Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement and Scientific Rationale

1.2. The Role of the Model in Addressing Scientific-Pedagogical Gaps in the Global Education System and Minimizing Paradigmatic Structural Misalignments

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organization of the Empirical Component: Methodology for the Practical Application of the New EDSM Model

2.1.1. Methodology for Assessing Student Learning Outcomes Using an Analytical Rubric and Percentage-Based Grading

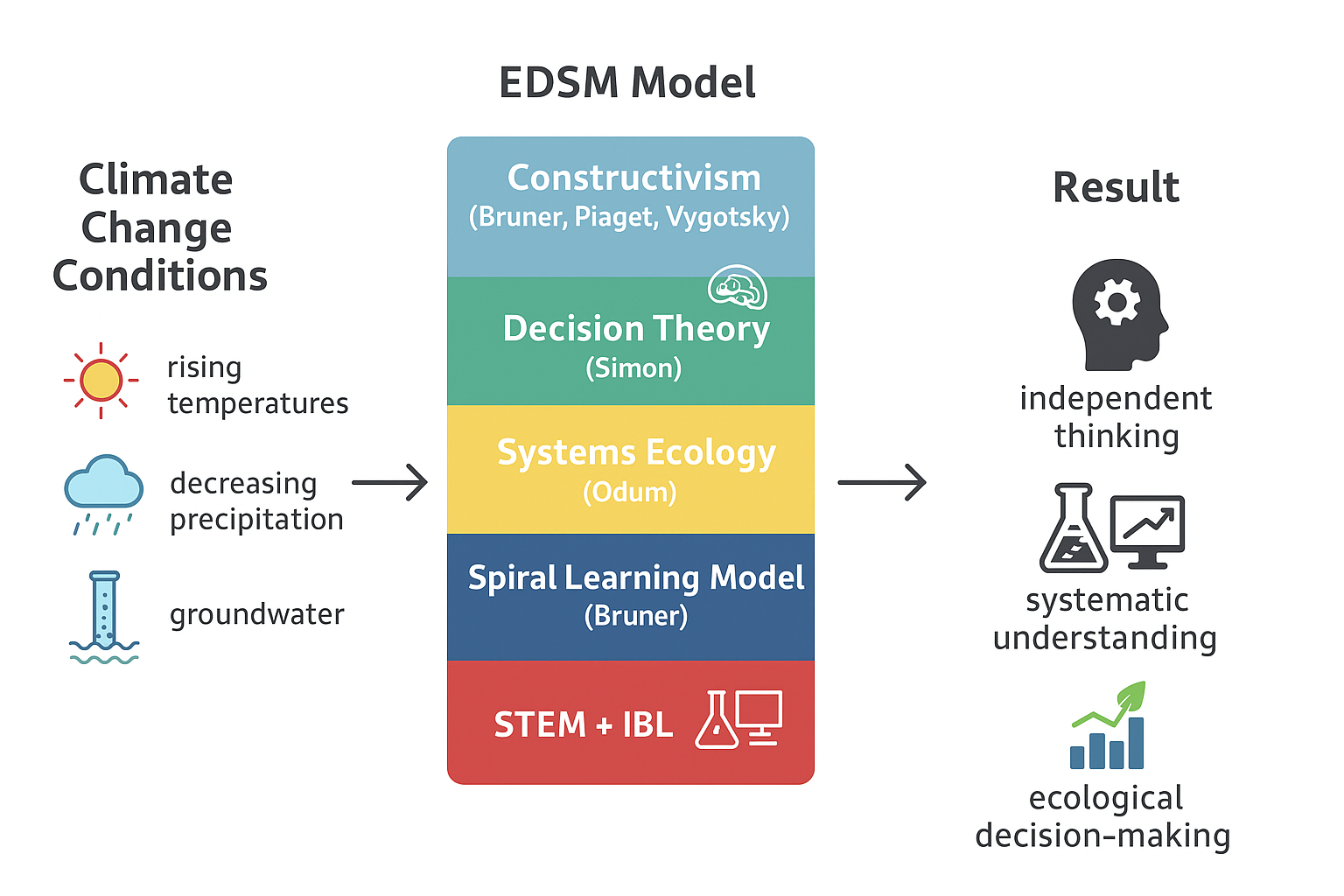

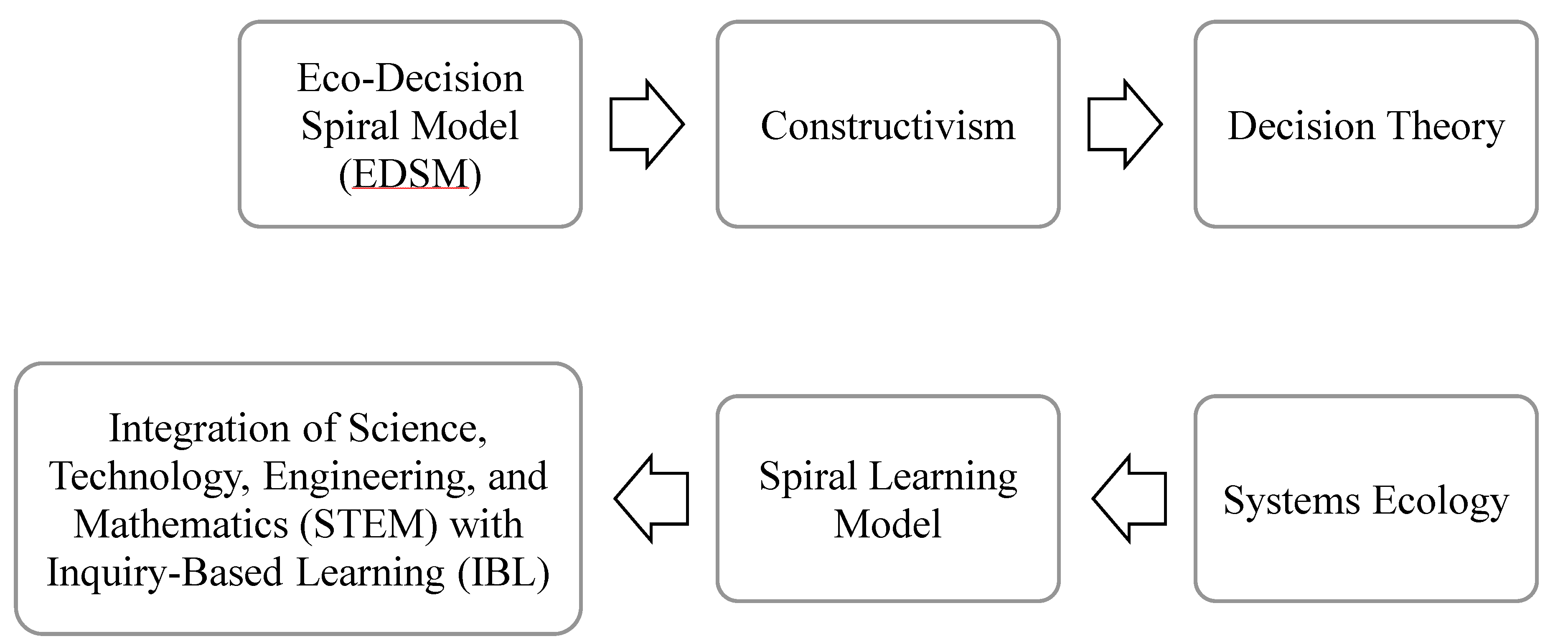

2.2. Scientific–Methodological Integration of the EDSM Model: A Methodological System Grounded in Global Fundamental Principles

2.2.1. Constructivist Theory: Avoiding Learner Passivity

2.2.2. Decision Theory (Herbert Simon): Enhancing the Operational Mechanism of the New EDSM Model Through Bounded Rationality and Scientific Decomposition

2.2.3. The Necessity of Integrating the “Systems Ecological Approach (Odum, 1971)” into the EDSM Model

2.2.4. The Necessity of Integrating Jerome Bruner’s Spiral Curriculum Model into the EDSM Framework

2.2.5. The Necessity of Integrating STEM and Inquiry-Based Learning Principles into the EDSM Model

2.3. Analysis of Results from Applying the What? - So What? - Now What? (WSWNW) Model in Conjunction with the EDSM Model

2.4. Brief Overview of the Teaching Material

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Empirical Research Results from the Application of the Eco-Decision Spiral Model (EDSM)

3.2. Advantages and Limitations of Educational Models in Interdisciplinary and Environmental Studies

3.3. Alignment of the EDSM Model with International Educational Standards, Fundamental Concepts, and Empirical Effectiveness

| Statistical Parameters | EDSM | WSWNW | ||||||||

| Essay total score (A=4, B=3, C=2, D=1) | Test score (%) | Test letter grade (%) | Number of students who passed the course | Course mastery rate (%) | Essay total score (A=4, B=3, C=2, D=1) |

Test score (%) | Test letter grade (%) | Number of students who passed the course | Course mastery rate (%) | |

