1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common type of acute leukemia in adults, with a reported incidence of 3-5 per 100,000 individuals . The major determinants of prognosis include age, performance status, comorbid conditions, and cytogenetic and molecular characteristics of the leukemic clone. Following standard induction therapy, complete remission (CR) can be achieved in 50- 75% of patients with AML, except for those with AML-M3 [

1]. Most patients with CR recur unless intensive chemotherapy, autologous transplantation,or allogeneic transplantation is administered for consolidation [

2]. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is the most effective therapeutic approach for patients after remission.consolidation with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation represents an alternative therapeutic option in the absence of related or unrelated donors, elderly patients or patients with good or standard risk. Although autologous transplantation offers certain advantages, such as easy harvesting of the graft, practicality in elderly patients, absence of graft versus host disease (GVHD), and lower morbidity and mortality, it is also associated with a higher risk of relapse due to the lack of the graft versus leukemia effect [

3].

Later 1970s saw the introduction, auto-HSCT was introduced in AML CR1 and CR2 patients with no sibling donors; it was initially performed using bone marrow and subsequently with peripheral stem cells. In the absence of fully matched sibling donors for intermediate risk AML CR1 patients, a comparison of consolidation therapy with autologous transplantation or chemotherapy showed longer leukemia-free survival (LFS) than the former therapeutic approach [

4,

5]. The use of peripheral blood for autologous transplantation as the source of stem cells resulted in a decreased transplant-related mortality (TRM) rate, which fell from 15-20% to 5-10% [

6].

In our center, consolidation with auto-HSCT in AML patients is performed in subjects with good or intermediate 1 risk categories according to ELN criteria or in subjects with intermediate 2 or poor risk categories who have no related or unrelated donor. [

7]

This retrospective analysis evaluated data from 47 AML patients who underwent autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation between November 2012 and March 2023 at the Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit of Medicalpark Izmir Hospital. Factors affecting OS and PFS are also examined.

Evaluation and Definitions

PFS was defined as the time from transplantation to relapse or death from any cause, and OS was defined as the date of diagnosis to death or the last follow- up. Engraftment was demonstrated by increased neutrophil and platelet counts unsupported by transfusions. Neutrophil engraftment after transplantation was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) exceeding 500/mL for three consecutive days. The first of these 3 consecutive days was considered the day of engraftment. Platelet recovery was defined as the time after transplantation needed to achieve a blood platelet count exceeding 20,000/mL without transfusion support for two consecutive days.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was a retrospective evaluation of data from 47 patients with AML who underwent autologous hematopoietic stem -cell transplantation at Izmir Medicalpark Hospital between November 2012 and March 2023. All patients received a regimen including busulfan and cyclophosphamide at myeloablative doses (busulfan 3.2 mg/kg/day for /4days, cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg/day for/2 days) and autologous peripheral hematopoietic cells harvested from peripheral blood and stored at -80 C were administered via a central venous line after thawing.

As an infection prophylaxis strategy, all patients were admitted to isolated HEPA filter rooms with visitor restriction in the bone marrow transplant unit. All subjects received prophylaxis with levofloxacin 500 mg per oral, acyclovir 400 mg per oral 3 times daily, and fluconazole 400 mg per oral, before the onset of fever.

2.1. Cytogenetic Analysis

Bone marrow aspiration material or peripheral blood was collected into 5 cc heparinized tubes for the purposes of the study. Bone marrow aspiration samples were studied by applying the 24-hour or overnight culture method. Peripheral blood samples were studied by modifying the 72-hour culture method developed by Moorehead et al. [

8].

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables, median (minimum-maximum) for skew-distributed continuous variables, and frequencies for categorical variables. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. The means of normally distributed continuous variables were compared osing analysis of variance. Skew-distributed continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. OS was calculated as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of the last contact or death. LFS was calculated from diagnosis until the last follow-up or until leukemic progression. Cox regression analysis was used for multivariate analysies. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago) was used for the analysis, and a two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

Of the study subjects, 24 (51.1%) were female and 23 (48.9%) were male. The median age at diagnosis was 39 years (range: 18-68 y). The median Hemoglobin level , leukocyte count, and bone marrow blast percentage at the time of diagnosis were 8 g/dl (3.5-12.3 g/dl), 36700/mm3 (2000-270.000/mm3), and 76% (23-97%), respectively (

Table 1).

ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance score at the time of diagnosis was 0 in seven patients (14.9%), 1 in 37 patients (78.7%), and 2 in three patients (6.4%). With regard to ELN risk scores, cytogenetic and molecular analyses were performed in 44 patients at the time of diagnosis, and 22 (50%), 14 (31.8%), and 8 (18.2%) patients had good, intermediate, and poor risk statuses, respectively.

The patient population consisted of patients in the good-risk group and those in the moderate- risk group who had no related or unrelated allogeneic donors. Autologous transplantation was performed, and all the patients were in remission.

In terms of molecular characteristics, 10 patients were negative for in molecular markers, while 11 patients presented NPM (nucleophosmin) positivity only, 6 patients had FLT3-ITD positivity only, 4 patients had combined NPM and FLT3-ITD positivity, 4 had t(8,21) positivity, 4 had inversion 16 positivity, and 2 had 11q23 positivity (

Table 2).

Thirty-five of the 47 patients (74.5%) responded to first-line remission induction therapy consisting of 7+3 cytosine arabinoside (ara-C) 200 mg/m2/day/ 7 days and daunorubicin 60 mg/m2/day/3 days. In 12 patients, CR1 was achieved with second-line remission induction. As second-line remission induction therapy, EMA (etoposide-mitoxantrone- cytosine arabinoside) was administered to eight patients, and four patients received 7+3 ara-C-daunorubicin treatment again.

Auto-HSCT was performed in 45 patients with CR1 and two patients with CR2.

Until transplantation, 19 (40.4%) patients received 2 cycles, 12 (25.5%) patients received 3 cycles, and 12 (25.5%) patients received 4 cycles of treatment. As a mobilization regimen, 19 patients (40.4%) received 6+3 high-dose ara C-daunorubicine, 13 patients (27.7%) received etoposide (375 mg/m2 per day for/2 days), 9 patients (19.1%) received high-dose ara-C, 4 patients (8.5%) received 5+2 ara C-idarubicine, and 2 patients (4.3%) received the EMA regimen. The patients were mobilized using using consolidation treatment. We failed to collect sufficient stem cells in 17 patients; we administered etoposide to 13 patients , 5+2 ara C-idarubicine to 2 patients, and HIDAC (high dose cytosine arabinoside) to 2 patients as mobilization regimens.

After chemotherapy, all patients received filgrastim 0.5 MU/kg/day during a collection of stem cells. Apheresis was performed for a median of 2 days (1-5 days).

The mean CD34 count in the administered product was 10.14x106/kg (4.56-53.34x106). Patients with positive molecular markers were mobilized to second-line consolidation therapy, after achieving negative results following remission. The same molecular markers were re-tested in the product, and negative products for these molecular markers were used. The average time between diagnosis and transplantation was 7.94 months (2-90 months).

All patients received busulfan (3.2 mg/kg/day for /4 days IV), and cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg/dayfor/ 2 days) as a preparative regimens. At the time of transplantation, 3 patients (6.4%) were free of mucositis, and 25 (53.2%) and 19 (41.4%) patients had grade 1-2 and grade 3-4 oral mucositis. After transplantation, neutrophil engraftment occurred at a median duration of 11 days (9-19 days), and platelet engraftment occurred at 21 days (9-110 days). During transplantation, patients received 2.7 units of erythrocytes (0-11 U) and 4.74 units of apheresis platelets (0-23 U) on average.

Forty-one patients (87.2%) experienced neutropenic fever during transplantation. Catheter infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and possible invasive pulmonary aspergillosis were detected in 19, 7, 8, and 3 patients, respectively. In the first 100-day period, there was only one death, due to a gram-negative infection in a subject with no neutrophil engraftment.

