1. Introduction

Oncofetal reprogramming, the reactivation of embryonic and fetal gene expression programs in cancer cells, has emerged as a key concept in translational oncology with profound implications for clinical treatment regimens [

1]. Under physiological conditions, the set of oncofetal genes is exclusively expressed during embryogenesis, where they play specialized roles in cell fate specification, tissue morphogenesis, and pluripotency [

2,

3,

4]. Following development, these genes are robustly suppressed, ensuring the maintenance of lineage identity and tissue homeostasis throughout adult life [

2,

3,

4]. However, accumulating evidence reveals that malignant transformation in several cancers, including colorectal (CRC), breast, lung, and liver, can hijack these early developmental programs, resulting in tumor cells with enhanced plasticity and the capacity to evade therapeutic interventions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Reactivation of oncofetal genes is not a universal phenomenon across all tumor cells; rather, it marks a distinct subpopulation within the tumor mass, one that exhibits heightened adaptability and resistance to pharmacological and immune-mediated therapies [

6,

9]. These cells often exploit oncofetal transcriptional regulators to modulate differentiation trajectories, remodel the tumor microenvironment, and orchestrate evasive responses that hinder the efficacy of standard-of-care treatments [

6]). Recent multi-omic and single-cell profiling studies have revealed insights about the landscape of oncofetal gene reactivation across cancer types, revealing both shared and context-dependent drivers in different cancers to pioneer more effective therapeutic interventions [

9,

10,

11].

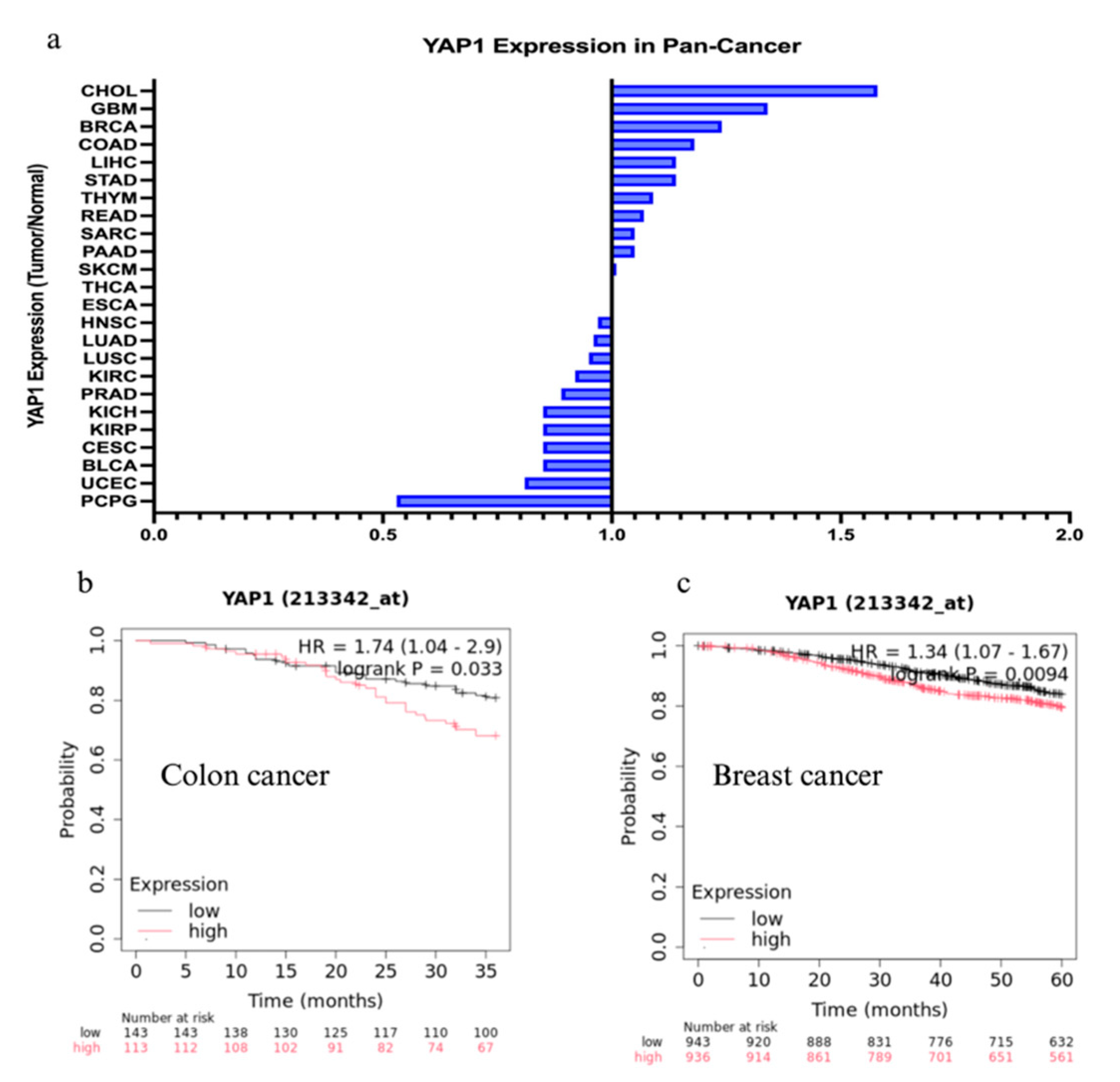

Among key molecular drivers, the transcriptional regulators YAP1 and AP-1 (c-Jun/Fos family) have emerged as central player of oncofetal reprogramming [

9,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. YAP1, a principal effector of the Hippo pathway, operates as an initiator to drive the aberrant expression of embryonic gene modules in malignancies such as CRC and breast cancer (

Figure 1a) [

17,

18]. YAP1’s reactivation is frequently associated with stemness, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and resistance to chemotherapy or targeted modalities [

17,

18]. AP-1 family members further reinforce this transcriptional state, cooperating with YAP1 and other cofactors to establish oncogenic chromatin landscapes that are permissive to oncofetal gene expression [

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, tumor recurrence and resistance frequently correlate with the presence of YAP1- and AP-1-driven oncofetal cell populations, which exhibit both intrinsic insensitivity to conventional therapies and the capacity to repopulate the tumor following treatment-induced damage [

9,

22,

23]). In CRC and breast cancer, patients with high expression of YAP1 will have lower overall survival (

Figure 1b, 1c). Notably, recent work has demonstrated that oncofetal program activation can modulate the tumor microenvironment, promote immune evasion, and suppress antitumor immune responses, thus complicating the efficacy of immunotherapy in cancers such as lung and liver [

6,

24,

25]. Understanding oncofetal reprogramming will allow clinicians to shift toward dual-targeting strategies that simultaneously attack conventional cancer stem cells and oncofetal-reprogrammed populations, aiming to more durably overcome resistance and reduce relapse rates.

This review critically synthesizes recent landmark studies, delineates the mechanistic underpinnings of oncofetal-driven resistance, and highlights emerging therapeutic regimens designed to target these oncofetal drivers in a spectrum of malignancies.

YAP1 Expression Ratio (Tumor/Normal) in Pan-Cancer

Median expression ratio of YAP1 in tumor tissue compared to adjacent normal tissue across multiple cancer types (Pan-Cancer analysis) using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data. Cancer Type Abbreviations (TCGA): CHOL (Cholangiocarcinoma), GBM (Glioblastoma multiforme), BRCA (Breast invasive carcinoma), COAD (Colon adenocarcinoma), LIHC (Liver hepatocellular carcinoma), STAD (Stomach adenocarcinoma), THYM (Thymoma), READ (Rectum adenocarcinoma), SARC (Sarcoma), PAAD (Pancreatic adenocarcinoma), SKCM (Skin Cutaneous Melanoma), THCA (Thyroid carcinoma), PRAD (Prostate adenocarcinoma), HNSC (Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma), LUAD (Lung adenocarcinoma), LUSC (Lung squamous cell carcinoma), KIRC (Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma), PRAD (Prostate adenocarcinoma), KICH (Kidney Chromophobe), KIRP (Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma), CESC (Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma), ESCA (Esophageal carcinoma), UCEC (Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma), PCPG (Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma).

