1. Introduction

Serverless computing promises rapid development and deployment of applications and services [

11,

14]. Instead of purchasing and managing backend infrastructure, service providers can focus on developing application logic, while cloud providers handle resource provisioning, service deployment, hardware fault tolerance, and etc. Additionally, serverless platforms offer high availability and automatic scaling, enhancing service robustness. The serverless market is already substantial — nearly

$8 billion — and is projected to exceed

$20 billion by the end of 2026 [

39]. As one CEO said, “Serverless has demonstrated that it is the operational model of the future.” [

19]

Existing serverless platforms largely follow a

disaggregated approach [

25,

27,

33,

43,

51,

53,

55,

61,

63]. For example, consider AWS Lambda, the most popular serverless platform today. To deploy a service, the application developers upload custom executables or scripts to AWS Lambda, which then execute them in virtualized environments upon user invocations [

3]. However, these virtualized environments lack mechanisms to store data persistently. To reliably store application data for the desired functionality, developers must rely on external storage services such as Amazon S3 [

9].

The separation of compute and storage enables independent scaling of each component and works well for certain non-interactive applications. However, service providers quickly encounter challenges when building more complex, data-intensive applications [

8,

30]. Recent surveys have found that many serverless functions run for only a few seconds, are invoked infrequently, and operate on datasets smaller than 10 Mb [

22,

54]. These use cases highlight the limitations of current platforms: serverless execution in its current form suffers from degraded performance under these workloads due to high latency interacting with external storage systems [

35].

In addition, most serverless platforms provide

at least once semantics and lack transactional guarantees. The serverless functions may execute more than once on a single request, and partial results of an ongoing execution may be observed by other function calls. Consequently, serverless platforms often require functions to be idempotent to accommodate these semantics [

2], and they place the burden of concurrency control on the application itself if needed—directly contradicting one of the core tenets of serverless systems: reducing complexity for the application developer.

To address these challenges, we identify six desirable properties for modern serverless platforms, which we abbreviate as

RAISED: Responsiveness, Atomicity, Isolation granularity, Serializable workflows, Elasticity, and Durable storage. Based on these properties, we introduce

LambdaStore: a serverless execution system with an integrated storage engine designed for low-latency cloud applications. In

LambdaStore, serverless functions execute close to their persisted data, reducing storage access cost, while the storage engine provides transactional guarantees for the function executions. Such a co-design aligns with the end-to-end argument [

52]: rather than enforcing consistency and fault tolerance separately at the storage and compute layers, a unified architecture significantly reduces the overhead associated with replication and concurrency control.

The design of

LambdaStore addresses three key challenges: identifying the affinity between serverless functions and application data to enable compute-storage colocation, efficiently supporting transactional workflows, enabling colocation without sacrificing the elasticity of the stateless model. To discover opportunities for colocation,

LambdaStore introduces

LambdaObjects, an object-oriented data model that associates functions with their application data (§

3.1). To support transactional workflows,

LambdaStore embeds a transactional key-value store and encapsulates each workflow within its own transaction (§

4.3). This storage layer is tailored for serverless workloads, minimizing transaction conflict rates. To preserve the scalability and elasticity essential in cloud environments,

LambdaStore leverages two mechanisms:

light replication (§

4.4.2) and

object migration (§

4.4.3). It employs microsharding to efficiently migrate or replicate individual objects, enabling rapid adaptation to changing workloads (§

4.4.1).

LambdaStore outperforms the conventional disaggregated serverless design in both throughput and latency while providing stronger guarantees. We compare it against OpenWhisk [

25], OpenLambda [

46], Faasm [

55], and Apiary [

37] using microbenchmarks to demonstrate its performance benefits. Our experimental results show that, compared with other serverless systems based on WebAssembly,

LambdaStore is able to deliver orders of magnitude higher throughput while maintaining a low end-to-end latency for stateful workloads. We also evaluate the systems with two applications – an online message board and a Twitter-like microblog – to demonstrate its scalability. We observe that

LambdaStore scales almost linearly with the number of nodes. With a cluster of 36 machines, it can process up to 600k transactions per second.

2. Background and Motivation

Serverless platforms allow mutually distrusting applications to share cloud infrastructure through virtualization and dynamic resource assignment. Virtualization isolates individual running serverless function instances (or serverless jobs) from one another, ensuring that jobs fail independently and do not compete for resources. This isolation provides fault resilience, allowing multiple applications to safely colocate on the same hardware. Dynamic resource allocation, in turn, enables the (re-)allocation of resources to serverless jobs at runtime. It improves resource efficiency and supports scalability by adjusting resource allocations based on each application’s current workload.

Serverless systems provide an abstraction that allows developers to build and deploy services without provisioning or managing machines. In this model, applications are implemented as a set of functions, and a cloud provider (e.g., AWS Lambda, Microsoft Azure Functions, Google Cloud Functions) manages their instantiation and execution. Each job can invoke other serverless functions, forming a serverless

workflow. In some system designs, each job performs a small task, and workflows consist of many such jobs [

26]. However, the complexity and runtime of a job can vary depending on the application.

Table 1.

Comparison of LambdaStore to other serverless architectures. We report only cold start time as a measure of responsiveness, since end-to-end latency is highly dependent on application logic.

Table 1.

Comparison of LambdaStore to other serverless architectures. We report only cold start time as a measure of responsiveness, since end-to-end latency is highly dependent on application logic.

| |

Responsiveness (Cold-Start) |

Atomicity |

Isolation Granularity |

Serializable Workflows |

Elasticity |

Durable Storage |

|

OpenWhisk [25] |

>100ms |

No |

Job |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

OpenLambda [46] |

<1ms (WASM)>10ms (SOCK) |

No |

Job |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Faasm [55] |

<1ms |

No |

Job |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Apiary [37] |

<1ms |

No |

Application |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

AWS Lambda [53] |

>10ms |

No |

Job |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Google CloudFunctions [27] |

>100ms |

No |

Job |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

AzureFunctions [43] |

>100ms |

No |

Job |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

LambdaStore(This paper)

|

<1ms |

Yes |

Job |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

2.1. RAISED

Our goal is to design a cloud computing infrastructure suitable for stateful applications. After evaluating existing platforms, we identified six desirable properties for modern cloud computing systems, which we abbreviate as RAISED:

Responsiveness: Serverless applications should be able to respond to user requests quickly, even during cold starts.

Atomicity: The cloud platform should guarantee exactly once execution semantics to simplify application logic.

Isolation Granularity: The platform should offer fine-grained isolation to ensure that jobs fail independently.

Serializable Workflows: For applications requiring strong consistency, the platform should ensure that workflows are serializable and that applications always observe a consistent state.

Elasticity: The platform should dynamically adjust resource allocations based on current workloads.

Durable Storage: The platform must be able to reliably persist application data.

A conventional stateful serverless system architecture typically consists of three components: a coordination layer, a compute layer, and a storage layer. We describe this architecture using OpenWhisk [

25] as a representative example OpenWhisk relies on Apache Kafka [

24] to track outstanding jobs, which are then delegated to a compute layer (e.g., Kubernetes [

49]). Serverless applications interact with a dedicated storage layer, such as a DBMS or key-value store, to persist state across function invocations.

This disaggregated compute-storage architecture enables high elasticity, as scaling a stateless compute layer is straightforward. However, it also incurs frequent data transmissions, leading to high latencies and reduced responsiveness. For example, in a simple read-modify-write workload, a job must first fetch data from the remote storage system, perform the update, and then write the result back. While the update itself may take only a few microseconds, the data fetch and store operations dominate latency. This problem is worsened during cold starts, which require establishing new TCP connections between the compute and storage layers, and by the high software overhead imposed by the storage system on every data access.

Furthermore, because most serverless platforms do not guarantee exactly once execution semantics, they cannot provide transactional guarantees at the workflow level — even if the storage layer supports transactions. This is due to the lack of coordination: serverless functions must explicitly commit transactions. If a transaction is committed but the workflow fails and is retried, the ACID properties can be violated. As a result, conventional cloud computing platforms, including OpenWhisk, OpenLambda [

46], AWS Lambda [

53], Google Cloud Functions [

27], and Azure Functions [

43], suffer from these limitations.

Some research efforts [

4,

18,

33,

36,

51,

55,

57,

61,

62,

63] seek to reduce state access latency by caching persistent state or storing intermediate state locally. Jobs within a workflow that share state can benefit significantly from this approach, as the platform can improve data locality by colocating them on the same machine, avoiding repeated data transmission over the network. Faasm, in particular, further improves responsiveness by adopting

software-fault isolation (SFI) via

WebAssembly to reduce cold-start latency. However, this compute-centric design still relies on remote storage for data persistence. Caching does not improve cold-start performance, since the state is not yet in cache, and it introduces complexity in maintaining consistency across the storage layer.

Other research efforts [

37,

45,

58,

64] propose shipping serverless jobs (or subunits of them) to the storage layer to enable colocation. Apiary, for example, leverages the user defined functions (UDFs) in database systems to provide ACID transactions. This approach not only reduces the end-to-end latency, improving responsiveness, but also ensures serializability and atomicity. Nonetheless, a naïve colocation design will restrict the elasticity of serverless systems: forcing jobs to run near the data constrains the amount of compute resources they can utilize, as the resources available near the data are limited by the capacity of the physical machines storing that data. Apiary’s approach additionally introduces problems with fault isolation, since stored procedures are not designed to run untrusted code from users.

In summary, while existing serverless platforms and research prototypes have made significant strides in improving elasticity, responsiveness, and transactional support, they often face trade-offs between colocation and scalability, or between performance and durability. These limitations highlight the need for a new system architecture that unifies compute and storage without sacrificing the core benefits of serverless computing. In this work, we present LambdaStore, a serverless execution platform designed to meet the RAISED properties by tightly integrating compute and storage, enabling transactional, low-latency, and scalable execution for stateful cloud applications.

3. The LambdaObjects Abstraction

LambdaStore is a cloud computing system built on a compute-storage co-design. It organizes both data and execution around stateful objects, which we refer to as LambdaObjects. This section introduces the LambdaObjects abstraction and illustrates its effectiveness through a concrete example.

3.1. Data Model

3.1.1. Objects

Applications in

LambdaStore are defined through

Object Types, which specify both the executable code (

functions) and the data entries (

fields) that each object contains.

Objects can then be instantiated from these types, similar to the class-object relationship in object-oriented programming — a paradigm familiar to many developers. By encapsulating both logic and data within objects,

LambdaStore provides an intuitive way to decompose applications into small, independent components, akin to the structure of microservices [

12]. Moreover,

LambdaStore leverages this object abstraction to determine data placement and to colocate function execution with the corresponding data. The object model is designed to be highly flexible, supporting multiple programming languages, variable object sizes, and application-specific data types.

3.1.2. Applications

Each object belongs to an application. The application developer is billed for both the storage of the application’s data and the execution of its functions. Developers define which object functions are part of the application’s public API and which are restricted to internal use. Currently, objects can invoke functions only within the same application. We reserve sharing data and code across application boundaries and more fine-grained access control for future work.

3.1.3. Object Entries

Entries form the smallest unit of data in LambdaStore and are stored as (part of) a field within a specific object. Data fields then define how entries are accessed, stored, and indexed for lookup. LambdaStore currently supports three field types: maps, multi-maps, and cells (unstructured data). Other data types can be implemented in application code. For example, a set can be built on top of the map primitive.

Each entry is a key-value pair that is stored and replicated by LambdaStore and is associated with a specific data field of an object. For instance, an entry might represent a single item in an object’s map or the full content of a cell. The content and semantics of each entry are application-specific and opaque to LambdaStore. Functions interact with entries through a minimal API that supports reading, writing, and basic range queries. Application code is responsible for (de-)serialization of data and to provide more complex data operations (e.g., increment or append).

3.2. Execution Model

3.2.1. Function Calls

Application logic in LambdaStore executes in the form of function calls (or jobs). A job represents the invocation of a specific function. As in conventional serverless systems, more complex application logic can be constructed by composing multiple jobs into a workflow. The structure of the job graph within a workflow is not predefined; instead, it is generated dynamically as functions execute.

