1. Introduction

Over the past decade, urban planning in China has shifted from high-speed expansion to the stock-optimization phase, marking a strategic shift from scale growth and factor inputs to renewal practices centered on quality enhancement, structural repair, and fine-grained governance [

1,

2,

3]. A fundamental question in this transition is how to measure “urban spatial quality” in a scientific, comparable, and operational manner [

4]. Such measurement considers not only objective physical indicators but also people’s subjective perception and experience. For instance, as early as the 1960s, Kevin Lynch [

5] emphasized in

The Image of the City that the material environment shapes residents’ mental images, with paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks jointly forming a legible urban image. Jane Jacobs [

6] subsequently proposed the “eyes on the street,” arguing that streets animated by pedestrian flow and natural surveillance can substantially improve the sense of safety. Conversely, neighborhood dilapidation undermines safety and belonging, as classically articulated by Wilson and Kelling’s [

7] “broken windows” hypothesis. Recent studies have shown that the aesthetic quality of streetscapes not only enhances urban attractiveness but is also positively associated with mental and physical health [

8,

9,

10]. Together, these studies underscore that the visual quality of the built environment is tightly linked to subjective feelings; dimensions such as safety, vitality, and beauty have become key determinants of urban spatial success [

11,

12]. These converging insights demonstrate that visual perception is not merely an aesthetic consideration but a fundamental determinant of urban livability.

Traditionally, urban perception has been assessed through questionnaires and field audits. However, these methods are costly and time-consuming, making it difficult to describe perceptual differences street by street at the city scale [

13,

14]. Over the past decade, with the rise of crowdsourcing and computer vision, researchers began to use street-view images (SVIs) and machine learning to quantify perception [

15]. For example, Salesses et al. [

16] collected public judgments via online pairwise image comparisons to build large-scale datasets of subjective evaluations (e.g., safety, prosperity), revealing spatial inequalities in urban perception. The Place Pulse 2.0 dataset developed at MIT Media Lab, as described by Dubey et al. [

17], further distilled urban perception into six dimensions—Safety, Liveliness, Beauty, Wealthiness, and the opposing attributes Depressiveness and Boringness. Building on this, previous approaches usually relied on deep learning or machine learning. Specifically, Zhang et al. [

18] achieved high accuracy in inferring perceptual attributes such as safety and beauty by employing Deep Spatial Attention Neural Zero-Shot (DSANZS) models with supervised and weakly supervised learning on the Place Pulse 2.0 dataset. Additionally, Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training (CLIP)-based zero-shot methods have demonstrated high accuracy in urban perception analysis. For example, CLIP was successfully employed by Liu et al. [

19] to build reliable perceived walkability indicators and by Zhao et al. [

20] to accurately quantify the visual quality of built environments for aesthetic and landscape evaluation. However, although these approaches substantially reduce labeling costs and provide an end-to-end solution, they still require adaptation to local context and offer limited interpretability.

On the other hand, with the rise of computer vision technology, many models have been developed to segment street-view elements and correlate them with perception using machine learning approaches. Semantic segmentation models such as DeepLab [

21] and PSPNet [

22] can identify and quantify various urban elements such as buildings, vegetation, vehicles, and pedestrians in street imagery, providing objective measures of streetscape composition. These segmented elements are then linked to perceptual outcomes through statistical modeling or machine learning algorithms. For instance, Kang et al. [

23] used semantic segmentation to extract 150 visual elements from street-view images and employed random forest regression to predict safety perception scores, finding that the proportion of sky, trees, and crosswalks positively influenced perceived safety while cars and construction elements had negative effects. Furthermore, explainable artificial intelligence techniques, particularly SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) [

24], offer opportunities to open the “black box” of machine learning models by revealing which visual elements contribute most to specific perceptual judgments. For example, researchers have used SHAP values to demonstrate that the presence of greenery and well-maintained facades positively correlates with safety perception. However, these element-based approaches often oversimplify the complex interactions between urban features and may miss subtle contextual factors that influence human perception, thus limiting their ability to capture the holistic nature of urban perception.

In recent years, vision–language models (VLMs) have provided new tools for urban perception research. Large multimodal models such as LLaVA, BLIP-2, and CLIP integrate image understanding with natural-language reasoning and can analyze images in a human-like, instruction-following manner without additional local training, as demonstrated by Moreno-Vera and Poco [

25]. In the urban domain, scholars have begun to explore VLMs for street-scene parsing and evaluation. For example, Yu et al. [

26] extracted street-scene elements with deep learning and, supported by adversarial modeling, quantified the six perception dimensions, combining the results with space-syntax analysis to reveal links between streetscape quality and element configuration. Moreover, VLMs can simultaneously process visual information and generate actionable recommendations for urban improvement, offering a more comprehensive approach than traditional perception analysis methods. This suggests that, without relying on locally labeled data, pretrained VLMs can be used to assess streetscape perception in any city, thereby lowering data costs and improving generalization.

