Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

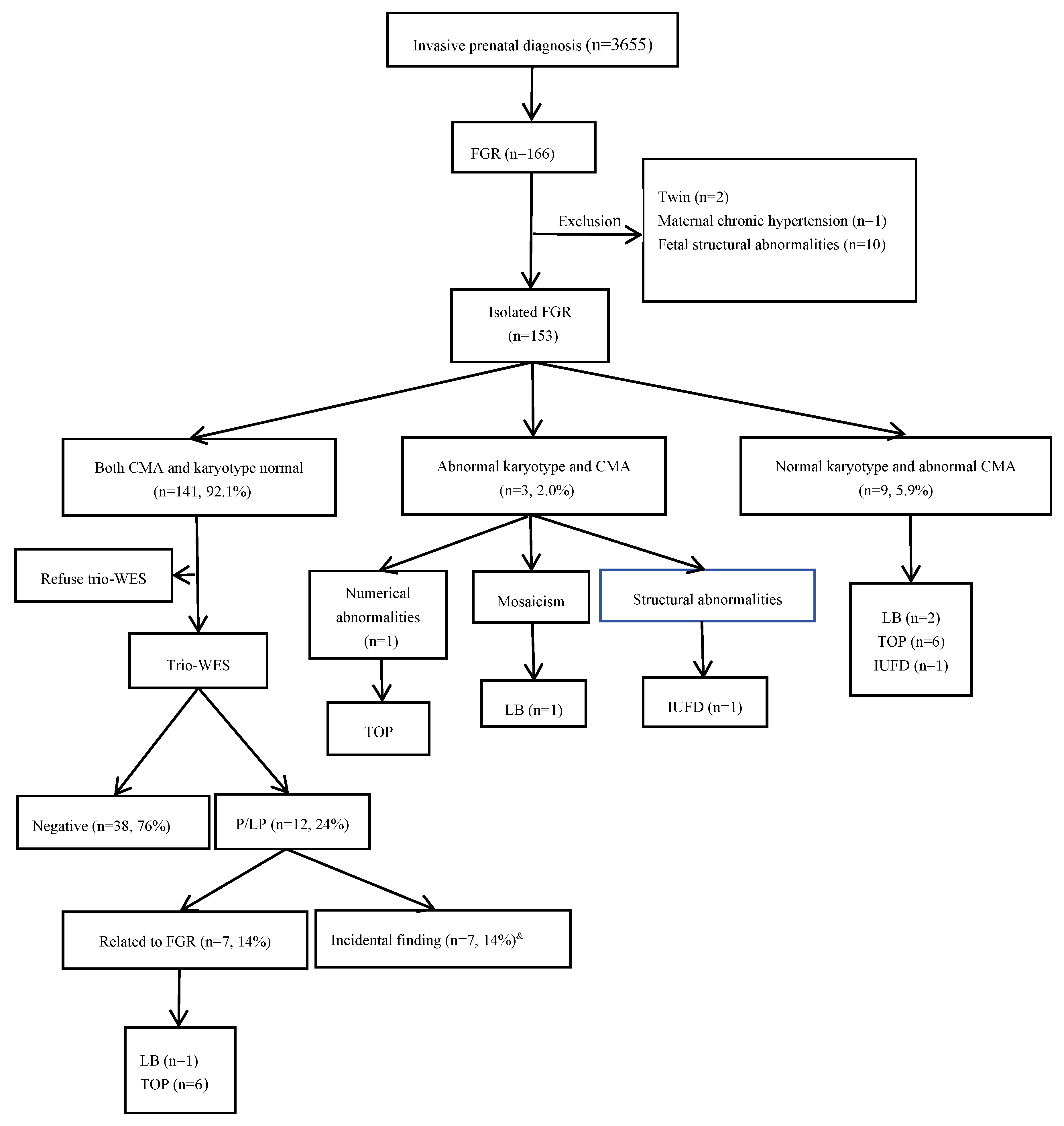

2.1. Patient Enrollment

2.2. Aminotic Fluid Sampling and DNA Extraction

2.3. CMA and Trio-WES

3. Results

3.1. Chromosomal Karyotype and Chromosomal Microarray Analysis Results.

3.2. Results of Trio-WES

3.3. Pregnancy Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FGR | Fetal Growth Restriction |

| CMA | chromosomal microarray analysis |

| WES | whole exome sequencing |

| CNVs | copy number variations |

| UPD | uniparental disomy |

| SNVs | single nucleotide variants |

| P | pathogenic |

| LP | likely pathogenic |

| B | benign |

| LB | likely benign |

| VUS | variant of uncertain significance |

| GA | gestational age |

| LB | live born |

| TOP | termination of pregnancy |

| IUFD | Intrauterine fetal demise |

| Mat. | maternal |

| Pat. | paternal |

| AD | autosomal dominant |

| AR | autosomal recessive |

| IC | imprinting center |

| MS-MLPA | Methylation-Specific Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| STR | short tandem repeat |

References

- Visentin, S.; Londero, A.P.; Cataneo, I.; Bellussi, F.; Salsi, G.; Pilu, G.; Cosmi, E. A prenatal standard for fetal weight improves the prenatal diagnosis of small for gestational age fetuses in pregnancies at increased risk. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Martins JG, Biggio JR, Abuhamad A: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #52: Diagnosis and management of fetal growth restriction: (Replaces Clinical Guideline Number 3, April 2012). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020, 223(4):B2-b17.

- Kingdom, J.; Ashwal, E.; Lausman, A.; Liauw, J.; Soliman, N.; Figueiro-Filho, E.; Nash, C.; Bujold, E.; Melamed, N. Guideline No. 442: Fetal Growth Restriction: Screening, Diagnosis, and Management in Singleton Pregnancies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2023, 45, 102154. [CrossRef]