Functions in LambdaStore come in several variants, similar to those in object-oriented programming. Constructors are used to create and initialize new objects. Methods operate on existing objects and can access or modify their fields. Static functions are not associated with any specific object and hence do not have direct access to object data.

In addition, LambdaStore provides a mechanism for operations that involve many objects: map calls. For example, consider the task of finding the maximum age among all clients in an application, where each client is represented by a dedicated object. Executing a separate function on each object individually would be highly inefficient. Instead, a map call takes a set of objects O and a function f, and executes at most one instance of f per shard. Each invocation of f then iterates over the subset of O that is located on that shard. This mechanism enables efficient batch processing without incurring additional data movement. The results of the map call (if any) are aggregated and returned to the caller.

Function calls have direct access only to the data of the object(s) they are associated with. To access or modify data in other objects, functions must either invoke constructors or methods on those objects or use map calls. This pattern minimizes data movement, which we elaborate on in

Section 4.4.1.

Functions in LambdaStore are exposed to a minimal API upon which more complex application logic can be built. This API allows functions to read and write object entries, invoke other functions, manage user sessions, retrieve function arguments, set return values, obtain the current time, and generate randomness. Similar to system calls in an operating system, which only provide low-level functionality, higher-level abstractions are then implemented in user space (or in our context, within the serverless functions).

Functions execute until they either complete successfully or are terminated by the runtime. Termination can occur due to fatal errors (e.g., stack overflows), violations of security policies (e.g., attempting to access data outside the application’s scope), or exceeding the maximum allowed execution time.

3.2.2. Transactions

LambdaStore guarantees strict serializability across the entire workflow. A workflow can be represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) — more specifically, as a directed rooted tree — of function calls. In this graph, each vertex corresponds to a job, and each edge represents a function call that spawns another job. Workflows are initiated by clients invoking a public function, which forms the root of the DAG. As functions call other functions, the DAG is dynamically extended at runtime. These execution graphs are not predefined by the application developer but are constructed automatically during execution. Developers can inspect a workflow’s structure by examining its execution trace.

Currently, individual function calls in LambdaStore execute sequentially, but workflows can execute multiple jobs concurrently. LambdaStore allows a function to issue multiple function calls simultaneously and wait for all of them to complete. For example, in a social network application, a function that creates a user’s post might invoke separate functions for each follower to update their respective timelines. While the post creation itself executes sequentially, the timeline updates can proceed in parallel.

Each workflow in LambdaObjects is contained within a single LambdaStore transaction. Throughout this paper, we use the terms workflow and transaction interchangeably when referring to LambdaStore.

3.3. Example Application

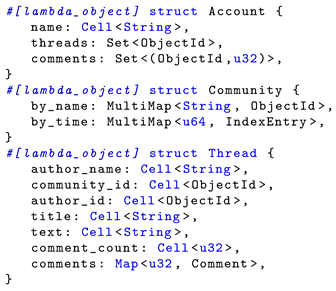

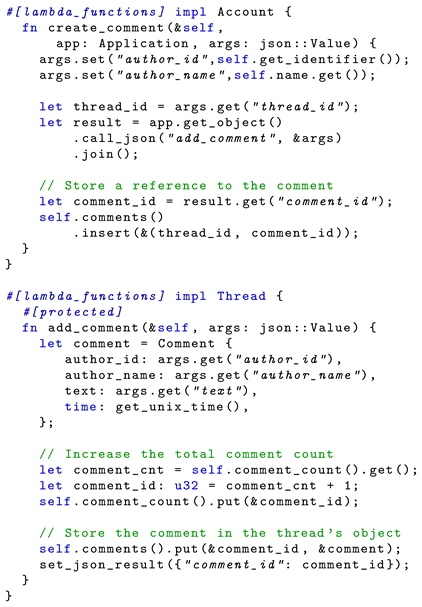

LambdaObjects support arbitrary applications. To demonstrate its flexibility, we present an example application: CloudForum, an online discussion board similar to Reddit. This section outlines part of its implementation in Rust, with some simplifications made for clarity and space constraints.

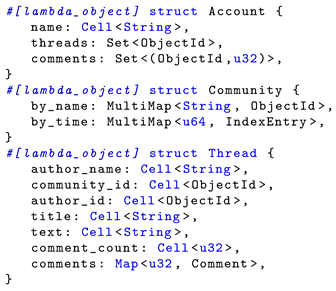

Listing 1 shows how object types are declared within an application. In this example, we outline three types. Accounts represent users of the online forum and contain references to all threads and comments they have created. Threads store the initial post by the thread creator, along with a sequence of comments. Comments are stored using a custom structure called Comment, which is not an object type itself but defines how data within the comments field is structured. Each comment can be identified through the thread ID and its index within the thread. Finally, threads are indexed using the Community type.

| Listing 1: Object types for an online forum application. |

|

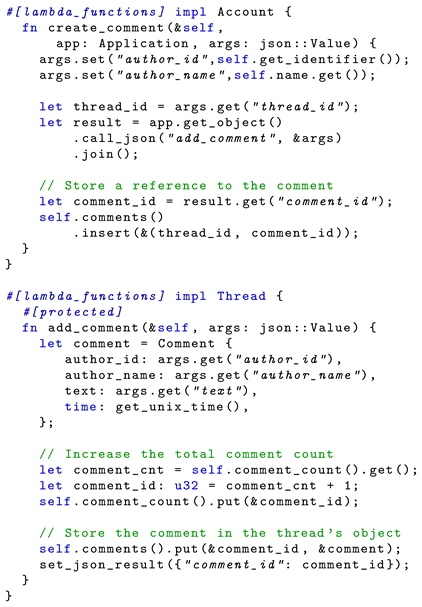

Listing 2 illustrates the workflow for adding a new comment to an existing thread. The implementation uses LambdaStore’s Rust bindings, which abstract away much of the boilerplate, such as data serialization. Users initiate the workflow by invoking the create_thread method on an object of type Account. Arguments, such as the content of the comments, are passed in a JSON document.

| Listing 2: Implementation of CLOUDFORUM’s comment functionality. Low-level API calls are abstracted behind a higher-level interface. Access control and error handling logic are omitted for brevity. |

|

The function first authenticates the user (not shown) and looks up the user’s identifier and name. It then calls the add_comment method on the specific thread where the comment should be added. This method executes in a separate, dedicated job. By default, invoked function calls run in the background unless the parent job explicitly calls join, as shown in the example. This API enables concurrency similar to async/await pattern found in many programming languages: multiple child jobs can be spawned and waited on simultaneously.

The add_comment method then stores the comment as part of the Thread object. It attaches a timestamp to the comment using the get_unix_time host call. Finally, it returns the comment’s identifier, which the Account object stores in its comments field.

4. LambdaStore

This section presents the design of LambdaStore in detail. We begin by outlining the overall system architecture. Next, we discuss the virtualization technique employed by LambdaStore. We then describe how LambdaStore efficiently provides transactional guarantees for workflows and how it enables compute-storage colocation while preserving elasticity. Finally, we describe fault tolerance and recovery mechanisms.

4.1. System Architecture

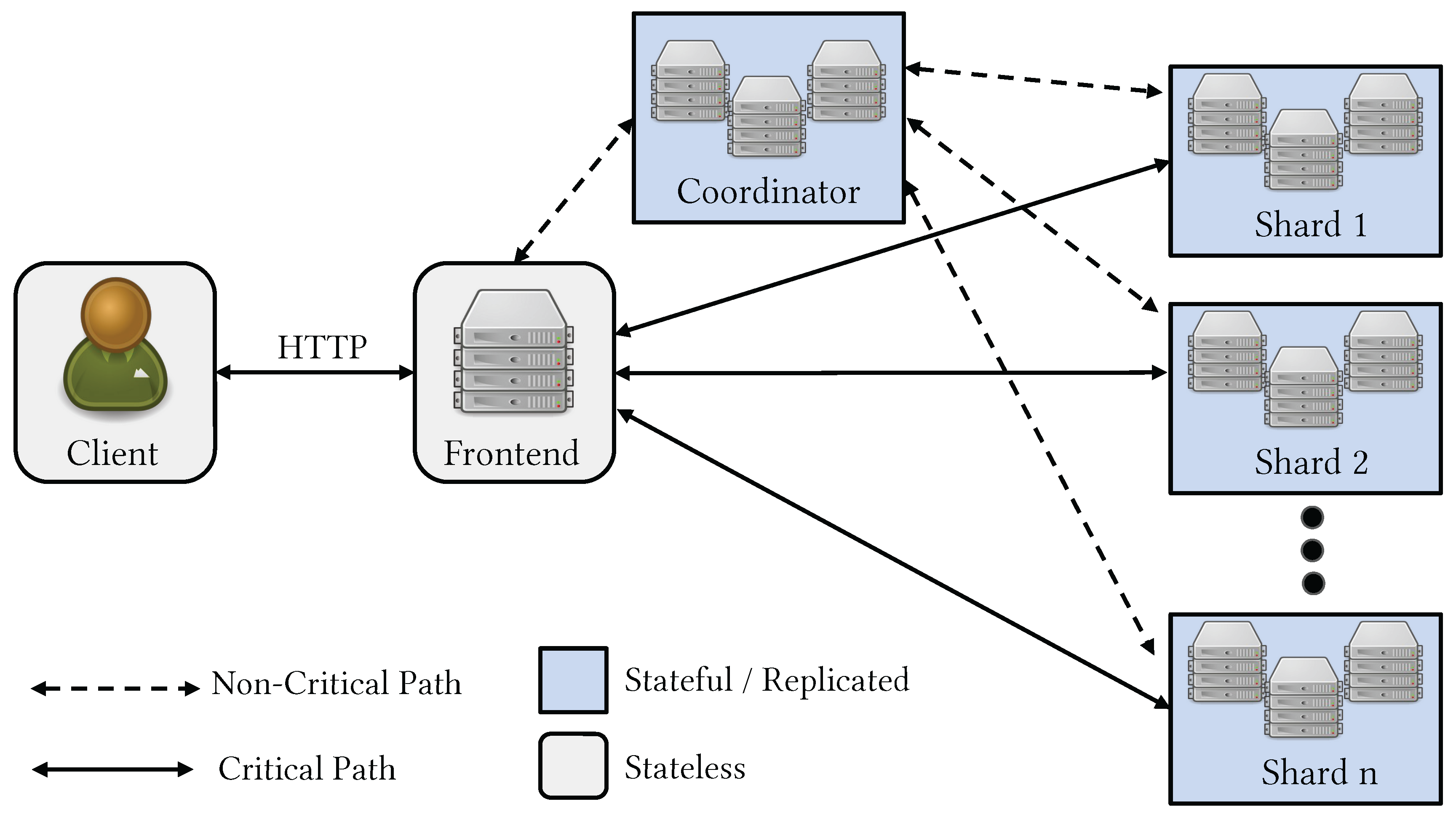

LambdaStore consists of four types of participants: clients, frontends, worker nodes, and coordinating nodes.

Figure 1 sketches how these components interact within the system.

4.1.1. Worker Nodes and Replica Sets

Worker nodes execute serverless jobs and store LambdaObjects. They are organized into replica sets of nodes. Application data are sharded, and each shard is assigned to a replica set. Nodes within a replica set run replication protocols to ensure data consistency and durability.

Requests for LambdaObjects methods are first sent to the primary node of the replica set that stores the associated object. The primary determines where the method should be executed. Under light workloads, it is most efficient to execute the job directly on the primary. Under heavy workloads, however, the primary can delegate the job to other nodes in the replica set to avoid becoming a bottleneck.

Within each replica set,

LambdaStore uses chain replication [

28] to replicate data across nodes. As the name suggests, nodes in the set are arranged in a chain, with the head serving as the

primary and the remaining nodes acting as

secondary replicas. During state changes, the primary communicates the update to only one secondary replica, which then propagates it down the chain. This design significantly reduces the load on the primary, enabling high scalability and elasticity even under skewed workloads.

4.1.2. The Coordinating Service

The coordinating service (or coordinator) is responsible for maintaining all metadata. It tracks all participants in the cluster, the configuration of individual shards, and the placement of objects within those shards. When worker nodes, frontends, or clients join the network, they first connect to the coordinating service, which informs them about other worker nodes in the system and the current object placements.