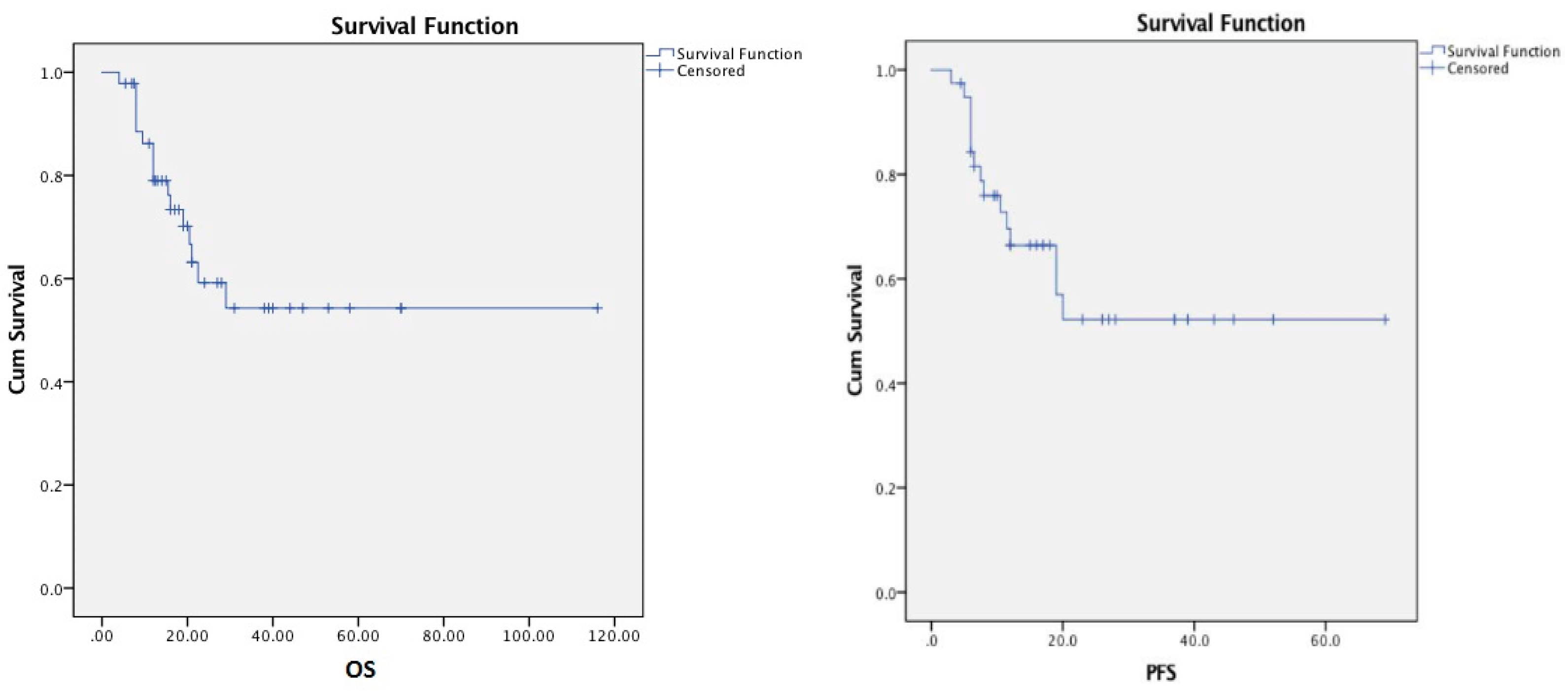

The mean OS from diagnosis to the last follow-up or death was 26 months (4-116 months), and the PFS was 20 months (3-69 months) (

Figure 1).

