Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Surface and subsurface acidity (pH < 4.4) limits nutrient availability and root exploration, whereas a pH range of 5.4–6.4 ensures the availability of most nutrients that are essential for crop productivity. To ameliorate acidity in the surface and subsurface layers and improve soil chemical fertility, different application methodologies (surface, incorporation by soil tillage, or subsurface) for calcium (Ca) compounds (limestone (LS), phosphogypsum (PG), and hydrated lime (HL)) were evaluated in an agropastoral system in an Arenic Hapludalf in Brazil during the 2017–2020 seasons. Two seasons after the last application of Ca compounds, the soil was sampled and analyzed to evaluate the long-term ability of these different application methodologies. In the 0.0–0.2 m layer, the correction of surface acidity via increased pH and base saturation (BS) and reduced total acidity was maintained, but the improvement in acidity in the 0.4–0.8 m layer previously observed after the incorporation of LS and subsurface application of HL in the 2017-2018 season was not. Moreover, the improvements in Ca2+ content and Ca2+/cation exchange capacity (CEC) after applying LS plus PG and Mg2+ content and Mg2+/CEC after applying HL plus PG were preserved in the surface layer. The positive effects of these amendments on sulfate-S (S-SO42-) content throughout the soil profile (0.0–0.8 m) were not. Finally, Ca compound application had residual positive effects on P content in the 0.1–0.8 m layer and organic matter (OM) content in the 0.2–0.8 m layer.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Area

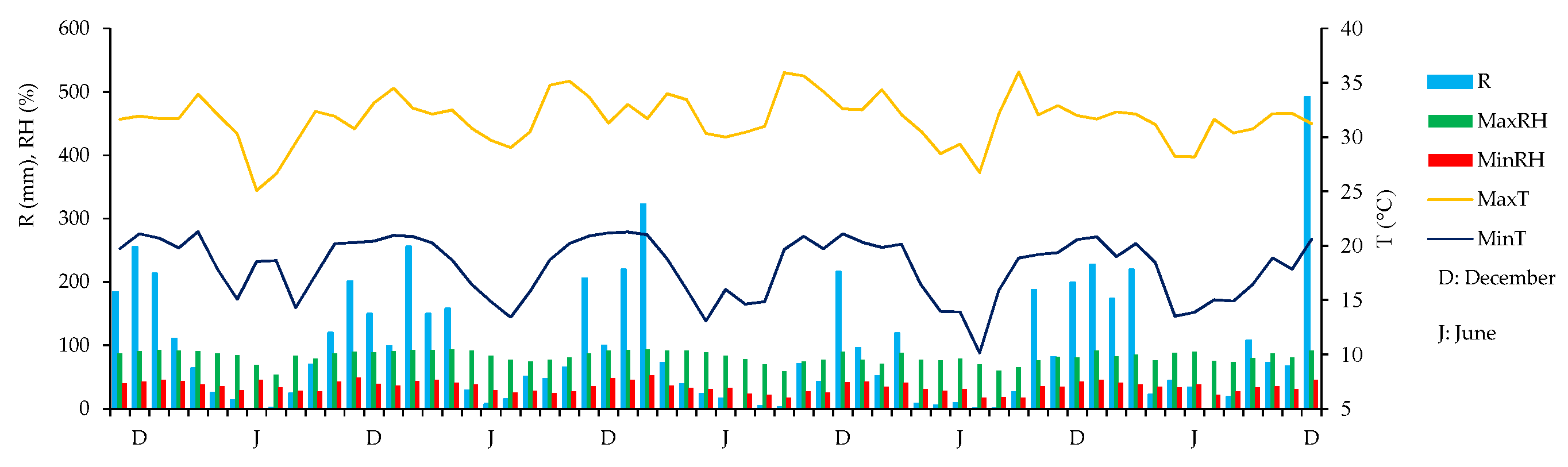

2.2. Description of Soil and Climate

2.3. Description of Experimental Design

2.4. Description of Treatments

2.5. Crop Management

2.6. Sampling and Analysis

2.6.1. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.6.2. Straw Sampling and Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

