Introduction

Implant-based breast reconstruction (IBBR) remains the most performed method of post-mastectomy reconstruction worldwide. Over the past decades, advances in surgical technique, biomaterials, and implant technology have driven a paradigm shift in how these procedures are performed. Surgeons have moved away from traditional subpectoral placement toward prepectoral reconstruction, enabled by improved mastectomy flap viability and the widespread use of acellular dermal matrices (ADM) and synthetic meshes. At the same time, increasing adoption of nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) has transformed both the aesthetic goals and the technical challenges of reconstruction. While restoring breast form has always been central, contemporary practice also prioritizes function, sensation, and patient-reported satisfaction. Emerging efforts at nipple–areolar complex (NAC) neurotization reflect this trend, as do adjunctive strategies such as autologous fat grafting and 3D-based aesthetic analysis. Parallel to these surgeon-driven innovations, industry advances in implant design also seek to improve both safety and outcomes.

Nevertheless, controversy persists. Cancer recurrences after NSM, breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), and the broader phenomenon of “breast implant illness” (BII) have raised new questions regarding oncologic safety and systemic risks of these breast reconstruction advances, and these concerns must be balanced against the clear benefits of implant-based approaches in appropriate candidates. This review highlights eight current “hot topics” in implant-based breast reconstruction: (1) prepectoral reconstruction, (2) nipple-sparing mastectomy, (3) oncoplastic techniques (4) nipple areolar complex (NAC) neurotization, (5) biologic matrices and synthetic meshes, (6) next-generation implants, (7) optimizing aesthetic outcomes, and (8) implant-associated cancer and systemic concerns. Together, these areas define the current landscape of innovation, controversy, and future directions in implant-based reconstruction.

Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction

Prepectoral breast reconstruction has undergone a remarkable evolution in a relatively short period, reflecting both improvements in oncologic breast surgery and sophisticated refinements in implant-based reconstruction. Historically, subpectoral implant placement was considered the gold standard because muscular coverage was believed to reduce implant visibility, protect against capsular contracture, and lower the risk of extrusion. However, as mastectomy techniques improved and skin flap perfusion became more reliable, the question emerged as to whether the pectoralis major muscle, whose primary function is unrelated to breast reconstruction, needed to be sacrificed at all.

Prepectoral reconstruction avoids elevation of the pectoralis major muscle, eliminating postoperative muscle spasm and reducing pain. Multiple studies now demonstrate that patients experience earlier return to baseline arm function, fewer activity limitations, and quicker resumption of normal daily life [

1,

2]. As enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols become widespread, prepectoral placement aligns well with patient-centered goals, decreasing opioid requirements and facilitating outpatient pathways.

Another widely cited advantage is the absence of animation deformity. In subpectoral reconstruction, contraction of the pectoralis muscle can distort the implant, creating visible tectonic shifts that are distressing to many patients, particularly those who are athletic or physically active. Prepectoral placement fully eliminates this problem, representing a meaningful improvement in aesthetic stability across dynamic positions.

Mastectomy flap viability remains the rate-limiting step. Prepectoral reconstruction relies on robust, well-perfused soft tissue to provide long-term coverage of the device. In additional to clinical exam, surgeons now have access to intraoperative perfusion imaging, like indocyanine green (ICG) angiography, to guide real-time decisions about flap viability [

3]. When flaps appear marginal, surgeons may partially or completely abandon prepectoral placement in favor of a dual-plane or subpectoral approach. This adaptability is essential, as compromised flaps increase the risk of mastectomy flap necrosis, infection, and early implant loss.

Large contemporary analyses and multiple systematic reviews demonstrate that overall complication rates are comparable between prepectoral and subpectoral reconstruction, provided appropriate patient selection [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Particularly important is the growing evidence on patient-reported outcomes, showing equal or improved satisfaction with physical well-being of the chest and aesthetic appearance in prepectoral groups [

8,

9,

10]. These data reinforce that the shift toward prepectoral placement is not only technically feasible but also valued by patients.

Despite these advances, prepectoral reconstruction introduces unique challenges. The lack of muscular coverage makes implants more palpable, particularly in thin patients, and less durable against skin flap insults [

11,

12,

13]. Rippling, implant edge visibility, and upper pole contour irregularities may require secondary fat grafting. Seroma formation is another frequently debated issue. Some series suggest higher seroma rates in prepectoral reconstruction, especially when large ADM sheets are used, though data remain mixed. Recent work highlights the importance of controlling expander fill volumes and minimizing shear forces on the mastectomy flaps to prevent seroma and implant displacement [

14,

15].

Long-term durability is another area of active investigation. Whether prepectoral implants experience higher rates of bottoming out, lateral migration, or capsular contracture compared with subpectoral placement remains uncertain. Long-term longitudinal data will better answer these questions. Nevertheless, as surgeons refine flap assessment, optimize pocket control, and improve mesh-implant constructs, prepectoral reconstruction is poised to remain a foundational technique in modern implant-based reconstruction.

Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

Nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) has arguably been one of the most transformative developments in contemporary breast cancer surgery. Its rise parallels the shifting focus from merely removing cancer to incorporating aesthetics, body image, and psychosocial recovery into surgical planning [

16]. From a reconstructive standpoint, NSM offers unparalleled advantages, preserving the native nipple position, contour, and pigmentation. Patients consistently report higher satisfaction with breast appearance, body image, and sexual well-being compared with traditional mastectomy [

17]. The technique, however, introduces a new set of challenges.

The oncologic safety of NSM has been the subject of substantial investigation. Early hesitations centered on the possibility of residual glandular tissue beneath the nipple–areolar complex (NAC) and the consequent risk of local recurrence. However, multiple long-term series and multi-institutional studies demonstrate that, in carefully selected patients, NSM carries oncologic outcomes equivalent to skin-sparing or total mastectomy [

18,

19,

20]. Patient selection remains critical, with tumor-to-nipple distance, retroareolar involvement, and intraoperative frozen section playing key roles in decision-making (

TABLE 1). In prophylactic settings, NSM is widely considered safe, although rare reports of new primaries within the preserved NAC have been described [

21].

NSM introduces specific technical challenges for breast reconstruction. Nipple ischemia and partial or total NAC necrosis remain important complications, with risk factors including periareolar incisions, smoking, prior radiation, diabetes, elevated BMI, and thin or compromised flaps [

12]. Adoption of inframammary or lateral incisions, meticulous tissue handling, and reliance on ICG angiography have dramatically reduced complication rates [

22,

23]. Yet even with optimal technique, partial NAC necrosis remains a possibility, emphasizing the need for thoughtful patient counseling.

NSM has also altered the aesthetics of implant-based reconstruction. Because the NAC is preserved, the reconstructed breast must achieve harmony in shape, projection, and upper pole contour. This often synergizes with prepectoral reconstruction and ADM or mesh reinforcement, which allow fine control of pocket dynamics and projection [

15,

24]. Incision placement is also crucial; lateral radial and inframammary incisions provide the best balance of access and aesthetic concealment.

Increasingly, NSM is also connected to functional restoration, particularly through NAC neurotization [

25]. Patients often express greater disappointment with loss of sensation than with loss of the breast itself. NSM preserves the external anatomy, but without neurotization, the nipple remains insensate. As NSM becomes standard, functional restoration becomes an increasingly important adjunct. Overall, NSM represents a convergence of oncologic safety, aesthetic outcomes, and functional advancements. As surgical and reconstructive techniques continue to improve, NSM will remain central to modern breast reconstruction strategies.

Oncoplastic Techniques

Oncoplastic techniques have broadened reconstructive possibilities for patients undergoing mastectomy or treatment after breast conserving therapy (BCT), bridging the gap between aesthetic breast surgery principles and oncologic safety. Among these techniques, the Wise-pattern mastectomy (with or without the inferior dermal flap) and implant-based reconstruction after lumpectomy and radiation represent two scenarios with high aesthetic expectations and notable reconstructive challenges.

Wise-pattern mastectomy allows oncologic resection in patients with macromastia or significant breast ptosis by combining a skin-reducing pattern with predictable control of the skin envelope [

26,

27]. This facilitates creation of an ideal breast footprint and nipple position while eliminating redundant tissue that would otherwise compromise implant positioning. For patients with large or ptotic breasts, a traditional skin-sparing mastectomy may leave an oversized, poorly draping envelope that increases the risk of malposition, bottoming out, and poor implant aesthetics.

The Wise-pattern approach enables immediate placement of an appropriately sized implant or tissue expander in a tailored envelope shaped to match the final breast form [

26]. However, the technique introduces unique reconstructive risks. The T-point, the intersection of vertical and inframammary incisions, remains a well-recognized area of vascular compromise. Partial skin necrosis at this site can expose the implant, require debridement, or disrupt pocket integrity. The Wise-pattern approach uniquely allows for the creation of an inferior dermal flap (“autoderm”) that can be used as a vascularized tissue layer between the implant and the mastectomy skin flap, which is especially useful at the area of the T-point [

28,

29]. Even with this autoderm flap, the use of prepectoral implants in Wise-pattern cases requires careful flap perfusion and often necessitates protective measures such as staged reconstruction, mesh-supported pockets, or intraoperative downsizing of the implant.

Despite these challenges, aesthetic outcomes can be excellent when flap viability is preserved. The Wise pattern allows precise repositioning of the nipple–areolar complex, predictable control of lower pole projection, and improved symmetry for bilateral cases. Patients with significant ptosis often prefer the postoperative breast shape achieved with this pattern, as it avoids the bottomed-out appearance that may occur without skin reduction. In certain cases, NSM can be performed via the Wise pattern with the NAC being perfused by a dermal flap [

30]. If this is not possible but saving the NAC is oncologically safe, free nipple grafting has also been used successfully to provide an aesthetic and oncologically safe result [

31,

32]. Future directions in this area include refined perfusion-based algorithms, hybrid reconstruction strategies (implant plus fat grafting), and selective use of biosynthetic mesh to decrease tension on the T-junction and improve durability of lower-pole support.

Reconstruction after lumpectomy and radiation represents a distinct subset of implant-based reconstruction with biomechanical and aesthetic considerations that differ from immediate post-mastectomy reconstruction [

33,

34,

35]. Radiation induces fibrosis, volume loss, contour deformity, and skin tightening that can create a challenging environment for later implant placement. Increasing numbers of patients treated initially with lumpectomy and radiation later desire breast reshaping or develop deformities substantial enough to warrant conversion to mastectomy with implant-based reconstruction.