- King, V.J.; Bennet, L.; Stone, P.R.; Clark, A.; Gunn, A.J.; Dhillon, S.K. Fetal growth restriction and stillbirth: Biomarkers for identifying at risk fetuses. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 959750. [CrossRef]

- Chew LC, Osuchukwu OO, Reed DJ, Verma RP: Fetal Growth Restriction. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Allotey, J.; Archer, L.; Coomar, D.; Snell, K.I.; Smuk, M.; Oakey, L.; Haqnawaz, S.; Betrán, A.P.; Chappell, L.C.; Ganzevoort, W.; et al. Development and validation of prediction models for fetal growth restriction and birthweight: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Heal. Technol. Assess. 2024, 28, 1–119. [CrossRef]

- Adam-Raileanu, A.; Miron, I.; Lupu, A.; Bozomitu, L.; Sasaran, M.O.; Russu, R.; Rosu, S.T.; Nedelcu, A.H.; Salaru, D.L.; Baciu, G.; et al. Fetal Growth Restriction and Its Metabolism-Related Long-Term Outcomes—Underlying Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 555. [CrossRef]

- D'Agostin, M.; Morgia, C.D.S.; Vento, G.; Nobile, S. Long-term implications of fetal growth restriction. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 2855–2863. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, S.; Shen, Q.; Xu, S.; Guo, D.; Liang, B.; Wang, X.; Cao, H.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. Etiologic evaluation and pregnancy outcomes of fetal growth restriction (FGR) associated with structural malformations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, U.; Bhalerao, S. Placental Insufficiency and Fetal Growth Restriction. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2011, 61, 505–511. [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska BA, Pankiewicz K, Nowacka U, Niemiec M, Kozłowski S, Issat T: Genetic Background of Fetal Growth Restriction. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23(1).

- Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Huang, L.; He, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, Q.; Luo, Y. Application of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis of fetal growth restriction. Prenat. Diagn. 2016, 36, 686–692. [CrossRef]