Overall Survival (OS) in Colon Cancer

Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.74 (1.04 - 2.9): Indicates that patients with high YAP1 expression have a 1.74 times higher risk of death compared to those with low YAP1 expression. Log-rank P = 0.033: the difference in overall survival between the high and low YAP1 expression groups is statistically significant, suggesting high YAP1 expression is associated with worse prognosis in colon cancer.

Overall Survival (OS) in Breast Cancer

Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.34 (1.07 - 1.67): Indicates that patients with high YAP1 expression have a 1.34 times higher risk of death compared to those with low YAP1 expression. Log-rank P = 0.0094: the difference in overall survival between the high and low YAP1 expression groups is statistically significant, suggesting high YAP1 expression is associated with worse prognosis in breast cancer.

2. Methods - Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.1. Pan-Cancer Analysis from TCGA

Transcript per million (TPM) values of YAP1 gene were extracted from The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort to obtain the median expression levels between normal and tumor samples in each dataset. The ratio is calculated as: Median YAP1 Expression -Tumor / Median YAP1 Expression - Normal. A ratio greater than 1.0 indicates upregulation (higher expression) of YAP1 in the tumor compared to normal tissue. A ratio less than 1.0 indicates downregulation (lower expression) of YAP1 in the tumor compared to normal tissue.

2.2. Survival Analysis

A Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curve generated using the KMPlotter tool (mRNA breast/ colon cancer cohorts) illustrates the probability of overall survival over time, stratified by YAP1 expression levels (high vs. low).

2.3. Gene Expression Analysis from TCGA

Transcript per million (TPM) values of selected oncofetal signatures were extracted from The Cancer Genome Atlas – Colon Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD), TCGA-BRCA - Breast Invasive Carcinoma, TCGA-LUAD - Lung Adenocarcinoma, and TCGA-LIHC - Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma datasets. Expression levels between normal and tumor samples were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Significance was set at ***p < 0.0001.

3. Mechanistic Principles of Oncofetal Reprogramming

3.1. Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

In colorectal cancer (CRC), oncofetal reprogramming represents a coordinated form of developmental plasticity in which injury and oncogenic signaling converge to drive fetal-like, stem cell states on adult epithelium. The idea started with damaged tissue: in DSS colitis and 3D organoids, Yui et al. showed that severe injury drives colonic epithelium into a transient fetal-like state. Adult stem and differentiation cell markers are suppressed, fetal genes are induced and collagen I deposited during extracellular matrix remodeling activates integrin α2β1, FAK/Src and nuclear YAP/TAZ [

26]. When crypt-derived organoids are grown in collagen I with WNT, this YAP/TAZ-dependent state is maintained and imprints a transcriptional program marked by Clu, Ly6a/Sca-1, and Tacstd2. Building on this, Ayyaz et al. identified Clu-high Ly6a/Sca-1+ revival stem cells (revSCs) that arise after radiation or Lgr5+ ablation, which depends on YAP1 and regenerates the Lgr5+ compartment [

27]. These observations establish a YAP-high fetal-like reference state that normal tissue can enter during repair and that CRC later co-opts.

Tumors begin capturing these regenerative circuits early. Roulis et al. discovered Ptgs2+ peri-cryptal fibroblasts that constitutively produce PGE2. The stromal PGE2 signal occurs via epithelial PTGER4 to expand a Sca-1+ YAP-dependent reserve-like stem cell compartment, and loss of Ptgs2 in fibroblasts or Yap1 in epithelium sharply reduces tumor initiation [

28]. A second route operates entirely within the epithelium. Jacquemin et al. found that Apc-mutant tumoroids secrete THBS1, which induces nuclear YAP and expression of a regenerative program in neighboring wild-type organoids. This confers WNT-independent hyperproliferative growth and mirrors the fetal-like YAP states observed in colitis and collagen cultures [

29]. Together, the PGE₂-PTGER4-YAP and THBS1-YAP loops show how both stromal prostaglandins and epithelial matricellular ligands ignite fetal-like programs during the earliest stages of neoplasia. Once activated, these transient regenerative states can be stabilized by oncogenic and TGF-β signaling. Han et al. demonstrated that KRASG12D or BRAFV600E combined with TP53 and SMAD4 loss, followed by a brief TGF-β pulse, drives a YAP/TAZ-dependent “embryonic intestinal” identity that persists independently of canonical WNT. In this state, YAP/TAZ effectively replaces β-catenin/TCF as the main growth module [

30]. In parallel, Cheung et al. showed that disrupting Hippo signaling through LATS1/2 or MST1/2 loss, or YAP overexpression, reprograms Lgr5+ stem cells into a regenerative-like, low-WNT state with altered differentiation and metastatic potential [

31]. These findings position the YAP/Hippo pathway as a switch between adult Lgr5+ identity and an oncofetal-like state.

As tumors develop, these fetal-like programs no longer appear binary, but instead form a continuum of cancer stem cell (CSC) states. Vazquez et al. mapped a spectrum from LGR5+ CBC-like CSCs to LGR5- regenerative CSCs (RSC-CSCs) enriched for CLU, ANXA1, Ly6a/Sca-1, and Tacstd2/TACSTD2. They also showed that tumors with high plasticity shift toward this fetal-like RSC compartment under neoadjuvant FOLFOX treatment and respond poorly in FOxTROT therapy [

32]. Qin et al. clarified how upstream pathways steer cells along this spectrum. Using a multiplexed single-cell perturbation atlas, they found that fibroblast-derived WNT3A and TGF-β, combined with low MAPK and PI3K activity, induce a Clu+ revival CSC (revCSC) state that depends strictly on epithelial YAP. When APC loss is coupled to KRASG12D and high MAPK/PI3K activity, however, cells are driven instead into an LRIG1+/BIRC5+ proCSC attractor that is hyperproliferative and comparatively stromal-independent [

33]. In vivo, Paneth-cell models reveal a similar logic: differentiated Paneth cells can dedifferentiate through a Clu+ YAP1-high revival intermediate under inflammation and Apc/Kras/Tp53 mutations, placing this YAP-driven oncofetal-like state at the center of colitis-associated CRC initiation [

34].

Chromatin-level work shows how these states gain molecular stability. Kobayashi et al. profiled “collagen spheres” - organoids grown on collagen I to mimic stiff, inflamed ECM. Collagen I engagement of integrin α2β1 and FAK/Src induced nuclear YAP/TAZ, upregulated Wwtr1 (TAZ) and Tead4 and activated a fetal-like inflammatory program including Ly6a, Clu, Tacstd2, Krt80, Fn1, Il33 and Ptgs2. ATAC-seq revealed extensive enhancer opening enriched for TEAD and AP-1 motifs, coinciding with strong induction of FOSL1 (Fra-1) and RUNX2 [

35]. Enhancer-regulated transcription by AP/TAZ, TEAD, AP-1 and RUNX provides a molecular scaffold for maintaining oncofetal identity. Metastatic studies further highlight how essential this plasticity is for colonization. Heinz et al. combined intravital liver imaging with patient-derived CRC organoids and single-cell transcriptomics. Early micro-metastases, initially depleted of LGR5+ markers, require a transient burst of YAP activity to survive and begin expansion. If YAP remains too high, lesions fail to grow; if YAP cannot be induced, colonization collapses [

36]. Moorman et al. extended this view by analyzing matched normal colon, primary CRC and metastases. Primary tumors are dominated by LGR5+ intestinal stem-like states, while metastases pass through a conserved fetal-like, progenitor state that later branches into squamous and neuroendocrine-like lineages. Chemotherapy expands this fetal progenitor pool and increases non-canonical differentiation states, both correlating with poor survival [

37].

The mechanistic depth of study increases even further with Mzoughi et al., who describe a primitive oncofetal stem state (OnF) that emerges immediately after Apc loss. Using Apc -mutant mouse models, human CRC organoids, lineage tracing, and single-cell multi-omics, they show that loss of RXR activity in mature LGR5+ cells initiates an epigenetic circuit that YAP and AP-1 can then activate. Together, these factors remodel enhancers, activate a fetal-like OnF program, and generate highly plastic, lineage-infidel cells [

9]. OnF and LGR5+ CSCs coexist but differ sharply in therapy response. LGR5+ cells remain FOLFIRI-sensitive, whereas OnF cells are intrinsically drug tolerant. Chemotherapy can even drive LGR5+ cells into the OnF state, and AP-1 hyperactivation pushes cells beyond OnF into even more dysregulated configurations. Loss of RXR control leaves a lasting “OnF memory” in chromatin structure [

9].

