1. Introduction

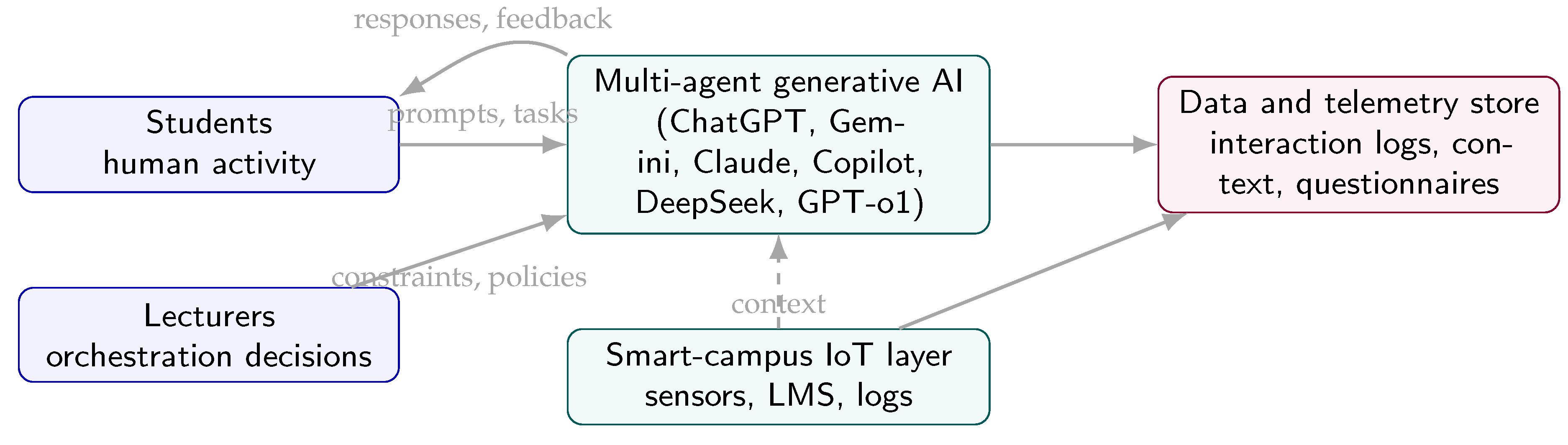

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude) and ubiquitous Internet of Things (IoT) infrastructures are rapidly transforming higher education into an agent-mediated ecosystem [

1,

2,

3,

4]. While early deployments primarily targeted individual cognitive performance or administrative efficiency, the Industry 5.0 paradigm calls for human-centred, sustainable and resilient educational models in which technology not only instructs but also

cares for learners [

5,

6]. In this view, AI systems should help maintain cognitive health, emotional balance and ethical awareness over time, especially in high-pressure academic environments [

7,

8]. We use the term

Nested Learning to describe such environments: digital ecosystems that envelop students in layered support structures and treat errors not as failings but as opportunities for adaptive scaffolding [

9,

10].

In this article, Nested Learning is introduced as a new conceptual and design proposal, rather than as an already validated theory. We use the term to denote learning environments in which learners are surrounded by nested envelopes of support—human, artificial and contextual—that jointly modulate pacing, representation and difficulty over time. Nested Learning is thus not a generic label for any AI-enhanced course, but a specific configuration that: (i) integrates generative AI agents, neuroeducational protocols and smart-campus data in a unified orchestration layer; (ii) foregrounds cognitive safety, self-regulated learning and a Pedagogy of Hope as explicit sustainability goals; and (iii) treats learner trajectories as dynamical processes to be guided, rather than as static outcomes to be measured. The present study offers an initial operationalisation and exploratory empirical illustration of this proposal; future work will be needed to test and refine its boundaries across contexts.

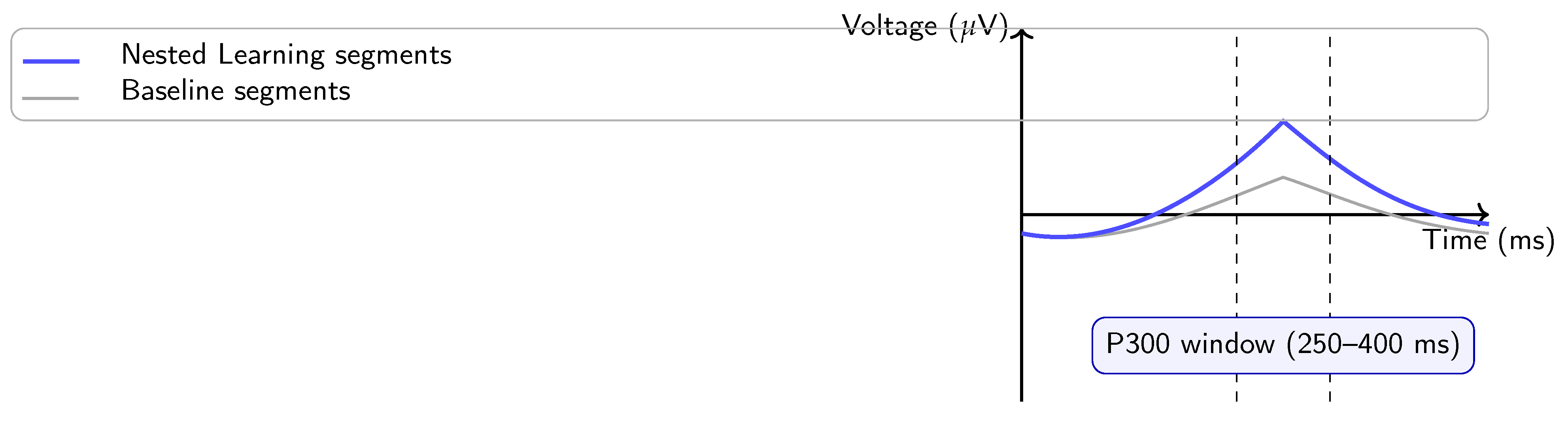

Nested Learning is conceived as a neuro-adaptive ecosystem that integrates generative AI agents, campus IoT networks and neuroeducational protocols into a unified orchestration layer. At its core, the learner’s neurocognitive state (e.g., attention, cognitive load, affect) is continuously sensed through mobile electroencephalography (EEG) and interaction traces, and then coupled with the external instructional context in real time [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In this work, the P300 component is used as a key attentional marker, embedded within dedicated neuroeducational protocols (PRONIN and SIEN) that structure sessions into micro-events and map instructional phases to neurophysiological windows [

9]. This coupling enables the ecosystem to modulate pacing, representation and task difficulty in response to measurable changes in students’ cognitive states.

In parallel, multimodal learning analytics and deep learning have broadened the range of signals available to educators, from keystroke and clickstream data to affective cues and biosignals [

15,

16,

17]. Recent reviews on AI in education and intelligent tutoring emphasise substantial progress in automated support and personalisation, but also highlight the lack of integrative frameworks that connect multimodal sensing, adaptive policies and ethical governance in a single model [

10,

18,

19]. Most current applications either (i) use generative AI as a standalone tool for content generation or feedback, or (ii) treat neuroimaging within tightly controlled laboratory settings that are difficult to scale to authentic classrooms [

2,

3]. There remains a gap between these strands: we lack conceptual and technical frameworks that

jointly orchestrate generative AI agents, multimodal deep learning and neurophysiological sensing in ways that are transparent, reproducible and aligned with educational values such as autonomy, equity and sustainability [

6,

20].

Alongside these optimistic narratives, a substantial body of critical scholarship warns that AI in education can intensify datafication, commercialisation and automation of pedagogical decisions, with problematic implications for equity, professional autonomy and student agency [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Our work is explicitly situated at this intersection: Nested Learning is proposed not as a neutral technical fix, but as a design framework that must be evaluated against these concerns, particularly in relation to cognitive safety, data governance and sustainable workloads for teachers and students.

