Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Ultrasonic Applications

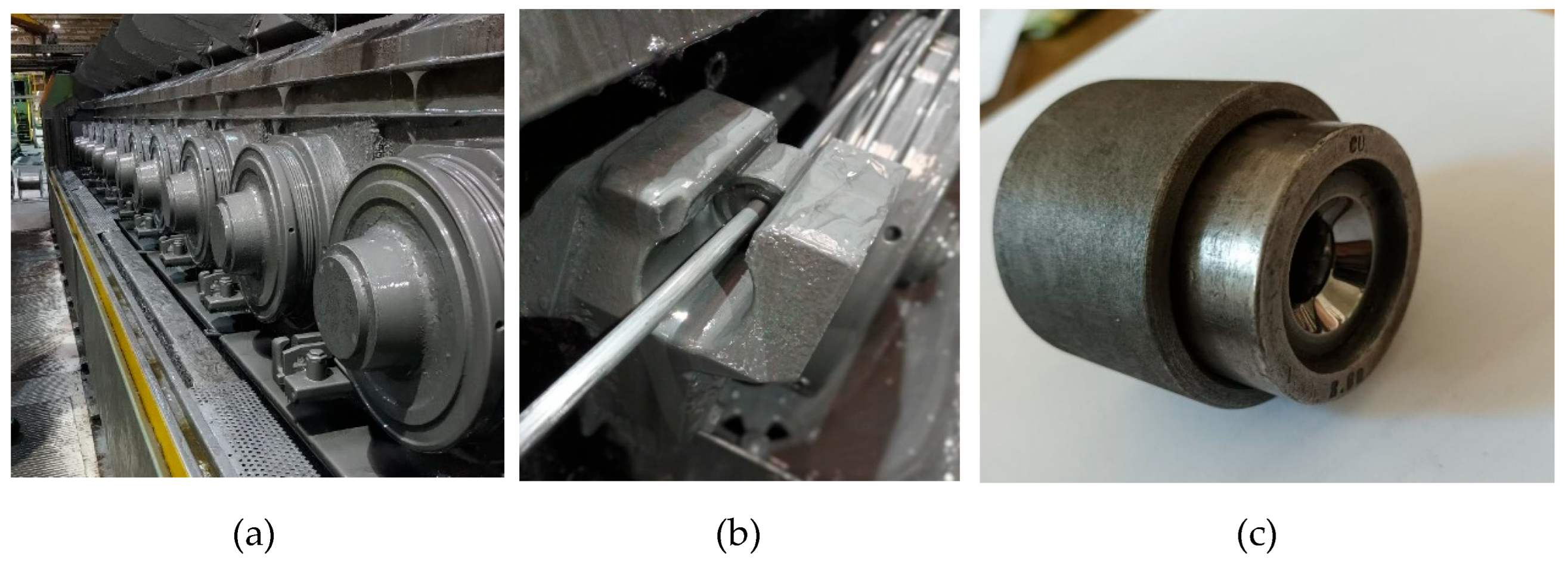

1.2. Wire Drawing

2. Design of the Ultrasonic Transducer to Activate the Drawing Die

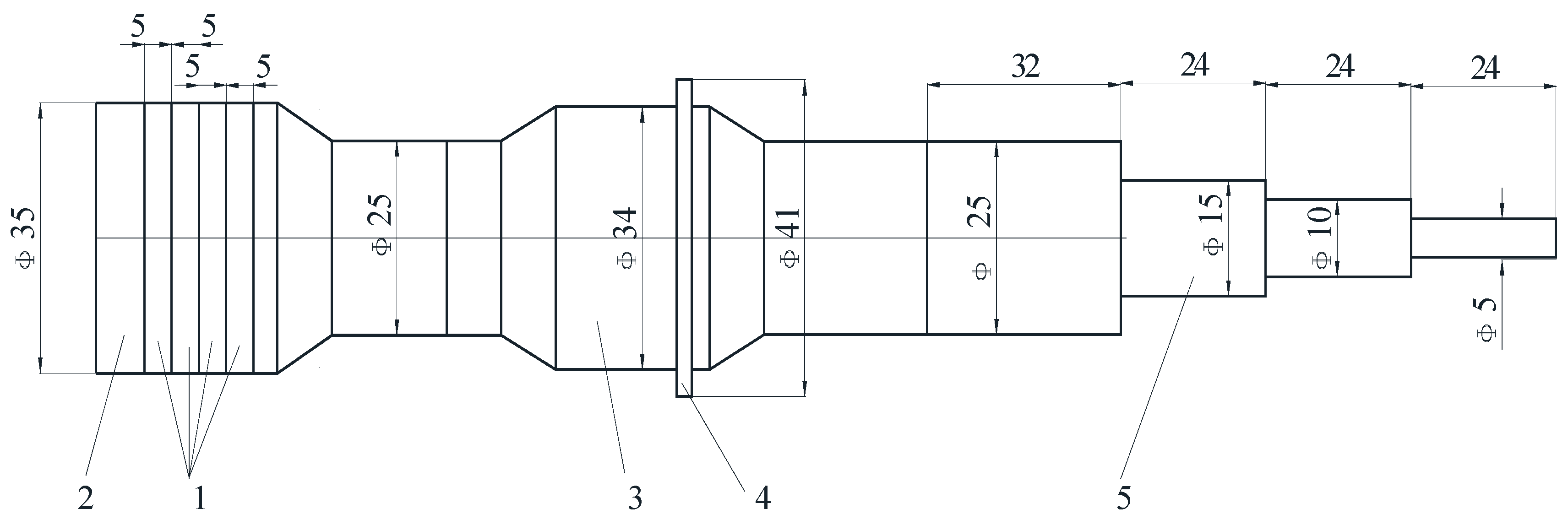

2.1. Analytical Dimensional Design of the Ultrasonic Transducer

| - material permittivity - [F/m] | (1) |

| - resonance frequency - f0 = 35000 Hz | (2) |

| - resonance pulsation - | (3) |

| - particle displacement - ξ= 0.5 · 10-7 m | (4) |

| - input electrical power - Pin = 1500 W | () |

| - acoustic intensity [33,34] - = 4.8W/m2 | () |

| - the acousto-mechanical efficiency [35,36] - = 0.8 | (7) |

| - the electromechanical coupling factor - [37,38] – ζ = 0.75 | (8) |

| - the electroacoustic efficiency [35,36] - ηea = 0.95 | (9) |

| - piezoceramic material density [39] - [Kg/m3] | (10) |

| - piezoceramic material Young modulus [39] - [N/m2] | () |

| - piezoceramic material Poisson coefficient [40] – ν = 0.25 | (12) |

| - the relative permittivity [41] at 1 Hz - | (13) |

| - loss angle - δp = 0.73 deg ; tg (δp) = 0.0127 | (14) |

| - piezoelectric constant [m/V] | (15) |

| - steel Young modulus - [N/m2] | (16) |

| - steel density - [Kg/m3] | (17) |

| - steel Poisson coefficient ν = 0.3 | (18) |

| - aluminium density - [Kg/m3] | (19) |

| - aluminium Poisson coefficient - ν = 0.33 | (20) |

- -

- ultrasound propagation speed [42] through piezoceramic elements - vp, with formula 21.

- -

- the radius of the resulting piezoceramic active element (for the circular section), is rp:

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- length of ultrasonic energy concentrator