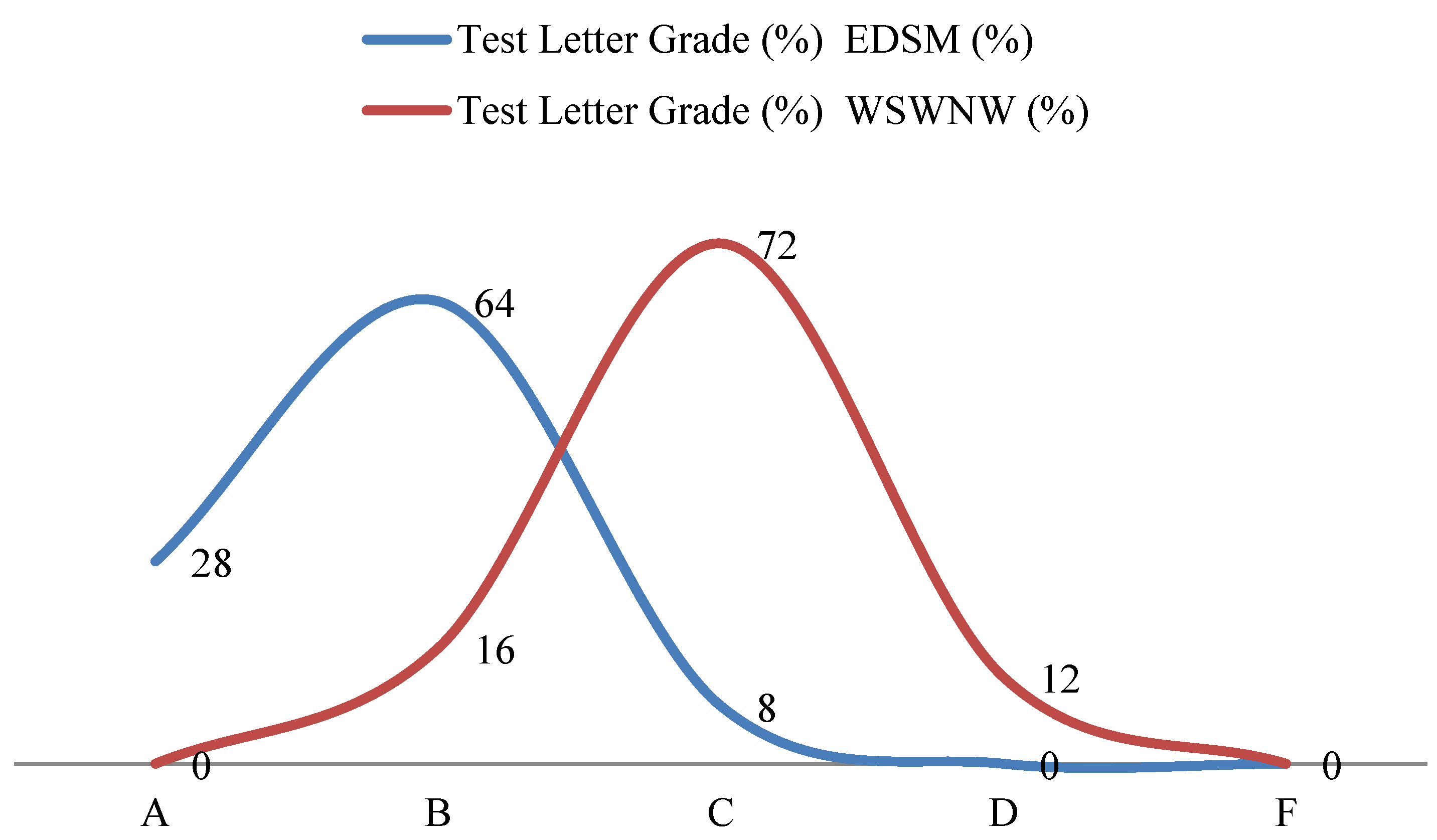

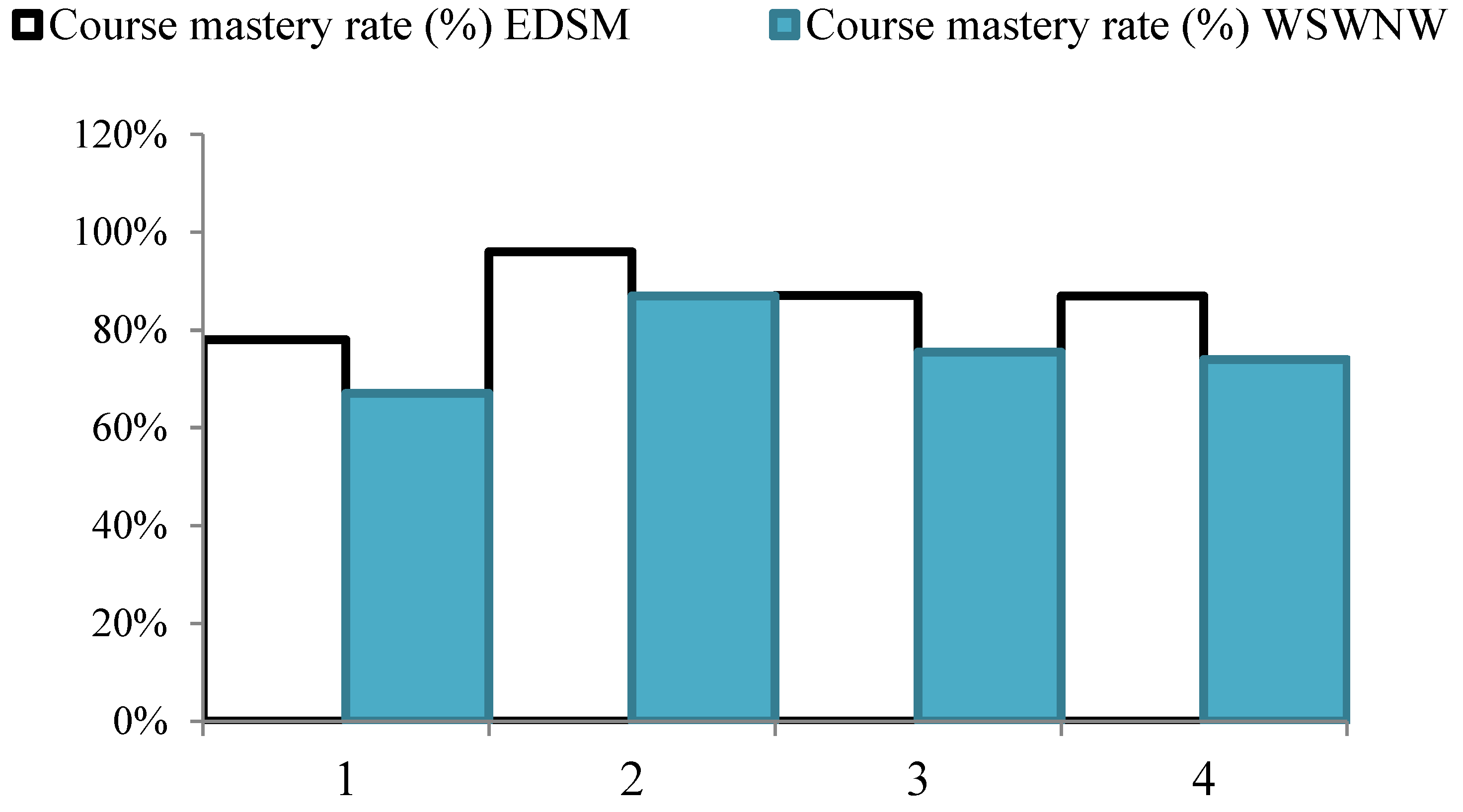

| Minimum | 2.4 | 78 | 8% (C), 0% (D, F), 28% (A) | 25 | 78% | 2.4 | 67 | A (0%), 0% (F), 12% (D), 16% (B) | 25 | 67% |

| Maximum | 4 | 96 | 64% (B) | 25 | 96% | 3.6 | 87 | 72% (C) | 25 | 87% |

| Mean±SD | 3.55 ± 0.41 | 87.68 ± 4.71 | – | – | 87.04% | 3 ± 0.25 | 75.48 ± 5.55 | – | – | 75.48% |

| Median | 3.6 | 87 | – | – | 87% | 3 | 74 | – | – | 74% |

| Aspect | EDSM (Eco-Decision Spiral Model) | WSWNW (What? - So What? - Now What?) | Similarities |

| Level of Knowledge Acquisition | Significantly high (empirical results: essay scores 3.14-3.96, test 82.97-92.39%, average 87.04%). | Lower (empirical results: essay 2.75-3.25, test 75.48 ± 5.55%, average 75.48%). | Both are based on systematic assessment of students’ learning processes. |