Across these systems, a coherent set of oncofetal signatures: revSC, revCSC, RSC-CSC, collagen-induced fetal programs, conserved fetal progenitors in metastases and RXR-gated OnF states, stratifies tumors by plasticity and differentiation state. They track consistently with chemotherapy resistance and metastatic potential. Moreover, they point to various therapeutic opportunities, which include YAP/TAZ-TEAD or AP-1 complex inhibition, RXR ligand use to erase OnF memory, COX-2/PGE2/PTGER4 or THBS1-YAP loop blocking, targeting integrin-FAK/Src mechanotransduction to impede collagen-induced inflammation-fetal programs, and timing of YAP-directed interventions at micro-metastasis. The details are provided in [

9,

27,

28,

29,

32,

35,

36,

37]. Finally,

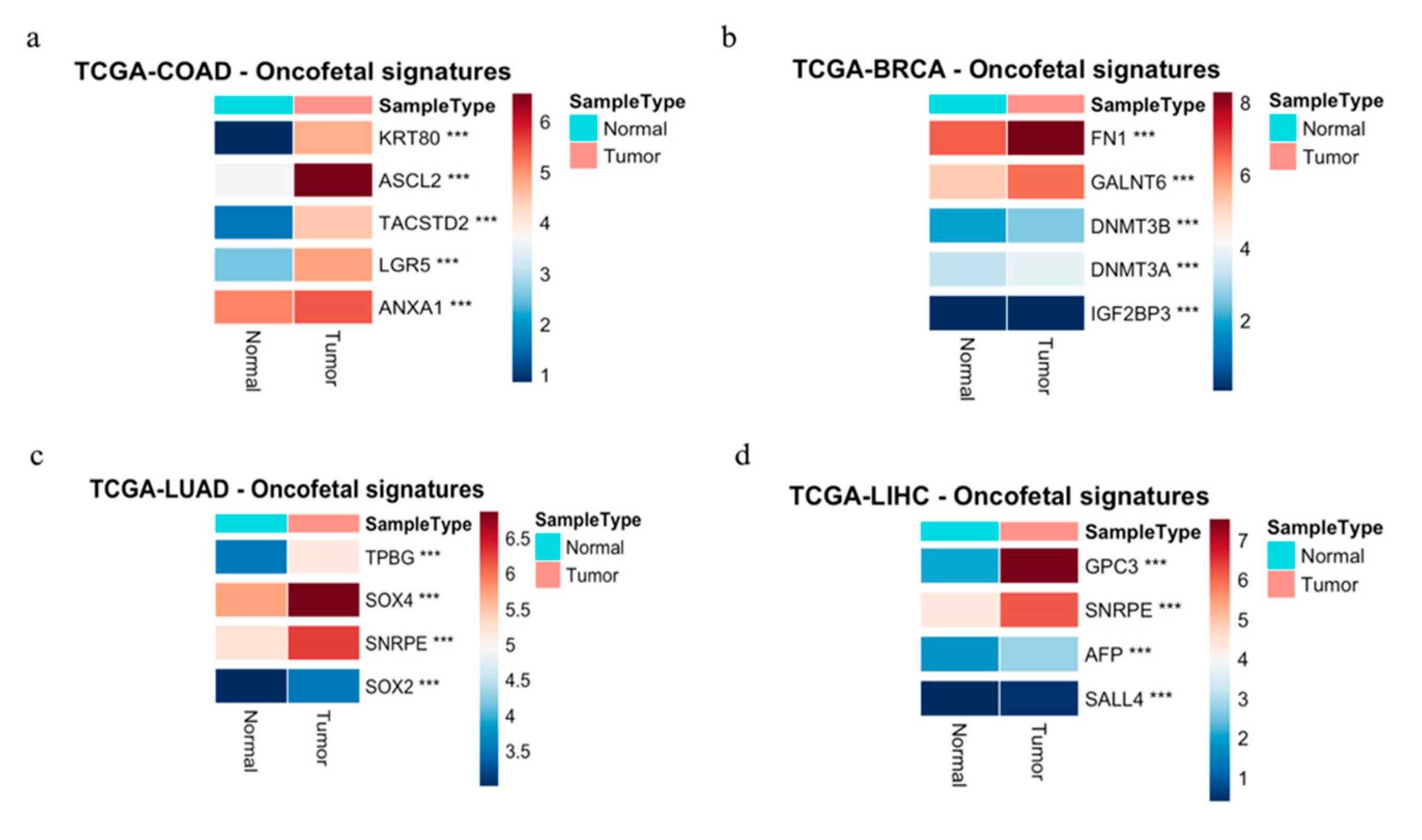

Figure 2a illustrates profound oncofetal signatures in CRC.

In summary, investigation into CRC is revealing critical information on the mechanisms that underly oncofetal reprogramming, particularly identification of YAP1 and AP-1 as central transcriptional drivers of this reprogramming process. Below we discuss and compare CRC’s mechanistically-mapped oncofetal circuit in relation to other cancer types.

3.2. Breast Cancer

In breast cancer, evidence of oncofetal reprogramming is more scattered than in CRC, but the different strands of evidence converge on a common idea. Aggressive tumors often revive fetal or embryonic mammary programs at transcriptomic, regulatory, and microenvironmental levels [

38,

39,

40]. Basal-like, triple-negative, and some HER2-enriched subtypes show propensity for occupation of transcriptional states that are reminiscent of fetal mammary epithelium [

41,

42]. These tumors re-express oncofetal regulators and reshape their niche to harbor extracellular matrix and glycan features normally seen only during development.

Comparative transcriptomics gives one of the clearest windows into these developmental trajectories. Spike et al. purified fetal mammary stem cells from late mouse embryogenesis and showed them to represent a self-renewing, multipotent population that co-expresses luminal and basal markers. Their fetal stem cell and surrounding stroma are closely similar to human basal-like and HER2-enriched tumors and enriched for ErbB and FGF signaling [

43]. Zvelebil et al. extended this view by profiling mid-gestation mammary bud epithelium. They defined an embryonic mammary signature marked by ER-negative and PR-negative status with co-expression of KRT5, KRT14 and p63. This resembles basal-like and triple-negative disease, and elements such as BCL11A and SOX11 are activated in Brca1-null mouse tumors and human basal-like and HER2+ cancers. High SOX11 also predicts poor survival [

44]. Clinical relevance of these developmental signatures was also demonstrated. Pfefferle et al. integrated mammary cell datasets to generate luminal progenitor, basal stem cell, and fetal MaSC signatures. When applied to large neoadjuvant chemotherapy cohorts, fetal and progenitor-like signatures strongly predicted pathological complete response to anthracyclines and taxanes across intrinsic subtypes [

45]. Additional work identified a 323 gene adult mammary stem-cell signature enriched for motility and morphogenesis functions. This signature separates triple-negative tumors into high and low risk groups, with high activity marking rapidly metastasizing cancers [

46]. Single cell sequencing further revealed a gestational stem cell population normally restricted to pregnancy and early development. Its markers appear at high levels in basal-like and triple-negative tumors, aligning with cancer stem-like compartments [

47].

The understanding becomes deeper when examining specific regulators. The long non-coding RNA H19 stands out as a prototypical oncofetal factor [

48]. It is abundant during fetal life, silenced in most adult tissues, and re-expressed in many carcinomas, often in tumor stroma. Gain and loss experiments show that H19 promotes proliferation, while its repression reduces growth [

48]. Matouk et al. demonstrated that TGF-beta and hypoxia induce H19 and miR675 along with Slug. This creates a PI3K and AKT dependent loop in which Slug depends on H19, Slug boosts H19 promoter activity and H19, and miR675 suppress E-cadherin. The result is a reinforcing EMT-type circuit that promotes invasion, metastasis, and multidrug resistance [

48]. Regulation also occurs post-transcriptionally. IGF2BP1, also known as IMP1, is widely expressed during embryogenesis, but silenced in most adult epithelia. It is re-expressed in aggressive breast cancers and binds E2F transcription factor mRNAs, stabilizing them and amplifying E2F driven cell-cycle programs. Pharmacologic inhibition of IGF2BP1 RNA binding reduces E2F signatures, lengthens G1 phase and suppresses tumor growth in vivo [

49,

50]. A broader catalog of oncofetal regulators includes OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, MYC, SALL4, FOXM1 and pathways such as Wnt and beta-catenin, Hedgehog, Notch, TGF beta and Hippo. These factors normally act in embryonic development but re-emerge in cancer stem-like subpopulations [

51]. In breast cancer, many of these regulators, along with CRIPTO and selected HOX proteins, appear in small but highly tumorigenic compartments capable of extensive plasticity [

52,

53,

54].

