIKV particles are spherical with a diameter of approximately 60-70 nm. They consist of a lipid envelope and a nucleocapsid core composed of single-stranded positive-sense RNA and capsid proteins with only one serotype [

7]. The viral genome is about 11.8 kb in length, and the coding region contains two open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1 and ORF2. ORF1, which is located at the 5’ end of the genome, constitutes two-thirds of the total length and encodes four non-structural proteins (nsP), nsP1 to nsP4, in sequence. ORF2 at the 3’ end encodes five structural proteins, including nucleocapsid protein (C), envelope glycoproteins E1, E2, E3, and 6K protein (

Figure 1) [

8,

9].

CHIKV nsPs are key molecules that mediate virus-host cell interactions and regulate pathogenic mechanisms, each protein exhibiting highly specific functions [

10]. nsP1 possesses both N7-guanine methyltransferase (MTase) and guanylate transferase (GTase) activities which catalyze the formation of the 5’ cap structure of nascent viral RNA and are critical for maintaining the stability of viral RNA [

11]. Additionally, the palmitoylation of nsP1 enables it to target cholesterol-rich microdomains on the host cell membrane, thereby providing key sites for the assembly of viral replication complexes [

12]. The nsP2 is the largest non-structural protein encoded by the alphavirus genome. It features an RNA-specific helicase domain at its N-terminus and a cysteine protease domain at its C-terminus. This protease cleaves the viral polyprotein precursor into functional replicase components (nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, nsP4), representing a key step in the progression of the viral replication cycle [

13]. However, the specific function of a molecule’s methyltransferase domain remains to be verified. The nsP3 protein has a modular domain structure. The N-terminus, which exhibits ADP-ribose hydrolase (MAR hydrolase) and phosphatase activities, participates in viral replication by regulating nucleic acid metabolism [

14]. The C-terminal contains a hypervariable domain (HVD) that binds to multiple signaling molecules in the host cell, mediates virus-host interactions, and regulates host cell physiological functions to support viral replication [

15]. It also contains the alphavirus-unique domain (AUD) that plays an indispensable role in viral genome replication and transcription. The nsP4 is the core catalytic subunit for viral RNA replication. Its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain efficiently catalyzes viral RNA synthesis and is a key enzyme for viral genome replication and subgenomic RNA transcription, playing a central regulatory role in the viral replication process [

16,

17]. CHIKV structural proteins play distinct roles in viral assembly and infection. The C protein, a core component of assembly, contains an N-terminal RNA-binding domain that facilitates specific binding between viral genome and C protein, thereby ensuring RNA capping and nucleocapsid formation [

18]. The C-terminal contains a protease domain which promotes viral release through interactions with the E2 protein. The E1 protein mediates fusion between viral envelope and host cell membrane. The E2 protein mediates specific interactions between the virus and host cell receptors, participates in the entire process of viral attachment, recognition, and binding, and facilitates the entry of viral RNA into the host cell via endocytosis. The E3 protein promotes the correct folding of the E2 protein precursor and stabilizes E1/E2 trimer conformation. The 6K protein forms ion channels and participates in viral release by promoting vesicle fusion within the endoplasmic reticulum [

19,

20].

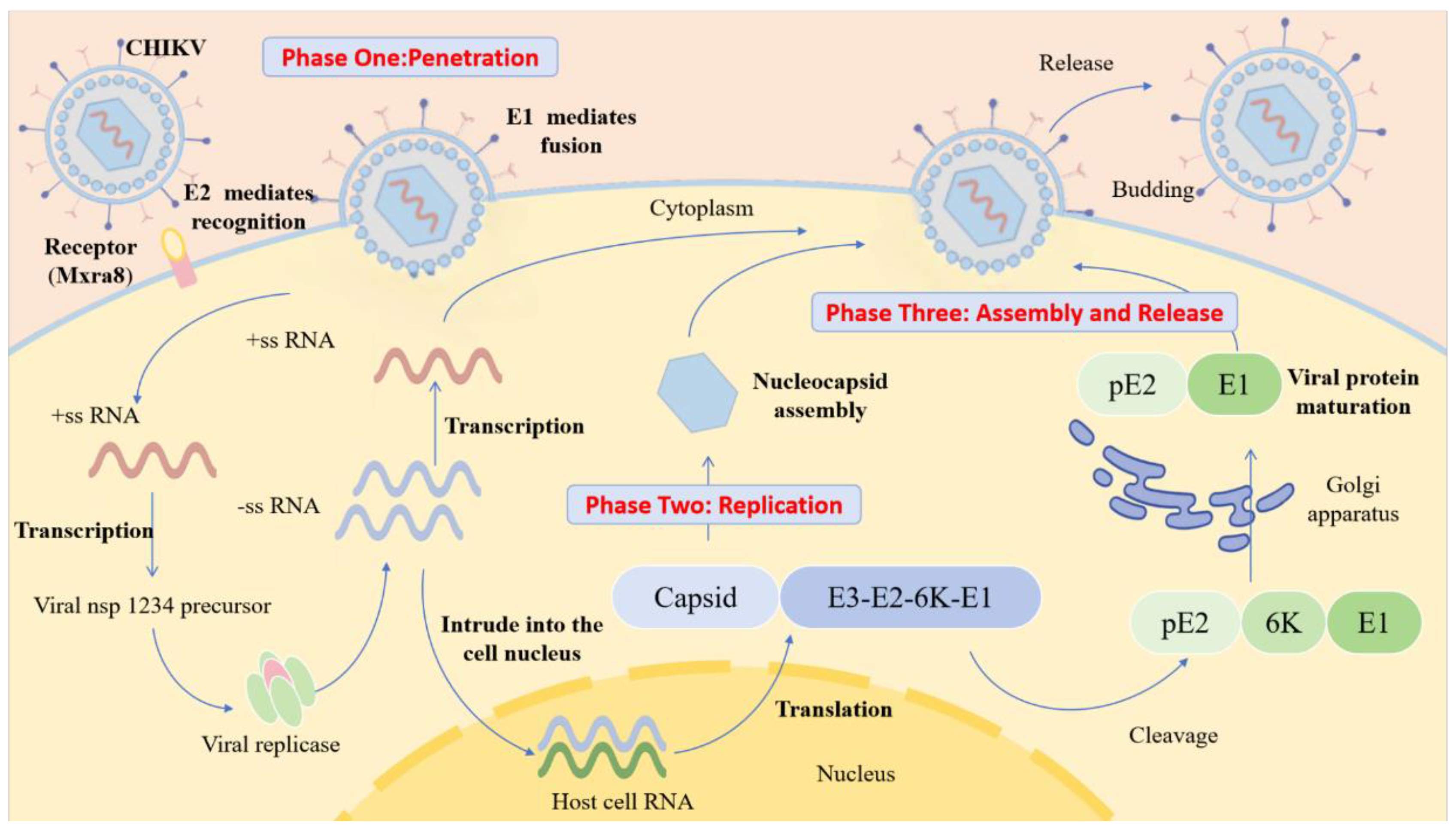

2.2. Infection Mechanism of CHIKV

CHIKV cell invasion pathways are cell type-specific, and the associated host cell receptors and binding molecules exhibit substantial diversity [

21,

22]. Among these, matrix remodeling-associated protein 8 (Mxra8) is one of the most well-characterized human CHIKV receptors and is widely expressed on the surface of epithelial and mesenchymal cells [

23,

24]. Both in vitro cell-based assays and animal model studies have confirmed that Mxra8 expression levels are positively correlated with the efficiency of CHIKV infection and that the degree of CHIKV infection and joint swelling symptoms in Mxra 8-deficient mice are significantly reduced [

25]. Notably, the absence, or low expression, of Mxra8 does not completely block CHIKV infection, indicating the presence of alternative receptors in the host. CD147, also known as basigin or EMMPRIN, is another validated CHIKV receptor widely expressed in fibroblasts, endothelial cells and other cell types. This molecule shares high structural homology with Mxra8, but its specific molecular interactions with CHIKV proteins remain to be further clarified [

26]. Mediated by E2 protein, CHIKV recognizes and binds to the host cell surface. It then enters target cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, where it interacts with Ras-related protein Rab-5A(RAB5)-positive endosomes and undergoes E1 protein-mediated membrane fusion [

27]. The fusion process is triggered by endosomal acidification, and the presence of cholesterol in the target membrane significantly augments fusion efficiency. It has been confirmed that the cholesterol-depleting agent methyl-β-cyclodextrin and lysosomotropic drugs, e.g., chloroquine and baflomycin, that inhibit endosomal acidification can effectively suppress CHIKV infection [

28], further confirming the central role of clathrin in the precise delivery of the CHIKV genome to the cytoplasm via endocytic vesicles.