- Borrell, A.; Grande, M.; Meler, E.; Sabrià, J.; Mazarico, E.; Muñoz, A.; Rodriguez-Revenga, L.; Badenas, C.; Figueras, F. Genomic Microarray in Fetuses with Early Growth Restriction: A Multicenter Study. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2017, 42, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Snijders, R.; Sherrod, C.; Gosden, C.; Nicolaides, K. Fetal growth retardation: Associated malformations and chromosomal abnormalities. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 168, 547–555. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Shi, L.; Zeng, S.; Zhuang, J.; Lyu, G. The Genetic Etiology Diagnosis of Fetal Growth Restriction Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism-Based Chromosomal Microarray Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, L.G.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Dabell, M.P.; Coppinger, J.; Bandholz, A.M.; Ellison, J.W.; Ravnan, J.B.; Torchia, B.S.; Ballif, B.C.; Fisher, A.J. Detection rates of clinically significant genomic alterations by microarray analysis for specific anomalies detected by ultrasound. Prenat. Diagn. 2012, 32, 986–995. [CrossRef]

- Levy B, Wapner R: Prenatal diagnosis by chromosomal microarray analysis. Fertil Steril 2018, 109(2):201-212.

- Ganapathi, M.; Nahum, O.; Levy, B. Prenatal Diagnosis Using Chromosomal SNP Microarrays. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1885:187-205. [CrossRef]

- Wapner, R.J.; Martin, C.L.; Levy, B.; Ballif, B.C.; Eng, C.M.; Zachary, J.M.; Savage, M.; Platt, L.D.; Saltzman, D.; Grobman, W.A.; et al. Chromosomal Microarray versus Karyotyping for Prenatal Diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2175–2184. [CrossRef]

- Committee Opinion No. 581: the use of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol 2013, 122(6):1374-1377.

- Borrell, A.; Grande, M.; Pauta, M.; Rodriguez-Revenga, L.; Figueras, F. Chromosomal Microarray Analysis in Fetuses with Growth Restriction and Normal Karyotype: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2017, 44, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Lantieri, F.; Malacarne, M.; Gimelli, S.; Santamaria, G.; Coviello, D.; Ceccherini, I. Custom Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization: the Importance of DNA Quality, an Expert Eye, and Variant Validation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 609. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cerveira, E.; Romanovitch, M.; Zhu, Q. Array-Based Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH). Methods Mol Biol 2017, 1541:167-179. [CrossRef]

- Dugoff, L.; Norton, M.E.; Kuller, J.A. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, B2–B9. [CrossRef]

- Sagi-Dain, L.; Peleg, A.; Sagi, S. Risk for chromosomal aberrations in apparently isolated intrauterine growth restriction: A systematic review. Prenat. Diagn. 2017, 37, 1061–1066. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, S.; Shen, Q.; Xu, S.; Guo, D.; Liang, B.; Wang, X.; Cao, H.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. Etiologic evaluation and pregnancy outcomes of fetal growth restriction (FGR) associated with structural malformations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Lin, Y.; Xu, L.P.; Huang, H.L.; Liu, S.P.; Yu, Y.H.; Yang, F. Application of chromosomal microarray to investigate genetic causes of isolated fetal growth restriction. Mol. Cytogenet. 2018, 11, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Luo, D.; Lian, J.; She, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhong, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, H. Chromosomal Abnormalities Detected by Chromosomal Microarray Analysis and Karyotype in Fetuses with Ultrasound Abnormalities. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, ume 17, 4645–4658. [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Li, L.S.; Du, K.; Li, R.; Yu, Q.X.; Wang, D.; Lei, T.Y.; Deng, Q.; Nie, Z.Q.; Zhang, W.W.; et al. [Analysis of families with fetal congenital abnormalities but negative prenatal diagnosis by whole exome sequencing].. 2021, 56, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Mellis, R.; Oprych, K.; Scotchman, E.; Hill, M.; Chitty, L.S. Diagnostic yield of exome sequencing for prenatal diagnosis of fetal structural anomalies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenat. Diagn. 2022, 42, 662–685. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Fu, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Cheng, K.; Huang, R.; Wang, D.; Yu, Q.; Lu, Y.; et al. Genetic causes of isolated and severe fetal growth restriction in normal chromosomal microarray analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 161, 1004–1011. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Huang, Y.; Ding, H.; Zhao, L.; He, W.; Wu, J. Utility of whole exome sequencing in the evaluation of isolated fetal growth restriction in normal chromosomal microarray analysis. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2476038. [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 405–424. [CrossRef]

