Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heugens, E.H.; Hendriks, A.J.; Dekker, T.; van Straalen, N.M.; Admiraal, W. A review of the effects of multiple stressors on aquatic organisms and analysis of uncertainty factors for use in risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol 2001, 31(3), 247-84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.P.; McIntyre, P.J.; Angert, A.L.; Rice, K.J. Evolution and ecology of species range limits. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 2009, 40, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Canedo-Arguelles, M.; Entrekin, S.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Padisák, J. Effects of induced changes in salinity on inland and coastal water ecosystems. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850(20), 4343–4688. [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy, Z.; Abril, M.; Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Espinosa, C.; Vendrell-Puigmitja, L.; Proia, L. Experimental assessment of salinization effects on freshwater zooplankton communities and their trophic interactions under eutrophic conditions. Environmental Pollution 2022, 313, 120127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Yuan, Z.; Mao, X.; Ma, T. Salinity levels, trends and drivers of surface water salinization across China’s river basins. Water Research 2025, 281, 123556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.A.M.; Henry, N.; Canals, O.; Consing, G.; Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N.; Lewandowska, A.M. DNA Metabarcoding as a tool to study plankton responses to warming and salinity change in mesocosms. Ecology and Evolution 2025, 15, e72125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Loewen, C.J.G.; Jackson, D.A. Zooplankton diversity in highly urbanized ponds: The role of road salt is not reflected by watershed impervious cover. Limnol Oceanogr in press, 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, L.N.H.; Schipper, A.M.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Van der Velde, G.; Leuven, R.S.E.W. Sensitivity of native and non-native mollusc species to changing river water temperature and salinity. Biol Invasions 2012, 14, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J. Zooplankton associations in East African lakes spanning a wide salinity range. In Saline Lakes V. Developments in Hydrobiology 87; Hurlbert, S.H., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, R.; Randall, D.; August ines, G. Fisiología animal. Mecanismos y Adaptaciones. Interamericana; McGraw-Hill, 1989; p. 650 p. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.L.; Snell, T.W.; Walsh, E.J.; Sarma, S.S.S.; Segers, H. Chapter 8. Phylum Rotifera. Keys to Palaearctic Fauna. In Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates. Volume IV. Fourth Edition; Academic Press/Elsevier, 2019; pp. 219–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koste, W. Rotatoria. Die Rädertiere Mitteleuropas. Ein Bestimmungswerk begründet von Max Voigt Textband 673 pp., Vol. 2: Tafelband 234 pp; Bornträger: Stuttgart, 1978; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Elguea-Sánchez, B.; Nandini, S. Effect of salinity on competition between the rotifers Brachionus rotundiformis Tschugunoff and Hexarthra jenkinae (De Beauchamp) (Rotifera). Hydrobiologia 2002, 474, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.D. The biology of temporary ponds; Oxford University Press: London, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cunillera-Montcusí, D.; Beklioğlu, M.; Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Jeppesen, E.; Ptacnik, R.; Amorim, C.A.; Arnott, S.E.; Berger, S.A.; Brucet, S.; Dugan, H.A.; et al. Freshwater salinisation: A research agenda for a saltier world. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2022, 37, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S.; Morales-Ventura, J.; Delgado-Martínez, I.; González-Valverde, L. Effects of NaCl salinity on the population dynamics of freshwater zooplankton (rotifers and cladocerans). Aquatic Ecology 2006, 40, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Kefford, B.; Schäfer, R. Salt in freshwaters: Causes, effects and prospects - introduction to the theme issue. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018, 374(1764), 20180002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bielańska-Grajner, I.; Cudak, A. Effects of salinity on species diversity of rotifers in anthropogenic water bodies. Pol J Environ Stud 2014, 23, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S. Comparative population dynamics of six brachionid rotifers (Rotifera) fed seston from a hypertrophic, high altitude shallow waterbody from Mexico. Hydrobiologia 2019, 844(1), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, S.E.; Fugère, V.; Symons, C.C.; Melles, S.J.; Beisner, B.E.; Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Hébert, M.-P.; Brentrup, J.A.; Downing, A.L.; Gray, D.K.; et al. Widespread variation in salt tolerance within freshwater zooplankton species reduces the predictability of community-level salt tolerance. Limnology and Oceanography Letters 2023, 8, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholssi, R.; Stefanova, S.; González-Ortegón, E.; Araújo, C.V.M.; Moreno-Garrido, I. Population and functional changes in a multispecies co-culture of marine microalgae and cyanobacteria under a combination of different salinity and temperature levels. Marine Environmental Research 2024, 193, 106279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huys, R.; Boxshall, G.A. Copepod Evolution. Ray Society Monographs 1991, 159, 468 pages. [Google Scholar]