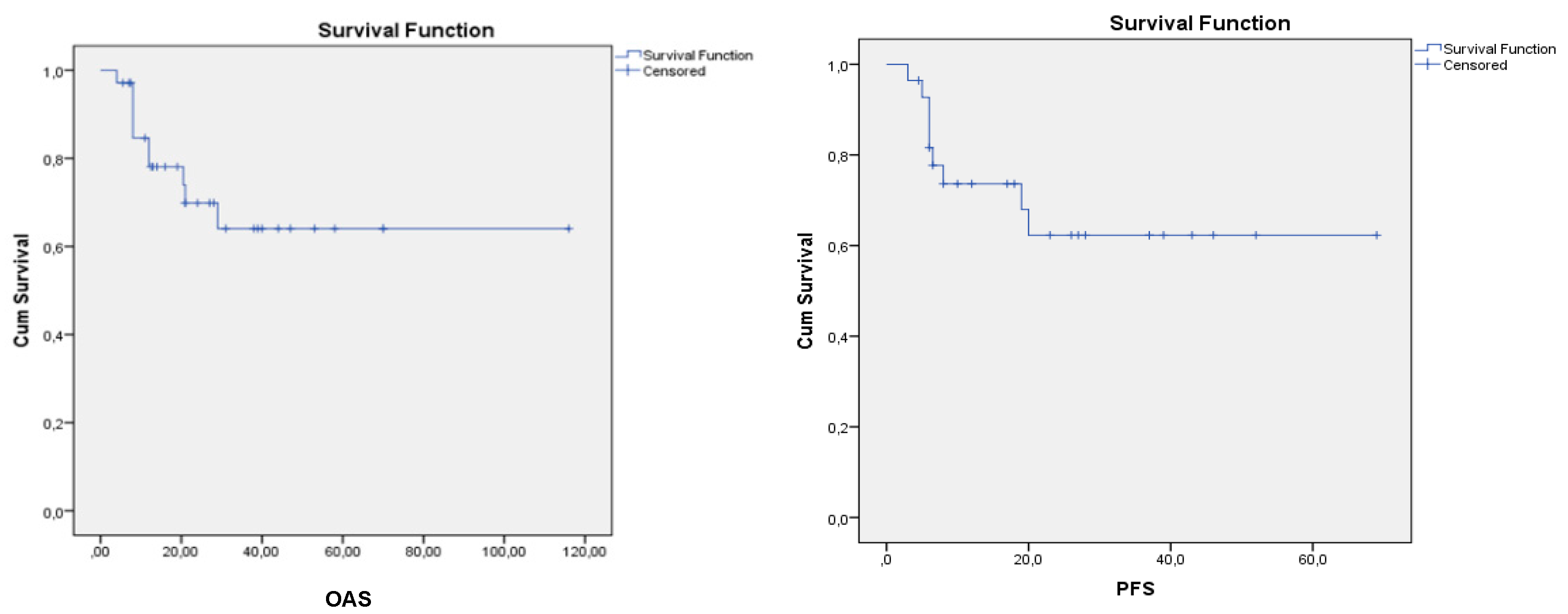

45 patients underwent transplantation with CR1, and17 of the 45 patients died during follow-up. The OAS and PFS graphies of patients undergoing transplantation in CR1 are shown in

Figure 2.

An assessment of the factors that influenced OS and PFS showed no significant association of NPM positivity, sex risk group, response to the first chemotherapy, transplantation at CR1 or CR2, LDH, CD34 count, and day of neutrophil engraftment with OS or PFS. In patients with FLT3 positivity, OS was significantly shorter (p < 0.05), whereas PFS was not significantly different (p: 0.21).

OS was longer in those with earlier platelet engraftment (p: 0.004), whereas genetic risk groups had no statistically significant effect on OS and PFS (p: 0.093, p: 0.57).

In the last evaluation, 17 of the 47 patients died (36.2%), and 30 (63.8%) were alive. Two FLT3-positive patients and all FLT3-NPM-positive patients (four patients) died during follow-up.

The causes of death were as follows: infection in one patient without neutrophil engraftment during transplantation, acute hepatitis B infection in one patient, autoimmune disease and pneumonia in one patient after transplantation, AML relapse and central nervous system bleeding in one patient, AML relapse and lung cancer in one patient, and disease progression and infection during chemotherapy with relapse in another eight patients. Four patients had MDS (myelodysplastic syndrome) after transplantation, and one these patients received unrelated allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. After transplantation, this patient died of lung infection, while two other patients died of post-chemotherapy infection. One patient remains alive. In one patient with recurrent disease, allogeneic transplantation from a fully -matched sibling donor was performed twice; however the patient died due to disease progression. The reason for not performing allogeneic transplantation in this patient was t(8,21)-positivity in the good-risk group.