This developmental reawakening is mirrored in the tumor microenvironment. Early work on fibronectin identified oncofetal isoforms recognized by FDC-6 and BC-1. These isoforms are found in fetal tissue, placenta and tumors, but are absent from adult tissues and plasma fibronectin [

55,

56]. In a study of 171 breast specimens, Kaczmarek et al. showed that while all normal and hyperplastic tissues expressed fibronectin, none expressed the oncofetal isoforms detected by FDC-6 or BC-1. In contrast, 93 percent of invasive ductal carcinomas and 99 percent of invasive lobular carcinomas stained positive, often with strong stromal and vascular localization [

55,

57]. This indicates that invasive breast cancers reconstruct a fibronectin environment similar to that found in fetal tissues, which likely influences integrin engagement, tissue stiffness, growth factor presentation, and mechanotransduction.

Glycosylation adds yet another developmental layer. The Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen is a classic oncofetal carbohydrate epitope that is usually masked in adult tissues. In breast cancer, hypo-glycosylation of MUC1 exposes the TF core. Experiments show that TF high MCF 7 cells, but not TF low T 47D cells, undergo strong growth inhibition and apoptosis when exposed to galectin 1 [

58]. Several oncofetal or trophoblast-like antigens are now being explored as therapeutic targets. The trophoblast glycoprotein 5T4 is minimally expressed in normal adult tissues but strongly expressed in many carcinomas. An antibody drug conjugate targeting 5T4, called A1mcMMAF, produces durable tumor regressions and complete responses in xenograft models driven by 5T4 positive tumor-initiating cells [

59]. Another candidate, MIG 7, is expressed in fetal cytotrophoblasts and various carcinomas but absent from normal adult tissues. A monoclonal antibody against an N terminal MIG 7 peptide selectively recognizes MIG 7 on cancer cells and inhibits MCF 7 growth in vitro [

60] Additional targets include OFA iLRP and HOX transcription factors such as HOXB3, HOXB4, and HOXC6, which are rarely expressed in adult tissue but strongly reactivated in breast carcinoma [

61,

62].

Taken together, these various lines of evidence define a multi-layer oncofetal program in breast cancer. Tumors often adopt fetal or embryonic mammary expression states with clear prognostic and predictive significance [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. They re-express fetal regulators such as H19, IGF2BP1, CRIPTO and selected HOX factors promoting EMT, proliferation, stemness and stress tolerance [

48,

51,

63]. At the same time, they rebuild their niche by means of oncofetal ECM, TF glycans and trophoblast-like antigens [

55,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Some oncofetal signatures in breast cancer are illustrated in

Figure 2b.

3.3. Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

Oncofetal reprogramming in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) refers to the re-emergence of embryonic developmental pathways and antigens that are typically expressed during fetal development in lung but are often silenced in adult tissues. In lung cancer, very similar to CRC, oncofetal reprogramming represents a coordinated form of developmental plasticity in which injury, oncogenic signaling, and stromal cues converge to impose fetal-like stem cell states on adult epithelium. This idea stems from tissue damage and regeneration. Laughney et al. utilizing single cell analysis of 40,505 cells from adjacent non-tumor involved lung, primary lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and three LUAD metastasis from three separate sites. These cells were used to create a global cell atlas of twenty different cell types. Within their analysis of primary tumor cells, they identified two progenitor cell types implicated in the regeneration of severely injured lungs. Interestingly, they found that metastatic cells revert to a more embryonic-like state with enrichment of SOX2 and SOX9 which are responsible for the re-emergence of these developmental pathways [

64]. Early work by Hassan et al. found a similar result using microarray gene set analysis to examine gene expression data for 443 lung adenocarcinoma and 130 squamous cell lung cancers for expression changes in embryonic stem cell profile genes. The embryonic gene set was previously identified by Ben-Porath et al and includes embryonic stem cell genes, Polycomb targets, Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 targets and Myc targets [

65]. In lung adenocarcinoma, they found that enrichment of these gene sets correlated with poorly differentiated tumors and worse overall survival. This finding did not apply to squamous cell lung cancer highlighting the heterogeneity of lung cancer types [

66]. Recent work in early-stage NSCLC by Wang et al performed comprehensive profiling of paired tumors (n = 122) from stage I NSCLC patients they found that PRAME, a well-known cancer testis antigen that is an established oncofetal driver, was the most significantly upregulated in recurrent LUAD and was hypomethylated, they propose this antigen as a possible immunotherapy target [

67].

Specific drivers of oncofetal reprogramming have also been examined in NSCLC. As noted above, YAP is one of the pivotal drivers of oncofetal reprogramming. Similar to other cancers, YAP1 overexpression correlated with worse prognosis in NSCLC patients and was found to drive proliferation and invasion in NSCLC [

68]. A well-established oncofetal antigen 5T4 is typically expressed only during embryonic development. Damelin et al showed that 5T4 is associated with worse clinical outcomes and expressed in a tumor-initiating, sub-population of cells [

69,

70]. Similarly, the oncofetal chondrotin sulfate, modification on cell surface proteoglycans was highly expressed in NSCLC, but absent in adult normal tissue. Across four cohorts of early-stage NSCLC patients high oncofetal chondrotin sulfate was linked to worse overall survival [

8].

Non-coding RNAs have been implicated in oncofetal reprogramming including lncRNA H19 which is highly expressed during embryonic development and is downregulated in adults. Several studies have shown that lncRNA H19 is increased in both serum levels and expression and associated with worse prognosis in NSCLC patients [

71]. Small RNA-Sequencing of 25 human fetal lungs, adult non-malignant lung, and LUAD identified 13 miRNAs with oncofetal expression expression and 3 of the 13 were linked to shorter overall survival [

72]. Interestingly, the oncofetal RBP IGF2BP3was found by Fujiwara et al to directly promote Drosha cleavage and selectively regulate the production of miRNA isoforms. Subsequently, miRNA isoforms alter the seed sequence and targeting of the miRNome leading to a cancer-specific regulatory network that is linked to recurrence risk [

73]. Another class of small non-coding regulatory RNA that has been implicated in oncofetal reprogramming is PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNAs). Michelle et al analyzed piRNA profiles in fetal lung, adjacent normal LUAD, and LUSC. They identified 37 oncofetal piRNAs in LUAD and 46 in LUSC. They identified an 8-piRNA signature that could stratify signatures that predicts poor outcomes [

74].

Additionally, the tumor microenvironment has been implicated in oncofetal reprogramming in NSCLC. Early work by Schor et al. found that in NSCLC a truncated isoform of migration-stimulating factor (MSF), normally only found in fetal tissues, is re-expressed in cancers and secreted by tumor-associated stromal cells and that promotes tumor progression [

75]. A recent single cell analysis was performed on 900,000 cells from 25 treatment naive patients with lung cancer [

76]. Their analysis saw that tumor-associated macrophages had a transcriptional signature similar to fetal lung development in STAB1+ TAMs and showed an increase in gene expression that promotes iron release into the environment [

76]. Finally, some notable oncofetal signatures in NSCLC are illustrated in

Figure 2c.