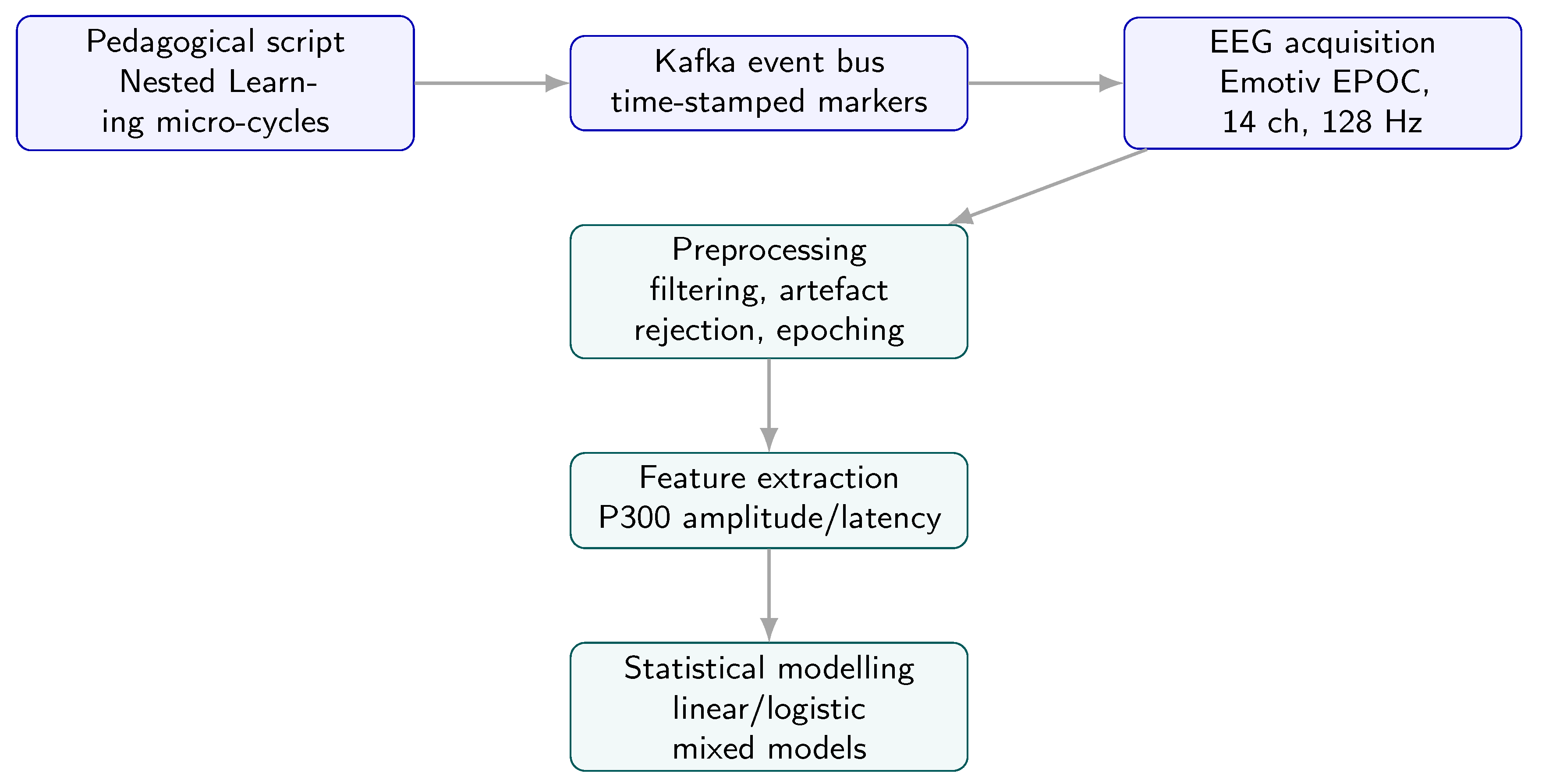

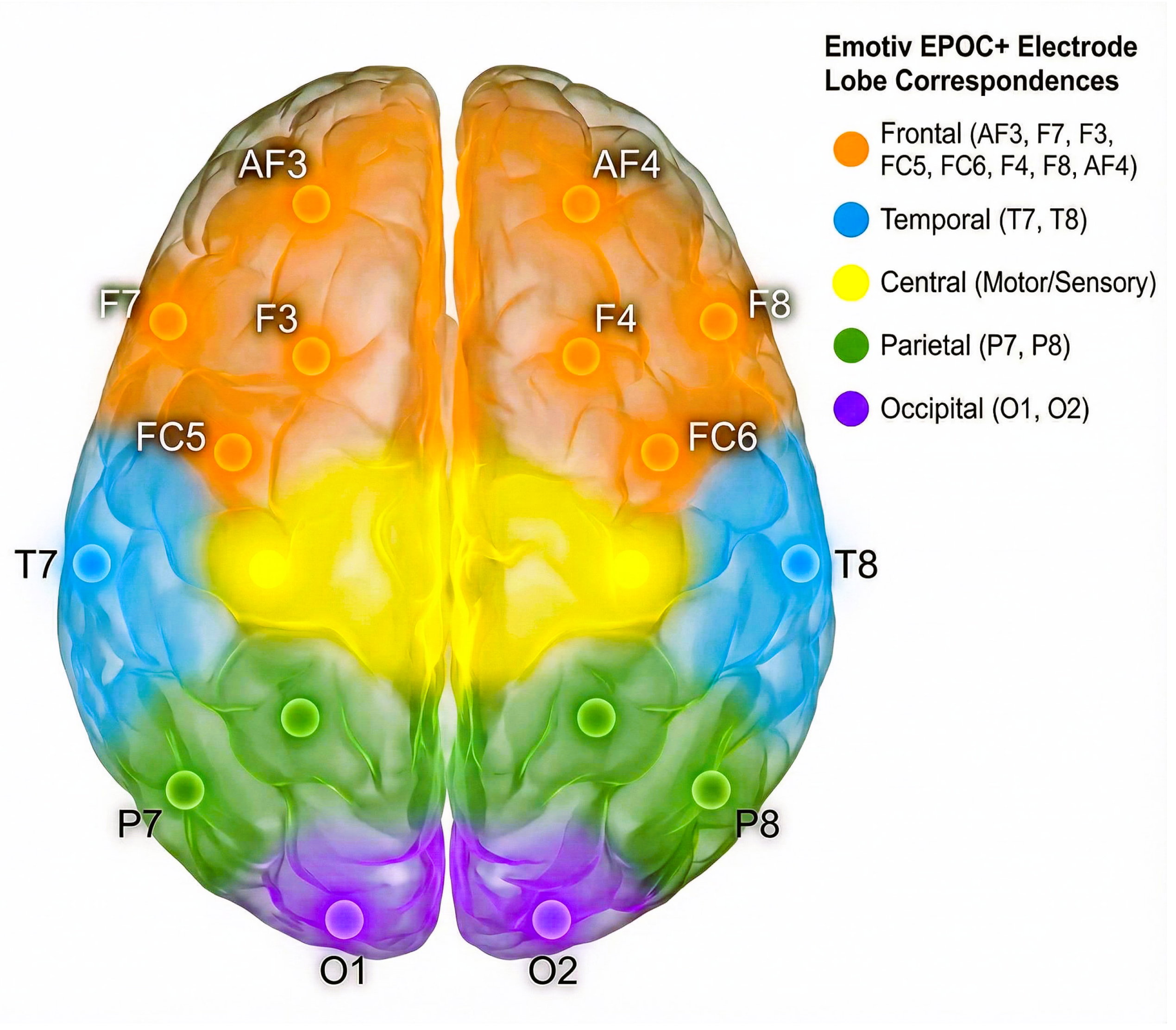

Study-design note (neuro–field integration). To address this gap, we adopt a two-phase mixed-methods design that calibrates the Nested Learning ecosystem in a laboratory setting and then evaluates it at scale in authentic courses [

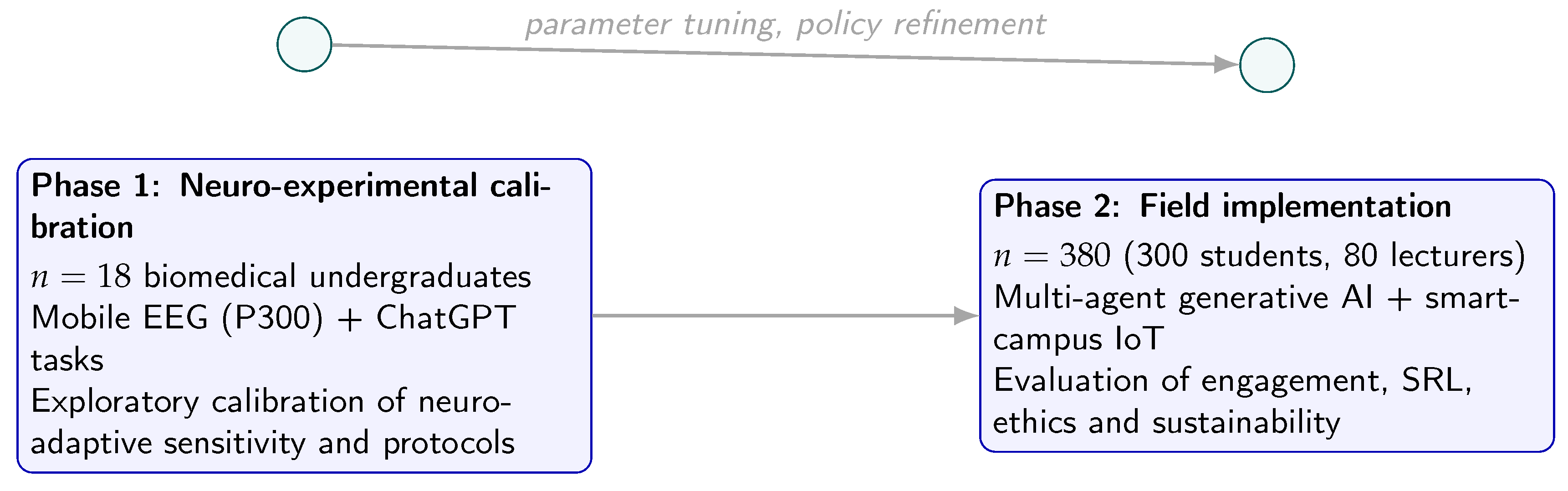

27]. As summarised in

Table 1, a first neuro-experimental phase with

biomedical undergraduates uses mobile EEG (Emotiv EPOC, 14 channels, 128 Hz) during problem-solving tasks mediated by ChatGPT to examine whether P300 dynamics and derived neuroeducational indices are sufficiently sensitive and stable under the proposed protocol to justify larger-scale studies [

11,

12]. This phase is explicitly conceived as an exploratory

calibration study rather than a fully powered validation of the neuro-adaptive system. A second field phase in a Madrid-based university involves

participants (300 students, 80 lecturers), embedding the ecosystem into regular courses with multiple generative AI platforms (ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Copilot, DeepSeek, GPT-o1) orchestrated through distributed-agent frameworks (JADE, PADE, LangChain) and connected to the campus IoT infrastructure. This combination allows us to study both the neurophysiological underpinnings of Nested Learning and its perceived impact on engagement, self-regulation, cognitive safety and ethical concerns in real-world contexts.

Figure 1 provides a temporal overview of the two phases.

Beyond the technical challenge, AI-mediated higher education raises a broader pedagogical question:

what forms of knowledge, agency and wellbeing should be valued when AI can already produce sophisticated outputs on demand? From a sustainability perspective, focusing solely on product quality (grades, performance metrics) is insufficient. Sustainable higher education requires attention to students’ capacity for self-regulated learning, their experience of cognitive safety and their sense of hope and meaning in the learning process [

7,

8,

20]. We therefore position Nested Learning within a “Pedagogy of Hope” perspective, in which AI and neuroadaptive technologies are used to expand, rather than erode, human agency—particularly for students who are at risk of disengagement, burnout or marginalisation [

9,

10,

28,

29].

In this framing, the role of generative AI agents extends beyond delivering feedback or solving tasks. Agents become mediators of

process visibility: they expose planning traces, testing strategies, evidence citations and neuro-adaptive adjustments in ways that students and teachers can inspect and critique [

2,

3,

6,

30]. The IoT layer enriches this picture by bringing contextual signals from physical spaces (e.g., classroom occupancy, environmental conditions) into the decision loop, supporting more holistic understandings of when and why learners thrive or struggle [

31].