For patients undergoing mastectomy after BCT, implant-based reconstruction must account for the decreased elasticity, compromised microvasculature, and higher infection and capsular contracture rates associated with prior radiation. Subpectoral placement of the implant has been preferred, sometimes combined with mesh to achieve pocket control, to offer better soft-tissue protection [

34]. However, oncologic safety of either plane is debated with some studies showing subpectoral safe and some showing prepectoral safer [

36,

37].

When deformity occurs after lumpectomy without mastectomy, options for implant-based contour correction include small-volume implants, with occasional combined fat-implant approaches. Fat grafting remains a central tool in radiated tissue, serving both an aesthetic and regenerative role by improving pliability and soft-tissue thickness, but patients may require multiple sessions for optimal correction. Outcomes after implant-based reconstruction in the post-BCT setting are generally less predictable than those after mastectomy in non-irradiated patients. Capsular contracture, especially high-grade, is a known risk, often necessitating secondary reconstruction or conversion to autologous tissue [

33,

34]. For patients who strongly prefer implants, careful preoperative counseling and shared decision-making are critical to establishing realistic expectations.

Despite these challenges, selected patients can achieve good aesthetic and functional outcomes, particularly when reconstruction is staged and supported by adjunctive fat grafting or mesh reinforcement. Ongoing research into radiation-mitigating therapies and expanded indications for neurotization and biosynthetic support materials may further improve implant outcomes in this historically high-risk population.

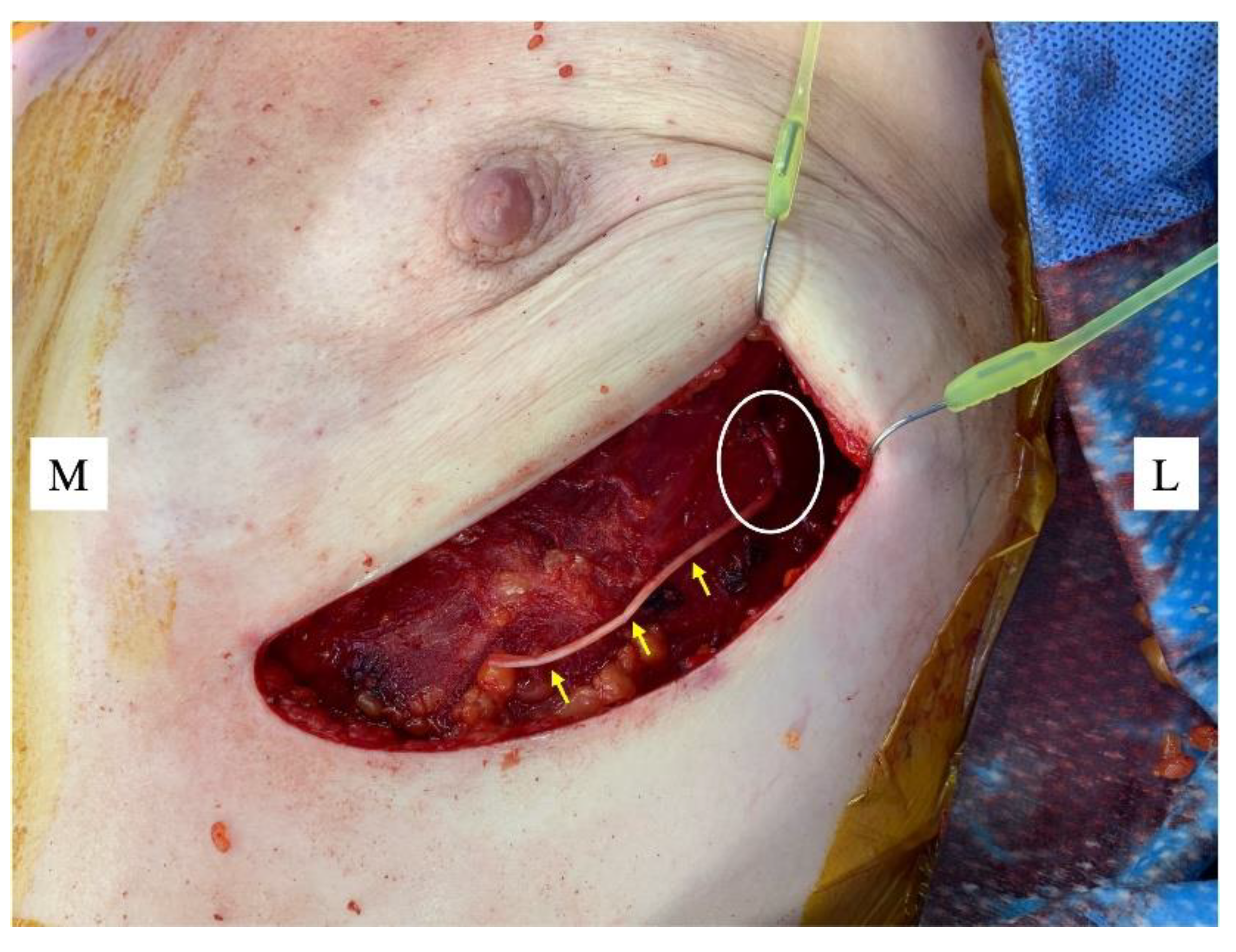

Nipple Areolar Complex (NAC) Neurotization

Restoration of NAC sensation is a frontier that reflects the maturation of IBBR from purely cosmetic restoration to comprehensive functional rehabilitation. Sensory loss can negatively influence sexual function, embodiment, temperature perception, and overall quality of life [

