1. Introduction

Climate change has been the center of attention during the 21

st century and decarbonization of the industry seems to be mandatory. Maritime transportation plays an important role in the worldwide economy and despite being one of the most efficient means of transportation, it still has a significant and continuously growing share in worldwide emissions. With shipping being responsible for around 2.9% of global emissions caused by human activities, and these emissions being suspected to grow anywhere from 90% to 130% of 2008 emissions by 2050 [

1], it is mandatory for immediate action to be taken in order to reduce them. In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) announced a new policy framework with the ambition of cutting down greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions at least in half by 2050 compared to their level in 2008, with the ultimate goal to phase out GHG emissions from shipping as soon as possible. Moreover, this policy framework aims to reduce the carbon intensity of international shipping by at least 40% by 2030, with efforts to reduce it by 70% by 2050 compared to 2008 [

2].

With shipping being a multi-trillion dollar industry, projected to grow even more in the upcoming years, it is clear that its decarbonization will be a huge economic and logistic challenge. The presently available technology is simply not capable of achieving IMO’s goals for decarbonization [

3], thus the improvement of existing and the development of new ways of improving energy efficiency of ships are urgently needed. Even though there is a wide variety of potential design and operational solutions to improve a vessel’s energy efficiency, modifying the propulsion and power systems seem to be the most direct and promising ones. Modern ships mainly rely on diesel engines for both propulsion and electric power generation, so naturally, changing the fuel used in shipping seems to be the best solution for achieving IMO’s long term goals for decarbonization. Fuels like ammonia could in theory be used to achieve zero CO

2 emissions, however, each one of these fuels poses new technical challenges that make their implementation difficult. For example, ammonia is a very toxic and difficult to store substance, not to mention its very limited availability and high cost [

4]. Furthermore, careful life cycle assessment of any proposed fuel is required in order to correctly assess the overall CO

2 emissions taking into account not only those from its combustion but also possible indirect ones during its production or supply chain. These challenges, although not insurmountable, make the successful implementation of a new fuel uncertain. Thus, no potential candidate for improving the ship’s energy efficiency shall be ruled out, as it could end up helping with the decarbonization of the industry in the mid or long term.

The use of turbines (e.g. steam or gas turbines) has not succeeded to dominate the shipping industry. Steam turbines, despite being the main mean of propulsion in the early days of steam ships, have quickly become obsolete due to the use of diesel engines. Another prime example of this phenomenon is Liquifed Natural Gas (LNG) carriers, a relatively modern ship type, initially using steam turbines as their main propulsion system, in order to take advantage of the boil off gas. Yet again, dual fuel marine diesel engines have quickly replaced those systems, proving once again that diesel engines are more suitable for the propulsion and power generation onboard a ship. There are in fact many reasons why diesel engines are the main mean of ship propulsion today, the most important ones being efficiency, weight and space. The factors of weight and space are pretty self-explanatory. The more spacious and heavy a propulsion system is, the less amount of cargo can be carried by a ship of given displacement. In terms of efficiency, modern day diesel engines are more efficient in partial loads than steam and gas turbines, thus making them a more attractive solution for ship owners [

5].