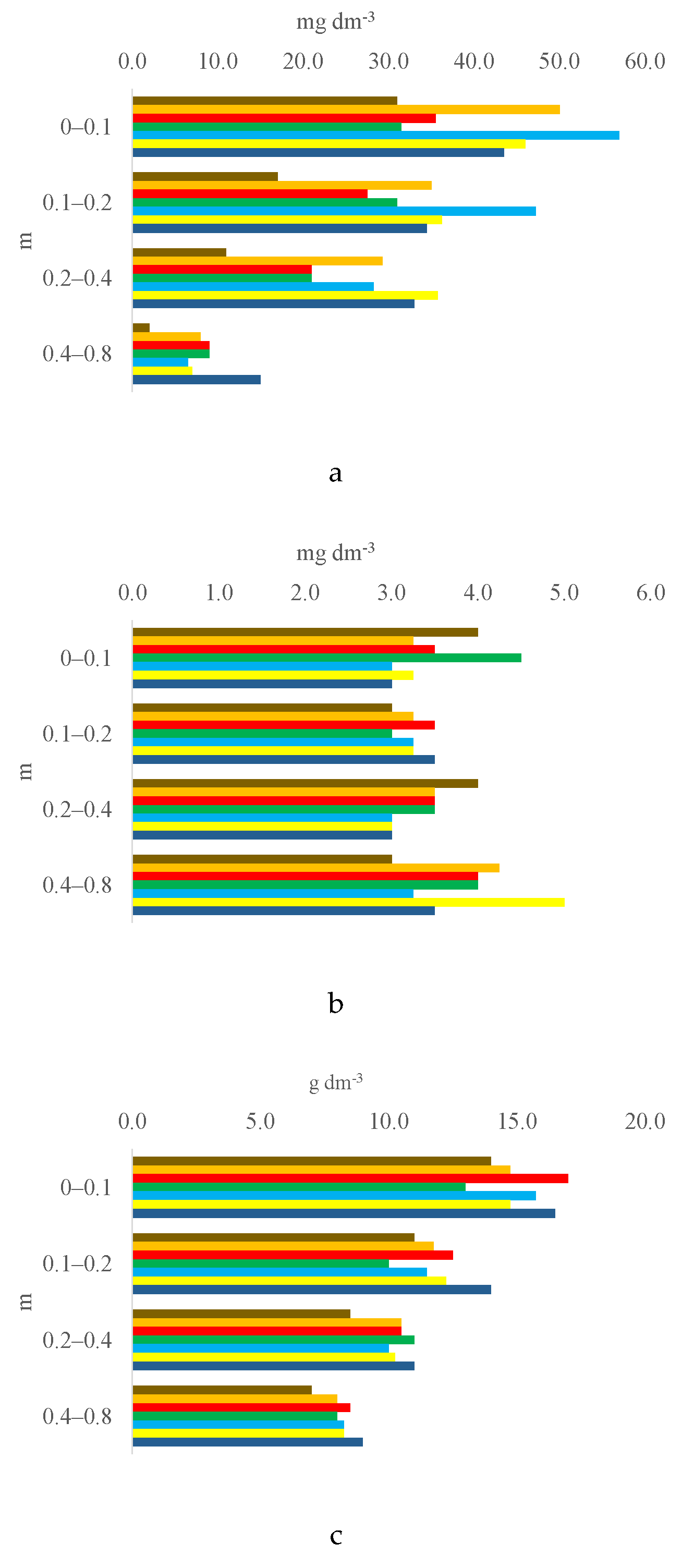

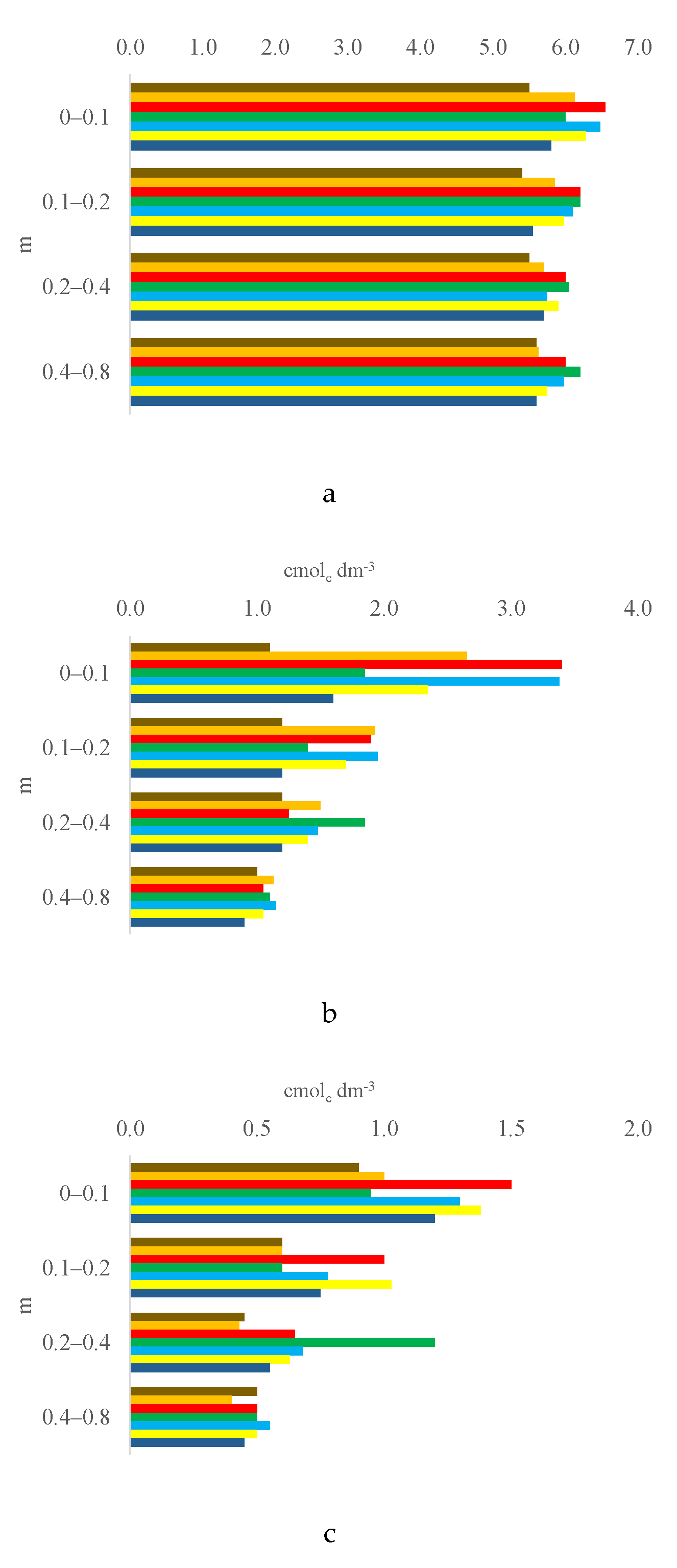

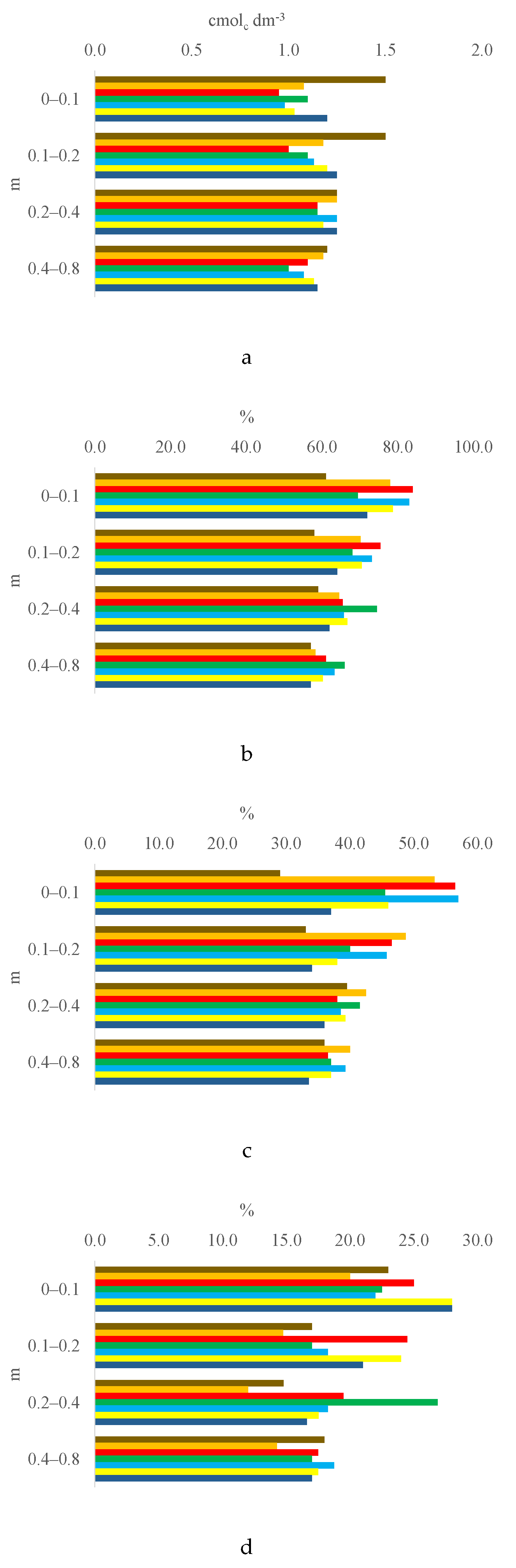

3.1. Soil Chemical Properties by Layer

3.2. Trends of Soil Characteristics by Layer and Treatment

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the Treatments on pH and Total Acidity

