1. Introduction

Automating neural network design has been a long-standing goal in machine learning. Recent approaches, such as AutoML and NAS, have produced architectures through evolutionary search or reinforcement learning; however, these methods can be resource–intensive. The rise of large language models (LLMs) introduces a new paradigm: using LLMs to generate neural network architectures in code form. The NNGPT framework was one of the first to explore this idea, leveraging generative AI to propose and modify neural network designs [

2]. In this context, our work focuses on image captioning – a task that combines computer vision and natural language processing by generating textual descriptions for images – as a test–bed for LLM-driven NAS.

Designing an image captioning model typically involves selecting a robust CNN encoder (often pretrained on image classification) and a sequence decoder (such as an LSTM or Transformer [

6,

7]) to generate sentences. Rather than manually exploring architectural variations (e.g. different encoder backbones or attention mechanisms), we employ an LLM to propose novel architectures autonomously. This is enabled by LEMUR (Learning, Evaluation, and Modeling for Unified Research) – a dataset of neural network models developed to support the NNGPT project [

1]. LEMUR contains numerous vision models (ResNets, EfficientNet, ConvNeXt, ViT, etc.) which we treat as a library of building blocks. By providing the LLM with code snippets from these classification models as inspiration, we guide it to generate new hybrid models for captioning.