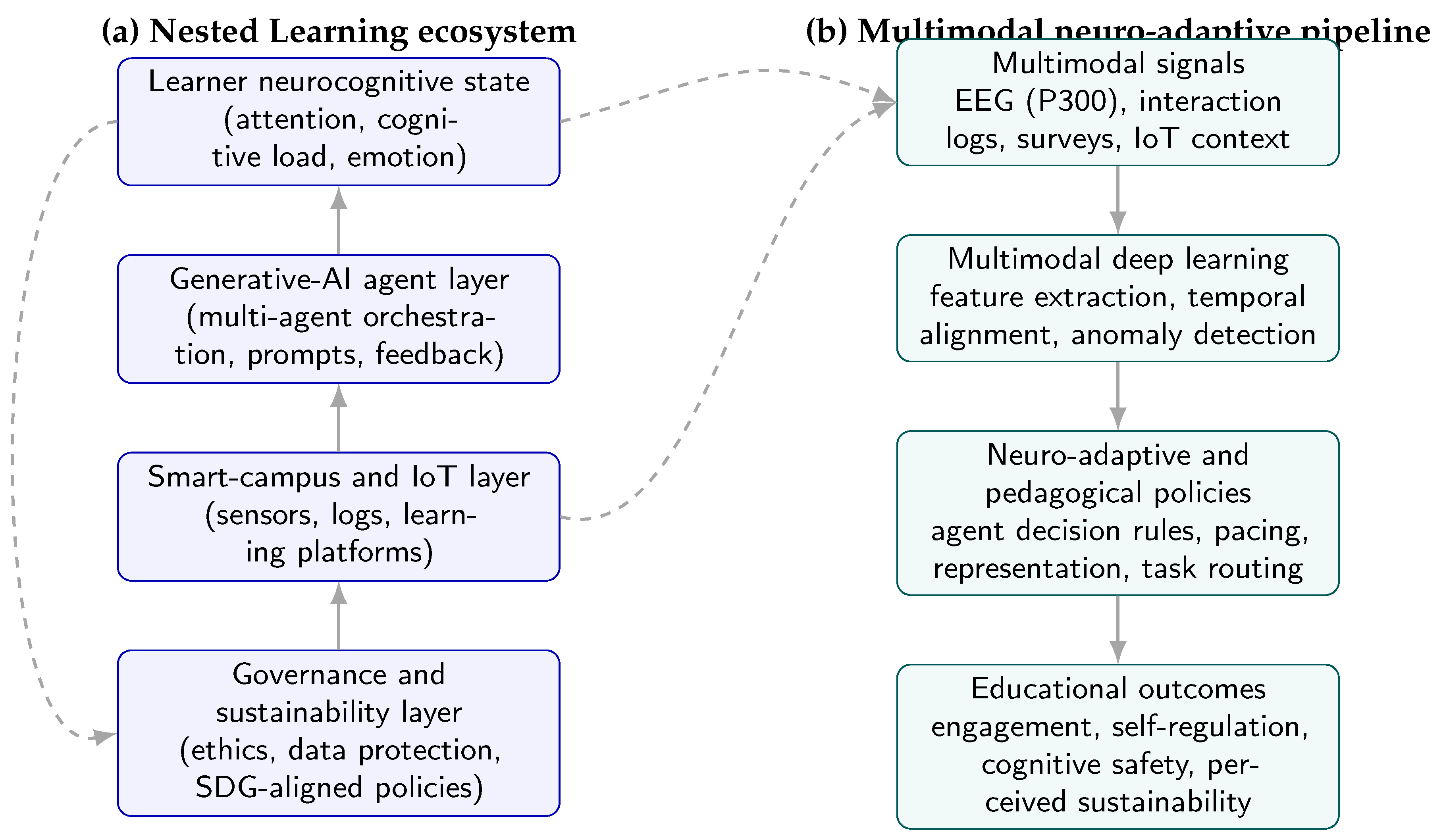

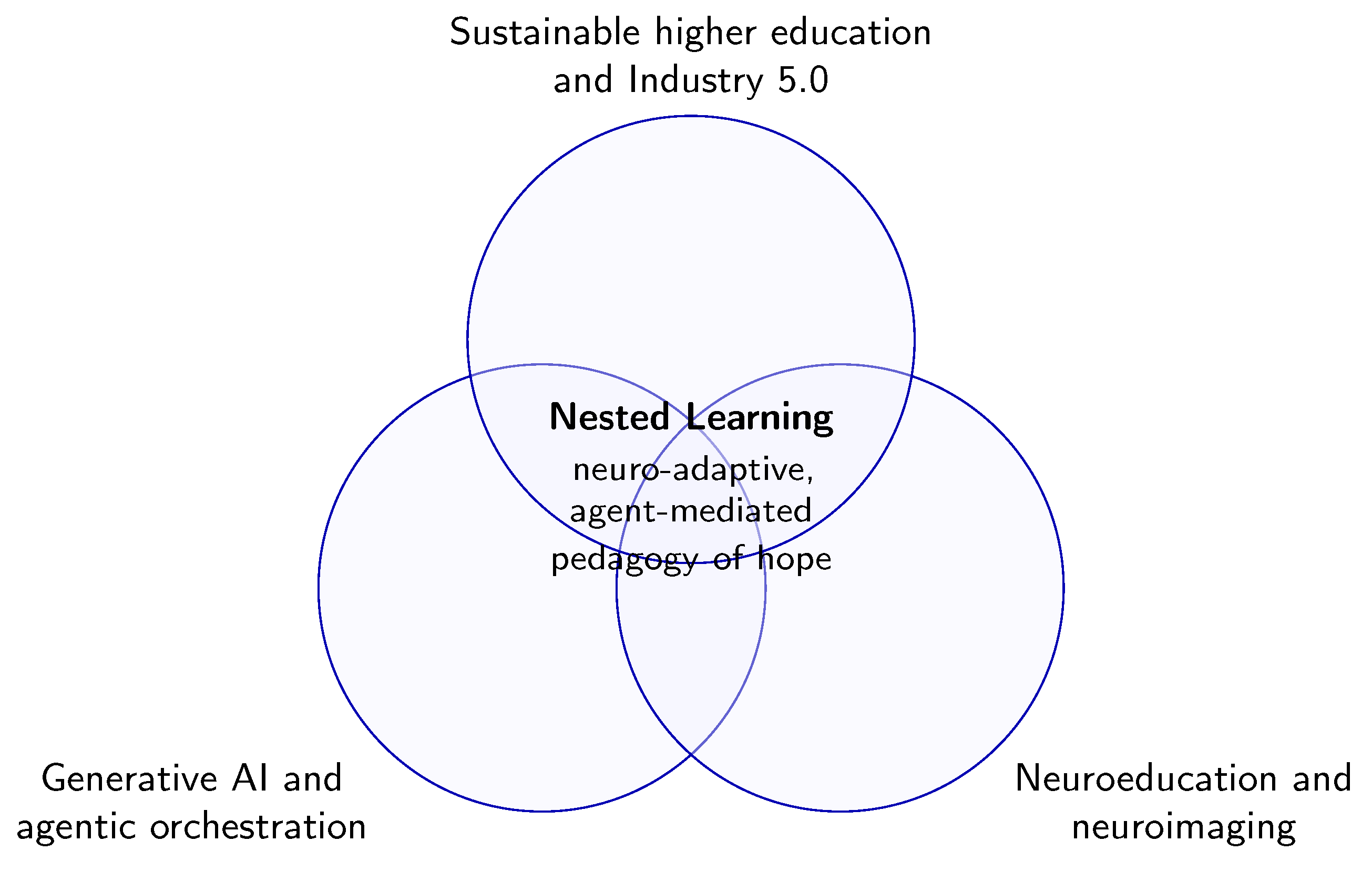

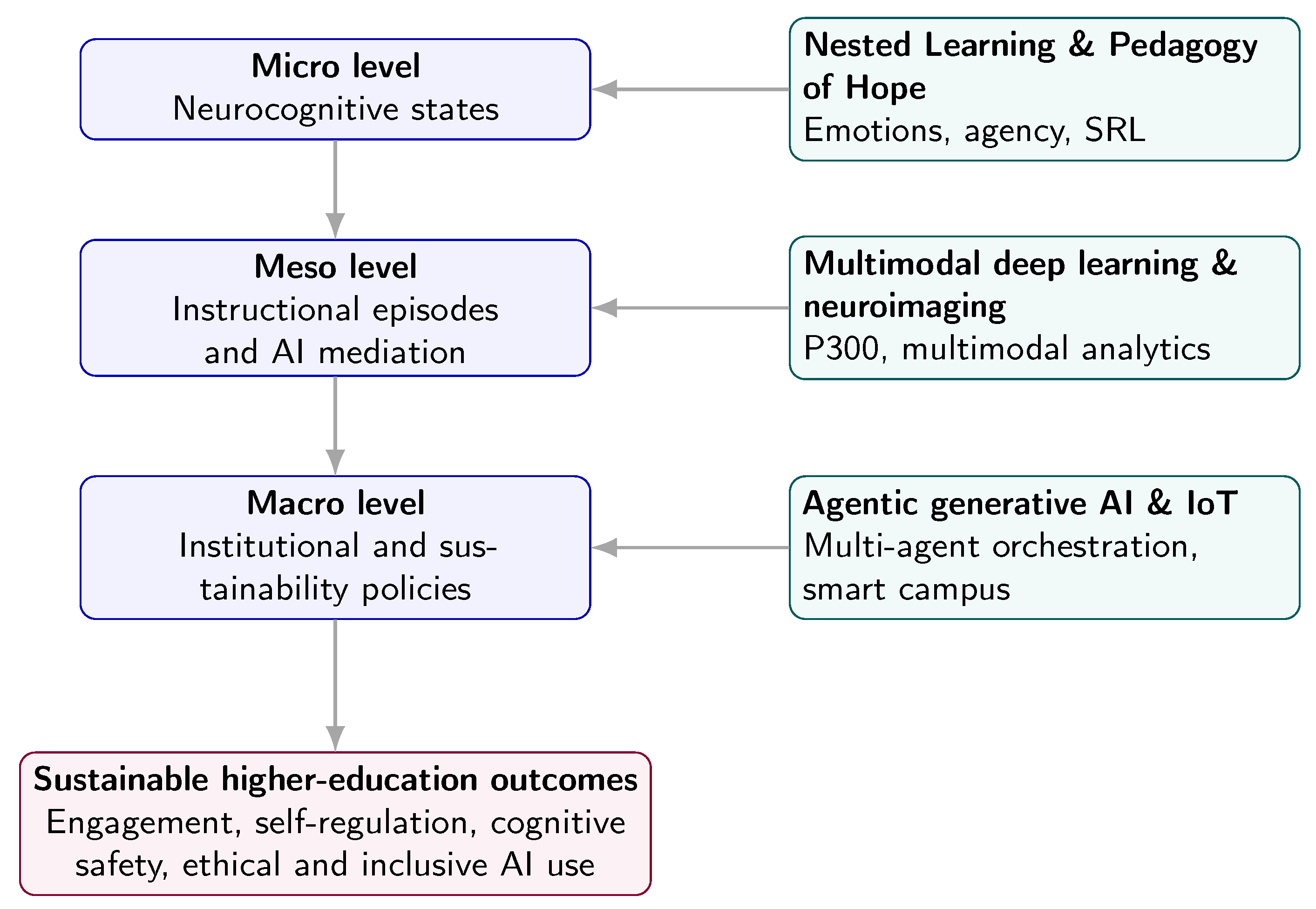

Figure 2 provides a high-level overview of this multi-layer ecosystem and its multimodal data pipeline, while

Figure 3 situates Nested Learning conceptually at the intersection of generative AI, neuroeducation and sustainable higher education.

To make the study design transparent,

Table 1 summarises the two phases and their main characteristics.

This study introduces Nested Learning as a neuro-adaptive, agent-mediated ecosystem for sustainable higher education. Our contribution is fourfold:

- (i)

Conceptually, we articulate Nested Learning as a multi-layer architecture that integrates generative AI, neuroeducation and IoT within a Pedagogy-of-Hope framework, positioning cognitive safety, resilience and autonomy as explicit sustainability goals [

5,

6,

9].

- (ii)

Methodologically, we propose a multimodal deep-learning pipeline that aligns EEG (P300) dynamics with instructional events and agent interventions, enabling neuro-adaptive policies that remain interpretable for educators [

11,

12,

13,

14].

- (iii)

Empirically, we provide preliminary findings from a two-phase mixed-methods design: a neuro-experimental calibration with

students and a field implementation with

participants, focusing on engagement, self-regulated learning, perceived clarity, adaptive support and ethical concerns [

8,

20,

27].

- (iv)

From a governance perspective, we discuss how privacy-by-design, data sovereignty and ethical stewardship are necessary to deploy Nested Learning ecosystems in ways that are compatible with sustainable higher education and the broader goals of Industry 5.0, while responding to critical concerns about datafication and automation in AI in education [

6,

21,

25,

30,

31].