In addition to the grid protein-mediated endocytosis pathway, non-clathrin-dependent pathways can also mediate CHIKV entry. Among these, micropinocytosis was shown to be an important alternative pathway for CHIKV infection of human muscle cells [

29]. This process is regulated by a complex signaling cascade. More specifically, following viral binding to the cell membrane, it activates signaling molecules, such as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). These RTKs then trigger intracellular signaling cascades that induce actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, leading to the formation of irregular folds and vesicular structures. Upon collapse of these structures, they engulf the virus-receptor complex and liquid-phase macromolecules to form macropinosomes, thereby completing viral internalization. This process relies on signal transduction from molecules, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase C, the Rho GTPase Rac1, and actin polymerization-mediated macropinosome formation. The synergistic effects of multiple entry pathways endow CHIKV with the ability to invade various cell types across different tissues, providing a key foundation for its extensive dissemination within the host [

30].

Figure 2.

The process of CHIKV infection. E2 protein mediates specific recognition and binding of virus to host receptor (Mxra8), driving the virus to attach to the cell surface. E1 protein mediates fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, releasing the viral +ssRNA genome into the cytoplasm. Viral +ssRNA is directly translated into nsP precursors, assembled into replication complexes, transcribed to generate -ssRNA and used as a template to synthesize progeny +ssRNA. At the same time, +ssRNA is translated to produce structural protein precursors. After the structural protein precursor is cut and processed, the capsid protein subunits bind to the progeny genomic RNA (gRNA) to form the nucleocapsid which then germinates to obtain an E2/E1 envelope, followed by the extracellular release of mature virus.

Figure 2.

The process of CHIKV infection. E2 protein mediates specific recognition and binding of virus to host receptor (Mxra8), driving the virus to attach to the cell surface. E1 protein mediates fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, releasing the viral +ssRNA genome into the cytoplasm. Viral +ssRNA is directly translated into nsP precursors, assembled into replication complexes, transcribed to generate -ssRNA and used as a template to synthesize progeny +ssRNA. At the same time, +ssRNA is translated to produce structural protein precursors. After the structural protein precursor is cut and processed, the capsid protein subunits bind to the progeny genomic RNA (gRNA) to form the nucleocapsid which then germinates to obtain an E2/E1 envelope, followed by the extracellular release of mature virus.

2.3. Mechanism Underlying CHIKV Immune Escape

After CHIKV infection, its viral RNA can be specifically recognized by host pattern recognition receptors, such as TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8, resulting in the activation of interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) and NF-κB signaling pathways. These pathways induce type I interferon (IFN) and interferon-stimulating factor (ISG) expression and initiate host antiviral immune response [

31]. However, CHIKV has evolved targeted immune escape strategies that precisely regulate host immune signals through non-structural proteins (NSPs) to achieve efficient immune escape. The core of this immune evasion is dependent on the specific functional mediation of non-structural proteins [

32]. Specifically, nsP1 interacts directly with host cell cycle-gMP-amp synthase (cGAS). Inhibiting the activation of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway blocks the production of type I IFN from the source, significantly weakening the host’s innate immune defense. The nsP2 blocks the host’s antiviral response through a dual mechanism. On the one hand, it guides RNA polymerase II in the nucleus to catalyze the protease degradation of subunit Rpb1, thereby inhibiting host cell gene transcription and reducing antiviral gene expression. On the other hand, it blocks the downstream transmission of the interferon signaling pathway by promoting the re-output of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [

33]. This prevents complete activation of the host’s innate and adaptive immune responses. With its ADP-ribohydroxy enzyme activity, nsP3 removes the ADP-nucleosylation modification of nsP2 and maintains a highly active state of nsP2 to assist the virus in evading host ADP-ribotransferase-mediated antiviral activity [

19,

34].

In addition to innate immune escape, CHIKV can also partially evade adaptive immune responses. Studies show that the virus can establish persistent infection in joint tissues and the core mechanism linked to CD8

+ T cell exhaustion. The expression levels of cytotoxic molecules, such as granzyme B and perforin, in CD8

+ T cells are significantly downregulated following infection, resulting in impaired ability to kill infected cells and inefficient viral clearance, thereby enabling viral persistence [

35].

3. Diagnostic Techniques for CHIKV

The clinical manifestations of CHIKV infection are highly heterogeneous and nonspecific. Core symptoms, such as fever and arthralgia, often overlap substantially with those of dengue virus, Zika virus and other viral infections. Therefore, accurate diagnosis based solely on clinical manifestations is challenging, making laboratory testing crucial for accurate diagnosis. Currently, laboratory testing for CHIKV infection primarily comprises three categories: nucleic acid testing, serological assays, and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Nucleic acid testing, as represented by RT-PCR, can directly target viral nucleic acid for rapid diagnosis [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Serological assays are conducted based on IgM and IgG antibodies for the middle to late stages of infection, respectively, as discussed below, and epidemiological surveys [

36,

37,

38,

39,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Studies have demonstrated that RT-PCR is the gold standard for the early detection of CHIKV with a positive detection rate exceeding 90% within the first four days of illness [

37]. A clinical study involving 646 cases demonstrated that RT-PCR detected 31 CHIKV-positive samples (4.79% positive rate), while simultaneous IgM antibody testing of these 31 samples yielded only one positive result [

45]. A retrospective study by Boonanek et al. further corroborated this outcome. They performed simultaneous RT-PCR and IgM antibody testing on 31 hospitalized children with suspected CHIKV infection. As a result, 30 cases were diagnosed via plasma RT-PCR, but only 1 case was positive for IgM antibodies [

44]. Based on such results, RT-PCR remains the preferred test method during the acute phase of CHIKV infection. Although nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are the gold standard for the diagnosis of viral infections, serological assays have emerged as important supplementary diagnostic tools owing to such RT-PCR limitations as narrow viremic window, high cost, and dependence on specialized equipment [

38]. Studies have demonstrated that RT-PCR exhibits the highest sensitivity during the early phase of CHIKV infection (1-4 days of the disease course) with a positive rate of over 90%, whereas the IgM detection rate is only 3.2%-13.3% during the same period. However, the IgM positive rate increases significantly to 51.6% starting from day 5 of illness, and its sensitivity exceeds that of RT-PCR by day 6, reaching over 90% by day 10 [

37]. The IgG antibody immune response is relatively delayed and is rarely detectable within days 1-9 of illness. The positive rates on days 10 and 12 are 50.0% and 82.0%, respectively, indicating that IgG antibodies are more suitable for identifying past infections [

37]. Therefore, CHIKV diagnosis should adopt a phase-specific testing strategy whereby RT-PCR detection is preferred on days 1-4, but IgM detection is preferred starting from day 5 when the body starts producing detectable antibodies. This pattern can improve the accuracy of diagnosis throughout the entire course, helping to reduce misdiagnosis and accelerate accurate diagnosis [

37].

In recent years, NGS, particularly metagenomic NGS (mNGS), has gradually emerged as an important tool in the field of infectious disease diagnosis. This technology does not require a pre-specified target pathogen and can simultaneously detect a wide range of microorganisms in samples, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Thus, mNGS can significantly improve diagnostic efficiency and accuracy, and it has been widely used in clinical research and practice [

36,

39,

46]. NGS technology was used for CHIKV sequencing and analysis in studies of chikungunya fever outbreaks in India (2019-2022), Thailand (2019 Bangkok pediatric severe cases and the ongoing epidemic during 2020-2023), and Bangladesh (2024). It was consistently confirmed that 1) the circulating strains in each region belong to the East/Central/South African (ECSA) genotype (further denoted as the ECSA-IOL sublineage in Thai studies) and 2) these circulating strains generally harbor the characteristic E1-K211E mutation. Thai studies also found that this mutation often coexists with the E2-V264A mutation. This technology is also used for CHIKV genetic variation analysis, as well as evolutionary tracing, e.g., distinguishing sublineages between Bangladeshi strains and the 2017 local strain. It has also been used for regional transmission pathway analysis. e.g., analyzing genetic similarity between Thai strains and those from neighboring countries. NGS technology also provides key molecular diagnostic support for etiological confirmation and epidemiological surveillance of clinical cases, including pediatric cases [

37,

39,

40,

44]. Another case study used NGS to sequence and analyze the viral genome in patients’ plasma and cerebrospinal fluid samples. As a result, researchers identified a specific marker for the deletion of 62 amino acids in the nsP3 region through sequence alignment analysis, confirming the attenuated VLA1553 vaccine strain [

36].

4. Vaccine Development and Clinical Trial Dynamics of CHIKV

Research on CHIKV vaccines has remained in the exploratory stage in recent years. Currently, two Chikungunya vaccines approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are available in the U.S.A. One is the live attenuated vaccine IXCHIQ, but its use is restricted; the other is the virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine VIMKUNYA. Meanwhile, several potential vaccine candidates have progressed to preclinical development, including in vitro experiments and animal studies. Some have advanced further to the clinical trial stage (

Table 1). Currently, CHIKV vaccines under development can be categorized by their technical platforms, such as inactivated vaccines, live attenuated vaccines, subunit vaccines, VLP vaccines, or recombinant viral vector vaccines [

47].