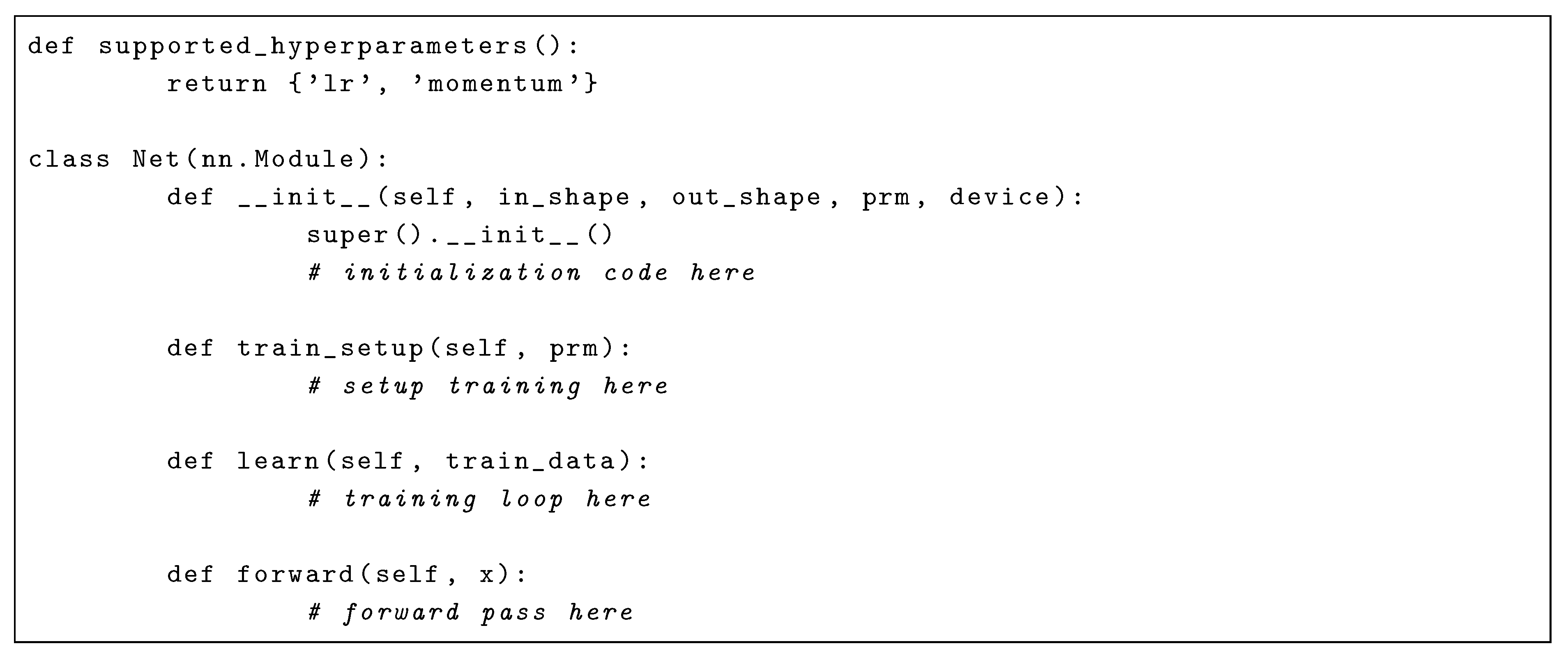

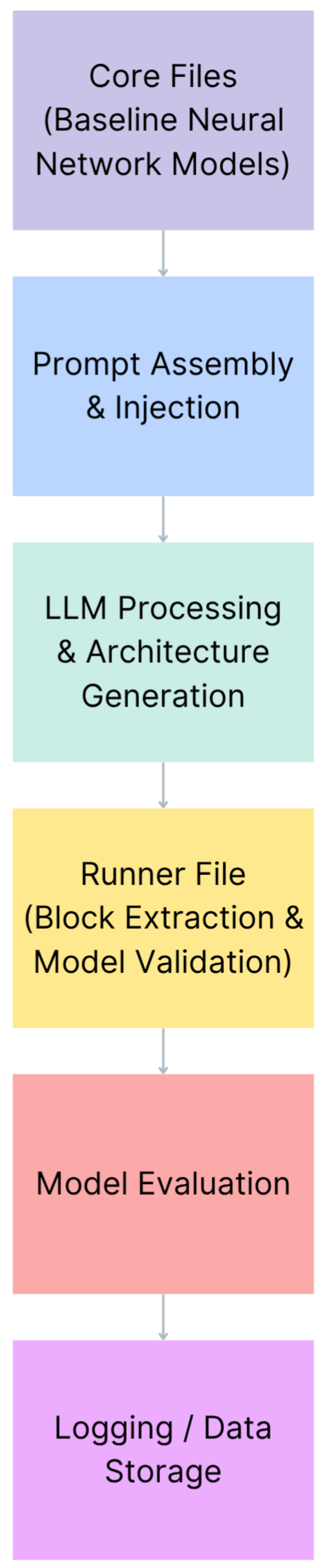

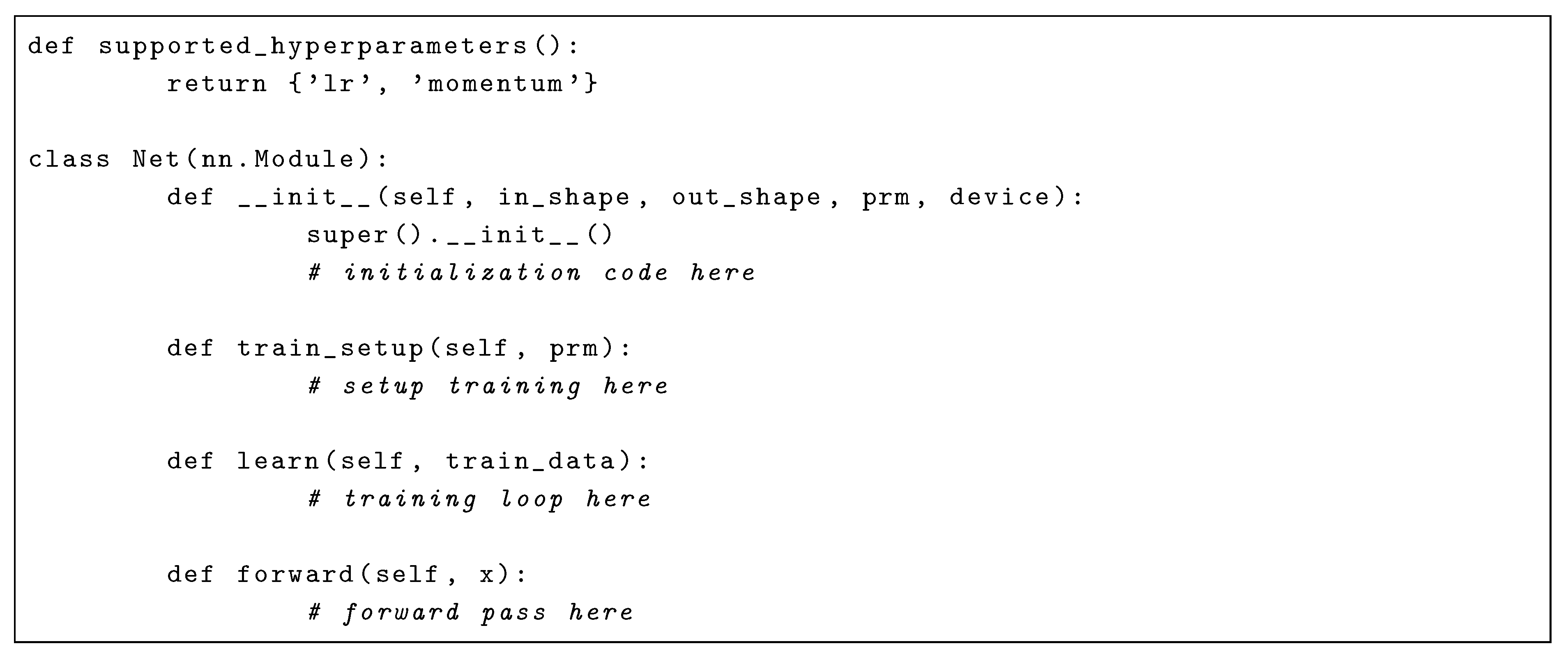

Our system, NN−Caption, integrates prompt engineering, code generation, and automatic training/evaluation. We craft a detailed prompt template that instructs the LLM to reuse a classification model’s backbone for the image encoder and to append or modify a decoder for caption generation. The prompt strictly defines an API (model class, methods, and shapes) that the output code must follow, ensuring the generated model can train within our pipeline. The LLM is thus tasked with inserting structural innovations (e.g., adding an attention layer, using a different decoder type, or adding squeeze-and-excitation blocks) while respecting the required interface. We highlight a snippet of the prompt in

Figure 1 and discuss it in the Methodology section.

We evaluated NN−Caption on the challenging Microsoft COCO dataset [

4], a standard for image captioning with 118k training images and 5k validation images. The LLM generated a range of candidate models, which we then trained for a few epochs to assess their performance (as measured by the BLEU−4 score [

5]) and feasibility. Our experiments varied the prompt inputs, including a comparison of using 5 vs. 10 different classification model code blocks as inspiration. We found that providing more model components increased the prompt length and sometimes confused the LLM, slightly reducing the success rate of valid model generation. Nevertheless, a substantial fraction of the generated networks were runnable and produced non–trivial captions. The best generated model (a CNN encoder with Transformer decoder) reached a BLEU−4 of

, outperforming the baseline captioning model we started from in just the first 3 epochs.

Table 1 summarises the number of models generated under each setting and how many were successful (trained without errors and improved metrics).

