Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

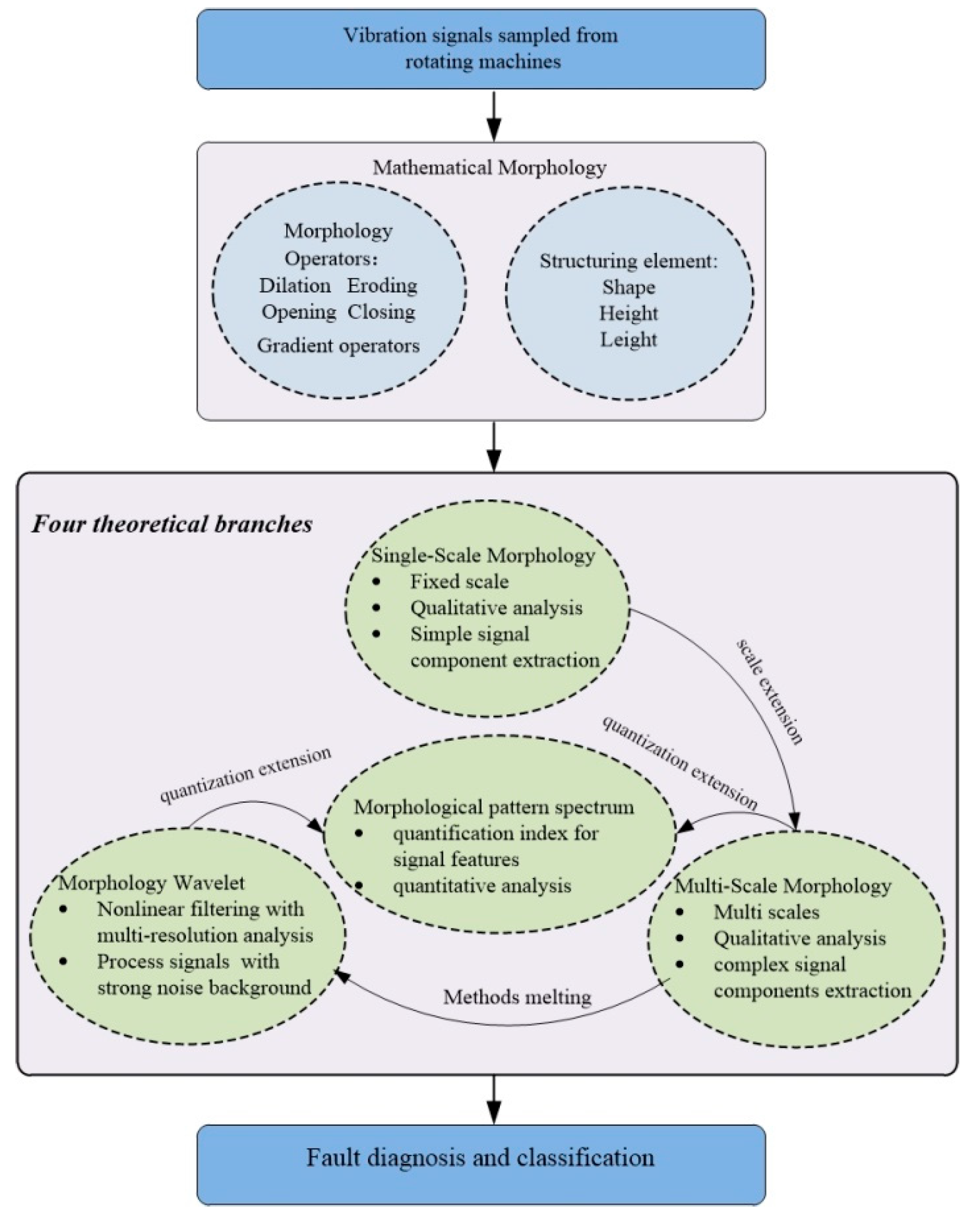

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Morphology

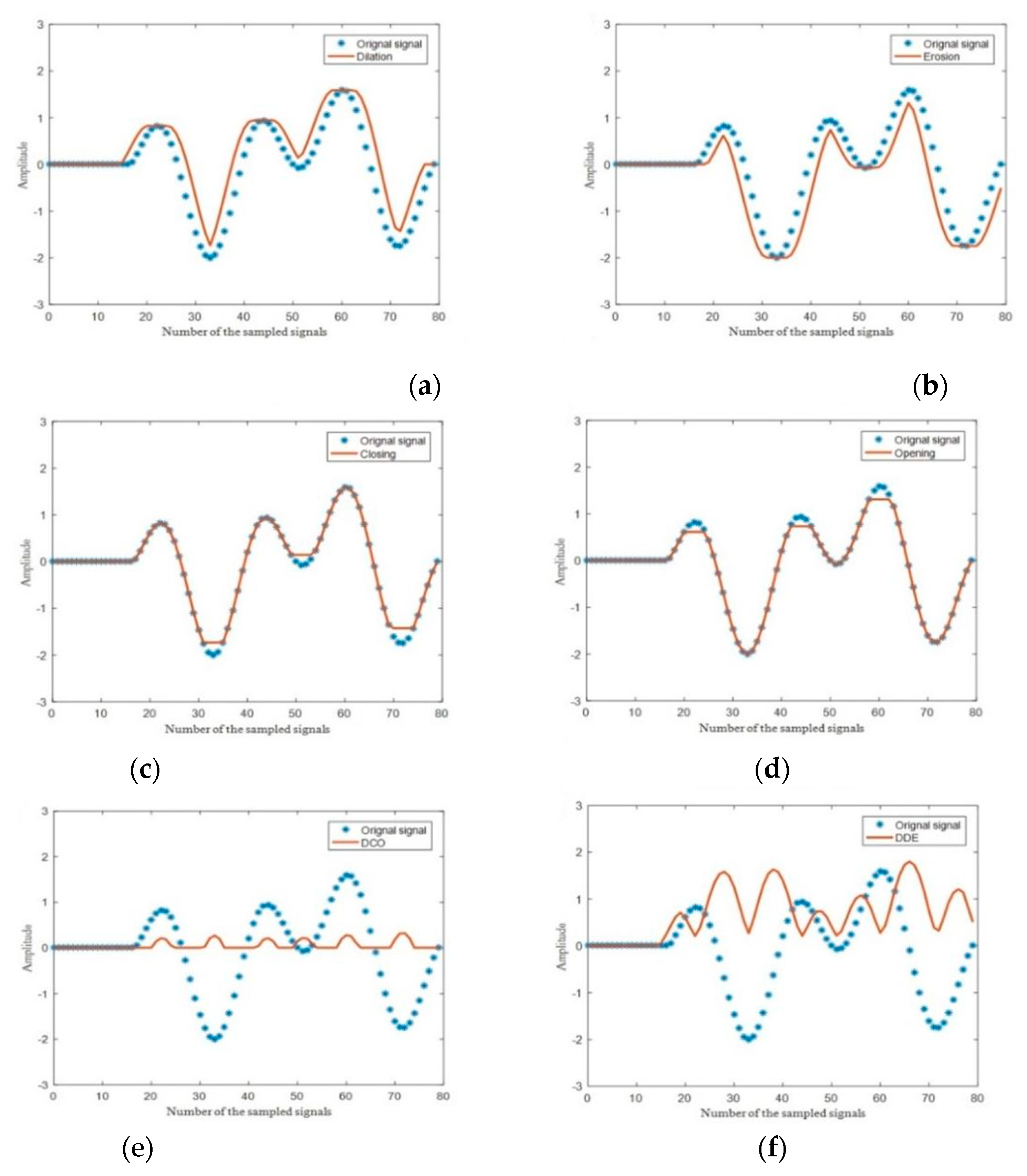

2.1. Morphological Operator

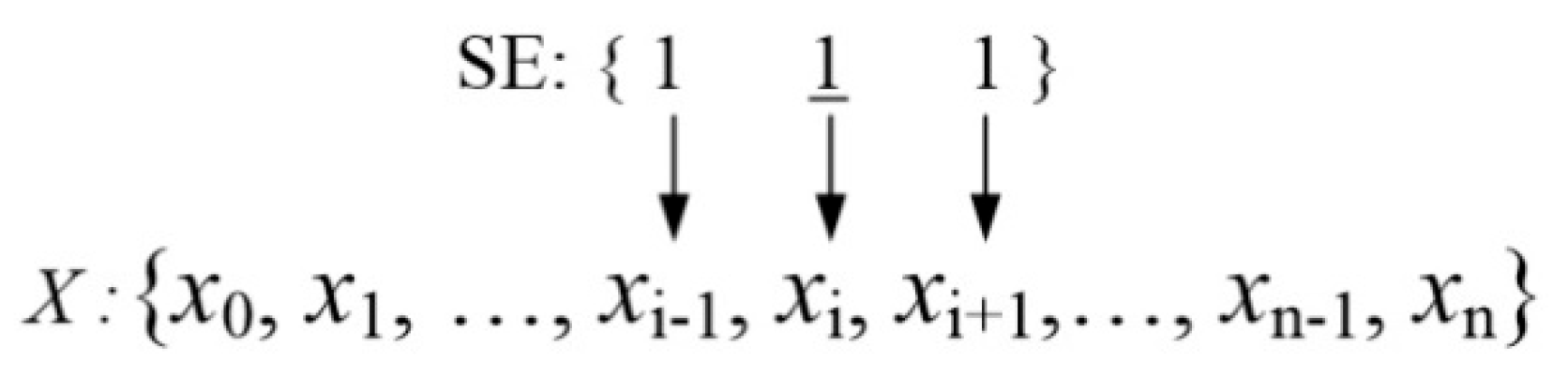

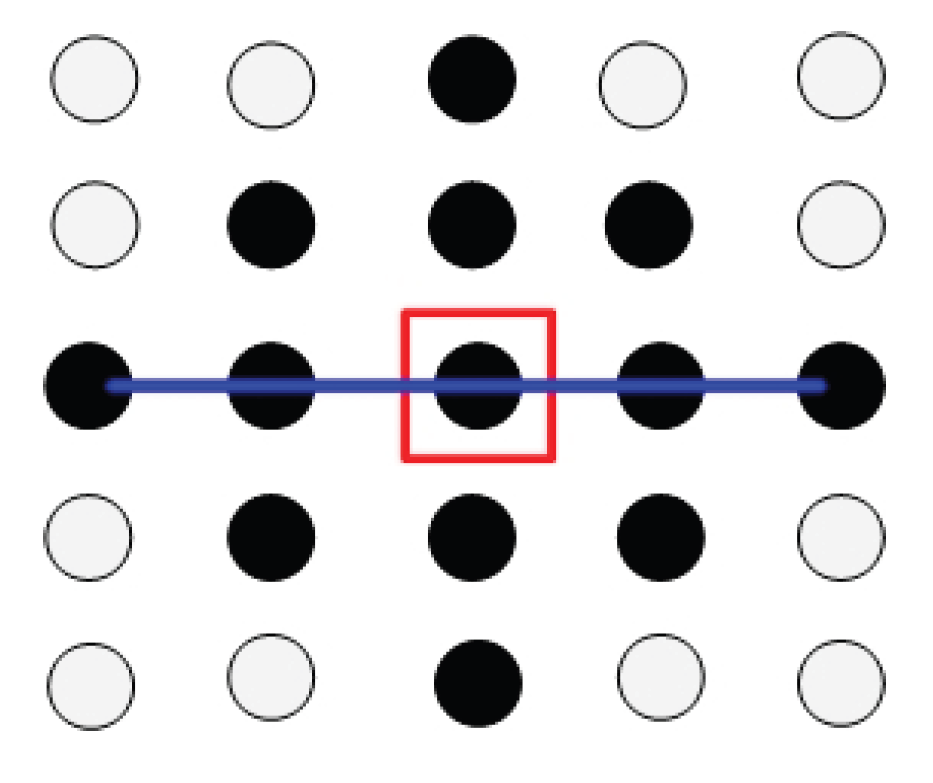

2.2. Structuring Element

2.3. Introduction to Morphology-Based Methods

2.3.1. Single-Scale Morphology

2.3.2. Multi-Scale Morphology

2.3.3. Morphological Pattern Spectrum

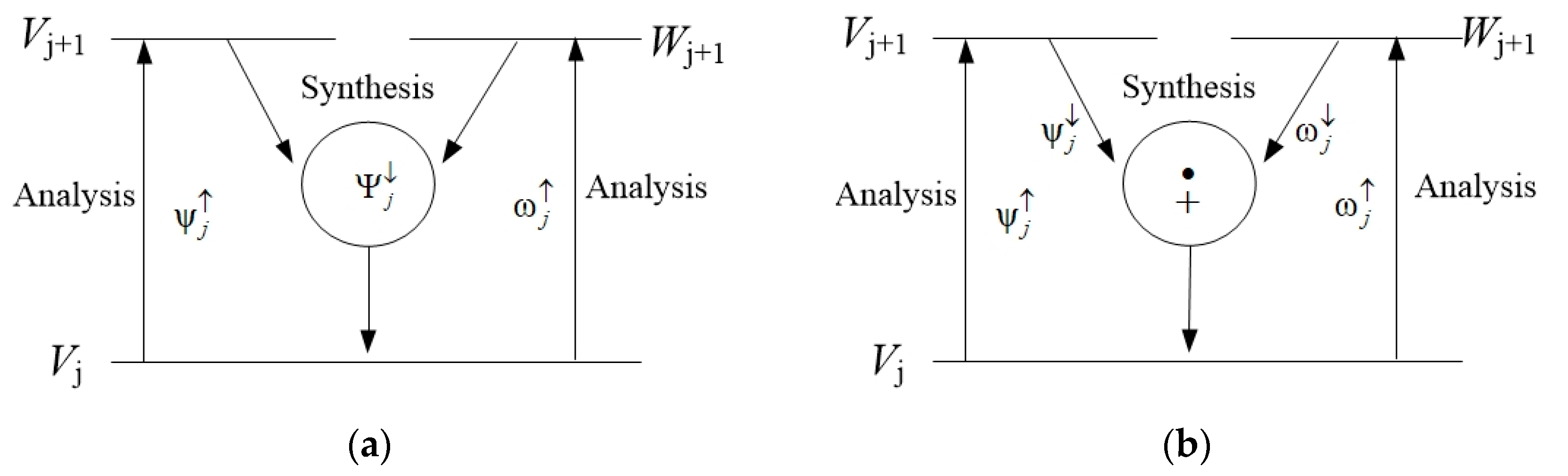

2.3.4. Morphological Wavelet

3. Application of Mathematical Morphology to Rotating Machine

3.1. Single-Scale Morphology-Based Rotating Parts Fault Diagnosis

3.1.1. SSM to Detect Bearing Defect

3.1.2. SSM to Detect Gear Defect

3.2. Multi-Scale Morphology-Based Rotating Parts Fault Diagnosis

3.2.1. MSM to Detect Bearing Defect

3.2.2. MSM to Detect Gear Defect

3.3. Morphological Pattern Spectrum-Based Rotating Parts Fault Diagnosis

3.3.1. MPS to Detect Bearing Defect

3.3.2. MPS to Detect Gear Defect

3.4. Morphological Wavelet -Based Rotating Parts Fault Diagnosis

3.4.1. MW to Detect Bearing Defect

3.4.2. MW to Detect Gear Defect

3.5. Morphology-Based Methods to Other Mechanical Defective Objects

3.6. Comparison and Analysis of Operators and SE in Applications

3.6.1. Morphology Operator Analysis

3.6.2. Structuring Element Analysis

4. Discussion and Development Orientation

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jardine, A.K.S.; Lin, D.; Banjevic, D. A Review on Machinery Diagnostics and Prognostics Implementing Condition-Based Maintenance. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2006, 20, 1483–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Huang, W. A Review of Early Fault Diagnosis Approaches and Their Applications in Rotating Machinery. Entropy 2019, 21, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, D.; Lim, J. Signal Estimation from Modified Short-Time Fourier Transform. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process 1984, 32, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, L.; Arikan, O. Short-Time Fourier Transform: Two Fundamental Properties and an Optimal Implementation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process 2003, 51, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.