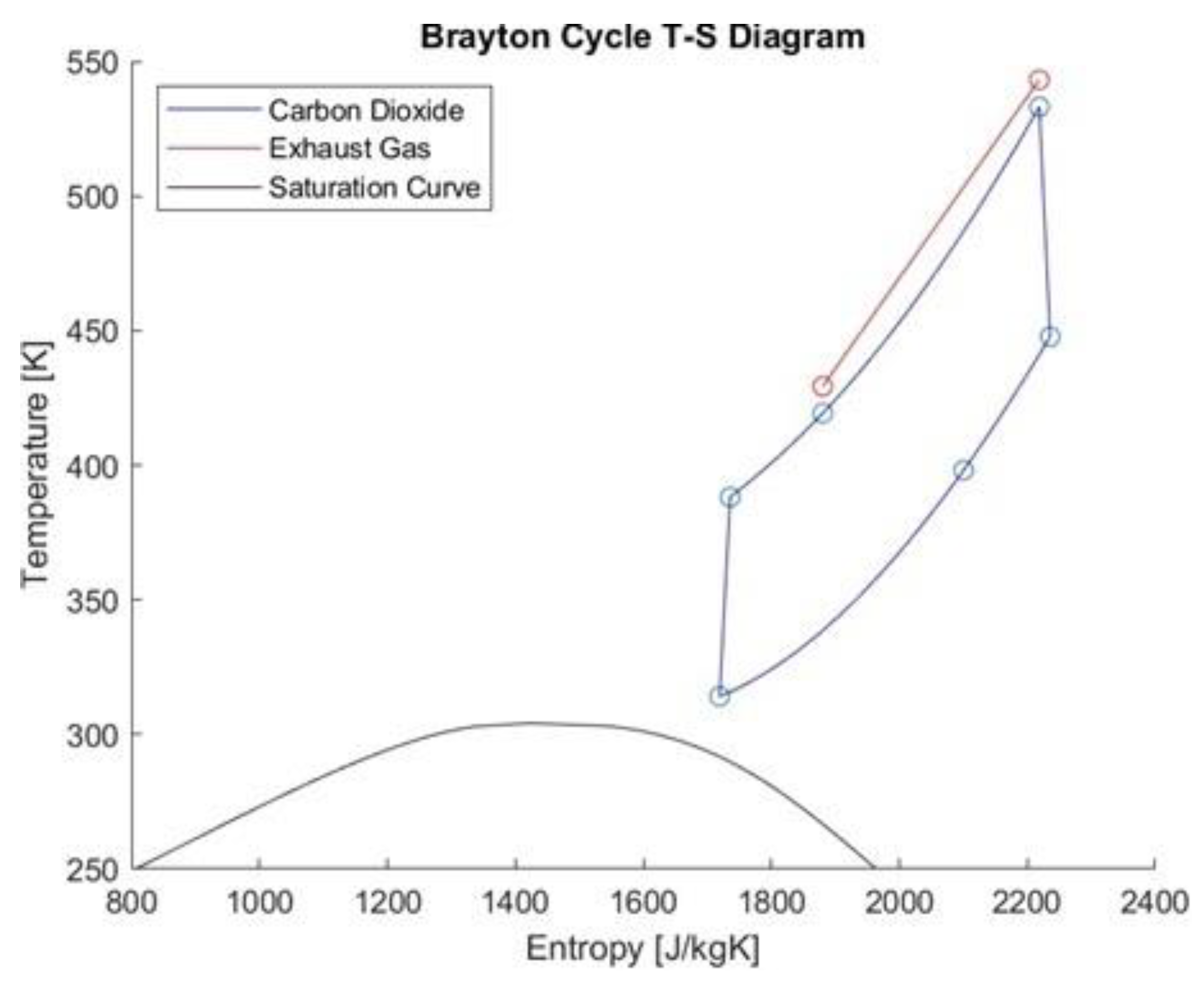

The carbon dioxide Supercritical Brayton Cycle (SBC), is a state-of-the-art technology utilizing the properties of CO2 in its supercritical state, in order to increase the thermal efficiency of the conventional Brayton cycle. The use of supercritical CO2 as the working fluid allows for a very compact installation due to its properties. The SBC has been proven to be a very promising solution to increase the energy efficiency of onshore power plants, where steam and gas turbines are still the dominant means of power generation. Despite the promise it has shown in this scenario, rather little research has been done so far in terms of its potential use on ships. Since the SBC seems highly unlikely to be used as the main method of propulsion onboard ships in the foreseeable future, the present study focuses on the potential of the SBC as a waste heat recovery system.

In 2016, Kim et al [

6] compared nine different SBC layouts for use as a bottoming cycle for a gas turbine. The comparison revealed that the recompression cycle, despite having the highest theoretical thermal efficiency, is not suitable for bottoming cycle applications. Moreover, it was found that a dual heated Brayton cycle with flow split produces the highest net thermodynamic work; this configuration, however, is extremely complex and requires sophisticated operational strategies. In Held et al. [