4.1. FDA-Approved CHIKV Vaccines

The live attenuated vaccine IXCHIQ (VLA1553) is based on the ECSA genotype CHIKV strain LR2006- OPY1, which was isolated from Reunion Island in 2006. It achieves attenuated virulence by genetically modifying the virus to delete 62 amino acids at the C-terminus of the nsP3 and inserting the AYRAAAG linker sequence. The vaccine is ultimately produced by propagating the virus in Vero cells, followed by purification and lyophilization. However, in August 2025, the FDA urgently suspended its use in the United States based on reports of multiple serious adverse events. It is currently available only in the European Union (EU) and Canada [

72]. In addition, the vaccine is authorized for a limited population, excluding pregnant women and those with immune deficiencies, and requires careful assessment for people over 65 years old [

73]. The VLP vaccine VIMKUNYA (PXVX0317) was developed based on the West African genotype CHIKV strain 37997 isolated from Senegal. During production, DNA plasmids encoding CHIKV structural proteins (capsid, E3, E2, 6K, and E1) are transfected into human embryonic kidney VRC293 cells to generate VLPs. These proteins autonomously assemble into genome-free VLPs which are then purified via centrifugation and chromatography. Aluminum hydroxide adjuvant is added to some formulations to boost immunogenicity [

60]. It is currently approved for use in people aged 12 and above, while safety data for children and pregnant women are still being accumulated. Furthermore, reactivity should be monitored in previously infected individuals [

61]. The incidence of swelling at the injection site after vaccination (10%) is significantly higher in baseline seropositive individuals than in seronegative individuals (0.6%). While the vaccine poses little serious risk, advance notification is still required [

62].

4.2. Preclinical and Clinical Trials of CHIKV Vaccines

The inactivated vaccine BBV87 was prepared by inactivating whole-virus particles of the ECSA genotype CHIK/03/06 strain isolated in India in 2006 [

49]. Phase III clinical trials showed that neutralizing antibody titers peaked 6-8 weeks after vaccination. Multiple doses ensured protective efficacy, and the vaccine also provided cross-protection against multiple CHIKV genotypes. The core advantages are high safety, suitability for immunocompromised populations, clear vaccine components, strong stability, and easy storage, transportation and supervision. Nonetheless, it has some shortcomings, such as low immunogenicity, the need for multiple immunizations, and the reliance on large cell cultures for production, all of which add up to inefficiency and high cost [

48].

The live attenuated CHIKV-NoLS vaccine retains viral replication capability, albeit at an attenuated rate, and thus effectively induces a robust immune response [

55]. The development of this vaccine is based on modifying the N-terminal nuclear localization sequence (NLS) in the CHIKV capsid protein. Specifically, mutations in the NLS significantly reduce the capsid protein’s nuclear entry efficiency, thereby attenuating viral replication [

56]. The vaccine uses the RNA genome of attenuated CHIKV as the antigen, and the antigen is delivered via the CAF01 adjuvant. The CAF01 adjuvant maintains antigenic stability and increases immune response. Preclinical animal experiments showed that a single immunization could induce persistent neutralizing antibodies and cellular immune memory [

57]. Also, the CAF01 liposome delivery system could directly deliver the RNA genome in vivo, providing technical support for large-scale vaccine production [

58,

74]. The vaccine has not yet entered clinical trials, and its safety and adjuvant production need to be verified.

Subunit CHIKV vaccines are developed by targeting the CHIKV E2 envelope glycoprotein, a key target for neutralizing antibodies [

59]. The expression efficiency of CHIKV E2 protein in prokaryotic systems was raised via codon optimization and was produced through recombinant plasmid construction, protein expression, and purification. Although protein expression has been identified and antigenic activity has been completed, immunogenicity and in vivo protective effect still need to be verified by animal and human trials.

Recombinant viral vector vaccines stimulate immune responses by modifying specific viral genomes to insert and express CHIKV antigen-encoding genes. The replication-deficient chimpanzee adenovirus vector vaccine used chimpanzee adenovirus with low pre-immunity as the vector. After knocking out the replication gene and inserting the CHIKV antigen gene, it elicited strong immunity with a single dose in mouse experiments [

63]. Measles Virus Vectored (MV)-CHIK used a live attenuated measles vaccine strain as a vector and presented CHIKV capsid and membrane structural proteins [

64]. Phase II trials showed that two doses of the vaccine could induce specific antibodies with good safety [

65]. The former is in the preclinical stage, while the latter requires further assessment of long-term immune persistence [

66].

The chimeric vaccine (EILV/CHIKV chimeric with Eilat virus) used insect-specific Eilat virus as the backbone and replaced its structural protein genes with the corresponding gene of CHIKV. The chimeric virus could replicate in insect cells, but since it could not replicate in mammalian cells, it was considered non-pathogenic [

69]. Preclinical animal experiments showed that it could activate T cells, memory B cells and antibody responses in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, it achieved cross-neutralization of multiple lineages of CHIKV [

67,

68], and it induced multiple innate immune pathways, including Toll-like receptor signaling, antigen-presenting cell activation and NK receptor signaling, providing rapid protection with outstanding safety [

70]. Long-term safety needs to be validated in primate models, and clinical translational progress is required.

The nucleic acid vaccine MRNA-1388, which is the first CHIKV RNA vaccine, synthesizes mRNA encoding CHIKV antigen through in vitro transcription. Encapsulated and protected with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), the vaccine is delivered to host cells to express antigen and trigger an immune response. Phase I trials showed good safety at all doses, rapid induction of long-lasting neutralizing antibodies, immunogenicity comparable to that of live attenuated vaccines, and no significant safety issues after vaccination [

71]. However, it showed poor mRNA stability, required cold chain transportation, and long-term safety data are lacking.

5. Drug Development Strategies for Anti-CHIKV Infection

5.1. Viral Entry Inhibitors

Virus entry is the key rate-limiting step in initiating infection, so inhibitors targeting this process constitute the core of an early intervention strategy. Their mechanisms of action focus on two main aspects: preventing viral particles from binding to host cell receptors or interfering with pH-dependent virus-endosomal membrane fusion.

Attachment inhibitors: FL series compounds like FL23 and FL3 effectively inhibited the CHIKV attachment process by targeting the host cell membrane protein Prohibitin-1 [

75,

76]. Studies indicated that these compounds, including sulfonamide 1M, could only block virus entry before infection and were ineffective after infection, confirming their specificity in the early stages of invasion [

77]. Suramin, a multivalent anionic compound, effectively inhibited the binding of the virus to the cell surface sulfated glycosaminoglycans and directly intercalated into the virus E1/E2 heterodimer to interfere with its function [

75,

78]. Additionally, suramin inhibited both early virus-cell attachment and membrane fusion by targeting the CHIKV E2 protein. It should be noted that mutations in E2 protein N5R/H18Q could cause CHIKV to acquire specific resistance and affect suramin’s inhibitory effect on the fusion step [

79]. However, suramin also showed inhibitory synergism with EGCG in vitro and could effectively block CHIKV envelope-mediated gene transfer [

80,

81]. Endosome fusion inhibitors: Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine effectively inhibited the membrane fusion function of CHIKV E1 protein by increasing endosomal pH [

75,

76,

78,

80]. Further studies reported that chloroquine effectively inhibited CHIKV in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations of 5-20 μM with a clear therapeutic window. It was most effective within 1-3 hours post-infection, significantly reducing viral infection rates by primarily blocking early CHIKV invasion to exert preventive effects [

82]. However, the clinical efficacy of these compounds did not meet expectations, highlighting differences between the in vitro model and the complex human environment [

78,

80].

Multi-mechanism entry inhibitors: Berberine, Emodin, and their derivatives inhibited CHIKV invasion by downregulating the host receptor Mxra8 or delaying endosomal acidification [

83]. Berberine inhibited CHIKV replication and exhibited broad-spectrum antiviral activity (EC₅₀ = 1.8 μM), thereby exerting significant antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the MAPK signaling pathway (ERK, p38, JNK) activated by CHIKV infection [

84,

85]. EGCG blocked cell attachment by binding to viral surface proteins to inhibit pseudovirus entry, viral replication and progeny production, while exerting direct antiviral effects at multiple stages of CHIKV infection [

75,

78,

83]. Abidol inhibited viral attachment and entry at an early stage, while destroying the endosomal/lysosomal membrane structure to prevent viral release, and its drug-resistant mutation G407R was located in the E2 protein of CHIKV [

75,

86]. Imipramine and U18666A effectively inhibited viral entry by interfering with intracellular cholesterol transport and disrupting the lipid environment required for viral fusion [

75,

86].

Table 2.

Viral entry inhibitors.

Table 2.