3.4. Liver Cancer (HCC)

Since the early 1960s, there has been a growing body of research in HCC implicating oncofetal reprogramming as a driver of tumorigenesis. One of the earliest discoveries was the fetal antigen α- Fetoprotein (AFP) that is expressed by the liver and yolk sac during fetal development and re-expressed during HCC [

77]. Serum AFP remain one of the most commonly used diagnostic and screening methods in HCC [

77] and a comprehensive review of AFP is provided elsewhere [

78]. Notably, high expression of AFP has been associated with increased expression of YAP1, the well-known developmental master regulator discussed above [

79]. In the liver, YAP1 has been shown to reactivate embryonic enhancers and drives de-differentiation and proliferation [

80]. Biagioni et al identified a YAP target gene signature and used it to classify liver cancer, finding that it correlated with poor prognosis [

80]. Consistently, multiple clinical investigations have reported that YAP1 overexpression is common in HCC and associated with poor outcomes [

77,

79]. YAP1 expression also correlates with other oncofetal and stemness markers, including NANOG and OCT3/4 as well as CD133 in HCC [

81]. Also, its overexpression has been implicated in increased proliferation, enhanced EMT, organ size, and tumor progression [

77,

82,

83]. In a murine model of acute liver failure, Hyun et al found reactivation of YAP1 and other fetal markers, and an increase in fetal-like hepatocytes [

84]. Highlighting its relevance, Fitamant et al. found that inhibiting YAP restores hepatocyte differentiation ability and induces tumor regression [

85]. Recent detailed reviews of YAP1 in HCC can be found here [

77,

86].

A key YAP1 target gene is Glypican-3 (GPC3) and its expression is positively correlated with YAP1. GPC3 is normally detected in the fetal liver and is re-expressed in HCC, making it an attractive potential biomarker candidate. Several studies have shown that GPC3 expression is associated with worse overall survival, larger tumor size, and increased metastasis. A recent review of GPC3 in HCC can be found here [

87].

Another well-known oncofetal marker LIN-28B, is an RNA-binding protein (RBP) whose overexpression increases the expression of oncofetal stemness markers OCT4, SOX2 and NANOG [

88]. More recently, LIN28B was shown to participate and drive the formation of a oncofetal regulatory network with 15 other RBPS that collectively drive HCC tumor initiation [

14]. In patients with HCC, elevated serum LIN28B levels are associated with higher tumor grade, larger tumor size, and early recurrence [

88]. Recent single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) and bulk RNA-sequencing of fetal liver, normal liver, and liver tumors has further delineated oncofetal transcriptional programs in liver cancer. These findings underscore the central role RBPs in oncofetal reprogramming. In particular this work identified a high presence of RBPs, such as TRIM71, which they proposed to act as a driver for oncofetal reprogramming [

5].

Other studies focused on the transcription factor Splat-like protein 4 (SALL4) that is involved in embryonic development and is particularly important for stem cell function [

1]. Unlike GPC3 and AF, SALL4 is not highly expressed in regenerating liver tissue, but is elevated in patients with HCC making it a potentially more sensitive biomarker candidate [

78]. SALL4 is associated with poor prognosis and is considered to be a promising therapeutic target currently under clinical development [

78,

89,

90,

91].

Additionally, non-coding RNAs have been implicated in oncofetal reprogramming including lncRNA H19 which is highly expressed during embryonic development. In particular, lncRNA H19 is upregulated in the fetal liver, and is downregulated in adults [

92,

93]. Although increased in HCC, lncRNA H19’s oncogenic role is controversial (reviewed in [

92]). Another long non-coding RNA implicated in oncofetal reprogramming in HCC is lncRNA PVT1 whose expression is associated with AFP and poor prognosis [

94].

Oncofetal reprogramming has also been implicated in changes in the tumor microenvironment including the re-emergence of fetal-associated endothelial cells (PLVAP/VEGFR2) and fetal-like (FOLR2) tumor-associated macrophages [

95]. The re-emergence of these cellular populations is believed to contribute to the immunosuppressive features of the fetal liver. The information on these findings is reviewed here [

1,

7]. For comparison, some oncofetal signatures in liver cancer are illustrated in

Figure 2d.

Heatmaps illustrating the differential expression of selected onco-fetal genes between tumor and adjacent normal tissues in four specific cancer types from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohorts. Expression values were calculated as log2(TPM+1) (Transcripts Per Million), followed by mean normalization to highlight the differences. Color intensity corresponds to the log2(TPM+1) expression level, as indicated by the scale bars adjacent to each heatmap. Statistical significance: Differentially expressed genes were identified using a Student’s t-test. *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.0001

TCGA-COAD - Colon Adenocarcinoma

Heatmap showing the expression levels of five onco-fetal signature genes in Colon Adenocarcinoma. Genes like KRT80, LGR5, and ANXA1 show significant upregulation in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue (P < 0.0001).

TCGA-BRCA - Breast Invasive Carcinoma

Heatmap showing the expression levels of five onco-fetal signature genes in Breast Invasive Carcinoma. Genes like FN1, GALNT6, DNMT3B, and DNMT3A show significant upregulation in tumor tissue, while IGF2BP3 shows significant downregulation in tumor tissue (P < 0.0001).

TCGA-LUAD - Lung Adenocarcinoma

Heatmap showing the expression levels of five onco-fetal signature genes in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Genes like TPBG and SNRP E are significantly upregulated, while SOX4 and SOX2 are significantly downregulated in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue (P < 0.0001).

TCGA-LIHC - Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Heatmap showing the expression levels of four onco-fetal signature genes in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Genes such as GPC3, SNRP E, AFP, and SALL4 all demonstrate significant upregulation in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue (P < 0.0001).