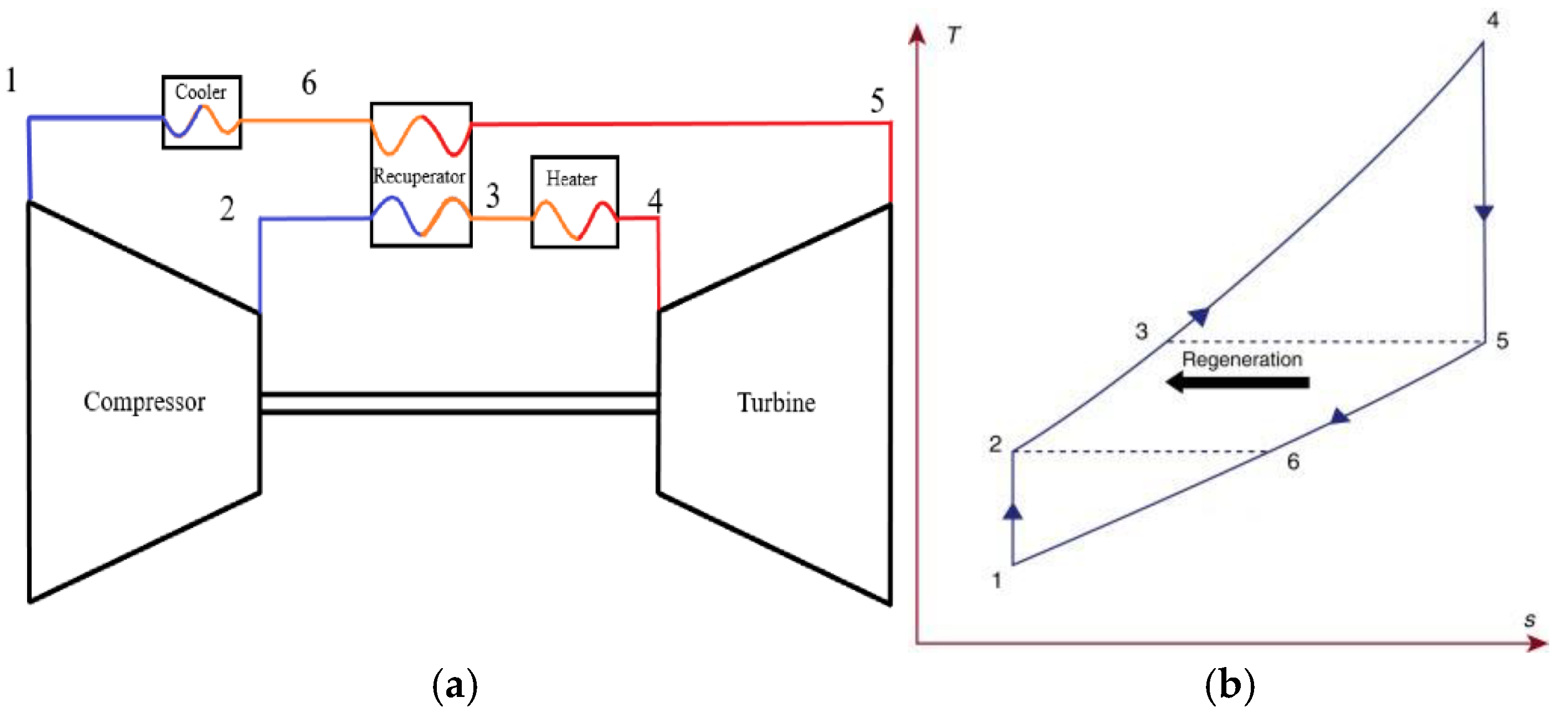

7], a model of a SBC for use in a gas turbine combined cycle power plant was presented and various aspects of the technology were analyzed. The selected configuration was the recuperated Brayton cycle, since more complex architectures like the recompression cycle perform poorly in bottoming cycle applications. Upon further reviewing the relevant literature, it can be concluded that recompression seems not a popular option for waste heat recovery applications. Recuperation on the other hand is very popular among the various configurations, with more than one recuperators being used in some cases. Furthermore, the simplicity, smaller size, and allegedly better off-design performance of the recuperated cycle are great advantages when used for WHR purposes. Due to the aforementioned reasons, the Recuperated Supercritical Brayton Cycle (RSBC) is selected to be the configuration of study for the present work.

In higher pressures, the behavior of real gases deviates from that of ideal gases, since their molecules in practice interact each other. Since most power cycles run on high pressure, it is important to be able to describe the behavior of real gases. Throughout the years, numerous real gas models have been developed. These models express a relation between the three main thermodynamic properties of a gas, namely pressure, volume and temperature. The key difference is that real gas models take into consideration compressibility effects, differences in specific heat capacity, van der Waals forces, non-equilibrium thermodynamic effects etc. Although such analytical models are not always used for most applications, they are necessary at very high pressures near the critical point or near the condensation point [

8]. Thus, they are a particularly important tool for analyzing the behavior of SBC. Some of the most commonly used models are the Van der Waals model, Redlich-Kwong model, Berthelot and modified Berthelot model, Dieterici model, Clausius model, Virial model, Peng-Robinson model, Wohl model etc [

8]. Alternatively, one can rely upon thermodynamic look-up tables to acquire real gas properties. Such tables are generated using complex models like the ones mentioned above and provide the various thermodynamic properties of a fluid at a given state described by two fluid properties [

9]. They are available in the form of databases for a wide variety of fluids and are quite easy to use. Such tables are used herein, by means of utilizing the free CoolProp library [

10].

The present work investigates the utilization of a supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycle for waste heat recovery from a marine diesel engine powering a LNG carrier. The mindset behind this choice is that the SBC is not yet a mature, widely available technology. In fact, it will probably take some years to become commercially ready. Pairing it to marine engines used on older ships, although beneficial in terms of increasing the ship energy efficiency, does not make any sense, as those ships will probably have already been scrapped by the time SBC systems come to market. On the other hand, alternative fuels are a hot topic in the maritime industry. Natural gas is considered to be the first alternative fuel and is being used by all modern LNG carriers. Despite not being the fuel that will achieve IMO’s 2050 goals for decarbonization, LNG carriers are currently being built in large quantities to serve the global demand for LNG. It is expected that in some years, LNG carriers, despite currently being the most advanced ships, might no longer meet the IMO’s rules for energy efficiency, thus, retrofitting new systems may become a necessity. The latter may be some kind of exhaust gas treatment devices, similar to the scrubbers outfitted in some older vessels. The use of a WHR system is also an option, due to the fact that part of the electricity used onboard ships could be produced by such a system with no further fuel consumption, by bottoming the main engine in the context of combined cycle and resulting in an improvement of the ship’s overall operational efficiency. Finally, it is important to underline the main advantage of the SCBC; since it involves lower compression work due to the sCO2 liquid-like density near its critical point, smaller size equipment (crucial for marine engineering applications), lower pressure ratio thus fewer stages in the compressors and turbines are needed, as well as a single-phase working fluid is involved resulting also to avoidance of pinch point issues in the heat exchangers.