38,

39]. Traditional mastectomy severs intercostal nerve branches that supply the breast skin and NAC. Without intentional reconstruction of this pathway, sensory recovery is limited and unpredictable. NAC neurotization aims to address this by re-establishing innervation through coaptation of preserved intercostal nerve branches to the undersurface of the NAC using nerve allografts or autografts [

40] (

FIGURE 1).

Optimizing Aesthetic Outcomes

While IBBR reliably restores breast form, optimizing aesthetic outcomes remains a central focus of contemporary practice. Increasingly, patients are expecting a highly natural appearing result that closely mimics (or even improves upon) their original, native breasts. Thus, aesthetic success depends not only on implant placement but also on careful management of mastectomy flaps, adjunctive procedures, and establishment of long-term symmetry. Adjunctive fat grafting has become an essential tool for refining contour, correcting rippling, and improving soft tissue coverage [

46]. Beyond aesthetics, fat grafting may also enhance flap vascularity and reduce radiation-induced fibrosis, though concerns about oncologic safety continue to be studied [

47]. This is especially important in revision reconstruction, where radiation or weight fluctuations have distorted normal anatomy. Nipple reconstruction may also be desired after skin sparing mastectomy (SSM).

Pocket selection and control also play critical roles. The use of the prepectoral plane can improve upper-pole contour and eliminate animation deformity but requires well-vascularized mastectomy flaps. In addition to lateral pocket plication sutures, mesh-implant constructs can also be used to secure the implant in the breast pocket and create a stable implant position [

15]. These mesh-implant constructs can also be used in revision procedures to restore symmetry after radiation or weight-loss induced changes. Patient-reported outcomes are equally critical. Instruments such as the BREAST-Q have demonstrated that aesthetic success is strongly tied to patient satisfaction, body image, and psychosocial well-being. These measures highlight that even technically “ideal” results must be interpreted through the lens of patient perception.

Nipple reconstruction, when needed, contributes to aesthetic completeness. Even in an era where NSM predominates, nipple reconstruction remains relevant for patients undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy. Techniques range from local flap reconstruction to tattoo-only approaches, each offering different balances of projection, longevity, and complexity, and can be performed in a delayed or immediate fashion [

48].

Managing patient expectations is fundamental. Revision strategies remain common even in supposedly “one stage DTI” based breast reconstruction, and capsular contracture, asymmetry, malposition, and rippling may necessitate secondary procedures. Understanding risk factors, especially the use of radiation, is essential for setting patient expectations regarding the anticipated result. Ultimately, optimizing aesthetic outcomes in IBBR requires a multimodal and thoughtful methodical approach to achieve durable, natural-appearing results, and surgeons must counsel patients that achieving symmetry and natural appearance frequently requires staged interventions.

Biologic Matrices and Synthetic Meshes

The introduction of biologic matrices and synthetic meshes has transformed IBBR by expanding reconstructive options and improving implant support [

14] (

TABLE 2). Initially popularized in subpectoral reconstructions, acellular dermal matrices (ADM) provided inferolateral coverage, pocket control, and improved aesthetic contour though are not explicitly approved by the FDA for use in the breast [

49,

50,

51]. Their use has since extended to prepectoral reconstruction, where ADM is frequently used to provide a layer of reinforcement between the implant and mastectomy flaps, helping to reduce complications and improve cosmesis [

52,

53]. Despite these benefits, ADM use remains controversial. Studies have demonstrated associations with higher rates of seroma, infection, and red breast syndrome, though findings are inconsistent across institutions [

54,

55]. Cost also poses a significant barrier, as ADM can account for a substantial portion of reconstructive expenses, raising questions about cost-effectiveness in the absence of clear long-term outcome advantages [

56]. While some studies demonstrate improved aesthetic and patient-reported outcomes with ADM, others show minimal difference when compared with no-ADM reconstruction. This heterogeneity reflects differences in patient selection, flap quality, implant plane, and ADM type.

As cost and complication concerns surrounding ADM grew, synthetic and biosynthetic meshes emerged as alternatives. These materials, including P4HB (GalaFLEX), TIGR mesh, PDO (Durasorb), and other long-term resorbable scaffolds, offer temporary support that is gradually replaced by native tissue [

57,

58]. Early evidence suggests comparable complication rates to ADM with lower cost and potentially fewer seromas [

59,

60]. Biosynthetic meshes are especially attractive for prepectoral DTI reconstruction, where they provide a semi-rigid anterior layer that prevents folding, supports projection, and reduces implant motion. The long-term performance of synthetic scaffolds remains under study. As these materials resorb, the durability of the collagenous capsule they leave behind becomes critical. Emerging data, including from studies of P4HB constructs in prepectoral DTI reconstruction, suggest promising stability and low complication rates [

48].