| Theoretical Basis | Constructivism, Spiral Learning, STEM and IBL, Systems Ecology Approach, Decision Theory (Simon). | Reflective Thinking (description - analysis - practical decision). | Both models contribute to developing students’ critical and logical thinking. |

| Effectiveness in Teaching Complex Topics | Aimed at in-depth study of complex ecological and multidisciplinary topics; integration with STEAM and IBL. | Simple and structured: learning in 3 stages (What? – So What? - Now What?). | Both models structure the learning process and ensure consistency. |

| Pedagogical Approach | High engagement, collaboration-oriented, enriched with gamification and multisensory (VAK) elements. | Reflective, based on individual and group analysis. | Both models encourage transition from passive listening to active learning. |

| Assessment System | Essays, tests, competency index, dynamic growth indicators. | Essays and tests (percentage and A-D grades). | Both models allow evaluation of learning outcomes in theoretical and practical aspects. |

| Advantages | Intensive mastery of complex ecological and multidisciplinary topics; high performance and stability; scientifically grounded; integration with STEM and IBL. | Simplicity and universality; systematic development of reflective thinking; practical decision-making. | Both develop students’ analytical, argumentative, and critical thinking skills. |

| Limitations | Complex in practice, requires high resources and time; initial preparation needed. | Limited depth for complex topics; theoretical and practical integration is constrained. | Both require a certain level of educational resources and methodological preparation. |

| Practical Applicability | Highly effective for modern higher education and complex ecological topics. | Simplified reflective approach; limited for complex topics. | Both models enhance educational quality, though the effectiveness may vary significantly depending on the field of application and objectives. |

| Standard/Model | Founding Organization/Scientist(s)/ Year Established |

Main Purpose(s) | The model’s compatibility with global educational quality (+/-) | EDSM Compatibility (+) / Incompatibility (–) |

| Bloom’s classic cognitive taxonomy [47,48] | Benjamin Bloom, Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, David Krathwohl (1956). | - To structure learning objectives by cognitive complexity - To guide curriculum design and assessment - To classify thinking skills into hierarchical levels - To support evidence-based teaching and evaluation | All six cognitive levels are aligned (+): Remembering (+) Understanding (+) Applying (+) Analyzing (+) Evaluating (+) Creating (+) | ++ |

| Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) [49] | 2000s (conceptual), official recognition 2005–2010 | Achieve SDGs through education; equip individuals to address social and environmental issues | Cognitive (knowledge), Socio-emotional (social-emotional), Behavioral (actions); lifelong learning | ++ |

| ESD for 2030 Framework [50] | 2021 (Berlin, UNESCO 2021 World Conference on ESD) | Implement ESD nationally and globally; advance policies; transform learning environments; empower youth | Advancing policy, Transforming learning environments, Building capacities of educators, Empowering youth, Accelerating local action | ++ |

| Greening Education Partnership [51] | 2022 (UN Secretary-General's Summit on Transforming Education) | Prepare learners for climate change; support schools, curricula, teacher training, and communities | Greening schools, Greening curricula, Teacher training & system capacities, Community engagement | ++ |

| Climate Change Education [52,53] | Ongoing, strengthened in 2022 through Greening Education Partnership | Educate about climate change; influence attitudes; promote positive actions | Teaching climate change and impacts, Integration in learning environments, Socio-economic & environmental context | ++ |

| OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030/2040 [54] | OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2015 (Education 2030, transitioning to Education 2040) | Prepare students for the 21st century; develop competencies for future jobs, societal challenges, and technologies; promote student agency, well-being, ethical and responsible actions; support teacher competencies and curriculum modernization | Student competencies: knowledge, skills, attitudes, values; Student agency & well-being; Teacher competencies (Teaching Compass 2030); Curriculum design, implementation, evaluation | ++ |

| Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) [55] | NGSS Lead States (coalition of U.S. States), 2013–2014 | Improve K–12 science education; develop deep understanding of content; prepare students for college, careers, and citizenship | Three Dimensions: Crosscutting Concepts, Science & Engineering Practices, Disciplinary Core Ideas; Inquiry, problem solving, communication, collaboration, flexibility; Research-based K–12 standards | ++ |

| ISTE Standards for Educators & Leaders [56] | ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education), 1998–present | Equip higher education educators and leaders with the skills and knowledge to integrate technology effectively, foster high-impact and equitable learning, support professional growth, and lead digital-age transformation in educational institutions | Digital-age pedagogy, Effective use of technology for learning, Leadership in learning environments, Systemic change and culture transformation, Professional development and coaching, Equity and accessibility, Sustainability in technology use | ++ |

| European Qualifications Framework (EQF) [57] | European Commission, 2008 (revised 2017) | To enhance qualifications and skills in education and the labor market, make them transparent and comparable, and facilitate recognition abroad | Knowledge, skills, responsibility, and autonomy across 8 levels; based on learning outcomes; principles of quality assurance | ++ |

| Tuning Educational Structures in Europe [58] | European Commission (Socrates Programme) | Support implementation of the Bologna Process; enhance transparency, comparability, and quality of higher education; define generic and subject-specific competences; facilitate mobility and employability | Learning outcomes and competences (generic and subject-specific); curriculum design and evaluation; two-cycle degree structure; ECTS credit system; quality assurance; lifelong learning | ++ |

| Constructivist Learning Theory / Constructivism [59] | Jean Piaget (1967), Lev Vygotsky (1978), John Dewey (1916), Jerome Bruner (1961), Ernst von Glasersfeld (1995) | To develop critical thinking, promote active knowledge construction, facilitate learning based on prior knowledge and experiences, and encourage collaborative and authentic learning | Learner-centered knowledge construction; social and cognitive interaction; scaffolding; self-regulation; authentic learning; prior knowledge activation; collaborative learning; problem-solving | ++ |