- -

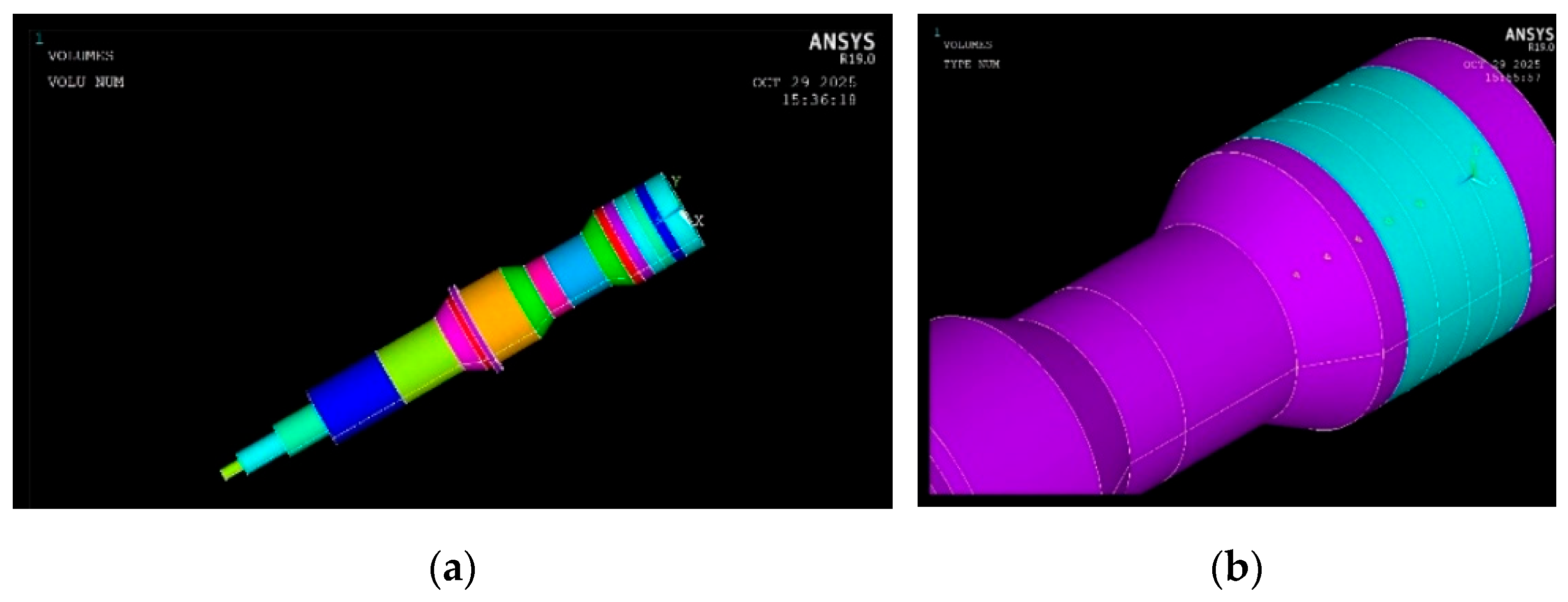

2.2. Analysis of the Optimal Vibration Modes of the Ultrasonic System Used to Activate the Wire Drawing Dies

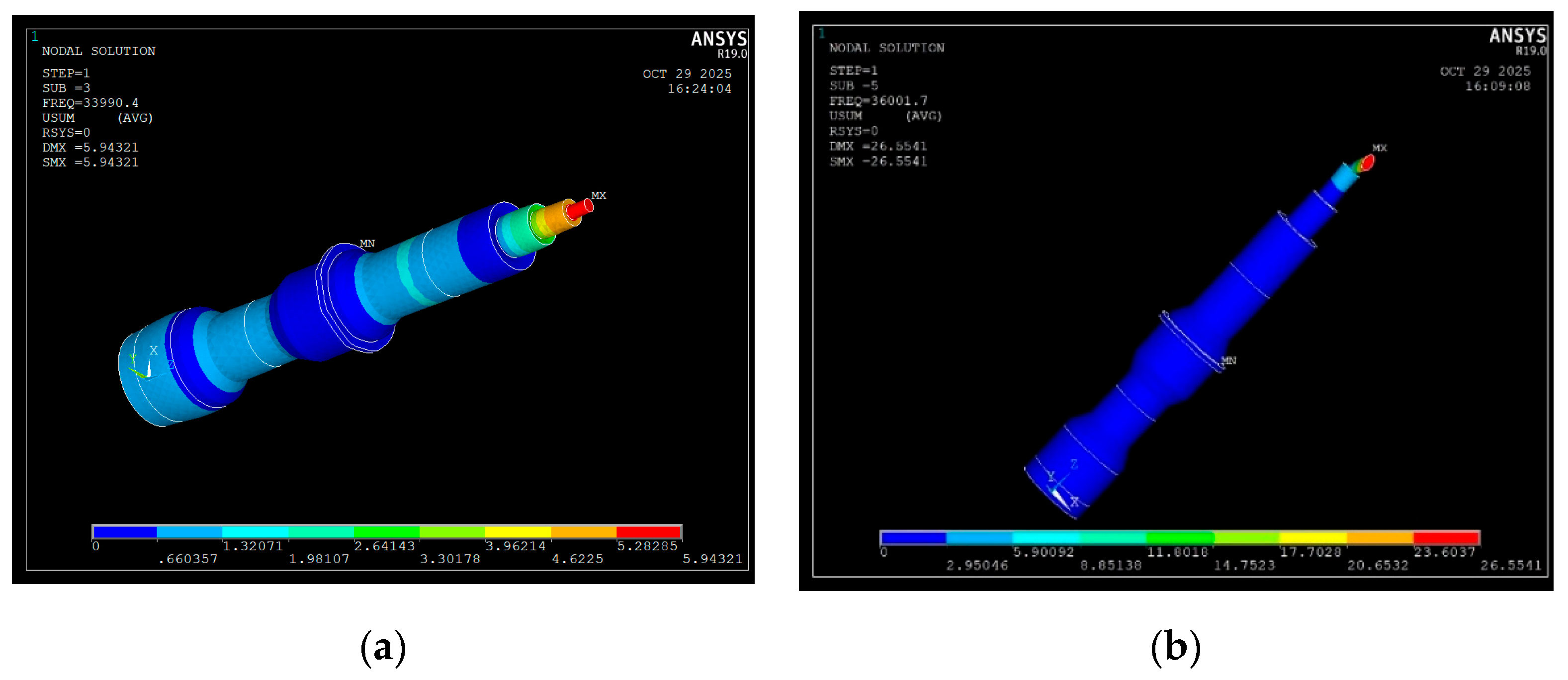

2.3. Displacement Calculation of the Ultrasonic System Using FEM at f = 33990 Hz

2.4. Mechanical Stress Calculation of the Ultrasonic Transducer Using FEM at f = 33990 Hz

2.4.1. Calculation on the OX, OY and OZ Mechanical Stress

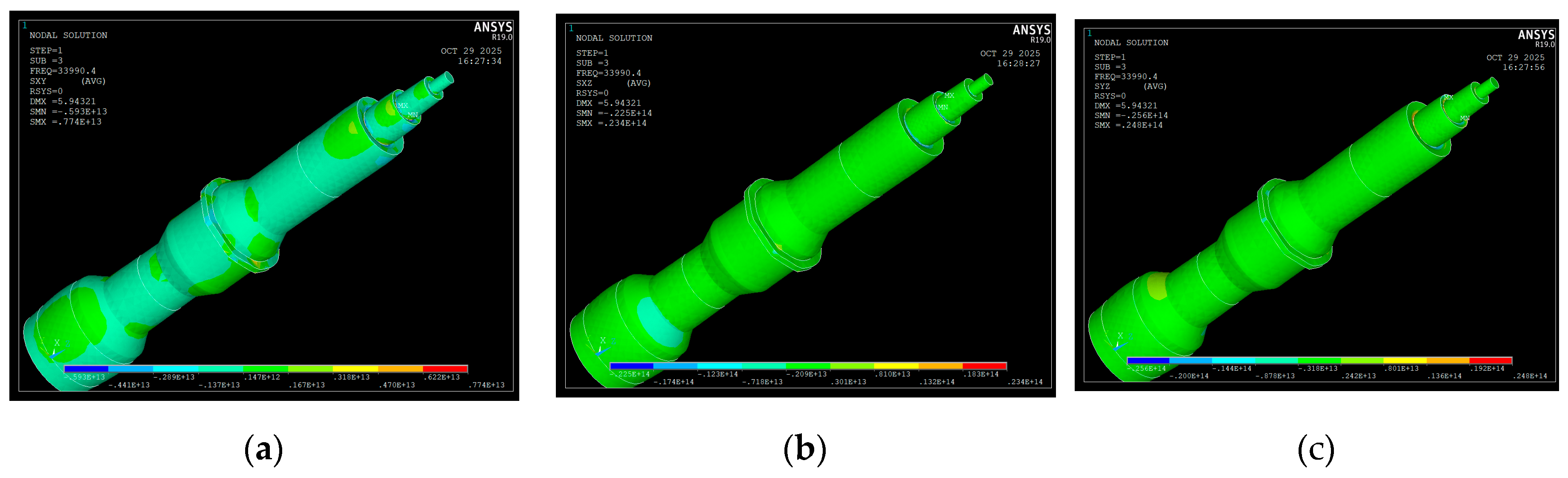

2.4.2. Calculation of the Shear Mechanical Stress on the Orthogonal Planes

2.4.3. Calculation of the S1, S2, S3 Mechanical Stress

3. Experiments on Reducing Friction Force During Drawing in an Ultrasonic Field

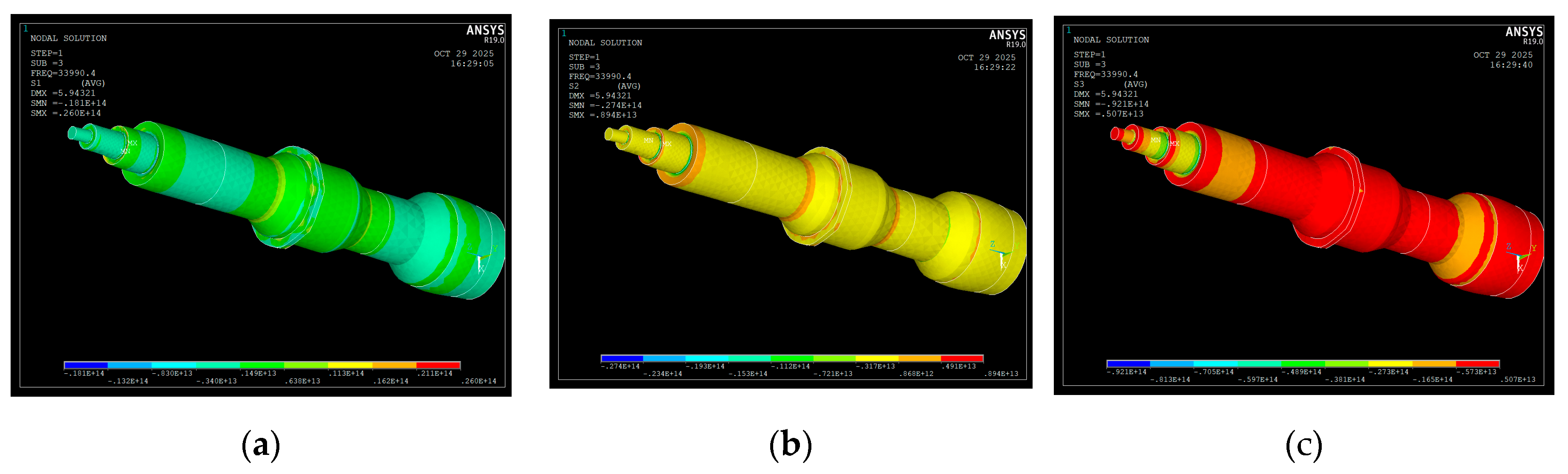

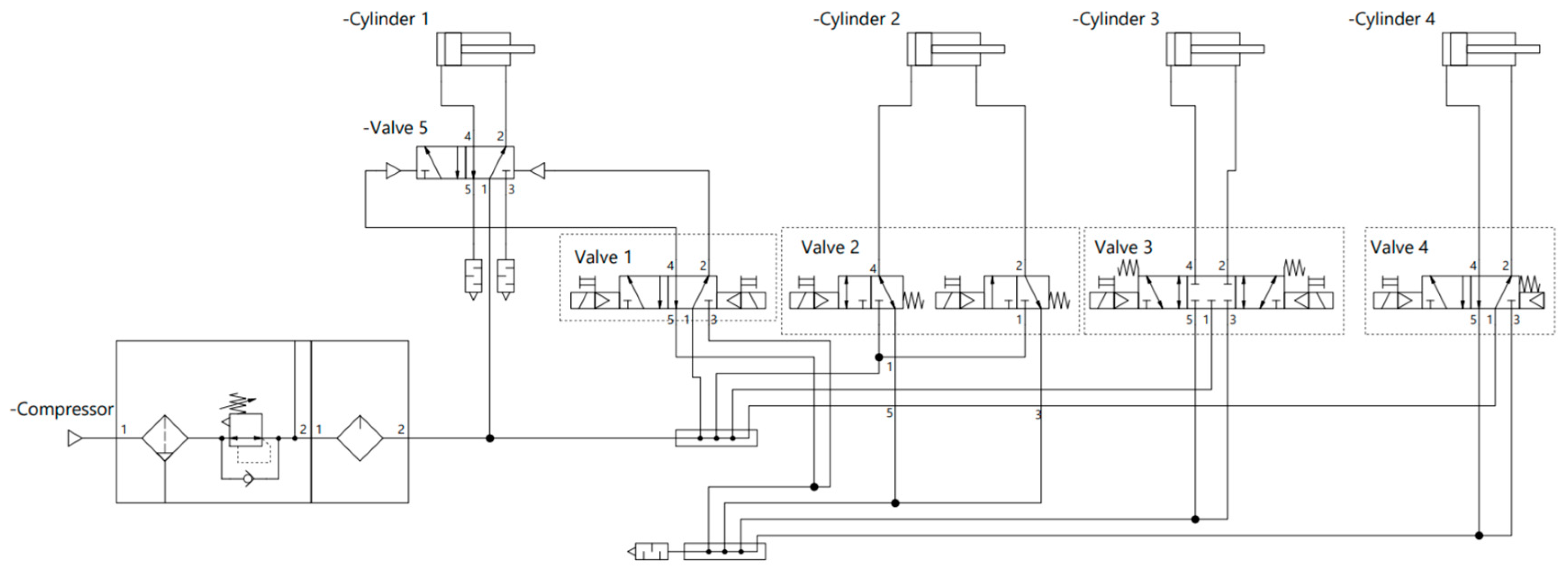