Ultimately, matrix and mesh selection should be individualized. The optimal reinforcement strategy depends on flap thickness, patient comorbidities, radiation history, implant plane, and surgeon expertise.

Next Generation Implants

Advances in implant technology continue to shape the landscape of IBBR (

TABLE 3). Historically, concerns about implant rupture, capsular contracture, and textured implant safety have driven innovation toward safer and more durable devices, and current development has focused on improving biocompatibility, and enhancing patient satisfaction. One area of focus is breast implant surface design. Following the global recall of macrotextured implants due to their association with breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), smooth and microtextured surfaces have become the standard [

61,

62]. Novel “nanotextured” implants were introduced to provide the theoretical benefits of texturing (reduced rotation and contracture) while minimizing oncologic risk, though long-term outcome data are still limited and initial enthusiasm has been tempered by reports of higher malposition and rotation rates [

63,

64]. They are also not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in breast reconstruction.

The development of highly cohesive silicone gel implants, often referred to as “gummy bear” implants, has improved shape retention and reduced the risk of silicone bleed in the event of rupture [

65]. More recently, lightweight implants incorporating microspheres or alternative fillers have been introduced to reduce implant weight by up to 30%, aiming to decrease strain on mastectomy flaps, lower pole descent, and chronic discomfort. Early reports suggest high levels of patient satisfaction, but robust long-term data remain lacking [

66]. These devices are used widely for aesthetic breast augmentation but have been increasingly introduced for alloplastic breast reconstruction with unpublished studies ongoing that investigate their use.

Beyond structural modifications, next-generation implants are being explored for integration with regenerative strategies. Research into bioactive coatings, antimicrobial surfaces, and drug-eluting technologies holds the potential to further reduce capsular contracture, infection, and other complications [

67,

68,

69]. As innovation continues, the challenge remains to balance technological advances with rigorous long-term safety data.

Implant-Associated Cancers and Systemic Concerns

The safety of breast implants has come under renewed scrutiny with the recognition of rare but serious implant-associated malignancies and the increasing attention to systemic symptomatology reported by some patients. Breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) is a rare T-cell lymphoma that develops in the capsule surrounding textured implants, most commonly presenting as late-onset periprosthetic seroma or, less frequently, as a capsular mass [

61,

70]. After diagnosis confirmation with biopsy of the seroma fluid or mass, management typically involves total capsulectomy and implant removal, with most patients achieving durable remission when diagnosed early. These findings have led to global recalls of macrotextured implants and changes in regulatory guidance [

62].

More recently, breast implant–associated squamous cell carcinoma (BIA-SCC) has been described though fewer than 20 cases have been reported worldwide [

71,

72,

73]. Importantly, and different than BIA-ALCL, BIA-SCC has a very aggressive clinical course which should prompt heightened clinical concern. Unlike BIA-ALCL, which is strongly linked to textured implants, BIA-SCC has been documented in association with both smooth and textured implants, as well as in both aesthetic and reconstructive populations, and reported latency periods are long, often 10 or more years after initial implantation [

73]. Clinically, BIA-SCC can present like BIA-ALCL with progressive pain, breast swelling, and/or capsular contracture. Unlike BIA-ALCL, which frequently presents with a late periprosthetic effusion, BIA-SCC is more often associated with a solid tumor component invading the capsule or adjacent tissues. Imaging typically reveals irregular capsular thickening or a mass abutting the implant, and diagnosis is confirmed through capsule or mass biopsy demonstrating keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma.

The true incidence of BIA-SCC remains unknown and is presumed to be extremely low, but it must be stressed that any new breast mass, persistent pain, or unexplained swelling in long-term implant patients warrants prompt imaging and biopsy. BIA-SCC appears to have a more aggressive natural history than BIA-ALCL, with multiple reported cases demonstrating chest wall invasion, lymph node metastases, or distant spread at presentation. This disease carries a very poor prognosis with estimated six-month mortality rate of about 10%, and one-year mortality rate of nearly 25% [

72,

73]. Treatment requires complete surgical resection including implant removal, total capsulectomy without spillage, and often mastectomy with resection of adjacent tissue, if present [

71]. As awareness grows and molecular profiling advances, future studies may clarify the mechanisms underlying BIA-SCC and help stratify patient risk. For now, BIA-SCC underscores the importance of long-term follow-up in implant patients and reinforces the need for transparent, evidence-based counseling regarding both the benefits and rare but serious risks associated with alloplastic breast reconstruction.

In parallel, increasing numbers of patients have reported systemic symptoms attributed to their implants, collectively referred to as “breast implant illness” (BII) though this is much less common in patients undergoing breast reconstruction compared to patients undergoing breast augmentation [

74]. While anecdotal reports suggest symptomatic improvement following explantation and anterior capsulectomy, there is no consensus on diagnostic criteria, pathophysiology, or causal linkage between implants and systemic disease [

75]. Despite limited scientific evidence, patient advocacy has driven regulatory bodies and professional societies to acknowledge BII as an important clinical entity requiring empathetic, patient-centered counseling [

76]. The recognition of implant-associated malignancies and the growing awareness of BII highlight the need for robust surveillance, transparent preoperative patient counseling, and continued research into implant safety.

