Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Border Paradox

1.2. Public Perception of COVID-19 and Vaccine Acceptance

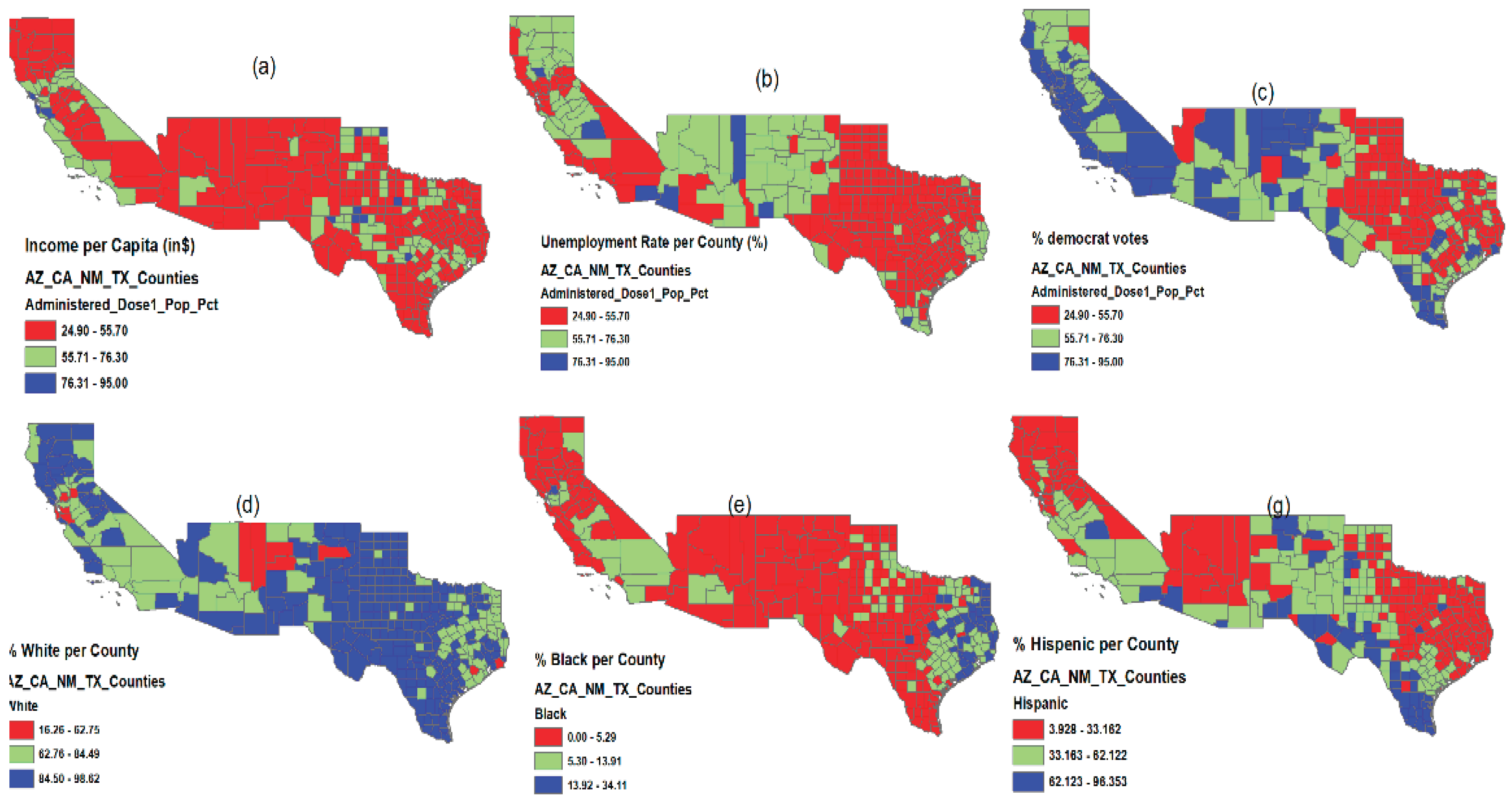

1.3. Economic and Socio-Political Impacts on Vaccination Efforts

1.4. Theoretical Linkage

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Variables

- Variable Description

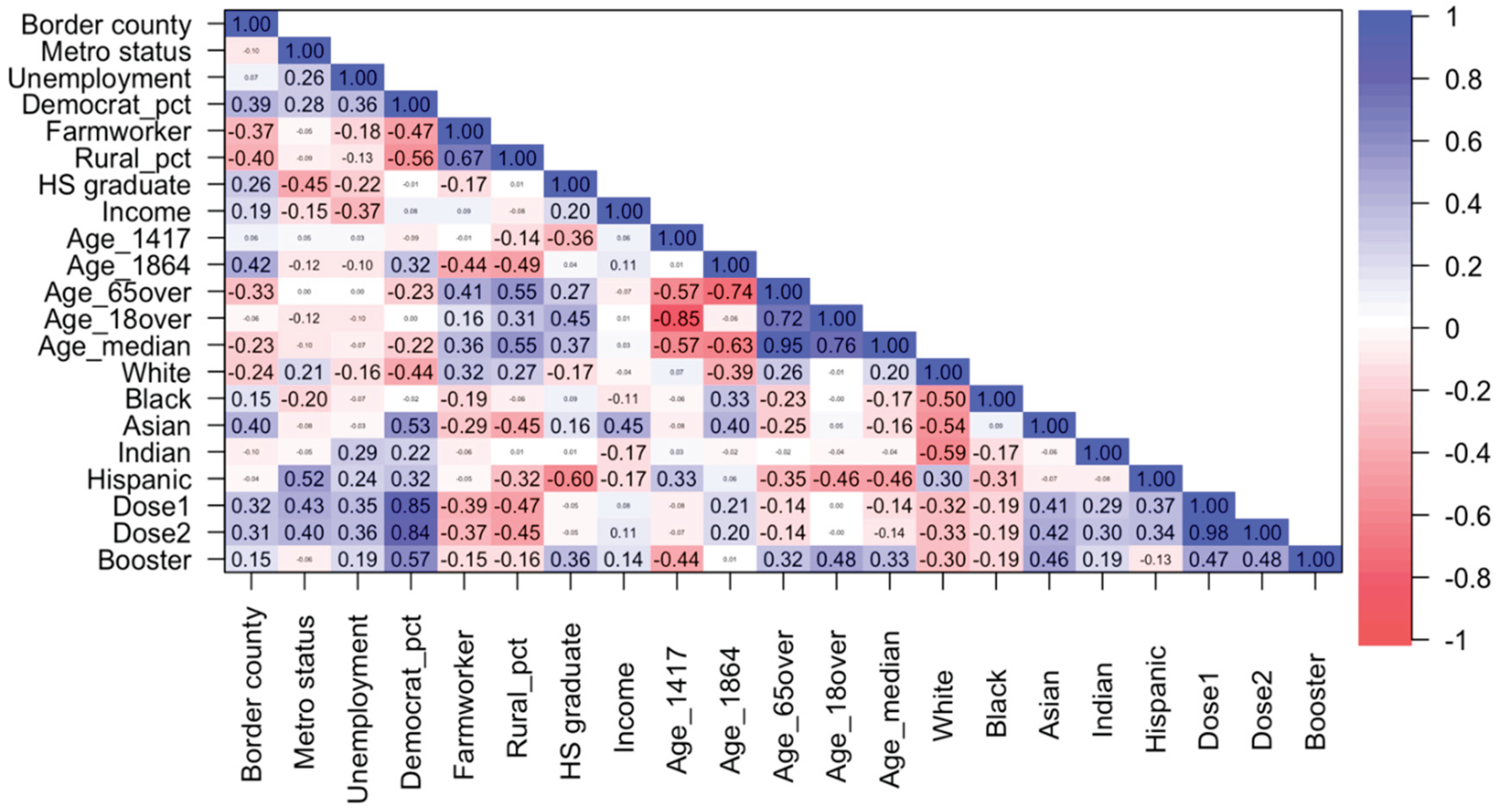

2.2. Statistical Methods

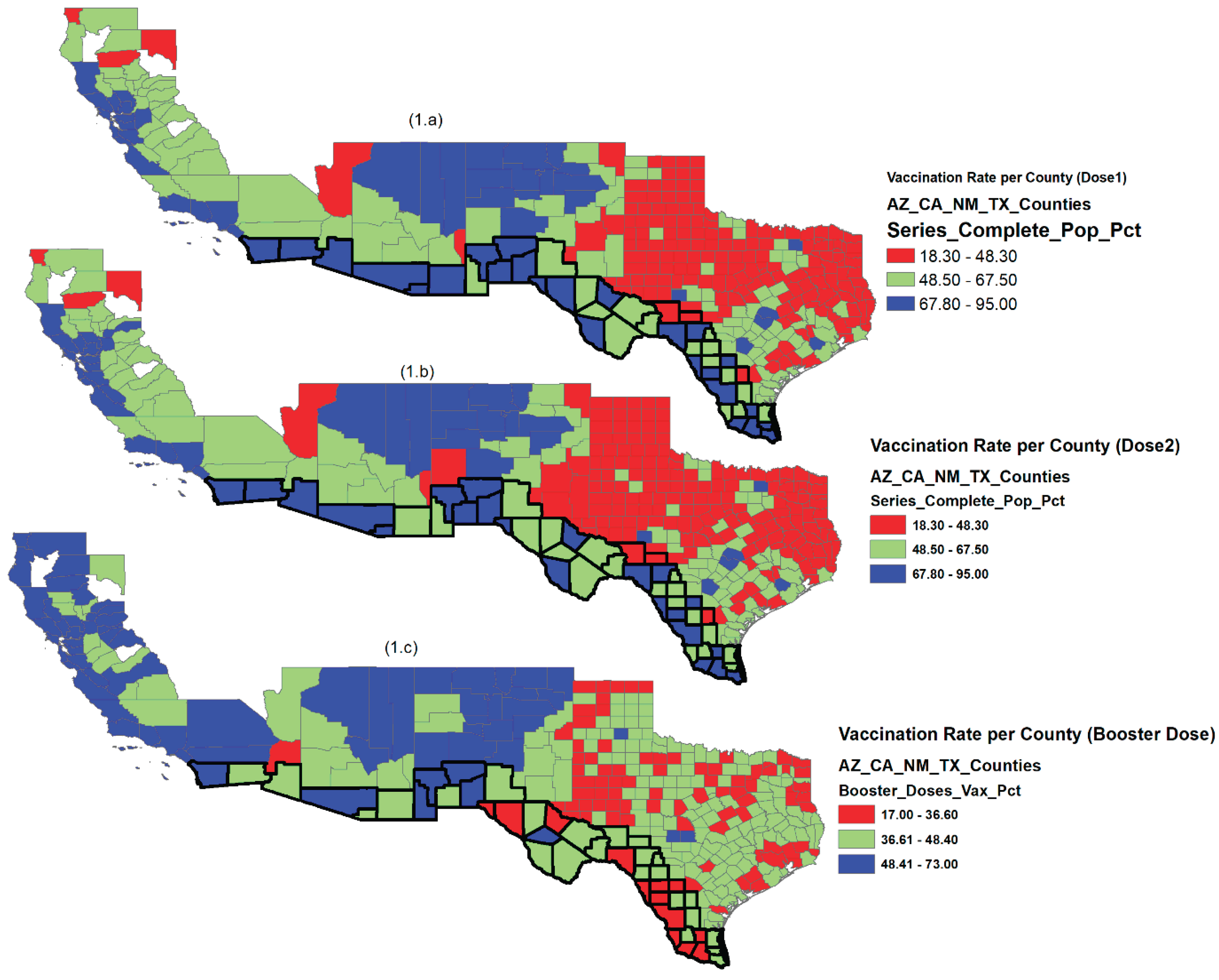

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institutional: Review Board Statement

Informed: Consent Statement

Conflicts: of Interest

Funding

Author Contributions. Conceptualization

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A

| Characteristic | First Dose | Second Dose | Booster Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Initial COVID-19 vaccine | Completion of the primary vaccination series | Additional dose post-primary vaccination |

| Eligibility | All eligible individuals | Only those who received the first dose | Only those fully vaccinated |

| Timing | Late 2020 (14 December 2020) | Mid–late 2021 | Late 2021 forward (updated as variants emerged) |

