1. Introduction

Sorghum aphids are key insect pests that affect sorghum throughout its developmental stages. Their feeding activity causes direct tissue damage, and the viruses they transmit can further aggravate yield reduction, collectively posing a serious threat to both crop productivity and quality. Currently, chemical pesticides remain the dominant strategy for the management of sorghum pests, diseases, and weeds. Studies have shown that pesticide use can help recover approximately 20%–25% of the global annual crop yield that would otherwise be lost [

1]. Nevertheless, Excessive pesticide spraying not only leads to the accumulation of chemical residues in crops but also exacerbates environmental pollution. This highlights the urgent need for precision spraying technology, which enables precise application of pesticides by accurately detecting pest species and their spatial distribution. This approach can effectively reduce pesticide pollution, significantly improve spraying efficiency, and minimize pesticide waste.

To detect pests in crop production, various methods have been developed [

2,

3], which can be broadly categorized into machine learning approaches [

4] and deep learning techniques [

5,

6,

7]. In pest image analysis, segmentation plays a crucial role as it enables precise localization of insect body regions. Among traditional image processing approaches, Kumar et al. [

8] proposed a computationally efficient detection algorithm combining median filtering with adaptive threshold segmentation. By optimizing the denoising-segmentation workflow, it achieved over 95% accuracy in complex backgrounds. Zhang et al. [

9] applied a composite gradient watershed algorithm to segment pest images, demonstrating lower relative errors compared to conventional methods. Subsequently, Deng et al. [

10] enhanced image segmentation for corn pest detection by integrating an improved GrabCut algorithm with saliency and depth information, achieving high accuracy with minimal manual intervention. While these methods demonstrate strong performance in specific scenarios, they typically rely heavily on manual parameter tuning and exhibit limited generalization capabilities when applied to more diverse pest image datasets.

The rapid advancement of deep learning has largely addressed the shortcomings of traditional machine learning approaches in feature extraction. Extensive research demonstrates that convolutional neural network (CNN)-based architectures can achieve remarkable results in pest detection and classification. For instance, Liu et al. [

11] proposed PestNet, while Wang et al. [

12] enhanced pest detection recall by designing a sampling-balanced Region Proposal Network (RPN). Wang et al. [

13] introduced DeepPest for large-scale multi-species datasets, while Domingues et al.’s [

14] review emphasized that integrating CNNs with heterogeneous data sources—such as meteorological variables and remote sensing imagery—enhances pest prediction accuracy. Despite these advances, most approaches focus on object detection, which provides only category labels and coarse bounding boxes—insufficient for fine-grained insect-level segmentation tasks. Furthermore, these methods typically require labor-intensive annotated datasets and substantial training time [

15]. CNN-based detectors like YOLO [

16], SSD [

17], and Faster R-CNN [

18] are also constrained by limited receptive fields, hindering their ability to capture the complex global context unique to field pest images.

With advances in semantic segmentation, deep learning has increasingly been applied to pixel-level pest identification. Zhao et al. [

19] leveraged transfer learning to achieve instance segmentation, while Shen et al. [

20] developed an enhanced deep learning–based system that supports efficient pest monitoring in grain storage through data augmentation and model refinement. Nevertheless, Kumar et al. [

21] identified the constrained receptive fields in their CNN architecture as a fundamental limitation for capturing long-range dependencies within leaf lesion patterns. Although Vision Transformers (ViT) have demonstrated strong global representation capabilities in many vision tasks [

22], and related architectures such as the multi-scale convolution-capsule network proposed by Xu et al. [

23] also benefit from modeling long-range dependencies, their quadratic computational complexity limits deployment on resource-constrained platforms—such as mobile devices, IoT terminals, and unmanned aerial systems—especially when processing the high-resolution images commonly encountered in field environments. These limitations become more pronounced under the highly heterogeneous field conditions described below, where small, densely clustered insects must be segmented from complex backgrounds.

As shown in

Figure 1, images of sorghum aphids collected from real field environments exhibit significant variability across different scenarios. These complex conditions introduce substantial challenges for segmentation, including varying illumination, dense clustering of pests, and intricate leaf textures in the background. Sorghum aphids may cluster densely along leaf veins or be sparsely distributed across leaf surfaces; their body sizes vary considerably, and their postures also show distinct differences. Their spatial arrangement is highly irregular, and illumination is affected by factors such as direct sunlight, shadows, and specular reflections from leaf surfaces. Additionally, the background contains complex leaf textures, curled structures, and various occluding objects. Collectively, these characteristics pose considerable challenges for detecting small insects, segmenting dense clusters, and extracting multi-scale features, thereby demanding greater robustness from both traditional techniques and current deep learning models. However, existing pest segmentation frameworks rarely integrate frequency-domain priors with lightweight multi-scale attention mechanisms under real-time constraints, particularly in complex agricultural settings—especially for small, densely clustered sorghum aphids.

To address these challenges, we introduce FESW-UNet, a dual-domain attention network that integrates frequency-domain cues with spatial attention mechanisms. The architecture enhances the UNet backbone through four synergistic components. Specifically, we employ the Efficient Multi-scale Aggregation (EMA) module to strengthen semantic representations, thereby ensuring resilience to the scale variations common in field scenarios. Simultaneously, we incorporate the Similarity-Aware Activation Module (SimAM) alongside a hybrid loss design; this amplifies the saliency of aphid regions and accelerates convergence. For efficient feature compression, Haar wavelet-based downsampling (HWD) replaces standard operations to preserve high-frequency boundary details while reducing computational overhead. Completing the architecture, the Fourier-enhanced attention module (FEAM) fuses spatial structures with frequency-domain features, effectively mitigating the impact of uneven illumination and complex background interference.

Experimental evaluations confirm that FESW-UNet outperforms several segmentation models on both the Aphid Cluster Segmentation and AphidSeg-Sorghum datasets. The model achieves superior mIoU and mPA while maintaining real-time inference speeds, providing a solid technical foundation for precision pest management. The major contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) We present FESW-UNet, a dual-domain attention network built upon UNet, which achieves substantial performance gains while maintaining real-time applicability on sorghum aphid segmentation tasks.

(2) We design a Fourier-enhanced attention module (FEAM) and embed it into the skip connections of UNet to jointly leverage spatial structural cues and frequency-domain texture information, thereby improving aphid-region discrimination under complex backgrounds.

(3) We constructed the AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset for sorghum aphids and verified the adaptability and effectiveness of FESW-UNet on the AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset.

2. Materials

In this study, the Aphid Cluster Segmentation Dataset published by Rahman R. et al. [

24] was initially employed as the main experimental dataset. Before use, the images underwent a series of preprocessing steps, including quality screening, removal of out-of-focus samples, and exclusion of unusable images. After cleaning, 7,720 high-quality aphid images were retained. The dataset provides sorghum leaf photos collected under diverse real-world field conditions, incorporating a wide range of illumination types (e.g., strong sunlight, diffuse lighting, shaded environments, and reflective surfaces), background textures (such as leaf venation, curled leaves, soil, and weed interference), and multiple degrees of aphid aggregation and infestation. This variability results in substantial scene complexity, making the dataset a valuable benchmark for testing segmentation model robustness in challenging agricultural environments and for ensuring the reliability and generalizability of the experimental results.

To further examine the model’s performance across different acquisition environments and data domains, we additionally curated a sorghum aphid image dataset, named AphidSeg-Sorghum. The images were captured at the Experimental Laboratory of the Engineering Research Center for Special Sorghum for Liquor Production, Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, as well as at the Wuliangye sorghum planting base. Mobile phones served as the imaging devices, enabling the collection of multi-angle and multi-scale samples of infested regions under varying lighting conditions, time periods, viewpoints, and distances to simulate real field monitoring scenarios. We manually produced pixel-level annotations using the Labelme tool. This process guarantees accurate and consistent labels for supervised learning. As shown in

Figure 2, the sorghum aphid regions are annotated in red. After cleaning, 612 original images were retained. To enhance data diversity and improve the model’s robustness in complex scenarios, we applied data augmentation strategies such as horizontal/vertical flipping, brightness adjustment, and noise injection to verify the cross-domain generalization ability and overall stability of the proposed method on the AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset.

A concise summary of the two datasets is provided in

Table 1. All data were partitioned into training and testing subsets using a 7:3 ratio to maintain both sufficient training samples and representative evaluation data.