- McClymont, A.; Arnott, S.E.; Rusak, J.A. Interactive effects of increasing chloride concentration and warming on freshwater plankton communities. Limnology and Oceanography Letters 2023, 8, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorini, V.; Garrido, M.; Malet, N.; Simon, L.; Alonso, L.; Bastien, R.; Aiello, A.; Cecchi, P.; Pasqualini, V. Response of phytoplankton communities to variation in salinity in a small Mediterranean coastal lagoon: Future management and foreseen climate change consequences. Water 2023, 15(18), 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 20th ed.; Washington, DC, 1998. [Google Scholar]

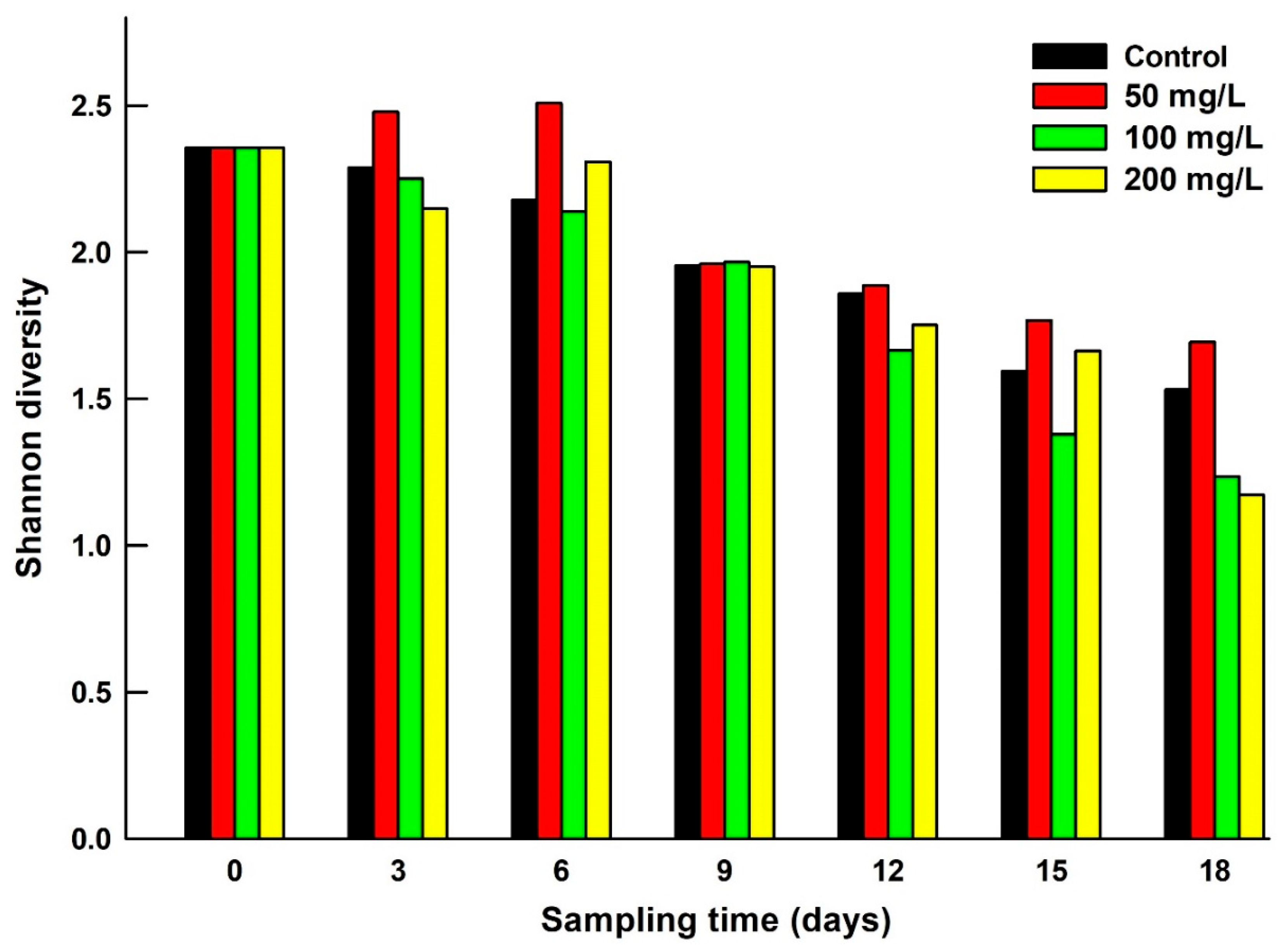

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

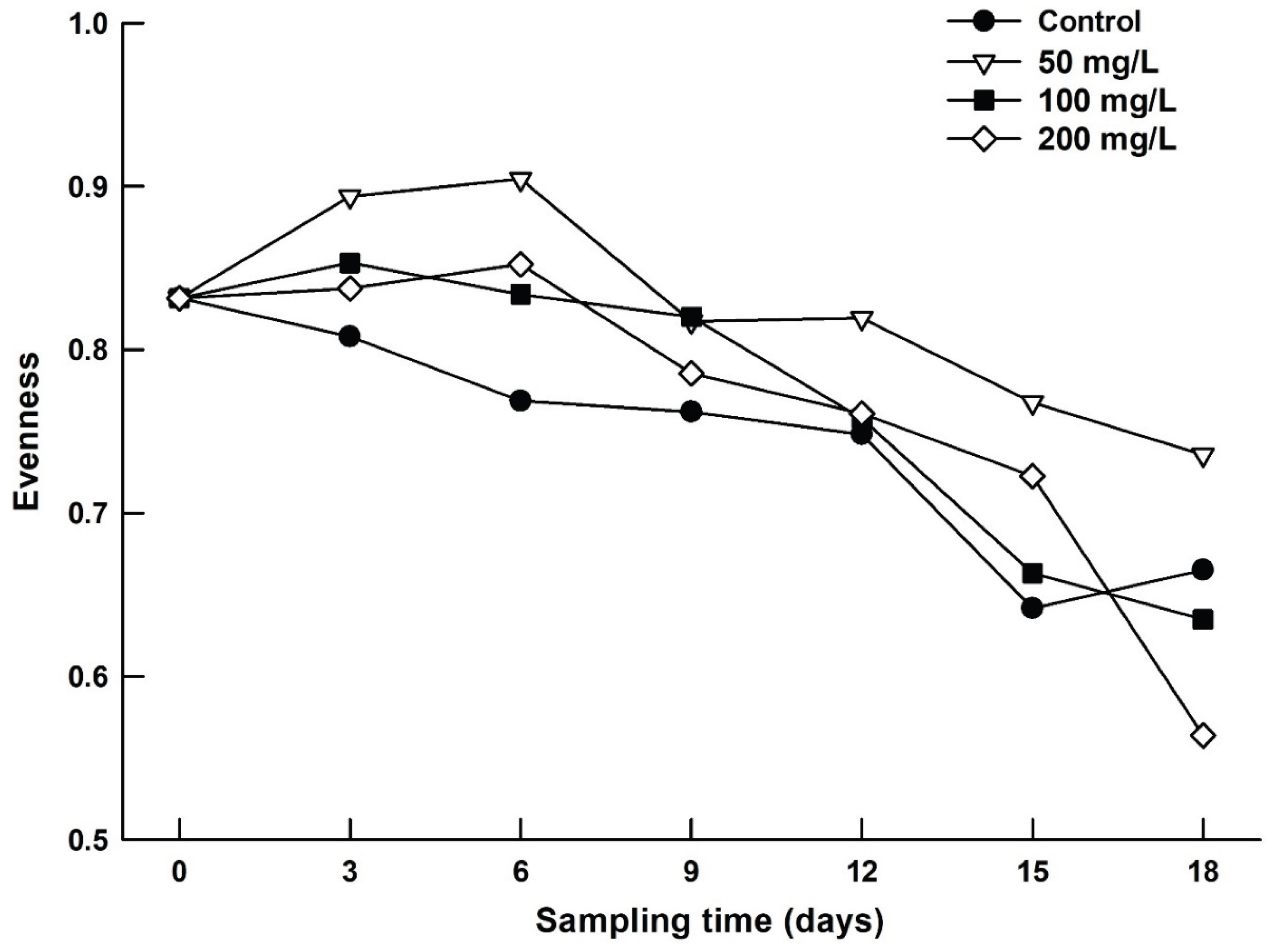

- Pielou, E.C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1996, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.R.; Hossain, M.B.; Sarker, M.M.; Nur, A.-A.U.; Habib, A.; Paray, B.A.; Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Gulnaz, A.; Arai, T. Diversity and community structure of zooplankton in homestead ponds of a tropical coastal area. Diversity 2022, 14(9), 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wan, X.; Bai, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, L.; Feng, J. Cd indirectly affects the structure and function of plankton ecosystems by affecting trophic interactions at environmental concentrations. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 480, 136242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, D.G.; Cumming, B.F.; Watters, C.E.; Smol, J.P. The relationship between zooplankton, conductivity and lake water ionic composition in 111 lakes from the Interior Plateau of British Columbia. Canadian International Journal Salt Lake Research 1996, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echaniz, S.; Vignatti, A.; José de Paggi, S.; Paggi, J.; Pilati, A. Zooplankton seasonal abundance of South American saline shallow lakes. International Review of Hydrobiology 2006, 91, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.M.; Hall, C.A.M. Zooplankton dominance shift in response to climate-driven salinity change: A mesocosm study. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 861297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indy, J.R.; Delgadillo, S.P.; Rodriguez, L.A.; Couturier, G.M.; Segers, H.; González, C.A.Á.; Sánchez, W.M.C. Freshwater rotifer: (part II) a laboratory study of native freshwater rotifers Brachionus angularis and B. quadridentatus brevispinus from Tabasco. Kuxulkab’ Revista de Divulgación 2012, 1, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorina-Sakharova, K.; Liashenko, A.; Marchenko, I. Effects of Salinity on the Zooplankton Communities in the Fore-Delta of Kyliya Branch of the Danube River. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 2014, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Contreras, J.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S.S.S. Diversity of Rotifera (Monogononta) and egg ratio of selected taxa in the canals of Xochimilco (Mexico City). Wetlands 2018, 38, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolak, R.; Walsh, E.J. Rotifer species richness in Kenyan waterbodies: Contributions of environmental characteristics. Diversity 2022, 14, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, W.D.; Jones, D.K.; Relyea, R.A. Evolved tolerance to freshwater salinization in zooplankton: Life-history trade-offs, cross-tolerance and reducing cascading effects. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2018, 374(1764), 20180012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvålseth, T.O. Evenness indices once again: Critical analysis of properties. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling | Variable | Control | 50 mg/L | 100 mg/L | 200 mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 days | pH | 9.23±0.07 | 9.23±0.07 | 9.23±0.07 | 9.23±0.07 |