Against this backdrop, this study seeks to address three key research questions that guide our investigation: (1) How accurately can VLMs predict human perceptual judgments across the six urban perception dimensions compared to traditional survey methods? (2) What are the spatial patterns and salient characteristics that VLMs identify in different urban areas, and how do these align with human observations? (3) To what extent can VLMs generate actionable and contextually appropriate renewal suggestions for urban planning practice? To answer these questions, we integrate multimodal VLMs with SVIs using the Hongshan Central District of Urumqi, China, as our study area. We collected 4,215 street-view panoramas and conducted a perception survey with 500 respondents across the six dimensions to establish a human-rated baseline. We then applied multiple VLMs to measure Safety, Liveliness, Beauty, Wealthiness, Depressiveness, and Boringness, accompanied by textual explanations and renewal suggestions. By systematically comparing model outputs with survey results and mining keywords from model descriptions, we evaluate VLM performance boundaries and explore their potential as decision support tools for intelligent urban planning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Hongshan Central District is in the urban core of Urumqi, China, spanning Tianshan, Shayibake, and Shuimogou districts. It is a mixed area of commerce, culture, and housing. Within an area of 20 km², we obtained 4,215 street-view panoramas from Baidu Street View between April and August 2024, covering arterials, secondary streets, alleys, and key nodes (e.g., Hongshan Park, commercial streets, residential compounds, and school environs). The sampling points were systematically distributed at 50-meter intervals along the road network to ensure comprehensive spatial coverage while maintaining computational feasibility. To ensure data quality, we implemented a multi-stage screening process: 1) panoramas with poor visibility (fog, heavy shadows, or construction obstructions) were automatically filtered using image clarity metrics; 2) duplicate or near-duplicate images within 10 meters of each other were removed to avoid spatial redundancy; and 3) manual verification was conducted on a random sample of 500 images to validate the automated screening results, achieving 94% accuracy in quality assessment. These data underpin the subsequent model evaluation and spatial analysis.

Figure 1.

Pipeline of respondent-persona scoring and expert planning with structured outputs.

Figure 1.

Pipeline of respondent-persona scoring and expert planning with structured outputs.

2.2. VLM Selection and Prompt Design

Our methodological workflow is illustrated in

Figure 2, comprising four main components. In Step 1, we instantiate an LLM-simulated respondent persona, whose demographic slots reflect real-world survey distributions (as shown in section 2.3). The persona is coupled with task prompts so that the model reasons from a lay inhabitant’s perspective rather than an expert’s viewpoint. In Step 2, we provide the VLMs with SVI and scoring instructions to constrain the model to judge based on visible cues and subjective spatial perception, assigning integer scores from 1 to 10 for safety, vitality, beauty, wealth, depression, and boredom, each accompanied by a brief rationale (<50 words).

In Step 3, a separate expert-planning agent receives the panoramic image, the six-dimensional scores and rationales. The agent is instructed to generate tier-aligned renewal recommendations in a fixed schema, returning a diagnostic summary (<50 words), quick_fixes (an array of short-term actionable measures), and structural_measures (an array of medium- to long-term spatial or facility interventions). In Step 4, we consolidate one record per panorama into a geo-referenced CSV, including SVI ID, coordinates, persona, the six integer scores, their mean, rationales, and the expert recommendation JSON. This unified table serves as the foundation for mapping, LISA, and text-based analyses in subsequent sections.

We employed nine VLMs for comparative evaluation, encompassing both open-source and commercial models. The selected models represent a balanced mix of open-source and commercial VLMs across different parameter scales, providing a representative comparison of current multimodal architectures. The open-source models include Qwen2.5-VL-3B, 7B, and 32B, GLM-4.1-9B-Base, GLM-4.1-9B-Thinking, and LLaVA-1.6-7B-Mistral. Among these, we selected models from the same family (e.g., Qwen2.5-VL) to facilitate observation of scoring performance across different parameter scales. Additionally, the commercial models comprise GPT-5-Mini, Gemini 2.5-Flash, and Claude 3.5-Haiku, which provide stable APIs [

27,

28,

29,

30]. All models were configured with consistent hyperparameters.