For reliability, the coordinating service should ideally use a distributed metadata management system such as ZooKeeper [

31]. In our prototype, however, the coordinator is not replicated for simplicity. We argue that this does not significantly impact system performance, as the coordinating service is not involved in most requests. Transactions only reach the coordinator if they create new objects or when there is an ongoing reconfiguration of the cluster, which only occurs when the system performs a load balancing decision (

Section 4.4.1) or during failures (

Section 4.5).

4.1.3. Clients and Frontends

To avoid accessing the coordinator on every request, clients maintain local caches of system configuration and object placements. However, a large number of short-lived clients can easily overwhelm the coordinating service. To mitigate this issue, LambdaStore introduces Frontends, which maintain up-to-date caches of the cluster configuration. Clients send their requests to a Frontend, which then redirects the request to the appropriate primary worker node based on its cached view.

4.2. Virtualization Layer

LambdaStore enables the execution of untrusted computation through the use of WebAssembly (or

WASM) [

29]. We chose WebAssembly as the virtualization mechanism due to its significantly lower overhead compared to alternatives such as virtual machines (VMs) or containers. Once an application developer compiles their code into WebAssembly, it is registered with the coordinator. The coordinator then compiles the WebAssembly instructions to machine code, injects additional safeguards to protect against misbehaving programs, and distributes the resulting code to all storage nodes.

Upon invocation, nodes directly embed the generated code into their address space. To start a job, a node allocates memory using mmap and performs a context switch by saving register contents and setting the program counter to a location within the function’s code. The function interacts with the host environment via a predefined set of API calls, each of which triggers a context switch back to the storage layer, analogous to how system calls transition from user space to kernel space.

LambdaStore protects against non-terminating functions using periodic timer interrupts. When an interrupt occurs, a trap handler checks whether the current function has exceeded its maximum execution time and aborts it if necessary. Tracking function execution time is also essential for implementing an accurate billing model in a cloud environment.

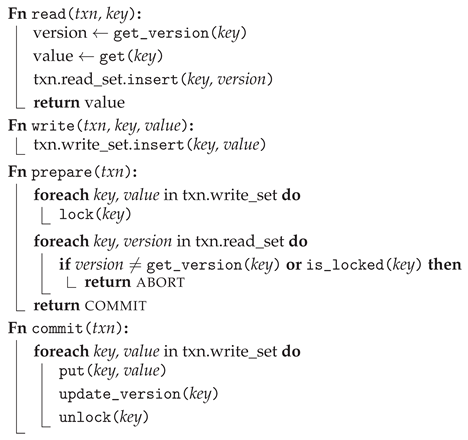

4.3. Serverless Transactions

The storage layer in LambdaStore provides a transactional interface. LambdaStore enforces atomicity and strict serializability by encapsulating all data accesses within a workflow into a single transaction. The transaction is committed when the workflow completes. If the commit fails, LambdaStore can re-execute the workflow to ensure that its effects are externalized exactly once. This guarantee holds under the assumption that workflows do not produce side effects on external services outside of LambdaStore’s control. Supporting exactly-once semantics for functions that interact with external services remains an open challenge and is left to future work.

Providing transactional guarantees efficiently under serverless workloads is challenging. Since developers can define arbitrary application logic, workflows may vary significantly in duration and read-write patterns, ranging from short-running to long-running executions. Running such workflows concurrently can result in high conflict rates and, in some cases, starvation. Additionally, the elastic nature of serverless platforms allows a large number of workflows to execute simultaneously under heavy workloads, further exacerbating contention.

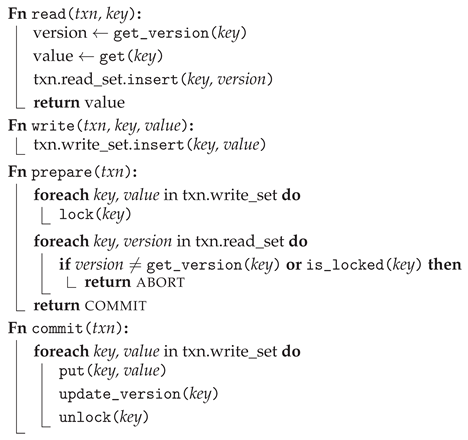

LambdaStore addresses these challenges by dynamically adjusting lock granularity through

entry sets and by employing a variant of Silo’s optimistic concurrency control protocol [

59] with two phase commit (2PC).

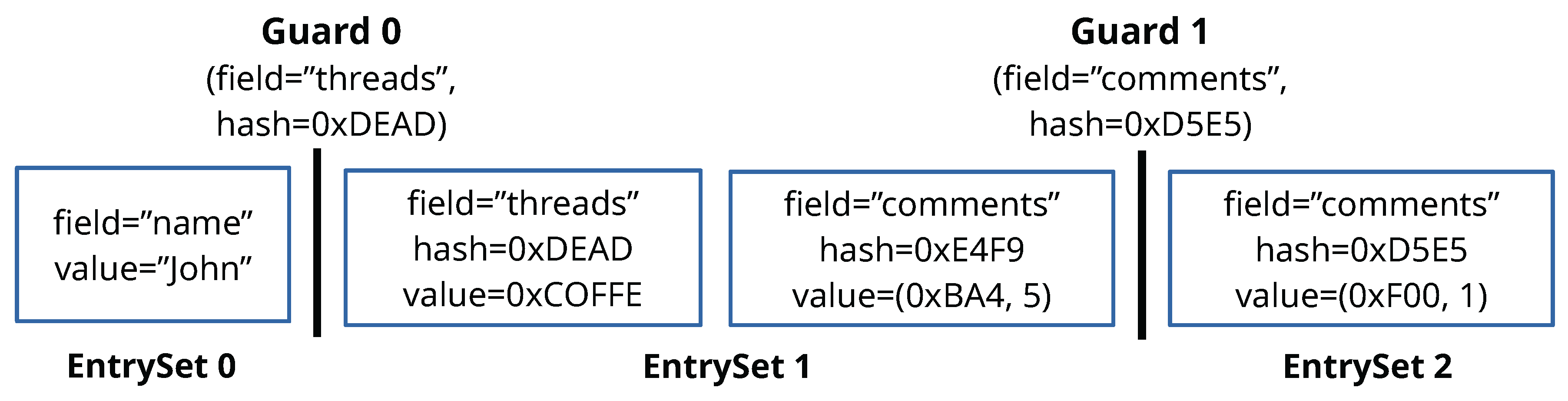

4.3.1. Entry Sets

LambdaStore tracks metadata (e.g., locks and version numbers) for each object to support concurrency control. A naïve approach might maintain a single set of metadata per object, which can be too coarse-grained for large objects, or one set per entry, which introduces excessive bookkeeping overhead. Instead,

LambdaStore uses

entry set as the unit of locking and version control. Each object defines a series of

guards that determine the boundaries between entry sets.

Figure 2 illustrates an example of such a partitioning. Entry sets allow

LambdaStore to reduce transaction conflicts by dynamically adjusting the lock granularity. Rather than locking entire objects, transactions only acquire locks on the entry sets they access. In the example shown in

Figure 2, one transaction can update the account name while another concurrently creates new threads without conflict.

In

LambdaStore, objects initially consists of a single entry set. With some probability, a write to a key will insert a new guard at that key’s position, effectively splitting the entry set in half. As a result, objects that are written to more frequently are likely to accumulate more guards and be partitioned into more entry sets. The intuition behind this design is that only write-heavy workloads benefit from finer lock granularity. A similar approach has proven effective in the context of Log-Structured Merge Trees [

48]. Because entry sets can only be split during writes, splitting occurs exclusively during transaction commits, when the entry set is already write-locked and inaccessible to other transactions. After the split, the resulting entry sets are assigned version numbers higher than that of the original set. This mechanism ensures that the concurrency control protocol detects and handles the change appropriately. Consequently, entry set splitting does not interfere with function execution or violate system consistency.

4.3.2. Concurrency Control

Because serverless workflows can run for arbitrary durations, using pessimistic locking may lead to starvation, where a single long-running workflow blocks all other concurrent ones. To avoid this problem,

LambdaStore uses a variant of Silo’s optimistic concurrency control protocol [

59] to enforce ACID properties within each shard. During the execution phase, instead of atomically reading both the value and its version number,

LambdaStore leverages the atomic interface of its key-value storage backend to allow transactions to read a slightly stale version number. Specifically, during reads, each transaction first atomically reads the version number of the corresponding entry set, then queries the storage backend for the value. During the commit phase, the transaction must write each updated value back and then atomically update its version number. This design enables reads to proceed without acquiring locks during the execution and prepare phases. We provide a correctness proof in

Appendix A. The core intuition is that if a transaction reads a mismatched version and value during execution, then either (1) the version number it reads during the prepare phase will differ from the one read during execution, or (2) another concurrent transaction will be updating the entry set, which will then be write-locked. In both cases, the transaction will abort, ensuring serializability. Within each replica set, secondary nodes can execute jobs and read from their local storage during the execution phase. However, for each workflow, the secondary must send its read set and write set to the primary node, which is responsible for handling the prepare and commit phases.

|

Algorithm 1: The Transaction Protocol of LambdaStore

|

|

LambdaStore supports cross-shard transactions by coordinating its concurrency control protocol with two-phase commit (2PC). The worker node that initiates the workflow acts as the transaction manager and is responsible for managing the 2PC process. When a workflow begins, it is associated with a transaction. Jobs spawned by other jobs inherit the transaction context of their caller. Upon completion, each job returns its output to the calling job, along with metadata about the transaction including the identifiers of any additional worker nodes involved and whether any new objects were created. This information is propagated recursively until the initial job (the root of the workflow’s DAG) completes. At that point, the transaction manager begins the 2PC protocol by signaling all involved nodes to enter the prepare phase and report their results. If all nodes agree to commit, the transaction manager then sends a final signal instructing all nodes to commit the transaction.

4.4. Elasticity Storage Service

To colocate compute with storage while preserving the elasticity of serverless platforms, the storage layer must be able to adapt to changing workloads. LambdaStore achieves elasticity through two mechanisms: migration and light-replication. To minimize the overhead associated with both, LambdaStore employs microsharding, allowing the system to respond quickly to workload fluctuations.

4.4.1. Microsharding

LambdaStore treats objects as

microshards [

10], ensuring that each object and all of its associated data are mapped to a single shard. This fine-grained approach enables

LambdaStore to quickly respond to workload changes by migrating or creating lightweight replicas of individual objects. While the exact placement policy is beyond the scope of this paper,

LambdaStore generally aims to map objects belonging to the same application to as few replica sets as possible in order to maximize data locality.

The coordinator manages microshard assignments by maintaining the mapping from nodes to shards and from objects to shards. Other participants fetch object locations from the coordinator as needed and cache them locally. Node assignments within shards are modified only during failures or when the overall cluster size changes. The coordinator maintains a persistent TCP connection with each node and interprets connection termination as a node failure. Upon detecting a failure, it reconfigures the affected replica set by promoting the next node in the chain to primary and appending a new secondary node to the end of the chain. In contrast to node assignments, the object-to-shard mapping is much larger and changes more frequently, such as when new objects are created or workloads shift. This mapping is sharded and distributed across multiple physical machines to ensure scalability and availability.

4.4.2. Light Replication

When nodes in a shard experience high load due to a hot object, LambdaStore can temperarily create light replicas of the object on other worker nodes. These light replicas do not participate in the replication protocol. Instead, during updates, the primary node pushes only the updated version number to the light replicas. The light replica lazily fetches the most recent data as needed during job execution. Like secondary nodes, When a workflow completes, the light replica sends the read set and write set associated with the workflow to the primary for finalization to ensure serializability across all participating nodes.

Light replication is especially effective for compute- or read-heavy workloads. Since reads can be processed in parallel, adding light replicas increases computational capacity without raising conflict rates. However, for write-heavy workloads, light replicas offer little benefit, as they can lead to a high number of conflicting transactions running concurrently, ultimately wasting compute resources. For this reason, LambdaStore currently only creates light replicas for objects that are not write-intensive.