Viral entry inhibitors.

| Drug Names |

Mode of action |

Median effective concentration EC50 (μmolL⁻¹) |

Median cytotoxic concentration CC50

(μmolL⁻¹)

|

Reference |

| FL23 |

Inhibition of adhesion (Targeting Prohibitin-1) |

0.21 ± 0.03 |

8.9 ± 0.5 |

[75,76,77] |

| FL3 |

0.17 ± 0.02 |

7.8 ± 0.4 |

[75,76,77] |

| FL26 |

0.28 ± 0.04 |

10.1 ± 0.7 |

[75,76,77] |

| FL27 |

0.31 ± 0.03 |

12.4 ± 0.8 |

[75,76,77] |

| FL28 |

0.25 ± 0.02 |

9.5 ± 0.6 |

[75,76,77] |

| FL29 |

0.33 ± 0.05 |

13.2 ± 1.1 |

[75,76,77] |

| Suramin |

Inhibition of attachment and membrane fusion (targeting E2 protein) |

4.3 ± 0.3 |

>200 |

[75,78,79,80,81] |

| Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine |

Inhibition of endosomal fusion (increase in endosomal pH) |

8.8 ± 0.7 |

>100 |

[75,76,78,82] |

| Berberine |

Downregulation of Mxra8 receptor and delay of endosomal acidification |

1.8 ± 0.2 |

>100 |

[76,83,84,85] |

| Emodin and its derivatives |

6.1 ± 0.4 |

>100 |

[76,83] |

| EGCG |

Binds to viral surface proteins and blocks attachment |

8.7 ± 0.7 |

>100 |

[75,76,78] |

| Abidol |

Inhibition of attachment and entry; destroys the endosomal membrane |

IC₅₀ ≈ 5–10 µg/mL(10–20 μmol/L) |

n.s. |

[75,86] |

| imipramine |

Interferes with cholesterol transport |

2.1 ± 0.3 |

>100 |

[75,86] |

| U18666A |

1.3 ± 0.2 |

>100 |

[75,86] |

5.2. Viral Replication and Gene Expression Inhibitors

This stage of the strategy focuses on the core complex of CHIKV replication, including direct targeting of virus-encoded nsPs and exploitation of host-dependent factors.

Targeting viral nsPs: nsP1 inhibitor: The nsP1 protein was found to be a key factor in CHIKV replication and was responsible for catalyzing the synthesis of the 5’cap structure of viral RNA. Its dual enzymatic activity as a guanylate transferase and methyltransferase made it an important antiviral target [

87]. Based on their mechanisms of action, nsP1 inhibitors could be categorized into three classes. The MADTP and CHVB series directly inhibited the activity of methyltransferase (MTase) and guanylate transferase (GTase) by binding to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) catalytic sites. The FHNA series, on the other hand, interfered with the membrane binding and oligomerization of nsP1 by targeting the secondary binding pocket of the RAMBO domain without directly inhibiting enzymatic activity [

88]. In addition, lead compounds, such as pyrimidine derivatives, GTP, and nucleoside analogues, were shown to significantly inhibit nsP1, thereby suppressing CHIKV replication [

89]. It should be noted that the nsP1-targeted MADTP-resistant strain still maintained mosquito-borne transmission efficiency comparable to that of the wild-type strain and could stably retain the resistant genotype in saliva, suggesting that drug development for this target should address the risk of resistance [

90].

nsP2 inhibitors: nsP2 protease was identified as having a key role in CHIKV replication and was responsible for processing viral multiprotein precursors. A variety of compounds, such as ID1452-2, Bassetto, and Compound 1, were confirmed to have inhibitory activity against nsP2 protease [

75,

78,

80]. The nsP2 protease inhibitor RA-0002034 could efficiently and selectively inhibit CHIKV replication by specifically modifying the cysteine residue in nsP2 [

91]. The natural compound withaferin A (WFA) effectively blocked CHIKV multiprotein processing and RNA synthesis by specifically binding to nsP2 protease and utilizing its oxidative properties to inhibit enzymatic activity, an effect that could be reversed by reducing agents [

92]. J12/J13, as novel CHIKV nsP2 protease inhibitors, effectively inhibited CHIKV replication in cell models, with J13 also exhibiting good oral bioavailability [

93]. The antihypertensive drug telmisartan and neomycin could inhibit CHIKV replication at low molar concentrations by strongly binding to nsP2 protein and inducing conformational changes, thereby holding potential as anti-CHIKV agents [

94]. Hsp90 promoted CHIKV protein synthesis by directly stabilizing nsP2 protein and activating the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Its inhibitor, geldanamycin, and its second-generation analogue, 17-AAG, effectively inhibited viral replication by disrupting Hsp90-nsP2 interaction and blocking the signaling pathway [

95].

nsP3 inhibitor: The CHIKV nsP3 protein was shown to have multiple functions throughout the CHIKV life cycle with a structure consisting of a macrodomain, an α-virus-specific domain (AUD), and a hypervariable domain (HVD) [

96]. Among pyrazinazole compounds, the lead compound CMPD 104 exhibited high binding affinity and favorable drug-like properties for the CHIKV nsP3 protein. This compound, which could form a stable complex with CHIKV nsP3, held high potential for the development of nsP3-targeted anti-CHIKV drugs [

97]. Derivatives B1 and B7 based on the Lomerizine (LOM) structure exhibited significant anti-CHIKV activity, and their mechanisms of action were closely related to targeting the viral nsP3 protein. B1 could stably bind to the nsP3 active site and exhibited a favorable ADMET property. This series of compounds provided a novel strategy for the development of anti-CHIKV drugs targeting nsP3 [

98]. Harringtonine exerted an anti-CHIKV effect by blocking early viral replication through inhibiting the translation of key viral proteins such as nsP3 and E2. Harringtonine effectively inhibited the synthesis of CHIKV proteins, such as nsP3, and disrupted the formation of CHIKV replication complexes, thereby comprehensively suppressing CHIKV RNA replication. It exhibited inhibitory activity against a variety of alphaviruses, demonstrating broad-spectrum antiviral potential [

78,

99].

nsP4 inhibitors: The nsP4, as a core RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) for CHIKV replication, proved to be an important target for nucleoside antiviral drugs. The conserved C-terminal RdRp domain was responsible for CHIKV genomic and subgenomic RNA synthesis, and specific N-terminal adenylyltransferase activity was involved in the formation of the poly(A) tail. Nucleoside drugs, such as favipiravir and sofosbuvir, effectively inhibited CHIKV replication by mimicking natural nucleotides that, once inside the cell, are metabolized and then integrated into the nascent RNA strand, thereby triggering chain termination, or fatal mutations [

75,

78,

80]. Compound A, as a benzimidazole derivative, could potently inhibit multiple CHIKV strains at nanomolar concentrations. The methionine residue at position 2295 (M2295) in the RNA polymerase functional domain of the nsP4 protein was a key target. Compound A exerted antiviral effects by specifically inhibiting RdRp function, effectively suppressing multiple CHIKV strains [

100]. The ribonucleoside analogue 4’-fluorouridine (4’-FlU) was also a highly effective inhibitor targeting CHIKV nsP4 RdRp, effectively suppressing CHIKV replication by inhibiting the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase function of the nsP4 protein. Oral administration significantly reduced CHIKV viral load and alleviated symptoms, thereby showing potential for the development of anti-CHIKV drugs [

101,

102]. In addition, the Cobalt (III) thiosemicarbazone complex exerted a potent anti-CHIKV effect by targeting the CHIKV nsP4 protein and acting at the post-replication stage [

103].

Table 3.

Inhibitors of viral replication and gene expression.

Table 3.

Inhibitors of viral replication and gene expression.

| Drug Names |

Mode of Action |

Median Effective Concentration EC50 (μmolL⁻¹) |

Median Cytotoxic Concentration CC50(μmolL⁻¹)

|

Reference |

| MADTP-314 |

Inhibition of nsP1 (targeting SAM site) |

0.8 ± 0.1 |

>100 |

[87,88] |

| MADTP-372 |

0.5 ± 0.1 |

>100 |

[87,88] |

| FHNA series |

Suppression of nsP1 (interference with membrane binding) |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[88] |

| Pyrimidine derivatives /GTP/ nucleoside analogues |

Inhibition of nsP1 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[89] |

| 6-azauridine |

3.2 ± 0.3 |

>20 |

[89] |

| ID1452-2, Bassetto, Compound 1 |

Inhibition of nsP2 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[75,78] |

| RA-0002034 |

0.9 ± 0.1 |

>100 |

[91] |

| Withaferin A (WFA) |

0.6 ± 0.1 |

>50 |

[92] |

| J12 |

0.7 ± 0.1 |

>100 |

[93] |

| J13 |

0.5 ± 0.1 |

>100 |

[93] |

| telmisartan |

8.3 ± 0.6 |

>200 |

[94] |

| novobiocin |

5.7 ± 0.4 |

>200 |

[94] |

| geldanamycin |

Inhibition of Hsp90 (disruption of HSP90-NSP2 interaction) |

0.08 ± 0.01 |

2.1 ± 0.2 |

[95] |

| 17-AAG |

0.12 ± 0.02 |

4.5 ± 0.3 |

[95] |

| CMPD 104 |

Inhibition of nsP3 |

1.4 ± 0.1 >100 |

1.4 ± 0.1 >100 |

[97] |

| Derivatives B1/B7 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[98] |

| Harringtonine (HT) |

Inhibition of nsP3/E2 protein translation |

0.24 |

2.04 |

[99] |

| favipiravir |

Inhibition of nsP4 (nucleoside analogue) |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[75,78,80] |

| Sofosbuvir |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[75,78,80] |

| Compound A |

Inhibition of nsP4 RdRp |

3.1 |

>50 |

[100] |

| 4 ‘-fluoruridine (4’ - FlU) |

Inhibition of nsP4 RdRp |

0.3-0.42 |

>100 |

[101,102] |

| Cobalt(III) thiosemicarbazone complex |

Inhibition of nsP4 |

2.97 |

420 |

[103] |

5.3. Host-Targeted Antiviral Therapy (HDAT)

The HDAT strategy aimed to reduce the risk of viral drug resistance by targeting the host factors necessary for viral replication with broad-spectrum antiviral potential.