| EAQA Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Higher Education [60] | QAHE / ISO, 2023 | To demonstrate quality assurance, continuous improvement, efficiency, and credibility in higher education | Institutional credibility; quality management; continuous improvement; student satisfaction; operational efficiency; international recognition | ++ |

| P21 Framework for 21st Century Skills [61] | Partnership for 21st Century Learning (US Dept. of Education, Apple, Microsoft, Cisco, SAP, NEA) / 2006 (first published), updated 2015 | To integrate 21st century skills (critical thinking, creativity, communication, collaboration) into core academic subjects, preparing students for college, career, and life | Core subjects (Lang Arts, Math, Science, History, Arts, Economics, Geography, Civics, World Languages); Interdisciplinary themes (Global, Financial, Civic, Health, Environmental Literacy); 4Cs (Critical Thinking, Creativity, Collaboration, Communication); Info/Media/Tech Skills; Life & Career Skills; Leadership & Responsibility; Support systems (Standards, Assessment, Curriculum, Instruction, PD, Learning Environments) | ++ |

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

References

- Nunes, L. J. The rising threat of atmospheric CO2: a review on the causes, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Environments 2023, 10(4), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measho, S.; Li, F.; Pellikka, P.; Tian, C.; Hirwa, H.; Xu, N.; Chen, G. Soil salinity variations and associated implications for agriculture and land resources development using remote sensing datasets in Central Asia. Remote sensing 2022, 14(10), 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanov, S.; Kulmatov, R.; Li, F.; van Amstel, A.; Bartholomeus, H.; Aslanov, I.; Chen, G. Impact assessment of soil salinity on crop production in Uzbekistan and its global significance. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2023, 342, 108262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabova, N.; Sherimbetov, V.; Sadiq, R.; Farouk Aboukila, A. An Assessment of Collector-Drainage Water and Groundwater—An Application of CCME WQI Model. Water 2025, 17(15), 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabova, N.; Aboukila, A. F.; Toshev, S.; Obasuyi, G. E. Appraisal of Groundwater Status Applying the CCME WQI Model. E3S Web of Conferences, 2025; EDP Sciences; Vol. 648, p. 02001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabova, N.; Sherimbetov, V. Evaluation of Groundwater Quality Using WQI Models and Its Application to Plants Vulnerable to Ecological Stress. J. Stress Physiology & Biochemistry 2025, 21(3), 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kakabayev, A.; Yessenzholov, B.; Khussainov, A.; Rodrigo-Ilarri, J.; Rodrigo-Clavero, M. E.; Kyzdarbekova, G.; Dankina, G. The impact of climate change on the water systems of the Yesil River Basin in Northern Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2023, 15(22), 15745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, S. A.; Cerón, V. A.; Guevera-Fletcher, C. E.; Bermúdez, I. M.; Gutiérrez, C. A.; Pelegrin, J. S. Knowledge in regard to environmental problems among university students in Cali, Colombia. Sustainability 2023, 15(21), 15315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P. K.; Behera, B. A critical review of impact of and adaptation to climate change in developed and developing economies. Environment, development and sustainability 2011, 13(1), 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, F.; Lin, T.; Xu, Q.; Yu, P.; Wang, C.; Yuan, K. A systematic review and comprehensive analysis on ecological restoration of mining areas in the arid region of China: Challenge, capability and reconsideration. Ecological Indicators 2023, 154, 110630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, H.; Schnepf, A.; Hopmans, J. W.; Javaux, M.; Or, D.; Roose, T.; Young, I. M. Modeling soil processes: Review, key challenges, and new perspectives. Vadose zone journal 2016, 15(5), vzj2015–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ffolliott, P. F. Arid and semiarid land stewardship: a 10-year review of accomplishments and contributions of the International Arid Lands Consortium; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gambella, F.; Quaranta, G.; Morrow, N.; Vcelakova, R.; Salvati, L.; Gimenez Morera, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Soil degradation and socioeconomic systems’ complexity: Uncovering the latent nexus. Land 2021, 10(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jung, W.; Asari, M. Systematic Review of Environmental Education Teaching Practices in Schools: Trends and Gaps (2015–2024). Sustainability 2025, 17(19), 8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronau, R. N.; Rakes, C. R.; Niess, M. L. Educational technology, teacher knowledge, and classroom impact: A research handbook on frameworks and approaches; No Title, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.; Heinrich, K. K.; Reynolds, J.; Howeth, J. G. An Ecological Succession Lesson from a Beaver’s Point of View. The American Biology Teacher 2022, 84(4), 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Jung, Y. S.; Pereira, R. V. V.; Brouwer, M. S.; Song, J.; Osburn, B. I.; Qian, Y. Advancing One Health education: integrative pedagogical approaches and their impacts on interdisciplinary learning. Science in One Health 2024, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purbrick, T. Military Cultural Property Protection Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of International Peacekeeping 2025, 27(4), 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbedahin, A. V. Sustainable development, Education for Sustainable Development, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Emergence, efficacy, eminence, and future. Sustainable development 2019, 27(4), 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Sachathep, K.; Kulaponse, P. P. ESD currents: Changing perspectives from the Asia-Pacific; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holst, J.; Brock, A.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; De Haan, G. Monitoring progress of change: Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) within documents of the German education system. Sustainability 2020, 12(10), 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Heras, R.; Mulà, I.; Salgado, F. P.; Henderson, L. Competences to address SDGs in higher education—A reflection on the equilibrium between systemic and personal approaches to achieve transformative action. Sustainability 2019, 11(13), 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodamoradi, A. 21st Century Skills and Literacies: Fundamental Reform Document of Education (FRDE) vs. P21 Framework for 21st Century Learning. Iranian Journal of Comparative Education 2024, 7(4), 3250–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, I. S.; Quintana, M. G. B. 21st century skills. An analysis of theoretical frameworks to guide educational innovatión processes in chilean context. In the International Research & Innovation Forum; Springer International Publishing: Cham, April 2019; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobajas, M.; Molina, C. B.; Quintanilla, A.; Alonso-Morales, N.; Casas, J. A. Development and application of scoring rubrics for evaluating students’ competencies and learning outcomes in Chemical Engineering experimental courses. Education for Chemical Engineers 2019, 26, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, P. L.; Yan, X. An investigation of the relationship between argument structure and essay quality in assessed writing. Journal of Second Language Writing 2022, 56, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. Educational constructivism. Encyclopedia 2024, 4(4), 1534–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, C. L.; Carrico, C.; Ginn, C. C.; Felber, A.; Smith, S. Social constructivism in learning: Peer teaching & learning; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdem-Yilmaz, Y.; Bilican, K. Discovery learning—jerome bruner. In Science education in theory and practice: An introductory guide to learning theory; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; O'Leary, C.; McAvinia, C.; Ryan, B. J. Generating a Template for an Educational Software Development Methodology for Novice Computing Undergraduates: An Integrative Review. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Q.; Hang, Y. Decomposition and attribution analysis of the transport sector’s carbon dioxide intensity change in China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2019, 119, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campitelli, G.; Gobet, F. Herbert Simon's decision-making approach: Investigation of cognitive processes in experts. Review of general psychology 2010, 14(4), 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S. L.; Peck, C. A.; Hanson, M.; Beckman, P. J.; Kaiser, A. P.; Lieber, J.; Schwartz, I. S. Inclusion at the preschool level: An ecological systems analysis. Social Policy Report: Society for Research in Child Development 1996, 10(2-3), 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. International encyclopedia of education 1994, 3(2), 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter, M.; Müller, B.; Frank, K. The potential of models and modeling for social-ecological systems research. Ecology and Society 2019, 24(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S. Jerome Bruner Theory of Cognitive Development; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, J.; Mouthaan, M. Perspectives on curriculum design: comparing the spiral and the network models. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera-Mendoza, F.; Cayani Caceres, K. S.; Urdanivia Alarcon, D. A.; Gutiérrez Miranda, S. A.; Rucano Paucar, F. H. Teacher performance level to guide students in inquiry-based scientific learning. Education Sciences 2024, 14(8), 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdanivia Alarcon, D. A.; Talavera-Mendoza, F.; Rucano Paucar, F. H.; Cayani Caceres, K. S.; Machaca Viza, R. Science and inquiry-based teaching and learning: a systematic review. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA, May 2023; Vol. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W. B. So Now What? Foot & Ankle Specialist 2017, 10(2), 103–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajah, R. T.; Curci, N. E.; Johnson, E. M.; Lam, D. L.; Lee, J. T.; Richardson, M. L. A review of innovative teaching methods. Academic radiology 2019, 26(1), 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Gao, J. Adapting to climate change: gaps and strategies for Central Asia. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2020, 25(8), 1439–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioubimtseva, E.; Henebry, G. M. Climate and environmental change in arid Central Asia: Impacts, vulnerability, and adaptations. Journal of Arid Environments 2009, 73(11), 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adapting to climate change in Eastern Europe and Central Asia; Fay, M., Block, R., Ebinger, J., Eds.; World Bank Publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saidaliyeva, Z.; Muccione, V.; Shahgedanova, M.; Bigler, S.; Adler, C.; Yapiyev, V. Adaptation to climate change in the mountain regions of Central Asia: A systematic literature review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2024, 15(5), e891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Taylor, J. Linear regression. In An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in python; Springer international publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 69–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunida, H.; Arthur, R. Bloom’s taxonomy approach to cognitive space using classic test theory and modern theory. East Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 2023, 2(1), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuma, F.; Nassar, A. K. Applying Bloom's taxonomy in clinical surgery: practical examples. Annals of medicine and surgery 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.; Brock, A.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; De Haan, G. Monitoring progress of change: Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) within documents of the German education system. Sustainability 2020, 12(10), 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A.; Byun, W. J. UNESCO’s Framework ESD for 2030. In IBE on Curriculum, Learning, and Assessment; 2021; Volume 89. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. K. Galvanizing Education for Sustainable Development Practice Through the Greening Education Partnership: Steering Green Schools Towards 2030 and Beyond. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 2025, 09734082251355099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SZKOLA, S.; DENIGOT, T.; NAPOLI, V.; WILLIQUET, F. The Education For Climate Coalition; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Salsabila, I. N. Green Education Movement: Integrating Environmental Education in the Curriculum to Address the Global Climate Crisis. International Journal of Social Research 2025, 3(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T.; Chau, G. C.; Lee, B. M. Development of 21st-Century Skills: A Comprehensive Analysis Based on the OECD Learning Compass 2030. Promoting Holistic Development in University Students 2025, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. S. What does a national survey tell us about progress toward the vision of the NGSS? Journal of Science Teacher Education 2020, 31(6), 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H. Evidence of the ISTE Standards for Educators leading to learning gains. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 2023, 39(4), 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, R. Adaptation of Australian Qualifications in Building and Construction for Delivery within the European Qualifications Framework. International Education and Research Journal 2020, 6(5), 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Antonazzo, L.; Weinel, M.; Stroud, D. Analysis of cross-European VET frameworks and standards for sector skills recognition. Deliverable D4. 2 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D.; Iacovelli, G.; O'Toole, T.; Cavallini, I.; Mørch Hauge, I.; Moura Sá, P.; Vezir Oguz, G. Tuning Educational Structures In Europe: Guidelines And Reference Points For The Design And Delivery Of Degree Programmes in Business. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, R. The European Approach for Quality Assurance of Joint Programmes; Outcomes Peer Learning Activity: The Hague, 2019; pp. 202–3. [Google Scholar]