- Leone, G.; Meli, C.; Falsaperla, R.; Gullo, F.; Licciardello, L.; La Spina, L.; Messina, M.; Bianco, M.L.; Sapuppo, A.; Pappalardo, M.G.; et al. Maternal Phenylketonuria and Offspring Outcome: A Retrospective Study with a Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2025, 17, 678. [CrossRef]

- Gautiero, C.; Scala, I.; Esposito, G.; Coppola, M.R.; Cacciapuoti, N.; Fisco, M.; Ruoppolo, M.; Strisciuglio, P.; Parenti, G.; Guida, B. The Light and the Dark Side of Maternal PKU: Single-Centre Experience of Dietary Management and Emergency Treatment Protocol of Unplanned Pregnancies. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, V.; Longo, N. Phenylketonuria and the brain. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139. [CrossRef]

- Rohde, C.; Thiele, A.G.; Baerwald, C.; Ascherl, R.G.; Lier, D.; Och, U.; Heller, C.; Jung, A.; Schönherr, K.; Joerg-Streller, M.; et al. Preventing maternal phenylketonuria (PKU) syndrome: important factors to achieve good metabolic control throughout pregnancy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M.A.; O'DOnnell-Luria, A.; Almontashiri, N.A.; AlAali, W.Y.; Ali, H.H.; Levy, H.L. Classical phenylketonuria presenting as maternal PKU syndrome in the offspring of an intellectually normal woman. JIMD Rep. 2023, 64, 312–316. [CrossRef]

- Donarska, J.; Szablewska, A.W.; Wierzba, J. Maternal Phenylketonuria: Consequences of Dietary Non-Adherence and Gaps in Preconception Care—A Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1102. [CrossRef]

- Lazier, J.; Martin, N.; Stavropoulos, J.D.; Chitayat, D. Maternal uniparental disomy for chromosome 6 in a patient with IUGR, ambiguous genitalia, and persistent mullerian structures. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2016, 170, 3227–3230. [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.M.; Butler, M.G. The 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 Microdeletion Syndrome: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 4068–4082. [CrossRef]

- Gruchy, N.; Decamp, M.; Richard, N.; Jeanne-Pasquier, C.; Benoist, G.; Mittre, H.; Leporrier, N. Array CGH analysis in high-risk pregnancies: comparing DNA from cultured cells and cell-free fetal DNA. Prenat. Diagn. 2011, 32, 383–388. [CrossRef]

- Oneda, B.; Baldinger, R.; Reissmann, R.; Reshetnikova, I.; Krejci, P.; Masood, R.; Ochsenbein-Kölble, N.; Bartholdi, D.; Steindl, K.; Morotti, D.; et al. High-resolution chromosomal microarrays in prenatal diagnosis significantly increase diagnostic power. Prenat. Diagn. 2014, 34, 525–533. [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, T.; Zerres, K.; Eggermann, K.; Moore, G.; Wollmann, H.A. Uniparental disomy: clinical indications for testing in growth retardation. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2002, 161, 305–312. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hao, N.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, H.; Dai, Y.; Wang, M.; Bai, J.; Lv, Y.; Qi, Q.; Zhou, X. Contribution of uniparental disomy to fetal growth restriction: a whole-exome sequencing series in a prenatal setting. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, T. Human Reproduction and Disturbed Genomic Imprinting. Genes 2024, 15, 163. [CrossRef]

- Yingjun, X.; Zhiyang, H.; Linhua, L.; Fangming, S.; Linhuan, H.; Jinfeng, T.; Qianying, P.; Xiaofang, S. Chromosomal uniparental disomy 16 and fetal intrauterine growth restriction. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 211, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.C.; Lau, W.L.; Lo, T.K.; Lau, T.K.; Lam, Y.Y.; Kan, A.; Chan, K.; Lau, E.T.; Tang, M.H. Two IUGR foetuses with maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 6 or UPD(6)mat. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 37, 113–115. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J.A.; Coe, B.P.; Eichler, E.E.; Cuckle, H.; Shaffer, L.G. Estimates of penetrance for recurrent pathogenic copy-number variations. Anesthesia Analg. 2013, 15, 478–481. [CrossRef]