| Cond. | 1749.80±15.7 | 1749.80±15.7 | 1749.80±15.7 | 1749.80±15.66 | |

| PO4 | 1.17±0.07 | 1.17±0.07 | 1.17±0.07 | 1.17±0.07 | |

| Chl a | 119.74±16.5 | 119.74±16.5 | 119.74±16.5 | 119.74±16.5 | |

| 3 days | pH | 9.53±0.03 | 9.53±0.03 | 9.37±0.03 | 9.43±0.03 |

| Cond. | 456.33±22.34 | 813.67±17.32 | 1101.00±2.65 | 1538.00±43.1 | |

| PO4 | 1.35±0.03 | 1.30±0.20 | 0.80±0.01 | 0.50±0.12 | |

| Chl a | 85.01±31.92 | 99.12±8.90 | 120.58±26.28 | 100.60±16.47 | |

| 6 days | pH | 9.23±0.07 | 9.10±0.06 | 9.13±0.03 | 9.17±0.03 |

| Cond. | 586.00±26.50 | 910.00±7.21 | 1336.00±44.2 | 1926.33±19.75 | |

| PO4 | 0.65±0.10 | 0.78±0.01 | 0.86±0.10 | 0.99±0.29 | |

| Chl a | 113.51±17.37 | 120.52±15.95 | 123.65±21.41 | 101.09±27.06 | |

| 9 days | pH | 9.03±0.03 | 8.90±0.06 | 8.83±0.03 | 9.00±0.80 |

| Cond. | 627±35.68 | 940.00±6.43 | 1528.67±29.2 | 1740.00±87.18 | |

| PO4 | 0.30±0.03 | 0.52±0.02 | 0.53±0.03 | 0.50±0.02 | |

| Chl a | 47.24±6.76 | 85.82±29.75 | 56.30±10.10 | 63.46±6.80 | |

| 12 days | pH | 8.43±0.17 | 8.47±0.03 | 8.47±0.03 | 8.57±0.03 |

| Cond. | 626.33±45.69 | 954.33±40.99 | 1498.67±62.3 | 1850.00±90.47 | |

| PO4 | 0.20±0.03 | 0.22±0.15 | 0.33±0.04 | 0.33±0.13 | |

| Chl a | 25.37±5.68 | 53.24±13.21 | 32.43±7.38 | 58.55±13.82 | |

| 15 days | pH | 8.47±0.09 | 8.47±0.03 | 8.47±0.03 | 8.50±0.75 |