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Architecture of FESW-UNet

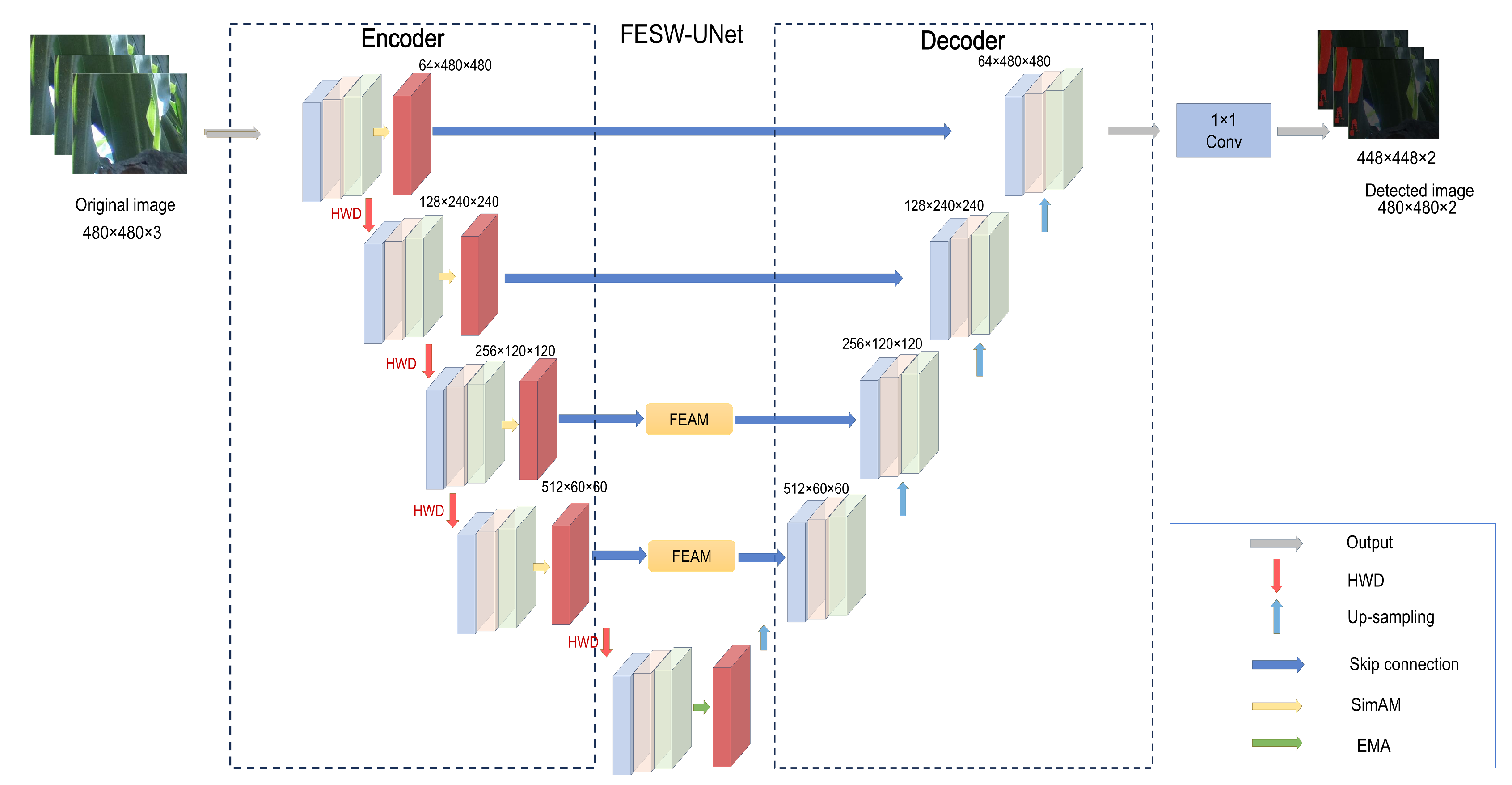

The architecture of FESW-UNet, illustrated in

Figure 3, extends the classic UNet encoder–decoder framework by integrating four task-specific modules to establish a progressive feature-optimization pipeline. In the encoding stage, we embed SimAM blocks to provide parameter-free, pixel-level attention; this mechanism amplifies aphid-specific signals while actively suppressing environmental noise such as leaf veins, reflections, and shadows. To further prevent the spatial detail loss typical of standard stride-2 convolutions, we utilize the HWD module for downsampling. By decomposing features into frequency subbands via Haar wavelets, HWD reduces computational cost while explicitly preserving edge information. At the network bottleneck, where feature maps are semantically rich, an EMA module is inserted to adaptively fuse multi-scale contextual information, strengthening the link between global structures and local details to accommodate large variations in pest scale. Finally, during the decoding phase, we apply the FEAM module to optimize skip-connection features. FEAM modulates low-frequency structures and high-frequency details using complex-valued weights in the frequency domain before merging them back into the spatial domain. This cooperative design effectively balances spatial fidelity with spectral analysis, yielding robust feature learning and high segmentation accuracy in challenging agricultural scenarios.

3.2. EMA Module

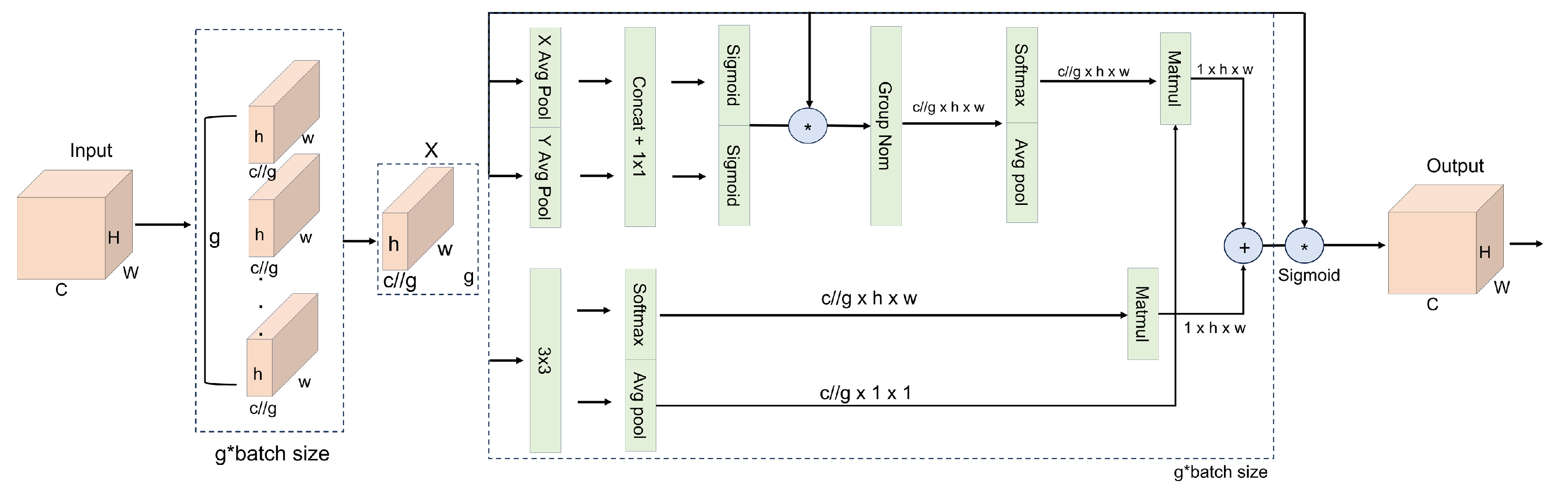

The EMA module [

25] computes multi-scale attention and jointly captures global and local contextual cues, enabling the network to consistently focus on aphid-related features even under complex field conditions (e.g., varying illumination, strong leaf-texture patterns, and curled leaf surfaces), as shown in

Figure 4. In this module,

and

denote one-dimensional global average pooling operations along the horizontal (width) and vertical (height) directions, respectively, and

represents a channel-recalibration vector. For an input feature map

, EMA partitions the

C channels into

g groups, with each group learning complementary semantic cues (e.g., separating leaf-vein structures from aphid clusters or distinguishing dense aphid aggregations from sparse distributions). This grouping design, together with directional pooling, helps suppress structured background interference (such as soil, leaf veins, or specular reflections) while enhancing the contrast between aphid regions and their surroundings. By jointly leveraging grouped features and anisotropic pooling, EMA strengthens the association between global leaf geometry and local aphid appearance, thereby improving the model’s stability and robustness under varying lighting and scale conditions.