-B.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Tian, S.; Xie, Y. Gear Fault Diagnosis Based on the Structured Sparsity Time-Frequency Analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2018, 102, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, L.; Ma, J. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on STFT-Deep Learning and Sound Signals. Shock Vib 2016, 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Stojanovic, V.; Yang, H. An Unsupervised Fault Diagnosis Method for Rolling Bearing Using STFT and Generative Neural Networks. J. Frankl 2020, 357, 7286–7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Gao, R.X.; Chen, X. Wavelets for Fault Diagnosis of Rotary Machines: A Review with Applications. Signal Process 2014, 96, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Jiang, H. Dual-Core Denoised Synchrosqueezing Wavelet Transform for Gear Fault Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas 2021, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zuo, M.J. Gearbox Fault Detection Using Hilbert and Wavelet Packet Transform. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2006, 20, 966–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.K.; Tai, H.M.; Chen, C.W. Locating Defects of a Gear System by the Technique of Wavelet Transform. Mech. Mach. Theory 2000, 35, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Jiang, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Using Adaptive Deep Belief Network with Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Packet. ISA Trans 2017, 69, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Cheng, J.; Yang, Y. Application of EMD Method and Hilbert Spectrum to the Fault Diagnosis of Roller Bearings. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2005, 19, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, D.; Junsheng, C. A Roller Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Based on EMD Energy Entropy and ANN. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2006, 294, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Ding, L.; Du, W.; Wang, H. Gear Fault Diagnosis Using Dual Channel Data Fusion and EEMD Method. J. Sound Vib 2017, 174, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Bi, F.; Bi, X.; Shao, K. Fault Diagnosis of Diesel Engine Based on Adaptive Wavelet Packets and EEMD-Fractal Dimension. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2013, 41, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Jing, B.; He, P.; Si, S.; Wang, Y. Fault Feature Selection and Diagnosis of Rolling Bearings Based on EEMD and Optimized Elman_AdaBoost Algorithm. IEEE Sen. J 2018, 18, 5024–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational Mode Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, T.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Lei, X.; Wang, X. Application of Tentative Variational Mode Decomposition in Fault Feature Detection of Rolling Element Bearing. Measurement 2018, 135, 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Cheng, G.; Chen, X.; Pang, Y. Planetary Gears Feature Extraction and Fault Diagnosis Method Based on VMD and CNN. Sensors 2018, 18, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, T.; Wu, X.; Chen, Q. An Optimized VMD Method and Its Applications in Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Measurement 2020, 166, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xiao, M.; Niu, Y.; Ji, G. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on WGWOA-VMD-SVM. Sensors 2022, 22, 6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Markert, R. Filter Bank Property of Variational Mode Decomposition and Its Applications. Signal Process 2016, 120, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J. Introduction to Mathematical Morphology. Graph. Models 1986, 35, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Sternberg, S.R.; Zhuang, X. Image Analysis Using Mathematical Morphology. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1987, PAMI-9, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Image Analysis and Mathematical Morphology. Computer Graphics and Image Processing 1982, 20, 96–97. [CrossRef]