4.4.3. Object Migration

Compare to light replication, object migration is more heavyweight as it involves transferring ownership of an object to a different shard. During migration, certain operations such as writes cannot be processed, leading to temporary unavailability. Despite this cost, object migration is essential for effective load balancing, as it allows hot objects to be distributed across multiple shards.

Object migration is managed by the coordinating service. It begins by identifying which microshard needs to be migrated. The coordinator then instructs the primary node currently storing the microshard to initiate the migration. During this process, the object is read-locked, and its data is transferred to the target node. While migration is in progress, read requests can still be served for the object. Once the new node has received all the data, the coordinator updates the microshard’s location. At that point, the original node deletes its local copy and begins rejecting any further requests involving the migrated object.

4.5. Fault Tolerance

LambdaStore can tolerate crash failures of individual nodes. We define a

failure as a node crashing, losing power, or becoming disconnected from the network. It is important to note that while the platform tolerates crash failures in the system architecture, it also supports arbitrary (or Byzantine [

38]) failures during function execution through its virtualization mechanism, as discussed in

Section 4.2.

Transaction execution in LambdaStore tolerates failures of any node, including the client or frontend that initiated the transaction. Since clients and frontends do not participate in state storage or workflow execution after submitting a request, their failure is non-critical. They can simply re-issue the request upon restart without impacting the correctness or progress of the transaction.

We generally refer to a replica set failure when any of its nodes fails. Each replica set in LambdaStore has nodes, allowing the system to tolerate up to f node failures without data loss. When a node fails, the affected replica set undergoes reconfiguration by restarting or replacing the failed node. The coordinator then notifies all other replica sets of the updated configuration.

4.5.1. Replica Failures

Failures of secondary replicas can be handled by the primary, as it is always responsible for processing transaction prepare and commit phases first. Once the primary is informed of a reconfiguration, it will re-issue any delegated transactions or jobs that were affected by the failure.

When the primary fails, a new primary is selected from the remaining secondary replicas by the coordinator. This choice allows the new primary to take over immediately, without requiring a complex recovery protocol. A new replica is then added to the set and synchronizes its state from the existing nodes. If necessary, the new primary reissues pending commit requests. While the state of in-progress transactions may be lost, atomicity is not violated, as incomplete transactions will not be committed and can be safely retried.

Since light replicas do not participate in the replication protocol, they act merely as a cache for the microshards and do not require explicit recovery. The coordinator can create additional light replicas as needed, and any jobs that were running on a failed light replica can be retried on other nodes within the shard.

4.5.2. Transaction Manager Failures

For multi-shard transactions, the transaction manager must consolidate state across all participating nodes. Some nodes may have already prepared the transaction and are waiting to finalize it to release their locks properly, while others may have already finalized the transaction. To uphold atomicity, it is essential to ensure that the transaction is either committed or aborted consistently across all nodes.

After recovery, all nodes notify the new transaction manager about any prepared transactions that originated from it. If the new manager has previously logged a commit for a transaction, it instructs the involved node(s) to proceed with the commit. If no commit was logged, the transaction either was aborted or had not yet completed its prepare phase, in which case it can be safely aborted without violating correctness.

4.5.3. Transaction Participant Failures

When a replica set fails, information about in-progress transactions, including those involving remote shards, may be lost. For transactions that are still in the execution phase, their jobs will simply be re-issued. Similarly, for transactions that were in the prepare phase at the time of failure, the prepare requests will be re-issued as well.

Transactions that have already been prepared or partially finalized must be finalized consistently across all participants. To achieve this, the new primary first checks for any in-progress transactions and then queries each transaction’s manager to determine whether it should be committed or aborted In the case of a commit, the new primary will always have access to the transaction’s write set, as it would have been replicated during the prepare phase. At this point, it is guaranteed that the prepare phase succeeded at all participants as otherwise, the transaction would not have advanced to the commit phase.

4.5.4. Coordinator Failures

In our current prototype, coordinators are not replicated and therefore cannot recover from failures. A production-ready version of LambdaStore would use a distributed metadata management service, such as ZooKeeper, to store object and node mappings. In that case, we could rely on the fault tolerance of the underlying metadata service to support recovery. We leave this integration to future work.

5. Evaluation

We evaluate

LambdaStore using both microbenchmarks and more realistic application workloads. The system is implemented in 33k lines of Rust code and builds on top of Tokio [

17], a framework for asynchronous execution, and Wasmtime [

5], a WebAssembly runtime. Our evaluation answers the following questions:

What overheads are introduced by LambdaStore’s compute-storage colocated design?

How much performance benefit does compute-storage colocation provide?

Is LambdaStore’s transaction interface efficient? How does entry set granularity impact performance?

How scalable and elastic are workflows deployed in LambdaStore?

Can LambdaStore tolerate failures in application code?

What benefit does LambdaStore provide for realistic applications?

5.1. Experimental Setup

We compare

LambdaStore with OpenLambda, OpenWhisk, Apiary, and Faasm. Like most existing serverless systems, OpenWhisk relies on containers for isolation. Although containers are more lightweight than traditional virtual machines, they still incur significant overhead. Faasm combines containers and WebAssembly to reduce this overhead. OpenLambda uses SOCK runtime [

46], a container-based isolation technique, but it also supports a more efficient WebAssembly runtime [

1]. We include both configurations in our evaluation. Finally, Apiary executes serverless functions as stored procedures in PostgreSQL or VoltDB. Unlike the other platforms, Apiary does not isolate job executions.

All benchmarks were execute on Cloudlab [

21] with a cluster of

c220g5 machines. Each machine is equipped with two Intel Xeon Silver 4114 CPUs (each having ten physical cores and Hyper-Threading), 200GB of DDR-4 memory, and 10Gbit NICs.

In our evaluation setup, OpenLambda and OpenWhisk do not perform any replication of client requests or concurrency control. Most other serverless systems contain basic fault-tolerance mechanisms (as outlined in

Section 2) that incur additional overheads. For persisted storage, Faasm uses MinIO [

44], a datastore with an API similar to S3. Apiary uses PostgreSQL. We use

LambdaStore as a storage backend for all other systems.

In the OpenWhisk setup, each compute machine runs a standalone OpenWhisk instance which encapsulates all core components: a

controller that accepts user requests, an

invoker that launches lambda instances, Kafka for streaming requests from the controller to the invoker, and CouchDB for storing the results of each lambda invocation. Each client machine runs a lightweight frontend that distributes requests evenly across the OpenWhisk instances for load balancing. We note that this setup deviates from the traditional OpenWhisk deployment model, in which a centralized controller node manages a set of invoker nodes. However, the performance observed in our configuration aligns with results reported in other studies [

37].

For Apiary, we instantiate a single worker process on one of the storage nodes. This process simply forwards function invocations to PostgreSQL. Additionally, we deploy an HTTP frontend on each client machine. These frontends receive client requests and communicate with the worker process using Apiary’s proprietary protocol. Data replication is configured by assigning two backup nodes for each PostgreSQL database.

5.2. Microbenchmarks

5.2.1. Virtualization and Scheduling Overheads

We first evaluate the overheads introduced by

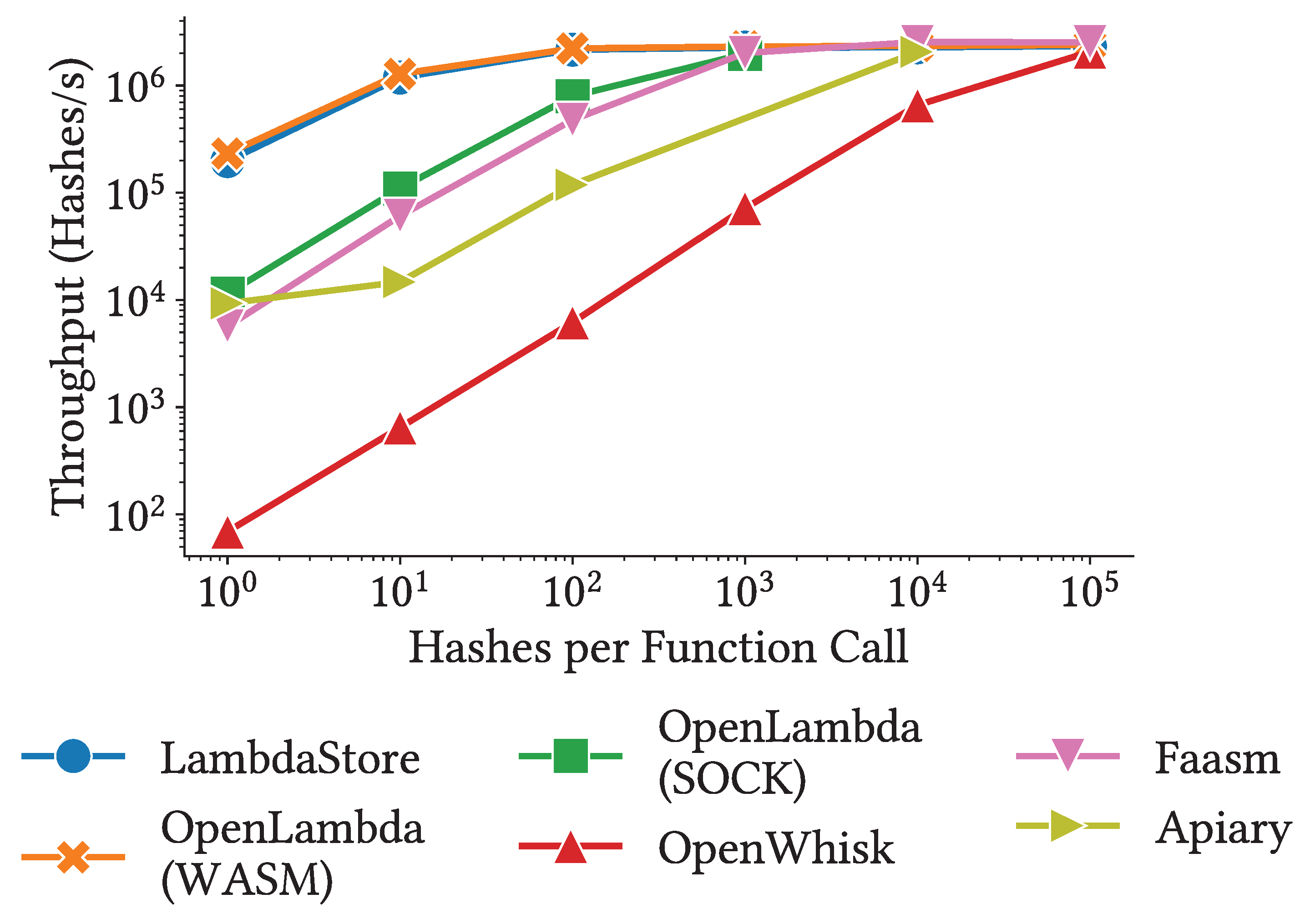

LambdaStore using a benchmark application that computes a series of SHA-512 hashes over 1KB input data. To simulate compute-only, longer-running functions, we gradually increase the number of hashes computed per function call. In this experiment, a single machine is used to execute all functions.

Figure 3 presents our results. Since virtualization and coordination overheads are largely independent of job duration, their relative impact diminishes for longer-running jobs. Once this overhead is sufficiently amortized, all serverless systems achieve similar overall throughput ( 100k hashes per second). Note that all reported numbers reflect warm starts, as the same function is invoked repeatedly.

We observe that serverless systems using WebAssembly for isolation (OpenLambda (WASM) and LambdaStore) incur significantly lower overhead than systems with containerized runtimes(OpenWhisk, OpenLambda (SOCK), and Faasm). Notably, at one hash per function call, LambdaStore achieves the throughput of OpenWhisk. Apiary’s approach, which relies on stored procedures, also introduces higher overhead compared to more optimized container-based approaches like SOCK and Faasm’s containerized WebAssembly runtime. OpenLambda (WASM) initially outperforms LambdaStore slightly, because LambdaStore performs additional coordination checks to determine whether the function will access the storage layer. This check enables more informed scheduling decisions, ultimately reducing data transmission and lowering transaction conflict rates for stateful workflows.