4.2. Effects of the Treatments on Base Saturation

4.3. Effects of the Treatments on P Content

4.4. Effects of the Treatments on K+ Content and K+/CEC

4.5. Effects of the Treatments on Ca2+ Content and Ca2+/CEC

4.6. Effects of the Treatments on Mg2+ Content and Mg2+/CEC

4.7. Effects of the Treatments on Organic Matter Content

4.8. Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BS | Base saturation |

| HL | Hydrated lime |

| LS | Limestone |

| LSD | Least significant difference |

| MaxRH | Maximum relative humidity |

| MaxT | Maximum temperature |

| MinRH | Minimum relative humidity |

| MinT | Minimum temperature |

| OM | Organic matter |

| PG | Phosphogypsum |

| R | Rainfall |

References

- Kopittke, P.M.; Menzies, N.W.; Wang, P.; McKenna, B.A.; Lombi, E. Soil and theintensification of agriculture for global food security. Environ. Int. 2019, 132, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.M.; Williamson, J.C.; Williams, A.P.; Withers, P.J.; Hockley, N.; Harris, I.M.; Hughes, J.W.; Taylor, R.L.; Jones, D.L.; Healey, J.R. Sustainable nutrient management at field, farm and regional level: Soil testing, nutrient budgets and the trade-off between lime application and greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 188, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.E.; Bennett, A.E.; Newton, A.C.; White, P.J.; McKenzie, B.M.; George, T.S.; Pakeman, R.J.; Bailey, J.S.; Fornara, D.A.; Hayes, R.C. Liming impacts on soils, crops and biodiversity in the UK: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.P.; Lopes, E.C.P.; Umburanas, R.C.; Koszalka, V.; Marcolina, E.; Ávila, F.W.; Müller, M.M.L. Long-term gypsum and top-dress nitrogen rates on black oat forage yield after maize in no-till. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 3448–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariz, C.M.; Costa, C.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Castilhos, A.M.; Meirelles, P.R.L.; Roça, R.O.; Pinheiro, R.S.B.; Kuwahara, F.A.; Martello, J.M.; Cavasano, F.A.; Yasuoka, J.I.; Sarto, J.R.W.; Melo, V.F.P.; Franzluebbers, A.J. Lamb production responses to grass grazing in a companion crop system with corn silage and oversowing of yellow oat in a tropical region. Agric. Syst. 2017, 151, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Zabaloy, M.C.; Guan, K.; Villamil, M.B. Do cover crops benefit soil microbiome? A meta-analysis of current research. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 142, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavolta, E. Manual de nutrição mineral de plantas; Ceres: São Paulo, Brasil, 2006. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Caires, E.F.; Garbuio, F.J.; Churka, S.; Barth, G.; Corrêa, J.C.L. Effects of soil acidity amelioration by surface liming on no-till corn, soybean, and wheat root growth and yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K. Efeito da calagem na produção de arroz, feijão, milho e soja em solo de cerrado. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2001, 36, 1419–1424. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, V.G.; Baker, M.T.; Segarra, E.; Brown, C.P. Integrated irrigated crop–livestock systems in dry climates. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 346−360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Joris, H.A.W.; Churka, S. Long-term effects of lime and gypsum additions on no-till corn and soybean yield and soil chemical properties in southern Brazil. Soil Use Manag. 2010, 27, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raij, B. Fertilidade do solo e manejo de nutrients; International Plant Nutrition Institute: Piracicaba, Brasil, 2011. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Crusciol, C.A.C.; Marques, R.R.; Carmeis Filho, A.C.A.; Soratto, R.P.; Costa, C.H.M.; Ferrari Neto, J.; Castro, G.S.A.; Pariz, C.M.; Castilhos, A.M.; Franzluebbers, A.J. Lime and gypsum combination improves crop and forage yields and estimated meat production and revenue in a variable charge tropical soil. Nutr. Cycling Agroecosyst. 2019, 115, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, H.J.; Cruz, F.J.R.; Pancelli, M.A.; Flores, R.A.; Vasconcelos, R.L.; Prado, R.M. Decreased potassium fertilization in sugarcane ratoons grown under straw in different soils. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2015, 9, 596−604. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, M.P.W.; Channon, P. Acid-subsoil amelioration: II. Gypsum effects on growth and subsoil chemical properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1988, 52, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Blum, J.; Barth, G.; Garbuio, F.J.; Kusman, M.T. Alterações químicas do solo e resposta da soja ao calcário e gesso aplicados na implantação do sistema de plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2003, 27, 275–286. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, K.D.; Silva, S.E.; Costa, V.F. Calcium deficiency in clayey B horizons of savannah oxisols. Soil Sci. 1982, 133, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Kusman, M.T.; Barth, G.; Garbuio, F.J.; Padilha, J.M. Alterações químicas do solo e resposta do milho à calagem e aplicação de gesso. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2004, 28, 125−136. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Barth, G.; Garbuio, F.J. Lime application in the establishment of a no-till system for grain crop production in Southern Brazil. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 89, 3−12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, W.L.B.; Hipolito, J.L.; Souza, I.M.D.; Juliano, P.H.G.; Rodrigues, L.N.F.; Andreotti, M. Methodologies for Applying Calcium Compounds in Agropastoral Systems: Changes in Soil Chemical Attributes. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascho, G.J.; Parker, M.B. Long-term liming effects on Coastal Plain soils and crops. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conyers, M.K.; Heenan, D.P.; McGhie, W.J.; Poile, G.P. Amelioration of acidity with time by limestone under contrasting tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2003, 72, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Rengel, Z.; Diatloff, E.; Gazey, C.R. Responses of wheat and barley to liming on a sandy soil with subsoil acidity. Field Crops Res. 2003, 80, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churka Blum, S.; Caires, E.F.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Lime and phosphogypsum application and sulfate retention in subtropical soils under no-till system. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2013, 13, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.C.S.; Nascente, A.S. Limestone and phosphogypsum effects on soil fertility, soybean leaf nutrition and yield. Afr. J. Agric. 2014, 9, 1366–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soratto, R.P.; Crusciol, C.A.C. Dolomite and phosphogypsum surface application effects on annual crops nutrition and yield. Agron. J. 2008, 100, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusciol, C.A C.; Artigiani, A.C.C.A.; Arf, O.; Carmeis Filho, A.C.A.; Soratto, R.P.; Nascente, A.S.; Alvarez, R.C.F. Surface application of lime–silicate–phosphogypsum mixtures for improving tropical soil properties and irrigated common bean yield. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2016, 80, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.M.; Sá, J.C.M.; Caires, E.F.; Gonçalves, D.R.P. Lime and gypsum application increase biological activity, carbon pools, and agronomic productivity in highly weathered soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 231, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeis Filho, A.C.; Penn, C.J.; Crusciol, C.A.; Calonego, J.C. Lime and phosphogypsum impacts on soil organic matter pools in a tropical Oxisol under long-term no-till conditions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.G.; Figueiredo, C.C.; Sousa, D.M.G.; Nunes, R.S.; Rein, T.A. Influence of gypsum application on sugarcane yield and soil chemical properties in the Brazilian Cerrado. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2016, 10, 1557−1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoca, S.M.; Penn, C. An important tool with no instruction manual: A review of gypsum use in agriculture. Adv. Agron. 2017, 144, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M.E. Amelioration of subsoil acidity with minimum disturbance. In Subsoil management techniques; Jayawardane, N.S., Stewart, B.A., Eds.; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, United States of America, 1995; pp. 147–185. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, F.R.; Rosa Junior, E.J.; Fietz, C.R.; Bergamin, A.C.; Rosa, Y.B.C.J.; Zeviani, W.M. Efeito do gesso nas propriedades químicas do solo sob dois sistemas de manejo; Semina: Cien. Agrar, 2012; Volume 33, pp. 1717–786 1732, (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Nora, D.; Amado, T.J.C. Improvement in chemical attributes of Oxisol subsoil and crop yields under no-till. Agron. J. 2013, 105, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, M.A.; Bingham, F.T.; Pratt, P.F. Redistribution of exchangeable calcium, magnesium and aluminum following lime and gypsum applications to a Brazilian Oxisol. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1984, 48, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, K.D.; Souza, D.M.G.; Lobato, E.; Correa, O. Calcium leaching to increase rooting depth in a Brazilian savannah Oxisol. Agron. J. 1980, 72, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Zardo Filho, R.; Barth, G.; Joris, H.A.W. Optimizing nitrogen use efficiency for no-till corn production by improving root growth and capturing NO3-N in subsoil. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosolem, C.A.; Ritz, K.; Cantarella, H.; Galdos, M.V.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Whalley, W.R.; Mooney, S.J. Enhanced plant rooting and crop system management for improved N use efficiency. Adv. Agron. 2017, 146, 205–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicensi, M.; Lopes, C.; Koszalka, V.; Umburanas, R.C.; Kawakami, J.; Pott, C.A.; Müller, M.M.L. Gypsum rates and splitting under no-till: soil fertility, corn performance, accumulated yield and profits. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicensi, M.; Lopes, C.; Koszalka, V.; Umburanas, R.C.; Vidigal, J.C.B.; Ávila, F.W.; Müller, M. M. L. Soil fertility, root and aboveground growth of black oat under gypsum and urea rates in no till. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M.E.; Shahandeh, H.; Bouton, J.; Hammel, J. Amelioration of an acid soil prolife through deep liming an surface application of gypsum. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1986, 50, 1254–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandoná, R.R.; Beutler, A.N.; Burg, G.M.; Barreto, C.F.; Schmidt, M.R. Gesso e calcário aumentam a produtividade e amenizam o efeito do déficit hídrico em milho e soja. Pesq. Agropec. Trop. 2015, 45, 128–137. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primavesi, A.C.; Primavesi, O. Características de corretivos agrícolas; Embrapa Pecuária Sudeste: São Carlos, Brasil, 2004. (Documentos, 37). (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Alcarde, J.C. Corretivos da acidez dos solos: características e interpretações técnicas; Associação Nacional para Difusão de Adubos: São Paulo, Brasil, 2005. (Boletim Técnico, 6). (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Borges, W.L.B.; Hipolito, J.L.; Tokuda, F.S.; Gasparino, A.C.; Freitas, R.S.; Andreotti, M. Methodologies for the application of calcium compounds in agropastoral systems: Effects on crop yields. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 5527–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to soil taxonomy, 12th ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Lincoln, United States of America, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Centro Integrado de Informações Agrometeorológicas - CIIAGRO. Resenha: Votuporanga no período de 01/11/2017 até 31/12/2022. Available online: http://www.ciiagro.sp.gov.br/ciiagroonline/Listagens/Resenha/LResenhaLocal.asp (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Caires, E.F.; Guimarães, A.M. A novel phosphogypsum application recommendation method under continuous no-till management in Brazil. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raij, B.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J.A.; Furlani, A.M.C. (Eds.) Recomendação de adubação e calagem para o Estado de São Paulo; Instituto Agronômico: Campinas, Brasil, 1996. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- van Raij, B.; Andrade, J.C.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J.A. (Eds.) Análise química para avaliação da fertilidade do solo; Instituto Agronômico: Campinas, Brasil, 2001. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.A.S.; Azevedo, C.A.V. The Assistat Software Version 7.7 and its use in the analysis of experimental data. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 3733–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossolani, J.W.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Merloti, L.F.; Moretti, L.G.; Costa, N.R.; Tsai, S.M.; Kuramae, E.E. Long-term lime and gypsum amendment increase nitrogen fixation and decrease nitrification and denitrification gene abundances in the rhizosphere and soil in a tropical no-till intercropping system. Geoderma 2020, 375, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, L.S. Efeito residual do calcário no solo, no estado nutricional e na produtividade da mangueira cv. Palmer. Dissertation, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Jaboticabal, Brasil, 2012. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo, A.V.; Corá, J.E.; La Scala Junior, N. Influence of liming on residual soil respiration and chemical properties in a tropical no-tillage system. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2012, 36, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirich Neto, P.H.; Caires, E.F.; Justino, A.; Dias, J. Correção da acidez do solo em função de modos de incorporação de calcário. Cienc. Rural 2000, 30, 257–261. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, W.; Coutinho, E.L.M. Avaliação da eficiência agronômica de frações granulométricas de um calcário dolomítico. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1994, 18, 55–62. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Camas-Pereyra, R.; Camas-Gómez, R.; Ramírez-Valverde, G.; Padilla-Cuevas, J.; Etchevers, J.D. Effect of gypsum and potassium on corn yield and on the exchangeable bases of an acid soil in La Frailesca, Chiapas. Agro Productividad 2022, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauletti, V.; Pierri, L.; Ranzan, T.; Barth, G.; Motta, A.C.V. Efeitos em longo prazo da aplicação de gesso e calcário no sistema de plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2014, 38, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.O.; Amado, T.J.C.; Dalla Nora, D.; Keller, C.; Bortolotto, R.P. Mudança no conteúdo de carbono en calcio em latossolo melhorado por gesso e calcário no Rio Grande Do Sul. Cienc. Suelo 2013, 31, 1–13. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E.L.; Pavan, M.A. Control of soil acidity in no-tillage system for soybean production. Soil Tillage Res. 1996, 38, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, J.C.; Meda, A.R.; Cassiolato, M.E.; Miyazawa, M.; Pavan, M.A. Potencial de extratos de resíduos vegetais na mobilização do calcário no solo por métodos biológicos. Sci. Agric. 2001, 58, 357–360. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrere, C.; Anghinoni, I. Alteração de atributos químicos no perfil do solo pela calagem superficial em campo nativo. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2001, 25, 885–895. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, J.C.A.; Villas Bôas, R.L.; Lima, E.V.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Büll, L.T. Alterações nos atributos químicos de um Latossolo distroférrico decorrentes da granulometria e doses de calcário em sistemas de plantio direto e convencional. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2003, 27, 553–561. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foloni, J.S.S.; Rosolem, C.A. Efeito da calagem e sulfato de amônio no algodão: I - Transporte de cátions e ânions no solo. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2006, 30, 425–432. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.P.C.; Cassol, L.C.; Anghinoni, I.; Carvalho, P.C.F. Atributos químicos do solo em função da aplicação superficial de calcário em sistema de integração lavoura-pecuária submetido a pressões de pastejo em plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2008, 32, 2385–2396. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C.; Jones, C.A. Growth and mineral nutrition of field crops; CRC Press: Boca Raton, United States of America, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Butterly, C.R.; Baldock, J.A.; Tang, C. The contribution of crop residues to changes in soil pH under field conditions. Plant Soil 2013, 366, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, W.L.B.; Andreotti, M.; Cruz, L.C.P.; Oliveira, D.Y.O.; Borges, J.F.; Silva, L. C. Changes in soil chemical attributes in an agrosilvopastoral system six years after thinning of eucalyptus. Plants 2024, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caires, E.F.; Chueiri, W.A.; Madruga, E.F.; Figueiredo, A. Alterações de características químicas do solo e resposta da soja ao calcário e gesso aplicados na superfície em sistema de cultivo sem preparo de solo. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1998, 22, 27–34. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Fonseca, A.F.; Mendes, J.; Chueiri, W.A.; Madruga, E. F. Produção de milho, trigo e soja em função das alterações das características químicas do solo pela aplicação de calcário e gesso na superfície, em sistema plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1999, 23, 315–327. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöttker, D.; Ben, J.R. Calagem para uma rotação de culturas no sistema plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1998, 22, 675–684. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinheimer, D.S.; Santos, E.J.S.; Kaminski, J.; Bortoluzzi, E.C.; Gatiboni, L. C. Alterações de atributos do solo pela calagem superficial e incorporada a partir de pastagem natural. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2000, 24, 797–805. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, S.G.; Kiehl, J.C.; Prochnow, L.I.; Pauletti, V. Calagem em sistema de semeadura direta e efeitos sobre a acidez do solo, disponibilidade de nutrientes e produtividade de milho e soja. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2001, 25, 71–81. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotta, M.N.; Bayer, C.; Ernani, P.R.; Fontoura, S.M.V.; Albuquerque, J.A.; Wobeto, C. Acidificação de um Latossolo sob plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2002, 26, 1055–1064. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; Pavan, M.A.; Franchini, J.C. Evaluation of plant residues on the mobility of surface applied lime. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2002, 45, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhardt, W.C. The basic cation saturation ratio concept and lime and potassium recommendations an Delaware's Coastal Plain soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1981, 45, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, A.A.B.B. Efeito residual da aplicação de gesso na eficiência da adubação fosfatada para a sucessão trigo-soja em sistema plantio direto; Dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa: Ponta Grossa, Brasil, 2017. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.A.S.; Faquin, V.; Guelfi, D.R.; Oliveira, G.C.; Bastos, C.E.A. Acúmulo de macronutrientes na soja influenciado pelo cultivo prévio do capim-marandu, correção e compactação do solo. Rev. Cienc. Agron. 2012, 43, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Joris, H.A.W.; Churka, S. Long-term effects of lime and gypsum additions on no-till corn and soybean yield and soil chemical properties in southern Brazil. Soil Use Manag. 2011, 27, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Maschietto, E.H.G.; Garbuio, F.J.; Churka, S.; Joris, H.A.W. Surface application of gypsum in low acidic Oxisol under no-till cropping system. Sci. Agric. 2011, 68, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selles, F.; Kochann, R.A.; Denardin, J.E.; Zentner, R.P.; Faganello, A. Distribution of phosphorus fractions in a Brazilian Oxisol under different tillage systems. Soil Tillage Res. 1997, 44, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetto, S.L. Eficiência da adubação fosfatada influenciada pela aplicação de gesso agrícola em sistema plantio direto. Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa, Brasil, 2016. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, J.C.; Mauad, M.; Rosolem, C.A. Fósforo no solo e desenvolvimento de soja influenciados pela adubação fosfatada e cobertura vegetal. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2004, 39, 1231–1237. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.J. Manejo do solo e efeito residual da gessagem sobre atributos físicos e químicos de um Latossolo Vermelho distroférrico e no desenvolvimento da soja. Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul: Dourados, Brasil, 2006. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Sá, J.C.M. Impacto do aumento da matéria orgânica do solo em atributos da fertilidade no sistema plantio direto. In 5º Encontro regional de plantio direto no cerrado; Campo Grande, Brasil, 10-13 July 2001. (In Portuguese)