- Zana, F.; Klein, J.-C. Segmentation of Vessel-like Patterns Using Mathematical Morphology and Curvature Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Image Process 2001, 10, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, H.-C.; Liu, E.-R. Automatic Reference Color Selection for Adaptive Mathematical Morphology and Application in Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process 2016, 25, 4665–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchet, A.; Montes, S.; Ballarin, V.; Díaz, I. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set and Fuzzy Mathematical Morphology Applied to Color Leukocytes Segmentation. Signal Image Video Process 2019, 14, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.; Dougherty, E.R. Morphological Segmentation for Textures and Particles. In Digital image processing methods; CRC Press, 2020; pp. 43–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Q. The Algorithm of Watershed Color Image Segmentation Based on Morphological Gradient. Sensors 2022, 22, 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Dey, D.; Munshi, S. Mathematical Morphology Aided Shape, Texture and Colour Feature Extraction from Skin Lesion for Identification of Malignant Melanoma. In 2015 International Conference on Condition Assessment Techniques in Electrical Systems (CATCON); 2015; pp. 200–203.

- Godse, R.; Bhat, S. Mathematical Morphology-Based Feature-Extraction Technique for Detection and Classification of Faults on Power Transmission Line. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 38459–38471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhou, L.; Yue, L.; Li, L.; Wang, S. An Enhanced Binarization Framework for Degraded Historical Document Images. EURASIP J. Image Video Process 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimori, Y. Mathematical Morphology-Based Approach to the Enhancement of Morphological Features in Medical Images. J. Clin. Bioinform 2011, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sghaier, M.O.; Foucher, S.; Lepage, R. River Extraction from High-Resolution SAR Images Combining a Structural Feature Set and Mathematical Morphology. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens 2017, 10, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavankar, N.L.; Ghosh, S.K. Automatic Building Footprint Extraction from High-Resolution Satellite Image Using Mathematical Morphology. Eur. J. Remote Sens 2017, 51, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Hu, S.; Geng, P.; Liu, M.; Zhao, J. SAR Image Edge Detection via Sparse Representation. Soft Computing 2017, 22, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Liu, C.; Lou, R. Multi-Scale Edge Detection Method for Potential Field Data Based on Two-Dimensional Variation Mode Decomposition and Mathematical Morphology. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 161138–161156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gui, W.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, L. Medical Images Edge Detection Based on Mathematical Morphology. IEEE Annual Santa Barbara 2005, 6492–6495. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.P.; Wang, R.Z. An Integrated Edge Detection Method Using Mathematical Morphology. Pattern Recogn, Image Anal. 2006, 16, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.K.; Ping, X.J.; Li, T.Y. A New Time-Frequency Spectrogram Analysis of FH Signals by Image Enhancement and Mathematical Morphology. In Fourth Int. Conf. Image and Graph; Chengdu, China, 2007; pp. 610–615.

- Román, J.C.M.; Fretes, V.R.; Adorno, C.G.; Silva, R.G.; Noguera, J.L.V.; Legal-Ayala, H.; Mello-Román, J.D.; Torres, R.D.E.; Facon, J. Panoramic Dental Radiography Image Enhancement Using Multiscale Mathematical Morphology. Sensors 2021, 21, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragos, P.; Pessoa, L.F. Morphological Filtering for Image Enhancement and Detection. In The Image and Video Process Handbook; 1999; pp 135–156.

- Kimori, Y. Morphological Image Processing for Quantitative Shape Analysis of Biomedical Structures: Effective Contrast Enhancement. J. Synchrot. Radiat. 2013, 20, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qi, Y.-S.; Gao, X.-J.; Li, Y.-T.; Liu, L.-Q. A Signal Based “W” Structural Elements for Multi-Scale Mathematical Morphology Analysis and Application to Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearings of Wind Turbines. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 2021, 18, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.J.; Tang, G.J.; An, L.S. New Method of Removing Pulsed Noises in Vibration Data. J. Vib. Shock. 2006, 25, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; Lin, Y. Application of Morphological Filter in Pulse Noise Removing of Vibration Signal. In Cong. Image Signal Process; Sanya, China, 2008; pp 132–135.

- Maragos, P. Pattern Spectrum and Multiscale Shape Representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1989, 11, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges Matheron. Random Sets and Integral Geometry; John Wiley & Sons, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dornaika, F.; Zhang, H. Granulometry Using Mathematical Morphology and Motion. In Proc. IAPR Machine Vision Appl.; Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. 51–54.

- Maria, V.; Vitria, J.M. Mathematical Morphology, Granulometries, and Texture Perception. In Proc. SPIE Conf. Image Algebr. Morphological Image Process. IV; San Diego, USA, 1993; pp. 152–161.

- Laurent, N.; Talbot, H. Mathematical Morphology: From Theory to Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, J.; Soille, P. Mathematical Morphology and Its Applications to Image Processing; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, S.-C. Subband Decomposition of Monochrome and Color Images by Mathematical Morphology. Opt. Eng. 1991, 30, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.-C.; Chen, F.-C. Hierarchical Image Representation by Mathematical Morphology Subband Decomposition. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 1995, 16, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, O.; Li, W. Very Low Bit Rate Image Coding Using Morphological Operators and Adaptive Decompositions. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Image Process.; Tustin, USA, 1994; pp 326–330.