| Population Coverage | Broadest | Subset of first-dose recipients | Subset of fully vaccinated individuals |

| Sample Selection Implication | Represents the full target population | Filtered by initial compliance | Self-selected, high-engagement population |

| Analytical Implication | Broad determinants of uptake | Dependent on dose 1 behavior | Selection bias, influenced by the evolving pandemic context |

References

- Albrecht, D. Vaccination, Politics and COVID-19 Impacts. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Dugas, M.; Ramaprasad, J.; Luo, J.; Li, G.; Gao, G. Socioeconomic Privilege and Political Ideology Are Associated with Racial Disparity in COVID-19 Vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118, e2107873118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Anneser, E.; Toppo, A.; Allen, J.D.; Parott, J.S.; Corlin, L. Disparities in National and State Estimates of COVID-19 Vaccination Receipt and Intent to Vaccinate by Race/Ethnicity, Income, and Age Group among Adults≥ 18 Years, United States. Vaccine 2022, 40, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Lee, Y.-F.; Koumi, K. COVID-19 Vaccination: Sociopolitical and Economic Impact in the United States. Epidemiologia 2022, 3, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, D.; Artiga, S. Health and Health Care in the US-Mexico Border Region. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bastida, E.; Brown, H.S., III; Pagán, J.A. Persistent Disparities in the Use of Health Care along the US–Mexico Border: An Ecological Perspective. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.Y.; Chang, J.; Ramamonjiarivelo, Z.H.; Medina, M. Does Geographic Location Affect the Quality of Care? The Difference in Readmission Rates between the Border and Non-Border Hospitals in Texas. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homedes, N.; Ugalde, A. Globalization and Health at the United States–Mexico Border. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 2016–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quenzer, F.C.; Coyne, C.J.; Ferran, K.; Williams, A.; Lafree, A.T.; Kajitani, S.; Mathen, G.; Villegas, V.; Kajitani, K.M.; Tomaszewski, C. ICU Admission Risk Factors for Latinx COVID-19 Patients at a US-Mexico Border Hospital. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 3039–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 Vaccine Data at the State Level; Internet, 2023.