- Eltz, F.L.F.; Peixoto, R.T.G.; Jaster, F. Efeitos de sistemas de preparo do solo nas propriedades físicas e químicas de um Latossolo Bruno álico. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1989, 13, 259–267. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepker, D.; Anghinoni, I. Características físicas e químicas do solo afetadas por métodos de preparo e modos de adubação. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1995, 19, 395–401. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, C.; Mielniczuk, J. Características químicas do solo afetadas por métodos de preparo e sistemas de cultura. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1997, 21, 105−112. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Rheinheimer, D.S.; Kaminski, J.; Lupatini, G.C.; Santos, E.J.S. Modificações em atributos químicos de solo arenoso sob sistema plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1998, 22, 713–721. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleiro, R.M.; Souza, C.M.; Silva, C.S.W.; Sediyama, C.S.; Silva, A.A.; Fagundes, J.L. Influência dos sistemas de preparo nas propriedades químicas e físicas do solo. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2003, 27, 1097–1104. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.L.R.; Pereira, M.G. Dinâmica do potássio nos resíduos vegetais de plantas de cobertura no cerrado. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2008, 32, 1609–1618. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.C. Suprimento e assimilabilidade de fósforo e potássio. In Natureza e propriedade dos solos, 7th ed.; Brady, N. C., Ed.; Freitas Bastos: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1989; pp. 373–413. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, I.R.; Souza, C.M.; Borém, A.; Silva, G.F. Variação dos valores de pH e dos teores de carbon orgânico, cobre, manganês, zinco e ferro em profundidade em Argissolo Vermelho-Amarelo, sob diferentes sistemas de preparo de solo. Bragantia 2003, 62, 119–126. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, W.L.B.; Freitas, R.S.; Mateus, G.P.; Sá, M.E.; Alves, M.C. Absorção de nutrientes e alterações químicas em Latossolos cultivados com plantas de cobertura em rotação com soja e milho. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2014, 38, 252−261. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, G.P.; Guerra, J.G.M.; Monteiro, M.T.; de-Polli, H.; Teixeira, M.G. Perennial herbaceous legumes as live soil mulches and their effects on C, N and P of the microbial biomass. Sci. Agric. 2003, 60, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed-Omar, S.R.; Sumner, M.E. Effect of gypsum on soil potassium and magnesium status and growth of alfalfa. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1991, 22, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola Junior, E.; Pavan, M.A. Seletividade de troca de cátions em solos ácidos. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 1989, 13, 131–138. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Zambrosi, F.C.B.; Alleoni, L.R.F.; Caires, E.F. Teores de alumínio trocável e não trocável após calagem e gessagem em Latossolo sob sistema plantio direto. Bragantia 2007, 66, 487–495. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.G.; Sousa, D.M.G.; Figueiredo, C.C.; Rein, T.A.; Nunes, R.S.; Santos Júnior, J.D.G. The residual effect of gypsum on subsoil conditioning, nutrition and productivity of sugarcane crops. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2018, 12, 1313−1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicensi, M.; Umburanas, R.U.; Loures, F.S.R.; Koszalka, V.; Botelho, R.V.; Ávila, F.W.; Müller, M.M.L. Residual effect of gypsum and nitrogen rates on black oat regrowth and on succeeding soybean under no-till. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2021, 15, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.J.K.; Palm, C.A.; Cuevas, E.; Gunatilleke, I.U.N.; Brossard, M. The synchronisation of nutrient mineralisation and plant nutrient demand. In The biological management of tropical soil fertility; Woomer, P. L., Swift, M. J., Eds.; Wiley-Sayce Publications: London, England, 1994; pp. 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Domanski, G. Carbon input by plants into the soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2000, 163, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.E. Uso de gesso como insumo agrícola; Embrapa - Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Biologia: Cascavel, Brasil, 1992. (Comunicado Técnico 7). (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.C.S.; van Raij, B. Calcium sulphate, phosphogypsum and calcium carbonate in the amelioration of acid subsoild for root growth. Plant Soil 1997, 192, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soratto, R.P.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Castro Mello, F.F. Componentes da produção e produtividade de cultivares de arroz e feijão em função de calcário e gesso aplicados na superfície do solo. Bragantia 2010, 69, 965–974. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, W.L.B.; Hipolito, J.L.; Cruz, L.C.P.; Souza, I.M.D.; Sporch, H.B.S.; Juliano, P.H.G.; Rodrigues, L.N.F. Evaluation of the influence of surface and subsurface acidity correction methodologies on soil compaction in agropastoral systems under no-till. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2024, 88, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | 2017-2018 season | 2018-2019 season | 2019-2020 season | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS | PG | HL | LS | PG | HL | LS | PG | HL | |