Conclusions

Implant-based breast reconstruction continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in surgical technique, biomaterials, and implant design. Balanced against these innovations are important safety considerations, and the reconstructive surgeon must be careful to innovate while safeguarding patient trust and well-being. Future progress will depend on prospective, multicenter studies that establish standardized outcomes, long-term follow-up, and comparative effectiveness across reconstructive options. By addressing technical challenges, incorporating patient-centered metrics, and maintaining vigilance regarding safety, surgeons can continue to refine implant-based reconstruction to achieve durable, natural, and safe outcomes for patients.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments related to this paper to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this paper to report.

References

- Sbitany, H; Piper, M; Lentz, R. Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction: A Safe Alternative to Submuscular Prosthetic Reconstruction following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017, 140(3), 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziano, FD; Lu, J; Sbitany, H. Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 2023, 50(2), 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amro, C; Sorenson, TJ; Boyd, CJ; et al. The Evolution of Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: Innovations, Trends, and Future Directions. J Clin Med. 2024, 13(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapenko, E; Nixdorf, L; Devyatko, Y; Exner, R; Wimmer, K; Fitzal, F. Prepectoral Versus Subpectoral Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systemic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2023, 30(1), 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L; Liu, C. Postoperative Complications Following Prepectoral Versus Partial Subpectoral Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Using ADM: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2023, 47(4), 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, IT; Farajzadeh, MM; Bekisz, JM; Boyd, CJ; Gibson, EG; Salibian, AA. Prepectoral versus Subpectoral Breast Reconstruction after Nipple-sparing Mastectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2024, 12(5), e5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, TJ; Boyd, CJ; Hemal, K; Choi, M; Karp, N; Cohen, O. Failure of Salvage in Prepectoral Implant Breast Reconstruction: A Single-Center Cohort. Am Surg. 2025, 31348251405560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, M; Yu, JZ; Tran, JP; et al. Surgical and Patient-Reported Outcomes of 694 Two-Stage Prepectoral versus Subpectoral Breast Reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023, 152(4S), 43S–54S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, KL; Johnson, L; Sinai, P; et al. Patient-reported outcomes 3 and 18 months after mastectomy and immediate prepectoral implant-based breast reconstruction in the UK Pre-BRA prospective multicentre cohort study. Br J Surg 2025, 112(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J; Shammas, RL; Montes-Smith, E; et al. Complications and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Prepectoral vs Submuscular Breast Reconstruction Following Nipple Sparing Mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemal, K; Boyd, C; Perez Otero, S; et al. Is a Seroma the “Kiss of Death” in Prepectoral Tissue Expander Reconstruction? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2025, 13(6), e6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Otero, S; Hemal, K; Boyd, CJ; et al. Minimizing Nipple-Areolar Complex Complications in Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction After Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Ann Plast Surg 2024, 92 4S Suppl 2, S179–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemal, K; Boyd, C; Otero, SP; et al. Finding the Right Fill: The Ideal Tissue Expander Fill in Immediate Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2025, 94 4S Suppl 2, S134–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, IT; Farajzadeh, MM; Boyd, CJ; Bekisz, JM; Gibson, EG; Salibian, AA. Do we need acellular dermal matrix in prepectoral breast reconstruction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2023, 86, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, N; Sorenson, TJ; Boyd, CJ; et al. The GalaFLEX “Empanada” for Direct-to-Implant Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025, 155(3), 488e–491e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, JJ; Boyd, CJ; Hemal, K; et al. Techniques for Success in Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Immediate Reconstruction. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanoff, A; Zabor, EC; Stempel, M; Sacchini, V; Pusic, A; Morrow, M. A Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcomes After Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Conventional Mastectomy with Reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018, 25(10), 2909–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, CJ; Bekisz, JM; Ramesh, S; et al. No Cancer Occurrences in 10-year Follow-up after Prophylactic Nipple-sparing Mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2023, 11(6), e5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, CJ; Salibian, AA; Bekisz, JM; et al. Long-Term Cancer Recurrence Rates following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: A 10-Year Follow-Up Study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 150, 13S–19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakub, JW; Peled, AW; Gray, RJ; et al. Oncologic Safety of Prophylactic Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy in a Population With BRCA Mutations: A Multi-institutional Study. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153(2), 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, CJ; Ramesh, S; Bekisz, JM; et al. Low Cancer Occurrence Rate following Prophylactic Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 153(1), 37e–43e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, CL; Dayaratna, N; Easwaralingam, N; et al. Developing an Indocyanine Green Angiography Protocol for Predicting Flap Necrosis During Breast Reconstruction. Surg Innov. 2025, 32(2), 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, CL; Zhou, M; Easwaralingam, N; et al. Mastectomy skin flap necrosis after implant-based breast reconstruction: Intraoperative predictors and indocyanine green angiography. Plast Reconstr Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, MH; Essawy, OMM; Moaz, I; et al. Single stage direct -to- implant breast reconstruction following mastectomy (The use of Ultrapro® Mesh). World J Surg Oncol. 