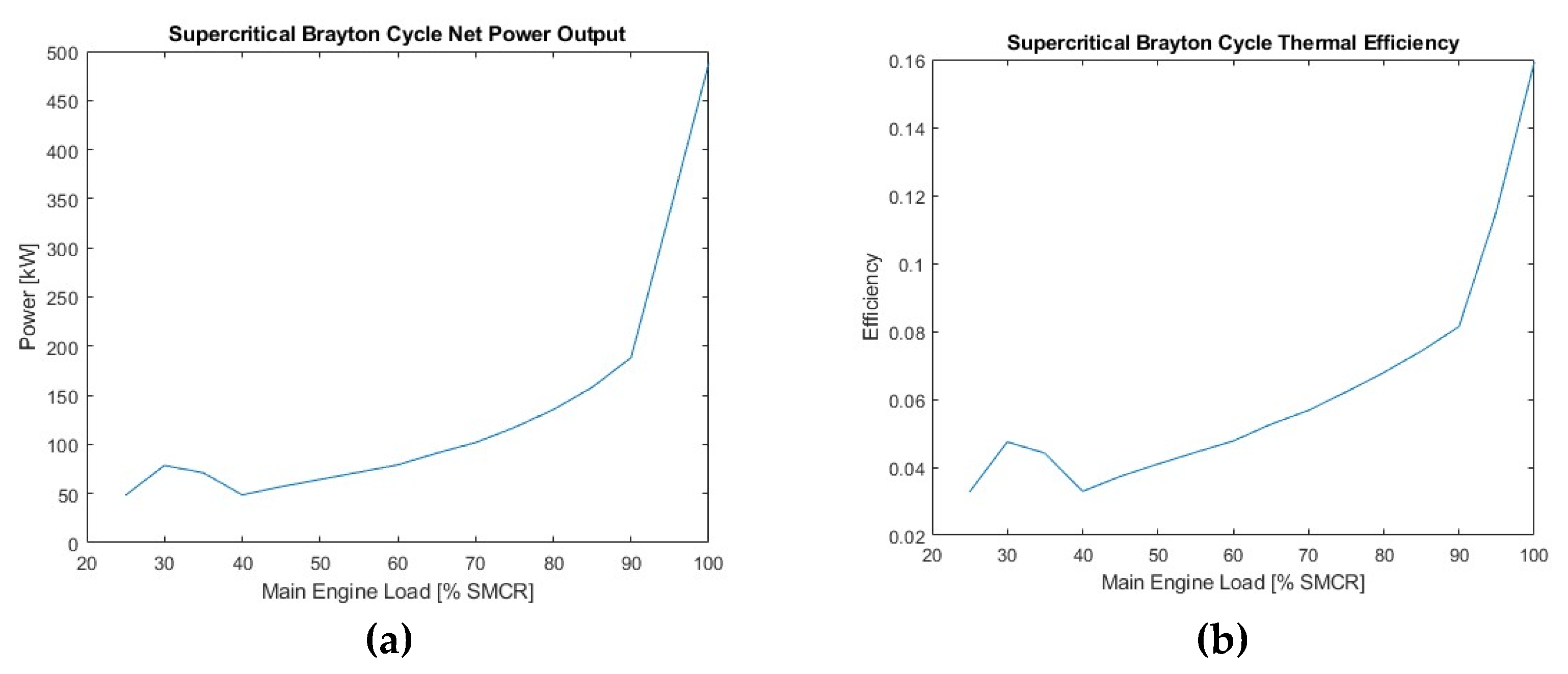

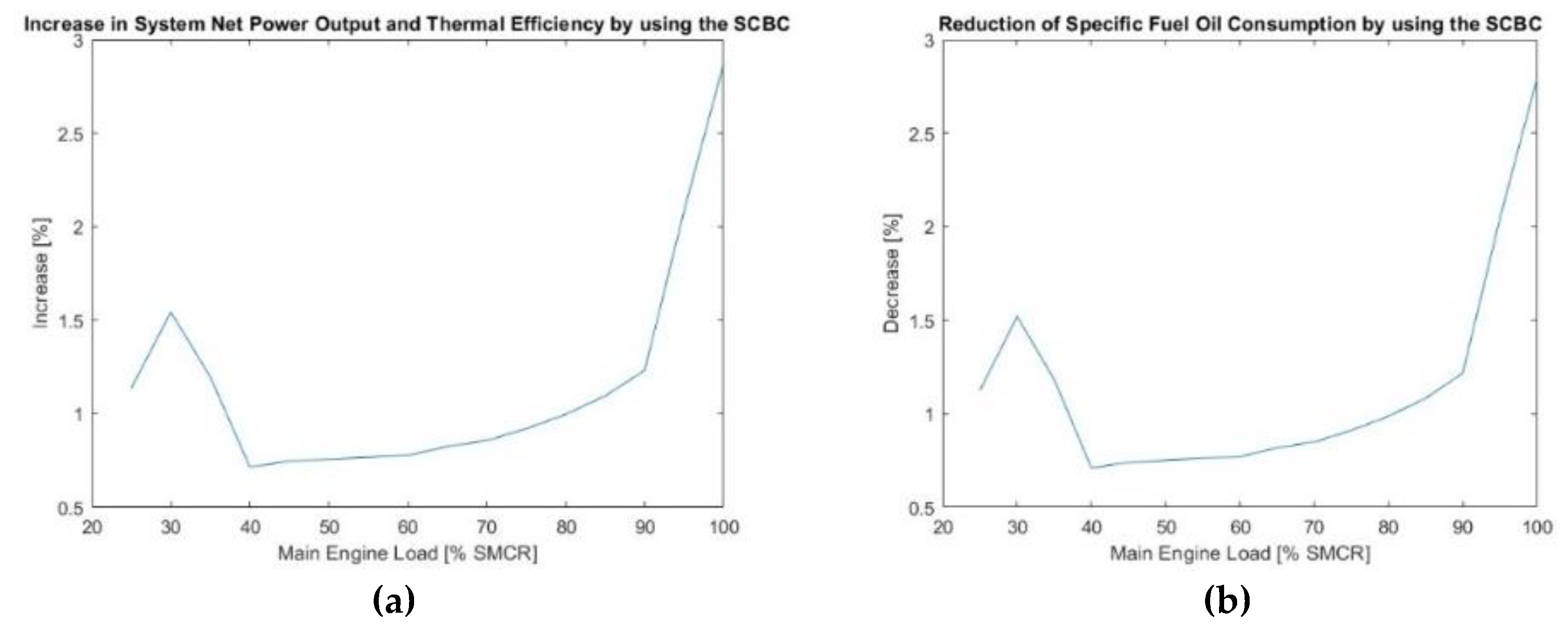

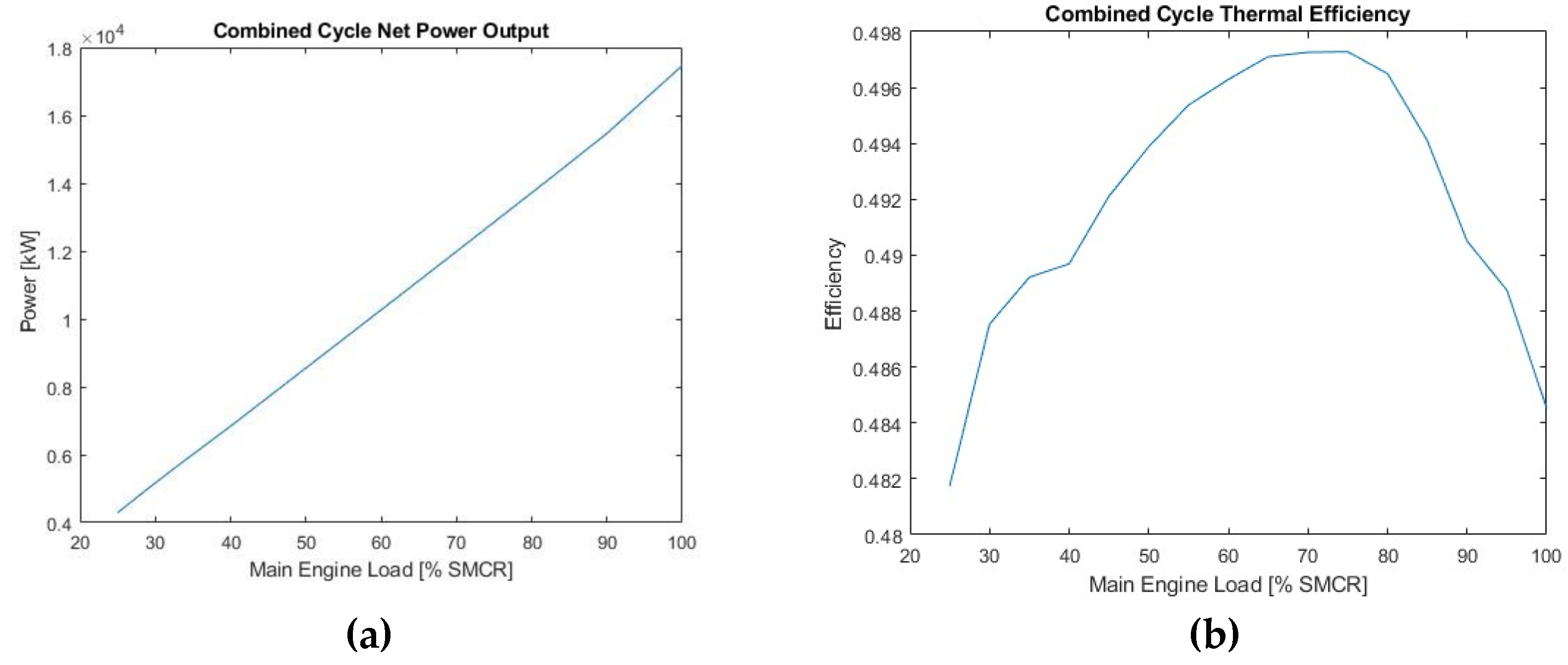

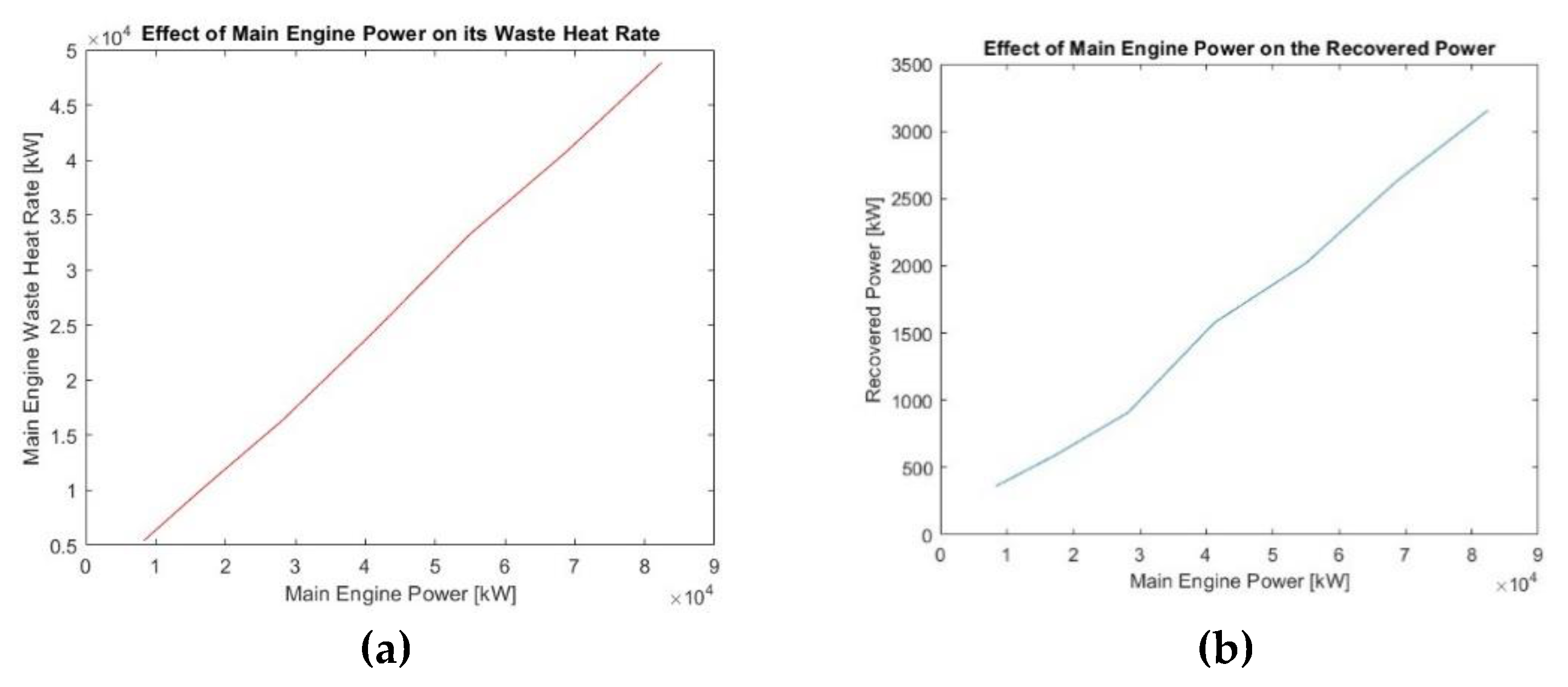

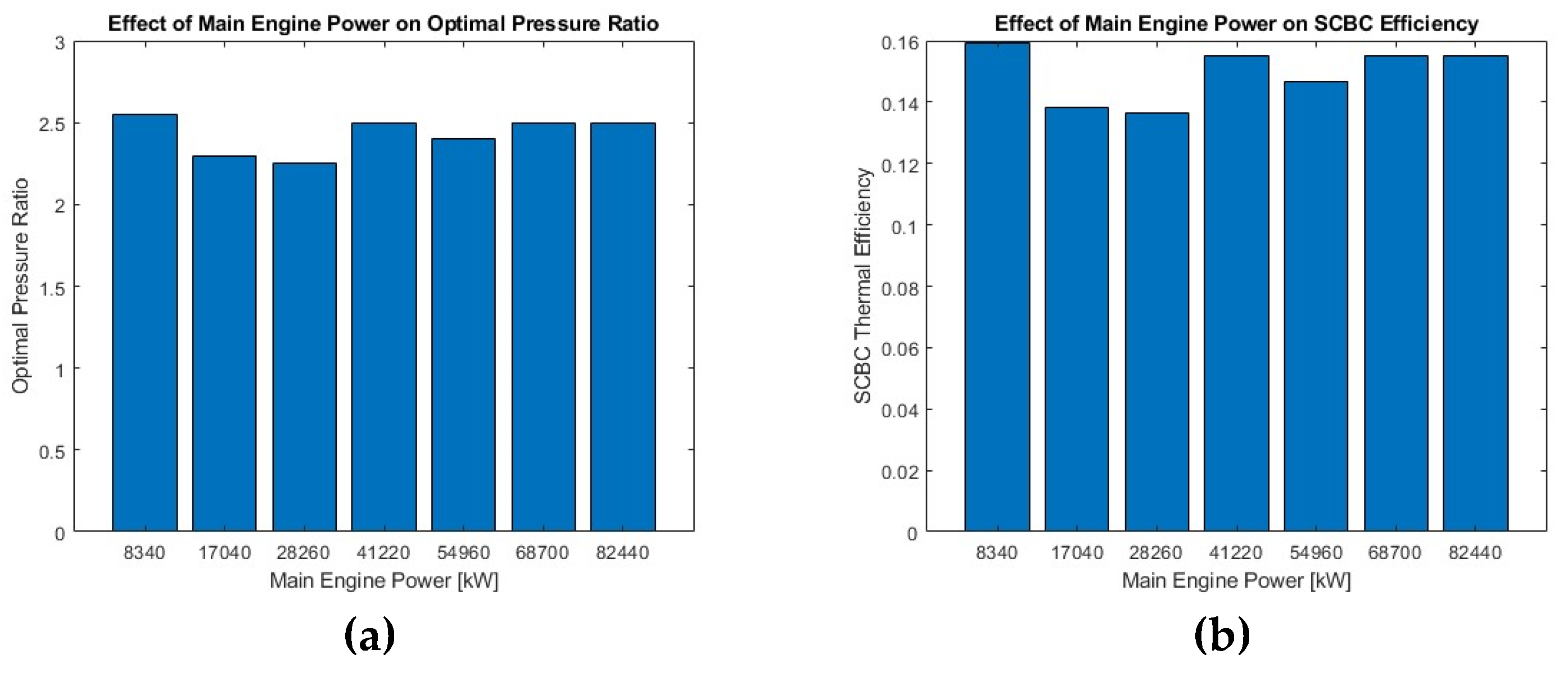

In the light of the above, the main objective of this paper is to make a preliminary design of a closed loop, recuperated SBC, indirectly fired by the waste heat of a marine engine powering a LNG carrier, to analyze its operation and assess its performance. To this end, a thermodynamic model of the SBC and the Diesel-SBC Combined Cycle (CC) is developed and programmed in MATLAB environment utilizing the CoolProp library. A case study is selected, in which the performance of the plant is assessed at the engine’s Specified Maximum Continuous Rating (SMCR), as well as at part-load operation. Furthermore, a simple study is performed using seven similar marine engines of different nominal power to assess how the CC benefits scale with the main engine power.

