Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

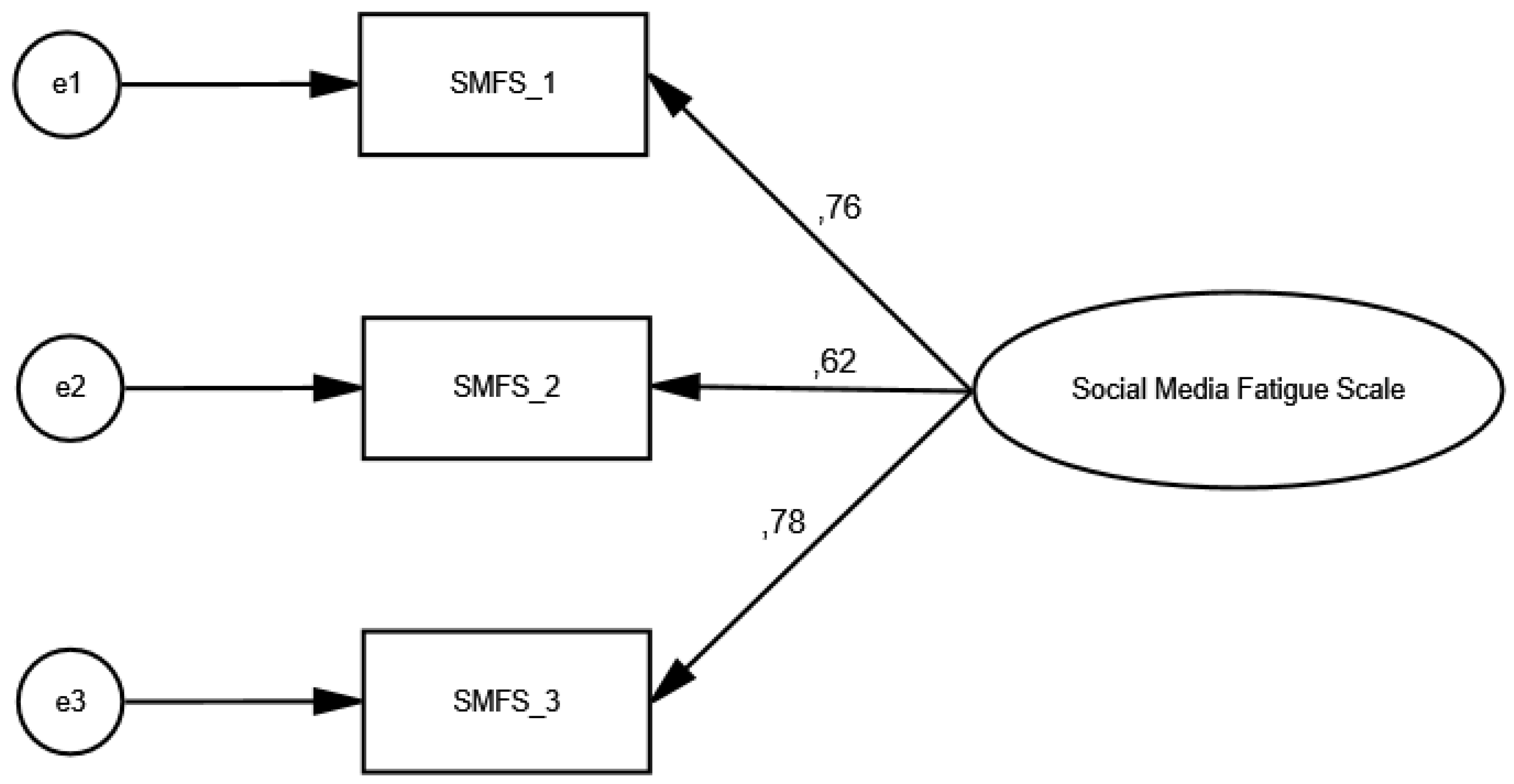

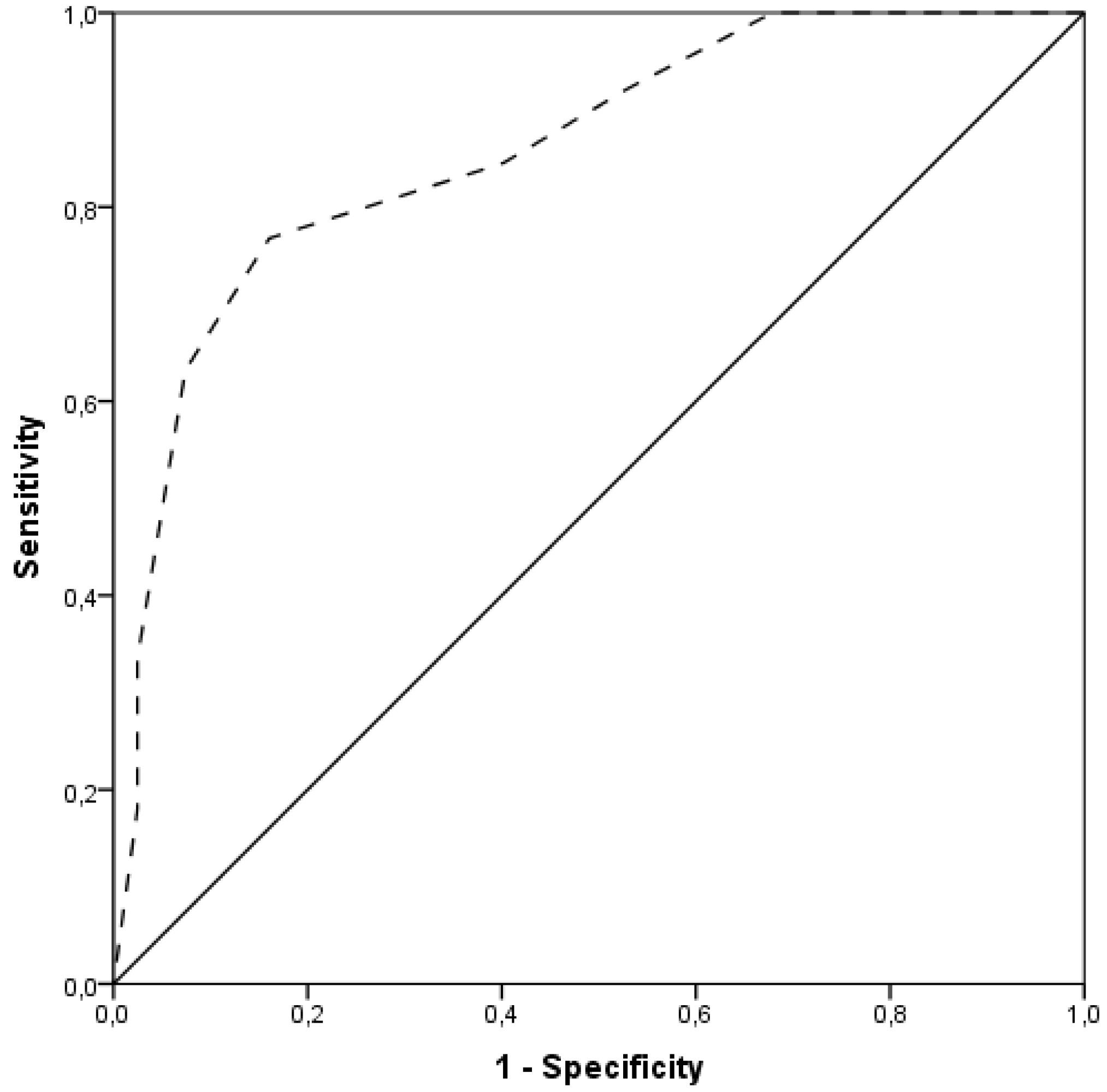

Objective: To develop and validate an ultra brief scale to measure social media fatigue, i.e., the Social Media Fatigue Scale-3 items (SMFS-3). Method: Construct validity of the SMFS-3 was assessed through corrected item–total correlations and confirmatory factor analysis. Concurrent validity was examined using the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4). Reliability was evaluated through multiple indices, including Cronbach’s alpha, Cohen’s kappa, and the intraclass correlation coefficient. Receiver Operating Characteristic analysis was employed to determine the optimal cut-off point for the SMFS-3, using the BSMAS as external criterion. Results: Corrected item–total correlations and confirmatory factor analysis confirmed that the final version of the SMFS-3 includes three items in one factor. Concurrent validity of the SMFS-3 was excellent since we found statistically significant correlations between the SMFS-3 and the BSMAS, and the PHQ-4. Cronbach’s alpha for the SMFS-3 was 0.762. Cohen’s kappa for the three items ranged from 0.852 to 0.919 (p < 0.001 in all cases). Additionally, intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.986 (p < 0.001). Thus, the reliability of the SMFS-3 was excellent. The best cut-off point for the SMFS-3 was 10, indicating that social media users with SMFS-3 score ≥10 were considered as users with high levels of social media fatigue, and those with SMFS-3 score <10 as users with normal levels of fatigue. Conclusions: The SMFS-3 is a one-factor 3-item scale with great reliability and validity. The SMFS-3 is a short and easy-to-use tool that measures levels of social media fatigue in a couple of minutes. Valid measurement of social media fatigue with brief and valid tools is essential to further understand predictors and consequences of this fatigue.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design

Procedure

Measurements

Statistical Analysis

Results

Participants

Construct Validity

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Concurrent Validity

Reliability

Cut-Off Point

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of interest

References

- BLANCO-GONZÁLEZ-TEJERO, C; ULRICH, K; RIBEIRO-NAVARRETE, S. Can social media be a key driver to becoming an entrepreneur? J Knowl Econ 2024, 15, 16780–16798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEHERA, N; KHUNTIA, S; PANDEY, K; SHANKAR, S. Impact of social media use on physical, mental, social, and emotional health, sleep quality, body image, and mood: evidence from 21 countries—a systematic literature review with narrative synthesis. Int J