2024, 22(1), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, TJ; Boyd, CJ; Park, JJ; et al. Nipple Areolar Complex (NAC) Neurotization After Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy (NSM) in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Breast J. 2025, 2025, 2362697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandón, JM; Butterfield, JA; Christiano, JG; et al. Wise Pattern versus Transverse Pattern Mastectomy in Two-Stage Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2023, 152(4S), 69S–80S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, J; Dortch, J; TerKonda, S; et al. Comparing morbidity rates between wise pattern and standard horizontal elliptical mastectomy incisions in patients undergoing immediate breast reconstruction. Breast J 2019, 25(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A; Kuchta, K; Alva, D; Sisco, M; Seth, AK. Wise-Pattern Mastectomy with an Inferior Dermal Sling: A Viable Alternative to Elliptical Mastectomy in Prosthetic-Based Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024, 153(3), 505e–515e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, T; Skibba, KE; Hansen, T; Amalfi, A; Chen, E. Safety of Breast Reconstruction Using Inferiorly Based Dermal Flap for the Ptotic Breast. Ann Plast Surg 2022, 88 3 Suppl 3, S156–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, Y; Kulahci, Y; Irgil, C; Calikapan, M; Noyan, N. Skin-reducing subcutaneous mastectomy using a dermal barrier flap and immediate breast reconstruction with an implant: a new surgical design for reconstruction of early-stage breast cancer. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2010, 34(1), 71–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, GG; Marchetti, A; Dalla Pozza, E; et al. Skin-Reduction Breast Reconstructions with Prepectoral Implant. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016, 137(6), 1702–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marongiu, F; Bertozzi, N; Sibilio, A; Tognali, D; Mingozzi, M; Curcio, A. The First Use of Human-Derived ADM in Prepectoral Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction after Skin-Reducing Mastectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2021, 45(5), 2048–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, HM; Ainuz, BY; Pourmoussa, AJ; et al. Oncoplastic Augmentation Mastopexy in Breast Conservation Therapy: Retrospective Study and Postoperative Complications. Ann Plast Surg 2023, 90(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnea, Y; Friedman, O; Arad, E; et al. An Oncoplastic Breast Augmentation Technique for Immediate Partial Breast Reconstruction following Breast Conservation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017, 139(2), 348e–357e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaverien, MV; Stutchfield, BM; Raine, C; Dixon, JM. Implant-based augmentation mammaplasty following breast conservation surgery. Ann Plast Surg 2012, 69(3), 240–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, SY; Lavigne, E; Holowaty, EJ; et al. Canadian breast implant cohort: extended follow-up of cancer incidence. Int J Cancer 2012, 131(7), E1148-57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubietz, MG; Janis, JE; Jakubietz, RG; Rohrich, RJ. Breast Augmentation: Cancer Concerns and Mammography-A Literature Review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004, 113(7), 117e–22e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossett, LA; Lowe, J; Sun, W; et al. Prospective evaluation of skin and nipple-areola sensation and patient satisfaction after nipple-sparing mastectomy. J Surg Oncol 2016, 114(1), 11–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, JB; Kandi, LA; Armstrong, VL; et al. Long-term breast and nipple sensation after nipple-sparing mastectomy with implant reconstruction: Relevance to physical, psychosocial, and sexual well-being. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2022, 75(9), 2914–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, AW; Peled, ZM. Nerve Preservation and Allografting for Sensory Innervation Following Immediate Implant Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2019, 7(7), e2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djohan, R; Scomacao, I; Knackstedt, R; Cakmakoglu, C; Grobmyer, SR. Neurotization of the Nipple-Areola Complex during Implant-Based Reconstruction: Evaluation of Early Sensation Recovery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020, 146(2), 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peled, AW; von Eyben, R; Peled, ZM. Sensory Outcomes after Neurotization in Nipple-sparing Mastectomy and Implant-based Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2023, 11(12), e5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C; Moroni, EA; Moreira, AA. One Size Does Not Fit All: Prediction of Nerve Length in Implant-based Nipple-Areola Complex Neurotization. J Reconstr Microsurg 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyu, S; Chang, TN; Lu, JY; et al. Breast neurotization along with breast reconstruction after nipple sparing mastectomy enhances quality of life and reduces denervation symptoms in patient reported outcome: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, CJ; Hemal, K; Sorenson, TJ; et al. Assessing Perioperative Complications and Cost of Nipple-Areolar Complex Neurotization in Immediate Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: A Matched-Paired Comparison. Ann Plast Surg 2025, 94 4S Suppl 2, S118–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichman, KE; Broer, PN; Tanna, N; et al. The role of autologous fat grafting in secondary microsurgical breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2013, 71(1), 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuruvilla, AS; Yan, Y; Rathi, S; Wang, F; Weichman, KE; Ricci, JA. Oncologic Safety in Autologous Fat Grafting After Breast Conservation Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Literature. Ann Plast Surg 2023, 90(1), 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, TS; Francalancia, S; Laspro, M; Tanney, K; Larson, B; Mitra, A. Immediate Nipple Reconstruction in Skin-sparing Mastectomy with A Modified Wise-pattern Design. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2024, 12(7), e5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, CJ; Bekisz, JM; Choi, M; Karp, NS. Catch-22: Acellular Dermal Matrix and U.S. Food and Drug Administration Premarket Approval-How Can We Construct Studies? Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 150(6), 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blohmer, JU; Beier, L; Faridi, A; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Aesthetic Results after Immediate Breast Reconstruction Using Human Acellular Dermal Matrices: Results of a Multicenter, Prospective, Observational NOGGO-AWOGyn Study. Breast Care (Basel) 2021, 16(4), 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulies, IG; Salzberg, CA. The use of acellular dermal matrix in breast reconstruction: evolution of techniques over 2 decades. Gland Surg. 2019, 8(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salibian, AA; Bekisz, JM; Kussie, HC; et al. Do We Need Support in Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction? Comparing Outcomes with and without ADM. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021, 9(8), e3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salibian, AA; Frey, JD; Choi, M; Karp, NS. Subcutaneous Implant-based Breast Reconstruction with Acellular Dermal Matrix/Mesh: A Systematic Review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016, 4(11), e1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugue, D; Kim, DK; Powell, SD; et al. Trends in Acellular Dermal Matrix Utilization in Postmastectomy Tissue Expander Placement: An 11-Year Retrospective Study. Ann Plast Surg 2025, 94 4S Suppl 2, S128–S133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avraham, T; Weichman, KE; Wilson, S; et al. Postoperative Expansion is not a Primary Cause of Infection in Immediate Breast Reconstruction with Tissue Expanders. Breast J 2015, 21(5), 501–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, TP; Loo, BYK; Yong, N; Chia, CLK; Lohsiriwat, V. Review: Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy for Breast Cancer: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Prospective Studies Comparing Use of Acellular Dermal Matrix (ADM) Versus Without ADM. Ann Surg Oncol 2024, 31(5), 3366–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnautovic, A; Williams, S; Ash, M; Menon, A; Shauly, O; Losken, A. Outcomes in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Utilizing Biosynthetic Mesh: A Meta-Analysis. Aesthet Surg J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalove, S; O’Rorke, E; Maxwell, GP; Gabriel, A. Evaluation of the Safety of a GalaFLEX-AlloDerm Construct in Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 150, 75S–81S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffley, M; Tang, A; Sawar, K; et al. Comparative Postoperative Complications of Acellular Dermal Matrix and Mesh Use in Prepectoral and Subpectoral One-Stage Direct to Implant Reconstruction: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Plast Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, TJ; Boyd, CJ; Hemal, K; et al. Outcome of Prepectoral Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction With the Poly-4-hydroxybutyrate Wrap. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2025, 13(11), e7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, PG; Ghione, P; Ni, A; et al. Risk of breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in a cohort of 3546 women prospectively followed long term after reconstruction with textured breast implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2020, 73(5), 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, CJ; Salibian, AA; Bekisz, JM; Karp, NS; Choi, M. Patient Decision-Making for Management of Style 410 Anatomical Implants in Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2023, 151(3), 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazir, U; Patani, N; Heeney, J; Mokbel, K. Pre-pectoral Immediate Breast Reconstruction Following Conservative Mastectomy Using Acellular Dermal Matrix and Semi-smooth Implants. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42(2), 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, HY; Rysin, R; Zer, M; Shachar, Y. A single surgeon’s experience with Motiva Ergonomix round SilkSurface silicone implants in breast reconstruction over a 5-year period. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2023, 80, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, MH; Shenker, R; Silver, SA. Cohesive silicone gel breast implants in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005, 116(3), 768-79; discussion 780-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govrin-Yehudain, J; Dvir, H; Preise, D; Govrin-Yehudain, O; Govreen-Segal, D. Lightweight breast implants: a novel solution for breast augmentation and reconstruction mammaplasty. Aesthet Surg J 2015, 35(8), 965–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y; Liang, Q; Liu, Q; et al. Compliant, Tough, Fatigue-Resistant, and Biocompatible PHEMA-Based Hydrogels as a Breast Implant Material. ACS Omega 2025, 10(31), 35301–35308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K; Rifai, A; Recek, N; et al. Nanocarbon-Polymer Composites for Next-Generation Breast Implant Materials. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16(38), 50251–50266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heno, F; Azoulay, Z; Khalfin, B; et al. Comparing the Antimicrobial Effect of Silver Ion-Coated Silicone and Gentamicin-Irrigated Silicone Sheets from Breast Implant Material. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2021, 45(6), 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, JA; Dabic, S; Mehrara, BJ; et al. Breast Implant-associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Incidence: Determining an Accurate Risk. Ann Surg. 2020, 272(3), 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Junior, I; Gonzaga, MI; Amirati, CC; Vilela, NM; Wohnrath, DR; da Costa Vieira, RA. Primary Breast Implant-Associated Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Proposal for a Better Surgical Approach and Clinical Staging System Based on Tumour Characteristics. Ann Surg Oncol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, S; Katel, A; Barua, A; et al. A Systematic Review of Breast Implant-Associated Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeow, M; Ching, AH; Guillon, C; Alperovich, M. Breast implant capsule-associated squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2023, 86, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, R; Stanton, E; Sorenson, TJ; et al. Breast Implant Illness as a Clinical Entity: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Aesthet Surg J 2024, 44(9), NP629–NP636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, J; Rohrich, R. Breast implant illness: a topic in review. Gland Surg 2021, 10(1), 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, N. Breast implant illness: we must counter misinformation around this mysterious condition. BMJ 2024, 384, q265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).