- Florêncio, D.A.F.; Schafer, R.W. A Non-Expansive Pyramidal Morphological Image Coder. In Proc. Int. Conf. Image Process.; Austin, USA, 1994; pp 331–335.

- de Queiroz, R.L.; Florencio, D.A.F.; Schafer, R.W. Nonexpansive Pyramid for Image Coding Using a Nonlinear Filterbank. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1998, 7, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.; Luis, F.C. Adaptive Morphological Representation of Signals: Polynomial and Wavelet Methods. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 1997, 8, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweldens, W. The Lifting Scheme: A Construction of Second Generation Wavelets. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1998, 29, 511–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweldens, W. The Lifting Scheme: A Custom-Design Construction of Biorthogonal Wavelets. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 1996, 3, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweldens, W. Lifting Scheme: A New Philosophy in Biorthogonal Wavelet Constructions. In Wavelet Appl. Signal Image Processing III; San Diego, USA, 1995; pp 68–79.

- Claypoole, R.L.; Davis, G.M.; Sweldens, W.; Baraniuk, R. Nonlinear Wavelet Transforms for Image Coding. In Conference Record of the Thirty-First Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers; Pacific Grove, USA, 1997; pp 662–667.

- Claypoole, R.L.; Baraniuk, R.G.; Nowak, R.D. Lifting Construction of Non-Linear Wavelet Transforms. In Proc. IEEE-SP Int. Symp. Time-Frequency Time-Scale Anal.; Pittsburgh, USA, 1998; pp 49–52.

- Claypoole, R.L.; Baraniuk, R.G.; Nowak, R.D. Adaptive Wavelet Transforms via Lifting. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Acoust, Speech Signal Process.; Seattle, USA, 1999; pp 1513–1516.

- Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, M. On-Line Fast Palmprint Identification Based on Adaptive Lifting Wavelet Scheme. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2013, 42, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, H.J.A.M.; Pesquet-Popescu, B.; Piella, G. Building Nonredundant Adaptive Wavelets by Update Lifting. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2005, 18, 252–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piella, G.; Heijmans, H.J.A.M. Adaptive Lifting Schemes with Perfect Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piella, G.; Pesquet-Popescu, B.; Heijmans, H. Adaptive Update Lifting with a Decision Rule Based on Derivative Filters. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2002, 9, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piella, G.; Pesquet-Popescu, B.; Heijmans, H.J.A.M. Gradient-Driven Update Lifting for Adaptive Wavelets. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2005, 20, 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, H.J.A.M.; Goutsias, J. Nonlinear Multiresolution Signal Decomposition Schemes. II. Morphological Wavelets. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 1897–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutsias, J.; Heijmans, H.J.A.M. Nonlinear Multiresolution Signal Decomposition Schemes. I. Morphological Pyramids. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 1862–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaou, N.G.; Antoniadis, I.A. Application of morphological operators as envelope extractors for impulsive-type periodic signals. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2003, 17, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Tang, B.; Zhang, Y. A Repeated Single-Channel Mechanical Signal Blind Separation Method Based on Morphological Filtering and Singular Value Decomposition. Measurement 2012, 45, 2052–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Dong, S.; Liu, J. Single-Channel Bearing Vibration Signal Blind Source Separation Method Based on Morphological Filter and Optimal Matching Pursuit (MP) Algorithm. J. Vib. Control. 2013, 21, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, K. A New Bearing Fault Diagnosis Scheme Using MED-Morphological Filter and Ridge Demodulation Analysis. J. Vibroeng 2015, 17, 4231–4247. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Jiang, Z.; Qin, Q. A Joint Adaptive Wavelet Filter and Morphological Signal Processing Method for Weak Mechanical Impulse Extraction. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, H. A Hybrid Fault Diagnosis Method Using Morphological Filter–Translation Invariant Wavelet and Improved Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2015, 50–51, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, T.; Liu, H. A New Morphological Filter for Fault Feature Extraction of Vibration Signals. IEEE Access. 2019, 7, 53743–53753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhu, J.; Liu, X.; Kong, F. Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on an Improved Morphological Filter. Measurement 2015, 80, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Xiang, L. An Optimal Selection Method for Morphological Filter’s Parameters and Its Application in Bearing Fault Diagnosis. J. Mech. Sci. Technol 2016, 30, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, L. Application of Improved Morphological Filter to the Extraction of Impulsive Attenuation Signals. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2008, 23, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Jia, M. Application of CSA-VMD and Optimal Scale Morphological Slice Bispectrum in Enhancing Outer Race Fault Detection of Rolling Element Bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2019, 122, 56–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, M.; Franciosa, P.; Ceglarek, D. Rolling Element Bearing Fault Diagnosis Using Integrated Nonlocal Means Denoising with Modified Morphology Filter Operators. Math. Probl. Eng 2016, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liao, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F. Faults Diagnosis of Rolling Element Bearings Based on Modified Morphological Method. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2011, 25, 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.S.; Murali, N. Early Classification of Bearing Faults Using Morphological Operators and Fuzzy Inference. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 2013, 60, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kang, J.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, J. Alpha Stable Distribution Based Morphological Filter for Bearing and Gear Fault Diagnosis in Nuclear Power Plant. Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install 2015, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.; Wang, W. A Morphological Hilbert-Huang Transform Technique for Bearing Fault Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas 2016, 65, 2646–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Yu, J. Average Combination Difference Morphological Filters for Fault Feature Extraction of Bearing. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2017, 100, 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zuo, M.J.; Chen, Y.; Feng, K. An Enhanced Morphology Gradient Product Filter for Bearing Fault Detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2018, 109, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Zuo, M.J. Diagonal Slice Spectrum Assisted Optimal Scale Morphological Filter for Rolling Element Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2016, 85, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.-B.; Zhu, Y.-B.; Sun, H.-G. Study on Fault Diagnosis of Gearbox Based on Morphological Filter and Multi-Fractal Theory. in: Int. Conf. Qual. Reliab. Risk, Maint. Saf. Eng. Xi’an, China 2011, 472–477.