The spatial attention map in EMA is generated by three parallel branches: two convolutional pathways and one convolutional pathway. The branches, combined with and , encode directional information along the horizontal and vertical axes, making the network more sensitive to subtle boundary transitions and helping it better distinguish aphids from strong vein textures or reflective artifacts. The branch focuses on local morphological and contextual dependencies that are closely related to aphid clustering. In particular, the paths first aggregate responses along each spatial dimension via one-dimensional global pooling, and then incorporate broad spatial context through subsequent two-dimensional pooling, whereas the path enriches localized structural details. The outputs of all branches are fused and passed through a Sigmoid function to produce the final spatial attention map, which amplifies fine-grained aphid-related cues while preserving essential spatial structures. In dynamically changing field environments, EMA thus adaptively balances global leaf-level structure with local aphid-level patterns, suppresses illumination- and texture-induced noise, and sharpens weak boundaries, contributing to more reliable aphid extraction and improved overall segmentation accuracy.

3.3. SimAM Module

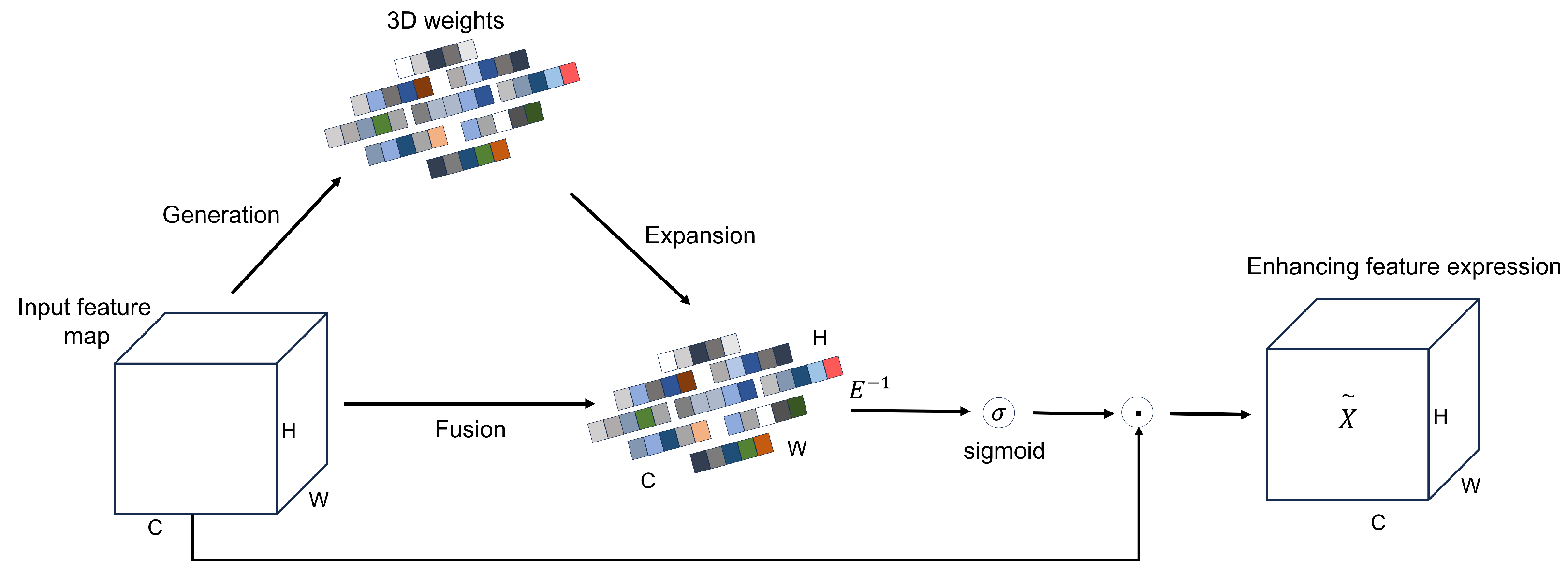

Sorghum aphid detection faces challenges due to blurred patterns and low contrast against complex backgrounds. Additionally, practical monitoring systems demand fast inference speeds. We addressed these issues by embedding the SimAM attention module [

26] into the feature extraction pipeline (

Figure 5). SimAM functions as a parameter-free mechanism that models feature responses to identify key regions automatically. It performs pixel-wise reweighting to emphasize aphid-related cues while suppressing background noise.This refinement promotes more efficient feature propagation and enhances the model’s stability and precision when dealing with complex agricultural field environments, especially in low-contrast scenes with strong leaf-vein or reflection interference.

Given an input feature map of size

, SimAM estimates a 3D importance map by assigning an energy value to each neuron through an energy function, as defined in Eq. (

1). The energy for neuron

t is given by

where

denotes the energy of neuron

t, and

and

represent the weight and bias of the linear transformation, respectively. The variable

is the output of neuron

t on the current channel,

M denotes the number of neurons in that channel,

is the output of neighboring neurons, and

represents the surrounding neuron values (with

and

denoting their corresponding linear estimates). Intuitively, this formulation penalizes large deviations between the response of neuron

t and that of its neighborhood, so that neurons with responses very different from their surroundings are assigned lower energy (i.e., higher importance).

Assuming that all pixels within a single channel follow the same distribution, the importance of each independent neuron can be further expressed by the following minimum-energy formulation, as given in Eq. (

2):

where

and

denote the mean and variance of all neurons in the channel, and

is a small regularization term. The value

reflects the importance of neuron

t: a smaller energy corresponds to a larger deviation from its neighborhood and thus a stronger linear separability. Therefore, SimAM adopts

as the basis for computing attention weights. Let

E denote the energy map composed of all

values over the feature map; after applying a Sigmoid-based normalization to obtain the attention weights, the enhanced feature map

is computed by element-wise multiplication with the original feature map

X, as formulated in Eq. (

3):

By reweighting features according to the inverse energy map, SimAM suppresses neurons with high energy (low importance) and amplifies those with low energy (high importance). In the context of sorghum aphid segmentation, this mechanism strengthens responses in aphid-infested regions while down-weighting background structures such as leaf veins, glare, and shadows, thereby improving local contrast and boundary clarity without introducing additional learnable parameters or noticeable computational overhead.