2.3. Human Labeling and Result Validation

To validate the reliability of the VLM-generated scores, we randomly sampled 5% of the total images (n=216) for manual scoring. We designed a six-dimensional perception survey and recruited 500 respondents, covering different demographic groups (

Table 1). Each respondent was randomly assigned a set of 40 SVIs to minimize potential bias from image sequence effects. Participants were asked to provide ratings on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = very negative, 10 = very positive) across six dimensions: Safety (does the scene feel safe), Liveliness (is there visible activity and presence), Beauty (is the scene visually pleasant), Wealthiness (does the environment appear prosperous/high-end versus shabby), Depressiveness (does the scene feel gloomy or oppressive), and Boringness (does the place feel monotonous/uneventful). The first four are positive dimensions (higher is better); the latter two are negative dimensions (higher is worse). For comparability, Depressiveness and Boringness were inverted when computing overall perception so that “higher = better” is consistent across dimensions. Each panorama therefore has six mean scores serving as the human-rated baseline. We also collected comments from 156 participants (32.2% of the sample) to understand salient factors mentioned by respondents; due to limited and unsystematic coverage, these comments were not used for quantitative analysis.

To quantify the accuracy between model measurement and human-rated baseline assessments, we employed a comprehensive set of statistical metrics. The evaluation framework incorporated four complementary measures to capture different aspects of model performance across multiple dimensions. Specifically, for each perceptual dimension, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between the model’s score series and the corresponding human baseline ratings:

where

represents model scores,

represents human baseline scores, and

,

denote their respective means. Values near 1 indicate strong positive relationships, while values close to 0 indicate no relationship. To assess absolute deviation from baseline ratings, we computed the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

lower MSE and RMSE values indicate enhanced predictive accuracy and reduced systematic bias. All metrics were computed per perception dimension and for the six-dimensional mean (overall perception score).

2.4. Analysis of Model-Generated Explanations

Furthermore, to explore the basis of VLM scoring, we analyzed the reasons for the model’s decisions. Specifically, To extract latent thematic structures from these explanations, we employed BERTopic, a neural topic modeling framework that combines transformer-based embeddings with dimensionality reduction and clustering algorithms. The pipeline proceeded in four stages: first, all explanations were concatenated and preprocessed through standard natural language processing operations including tokenization, lemmatization, lower-casing, and stop-word removal, retaining content words with clear urban and perceptual relevance. Second, each cleaned document was encoded into a high-dimensional semantic vector using a pre-trained sentence transformer (specifically, the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model), yielding an embedding matrix

, where n denotes the number of documents and d the embedding dimension. Third, we applied Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) to reduce

to a lower-dimensional manifold

, preserving local neighborhood structure while facilitating subsequent clustering. Fourth, Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (HDBSCAN) partitioned

into coherent topic clusters, automatically determining the number of topics and identifying outlier documents. Formally, the topic assignment for document

is given by

where

denotes class-based term frequency–inverse document frequency weighting,

represents the token set of documents

, and

is the j-th topic cluster. Each discovered topic is characterized by its top-ranked terms under the

metric, which we interpret through a dual-layer framework: a physical-environment layer encompassing-built form, public realm, greenery, and circulation infrastructure, and a perception layer capturing orderliness, activity, and legibility. This data-driven approach obviates the need for predefined taxonomies, allowing thematic categories to emerge organically from the corpus while maintaining interpretability for urban planning practitioners.

For comparative analysis and visualization, we first constructed a two-dimensional semantic embedding space by further reducing the UMAP coordinates via t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) or by retaining the first two UMAP dimensions, producing a global semantic scatter that positions representative topic centroids and high-frequency keywords according to their distributional affinity and thematic coherence. We then aggregated topic prevalence—defined as the proportion of documents assigned to each topic—across renewal categories derived from quantile-based stratification of overall perception scores, generating grouped bar charts that reveal how explanatory themes distribute differentially among low-, medium-, and high-quality urban environments. Finally, we extracted the top-20 keywords by weight across all topics and projected them onto the semantic scatter, color-coded by renewal category, to highlight which perceptual cues most strongly concentrate within each stratum. Taken together, this BERTopic-driven pipeline translates unstructured textual rationales into planner-facing evidence, aligning latent semantic structures with spatial perception patterns and furnishing actionable insights for subsequent diagnostic and design interventions.

2.5. Spatial Analysis

We systematically mapped six urban perception dimensions across the study area to examine their spatial distribution patterns. To quantify the overall spatial clustering tendency of each perception dimension, we employed Moran’s I statistic using a Queen-contiguity spatial weights matrix, where spatial units are considered neighbors when sharing either an edge or a corner. The global Moran’s I is calculated as:

where

represents the number of spatial units,

is the perception value at location

,

is the mean perception value across all locations, and

is the spatial weight between locations

and

. The statistical significance of spatial clustering was assessed using the standardized z-score:

where

represents the expected value under the null hypothesis of no spatial autocorrelation.