3.1. General Information About the Use of Pneumatic Stands

3.1.2. Pneumatic Stand Description

- Pneumatic supply & actuators - compressor, FRL (filter-regulator-lubricator), valves and multiple cylinders (various diameters and strokes).

- Sensor layer - digital position sensors (magnetic/Hall), analog airflow and pressure sensors, plus optional vibration sensors.

- Control layer - RSTi-EP PACSystem (real-time logic, valve actuation) connected to a BUS coupler and I/O modules.

- Edge & data layer - Rxi2-LP edge controller hosting Node-RED flows, InfluxDB for time-series storage and Grafana for visualization. Data transport between nodes uses direct I/O, PROFINET and optional MQTT gateways.

- -

- -pneumatic cylinder -1

- -

- -air filter and lubricant - 3

- -

- pneumatic 5/2 distributor - 5

- -

- -valve system and IOT interface module - 10

- -

- magnetic proximity sensors at the end of each cylinder. Their purpose is to transmit the relative position of the piston rod in the cylinder -2

- -

- analog air flow monitor - 4

- -

- a two-channel vibration sensor is used. The entire device contains a box with the brain and its power supply through 6 AA batteries. Two wires with one sensor attached at the end of each come out of it - 9

- -

- I/O modules, 2 analogic, 1 digital - 12

- -

- Wi-Fi Micro Gateway for MQTT Wireless receiver and transmitter box - 6

- -

- PACedge - 7

- -

- Edge Controller - 8

3.2. Experiments on the Realization of the Wire Drawing Process in Ultrasonic Field

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- an analytical calculation model of the main characteristics of the ultrasonic system;

- -

- based on this, the geometric design of the ultrasonic system was carried out, which includes the stepped shape of the ultrasonic energy concentrator;

- -

- the geometry thus defined constituted the model for carrying out a modal analysis based on FEM, through which the vibration modes were determined at the working frequencies found by the mathematical method; following this analysis, it was found that one of the two vibration frequencies, namely f = 33900 Hz, is very close to the vibration frequency of the piezoceramic elements used in the analytical calculation, f = 35000 Hz. The mathematical model aimed to determine the amplitude of vibrations and the state of stress as long-term operation of the ultrasonic system is necessary.