5.2.2. Throughput and Latency of Stateful Workloads

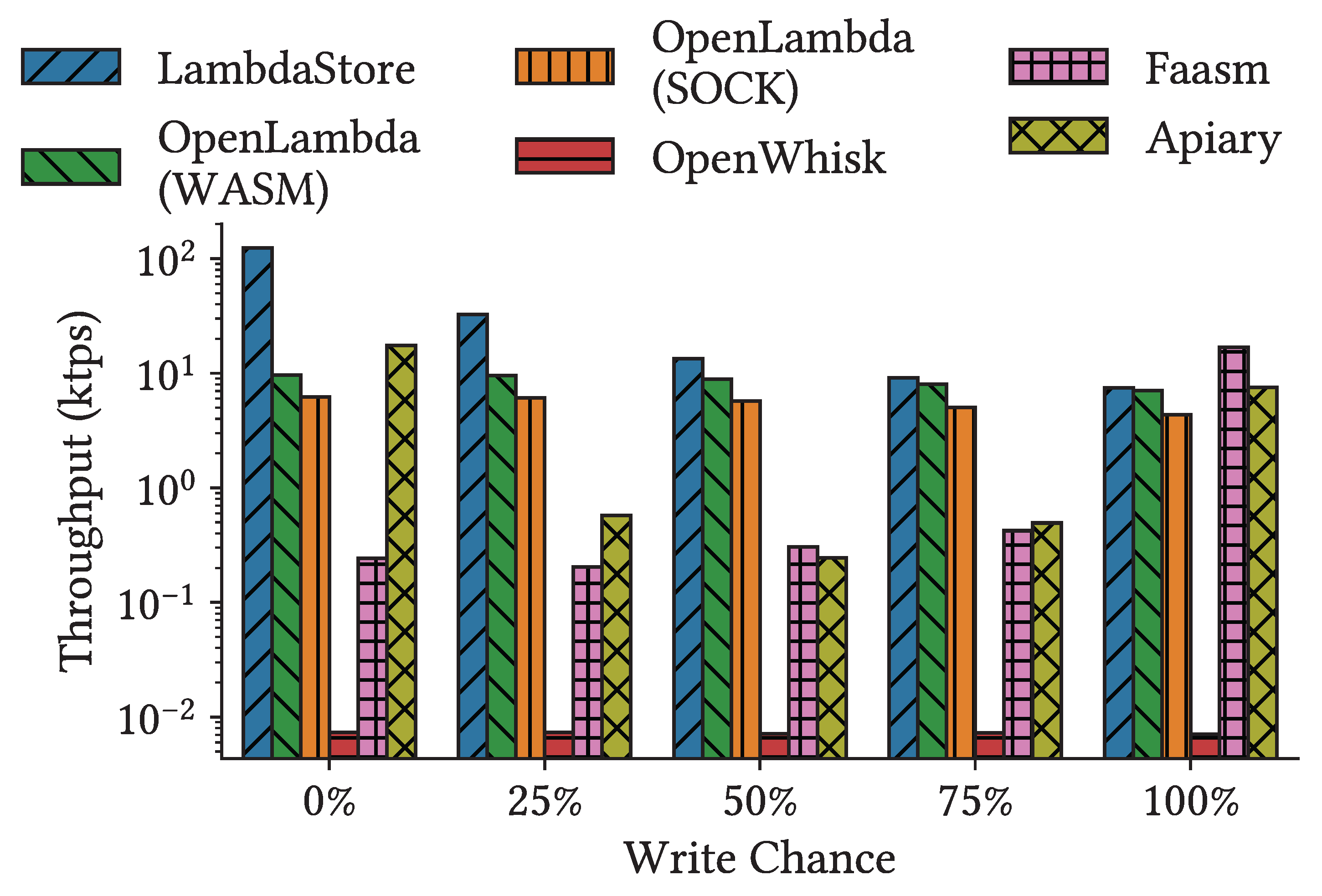

We evaluate LambdaStore using a series of microbenchmarks with varying read-write workloads to quantify the benefit performance benefits of compute-storage colocation. In this setup, we preload the storage system with 10K objects, each containing 100 entries of 1KB in size, resulting in a total of 1M entries at the beginning of the experiment.

We ran the experiment using a set of three nodes to execute serverless functions. For systems without a built-in storage layer (OpenLambda and OpenWhisk), we deployed three additional nodes to form a storage shard. For Faasm, we set up a Kubernetes cluster with six machines to host workers, planners, and the storage backend. During initial testing, we observed significantly lower performance for object and entry creation compared to updates. To keep experiment startup times manageable, we limited the workload to 100 objects. We varied the number of clients and recorded both throughput and latency distribution for each configuration.

Figure 4 shows the highest throughput achieve under each workload with different read-write patterns. For

LambdaStore, OpenLambda, and OpenWhisk, the throughput decreases as the proportion of writes increases, primarily the cost of replicating data across storage nodes. Faasm, in contrast, shows increasing throughput with more writes and outperforms all other systems under write-only workloads. Upon investigation, we found that Faasm’s write performance is orders of magnitude higher than its read performance. This is because Faasm lazily pushes writes from worker nodes to MinIO. While Faasm provides interfaces for explicitly synchronization, this operation was not invoked in our benchmarks. Apiary also demonstrates a unique performance trend: as write chance increases, throughput initially decreases then rises again. This behavior is due to transaction conflicts, which only occur under mixed workloads involving both reads and writes.

Except for Faasm under the write-only workload,

LambdaStore outperforms all other systems due to compute-storage colocation. This advantage is especially pronounced under read-only workloads, where

LambdaStore achieves throughput at least an order of magnitude higher than all other systems. However, as the proportion of writes increases, the cost of replication begins to dominate overall performance. Under write-only workloads, the benefit colocation offers is overshadowed by replication overhead, and OpenLambda (SOCK) achieves throughput comparable to

LambdaStore. We also note that, under mixed workloads,

LambdaStore exhibit the performance degradation seen in Apiary, demonstrating the efficiency of

LambdaStore’s transaction interface, which we elaborate in

Section 5.2.3.

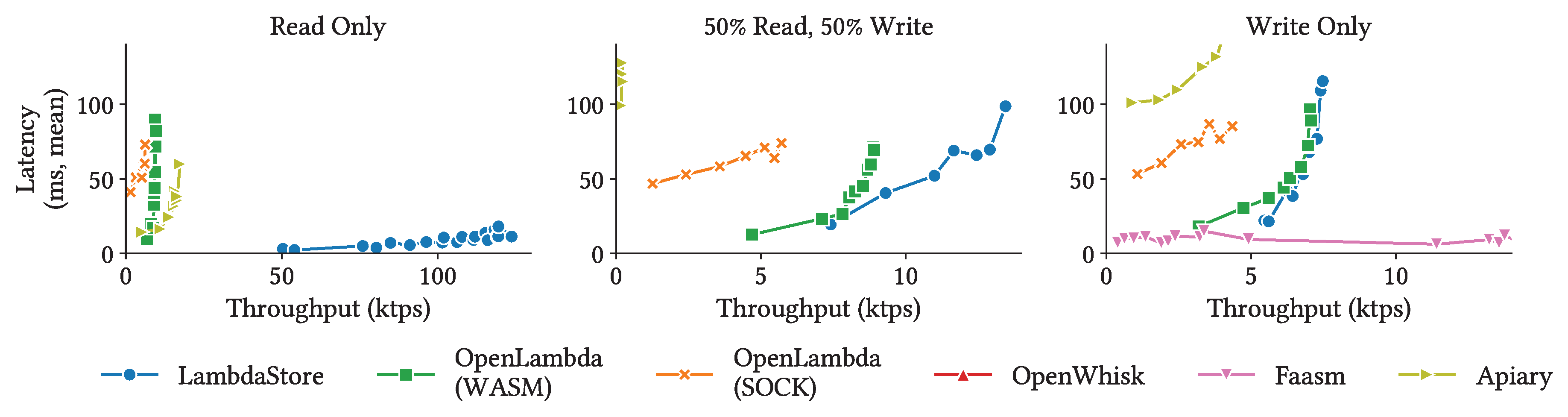

The benefits of colocation become even more apparent when considering latency, as shown in

Figure 5. In this experiment, we vary the number of concurrent requests to adjust total throughput and plot the mean latency against the achieved throughput. Across all workloads,

LambdaStore consistently exhibits lower latencies than all other systems we evaluated (except Faasm under write-only workload). The advantage is most significant under read-only workloads, where

LambdaStore maintains a latency below 20ms throughout the experiment since it avoids fetching data from a remote machine. Under write-only workload,

LambdaStore’s latency is roughly equal to that of OpenLambda (WASM), as the cost of chain replication becomes the dominant factor. Nonetheless,

LambdaStorecontinues to outperform other systems, including OpenWhisk and Apiary.

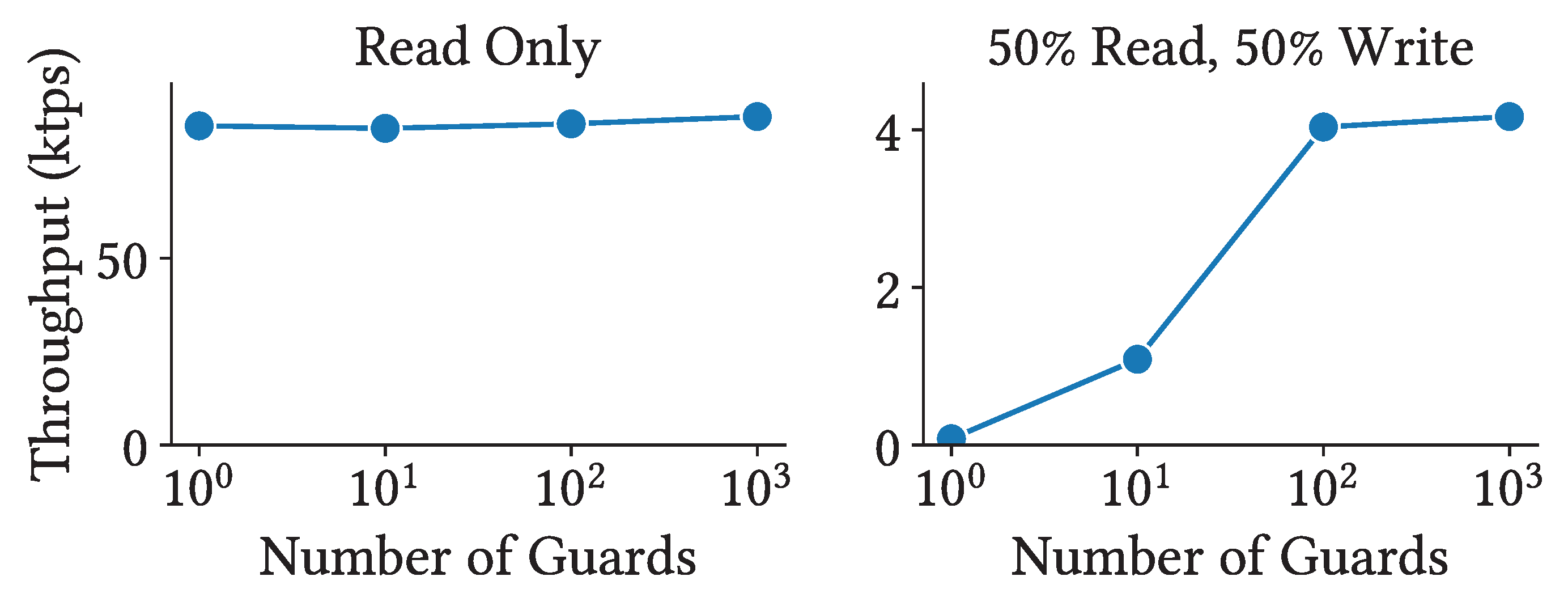

5.2.3. Entry Sets

LambdaStore provides a more efficient transaction interface than Apiary primarily due to dynamic lock granularity through entry sets. While PostgreSQL supports row-level locking as its finest lock granularity,

LambdaStore enables even finer-grained locking for write-heavy objects, reducing contention.