- Zhou, L. Application of Morphological Demodulation in Gear Fault Feature Extraction. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2010, 44, 1514–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Gryllias, K.; Yiakopoulos, C.; Antoniadis, I. Application of Morphological Analysis for Gear Fault Detection and Trending. Diagnostyka 2008, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, S.-R. Hybrid Wavelet-Morphology-Emd Analysis and Its Application. J. Vib. Shock 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Zhen, D.; Li, H.; Shi, Z.; Gu, F.; Ball, A. Fault Detection for Planetary Gearbox Based on an Enhanced Average Filter and Modulation Signal Bispectrum Analysis. ISA Trans 2020, 101, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.; Mi, S.; Liu, D. A Weighted Multi-Scale Morphological Gradient Filter for Rolling Element Bearing Fault Detection. ISA Trans 2011, 50, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Lu, B.; Zhang, D. Multiscale Morphological Manifold for Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Mech. Eng. Sci 2016, 231, 3516–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wu, X. Application of Optimized Multiscale Mathematical Morphology for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Meas. Sci. Technol 2017, 28, 045401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Zhang, P.; Wu, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Bearing Fault Signal Analysis Based on an Adaptive Multiscale Combined Morphological Filter. Int. J. Rotating Mach 2020, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liao, Y.; He, D.; Duan, R.; Zhang, X. Rolling Bearing Diagnosis Based on an Unbiased-Autocorrelation Morphological Filter Method. Measurement 2021, 189, 110617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Iterative Asymmetric Multiscale Morphology and Its Application to Fault Detection for Rolling Element Bearing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C-J. Eng. Mech. Eng. Sci 2017, 232, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J. Train Axle Bearing Fault Detection Using a Feature Selection Scheme Based Multi-Scale Morphological Filter. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2018, 101, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Tang, G.; Wang, X. A Chaotic Feature Extraction Based on SMMF and CMMFD for Early Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 179497–179515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, L. Fault Diagnosis for Road Heading Bearings Based on a Multiscale Enhanced Cascaded Difference Filter. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xiao, C.; Hu, T.; Gao, Y. Selective Weighted Multi-Scale Morphological Filter for Fault Feature Extraction of Rolling Bearings. ISA Trans 2023, 132, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zuo, M.J.; Chen, Z.; Lin, J. Railway Bearing and Cardan Shaft Fault Diagnosis via an Improved Morphological Filter. Health Monit 2019, 19, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, D.; Wang, D. Multiscale Morphology Analysis and Its Application to Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc 2008, 22, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Liang, X.; Huang, W.-H. Application of Bandwidth EMD and Adaptive Multiscale Morphology Analysis for Incipient Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearings. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 2017, 64, 6506–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.N.; Tandon, N.; Pandey, R.K. Improving Defect Detection of Rolling Element Bearings in the Presence of External Vibrations Using Adaptive Noise Cancellation and Multiscale Morphology. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J.-J. Eng. Tribol 2011, 226, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, J.; Shen, C.; Zhu, Z. Adaptive Morphological Feature Extraction and Support Vector Regressive Classification for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Int. J. Rotating Mach 2017, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, J. Early Fault Detection Method for Rolling Bearing Based on Multiscale Morphological Filtering of Information-Entropy Threshold. J. Mech. Sci. Technol 2019, 33, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; He, Q.; Kong, F.; Tse, P.W. A Fast and Adaptive Varying-Scale Morphological Analysis Method for Rolling Element Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C-J. Eng. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2012, 227, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Zuo, M.J. A New Strategy of Using a Time-Varying Structure Element for Mathematical Morphological Filtering. Measurement 2017, 106, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Yang, S.; Tang, G.; Hao, R.; Zhang, M. Self Adaptive Multi-Scale Morphology AVG-Hat Filter and Its Application to Fault Feature Extraction for Wheel Bearing. Meas. Sci. Technol 2017, 28, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, T.; Fu, M.; Ye, M.; Jia, M. Bearing Fault Feature Extraction Method Based on Enhanced Differential Product Weighted Morphological Filtering. Sensors 2022, 22, 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, X. Investigation on Morphological Filtering via Enhanced Adaptive Time-Varying Structural Element for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Measurement 2025, 244, 116466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mei, G.; Chen, B.; Cheng, Y. An Improved Time-Varying Morphological Filtering and Its Application to Bearing Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J 2022, 22, 20707–20717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Song, W.; Teng, H. An Offline Fault Diagnosis Method for Planetary Gearbox Based on Empirical Mode Decomposition and Adaptive Multi-Scale Morphological Gradient Filter. J. Vibroeng 2015, 17, 705–719. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.L.; Wang, Z.J.; Mi, S.S.; Liu, D.S. Gear Fault Detection Using Multi-Scale Morphological Filters. Measurement 2011, 44, 2078–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.C.; Shi, Z.Q.; Li, H.Y.; He, Z.J. Transient Impulses Enhancement Based on Adaptive Multi-Scale Improved Differential Filter and Its Application in Rotating Machines Fault Diagnosis. ISA Trans. 2022, 120, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, L.; Yang, D. Modeling and Fault Identification of the Gear Tooth Surface Wear Failure System. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer Simul. 2021, 22, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.H.; Li, X.Q. Gear Fault Diagnosis Based on Time–Frequency Domain De-Noising Using the Generalized S Transform. J. Vib. Control. 2018, 24, 3338–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Li, G.Y.; Yang, Y.T.; Liang, X.H.; Xu, M.Q. A Fault Diagnosis Scheme for Planetary Gearboxes Using Adaptive Multi-Scale Morphology Filter and Modified Hierarchical Permutation Entropy. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2018, 105, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Li, Y. A Hybrid Approach for Weak Fault Feature Extraction of Gearbox. IEEE Access. 2019, 7, 16616–16625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.S.; Yu, D.J.; Liang, M. Gear Fault Detection under Time-Varying Rotating Speed via Joint Application of Multiscale Chirplet Path Pursuit and Multiscale Morphology Analysis. Struct. Health Monit. 2012, 11, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, M. Adaptive Morphological Filter to Fault Diagnosis of Gearbox. in: Int. Conf. Consum. Electron. Communications Netw. 2011; pp. 70–73.