- -

- experiments on drawing under the action of the ultrasonic field at the vibration frequency f = 33940Hz, also very close to that determined by FEM, namely f = 33900 Hz.

- -

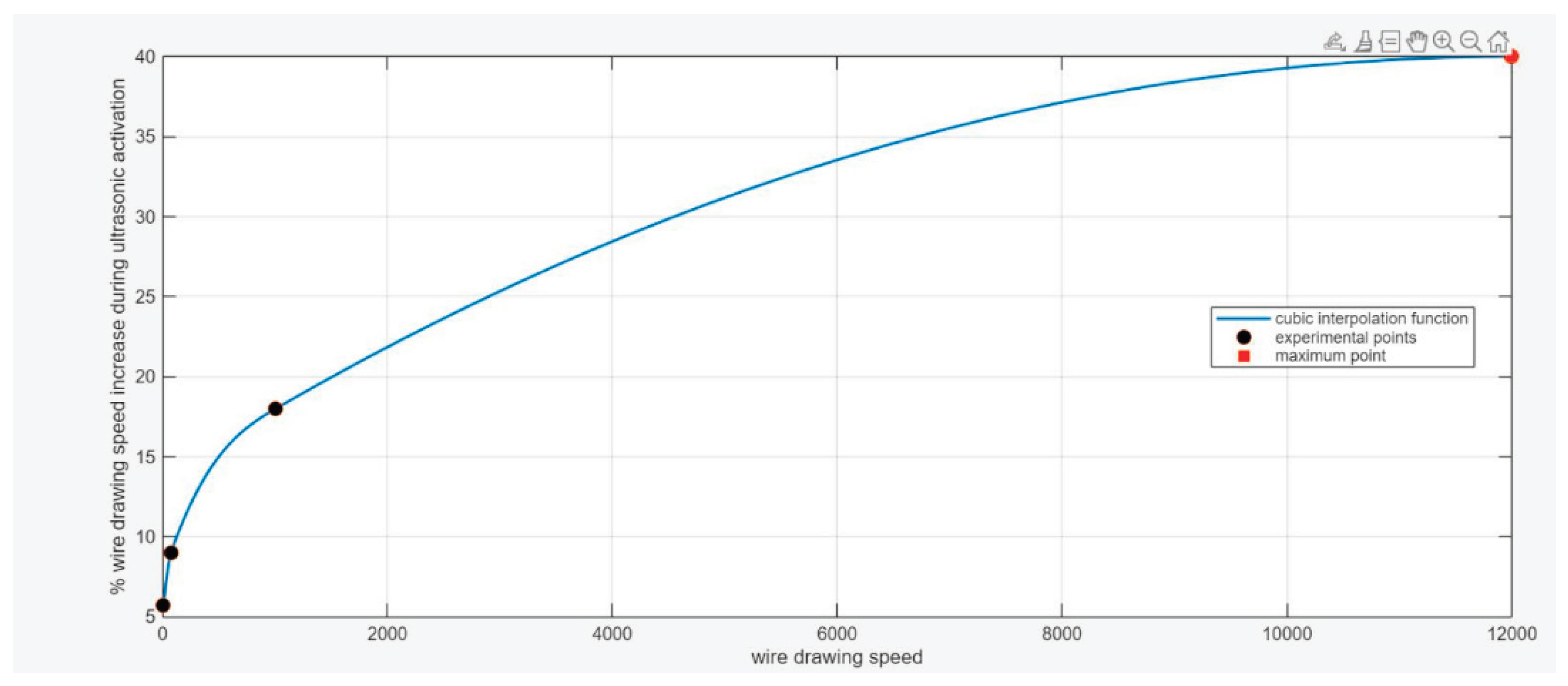

- increase in the drawing speed, when applying the ultrasonic field, in different percentages depending on the different working speeds used.

Acknowledgments

References

- Heywang, W.; Lubitz, K., Wersing, W., Piezoelectricity: evolution and future of a technology. Vol. 114. Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

- Eitel, R. E.; Shrout, T. R.; Randall, C. A. Nonlinear contributions to the dielectric permittivity and converse piezoelectric coefficient in piezoelectric ceramics. Journal of Applied Physics, 2006, 99. [CrossRef]

- Rupitsch, S. J.; Ilg, J. Complete characterization of piezoceramic materials by means of two block-shaped test samples. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 2015, vol. 62, pp. 1403-1413. [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Juarez, J. A. Piezoelectric ceramics and ultrasonic transducers. J. Phys E: Sci. Instrum. 1989, Volume 22. [CrossRef]

- Chandra Sekhar, B.; Dhanalakshmi, B.; Srinivasa, R.; S., Ramesh, K.; Prasad, V.; Subba Rao, P.S.V.; Parvatheeswara Rao, B. Multifunctional Ferroelectric Materials. Piezoelectricity and its applications, 2021.