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of lock granularity on performance. In this benchmark, all operations target a single object, creating high lock contention. We manually insert guards into the object prior to execution. Since guards define the boundaries of entry sets, adding more guards results in finer-grained locking, allowing independent workflows to proceed concurrently without conflicts.

We compare two types of workloads: a read-only workload and a mixed workload consisting of 50% reads and 50% writes. In the read-only case, transactions do not conflict, resulting in no lock contention. Consequently, throughput remains constant regardless of the number of guards. In the mixed workload, however, the number of entry sets – and therefore the lock granularity – has a significant impact on performance. As the number of guards increases, throughput improves substantially, up to the point where the number of entry sets exceeds the number of CPU cores on the nodes.

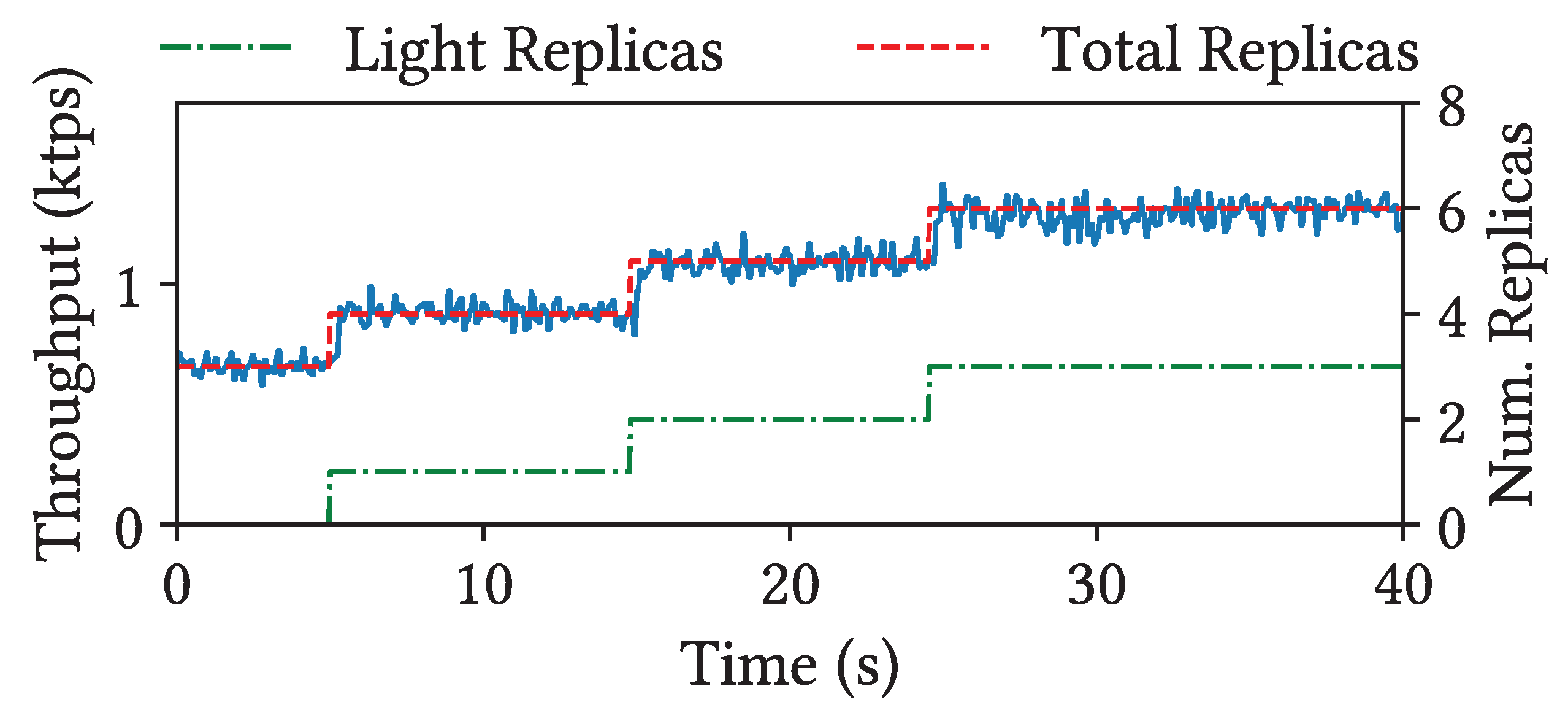

LambdaStoreprovides high elasticity and scalability through light replication. To evaluate its impact, we use a microbenchmark that reads 1 MB of encrypted data. Currently, LambdaStoredoes not implement automated policies to add or remove light replicas based on observed workload Instead, we explicitly instruct the system to create light replicas while the benchmark runs. The test setup begins with a replica set containing three full replicas, and we gradually add up to three light replicas to the shard to observe their effect on total throughput.

Figure 7 presents the results of our experiment. Under this read-only workload, we observe that throughput increases almost linearly with the number of replicas in the shard. However, when the third light replica is added, the performance gain is slightly less than that observed with the first two. This sublinear increase is due to the fact that, regardless of the number of light replicas, the primary replica remains responsible for coordinating transactions. All workloads executed on secondary or light replicas must still be finalized by the primary. As more light replicas are added, the primary eventually becomes a bottleneck, limiting further performance gains. This behavior also suggests that short-running workflows benefit less from light replication than long-running workflows, since the relative cost of transaction coordination becomes more significant for shorter executions.

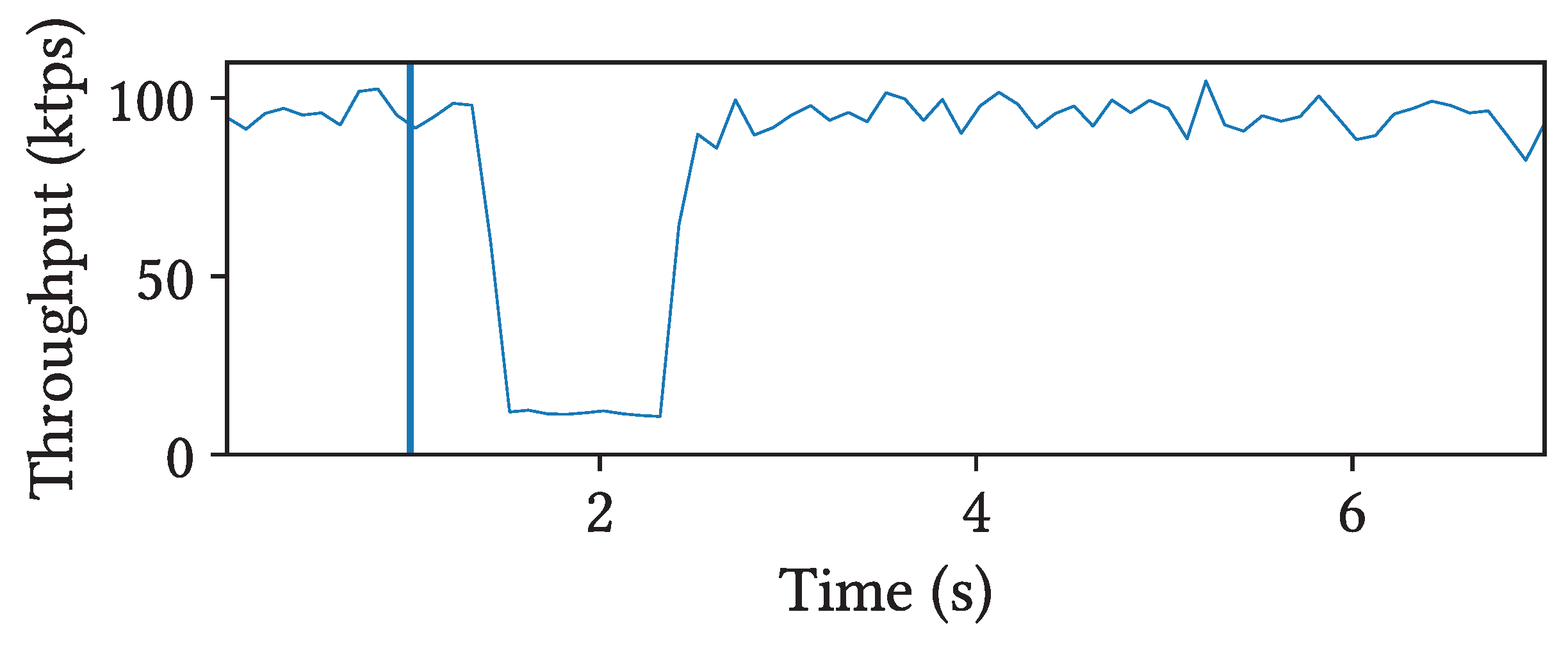

5.2.4. Faulty Functions

Figure 8 illustrates the performance of

LambdaStore when an application’s function refuses to terminate. Specifically, we execute the hashing workload from

Section 5.2.1 on a single node and inject as many non-terminating function calls as the number of worker threads. In this experiment, the maximum execution time for a function is set to 1 second. Before reaching this execution time limit, system throughput is significantly degraded, as the non-terminating functions consume the majority of resources, starving other requests. However, once these faulty functions time out and are terminated, the system’s performance quickly recovers. This behavior contrasts with Apiary, which executes serverless functions as stored procedures in PostgreSQL. In our test with a similarly faulty function, Apiary failed to terminate the function, due to the lack of fine-grained isolation in its execution model.

5.3. Application Performance

We evaluated end-to-end performance using two different application workloads. We first examine

CloudForum, an online message board similar to Reddit, introduced in

Section 3.3. In this application, discussions are organized into

threads, each containing multiple

posts. Threads are grouped under

communities (similar to subreddits). This workload consists of the following transaction types, with their relative frequency indicated in parentheses:

get-thread (90%): Fetches the contents of a thread, including all its posts. This operation is a read-only operation implemented as a single function call.

add-comment (10%): Adds a new post to an existing thread. This operation updates both the thread and the poster’s account, with each update performed by a separate function call.

For this benchmark, we preload the system with 100 communities, containing a total of 100K threads. Each client thread is associated with a unique user account, and the number of concurrent client threads scales with the number of shards in the system.

The second application we use to evaluate the storage system is

Retwis [

50]a benchmark that simulates a Twitter-like social network. In this workload, users can follow other users, create

posts, and retrieve their

timelines that contain the most recent posts from themselves and their followers. This workload consists of the following transaction types:

get-timeline (90%): Fetches the most recent 50 posts on the calling user’s timeline. This is a read-only operation, implemented as a single function call.

create-post (10%): Adds a new post to the timeline of the posting user as well as each of their followers.

We preloaded each user with 20 followers, so a single create-post transaction updates 21 objects. The system was initialized with 500K users, each having 10 followers and 10 posts on their timeline. Each post is 1 KB in size. This setup avoids network bottlenecks.