Building on the global analysis, we conducted Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis to identify localized clustering patterns and spatial outliers. The local Moran’s I statistic for each location

is defined as:

where

is the sample variance. LISA cluster maps were generated for each perception dimension, categorizing spatial units into four distinct types: High-High (HH) clusters representing locations with high perception values surrounded by high-value neighbors, Low-Low (LL) clusters indicating locations with low perception values surrounded by low-value neighbors, High-Low (HL) outliers denoting locations with high perception values surrounded by low-value neighbors, and Low-High (LH) outliers representing locations with low perception values surrounded by high-value neighbors. Statistical significance of local clustering was determined using conditional permutation tests with 999 Monte Carlo simulations at

.

Figure 2.

Pipeline of respondent-persona scoring and expert planning with structured outputs.

Figure 2.

Pipeline of respondent-persona scoring and expert planning with structured outputs.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation heatmap (r) between model predictions and the human benchmark across the six perception dimensions.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation heatmap (r) between model predictions and the human benchmark across the six perception dimensions.

Figure 4.

Spatial mapping of six perception dimensions.

Figure 4.

Spatial mapping of six perception dimensions.

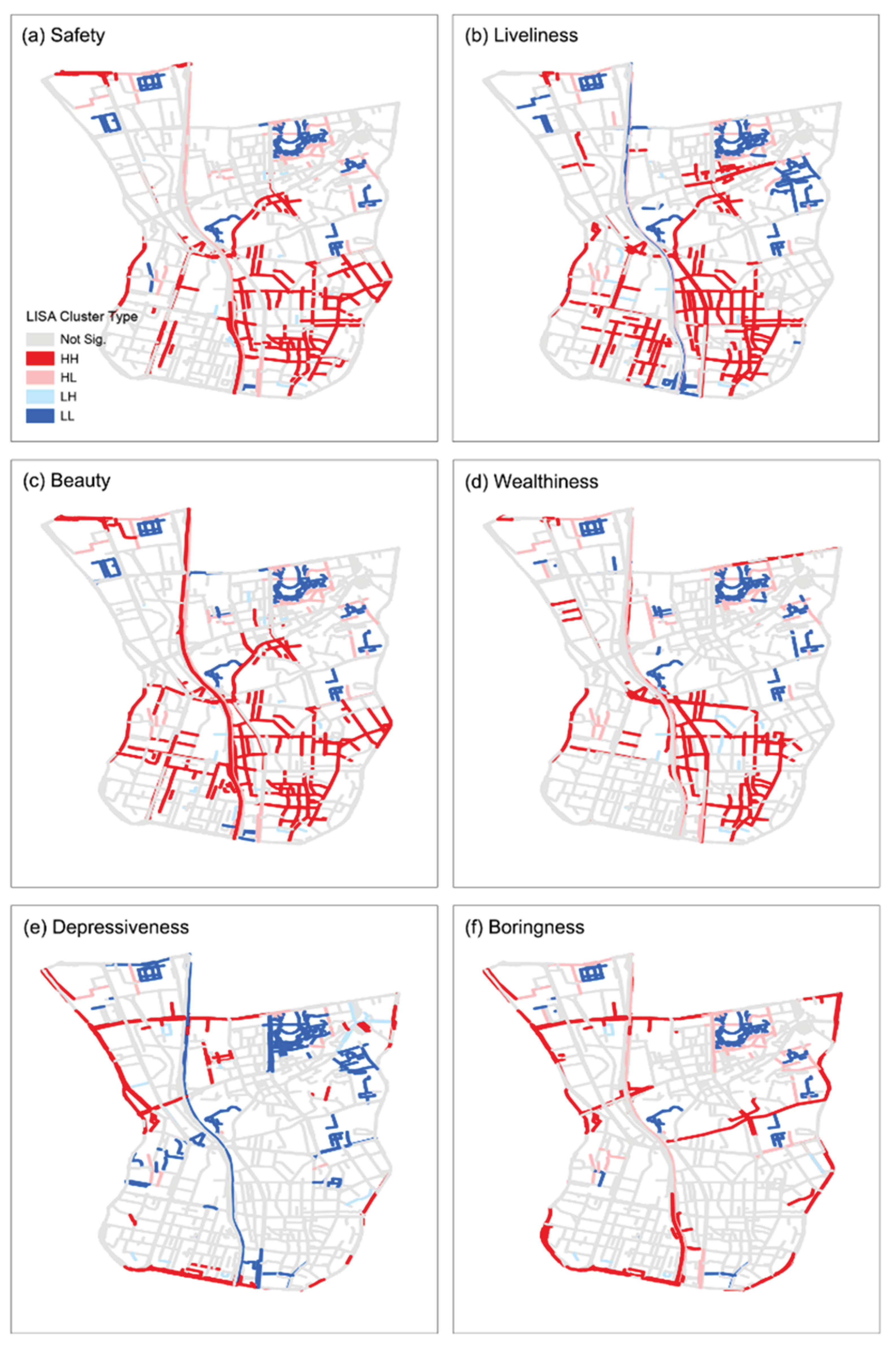

Figure 5.

Local spatial autocorrelation (LISA) cluster maps for six perceptual dimensions. Red lines indicate High–High clusters (areas where high perception values are surrounded by other high values), and dark blue lines indicate Low–Low clusters (low perception values surrounded by low values). Light red and light blue lines correspond to High–Low and Low–High spatial outliers, representing locations where perception values differ significantly from their neighboring contexts. Grey lines denote areas without statistically significant spatial autocorrelation (p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Local spatial autocorrelation (LISA) cluster maps for six perceptual dimensions. Red lines indicate High–High clusters (areas where high perception values are surrounded by other high values), and dark blue lines indicate Low–Low clusters (low perception values surrounded by low values). Light red and light blue lines correspond to High–Low and Low–High spatial outliers, representing locations where perception values differ significantly from their neighboring contexts. Grey lines denote areas without statistically significant spatial autocorrelation (p < 0.01).