- Khodamoradi, A. 21st Century Skills and Literacies: Fundamental Reform Document of Education (FRDE) vs. P21 Framework for 21st Century Learning. Iranian Journal of Comparative Education 2024, 7(4), 3250–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Winter Mean ± SD | Spring Mean ± SD | Summer Mean ± SD | Autumn Mean ± SD | Annual Mean ± SD | |||||

| Soil profile moisture (m³/m³) | Temperature (°C) |

Soil profile moisture (m³/m³) | Temperature (°C) |

Soil profile moisture (m³/m³) | Temperature (°C) |

Soil profile moisture (m³/m³) | Temperature (°C) |

Soil profile moisture (m³/m³) | Temperature (°C) |

|

| 1984 | 0.47 ± 0.015 | -15.02 ± 2.91 | 0.503 ± 0.021 | 6.57 ± 10.02 | 0.426 ± 0.011 | 25.46 ± 2.52 | 0.43 ± 0.010 | 6.13 ± 9.20 | 0.46 ± 0.020 | 5.53 ± 13.67 |

| 1985 | 0.463 ± 0.012 | -9.40 ± 2.50 | 0.470 ± 0.020 | 5.95 ± 8.83 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 23.65 ± 2.55 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 4.26 ± 8.77 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.10 ± 10.97 |

| 1986 | 0.473 ± 0.015 | -12.27 ± 2.82 | 0.497 ± 0.021 | 6.70 ± 10.01 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 22.83 ± 2.28 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 5.60 ± 7.59 | 0.46 ± 0.020 | 5.90 ± 10.50 |

| 1987 | 0.483 ± 0.015 | -10.86 ± 2.71 | 0.540 ± 0.030 | 7.02 ± 6.04 | 0.443 ± 0.015 | 23.08 ± 1.21 | 0.44 ± 0.006 | 3.87 ± 6.03 | 0.47 ± 0.025 | 5.25 ± 9.21 |

| 1988 | 0.47 ± 0.012 | -10.54 ± 3.91 | 0.477 ± 0.021 | 9.37 ± 5.34 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 25.84 ± 0.89 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 7.67 ± 8.20 | 0.45 ± 0.020 | 7.26 ± 11.20 |

| 1989 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -9.87 ± 3.38 | 0.510 ± 0.020 | 11.53 ± 9.00 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 24.23 ± 2.17 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 6.48 ± 8.17 | 0.46 ± 0.015 | 7.13 ± 10.37 |

| 1990 | 0.473 ± 0.015 | -11.93 ± 5.69 | 0.500 ± 0.020 | 11.37 ± 8.36 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 23.87 ± 1.57 | 0.447 ± 0.017 | 8.34 ± 8.25 | 0.46 ± 0.020 | 6.53 ± 10.70 |

| 1991 | 0.483 ± 0.015 | -12.02 ± 5.88 | 0.513 ± 0.010 | 11.56 ± 8.18 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 23.89 ± 1.26 | 0.443 ± 0.006 | 8.45 ± 8.64 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 6.69 ± 10.70 |

| 1992 | 0.463 ± 0.015 | -9.56 ± 1.80 | 0.523 ± 0.035 | 7.63 ± 8.19 | 0.44 ± 0.012 | 21.74 ± 1.95 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 4.58 ± 7.05 | 0.46 ± 0.020 | 5.46 ± 9.10 |

| 1993 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -11.83 ± 1.71 | 0.500 ± 0.020 | 4.99 ± 3.53 | 0.44 ± 0.012 | 22.67 ± 1.67 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 2.60 ± 10.36 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 4.54 ± 9.56 |

| 1994 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -13.19 ± 2.82 | 0.467 ± 0.020 | 5.77 ± 5.94 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 23.88 ± 1.15 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 6.21 ± 7.33 | 0.44 ± 0.018 | 5.63 ± 10.10 |

| 1995 | 0.483 ± 0.020 | -11.17 ± 5.92 | 0.500 ± 0.020 | 9.50 ± 6.24 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 24.67 ± 1.54 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | 6.82 ± 5.55 | 0.46 ± 0.022 | 7.34 ± 9.75 |

| 1996 | 0.487 ± 0.012 | -12.52 ± 5.02 | 0.503 ± 0.015 | 8.83 ± 5.86 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 22.23 ± 1.66 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | 7.08 ± 5.11 | 0.47 ± 0.018 | 4.84 ± 9.10 |

| 1997 | 0.483 ± 0.012 | -12.35 ± 6.14 | 0.533 ± 0.012 | 9.35 ± 7.34 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 24.04 ± 1.25 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 8.47 ± 8.25 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 7.25 ± 9.90 |

| 1998 | 0.437 ± 0.012 | -11.44 ± 6.35 | 0.503 ± 0.015 | 9.29 ± 6.10 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 26.41 ± 1.52 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 5.23 ± 5.00 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.48 ± 10.20 |

| 1999 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | -9.88 ± 2.18 | 0.473 ± 0.012 | 9.50 ± 6.01 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 23.39 ± 2.59 | 0.423 ± 0.006 | 9.09 ± 7.02 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.95 ± 9.90 |

| 2000 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -9.67 ± 4.77 | 0.480 ± 0.012 | 10.90 ± 7.17 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 24.25 ± 1.20 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 7.53 ± 6.55 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.69 ± 9.80 |

| 2001 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -11.24 ± 6.16 | 0.470 ± 0.012 | 12.22 ± 6.01 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 22.43 ± 0.88 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | 6.01 ± 7.25 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.75 ± 10.10 |

| 2002 | 0.487 ± 0.018 | -8.00 ± 4.40 | 0.553 ± 0.015 | 6.78 ± 5.23 | 0.463 ± 0.012 | 22.35 ± 2.42 | 0.43 ± 0.006 | 7.53 ± 7.22 | 0.48 ± 0.022 | 6.97 ± 9.40 |

| 2003 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -11.64 ± 4.11 | 0.523 ± 0.015 | 4.84 ± 6.33 | 0.473 ± 0.012 | 21.76 ± 3.32 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 10.57 ± 4.29 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 5.62 ± 8.87 |