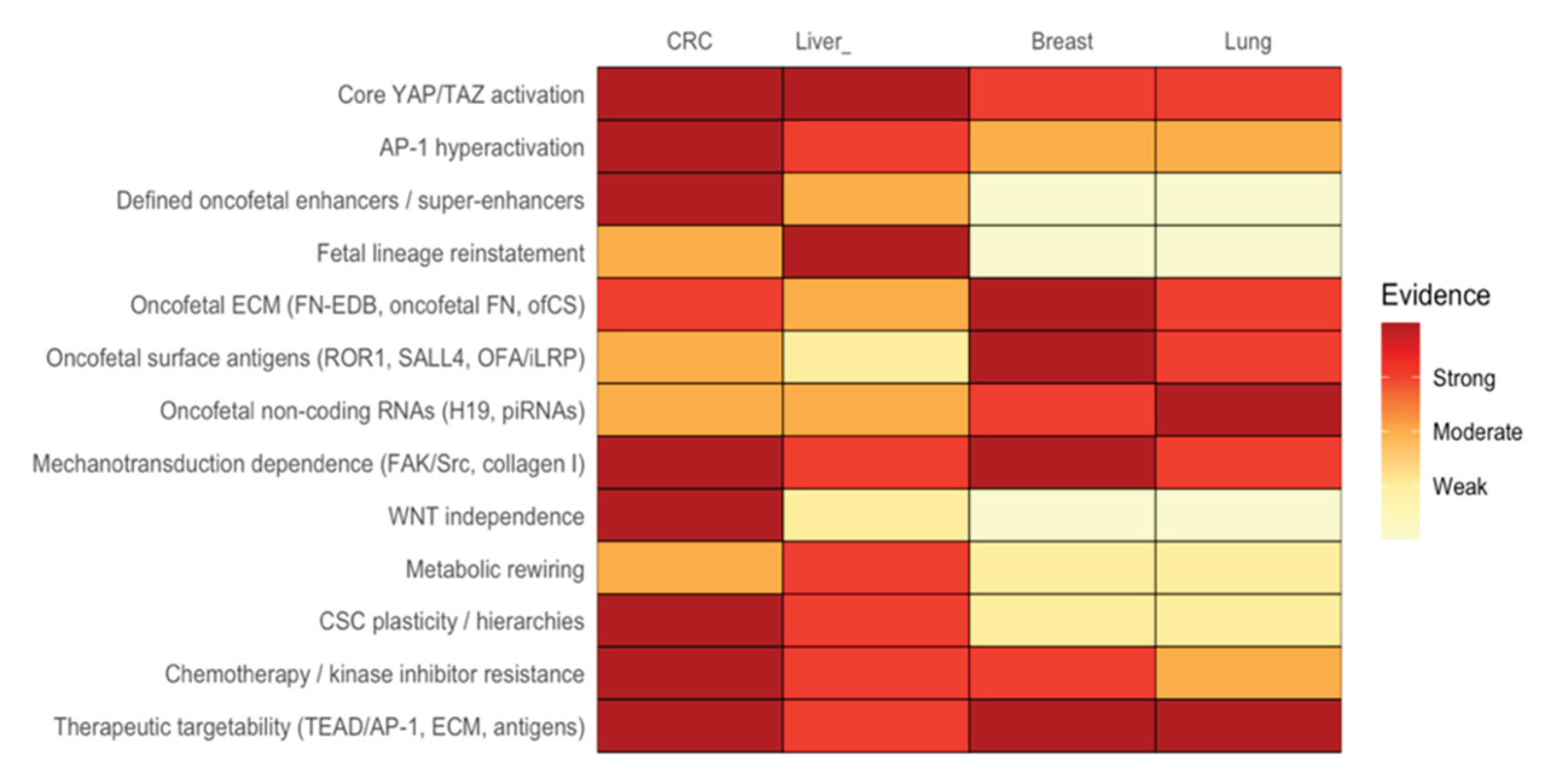

4. Comparison of Shared vs. Distinct Drivers

Oncofetal reprogramming has recently crystallized into a unifying principle of malignant plasticity, that is one in which adult tumors regain access to developmental states normally restricted to embryogenesis. Across colorectal, liver, breast, and lung cancers, diverse oncogenic, mechanical, and inflammatory cues converge on a conserved mechanotransductive axis centered on integrin-FAK/Src signaling, Hippo pathway attenuation, and activation of YAP/TAZ together with AP-1. Within stiff, collagen- and oncofetal fibronectin–rich matrices, these transcriptional co-activators reactivate fetal enhancers and generate stable attractor states that support lineage infidelity, regenerative stemness, and broad therapy resistance [

26,

35,

96]. Although this shared architecture is conserved across tissue types, each organ superimposes its own developmental memory, producing distinct oncofetal identities. The oncofetal signatures across cancers have been combined and presented in

Table 1.

The oncofetal reprogramming has been most explored in CRC, where fetal-like CLU⁺ “revival stem cells” first found in injury [

27] reappear in tumorigenesis and align with a continuum between canonical LGR5⁺ stem cells and fetal-like regenerative CSC states (OnFS) [

27]. The discovery of the YAP/TAZ-TEAD/AP-1 - driven OnF and OnFS states revealed a complete oncofetal enhancer architecture: APC-loss-induced RXR deregulation unlocks fetal super-enhancers, AP-1 hyperactivation consolidates lineage infidelity, and YAP/TAZ maintains WNT-independent growth and chemoresistant plasticity [

9]. CRC therefore represents the most mechanistically complete oncofetal circuit mapped to date. Although relying on the same YAP/TAZ-AP-1 engine, liver cancers uniquely integrate hepatoblast transcription factors. SALL4, LIN28B, TRIM71, and HLF reinstate developmental programs that drive progenitor-like phenotypes, metabolic rewiring, and kinase-inhibitor response [

5,

88,

89,

101] Moreover, the YAP1-SALL4-BMI1 axis directly governs hepatocyte-cholangiocyte fate decisions [

12], illustrating how liver tumors embed oncofetal reprogramming in lineage bifurcation rather than solely in plasticity.

In contrast, breast and lung cancers exhibit oncofetal reprogramming most prominently through surface antigens, non-coding RNAs, and ECM glycoforms rather than fully delineated transcriptional reversion. In breast cancer, embryonic RTKs such as ROR1, fetal lncRNAs such as H19/miR-675, and abundant ED-B and O-glycosylated fibronectin variants collectively drive EMT-like behavior, metastasis, and multidrug resistance [

48,

102,

103]. These patterns clearly implicate integrin–FAK/Src–YAP/TAZ signaling, but investigation on the full fetal mammary reference atlas analogous to CRC and liver remains underdeveloped. Lung cancers similarly exhibit a strong antigenic and ECM-driven oncofetal phenotype. NSCLCs express oncofetal fibronectin and SALL4 that regulate motility, Src/FAK activation, and patient prognosis [

74,

96,

103,

104,

105]. Given YAP1’s essential role in fetal lung progenitors and repair [

106], these antigenic profiles likely reflect deeper enhancer-level oncofetal reprogramming.

Together, these observations define oncofetal reprogramming as a pan-cancer developmental hijack driven by mechanics, inflammation, and YAP/TAZ-AP-1 enhancer logic. The combined mechanisms along with the amount of evidence across CRC, breast cancer, NSCLC, and liver cancer is illustrated in

Figure 3. What differentiates the various tumor types from each other is not whether they reactivate fetal states, but which fetal modules they reinstate, such as enhancer-level lineage disassembly in CRC; hepatoblast TF reinstatement in liver; antigenic and ECM remodeling in breast and lung. The resulting states confer plasticity, WNT independence, metabolic flexibility, immune modulation, resistance to chemotherapy, and kinase inhibitor responses. Constructing “oncofetal profiles” that systematically integrate key features, including YAP/TAZ and AP-1 activity, fetal lineage resemblance, antigenic/ECM expression, stromal cues, and metabolic identity, offers a novel way to compare tumors. This approach could also uncover shared therapeutic vulnerabilities, including TEAD/AP-1 inhibitors, integrin-FAK blockade, COX2/PTGER4 inhibition, and oncofetal antigen–directed CAR-T or ADC approaches. In summary, advancing our understanding of oncofetal reprogramming and its transcriptional drivers, especially YAP1 and AP-1, represents a frontier in cancer biology with direct translational relevance.

Summary of the evidence for onco-fetal gene signatures and related hallmarks) in four major cancer types: Colorectal Cancer (CRC), Liver Cancer (Liver), Breast Cancer (Breast), and Lung Cancer (Lung).

5. Conclusion

The Goal of this review on oncofetal reprogramming was to: i) Comprehensively examine its multifaceted nature, ii) Elucidate its underlying molecular mechanisms, and iii) Evaluate its consequences on anti-tumor therapeutic response. Based on our investigation of different cancer types, it is becoming increasing clear that reactivation of embryonic and fetal gene expression programs is occurring during tumor development. Indeed, among colorectal, liver, breast, and lung cancers, diverse oncogenic, mechanical, and inflammatory cues disclose a conserved mechanotransductive axis. Specifically, this axis is centered on integrin–FAK/Src signaling, Hippo pathway attenuation, and activation of YAP/TAZ with AP-1 that provides mechanisms for the molecular etiology of oncofetal reprogramming. Among the candidates, YAP1 and AP-1 have emerged as central transcriptional drivers of this reprogramming process, especially in colorectal and breast cancers. To evaluate the consequences of oncofetal reprogramming on anti-tumor therapeutic response, we explored distinct expression patterns of oncofetal genes across various tumor types. This analysis also determined how these patterns correlate with treatment outcomes and patient survival. To overcome the oncofetal mechanisms driving therapeutic resistance and tumor relapse rates, we propose a novel dual-targeting therapeutic strategy that simultaneously targets both cancer stem cells and oncofetal-reprogrammed populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.N. and M.L.; Methodology, A.L.N. and M.L.; Software, A.L.N.; Validation, A.L.N., M.L. and B.M.B.; Formal Analysis, A.L.N., M.L. and B.M.B.; Investigation, A.L.N., M.L. and B.M.B.; Resources, A.L.N. and M.L; Data Curation, A.L.N. and M.L.; Writing - Original Draft Preparation, A.L.N and M.L.; Writing-Review and Editing, A.L.N., M.L and B.M.B.; Visualization, A.L.N., M.L.; Supervision, B.M.B.; Project Administration, B.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by generous support from The Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation (2024; BMB), The Cawley Center for Translational Cancer Research Fund (2024, BMB, ML, AN), The Carpenter Foundation (2024, BMB), University of Delaware Department of Biological Sciences (2025; ML, AN) and INBRE NIH/NIGMS GM103446 (BMB).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. The results published here are partly based upon data generated by the The Cancer Genome Atalas (TCGA) Research Network:

https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nicholas Petrelli for his support at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and Research Institute as well as Dr. Lynn Opdenaker for their helpful discussions.”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| YAP1 |