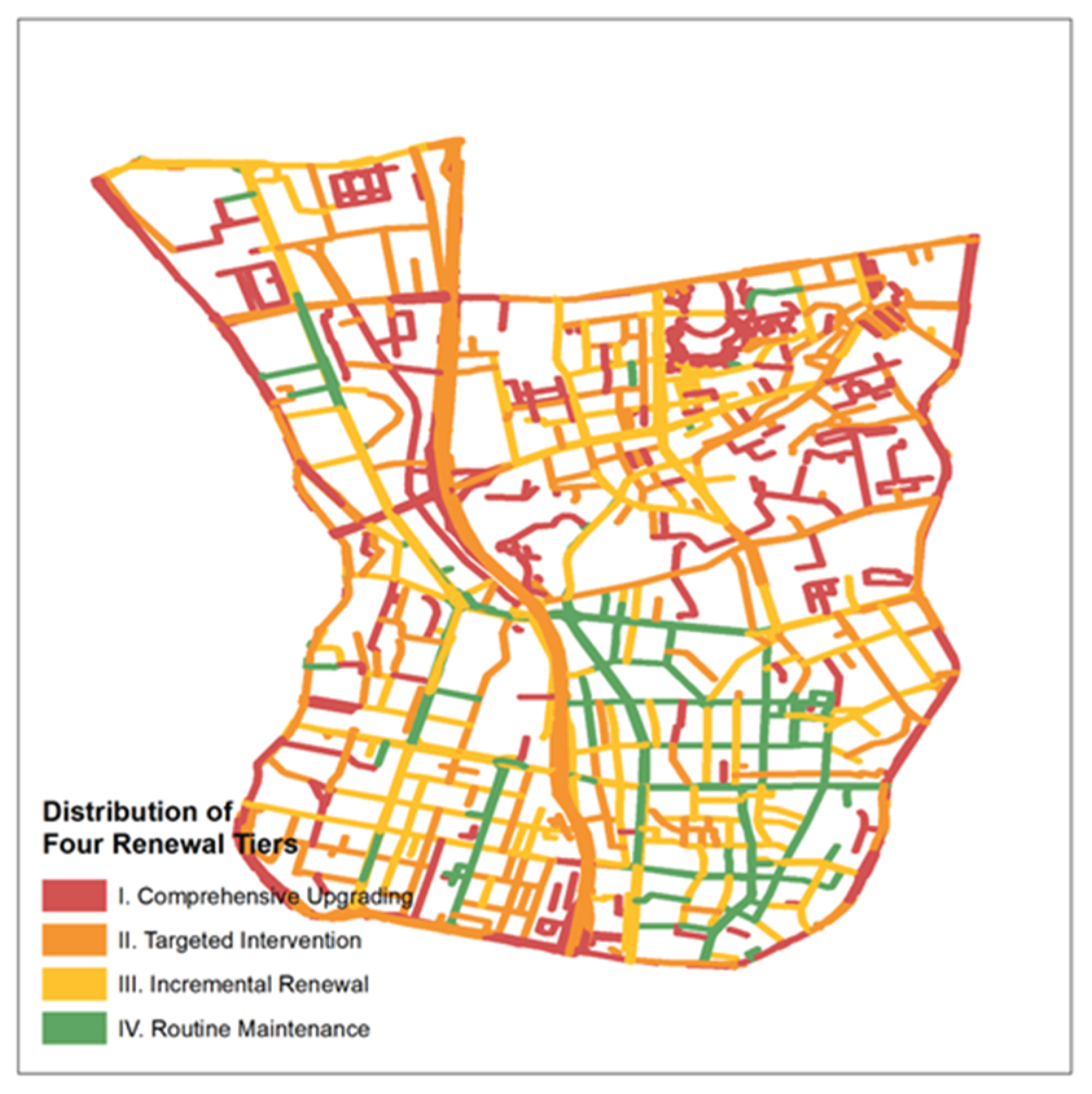

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of the four renewal tiers in the Hongshan Central District.