- Santangelo, O.E.; Provenzano, S.; Di Martino, G.; Ferrara, P. COVID-19 Vaccination and Public Health: Addressing Global, Regional, and Within-Country Inequalities. Vaccines 2024, 12, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet-Jailly, E.; Carpenter, M.J. Introduction to the Special Issue: Borderlands in the Era of COVID-19. Bord. Glob. Rev. 2020, 2, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, S.A.; Ruiz, M.P.; McDaniel, K.; Hartsell, A.R.; Pierce, C.J.; Devine, J.A.; Johnson, M.; Tinglov, A.K.; Yang, M.; Wu, X.; et al. Im/Mobility at the US–Mexico Border during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filosa, J.N.; Botello-Mares, A.; Goodman-Meza, D. COVID-19 Needs No Passport: The Interrelationship of the COVID-19 Pandemic along the US-Mexico Border. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gorman, S. Does Geographical Location Matter During a Pandemic? Implications of COVID-19 on Texas Border Counties When Compared to Interior Counties. J. Borderl. Stud. 2024, 39, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, BJ; Calvillo, ST; Escoto, AA; Lomeli, A; Burola, ML; Gay, L; Cohen, A; Villegas, I; Salgin, L; Cain, KL; Pilz, D. Community Utilization of a Co-Created COVID-19 Testing Program in a US/Mexico Border Community. BMC Public Health 2024, 24(1), 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S; Rubio, B; Piat, C; Kamara, H; Owen, P; Duff, B; Chavez, A; Bligh, LR. Improving Public Health Emergency Communication Along the US Southern Border: Insights From a COVID-19 Pilot Campaign With Truck Drivers. Health Promotion Practice 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel Gómez, M.G.; Alcocer Varela, J.; Salazar Jiménez, S.; Olivares Marín, L.; Rosales, C. The Impact of COVID-19 and Access to Health Services in the Hispanic/Mexican Population Living in the United States. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 977792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, B.T.; Hernandez Rodriguez, J. How Did Latinxs near the US-Mexico Border Fare during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Snapshot of Anxiety, Depression, and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1241603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cione, C.; Vetter, E.; Jackson, D.; McCarthy, S.; Castañeda, E. The Implications of Health Disparities: A COVID-19 Risk Assessment of the Hispanic Community in El Paso. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-F. COVID-19 Crisis and International Business and Entrepreneurship: Which Business Culture Enhances Post-Crisis Recovery? Glob. J. Entrep. GJE 2021, 5. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck, D.; Frissen, T.; Matthijs, K.; d’Haenens, L.; Lits, G.; Champagne-Poirier, O.; Carignan, M.-E.; David, M.D.; Pignard-Cheynel, N.; Salerno, S. Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation about COVID-19: Comparative Perspectives on the Role of Anxiety, Depression and Exposure to and Trust in Information Sources. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.L. Science Denial and COVID Conspiracy Theories: Potential Neurological Mechanisms and Possible Responses. Jama 2020, 324, 2255–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y. Willingness to Pay for a COVID-19 Vaccine. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy. 2021, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.Y.; Cerda, A.A. Authors’ Reply to Sprengholz and Betsch:Willingness to Pay for a COVID-19 Vaccine. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy. 2021, 19, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.A.; García, L.Y. Hesitation and Refusal Factors in Individuals’ Decision-Making Processes Regarding a Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 626852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S.; De Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.J.; De Graaf, K.; Larson, H.J. Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Vaccination Intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine Hesitancy: An Overview. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latkin, C.A.; Dayton, L.; Yi, G.; Konstantopoulos, A.; Boodram, B. Trust in a COVID-19 Vaccine in the US: A Social-Ecological Perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woko, C.; Siegel, L.; Hornik, R. An Investigation of Low COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions among Black Americans: The Role of Behavioral Beliefs and Trust in COVID-19 Information Sources. In Vaccine Communication in a Pandemic; Routledge, 2023; pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gollust, S.E.; Nagler, R.H.; Fowler, E.F. The Emergence of COVID-19 in the US: A Public Health and Political Communication Crisis. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 2020, 45, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadarian, S.K.; Goodman, S.W.; Pepinsky, T.B. Pandemic Politics: How COVID-19 Exposed the Depth of American Polarization. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostetter, M.; Klein, S. Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust among Black Americans. Commonw. Fund 2021, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Matini, K. Exploring the Healthcare Experiences of African Immigrant Women in Winnipeg, Manitoba. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.P.; Gupta, V. COVID-19 Vaccine: A Comprehensive Status Report. Virus Res. 2020, 288, 198114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. Racial Concentration and Dynamics of COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. SSM-Popul. Health 2022, 19, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Dudley, M.Z.; Chen, X.; Bai, X.; Dong, K.; Zhuang, T.; Salmon, D.; Yu, H. Evaluation of the Safety Profile of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Review. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.M.; Plotkin, S.A. Impact of Vaccines; Health, Economic and Social Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Cheah, P.Y.; von Seidlein, L. Trust Is the Common Denominator for COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Literature Review. Vaccine X 2022, 12, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Alarming Trends in US Domestic Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, A.; Joseph, M.; Felix, R. Changing the Narrative: Structural Barriers and Racial and Ethnic Inequities in COVID-19 Vaccination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, D.B.G.; Shah, A.; Doubeni, C.A.; Sia, I.G.; Wieland, M.L. The Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, L.; Artiga, S.; Safarpour, A.; Stokes, M.; Brodie, M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: COVID-19 Vaccine Access, Information, and Experiences among Hispanic Adults in the US Https://Www. Kff. Org/Coronavirus-Covid-19/Poll-Finding/Kff-Covid-19-Vaccine-Monitor-Access-Information-Experiences-Hispanic-Adults. Publ 2021, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Umeh, K.C.; Kim, J. Income Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccine and Booster Uptake in the United States: An Analysis of Cross-Sectional Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0298825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, A.; Rader, B.; Sewalk, K.; Brownstein, J.S. Emerging Socioeconomic Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccine Second-Dose Completion Rates in the United States. Vaccines 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A.; Gershon, R.; Gneezy, A. COVID-19 and Vaccine Hesitancy: A Longitudinal Study. PloS One 2021, 16, e0250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, B.P. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage between Urban and Rural Counties—United States, December 14, 2020–April 10, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, I.; Hoven, H.; Kawachi, I. Far-Right Political Ideology and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Multilevel Analysis of 21 European Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 335, 116227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żuk, P.; Żuk, P. The Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic Experiences on Attitudes towards Vaccinations: On the Social, Cultural and Political Determinants of Preferred Vaccination Organization Models in Poland. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2024, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, O.; Manga, M.. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Exports: New Evidence from Selected European Union Countries and Turkey. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 6, 1195–1219. [CrossRef]