4. Discussion

While consolidation therapy with allogeneic stem cell transplantation at CR1 is recommended by the ELN for AML patients in the intermediate and poor risk groups, allo-SCT is not recommended for AML patients with good risk [

7]. The incidence of relapse in patients with good and intermediate risk status may be as high as 30-40% and 50- 60%, respectively, after consolidation with chemotherapy.

Most patients undergoing consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy relapse within 2-3 years of treatment [

9]. In the last two decades, patients with good risk status, as well as those with no related or unrelated donors, have undergone consolidation therapy with auto-HSCT [

10,

11].

In a meta-analysis published in 2004 involving 1044 AML-CR1 patients, a comparison of consolidation therapy with either auto-SCT or chemotherapy revealed a lower relapse rate, better leukemia-free survival, and similar OS in the former group of patients [

12]. In the absence of fully-matched sibling donors in intermediate-risk AML CR1 patients, autologous transplantation and chemotherapy were compared as consolidation regimens, and patients who underwent autologous transplantation had a longer LFS. The use of peripheral blood as a source of stem cells for autologous transplantation is associated with a decrease in TRM from 15-20 to % to 5-10% [

4,

6,

13].

Heini et al. found that elderly AML patients with ASCT had longer PFS (PFS: 16.3 vs. 5.1 months, P = 0.0166) and OAS (OS: n.r. vs. 8.2 months; P = 0.0255) than elderly AML patients without ASCT consolidation. In addition, elderly AML patients undergoing ASCT had comparable PFS (P = 0.9462) and OS (P = 0.7867) to AML patients aged < 65 years who received ASCT consolidation in CR1. Their data suggest that ASCT is an option for elderly patients with AML who appear to benefit from autologous consolidation in a similar way to younger patients with AML [

14].

A comparison of auto-SCT with allogeneic transplantation from fully a matched sibling donor transplantation (MSD-SCT) showed similar OS for both regimens, although the relapse rate was higher and TRM was lower with auto-SCT, while MSD-SCT was associated with an LFS advantage despite having a higher TRM [

15,

16].

In a phase III prospective randomized trial by HOVON and the Swiss group, consolidation with auto-SCT and high-dose chemotherapy was compared in AML CR1 patients, showing lower relapse rates (58% vs. 70%, p=0.02) and higher 5-year LFS (38% vs. 29%, p=0.065) in the auto-SCT group [

17].

In a retrospective analysis by (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research (CIBMTR), the 3-year LFS in AML patients undergoing auto-SCT at CR1 and CR2 was 50% and 30%, respectively. The CIBMTR The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Researc) recommends auto-SCT suitable for consolidation at CR1 in the absence of a fully-matched sibling donor [

18,

19,

20].

In our patient group, after a mean follow-up of 18.08 months (2.5-51 months) 14 patients died due to relapse (29.78%) and 3 patients (3.68%) died due to infection without a relapse, while 30 patients (63.8%) are still in remission. Again 1-year, 2-year and 3-year OS rates were 86.2%, 60%, and 55%, respectively, wheras the corresponding PFS rates were 74.2%, 55%, and 52%, respectively. OS and PFS did not differ significantly according to NPM positivity, cytogenetic risk group, response to the first chemotherapy, transplantation at CR1 or CR2, CD34 count in the product, or the day of neutrophil engraftment. FLT3-positive patients had a significantly shorter OS (p < 0.05), whereas PFS was not affected by FLT3 positivity(p = 0.21).

In a study by Nagler et al., who retrospectively analyzed EBMT(European bone marrow transplantation) data in 952 AML patients, the 2-year OS, LFS, relapse incidence (RI), and NRM among patients receiving IV busulfan prior to auto-SCT were 67%, 53%, 40%, and 7%, respectively; however, there was no significant difference in 2-year LFS and RI between 815 patients receiving transplantation at CR1 (%52 and %40, respectively) and 137 patients receiving transplantation at CR2 (58% and 35%, respectively). A comparison of cytogenetic groups showed a 2-year LFS of 63%, 52%, and 37% in patients with good, intermediate, and poor risk status, respectively (p=0.01) [

21].

