This section outlines environmental tests conducted initially using internal stimuli via the Signal Tap Logic Analyzer, followed by external signals applied to the input of the TDC64 to measure a specific interval. Additionally, it includes a discussion of experimental results that compares matching improvements and provide an evaluation against similar studies.

A. Environment Testing

The system is comprised of a bench integrating a DE10-Nano development board alongside a personal computer. The PC is configured with Intel's Quartus Prime Lite 20.1.1 Electronic Design Automation software. The FPGA used belongs to the Cyclone V family, specifically the 5CSEBA6U23I7 device. Current logic utilization is minimal, accounting for only 1% of the available resources at 528 registers and 6% of the total pins.

Internal evaluations were performed utilizing the Signal Tap Logic Analyzer, an embedded signal analysis and debugging utility integrated in Quartus Prime. By operating on actual hardware, Signal Tap enables the capture of logic signal waveforms from the design, allowing for the estimation of certain outcomes based on this tool's output.

The setup comprises a DSO-X3024T oscilloscope and a 33600A Series waveform generator. Initially, the generator was configured to output two square waves at a frequency of 10 kHz, each delayed by 300 nanoseconds and with an amplitude of 3.3 Vpp. These signals functioned as the external input for the TDC64. Subsequently, the signal was modified to a pulse with a slew rate of 40 ns and maintained at 3.3 Vpp at the same frequency. The environment also includes a set of male/female jumper wires for accessing the 40-pin GPIO header, as well as BNC cables featuring various shielding levels for both signal and ground, and resistors for 50-ohm impedance matching.