Regulating nucleotide metabolism was a key strategy for combating CHIKV. Ribavirin worked by depleting the GTP pool and misincorporating into RNA, while mycophenolic acid interfered with viral nucleic acid synthesis by inhibiting Inosine Monophosphate Dehydrogenase (IMPDH) [

75,

78,

80]. In vitro studies showed that ribavirin in combination with interferon-α exerted a potent synergistic effect, reducing CHIKV viral load at clinical concentrations [

104]. This combination regimen also showed synergistic effects in dengue virus [DENV] studies, inhibiting most DENV replication [

105]. Mycophenolic acid (MPA) could potently inhibit CHIKV replication and block CHIKV-induced apoptosis by suppressing IMPDH to deplete the intracellular GTP pool [

106].

Inhibition of Hsp90 function was an effective strategy against CHIKV. Geldanamycin and its derivatives (HS-10, SNX-2112) disrupted the stability of viral replication complexes by inhibiting HSP90 and inducing degradation of viral non-structural proteins such as nsP2 and nsP3. Hsp-90 supports the assembly and function of viral replication complexes by maintaining the proper folding and stability of viral proteins through its molecular chaperone function [

75,

78,

80]. The specific interactions between HSP-90 and nsP3 and nsP4 are crucial for viral replication. Inhibiting Hsp90 function can effectively block CHIKV replication, thereby exerting an anti-CHIKV effect [

107]. Another mechanistic study showed that Hsp90 interacted with CHIKV nsP2 and activated the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway to promote CHIKV mRNA translation, playing a key role in early CHIKV replication. Different CHIKV strains had varying sensitivities to Hsp90 inhibitors such as geldanamycin, which offered new insights for the development of anti-CHIKV drugs.

Host factors could also act as effective antiviral targets. Silvestrol inhibited CHIKV replication by specifically inhibiting the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4A to block the translation of CHIKV mRNA [

78,

80]. In addition, targeting various other host factors, such as FASN, SFK, and mTORC1/2, was shown to exert anti-CHIKV activity [

80]. Another study showed that the sphingosine kinase inhibitor SLL3071511 exhibited anti-CHIKV activity in vitro, further suggesting that this target possessed host-directed anti-CHIKV therapeutic potential [

108].

5.4. Innate Immune Response Activators

Strengthening the host’s innate antiviral defenses is a strategy that has a high genetic barrier with less likelihood of inducing drug resistance.

RIG-I/MDA5 Agonists: In the early stage of CHIKV infection, RIG-I within host cells acts as a core innate immune recognition receptor, precisely recognizing the 3′-UTR region of the CHIKV genome and initiating an early host antiviral response [

109]. Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) did not exhibit significant binding to the viral genome [

110]. However, during acute CHIKV infection, the host innate immune system was significantly activated. This, in turn, resulted in the activation of MDA5, along with subsequent IL-12 and IFN-α responses, in association with more effective CHIKV clearance, as reflected by reduced CHIKV viral load [

111]. CHIKV inhibited MDA5/RIG-I-mediated NF-κB activation through nsP2, E1, and E2, thereby interfering with type I interferon production and significantly suppressing the MDA5 pathway [

112]. This cascade effectively suppressed innate immune defenses, allowing the virus to escape surveillance.

cGAS-STING Pathway Agonists: The synthetic molecules diABZI and cAIMP exhibited preventive and therapeutic potential by activating the STING-dependent type I interferon pathway [

109]. In CHIKV infection, the host sensed cytoplasmic DNA following infection through cGAS and activated the STING pathway to limit CHIKV replication [

113]. Systematic screening showed that STING agonists, including cAIMP, diABZI, and 2′,3′-cGAMP, and the Dectin-1 agonist hard-core glycan all had broad-spectrum antiviral properties and could inhibit a variety of RNA viruses, including CHIKV. cAIMP treatment reversed CHIKV-induced dysregulation of cell repair, immune, and metabolic pathways and provided protection in mouse models of chronic CHIKV-induced arthritis [

114]. Additionally, cAIMP activated the STING-TBK1-IRF3 axis, induced a robust type I interferon response, and reshaped cellular metabolism, effectively inhibiting CHIKV replication in both cellular and mouse models. Its effect was superior to that of the direct-acting antiviral drug remdesivir, establishing the potential of STING agonists as host-directed anti-CHIKV strategies [

109].

TLR agonists: TLR agonists act as innate immune activators and have played a significant role in CHIKV infection. During CHIKV infection, TLR3 mainly played a protective antiviral role, while TLR4 was exploited by the virus to facilitate its entry into the host cell. The activation of TLR triggered a robust cytokine storm, which is associated with acute and chronic symptoms of the disease, such as arthralgia [

115]. Poly (I:C) (TLR3 ligand) and Imiquimod (TLR7 ligand) activate the NF-κB and IRF pathways by viral mimicry of nucleic acids, inducing type I interferon production [

109]. Studies found that CHIKV inhibited the innate immune response mediated by the TLR3/TLR7 pathways, resulting in changes in the expression levels of TLRs, antiviral genes, and cytokines. In contrast, the use of TLR3 agonists (Poly (I:C)) effectively inhibits CHIKV replication by upregulating the TLR3 pathway and related antiviral genes, highlighting its potential as an anti-CHIKV drug [

116,

117]. In addition, Poly (I:C) showed significant inhibitory effects on CHIKV replication in human bronchial epithelial cells [

118].

5.5. Novel Therapeutic Targets and Strategies

With the in-depth investigation of CHIKV pathogenesis, new therapeutic targets continue to be discovered, offering important directions for the development of anti-CHIKV drugs.

Natural products have been an important source of anti-CHIKV drugs. Among them, salidroside exerts anti-inflammatory and cell-protective effect through the synergistic effects of multiple pathways at the cellular level by regulating multiple targets, such as TNF, IL6, NFKB1, mediating the PI3K-Akt, NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, and inhibiting the activity of GPX4 [

119]. In addition, flavonoids, such as Baicalein and Fisetin, alkaloids like Harringtonine (EC₅₀=0.24µM), and diterpenoids like Trigocherrierins could effectively inhibit the key links of viral replication, showing good anti-CHIKV activity [

120,

121]. Curcumin, a natural product, could significantly relieve pain and improve symptoms of acute and chronic arthritis by maintaining cartilage integrity and reducing the loss of proteoglycans and type II collagen [

122]. Its nanoformulations could achieve synergistic relief of pain and structural damage in osteoarthritis by regulating inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, TNF-α and MMPs, and upregulating CITED2 [

123].

Targeting specific cytokine pathways: The IL-17A signaling pathway played a key regulatory role in CHIKV-induced inflammatory responses and joint damage. Inhibiting this pathway could significantly alleviate CHIKV-induced inflammation and joint damage, providing important therapeutic potential for the treatment of CHIKV-related inflammation and joint lesions [

124].

Regulation of the microbiota-metabolic axis: The microbiota-metabolic axis regulated CHIKV infection and joint inflammation. In addition to typical symptoms, CHIKV infection could be accompanied by gastrointestinal manifestations. Fusobacterium nucleatum is enriched in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and its outer membrane component FadA can exacerbate joint inflammation and pain [

125]. Gut microbiota had an anti-CHIKV protective effect with depleted microbiota, increasing viral load, inflammation and tissue damage. This mechanism was associated with microbiota deficiency weakening the TLR7-MyD88 signaling pathway in pDC cells and inhibiting type I interferon production [

126]. Biota metabolites like deoxycholic acid could increase interferon response. A high-fiber/butyrate diet exacerbated arthritis in specific models, suggesting complex regulation of diet-microbiota-immune interactions [

127].

Table 4.

Host targeting, immunomodulation and other antiviral drugs.

Table 4.