- Scuffins, J.; Keller-Ramey, J.; Dyer, L.; Douglas, G.; Torene, R.; Gainullin, V.; Juusola, J.; Meck, J.; Retterer, K. Uniparental disomy in a population of 32,067 clinical exome trios. Anesthesia Analg. 2021, 23, 1101–1107. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, M.; Gu, T.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Peng, J. Chromosomal microarray analysis for prenatal diagnosis of uniparental disomy: a retrospective study. Mol. Cytogenet. 2024, 17, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Yu, A.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Guo, Q.; Lin, M.; Lin, N.; Chen, X.; Xu, L.; Huang, H. Genetic testing for fetal loss of heterozygosity using single nucleotide polymorphism array and whole-exome sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- O’brien, M.; Whyte, S.; Doyle, S.; McAuliffe, F.M. Genetic disorders in maternal medicine. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 97, 102546. [CrossRef]

| Case number | GA#(weeks) | Karyotype | CMA results/size | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | mos 45,X[[6]/46,XX[94] | arr[X]x1~2 | LB |

| 2 | 18 | 47,XN.+21 | arr[21]x3 | TOP |

| 3 | 22 | 46,XY.del(11)(q24.2) | arr[GRCh37]11q24.2q25(127699535-137937416)x1/10.2Mb | IUFD |

| Case number | GA# (Weeks) |

CMA results | Type of aberration/size |

Inheritance | Classification | Syndrome | Pregnancy outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 22 | arr[GRCh37]16p13.3p12.2(94808-22768821)x2hmz | UPD/22.7Mb | De novo | P | Segmental UPD(16) | LB, 37w5d,BW 1660g,normal development at 3-year-old follow-up |

| 5 | 22 | arr[GRCh37]14q12(32297119-33263470)×1 | del/966.4kb | De novo | LP | / | IUFD |

| 6 | 30 | arr[GRCh37]1q43q44(240983677-245476176)x1 | del/4.5Mb | De novo | P | 1q43-q44 microdeletion syndrome, Mental retardation AD 22 syndrome |

TOP |

| 7 | 22 | arr[GRCh37]17p12(14099565-15428902)x3 | dup/1.3Mb | Maternal | P | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type1A(CMT1A)(OMIM 118220) | LB, 34w3d, BW 1830g, hypospadias, preeclampsia |

| 8 | 22 | arr[GRCh37] Xp22.33p22.31(168552-6387288)x1 | del/ 6.2 Mb |

De novo | p | Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis (OMIM 127300) / X-linked chondrodysplasia punctata (CDPX1)(OMIM 302950) |

TOP |

| 9 | 26 | upd(6)mat.arr[GRCh37] 6p22.3p21.1(156975-43855790)x2htz, 6p21.1q21(43855791-107691648) x2hmz, 6q21q27(107691649-170914297)x2htz* | Maternal UPD | De novo | P | UPD(6)mat | TOP |

| 10 | 29 | arr[GRCh37]15q13.2q13.3(31042916_32509926)x1 | del/1.5Mb | De novo | P | 15q13.3 deletion syndrome | TOP |

| 11 | 18 | arr[GRCh37]19q13.11q13.12(33044716-37930875)x1 | del/4.9Mb | De novo | P | / | TOP |

| 12 | 24 | arr[GRCh37]15q11.2(22770422-23082237)x1 | del/312Kb | De novo | P | 15q11.2 deletion syndrome (OMIM 615656) | LB, 39w3d,BW 2540g,normal development at 1-year-old follow-up |

| Case number | GA# | Gene | Transcripts | Variant | Origin | Inheritance | ACMG Classification |