B. Experimental Results

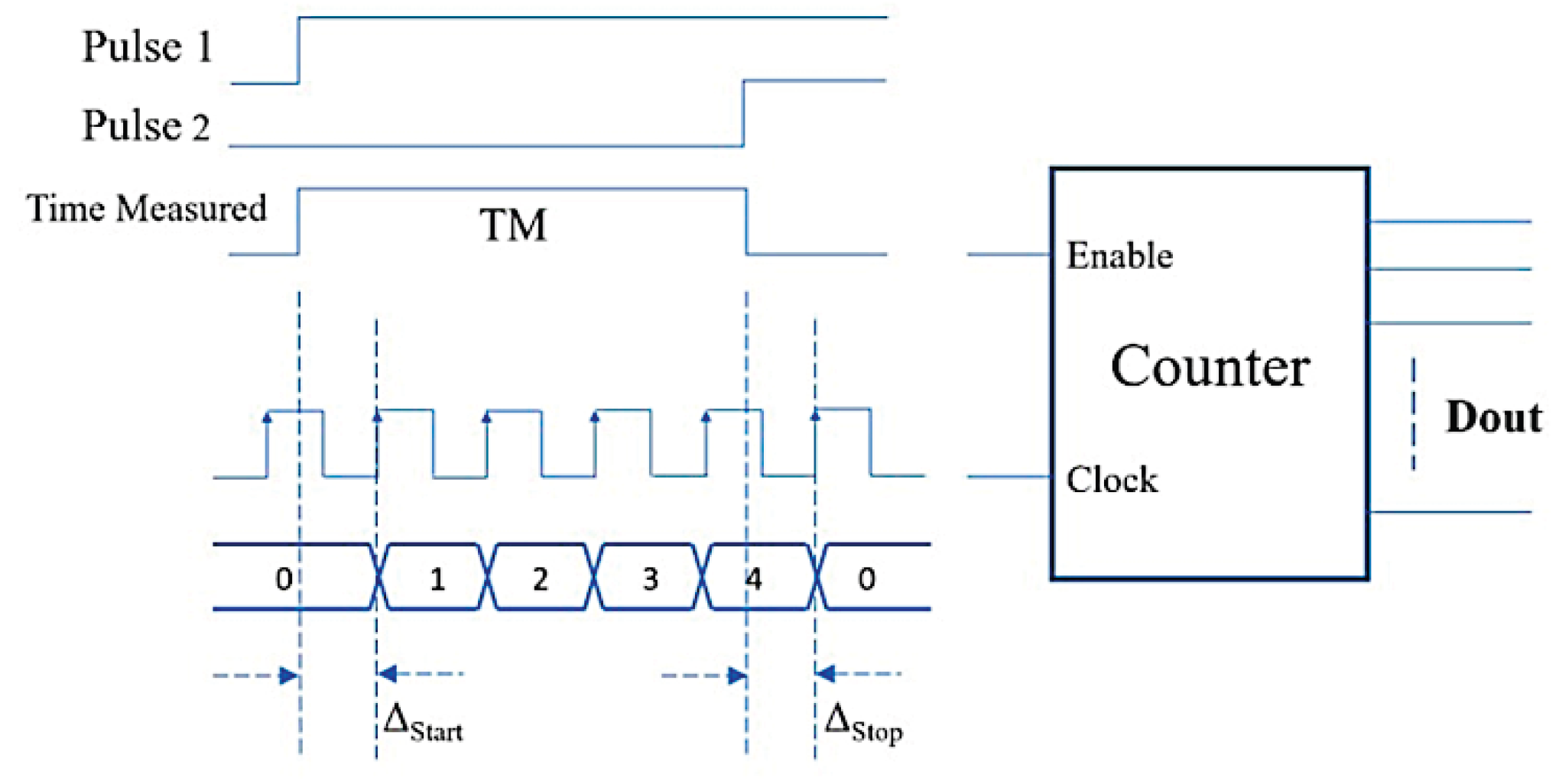

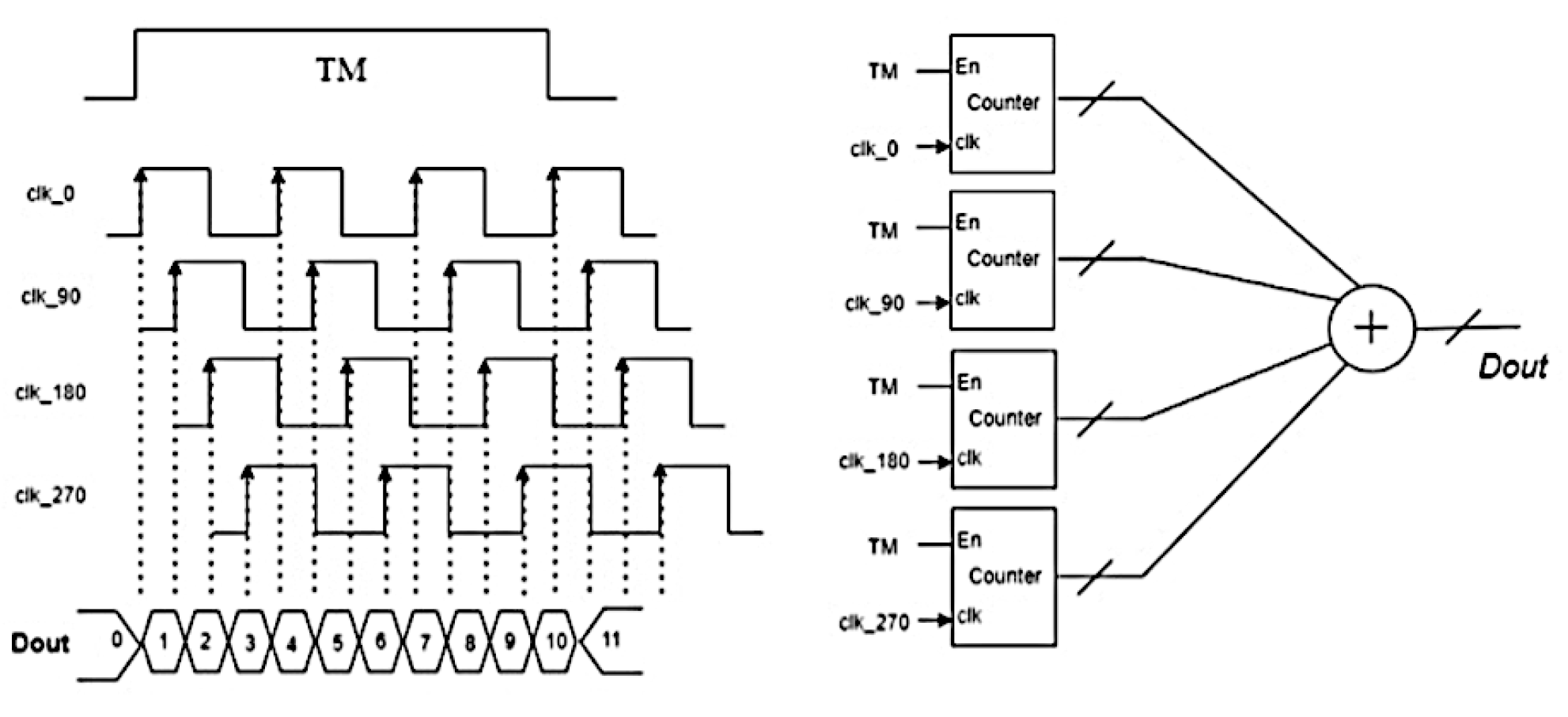

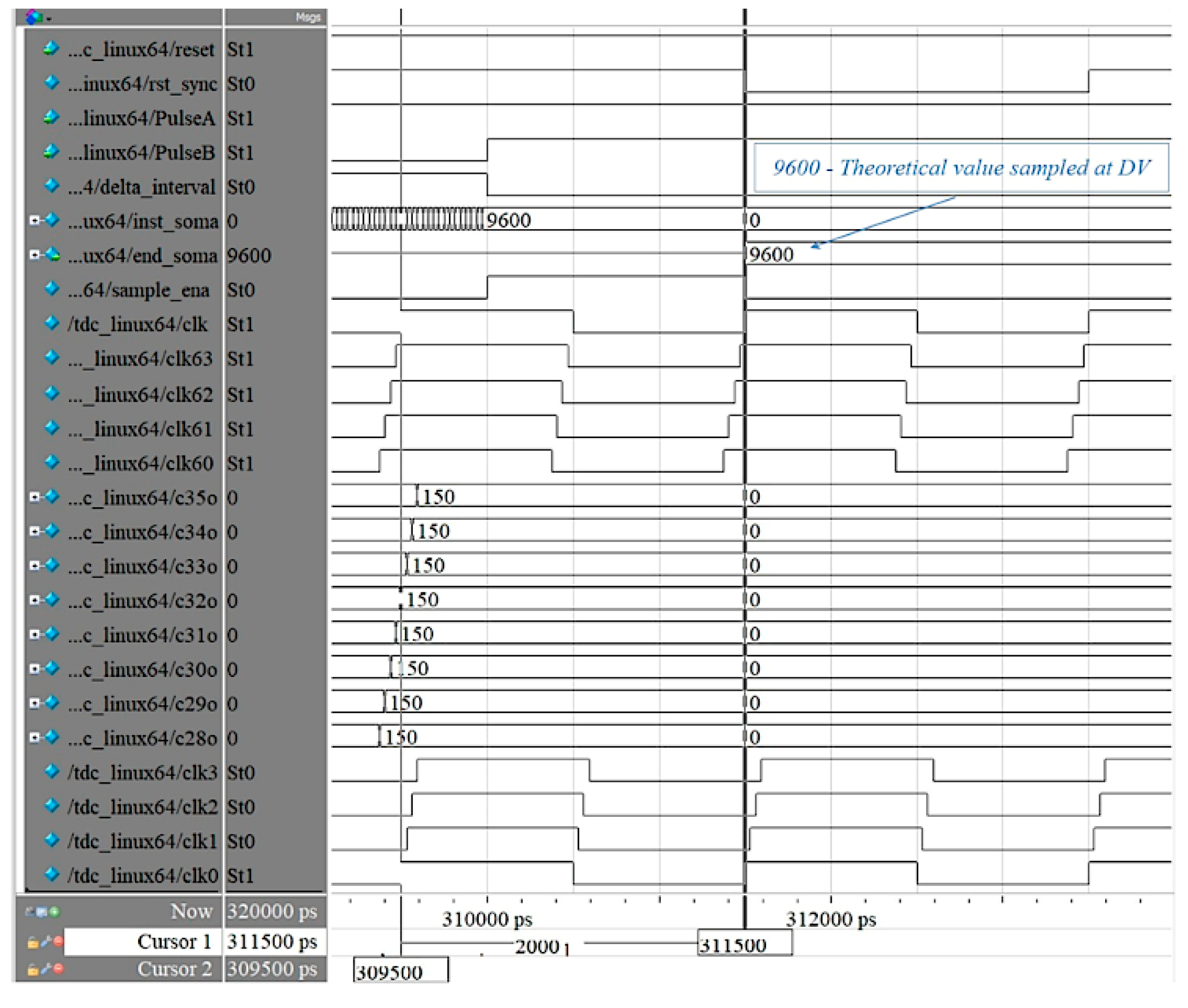

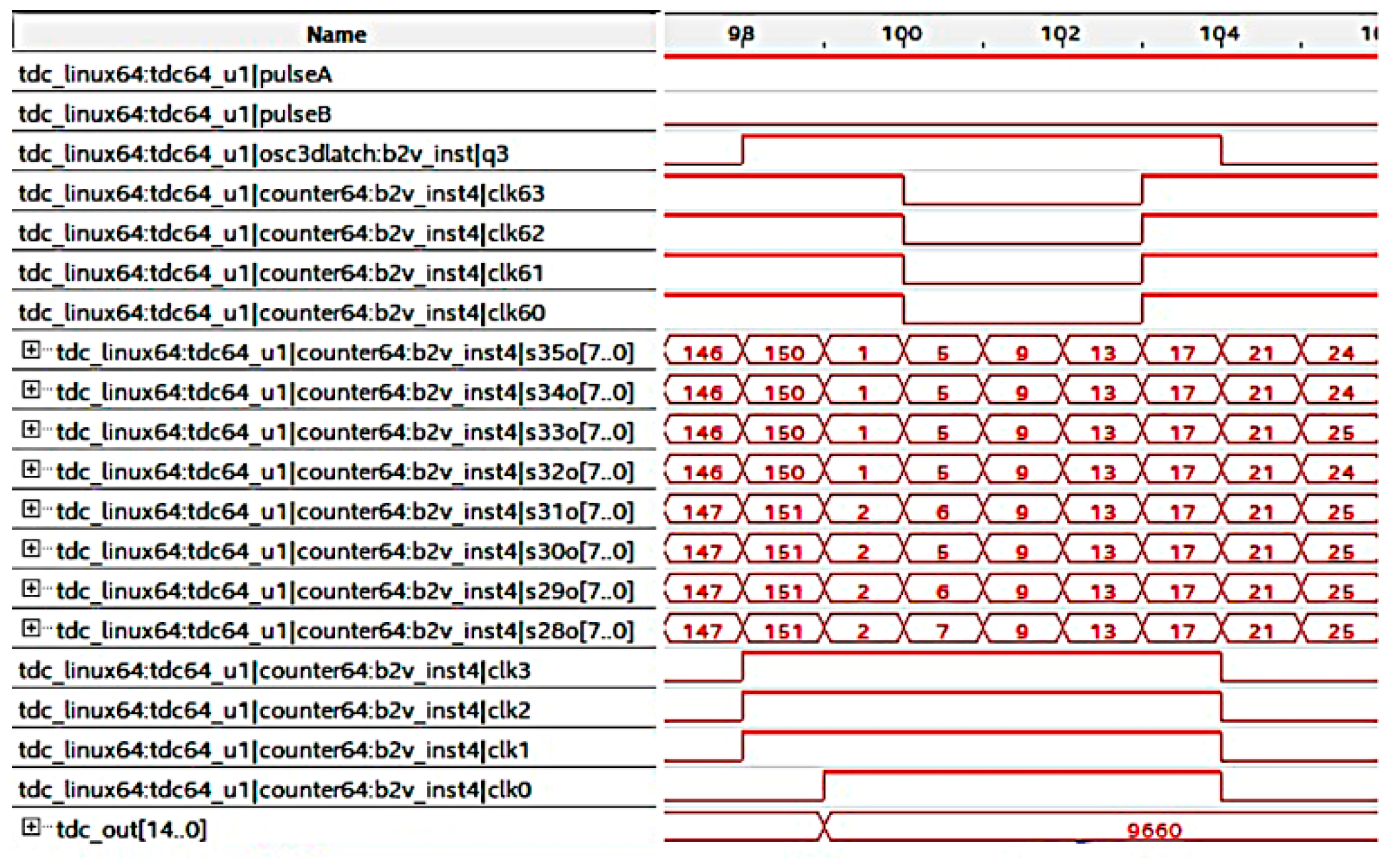

The experimental results were evaluated in two phases: initially by analyzing internal FPGA signals using generated signals within the device, and subsequently by assessing external signals with waveform equipment and an oscilloscope. To evaluate the internal signals of the design, a 300-nanosecond interval was established in Signal Tap, facilitating verification of the TDC64’s functionality. This methodology enabled comprehensive analysis of the FPGA's internal signals and systematic assessment of system behavior.

Figure 5 illustrates the same time interval selected for the simulation, with the measured result being 9660. This represents a deviation of approximately 0.62%, remaining within the 1% margin.