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of the four renewal tiers in the Hongshan Central District.

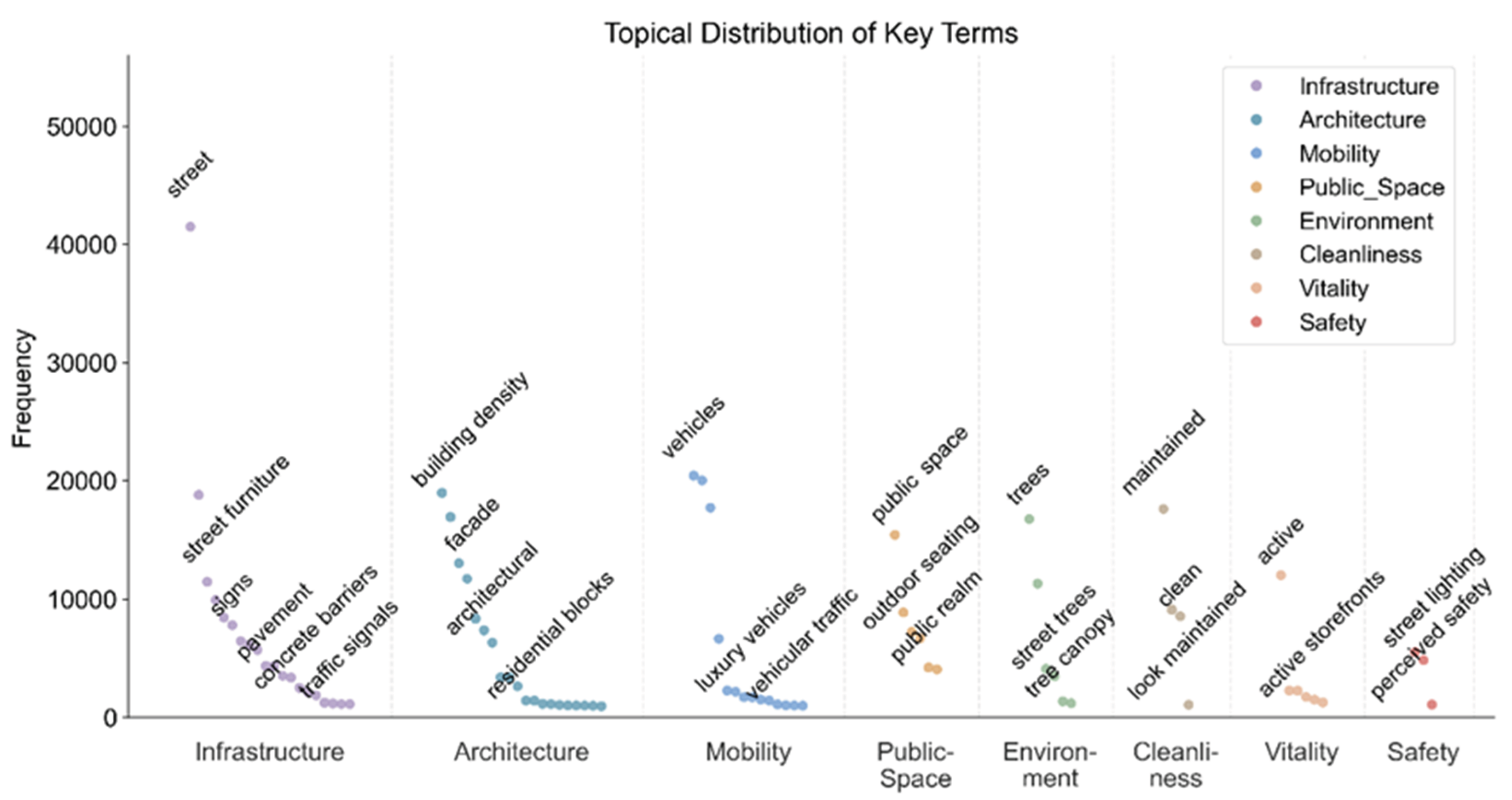

Figure 7.