| kg ha-1 - | |||||||||

| T1 (control) | |||||||||

| T2 | 2,000 1 | 2,500 1 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| T3 | 1,000 2 + 1,350 1 | 1,500 1 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | |||

| T4 | 1,000 2 + 1,350 1 | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| T5 | 2,500 1 | 725 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | |||

| T6 | 2,500 1 | 450 4 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| T7 | 2,500 1 | 260 4 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Attribute | Treatment5 | F test | LSD6 | CV7 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | |||||||||||

| P (resin), mg dm-3 | 31.00 | c 8 | 50.00 | ab | 35.50 | bc | 31.50 | c | 57.00 | a | 46.00 | abc | 43.50 | abc | 8.6352** | 15.63 | 15.92 |

| S-SO42-, mg dm-3 | 4.00 | ab | 3.25 | b | 3.50 | ab | 4.50 | a | 3.00 | b | 3.25 | b | 3.00 | b | 5.1639** | 1.15 | 14.06 |

| Organic matter, g dm-3 | 14.00 | bc | 14.75 | abc | 17.00 | a | 13.00 | c | 15.75 | ab | 14.75 | abc | 16.50 | ab | 5.8246** | 2.72 | 7.71 |

| pH 1 | 5.50 | e | 6.13 | bcd | 6.55 | a | 6.00 | cd | 6.48 | ab | 6.28 | abc | 5.80 | de | 17.9692** | 0.41 | 2.88 |

| K+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.35 | a | 0.24 | bc | 0.13 | cd | 0.10 | d | 0.24 | ab | 0.24 | b | 0.30 | ab | 13.8536** | 0.11 | 20.94 |

| Ca2+, cmolc dm-3 | 1.10 | c | 2.65 | ab | 3.40 | a | 1.85 | bc | 3.38 | a | 2.35 | ab | 1.60 | bc | 10.8351** | 1.24 | 22.85 |

| Mg2+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.90 | b | 1.00 | ab | 1.50 | a | 0.95 | b | 1.30 | ab | 1.38 | ab | 1.20 | ab | 4.4962** | 0.51 | 18.50 |

| Total acidity 2 | 1.50 | a | 1.08 | bc | 0.95 | c | 1.10 | bc | 0.98 | c | 1.03 | c | 1.20 | b | 33.0000** | 0.15 | 5.86 |

| Base saturation, % 3 | 61.00 | c | 78.00 | ab | 84.00 | a | 69.50 | bc | 83.00 | a | 78.75 | ab | 72.00 | b | 13.0757** | 10.59 | 6.03 |

| CEC pH 7.0, cmolc dm-3 4 | 3.85 | b | 4.96 | ab | 5.98 | a | 4.00 | b | 5.89 | a | 4.99 | ab | 4.30 | b | 6.2932** | 1.60 | 14.09 |

| K+/CEC, % | 9.09 | a | 4.74 | c | 2.09 | d | 2.45 | d | 4.15 | c | 4.82 | c | 6.85 | b | 45.9236** | 1.68 | 14.77 |

| Ca2+/CEC, % | 29.00 | d | 53.25 | ab | 56.50 | ab | 45.50 | bc | 57.00 | a | 46.00 | abc | 37.00 | cd | 18.9931** | 11.18 | 10.34 |

| Mg2+/CEC, % | 23.00 | ab | 20.00 | b | 25.00 | ab | 22.50 | ab | 22.00 | ab | 28.00 | a | 28.00 | a | 4.5491** | 6.70 | 11.92 |

| Attribute | Treatment5 | F test | LSD6 | CV7 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | |||||||||||

| P (resin), mg dm-3 | 17.00 | d 8 | 35.00 | b | 27.50 | c | 31.00 | bc | 47.25 | a | 36.25 | b | 34.50 | b | 66.7845** | 5.26 | 6.91 |

| S-SO42-, mg dm-3 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.50 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.25 | 3.50 | 1.3125 | 0.83 | 10.96 | |||||||

| Organic matter, g dm-3 | 11.00 | bc | 11.75 | abc | 12.50 | ab | 10.00 | c | 11.50 | bc | 12.25 | abc | 14.00 | a | 6.2964** | 2.34 | 8.45 |

| pH 1 | 5.40 | c | 5.85 | ab | 6.20 | a | 6.20 | a | 6.10 | a | 5.98 | a | 5.55 | bc | 14.2299** | 0.39 | 2.84 |

| K+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 1.7563 | 0.22 | 30.14 | |||||||

| Ca2+, cmolc dm-3 | 1.20 | 1.93 | 1.90 | 1.40 | 1.95 | 1.70 | 1.20 | 3.4500* | 0.85 | 22.63 | |||||||

| Mg2+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.60 | b | 0.60 | b | 1.00 | a | 0.60 | b | 0.78 | ab | 1.03 | a | 0.75 | ab | 5.6134** | 0.36 | 20.41 |

| Total acidity 2 | 1.50 | a | 1.18 | b | 1.00 | c | 1.10 | bc | 1.13 | bc | 1.20 | b | 1.25 | b | 20.6033** | 0.16 | 5.81 |

| Base saturation, % 3 | 58.00 | c | 70.25 | ab | 75.50 | a | 68.00 | ab | 73.25 | a | 70.50 | ab | 64.00 | bc | 103486** | 8.58 | 5.36 |

| CEC pH 7.0, cmolc dm-3 4 | 3.59 | 3.98 | 4.10 | 3.47 | 4.23 | 4.27 | 3.50 | 2.7690* | 0.97 | 10.77 | |||||||