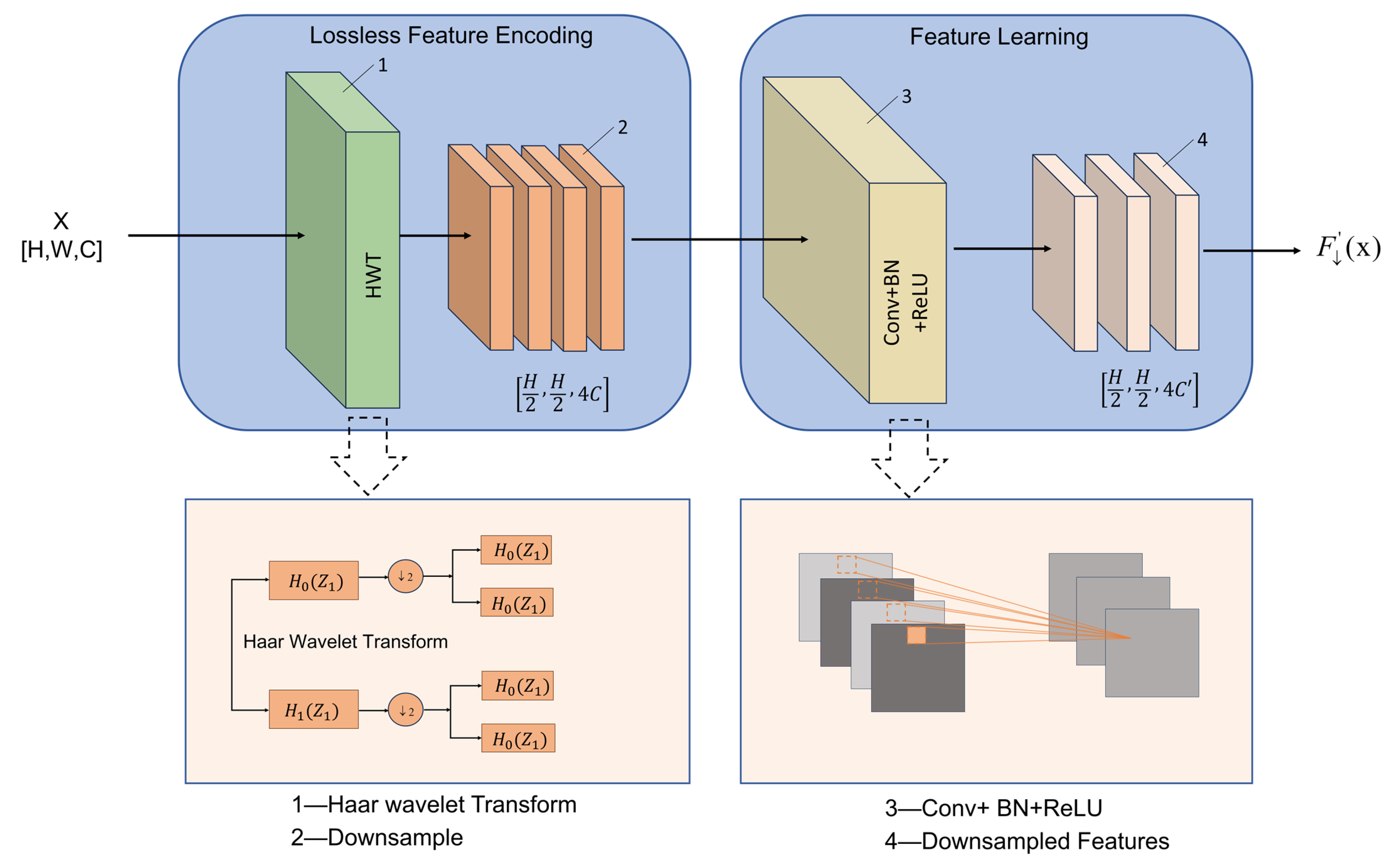

3.4. HWD Downsampling

In the UNet framework, conventional max-pooling layers reduce feature-map resolution and highlight high-response regions; however, they only preserve the maximum activation within each local window while discarding the remaining pixel information. As a result, important texture cues, boundary details, and structural patterns may be lost, often leading to blurred edges and distorted spatial representations. This issue is particularly critical in sorghum aphid segmentation, where aphids in field images are generally small, irregularly distributed, and easily confused with strong leaf-vein textures and complex illumination effects (e.g., shadows and specular reflections). Under such conditions, traditional downsampling operations struggle to maintain a balance between global semantic consistency and the preservation of fine-grained local structural information. To alleviate this problem, this study incorporates the Haar Wavelet Downsampling (HWD) [

27] module into the UNet encoder. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the HWD module mainly consists of an information-preserving feature-encoding submodule and a feature-representation learning submodule. The feature-encoding component applies the Haar wavelet transform to an input feature map of size

with

C channels, decomposing it into four subbands: an approximation subband (A) and three detail subbands corresponding to horizontal (H), vertical (V), and diagonal (D) orientations. By jointly applying the low-pass filter

and high-pass filter

along both spatial dimensions, these subbands together perform the downsampling operation, reducing the spatial size of each output feature map to

while expanding the channel dimension to four times that of the input. This orthogonal spatial–frequency decomposition is theoretically invertible and preserves key structural textures, while still reducing spatial resolution and data redundancy. The one-dimensional Haar basis functions

and wavelet functions

used for feature decomposition are defined in Eq. (

4):

where the Haar scaling function

is given by Eq. (

5):

with

j denoting the scale (corresponding to the depth of the convolutional layers in the image domain) and

k representing the index of the Haar basis function.

The feature-representation learning submodule consists of a standard convolution layer, a batch-normalization layer, and a ReLU activation function. In this submodule, the convolution is used to maintain compatibility with subsequent layers and to adjust the number of feature channels, while helping to suppress redundant responses and highlight informative components. The learnable parameters facilitate the adaptive fusion of distinct frequency bands by reweighting directional subbands. This mechanism selectively enhances high-frequency features to resolve irregular boundaries in dense aphid clusters. Simultaneously, for smooth background areas, the network strengthens low-frequency components to maintain global structure and minimize environmental noise. Through this multi-level frequency–spatial collaboration during downsampling, the HWD module not only reduces information redundancy but also improves the fidelity of feature representations, providing FESW-UNet with more effective feature compression and structural preservation in complex sorghum field environments.

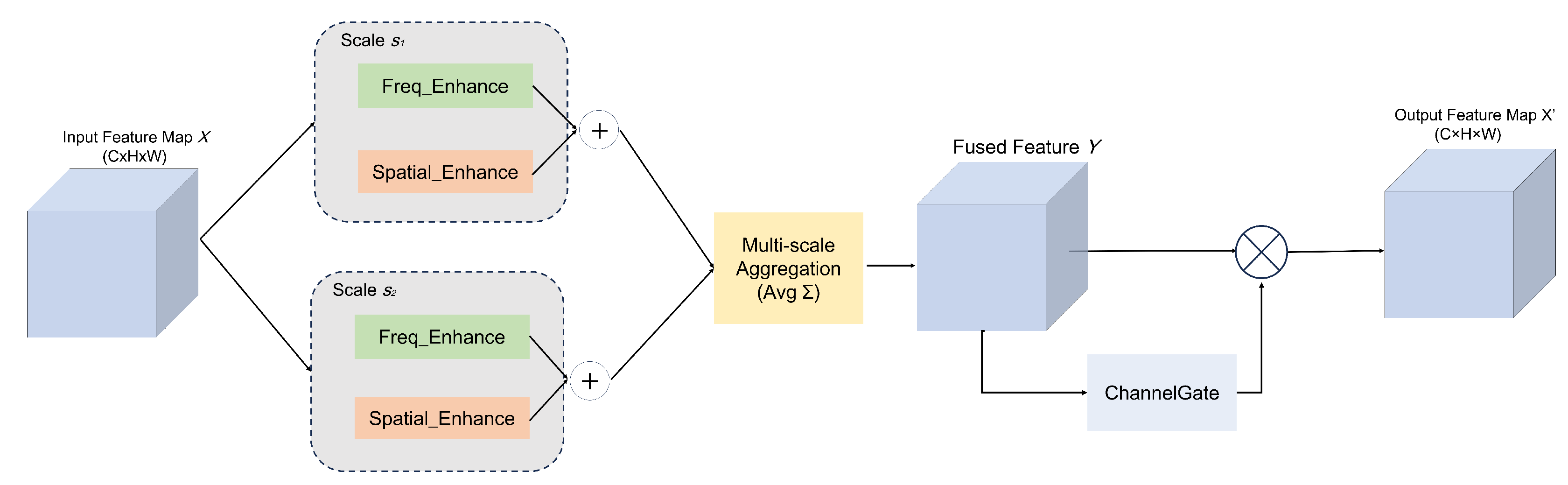

3.5. FEAM Module

To enhance the real-time segmentation capability for sorghum aphids, this study introduces an improved Fourier-Enhanced Attention Module (FEAM) into the skip-connection layers of UNet. As shown in

Figure 7, field images are often affected by diverse factors such as strong or uneven illumination, complex leaf-vein textures, and the coexistence of densely clustered and sparsely distributed aphids. Under these conditions, purely spatial-domain processing or purely frequency-domain processing alone often fails to simultaneously capture both global structural patterns and fine-grained texture details.

Inspired by the spectral gating mechanism proposed in SpectFormer [

28], FEAM adopts a dual-domain, multi-scale collaborative strategy: complex-valued weights are learned at a set of predefined spatial resolutions (e.g.,

and

) and projected to the current feature-map scale, after which features are modulated separately in the frequency and spatial domains. The outputs of these dual branches are then fused through a multi-scale aggregation mechanism and a channel-gating module to generate cross-domain enhanced representations, enabling the network to more stably highlight aphid boundaries and body textures against complex field backgrounds.

Given an input feature map

, we follow the spectral gating formulation of SpectFormer and learn, for each scale

(e.g.,

), a complex-valued weighting map

:

where

denote the real and imaginary parts, respectively. Bilinear upsampling

is applied to match the spatial resolution of

X, yielding

and

. These maps are then broadcast along the channel dimension to obtain tensors in

, which are used to modulate features at each scale.

In the frequency-enhancement branch, a unitary Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [

29] is first applied to

X, denoted as

, and its inverse counterpart (IFFT)

ensures energy consistency when mapping back to the spatial domain. The frequency-domain modulation at scale

s is then given by:

where ⊙ denotes elementwise complex multiplication in the frequency domain. When

or

increases at certain locations, the corresponding frequency bands are amplified (enhancing aphid edges and fine structural details); when

, those bands are attenuated, which helps suppress reflection- or noise-dominated components.

At the same time, to avoid potential spatial artifacts caused by modulation exclusively in the frequency domain, FEAM introduces an additional spatial-domain pixel gate

. Specifically, the real part of the complex weight is used as a pixel-wise scaling factor:

where ⊙ now denotes elementwise multiplication in the spatial domain. The broadcasted

ensures that all channels at the same spatial location are modulated consistently, directly enhancing responses in aphid regions while suppressing leaf-vein and shadow backgrounds. This design helps maintain boundary continuity and strengthens activation in dense aphid clusters or low-contrast areas.