This paper is structured as follows. In Methodology, we describe the NN−Caption pipeline, including the design of the prompt, selection of the LLM, and code validation process. We also detail how classification models from LEMUR are integrated. In Experiments, we document the LLMs used, the model generation runs (5 vs 10 input models), and the training setup on MS COCO (including how we compute BLEU−4). The Results & Discussion section presents quantitative outcomes (training curves, BLEU scores) and qualitative analysis of the generated architectures, along with a discussion of the LLM’s behaviour (e.g. instances of hallucinated layers or API violations). We further analyze which architectural ideas were most effective. Finally, the Conclusion highlights the contributions of this work – demonstrating LLM-guided NAS for image captioning and expanding the pool of reusable models – and outlines future work, such as fine-tuning the LLM to reduce errors and applying this approach to other tasks.

2. Methodology

Overall Pipeline: Inspired by recent advancements in the application of LLMs across various domains [

8,

9,

10,

11], and leveraging the existing LEMUR dataset [

1,

12], we developed NN−Caption based on the NNGPT framework [

2,

13]. The functionality employs an iterative pipeline in which an LLM generates a model, evaluates its performance, and uses the resulting feedback to guide subsequent improvements.

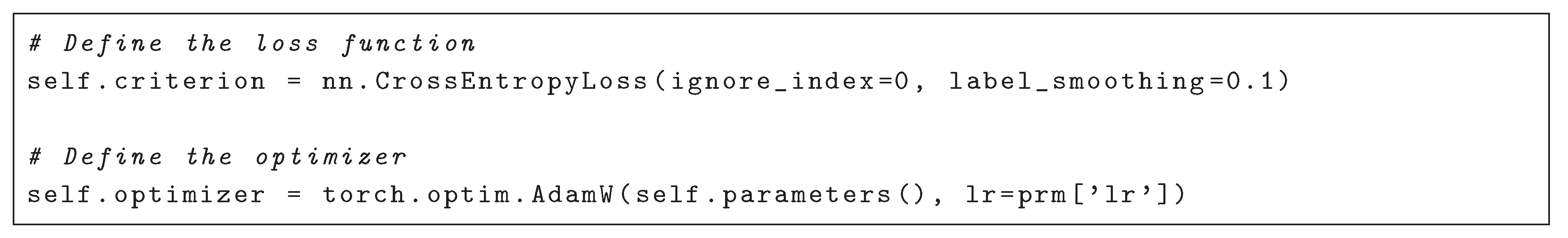

Figure 1 provides a schematic overview. The process begins with a prompt that includes an existing baseline image captioning model and several snippets of image classification models as input. The LLM then generates a new Python code file that defines a modified captioning network. This generated code is inserted into our training workflow, where the model is compiled and trained on the COCO dataset (for a fixed number of epochs) – the evaluation step. Finally, performance statistics (e.g., BLEU score, training loss) are collected. This closed loop allows for the analysis of which generated models succeeded or failed, informing refinements to the prompt or LLM for the next iteration.