- Nail, T. Theory of the Border; Oxford University Press, 2016; ISBN 0-19-061867-1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. The Wealth of Nations. In Inq. Nat. Causes Wealth Nations Adam Smith Electron.; 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Myrtue Medical Center. CDC Recommends Pfizer Booster Dose for Adults 65+ and Specific At-Risk Groups 2021.

- Politico 2020 Elections 2022.

- Dooling, K. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Updated Interim Recommendation for Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services U.S.-Mexico Border Health Observatory. Internet; 2025.

- Economic Resaerch Service; U.D. of A. Rural Classifications - What Is Rural? Internet, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, L.; Holmes, W. Evaluating Metro and Non-Metro Differences in Uninsured Populations. US Census Bur. Small Area Estim. Branch Wash. DC Available Http1 Usa Gov1VzUTCy; 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Factor | Variable | Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| State | State | States (AZ, CA, NM, TX) | |

| Metro area | Metro status |

Metro status=1, Non-metro status=0 |

CDC https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccinations-in-the-United-States-County/8xkx-amqh |

| Border area | Border county |

Border county=1, Non-Border county=0 |

US Department of Health and Human Services https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/oga/about-oga/what-we-do/international-relations-division/americas/border-health-commission/observatory/index.html |

| Employment status |

Unemployment | Unemployment rate in 2019 | Bureau of Labor Statistics published by Economic Research Service of USDA https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=17828 |

| Political choice |

Democrat_pct | Percent of democrat votes, 2020 election result | Politico https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/ |

| Democrat_1 | Democrat=1, Republican=0 | ||

| Occupation | Farmworker | Percent of workers hired for farm labor | Bureau of Economic Analysis 2019 https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6 |

| Area of residence |

Rural_pct | Percent of the county population living in rural areas | 2010 US Census https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6 |

| Urban status | Urban if Rural_pct ≤ 50, Rural if Rural_pct > 50 | ||

| Education | HS graduate | Percent of county population who is a high school graduate or higher (5-year estimate) for the population 18 years old and over | Federal Reserve Economic Data 2019 https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release/tables?rid=330&eid=391443 |

|

Income |

Income | Per capita personal income | Bureau of Economic Analysis 2019 https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6 |

| Age | Age_1417 | Percent of county resident population aged between 14 and 17 | 2010 US Census (April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019) https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-detail.html |