| K+/CEC, % | 8.08 | 6.89 | 4.88 | 10.66 | 9.06 | 8.21 | 8.58 | 2.4738 | 5.36 | 28.52 | |||||||

| Ca2+/CEC, % | 33.00 | b | 48.75 | a | 46.50 | ab | 40.00 | ab | 45.75 | ab | 38.00 | ab | 34.00 | b | 4.6271** | 13.61 | 14.26 |

| Mg2+/CEC, % | 17.00 | bc | 14.75 | c | 24.50 | a | 17.00 | bc | 18.25 | abc | 24.00 | ab | 21.00 | abc | 5.4504** | 7.49 | 16.45 |

| Attribute | Treatment5 | F test | LSD6 | CV7 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | |||||||||||

| P (resin), mg dm-3 | 11.00 | c 8 | 29.25 | ab | 21.00 | b | 21.00 | b | 28.25 | ab | 35.75 | a | 33.00 | a | 16.6239** | 9.74 | 16.28 |

| S-SO42-, mg dm-3 | 4.00 | a | 3.50 | ab | 3.50 | ab | 3.50 | ab | 3.00 | b | 3.00 | b | 3.00 | b | 3.7895* | 0.91 | 11.57 |

| Organic matter, g dm-3 | 8.50 | b | 10.50 | a | 10.50 | a | 11.00 | a | 10.00 | a | 10.25 | a | 11.00 | a | 9.0741** | 1.32 | 5.53 |

| pH 1 | 5.50 | 5.70 | 6.00 | 6.05 | 5.75 | 5.90 | 5.70 | 2.6771* | 0.552 | 4.08 | |||||||

| K+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.14 | b | 0.35 | a | 0.28 | ab | 0.27 | ab | 0.32 | ab | 0.32 | ab | 0.31 | ab | 2.8399* | 0.19 | 28.60 |

| Ca2+, cmolc dm-3 | 1.20 | b | 1.50 | ab | 1.25 | ab | 1.85 | a | 1.48 | ab | 1.40 | ab | 1.20 | b | 2.8965* | 0.63 | 19.23 |

| Mg2+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.45 | b | 0.43 | b | 0.65 | b | 1.20 | a | 0.68 | b | 0.63 | b | 0.55 | b | 15.8692** | 0.30 | 19.94 |

| Total acidity 2 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.25 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 0.5646 | 0.31 | 10.93 | |||||||

| Base saturation, % 3 | 59.00 | b | 64.50 | ab | 65.50 | ab | 74.50 | a | 65.75 | ab | 66.75 | ab | 62.00 | b | 4.2858** | 10.82 | 7.08 |

| CEC pH 7.0, cmolc dm-3 4 | 3.04 | b | 3.52 | b | 3.33 | b | 4.47 | a | 3.72 | b | 3.52 | b | 3.31 | b | 8.9719** | 0.71 | 8.51 |

| K+/CEC, % | 4.52 | 9.79 | 8.41 | 5.94 | 8.70 | 9.31 | 9.33 | 2.4484 | 5.93 | 31.76 | |||||||

| Ca2+/CEC, % | 39.50 | 42.50 | 38.00 | 41.50 | 38.50 | 39.25 | 36.00 | 0.9628 | 10.34 | 11.27 | |||||||

| Mg2+/CEC, % | 14.79 | b | 12.01 | b | 19.49 | ab | 26.86 | a | 18.27 | b | 17.53 | b | 16.60 | b | 7.6373** | 7.84 | 18.72 |

| Ca2+/ECEC, %e | 67.20 | a | 65.93 | ab | 57.44 | c | 55.82 | c | 58.41 | bc | 59.53 | abc | 58.31 | bc | 6.5697** | 8.00 | 5.68 |

| Attribute | Treatment5 | F test | LSD6 | CV7 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | |||||||||||

| P (resin), mg dm-3 | 2.00 | c 8 | 8.00 | b | 9.00 | b | 9.00 | b | 6.50 | b | 7.00 | b | 15.00 | a | 31.3140** | 3.24 | 17.17 |

| S-SO42-, mg dm-3 | 3.00 | 4.25 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.25 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 2.0959 | 2.18 | 24.17 | |||||||

| Organic matter, g dm-3 | 7.00 | c | 8.00 | b | 8.50 | ab | 8.00 | b | 8.25 | ab | 8.25 | ab | 9.00 | a | 13.8889** | 0.76 | 4.02 |

| pH 1 | 5.60 | b | 5.63 | b | 6.00 | ab | 6.20 | a | 5.98 | ab | 5.75 | ab | 5.60 | b | 4.6100** | 0.52 | 3.81 |

| K+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.08 | d | 0.13 | cd | 0.21 | b | 0.34 | a | 0.15 | bcd | 0.16 | bcd | 0.16 | bc | 23.5443** | 0.08 | 19.47 |

| Ca2+, cmolc dm-3 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 2.3861 | 0.26 | 10.41 | |||||||

| Mg2+, cmolc dm-3 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 1.1287 | 0.21 | 18.43 | |||||||

| Total acidity 2 | 1.20 | a | 1.18 | a | 1.10 | ab | 1.00 | b | 1.08 | ab | 1.13 | ab | 1.15 | ab | 4.3846** | 0.15 | 5.75 |

| Base saturation, % 3 | 57.00 | b | 58.25 | b | 61.00 | ab | 66.00 | a | 63.25 | ab | 60.25 | ab | 57.00 | b | 5.9591** | 6.42 | 4.55 |

| CEC pH 7.0, cmolc dm-3 4 | 2.78 | ab | 2.83 | ab | 2.86 | ab | 2.94 | a | 2.93 | ab | 2.83 | ab | 2.66 | b | 2.7145* | 0.27 | 4.05 |

| K+/CEC, % | 2.88 | c | 4.43 | bc | 7.18 | b | 11.56 | a | 5.26 | bc | 5.54 | bc | 6.06 | b | 19.4631** | 2.91 | 20.30 |

| Ca2+/CEC, % | 36.00 | 40.00 | 36.50 | 37.00 | 39.25 | 37.00 | 33.50 | 2.4325 | 6.42 | 7.42 | |||||||

| Mg2+/CEC, % | 18.00 | 14.25 | 17.50 | 17.00 | 18.75 | 17.50 | 17.00 | 0.9315 | 6.84 | 17.08 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).