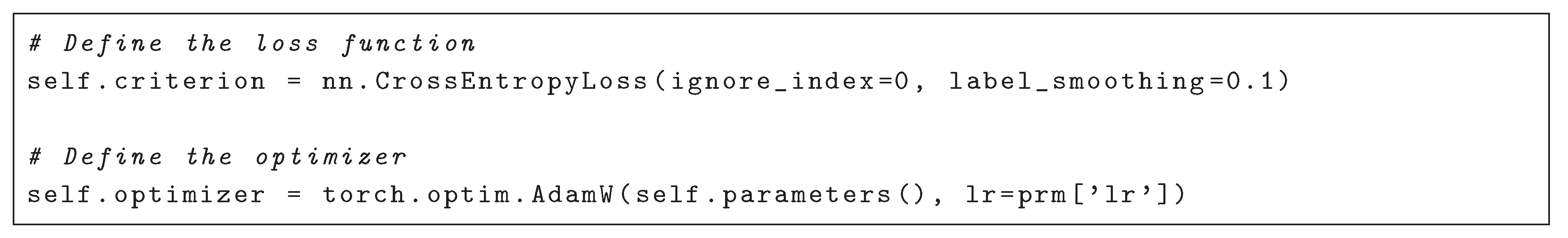

Prompt Design: Crafting the right prompt is crucial to guide the LLM in creating a valid and high-performing network. Our prompt has several components. First, we set a system role message instructing the LLM to output only code in a single fenced block (no explanations or partial answers). We then define the goal: for instance, “Your task is to generate a high–performance image captioning model by taking inspiration from classification model code blocks, and by making safe, meaningful structural tweaks to the target captioning model.” This explicitly instructs the LLM not to produce a classifier, but rather to modify the given captioning model using ideas from the classification snippets. We emphasize that the output must be a runnable Python file that conforms to a specific API. To enforce this, the prompt lists a mandatory API that the model code must implement, including functions and class methods. For example, the model must have

methods. These requirements ensure that any generated model can plug into our training framework (which expects those methods for training and inference) [

2].

We also include detailed technical instructions in the prompt. The LLM is instructed to reuse the encoder backbone from the classification models – “Remove the classification head from the chosen classification blocks. Keep the convolutional backbone for the encoder. Produce a feature tensor

via AdaptiveAvgPool2d and a Linear layer…”. This means the LLM should take, for example, a ResNet or EfficientNet, strip off its final classification layer, and use the remaining CNN to extract a feature vector (of dimension

, as specified). We allow alternative approaches for transformer-based encoders (ViT): returning patch tokens as encoder memory if applicable. Next, the prompt specifies the decoder choice: “YOU decide which decoder architecture best suits your chosen encoder... use either

or

”. We let the LLM select a decoder type (recurrent or transformer) and encourage it to adjust hidden sizes (e.g., 640 or 768) and heads if using multi-head attention (cf. [

7]). The prompt provides guidelines for each decoder type – for instance, if using an LSTM, to include an embedding layer and possibly an attention mechanism on the encoder feature; if using a Transformer, to use PyTorch’s

and

is properly implemented, with sensible defaults (e.g., 8 or 12 heads dividing the hidden size). We explicitly forbid certain pitfalls: no custom undefined classes (e.g.,

is not a real PyTorch class), no assuming a

argument in the Transformer (the prompt reminds that

should not be passed to the decoder’s constructor), and no complex custom attention beyond the standard multi–head attention.

Another essential section of the prompt covers training specifics and consistency of shape. We instruct that the model should train using teacher forcing: e.g., for input captions, use and predict the next-word logits for . The forward method must return a tuple where is a tensor of shape (so that it aligns with the target sequence length), and the code should include assertions to enforce this shape contract. The prompt also tells the LLM how to set up training in (moving the model to the device, defining

optimizer with specific hyperparameter handling). These instructions incorporate best practices to ensure the generated model is trainable out of the box. Finally, we list “Safe edits only” and “Diversity requirements”: the LLM should make at least three structural changes from the original model (ensuring the new model is non–trivial), but stay within safe modifications (e.g., add an SE block, change an LSTM to a Transformer, increase hidden layer sizes, etc., but do not remove essential components or break the required API). We even included hints like “larger hidden sizes and multi–head attention generally improve BLEU” and “keep dropout modest” to nudge the LLM toward high–performing configurations.

LLMs Used: We implemented the above prompt using different LLMs to compare their effectiveness. The primary model, referred to as DeepSeek-R1-0528-Qwen3-8B, is an 8-billion–parameter model that had shown strong code generation capabilities [

3]. We also experimented with a smaller, fine–tuned model (

parameters) and a

–parameter model to assess scalability. These models were accessed via local deployment (using HuggingFace Transformer implementations) due to the need for custom prompting and extracting code. We observed notable differences: the

model consistently adhered better to the prompt constraints (producing the required class and methods) and generated more coherent architectures. Smaller models often hallucinated nonexistent functions or forgot to include mandatory methods. For example, a

model sometimes returned an incomplete

class, missing the

method, or invented a layer name, such as

(which does not exist in PyTorch) – errors we specifically cautioned against. The larger

model, in contrast, was more reliable in following the detailed instructions, likely due to its greater capacity and the fact that it was a specialised variant (DeepSeek) with training to reduce such hallucinations. Based on initial trials, we selected the DeepSeek

model for the bulk of our experiments, as it yielded the highest ratio of valid, high–quality architectures.