Host targeting, immunomodulation and other antiviral drugs.

| Drug Names |

Mode of Action |

Median Effective Concentration EC50 (μmolL⁻¹) |

Median Cytotoxic Concentration CC50(μmolL⁻¹)

|

References |

| Ribavirin |

Exhaustion of GTP, mis- incorporation into RNA |

100.5 |

786.6 |

[75,78,80,104] |

| Mycophenolic acid (MPA) |

Inhibition of IMPDH and depletion of GTP |

0.56 |

65.2 |

[75,78,80,106] |

| HS-10 |

Suppression of HSP90 |

0.15 ± 0.02 |

6.2 ± 0.5 |

[75,78,80,95,107] |

| SNX-2112 |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

3.8 ± 0.3 |

[75,78,80,95,107] |

| Silvestrol |

Inhibition of eIF4A |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[78,80] |

| Sphingosine kinase inhibitor (SLL3071511) |

Inhibition of sphingosine kinase |

2.1 |

16.2 |

[108] |

| diABZI |

cGAS-STING pathway agonists |

0.16 |

>10 |

[109] |

| cAIMP |

1.2 |

>100 |

[109,114] |

| 2′,3′-cGAMP |

3.5 |

>100 |

[114] |

| Hard-core glycans |

Dectin-1 agonist |

~0.011 x 10⁻³ |

>0.083 x 10⁻³ |

[114] |

| Poly(I:C) |

TLR3 agonist |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[109,116,117,118] |

| Imiquimod |

TLR7 agonist |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[109] |

| Salidroside |

Multi-target anti-inflammatory, cell protective |

25.3 |

>200 |

[119] |

| Flavonoids (e.g.,Baicalein, Fisetin) |

Inhibition of viral replication |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[120,121] |

| Diterpenoids (Trigocherrierins) |

3.7 (Trigocherrierin A) |

89.2 (Trigocherrierin A) |

[121] |

| Harringtonine |

0.24 |

2.04 |

[121] |

| Curcumin and its nanoformulations |

Anti-inflammatory, protection of cartilage, arthritis relief |

n.s. |

n.s. |

[122] |

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The global prevalence of CHIKV poses a major public health threat with three core research hotspots currently identified. First, virus mutation monitoring provides data support for precise prevention and control in different regions and among different susceptible populations. This can be accomplished through dynamically tracking the genetic variation characteristics of viral strains. Second, analyzing the mechanism underlying chronic arthritis focuses on population-specific differences in the molecular pathways of joint damage following CHIKV infection (e.g., in the elderly and manual laborers), laying a theoretical foundation for developing stratified intervention plans for sequelae. Third, the development of multivalent vaccines aims to cover different viral lineages and meet the needs of special populations, including infants and young children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals. This has become a key direction in CHIKV prevention and control research.

Although progress has been made in detection technologies for CHIKV, these technologies still face multiple challenges that hinder their rapid and accurate global application. As the gold standard test for CHIKV, RT-PCR imposes strict requirements on laboratory environment, equipment and operators, and it is time-consuming and relatively expensive. These limitations make it difficult to utilize in CHIKV-endemic developing countries and remote areas. Such limitations also hinder rapid, large-scale screening during outbreaks. At present, point-of-care testing technologies, such as rapid diagnostic kits, are convenient and fast, but their sensitivity and specificity are sometimes lower than those of laboratory methods, especially when the viral load is low or in the later stages of infection when false negative or false positive results may occur. Additionally, CHIKV may continue to mutate, so the effectiveness of existing detection reagents, particularly primers, probes, and antibodies, in detecting emerging viral variants needs to be continuously monitored and assessed. Looking ahead, point-of-care testing (POCT) technology will gradually gain wider adoption. On the one hand, nucleic acid POCT devices that integrate microfluidic chips and isothermal amplification technology will become a research focus. These devices will combine sample processing, nucleic acid amplification and result detection. This combination enables highly sensitive and specific viral nucleic acid testing to be carried out in a short time, even in resource-challenged environments. On the other hand, the development of rapid test kits that require no nucleic acid extraction and provide visual readouts will make them suitable for primary care institutions and home use where specialized equipment is unavailable. In addition, with AI technology, future testing devices may be connected to smartphone apps to enable automatic interpretation of test results and real-time epidemic reporting, building a powerful regional data network to provide data support for global epidemic prevention and control.

In addition to the above-mentioned technical challenges in detection, the prevention and control of CHIKV also faces dual challenges. Seroepidemiologic and animal model evidence, as well as neutralizing antibody titers, are the core protective test indicators for CHIKV vaccines. Future research and development will focus on three scientific directions. First, based on E1/E2 protein structure data, antigens can be optimized through multi-epitope fusion and conformational modification in combination with AI to predict viral variations with the aim of developing broad-spectrum vaccines covering mainstream genotypes. For mRNA vaccines, a novel LNP vector validated by COVID-19 vaccines can be used to strengthen stability and reduce cold chain dependence. Second, research on vaccines for specific populations will be advanced. Low-reactivity inactivated vaccines will be developed for those with weakened immune systems. TLR9 agonist adjuvants will be used to boost immunity for infants and young children, and combined vaccination strategies will be explored for the elderly. Phase II/III trials for children and the elderly are expected to be completed between 2026 and 2028. Third, vaccine production capacity can be expected to increase through cell-free synthesis, continuous flow culture and other technologies. By unifying clinical trial standards based on the WHO framework, China’s BBV87 vaccine will advance to international multi-center Phase III trials. At the same time, neurotoxicity biomarkers will be screened based on IXCHIQ adverse event data, a long-term safety monitoring network will be constructed, and ultimately a scientific and efficient CHIKV prevention system will be formed. Research and development strategies need to be optimized for different applicable populations. For example, low-toxicity adjuvant formulations will be developed for infants and young children, safety grading assessment standards will be established for pregnant women, and enhanced immunity will be engineered for the elderly, along with optimizing production and costs through technological innovation to improve accessibility. Although breakthroughs have been made in the development of inhibitors targeting viral entry and replication, further consideration must be given to pharmacokinetic differences in children, pregnant women, and the elderly.

Author Contributions

N.Z. and S.J. conceived the idea. Z.Z., H.J., Z.S., J.X., X.Z. and J.Z. wrote the draft, and N.Z. and S.J. edited and finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to submit this manuscript to Viruses.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Hangzhou City University (grant No.: S202513021066 and F-202504) to N.Z. and J.Z.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tiozzo, G.; de Roo, A.M.; Amaral, G.S.G.D.; Hofstra, H.; Vondeling, G.T.; Postma, M.J. Assessing chikungunya’s economic burden and impact on health-related quality of life: Two systematic literature reviews. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0012990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. L., A; D. T., S. Chikungunya virus: epidemiology, replication, disease mechanisms, and prospective intervention strategies. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 737–749. [Google Scholar]

- Maio, F. F. C. P. d. A. D.; Vaz, d. S. A. S.; Judith, R.; Lusiele, G.; Lopes, M. M. E.; Machado, d. S. A.; Patrick, G.; Patrícia, B. Vertical transmission of chikungunya virus: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249166–e0249166. [Google Scholar]

- S. M. M., O; T. L., B; Mariana, K.; A. R., O; S. V., C; G. T. S., F; P. I. A., D; M. P. S., S; N. L. C., J; C. G., S. Concomitant Transmission of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses in Brazil: Clinical and Epidemiological Findings From Surveillance for Acute Febrile Illness. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, G. R. D.; Jawed, F.; Mukandavire, C.; Deol, A.; Scarponi, D.; Mboera, L. E. G.; Seruyange, E.; Poirier, M. J. P.; Bosomprah, S.; Udeze, A. O. Global burden of chikungunya virus infections and the potential benefit of vaccination campaigns. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. Chikungunya virus disease- Global situation. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON581 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- P. A., M; B. A., C; Y, S.; S. E., G; W, K.; S. J., H; W. S., C. Evolutionary relationships and systematics of the alphaviruses. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 10118–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliya, K.; Olivier, A.; Laurence, B.; Ali, A. New Insights into Chikungunya Virus Infection and Pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2021, 8, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer, J.; René, B.; Marc, T.; Gemma, P.; Andres, M.; Maria, N. E.; Juana, D. CHIKV infection reprograms codon optimality to favor viral RNA translation by altering the tRNA epitranscriptome. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4725–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Peiqi, Y.; Hongjian, Z.; Na, Z.; Xia, J.; Siqi, S.; Shan, G.; Leiliang, Z. Intraviral interactome of Chikungunya virus reveals the homo-oligomerization and palmitoylation of structural protein TF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 513, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yien, L. M. C.; Kuo, Z.; Bia, T. Y.; Mai, N. T.; Dahai, L. Chikungunya virus Non-structural Protein 1 is a versatile RNA capping and decapping enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105415–105415. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhache, W.; Neyret, A.; Bernard, E.; Merits, A.; Briant, L. Palmitoylated Cysteines in Chikungunya Virus nsP1 Are Critical for Targeting to Cholesterol-Rich Plasma Membrane Microdomains with Functional Consequences for Viral Genome Replication. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, A.; Asressu, K.H.; Hossain, M.A.; Brown, P.J.; Nandakumar, M.; Vala, A.; Merten, E.M.; Sears, J.D.; Law, I.; Burdick, J.E.; et al. Structure Activity of β-Amidomethyl Vinyl Sulfones as Covalent Inhibitors of Chikungunya nsP2 Cysteine Protease with Antialphavirus Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 16505–16532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mona, T.; Eva, Ž.; Andres, M. Phosphorylation sites in the hypervariable domain in chikungunya virus nsP3 are crucial for viral replication. J. Virol. 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanni, G.; Niluka, G.; Joseph, W.; Andrew, T.; Mark, H. Multiple roles of the non-structural protein 3 (nsP3) alphavirus unique domain (AUD) during Chikungunya virus genome replication and transcription. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007239. [Google Scholar]