The enhanced features from the dual branches are aggregated over all scales

and fused via a simple multi-scale merge, computed as:

where

Y denotes the multi-scale, dual-domain fused feature map. Subsequently, a channel attention mechanism (Channel Gate) [

30] is applied to adaptively reweight feature channels according to their task relevance:

where ⊙ again indicates elementwise multiplication, and

outputs a channel-wise importance vector that highlights informative channels while suppressing less useful ones.

Compared with conventional approaches that operate exclusively in either the spatial or frequency domain, this dual-domain, multi-scale attention design synergistically integrates complementary cues. By simultaneously capturing global low-frequency structures and localized high-frequency details while enabling precise frequency band modulation, the module enriches feature representation and theoretically enhances robustness against complex field conditions.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

All experiments were conducted on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04.6, equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4210R CPU @ 2.40 GHz and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU (10 GB VRAM). The deep learning models were implemented using PyTorch 2.0.1 with CUDA 12.2 acceleration. To maintain consistency, identical hyperparameters were applied across all networks: input images were resized to , the batch size was set to 8, and training proceeded for 100 epochs. We used an initial learning rate of 0.001, which was adjusted using a standard step-based decay strategy.

For optimization, we utilized the Adam optimizer to update network parameters. All models, including the baseline networks and the proposed FESW-UNet, were trained from scratch using the same data preprocessing pipeline and training–validation splits. This unified framework ensures that any observed performance differences result solely from model architectural variations.

Table 2.

Training environment settings.

Table 2.

Training environment settings.

| Category |

Component |

Specification |

| [-0.8em]Hardware environment |

CPU |

Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4210R @ 2.40 GHz |

| |

GPU |

NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 (10 GB VRAM) |

| |

RAM |

32 GB |

| Software environment |

Operating system |

Ubuntu 20.04.6 |

| |

Deep learning framework |

PyTorch 2.0.1 |

| |

Python |

3.8 |

| |

CUDA Toolkit |

CUDA 12.2 |

4.2. Evaluation Indicators

In this study, mIoU, mPA, Accuracy, and mRecall are adopted as common evaluation metrics to assess the performance of FESW-UNet on the sorghum aphid segmentation task. mIoU represents the mean intersection-over-union between the ground-truth labels and the predicted results and reflects how accurately the target regions are localized. mPA denotes the mean pixel accuracy over all categories, i.e., the average of per-class pixel accuracy. Both indices take values in the range

, where values closer to 1 indicate better segmentation performance. Their definitions are as follows:

where

K denotes the number of classes,

represents the number of pixels of class

i that are correctly predicted as class

i,

represents the number of pixels belonging to class

i but predicted as class

j, and

represents the number of pixels belonging to class

j but predicted as class

i.

Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly predicted pixels among all pixels and is computed as:

where

,

,

, and

denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Recall represents the proportion of correctly predicted positive pixels among all ground-truth positive pixels and is defined as:

where

and

correspond to true positives and false negatives of class

i. The mean Recall (mRecall) is then calculated as:

Together with FPS (frames per second), which reflects the inference speed of different models, these metrics jointly evaluate both the segmentation accuracy and the computational efficiency of the proposed FESW-UNet and the baseline methods.

4.3. Model Comparative Experiments

To thoroughly assess the performance of the proposed FESW-UNet in sorghum aphid segmentation, extensive comparative experiments were performed on the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset, a publicly available aphid segmentation benchmark. This dataset encompasses diverse interference factors—including soil background, leaf-texture variability, and illumination changes—which preserve the controllability of laboratory conditions while effectively simulating the complexity of real field environments, thereby enabling a reliable evaluation of model robustness. As presented in

Table 3, FESW-UNet attains the highest overall performance among all comparison models, achieving an mIoU of 68.76%, mPA of 78.19%, Accuracy of 93.32%, and mRecall of 78.19%. Relative to the baseline UNet, which yielded an mIoU of 66.31%, mPA of 75.79%, Accuracy of 92.65%, and mRecall of 75.79%, the proposed model improves these metrics by 2.45, 2.40, 0.67, and 2.40 percentage points, respectively. These gains can be attributed to the targeted architectural refinements: the SimAM module enhances salient aphid-region representation while suppressing background disturbances; EMA’s multi-scale dynamic weighting strengthens the model’s capability to handle scale variations under field conditions; the HWD wavelet-based downsampling retains essential texture cues during resolution reduction, maintaining feature continuity; and FEAM further improves stability and detail preservation under complex light–shadow interactions by jointly leveraging frequency- and spatial-domain information. Compared with mainstream segmentation networks such as PSPNet, DeepLabv3+, Hernet, LR-ASPP, SegNet, UNet

2, LinkNet, SegFormer, and FastSCNN, FESW-UNet exhibits clear advantages across all four evaluation metrics, particularly demonstrating superior consistency and boundary discrimination in scenes with concurrent strong reflections and shadow occlusion. Although the parameter count shows a slight increase (approximately 32.76M compared with the baseline’s 31.03M), the overall model remains compact and computationally efficient, achieving a well-balanced trade-off between segmentation accuracy and inference efficiency.

We extended the evaluation of FESW-UNet’s adaptability and cross-domain generalization ability across diverse environments. Specifically, additional comparative experiments were carried out on the AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset. As summarized in

Table 4, this dataset—collected directly from real sorghum fields—contains more substantial illumination fluctuations, texture-induced noise, and morphological variability in aphid clusters, thereby imposing stricter robustness demands on segmentation models. The results indicate that FESW-UNet attains the highest performance across all evaluation metrics, achieving an mIoU of 81.22%, mPA of 87.97%, Accuracy of 98.75%, and mRecall of 87.97%. Compared with the baseline UNet, these values correspond to improvements of 9.79, 10.55, 0.71, and 10.55 percentage points, respectively. FESW-UNet also consistently surpasses stronger competitors such as UNet

2, LinkNet, and FastSCNN. These findings confirm that—benefiting from SimAM’s saliency enhancement, EMA’s multi-scale dynamic modeling, HWD’s edge-preserving wavelet downsampling, and FEAM’s complementary integration of spatial- and frequency-domain cues—FESW-UNet can more effectively extract discriminative features, strengthen multi-scale semantic representation, and mitigate heavy background interference in noisy, texture-rich, and densely infested field scenarios, resulting in more reliable segmentation performance under cross-domain conditions.