- Yu, J.B.; Huang, J.H.; Liu, C.H.; Li, Z.N.; Chen, B.Q. Fault Feature of Gearbox Vibration Signals Based on Morphological Filter Dynamic Convolution Autoencoder. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 22931–22942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Cui, L.L.; Zhang, C. Study on Fault Diagnosis Method of Planetary Gearbox Based on Turn Domain Resampling and Variable Multi-Scale Morphological Filtering. Symmetry 2021, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; She, D.; Xu, Y.; Jia, M. Application of Generalized Composite Multiscale Lempel–Ziv Complexity in Identifying Wind Turbine Gearbox Faults. Entropy 2021, 23, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Cui, L.L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Li, G. Research on Fault Diagnosis of Planetary Gearbox Based on Variable Multi-Scale Morphological Filtering and Improved Symbol Dynamic Entropy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 3947–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Yu, J.B. Deep Morphological Convolutional Network for Feature Learning of Vibration Signals and Its Applications to Gearbox Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Sys, Signal Proc. 2021, 161, 107984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.X.; Li, H.K.; Zhang, K.L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.F. Strategy for Detection and Suppression of Random Impulse Interferences in Gearbox Vibration Signals. IEEE Sens. 2024, 24, 3523–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, Z.W.; Sun, W.; Li, C.S. A New Structuring Element for Multi-Scale Morphology Analysis and Its Application in Rolling Element Bearing Fault Diagnosis. J. Vib. Control 21, 765–789. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.W.; Wang, R.C.; Zhang, R.L.; Li, H.F.; Li, H.B. A Novel Fault Diagnosis Method for Rotating Machinery Based on S Transform and Morphological Pattern Spectrum. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2016, 38, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, B.; Hu, X.; He, Q.B. A Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Improved Pattern Spectrum and FOASVM. In. J. Acous. Vib. 2019, 24, 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.Y.; Zhang, W.X.; Zhang, C. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on Mathematical Morphological Spectrum. Mechanism and Machine Science 2023, 129, 688–698. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.F.; Zuo, M.J.; Li, Y.B. Application of Modified Morphological Pattern Spectrum and LSSVM for Fault Diagnosis of Train Wheelset Bearings. In International Conference on Sensing, Diagnostics, Prognostics, and Control; Xi’an, China, 2018; pp. 50–55.

- Gao, J.; Tao, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.C. New Time-Frequency Representations Based on the Morphological Pattern Spectrum for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. In 7th International Conference on Computational Methods; California, USA, 2016; pp 213–231.

- Hao, R.J.; Peng, Z.K.; Feng, Z.P.; Zhang, X.H.; Chu, F.L. Application of Support Vector Machine Based on Pattern Spectrum Entropy in Fault Diagnostics of Rolling Element Bearings. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 045708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.J.; Feng, Z.P.; Chu, F.L. Defects Diagnosis and Classification for Rolling Bearing Based on Mathematical Morphology. In 8th International Conference on Reliability, Maintainability and Safety; Chengdu, China, 2009; pp 817–821.

- Wang, W.J.; Cui, L.L.; Chen, D.Y. Multi-Scale Morphology Analysis of Acoustic Emission Signal and Quantitative Diagnosis for Bearing Fault. Acta Mech. Sin. 2016, 32, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.T.; Lu, W.X.; Chu, F.L. Fault Diagnostics Based on Pattern Spectrum Entropy and Proximal Support Vector Machine. Key Eng. Mater. 2009, 413, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Ding, P.; Jia, M.P.; Li, Y.B. Fault Diagnosis of Rolling-Element Bearing Using Multiscale Pattern Gradient Spectrum Entropy Coupled with Laplacian Score. Complexity 2020, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.M.; Yao, R.; Xu, L.; Yuan, Y.B.; Li, Y.B. Study on a Novel Fault Damage Degree Identification Method Using High-Order Differential Mathematical Morphology Gradient Spectrum Entropy. Entropy 2018, 20, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.M.; Liu, H.D.; Xu, J.J.; Li, Y.B. Performance Prediction Using High-Order Differential Mathematical Morphology Gradient Spectrum Entropy and Extreme Learning Machine. IEEE Tran. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 4165–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.R.; Wang, Y.K.; Wang, B.; Luo, M.Y.; Li, Y.B. The Application of a General Mathematical Morphological Particle as a Novel Indicator for the Performance Degradation Assessment of a Bearing. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2017, 82, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. A New Approach for Performance Degradation Feature Extraction Based on Generalized Pattern Spectrum Entropy. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C-J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2015, 231, 1932–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, W.; Hou, M.H.; Li, H.R.; Li, Y.B. Bearing Performance Degradation Condition Recognition Based on a Combination of Improved Pattern Spectrum Entropy and Fuzzy C-Means. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 34, 3681–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, M.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, P.L.; Liu, D.S. Characterizing Vibration Signals Utilizing Morphological Pattern Spectrum for Gear Fault Diagnosis. In 3rd International Conference on Mechatronics, Robotics and Automation; Shenyang, China, 2015; pp 707–711.

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.-L.; Wang, Z.-J.; Mi, S.-S.; Liu, D.-S. Application of S Transform and Morphological Pattern Spectrum for Gear Fault Diagnosis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C-J. Eng. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2011, 225, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, N.; Barbieri, G.; Martins, B.; Sant’Ana, R.; De Lacerda De Oliveira, L. Analysis of Automotive Gearbox Faults Using Vibration Signal. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 129, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.J.; Chu, F.L. Morphological Undecimated Wavelet Decomposition for Fault Diagnostics of Rolling Element Bearings. J. Sound Vibr 2009, 320, 1164–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, J. Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearing Based on Lifting Morphological Wavelet and Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition. In International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Communications and Networks; Xining, China, 2011; pp 2229–2232.

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.L.; Mi, S.S.; Liu, D.S.; Ren, Y.Q. An Adaptive Morphological Gradient Lifting Wavelet for Detecting Bearing Defects. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2012, 29, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, S. Multi-Scale Autocorrelation via Morphological Wavelet Slices for Rolling Element Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2012, 31, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Li, H.R.; Xu, B.H. An Improved Multi-Scale Morphological Undecimated Wavelet Method and Its Application in Rolling Bearing Fault Feature Extraction. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 380, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xiong, J.; Sun, R.; Chen, Y.C. Research on the Roller Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on Morphological Wavelet and LSSVM Algorithm. In International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance, and Safety Engineering; Mingshan, China, 2013; pp 1888–1892.