- Bia, T. Y.; Sandra, L. L.; Xin, L.; YeeSong, L.; Congbao, K.; Julien, L.; Jie, Z.; Andres, M.; Dahai, L. Crystal structures of alphavirus nonstructural protein 4 (nsP4) reveal an intrinsically dynamic RNA-dependent RNA polymerase fold. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 1000–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.W.; Tan, Y.B.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lim, B.T.; Cornvik, T.; Lescar, J.; Ng, L.F.P.; Luo, D. Chikungunya virus nsP4 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase core domain displays detergent-sensitive primer extension and terminal adenylyltransferase activities. Antivir. Res. 2017, 143, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, J.A.; Rooney, E.E.; Hardy, R.W. The role of chikungunya virus capsid-viral RNA interactions in programmed ribosomal frameshifting. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0139325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelossi-Cebinelli, G.; Carneiro, J.A.; Yaekashi, K.M.; Bertozzi, M.M.; Bianchini, B.H.S.; Rasquel-Oliveira, F.S.; Zanluca, C.; dos Santos, C.N.D.; Arredondo, R.; Blackburn, T.A.; et al. A Review of the Biology of Chikungunya Virus Highlighting the Development of Current Novel Therapeutic and Prevention Approaches. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S.B.; Sathishkumar, R. Chikungunya infection: A potential re-emerging global threat. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. T., E; v. D.-R. M. K., S; A. N. N., V; A. I., C; v. H. M., J; S. J., M. Dynamics of Chikungunya Virus Cell Entry Unraveled by Single-Virus Tracking in Living Cells. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 4745–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, W.; Eva, B.; Christine, v. R.; Lisa, H.; Eberhard, H.; S. B., S. Identification of Functional Determinants in the Chikungunya Virus E2 Protein. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005318. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Zhao, Z.; Chai, Y.; Jin, X.; Li, C.; Yuan, F.; Liu, S.; Gao, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, J.; et al. Molecular Basis of Arthritogenic Alphavirus Receptor MXRA8 Binding to Chikungunya Virus Envelope Protein. Cell 2019, 177, 1714–1724.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basore, K.; Kim, A.S.; Nelson, C.A.; Zhang, R.; Smith, B.K.; Uranga, C.; Vang, L.; Cheng, M.; Gross, M.L.; Smith, J.; et al. Cryo-EM Structure of Chikungunya Virus in Complex with the Mxra8 Receptor. Cell 2019, 177, 1725–1737.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, Z.; K. A., S; F. J., M; Sharmila, N.; Katherine, B.; K. W., B; Rebecca, R.; F. R., H; Hueylie, L.; Subhajit, P. Mxra8 is a receptor for multiple arthritogenic alphaviruses. Nature 2018, 557, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, D. C.; Sandra, C.; Katleen, V.; Simon, D.; Maarten, D.; Xaveer, V. O.; Dieter, D.; A. K., K.; Koen, B. The CD147 Protein Complex Is Involved in Entry of Chikungunya Virus and Related Alphaviruses in Human Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 615165–615165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielian, M.; Chanel-Vos, C.; Liao, M. Alphavirus Entry and Membrane Fusion. Viruses 2010, 2, 796–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, B.; Maxime, S.; Bernard, G.; Nathalie, C.; Stephen, H.; Christian, D.; Laurence, B. Endocytosis of chikungunya virus into mammalian cells: role of clathrin and early endosomal compartments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11479. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, C.; Lee, R.; Hussain, K.M.; Chu, J.J.H. Macropinocytosis dependent entry of Chikungunya virus into human muscle cells. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumida, M.; Hayashi, H.; Tanaka, A.; Kubo, Y. Cathepsin B Protease Facilitates Chikungunya Virus Envelope Protein-Mediated Infection Via Endocytosis or Macropinocytosis. Viruses 2020, 12, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youichi, S. Interferon-induced restriction of Chikungunya virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2023, 210, 105487–105487. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, F. V. L.; F. G., J.; Inchima, S. U. Interleukin 27 as an inducer of antiviral response against Chikungunya Virus infection in human macrophages. Cell. Immunol. 2021, 367, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Myoung, J. Chikungunya Virus-Encoded nsP2, E2 and E1 Strongly Antagonize the Interferon- ¥Signaling Pathway. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freppel, W.; Silva, L.A.; Stapleford, K.A.; Herrero, L.J. Pathogenicity and virulence of chikungunya virus. Virulence 2024, 15, 2396484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipa, H. S.; Amalina, G. K.; Fern, F.; Anom, B.; Tedjo, S. R.; Craig, S.; B. P., G. Evolution and immunopathology of chikungunya virus informs therapeutic development. Dis. Model. Mech. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosnier, E.; Jaffar-Bandjee, M.-C.; Cally, R.; Dahmane, L.; Frumence, E.; Nguyen, L.B.L.; Manaquin, R.; Vincent, M.; Moiton, M.P.; Gérardin, P.; et al. Fatal Adverse Event After VLA1553 Chikungunya Vaccination in an Elderly Patient: A Case Report From Reunion Island. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongwichit, S.; Chuchaona, W.; Korkong, S.; Wongsrisang, L.; Thongmee, T.; Poovorawan, Y. Chikungunya virus in Thailand (2020–2023): Epidemiology, clinical features, and genomic insights. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, D. P.; Trujillo, S. C.; Narváez, C. F. Clinical, virological, and antibody profiles of overlapping dengue and chikungunya virus infections in children from southern Colombia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013260. [Google Scholar]

- N.B., N; Jayaram, A.; Shetty, U.; Varamballi, P.; Mudgal, P.P.; Suri, V.; Singh, M.P.; Kamaljeet, K.; Agrawal, S.; Kaneria, M.; et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of chikungunya outbreaks during 2019–2022 in India. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasif, A.O.; Haider, N.; Muntasir, I.; Qayum, O.; Hasan, M.N.; Hassan, M.R.; Khan, M.H.; Sultana, S.; Ferdous, J.; Prince, K.T.P.; et al. The reappearance of Chikungunya virus in Bangladesh, 2024. IJID Reg. 2025, 16, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, M.M.N.; Mutua, M.M.; Inoue, S.; Takamatsu, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Urano, T.; Muthugala, R.; Fernando, L.; Hapugoda, M.; Gunawardene, Y.; et al. Molecular and serological evidence of chikungunya virus among dengue suspected patients in Sri Lanka. J. Infect. Public Heal. 2025, 18, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. F. C. P. A. D. M.; Filippis, A. M. B. d.; Moreira, M. E. L.; Campos, S. B. d.; Fuller, T.; Lopes, F. C. R.; Brasil, P. Perinatal and Neonatal Chikungunya virus Transmission: a case series. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mewara, I.; Chaurasia, D.; Kapoor, G.; Perumal, N.; Bundela, H.P.S.; Dube, S.; Agarwal, A.; Iv, D.C. Insights Into the Seroprevalence, Clinical Spectrum, and Laboratory Features of Dengue and Chikungunya Mono-Infections vs. Co-infections During 2022–2023. Cureus 2025, 17, e92410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonanek, A.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Phongsamart, W.; Lapphra, K.; Rungmaitree, S.; Horthongkham, N.; Wittawatmongkol, O. Re-emerging outbreaks of chikungunya virus infections of increased severity: A single-center, retrospective analysis of atypical manifestations in hospitalized children during the 2019 outbreak in Bangkok, Thailand. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0330527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajith, A.; Iyengar, V.; Varamballi, P.; Mukhopadhyay, C.; Nittur, S. Diagnostic utility of real-time RT-PCR for chikungunya virus detection in the acute phase of infection: a retrospective study. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2523559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaguth, O.E.T.; Buddle, S.; Morfopoulou, S.; Breuer, J. Clinical metagenomics for diagnosis and surveillance of viral pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 24, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, A.; Flacco, M.E.; Cioni, G.; Tiseo, M.; Imperiali, G.; Bianconi, A.; Fiore, M.; Calò, G.L.; Orazi, V.; Troia, A.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of Chikungunya Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2024, 12, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S.L.; Ferguson, D.; Ham, C.; Hall, J.; Jenkins, A.; Giles, E.; Priestnall, S.L.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; Roques, P.; Le Grand, R.; et al. Inactivated Viral Vaccine BBV87 Protects Against Chikungunya Virus Challenge in a Non-Human Primate Model. Viruses 2025, 17, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milena, H. L.; K, S.; Sushant, S.; JeanLouis, E.; Sonali, K.; S. E., R; Marc, G.; C. R., T. A Brighton Collaboration standardized template with key considerations for a benefit/risk assessment for an inactivated viral vaccine against Chikungunya virus. Vaccine 2022, 40, 5263–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzer, A.; Suhrbier, A.; Hugo, L.E.; Tang, B.; Devine, G.; Jost, S.; Meinke, A.L. Assessment of the transmission of live-attenuated chikungunya virus vaccine VLA1553 by Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosulin, K.; Brasel, T.L.; Smith, J.; Torres, M.; Bitzer, A.; Dubischar, K.; Buerger, V.; Mader, R.; Weaver, S.C.; Beasley, D.W.; et al. Cross-neutralizing activity of the chikungunya vaccine VLA1553 against three prevalent chikungunya lineages. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2469653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, G.; Buerger, V.; Senn, J. L.; Erlsbacher, D. I. F.; Dubischar, K.; Lingelbach, S. E.; Jaramillo, J. C. Pooled safety evaluation for a new single-shot live-attenuated chikungunya vaccine. J. Travel Med 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.H.; Fritzer, A.; Hochreiter, R.; Dubischar, K.; Meyer, S. From bench to clinic: the development of VLA1553/IXCHIQ, a live-attenuated chikungunya vaccine. J. Travel Med. 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, H. Ixchiq (VLA1553): The first FDA-approved vaccine to prevent disease caused by Chikungunya virus infection. Virulence 2024, 15, 2301573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, H.; Maria, K.; Aleksei, L.; K. B., M; J. D., X; Margit, M.; Valeria, L.; F. J., K; Pierre, R.; Roger, L. G. Novel attenuated Chikungunya vaccine candidates elicit protective immunity in C57BL/6 mice. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Liu, X.; Zaid, A.; Goh, L.Y.H.; Hobson-Peters, J.; Hall, R.A.; Merits, A.; Mahalingam, S. Mutation of the N-Terminal Region of Chikungunya Virus Capsid Protein: Implications for Vaccine Design. mBio 2017, 8, e01970-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyratne, E.; Freitas, J.R.; Zaid, A.; Mahalingam, S.; Taylor, A. Attenuation and Stability of CHIKV-NoLS, a Live-Attenuated Chikungunya Virus Vaccine Candidate. Vaccines 2018, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambhavi, R.; Eranga, A.; F. J., R; Chenying, Y.; Kothila, T.; Helen, M.; Xiang, L.; Mehfuz, Z.; Suresh, M.; Ali, Z. A booster regime of liposome-delivered live-attenuated CHIKV vaccine RNA genome protects against chikungunya virus disease in mice. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3976–3988. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, S. J. P. d.; Passos, C. M. d.; Zaki, P. S.; Renaux, H. V.; Lima, N. D. F. d.; Andrade, Z. P. M. d. Chikungunya Virus E2 Structural Protein B-Cell Epitopes Analysis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1839–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataru, A.; Zhi-Yong, Y.; Hanne, A.; Siyang, S.; H. H., A; Wing-Pui, K.; L. M., G; Stephen, H.; R. M., G; Srinivas, R. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 334–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimkunya vaccine approved to prevent disease caused by the chikungunya virus in people 12 years of age and older. M2 Presswire 2025.