In AML patients with normal cytogenetics and intermediate risk status, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the best therapeutic option in the presence of a fully -matched sibling donor. In a study by Mirzutani et al. involving patients receiving high-dose therapy supported by autologous stem cell transplantation in the absence of sibling donors, as well as patients undergoing transplantation from a fully EBMT(European bone marrow transplantation), LFS after auto-SCT was significantly shorter with increasing numbers of chemotherapy courses until remission in comparison with MUD-SCT. (match unrelated stem cell transplantation) There was no significant difference in OS and LFS between the other subgroups in other arm of the study [

22].

In the future, autologous transplantation in AML will be based on achieving MRD (minimal residual disease )-negative bone marrow prior to transplantation using monoclonal antibodies, epigenetic treatments, FLT3 inhibitors, and bi-specific monoclonal antibodies, followed by patient monitoring with MRD, and development of newer treatment modalities in cases with MRD positivity.

Author Contributions

S. Kahraman conducted the activities of designing and planning the study, designing the article, making statistics, and writing the article. S.Cagirgan found patients in the outpatient clinic, obtained blood samples, and evaluated the results.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethics committee approval regarding the study was obtained from the ethics committee of Izmir Katip Çelebi University Non-Interventional Ethics Committee with the date 03.01.2021 and protocol number 104 GOA, decision number 150.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AML |

Acute myeloid leukemia |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| LFS |

Leukemia-free survival |

| TRM |

Transplant-related mortality |

| HSCT |

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| allo-HSCT |

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation |

| MSD-SCT |

Matched sibling donor transplantation |

| MUD-SCT |

Match unrelated stem cell transplantation) |

| CR |

Complete remission |

| LDH |

Lactade dehidrogenase |

| FLT3 |

Fms like tyrozine kinase 3 |

| ELN |

European leukemia net |

| GVHD |

Graft versus host disease |

| ANC |

Absolute neutrophil count |

| SPSS |

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| ECOG |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| NPM |

Nucleophosmin |

| Ara-C |

Cytosine arabinoside |

| EMA |

Etoposide-mitoxantrone- cytosine arabinoside |

| HIDAC |

High dose cytosine arabinoside |

| MDS |

Myelodysplastic syndrome |

| CIBMTR |

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research |

| EBMT |

European bone marrow transplantation |

| MRD |

Minimal residual disease |

References

- Holowiecki J, Grosicki S.Giebel S, et al. Cladribine , but not fludarabine, added to daunorubicin and cytarabine during induction prolongs survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia : a multicenter,randomized phase 3 study . J Clin Oncol 2012: 30:2441-448.

- Löwenberg B. Emerging therapeutic options in acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology 2005: 1:123-127.

- Gorin NC.Autologous stem cell transplantation for adult leukemia, Curr Opin Oncol 2002:14:152-159.

- Usuki, K.; Kurosawa, S.; Uchida, N.; Yakushiji, K.; Waki, F.; Matsuishi, E.; Kagawa, K.; Furukawa, T.; Maeda, Y.; Shimoyama, M.; et al. Comparison of Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and Chemotherapy as Postremission Treatment in Non-M3 Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Complete Remission. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012, 12, 444–451. [CrossRef]

- Cassileth, P.A.; Harrington, D.P.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Lazarus, H.M.; Rowe, J.M.; Paietta, E.; Willman, C.; Hurd, D.D.; Bennett, J.M.; Blume, K.G.; et al. Chemotherapy Compared with Autologous or Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation in the Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Remission. New Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1649–1656. [CrossRef]

- Reiffers, J.; Stoppa, A.M.; Attal, M.; Michallet, M.; Marit, G.; Blaise, D.; Huguet, F.; Corront, B.; Cony-Makhoul, P.; A Gastaut, J.; et al. Allogeneic vs autologous stem cell transplantation vs chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: the BGMT 87 study.. 1996, 10, 1874–82.

- Hartmut D, Elihu E, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel , Blood 2017 129:424-447.

- Moorhead, P.S.; Nowell, P.C.; Mellman, W.J.; Battips, D.M.; Hungerford, D.A. Chromosome preparations of leukocytes cultured from human peripheral blood. Exp. Cell Res. 1960, 20, 613–616. [CrossRef]

- Chao Nj, Stein As, Long Gd, et al.: Busulfan/Etoposide – Initial experience with a new preparatory regimen for autologous bone marrow transplantation in patients with acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 1993; 81: 319-323.