4. Discussion

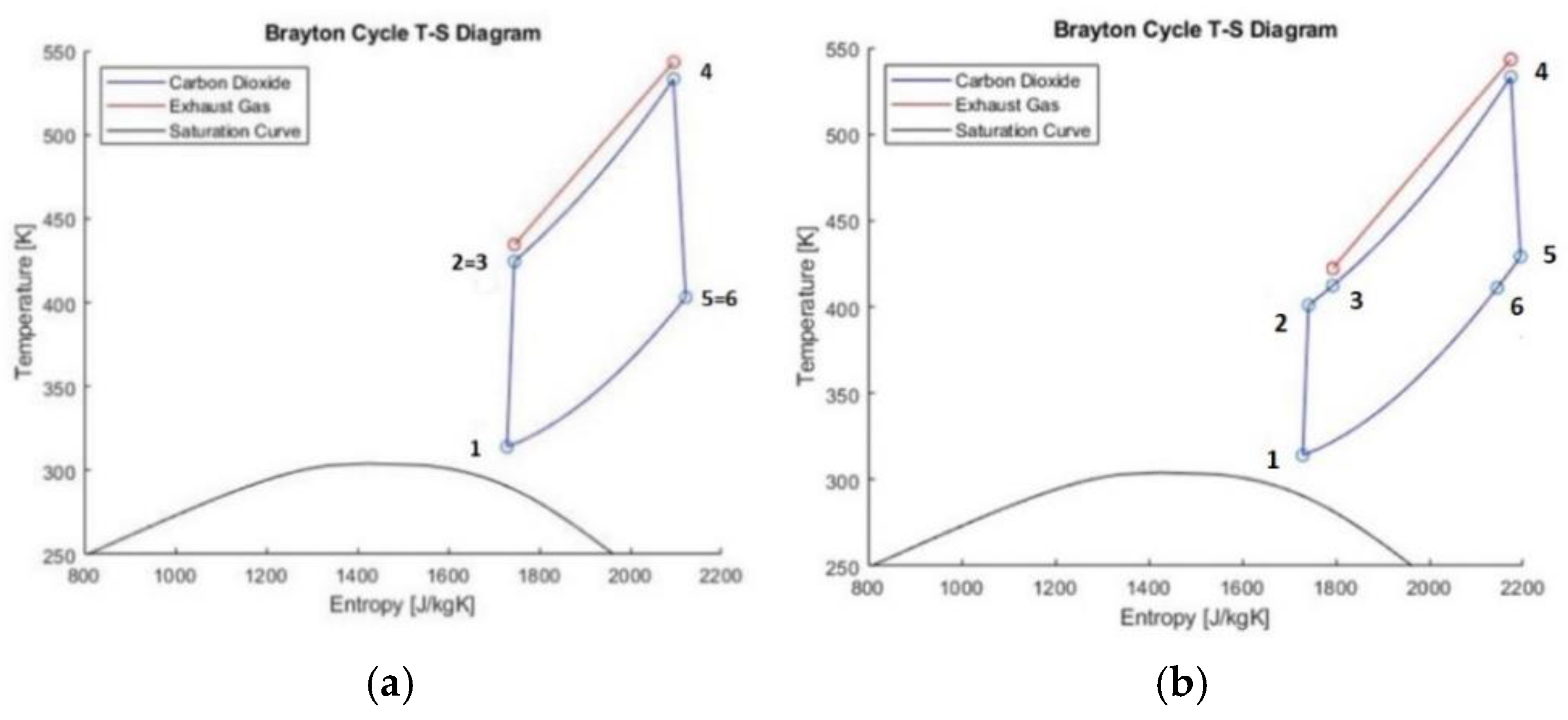

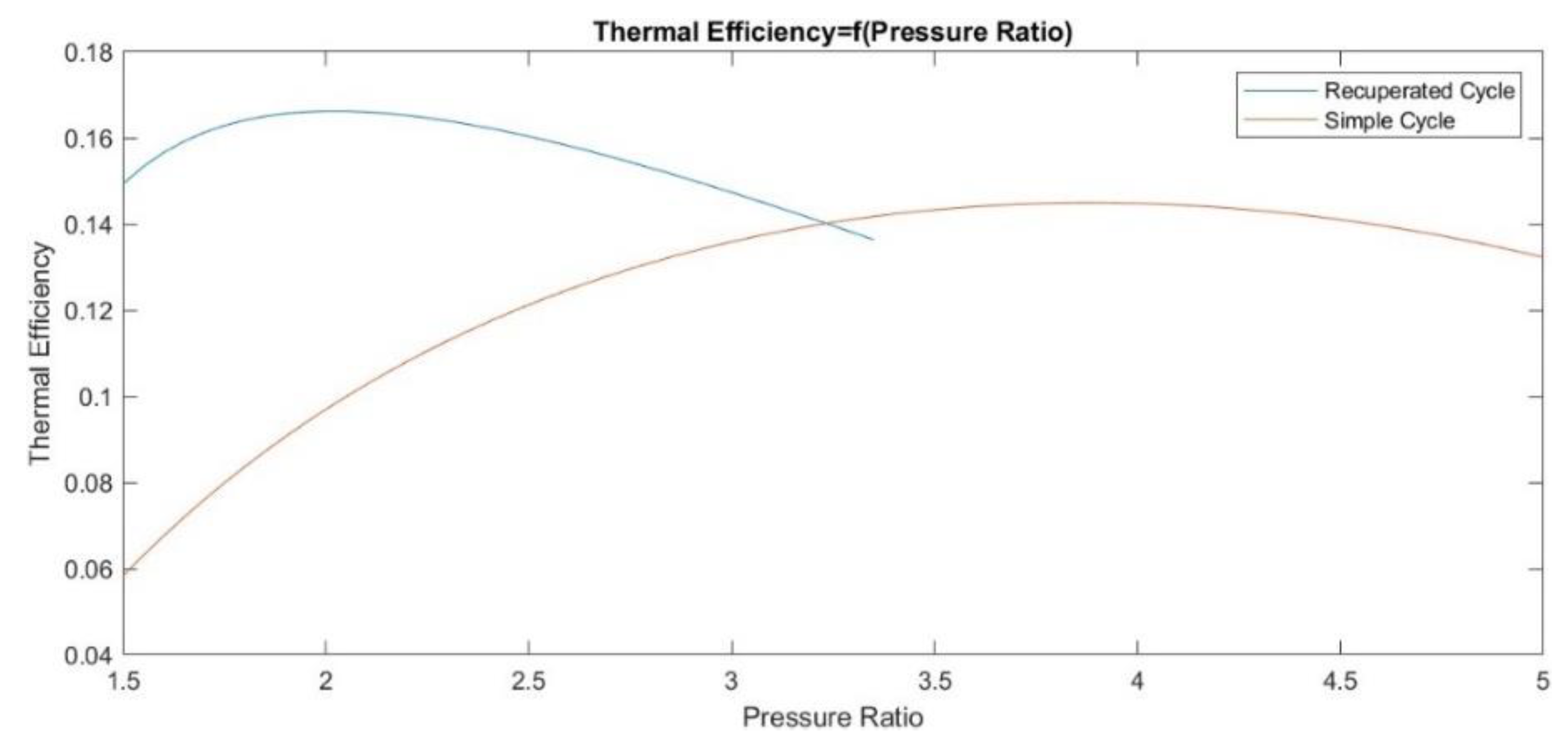

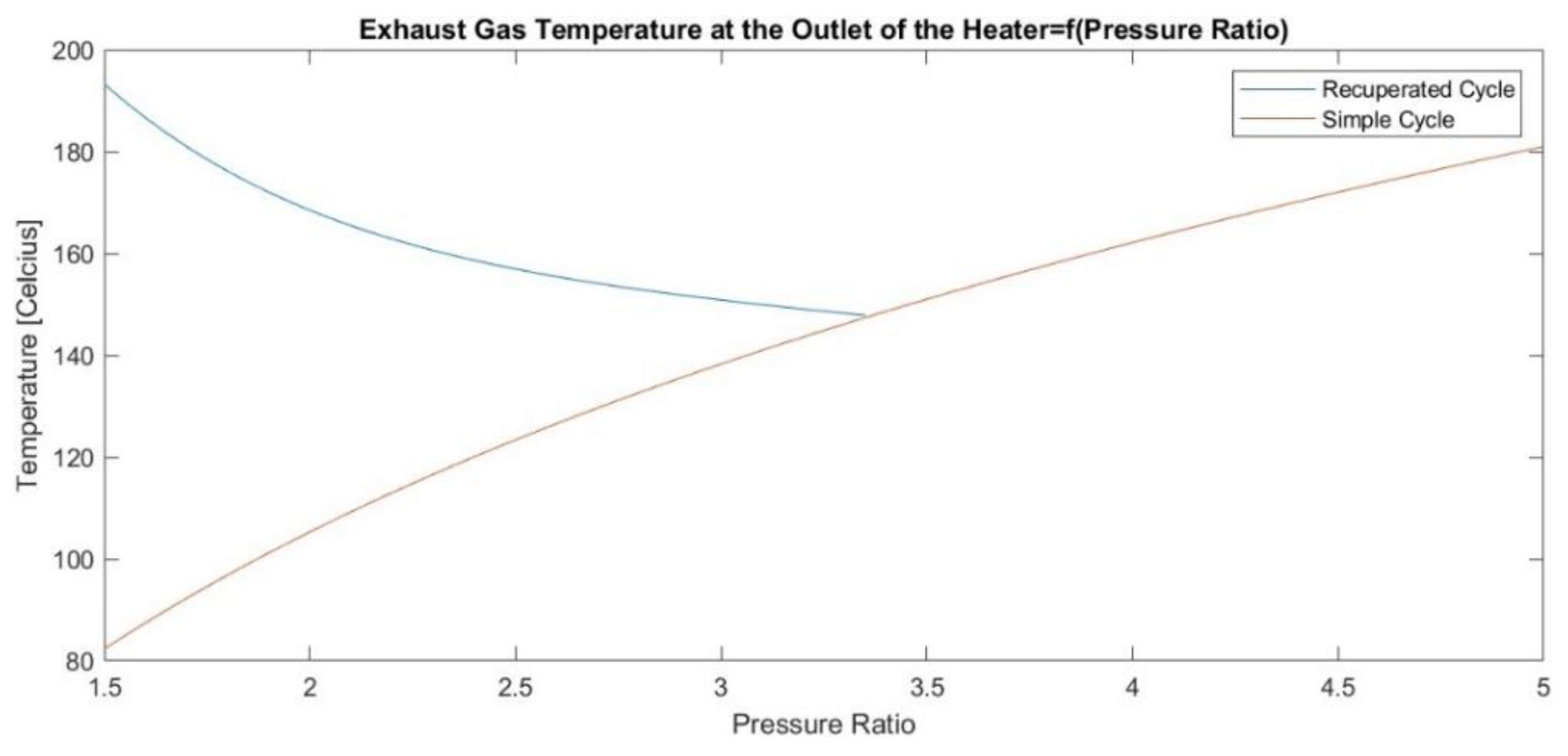

This work investigated the utilization of a carbon dioxide supercritical Brayton cycle for waste heat recovery of a LNG carrier engine. A thermodynamic model was developed and programmed in-house. The performance of simple and recuperated SBC (RSBC) for WHR of a specific marine engine at its full load operation was assessed and the optimum compressor pressure ratio for power maximization of the RSBC was selected. The designed RSBC exhibits an increase of 2.9% in thermal efficiency of the combined Diesel-SBC system and a 2.9% reduction in specific fuel oil consumption at full load operation of main engine. Performance benefits were also demonstrated at part-load operation of the main engine. To assess how the benefits scale with the main engine power, seven similar marine engines of different power were considered and their performances were compared each other, revealing that optimum SBC pressure ratio and efficiency actually scale with the temperature of the main engine exhaust gas.

To further develop the methodology developed and presented herein, the following research directions are proposed:

• Recap the major challenges of commercializing the SBC for maritime applications.

• Model the closed gas turbine cycle at partial loads.

• Perform advanced exergy analysis of the SBC with the goal of determining the performance limits of the cycle and focusing on the components that need to be further optimized.

• Examine adopting preheating by also utilizing the jacket cooling water.

• Develop a thermodynamic model for simulating the recompression SBC for waste heat recovery in maritime applications and examine the optimization of the flow split ratio.

• Compare SBC and Organic Rankine Cycle for WHR of the same engine.

• Perform an overall preliminary design of the implementation of SBC for WHR in a LNG carrier, involving feasibility and technoeconomic analysis.