Overall topical frequency distribution of model-generated descriptions.

Figure 7.

Overall topical frequency distribution of model-generated descriptions.

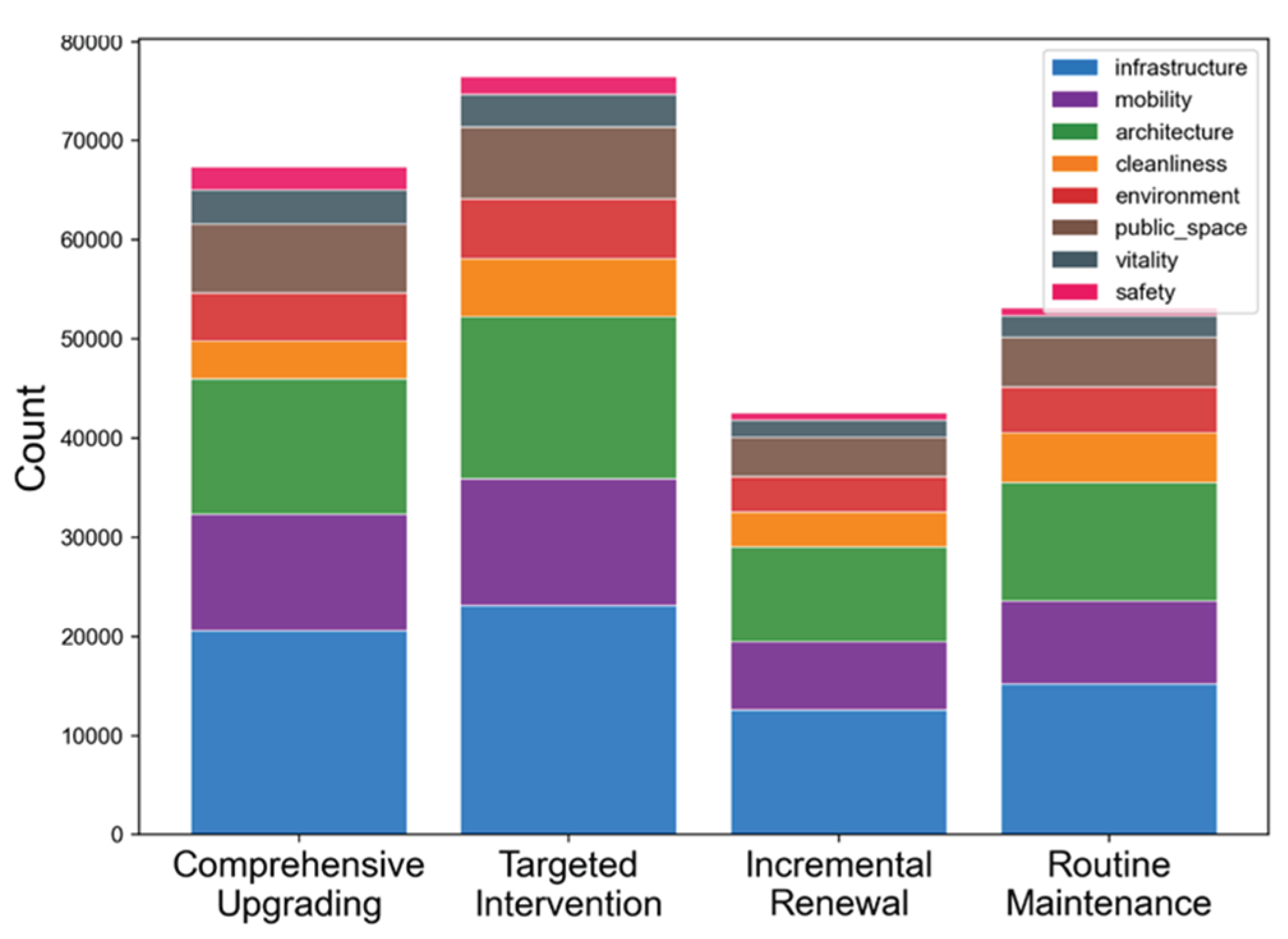

Figure 8.