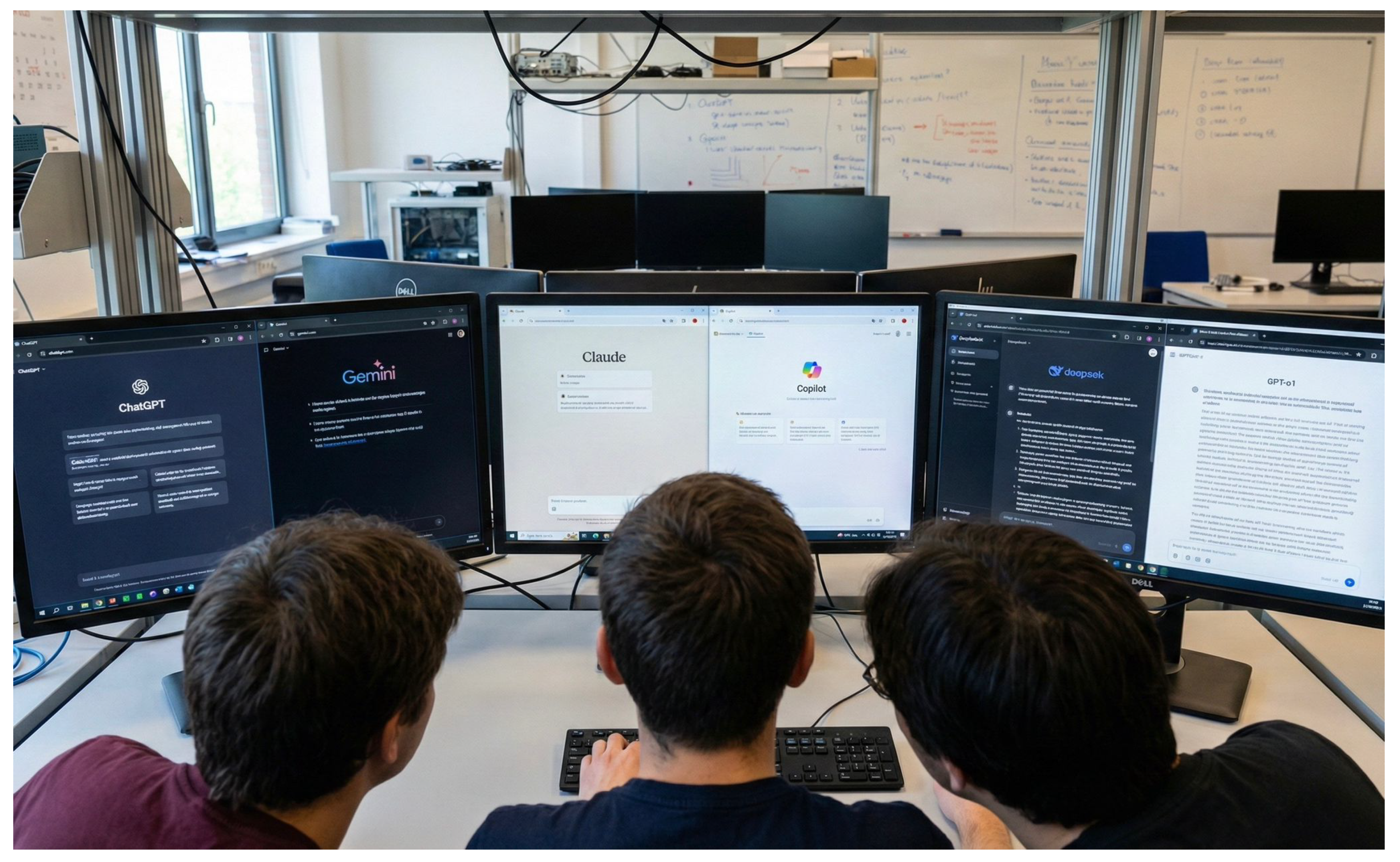

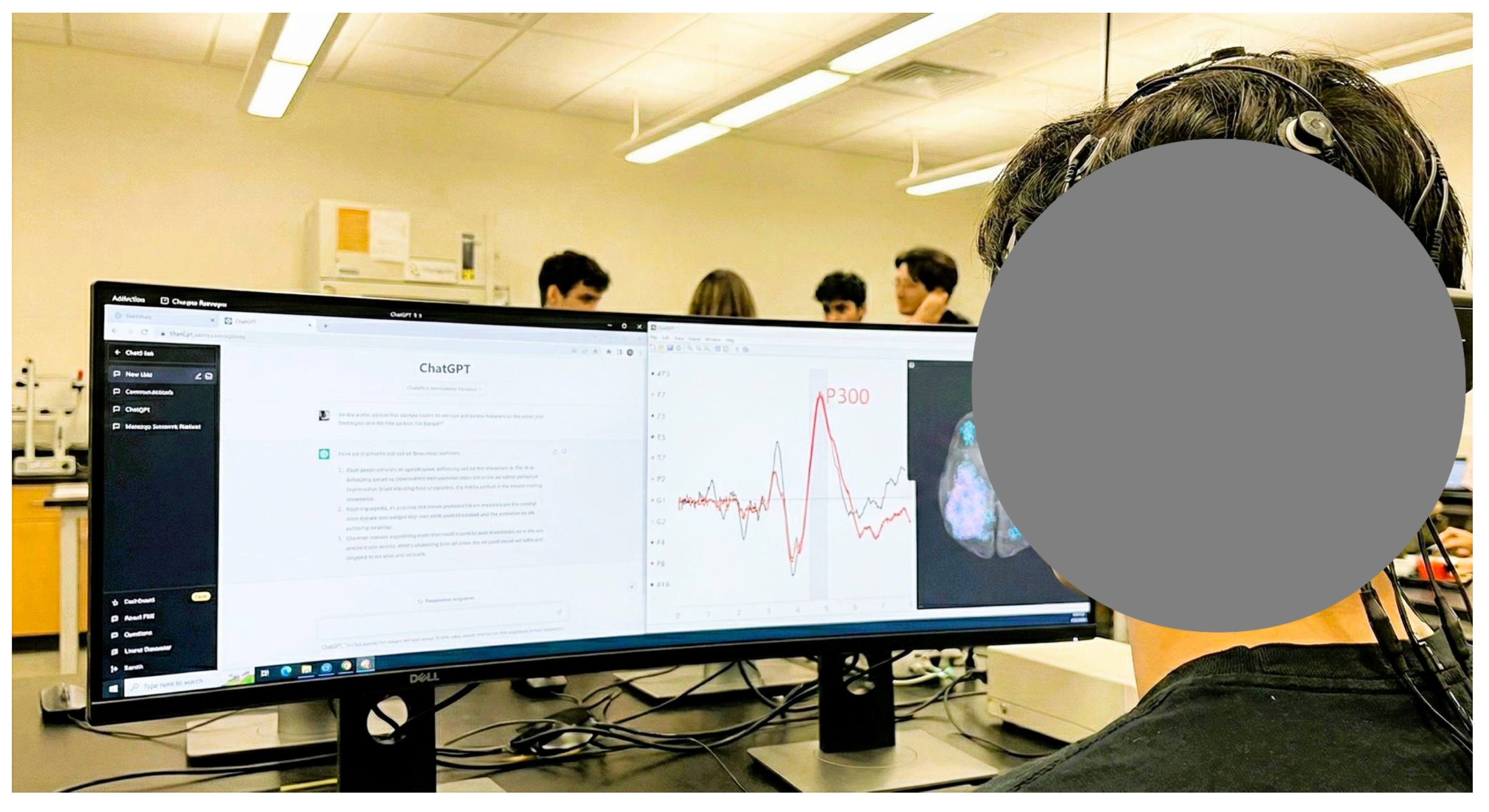

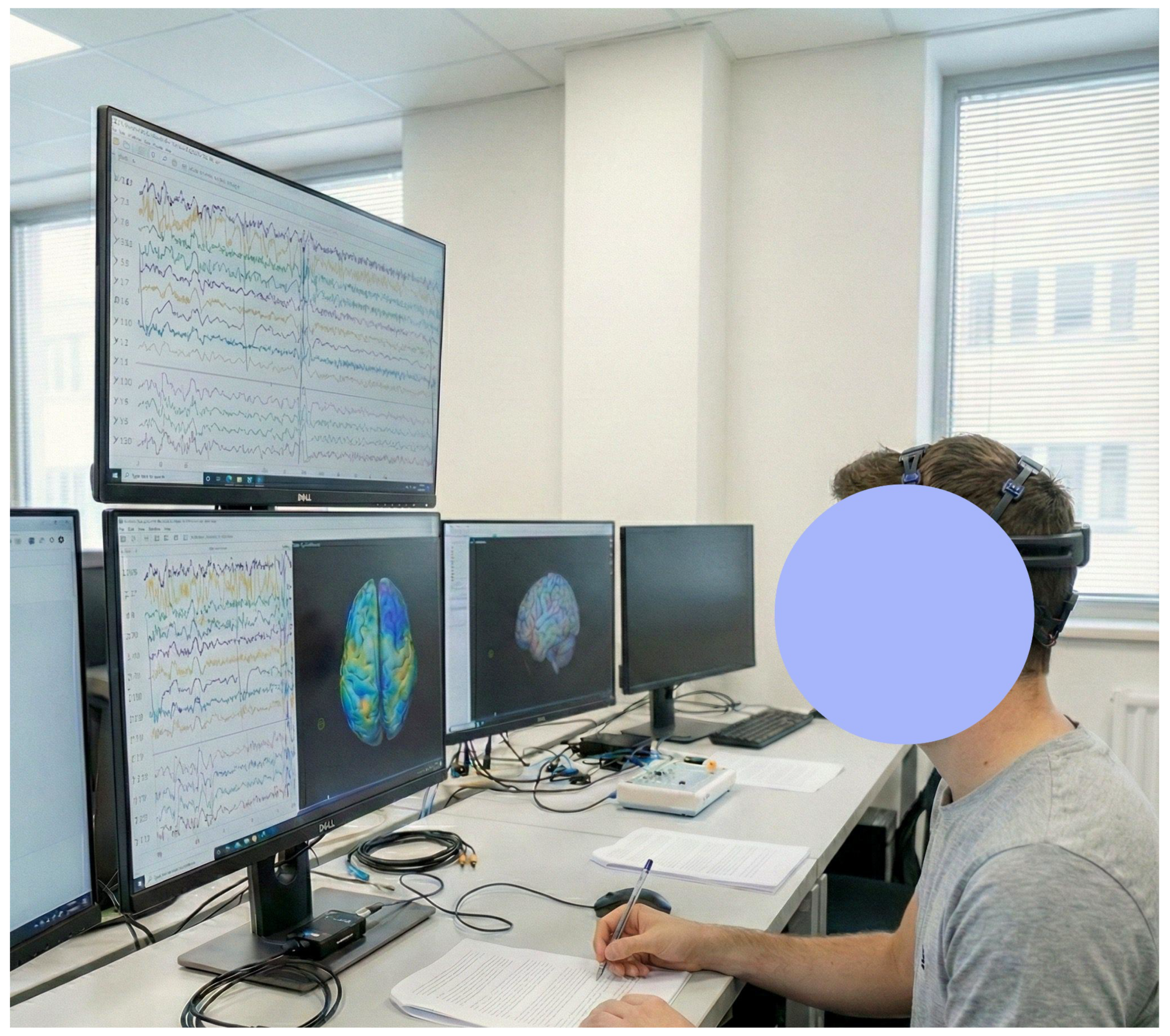

As illustrated in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the proposed Nested Learning ecosystem combines low-cost neuroimaging, real-time interaction with generative AI agents, and a multi-platform LLM workstation deployed in authentic higher-education settings.

4. Results

Before presenting the neuro-experimental findings,

Figure 10 summarises the Emotiv

electrode montage and its correspondence with the main cortical lobes used in Phase 1.

Phase 1 was designed as a small-sample neuro-experimental calibration, not as a fully powered validation of a neuroadaptive system, and Phase 2 is an ecological field study without random assignment or tight experimental control. The analyses therefore probe the plausibility and boundaries of the Nested Learning model rather than offering a definitive or exhaustive empirical demonstration.

4.1. Phase 1: Neuroimaging Processing and Attentional Coupling

The neuro-experimental phase suggests that the Nested Learning protocol can be monitored through low-cost mobile EEG while maintaining acceptable data quality and interpretable attentional markers in this specific sample and context. Across the 18 biomedical students, signal quality remained generally stable: after filtering and artefact handling, approximately 91.6% of epochs were retained as valid for analysis, enabling estimation of event-related potentials (ERPs) at the single-participant level.

Topographical inspection of the averaged ERPs revealed a pattern compatible with parietal P300 generators, with maximal amplitudes over centro-parietal sites and a gradual decrease towards frontal and occipital electrodes, consistent with the expected distribution for attention-related P300 components in educational tasks [

11,

13,

14]. Frequency-band analysis (delta, theta, alpha, beta) showed an initial increase in frontal theta and a modulation of parietal alpha during Nested Learning segments, compatible with phases of heightened cognitive control followed by consolidation and stabilisation of the task set.

Figure 11 provides a schematic summary of the ERP results, highlighting the contrast between baseline and Nested Learning segments.

Linear mixed-effects models with P300 amplitude as outcome and pedagogical-event descriptors as predictors (

Section 3.3) showed that higher event intensity and Nested Learning segments were associated with increased P300 amplitude, with statistically significant fixed effects and participant-level random intercepts. Logistic mixed models for the probability of high-amplitude P300 responses yielded similar patterns, supporting the assumptions in Equations (

8) and (

9): moments of carefully orchestrated challenge–support–reflection elicited clearer attentional signatures than baseline conditions in this sample.

Given the modest sample size and the feasibility-oriented nature of Phase 1, these results should be interpreted as preliminary evidence that the neuro-adaptive pipeline can track, in real time, key aspects of attentional coupling between the pedagogical flow and students’ cortical responses. They provide an empirical anchor for the engagement-related component

in the dynamical model of Equation (

3), but do not exhaustively validate the full state-space formulation.

4.2. Phase 2: Impact on Engagement and Self-Regulation

4.2.1. Descriptive Patterns, Reliability and Subgroup Analysis

In the large-scale field implementation (

), questionnaire responses indicated generally positive perceptions across all four dimensions and the two outcome scales.

Table 3 summarises the descriptive statistics, distributional properties and reliability indices for each construct.

As shown in

Table 3, all dimensions exhibited means well above the scale midpoint (3.0), ranging from 3.88 (Neuroadaptive Adjustments) to 4.25 (Climate of Hope). The indices of skewness were consistently negative (ranging from

to

), confirming a left-skewed distribution where the majority of participants reported high levels of perceived support and safety. Kurtosis values remained within the acceptable range (

) for normal theory-based estimation methods, supporting the use of parametric analyses. Reliability coefficients (

and

) exceeded 0.80 for all scales, demonstrating robust internal consistency [

27].

Regarding the subgroups of interest specified in the methodology, independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare Students () and Lecturers (). Results revealed a high degree of convergence in perceptions ( for NL, SAF and ENG), suggesting that the ecosystem was experienced similarly by both learners and educators. A statistically significant, albeit small, difference was observed in Interaction with Generative AI, where students reported slightly higher usage and perceived utility () compared to lecturers (; ). This disparity likely reflects the students’ more intensive hands-on use of the agents for task resolution, whereas lecturers operated primarily at the orchestration level. No significant differences were found based on degree programme (STEM vs. non-STEM) or course level.

Reflective prompts and metacognitive interventions were frequently triggered in segments where the orchestrator inferred high cognitive load or decreasing engagement, consistent with the behavioural logs. These descriptive patterns provide the empirical foundation for the correlational and regression analyses that follow.

4.2.2. Construct Validity: Factor Structure

To examine the construct validity of the instrument, the total sample () was randomly split into two independent subsamples ( for EFA; for CFA).

First, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on the first subsample using principal axis factoring with direct oblimin rotation, assuming correlations between dimensions. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.89 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (), supporting the factorability of the data. The analysis yielded four distinct factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, explaining 68.4% of the total variance. All items loaded significantly () on their respective theoretical dimensions (Nested Learning, Interaction with AI, Neuroadaptive Adjustments, and Cognitive Safety), with no substantial cross-loadings.

Second, a

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on the second subsample to verify the four-factor structure. The model specification allowed latent factors to correlate. As shown in

Table 4, the Global Fit Indices demonstrated an excellent fit to the data, meeting standard thresholds for adequacy.

The combination of EFA and CFA results confirms that the instrument possesses a robust four-dimensional structure consistent with the theoretical framework proposed in

Section 2, justifying the use of the four composite scores in subsequent analyses.

4.2.3. Correlations Between Nested Learning, AI Interaction and Outcomes

Pearson correlations among the five composite scales considered here (Nested Learning, Interaction with Generative AI, Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments, Engagement and Self-Regulation) were positive and moderate to strong.

Table 5 summarises the inter-scale correlation matrix.

Nested Learning showed the strongest associations with Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (

) and Engagement (

), while Interaction with Generative AI exhibited moderate correlations with the other scales (

r between 0.41 and 0.54). Engagement and Self-Regulation were strongly correlated (

), consistent with the view that sustained involvement and metacognitive control are tightly linked in Nested Learning contexts [

7,

20].

From the dynamical perspective of Equation (

3), these correlations are compatible with the interpretation that higher perceived Nested Learning and neuroadaptive adjustments are associated with higher levels of the outcome components

(engagement) and

(self-regulation). However, the cross-sectional nature of the questionnaire data prevents strong causal claims.

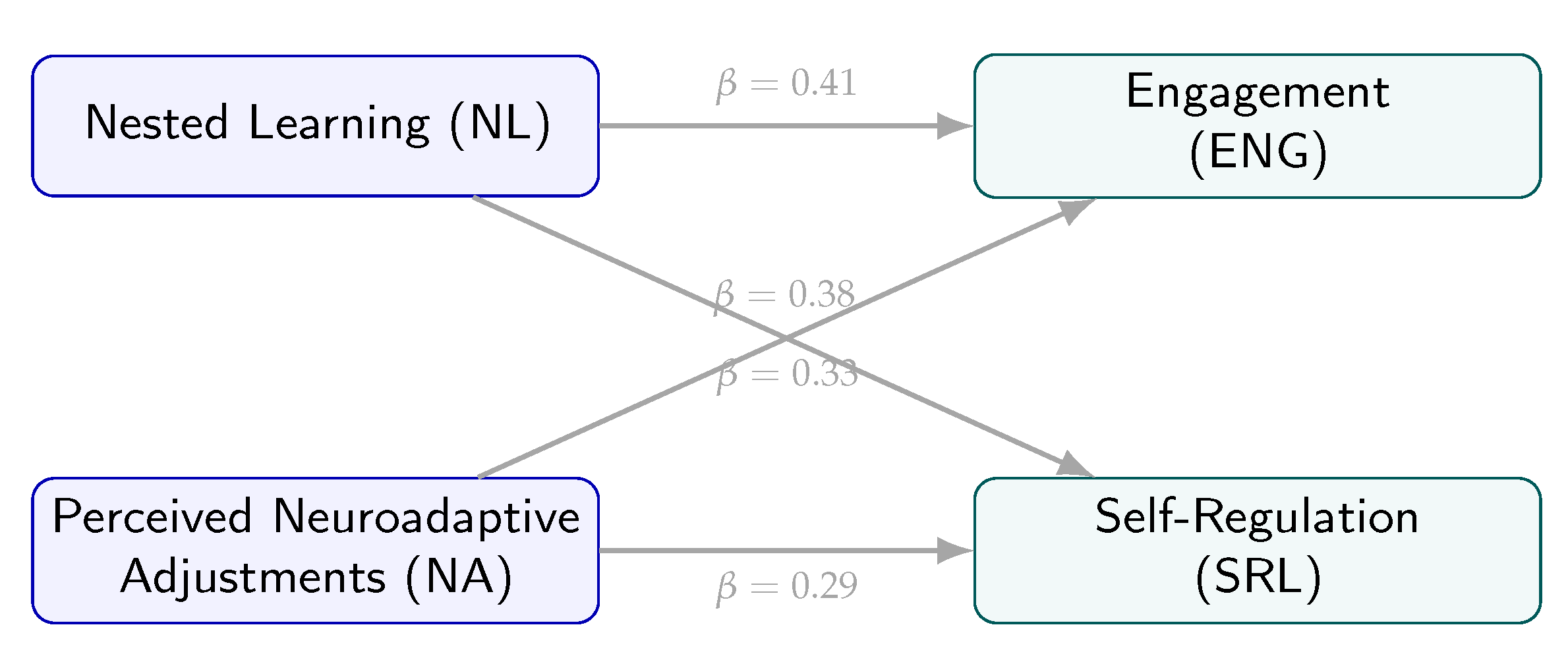

4.2.4. Predictive Models for Engagement and Self-Regulation

To examine the joint contribution of Nested Learning and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments, we fitted multiple linear regression models with Engagement and Self-Regulation as dependent variables.

Table 6 summarises the standardised coefficients,

t-values,

p-values and explained variance.

Nested Learning emerged as the strongest predictor in both models ( for Engagement; for Self-Regulation), with Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments also contributing substantially ( and , respectively). The models explain 39% and 34% of the variance in Engagement and Self-Regulation, respectively, which is considerable given the complex, multi-layer nature of the ecosystem, but should still be understood as indicative patterns rather than as definitive structural relations.

Figure 12 synthesises these relationships as a path diagram, emphasising that Nested Learning and neuroadaptive adjustments jointly drive engagement- and self-regulation-related components of the latent state vector

.

From the standpoint of the dynamical system in Equation (

3), these findings are consistent with (but do not prove) the interpretation that Nested Learning and neuroadaptive quality modulate the effective growth parameters

and

for engagement and self-regulation, increasing the probability that learners move towards desirable regions of the state space without destabilising the process.

4.3. Qualitative Results: Four Thematic Families of Nested Learning

The thematic analysis of the 12 open-ended questions (

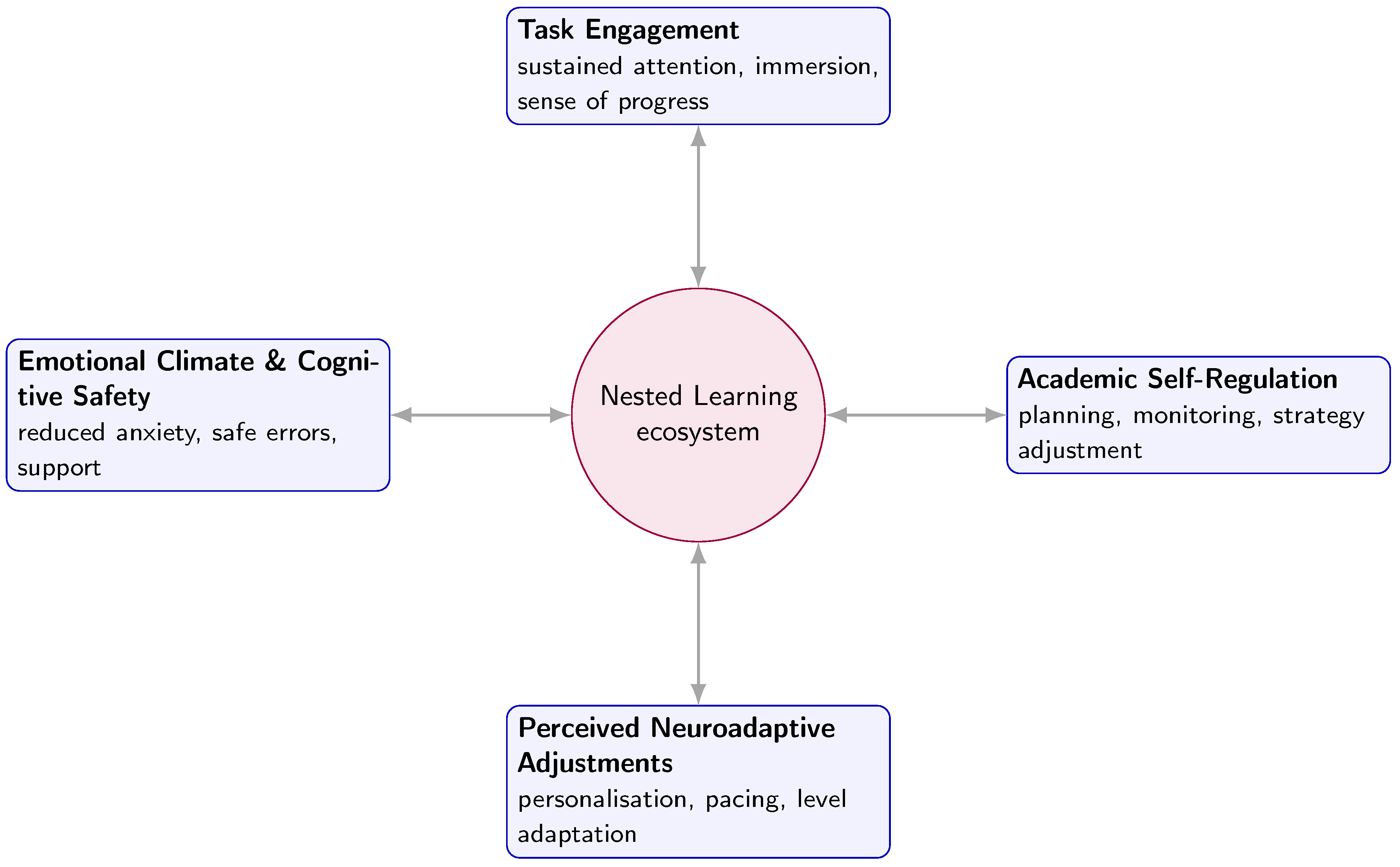

Section 3.5) yielded four main families that mirror the quantitative dimensions: (1) Task Engagement, (2) Academic Self-Regulation, (3) Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments and (4) Emotional Climate and Cognitive Safety. Each family contained several hundred coded excerpts, reflecting rich and nuanced student narratives.

Family 1: Task Engagement.

The first family (Task Engagement) comprised 512 coded excerpts, dominated by codes such as sustained attention, immersion, sense of progress, persistence and avoidance of dropout. Students frequently described uninterrupted focus, a feeling that time “passed quickly” and a sense of advancing through clearly structured stages. Many accounts emphasised that AI-mediated scaffolding, combined with the teacher’s presence, helped them remain engaged during complex segments rather than giving up prematurely. These narratives align with the strong quantitative correlations between Nested Learning, Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments and Engagement (

Table 5).

Family 2: Academic Self-Regulation.

The second family (Academic Self-Regulation) involved 389 coded excerpts with codes such as planning, monitoring learning, time management, strategy adjustment and autonomous help-seeking. Participants described being able to detect when they were “getting lost”, adjust their approach and use AI agents proactively for clarification instead of waiting passively for the lecturer. Immediate feedback and the possibility of iterating with generative AI allowed them to correct misunderstandings earlier in the process, which resonates with the predictive role of Nested Learning and neuroadaptive adjustments in the Self-Regulation model (

Table 6).

Family 3: Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments.

The third family (Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments) contained 301 excerpts and included codes such as personalisation, pacing adjustment, level adaptation, progressive guidance and perceived adaptation. A recurrent theme was the sensation that the system “adapted to me” rather than enforcing a fixed script. Students noted that, when they were stuck, the AI changed the type of example or explanation, enabling progress without feeling overwhelmed. Qualitative co-occurrence patterns between personalisation codes and references to feeling supported mirror the statistical contribution of neuroadaptive adjustments in predicting Engagement and Self-Regulation ( and ).

Family 4: Emotional Climate and Cognitive Safety.

The fourth family (Emotional Climate and Cognitive Safety) included 224 excerpts and was characterised by codes such as reduced anxiety, sense of support, confidence to make mistakes and renewed motivation. Students reported feeling emotionally safe, able to experiment and fail without fear of judgement, and consistently accompanied by some form of support (human and/or AI). These narratives align with the role of the cognitive-safety component

in the dynamical model and with the ethical and governance principles in

Section 3.7: Nested Learning is experienced not only as a cognitive scaffold but as an affective and ethical envelope.

Cross-Family Synthesis.