- Aabid, A.; Raheman, M.A.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Anjum, A.; Hrairi, M.; Parveez, B.; Parveen, N.; Mohammed Zayan, J. A. Systematic Review of Piezoelectric Materials and Energy Harvesters for Industrial Applications. Sensors, 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Aabid, A.; Parveez, B.; Raheman, A.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Anjum, A.; Hrairi, M.; Parveen, N.; Zayan, J.M. A review of piezoelectric materials based structural control and health monitoring techniques for engineering structures: Challenges and opportunities. Actuators, 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Weavers, C.; K.; Hoffmann, M., R. Chemical Bubble Dynamics and Quantitative Sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 6927-6934. [CrossRef]

- Suslick, K. The Chemical Effects of Ultrasound. Scientific American, 1989, 260, 80-87.

- Trevena, D. H. Ultrasonic waves in liquids. Contemporary physics, 2006, 10, 601-614. [CrossRef]

- Muthupandian, A. The characterization of acoustic cavitation bubbles – An overview. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 2011, 18, 864-872. [CrossRef]

- https://www.hielscher.com/ultrasonic-cavitation-in-liquids-2.htm (22 03 2025).

- Pingqing, F.; Keshuai, Z. Mechanical analysis of the contact interface of standingwave linear piezoelectric driver. Journal: AIP Advances, 2020, Volume 10, 015054. [CrossRef]

- Hanlu, L.; Weihao, R.; Lin, Y.; Chengcheng, M.; Siyu, T.; Ruijia, Y. Tunable-focus liquid lens actuated by a novel piezoelectric motor. J. Mechanical Engineering Science, 2021, Volume 235, 4337. [CrossRef]

- Jiangbo, H.; Yu, C.; Binlei, C.; Xiaoshi, L.; Tianyu, Y.; Zongda, H.; Longqi, R.; Wu, Z., J. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 2023, 189, 110083.

- Jun, L.; Jao, L.; Tao, L.; Lihua, Z.; Xingrong, C.; Guoqun, Z.; Yanjin, G. Evaluation of friction reduction and frictionless stress in ultrasonic vibration forming process. J. Materials Processing Technology, 2021, 288. [CrossRef]

- Storck, H.; Littmann, W.; Wallaschek, J.; Mracek, M. The effect of friction reduction in presence of ultrasonic vibrations and its relevance to travelling wave ultrasonic motors. Ultrasonics, 2002, 40, 379-383. [CrossRef]

- Sednaoui, T.; Vezzoli, E.; Dzidek, B.; Lemaire-Semail, B.; Chappaz, C.; Adams, M. Friction Reduction Through Ultrasonic Vibration Part 2: Experimental Evaluation of Intermittent Contact and Squeeze Film Levitation. IEEE Transactions on Haptics. 2017, 10.,109. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.M.; Twiefel, J. Ultrasonic friction reduction in elastomer - Metal contacts and application to pneumatic actuators. Physics Procedia, 2015, 70 , 55-58. [CrossRef]

- Torres, D.; A,; Vezzoli, E.; Lemaire-Semail, B.; Adams, M.; Giraud-Audine, C.; Giraud, F.; Amberg, M. Mechanisms of friction reduction in longitudinal ultrasonic surface haptic devices with non-collinear vibrations and finger displacement. https://lilloa.univ-lille.fr/bitstream/handle/20.500.12210/61756/LFrictionReduction_Vf.pdf.

- Dong, S.; Dapino; M. Experiments on Ultrasonic Lubrication Using a Piezoelectrically-assisted Tribometer and Optical Profilometer. J. Vis Exp. 2015. 103. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, D.; Marcelo, J. D. Elastic–plastic cube model for ultrasonic friction reduction via Poisson's effect. Ultrasonics, 2014, 54, 343-350. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.C.; Hutchings, I.M. Reduction of the sliding friction of metals by the application of longitudinal or transverse ultrasonic vibration. Tribology International, 2004, 37, 833-840. [CrossRef]