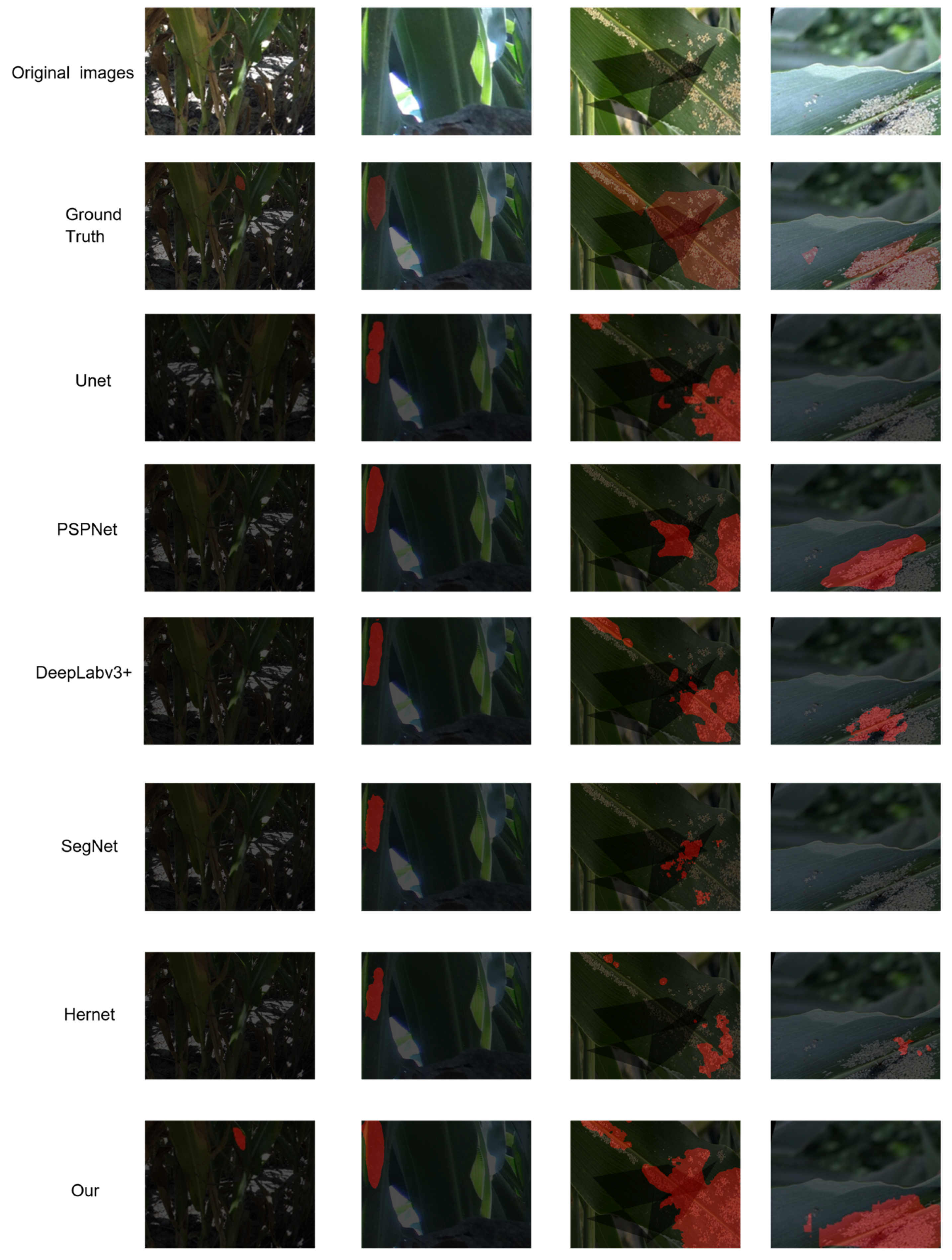

To more intuitively showcase the segmentation capability of the proposed model under challenging field conditions, six representative segmentation networks (UNet, PSPNet, SegNet, Hernet, DeepLabv3+, and FESW-UNet) were selected for qualitative comparison across several typical scenarios, as illustrated in

Figure 8. In the four displayed test images, the first two columns from the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset, and the last two columns are from the AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset; all predictions were generated using models trained exclusively on the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset to rigorously evaluate cross-domain generalization. The visual results reveal that FESW-UNet consistently delivers precise target localization and clear boundary delineation in environments with uneven lighting, intricate background textures, and densely aggregated aphid populations. For instance, in the first column’s low-contrast and weak-illumination scene, FESW-UNet successfully reconstructs complete aphid contours, whereas other models exhibit noticeable omissions. In the second column, most conventional models detect only small portions of aphid regions and fail to capture the full target area, while FESW-UNet achieves better regional integrity and connectivity. The third column shows that many competing models suffer from both under-segmentation and over-segmentation in complex textured backgrounds; in contrast, FESW-UNet—benefiting from the frequency-domain enhancement of FEAM and the edge-preserving nature of HWD downsampling—produces more coherent and stable segmentation maps. In the fourth column, characterized by strong illumination overlapping with shadowed portions, FESW-UNet continues to effectively discriminate aphids from the leaf surface, whereas PSPNet, DeepLabv3+, SegNet, and Hernet display frequent misclassifications and boundary inconsistencies.

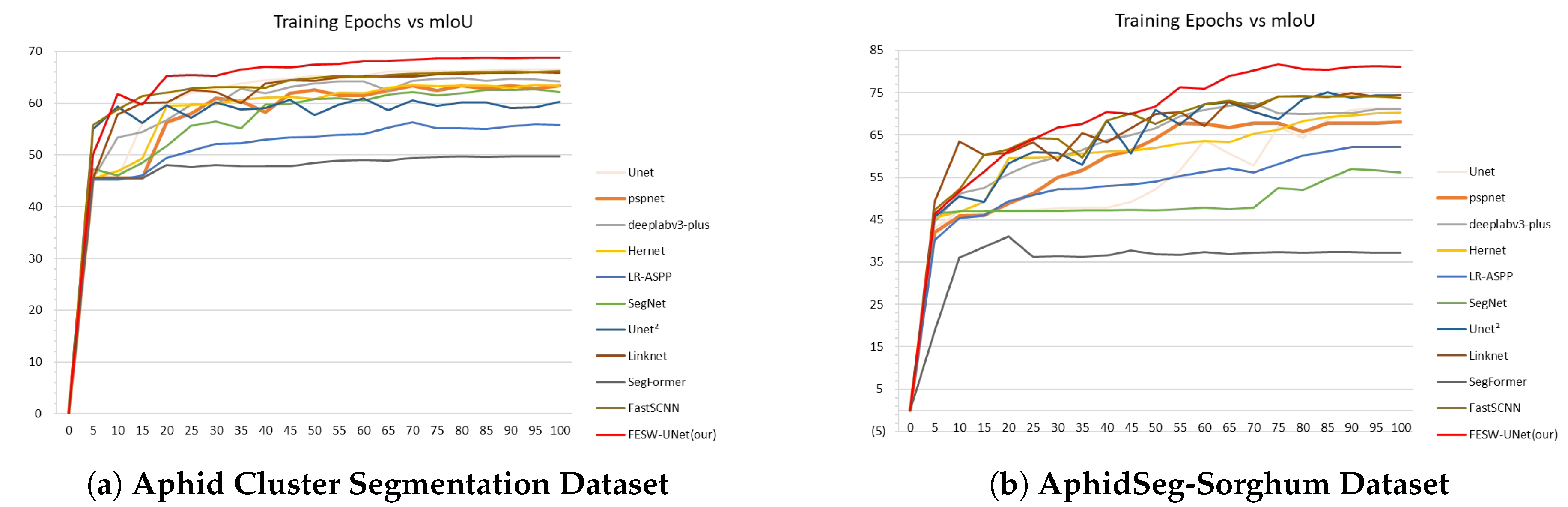

Furthermore,

Figure 9 illustrates the mIoU comparisons between FESW-UNet and mainstream networks. Subfigure (a) corresponds to the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset. Subfigure (b) corresponds to the AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset. The curves demonstrate the stability and fast convergence speed of our model. These results further confirm the effectiveness and robustness of FESW-UNet.The results show that although FESW-UNet performs similarly to, or slightly below, other models in the early training stages, its performance steadily increases as training continues, and the final curve converges at the highest level among all methods. This trend indicates that FESW-UNet can quickly acquire key discriminative patterns while suppressing noise, demonstrating efficient learning behavior and stable convergence. One plausible explanation is that the additional attention and frequency-domain modules require a short warm-up phase to learn meaningful weights but subsequently provide stronger regularization and more expressive feature modeling. Owing to its multi-scale and dual-domain feature enhancement strategies, FESW-UNet exhibits stronger generalization capability and a reduced tendency to overfit. Overall, FESW-UNet not only achieves superior final segmentation accuracy compared with existing models but also demonstrates clear advantages in training stability and generalization performance.

In summary, the experimental findings confirm that FESW-UNet not only surpasses all comparison models in segmentation accuracy but also delivers excellent real-time inference performance and strong robustness in complex field environments. The model effectively handles challenging factors such as illumination changes, background clutter, and texture interference, producing more detailed, coherent, and stable aphid segmentation results. These outcomes suggest that FESW-UNet offers a precise, reliable, and practically deployable solution for real-world monitoring of sorghum aphid infestations.

4.4. The Effect of Different Numbers of FEAM Modules on FESW-UNet

As illustrated in

Figure 3, two Fourier-Enhanced Attention Modules (FEAMs) are progressively inserted along the UNet skip-connection pathway from deeper to shallower layers to form a fine-grained feature branch, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to capture high-frequency details and boundary structures. In the implementation phase, we instantiated a sequence of four FEAM blocks with predefined dual-scale settings spatial_scales = [30, 60], [60, 120], [120, 240], and [240, 480] for the four skip-connection levels, and the configurations “FEAM×1”, “FEAM×2”, “FEAM×3”, and “FEAM×4” correspond to activating the first one, two, three, and all four FEAM blocks in this list, respectively, so that each FEAM consistently operates on two spatial scales within its complex-modulation branch.

Since the number of stacked FEAM blocks may influence both the depth of feature extraction and the sensitivity to noise, we conducted an ablation study with different numbers of FEAM modules on the test split of the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset. As reported in

Table 5, the model performs best when two FEAMs are employed, achieving an mIoU of 68.76%, mPA of 78.19%, Accuracy of 93.32%, mRecall of 78.19%, and an FPS of 254.78. This configuration thus offers an effective balance between segmentation accuracy and efficiency, without substantially increasing the parameter count (32.756M).