Across the four families, a convergent pattern emerged:

Engagement arises from the clarity of the process and the immersive structure of Nested Learning;

Self-regulation is strengthened by immediate feedback and adaptive structure;

Neuroadaptive adjustments are perceived as genuine personalisation rather than generic automation;

A safe emotional climate acts as a key mediator of attentional stability and persistence.

Figure 13 summarises these relationships as a qualitative map around the Nested Learning ecosystem.

This convergence between qualitative themes, questionnaire scores and neuroeducational markers supports the interpretation of Nested Learning as a neuro-adaptive, agent-mediated cycle that shapes the trajectory of the multidimensional learner state over time, while acknowledging that these inferences are based on observational data.

4.4. Technical Performance Versus Ethical Constraints

A comparative analysis of the six generative-AI platforms (ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Copilot, DeepSeek and GPT-o1) within the multi-agent station revealed differentiated profiles in terms of responsiveness, controllability and perceived transparency. Some agents excelled in rapid content generation and code completion, while others were preferred for their explanatory style or perceived alignment with ethical guidelines.

From a governance perspective, participants and instructors highlighted a tension between deep personalisation—enabled by fine-grained tracking of learner states and interactions—and concerns about privacy, over-surveillance and potential misuse of neurocognitive and behavioural data. These concerns echo the ethical constraints discussed in

Section 3.7 and frame the practical challenge of implementing the policy

within strict boundaries of data minimisation, transparency and cognitive sovereignty [

6,

32].

Phase 1 suggests that Nested Learning micro-events can be tracked through robust P300 markers using affordable EEG; Phase 2 shows that Nested Learning and neuroadaptive adjustments are strongly associated with engagement and self-regulation, both quantitatively and qualitatively; and the technical–ethical analysis underscores that sustaining such an ecosystem in higher education requires careful balancing of technical performance and protection of learners’ rights.

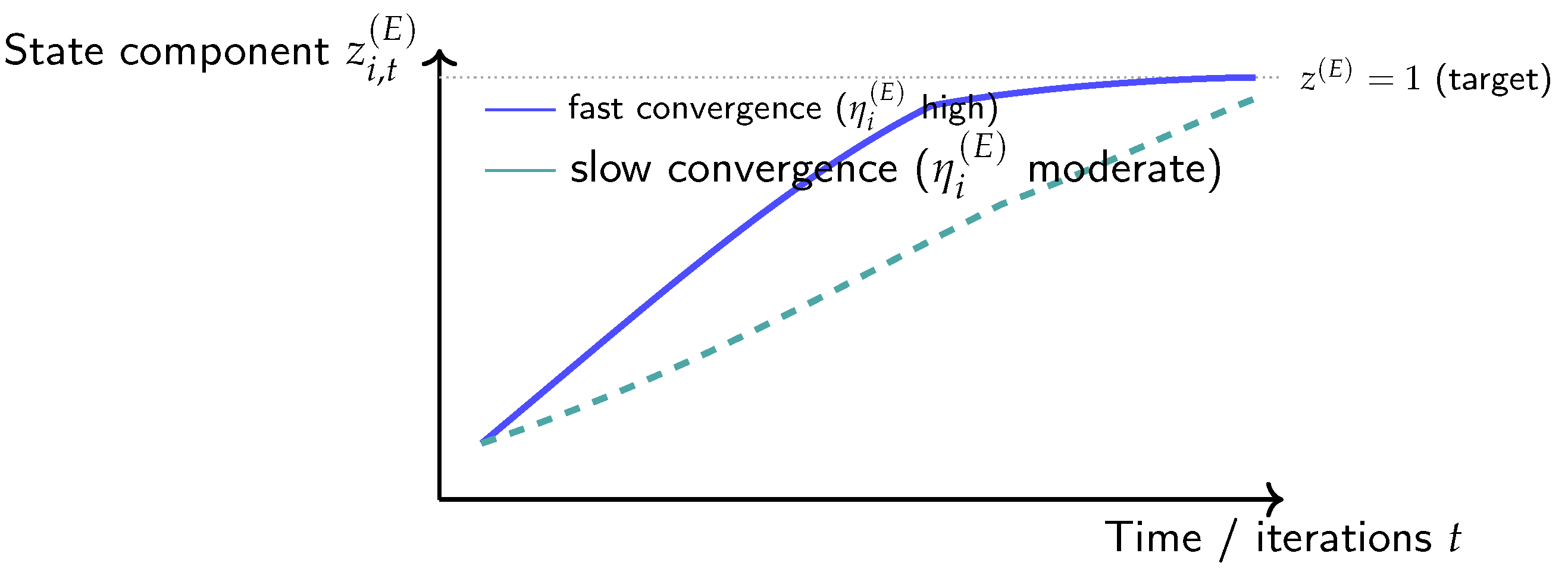

4.5. Empirical Convergence Patterns in the Latent Learner State

Section 2.5 formalised the Nested Learning ecosystem as a discrete-time dynamical system in which each learner is represented by a latent state vector. For the purposes of this section, we focus on the four components most directly informed by questionnaire and qualitative data,

encoding, respectively, engagement, self-regulation, cognitive safety and hope-related climate, while the performance component is treated separately. Component-wise updates were described by Equation (

3),

where

summarises agent actions and neuroadaptive adjustments,

denotes contextual variables (e.g., classroom, workload, time of semester),

is an individual learning-speed parameter and

captures idiosyncratic variability.

Empirically, we approximate

and

from the questionnaire scales for Engagement and Self-Regulation, rescaled to

, while

and

are informed by items on perceived cognitive safety and hope-related climate. The predictors in

Table 6—Nested Learning (NL) and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA)—can be interpreted as coarse-grained proxies of the control term

, since they aggregate perceived clarity of structure, adaptivity and contextual sensitivity of the ecosystem.

Under this mapping, the regression results imply that, for a large majority of learners, the expected increment

is positive whenever NL and NA are above minimal levels. Descriptively, more than 80% of participants reported increases in perceived engagement and learning outcomes after exposure to the ecosystem, with particularly high percentages for commitment and self-regulation (self-report comparisons between “before” and “after” items). In the dynamical formulation, this pattern corresponds to

for most learners and components

, together with a progressive reduction of the gap

.

Phase 1 provides a complementary view for the attentional component of the state. The P300 dynamics and frequency-band patterns described in

Section 4.1 show that, over the course of the neuroexperimental session, neuroeducational markers such as attention, commitment and interest stabilise in an “optimal” range (e.g., high attention and interest, low cognitive stress). This can be read as empirical evidence that the attentional component

approaches a high but sub-maximal equilibrium, compatible with logistic-type updates: early micro-events produce larger increments

, while later events yield smaller gains as the state approaches the ceiling.

Figure 14 depicts this behaviour schematically for two learners with different effective learning-speed parameters

, illustrating how the same Nested Learning policy can yield fast and slow but ultimately convergent trajectories in the engagement dimension.

In summary, although the field phase uses cross-sectional questionnaires rather than repeated measurements of across tasks, the combination of (i) robust positive associations between Nested Learning, neuroadaptive adjustments, engagement and self-regulation; (ii) high proportions of learners reporting perceived improvements; and (iii) stabilised neuroeducational markers in Phase 1, is consistent with the view that the ecosystem induces positive increments that gradually shrink as learners approach desirable regions of the state space. This consistency should be understood as model-supporting rather than as a formal convergence proof.

4.6. From Local Increments to Sustainable Trajectories

The dynamical framing also clarifies the sustainability implications of Nested Learning. At each step, the policy

selects agent actions and neuroadaptive adjustments that are expected to produce increments

in directions aligned with the pedagogical goals of the ecosystem: increased engagement (

), stronger self-regulation (

), higher cognitive safety (

) and a more hopeful, resilient outlook (

). Phase 1 suggests that this can be done without pushing the system into pathological regimes of over-arousal or stress, as indicated by the balanced profile of EEG bands and neuroeducational markers described in

Section 4.1. Phase 2 demonstrates that the same policy is associated with high levels of perceived clarity, adaptivity and emotional safety.

Within this perspective, sustainability can be interpreted as the existence of regions of the state space where:

- (a)

the expected increments are small but non-negative for desirable components (no rapid decay of engagement or self-regulation);

- (b)

fluctuations remain bounded, avoiding oscillatory or unstable trajectories;

- (c)

ethical and governance constraints on data usage and cognitive sovereignty are enforced at the policy level, constraining the admissible control signals .

The empirical configuration observed in this study—high engagement and self-regulation, low cognitive stress, strong perceptions of personalisation and safety, and explicit concerns about privacy that feed back into governance design—is compatible with such a “sustainable region”. In that region, the nested ecosystem acts as a regulator that gently pushes trajectories back towards pedagogically desirable zones when disturbances (e.g., overload, anxiety, loss of motivation) displace learners from them, rather than as an engine that maximises short-term performance at the cost of long-term wellbeing.

This interpretation reinforces the central claim of the paper: Nested Learning is not only a technical architecture but a policy-level design for shaping the temporal evolution of learner states in ways that are mathematically tractable, empirically grounded and aligned with the human-centric aspirations of Industry 5.0 and a Pedagogy of Hope.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the empirical results through the lens of the Nested Learning framework and the underlying dynamical model, and discusses their implications for sustainable higher education. In line with the mixed-methods and feasibility-oriented nature of the study, the aim is not to claim definitive validation of the framework, but to examine how far the empirical patterns are compatible with the proposed conceptual and mathematical structure, and where important uncertainties remain. We organise the discussion around four axes: (i) the viability of low-cost neuro-adaptive monitoring, (ii) the role of Nested Learning and neuroadaptive adjustments in relation to engagement and self-regulation, (iii) the contribution of the dynamical perspective to the design of sustainable AI-mediated ecosystems, and (iv) the ethical and governance constraints that bound acceptable trajectories of learner states.

5.1. Neuro-Adaptive Viability in Authentic Educational Contexts

One of the central questions of this study was whether a neuro-adaptive ecosystem can be instantiated with affordable hardware and realistic constraints, without reverting to highly controlled, laboratory-only scenarios. Within the limits of a small, homogeneous sample, the Phase 1 results suggest that this is feasible. Using a low-cost, 14-channel mobile EEG device, we obtained reasonably stable recordings with more than 90% valid epochs after artefact handling, and clear P300 signatures that differentiated Nested Learning segments from baseline activity in this specific group.

The topographical and temporal patterns of the P300 component are compatible with classical accounts of attention and context updating in educational tasks [

11,

13,

14]. Importantly, these signatures were obtained in tasks mediated by ChatGPT and embedded in a pedagogical micro-cycle of challenge, scaffolding and reflection, rather than in artificially simplified stimuli paradigms. This supports, at least at a feasibility level, the idea that neuroeducational markers can be harnessed in

ecologically valid conditions, aligning with the broader aims of neuroeducation to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and classroom practice [

7,

10].

From the standpoint of the measurement function

in Equation (

7), P300 amplitude and related neuroeducational indices (attention, commitment, interest, stress) act as partial readouts of the engagement component

. The observed stabilisation of these markers in an optimal range suggests that, in this context, the Nested Learning protocol can steer the system away from both under-stimulation (boredom) and over-stimulation (overload), a prerequisite for sustainable cognitive performance. At the same time, the modest sample size, the lack of a control group with alternative pedagogical scripts, and possible novelty effects mean that these findings should be treated as preliminary and in need of replication.

5.2. Nested Learning, Engagement and Self-Regulation

The Phase 2 results show that Nested Learning and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments are strongly associated with Engagement and Self-Regulation. Correlations in

Table 5 and regression paths in

Figure 12 indicate that learners who perceive higher levels of nested support (multi-layered human–AI scaffolding) and adaptation (pacing, representation, difficulty) tend to report higher engagement and stronger self-regulatory practices. This pattern is reinforced qualitatively by the four thematic families (

Figure 13), where narratives emphasise immersion, sense of progress, planning and strategic help-seeking.

These findings resonate with previous work on self-regulated learning and affect in education, which highlights the importance of structured support, timely feedback and emotionally safe environments for sustaining engagement and developing metacognitive competences [

7,

8,

20]. The present study adds an additional layer by situating these processes within a distributed socio-technical network: the nested envelope of support involves not only teachers and peers, but also generative AI agents and IoT-informed orchestration.