| Age_1864 | Percent of county resident population aged between 18 and 64 | ||

| Age_65over | Percent of county resident population aged 65 years and over | ||

| Age_18over | Percent of county resident population aged 18 years and over | ||

| Age_median | Median age of county resident population | ||

| Race/ethnicity | White | Percent of country population by race (White) | 2010 US Census https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-detail.html |

| Black | Percent of country population by race (Black) | ||

| Asian | Percent of county population by race (Asian) | ||

| Indian | Percent of county population by race (Indian) | ||

| Other | Percent of county population by race (other) | ||

| Hispanic | Percent of county population by Hispanic origin (Hispanic) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | Percent of county population by non-Hispanic origin (non-Hispanic) | ||

| Vaccination | Administered_Dose1_Pop_Pct (Dose1) | Percent of Total Population with at least one Dose by State of Residence as of September 14, 2022 | CDC https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccinations-in-the-United-States-County/8xkx-amqh |

| Series_Complete_Pop_Pct (Dose2) | Percent of people who have completed a primary series (have second dose of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of a single-dose vaccine) based on the jurisdiction and county where vaccine recipient lives as of September 14, 2022 | ||

| Booster_Doses_Vax_Pct (Booster) | Percent of people who completed a primary series and have received a booster (or additional) dose as of September 14, 2022 |

| All | AZ | CA | NM | TX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 352 | 15 | 50 | 33 | 254 |

| (NA*) | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Metro County | 134 [38.1%] | 8 [53.3%] | 37 [74%] | 7 [21.2%] | 82 [32.3%] |

| Border County | 44 [12.5%] | 4 [26.6%] | 2 [4%] | 6 [18.2%] | 32 [12.6%] |

| Unemployment (%) | 4.07 ± 1.94 | 6.64 ± 3.28 | 5.22 ± 3.11 | 5.44 ± 1.64 | 3.51 ± 1.09 |

| Democrat_pct (%) | 31.57 ± 18.63 | 43.61 ± 14.34 | 55.04 ± 15.06 | 44.79 ± 16.91 | 24.53 ± 14.15 |

| Farmworker (%) | 5.37 ± 5.74 | 1.57 ± 1.83 | 1.81 ± 1.99 | 4.67 ± 5.91 | 6.39 ± 5.99 |

| Rural_pct (%) | 48.98 ± 32.33 | 34.11 ± 19.75 | 20.57 ± 20.00 | 48.42 ± 30.54 | 55.52 ± 31.90 |

| HS graduate (%) | 81.74 ± 8.05 | 84.48 ± 5.32 | 83.74 ± 7.19 | 84.36 ± 5.42 | 80.85 ± 8.46 |

| Income ($) | 49,375 ± 16,205 | 40,592 ± 5,580 | 57,759 ± 24,555 | 40,855 ± 9,238 | 49,351 ± 14,391 |

| Age (%) | |||||

| 14-17 years old | 5.36 ± 0.92 | 5.02 ± 0.88 | 5.09 ± 0.86 | 4.93 ± 0.97 | 5.48 ± 0.90 |

| 18-64 years old | 57.88 ± 4.14 | 55.95 ± 5.31 | 60.32 ± 3.39 | 56.40 ± 4.28 | 57.70 ± 4.00 |

| ≥ 65 years old | 18.83 ± 5.91 | 21.70 ± 7.98 | 17.19 ± 4.73 | 22.15 ± 7.67 | 18.55 ± 5.53 |

| ≥ 18 years old | 76.71 ± 3.96 | 77.65 ± 4.03 | 77.51 ± 4.01 | 78.55 ± 4.29 | 76.25 ± 3.82 |

| Median (years old) | 39.77 ± 6.25 | 41.23 ± 8.35 | 38.72 ± 5.38 | 42.65 ± 8.06 | 39.52 ± 5.92 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |||||

| White | 86.57 ± 10.40 | 78.32 ± 19.40 | 79.76 ± 11.04 | 84.94 ± 15.84 | 88.61 ± 7.49 |

| Black | 5.82 ± 5.92 | 2.36 ± 1.85 | 4.02 ± 3.23 | 1.96 ± 1.32 | 6.88 ± 6.46 |

| Asian | 2.45 ± 7.76 | 1.57 ± 1.15 | 9.10 ± 9.28 | 1.24 ± 1.12 | 1.35 ± 2.08 |

| Indian | 2.80 ± 7.32 | 15.10 ± 20.69 | 2.53 ± 1.65 | 9.32 ± 16.14 | 1.28 ± 0.51 |

| Hispanic | 36.31 ± 22.07 | 31.71 ± 20.83 | 33.85 ± 18.20 | 48.69 ± 17.05 | 35.46 ± 22.97 |