Code Extraction and Verification: Once the LLM outputs a response, our system must extract the code and verify it. We developed a parsing utility to find the Python code block in the LLM’s output. In some cases, the LLM might produce extra text or multiple code blocks (despite instructions); our parser uses heuristics to pick the most likely complete code, prioritizing the block containing and other key components. We then apply a series of automated “fix–ups” to sanitize the code. These include removing any stray markdown fencing or annotations (from the DeepSeek model’s chain–of–thought), inserting missing imports, and normalizing specific patterns (for example, ensuring is present exactly once). A standard adjustment was made to guarantee that the function returns the correct set. We enforce that it returns only as required, overwriting any different content the LLM might have provided. Another check was for bracket matching: LLM outputs occasionally miss a parenthesis or bracket at the end, so we implemented a simple bracket balancer to append any needed closing brackets at EOF. After these fixes, we run Python’s AST parser to ensure the code is syntactically valid. If a syntax error is found, we loop back and prompt the LLM again in repair mode, supplying the error message and code, and asking the LLM to correct the mistake. This automated repair prompt is kept very strict (to avoid introducing new errors), and we allow up to 2 iterations of fixes. This step dramatically improved the success rate – many minor mistakes (like a missing colon or an undefined variable) could be fixed by the LLM itself when given the error feedback. After this, we treat the code as final and move to execution.

Integration with LEMUR and Training: The verified new model code is then integrated into the LEMUR dataset structure for training. The LEMUR library offers unified routines for training and evaluating models across various tasks. We add the generated model (which is a complete

class with a unique name) into LEMUR’s registry and initiate a training run on the image captioning task with the MS COCO dataset. Typically, we train each model for a small number of epochs (e.g., 3 epochs) due to resource constraints, and monitor the BLEU−4 metric on a validation subset after each epoch. Training uses the hyperparameters indicated by the model’s own

(usually learning rate and momentum); in some cases, the LLM suggests hyperparameter values, or we use default ones (learning rate

, etc.) if not specified. The LEMUR framework stores each model’s performance, as well as the model code, for analysis. By using LEMUR, we benefit from standardized data loaders (ensuring that, for example, COCO captions are preprocessed into indices with

and

tokens, matching the model’s expectations). This prevents misalignment issues – e.g., the ResNetTransformer baseline in LEMUR uses the

token index for loss ignore. Our prompt reminded the LLM to use

, which indeed corresponds to the pad token index in COCO’s vocabulary in LEMUR [

1].

In summary, our methodology combines a carefully engineered prompt (to propose viable architectures) with automated code validation and an existing training pipeline to quickly assess each generated model. By repeating this for multiple models and prompt variations, we accumulate a dataset of results that we analyze next.

3. Experiments

Training of computer vision models is performed using the AI Linux docker image

abrainone/ ai-linux1 on

GPUs of the

cluster at the University of Würzburg and a dedicated workstation.

We conducted a series of experiments to evaluate NN−Caption along two main axes: (1) the impact of different prompt configurations (particularly the number of classification model snippets provided), and (2) the performance of generated models in terms of training stability and caption quality. All experiments use the

image captioning dataset for training and evaluation [

4]. We use the standard train/validation split (training on 118k images, validating on 5k images, with captions tokenized to a vocabulary of

k words). The primary metric reported is BLEU−4, the 4-gram BLEU score widely used for captioning evaluation, computed on the validation set (no test server submission was made due to the experimental nature of the evaluation) [

5].

Baseline Model: As a starting point, we identified a baseline captioning model in LEMUR, which we denote

. This model uses a

encoder (pretrained on ImageNet) and an LSTM decoder. It roughly follows the architecture of Vinyals et al.’s Show–and–Tell but implemented in our framework [

6]. We trained this baseline for comparison and it achieved a BLEU−4 of

on validation. The baseline model’s code was used as the initial

in our prompt so that all LLM–generated models can be seen as variants or improvements upon this backbone.

Prompt Variations: We experimented with two settings for the prompt’s addon list (the classification model code blocks given as inspiration):

- 1)

5–classification models input: In this setting, we include code from 5 different image classification models from LEMUR. For each run, a random subset of 5 model snippets is sampled (excluding the one corresponding to the captioning model’s own encoder to avoid trivial copies). Examples of models whose snippets were used include EfficientNet−B0, ConvNeXt−T, DenseNet−121, VGG16, and . Each snippet typically consisted of a few key layers or blocks (e.g., a convolutional block with BatchNorm and ReLU from ResNet, or a self–attention block from ViT). The idea was to expose the LLM to a diverse set of architectural “ideas” in a small number.