Zygosity | OMIM Phenotypes | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 30 | WHSC1* | NM_001042424.3 | c.3411_3412delTC (p.Arg1138Ilefs*11) | De novo | AD | P | heterozygous | Rauch-Steindlsyndrome(OMIM 619695) | TOP |

| IC | Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (OMIM 194190) | |||||||||

| 14 | 22 | FGFR3* | NM_000142.5 | c.1620C>A(p.Asn540Lys) | De novo | AD | P | heterozygous | Achondroplasia(OMIM 100800);Hypochondroplasia(OMIM 146000) | TOP |

| 15 | 27 | LIG4* | NM_206937.2 | c.1271_1275 delAAAGA (p.Lys424Argfs*20) | Mat. | AR | P | heterozygous | LIG4 syndrome (OMIM 606593) | TOP |

| c.833G>T(p.Arg278Leu) | Pat. | P | heterozygous | |||||||

| 16 | 27 | IHH* | NM_006208.3 | c.84C>A(p.Cys28*) | Pat. | AD | LP | heterozygous | Brachydactyly, type A1 (OMIM 112500) |

LB ,40w6d ,BW 2850g,, normal development at 2-year-old follow-up |

| ENPP1@ | NM_002181.4 | c.783C>G(p.Tyr261*) | Mat | AD | P | heterozygous | Cole disease (OMIM 615522); Diabetes mellitus, non-insulin-dependent, susceptibility to (OMIM 125853) | |||

| 17 | 31 | TUBB2B* | NM_178012.5 | c.350T>C(p.Leu117Pro) | De novo | AD | P | heterozygous | Cortical dysplasia, complex, with other brain malformations 7(OMIM 610031) | TOP |

| 18 | 22 | BRPF1* | NM_001003694.2 | c.1218C>A(p.Tyr406*) | De novo | AD | P | heterozygous | Intellectual developmental disorder with dysmorphic facies and ptosis(OMIM 617333) | TOP |

| 19 | 18 | PAH@ | NM_000277.3 | c.1197A>T(p.Val399=) | Mat. | AR | P | heterozygous | Phenylketonuria/Hyperphenylalaninemia, non-PKU mild(OMIM 261600) | TOP |

| 20 | 16 | FGFR2@ | NM_000141.5 | c.1032G>A(p.Ala344=) | De novo | AD | P | heterozygous | Antley-Bixler syndrome without genital anomalies or disordered steroidogenesis(OMIM 207410);Apert syndrome(OMIM 101200); Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome(OMIM 123790); Crouzon syndrome(OMIM 123500); Jackson-Weiss syndrome(OMIM 123150) ; LADD syndrome 1(OMIM 149730);Craniofacial-skeletal-dermatologic dysplasia(OMIM 101600);Pfeiffer syndrome(OMIM 101600); Saethre-Chotzen syndrome(OMIM 101400);Bent bone dysplasia syndrome(OMIM 614592); ?Scaphocephaly, maxillary retrusion, and impaired intellectual development(OMIM 609579); Scaphocephaly and Axenfeld-Rieger anomaly;Craniosynostosis, nonspecific |

TOP |

| UPD(6)*& | / | Seq[GRCh37]6q23.3q27(400000-171000000)*2 hmz | Mat. | P | / | / | ||||

| 21 | 30 | SMAD6@ | NM_005585.5 | c.1378dupG (p.Asp460Glyfs*105) |

De novo | AD | LP | heterozygous | Craniosynostosis 7, susceptibility to (OMIM 617439); Radioulnar synostosis, non-syndromic (OMIM 179300); Aortic valve disease 2 (OMIM 614823) | LB,37w3d, BW 2550g, normal development at 6 month follow-up |

| 22 | 25 | FLNB@ | NM_001457.4 | c.6773-1G>A(p.Gln214*) | Pat. | AD | LP | heterozygous | Boomerang dysplasia(OMIM 112310);Larsen syndrome(OMIM 150250); Atelosteogenesis, type I(OMIM 108720);Atelosteogenesis, type III (OMIM 108721) | LB,39w,BW 2630g, normal development at 1-year-old follow-up |

| 23 | 26 | MSH2@ | NM_000251.2 | EX1 Del | Pat. | AD | P | heterozygous | Lynch syndrome 1 (OMIM 120435) | LB,38w2d, BW 2330g, normal development at 2-year-old follow-up |

| 24 | 23 | BRIP1@ | NM_032043.3 | c.1565C>G(p.Ser522Ter) | Mat. | AD | LP | heterozygous | Breast cancer, early-onset, susceptibility to(OMIM 114480) | LB,39w2d, BW 2700g, normal development at 2-year-old follow-up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).