| 2004 | 0.476 ± 0.015 | -10.80 ± 3.95 | 0.527 ± 0.015 | 7.81 ± 8.00 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 22.77 ± 0.99 | 0.443 ± 0.006 | 13.02 ± 2.84 | 0.47 ± 0.018 | 7.00 ± 9.05 |

| 2005 | 0.457 ± 0.012 | -10.92 ± 5.91 | 0.513 ± 0.015 | 14.25 ± 9.05 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 23.75 ± 1.38 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 8.65 ± 3.80 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 7.29 ± 9.60 |

| 2006 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -13.79 ± 7.51 | 0.477 ± 0.015 | 10.54 ± 6.95 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 23.52 ± 0.82 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | 7.36 ± 4.68 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.93 ± 10.00 |

| 2007 | 0.463 ± 0.015 | -9.37 ± 4.34 | 0.527 ± 0.020 | 11.47 ± 6.95 | 0.433 ± 0.000 | 23.99 ± 1.38 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 7.90 ± 4.61 | 0.47 ± 0.020 | 6.82 ± 9.10 |

| 2008 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -12.82 ± 5.75 | 0.490 ± 0.012 | 10.92 ± 7.03 | 0.426 ± 0.006 | 24.47 ± 1.70 | 0.44 ± 0.012 | 8.31 ± 4.02 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 7.30 ± 9.50 |

| 2009 | 0.493 ± 0.012 | -11.46 ± 3.63 | 0.533 ± 0.012 | 5.96 ± 7.92 | 0.44 ± 0.006 | 22.64 ± 0.64 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | 7.18 ± 4.26 | 0.48 ± 0.020 | 6.07 ± 8.95 |

| 2010 | 0.493 ± 0.012 | -11.46 ± 6.30 | 0.533 ± 0.012 | 10.97 ± 7.16 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 24.51 ± 0.94 | 0.44 ± 0.012 | 9.53 ± 6.08 | 0.47 ± 0.020 | 6.63 ± 9.20 |

| 2011 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | -10.53 ± 5.32 | 0.47 ± 0.012 | 10.56 ± 3.74 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 22.91 ± 1.32 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 10.00 ± 4.00 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 5.53 ± 8.90 |

| 2012 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | -16.72 ± 7.54 | 0.467 ± 0.012 | 11.21 ± 4.36 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 25.53 ± 1.72 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 6.81 ± 4.99 | 0.44 ± 0.018 | 5.95 ± 9.50 |

| 2013 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -7.77 ± 5.05 | 0.493 ± 0.012 | 11.75 ± 7.04 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 22.90 ± 0.69 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 7.36 ± 4.49 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 7.10 ± 9.20 |

| 2014 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -14.70 ± 6.33 | 0.477 ± 0.012 | 7.57 ± 8.66 | 0.43 ± 0.000 | 24.36 ± 1.71 | 0.47 ± 0.012 | 6.97 ± 5.10 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 5.27 ± 9.00 |

| 2015 | 0.493 ± 0.012 | -9.67 ± 5.56 | 0.543 ± 0.015 | 7.48 ± 4.40 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | 23.57 ± 1.65 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | 7.33 ± 5.32 | 0.48 ± 0.020 | 6.27 ± 8.90 |

| 2016 | 0.487 ± 0.012 | -6.71 ± 5.06 | 0.583 ± 0.015 | 8.58 ± 6.03 | 0.443 ± 0.006 | 22.84 ± 1.45 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 7.69 ± 6.43 | 0.49 ± 0.022 | 6.21 ± 8.90 |

| 2017 | 0.457 ± 0.012 | -11.26 ± 5.12 | 0.503 ± 0.012 | 9.49 ± 4.84 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 23.91 ± 1.16 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 6.48 ± 5.48 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 6.30 ± 9.00 |

| 2018 | 0.457 ± 0.012 | -13.90 ± 5.57 | 0.533 ± 0.012 | 4.63 ± 3.16 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 23.48 ± 3.29 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 5.46 ± 5.27 | 0.47 ± 0.020 | 4.85 ± 8.50 |

| 2019 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -10.91 ± 5.96 | 0.517 ± 0.012 | 7.10 ± 8.13 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 23.64 ± 2.53 | 0.44 ± 0.006 | 8.33 ± 6.56 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 6.36 ± 9.10 |

| 2020 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -10.01 ± 4.65 | 0.520 ± 0.012 | 8.87 ± 9.09 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 23.76 ± 1.68 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 4.62 ± 7.42 | 0.46 ± 0.018 | 6.47 ± 8.90 |

| 2021 | 0.453 ± 0.012 | -9.88 ± 5.36 | 0.500 ± 0.012 | 12.36 ± 6.79 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 24.98 ± 1.61 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 4.78 ± 9.07 | 0.45 ± 0.018 | 6.64 ± 9.00 |

| 2022 | 0.447 ± 0.012 | -11.72 ± 5.08 | 0.543 ± 0.015 | 11.35 ± 3.73 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 23.49 ± 0.88 | 0.443 ± 0.012 | 6.67 ± 7.34 | 0.47 ± 0.020 | 6.80 ± 8.90 |

| 2023 | 0.457 ± 0.012 | -10.13 ± 5.62 | 0.533 ± 0.015 | 14.23 ± 7.78 | 0.433 ± 0.006 | 24.49 ± 2.36 | 0.46 ± 0.012 | 7.53 ± 6.55 | 0.47 ± 0.020 | 7.82 ± 9.50 |

| 2024 | 0.493 ± 0.012 | -11.19 ± 5.23 | 0.547 ± 0.015 | 7.31 ± 7.16 | 0.437 ± 0.006 | 23.44 ± 0.94 | 0.44 ± 0.012 | 7.80 ± 5.00 | 0.49 ± 0.020 | 6.28 ± 9.10 |

| 1 | POWERing the Future of Energy, Infrastructure, and Agroclimatology: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).