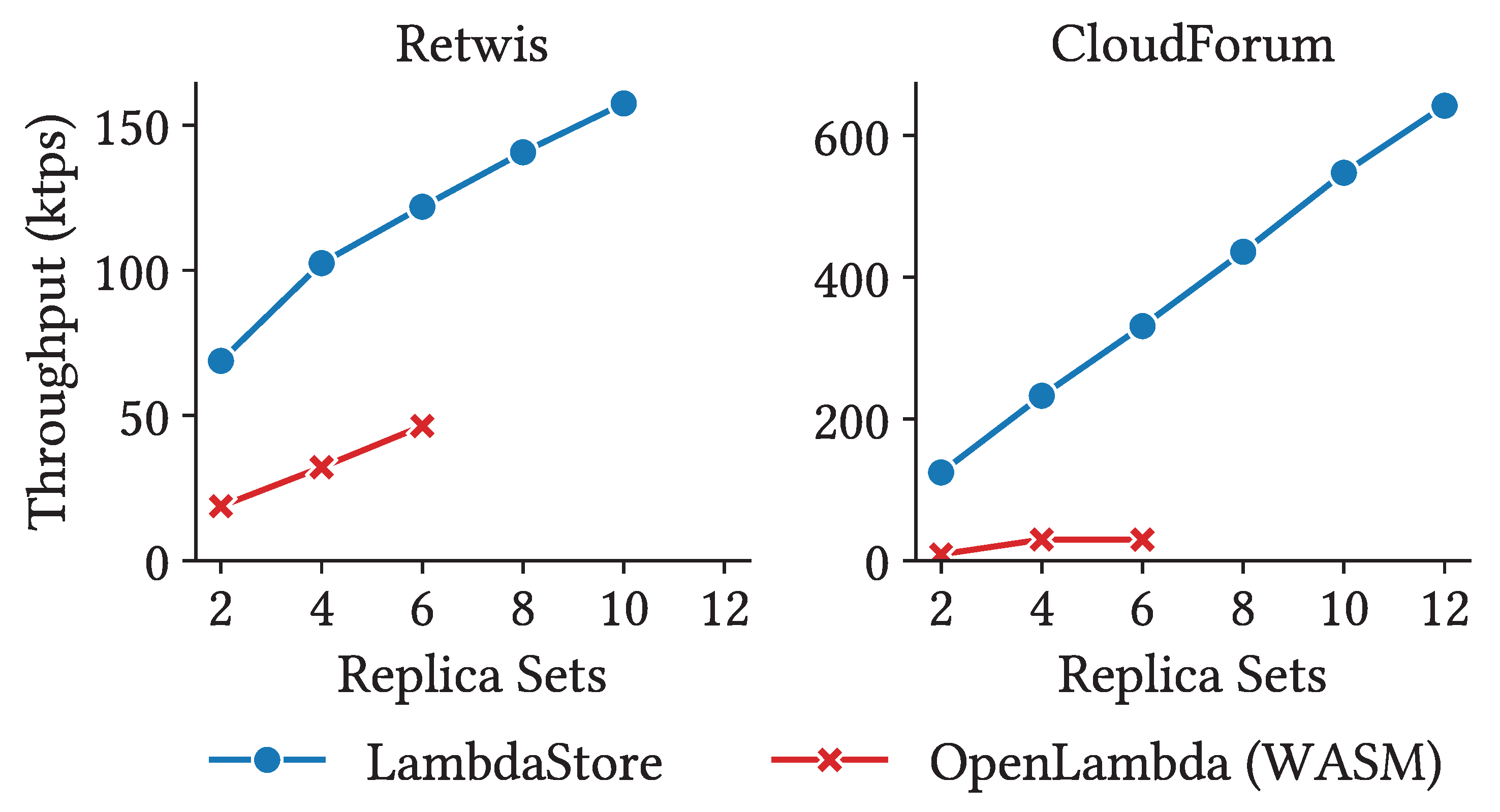

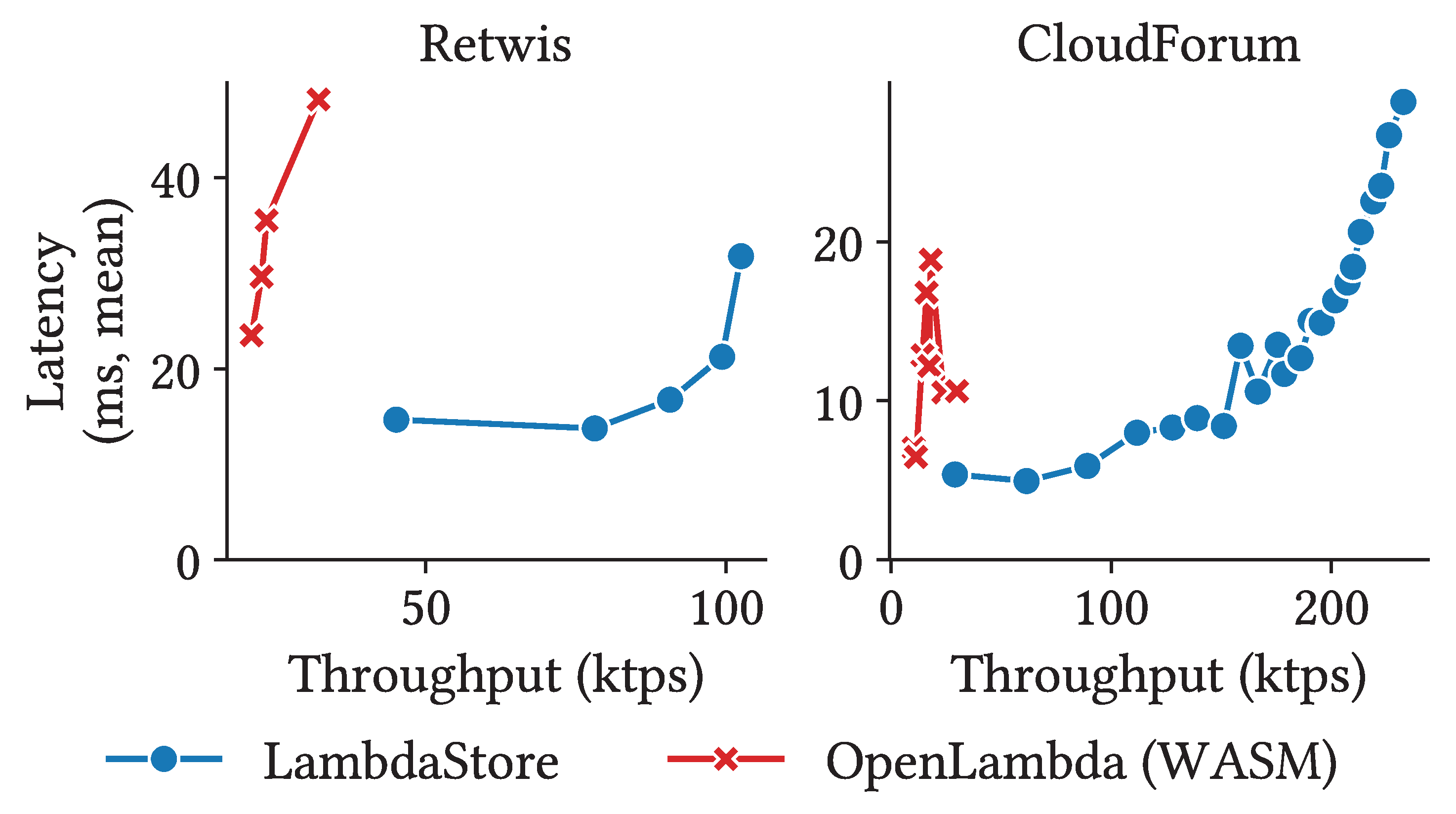

In this experiment, we focus on

LambdaStore and OpenLambda (WASM), as they significantly outperform other systems. To evaluate scalability, we increase the number of replica sets (with three nodes per set). For OpenLambda (WASM), we maintain a one-to-one ratio between compute nodes and storage nodes. For example, with 6 replica sets, we launch 18 nodes for OpenLambda and 18 nodes for

LambdaStore as its storage backend (as its storage backend), totaling 36 nodes.

Figure 9 shows our results. We observe that

LambdaStore scales nearly linearly with the number of replica sets in both applications. While OpenLambda also benefits from increased parallelism, its disaggregated design results in much lower performance despite using twice as many servers. We also present latency vs. throughput curves in

Figure 10. Consistent with the microbenchmark results from

Section 5.2.2,

LambdaStore achieves significantly higher throughput while maintaining low latency. These results suggest that common stateful applications, which typically involves little computation, can benefit greatly from

LambdaStore’s compute-storage co-design.

6. Discussion

Scheduling Policies LambdaStore’s design and implementation open up many scheduling opportunities – including where new objects should be placed, when to migrate an object or create new light replicas, on which replica serverless jobs should run, etc. Its compute-storage co-design enables the scheduler to make more informed decisions by leveraging additional information such as each function’s read-write pattern, the size and location of states it can access, etc. A carefully designed scheduling policy has the potential to further enhance LambdaStore’s performance. We leave the exploration of scheduling policies to future works.

Access Control and Data Sharing Currently, clients can invoke any public function of any application managed by the platform. A future version of LambdaStore should explore session management and access control to isolate applications from one another and protect user data from unauthorized clients. Existing storage systems often have built-in access control mechanisms. While existing storage systems often include built-in access control mechanisms, these could be integrated with session information from the compute layer to enable fine-grained, application-specific access control.

Strict Serializability LambdaStore ensures strict serializability for all workflows; however, not all applications require this strong level of consistency. For instance, consider a long-running task in CloudForumthat analyzes which thread has the most comments. This task may repeatedly fail and retry as concurrent user requests add new comments, leading to frequent conflicts under strict serializability. Such applications could benefit significantly from relaxing the consistency model to snapshot isolation. LambdaStore already supports multiple concurrency control mechanisms offering different consistency guarantees, and it could be extended to run different protocols for different applications. We leave the design of such extensions to future work.

Resource Isolation While WebAssembly provides fault isolation by injecting safeguards at compile time, it does not offer resource isolation at runtime. Fortunately, since LambdaStore maps serverless jobs into its own process space and perform user-level scheduling through Tokio, we can augment the Tokio scheduler to mitigate interference among concurrent jobs. Specifically, we can ensure that no serverless job consumes more resources than it has been allocated. We leave the design and implementation of such resource-aware scheduling to future work.

Support for Legacy Applications A significant limitation of our current design is the lack of support for legacy applications that rely on a POSIX-like API. However, the WebAssembly community is actively developing a standardized system call interface similar to POSIX [

6]. While the object-based model used in

LambdaStore does not directly map to such an interface,

LambdaStore could expose a local file system abstraction for each object by mapping individual files to entries in the object’s storage. This abstraction would allow a legacy application to run as a single object within the system. It is important to note that this approach would still require minor modifications to legacy applications and may not support all system calls.

7. Related Work

Stateful Serverless In the traditional serverless paradigm, functions are

stateless, and external storage services such as Amazon S3 [

9] are used to persist application state. In workloads where multiple serverless jobs operate within the same session, this architecture incurs significant performance overhead due to repeated accesses to the external storage layer by different jobs. To address these limitations, two stateful serverless abstractions have emerged. The first is

workflows, which compose multiple function invocations into larger computations. Amazon Step Functions [

7], Azure Durable Functions [

42] and CloudBurst [

56] follow this abstraction. The second is

actors, where the object-oriented modeling is used. This model is seen in CloudFlare Durable Objects [

16] and Azure Durable Entities [

13].

However, existing actor-based platforms suffer from key limitations. In CloudFlare Durable Objects, requests to the same object are served sequentially, limiting elasticity. Azure Durable Entities, on the other hand, retain the traditional disaggregated architecture and do not support object partitioning, leading to long function startup times due to the need to load the entire object. Moreover, to prevent deadlocks, durable entities are not allowed to invoke functions of other durable entities. LambdaStore addresses all of these problems to meet RAISED properties.

WebAssembly and Serverless Traditional serverless platforms typically rely on mechanisms provided by operating systems, such as virtual machines or containers [

3,

25,

43,

53], to isolate functions. As discussed earlier, these mechanisms suffer from millisecond-scale cold start times due to the overhead of initializing the runtime environment. To reduce this latency, many recent serverless platforms have adopted lightweight software fault isolation techniques [

15,

23,

40,

55]. These platforms often compile functions – along with their dependencies – into WebAssembly [

29], which is then executed in a WebAssembly runtime such as Wasmtime [

5] and Wasmer [

60]. This approach significantly reduces cold start times but may be more susceptible to software bugs due to the reduced isolation provided by user-space runtimes.

LambdaStore adopts this approach and uses Wasmtime as its runtime environment. To our knowledge, none of the existing WebAssembly-based serverless platforms provide serializable transactions, and some – such as Shredder [

55] – do not even support data replication.

Microservices Serverless systems share similarities with microservices, which decompose an application into many semi-independent components [

12,

20,

26,

32,

34]. This architecture promotes fault isolation, as a crash in one service does not directly impact others, and supports development efficiency, enabling different teams to work independently on separate microservice components.

Managing microservices, however, involves provisioning the required resources, starting the services, and handling failures as they arise [

47], all of which typically requires prior knowledge of anticipated workloads and often leads to overprovisioning to handle potential demand spikes.

While microservices improve scalability and resilience, they still require developers to reason explicitly about failures. In particular, cascading failures – where faults propagate across services – can be difficult to debug and mitigate [

41].