| Cond. | 788.00±31.53 | 1201±25.32 | 1990.00±10.0 | 2000.00±35.00 | |

| PO4 | 0.20±0.03 | 0.21±0.01 | 0.33±0.04 | 0.33±0.13 | |

| Chl a | 23.92±10.85 | 53.99±11.94 | 44.22±6.19 | 40.43±6.52 | |

| 18 days | pH | 7.76±0.03 | 7.83±0.03 | 7.83±0.03 | 7.70±0.06 |

| Cond. | 735.00±21.03 | 1115.00±43.4 | 1757.67±53.7 | 1900.00±100.0 | |

| PO4 | 0.35±0.07 | 0.54±0.06 | 0.34±0.02 | 0.41±0.02 | |

| Chl a | 23.92±10.85 | 54.00±12.00 | 44.00±6.20 | 40.42±65.24 |

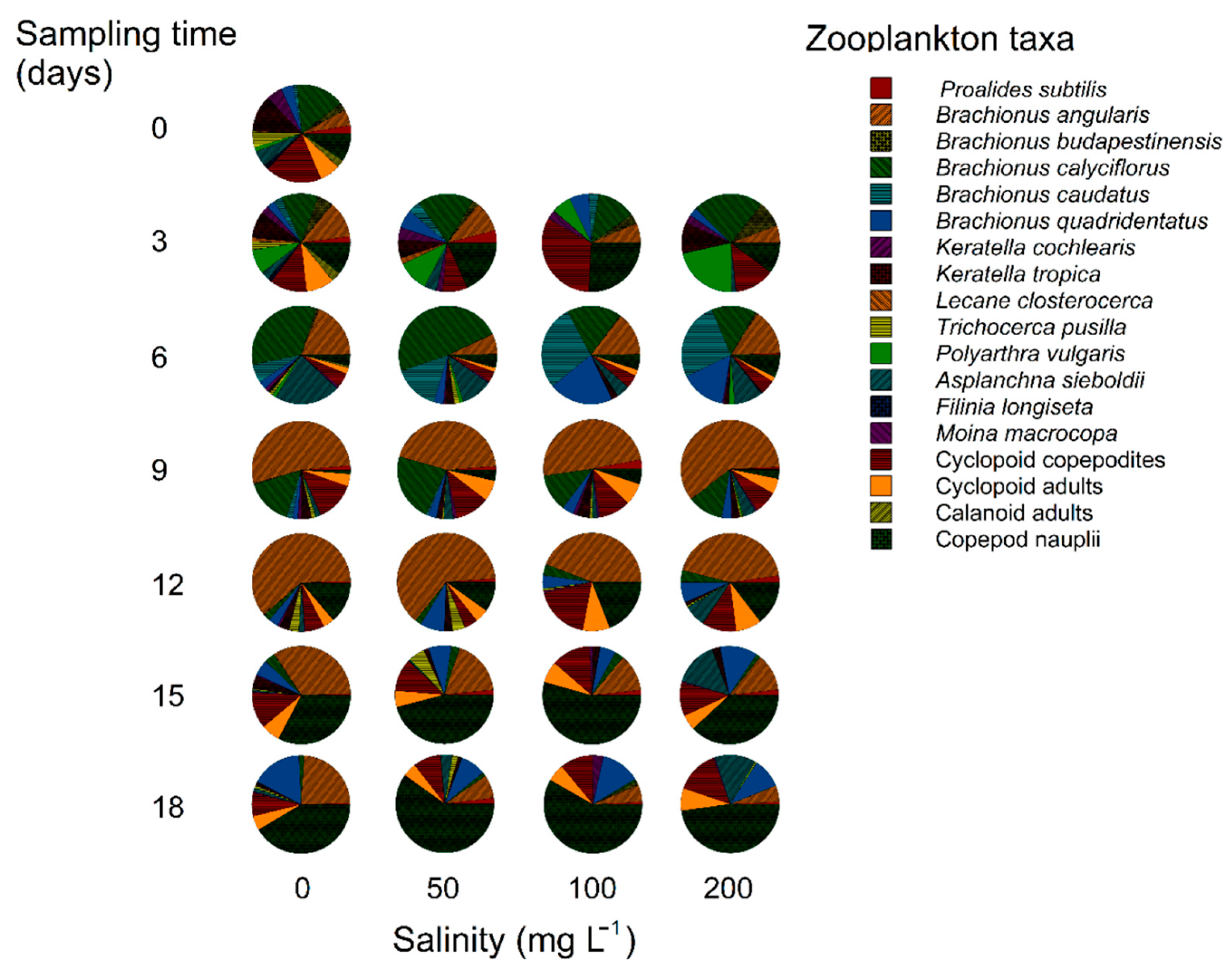

| Rotifera Family: Epiphanidae Proalides subtibilis Rodewald, 1940 Family: Brachionidae Brachionus angularis Gosse, 1851 B. budapestinensis Daday, 1885 B. calyciflorus Pallas, 1766 B. caudatus Barrois & Daday, 1894 B. quadridentatus Hermann, 1783 Keratella cochlearis (Gosse, 1851) K. tropica (Apstein, 1907) Family: Lecanidae Lecane closterocerca (Schmarda, 1859) Family: Trichocercidae Trichocerca pusilla (Hauer, 1929) Family: Synchaetidae Polyarthra vulgaris Carlin, 1943 Family: Asplanchnidae Asplanchna sieboldii (Leydig, 1854) Filiniidae Filinia longiseta (Ehrenberg, 1834) Cladocera Family: Moinidae Moina macrocopa (Straus, 1820) Copepoda Family: Cyclopidae Acanthocyclops americanus (Marsh, 1893) Family: Diaptomidae Arctodiaptomus dorsalis (Marsh, 1907) |