- Richardson, J.S.; Anderson, D.M.; Mendy, J.; Tindale, L.C.; Muhammad, S.; Loreth, T.; Tredo, S.R.; Warfield, K.L.; Ramanathan, R.; Caso, J.T.; et al. Chikungunya virus virus-like particle vaccine safety and immunogenicity in adolescents and adults in the USA: a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Camacho, C.; Kim, Y.C.; Blight, J.; Moreli, M.L.; Montoya-Diaz, E.; Huiskonen, J.T.; Kümmerer, B.M.; Reyes-Sandoval, A. Assessment of Immunogenicity and Neutralisation Efficacy of Viral-Vectored Vaccines Against Chikungunya Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandler, S.; Ruffié, C.; Combredet, C.; Brault, J.-B.; Najburg, V.; Prevost, M.-C.; Habel, A.; Tauber, E.; Desprès, P.; Tangy, F. A recombinant measles vaccine expressing chikungunya virus-like particles is strongly immunogenic and protects mice from lethal challenge with chikungunya virus. Vaccine 2013, 31, 3718–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. S., L; C. J., E; Eryu, W.; A. S., R; L. W., S; P. J., A; Katrin, R.; Sabrina, S.; W. S., C. Immunogenicity and Efficacy of a Measles Virus-Vectored Chikungunya Vaccine in Nonhuman Primates. J.Infect.Dis 2019, 220, 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, T.; Pierre, V. D.; Clara, G.; Ilse, D. C.; Mathieu, M.; Stephanie, R.; Alexandra, J.; Yvonne, T.; Kanchanamala, W.; Denise, H. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of a recombinant measles-vectored Lassa fever vaccine: a randomised, placebo-controlled, first-in-human trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus, J.H.; Auguste, A.J.; Kaelber, J.T.; Luo, H.; Rossi, S.L.; Fenton, K.; Leal, G.; Kim, D.Y.; Chiu, W.; Wang, T.; et al. A chikungunya fever vaccine utilizing an insect-specific virus platform. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadalkareem, A.; Huanle, L.; O. S., R; Binbin, W.; R. C., M; A. A., J; P. K., S; BiHung, P.; Saravanan, T.; F. E., I. Optimized production and immunogenicity of an insect virus-based chikungunya virus candidate vaccine in cell culture and animal models. Emerging Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, N.; Gustavo, P.; G. R., V; Hilda, G.; Travassos, D. R. A. P.; Nazir, S.; P. V., L; S. M., B; Ian, L. W.; T. R., B. Eilat virus, a unique alphavirus with host range restricted to insects by RNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 14622–7. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, A.; Woolsey, C.; Lu, H.; Plante, K.; Wallace, S.M.; Rodriguez, L.; Shinde, D.P.; Cui, Y.; Franz, A.W.E.; Thangamani, S.; et al. A safe insect-based chikungunya fever vaccine affords rapid and durable protection in cynomolgus macaques. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. C., A; Allison, A.; Stephan, B.; Jackson, B. P.; Conor, K.; Trevor, B.; W. S., C; HongHong, Z.; Lori, P. A phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an mRNA-based chikungunya virus vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3898–3906. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, S.L.; A Sutter, R.; Miller, E.R.; Asturias, E.J.; Chen, L.H.; Bell, B.P.; McNeil, M.M.; Rakickas, J.; Wharton, M.; Meyer, S.; et al. Surveillance for adverse events following use of live attenuated chikungunya vaccine, United States, 2024, and the associated public health response in 2024 and 2025. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikungunya vaccine (Ixchiq): temporary contraindication in adults aged ≥ 65 years lifted. Reactions Weekly 2025, 2078, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Eranga, A.; Kothila, T.; F. J., R; Helen, M.; Suresh, M.; Ali, Z.; Mehfuz, Z.; Adam, T. Liposomal Delivery of the RNA Genome of a Live-Attenuated Chikungunya Virus Vaccine Candidate Provides Local, but Not Systemic Protection After One Dose. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haese, N.; Powers, J.; Streblow, D. N. Small Molecule Inhibitors Targeting Chikungunya Virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2022, 435, 107–139. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, D.O.S.; Santos, I.d.A.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Grosche, V.R.; Jardim, A.C.G. Antivirals Against Chikungunya Virus: Is the Solution in Nature? Viruses 2020, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phitchayapak, W.; Frédéric, T.; Christine, B.; Sittiruk, R.; Sukathida, U.; Laurent, D.; S. D., R. Assessment of flavaglines as potential chikungunya virus entry inhibitors. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 59, 129–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L., H. F. I.; J., B. J., Current and Promising Antivirals Against Chikungunya Virus. Front.Public Health 2020, 8, 618624–618624. [CrossRef]

- Albulescu, I.C.; White-Scholten, L.; Tas, A.; Hoornweg, T.E.; Ferla, S.; Kovacikova, K.; Smit, J.M.; Brancale, A.; Snijder, E.J.; van Hemert, M.J. Suramin Inhibits Chikungunya Virus Replication by Interacting with Virions and Blocking the Early Steps of Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnabi, R.; Neyts, J.; Delang, L. Towards antivirals against chikungunya virus. Antivir. Res. 2015, 121, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, H.; Simon, B.; Tatjana, W.; Nadine, B.; Katja, S.; Christopher, W.; Stephan, B.; S. B., S. Suramin is a potent inhibitor of Chikungunya and Ebola virus cell entry. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, K.; S. S., R; Mugdha, T.; L. R. P., V; Manmohan, P. Assessment of in vitro prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of chloroquine against Chikungunya virus in vero cells. J. Med. Virol. 2010, 82, 817–24. [Google Scholar]

- Calmon, M.F.; Gusmão, L.A.; Ruiz, T.F.R.; Campos, G.R.F.; Ayusso, G.M.; Carvalho, T.; Bortolato, I.D.V.F.; Conceição, P.J.P.; Taboga, S.R.; Jardim, A.C.G.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Liposomes Containing Natural Compounds Against CHIKV. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. F., S; Bastian, T.; Naqiah, A. S.; Diane, S.; Kai, R.; N. T., A; Andres, M.; M. G., M; N. L. F., P; Tero, A. The Antiviral Alkaloid Berberine Reduces Chikungunya Virus-Induced Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9743–9757. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, F.S.; Kaukinen, P.; Gläsker, S.; Bespalov, M.; Hanski, L.; Wennerberg, K.; Kümmerer, B.M.; Ahola, T. Discovery of berberine, abamectin and ivermectin as antivirals against chikungunya and other alphaviruses. Antivir. Res. 2016, 126, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verena, B.; Ernst, U.; Thierry, L. Antivirals against the Chikungunya Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1307–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feibelman, K.M.; Fuller, B.P.; Li, L.; LaBarbera, D.V.; Geiss, B.J. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of the Chikungunya virus nsP1 RNA capping enzyme. Antivir. Res. 2018, 154, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]