Behav Med 2025. under press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NDINDENG, A. The impact of social media on mental health. Ment Health Digit Techn 2025, 2, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GALANIS, P; KATSIROUMPA, A; KATSIROUMPA, Z; MANGOULIA, P; GALLOS, P; MOISOGLOU, I; et al. Association between problematic TikTok use and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIMS Public Health 2025, 12, 491–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONTE, G; IORIO, GD; ESPOSITO, D; ROMANO, S; PANVINO, F; MAGGI, S; et al. Scrolling through adolescence: a systematic review of the impact of TikTok on adolescent mental health. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2025, 34, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATSIROUMPA, A; MOISOGLOU, I; MITROPOULOS, A; PASCHALI, A; KOUTELEKOS, I; KATSIROUMPA, Z; et al. Association between social media addiction and mental health among Greek young adults. Int J Caring Sci 2025, 18, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- JAIN, L; VELEZ, L; KARLAPATI, S; FORAND, M; KANNALI, R; YOUSAF, RA; et al. Exploring problematic TikTok use and mental health issues: a systematic review of empirical studies. J Prim Care Community Health 2025, 16, 21501319251327303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATSIROUMPA, A; KATSIROUMPA, Z; KOUKIA, E; MANGOULIA, P; GALLOS, P; MOISOGLOU, I; et al. Association between problematic TikTok use and procrastination, loneliness, and self-esteem: A moderation analysis by sex and generation. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2025, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATSIROUMPA, A; MOISOGLOU, I; GALLOS, P; KATSIROUMPA, Z; KONSTANTAKOPOULOU, O; TSIACHRI, M; et al. Problematic TikTok use and its association with poor sleep: A cross-sectional study among Greek young adults. Psychiatry Int 2025, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BILALI, A; KATSIROUMPA, A; KOUTELEKOS, I; DAFOGIANNI, C; GALLOS, P; MOISOGLOU, I; et al. Association between TikTok use and anxiety, depression, and sleepiness among adolescents: A cross-sectional study in Greece. Pediatr Rep 2025, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEE, AR; SON, S-M; KIM, KK. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Comput Hum Behav 2016, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRAMER, EM; SONG, H; DRENT, AM. Social comparison on Facebook: Motivation, affective consequences, self-esteem, and Facebook fatigue. Comput Hum Behav 2016, 64, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHENG, N; YANG, C; HAN, L; JOU, M. Too much overload and concerns: Antecedents of social media fatigue and the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Comput Hum Behav 2023, 139, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FU, S; LI, H; LIU, Y; PIRKKALAINEN, H; SALO, M. Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: Examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Inf Process Manag 2020, 57, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIN, C; LI, Y; WANG, T; ZHAO, J; TONG, L; YANG, J; et al. Too much social media? Unveiling the effects of determinants in social media fatigue. Front Psychol 2024, 15, 1277846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGUYEN, L; WALTERS, J; PAUL, S; IJURCO, SM; RAINEY, G; PAREKH, N; et al. Feeds, feelings, and focus: A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the cognitive and mental health correlates of short-form video use. Psychol Bull 2025, 151, 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRANNIGAN, R; CRONIN, F; MCEVOY, O; STANISTREET, D; LAYTE, R. Verification of the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the association between screen use, digital media and psychiatric symptoms in the growing up in Ireland study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2023, 58, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VEDECHKINA, M; BORGONOVI, F. A Review of evidence on the role of digital technology in shaping attention and cognitive control in children. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 611155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACHTERBERG, M; BECHT, A; VAN DER CRUIJSEN, R; DE GROEP, I; SPAANS, J; KLAPWIJK, E; et al. Longitudinal associations between social media use, mental well-being and structural brain development across adolescence. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2022, 54, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHEN, Y; LI, M; GUO, F; WANG, X. The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Behav Inform Technol 2023, 42, 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DU, Y; WANG, J; WANG, Z; LIU, J; LI, S; LV, J; et al. Severity of inattention symptoms, experiences of being bullied, and school anxiety as mediators in the association between excessive short-form video viewing and school refusal behaviors in adolescents. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1450935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GALANIS, P; KATSIROUMPA, A; MOISOGLOU, I; KONSTANTAKOPOULOU, O. The TikTok Addiction Scale: Development and validation. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 1172–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GALANIS, P; KATSIROUMPA, A; KONSTANTAKOPOULOU, O; GALANI, O; TSIACHRI, M; MOISOGLOU, I. Development and validation of the TikTok Addiction Scale-Short Form. Arch Hellenic Med Under press. 2026. [Google Scholar]