Yes Associated Protein 1 |

| AP-1 |

Activator Protein 1 |

| CSC |

cancer stem cell |

| CRC |

colorectal cancer |

| EMT |

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| revSCs |

revival stem cells |

| NSCLC |

non-small cell lung cancer |

| HCC |

hepatocellular carcinoma |

| AFP |

α- Fetoprotein |

| GPC3 |

Glypican-3 |

| RBP |

RNA-binding protein |

| LUAD |

lung adenocarcinoma |

| MSF |

migration-stimulating factor |

| piRNAs |

PIWI-interacting RNA |

| TPM |

Transcript per million |

| KM |

Kaplan-Meier |

References

- Sharma; Blériot, C.; Currenti, J.; Ginhoux, F. Oncofetal reprogramming in tumour development and progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22(10), 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S. K.; et al. Bivalent Epigenetic Control of Oncofetal Gene Expression in Cancer. Mol Cell Biol 2017, 37(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. F.; et al. Genome-wide screening identifies oncofetal lncRNA Ptn-dt promoting the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating the Ptn receptor. Oncogene 2019, 38(18), 3428–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, R. C.; Bouma, G. J.; Winger, Q. A. Shifting perspectives from ‘oncogenic’ to oncofetal proteins; How these factors drive placental development. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2018, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; et al. Oncofetal TRIM71 drives liver cancer carcinogenesis through remodeling CEBPA-mediated serine/glycine metabolism. Theranostics 2024, 14(13), 4948–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; et al. Oncofetal reprogramming in tumor development and progression: novel insights into cancer therapy; John Wiley and Sons Inc, 01 Dec 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currenti, J.; Mishra, A.; Wallace, M.; George, J.; Sharma, A. Immunosuppressive mechanisms of oncofetal reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment: implications in immunotherapy response; Portland Press Ltd, 01 Apr 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, H. Z.; et al. Oncofetal chondroitin sulfate is a highly expressed therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzoughi, S.; et al. Oncofetal reprogramming drives phenotypic plasticity in WNT-dependent colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 2025, 57(2), 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang; et al. Advancements and applications of single-cell multi-omics techniques in cancer research: Unveiling heterogeneity and paving the way for precision therapeutics; Elsevier B.V, 01 Mar 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wang, Y.; Luan, M.; Zhang, Y. Multi-omics and single-cell approaches reveal molecular subtypes and key cell interactions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; et al. SALL4 Is Required for YAP1-Dependent Malignant and Regenerative Hepatocyte-to-Cholangiocyte Reprogramming. Cancer research communications 2025, 5(9), 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; et al. NOTCH-YAP1/TEAD-DNMT1 Axis Drives Hepatocyte Reprogramming Into Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2022, 163(2), 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M. H.; et al. Liver cancer initiation requires translational activation by an oncofetal regulon involving LIN28 proteins. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2024, 134(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, F.; et al. YAP-driven malignant reprogramming of oral epithelial stem cells at single cell resolution. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott; et al. The IGF2BP1 oncogene is a druggable m6A-dependent enhancer of YAP1-driven gene expression in ovarian cancer. NAR Cancer 2025, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; et al. Targeting the Hippo/YAP Pathway: A Promising Approach for Cancer Therapy and Beyond; John Wiley and Sons Inc, 01 Sep 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, K. I.; et al. The Hippo pathway effector YAP is a critical regulator of skeletal muscle fibre size. Nat Commun 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Nicoll, M.; Ingham, R. J. AP-1 family transcription factors: a diverse family of proteins that regulate varied cellular activities in classical hodgkin lymphoma and ALK+ ALCL; BioMed Central Ltd, 01 Dec 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Pratt, H.; Gao, M.; Wei, F.; Weng, Z.; Struhl, K. YAP and TAZ are transcriptional co-activators of AP-1 proteins and STAT3 during breast cellular transformation. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo; et al. Integrative epigenetic analysis reveals AP-1 promotes activation of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells in HCC. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2023, 80(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulzewsky, F.; Holland, E. C.; Vasioukhin, V. YAP1 and its fusion proteins in cancer initiation, progression and therapeutic resistance. Dev Biol 2021, 475, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, T. C.; et al. YAP1 and WWTR1 expression inversely correlates with neuroendocrine markers in Merkel cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2023, 133(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion: the interplay in the tumor microenvironment; BioMed Central Ltd, 01 Dec 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pai, R.; Gupta, S.; Currenti, J.; Gui, W.; Di Bartolomeo, A. Presence of onco-fetal neighborhoods in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with relapse and response to immunotherapy. Nat Cancer 2024, 5(1), 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yui, S.; et al. YAP/TAZ-Dependent Reprogramming of Colonic Epithelium Links ECM Remodeling to Tissue Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22(1), 35–49.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyaz; et al. Single-cell transcriptomes of the regenerating intestine reveal a revival stem cell. Nature 2019, 569(7754), 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulis, M.; et al. Paracrine orchestration of intestinal tumorigenesis by a mesenchymal niche. Nature 2020, 580(7804), 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, G.; et al. Paracrine signalling between intestinal epithelial and tumour cells induces a regenerative programme. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; et al. Lineage reversion drives wnt independence in intestinal cancer. Cancer Discov 2020, 10(10), 1590–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, P.; et al. Regenerative Reprogramming of the Intestinal Stem Cell State via Hippo Signaling Suppresses Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27(4), 590–604.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, E. G.; et al. Dynamic and adaptive cancer stem cell population admixture in colorectal neoplasia. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29(8), 1213–1228.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Cardoso Rodriguez, F.; Sufi, J.; Vlckova, P.; Claus, J.; Tape, C. J. An oncogenic phenoscape of colonic stem cell polarization. Cell 2023, 186(25), 5554–5568.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, M. P.; et al. Non-stem cell lineages as an alternative origin of intestinal tumorigenesis in the context of inflammation. Nat Genet 2024, 56(7), 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; et al. Collagen type I-mediated mechanotransduction controls epithelial cell fate conversion during intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Regen 2022, 42(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M. C.; et al. Liver Colonization by Colorectal Cancer Metastases Requires YAP-Controlled Plasticity at the Micrometastatic Stage. Cancer Res 2022, 82(10), 1953–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman; et al. Progressive plasticity during colorectal cancer metastasis. Nature 2025, 637(8047), 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobbitt, J. R.; Seachrist, D. D.; Keri, R. A. Chromatin Organization and Transcriptional Programming of Breast Cancer Cell Identity; Endocrine Society, 01 Aug 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, M. D.; et al. Differential chromatin accessibility and transcriptional dynamics define breast cancer subtypes and their lineages. Nat Cancer 2024, 5(11), 1713–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredlund, E.; Staaf, J.; Rantala, J. K.; Kallioniemi, O.; Borg, Å.; Ringnér, M. The gene expression landscape of breast cancer is shaped by tumor protein p53 status and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Breast Cancer Research 2012, 14(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, H. L.; et al. Enhancer transcription reveals subtype-specific gene expression programs controlling breast cancer pathogenesis. Genome Res 2018, 28(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhong, B.; Dong, J.; Hu, X.; Li, L. Super enhancer-driven core transcriptional regulatory circuitry crosstalk with cancer plasticity and patient mortality in triple-negative breast cancer. Front Genet 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spike, T.; Engle, D. D.; Lin, J. C.; Cheung, S. K.; La, J.; Wahl, G. M. A mammary stem cell population identified and characterized in late embryogenesis reveals similarities to human breast cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10(2), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvelebil, M.; et al. Embryonic mammary signature subsets are activated in Brca1-/-and basal-like breast cancers. Breast Cancer Research 2013, 15(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferle, D.; Spike, B. T.; Wahl, G. M.; Perou, C. M. Luminal progenitor and fetal mammary stem cell expression features predict breast tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015, 149(2), 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soady, K. J.; et al. Mouse mammary stem cells express prognostic markers for triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research 2015, 17(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J. R. W.; Soto, U. Newly identified breast luminal progenitor and gestational stem cell populations likely give rise to HER2-overexpressing and basal-like breast cancers. Discover Oncology 2022, 13(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matouk, J.; et al. Oncofetal H19 RNA promotes tumor metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2014, 1843(7), 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cai, H.; Kong, X. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) in cancer; BioMed Central Ltd, 28 Jun 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, M. Elevated insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 1 levels predict a poor prognosis in patients with breast carcinoma using an integrated multi-omics data analysis. Front Genet 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Fang, X.; Li, C.; Lan, P.; Guan, X. Oncofetal proteins and cancer stem cells; Portland Press Ltd, 01 Sep 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, S. A. de B.; Garcia; Castro, J. L.; Costa-Pinto, A. R.; Freitas, R. Roles of the hox proteins in cancer invasion and metastasis; MDPI AG, 01 Jan 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, H.; Afify, S. M.; Hassan, G.; Salomon, D. S.; Seno, M. Cripto-1 as a potential target of cancer stem cells for immunotherapy; MDPI AG, 02 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bessa Garcia, S. A.; Araújo, M.; Pereira, T.; Mouta, J.; Freitas, R. HOX genes function in Breast Cancer development; Elsevier B.V., 01 Apr 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, H.; Hakomori, S.-I. The oncofetal domain of fibronectin defined by monoclonal antibody FDC-6: Its presence in fibronectins from fetal and tumor tissues and its absence in those from normal adult tissues and plasma (hepatoma/COOH-terminal region). 1985. Available online: https://www.pnas.org.