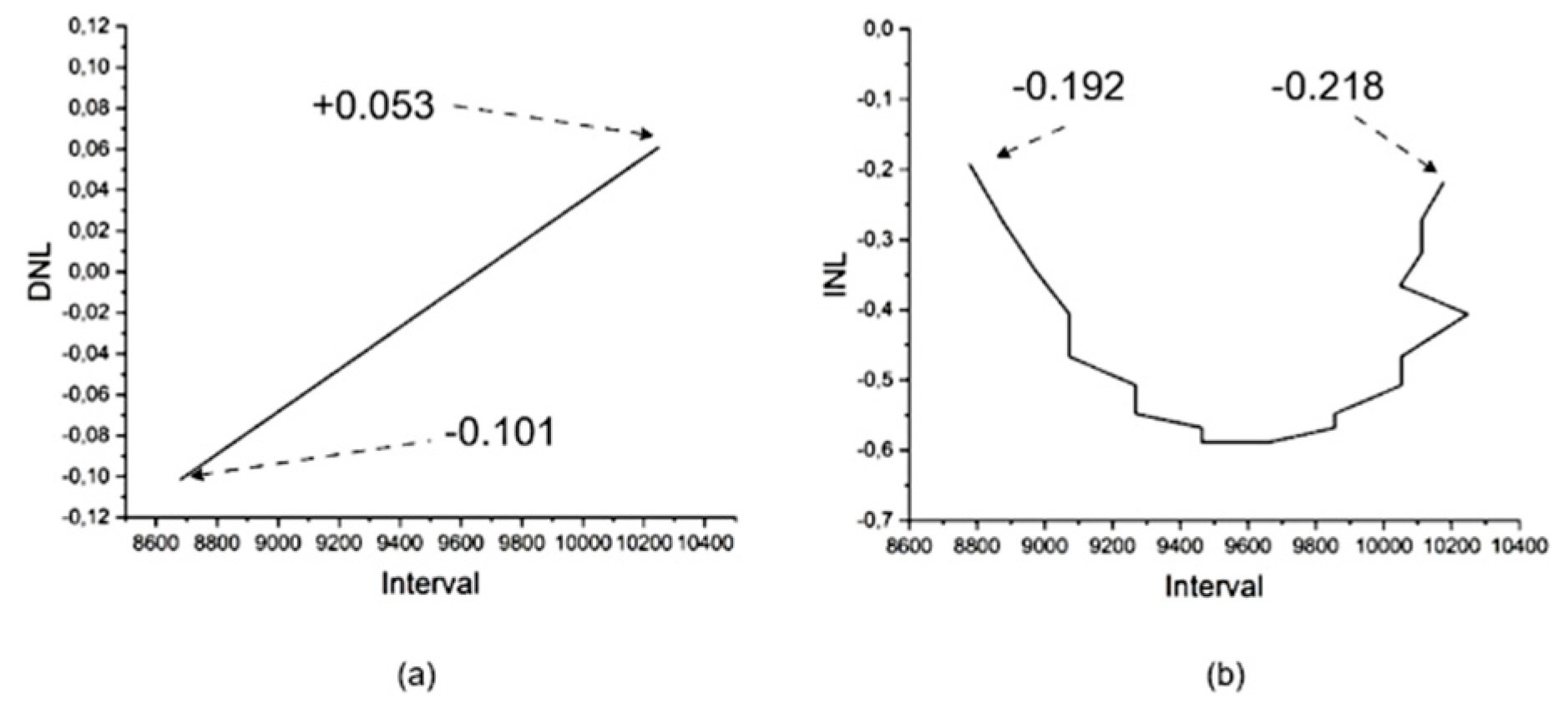

Linearity assessments were performed using 64 samples over 21-time intervals, ranging from 290 ns to 310 ns in 1 ns increment. Since 64 samples remain constant for any specific interval, the differential nonlinearity (DNL) values varied between +0.053 and -0.101, while the integral nonlinearity (INL) values ranged from -0.192 to -0.218.

Figure 6 presents the differential nonlinearity (a) and integral nonlinearity (b) as observed in Signal Tap.

To address significant noise issues, Signal B was reassigned to an alternative GPIO pin expansion header, resulting in a substantial reduction in interference.

External signals were connected to GPIO pins Signal A and Signal B, which were originally assigned to adjacent positions in the pin planner. However, significant signal reflections and crosstalk adversely impacted the accuracy of TDC measurements, resulting in inconsistencies when compared to both simulation data and Signal Tap observations.

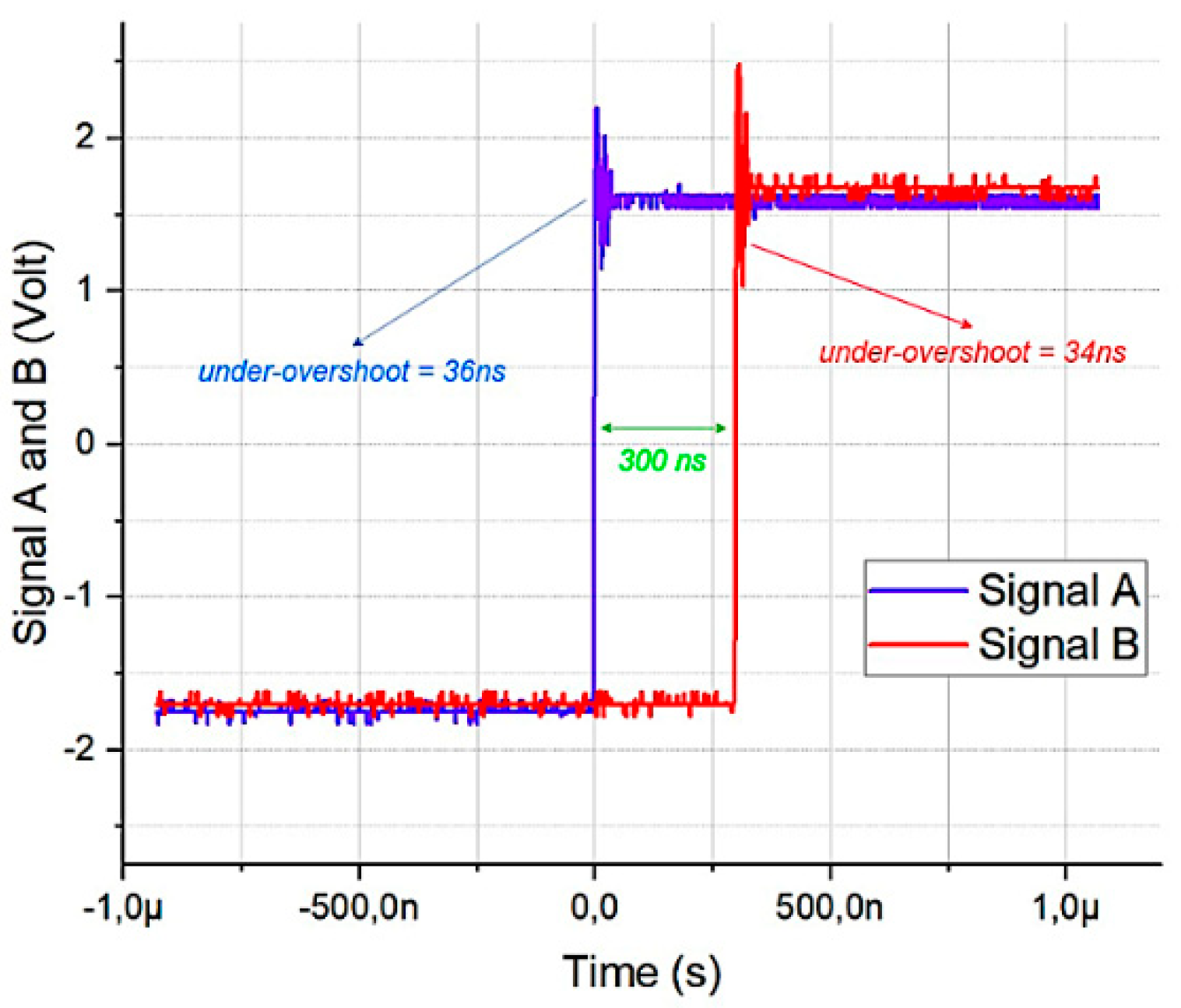

Figure 7 illustrates the external signal produced by the waveform generator and recorded using an oscilloscope. Although enhancements have been implemented, under-overshoot can still be detected on both signals: Signal A (blue) at 36 ns and Signal B (red) at 34 ns.