- 2)

10–classification models input: Here, we doubled the number of snippets, providing 10 different classification model excerpts. The pool included the above models, as well as others such as MobileNetV2, Inception−v3, and SqueezeNet, aiming for even greater diversity. The prompt length increases significantly with 10 snippets, which could potentially overwhelm the LLM’s context or lead to further confusion.

We ran multiple generation rounds for each setting. For consistency, we used the DeepSeek-R1-0528-Qwen3-8B model for all generations in these comparisons, as it proved to be the most reliable. The temperature was set to to allow some creativity (as opposed to a deterministic output), and we generated one model per prompt (no beam search in the LLM decoding, since we prefer diverse single outputs). Each generated model was then automatically verified and trained for 3 epochs on COCO (with a batch size of 32, a learning rate of unless overridden, and using the training procedure defined in its method).

Results Collection: After training, we logged whether the model successfully trained (i.e., ran without runtime errors and produced finite loss/accuracy) and its final BLEU−4 score. Models that failed to train (due to code runtime errors, such as shape mismatches that slipped through verification or divergence, like NaN loss) were marked as failed. In our context, a “successful” model means that the code was valid and the model could learn to produce some meaningful captions (even if the BLEU score might be low). Among successful models, we further distinguish those that showed improved performance over the baseline vs. those that underperformed the baseline.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 1 lists the prefixes used in this study. Each entry corresponds to a schema-valid, runnable model archived with its prefix.

Table 1.

Generated models and counts.

Table 1.

Generated models and counts.

| Models (Prefix) |

Decoder Type |

# Models |

| C1C-RESNETLSTM |

LSTM |

1 |

| C5C-RESNETLSTM |

LSTM |

100 |

| C10C-RESNETLSTM |

GRU(+Attn) |

3 |

| C5C-ResNetTransformer |

Transformer |

250 |

| C8C-ResNetTransformer |

GRU (feat-init) |

3 |

| Total |

|

357 |

Table 2 summarizes BLEU−4 where available. We include two hand-engineered baselines (

and

) and compare them against generated prefix families under matched budgets.

Model Generation Outcomes: Initially, we generated 10 distinct model architectures (5 with the 5–snippet prompt and 5 with the 10–snippet prompt).

Table 1 summarises the counts of successful vs. failed models in each scenario. A model is counted as “failed” if it did not produce a valid training run; this included 3 cases where the LLM’s code passed initial syntax checks but raised runtime errors (e.g., dimension mismatch in tensor operations), and 5 cases where training was unstable (loss blew up to NaN, likely due to an ill–conditioned architecture). We see that using 5 inspiration models yielded a slightly higher success count (4 out of 5) compared to using 10 (only 3 out of 5 were successful).