- Takashi, J.; Yukio, K.; Nobuyoshi, I.; Osamu, M.; Eiji, M.; Katsuhiko, I.; Hajime, H. An application of ultrasonic vibration to the deep drawing process. J. Materials, Processing Technology, 1998, 80–81, 406-412. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L.; Wu, C.S.; Shi, L. Analysis of friction reduction effect due to ultrasonic vibration exerted in friction stir welding, J. Manufacturing Processes. 2018, 35, 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Littmann, W.; Heiner, S.; Wallaschek, J. Reduction of friction using piezoelectrically excited ultrasonic vibrations, Smart Structures and Materials, Damping and Isolation, 2001, 4331. [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Roy, A.; Lingxi, G.; Jianfeng, X.; Silberschmidt, V. Analytical prediction of shear angle and frictional behaviour in vibration-assisted cutting. J. of Manufacturing Processes, 2021, 62, 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Sednaoui, T.; Vezzoli, E.; Dzidek, B.; Lemaire-Semail, P.; Chappaz, C.; Adams, M. Experimental evaluation of friction reduction in ultrasonic devices, IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC), Evanston, IL, USA, 37-42, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, E. Friction Reduction through Ultrasonic Vibration Part 1: Modelling Intermittent Contact. IEEE Transactions on Haptics, 2017, 10, 196-207. [CrossRef]

- Amza, Gh. Sisteme ultraacustice, Publising House. Tehnica, Bucuresti, 1991.

- Amza, Gh. Actuatori electromecanici neconvenţionali, Publising House, Bucureşti, 2002.

- Heywang, W.; Lubitz, K.; Wersing, W. Piezoelectricity: evolution and future of a technology, Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

- https://www.ndt.net/ndtaz/files/ut_formula/ut_formula.php.

- Law, H.H.; Rossiter, P.L.; Simon, G.P.; Koss, L.L. Characterization of mechanical vibration damping by piezoelectric materials, J. of Sound and Vibration, 1996, 197, 489-513. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, F. Measurement of ultrasonic power and electro-acoustic efficiency of high power transducers. Ultrasonics, 2000, Jan;37(8):549-54. PMID: 11243458. [CrossRef]

- Banno, H.; Masamura, Y. N.; Naruse, Acoustic load dependency of electroacoustic efficiency in the electrostrictive ultrasonic transducer and acoustical matching, Ultrasonics, Volume 17, Issue 2, 1979, Pages 63-66, ISSN 0041-624X. [CrossRef]

- Lustig, S.; Elata, D. Ambiguous definitions of the piezoelectric coupling factor, Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures. 2020, 31(14):1689-1696. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y. Y.; Liu, L.; Leng, H., Li, H.; Wang, X.; Priya,Y. Jeba, S. Near-ideal electromechanical coupling in textured piezoelectric ceramics, Nature Communications. 13. [CrossRef]

- Gowdhaman, P. Annamalai, V.; Thakur, O.P. Piezo, ferro and dielectric properties of ceramic-polymer composites of 0-3 connectivity, Ferroelectrics, 2016, 120-129. [CrossRef]

- Jianjun, W.; Weijie, L.; Chengming, L., Peijun, W. Effective determination of Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of metal using piezoelectric ring and electromechanical impedance technique: A proof-of-concept study, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2021, 319. [CrossRef]

- https://www.americanpiezo.com (11 05 2025).

- https://www.nde-ed.org/NDETechniques/Ultrasonics/CalibrationMeth/standreferences.xhtml (11 05 2025).

| Sx [N/m2] |

SY [N/m2] |

Sz [N/m2] |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodal flange | -0.38 E13 – 0.93 E12 | -0.38 E13 – 0.1 E13 | -0.63 E13 – 0.43 E13 |

| Piezoceramic elementes | -0.38 E13 – 0.93 E12 | -0.38 E13 – 0.1 E13 | -0.63 E13 – 0.43 E13 |

| Sxy [N/m2] |

Sxz [N/m2] |

Syz [N/m2] |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodal flange | -0.13 E13 – 0.16 E13 | -0.2 E13 – 0.3 E13 | -0.31 E13 – 0.24 E13 |

| Piezoceramic elementes | -0.13 E13 – 0.14 E12 | -0.2 E13 – 0.3 E13 | -0.31 E13 – 0.24 E13 |

| S1 [N/m2] |

S2 [N/m2] |

S3 [N/m2] |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodal flange | -0.14 E13 – 0.63 E13 | -0.31E13 – 0.86 E13 | -0.57 E13 – 0.5 E13 |

| Piezoceramic elementes | -0.14 E13 – 0.63 E13 | -0.31E13 – 0.86 E13 | -0.57 E13 – 0.5 E13 |

| Test No. | Drawing speed without cooling liquid lubrication [mm/s] |

Drawing speed with cooling liquid lubrication [mm/s] |

Drawing speed with cooling liquid lubrication with application of ultrasonic field (ultrasonic lubrication) [mm/s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 43.3 | 51.81 51.81 51.81 |

54.38 |

| 2. | 54.67 | ||

| 3. | 55.26 | ||

| 4. | 95.5 95.5 95.5 |

104.31 | |

| 5. | 105.9 | ||

| 6. | 104.82 | ||

| 7. | 1005 | 1214 | |

| 8. | 1005 | 1214.9 | |

| 9. | 1005 | 1215.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).