The FPGA's Hard Processor System (HPS) was configured to execute custom algorithms, facilitating enhanced system flexibility and adaptability under varying operating conditions. This configuration enabled the accurate measurement of a 300-nanosecond external interval over 1450 samples. Sequential measurements of the two signals were performed every 100 microseconds, aligning with the 10 kHz period of each signal. Data collected from these measurements were compiled into an .csv file containing 1450 entries, which produced an average value of 6325.

By dividing the 300-nanosecond measurement interval by 6,325, a resolution of 47.43 picoseconds was achieved, representing a 34% deviation from the theoretical value, considered a high deviation. The average value was employed to evaluate system linearity, yielding differential nonlinearity (DNL) values of +0.0572 and -0.0284, as well as integral nonlinearity (INL) values of +0.1237 and -0.6215. Representing a good linearity.

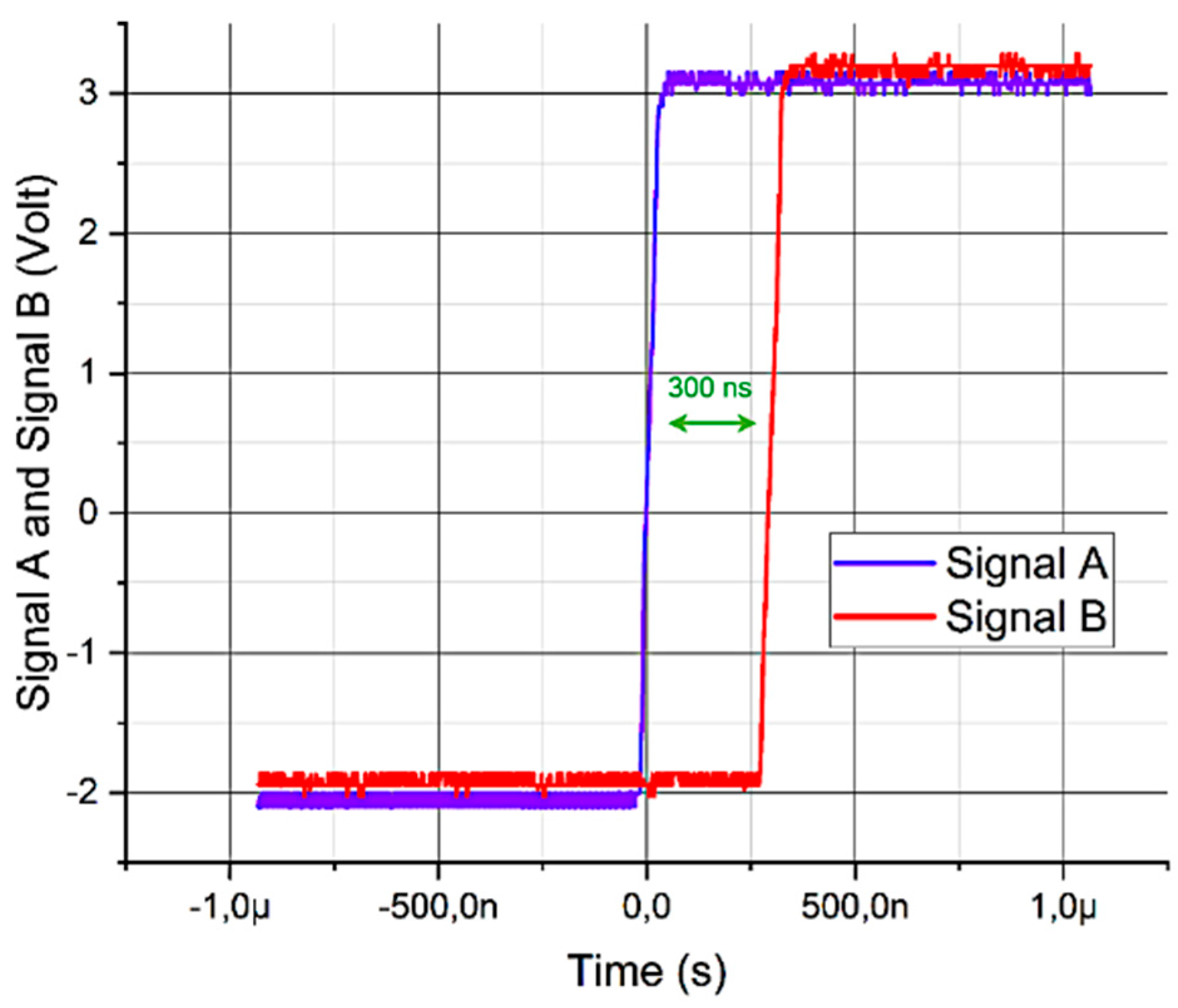

Noise mitigation techniques were implemented, including replacing standard oscilloscope cables with BNC cables featuring a more effective shielding mesh rated at 50 ohms. Series resistors were added to the GPIO input for improved impedance matching. Furthermore, square wave signals were replaced by equivalent pulses with a 40ns slew rate, as direct entry of signals A and B into the gate caused reflections due to abrupt transitions in square waves.