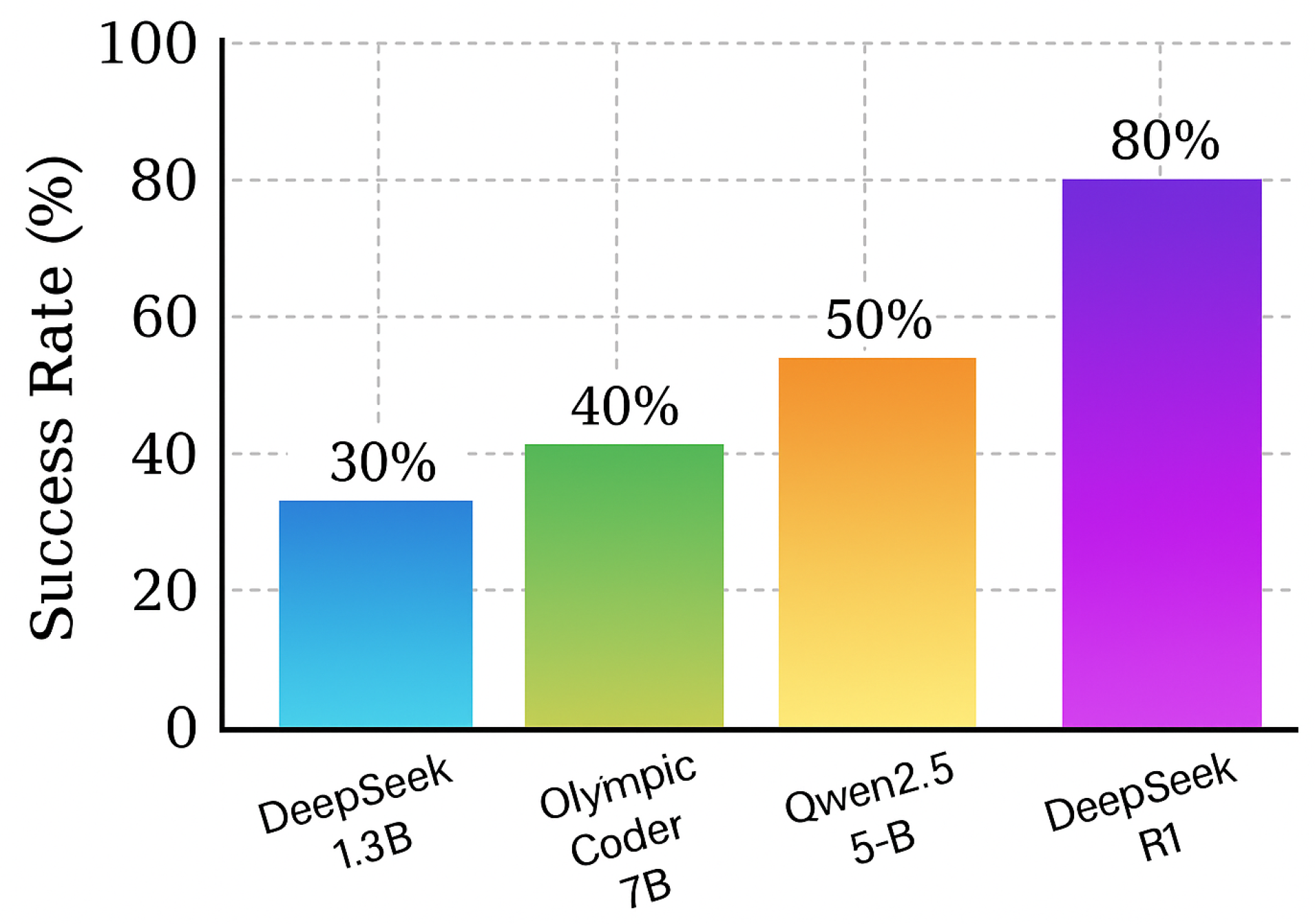

Figure 2 visualizes the success ratio. The drop in success with 10 models may be because the prompt became very lengthy and complex, increasing the chance the LLM introduced mistakes or overly ambitious designs. With 5 models, the prompt was concise enough for the LLM to focus on a few key modifications.

Success rates of generated models: For prompts with 5 classification model snippets vs. 10 snippets, the chart shows the number of generated captioning models that successfully trained (“Successful”) vs those that failed. Providing more inspiration models (10) resulted in a lower success ratio (only of models trained successfully) compared to using 5 models ( success), possibly due to prompt overload or LLM confusion.

From

Table 1, we note that even in the worst case (10–snippet prompts), a majority of the LLM’s outputs were valid models. This demonstrates a significant degree of reliability in the LLM when guided by our prompt – a noteworthy result, considering the complexity of the task (generating an entire multi–component network). The failed cases in the 10–model scenario often exhibited a familiar pattern: the LLM attempted to combine too many elements and lost track of the shapes. For example, one failed attempt attempted to insert multiple convolutional blocks from different models in sequence, resulting in a tensor of the wrong dimension being fed to the decoder. In another instance, the LLM attempted to implement a novel cross–attention mechanism that deviated from the prompt guidelines, resulting in mismatched tensor ranks. These failures highlight the limits of prompt guidance – the more freedom and information given, the more the LLM might venture into unsupported territory. On the other hand, the 5–snippet models were generally simpler and safer variations.

Characteristics of Generated Architectures: We now examine some of the successful models to understand the architectural innovations introduced by the LLM. We observed a diverse set of ideas:

Enhanced CNN Encoders: Many models retained a CNN backbone (often the same ResNet−50 from the baseline), as the LLM wasn’t explicitly asked to change the entire backbone – it could, but often chose to augment rather than replace. A common modification was to add a squeeze–and–excitation (SE) block or a CBAM () to the ResNet encoder path. For instance, one generated model inserted an SE module after the ResNet’s final convolutional block, as inspired by a classification snippet that contained an SE implementation. This model () achieved a BLEU−4 score of , slightly lower than the best model, indicating that channel–wise attention effectively focused the image features.

Alternative Encoders: In a few cases, the LLM did swap the encoder entirely. One notable architecture was a decoder model. The prompt included a snippet from ConvNeXt (a modern CNN architecture), and the LLM ultimately used ConvNeXt’s stem and stages to construct an encoder, rather than ResNet. It then attached a Transformer decoder. This model was successful in training and achieved a BLEU−4≈ score of approximately . Qualitatively, it generated slightly more descriptive captions than the baseline (likely due to the stronger visual features of ConvNeXt), although its performance was not the highest.