Distribution of eight semantic themes across four renewal categories based on overall perceptual score (scoreAVG). Each bar represents the cumulative frequency of keywords belonging to eight major themes (infrastructure, mobility, architecture, cleanliness, environment, public space, vitality, and safety) within the corresponding renewal class (Comprehensive Upgrading, Targeted Intervention, Incremental Renewal, and Routine Maintenance).

Figure 8.

Distribution of eight semantic themes across four renewal categories based on overall perceptual score (scoreAVG). Each bar represents the cumulative frequency of keywords belonging to eight major themes (infrastructure, mobility, architecture, cleanliness, environment, public space, vitality, and safety) within the corresponding renewal class (Comprehensive Upgrading, Targeted Intervention, Incremental Renewal, and Routine Maintenance).

Figure 9.

Global scatter of the top 20 keywords (overall score). Colors denote four renewal categories: Comprehensive Upgrading (lowest-score tier), Targeted Intervention (lower-score tier), Incremental Renewal (mid-high-score tier), and Routine Maintenance (highest-score tier).

Figure 9.

Global scatter of the top 20 keywords (overall score). Colors denote four renewal categories: Comprehensive Upgrading (lowest-score tier), Targeted Intervention (lower-score tier), Incremental Renewal (mid-high-score tier), and Routine Maintenance (highest-score tier).

Figure 10.

Locations of six representative AOIs and anchor points. Orange polygons show AOI boundaries; colored dots are the representative street-view points (red = high-perception, blue = low-perception). IDs: (1) low-score school area (P1), (2) high-score school area (P2), (3) low-score commercial street (P3), (4) high-score commercial street (P4), (5) low-score residential block (P5), (6) high-score residential block (P6). This map supports the comparative analysis of P1–P6 cases that follows.

Figure 10.

Locations of six representative AOIs and anchor points. Orange polygons show AOI boundaries; colored dots are the representative street-view points (red = high-perception, blue = low-perception). IDs: (1) low-score school area (P1), (2) high-score school area (P2), (3) low-score commercial street (P3), (4) high-score commercial street (P4), (5) low-score residential block (P5), (6) high-score residential block (P6). This map supports the comparative analysis of P1–P6 cases that follows.

Figure 11.

Representative AOIs (P1–P6): panoramas, proportion of eight semantic themes, six-dimensional scores, and top terms of each dimension.

Figure 11.

Representative AOIs (P1–P6): panoramas, proportion of eight semantic themes, six-dimensional scores, and top terms of each dimension.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants (n=500).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants (n=500).

| Characteristic |

Category |

n |

Percentage (%) |

| Age Group |

18-30 years |

198 |

39.6 |

| 31-45 years |

186 |

37.2 |

| 46-60 years |

116 |

23.2 |

| Gender |

Male |

247 |

49.4 |

| Female |

253 |

50.6 |

| Residential Status |

Locals |

342 |

68.4 |

| Non-locals |

158 |

31.6 |

| Education Level |

High school |

89 |

17.8 |

| Undergraduate |

276 |

55.2 |

| Graduate |

135 |

27.0 |

| Occupation |

Students |

156 |

31.2 |

| Office workers |

189 |

37.8 |

| Service industry |

78 |

15.6 |

| Others |

77 |

15.4 |

Table 2.

Accuracy of GPT-5-Mini relative to human ratings across the six perception dimensions.

Table 2.

Accuracy of GPT-5-Mini relative to human ratings across the six perception dimensions.

| Perception Dimension |

R² |

RMSE |

MSE |

| Safety |

0.319 |

0.544 |

0.295 |

| Liveliness |

0.517 |

0.654 |

0.427 |

| Beauty |

0.374 |

0.515 |

0.266 |

| Wealthiness |

0.221 |

0.612 |

0.375 |

| Depressiveness |

0.273 |

0.705 |

0.497 |

| Boringness |

0.291 |

0.583 |

0.340 |

| Overall Average |

0.332 |

0.602 |

0.367 |

Table 3.

Table 3. Global Moran’s I Results for Six Perceptual Dimensions.

Table 3.

Table 3. Global Moran’s I Results for Six Perceptual Dimensions.

| Perception Dimension |

Moran’s I |

Z-Score |

p-Value |

| Safety |

0.441 |

25.216 |

<0.001 |

| Liveliness |

0.490 |

27.942 |

<0.001 |

| Beauty |

0.453 |

25.868 |

<0.001 |

| Wealthiness |

0.463 |

26.420 |

<0.001 |

| Depressiveness |

0.563 |

32.115 |

<0.001 |

| Boringness |

0.478 |

27.269 |

<0.001 |