In this sense, Nested Learning can be seen as an operationalisation of a

Pedagogy of Hope [

28] for AI-rich contexts. Instead of using AI primarily to accelerate traditional, grade-centric metrics, the ecosystem foregrounds process visibility, cognitive safety and reflexive dialogue, aiming to empower students who might otherwise disengage or experience burnout. The positive associations between Nested Learning, neuroadaptive adjustments and self-regulation suggest that generative AI, when deliberately framed and governed, can support rather than erode learner agency. Nevertheless, the observational nature of the data, the lack of a comparison condition without Nested Learning, and potential confounders (e.g., teacher enthusiasm, novelty of AI use, local institutional culture) mean that alternative explanations cannot be ruled out.

5.3. Dynamical Interpretation: From Correlations to Trajectories

The dynamical model in

Section 2.5 conceptualised the ecosystem as a discrete-time process in which each learner is described by a state vector

, with components such as performance, engagement, self-regulation and cognitive safety. The empirical results do not provide dense time series for each individual, but they do allow us to reason about average increments

and the qualitative shape of trajectories under a given policy

.

The combination of (i) positive associations between Nested Learning/neuroadaptation and Engagement/Self-Regulation; (ii) qualitative evidence of perceived improvement in planning, monitoring and emotional climate; and (iii) stabilised attentional markers in Phase 1, is

consistent with a regime in which

and

are, on average, positive but decreasing as learners approach higher levels. This matches the structure of Equation (

3), where increments scale with the gap-to-target

and with a control term

that encodes the quality and alignment of agent actions.

In contrast to purely predictive models such as classical Knowledge Tracing, our framing emphasises policy design rather than state estimation alone. The question is not only “What is the probability of a correct answer next time?” but also “What sequence of actions should the ecosystem take to nudge the learner towards a sustainable region of the state space?”. In this sense, the empirical results support the conceptual shift towards viewing feedback, pacing and representational choices as control signals in a dynamical system, with interpretable parameters and stability properties.

At the same time, the current data do not allow for formal estimation of individual parameters

or rigorous stability analysis. The dynamical equations should therefore be read as a generative model that organises hypotheses and informs design, rather than as a structure fully identified from data. Future longitudinal and experimental work will be required to test whether the trajectories of

under Nested Learning indeed exhibit the convergence patterns suggested by

Figure 12 and

Figure 14.

5.4. Design Principles for Sustainable Nested Learning Ecosystems

The synthesis of neuroexperimental, behavioural, self-report and qualitative evidence suggests a set of provisional design principles for Nested Learning ecosystems in higher education:

- (a)

Layered orchestration rather than single-tool usage. The most positive experiences arise when learners perceive a coherent envelope of support (teacher, AI agents, peers, physical context), rather than isolated interactions with a single chatbot or tool. This aligns with the “nested” metaphor and the multi-layer architecture in

Figure 2.

- (b)

Process visibility and trace-based assessment. Making planning traces, testing strategies, evidence citations and neuroadaptive adjustments visible helps learners understand how they are progressing, not just whether outputs are correct. This supports self-regulation and reduces dependence on opaque AI decisions.

- (c)

Neuroadaptive moderation, not maximisation. The neuroeducational results suggest that effective orchestration aims at stabilising attention and commitment in a mid-to-high range, avoiding both under-challenge and over-stimulation. This implies that the goal of the policy is not to maximise engagement at all costs, but to regulate it within a sustainable corridor.

- (d)

Hope-centred error culture. Qualitative data highlight that students value environments where errors are treated as natural and productive. Designing prompts, feedback and assessment formats that normalise uncertainty and iterative refinement is crucial for maintaining a hopeful stance towards learning, especially under the pressure of high-stakes evaluation.

- (e)

Human-in-the-loop governance. Finally, teachers and institutional actors must retain meaningful control over the ecosystem. Configuring agent roles, thresholds for neuroadaptive interventions, and data-retention policies cannot be delegated to AI alone; they require ongoing pedagogical and ethical deliberation [

6,

32].

These principles are not exhaustive and should be treated as context-sensitive heuristics rather than universal rules. Nonetheless, they illustrate how the mathematical and empirical layers of the study can translate into concrete design choices that universities may consider when deploying AI-rich infrastructures.

5.5. Ethical and Governance Implications

The study also foregrounds the tension between personalisation and privacy. On the one hand, fine-grained monitoring of engagement, affect and self-regulation is precisely what enables the ecosystem to deliver timely, adaptive support. On the other hand, students and lecturers expressed concerns about potential over-surveillance, data misuse and loss of cognitive sovereignty, especially when neuroimaging data are involved.

From the dynamical perspective, this tension can be framed as a constraint on admissible control signals . Not all theoretically effective interventions are ethically acceptable. For instance, an aggressive modulation strategy that pushes to very high levels of arousal might improve short-term performance but violate principles of cognitive safety and autonomy. Similarly, continuously tracking micro-fluctuations in attention might provide rich data for optimisation, but at the cost of an invasive experience that undermines trust.

Accordingly, any practical deployment of Nested Learning must embed privacy-by-design and data-minimisation principles at the architectural level [

6,

31]. This includes limiting the granularity and retention of neurocognitive data, giving learners meaningful control over what is collected and how it is used, and ensuring that high-level summaries are sufficient for pedagogical decisions. Transparent communication about these policies is essential for aligning perceived and actual governance. More broadly, institutional AI strategies and regulatory frameworks (e.g., GDPR, sector-specific guidelines) will shape what kinds of Nested Learning implementations are legally and socially acceptable.

5.6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Several limitations qualify the interpretation of our findings and point to avenues for future work.

First, the neuro-experimental phase involved a relatively small and homogeneous sample of biomedical students, and while the results are consistent with prior literature on P300 and attention, generalisation to other disciplines, age groups and cultural contexts must be done cautiously. Replications with larger and more diverse samples—including non-STEM programmes and different institutional profiles—are necessary to validate the robustness of neuro-adaptive markers in Nested Learning scenarios.

Second, the field implementation, although large (), relied on self-report measures and interaction logs collected at limited time points. We did not track individual state vectors across multiple discrete tasks in the same way as classical learning-analytics studies, nor did we include a control group exposed to an alternative (non-nested) AI-mediated design. Future research should combine longitudinal measurement of performance, engagement and self-regulation with the dynamical modelling introduced here, enabling direct estimation of individual parameters , comparison across conditions and empirical identification of convergence patterns.

Third, the control policy

used in this study was rule-based and configured by instructors; it was not optimised via reinforcement learning or other adaptive methods. While this choice ensured interpretability and ethical oversight, more sophisticated, yet constrained, optimisation schemes could be explored, provided that they remain transparent and auditable for educators and students [

3,

32]. Hybrid approaches, where policies are learned within strict safety envelopes defined by human stakeholders, are a promising direction.

Fourth, the mapping between questionnaire scales and latent state components is necessarily coarse. Engagement, self-regulation and cognitive safety are complex constructs that cannot be fully captured by a small number of Likert items. Integrating richer behavioural signals (e.g., task persistence metrics, revision patterns, temporal structure of AI interactions), longitudinal performance data and qualitative insights into the state estimation process is an important next step.

Finally, the study was conducted within a single national and institutional context, with particular regulatory and cultural features and a specific configuration of AI tools. Comparative studies across countries, institutional types and regulatory environments would shed light on how different governance regimes and AI cultures influence the design and acceptance of Nested Learning ecosystems, especially in relation to GDPR, institutional AI policies and local notions of student agency.

Despite these limitations, the combination of neuroexperimental evidence, large-scale field data and a mathematically grounded framework suggests that Nested Learning is a promising direction for designing AI-mediated, neuro-adaptive and sustainable higher-education ecosystems. Future work should refine the models, expand the empirical base and co-design policies with students, teachers and policymakers to ensure that such ecosystems remain aligned with human-centred values and the broader goals of Industry 5.0.

6. Conclusions

This article has outlined

Nested Learning as a proposed neuro-adaptive, agent-mediated ecosystem for sustainable higher education. Building on the convergence of generative AI, neuroeducation and smart-campus infrastructures, we have described a multi-layer architecture (

Figure 2) and a dynamical model of learner states that treat assessment, feedback and support as

policy-level design variables rather than as static procedures. The intention is not to claim definitive validation of this construct, but to show that a mathematically grounded and ethically constrained framing can help organise design decisions in AI-rich environments that aspire to sustain engagement, self-regulation and cognitive safety over time in line with the human-centric aspirations of Industry 5.0 [

5,

6].

Empirically, the study has combined a neuro-experimental phase with an 18-student laboratory calibration and a large-scale field phase with 380 participants in authentic courses. Within the limits of a small and homogeneous sample, Phase 1 suggests that low-cost mobile EEG can capture interpretable P300 dynamics and balanced neuroeducational markers in ChatGPT-mediated tasks, supporting the feasibility of neuro-adaptive pipelines in ecologically valid settings. Phase 2 indicates that perceived Nested Learning and neuroadaptive adjustments are moderately to strongly associated with engagement and self-regulation, both quantitatively (correlations and regression models) and qualitatively (four thematic families centred on task immersion, planning, personalisation and emotional safety). When interpreted through the dynamical lens, these patterns are consistent with trajectories in which the relevant components of the learner state vector move towards desirable regions with diminishing increments , although the present data do not allow formal estimation of individual parameters or rigorous stability analysis.

From a sustainability perspective, three provisional conclusions stand out. First,

human-centred AI in higher education appears to require multi-layer orchestration: the most positive experiences arise when teacher, AI agents, peers and physical context are perceived as part of a coherent envelope of support, rather than as isolated tools. Second,

cognitive safety and a Pedagogy of Hope are not by-products but design targets: treating errors as learning opportunities, foregrounding process visibility and regulating arousal within a safe corridor emerge as central to long-term wellbeing and resilience, particularly for students at risk of disengagement or burnout [

9,

28]. Third,

governance is integral to the technical architecture: privacy-by-design, data minimisation and meaningful human oversight over agent policies are necessary conditions for aligning neuro-adaptive capabilities with ethical and regulatory frameworks [

6,

32].

The proposed framework suggests several potential implications for universities seeking to advance the Sustainable Development Goals (especially SDG 4 on quality education and SDG 3 on health and wellbeing). Institutions can (i) experiment with multi-agent, generative-AI stations that foreground process and reflection rather than only answers; (ii) cautiously integrate lightweight neuroeducational sensing to monitor attentional and emotional balance at aggregate or cohort level; and (iii) adopt trace-based assessment formats that value planning, testing discipline and evidence use alongside product quality. These steps point beyond purely efficiency-driven narratives towards a model of higher education that explicitly cares for learners’ cognitive and emotional trajectories, while remaining sensitive to privacy and cognitive sovereignty.

In addition,

Figure 15 summarises a standard neuroimaging view of the real-time neuroelectric dynamics underpinning cognitive nesting, visually illustrating how the ecosystem couples pedagogical micro-events with the temporal evolution of cortical activity.

At the same time, the study has clear limitations in sample diversity, longitudinal depth and scope of the control policy, as discussed in

Section 5. These constraints mean that the findings should be interpreted as exploratory and context-bound rather than as generalisable evidence of effectiveness. Future research should (i) replicate and extend the approach in different disciplines, countries and institutional cultures; (ii) develop longitudinal datasets that allow direct estimation of dynamical parameters and empirical identification of sustainable regions in the state space; and (iii) co-design governance protocols with students, teachers and policymakers to ensure that evolving AI capabilities remain aligned with human values and rights.

In conclusion, Nested Learning should be understood as a working model that illustrates one possible way in which mathematically informed, neuro-aware and ethically constrained design could help turn AI and IoT infrastructures into engines of more sustainable education, rather than sources of additional pressure or inequality. By treating learner states as trajectories to be carefully guided—not merely as scores to be extracted—higher education can begin to harness generative AI as a catalyst for Industry 5.0 and a Pedagogy of Hope, where technological sophistication and human flourishing are pursued together and under explicit governance.

Figure 1.

Temporal overview of the two-phase mixed-methods design underlying the Nested Learning ecosystem. Phase 1 provides an exploratory calibration of the neuro-adaptive pipeline; Phase 2 evaluates its pedagogical and ethical impact in authentic courses.

Figure 1.

Temporal overview of the two-phase mixed-methods design underlying the Nested Learning ecosystem. Phase 1 provides an exploratory calibration of the neuro-adaptive pipeline; Phase 2 evaluates its pedagogical and ethical impact in authentic courses.