These actions led to a significant improvement in the entry signals.

Figure 8 illustrates the data extracted from the oscilloscope’s input signal after mitigating noises.

The data obtained from measurements conducted without overshooting were recorded in a second .csv file, and the corresponding analysis results are presented below.

As with the previous data set, 1,450 samples were extracted, yielding a mean value of approximately 9,596 and a resolution of 31.263 picoseconds, which represents 0.04%. This result is remarkably close to the theoretically expected value. The mean values were employed to evaluate again the linearity, yielding DNL values of +0.0560 and -0.0129, as well as INL values of +0.0484 and -0.2104. Representing better linearity compared with the noisy entry signal.

Figure 9 presents the differential nonlinearity (a) and integral nonlinearity (b) calculated from the external signal after noise mitigation.

A comparison between samples exhibiting overshoots and those without reveals that, in the absence of noise, the mean closely approximated the theoretical value. Additionally, these samples demonstrated a lower standard deviation relative to their noisy counterparts. Table I provides descriptive statistics summarizing the entire sample set.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Samples |

Overshoot |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

| 1450 |

With |

6325.14 |

78.77 |

| 1450 |

Without |

9596.29 |

43.54 |

The comparative analysis clearly demonstrates that noise mitigation techniques substantially enhance both the accuracy and linearity of the measurement system. The results indicate that the mean value for noise-free samples is not only closer to the theoretical expectation but also exhibits a significantly reduced standard deviation, highlighting improved consistency across measurements. This improvement underscores the critical role of effective signal conditioning in high-precision timing applications.