Compared to the single FEAM configuration with an mIoU of 68.69% and mPA of 77.86%, the two-module configuration improves mIoU and mPA by 0.07 and 0.33 percentage points, respectively. This suggests that adding a second module further refines feature extraction and cross-scale integration. However, performance declines slightly when the number of FEAMs exceeds two (i.e., three or four modules), with mIoU dropping to 68.60% and 68.49%. We attribute this decline to increased network depth and redundancy, which may hinder gradient propagation and lead to overfitting given the current dataset size. Consequently, we adopted the two-module configuration for FESW-UNet, as it strikes the optimal balance between feature discrimination and inference speed.

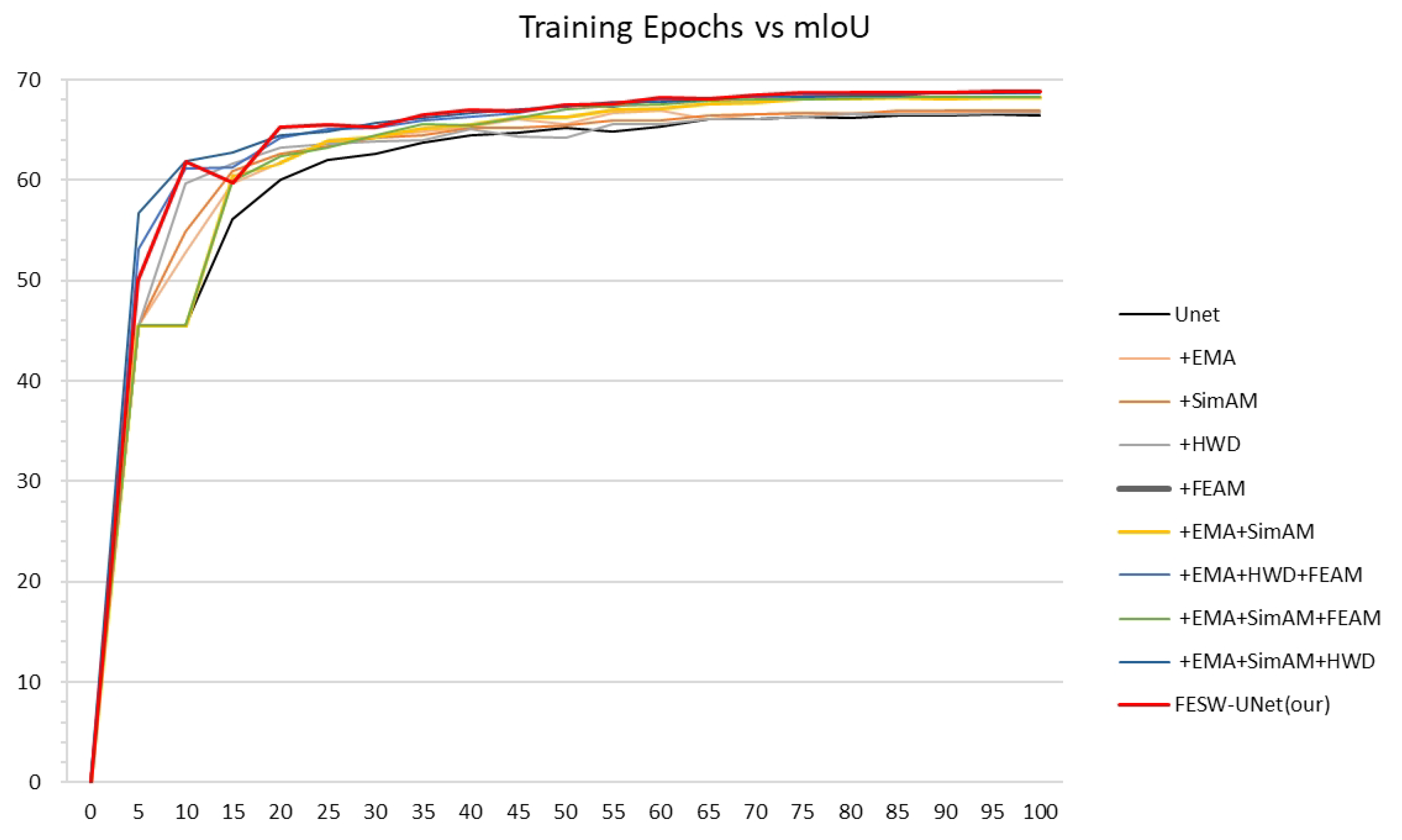

4.5. Ablation Study

To evaluate the contribution of each module, we conducted ablation experiments on the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset using UNet as the baseline (

Table 6). The results show that adding the Efficient Multi-scale Attention (EMA) module raised mIoU from 66.31% to 66.77% and mPA from 75.79% to 75.83%. These gains of 0.46 and 0.04 percentage points highlight EMA’s role in strengthening global feature representation. Incorporating the lightweight SimAM mechanism (+EMA + SimAM) resulted in mIoU and mPA values of 68.05% and 76.91%. While slightly different from using SimAM alone, this combination effectively enhances local feature activation while maintaining inference speed relative to the baseline. Integrating the Haar Wavelet Downsampling (HWD) module further improved performance, with the “+ EMA + SimAM + HWD” configuration reaching 68.62% mIoU and 77.67% mPA. The additional gains of 0.57% and 0.76% confirm that HWD preserves edge structures through wavelet decomposition, improving spatial detail without adding significant latency. Finally, the addition of the Fourier-Enhanced Attention Module (FEAM) completed the FESW-UNet architecture. Compared to the pre-FEAM configuration, FESW-UNet increased mIoU and mPA to 68.76% and 78.19%, respectively.

Figure 10 shows in detail the MIoU variation curves for each ablation experiment on the training set of the Aphid Cluster Segmentation dataset. These results validate the benefit of using frequency-domain information to refine feature extraction and suppress noise.

In conclusion, FESW-UNet outperformed the baseline UNet across all metrics, achieving absolute gains of 2.45% in mIoU, 2.40% in mPA, 0.67% in Accuracy, and 2.40% in mRecall. Notably, this accuracy improvement coincides with a significant rise in inference throughput: FPS increased from 214.71 to 254.78, an improvement of 40.07 FPS (approximately 18.7%). This demonstrates that the framework strikes an effective balance between segmentation performance and computational efficiency. The four modules exhibit clear complementarity: EMA handles global semantics, SimAM targets local regions, HWD preserves spatial structures, and FEAM refines details via frequency cues. despite the added complexity, the total parameter count remains within the 31–33 million range, confirming that performance gains stem from efficient design rather than model inflation. Thus, FESW-UNet delivers high-precision segmentation and real-time processing suitable for challenging field conditions.

5. Discussion

Our empirical results confirm that integrating frequency-domain analysis with spatial attention mechanisms effectively addresses the limitations of conventional CNNs in precision agriculture. While standard UNet architectures provide a functional baseline, they often fail to retain the high-frequency structural integrity of small, densely clustered aphids during encoding and reconstruction. Our architectural improvements specifically target these biological and environmental challenges. Critical to this process is the HWD module, which acts as a spectral filter to decompose features into frequency subbands. Unlike max-pooling, which tends to discard texture cues indiscriminately, HWD explicitly preserves the edge information of tiny aphids. This structural preservation works alongside the dynamic modulation of SimAM and EMA, which suppress background noise and recalibrate global context to handle variable infestation patterns. Finally, the FEAM module completes this design by strengthening the skip connections to bridge the semantic gap between the encoder and decoder. By harmonizing spatial structures with complex-valued frequency weights, FEAM ensures that fine-grained texture details from early layers are accurately recovered during upsampling, preventing the feature dilution common in standard decoding schemes. This design gives the model the adaptability required to handle the highly variable field conditions observed in our experiments.

Comparing FESW-UNet with other mainstream segmentation models clearly demonstrates the advantages of the proposed dual-domain strategy. While SegFormer is great at modeling long-range dependencies, its lower performance in our tests indicates difficulty capturing the fine local textures needed to identify small, densely clustered aphids. Similarly, compared to DeepLabv3+, which often produces coarse segmentation boundaries due to resolution loss inherent in dilated convolutions, FESW-UNet addresses this issue through the spectral gating mechanism of the FEAM module. By selectively amplifying high-frequency components, FEAM functions as a global sharpening filter that separates pest boundaries from complex backgrounds. Furthermore, compared to lightweight models prioritizing inference speed over complex feature extraction (e.g., FastSCNN), our proposed framework achieves higher accuracy through robust multi-scale integration using EMA and SimAM. This demonstrates that FESW-UNet effectively balances the deep feature representations typically lacking in lightweight networks with the boundary precision missing in heavier backbones, while maintaining real-time efficiency suitable for field deployment.