- Mcmillan K, Goldstone Ah, Linch Dc, et al. High dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 1990; 76: 480-488 .

- Sierra, J.; Grañena, A.; García, J.; Valls, A.; Carreras, E.; Rovira, M.; Canals, C.; Martínez, E.; Puntí, C.; Algara, M. Autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia: results and prognostic factors in 90 consecutive patients.. 1993, 12, 517–23.

- Nathan, P.C.; Sung, L.; Crump, M.; Beyene, J. Consolidation Therapy With Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation in Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Meta-analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Cassileth, P.A.; Harrington, D.P.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Lazarus, H.M.; Rowe, J.M.; Paietta, E.; Willman, C.; Hurd, D.D.; Bennett, J.M.; Blume, K.G.; et al. Chemotherapy Compared with Autologous or Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation in the Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Remission. New Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1649–1656. [CrossRef]

- D. Heini, M.Berger, Seipel K. Consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission is safe and effective in AML patients aged > 65 years. Leukemia Research Volume 53, February, 2017, pages 28-34.

- Suciu, S.; Mandelli, F.; de Witte, T.; Zittoun, R.; Gallo, E.; Labar, B.; De Rosa, G.; Belhabri, A.; Giustolisi, R.; Delarue, R.; et al. Allogeneic compared with autologous stem cell transplantation in the treatment of patients younger than 46 years with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in first complete remission (CR1): an intention-to-treat analysis of the EORTC/GIMEMAAML-10 trial. Blood 2003, 102, 1232–1240. [CrossRef]

- Zittoun, R.A.; Mandelli, F.; Willemze, R.; de Witte, T.; Labar, B.; Resegotti, L.; Leoni, F.; Damasio, E.; Visani, G.; Papa, G.; et al. Autologous or Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation Compared with Intensive Chemotherapy in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and the Gruppo Page Italiano Malattie Ematologiche MaligNe dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) Leukemia Cooperative Groups. New Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Vellenga, E.; van Putten, W.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Verdonck, L.F.; Theobald, M.; Cornelissen, J.J.; Huijgens, P.C.; Maertens, J.; Gratwohl, A.; Schaafsma, R.; et al. Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 6037–6042. [CrossRef]

- Gorin, N.-C.; Labopin, M.; Blaise, D.; Reiffers, J.; Meloni, G.; Michallet, M.; de Witte, T.; Attal, M.; Rio, B.; Witz, F.; et al. Higher Incidence of Relapse With Peripheral Blood Rather Than Marrow As a Source of Stem Cells in Adults With Acute Myelocytic Leukemia Autografted During the First Remission. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3987–3993. [CrossRef]

- Gorin, N.-C.; Labopin, M.; Reiffers, J.; Milpied, N.; Blaise, D.; Witz, F.; de Witte, T.; Meloni, G.; Attal, M.; Bernal, T.; et al. Higher incidence of relapse in patients with acute myelocytic leukemia infused with higher doses of CD34+ cells from leukapheresis products autografted during the first remission. Blood 2010, 116, 3157–3162. [CrossRef]

- Keating, A.; DaSilva, G.; Perez, W.S.; Gupta, V.; Cutler, C.S.; Ballen, K.K.; Cairo, M.S.; Camitta, B.M.; Champlin, R.E.; Gajewski, J.L.; et al. Autologous blood cell transplantation versus HLA-identical sibling transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: a registry study from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research. Haematologica 2012, 98, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Nagler, A.; Labopin, M.; Gorin, N.-C.; Ferrara, F.; Sanz, M.A.; Wu, D.; Gomez, A.T.; Lapusan, S.; Irrera, G.; Guimaraes, J.E.; et al. Intravenous busulfan for autologous stem cell transplantation in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a survey of 952 patients on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1380–1386. [CrossRef]

- F.Saraceni, M.Labopin, N. Gorin,D. Blaise et all. Matched and mismatched unrelated donor compared to autologous stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: a retrospective , propensity score –weighted analysis from the ALWP of the EBMT Journal of Hematology Oncology 2016 September 2;9(1):79.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).