- Guller, S.; et al. Release of oncofetal fibronectin from human placenta. Placenta 2003, 24(8–9), 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek; Castellani, P.; Nicolo, G.; Spina, B.; Allemanni, G.; Zardi, L. Distribution of oncofetal fibronectin isoforms in normal, hyperplastic and neoplastic human breast tissues. Int J Cancer 1994, 59(1), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, P.; Mayer, B.; Wiest, I.; Schulze, S.; Jeschke, U.; Weissenbacher, T. Binding of galectin-1 to breast cancer cells MCF7 induces apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation in vitro in a 2D- and 3D- cell culture model. BMC Cancer 2016, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapra, P.; et al. Long-term tumor regression induced by an antibody-drug conjugate that targets 5T4, an oncofetal antigen expressed on tumor-initiating cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2013, 12(1), 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapaneeyakorn, S.; Chantima, W.; Thepthai, C.; Dharakul, T. Production, characterization, and in vitro effects of a novel monoclonal antibody against Mig-7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 475(2), 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Duan, J.; Da Yang, X. Selection of a novel DNA aptamer against OFA/iLRP for targeted delivery of doxorubicin to AML cells. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatlekar, S.; Fields, J. Z.; Boman, B. M. Role of HOX genes in stem cell differentiation and cancer; Hindawi Limited, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlic; Zafferani, M.; Padroni, G.; Puri, M.; Hargrove, A. E. Regulation of MALAT1 triple helix stability and in vitro degradation by diphenylfurans. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48(14), 7653–7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughney, M.; et al. Regenerative lineages and immune-mediated pruning in lung cancer metastasis. Nat Med 2020, 26(2), 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Porath; et al. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet 2008, 40(5), 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Guoan, C.; Kalemkerian, G. P.; Wicha, M. S.; Beer, D. G. An embryonic stem cell-like signature identifies poorly differentiated lung adenocarcinoma but not squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2009, 15(20), 6386–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang; et al. Multi-omics analyses reveal biological and clinical insights in recurrent stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, E.; Qiu, X. Overexpression of yes-associated protein contributes to progression and poor prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2010, 101(5), 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damelin, M.; et al. Delineation of a cellular hierarchy in lung cancer reveals an oncofetal antigen expressed on tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Res 2011, 71(12), 4236–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. L.; Harrop, R. 5T4 oncofoetal antigen: an attractive target for immune intervention in cancer; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 01 Apr 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad; et al. Emerging roles of long noncoding RNA H19 in human lung cancer; John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 01 Jun 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, E.; et al. Reactivation of multiple fetal mirnas in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; et al. Oncofetal IGF2BP3-mediated control of microRNA structural diversity in the malignancy of early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121(36). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pewarchuk, M. E.; et al. Identification of oncofetal PIWI-interacting RNAs as potential prognostic biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Genet 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, S. L.; et al. “Migration-Stimulating Factor: A Genetically Truncated Onco-Fetal Fibronectin Isoform Expressed by Carcinoma and Tumor-Associated Stromal Cells,” 2003. Available online: http://aacrjournals.org/cancerres/article-pdf/63/24/8827/2511244/zch02403008827.pdf.

- De Zuani, M.; et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics analysis of non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun 2024, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; et al. The role of YAP1 in liver cancer stem cells: proven and potential mechanisms; BioMed Central Ltd, 01 Dec 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu; et al. “Immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and their cross talks in hepatocellular carcinoma,” 2023; Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Han, S. X.; et al. Expression and clinical significance of YAP, TAZ, and AREG in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol Res 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Biagioni, F.; et al. Decoding YAP dependent transcription in the liver. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50(14), 7959–7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simile, M. M.; et al. Post-translational deregulation of YAP1 is genetically controlled in rat liver cancer and determines the fate and stem-like behavior of the human disease. Oncotarget 2016, 7(31), 49194–49216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Deregulation of Hippo kinase signalling in Human hepatic malignancies. Liver International 2012, 32(1), 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S. H.; Camargo, F. D.; Yimlamai, D. Hippo Signaling in the Liver Regulates Organ Size, Cell Fate, and Carcinogenesis; W.B. Saunders, 01 Feb 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun; Oh, S. H.; Premont, R. T.; Guy, C. D.; Berg, C. L.; Diehl, A. M. Dysregulated activation of fetal liver programme in acute liver failure. Gut 2019, 68(6), 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitamant; et al. YAP Inhibition Restores Hepatocyte Differentiation in Advanced HCC, Leading to Tumor Regression. Cell Rep 2015, 10(10), 1692–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubero, F. J.; Martinez-Chantar, M. L. Plasticity of adult hepatocytes and readjustment of cell fate: A novel dogma in liver disease; BMJ Publishing Group, 01 Jun 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devan, R.; et al. The role of glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights into diagnosis and therapeutic potential. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. W.; et al. Lin28B is an oncofetal circulating cancer stem cell-like marker associated with recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 2013, 8(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.; et al. Oncofetal Gene SALL4 in Aggressive Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368(24), 2266–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Han, X.; Yao, S. K.; Wang, X. L.; Yang, H. C. Importance of SALL4 in the development and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22(9), 2837–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. X.; et al. Serum SALL4 is a novel prognosis biomarker with tumor recurrence and poor survival of patients in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol Res 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Tietze; Kessler, S. M. The Good, the Bad, the Question–H19 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 5(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Yang, F. Long noncoding RNA H19 inhibits the proliferation of fetal liver cells and the Wnt signaling. FEBS Lett 2016, 4(590), 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding; et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 is associated with tumor progression and predicts recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncol Lett 2015, 9(2), 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma; et al. Onco-fetal Reprogramming of Endothelial Cells Drives Immunosuppressive Macrophages in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell 2020, 183(2), 377–394.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanki; Fujita, J.; Yang, Y.; Hojo, S.; Bandoh, S. Expression of Oncofetal Fibronectin and Syndecan-1 mRNA in 18 Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Tumor Biology 2001, no. 22, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; et al. IMP3 promotes stem-like properties in triple-negative breast cancer by regulating SLUG. Oncogene 2016, 35(9), 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Reis, S.; et al. Increased expression of the pathological O-glycosylated form of oncofetal fibronectin in the multidrug resistance phenotype of cancer cells. Matrix Biology 2023, 118, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.; et al. Targeting SALL4 by entinostat in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, pp. 75425–75440. Available online: www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget.

- Glaß; Hüttelmaier, S. IGF2BP1—An Oncofetal RNA-Binding Protein Fuels Tumor Virus Propagation; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 01 Jul 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; et al. Oncofetal HLF transactivates c-Jun to promote hepatocellular carcinoma development and sorafenib resistance. Gut 2019, 68(10), 1858–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey; et al. ROR1 potentiates FGFR signaling in basal-like breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolb; Salvi, S.; Oliveri, G.; Borsi, L.; Castellani, P.; Zardi, L. Expression of tenascin and of the ED-B containing oncofetal fibronectin isoform in human cancer. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, T. M.; et al. Oncofetal chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycans are key players in integrin signaling and tumor cell motility. Molecular Cancer Research 2016, 14(12), 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickholtz; et al. “Cooperation between BRCA1 and vitamin D is critical for histone acetylation of the p21waf1 promoter and for growth inhibition of breast cancer cells and cancer stem-like cells,” 2014. Available online: www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/.

- Rokavec, H. Li; Jiang, L.; Hermeking, H. The p53/miR-34 axis in development and disease; Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A; Bahadur, RP. Modular architecture and functional annotation of human RNA-binding proteins containing RNA recognition motif. Biochimie;Epub 2023, 209, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).