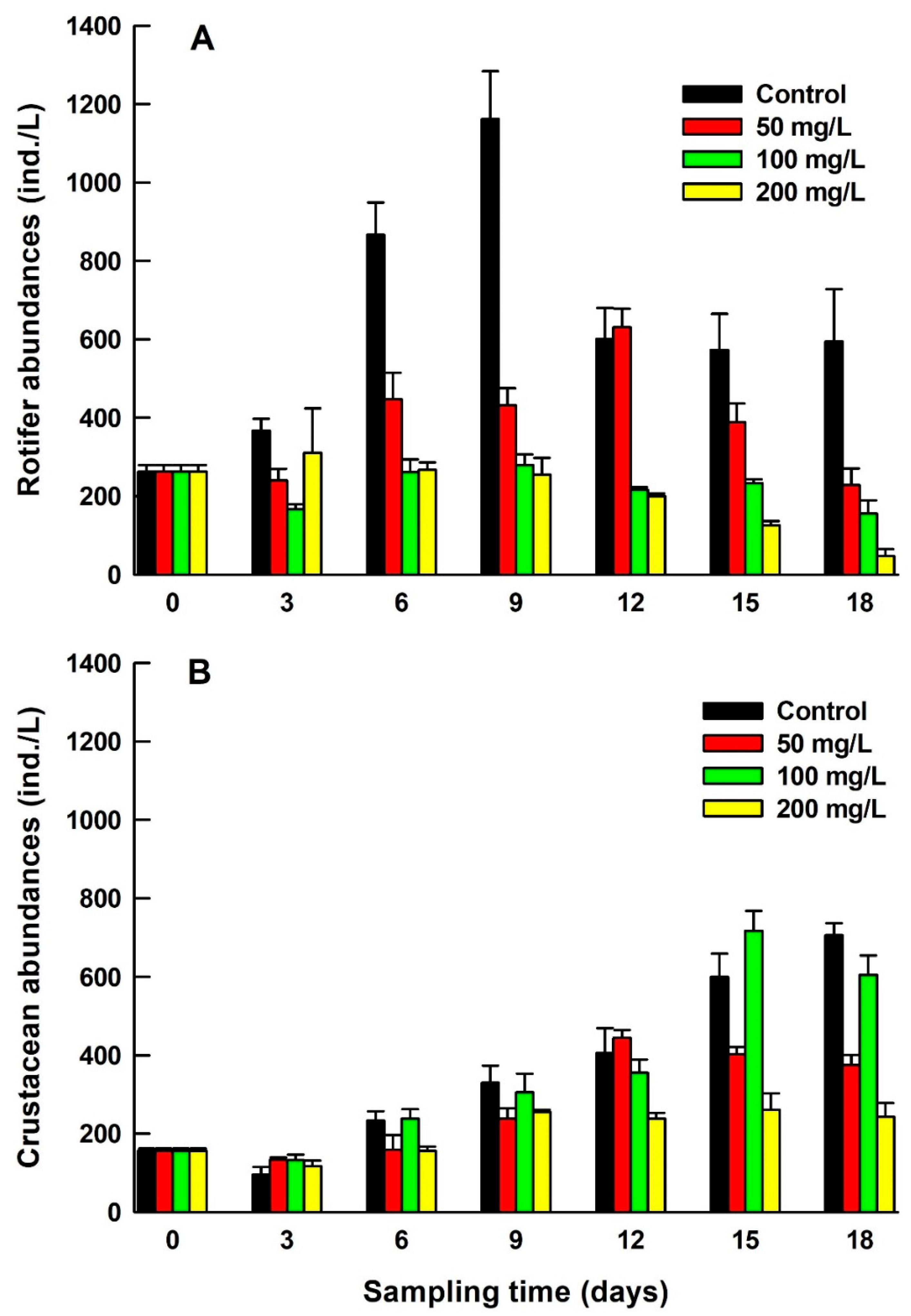

| Source of Variation | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total rotifer abundances | |||||

| Salinity level (A) | 3 | 2419573.99 | 806524.66 | 85.05 | <0.001 |

| Exposure time (B) | 6 | 859321.67 | 143220.27 | 15.1 | <0.001 |

| Interaction of A x B | 18 | 1365595.73 | 75866.43 | 8.00 | <0.001 |

| Error | 56 | 531012.33 | 9482.36 | ||

| Total crustacean abundances | |||||

| Salinity level (A) | 3 | 358356.75 | 119452.25 | 40.32 | <0.001 |

| Exposure time (B) | 6 | 1670145.45 | 278357.57 | 93.97 | <0.001 |

| Interaction of A x B | 18 | 521186.87 | 28954.82 | 9.77 | <0.001 |

| Error | 56 | 165871.51 | 2961.99 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).