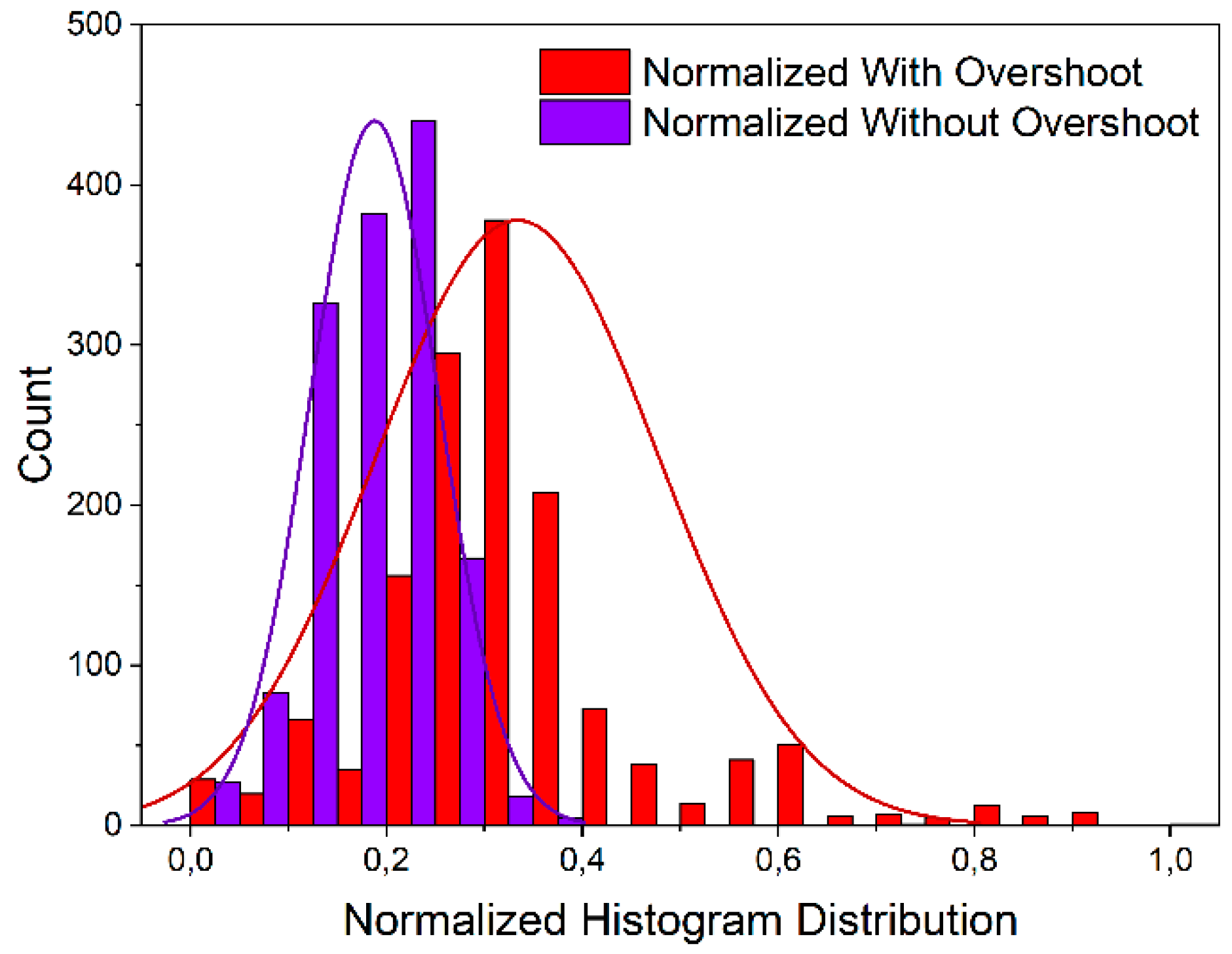

Figure 10 illustrates a comparative histogram of two normalized distributions: one incorporating overshoot (red) and one without overshoot (blue). The x-axis represents the normalized histogram distribution ranging from 0.0 to 1.0, while the y-axis indicates the count of occurrences within each bin, extending up to 500.

The distribution with overshoot exhibits a broader spread across the entire range, with a peak centered around 0.35. This suggests a higher range of midrange values and increased variability. In contrast, the distribution without overshoot is more concentrated in the lower range, peaking near 0.2, and tapering off rapidly beyond 0.4, indicating a more compact and less dispersed dataset.

Both histograms are overlaid with smooth density curves that highlight the underlying probability distributions. The red curve (with overshoot) is flatter and wider, reflecting greater dispersion, while the blue curve (without overshoot) is narrower and taller, emphasizing the concentration of values in the lower range.

This comparison illustrates the impact of overshoot on measurements, where the presence of overshoot leads to a spread distribution across the normalized scale, whereas its absence results in clustering toward expected values.

C. Discussions and Considerations

All TDC64 counters are activated by the XOR logic gate signal output from the DT block. Due to the significant under-overshoot observed, the counters might have been momentarily disabled from counting during this period. Not considering the under-overshoot, the resolution varied by 34%, resulting in a resolution of 47.43 picoseconds. Given that signal A exhibited an under-overshoot of 36 ns and signal B of 34 ns, and assuming the counters remained inactive during this time, the effective time interval can be approximated as 230 nanoseconds. Recalculating the resolution with this interval is obtained by a resolution of 36.36 picoseconds.

Eliminating the overshooting the high resolution and the high linear approach of the multi-phased TDC64 was confirmed, allowing a meaningful comparison with previous studies specifically referenced in [

22], comparing analysis of this work with earlier techniques. In both internal and external approaches, the TDC64 proved to be precise and quite linear.

FPGA vendors such as Altera and Xilinx offer families tailored for both high-end and low-end applications. While the Stratix series from Altera and the Virtex series from Xilinx cater to high-end designs, the Cyclone series from Altera, along with the Kintex7 and Spartan series from Xilinx, are optimized for low-cost applications.

The FPGA most closely related to this work is the Kintex7 [

23] (Wang et al., 2016), which utilizes three phase-locked loops (PLLs) within its clock management block to produce eight-phase clock signals. The initial PLL converts a 200 MHz input clock into a 700 MHz output, while the remaining two PLLs generate eight outputs at an identical frequency, each with a 22.5-degree phase offset. Flip-flops are configured to be triggered on alternating clock edges. Two principal methods are used to generate multiphase clocks: introducing phase shifts via a delay line or employing PLLs/DLLs.

A gated ring oscillator (GRO) is utilized to generate the primary clock in this work, which is subsequently phase-shifted to construct the clock tree with a phase increment of 5.625 degrees.

This approach efficiently reduces the number of blocks, resulting in lower logic utilization while preserving both performance and portability, all without relying on proprietary instructions. Achieving a resolution around 31.26 picoseconds demonstrates the capability of low-cost FPGA solutions.

This work presents a comparative summary of three FPGA-based Time-to-Digital Converter (TDC) implementations: Wang et al. [

23], Mattada et al. [

22], and the proposed architecture described herein. The evaluation encompasses essential performance metrics, including number of phases, operating frequency, time resolution, linearity characteristics, and the specific FPGA platform utilized.

The proposed design in This Work demonstrates significant improvements across multiple phases. It utilizes 64 phases, doubling the phase count of Mattada et al. and quadrupling that of Wang et al., thereby enhancing temporal granularity. Despite operating at the same frequency as Mattada et al. (500 MHz), it achieves a superior time resolution of 31.26 ps, which is nearly half that of Mattada et al. (62.5 ps) and substantially better than Wang et al. (89.9 ps).

In terms of linearity, the proposed design exhibits markedly reduced Differential Non-Linearity (DNL) and Integral Non-Linearity (INL). The DNL ranges from +0.06 to -0.13, and the INL from +0.05 to -0.21, indicating high precision and minimal deviation. These values are significantly lower than those reported by Wang et al. and Mattada et al., whose DNL and INL values exceed ±0.8 in some cases.

Furthermore, the implementation leverages the Cyclone 5 FPGA platform (low cost in 2025), which reflects an update in terms of design becoming potentially more efficient hardware environment compared to the Kintex7 (2016) and Virtex 5 (2022) platforms used in prior works.

Overall, the proposed architecture achieves enhanced resolution and linearity without increasing the operating frequency, showcasing an efficient and scalable approach to high-precision TDC design on cost-effective FPGA platforms.