8. Conclusion

We described LambdaStore, a new system that unifies storage and execution to better support stateful applications in the serverless setting. LambdaStore delivers improved performance, scalability, elasticity, and transactional guarantees, making it a promising step toward enabling interactive serverless applications. To fully realize this vision, future work should explore more advanced scaling policies and fine-grained access control mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and S.Q.; methodology, K.M., S.Q. and A.J.; software, K.M., S.Q. and A.J.; validation, K.M., S.Q. and A.J.; formal analysis, K.M. and S.Q.; investigation, K.M., S.Q. and A.J.; resources, K.M., S.Q., A.A. and R.A.; data curation, K.M., S.Q. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and S.Q.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and R.A.; visualization, K.M. and S.Q.; supervision, A.A. and R.A.; project administration, K.M.; funding acquisition, A.A. and R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (CNS-2402859).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used GPT-5 for the purposes of grammar checks. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Transaction Correctness Proof

For correctness, it suffices to prove that all transactions that read a version number staler than the value will abort during the prepare phase; the rest follows the correctness of Silo.

Let denote the version number read by the transaction, the version number associated with the value read by the the transaction, the version number managed by the entry set at time t, and the version number associated with the last written value for the given key at time t. For each write committed, is incremented by 1, and we assume without loss of generality that is also incremented by 1 during the update so that after the write is committed.

We first prove that, for each read request, . Since during the commit phase, we always update the version number after writing the new value back to storage, holds for any t. We additionally note that, since transactions acquire the write locks before committing, at any point, only one writer can update the record, so for any t. During each read, the transactions always access the entry set’s version number before the value (). Therefore, .

Next, we prove that all transactions that read a version number older than the corresponding read value () will abort. During the prepare phase, after acquiring all write locks, each transaction walks through its read set. For each record the transaction reads, it checks that the record is not locked by another transaction and the read version number matches the latest version number for that record (i.e., where c is the current check time). If either condition is not met, the transaction aborts. Suppose for a given transaction, one record in the read set has . We first consider if . Then, since , we have . The transaction will abort. On the other hand, if and , then we have and hence . This is a special case where a concurrent transaction in the commit phase tries to update the record, so the record must be locked and the transaction will therefore abort as well.

References

- OpenLambda WebAssembly Worker. https://github.com/open-lambda/open-lambda/tree/main/wasm-worker (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Aamazon. AWS Knowledge Center: How do I make my Lambda function idempotent? https://repost.aws/knowledge-center/lambda-function-idempotent (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Alexandru Agache, Marc Brooker, Alexandra Iordache, Anthony Liguori, Rolf Neugebauer, Phil Piwonka, and Diana-Maria Popa. Firecracker: Lightweight Virtualization for Serverless Applications. Symposium on Networked System Design and Implementation, pages 419-434, Santa Clara, California, February 2020.

- Istemi Ekin Akkus, Ruichuan Chen, Ivica Rimac, Manuel Stein, Klaus Satzke, Andre Beck, Paarijaat Aditya, and Volker Hilt. SAND: Towards High-Performance Serverless Computing. Proceedings of the 2018 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, USENIX ATC 2018, Boston, MA, USA, July 11-13, 2018, pages 923–935, 2018.

- Bytecode Alliance. Wasmtime. https://wasmtime.dev/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- The Bytecode Alliance. WASI: The Web Assembly System Interface. https://wasi.dev/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Amazon. Amazon Step Functions. https://aws.amazon.com/step-functions/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Amazon. Learning Serverless (and why it is hard). 2022. https://pauldjohnston.medium.com/learning-serverless-and-why-it-is-hard-4a53b390c63d (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Amazon. S3 Cloud Object Storage. https://aws.amazon.com/s3/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Muthukaruppan Annamalai, Kaushik Ravichandran, Harish Srinivas, Igor Zinkovsky, Luning Pan, Tony Savor, David Nagle, and Michael Stumm. Sharding the Shards: Managing Datastore Locality at Scale with Akkio. Symposium on Operating System Design and Implementation, pages 445-460, Carlsbad, California, October 2018.

- Ioana Baldini, Paul C. Castro, Kerry Shih-Ping Chang, Perry Cheng, Stephen Fink, Vatche Ishakian, Nick Mitchell, Vinod Muthusamy, Rodric Rabbah, Aleksander Slominski, and Philippe Suter. Serverless Computing: Current Trends and Open Problems. Research Advances in Cloud Computing, pages 1–20, 2017.

- Netflix Technology Blog. Netflix Platform Engineering — we’re just getting started. http://netflixtechblog.com/neflix-platform-engineering-were-just-getting-started-267f65c4d1a7 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Sebastian Burckhardt, Chris Gillum, David Justo, Konstantinos Kallas, Connor McMahon, and Christopher S. Meiklejohn. Durable functions: semantics for stateful serverless. Proc. ACM Program. Lang., 5(OOPSLA):1–27, 2021.

- Cloudflare, Inc. "Why use serverless computing?". https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/serverless/why-use-serverless/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Cloudflare, Inc. Cloudflare Workers. https://workers.cloudflare.com/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Cloudflare, Inc. Using Durable Objects, Cloudflare Docs. https://developers.cloudflare.com/workers/learning/using-durable-objects (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- The Tokio Contributors. tokio-uring. https://github.com/tokio-rs/tokio-uring (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Marcin Copik, Alexandru Calotoiu, Gyorgy Réthy, Roman Böhringer, Rodrigo Bruno, and Torsten Hoefler. Process-as-a-Service: Unifying Elastic and Stateful Clouds with Serverless Processes. Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing, SoCC 2024, Redmond, WA, USA, November 20-22, 2024, pages 223–242, 2024.

- Data Dog. The State of Serverles. https://www.datadoghq.com/state-of-serverless/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Nicola Dragoni, Saverio Giallorenzo, Alberto Lluch-Lafuente, Manuel Mazzara, Fabrizio Montesi, Ruslan Mustafin, and Larisa Safina. Microservices: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Present and Ulterior Software Engineering, pages 195–216, 2017.

- Dmitry Duplyakin, Robert Ricci, Aleksander Maricq, Gary Wong, Jonathon Duerig, Eric Eide, Leigh Stoller, Mike Hibler, David Johnson, Kirk Webb, Aditya Akella, Kuang-Ching Wang, Glenn Ricart, Larry Landweber, Chip Elliott, Michael Zink, Emmanuel Cecchet, Snigdhaswin Kar, and Prabodh Mishra. The Design and Operation of CloudLab. USENIX Annual Technical Conference, pages 1-14, Renton, Washington, July 2019.

- Simon Eismann, Joel Scheuner, Erwin Van Eyk, Maximilian Schwinger, Johannes Grohmann, Nikolas Herbst, Cristina L. Abad, and Alexandru Iosup. Serverless Applications: Why, When, and How? IEEE Softw., 38(1):32–39, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fastly, Inc. Terrarium. https://wasm.fastlylabs.com/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Apache Software Foundation. Apache Kafka. https://kafka.apache.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Apache Software Foundation. OpenWhisk Architecture. https://cwiki.apache.org/confluence/display/OPENWHISK/System+Architecture (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Yu Gan, Yanqi Zhang, Dailun Cheng, Ankitha Shetty, Priyal Rathi, Nayan Katarki, Ariana Bruno, Justin Hu, Brian Ritchken, Brendon Jackson, Kelvin Hu, Meghna Pancholi, Yuan He, Brett Clancy, Chris Colen, Fukang Wen, Catherine Leung, Siyuan Wang, Leon Zaruvinsky, Mateo Espinosa, Rick Lin, Zhongling Liu, Jake Padilla, and Christina Delimitrou. An Open-Source Benchmark Suite for Microservices and Their Hardware-Software Implications for Cloud & Edge Systems. International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, pages 3-18, Providence, Rhode Island, April 2019.

- Google, Inc. Google Cloud Functions. https://cloud.google.com/functions (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Jim Gray, Pat Helland, Patrick E. O’Neil, and Dennis E. Shasha. The Dangers of Replication and a Solution. SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, pages 173-182, Montréal, Canada, June 1996.

- W3 WebAssembly Working Group. WebAssembly Specification. https://webassembly.org/specs/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Joseph M. Hellerstein, Jose M. Faleiro, Joseph Gonzalez, Johann Schleier-Smith, Vikram Sreekanti, Alexey Tumanov, and Chenggang Wu. Serverless Computing: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back. 9th Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research, CIDR 2019, Asilomar, CA, USA, January 13-16, 2019, Online Proceedings, 2019.

- Patrick Hunt, Mahadev Konar, Flavio Paiva Junqueira, and Benjamin C. Reed. ZooKeeper: Wait-free Coordination for Internet-scale Systems. Proceedings of the 2010 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, USENIX ATC 2010, Boston, MA, USA, June 23-25, 2010, 2010.

- IBM. What are Microservices? https://www.ibm.com/topics/microservices (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Zhipeng Jia and Emmett Witchel. Boki: Stateful Serverless Computing with Shared Logs. SOSP ’21: ACM SIGOPS 28th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Virtual Event / Koblenz, Germany, October 26-29, 2021, pages 691–707, 2021.

- Zhipeng Jia and Emmett Witchel. Nightcore: efficient and scalable serverless computing for latency-sensitive, interactive microservices. International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, pages 152-166, Virtual, Anywhere, April 2021.

- Ana Klimovic, Yawen Wang, Christos Kozyrakis, Patrick Stuedi, Jonas Pfefferle, and Animesh Trivedi. Understanding Ephemeral Storage for Serverless Analytics. USENIX Annual Technical Conference, pages 789-794, Boston, Massachusetts, July 2018.

- Ana Klimovic, Yawen Wang, Patrick Stuedi, Animesh Trivedi, Jonas Pfefferle, and Christos Kozyrakis. Pocket: Elastic Ephemeral Storage for Serverless Analytics. 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, OSDI 2018, Carlsbad, CA, USA, October 8-10, 2018, pages 427–444, 2018.

- Peter Kraft, Qian Li, Kostis Kaffes, Athinagoras Skiadopoulos, Deeptaanshu Kumar, Danny Cho, Jason Li, Robert Redmond, Nathan W. Weckwerth, Brian S. Xia, Peter Bailis, Michael J. Cafarella, Goetz Graefe, Jeremy Kepner, Christos Kozyrakis, Michael Stonebraker, Lalith Suresh, Xiangyao Yu, and Matei Zaharia. Apiary: A DBMS-Backed Transactional Function-as-a-Service Framework. CoRR, abs/2208.13068, 2022.

- Leslie Lamport, Robert E. Shostak, and Marshall C. Pease. The Byzantine Generals Problem. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 4(3):382-401, 1982.

- Marketsandmarkets Private Ltd. Serverless Architecture Market. https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/serverless-architecture-market-64917099.htm (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kai Mast, Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau, and Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau. LambdaObjects: re-aggregating storage and execution for cloud computing. Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems, pages 15-22, Virtual, Anywhere, June 2022.

- Christopher S. Meiklejohn, Andrea Estrada, Yiwen Song, Heather Miller, and Rohan Padhye. Service-Level Fault Injection Testing. SoCC ’21: ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing, Seattle, WA, USA, November 1 - 4, 2021, pages 388–402, 2021.

- Microsoft. Azure Durable Functions. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/azure-functions/durable/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Microsoft. Azure Functions. https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/services/functions/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- MinIO, Inc. MinIO. https://min.io/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Alan Nair, Raven Szewczyk, Donald Jennings, and Antonio Barbalace. Near-Storage Processing in FaaS Environments with Funclets. Proceedings of the 25th International Middleware Conference, MIDDLEWARE 2024, Hong Kong, SAR, China, December 2-6, 2024, pages 145–157, 2024.

- Edward Oakes, Leon Yang, Dennis Zhou, Kevin Houck, Tyler Harter, Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau, and Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau. SOCK: Rapid Task Provisioning with Serverless-Optimized Containers. USENIX Annual Technical Conference, pages 57-70, Boston, Massachusetts, July 2018.

- Mehmet Ozkaya. Deploying Microservices on Kubernetes. https://medium.com/aspnetrun/deploying-microservices-on-kubernetes-35296d369fdb (accessed on 1 April 2023).