Recurrent vs. Transformer Decoders: Approximately half of the successful models utilised LSTM decoders, while the other half employed Transformer decoders. Interestingly, no GRU–based decoder was chosen by the LLM in our runs – even though GRU was allowed, the LLM seemed to prefer either sticking to LSTM (perhaps because the baseline and example had LSTM) or going for the more complex Transformer for a potential performance boost. We generated some models by forcibly inserting GRU as a decoder in Prompt to check. The Transformer–based models generally yielded higher BLEU scores. Our top model, which we call

, combined the ResNet−50 encoder (with some modifications) and a Transformer decoder with 768 hidden size and 8 attention heads. This model achieved a BLEU−4 score of

, the highest among the generated models. It closely mirrored the structure of the ResNetTransformer example provided in LEMUR. Still, the LLM introduced a learnable positional encoding and increased the number of decoder layers to 4 (compared to 6 in the LEMUR reference). The LSTM–based models tended to plateau at BLEU−4 in the range of

–

. We suspect the Transformer’s multi–head attention was able to better utilize the encoder features, as expected (and indeed our prompt hinted to the LLM that multi–head attention can improve BLEU [

7]).

Attention Mechanisms: Almost every Transformer decoder model is designed to naturally use attention. For the LSTM models, we saw that the LLM sometimes implemented a form of attention on the encoder output. In one example, the LLM added a simple additive attention: it learned a weight to multiply the encoder’s feature vector for each decoding timestep (akin to an attention that is basically a linear layer on the feature concatenated with the decoder’s hidden state).

5. Conclusion

We showed that schema-constrained, one-shot LLM generation integrated with LEMUR produces runnable and comparable captioning families with low trial counts and strong baseline competitiveness on COCO. Beyond captioning, the same contract enables diverse tasks (detection, segmentation) and deployment targets (mobile pipelines) without changing the evaluation backbone. All models comply with a unified API and are logged in SQLite, enabling controlled reuse and fair comparison; the same contract extends to other CV tasks. We release families, logs, and protocols to support reproducible AutoML research.

We presented NN-Caption, an LLM-guided neural architecture search approach that automatically generates image captioning models by drawing inspiration from existing neural network modules. Using a carefully crafted prompt and a powerful 8B parameter LLM (DeepSeek-R1-Qwen3-8B), we demonstrated that non-trivial model architectures can be composed autonomously – often satisfying strict structural requirements – and that many of these architectures can be trained to achieve better-than-baseline performance on a complex task (MS COCO captioning) [

4,

5]. Our approach integrates ideas from prompt engineering, software engineering (for code verification), and automated training pipelines, resulting in a novel end-to-end system for AI-driven model design (as summarized in Figure A).

While our best model’s BLEU score (0.1192) does not compete with hand-engineered state-of-the-art models, it is essential to emphasize that the LLM achieved this with minimal human intervention in the design process. The observed improvements validate that the LLM’s architectural suggestions – larger hidden sizes, attention mechanisms, and hybrid encoders – can translate into measurable gains. This showcases the potential of LLMs as NAS agents: they incorporate prior knowledge (e.g., known practical modules, such as SE blocks) and can apply them in new contexts.

We also highlighted the limitations and challenges. LLMs can hallucinate components, violate constraints, or produce suboptimal designs if not appropriately guided. Our use of rigorous prompt constraints and automated repair loops was essential to rein in the LLM’s creativity within workable boundaries. This points to an important future direction: fine-tuning the LLM on the task of network generation. By incorporating the outcomes (successes/failures, and performance metrics) of this study, we plan to fine-tune the LLM so that it learns to avoid common mistakes (e.g., shape mismatches) and focuses on changes that yield higher BLEU scores. A fine-tuned LLM could potentially generate architectures that are both valid and high-performing on the first attempt, reducing the need for a posterior repair cycle.

Another area for future work is expanding this methodology to other tasks beyond image captioning. The general paradigm of mixing and matching pieces of neural networks via LLM guidance applies to any domain where a library of models exists (e.g., combining vision and language models for VQA, or different encoder/decoder pairs for speech translation). The LEMUR dataset is being continually expanded, and with it, the capability of LLMs to exploit a richer set of building blocks will grow. We envision an interactive AutoML assistant that can propose full training-ready models, reason about their expected performance, and even adjust them based on training feedback – moving toward a new generation of AI-driven model development.

In conclusion, NN-Caption demonstrates a promising harmony between large language models and neural architecture search. By using LLMs’ generative and reasoning abilities, we can explore the design space of neural networks in a way that complements traditional NAS and human intuition. Our work contributes concrete artefacts (code for dozens of captioning models) and empirical insights to this emerging intersection of LLMs and NAS, and we hope it encourages further research on leveraging LLMs to advance automated machine learning.