Beyond its outstanding segmentation accuracy, FESW-UNet also demonstrates exceptional adaptability across diverse datasets and impressive model inference speed. Experiments demonstrate that the model extracts robust, universal features from heterogeneous datasets, overcoming overfitting issues in single-environment scenarios. Simultaneously, it strikes an excellent balance between complexity and speed, maintaining real-time inference performance suitable for field deployment even with integrated FFT modules. This dual-domain architecture proves that segmentation accuracy and edge detail can be significantly enhanced with minimal latency trade-offs, fully meeting the stringent requirements of real-time agricultural monitoring.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed FESW-UNet, a dual-domain attention network designed to tackle the long-standing trade-off between segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency in sorghum aphid monitoring. By strategically embedding frequency-aware mechanisms into the UNet backbone, we constructed a framework capable of extracting fine-grained aphids features even against complex agricultural backgrounds. A central contribution of this work is the development of a unified architecture that effectively combines wavelet-based structural preservation, multi-scale semantic aggregation, and Fourier-guided spectral refinement. This design shifts the feature extraction process from a static spatial operation to a dynamic, frequency-aware analysis. As a result, the model can simultaneously suppress environmental interference—such as variable illumination and leaf textures—while preserving the critical morphological details of small, clustered pests, offering a feasible technical solution for precise pesticide application.

Comprehensive experiments on both the Aphid Cluster Segmentation Dataset and our self-collected AphidSeg-Sorghum dataset validate this approach. Quantitative results indicate that FESW-UNet consistently outperforms widely used segmentation models, securing mIoU scores of 68.76% and 81.22%, respectively. These figures represent significant improvements of 2.45% and 9.79% over the baseline UNet, highlighting the model’s superior ability to distinguish pest regions under challenging conditions. Importantly, this performance boost is not achieved at the expense of deployability. With 32.76 M parameters and an inference speed exceeding 75 FPS on high-resolution images, the model strikes a balance between architectural complexity and the real-time processing needs of modern intelligent agriculture.

In summary, FESW-UNet serves as an efficient and reliable automated monitoring tool for sorghum aphids. While the current implementation relies on RGB imaging to establish the foundation for visual pest detection, future work will focus on expanding its adaptability. We plan to integrate heterogeneous multi-source data (e.g., near-infrared and multispectral imagery) to address spectral confusion in mimetic scenarios. Additionally, we aim to optimize the network for ultra-lightweight deployment on drone platforms, thereby broadening the method’s applicability for large-scale, sustainable field management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H. and F.R.; methodology, C.H. and F.R.; software, F.R.; validation, F.R.; formal analysis, C.H.; investigation, F.R.; resources, F.R. and C.H.; data curation, F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R.; writing—review and editing, C.H.; visualization, F.R.; supervision, C.H.; project administration, C.H.; funding acquisition, C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.42471437).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to those people who have helped with this manuscript and to the reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zander, A.; Lofton, J.; Harris, C.; Kezar, S. Grain sorghum production: Influence of planting date, hybrid selection, and insecticide application. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2021, 4, e20162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zheng, T.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Sun, C.; Yang, X. Classification and detection of insects from field images using deep learning for smart pest management: A systematic review. Ecological Informatics 2021, 66, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, D.; Zhou, H. PlantBiCNet: A new paradigm in plant science with bi-directional cascade neural network for detection and counting. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 130, 107704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinathan, T.; Singaraju, D.; Uyyala, S.R. Insect classification and detection in field crops using modern machine learning techniques. Information Processing in Agriculture 2021, 8, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, S.; Zheng, S.; Liu, L. MSR-RCNN: a multi-class crop pest detection network based on a multi-scale super-resolution feature enhancement module. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 810546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, R.; Xie, C.; Yang, P.; Liu, L. Fusing multi-scale context-aware information representation for automatic in-field pest detection and recognition. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 169, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ye, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, H.; Li, X. TasselLFANet: a novel lightweight multi-branch feature aggregation neural network for high-throughput image-based maize tassels detection and counting. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1158940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Dubey, A.K.; Jothi, A. Pest detection using adaptive thresholding. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA), 2017; IEEE; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, W.; Hu, C.; Luo, Y. Image segmentation method for forestry unmanned aerial vehicle pest monitoring based on composite gradient watershed algorithm. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2017, 33, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Huang, T.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X. Application of agricultural insect pest detection and control map based on image processing analysis. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2020, 38, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, R.; Xie, C.; Yang, P.; Wang, F.; Sudirman, S.; Liu, W. PestNet: An end-to-end deep learning approach for large-scale multi-class pest detection and classification. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 45301–45312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiao, L.; Xie, C.; Chen, P.; Du, J.; Li, R. S-RPN: Sampling-balanced region proposal network for small crop pest detection. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 187, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, R.; Xie, C.; Yang, P.; Liu, L. Fusing multi-scale context-aware information representation for automatic in-field pest detection and recognition. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 169, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, T.; Brandão, T.; Ferreira, J.C. Machine learning for detection and prediction of crop diseases and pests: A comprehensive survey. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiyan, Z.; Linpeng, J.; Jun, D. A review of research on convolutional neural networks. J. Comput. Sci 2017, 40, 1229–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chu, H.; Zhang, X.; Rao, Y. A review of deep learning-based YOLO target detection. Journal of Electronics and Information 2022, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Liu, G. An approach on image processing of deep learning based on improved SSD. Symmetry 2021, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Shi, Y.; Gao, Y. Multi-scale faster RCNN detection algorithm for small targets. Journal of computer research and development 2019, 56, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- ZHAO, K.; SHAN, Y.; YUAN, J.; ZHAO, Y. Research on maize pest detection based on instance segmentation. Journal of Henan Agricultural Sciences 2022, 51, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Jian, F.; Jayas, D.S. Detection of stored-grain insects using deep learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 145, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Gupta, M.; Kathait, R.; et al. Deep Learning Based Analysis and Detection of Potato Leaf Disease. NEU Journal for Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things 2023, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ranftl, R.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Koltun, V. Vision transformers for dense prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 12179–12188. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Yu, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X. Multi-scale convolution-capsule network for crop insect pest recognition. Electronics 2022, 11, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Indris, C.; Bramesfeld, G.; Zhang, T.; Li, K.; Chen, X.; Grijalva, I.; McCornack, B.; Flippo, D.; Sharda, A.; et al. A new dataset and comparative study for aphid cluster detection and segmentation in sorghum fields. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, D.; He, S.; Zhang, G.; Luo, M.; Guo, H.; Zhan, J.; Huang, Z. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Li, N.; Weng, C.; Su, D.; Li, M. Simple attention module based speaker verification with iterative noisy label detection. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2022; IEEE; pp. 6722–6726. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Liao, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; He, X.; Wu, X. Haar wavelet downsampling: A simple but effective downsampling module for semantic segmentation. Pattern recognition 2023, 143, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, B.N.; Namboodiri, V.P.; Agneeswaran, V.S. Spectformer: Frequency and attention is what you need in a vision transformer. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2025; IEEE; pp. 9543–9554. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, E.; Morrow, R. The fast Fourier transform. IEEE Spectrum 2009, 4, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y. Gated channel transformation for visual recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 11794–11803. [Google Scholar]

- Long, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, B. PSPNet-SLAM: A semantic SLAM detect dynamic object by pyramid scene parsing network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 214685–214695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xue, C.; Shao, Y.; Chen, K.; Xiong, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, L. Semantic segmentation of litchi branches using DeepLabV3+ model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164546–164555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.S.; Varshney, S.; Srijith, P.; Gupta, S. Continual learning with dependency preserving hypernetworks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 2023; pp. 2339–2348. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, R. Moga: Searching beyond mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2020; IEEE; pp. 4042–4046. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, B.; Ahmed, R.; Hassan, T.; Werghi, N. Sip-segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder network for joint semantic segmentation and extraction of sclera, iris and pupil based on periocular region suppression. arXiv arXiv:2003.00825.

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Dehghan, M.; Zaiane, O.R.; Jagersand, M. U2-Net: Going deeper with nested U-structure for salient object detection. Pattern recognition 2020, 106, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, A.; Anand, V.; Gupta, S.; Al Reshan, M.S.; Alshahrani, H.; Shaikh, A.; Elmagzoub, M. An intelligent LinkNet-34 model with EfficientNetB7 encoder for semantic segmentation of brain tumor. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.j.; Zou, J.m.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, G.z.; Wang, Y. Real-Time Semantic Segmentation of Maritime Navigation Scene Based on Improved Fast-SCNN. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Transportation, 2024; Springer; pp. 346–362. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).