| Vaccination rate (%) | |||||

| Dose 1 | 60.52 ± 16.89 | 76.31 ± 16.64 | 74.05 ± 12.98 | 76.46 ± 15.31 | 54.85 ± 14.20 |

| Dose 2 | 52.61 ± 15.38 | 65.81 ± 16.69 | 65.87 ± 12.91 | 64.82 ± 14.01 | 47.64 ± 12.90 |

| Booster | 41.58 ± 8.96 | 45.33 ± 4.91 | 53.54 ± 8.42 | 52.66 ± 7.14 | 37.56 ± 5.34 |

| (M1) | (M2) | (M3.1) | (M3.2) | (M3.3) | (M3.4) | (M3.5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model1 | Model1+ Age_65over | Model1+Age_65over +White | Model1+Age_65over +Black | Model1+Age_65over +Asian |

Model1+Age_65over +Indian |

Model1+Age_65over +Hispanic |

|

| R-squared | 0.792 | 0.793 | 0.793 | 0.806 | 0.793 | 0.806 | 0.793 |

| State (NM*) | |||||||

| AZ | -1.356 | -1.495 | -1.788 | -1.416 | -1.534 | -4.029 | -1.196 |

| (0.588) | (0.551) | (0.483) | (0.560) | (0.541) | (0.106) | (0.642) | |

| CA | -10.388 | -10.407 | -10.432 | -10.150 | -10.883 | -8.294 | -10.084 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| TX | -8.465 | -8.254 | -8.324 | -5.286 | -8.314 | -6.429 | -8.033 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.004) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Metro Status | 2.035 | 2.246 | 2.322 | 2.366 | 2.176 | 3.357 | 2.253 |

| (0.054) | (0.040) | (0.035) | (0.026) | (0.047) | (0.002) | (0.039) | |

| Border County | 11.479 | 11.184 | 11.565 | 9.223 | 11.282 | 12.779 | 10.904 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Unemployment | 0.160 | 0.154 | 0.140 | 0.268 | 0.180 | 0.007 | 0.155 |

| (0.583) | (0.598) | (0.632) | (0.345) | (0.539) | (0.981) | (0.596) | |

| Democrat_pct | 0.644 | 0.644 | 0.633 | 0.684 | 0.635 | 0.599 | 0.641 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Farmworker | 0.024 | 0.004 | 0.008 | -0.060 | 0.003 | -0.010 | -0.011 |

| (0.827) | (0.968) | (0.941) | (0.579) | (0.976) | (0.927) | (0.926) | |

| Rural_pct | -0.017 | -0.023 | -0.025 | -0.015 | -0.021 | -0.041 | -0.020 |

| (0.393) | (0.282) | (0.245) | (0.482) | (0.327) | (0.050) | (0.378) | |

| HS graduate | 0.023 | -0.003 | -0.009 | 0.031 | -0.005 | -0.017 | 0.014 |

| (0.734) | (0.968) | (0.905) | (0.666) | (0.951) | (0.817) | (0.863) | |

| Income | 9.33e-05 | 9.50e-05 | 9.55e-05 | 7.18e-05 | 8.65e-05 | 10.48 e-05 | 9.69e-05 |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.018) | (0.008) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Age_65over | 0.081 | 0.099 | 0.024 | 0.084 | 0.187 | 0.093 | |

| (0.431) | (0.354) | (0.808) | (0.415) | (0.068) | (0.378) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | -0.035 | -0.386 | 0.106 | 0.330 | 0.016 | ||

| (0.502) | (<0.001) | (0.426) | (<0.001) | (0.596) |

| (M1) | (M2) | (M3.1) | (M3.2) | (M3.3) | (M3.4) | (M3.5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model1 | Model1+ Age_65over | Model1+ Age_65over +White | Model1+ Age_65over +Black | Model1+ Age_65over +Asian |

Model1+ Age_65over +Indian |

Model1+ Age_65over + Hispanic |

|

| R-squared | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.761 | 0.775 | 0.760 | 0.779 | 0.760 |

| State (NM*) | |||||||

| AZ | 0.134 | 0.046 | -0.393 | 0.123 | 0.012 | -2.749 | -0.042 |

| (0.956) | (0.985) | (0.875) | (0.959) | (0.996) | (0.255) | (0.987) | |

| CA | -6.195 | -6.207 | -6.244 | -5.956 | -6.617 | -3.876 | -6.302 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.037) | (0.002) | |

| TX | -4.357 | -4.224 | -4.330 | -1.322 | -4.276 | -2.211 | -4.289 |

| (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.013) | (0.461) | (0.014) | (0.196) | (0.017) | |