- Meng, L.J.; Xiang, J.W.; Zhong, Y.T.; Wang, Y.Y. Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearing Based on Second Generation Wavelet Denoising and Morphological Filter. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakipour, M.H.; Safavi, A.A.; Setoodeh, P. Bearing Fault Diagnosis with Morphological Gradient Wavelet. J. Frankl. Inst. 2016, 354, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Development of a Morphological Convolution Operator for Bearing Fault Detection. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 421, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, Q.; Zhen, D.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.D. An Iterative Morphological Difference Product Wavelet for Weak Fault Feature Extraction in Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 2222, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z. Multioperator Morphological Undecimated Wavelet for Wheelset Bearing Compound Fault Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tan, Y.; Pu, Y. Rolling Bearing Fault Vibration Signal Denoising Based on Adaptive Morphological Wavelet Perona–Malik Filter Algorithm. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Liao, Y.; Yang, L.; Song, E. Faulty Bearing Signal Analysis with Empirical Morphological Undecimated Wavelet. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ji, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.-N. Fault Feature Extraction of Fan Bearing Based on Improved Mathematical Morphological Unsampled Wavelet. Chin. Autom. Congress 2017, 33, 3188–3192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Shen, L.; Li, J.; Cai, Q.; Wang, H. Morphological Undecimated Wavelet Decomposition for Fault Feature Extraction of Rolling Element Bearing. In 2009 2nd International Congress on Image and Signal Processing; IEEE, 2009; pp. 1–5.

- Yong, L. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on Morphological Wavelet Theory and Bi-Spectrum Analysis. J. Zhejiang Univ-Eng. Sci. 2010, 44, 432–439. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; Lin, Y. Rolling Bearing Fault Feature Extraction Based on Morphological Wavelet and S-Transform. J. Zhejiang Univ-Eng. Sci. 2010, 44, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.; Mao, Q.; Mi, S.; Liu, P. Gear Fault Detection Using Adaptive Morphological Gradient Lifting Wavelet. J. Vib. Control. 2012, 19, 1646–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.B.; Su, Y.P.; Zhou, Y.J.; Pu, Y.S. A New Intelligent Fault Recognition Method for Gearbox. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 684, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Fang-jian, S.; Bo, C.; Wei, Q. Research of Gear Fault Detection in Morphological Wavelet Domain. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 679, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Pu, Y.; Guo, D.; Jiang, J.; Yu, L.; Min, J. Application of Morphological Wavelet and Permutation Entropy in Gear Fault Recognition. Evol. Intell. 2020, 15, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wang, X. Crack Fault Diagnosis of Gear Based on Morphological Wavelet De-Noising. J. Mech. Strength. 2015, 37, 398–402. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, L.; Huang, J. Fault Recognition Method of Transmission Gear Based on Morphological Wavelet and Permutation Entropy. J. Mech. Transm. 2019, 43, 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Mi, S.; Liu, D. Max-Lifting Morphological Wavelet Transform Based Gear Fault Feature Extraction. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2010, 31, 2736–2741. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, R.; Kang, J.; Li, B.; Sun, J. A Preprocessing Method for the Vibration Signal of Gear Based on MUDW and CK. In 2017 9th International Conference on Modelling, Identification and Control (ICMIC); 2017; pp. 680–686.

- Shen, L.; Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, F. Application of Morphological Wavelet De-noising in Extracting Gear Fault Feature. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agr. Mach. 2010, 41, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.-F.; Zuo, M.; Feng, K.; Chen, Y.-J. Detection of Bearing Faults Using a Novel Adaptive Morphological Update Lifting Wavelet. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2017, 30, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zuo, M.J.; Lin, J.; Liu, J. Fault Detection Method for Railway Wheel Flat Using an Adaptive Multiscale Morphological Filter. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2017, 84, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zheng, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y. Demodulation for Hydraulic Pump Fault Signals Based on Local Mean Decomposition and Improved Adaptive Multiscale Morphology Analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 2015, 58-59, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mi, S.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z. Classification of Time-Frequency Representations Using Improved Morphological Pattern Spectrum for Engine Fault Diagnosis. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 3329–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mei, G. Investigation on Enhanced Mathematical Morphological Operators for Bearing Fault Feature Extraction. ISA Trans. ISA Trans. 2021, 126, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object | Ref. | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Bearing | Nakolaou [74], Dong [75], Chen [76], Chao [77], He [78], Meng [79], Yu [80], Hu [81], Hu [82], Wang [83], Jia [84], Van [85], Dong [86], Raj [87], Zhang [88], Osman [89], Lv [90], Li [91,92] | SSM |

| Li [98], Feng [99], Gong [100], Lv [101], Tang [102], Gong [103], Li [104], Yan [105], Qu [106], Yu [107], Li [108], Zhang [109], Li [110], Patel [111], Shuai [112], Cui [113], Shen [114], Li [115], Deng [116], Yan [117], Wang [118,119] | MSM | |

| Chen [135], Gao [136], Sun [137], Zhu [138], Li [139], Gao [140], Hao [141,142], Wang [143], Yu [144], Yan [145], Zhao [146,147], Li [148], Gao [149], Wang [150] | MPS | |

| Hao [154], Wang [155], Li [156], Li [157], Chen [158], Han [159], Meng [160], Khakipour [161], Li [162], Guo [163], Li [164], Li [165], Duan [166], Wang [167], Zhang [168], Lin [169], Yan [170] | MW | |

| Gear | Feng [93], Chen [94], Gryllias [95], Lin [96], Guo [97] | SSM |

| Li [120], Li [121], Guo [122], Wang [123], Cai [124], Li [125], Yu [126], Luo [127], Zhang [128], Yu [129], Liu [130], Yan [131], Liu [132], Zhuang [133], Cao [134] | MSM | |

| Li [151], Li [152], Barbieri [153] | MPS | |

| Li [171], Zhang [172], Hong [173], Zhang [174], Cai [175], Ding [176], Zhang [177], Tong [178], Shen [179], Li [180] | MW | |

| Others | Li [181], Jiang [182] | MSM |

| Li [183] | MPS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).