- VARONA, MN; MUELA, A; MACHIMBARRENA, JM. Problematic use or addiction? A scoping review on conceptual and operational definitions of negative social networking sites use in adolescents. Addict Behav 2022, 134, 107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANDREASSEN, CS; TORSHEIM, T; BRUNBORG, GS; PALLESEN, S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep 2012, 110, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, S; SHEN, Y; XIN, T; SUN, H; WANG, Y; ZHANG, X; et al. The development and validation of a social media fatigue scale: From a cognitive-behavioral-emotional perspective. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FARACI, P; NASONTE, G. The Brief Social Media Fatigue Scale (BSMFS): A new short version through exploratory structural equation modeling and associations with trait anxiety, fear of missing out, boredom proneness, and problematic use. Int J Hum-Comput Interact 2025, 41, 10096–10122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WORLD MEDICAL ASSOCIATION. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAJ-ROGOWSKA, A. Antecedents and outcomes of social media fatigue. Iinform Technol Peopl 2023, 36, 226–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANDREASSEN, CS; BILLIEUX, J; GRIFFITHS, MD; KUSS, D; DEMETROVICS, Z; MAZZONI, E; et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav 2016, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATSIROUMPA, A; KATSIROUMPA, Z; KOUKIA, E; MANGOULIA, P; GALLOS, P; MOISOGLOU, I; et al. Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale: Translation and validation in Greek. Int J Caring Sci 2025, 18, 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- KROENKE, K; SPITZER, RL; WILLIAMS, JBW; WILLIAMS, J; LOWE, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- KAREKLA, M; PILIPENKO, N; FELDMAN, J. Patient Health Questionnaire: Greek language validation and subscale factor structure. Compr Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| In the last 12 months … | Corrected item-total correlation |

|---|---|

|

0.443 |

|

0.551 |

|

0.648 |

|

0.522 |

|

0.646 |

|

0.628 |

|

0.724 |

|

0.333 |

|

0.740 |

| During the last 12 months … | Answers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very rarely | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Scales | BSMAS | PHQ-4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Total | ||

| SMFS-3 | 0.666* | 0.361* | 0.326* | 0.32* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).