| Metro Status | 1.053 | 1.186 | 1.300 | 1.304 | 1.125 | 2.412 | 1.184 |

| (0.308) | (0.267) | (0.226) | (0.208) | (0.294) | (0.022) | (0.268) | |

| Border County | 9.123 | 8.936 | 9.507 | 7.019 | 9.021 | 10.696 | 9.019 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Unemployment | 0.471 | 0.467 | 0.446 | 0.579 | 0.490 | 0.305 | 0.467 |

| (0.099) | (0.103) | (0.120) | (0.038) | (0.089) | (0.269) | (0.103) | |

| Democrat_pct | 0.611 | 0.611 | 0.594 | 0.649 | 0.603 | 0.561 | 0.612 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Farmworker | 0.042 | 0.030 | 0.036 | -0.032 | 0.029 | 0.015 | 0.035 |

| (0.687) | (0.779) | (0.740) | (0.759) | (0.786) | (0.888) | (0.755) | |

| Rural_pct | -0.004 | -0.008 | -0.011 | 0.000 | -0.006 | -0.028 | -0.009 |

| (0.831) | (0.704) | (0.601) | (0.990) | (0.766) | (0.167) | (0.683) | |

| HS graduate | 0.038 | 0.021 | 0.012 | 0.055 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.016 |

| (0.567) | (0.770) | (0.866) | (0.441) | (0.785) | (0.930) | (0.838) | |

| Income | 10.96e-05 | 11.07e-05 | 11.15e-05 | 8.80e-05 | 10.34e-05 | 12.15e-05 | 11.02e-05 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Age_65over | 0.051 | 0.077 | -0.004 | 0.054 | 0.168 | 0.048 | |

| (0.612) | (0.457) | (0.966) | (0.595) | (0.091) | (0.645) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | -0.052 | -0.378 | 0.091 | 0.364 | -0.005 | ||

| (0.304) | (<0.001) | (0.484) | (<0.001) | (0.873) |

| (M1) | (M2) | (M3.1) | (M3.2) | (M3.3) | (M3.4) | (M3.5) | |

| Model1 | Model1+ Age_65over | Model1+ Age_65over +White | Model1+ Age_65over +Black |

Model1+ Age_65over+ Asian |

Model1 Age_65over+ Indian |

Model1+ Age_65over Hispanic |

|

| R-squared | 0.696 | 0.744 | 0.749 | 0.744 | 0.762 | 0.745 | 0.747 |

| State (NM*) | |||||||

| AZ | -4.930 | -5.760 | -6.362 | -5.761 | -5.904 | -5.939 | -6.383 |

| (0.002) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| CA | 1.444 | 1.332 | 1.282 | 1.328 | -0.390 | 1.481 | 0.657 |

| (0.240) | (0.238) | (0.253) | (0.240) | (0.732) | (0.202) | (0.577) | |

| TX | -10.910 | -9.646 | -9.791 | -9.692 | -9.864 | -9.517 | -10.106 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Metro Status | -1.992 | -0.732 | -0.575 | -0.734 | -0.985 | -0.653 | -0.747 |

| (0.003) | (0.254) | (0.369) | (0.254) | (0.113) | (0.320) | (0.242) | |

| Border County | -0.079 | -1.846 | -1.063 | -1.815 | -1.491 | -1.733 | -1.263 |

| (0.938) | (0.053) | (0.290) | (0.066) | (0.107) | (0.076) | (0.206) | |

| Unemployment | -0.373 | -0.410 | -0.438 | -0.411 | -0.314 | -0.420 | -0.412 |

| (0.046) | (0.017) | (0.011) | (0.017) | (0.061) | (0.015) | (0.016) | |

| Democrat_pct | 0.206 | 0.206 | 0.183 | 0.206 | 0.174 | 0.203 | 0.213 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Farmworker | 0.168 | 0.054 | 0.062 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.086 |

| (0.015) | (0.402) | (0.337) | (0.398) | (0.424) | (0.412) | (0.200) | |

| Rural_pct | 0.040 | 0.005 | 0.0005 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.003 | -0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.705) | (0.970) | (0.714) | (0.335) | (0.787) | (0.866) | |

| HS graduate | 0.326 | 0.172 | 0.160 | 0.171 | 0.166 | 0.171 | 0.137 |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.004) | |

| Income | 0.52e-05 | 1.57e-05 | 1.67e-05 | 1.60e-05 | -1.53e-05 | 1.63e-05 | 1.18e-05 |

| (0.792) | (0.389) | (0.356) | (0.385) | (0.412) | (0.370) | (0.517) | |

| Age_65over | 0.484 | 0.520 | 0.485 | 0.495 | 0.491 | 0.459 | |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | -0.071 | 0.006 | 0.383 | 0.023 | -0.034 | ||

| (0.019) | (0.904) | (<0.001) | (0.577) | (0.060) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).