Figure 2.

Conceptual view of the Nested Learning ecosystem. (a) Multi-layer architecture surrounding the learner, from neurocognitive states to AI agents, smart-campus infrastructure and governance. (b) Multimodal neuro-adaptive pipeline that integrates EEG, interaction and contextual data through deep learning models to inform agent policies and educational outcomes.

Figure 2.

Conceptual view of the Nested Learning ecosystem. (a) Multi-layer architecture surrounding the learner, from neurocognitive states to AI agents, smart-campus infrastructure and governance. (b) Multimodal neuro-adaptive pipeline that integrates EEG, interaction and contextual data through deep learning models to inform agent policies and educational outcomes.

Figure 3.

Conceptual positioning of Nested Learning at the intersection of generative AI, neuroeducation and sustainable higher education.

Figure 3.

Conceptual positioning of Nested Learning at the intersection of generative AI, neuroeducation and sustainable higher education.

Figure 4.

Instant of the neuroadaptive Nested Learning session in the EEG lab. A student wears a low-cost 14-channel Emotiv EPOC+ headset while real-time cortical activity and brain topographies are displayed on multiple monitors. This corresponds to Image 1 in the Spanish draft (“Instante del trabajo realizado”).

Figure 4.

Instant of the neuroadaptive Nested Learning session in the EEG lab. A student wears a low-cost 14-channel Emotiv EPOC+ headset while real-time cortical activity and brain topographies are displayed on multiple monitors. This corresponds to Image 1 in the Spanish draft (“Instante del trabajo realizado”).

Figure 5.

Use of ChatGPT together with real-time EEG reading and P300 visualization during a Nested Learning activity. The left side of the screen shows the interaction with the generative AI agent, while the right side displays event-related potentials and cortical maps used to monitor attentional dynamics. This corresponds to Image 2 in the Spanish draft (“Utilización de ChatGPT y lectura neuro”).

Figure 5.

Use of ChatGPT together with real-time EEG reading and P300 visualization during a Nested Learning activity. The left side of the screen shows the interaction with the generative AI agent, while the right side displays event-related potentials and cortical maps used to monitor attentional dynamics. This corresponds to Image 2 in the Spanish draft (“Utilización de ChatGPT y lectura neuro”).

Figure 6.

Multi-agent generative-AI station used in the large-scale phase of the study, integrating six platforms (ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Copilot, DeepSeek and GPT-o1) in a single workspace. This photograph illustrates the practical implementation of the Nested Learning ecosystem in a real university setting.

Figure 6.

Multi-agent generative-AI station used in the large-scale phase of the study, integrating six platforms (ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Copilot, DeepSeek and GPT-o1) in a single workspace. This photograph illustrates the practical implementation of the Nested Learning ecosystem in a real university setting.

Figure 7.

Theoretical integration of the Nested Learning ecosystem. Micro-level neurocognitive states are modelled by multimodal and P300-based analytics; meso-level instructional episodes are orchestrated by generative-AI agents; macro-level institutional and sustainability policies constrain and enable deployment. These levels jointly support sustainable higher-education outcomes.

Figure 7.

Theoretical integration of the Nested Learning ecosystem. Micro-level neurocognitive states are modelled by multimodal and P300-based analytics; meso-level instructional episodes are orchestrated by generative-AI agents; macro-level institutional and sustainability policies constrain and enable deployment. These levels jointly support sustainable higher-education outcomes.

Figure 8.

End-to-end pipeline for Phase 1. Pedagogical events and ChatGPT interactions are scripted and pushed to a Kafka bus, which synchronises event markers with EEG acquisition. Data are preprocessed, P300 features are extracted and statistical models are estimated to calibrate the neuro-adaptive sensitivity of the Nested Learning ecosystem.

Figure 8.

End-to-end pipeline for Phase 1. Pedagogical events and ChatGPT interactions are scripted and pushed to a Kafka bus, which synchronises event markers with EEG acquisition. Data are preprocessed, P300 features are extracted and statistical models are estimated to calibrate the neuro-adaptive sensitivity of the Nested Learning ecosystem.

Figure 9.

High-level orchestration pipeline for Phase 2. Students and lecturers interact with a multi-agent generative-AI layer, which also consults smart-campus IoT signals. All interactions and contexts are logged for subsequent analysis of the latent state dynamics and policy effects.

Figure 9.

High-level orchestration pipeline for Phase 2. Students and lecturers interact with a multi-agent generative-AI layer, which also consults smart-campus IoT signals. All interactions and contexts are logged for subsequent analysis of the latent state dynamics and policy effects.

Figure 10.

Emotiv electrode positions and their correspondence with cortical lobes.

Figure 10.

Emotiv electrode positions and their correspondence with cortical lobes.

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of P300 dynamics in Phase 1. Nested Learning segments show higher parietal P300 amplitudes than baseline segments in the 250–400 ms window, consistent with increased attentional engagement and neuro-adaptive sensitivity. Curves are illustrative rather than raw waveforms.

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of P300 dynamics in Phase 1. Nested Learning segments show higher parietal P300 amplitudes than baseline segments in the 250–400 ms window, consistent with increased attentional engagement and neuro-adaptive sensitivity. Curves are illustrative rather than raw waveforms.

| [very thick, blue!70] (0,0)–(0.6,0); |

Nested Learning segments |

| [thick, gray!70] (0,0)–(0.6,0); |

Baseline segments |

Figure 12.

Path representation of regression results. Nested Learning (NL) and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA) jointly predict Engagement (ENG) and Self-Regulation (SRL), with standardised coefficients shown on each path (all ). Arrows represent statistical associations, not causal effects.

Figure 12.

Path representation of regression results. Nested Learning (NL) and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA) jointly predict Engagement (ENG) and Self-Regulation (SRL), with standardised coefficients shown on each path (all ). Arrows represent statistical associations, not causal effects.

Figure 13.

Qualitative map of the four thematic families surrounding the Nested Learning ecosystem. Each family feeds into and is reinforced by the ecosystem, highlighting the interdependence between engagement, self-regulation, neuroadaptive personalisation and emotional safety.

Figure 13.

Qualitative map of the four thematic families surrounding the Nested Learning ecosystem. Each family feeds into and is reinforced by the ecosystem, highlighting the interdependence between engagement, self-regulation, neuroadaptive personalisation and emotional safety.

Figure 14.

Illustrative convergence trajectories for the engagement component under a Nested Learning policy. Both learners move from low to high engagement, but with different effective learning-speed parameters . The empirical results—high engagement, strong self-regulation and stabilised neuroeducational markers—are consistent with trajectories that approach a high-value equilibrium with diminishing increments .

Figure 14.

Illustrative convergence trajectories for the engagement component under a Nested Learning policy. Both learners move from low to high engagement, but with different effective learning-speed parameters . The empirical results—high engagement, strong self-regulation and stabilised neuroeducational markers—are consistent with trajectories that approach a high-value equilibrium with diminishing increments .

Figure 15.

Standard neuroimaging view of the real-time neuroelectric dynamics of cognitive nesting

Figure 15.

Standard neuroimaging view of the real-time neuroelectric dynamics of cognitive nesting

Table 1.

Overview of the two-phase mixed-methods design underpinning the Nested Learning ecosystem.

Table 1.

Overview of the two-phase mixed-methods design underpinning the Nested Learning ecosystem.

| Phase |

Context |

Participants |

Main data sources and aims |

| Neuro-experimental calibration |

Laboratory session with generative-AI-mediated problem solving and controlled instructional events |

18 biomedical undergraduates (21–24 years) |

Mobile EEG (Emotiv EPOC, 14 channels), P300 dynamics, event markers, interaction logs; exploratory validation of the sensitivity and stability of the neuro-adaptive pipeline to instructional micro-events. |

| Field implementation in higher education |

Regular courses at a university in Madrid using multiple generative AI platforms and smart-campus integration |

380 participants (300 students, 80 lecturers) |

Questionnaires (engagement, self-regulated learning, cognitive safety, ethical concerns), platform and agent logs, IoT context signals; evaluate perceived Nested Learning, pedagogical impact and sustainability-related issues at scale. |

Table 2.

Synthesis of the theoretical framework and its operationalisation in the present study.

Table 2.

Synthesis of the theoretical framework and its operationalisation in the present study.

| Theoretical pillar |

Key constructs |

Operationalisation in this study |

Main indicators |

| Nested Learning and Pedagogy of Hope |

Hope, agency, belonging, self-regulated learning |

Design of nested support structures (human + AI), emphasis on dialogic feedback and non-punitive error treatment |

Questionnaire scales on engagement, SRL and perceived cognitive safety; qualitative reports of hope and trust. |

| Multimodal deep learning and neuroimaging |

Attention, cognitive load, context updating (P300), multimodal analytics |

Mobile EEG recordings during LLM-mediated tasks; alignment of P300 with instructional events; fusion of EEG and interaction logs through deep models |

P300 amplitude/latency, anomaly scores, temporal alignment metrics, task-level engagement markers. |

| Agent-based generative AI and IoT |

Multi-agent orchestration, tool use, contextual adaptation via IoT |

Distributed LLM-based agents for feedback, guidance and governance; integration with smart-campus sensors and learning platforms |

Log traces of agent interactions, tool calls and IoT-triggered adaptations; perceived usefulness and transparency of AI support. |

| Governance and sustainability in higher education |

Ethics, data protection, inclusion, long-term resilience |

Privacy-by-design policies, informed consent, data-minimisation strategies and explicit attention to marginalised students |

Compliance checks, participant consent records, reported ethical concerns, perceived fairness and inclusiveness. |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, distributional properties and reliability indices for Nested Learning dimensions and outcomes ().

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, distributional properties and reliability indices for Nested Learning dimensions and outcomes ().

| Dimension / Scale |

Mean |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

|

| Perception of Nested Learning (NL) |

4.12 |

0.78 |

|

|

0.88 |

0.89 |

| Interaction with Generative AI (INT) |

3.95 |

0.82 |

|

|

0.85 |

0.86 |

| Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA) |

3.88 |

0.75 |

|

|

0.82 |

0.84 |

| Climate of Hope and Cognitive Safety (SAF) |

4.25 |

0.71 |

|

|

0.91 |

0.92 |

| Engagement (ENG) |

4.18 |

0.76 |

|

|

0.87 |

0.88 |

| Self-Regulation (SRL) |

4.05 |

0.80 |

|

|

0.86 |

0.87 |

Table 4.

Global fit indices for the four-factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model ().

Table 4.

Global fit indices for the four-factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model ().

| Fit Index |

Observed Value |

Recommended Threshold |

|

(Chi-square / degrees of freedom) |

1.84 |

|

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) |

0.96 |

|

| TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) |

0.95 |

|

| RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approx.) |

0.054 |

|

| SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) |

0.042 |

|

Table 5.

Correlation matrix between Nested Learning (NL), Interaction with Generative AI (INT), Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA), Engagement (ENG) and Self-Regulation (SRL).

Table 5.

Correlation matrix between Nested Learning (NL), Interaction with Generative AI (INT), Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA), Engagement (ENG) and Self-Regulation (SRL).

| Variables |

NL |

INT |

NA |

ENG |

SRL |

| 1. Nested Learning (NL) |

– |

0.54** |

0.63** |

0.57** |

0.52** |

| 2. Interaction (INT) |

0.54** |

– |

0.49** |

0.46** |

0.41** |

| 3. Neuroadaptive (NA) |

0.63** |

0.49** |

– |

0.49** |

0.44** |

| 4. Engagement (ENG) |

0.57** |

0.46** |

0.49** |

– |

0.62** |

| 5. Self-Regulation (SRL) |

0.52** |

0.41** |

0.44** |

0.62** |

– |

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression models for Engagement (ENG) and Self-Regulation (SRL) with Nested Learning (NL) and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA) as predictors.

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression models for Engagement (ENG) and Self-Regulation (SRL) with Nested Learning (NL) and Perceived Neuroadaptive Adjustments (NA) as predictors.

| Dependent |

Predictors |

|

t |

p |

|

| Engagement (ENG) |

Nested Learning (NL) |

0.41 |

9.12 |

|

0.39 |

| |

Neuroadaptive (NA) |

0.33 |

7.08 |

|

|

| Self-Regulation (SRL) |

Nested Learning (NL) |

0.38 |

8.44 |

|

0.34 |

| |

Neuroadaptive (NA) |

0.29 |

6.17 |

|

|